Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are cell-derived nanoparticles with an important role in intercellular communication, even across brain barriers. The bidirectional brain-barrier crossing capacity of EVs is supported by research identifying neuronal markers in peripheral EVs, as well as the brain delivery of peripherally administered EVs. In addition, EVs are reflective of their cellular origin, underlining their biomarker and therapeutic potential when released by diseased and regenerative cells, respectively. Both characteristics are of interest in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) where the current biomarker profile is solely based on brain-centered readouts and effective therapeutic options are lacking. In this review, we elaborate on the role of peripheral EVs in AD. We focus on bulk EVs and specific EV subpopulations including bacterial EVs (bEVs) and neuronal-derived EVs (nEVs), which have mainly been studied from a biomarker perspective. Furthermore, we highlight the therapeutic potential of peripherally administered EVs whereby research has centered around stem cell derived EVs.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Extracellular vesicles, Biomarkers, Mesenchymal stem cells, Therapeutics

1. Introduction

Intercellular communication is of vital importance for multicellular organisms. Communication can occur via different mechanisms including direct cell–cell contact, secretion of signalling molecules (e.g., hormones, neurotransmitters, cytokines), tunnelling nanotubes, non-membranous extracellular particles (exomeres) as well as extracellular vesicles (EVs). EVs comprise a heterogenous population of nanosized particles enclosed by a lipid membrane that seem to be secreted by all cell-types[1]. Based on their mode of biogenesis, EVs can be divided in two main categories: ectosomes (including microvesicles) and exosomes whereby both categories contain multiple EV subtypes. Distinguishing between the EV subtypes based on their size is challenging given their overlapping size range and the heterogeneity of this size range that is reported in literature. Furthermore, there is currently no consensus on the characterization of EV subtypes based on their protein composition[2]. Therefore, as supported by the minimal information for studies of EVs (MISEV) guidelines[3], we will consistently use the generic term “EV” throughout this review. The cargo (e.g., proteins, lipids, and genetic material) of EVs is encapsulated in a membrane bilayer and thereby is shielded from dilution or degradation in the extracellular environment, allowing protected transport to both adjacent and distant target cells, even across brain barriers. This concept of brain-to-periphery and periphery-to-brain communication mediated by EVs underlies their potential as a source of biomarkers and brain (drug) delivery vehicles, respectively. In this review, we elaborate on the role of peripheral EVs in AD, which has mainly been studied in a biomarker context. Furthermore, we compile literature describing the therapeutic capacity of EVs in AD and touch upon some challenges inherently linked to this approach.

2. Peripheral EVs in AD

EVs are present in a variety of peripheral biofluids, including blood, urine and saliva. The accessibility of these fluids in combination with the fact that EV composition is reflective of their cellular origin sparked enthusiasm for their capacity as a source of biomarkers. Biomarkers are of particular interest for neurodegenerative diseases including AD, for which clinical diagnosis is only possible when considerable and irreversible neuronal damage has already occurred. Current guidelines describe three stages of AD progression (i.e., preclinical AD, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to AD or prodromal AD, and dementia due to AD) and included the use of biomarkers that are altered in all three AD stages[4–8]. Currently accepted biomarkers for AD are based on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), positron emission tomography (PET), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and reflect the cardinal features of the disease: amyloidosis (A), tauopathy (T), and neurodegeneration (N) according to the ATN schema[8–10]. Despite its systematizing value, there is a growing appreciation that ATN does not capture the phenotypic and pathogenic complexity of AD. Furthermore, the currently available biomarker profile has several limitations. On the one hand, the imaging-based techniques are relatively expensive, whereas CSF analysis involves a lumbar puncture, which is an invasive technique. Consequently, ATN biomarkers are not routinely used in clinical practice for late-onset dementia, and are typically implemented only in the differential diagnosis for early onset dementia or when atypical features predominate the clinical presentation[11]. Preferentially, biomarkers should be derived from easily accessible biofluids, rely on widely available technologies, and incur low cost-requirements that may best be met by blood biomarkers[12]. Although considerate efforts are being made in this research area[13], it is important to realize that the presence of tight brain barriers impedes the detection of relevant biochemical markers reflecting brain pathology in peripheral biofluids. Of note, the bidirectional brain-barrier crossing capacity of EVs is supported by a substantial amount of research identifying neuronal markers in peripheral EVs, as well as the brain delivery of peripherally administered EVs, as elaborated on below. However, convincing experimental evidence of EVs transferring through these brain-barriers is still limited. In the following paragraphs, we will review literature on peripheral EVs in AD, divided in (1) bulk, (2) neuronal-derived and (3) bacterial EVs. Furthermore, we will discuss what is currently known about their clinical potential and biological function.

2.1. Bulk EVs

The total number of plasma EVs in AD individuals has been reported to be either equal[14] or increased[15,16] in comparison to controls. Similar results were reported for the size of the EVs, being either equal[14] or increased[15]. Taking into account the ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene in cognitively impaired, non-demented patients, equal plasma EV numbers but a lower mean EV size were observed in APOE ε4 allele carriers[17]. Furthermore, cognitively impaired, non-demented patients carrying the APOE ε4 allele had decreased levels of certain neurotrophic (i.e., DJ-1, progranulin, α-synuclein) and inflammatory (i.e., lipocalin, S100B, pentraxin-2, ANGPTL-4) factors in their plasma EVs compared to non-APOE ε4 allele carriers[17]. Different proteases (e.g., α-, β- and γ- secretases) linked to amyloid beta (Aβ) biogenesis were present in plasma-derived EVs of AD patients[16]. Proteomics-based studies revealed that serum[18]- and plasma [14,15]-derived EVs from AD patients contain elevated levels of proteins involved in the inflammatory response (e.g., complement activation[14,15,18]), coagulation processes (e.g., fibrinolysis [14,15]) and lipid-carbohydrate metabolism[15] in comparison with healthy controls[14]. Hereby, specific proteins (i.e., ORM2, RBP4, HYDIN, FXIIIA1, and FXIIIB) associated with plasma EVs could discriminate between AD patients and healthy controls, underlining their biomarker potential[14]. Of note, altered protein levels detected in plasma EVs were often absent in complete plasma[14,17], underlining the sensitivity advantage when using plasma EVs as a biomarker source.

Besides proteins, RNA sequencing analysis has revealed that mitochondrial (mt)-RNAs, including MT-ND1–6 mRNAs and other protein-coding and non-coding mt-RNAs, were strikingly elevated in plasma EVs of MCI and AD individuals compared with healthy controls, perhaps, reflecting mitochondrial abnormalities that occur in the AD brain[19]. Also many miRNAs have been detected in EVs derived from serum[20–23] or plasma[24], with several of them (i.e., miR-223[20], miR-193b[22,23], miR-135a[23], miR-384[23], multiple miRNA profiles[21,24]) harboring biomarker potential, as their altered levels could discriminate AD patients from healthy controls[20,21,23,24] and MCI patients[23] with varying degrees of sensitivity and specificity. Another study also showed upregulation of several miRNAs in serum-derived EVs of AD patients, whereby little correlation with miRNA expression profiles in brain homogenate and brain tissue-derived EVs was observed[25]. Even though these studies indicate the diagnostic potential of bulk EVs in blood, most biomarker-centered research has focused on enrichment for brain-derived EVs prior to analysis (see below). This choice is probably driven by the fact that most bulk EVs in blood do not originate from the central nervous system (CNS), increasing potential noise over signal and suggesting a lower sensitivity in brain disorders such as AD. Nonetheless, immunoprecipitation (IP)-based protocols to enrich for subpopulations also come with technical challenges (e.g., antibody affinity and specificity, and choice of surface marker) and drawbacks (e.g., cost of antibodies, longer processing time and increased effort, and loss of EVs in consecutive steps) compared to bulk EV analysis. Studies to directly compare the biomarker potential between unprocessed plasma, bulk EVs, and specific EV subtypes are warranted and will be instrumental to guide the choice of the optimal EV subtype to pursue any given biomarker.

The cellular origin of plasma EVs in AD has been studied using flow cytometry, revealing higher percentages of EVs positive for endothelial or leukocyte markers (e.g., CD45 and CD105) in sporadic AD patients and EVs positive for platelet markers (e.g., CD41a) in familial AD patients compared to controls[15]. Furthermore, hepatocytes have been suggested as a partial source of EVs in plasma of AD patients. Indeed, plasma EVs of AD patients harbor a distinct profile of cytokines, chemokines and soluble factors compared to plasma EVs from different neurological patients, whereby the AD plasma EV profile partially overlaps with the EV profile derived from a Huh-7 hepatocyte cell line[16]. Interestingly, one study reported that Huh-7 derived EVs travel to the hippocampus via the blood-CSF barrier located at the choroid plexus upon their intravenous (IV) injection in mice[16].

In addition to blood, other peripheral biofluid sources (e.g., urine, saliva) may provide high usability due to their noninvasive collection procedures and direct accessibility. In this context, higher EV numbers and increased levels of both Aβ and phosphorylated Tau (p-Tau) have been reported in both urine[26] and saliva[27] of AD patients compared to control subjects.

