Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the association between operative time and postoperative outcomes.

Summary Background Data:

The association between operative time and morbidity after pulmonary lobectomy has not been characterized fully.

Methods:

Patients who underwent pulmonary lobectomy for primary lung cancer at our institution from 2010 to 2018 were reviewed. Exclusion criteria included clinical stage ≥IIb disease, conversion to thoracotomy, and previous ipsilateral lung treatment. Operative time was measured from incision to closure. Relationships between operative time and outcomes were quantified using multivariable mixed-effects models with surgeon-level random effects.

Results:

In total, 1651 patients were included. Median age was 68 years (interquartile range, 61–74), and 63% of patients were women. Median operative time was 3.2 h (interquartile range, 2.7–3.8) for all cases, 3.0 h for open procedures, 3.3 h for video-assisted thoracoscopies, and 3.3 h for robotic procedures (p=0.0002). Overall, 488 patients (30%) experienced a complication; 77 patients (5%) had a major complication (grade ≥3), and 5 patients (0.3%) died within 30 days of discharge. On multivariable analysis, operative time was associated with higher odds of any complication (odds ratio per hour, 1.37 [95% CI, 1.20–1.57]; p<0.0001) and major complication (odds ratio per hour, 1.41 [95% CI, 1.21–1.64]; p<0.0001). Operative time was also associated with longer hospital length of stay (beta, 1.09 [95% CI, 1.04–1.14]; p=0.001).

Conclusions:

Longer operative time was associated with worse outcomes in patients who underwent lobectomy. Operative time is a potential risk factor to consider in the perioperative phase.

Mini-Abstract

This study investigated the association between operative time and postoperative outcomes after pulmonary lobectomy. Longer operative time was associated with longer hospital length of stay and higher odds of experiencing both any complication and major complication. Operative time is a potential risk factor to consider in the perioperative phase.

Introduction

Numerous risk factors for morbidity and mortality have been identified among patients undergoing pulmonary resection.1–5 Risk mitigation involves identifying modifiable risk factors; certain patient characteristics, such as body mass index (BMI) and tobacco use, and type of procedure are potential points of intervention to reduce complications.6,7 However, few data exist on the association between operative time and postoperative outcomes.

Operative time is influenced by several factors. From incision to exposure and closure, substantial differences may exist between open and minimally invasive surgery (MIS). Procedure duration may be longer for MIS, given the need for video equipment setup and robot docking. However, certain operative aspects may be faster in MIS, given the greater visualization of structures afforded. Intraoperative factors such as adhesions, fissure status, aberrant anatomy, extent of lymphadenectomy, hemostasis, aerostasis, and need for frozen section results and subsequent halt for pathologic diagnosis also variably influence operative duration. Anesthetic considerations, such as difficulty maintaining single-lung ventilation, can also add to operative time.

Whereas operative time has been associated with the risk of thromboembolic events and surgical site infections,8,9 its association with outcomes after pulmonary lobectomy has been evaluated less directly. Operations requiring more time may represent more-challenging procedures and thus may have a greater potential for postoperative morbidity. We sought to (1) summarize the distribution of operative times for open and MIS standard pulmonary lobectomy (anatomic lobar resection performed in selected patients with limited disease stage), (2) quantify the relationship between operative time and postoperative outcomes, and (3) compare operative time and outcomes by operative approach and surgeon experience level. We hypothesized that longer operative time is independently associated with poorer postoperative outcomes.

