Abstract

Introduction:

Social support can be a protective factor against the negative mental health outcomes experienced by some parents and caregivers of children with differences of sex development (DSD). However, established social support networks can be difficult to access due to caregiver hesitancy to share information with others about their child’s diagnosis. Healthcare providers in the field of DSD, and particularly behavioral health providers, are well positioned to help caregivers share information with the important people in their lives in order to access needed social support. This article summarizes the development of a clinical tool to help clinicians facilitate discussions regarding information sharing with caregivers of children with DSD.

Method:

Members of the psychosocial workgroup for the DSD - Translational Research Network completed a survey about their experiences facilitating information sharing discussions with caregivers of children with DSD and other health populations. The results of this survey were used to develop a clinical tool using ongoing iterative feedback from workgroup members, based on principles of user-centered design and quality improvement.

Results:

Workgroup members consider information sharing an important aspect of working with caregivers of children with DSD. Additional resources and tools were identified as potentially helpful to these discussions.

Discussion:

The DSD Sharing Health Information Powerfully – Team Version (SHIP-T) is a resource tool for DSD healthcare team members to utilize in hospital and ambulatory settings to help caregivers of children with DSD share information with their social support networks. The final SHIP-T is included in this article.

Keywords: Differences of sex development, intersex, parents, social support, clinical resource

Differences of sex development (DSD)1 represent a heterogeneous group of congenital conditions in which development of sex chromosomes, external genitalia, or internal sex organs is atypical (Lee et al., 2006). Some parents and caregivers of children with DSD experience negative mental health outcomes, including increased parenting stress, decreased coping, perceived stigma, isolation, and posttraumatic stress symptoms (Delozier et al., 2019; Duguid et al., 2007; Pasterski et al., 2014; Rolston et al., 2015; Wisniewski & Sandberg, 2015). Although social support is one of the most robust protective factors against perceived stigma and negative mental health outcomes generally (Kondrat et al., 2018), caregiver hesitancy or perceived inability to share information about their child’s DSD diagnosis with others can change the way caregivers typically access their support networks (Chivers et al., 2017; Duguid et al., 2007).

Information sharing comes in two forms: (1) sharing of information between providers, caregivers, and the patient, and (2) patients and caregivers sharing information with other important people in their lives (Sandberg et al., 2012). This paper focuses on the latter, with an emphasis on information sharing by parents and caregivers. Although there is considerable variability, most caregivers share information about their child’s diagnosis with their partner and their own parents, while fewer share this information with their other children, close friends, and other relatives (Sandberg et al., 2017).

Broadly, whether someone chooses to share information regarding a concealable identity depends on a variety of factors, such as the content of the information, how well the individual understands the information, confidence in their ability to effectively communicate the information, relationship quality, and anticipated response from the other person (Greene et al., 2012). In DSD specifically, caregivers choose to conceal information for similar reasons, including a desire to maintain a child’s future privacy, perceived stigma, and discomfort around or perceived lack of ability to accurately describe the condition and associated features (Chivers et al., 2017; Crissmnan et al., 2011). Efficacy in describing the information is complicated by DSD terminology, which is neither consistently used nor universally accepted (Lundberg et al., 2018; Miller et al., 2018). Unfortunately, in addition to preventing caregivers from fully accessing their support networks, the very act of maintaining this privacy can increase stress (Crissmnan et al., 2011).

Healthcare providers are well positioned to help caregivers share information with important people in their social networks. In particular, behavioral health providers (e.g., psychologists, social workers, psychiatric nurse practitioners) can support caregivers by improving caregiver understanding of diagnosis and confidence in their ability to communicate the information, exploring and helping regulate difficult emotions that arise in the context of important conversations, and identifying key people within social networks most likely to provide needed support (Ernst et al., 2016; Greene et al., 2012; Sandberg et al., 2012). The Disorders/Differences of Sex Development – Translational Research Network (DSD-TRN) is a United States-based collaborative network of clinicians and researchers invested in improving healthcare outcomes for persons with DSD. The DSD-TRN Psychosocial Workgroup (PSW) is a subgroup of the larger DSD-TRN that includes psychologists, social workers, researchers, and patient advocates interested in the psychosocial aspects of DSD. The PSW set as a priority the evaluation and facilitation of shared practices for helping parents and caregivers of children with DSD access their support networks through information sharing.