2.2. Neuronal-derived EVs (nEVs)

Enriching for EVs derived from cellular sources that are known to be involved in the disease process (e.g., neurons and glia in the case of AD) is believed to further improve their biomarker potential by improving measurement sensitivity, lowering the detection threshold and enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio[28]. Indeed, several studies indicate that EV-associated proteins may serve as a liquid brain biopsy by providing a snapshot of molecular events occurring in the brain of patients with neurodegenerative diseases[29]. Hereto, several markers for different brain cells have been applied with L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1CAM) being the most intensively studied surface marker to enrich for neuronal-derived EVs (nEVs). Within the scope of this review, we will only focus on nEVs studied in the periphery and not in the CNS, e.g., derived from CSF or brain tissue.

2.2.1. L1CAM + EVs

L1CAM is a transmembrane glycoprotein, consisting of a long ectodomain with six immunoglobulin-like domains and five fibronectin type III repeats, a single transmembrane domain and a relatively short cytoplasmic domain. Functionally, L1CAM is of importance in neural development as evident by its involvement in neurite outgrowth, fasciculation and myelination, amongst others[30]. Additionally, L1CAM plays a role in the progression of multiple cancers[31]. As such, L1CAM is highly expressed in the nervous system and in a variety of cancer cells[31]. Signaling can be mediated by full-length, membrane-bound L1CAM or its cytosolic and extracellularly released cleaved forms, obtained via proteolytic cleavage or alternative splicing[31]. Furthermore, extracellular L1CAM is believed to be present on EVs released by L1CAM-expressing cells, as shown in the case of ovarian carcinoma cells[32] or primary cortical cultures[33]. As a result, both its high neuronal expression and presence on neuronal culture-derived EVs were reasons to identify L1CAM as a marker to enrich for nEVs. Published methodologies employ crude EV separation followed by IP to enrich for EV subpopulations expressing L1CAM[28,34]. Hereby, EV separation and/or the presence of L1CAM on the EVs is generally supported by western blot (WB) analyses showing both L1CAM and EV markers (e.g., CD9) in purified anti-L1CAM precipitated EVs, Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) confirming the EV-overlapping size-range of anti-L1CAM precipitated EVs, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging confirming the characteristic EV morphology of L1CAM precipitated EVs. Furthermore, flow cytometry studies sorting L1CAM-precipitated EVs using a FITC-labeled general EV antibody (i.e., exo-FITC) have shown the presence of EVs in the L1CAM precipitate[35,36]. Together, these quality control measures support successful isolation of EVs supposedly expressing L1CAM based on the IP enrichment protocol, although none of these approaches directly proves the colocalization of L1CAM on single EVs. Recently, criticism has been raised by a study showing that EV markers (CD9, CD63 and CD81) and L1CAM mainly elute in distinct fractions separated using size exclusion chromatography (SEC) of CSF and plasma, indicating that the majority of L1CAM in these biofluids is not EV-bound[37]. Nonetheless, the latter doesn’t exclude that a small but adequate proportion of extracellular L1CAM is present on EVs and/or that only a minority of EVs express L1CAM, as can be expected in a heterogenous biofluid such as plasma. Indeed, NTA-based analysis indicated that the amount of L1CAM + EVs is 90–95 % lower than the amount of bulk plasma EVs[28]. We recently extended the degree of nEV characterization by demonstrating by WBs that L1CAM + nEVs display both 200 and 220 kD characteristic bands (with the full-length 220 kD band being present in brain lysate), while EVs immunocaptured with a mixture of anti-tetraspanin antibodies and eluate of beads only (BO) display solely the 200 kD band, suggesting that L1CAM + nEVs contain membrane bound as well soluble L1CAM, whereas other preparations contain only soluble L1CAM. The ratio of L1CAM/CD9 is manyfold higher for L1CAM + nEVs when compared to BO or tetraspanin + EVs, suggesting specificity of the anti-L1CAM IP. Confocal fluorescence microscopy with Airyscan after double immunolabeling with L1CAM and EV neuronal marker VAMP2 demonstrates the coexistence of L1CAM and VAMP2 on particles at the size range of single EVs [139]. Indeed, ongoing developments in the EV field such as high-resolution microscopy and techniques allowing colocalization of multiple markers on single EVs, will be essential to resolve controversy about L1CAM as a surface marker of EVs. Furthermore, standardization efforts in terms of nomenclature, reporting of experimental parameters and EV characterization will be of major importance for the progression of the L1CAM + EV-field, as a systematic review identified large inconsistencies regarding these parameters in current literature[34].

Another concern applies to the cellular specificity of L1CAM, which is not exclusively neuronal. However, the concomitant enrichment for various relatively specific neuronal markers in L1CAM precipitated EVs points towards neuronal enrichment [28,38]. The latter is further supported by a study in mice expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) under control of a nervous system specific nestin promotor, whereby L1CAM-enriched nEVs isolated from plasma were shown to contain GFP[28]. Of note, L1CAM expression in the nervous system comprises both the central and peripheral nervous system, suggesting that L1CAM nEVs may not be brain-derived. This however does not necessarily compromise their biomarker potential, as the enteric nervous system could be affected in AD[39]. Altogether and despite current controversy, a large body of studies have utilized an L1CAM based approach to enrich for nEVs, collectively identifying a variety of proteins giving insight in dysregulated AD pathways. The data obtained by these studies is summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Biomarker potential of L1CAM + extracellular vesicles (EVs) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Schematic representation of identified biomarker candidates (boxes) and their idealized levels (graphs) in control (ctrl), preclinical AD (pAD) and AD patients. (A-D) Idealized data based on longitudinal studies analyzing repeated samples of a single patient prior to (pAD) and after diagnosis (AD), compared to controls. The level of some biomarker candidates already plateaus at the pAD stage (A, C), allowing the identification of patients at an early disease stage before the occurrence of clinical symptoms (i.e., preclinical biomarkers). The levels of other biomarker candidates are intermediary changed at the pAD stage (B, D), allowing the differentiation between different stages of AD and follow-up of disease progression (i.e., prognostic biomarkers). (E-F) Idealized data based on studies comparing biomarker candidates between AD patients and controls, allowing the differentiation between AD patients and controls (i.e., diagnostic biomarkers). Abbreviations: AMPA4: GluA4-containing glutamate; Aβ: amyloid beta; GAP43: growth-associated protein 43; HSF1: heat-shock factor-1; HSP70: H-heat-shock protein 70; IRS-1: insulin receptor substrate-1; LAMP1: lysosome-associated membrane protein 1; LRP6: lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6; NLGN1: neuroligin 1; NPTX2: neuronal pentraxin 2; NRGN: neurogranin; NRXN2α: neurexin 2α; REST: repressor element 1-silencing transcription factor; sAPP: soluble amyloid precursor protein; SNAP-25: synaptosomal-associated-protein 25.

From a biomarker perspective, longitudinal studies collecting repeated samples of a single patient for extensive amounts of time prior to diagnosis of a certain disease are of high value. Indeed, these studies offer the possibility of identifying future AD patients in the preclinical stage and may be used to inform clinical trial design and therefore drug development. In small discovery cohorts, levels of several neurotoxic and lysosomal markers were already intermediary (p-S396-Tau, Aβ42) or maximally (p-T181-Tau, Cathepsin D, LAMP1, Ubiquitin) increased in nEVs up to 10 years before AD diagnosis, representing prognostic and/or preclinical value, respectively[40,41]. Proteins linked to altered insulin signaling (i.e., altered levels of functionally opposite p-S312-IRS-1 and p-Y-IRS-1) already plateaued in preclinical AD patients as well[42]. Similar results were obtained for cellular survival factors as well as synaptic and heat-shock proteins, evident by intermediate (i.e., synaptotagmin, synaptopodin, NLGN1, NRXN2α, AMPA4, NPTX2, GAP43, LRP6, HSF1, REST) and similar (i.e., synaptophysin, NRGN, HSP70) decreases in preclinical compared to clinical AD patients [41,43–45]. The levels of another synaptic protein, SNAP-25, were decreased in serum-derived nEVs from AD patients in comparison with healthy controls[46] whereas the reverse pattern was observed for p-T181-Tau, p-S396-Tau, sAPPα, sAPPβ and Aβ42 in plasma-derived nEVs[47]. In MCI patients who later converted to AD, nEV levels of several proteins were increased (i.e., p-T181-Tau, p-S396-Tau and Aβ42) or decreased (i.e., NRGN, REST) to the same extent as in AD patients, whereas only p-T181-Tau and NRGN were similarly altered in stable MCI patients[48]. As such, nEVs can also be helpful in predicting which MCI patients are most likely to progress to AD[48]. Also in subjects with cognitive decline milder than MCI, higher levels of p-T181-Tau, p-S396-Tau and t-Tau were observed in serum nEVs compared to cognitively stable subjects, especially at older age[49]. Nonetheless, other studies reported indifferent (p-)Tau levels in plasma nEVs of control and MCI or AD patients[50,51]. Levels of miR-132 and miR-212 are decreased in plasma nEVs of AD patients and to a lesser extent MCI patients, whereby especially miR-212 could discriminate between control and AD with reasonable receiver operating curve (ROC) values [52]. Another miRNA study reported alterations in plasma nEVs as well, with both elevated (i.e., miR-23a-3p, miR-223–3p, miR-190a-5p) and lowered (i.e., miR-100–3p) levels in AD patients versus controls[53].