Patients and Methods

Study Cohort

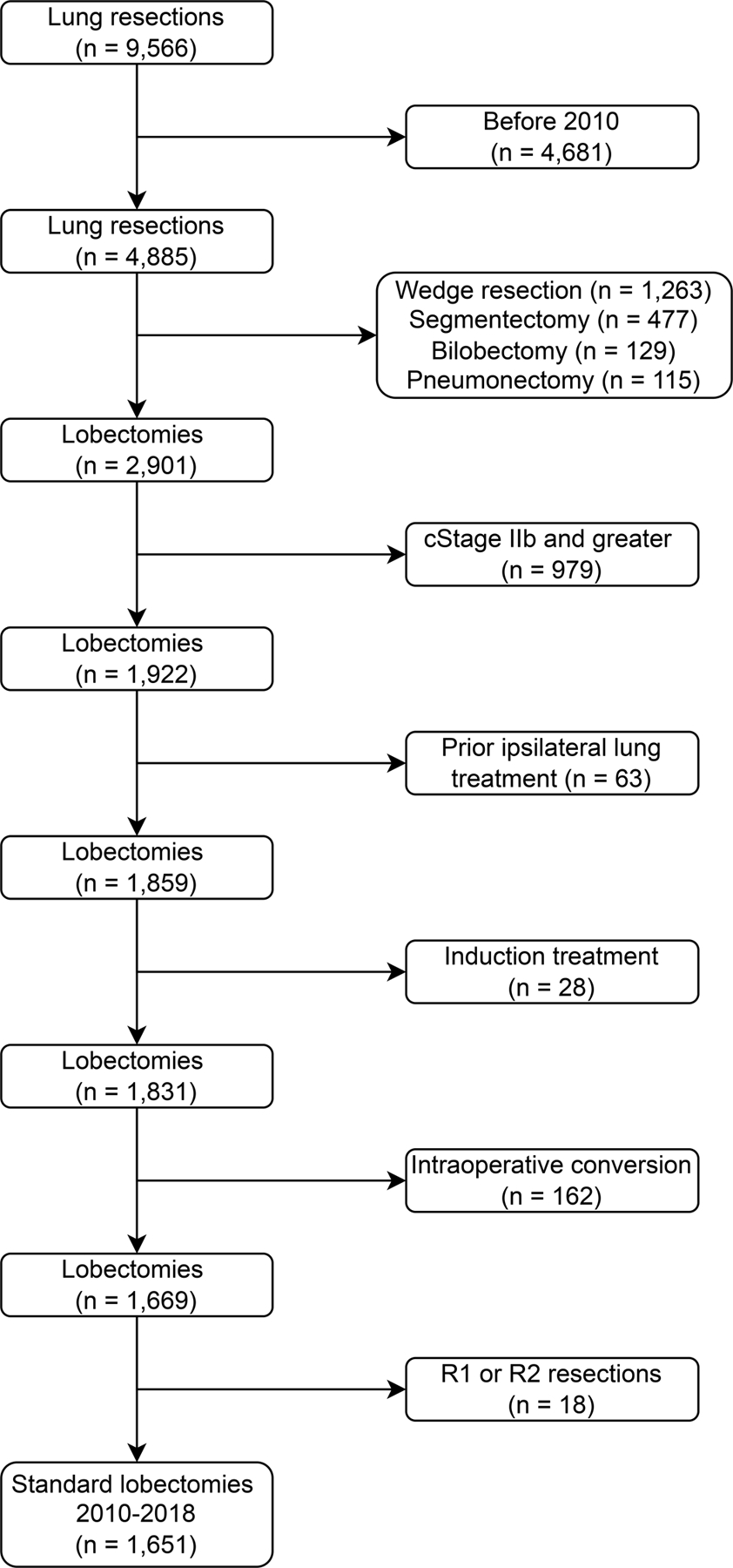

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (protocol #18–391). All adults undergoing pulmonary resection at our center were identified retrospectively using our institution’s prospectively maintained Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery database. Exclusion criteria are described in Figure 1. Standard lobectomy was defined as any R0 lobectomy performed to resect localized disease in a previously untreated lung and without the need for intraoperative conversion from MIS to open. Patients were staged using the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor-node-metastasis guidelines.10 To account for the learning curve required for MIS approaches, which were increasingly used during the study period, patients treated before January 2010 were excluded. Operations were performed by board-certified thoracic surgeons, with trainee involvement, at an academic medical center.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of the study population.

Extracted data included demographic information, medical and surgical history, preoperative pulmonary function tests (forced expiratory volume in the first second [FEV1] and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide [DLCO]), tumor characteristics, and operative information. All patients without preoperative tissue biopsy underwent intraoperative frozen section. We defined surgeon experience level by calculating years in practice from completion of the cardiothoracic surgery fellowship to the date of the lobectomy.

Exposure of Interest and Outcomes

The primary exposure of interest was total operative time. Operative time was calculated, in hours, as the time from skin incision to skin closure based on operating room records. We also calculated nonoperative suite time by subtracting the operative time from the total time the patient spent in the operating suite. Nonoperative suite time included the time required for positioning, induction of and emergence from anesthesia, and moving the patient out of the operating suite. The primary outcomes of interest included any postoperative complication and major postoperative complication (grade ≥3; according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0). Secondary outcomes of interest included performance of an unplanned procedure after lobectomy and during the index admission (including return to the operating room, bronchoscopy, and procedures performed by interventional radiology), hospital length of stay (LOS) in days, and hospital readmission and mortality within 30 days of discharge.

Statistical Analyses

Categorical variables are reported as number (%) and continuous variables as median (interquartile range [IQR]). We divided the continuous operative time exposure into four quartiles to assess primary and secondary outcomes by increasing quantiles of operative time. Patient outcomes were also compared between approaches (open vs. video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery [VATS] vs. robotic) and by surgeon experience level. Comparisons between groups were made using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

Analyses for the primary outcomes (i.e., any complication and major postoperative complication) were conducted using mixed-effects models with logit link and surgeon-level random effects to account for correlation among cases by the same surgeon. Analyses for LOS were conducted using linear mixed-effects models with surgeon-level random effects. As LOS was log-transformed in this set of analyses, the coefficient (“beta”) represents fold increase in LOS for every hour increase in operative time. The relationship between the number of lymph node stations sampled and operative time was evaluated using Spearman’s correlation coefficient and was quantified using linear regression.

All multivariable models were constructed on the basis of a backward selection approach starting with factors with p<0.1 on univariable analyses. Operative time and operative approach were always forced into the multivariable models regardless of statistical significance, to obtain adjusted odds ratios (ORs) or beta coefficients with 95% CIs. All regression analyses used operative time as a continuous variable. We assessed the linearity assumption of operative time using restricted cubic splines and confirmed no violation.

Mediation analysis was performed in a three-step process. We included all traditional modifiable risk factors that surgeons consider during the preoperative evaluation phase, including comorbidities, preoperative lung function tests, BMI, smoking history, extent of lymph node sampling or dissection, and operative approach. First, we assessed the relationship between the target variable and the outcome of interest using univariable regression (step 1, see above for model specifications). Second, we assessed the relationship between the target variable and operative time using univariable linear mixed-effects models (step 2). Third, we constructed a multivariable model including the target variable, operative time, and the outcome of interest (step 3). Only variables that were significant in both step 1 and step 2 were evaluated in step 3. Degree of mediation (e.g., partial vs. full) was assessed by comparing the ORs of target variables in step 1 and step 3.