Purpose

The objectives of this article are to (1) describe the results of a clinician needs assessment regarding information sharing among PSW members, and (2) summarize the subsequent development of a tool to help clinicians facilitate discussions regarding information sharing with caregivers of children with DSD. Using elements of User-Centered Design (Johnson et al., 2005) and Quality Improvement (Taylor et al., 2014), we implemented an iterative process of assessing clinician needs and subsequent feedback regarding this clinical resource tool.

Method and Results

PSW members were asked to complete a needs assessment survey examining clinical experiences with patients and families discussing the topic of sharing information about a DSD condition with family and close others. Results were reviewed with PSW members to clarify the needs of behavioral health providers to facilitate the creation of a clinician tool. The clinician tool was created and iteratively reviewed with the PSW for feedback and refinement.

Needs Assessment Survey and Results

The authors (De-identified) created a needs assessment to inform the development of a tool for PSW providers to use when discussing the importance of sharing information with caregivers. When completing the needs assessment survey, providers were asked to think of their clinical practice with patients with a DSD and their caregivers. See Table 1 for quantitative survey questions and response rates and Table 2 for qualitative survey questions and response themes. Nineteen members of the PSW completed the survey (70% completion rate). Quantitative questions asked members how important they think information sharing conversations are (5-point scale from “Not at all important” to Extremely important”) and how comfortable they are facilitating these conversations (6-point scale from “extremely uncomfortable” to “extremely comfortable”). Members thought it was extremely to very important to have conversations with caregivers regarding sharing information about their child’s condition with family/close others (average of 4.4 out of 5), and they were moderately to slightly comfortable facilitating these discussions (average of 4.4 out of 6).

Table 1.

Quantitative Results of Needs Assessment Survey (N = 19)

| Quantitative Questions | Response Options | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| How comfortable are you in facilitating discussions about “information sharing” with parents of a newborn/young child with a new DSD diagnosis? | Extremely comfortable | 4 | 21.1 |

| Moderately comfortable | 8 | 42.1 | |

| Slightly comfortable | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable | 3 | 15.8 | |

| Slightly uncomfortable | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Extremely uncomfortable | 1 | 5.3 | |

| No answer | 1 | 5.3 | |

|

| |||

| How important do you think it is for providers to facilitate discussions about “information sharing” with parents of a newborn/young child with a new DSD diagnosis? | Extremely important | 10 | 52.6 |

| Very important | 4 | 21.1 | |

| Moderately important | 3 | 15.8 | |

| Slightly important | 0 | 0 | |

| Not at all important | 0 | 0 | |

| No answer | 2 | 10.5 | |

Table 2.

Qualitative Results of Needs Assessment Survey (N = 19)

| Qualitative Questions | Response Themes | Quote Examples | Count |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| When working with parents of a newborn/young child with a new DSD diagnosis, how often is “information sharing” (i.e., sharing information with close others to allow for social support) a specific target of therapy? | Always | Every time; Universally; Always | 5 |

| Often | Very common; Often | 8 | |

| Sometimes | Sometimes; Moderate amount | 3 | |

|

| |||

| What would help you feel even more comfortable in facilitating discussions? | More experience/education | More experience (I’m fairly new to DSD population); More education | 6 |

| Having a written resource | Written material to provide family; Scripted language | 6 | |

| More Research | List of citations/research on social support in DSD | 2 | |

| Peer support for parents | Peer parent groups or mentors that can share personal experiences related to information sharing | 2 | |

| More time | More time with [the] family | 1 | |

|

| |||

| What are barriers parents experience related to sharing information with close others (family/friends)? | Perceived stigma | Shame around sex/gender issues | 14 |

| Lacking information/understanding | Unclear diagnosis; Lack of knowledge | 7 | |

| Privacy concerns | Protecting their child’s privacy | 7 | |

| Culture | Cultural and ethnic issues | 2 | |

| Denial/avoidance | Denial of diagnosis; Avoidance | 2 | |

| Interpersonal history | Strained past relationships | 1 | |

|

| |||

| What are barrier providers experience related to facilitating parents sharing information with close others (family/friends)? | Education/training | Lack of confidence on what to say; lack of uniform understanding about the harm that can derive from secrecy | 5 |