Compared to single biomarkers, a combination of different markers could have a greater performance in terms of sensitivity and specificity. Analysis of plasma nEVs derived from longitudinal samples of preclinical AD patients and controls resulted in a profile (including plasma nEV concentration, nEV mean diameter and nEV levels of total Tau, p-T181-Tau, p-T231-Tau, p-Y-IRS-1 and p-S312-IRS-1) that could predict both future AD development and discriminate clinical AD with high levels of accuracy[54]. Prospective longitudinal memory performance could be predicted in a cohort of individuals with cognitive decline milder than MCI based on a profile including several proteins related to insulin signaling[49]. Other studies performing stepwise discriminant or similar analyses progressively including combinations of markers as discussed above yielded satisfactory profiles to discriminate between controls, MCI patients and AD patients, although their performance and optimal combination depended on which groups were compared[40–44,47,48]. Several of the nEV proteins also differed between frontotemporal dementia (FTD) patients and controls, whereby some of them (e.g., synaptic proteins[43], lysosomal proteins[41], cellular survival factors[44], p-S396-Tau[40], and insulin resistance factor[42]) allowed distinguishing AD from FTD pointing towards their utility in differential diagnosis.

2.2.2. Other selection markers

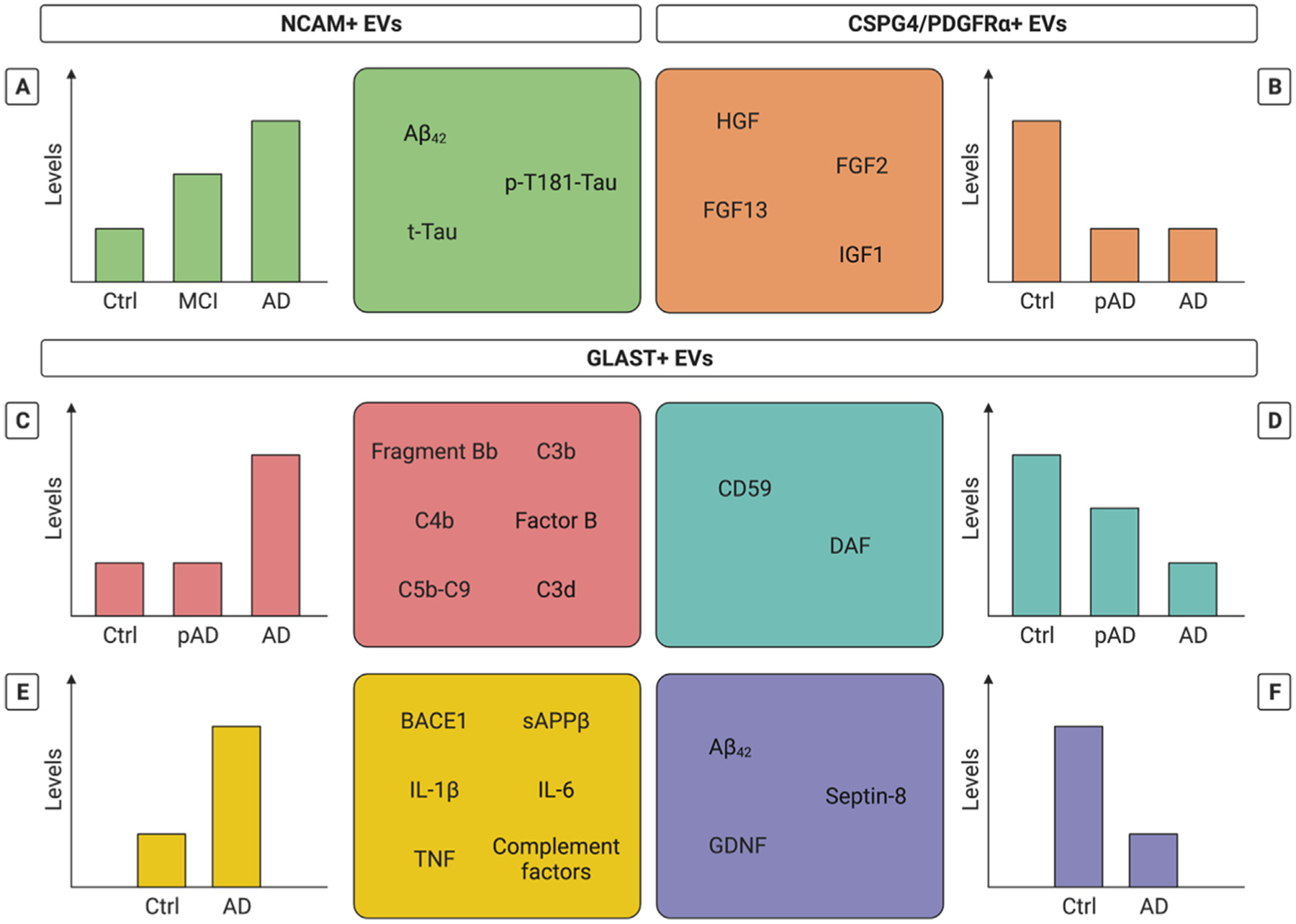

Neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) is an alternative marker that has been targeted by IP to enrich for nEVs. NCAM + plasma EVs demonstrate stepwise increases in the amount of Aβ42, t-Tau and p-T181-Tau measured in control, MCI and AD patients[38]. The observed pattern of t-Tau and p-T181-Tau in the nEVs mimicked changes observed in CSF, whereas for Aβ42 a reversed CSF pattern (i.e., stepwise decrease in AD, MCI and control patients) was seen [38]. Combining biomarkers measured in either CSF or in nEVs achieves similarly high diagnostic accuracies, supporting the validity of nEVs as a reflection of brain pathology[38]. In addition to neurons, other brain cells playing central roles in AD pathogenesis release EVs into the periphery. Hereby, the glutamine aspartate transporter (GLAST) has been used to enrich for astrocyte-derived EVs (aEVs)[47,55,56]. When compared to nEVs immuno-precipitated via targeting L1CAM, plasma aEVs contain higher levels of various proteins important in AD pathogenesis (i.e., BACE1, γ-secretase, sAPPβ, sAPPα, p-T181-Tau, p-S396-Tau, Aβ42, GDNF)[47]. Interestingly, aEVs from AD patients include both higher (i.e., BACE1, sAPPβ, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF, various complement factors) and lower (i.e., septin-8, GDNF, Aβ42) protein levels than aEVs from controls[47,55], whereas levels of sAPPβ in aEVs could also distinguish between AD and FTD[47]. Focusing on complement proteins, the levels of CD59 and DAF were already decreased in preclinical AD patients and continued to decline in clinical AD [55]. In contrast, other complement proteins (e.g., C3b, C3d, C4b, and factor B) were found increased in clinical AD but not yet at its preclinical stage[55]. Also, endothelial-enriched EVs obtained via sequential IP with chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4) and anti-platelet growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα) have been studied[57]. These EVs contained lower levels of several neurotrophic factors (i.e., HGF, FGF2, FGF13 and IGF1), already in pre-clinical AD patients[57]. In terms of their general abundance in plasma, NTA-based measurements indicate that the number of GLAST + aEVs is lower than[47] or similar to[56] the number of L1CAM + nEVs. Characterization of GLAST + aEVs has lagged behind that of L1CAM + nEVs, however, employing similar methods targeting both bulk isolates (e.g., NTA, and WB) and, even more importantly, single EVs (e.g., high resolution microscopy, and flow cytometry analysis) is expected to shed further light on this matter. The data discussed in this section are summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Biomarker potential of NCAM+, CSPG4/PDGFRα + and GLAST + extracellular vesicles (EVs) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Schematic representation of identified biomarker candidates (boxes) and their idealized levels (graphs) in control (ctrl), mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD patients in (A) presumably neuronal-derived, NCAM + EVs, (B) presumably endothelial-enriched, CSPG4 and PDGFRα + EVs and (C-F) presumably astrocyte-derived, GLAST + EVs Panel B-D show idealized data based on longitudinal studies analyzing repeated samples of a single patient prior to (pAD) and after diagnosis (AD), compared to controls. The level of some biomarker candidates already plateaus at the pAD stage (B), allowing the identification of patients at an early disease stage before the occurrence of clinical symptoms (i.e., preclinical biomarkers). The levels of other biomarker candidates are intermediary changed at the pAD (A,D) or MCI (A) stage, allowing the differentiation between different stages of AD and follow-up of disease progression (i.e., prognostic biomarkers). Abbreviations: Aβ: amyloid beta; BACE1: β-site APP cleaving enzyme-1; CSPG4: Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4; DAF: Decay-accelerating factor; FGF: Fibroblast growth factor; GLAST: Glutamine aspartate transporter; HGF: Hepatocyte growth factor; IGF: Insulin-like growth factor; IL: interleukin; NCAM: Neural cell adhesion molecule; PDGFRα: anti-platelet growth factor receptor alpha; sAPPβ: soluble amyloid precursor protein beta; t-Tau: total Tau; TNF: tumor necrosis factor.

Although the available candidates are highly valuable, limitations regarding their specificity for a cell-type of interest are pushing the field towards exploration of alternative and/or additional markers. Optimally, these markers should be expressed on the surface of EVs, highly expressed on the cell-type of interest, cell-type specific and bound by available antibodies with high affinity. Proteomics-based studies of brain-derived[58] and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neural cells[59] could be instrumental in this pursuit, since they may reveal potential candidates by which we may enrich EVs derived from brain cells (e.g., neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes). Furthermore, targeting several markers simultaneously or sequentially could be explored to further enhance cellular specificity. Of note, as also discussed in [34], (a/n)EV biomarker candidates with diagnostic, prognostic or preclinical capacity retain their practical usefulness independent of their cellular origin and the specificity thereof. Therefore, issues related to enrichment for specific EV subpopulations are crucial to consider from a biological point of view, whereas they may be less important from a clinical standpoint.

