Abstract

In vitro, the TAFII60 component of the TFIID complex contributes to RNA polymerase II transcription initiation by serving as a coactivator that interacts with specific activator proteins and possibly as a promoter selectivity factor that interacts with the downstream promoter element. In vivo roles for TAFII60 in metazoan transcription are not as clear. Here we have investigated the developmental and transcriptional requirements for TAFII60 by analyzing four independent Drosophila melanogaster TAFII60 mutants. Loss-of-function mutations in Drosophila TAFII60 result in lethality, indicating that TAFII60 provides a nonredundant function in vivo. Molecular analysis of TAFII60 alleles revealed that essential TAFII60 functions are provided by two evolutionarily conserved regions located in the N-terminal half of the protein. TAFII60 is required at all stages of Drosophila development, in both germ cells and somatic cells. Expression of TAFII60 from a transgene rescued the lethality of TAFII60 mutants and exposed requirements for TAFII60 during imaginal development, spermatogenesis, and oogenesis. Phenotypes of rescued TAFII60 mutant flies implicate TAFII60 in transcriptional mechanisms that regulate cell growth and cell fate specification and suggest that TAFII60 is a limiting component of the machinery that regulates the transcription of dosage-sensitive genes. Finally, TAFII60 plays roles in developmental regulation of gene expression that are distinct from those of other TAFII proteins.

Initiation of transcription by RNA polymerase II (Pol II) in eukaryotic organisms requires assembly of multiprotein complexes at the core promoter of genes (22, 36). Assembly of TFIID is thought to precede and nucleate assembly of the other initiation complexes (TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIIE, TFIIF, and TFIIH) and RNA Pol II. The TFIID complex consists of TATA binding protein (TBP) and 10 to 12 TBP-associated factors (TAFIIs) (1, 5). Stability of the TFIID complex requires multiple TAFII-TAFII and TAFII-TBP interactions. TAFII60 binds TAFII40 and TAFII250, and elimination of TAFII60 leads to degradation of other TFIID subunits, suggesting that TAFII60 interactions in TFIID are important for integrity of TFIID (32, 54). Association of TAFII60 with TAFII40 involves histone fold motifs, similar to those of histones H4 and H3, respectively, that cocrystalize in a histone-like structure (57).

TFIID, but not TBP, can mediate activator-directed transcription in an in vitro RNA Pol II system, indicating that one function of TAFIIs is to respond to enhancer-bound activators (12). TAFII60 physically interacts with Dorsal, Bicoid, p53, and NF-κB activators in vitro, suggesting that TAFII60 mediates transcriptional activation by recruiting TFIID to particular promoters (21, 37, 42, 47, 60). Consistent with this proposal, reducing TAFII60 gene dose in the Drosophila melanogaster embryo alters the pattern of transcription of Dorsal gene targets, twist and snail (37, 60). Drosophila TAFII60 can also be cross-linked to the downstream promoter element (DPE), a core promoter element located downstream of the transcription start site in many TATA-less promoters, suggesting that TAFII60 may stabilize the interaction of TFIID with certain promoters, possibly in an activator-dependent manner (7, 8, 28).

The TAFII60 protein is highly conserved at the primary sequence level in all eukaryotic organisms examined to date (2). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, TAFII60 is essential and is required for the transcription of most RNA Pol II genes (32). However, it is difficult to assess how broadly TFIID-bound TAFII60 functions during transcription, since yeast TAFII60 is also a component of the SAGA (SPT-ADA-GCN5-acetyltransferase) histone acetyltransferase complex that affects transcription by altering chromatin structure (5, 20). In humans, the homologous HAT complex, PCAF (p300/CREB-binding protein-associated factor), contains a distinct TAFII60-like protein, PAF65α, and a similar situation may occur in Drosophila, which also encodes a TAFII60-like protein, TAFII60-2 (2, 5, 35). Thus, analysis of TAFII60 in Drosophila may provide a clearer picture of the role TAFII60 plays as a component of TFIID.

While significant progress has been made in understanding how TAFII60 contributes to transcriptional activation in vitro, it remains to be determined whether these mechanisms are valid in vivo and whether TAFII60 functions as a general regulator of transcription in multicellular eukaryotic organisms. To this end, we have examined the phenotypic and transcriptional consequences of mutating, reducing, or eliminating Drosophila TAFII60 protein in the germ line, in somatic cells, and at various points in development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila stocks and crosses.

Flies were cultured at 25°C on standard medium, unless otherwise noted. Initial characterization of TAFII60XS922 has been described previously (25). TAFII601, TAFII602, and TAFII603 alleles were kindly provided by J. Kennison, and P[hsp70-eTBP] transgenic flies were kindly provided by T. Burke and J. Kadonaga (7, 15). The P[hsp70-eTAF60] construct was generated by inserting the TAFII60 cDNA into the pCaSpeR-hs-FLAG vector. This construct expresses TAFII60 protein with a FLAG epitope tag on the N terminus (eTAF60). pCaSpeR-hs-FLAG was constructed by inserting the oligonucleotide 5′-AATTCAAAACATGGACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGCATATGAATTCGTT-3′ into the EcoRI and HpaI sites of pCaSpeR-hs. P-element-mediated transformation was performed by the method of Rubin and Spradling (40).