| Family factors | Hard to make specific recommendations without understanding more about family and community | 5 | |

| Parents do not want to share | Parents being adamant that no one will know | 4 | |

| Limited time | Inadequate time; Timing | 3 | |

| Ongoing diagnostic process | Fact that in many cases team is still gathering information, may be talking with parents about sharing incomplete information or information that may change over time | 3 | |

| Privacy/legal concerns | Fear of legal violations; Protecting the child’s privacy | 2 | |

One open-ended question asked members how often information sharing is a specific topic discussed with new patients, and most members indicated that it is often or always the case. An inductive, data-driven approach was taken to analyze the answers to remaining open-ended questions. A total of 13, 18, and 17 people responded to questions about what might increase provider comfort with information sharing, patient-related barriers, and provider-related barriers, respectively. Item responses were categorized into themes by one author (de-identified) and verified by a second author (de-identified). Themes were later reviewed by all authors for clarity and consistency.

The most common themes for increasing provider comfort level in discussing information sharing included more experience/education and having a written resource, followed by more research, peer support for caregivers, and more time in clinic. Regarding caregivers sharing information, the most commonly identified barrier was perceived stigma, followed by a limited understanding about how to share with others and concerns about the child’s privacy. The most commonly identified provider barriers to facilitating these discussions were a lack of education/training, caregivers not wanting to share, and other family factors.

Creation of the SHIP-T

The results of the needs assessment survey suggested that providers who are working on DSD teams may benefit from resource tools to help facilitate discussions about social support and information sharing. Two of the authors (De-identified) presented the results of the survey and a proposal to create specific resource tools to the PSW and received positive feedback. A team (De-identified) was formed to create information sharing tools. There are several aspects of information sharing, and we elected to first focus on caregivers sharing information with their own support networks. This first clinical tool was subsequently named the Sharing Health Information Powerfully – Team Version (SHIP-T). Based on principles of user-centered design and quality improvement, we implemented an iterative process of drafting, soliciting feedback, and revising the SHIP-T to best serve the expressed needs of the group.

Our goals for the tool were to (1) increase frequency of health care provider information-sharing conversations with caregivers of children with a DSD and (2) improve the quality of those conversations by incorporating best practice components of disclosure interventions. Therefore, we designed the tool keeping in mind the literatures on both health care provider behavior change (Gupta et al., 2021) and models for health information disclosure (Greene et al., 2012; Rochat et al., 2013; Schulte et al., 2021). Both areas of literature highlight the importance of providing tailored, contextually relevant information as well as behavioral rehearsal to increase self-efficacy. In addition, research shows that closeness of the recipient of the disclosure impacts willingness to share information (Greene et al., 2012).

Thus, the first version of the tool included the following elements: (1) an evidence-based rationale for facilitating information sharing conversations with caregivers along with references (to increase health care providers’ confidence in the merits of information sharing as well as having resources to share with caregivers), (2) common clinical considerations and potential behavioral communication interventions, and (3) a series of prompts to help caregivers explore their social support networks for the purpose of identifying potential recipients of shared information. Motivational Interviewing (MI) was highlighted on the tool as a framework for discussions with caregivers because MI has a strong evidence-base for promoting behavior change and dovetails with a tailored, person-centered intervention approach (Miller & Rollnick, 1991). PSW members reviewed this draft of the SHIP-T and provided feedback on the format and content.