2.3. Bacterial EVs (bEVs)

In addition to bulk EVs and EVs released by specific cell-types, bacterial EVs have been identified as another EV subtype of interest in AD. Indeed, similar to eukaryotic cells, most bacteria release membranous vesicles that affect diverse biological processes including cell-to-cell communication[60]. Based on their mode of biogenesis, different types of bacterial vesicles exist, which are comprised under the umbrella term bEVs[61]. They have tremendous potential in a variety of biomedical applications, ranging from vaccines to cancer immunotherapy agents, drug delivery vehicles and diagnostic biomarkers[62]. Considering the latter, it has been suggested that bEVs in peripheral biofluids could reflect disease-associated microbiome changes. Of note, gut microbiota studies in both animal models and humans reveal clear changes in microbiota composition in AD, although the exact compositional differences currently remain inconsistent[63]. In APP/PS1 mice, meta-genome analysis of serum-derived bEVs revealed alterations in the microbiota profile in comparison with wild-type (WT) mice [64]. Furthermore, the identified bEV microbiota profile corresponded to the composition of the gut microbiota as reported in other studies, suggesting that bEVs could be used as a tool for evaluating microbial dysbiosis[64]. Also, variations in metabolites have been revealed in faecal bEVs of AD patients compared to controls, whereby several of them could discriminate between AD and control with high sensitivity[65]. Although preliminary and in need of thorough investigation, these results suggest that bEVs could harbour biomarker potential in AD.

Additionally, bEVs may play a role in AD pathogenesis due to their barrier-crossing capacity. Indeed, emerging evidence indicates that bEVs from the resident microbiota can enter the systemic circulation where they may elicit immunomodulatory effects[66]. One study reported increased levels of LPS-positive bEVs in plasma of patients with intestinal barrier dysfunction (e.g., patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and patients with cancer with radiation or chemotherapy-induced intestinal mucositis) in comparison with healthy controls, whereby the concentration of bEVs in plasma may reflect intestinal barrier integrity [67]. Additionally, fluorescently labelled bEVs were shown to distribute to several peripheral organs following oral administration into WT mice, supporting entrance of bEVs into the systemic circulation even through an intact gut barrier[68]. This concept is elegantly supported by a paper demonstrating bEV-derived Cre recombination in various tissues, including the brain, of Rosa26. tdTomato-reporter mice that were intestinally colonized with Escherichia coli engineered to express Cre-recombinase[69]. The available data on functional implications of bEVs in AD are discussed in section 2.5.

2.4. Clinical potential of peripheral EVs

Next to their role in (preclinical) diagnosis, biomarkers are instrumental in monitoring disease progression and evaluating the patients’ response to disease-modifying treatments. In this sense, adequate biomarkers tailored to specifically evaluate the targeted mechanisms of a given treatment (i.e., theramarkers) could aid in demonstrating pharmacodynamic effects and molecular target engagement alongside clinical efficacy. As an additional advantage, applying (EV) theramarkers can shorten clinical trial duration, which could accelerate trials of experimental treatments and help bring them to the clinic faster. In Parkinson’s disease (PD), it was already shown that nEVs can be used as a tool to identify signalling pathways underlying clinical treatment response. In a clinical trial assessing the molecular effects of Exenatide, a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonist, nEVs have revealed that Exenatide augmented insulin signalling via its canonical pathway[70,71]. Specifically, increased levels of IRS-1 phosphorylated at several Tyr residues were detected in nEVs and correlated with clinical scores[70], underlining the potential of nEVs to study both target engagement and treatment responses of a therapeutic intervention. In this context, it is interesting to note that a study of nEVs in a mixed cohort of cognitively normal and MCI, but not demented, individuals found that higher levels of Tyr-phosphorylated IRS-1 and downstream insulin signaling biomarkers were associated with greater temporal lobe volume, but lower volume of white matter hyperintensities, linking brain structure observed by MRI with molecular signatures in nEVs[72]. In a small (under-powered) pilot clinical trial of Exenatide in AD, the only effect observed was a decrease of Aβ42 in nEVs[73]. In addition, in AD several associations with clinical and cognitive scores have been described. In AD patients, serum EV levels of miR-223 correlated positively with Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scores and negatively with serum cytokine levels (i.e., IL-1β, IL-6, CRP and TNF)[20]. Also, decreased nEV levels of synaptic proteins (i.e., SNAP-25[46], synaptopodin[43], synaptophysin[43]) positively correlate with MMSE scores in AD patients whereas the ratio of NPTX2/α-synuclein in APOE ε4 allele carriers negatively correlates with MMSE score[17]. Recently, a study deriving nEVs from plasma samples of pathologically confirmed AD cases found that higher nEV Aβ42 levels were consistently associated with better cognitive status, memory, fluency, working memory and executive function, whereas higher levels of synaptic proteins were associated with better performance on executive function tasks[74]. Several clinically healthy control subjects that were classified as having AD based on a 16-miRNA signature in serum EVs showed high Aβ burden in the brain via PET imaging, potentially identifying them as preclinical AD patients[21]. Higher p-T181-Tau and p-S312-IRS-1 in nEVs have been associated with worse verbal memory in preclinical AD patients[54].

2.5. Biological function of peripheral EVs

An increasing body of data describes the role of EVs in the AD brain, specifically as carriers of disease-associated proteins affecting disease progression[29]. However, apart from their biomarker potential, only a limited number of studies have focused on the functional effects of peripheral EVs in AD. Hereby, these studies focus on selected downstream effects based on the content of the peripheral EVs. Plasma-derived nEVs of AD patients (containing amongst others P-S396-Tau and P-T181-Tau) and to a lesser extent stable MCI patients have shown to induce p-Tau immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of WT mice one month after their intrahippocampal injection, indicating that plasma nEVs could seed Tau propagation[48]. Both AD-derived nEVs and aEVs, known to carry various complement factors[14,15,18,47], can induce membrane attack complex (MAC) formation and subsequent necroptosis in rat cortical neurons in vitro, a process which could be abrogated by addition of the MAC inhibitor CD59[56]. These results suggest that AD patient-derived a/nEVs can contribute to neurodegeneration via complement-mediated mechanisms. Of note, these studies investigate the direct influence of peripheral EVs on the brain, either in vitro or in vivo. These studies are suggestive of an EV-mediated effect that may take place prior to their release into the periphery or upon their (re-)entry into the brain, although no conclusive evidence for the latter has been provided in these studies. In vitro, AD-derived plasma EVs have however been shown to cross human cells forming microvascular structures[15], suggestive of similar in vivo brain barrier crossing. Furthermore, these EVs induced endothelial disruption and astrocyte activation in respective cell cultures, as well as calcium dysregulation in human brain organoids[15].

Also, bEVs derived from Paenalcaligenes hominis (i.e., a gastrointestinal bacterium that is almost nine times as abundant in faeces of elderly in comparison with young adults) were shown to enter the brain upon oral gavage and their administration was associated with an inflammatory response in the hippocampus and the occurrence of cognitive impairment[75]. Vagotomy could prevent this detrimental response, identifying the vagal nerve as an essential player in mediating brain effects (and, perhaps, a means of entry) for bEVs[75]. Upon repeated IV injections in WT mice, faecal AD patient-derived bEVs impaired memory and caused a number of effects in the hippocampus, including blood–brain barrier (BBB) leakage, an inflammatory response (i.e., increased levels of inflammatory cytokines and activation of microglia and astrocytes) and enhanced Tau phosphorylation in comparison with bEVs derived from healthy adults[76]. Of note, low-grade peripheral systemic inflammation induced by LPS (i.e. the major outer membrane component of Gram-negative bacteria and one of the most abundant components of bEVs) affects Aβ deposition and microglia characteristics, amongst others, in APPNL-G-F mice, highlighting the detrimental effect of LPS-induced peripheral inflammation on AD progression[77]. Hereby, it can be speculated that similar effects could be mediated by LPS-containing bEVs. Finally, it has been suggested that bEVs released by Porphyromonas gingivalis (i.e., a Gram-negative anaerobic bacterium involved in the pathogenesis of periodontitis, which has been implicated in AD pathogenesis), could be the responsible actors for the detrimental effect of this bacterium on the AD brain[78]. Together, these data suggest that peripheral EVs contribute to several detrimental processes associated with AD pathology in the brain.

3. Evs as a treatment for AD

Based on their presumed CNS barrier crossing capacity and inherent characteristics including biological cargo protection and low immunogenicity, EVs have been suggested as promising brain (drug) delivery vehicles[79]. In this review, we will discuss the available data on EVs as potential therapeutics for AD.