Analyses were performed using R version 4.0.2 (Vienna, Austria) and JMP Pro 14.0.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All statistical tests were two-sided, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Of 9566 patients identified, 1651 met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1 and Table 1). Median age was 68 years (IQR, 61–74), and 63% were women. Median BMI was 27 kg/m2 (IQR, 23.7–30.8). Most patients were White (83%) and former smokers (64%). Fifty-eight percent had cardiovascular comorbidities, and 3% had a history of contralateral lung cancer. Median preoperative FEV1 and DLCO were 94% and 84%, respectively. Median primary tumor size on computed tomographic imaging was 2 cm (IQR, 1.5–3.0). Preoperative tissue biopsy results were available for 68% of patients; the remainder underwent intraoperative frozen section. Most patients (77%) had stage I disease (including stage IA1, IA2 and IA3).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N=1651)

| Characteristic | Total |

|---|---|

| Age at surgery, years | 68 (61–74) |

| Female sex | 1045 (63) |

| Race | |

| Asian or Indian | 107 (6) |

| Black | 68 (4) |

| Black Hispanic | 5 (0.3) |

| White | 1370 (83) |

| White Hispanic | 36 (2) |

| Unknown | 65 (4) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27 (23.7–30.8) |

| Smoking history | |

| Never | 418 (25) |

| Former | 1060 (64) |

| Current | 173 (10) |

| Pack-years (N=1646) | 30 (15–50) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Pulmonary | 456 (28) |

| Cardiovascular | 952 (58) |

| Endocrine | 209 (13) |

| Renal | 28 (2) |

| Other | 97 (6) |

| Previous lung cancer | 45 (3) |

| Preoperative FEV1, % (N=1611) | 94 (82–105) |

| Preoperative DLCO, % (N=1565) | 84 (70–97) |

| Tumor size on computed tomography, cm (N=1627) | 2 (1.5–3.0) |

| Lesion standardized uptake value >2.5 units (N=1503) | 1036 (69) |

| Clinical stage | |

| IA1 | 111 (7) |

| IA2 | 674 (41) |

| IA3 | 482 (29) |

| IB | 265 (16) |

| IIA | 119 (7) |

| Tissue diagnosis | |

| Preoperative biopsy | 1121 (68) |

| Intraoperative frozen section | 530 (32) |

| Lobe, upper | 964 (58) |

| Laterality, right | 1047 (63) |

| Procedure type | |

| Open | 300 (18) |

| Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery | 913 (55) |

| Robotic | 438 (27) |

| Pathologic stage | |

| 0 | 7 (0.4) |

| IA1 | 131 (8) |

| IA2 | 515 (31) |

| IA3 | 321 (19) |

| IB | 288 (17) |

| IIA | 80 (5) |

| IIB | 194 (12) |

| IIIA | 89 (5) |

| IIIB | 18 (1) |

| IVA | 8 (0.5) |

| Pathologic diagnosis | |

| No cancer | 2 (0.1) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 1257 (76) |

| Squamous cell | 202 (12) |

| Small and large cell | 44 (3) |

| Non-small cell | 3 (0.2) |

| Carcinoid | 143 (9) |

Data are no. (%) or median (interquartile range). Tumors were staged in accordance with the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer guidelines. DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second.

The majority of patients underwent MIS: 913 patients (55%) underwent VATS, 438 (27%) underwent robotic lobectomy, and 300 (18%) underwent open procedures. Operative approach changed during the 9-year study period (p<0.0001; Figure S1): the proportion of MIS increased from 62% (52% VATS, 10% robotic) in 2010 to 91% (57% VATS, 34% robotic) in 2018.

Operative Time

Comparisons of operative time by approach and surgeon experience level are listed in Tables S1 and S2, respectively. Median operative time across all cases was 3.2 h (IQR, 2.7–3.8). Median operative time differed significantly by approach (p=0.0002): 3.0 h (IQR, 2.4–3.7) for open procedures, 3.3 h (IQR, 2.7–3.8) for VATS, and 3.3 h (IQR, 2.8–4.0) for robotic procedures. Operative time was also significantly shorter with increasing surgeon experience (p<0.0001; Table S2). Median nonoperative suite time was 0.7 h (IQR, 0.5–1.0), which also differed by approach and was longer in patients who underwent robotic procedures (p<0.0001). Total operative time was not significantly different by intraoperative frozen section status (p=0.3). Median number of lymph node stations sampled in all patients was 4 (IQR, 4–5); this also differed by approach (p<0.0001). Operative time and number of stations sampled were correlated (Spearman correlation coefficient=0.155; p<0.001): for every additional node sampled, operative time increased by 0.1 h (95% CI, 0.07–0.14; p<0.001).

Postoperative Outcomes

Postoperative outcomes and comparisons by operative time quartile, approach, and surgeon experience level are listed in Table 2, Table S1, and Table S2. In total, 488 patients (30%) experienced ≥1 in-hospital complication; of those, 352 (72%) experienced only 1 complication. Common complications included prolonged air leak, cardiac arrhythmia, pneumonia, and pneumonitis. Of all patients, only 77 (5%) had a major postoperative complication (grade ≥3). The most common major complications were hemorrhage, respiratory failure, prolonged air leak requiring intervention, and hyponatremia. Fifty patients (3%) required an unplanned procedure after their lobectomy; the most common reasons for intervention included need for tracheostomy, bronchoscopy, hemorrhage control, or hemothorax evacuation. Almost all patients (98%) were discharged home; only 5 (0.3%) died within 30 days of discharge. Data on readmissions were available for 737 patients (45%); across all years, 69 patients (9%) were readmitted. The most common reasons for readmission were infection, pleural effusion, and pneumothorax. Readmission rates decreased significantly during the study period (p<0.0001).

Table 2.