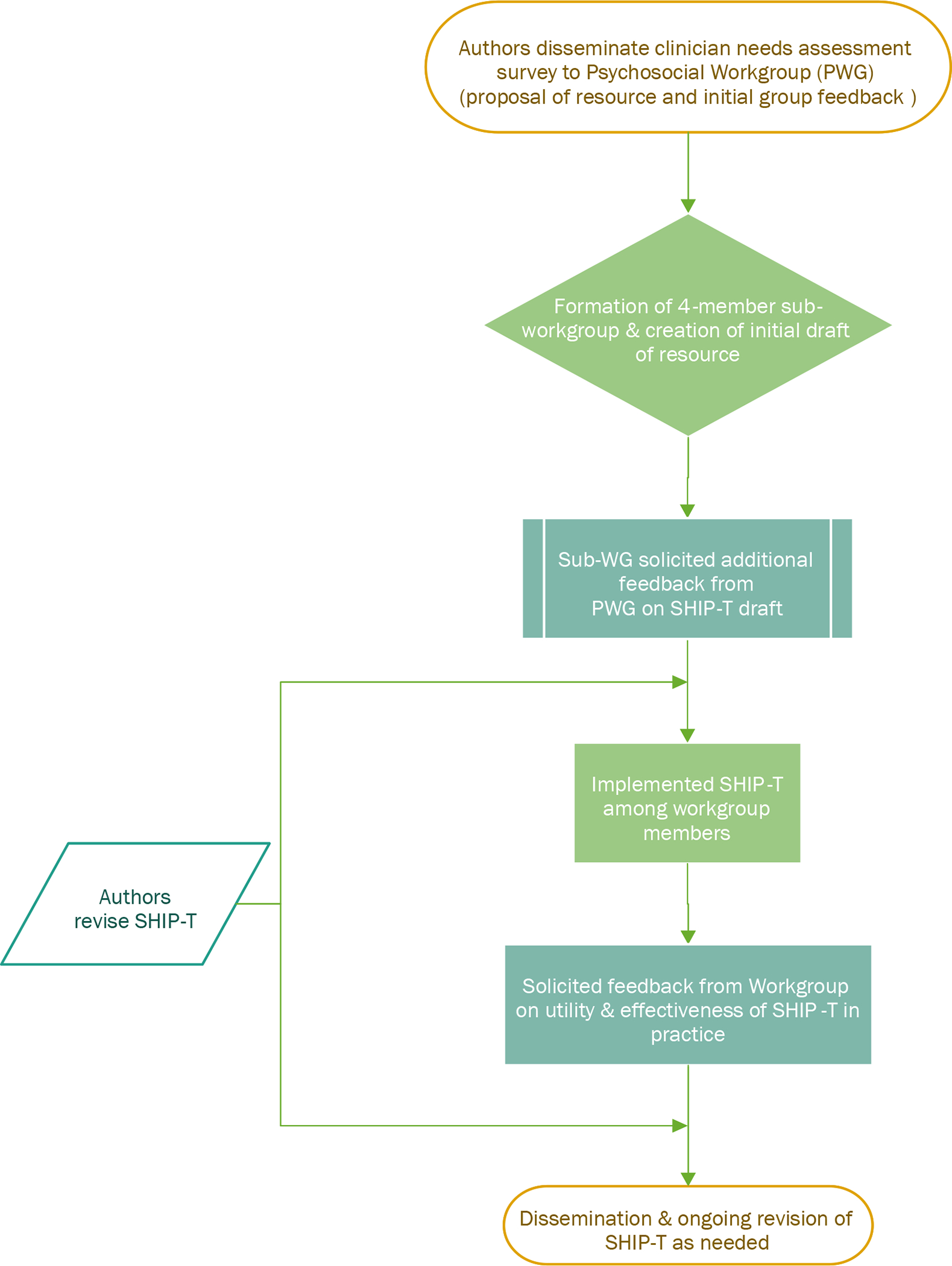

We revised the tool, then asked PSW clinicians to use the tool in their DSD clinics and subsequently surveyed them on the utility and effectiveness of the tool in practice. Three workgroup members provided written feedback on the survey, one individual with a DSD provided additional written feedback, and one additional clinician provided oral feedback. The final version of the SHIP-T can be found in the accompanying online supplemental materials. The feedback and survey results regarding the SHIP-T will also be used to inform a companion handout that can be given to caregivers when having these discussions. See Figure 1 for a diagram of this process of tool design and iterative feedback.

Figure 1.