3.1. Stem cell derived EVs

Stem cells have been proposed as a potential AD treatment, whereby different stem cell classes including neural and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are of interest for therapeutic approaches[80]. Most research has focused on MSCs, which can be derived from multiple sources including bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord-Wharton’s jelly. Their therapeutic potential has been extensively studied in many diseases due to their immunomodulatory properties, amongst others[81]. In AD models, beneficial effects on e.g., Aβ deposition and cognitive function were reported[82]. Although the exact underlying mechanisms of their therapeutic action remain elusive, it is considered unlikely that effects are attributable to the regenerative capacities of MSCs given their limited engraftment and differentiation in vivo [83]. Instead, paracrine actions mediated by the MSC secretome (e.g., cytokines, growth factors, proteins, EVs) are now the center of attention. For example, brain barrier crossing EVs were identified as the responsible actors underlying the beneficial effects of IV-injected umbilical cord MSCs - which could not be detected in the brain - on memory and brain pathology in AD mice[84]. In this review, we will discuss multiple studies that have shown the effectiveness of stem cell-derived EVs - mainly MSC-EVs - in ameliorating brain pathology in AD models, both in vitro and in vivo. We summarize these studies and corresponding experimental details (e.g., stem cell source, EV isolation method and quality control, EV treatment regimen and dose, experimental model and observations) in Table 1.

Table 1.

Stem cell derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) as a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). This table summarizes the experimental setups and readouts of studies on the therapeutic potential of stem cell derived EVs in AD described in this review.

| Stem cells (source) | EV isolation (QC) | Model (age) | Treatment regimen | EV dose | Observations | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neural (human) | UC (NTA, TEM) | 5XFAD Early AD (1.5–2.5 M) Late AD (5–6.5 M) |

Retra-orbital 1x 2x |

2.25×107 particles/ml in 50 μl hibernation buffer | ↑ cognition ↓ Aβ plaques and soluble Aβ levels brain (Thio-S and ELISA) ↓ microglia activation ↑ SYP levels brain ↓ inflammation plasma |

[85] |

| Neural (murine) – inflammatory cytokine preconditioning | DC (NTA, TEM, WB) | APPswe, PS1dE9 (9 M) | icv (bilateral) 2x/week, 4 weeks | 200 μg | ↑ cognition ↑ synaptic protein levels cortex (GAP43, SYP, PSD95, MAP2) ↑ synaptic morphology cortex ↓ inflammatory cytokines cortex ↓ IBA1 cortex ↑ mitochondrial related factors cortex (PGC1a, NRF1, NRF2, FIS1) ↑ oxidative stress markers cortex (4-HNE, 3-NT) ↑ SIRT1 levels cortex |

[86] |

| MSC (human bone marrow) – 3D culture | DC (NTA, TEM, WB) | 5X FAD (8 W) | IN Every 4 days, 4 months |

2×109 particles/ml in 5 μl saline | ↑ cognition ↓ Aβ plaques hippocampus (Thio-S and 6E10) ↓ GFAP and Aβ plaque colocalization in hippocampus |

[87] |

| MSC (human bone marrow) | DC (NTA, WB) | 3X Tg-AD (7 M) | IN | 30 μg, corresponding to 15×109 particles/ml 4.5 μg/ml | ↓ microglia activation cortex and hippocampus | [88] |

| 2x | ↑ dendritic spine density cortex and hippocampus | |||||

| Primary mouse microglia | 24 h | Switch from pro- to anti-inflammatory phenotype | ||||

| MSC (murine bone marrow) – hypoxia preconditioning | EQ (WB) | APPswe, PS1dE9 (7 M) | IV 2x/week, 4 months |

150 μg | ↑ cognition ↓ Aβ plaques cortex and hippocampus (Thio-S and ELISA) ↑ synaptic protein levels brain (GAP43, PSD95, Synapsin1) ↓ astrocyte and microglia activation in cortex and hippocampus ↓ pro-inflammatory cytokines brain ↑ anti-inflammatory cytokines brain ↓ STAT3 phosphorylation brain ↓ NF-kB activation brain ↑ miR-21 levels brain |

[89] |

| Primary rat neurons | 24 h | 50 μg/ml | ↓ Aβ-induced neuronal damage | |||

| BV-2 microglia | 24 h | 50 μg/ml | ↓ LPS-induced inflammation | |||

| MSC (murine bone marrow) | DC (NTA) | APPswe, PS1dE9 (7 M) | IV 1x/month, 4 months RVG-peptide modified EVs |

5×1011 particles/ml in 100 μl PBS | ↑ cognition ↓ Aβ plaques cortex and hippocampus (Thio-S and ELISA) ↓ astrocyte activation brain ↑ cognition ↓ pro-inflammatory cytokines brain ↑ anti-inflammatory cytokines brain |

[90] |

| TEI reagent (TEM, WB) | APP/PS1 | IV Every 2 weeks, 16 weeks |

50 μg | ↑ cognition ↓ Aβ plaques cortex and hippocampus (Thio-S and ELISA) ↑ NeuN levels hippocampus ↑ BACE1, PS1 and NEP levels brain |

[91] | |

| DC (NTA, flow, cryo EM, WB) | APPswe, PS1dE9 (3M + 5M) | Intracortical (bilateral) | 22.4 μg, corresponding to 1×109 particles | ↓ Aβ plaques cortex and hippocampus (6E10) ↓ dysmorphic neurites around Aβ plaques in cortex |

[92] | |

| PEG | APPswe, PS1dE9 | icv | 100 μg | ↑ cognition ↑ synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation |

[93] | |

| Primary cortical neurons, derived from APP/PS1 mice or stimulated with Aβ | 12 h | 100 μg/ml | ↓ iNOS levels | |||

| MSC (rat bone marrow) | DC (TEM, dot blot) | Primary rat hippocampal cultures | 4h 22 h |

8×107 and 2.4×108 particles | ↓ Aβ-induced oxidative stress ↑ synaptic protein levels (SYP, PSD95) |

[94] |

| DC (NTA, TEM, WB) | icv AβO-injection in WT rats | icv 1x/month, 2 months |

30 μg | ↑ cognition ↑ Aβ plaques cortex and hippocampus (Thio-S, 6E10, ELISA) ↓ pro-inflammatory cytokines in brain ↑ NEP and IDE levels brain ↑ miR-29c-3p levels brain ↓ BACE1 levels brain ↑ Wnt- and β-catenin pathway related factors in brain |

[95] | |

| Primary rat hippocampal neurons - AβO stimulation | 24 h | 30 μg | ↓ AβO-induced apoptosis ↓ Aβ deposits (6E10) and levels (ELISA) ↑ miR-29c-3p levels ↓ BACE1 levels ↑ Wnt- and β-catenin pathway related factors |

|||

| Mag-Capture kit | Primary astrocytes | 24 h | 0.4 μg/ml | ↑ miR-146a levels ↓ TRAF6 and NF-kB levels |

[96] | |

| MSC (human adipose tissue) | DC (NTA, TEM, WB, DLS) | APP/PS1 (9 M) | IN Every 2 days, 2 weeks |

10 μl of 1 mg/kg | ↑ cognition ↓ neuronal damage hippocampus ↑ neurogenesis hippocampus ↓ Aβ plaques cortex and hippocampus (6E10) ↓ microglia activation cortex and hippocampus |

[97] |

| Primary mouse neuronal cultures | 24 h | 0.05–1 μg/ml | ↓ AβO- and glutamate-induced neuronal damage ↑ genes involved in neurogenesis |

|||

| EQ (WB) | Neuronal stem cells from subventricular zone TG2576 mice | 24 or 48 h | 200 μg/ml | ↓ Aβ levels (ELISA) ↓ apoptosis ↑ neurite outgrowth |

[98] | |

| MSC (human Wharton’s jelly) – 2D versus 3D scaffold | DC (NTA, TEM, WB) | APPswe, PS1dE9 (9 M) | Intrahippocampal Continuously (Alzet minipump), 14 days | 2 mg/ml, 0.25 μl/h | ↑ cognition ↓ Aβ deposits (Aβ42 antibody) ↑ ADAM10 hippocampus ↓ BACE1 hippocampus ↓ microglia hippocampus ↓ pro-inflammatory cytokines hippocampus ↓ oxidative stress markers hippocampus |

[99] |

| APPswe expressing SH-SY5Y cells | 24 h | 2 μg | ↓ cellular and secreted Aβ levels (ELISA) ↑ ADAM10 ↓ BACE1 |

|||

| MSC (human Wharton’s jelly) | DC (NTA, TEM, FACS) | Primary rat hippocampal cultures - AβO stimulation | 4h 22 h |

6.1×107 and 1.8×108 particles | ↓ AβO-induced oxidative stress ↑ Synaptic protein levels (SYP, PSD95) |

[100] |

| DC (NTA, TEM, WB) | APPswe, PS1dE9 (9 M) | IV 1x |

50 μg | ↑ cognition ↓ Aβ plaques in hippocampus (Thio-S, 6E10, WB) ↓ neuronal loss hippocampus ↑ synaptic morphology hippocampus ↑ neuronal excitability hippocampus ↑ mitochondrial morphology hippocampus ↓ oxidative stress markers hippocampus |

[101] | |

| Primary mouse hippocampal cultures - AβO stimulation | 12 h | 10 μg/ml | ↑ alteration in calcium transient | |||

| APPswe expressing SH-SY5Y cells | 12 h | 10 μg/ml | ↓ oxidative stress markers | |||

| Exo-Prep (NTA, TEM, WB) | J20 mice | IV 1x/week, 4 weeks |

50 μg | ↑ cognition ↑ glucose metabolism brain ↓ astrocyte activation brain ↑ plasticity related genes ↓ Aβ levels brain (WB) ↓ HDAC4 cortex |