Operative outcomes by operative time quartile

| Variable | All Patients (N=1651) | Operative Time Quartile | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First (≤2.68 h) (N=418) |

Second (2.69–3.22 h) (N=412) |

Third (3.23–3.85 h) (N=410) |

Fourth (>3.85 h) (N=411) |

|||

| Nonoperative suite time, h | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | 0.8 (0.5–1.0) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 0.6 (0.5–1.0) | 0.6 (0.5–0.9) | 0.006 |

| Lymph node stations sampled | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (4–5) | 5 (3–6) | 5 (4–6) | <0.0001 |

| Any complication | 488 (30) | 102 (24) | 104 (25) | 132 (32) | 150 (37) | 0.0002 |

| Major complication, grade ≥3 | 77 (5) | 13 (3) | 15 (4) | 15 (4) | 34 (8) | 0.002 |

| Unplanned procedure | 50 (3) | 8 (2) | 9 (2) | 8 (2) | 25 (6) | 0.002 |

| Length of stay, days | 4 (3–5) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–6) | <0.0001 |

| Thirty-day readmission (N=737) | 69 (9) | 11 (7) | 12 (7) | 21 (12) | 25 (11) | 0.4 |

| Thirty-day mortality | 5 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.7) | 0.08 |

Data are no. (%) or median (interquartile range). P values were generated on the basis of comparison of the variable of interest across quartiles via Kruskal-Wallis or Fisher’s exact test. Complications were graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0. Unplanned procedures include return to the operating room, bronchoscopy, and interventional radiology. Mortality and readmission rates were measured within 30 days of discharge.

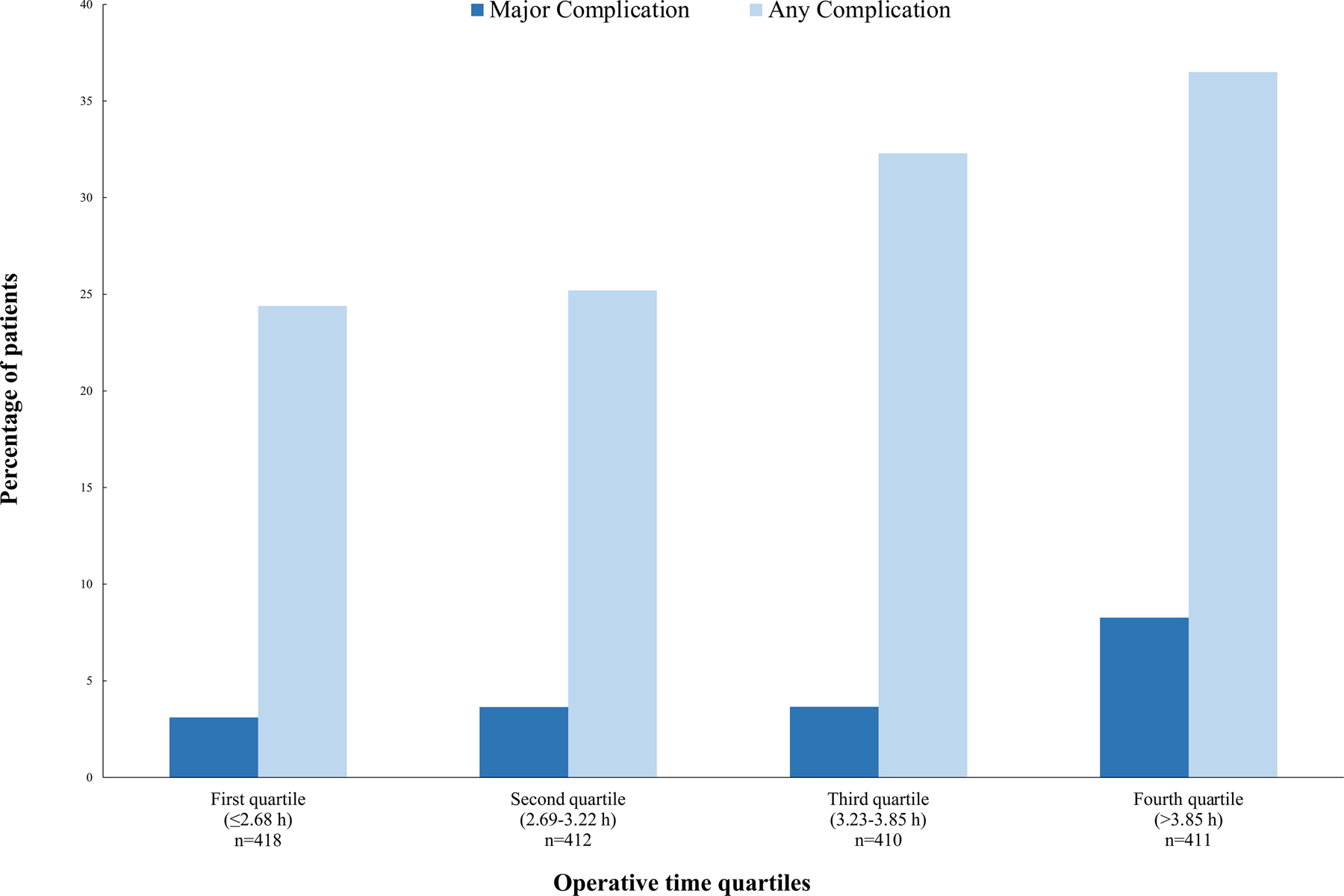

With the exception of LOS, which was shorter in patients who underwent MIS, primary and secondary outcomes did not differ by surgical approach (Table S1). We then stratified patients on the basis of operative time quartile (≤2.68 h, 2.69–3.22 h, 3.23–3.85 h, and >3.85 h) (Table 2). The proportions of patients with any complication (p=0.0002) and major complication (p=0.001) increased with longer operative time quartile (Figure 2). Similarly, the number of patients requiring an unplanned procedure (p=0.002) and overall LOS (p<0.0001) increased with longer operative time.

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients experiencing any (p=0.0002) or major (p=0.001) complication by quartile of operative time.

Rates of major complications (p=0.008) and unplanned procedures (p=0.002), as well as overall LOS (p<0.0001), differed significantly on the basis of surgeon experience level (Table S2).