Iterative process for the development of the SHIP-T

Discussion

The results of a needs assessment among members of the DSD-TRN PSW suggest that providers find it very important to help caregivers share information with others, but barriers exist to optimizing those discussions. The aims of this paper were to present the findings of the needs assessment, along with the subsequent development of the SHIP-T: a clinician tool designed to facilitate information sharing. Needs assessments have been used by multi-disciplinary, pediatric teams to improve communication between providers, patients, and families (e.g., Schneider et al., 2016) and inform clinician resource development (e.g., Painter et al., 2018). The results of the current needs assessment similarly suggested that additional education and resources might help clinicians facilitate discussions about information sharing with caregivers.

The SHIP-T clinician tool was developed in response to the identified needs of behavioral health providers working on DSD teams. The tool highlights what is known from the literature on information-sharing more broadly, while also highlighting important distinctions specific to DSD, such as concerns related to stigma (Greene et al., 2012; Kondrat et al., 2018). The importance of cultural norms related to self-disclosure is referenced, as well as the fact that cultural norms regarding gender, sex and other DSD concerns such as infertility are important to consider (Ediati et al., 2016; Weidler & Peterson, 2019; Yuki & Schug, 2012). The tool capitalizes on evidence-based approaches such as Motivational Interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 1991) to promote caregiver accessing social support, and behavioral rehearsal strategies to increase caregiver confidence in information-sharing (Rochat et al., 2013; Schulte et al., 2021). The tool also promotes use of the standardized assessment protocol used within the DSD-TRN (Sandberg et al., 2017) to facilitate the discussion of information-sharing with caregivers. An example of a potential intervention step includes questions for exploring a caregiver’s uncomfortable feelings about their child’s diagnosis. To explore social support networks, prompts ask “can you think of a person who…” with several potential options such as “confides in you” and “is very involved with your family.” Once a person is identified, follow-up questions include “What are the potential benefits/costs of telling this person?” and “What do you predict their reaction to be?”

We believe this tool addresses several identified barriers from the needs assessment, such as caregivers lacking understanding of how to share with others and providers needing more education and training on how to facilitate discussions. When used clinically, this tool may further address barriers such as caregiver perceived stigma and concerns about child privacy.

Limitations and Future Directions

Some barriers identified during the initial needs assessment may not be addressed by the SHIP-T. For example, having a limited amount of time in clinic to have these discussions with families and the ongoing diagnostic uncertainty that often accompanies some DSD diagnoses.

This article presents the creation of the SHIP-T based on principles of user-centered design and quality improvement, including clinician self-reported practices, clinical needs, and perceptions of the tool. However, there is no empirical data to date on the utility of the SHIP-T, as measured by objective outcomes such as caregiver-reported effectiveness, social support, and mental health. One future direction is to empirically study the utility of the SHIP-T as a clinical tool. Caregivers were not involved in this initial development of the SHIP-T. Caregiver perspectives and feedback may be useful in the future to further refine this tool, especially in our next steps of converting the tool into a supplemental caregiver worksheet.

We believe the SHIP-T can help behavioral health providers and other clinicians facilitate discussions with caregivers regarding sharing information about their child’s diagnosis with their own support network. This is only one aspect of information sharing that is relevant to the care of children with DSD and their families. Another future direction for the DSD-TRN information sharing sub-workgroup include (1) creating a companion handout to the SHIP-T that can be given to caregivers, and (2) creating parallel tools related to (a) caregivers sharing information with their children, and (b) children sharing information with their own support networks. Regarding caregivers sharing information with their child, one study found that 90% of the caregivers surveyed reported never receiving guidance in this area, and 43% reported that they desired this type of support, highlighting the need for ongoing resource development (Blankstein et al., 2022).

Conclusion

The SHIP-T is a clinical tool for DSD healthcare team members to utilize in hospital and ambulatory settings to help caregivers of children with DSD share information with their social support networks. By making the SHIP-T freely available, we hope behavioral health providers and other clinicians working with DSD will feel empowered to facilitate these important discussions. A user-centered design approach can be used to create clinical tools that best serve the needs of the clinicians who use them.