[102] | |

| APPswe/London expressing SH-SY5Y | 2x/week | 50 μg | ↓ cellular Aβ levels ↑ plasticity related genes ↓ HDAC4 levels |

|||

| EQ (TEM, WB) | APPswe, PSldE9 (7 M) | IV 2x/week, 2 weeks |

30 μg | ↑ cognition ↓ Aβ plaques in cortex and hippocampus (Thio-S, ELISA) ↑ NEP and IDE levels brain ↓ microglia in cortex and hippocampus ↓ pro-inflammatory cytokines brain ↑ anti-inflammatory cytokines brain |

[103] | |

| BV-2 microglia – Aβ stimulation | 24 h | 30 μg/ml | Switch to anti-inflammatory phenotype | |||

| MSC (human, undefined) | DC (WB) | Intrahippocampal Aβ aggregate injection in WT mice | Intrahippocampal injection 1x | 10 μg | ↑ cognition ↑ neurogenesis in subventricular zone |

[104] |

Abbreviations: 3-NT: 3 nitrotyrosine; 4-HNE: 4-hydroxynonenal; Aβ: amyloid beta; AβO: amyloid β oligomer; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; ADAM10: A disintegrin and metalloprotease 10; BACE1: β-site APP cleaving enzyme-1; DC: differential centrifugation; DLS: dynamic light scattering; EQ: ExoQuick; FACS: fluorescence-activated cell sorting; FIS1: fission 1; GAP43: growth-associated protein 43; GFAP: Glial fibrillary acidic protein; HDAC4: Histone deacetylase 4; IBA1: ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1; IDE: insulin degrading enzyme; IN: intranasal; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; IV: intravenous; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; MAP2: microtubule-associated protein 2; MSC: mesenchymal stem cell; NEP: neprilysin; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NRF: nuclear respiratory factor; NTA: Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis; PEG: polyethylene glycol; PGC1α: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α; PS1: Presenilin 1; PSD95: post-synaptic density 95; QC: quality control; RVG: rabies virus glycoprotein; SIRT1: sirtuin 1; STAT-3: signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; SYP: synaptophysin; TEI: Total Exosome Isolation; TEM: transmission electron microscopy, Thio-S: thioflavin-S; TRAF6: tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6; UC: ultracentrifugation; WB: western blot.

In 5XFAD AD mice, stem cell-derived EVs were shown to mitigate anxiety-like behavior[85] and rescue cognitive decline[87]. A similar protective effect against memory deterioration was observed in APP/PS1 mice[86,89–91,93,97,101,103], J20 mice [102] and AβO injection rodent models (i.e., intracerebroventricular (icv) injection[95] and intrahippocampal injection[104]). Different underlying mechanisms accounting for these profound results were proposed, including an MSC-EV-mediated neuroprotective mode of action. Indeed, MSC-EV treatment reduced neuron loss [91,92,97,101], benefited neuronal function (i.e., neuronal excitability[101], synaptic transmission[93], long-term potentiation[93]), increased neurogenesis[97,104], improved synaptic morphology (e.g., dendritic spine density)[86,88,101] and restored brain levels of various synaptic proteins including synaptophysin to those in WT littermates[85,86,89,102]. Accordingly, proteomic analysis of MSC-EVs revealed the presence of a variety of neuroprotective proteins[97] whereby EV treatment protected against neurotoxicity induced by several triggers (i.e., AβO and glutamate) in vitro[89,95,97,100]. Also, EVs secreted by adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) attenuated apoptosis and increased neurite outgrowth in neuronal stem cells isolated from TG2576 AD mice [98]. MSC-EV treatment via different administration routes resulted in a reduction in Ab levels and/or plaque load in a variety of rodent models (5XFAD[85,87], APP/PS1[89–92,97,99,101,103], and AβO icv injection[95]) and in multiple brain regions including the prefrontal cortex, amygdala and hippocampus. These results suggest that MSC-derived EVs could either interfere with Aβ formation or accelerate its clearance, as indicated by results showing a restoration of altered proteins levels involved in the generation (i.e., BACE1[91,95,99], PS1[91]) or reduction (i.e., NEP[91,95,103], IDE[95,103], ADAM10[99]) of pathological Aβ in the rodent AD brain. Similarly, MSC-EVs could reduce both BACE1[95,99] and Aβ[95,99,102] levels in APP-transfected SH-SY5Y cells[99,102] and AβO-stimulated hippocampal neurons[95]. ADSC-derived EVs reduced Aβ levels in murine AD neuronal stem cells as well[98]. Furthermore, both systemic and central anti-inflammatory effects of MSC-EV treatment were reported in AD mice as evident by a reduction in inflammatory cytokines in plasma[85] and brain[89,90,95,99,103], as well as an increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines in plasma[103] and brain [89,90,103]. Furthermore, a decrease in activated microglia [85,86,88,89,97,99,103] and astrocytes[87,89,90,102] was reported in multiple studies. Potentially linked to the latter outcome are the reduction in STAT3 phosphorylation and inhibition of NF-κB activation in the brain of MSC-EV treated APP/PS1 mice[89], as these pathways are involved in glial activation[105]. Also, in a mouse model for Niemann-Pick type 1 disease (NPC1) - sometimes referred to as childhood AD - MSC-EVs were shown to exert innate immune modulatory activities by reducing neuroinflammation, microgliosis and astrogliosis[106]. In vitro, MSC-EV treatment prevented the transition of BV-2 cells[89,103] and primary microglia [88] towards a pro-inflammatory phenotype upon stimulation with various triggers (i.e., LPS[89], Aβ[103], TNF and IFNγ[88]). These results are important given the central role of (neuro)inflammation in AD, whereby sustained microglial and astrocytic activation along with excessive secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines are critical regulators of neurodegeneration[107,108]. Oxidative stress is another mechanism implicated in the pathogenesis of AD[109]. Indeed, altered levels of several oxidative stress-related proteins are found in AD models and these alterations are reversed by MSC-EV treatment, both in vitro[94,100,101] and in vivo [86,99,101]. Similarly, MSC-EVs reduced the elevated inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) levels that were observed in primary cortical neurons either stimulated with Aβ or derived from APP/PS1 mice[93]. Aberrant levels of histone deacetylases (HDACs) are reported in the AD brain and have been linked to cognitive function[110], whereby MSC-EVs could restore the increased HDAC4 levels in the AD mouse brain and APP-transfected SH-SY5Y cells[102]. Beneficial effects on mitochondria were reported in APP/PS1 mice, where neural stem cell-EV[86] or MSC-EV[101] treatment resulted in the upregulation of several genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis (including SIRT1) in the cortex[86] and the improvement of mitochondrial morphology in hippocampal neurons[101]. MSC-EVs also affect the dysregulated sphingolipid pathway in AD[111] since pretreatment of APP/PS1 mice with inhibitors against sphingosine kinase (SphK) or sphingosine 1 phosphate (S1P) 1 receptor abolished the beneficial effects of the MSC-EV treatment on AD brain pathology[91]. Finally, MSC-EV treatment improved the decreased glucose metabolism in the brain of J20 AD mice[102]. For experimental details about the treatment regimen (e.g., EV administration route) applied in these studies, we refer to Table 1.

Evidently, MSC-EVs intervene at various processes involved in AD pathogenesis. Hereby, several MSC-EV associated molecules that could contribute to their mechanism of action have been identified. It was for instance shown that MSC-EVs contain the (enzymatically active) Aβ-degrading enzyme NEP[92,99,102,112] and the antioxidant enzyme catalase[94,100]; inhibiting catalase activity prevented the MSC-EV-mediated protective effect on AβO-induced oxidative stress and synapse damage in primary hippocampal neurons[94,100]. Moreover, a variety of miRNAs with potential neuroprotective roles have been identified in MSC-EVs [85,89,95,99,102]. EVs derived from hypoxia-pretreated MSCs contain elevated levels of miR-21, and treatment with these EVs increased the miR-21 levels in the brain of APP/PS1 mice[89]. The beneficial effects of the MSC-EV treatment on brain pathology and memory function in these mice were replicated upon lentiviral overexpression of miR-21 in the hippocampus, underlining the involvement of MSC-EV derived miR-21 as a mechanism of action[89]. Similarly, miR-29c-3p was shown to be essential in inducing the beneficial effect of MSC-EVs on Aβ levels and neuronal survival in vitro, whereby an MSC-EV miR-29c-3p-mediated activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and associated BACE1 reduction in target cells was proposed as another mechanism of action[95]. Also, miR-146a containing MSC-derived EVs increased the miR-146a levels in astrocytes in vitro, whereas levels of several downstream targets including NF-κB were decreased[96]. This mechanism was described to contribute to the beneficial effects (e.g., decrease in astrocytic inflammation) observed upon MSC-EV transplantation in APP/PS1 mice[96]. Of importance, skepticism has been raised considering the potential biological relevance of extracellular RNA (exRNA), including miRNA, in EVs. Indeed, it has been suggested that most EVs only contain very low and therefore biologically irrelevant levels of exRNA[113]. Furthermore, when aiming to unravel the role of exRNAs in EVs, various quality control considerations are essential to control for confounding effects mediated by other carrier molecules or experimental manipulations[114]. Given that these rigorous controls are mostly lacking in the published literature, the biological role for exRNA in EVs currently remains controversial[114].