Any Complication

Results from univariable and multivariable analyses are reported in Table S3 and Table 3. After adjustment for age (OR, 1.05 [95% CI, 1.03–1.06]; p<0.0001), BMI (OR, 0.97 [95% CI, 0.95–0.99]; p=0.006), baseline DLCO (OR, 0.99 [95% CI, 0.99–1.00]; p=0.009), number of lymph node stations sampled (OR, 1.10 [95% CI, 1.02–1.18]; p=0.01), and operative approach, longer operative time remained independently associated with higher odds of any complication (OR, 1.37 [95% CI, 1.20–1.57]; p<0.0001). For every 1 h increase in procedure time, the odds of experiencing any complication increased by 37%.

Table 3.

Multivariable regression analysis for any complication and major complication (grade ≥3)

| Variable | Any Complication | Major Complication | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Operative time, h | 1.37 (1.20–1.57) | <0.0001 | 1.41 (1.21–1.64) | <0.0001 |

| Age at surgery, years | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | <0.00001 | 1.05 (1.02–1.08) | 0.0002 |

| BMI | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.006 | — | — |

| Preoperative DLCO, % | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.009 | — | — |

| Procedure type | ||||

| Open | Reference | Reference | ||

| Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery | 0.75 (0.56–1.00) | 0.051 | 0.63 (0.30–1.33) | 0.2 |

| Robotic | 0.76 (0.47–1.22) | 0.3 | 0.55 (0.24–1.29) | 0.2 |

| Lymph node stations sampled | 1.10 (1.02–1.18) | 0.01 | 1.17 (1.01–1.36) | 0.041 |

| Surgeon experience level, years | ||||

| 0–5 | — | — | 2.20 (1.28–3.81) | 0.005 |

| 6–10 | — | — | 2.82 (1.60–4.96) | 0.0003 |

| 11–20 | — | — | 1.97 (1.12–3.45) | 0.018 |

| >20 | — | — | Reference | |

Mixed-effects models with logit link and surgeon-level random effects. Complications were graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0. BMI, body mass index; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; OR, odds ratio. Experience defined as years from completion of the cardiothoracic surgery fellowship.

Major Complication (Grade ≥3)

Results from univariable and multivariable analyses are reported in Table S3 and Table 3. After adjustment for age (OR, 1.05 [95% CI, 1.02–1.08]; p=0.0002), number of lymph node stations sampled (OR, 1.17 [95% CI, 1.01–1.36]; p=0.041), and surgeon experience level, longer operative time was independently associated with higher odds of a major postoperative complication (OR, 1.41 [95% CI, 1.21–1.64]; p<0.0001). For every 1 h increase in procedure time, the odds of experiencing a major complication increased by 41%.

LOS

Results from univariable regression analysis are listed in Table S4; multivariable regression results are listed in Table 4. Longer operative time was associated with longer LOS (beta, 1.09 [95% CI, 1.04–1.14]; p=0.001). Similarly, patients with preexisting pulmonary (beta, 1.14 [95% CI, 1.07–1.21]; p=0.0003) or cardiac (beta, 1.06 [95% CI 1.01–1.11]; p=0.016) comorbidities and those experiencing any (beta, 1.59 [95% CI, 1.47–1.73]; p<0.0001) or major (beta, 1.30 [95% CI, 1.02–1.66]; p=0.034) postoperative complication had longer LOS. Conversely, patients who underwent VATS (beta, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.72–0.89]; p=0.0002) or robotic (beta, 0.71 [95% CI, 0.64–0.79]; p<0.0001) lobectomy had shorter LOS than patients who underwent thoracotomy.

Table 4.

Multivariable regression analysis for hospital length of stay

| Variable | Beta (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Operative time, h | 1.09 (1.04–1.14) | 0.001 |

| Age at surgery, years | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.029 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Pulmonary | 1.14 (1.07–1.21) | 0.0003 |

| Cardiac | 1.06 (1.01–1.11) | 0.016 |

| Preoperative DLCO, % | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | <0.0001 |

| Laterality, right vs. left | 1.06 (1.01–1.12) | 0.029 |

| Procedure type | ||

| Open | Reference | |

| Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery | 0.80 (0.72–0.89) | 0.0002 |

| Robotic | 0.71 (0.64–0.79) | <0.0001 |

| Any in-hospital complication | 1.59 (1.47–1.73) | <0.0001 |

| Major in-hospital complication | 1.30 (1.02–1.66) | 0.034 |

Linear mixed-effects models with surgeon-level random effects. Length of stay was log-transformed. Complications were graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0. DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide.