Supplementary Material

Public Significance Statement:

Medical professionals, especially behavioral health providers, working on teams providing care for children with differences of sex development can help parents to engage their social networks by sharing relevant health information with others. The SHIP-T was created as a clinician tool to facilitate these discussions with parents.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank members of the DSD-TRN Psychosocial Workgroup for their support in creating this clinical tool, including: Cindy Buchanan, PhD (Children’s Hospital Colorado); Jodie Johnson, MS, LGC (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center); Maureen Monaghan, PhD (Children’s National); Zoe Lapham, David Sandberg, PhD, and Behzad Sorouri Khorashad (University of Michigan); Tara Schafer-Kalkhoff, MA (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center); Carmel Foley, MD, Claire Pawlak, Rashida Talib, MBBS, MPH (Northwell Health); Diane Chen, PhD, Josie Hirsch, BA, Danielle Lee, LCSW, Jaclyn Papadakis, PhD, Ilina Rosoklija, MPH, Briahna Yuodsnukis, PhD (Lurie Children’s Hospital); Jon Poquiz, PhD (Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital), Angelica Eddington, PhD (National Children’s Hospital), Linda Ramsdell, MS, Elizabeth McCauley, PhD, and Margarett Shnorhavorian, MD, MPH (Seattle Children’s Hospital); Miriam Boyd Muscarella, Brooke Rosen, MD, and Richard Shaw, MD (Stanford); Meghan Marsac, PhD (University of Kentucky); Nicolas Meade and Christy Olezeski, PhD (Yale University); Synthia Puffenberger, PhD (Phoenix Children’s Hospital)

This work was conducted in affiliation with the Disorders/Differences of Sex Development – Translational Research Network (DSD-TRN) and was funded in part by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD093450). We would like to thank all providers and individuals with a DSD who helped in the development of the information sharing tool. We have no known conflict of interests to disclose.

Footnotes

The term disorder of sex development was suggested by the Consensus Statement on Management of Intersex Disorders (Lee et al., 2006). However, the word “disorder” is viewed by many as stigmatizing and other terms are preferred by some (e.g., Intersex). We chose to refer to these conditions as differences of sex development to recognize the controversy over labels and to promote person first language.

References

- Blankstein U, McGrath M, Randhawa H, & Braga LH (2022). A survey of parental perceptions and attitudes related to disclosure in hypospadias repair. J Pediatr Urol. 10.1016/j.jpurol.2022.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivers C, Burns J, & Deiros Collado M (2017). Disorders of sex development: Mothers’ experiences of support. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry, 22(4), 675–690. 10.1177/1359104517719114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crissmnan HP, Warner L, Gardner M, Carr M, Schast A, Quittner AL, Kogan B, & Sandberg DE (2011). Children with disorders of sex development: A qualitative study of early parental experience. International Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delozier AM, Gamwell KL, Sharkey C, Bakula DM, Perez MN, Wolfe-Christensen C, Austin P, Baskin L, Bernabe KJ, Chan YM, Cheng EY, Diamond DA, Ellens REH, Fried A, Galan D, Greenfield S, Kolon T, Kropp B, Lakshmanan Y, . . . Mullins LL (2019). Uncertainty and Posttraumatic Stress: Differences Between Mothers and Fathers of Infants with Disorders of Sex Development. Arch Sex Behav, 48(5), 1617–1624. 10.1007/s10508-018-1357-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duguid A, Morrison S, Robertson A, Chalmers J, Youngson G, Ahmed SF, & Scottish Genital Anomaly N (2007). The psychological impact of genital anomalies on the parents of affected children. Acta Paediatr, 96(3), 348–352. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.00112.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ediati A, Maharani N, Utari A (2016). Sociocultural aspects of disorders of sex development. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today, 108(4), 380–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst ME, Sandberg DE, Keegan C, Quint EH, Lossie AC, & Yashar BM (2016). The Lived Experience of MRKH: Sharing Health Information with Peers. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol, 29(2), 154–158. 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene K, Magsamen-Conrad K, Venetis MK, Checton MG, Bagdasarov Z, & Banerjee SC (2012). Assessing health diagnosis disclosure decisions in relationships: testing the disclosure decision-making model. Health Commun, 27(4), 356–368. 10.1080/10410236.2011.586988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta B, Li D, Dong P, & Acri MC (2021). From intention to action: A systematic literature review of provider behaviour change-focused interventions in physical health and behavioural health settings. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 27(6), 1429–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CM, Johnson TR, & Zhang J (2005). A user-centered framework for redesigning health care interfaces. J Biomed Inform, 38(1), 75–87. 10.1016/j.jbi.2004.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondrat DC, Sullivan WP, Wilkins B, Barrett BJ, & Beerbower E (2018). The mediating effect of social support on the relationship between the impact of experienced stigma and mental health. Stigma and Health, 3(4), 305–314. 10.1037/sah0000103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PA, Houk CP, Ahmed SF, Hughes IA, International Consensus Conference on Intersex organized by the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine, S., & the European Society for Paediatric, E. (2006). Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. International Consensus Conference on Intersex. Pediatrics, 118(2), e488–500. 10.1542/peds.2006-0738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg T, Hegarty P, & Roen K (2018). Making sense of ‘Intersex’ and ‘DSD’: how laypeople understand and use terminology. Psychology & Sexuality, 9(2), 161–173. 10.1080/19419899.2018.1453862 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L, Leeth EA, Johnson EK, Rosoklija I, Chen D, Aufox SA, & Finlayson C (2018). Attitudes toward ‘Disorders of Sex Development’ nomenclature among physicians, genetic counselors, and mental health clinicians. J Pediatr Urol, 14(5), 418 e411–418 e417. 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S (1991). Preparing people to change addictive behavior. In: New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Painter G, Rosen J, Barboza C, Lathia S, Libaw S, & Goulding M (2018). Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation Community Health Needs Assessment. http://www.curethekids.org/assets/documents/Pediatric-Brain-Tumor-Foundation-USC-Price-Community-Health-Needs-Assessment.pdf