Several strategies have been explored to further optimize the MSC-EV treatment for AD management. Hypoxia preconditioned MSCs released EVs exert an enhanced improvement on memory, plaque levels and brain inflammation in APP/PS1 mice compared to EVs derived from normoxic MSC-EVs[89]. Similar results were obtained with EVs derived from MSCs that were cultured on a 3D scaffold in comparison with a 2D film[99]. Profound differences in EV content depending on the culture conditions of the source cells were observed, whereby EVs derived from MSCs cultured on a 3D scaffold were enriched in certain miRNAs and Aβ-degrading enzymes (i.e., NEP and IDE), amongst others[99]. To enhance the immunomodulatory capacities of MSCs, preconditioning with inflammatory cytokines (i.e., TNF and IFNγ) was applied, with secreted EVs reducing microglia activation in 3x Tg mice, although no comparison was made with EVs derived from non-preconditioned MSCs[88]. In addition to adaptations focused on the EV-secreting MSCs, EV modifications (e.g., cargo loading, surface engineering) represent an intense area of research. Transfection of bone-marrow derived MSCs with miR-29b resulted in the release of EVs containing elevated miR-29b levels, which reduced AβO-induced cognitive decline upon their intrahippocampal injection in a rat AD model[115]. Furthermore, efforts are made to enhance the brain targeting capacity of peripherally administered EVs. Targeting moieties can be introduced on the surface of EVs, either by modifying the EV-releasing cells (i.e., pre-isolation modification) or the EVs themselves (i.e., post-isolation modification) by various strategies, as reviewed elsewhere[116]. Several brain targeting ligands have been explored, including the rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG) to target the acetylcholine receptor on neuronal and brain endothelial cells[117] and peptides to target the transferrin receptor[118] or the low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor[119] expressed on brain endothelial cells and glioblastoma tumors. In the field of AD, chemical EV modification (i.e., using an N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester linker) has been applied to conjugate MSC-EVs with RVG. Hereby, the RVG-modified MSC-EVs showed enhanced brain targeting capacity upon IV injection compared to native MSC-EVs and accordingly impacted cognitive function, plaque deposition and brain inflammation more profoundly[90].

3.2. Evs derived from other sources

In addition to stem cell derived-EVs, modified EVs derived from other sources have been investigated for their therapeutic potential in AD. The RVG-based strategy was first applied in a genetic engineering model making use of Lamp2b, a protein that is enriched in the EV membrane. More specifically, dendritic cells were transfected with an RVG-Lamp2b construct, resulting in the incorporation of RVG in EVs released by the cells. After electroporation-mediated loading of these EVs with siRNA targeting BACE1 and IV injection into WT mice, both a reduction in BACE1 and Aβ1–40 levels was observed in the cortex[117]. These results highlight the possibility of targeting potential AD targets by peripheral administration of modified EVs[117]. Curcumin has been suggested as a potential therapeutic for AD, although its low bioavailability imposes an important disadvantage[120]. Curcumin loading in EVs by means of curcumin pretreatment of RAW 264.7 macrophages, however, positively influenced its solubility and degradation rate, as well as its pharmacokinetic profile upon IV injection into WT rats[121]. Consecutive intraperitoneal (IP) injection of these EVs over the course of 7 days in an AβO intrahippocampal injection rat model reduced neuronal loss and attenuated cognitive decline, amongst others, whereby these beneficial effects were more pronounced compared to curcumin treatment alone[121].

3.3. Brain delivery of therapeutic EVs

Crossing the tight brain barriers is one of the most important hurdles to overcome when delivering therapeutics to the brain. Accordingly, EVs are put in the spotlight given their theoretical suitability for in vivo brain targeting[79]. Despite the magnitude of brain-centered therapeutic effects described in the literature, a systematic review soberingly showed that peripherally administered EVs mainly accumulate in peripheral organs (e.g., liver, lungs, kidneys, spleen), whereas brain delivery is limited[122]. For the MSC-EV studies summarized in Table 1, some central administration routes (i.e., icv injection[86,93,95], and intrahippocampal injection[99,104]) were described although most studies applied more clinically-relevant peripheral administration regimens. In these studies, brain delivery has been indirectly deduced from the observed effects of the MSC-EV treatment in the AD rodent brain rather than actually demonstrated, although some papers also directly investigated EV biodistribution. Upon nasal administration, MSC-EVs stained with different dyes (i.e., Vybrant DiO[87], PKH-26[88], or [125]I-label[97]) were detected throughout the brain in a multitude of analyzed brain regions (e.g., cortex [87,88,97], hippocampus[88,97], olfactory bulb[97], and cerebellum[97]) at various timepoints after injection (i.e., 1 h[97], 6 h[88], 24 h[87]). A more in-depth analysis of intranasally administered PKH-26 labeled MSC-EVs revealed that they were mostly taken up by neurons and less by microglia and astrocytes in the olfactory bulb and cortex[97], whereas another study described a more pronounced uptake by microglia and to a lesser extent neurons, but not astrocytes, in the hippocampus[88]. The presence of C5 Maleimide-Alexa 594 labeled EVs in hippocampal neurons was also reported 24 h after their IV injection[101]. IV injected, DiI-labeled MSC-EVs were detected in the cortex and hippocampus 5 h after injection[89,90], more specifically in astrocytes and microglia[89], as well as in the lungs and spleen[89]. Similarly, PKH-26 labeled MSC-EVs were traced back both to the liver and in the brain 3 h after IV injection[102]. In vitro studies also support the uptake of labeled MSC-EVs (i.e., PKH-26[95,96], DiO[99], DiI [100]) by astrocyte cultures[96], SH-SY5Y cells[99], hippocampal neurons[95] and hippocampal cultures containing neurons and glial cells[100]. In the latter condition, the uptake was more pronounced upon AβO stimulation of the cells and was mainly mediated by astrocytes[100].

Although these studies collectively indicate EV brain delivery and/or EV uptake by brain cells, results should be interpreted with caution. Indeed, there is an important difference between distribution of EVs to specific regions - mostly studied at the organ level - and functional delivery of the EV cargo to its subcellular targets. The lipid dyes applied in MSC-EV AD research come with several pitfalls, including nonspecific labeling of non-EV particles and the presence of unbound dye as well as aggregate formation by the dye[123]. Together, these issues pose the risk of artifactual results and false interpretations. To deduce EV cargo delivery, specific experimental approaches (e.g., state-of-the-art imaging techniques and implementation of rigorous controls, such as effective washing of unbound dye) are required[123] but not generally implemented to support experimental conclusions. Of note, signaling may not always require uptake and/or cargo transfer as EVs can also bind to membrane receptors, triggering downstream signaling via adaptor proteins[124]. Altogether, current literature is supportive of the therapeutic capacity of peripherally administered EVs in AD models, despite the need of additional research to clarify the underlying molecular mechanisms of their brain effects.

4. Practical considerations towards EVs as biomarkers and therapeutics

Despite promising results in various model systems, it remains important to reflect on potential limitations of EVs as a treatment for AD. Some of these apply to the interpretation of the obtained results (e.g., as discussed for the brain delivery of therapeutic EVs), others to the clinical translatability of EV treatments applied to model systems. Similar practical hurdles need to be taken into account when exploring EVs as biomarker sources. Here, we briefly discuss several considerations, specifically focusing on the results obtained with stem cell-derived EVs as therapeutics and blood-derived EVs as biomarker sources in the AD field. For a more elaborate discussion on this topic, we refer to other reviews including [79,125,126].

Experimental procedures involving EVs are multi-step processes, whereby decisions in each step of the process will influence the final experimental outcome. Therefore, meticulously reporting all experimental variables as suggested by the transparent reporting and centralizing knowledge in EV research (EV-TRACK) initiative[127] and the MISEV guidelines[3] as well as following general recommendations proposed by the EV community [140] and the task forces (e.g., blood[128], urine[129], saliva, and CSF) of the International Society of Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV), is of major importance to support the translation of EVs to the clinic.

Prior to isolation of EVs from a given biofluid, several pre-analytic variables need to be considered (e.g., collection procedures, storage conditions, and processing protocols). For example, plasma is preferred over serum in EV research since the clotting process during serum preparation induces EV release by activated platelets. Hereby, citrate is recommended by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis as anticoagulant of choice[130]. Although the impact of storage conditions on biofluids is under investigation (for example reviewed in[131,132]), no general guidelines are available yet, but recommendations are expected to be proposed by the ISEV task forces. EVs can be separated from biofluids by a wide variety of bulk EV isolation techniques, which all come with their own strengths and drawbacks. Generally, trade-offs need to be made between purity, yield and scalability, which are inversely correlated. Indeed, consecutive EV isolation steps using different methodologies generate purer EV samples but with lower yield and are also more labour-intensive and therefore low throughput. As such, they are unsuitable for large scale biomarker studies or treatment regimens requiring high amounts of EVs. In stem cell EV-focussed AD research (Table 1), isolation methods based on EV density (i.e., differential centrifugation), size (i.e., ultracentrifugation), and biological composition (e.g., precipitation-based methods including ExoQuick) have been applied. Hereby, large variability in inclusion of quality control measures according to the MISEV guidelines[3] has been implemented. This poses an additional challenge in comparing and interpreting data obtained by different studies. Enrichment for specific EV subtypes typically requires affinity-based separation protocols whereby the choice of cell-type specific surface markers and corresponding antibodies is a core requirement. Ideally, a surface marker should be expressed on the surface of EVs, be highly expressed on the cell-type of interest, be cell-type specific and be bound by available antibodies with high affinity and specificity. Hereby, it is essential to also report the antibody clone, as for example in case of L1CAM different antibody clones with distinct binding epitopes are being used in the field[34]. Although IP-based protocols are relatively straightforward to implement and do not require a high-end infrastructure, they do contain multiple steps subjective to inter-laboratory variability (e.g., washing steps, and choice of beads and elution buffer). Studies comparing these experimental variables are warranted to develop a standardized protocol.