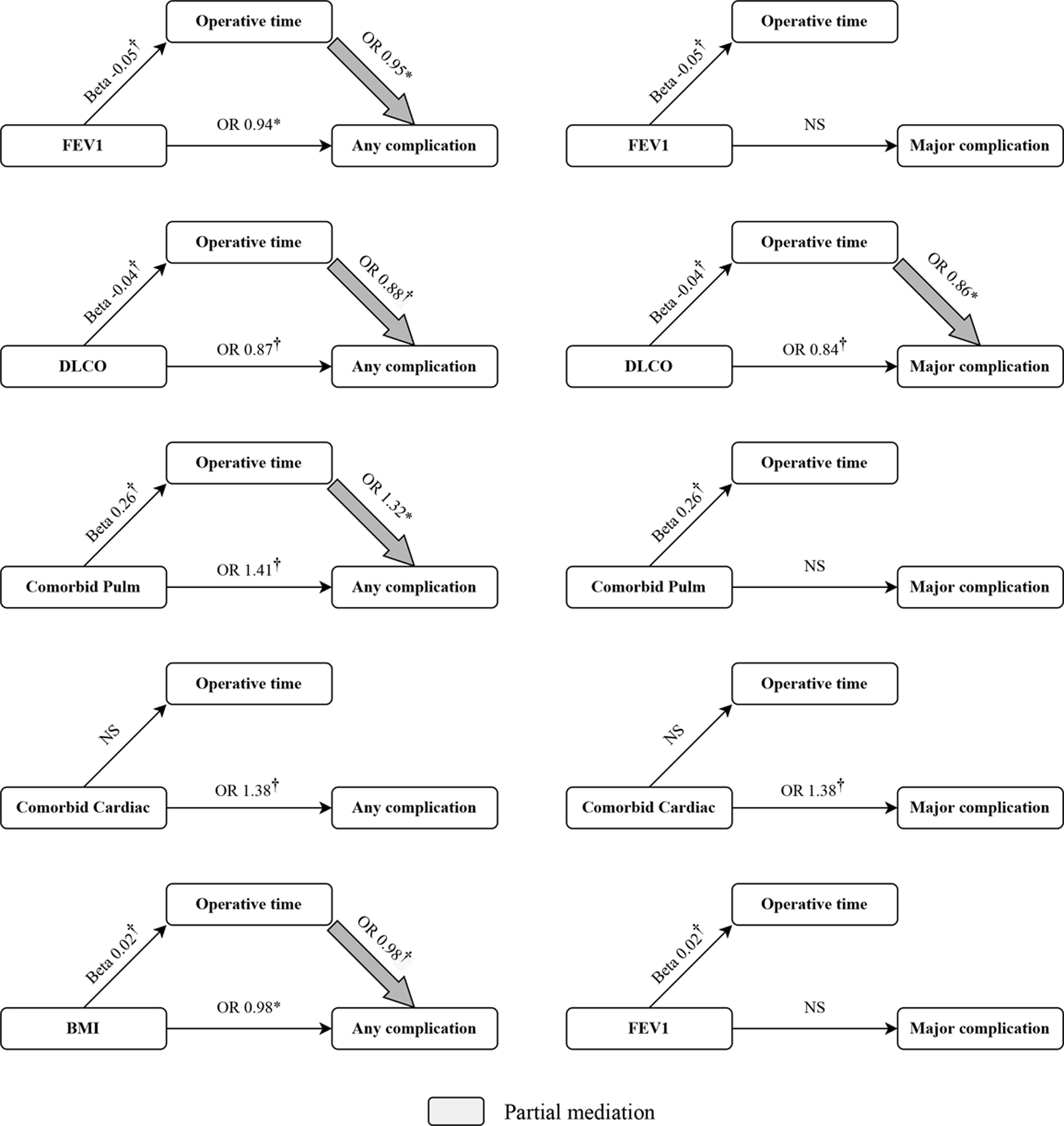

Mediation Analysis

Results from mediation analyses are reported in Figure 3. Among the risk factors examined, those the meeting criteria for inclusion (i.e., p<0.05 in both step 1 and step 2, see methods) were BMI, FEV1, DLCO, and pulmonary and cardiac comorbidities. We did not observe any instances of full mediation. We observed partial mediation of operative time between pulmonary comorbidities and any complication, FEV1 and any complication, DLCO and both any and major complication, and BMI and any complication.

Figure 3.

Mediation analysis. Larger arrow reports odds ratio for effect of target variable on outcome (i.e., any or major complication) mediated by operative duration. Coefficients reported above arrows are odds ratios from logistic mixed-effects models and beta from linear mixed-effects models. *p<0.05; †p<0.01; NS, not significant. Lack of arrow indicates no mediation.

Discussion

During the preoperative evaluation, surgeons focus on modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors.11 Potentially modifiable risk factors include smoking status, BMI, management of preexisting comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension), anesthetic plan, and surgical approach (open vs. MIS).6,7,11 Nonmodifiable risk factors include age, sex, and some components of procedure type (elective vs. emergent, reoperation).11 Traditionally, operative time has been considered a nonmodifiable risk factor for postoperative complications. Longer operative time has been associated with a higher likelihood of postoperative morbidity in general surgery.11–14 With regard to lung resections, Brunelli and colleagues found that longer operative time was associated with higher odds of death.2 In their cohort, patients who underwent VATS lobectomy lasting >150 min were 4-fold more likely to die by 90 days.2 Similarly, data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database shows that longer operative time is associated with a higher likelihood of postoperative reintubation and renal insufficiency in patients undergoing lung resection.4 Moreover, Stéphan et al. found that operative time >80 min was an independent risk factor for any type of postoperative complication among patients undergoing lung resection.5 These studies, however, relied on heterogeneous groups of patients with different disease stages undergoing different types of resection.2,4,5 More recently, Dexter and colleagues focused on patients with limited disease who underwent anatomic lobar resection and showed that operative time was strongly associated with postoperative outcomes.15 The authors, however, did not differentiate between VATS and robotic lobectomies, analyzed patients who underwent intraoperative conversion from MIS to thoracotomy within the thoracotomy group, and relied on different versions of a large national data set, which may have resulted in inconsistencies in data coding.

In the present study, we reviewed a large number of patients who underwent successful R0 standard lobectomy for resection of a primary lung cancer at a single center. By the use of strict exclusion criteria, we sought to identify a more homogenous cohort of patients. Of the 1651 patients included, only 5% experienced major morbidity postoperatively, and only 0.3% died within 30 days of discharge. These rates are lower than those reported in the literature. Interestingly, the 30-day readmission rate in our study was 9%; however, we examined more-recent data, collected from 2018 to 2021, and found that <4% of patients treated at our center within that time frame required readmission after lobectomy.