- Pasterski V, Mastroyannopoulou K, Wright D, Zucker KJ, & Hughes IA (2014). Predictors of posttraumatic stress in parents of children diagnosed with a disorder of sex development. Arch Sex Behav, 43(2), 369–375. 10.1007/s10508-013-0196-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat TJ, Mkwanazi N, & Bland R (2013). Maternal HIV disclosure to HIV-uninfected children in rural South Africa: A Pilot study of a family-based intervention. BMC Public Health, 13, 147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolston AM, Gardner M, Vilain E, & Sandberg DE (2015). Parental Reports of Stigma Associated with Child’s Disorder of Sex Development. Int J Endocrinol, 2015, 980121. 10.1155/2015/980121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg DE, Gardner M, Callens N, Mazur T, Dsd-Trn Psychosocial Workgroup, t. D. S. D. T. R. N. A. A. N., & Accord A (2017). Interdisciplinary care in disorders/differences of sex development (DSD): The psychosocial component of the DSD-Translational research network. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet, 175(2), 279–292. 10.1002/ajmg.c.31561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg DE, Gardner M, & Cohen-Kettenis PT (2012). Psychological aspects of the treatment of patients with disorders of sex development. Semin Reprod Med, 30(5), 443–452. 10.1055/s-0032-1324729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider NM, Steinberg DM, Grosch MC, Niedzweeki C, & Depp Cline V (2016). Decisions about discussing traumatic loss with hospitalized pediatric patients: A needs assessment of a multidisciplinary medical team. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 4(1), 63–73. 10.1037/epp0000130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte MT, Armistead L, Murphy DA, & Marelich W (2021). Multisite longitudinal efficacy trial of a disclosure intervention (TRACK) for HIV + Mothers. Journal for Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 89(2), 81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, Darzi A, Bell D, & Reed JE (2014). Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf, 23(4), 290–298. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski AB, & Sandberg DE (2015). Parenting Children with Disorders of Sex Development (DSD): A Developmental Perspective Beyond Gender. Horm Metab Res, 47(5), 375–379. 10.1055/s-0034-1398561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidler EM, Peterson KE (2019). The impact of culture on disclosure in differences of sex development. Semin Pediatr Surg, 28(5), 150840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuki M, Schug J (2012). Relational mobility: A socioecological approach to personal relationships. In Decade of Behavior 2000–2010. Relationship Science: Integrating Evolutionary, Neuroscience, and Sociocultural Approaches. American Psychological Association, 137–151. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.