For EVs as therapeutic agents, multiple parameters define the EV treatment regimen, including EV dose, administration route, treatment frequency, and duration. A large variability across these parameters is present among published studies. As evident from Table 1, the EV dose is either based on particle number or total protein amount but differs substantially among studies. Variability in the experimental methods used to determine these measures adds an additional layer of complexity in comparing obtained results. Indeed, particle concentrations determined by NanoSight or ZetaView are known to differ significantly[133] and similar discrepancies exist between methods to determining protein concentration (e.g. Bradford or micro-bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assays). Furthermore, both NTA and protein determination are skewed by the number of contaminating soluble (lipo)proteins remaining in the sample after EV isolation, which again varies based on the applied isolation method. Of note, also in the case of biomarker studies, levels of markers of interest may be influenced by the presence of non-EV associated proteins whereas variability in methods to determine the levels of potential biomarkers (e.g. ELISA, MesoScale, and Simoa) will affect measurement sensitivity. A meta-analysis of 64 different pre-clinical studies across numerous disease areas revealed large inconsistencies in applied EV doses, with study authors suggesting the adoption of functional and qualitative (e.g. EV potency, and quantity of effector molecules) instead of quantitative (e.g. particle number, and protein amount) parameters in determining EV dose[134]. Furthermore, the frequency of administration varied from a single to multiple to continuous injections over the time course of weeks to months (Table 1). As for the EV dose, any rationale behind the selected administration schedules is often absent and comparisons between regimens are generally lacking. Another important consideration encompasses storage conditions of EVs. Although general guidelines are still lacking, in general, siliconized vessels are advised as storage containers to prevent adherence of EVs to the container surface[135]. Very recently, the use of PBS supplemented with human albumin and trehalose (PBS-HAT) was shown to improve both short- and long-term storage of EVs at −80 °C[136].

In conclusion, to deliver on the promise and optimism stimulated by findings of neural stem cell-derived EVs in preclinical AD models, standardization efforts regarding EV-related parameters (e.g., storage, isolation, and dose) and treatment regimen (e.g., administration route, treatment frequency, and treatment duration) are warranted. Similar standardization will benefit the field exploring EVs as biomarker sources, whereas high-throughput EV isolation methods and optimized storage conditions will facilitate the needed expansion of results obtained in smaller cohorts to the population at large.

5. Conclusions

To facilitate the development of effective treatments for AD, it is imperative to detect the disease at its preclinical and, potentially, modifiable stage, before brain damage is irreversible. This underlines the pressing need for developing biomarkers for preclinical and early clinical diagnosis when patients might benefit the most from disease-modifying drugs once these become available. Additionally, biomarkers are also instrumental for monitoring disease progression and evaluating the patients’ response to treatments. In this sense, biomarkers tailored to specifically evaluate the targeted mechanisms of a given treatment could aid in demonstrating target engagement, shorten clinical trial duration and accelerate therapeutic development. Currently accepted biomarkers for AD are CSF- and imaging-based, implying several limitations and warranting the need for research into novel biomarkers which should preferentially be derived from easily accessible biofluids, rely on widely available technologies, and incur low cost-requirements. EVs isolated from peripheral biofluids (e.g., blood) tick all these boxes whereby a growing number of publications supports their biomarker potential in AD and other neurodegenerative diseases. Nonetheless, studies to directly compare the biomarker potential between unprocessed plasma, bulk EVs and specific EV subtypes (e.g., nEVs, and aEVs) are warranted and will be instrumental to guide the choice of EV subtypes in the biomarker field. Given the heterogeneity of AD pathogenic mechanisms, biomarkers will also allow for better selection of patients for clinical trials that target mechanisms that might be specific to certain disease stages or patient subpopulations, according to the principles of precision medicine. As such, EV biomarkers can aid the optimization of clinical trial design and therefore the development of AD treatments [137,138]. Hereby, neural stem cell-derived EVs have been proposed as potential therapeutic agents based on promising results in preclinical studies using AD models showing that MSC-EVs intervene at various processes involved in AD pathogenesis. Advantages inherently linked to EVs as treatment modalities include their low immunogenicity and presumed CNS barrier crossing capacity, allowing them to elicit a therapeutic response upon peripheral administration. In conclusion, the literature discussed in this review provides optimism for the potential of peripheral EVs as biomarkers and treatment modalities. However, several challenges inherent to the EV field currently restrict the translatability of EV-based biomarkers and their use as brain delivery vehicles. The most important factors include scalability, which is inherently linked to the availability of source material and EV isolation methods, storage conditions of EVs and/or their originating biofluid (e.g. culture medium, and plasma), and translatability from animal models to humans or from small cross-sectional cohorts to large longitudinal cohorts. Standardization efforts in these areas will be instrumental in paving the way for EVs towards the clinic.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Special Research Fund (BOF) of Ghent University, the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO Vlaanderen; V417921N), the Foundation for Alzheimer’s Research (SAO-FRA), VIB, the Baillet Latour Fund, and the Intramular Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, NIH. The Figures were created using BioRender.com.

Abbreviations:

- 3-NT

3 nitrotyrosine

- 4-HNE

4-hydroxynonenal

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADAM

A disintegrin and metalloprotease

- ADSC

Adipose-derived stem cell

- aEVs

Astrocyte-derived extracellular vesicles

- AMPA4

GluA4-containing glutamate

- ANGPTL-4

Angiopoietin-like 4

- APOE

Apolipoprotein E

- APP

Amyloid precursor protein

- Aβ

amyloid beta

- AβO

Amyloid β oligomer

- BACE1

β-site APP cleaving enzyme-1

- BBB

Blood-brain barrier

- BO

Beads only

- bEVs

Bacterial extracellular vesicles

- CDR

Clinical dementia rating

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CSPG4

Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4

- DAF

Decay-accelerating factor

- DC

Differential centrifugation

- DLS

Dynamic light scattering

- e.g.

exempli gratia – for example

- EQ

ExoQuick

- EVs

Extracellular vesicles

- FACS

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- FGF

Fibroblast growth factor

- FIS1

Fission 1

- FTD

Frontotemporal dementia

- FXIII

Coagulation factor XIII

- GAP43

Growth-associated protein 43

- GDNF

Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- GLAST

Glutamine aspartate transporter

- GLP-1

Glucagon-like peptide 1

- HDAC

Histone deacetylase

- HGF

Hepatocyte growth factor

- HSF1

Heat-shock factor-1

- HSP70

Heat-shock protein 70

- HYDIN

Hydrocephalus-inducing protein homolog

- i.e.

id est – that is

- IBA1

Ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- icv

Intracerebroventricular

- IDE

Insulin degrading enzyme

- IFNγ

Interferon gamma

- IGF1

Insulin-like growth factor 1

- IL

Interleukin

- iNOS

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IP

Immunoprecipitation

- IP

Intraperitoneal

- iPSC

Induced pluripotent stem cell

- IRS-1

Insulin receptor substrate-1

- IV

Intravenous

- L1CAM

L1 cell adhesion molecule

- LAMP

Lysosome-associated membrane protein

- LDL

Low density lipoprotein

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- LRP6

Lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6

- MAC

Membrane attack complex

- MAP2

Microtubule-associated protein 2

- MCI

Mild cognitive impairment

- MISEV

Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles

- MMSE

Mini mental state examination

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MSC

Mesenchymal stem cell

- Mt-RNA

Mitochondrial RNA

- NCAM

Neural cell adhesion molecule

- NEP

Neprilysin

- nEVs

Neuronal-derived extracellular vesicles

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NHS

N-hydroxysuccinimide

- NLGN1

Neuroligin 1

- NPC1

Niemann-Pick type 1 disease

- NPTX2

Neuronal pentraxin 2

- NRF

Nuclear respiratory factor

- NRGN

Neurogranin

- NRXN2α

Neurexin 2α

- NTA

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis

- ORM2

Orosomucoid 2

- p-Tau

Phosphorylated Tau

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PDGFRα

anti-platelet growth factor receptor α

- PEG

Polyethylene glycol

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- PGC1α

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α

- PS1

Presenilin 1

- PSD95

Post-synaptic density 95

- QC

Quality control

- RBP4

Retinol-binding protein 4

- REST

Repressor element 1-silencing transcription factor

- ROC

Receiver operating curve

- RVG

Rabies virus glycoprotein

- S1P

Sphingosine 1 phosphate

- sAPP

soluble APP

- SEC

Size Exclusion Chromatography

- SIRT1

Sirtuin 1

- SNAP-25

Synaptosomal-associated-protein 25

- SphK

Sphingosine kinase

- STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- t-Tau

Total Tau

- TEI

Total exosome isolation

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- Thio-S

Thioflavin-S

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- TRAF6

Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6

- UC

Ultracentrifugation

- WB

Western blot

- WT

Wild-type

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].van Niel G, D’Angelo G, Raposo G, Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19 (4) (2018) 213–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].van Niel G, Carter DRF, Clayton A, Lambert DW, Raposo G, Vader P, Challenges and directions in studying cell–cell communication by extracellular vesicles, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 23 (5) (2022) 369–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]