Operative time was associated with the odds of both any complication and major complication. Longer operative time was also associated with both a higher prevalence of unplanned procedures, including return to the operating room, and longer hospitalizations.

We also assessed the potential that operative time acted as a mediator in the relationship between modifiable risk factors (e.g., age, comorbidities, smoking status, FEV1, DLCO, and BMI) and our primary outcomes. Although there was no evidence of full mediation, we did detect partial mediation of operative time on the relationship between several of the modifiable factors examined and our outcomes of interest (detailed in Figure 3). This suggests that operative time is not only independently associated with but also mediates the effects of other risk factors on postoperative outcomes.

Determinants of operative time are multifactorial, ranging from patient- and disease-specific factors (age, surgical history, anatomy, stage) to center- or surgeon-specific factors (practice type, expertise of the surgeon, trainee participation, use of MIS, staffing). Intraoperative delays can be caused by staff shortages, equipment issues, poor communication, degree of trainee involvement, and trainee and attending proficiency.16–18 Attending surgeons may engage residents and fellows in the operating room as part of their academic mission; whether this results in prolongation of the surgical case is controversial, with studies showing both shorter19 and longer20 operative times for VATS when trainees are involved. An additional factor that could influence operative time is practice type. One may expect operative time to be shorter in the private practice setting; yet, to our knowledge, this assumption is not currently supported by available data. Moreover, Licker and colleagues found that operative time remained an independent predictor of complications after thoracic surgery even in private practice.21

During the last decade, pulmonary resections have been increasingly performed via MIS (up to 82% at our institution). In other settings, these procedures are still commonly performed through thoracotomy, which has been shown to have a shorter operative time, albeit with worse outcomes.21–24 In our study, patients who underwent VATS had shorter LOS after surgery; this finding is not surprising and replicates prior observations from our group and others.25–27 Interestingly, we found that patients in the MIS group had longer nonoperative suite times, which may be secondary to the need for additional setup and equipment. Nonoperative suite time was not associated with postoperative complications.

Several other factors were associated with postoperative morbidity, including age, BMI, preoperative lung function, surgeon experience level, and extent of lymph node sampling or dissection; perhaps not surprisingly, more-experienced surgeons operated faster, and their patients had lower odds of experiencing complications. Age is a known nonmodifiable risk factor for any procedure.11 Similarly, preoperative function tests have been consistently used for risk assessment.28–30 In our cohort, the effects of both FEV1 and DLCO on morbidity were partially mediated by operative time. Interestingly, we observed an inverse correlation between BMI and odds of both any and major complication. Other studies have reported lower perioperative morbidity and mortality in obese patients—a phenomenon known as the “obesity paradox.”31–33

In our study, extent of node sampling or dissection was associated with higher odds of both any and major complication. One might expect that more-extensive lymphadenectomy in and of itself is associated with higher rates of intraoperative and postoperative complication (bleeding, chylothorax, etc.); however, that expectation is yet unfounded.34,35 Our analyses and previous work highlight a strong correlation between number of lymph node stations sampled and total operative time.34,35 However, both lymphadenectomy and, in the appropriate setting, lymph node sampling are crucial components of any standard lobectomy, and oncologic completeness should not be compromised to reduce operative time.

Our results indicate that operative time should be factored into the surgeon’s preoperative and intraoperative decision-making process. Whereas some of the previously cited context-specific factors are nonmodifiable, others (trainee involvement, correct case-trainee matching, operating room scheduling to maximize staff availability) can be modulated and should influence surgical planning. It may be argued that, in certain situations (patients with incomplete fissures, fibrothorax, granulomatous nodal disease), operative time is a consequence of case complexity and cannot be modified; even in those cases, however, the surgeon can modify operative approach with time in mind, or decide to convert from MIS to open early during the operation.

This study has several limitations. This was a single-center retrospective review. Although we included a large number of patients, all factors that influence operative time may not be easily captured from the electronic health record. Furthermore, as factors that influence operative time are environment specific, our experience may not be generalizable to other institutions. However, reviewing patients from a single institution allowed for consistency in practice patterns and data coding. We calculated operative time from skin incision to closure and evaluated nonoperative suite time separately. Time is recorded by the circulating nurse and may not always be recorded accurately. Moreover, 530 cases (32%) included frozen section, which may have delayed the case; yet, we found no difference in total operative time by frozen section status, and the presence of a preoperative tissue diagnosis—a proxy for the need for intraoperative frozen section—was not a predictor of complications. This is most likely because surgeons carry on with portions of the procedure while waiting for frozen section results. To limit the effect of the learning curve for MIS, patients admitted before January 2010 were excluded; however, cases included in this study were performed by a diverse group of surgeons, including junior faculty and others at the beginning on their robotics training curve. Our analyses address potential surgeon effect by incorporating a variable to capture surgeon experience level and including a surgeon-level random effect to account for correlation among cases by the same surgeon. Whereas we did evaluate total nonoperative suite time, we did not measure the duration of the preintubation, bronchoscopy, and postextubation phases and their associations with postoperative morbidity. Having specific information on the timing of all steps of the procedure may help identify additional areas for improvement. Finally, our overall cohort had very few deaths, which precluded analysis of predictors of postoperative mortality.

In conclusion, in this select group of patients with localized disease, longer operations were associated with higher odds of postoperative complications, more unplanned procedures, and longer hospitalizations. Furthermore, operative time also mediated the effects of other modifiable risk factors on postoperative outcomes. Moving forward, operative time should be factored into the perioperative decision-making process, and attempts should be made to decrease operative time to reduce postoperative morbidity. Future work should carefully analyze processes influencing operative time in different clinical environments to better delineate preoperative and intraoperative factors that can be targeted to decrease morbidity and improve outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Increase in the proportion of procedures with a minimally invasive approach during the study period. Fisher’s exact test p<0.0001. VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the health care professionals who participated in the care of the patients included in this study. We also recognize the clinical research assistants who maintain the institutional research database.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

This work was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Meeting Presentation: This study was presented, in abstract form, at the American Association for Thoracic Surgery Annual Meeting, Boston, Massachusetts, May 15–17, 2022.

List of Supplemental Digital Content

Supplemental Tables.docx

S1.tif

References

- 1.Agostini PJ, Lugg ST, Adams K, et al. Risk factors and short-term outcomes of postoperative pulmonary complications after VATS lobectomy. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;13:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunelli A, Dinesh P, Woodcock-Shaw J, et al. Ninety-day mortality after video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy: incidence and risk factors. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104:1020–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Infante MV, Benato C, Silva R, et al. What counts more: the patient, the surgical technique, or the hospital? A multivariable analysis of factors affecting perioperative complications of pulmonary lobectomy by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery from a large nationwide registry. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;56:1097–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jean RA, DeLuzio MR, Kraev AI, et al. Analyzing risk factors for morbidity and mortality after lung resection for lung cancer using the NSQIP database. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222:992–1000.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stéphan F, Boucheseiche S, Hollande J, et al. Pulmonary complications following lung resection. Chest. 2000;118:1263–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gagné S, McIsaac DI. Modifiable risk factors for patients undergoing lung cancer surgery and their optimization: a review. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:S3761–3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agostini P, Cieslik H, Rathinam S, et al. Postoperative pulmonary complications following thoracic surgery: are there any modifiable risk factors? Thorax. 2010;65:815–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas DC, Arnold BN, Hoag JR, et al. Timing and risk factors associated with venous thromboembolism after lung cancer resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105:1469–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nan DN, Fernández-Ayala M, Fariñas-Álvarez C, et al. Nosocomial infection after lung surgery. Chest. 2005;128:2647–2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2017:715–725. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miskovic A, Lumb AB. Postoperative pulmonary complications. Br J Anaesth 2017;118:317–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazo V, de Abreu MG, Hoeft A. Prospective external validation of a predictive score for postoperative pulmonary complications. Perioper Med. 2014;121:219–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang CK, Teng A, Lee DY, et al. Pulmonary complications after major abdominal surgery: national surgical quality improvement program analysis. J Surg Res. 2015;198:441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Procter LD, Davenport DL, Bernard AC, et al. General surgical operative duration is associated with increased risk-adjusted infectious complication rates and length of hospital stay. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dexter E, Attwood K, Demmy T, et al. Does operative duration of lobectomy for early lung cancer increase perioperative morbidity? Ann Thorac Surg. 2022. [Online ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babineau TJ. The “cost” of operative training for surgical residents. Arch Surg. 2004;139:366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kauvar DS, Braswell A, Brown BD, et al. Influence of resident and attending surgeon seniority on operative performance in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Surg Res. 2006;132:159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkiemeyer M, Pappas TN, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. Does resident post graduate year influence the outcomes of inguinal hernia repair? Ann Surg. 2005;241:879–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenfeld ES, Napolitano MA, Sparks AD, et al. Impact of trainee involvement on video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy for cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;112:1855–1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wan IYP, Thung KH, Hsin MKY, et al. Video-assisted thoracic surgery major lung resection can be safely taught to trainees. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:416–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Licker M, Spiliopoulos A, Frey J-G, et al. Management and outcome of patients undergoing thoracic surgery in a regional chest medical centre. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2001;18:540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subramanian MP, Liu J, Chapman WC, et al. Utilization trends, outcomes, and cost in minimally invasive lobectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;108:1648–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajaram R, Mohanty S, Bentrem DJ, et al. Nationwide assessment of robotic lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:1092–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kent M, Wang T, Whyte R, et al. Open, video-assisted thoracic surgery, and robotic lobectomy: review of a national database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flores RM, Park BJ, Dycoco J, et al. Lobectomy by video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) versus thoracotomy for lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cattaneo SM, Park BJ, Wilton AS, et al. Use of video-assisted thoracic surgery for lobectomy in the elderly results in fewer complications. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim EKS, Batchelor TJP, Dunning J, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic versus open lobectomy in patients with early-stage lung cancer: One-year results from a randomized controlled trial (VIOLET). J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:8504. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Olak J, Ferguson MK. Diffusing capacity predicts operative mortality but not long-term survival after resection for lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:581–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferguson MK, Reeder LB, Mick R. Optimizing selection of patients for major lung resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;109:275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferguson MK, Vigneswaran WT. Diffusing capacity predicts morbidity after lung resection in patients without obstructive lung disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:1158–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valentijn TM, Galal W, Tjeertes EKM, Hoeks SE, Verhagen HJ, Stolker RJ. The obesity paradox in the surgical population. Surgeon. 2013;11:169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valentijn TM, Galal W, Hoeks SE, van Gestel YR, Verhagen HJ, Stolker RJ. Impact of obesity on postoperative and long-term outcomes in a general surgery population: a retrospective cohort study. World J Surg. 2013;37:2561–2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson AP, Parlow JL, Whitehead M, Xu J, Rohland S, Milne B. Body mass index, outcomes, and mortality following cardiac surgery in Ontario, Canada. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allen MS, Darling GE, Pechet TTV, et al. Morbidity and mortality of major pulmonary resections in patients with early-stage lung cancer: initial results of the randomized, prospective ACOSOG Z0030 trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:1013–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Izbicki JR, Thetter O, Habekost M, et al. Radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy in non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Surg. 2005;81:229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Increase in the proportion of procedures with a minimally invasive approach during the study period. Fisher’s exact test p<0.0001. VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.