Four independent P[hsp70-eTAF60] lines were obtained that expressed eTAF60 and rescued TAFII60 mutants to adulthood. Rescued TAFII60 animals were obtained by crossing P[hsp70-eTAF60]/P[hsp70-eTAF60];TAFII60/TM6B Tb Hu males with P[hsp70-eTAF60]/P[hsp70-eTAF60];TAFII60/TM6B Tb Hu females and scoring larvae, pupae, or adults for loss of Tb and/or Hu dominant markers or by crossing P[hsp70-eTAF60]/P[hsp70-eTAF60];TAFII60 red bw/TM6B Tb Hu males with P[hsp70-eTAF60]/P[hsp70-eTAF60];TAFII60 red bw/TM6B Tb Hu females and scoring larvae for red Malphigian tubules or adults for brown eyes. Approximately 15 males and 15 females were rescue crossed, and the progeny were cultured at 25°C in an air-phase incubator and heat shocked every 8 h at 37°C for at least 10 days. Mitotic clones in the eye were generated using the FLP-FRT system (58). Germ line clones were generated using the ovoD and the FLP-FDS system (24).

CAT assays.

Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) assay samples containing 25 5-day-old adult females of the indicated genotype were homogenized in 500 μl of 250 mM Tris (pH 7.9), freeze-thawed twice in liquid N2, and incubated at 65°C for 10 min. Insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation, and five 80-μl aliquots of the supernatant were each combined with 50 μl of 5 mM chloramphenicol, 68 μl of 250 mM Tris (pH 7.9), and 2 μl of 14C-labeled acetyl coenzyme (0.1 μCi). The mixture was overlaid with scintillation fluid, and the rate of CAT activity was determined by measuring eight time points for 1 min over a period of ∼8 h. CAT activity rates were averaged for the 5 samples. At least four experiments were performed for each genotype.

Western blot analysis.

Adult flies of the indicated genotype and heat shock treatment were homogenized in 1× Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad), boiled for 3 min, and centrifuged for 15 min at 20,000 × g. Embryos of the indicated age were homogenized in buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg of leupeptin per ml, 1 μg of pepstatin per ml, and 150 mM NaCl and centrifuged for 15 min at 20,000 × g. Extracts were electrophoresed on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–10% polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore), according to standard procedures. Primary antibodies used were anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody M5 (diluted 1:1,000) (Sigma) and anti-TAFII60 monoclonal antibody (diluted 1:10) (kindly provided by R. Tjian) and were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse monoclonal secondary antibody (diluted 1:2,000) (Amersham) by the enhanced chemiluminescence method (Amersham).

Analysis of TAFII60 mutants.

The coding region and introns of the TAFII60 gene were sequences by the method of Schlag and Wassarman (43). Adult eyes were fixed and sectioned by the method of Tomlinson and Ready (49). Scanning electron microscopy of adult eyes was performed by the method of Kimmel et al. (27) Wings were mounted in 50% glycerol and imaged by phase-contrast microscopy. Testis squashes were performed by the method of Kemphues et al. (26). Eggs were imaged by dark-field microscopy.

Quantitation of total mRNA levels.

Total RNA was extracted from 30 3-day-old adult males or females of the indicated genotype with TRIzol (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA (10 μg) was denatured in a solution containing 17% formamide, 6% formaldehyde, and 14× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), split into two samples, and applied to a nitrocellulose membrane (Protran; Schleicher and Schuell) with a manifold apparatus (Manifold I; Schleicher and Schuell). Blots were washed twice with 10× SSC, baked at 80°C for 2 h, prehybridized in a solution containing 10% dextran sulfate, 1 M NaCl, 0.5% SDS, and 1 mg of sheared salmon sperm DNA per ml, and hybridized for 12 to 16 h with 32P-5′-end-labeled oligo(dT)20 (106 to 107cpm) or a 5S rRNA oligonucleotide (5′-GCCACCGACCATACCACGCTG-3′) probes. Signals were quantitated using a Storm system and ImageQuant program (Molecular Dynamics).

Quantitative PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from testes of the indicated genotype with TRIzol (Life Technologies). Quantitation of mRNA levels was performed using QuantumRNA 18S internal standard, according to the manufacturer's protocol (Ambion). Primers for specific mRNAs are as follows: Ste, 5′-TGCCCACGGTGTAAAAGCAAC-3′ and 5′-GCAGCAGCGAGAAGAAGATGTC-3′; Su(Ste), 5′-TCCCTATGCCTTGATGCCACTC-3′ and 5′-GCTTGGACCGAACACTTTGAAAC-3′; Ssl, 5′-TCCAGGACAAGTTCAATCTGACG-3′ and 5′-ATTCCAATGTGGGGTAGCGGGATG-3′; CK2 (beta subunit), 5′-ACCTGGTTCTGTGGACTTCGTG-3′ and 5′-AACTGATTAGTAGGACGCTTGGGAC-3′; and β2t, 5′-TCTAGATGGCGGCGATGAATAATAG-3′ and 5′-CTCGAG TCGTAACCCAGAAATCACAGC-3′. PCR products were resolved on 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gels and quantitated using a Storm system and ImageQuant program (Molecular Dynamics).

RESULTS

Sev transcription and Rh4 transcription are affected by TAFII60 gene dose.

We previously identified an X-ray-induced mutant allele of TAFII60, TAFII60XS922, as a dominant suppressor of the rough eye phenotype cause by a sev-Ras1V12 transgene (25). The Drosophila compound eye is composed of approximately 800 identical units, called ommatidia (56). Each ommatidium contains 8 photoreceptor neurons (R1 to R8) and 12 nonneuronal cells (4 cone cells and 8 pigment cells). During ommatidial assembly, the R7 cell fate is determined by a signal transduction pathway that is initiated by activation of the Sevenless (Sev) receptor tyrosine kinase. Sev activation triggers a signaling cascade mediated by the Ras1 GTPase. Expression of a constitutively active form of Ras1, Ras1V12, in R7 and cone cell precursors, under control of sev cis-regulatory sequences, bypasses the requirement for Sev activation and transforms cone cell precursors into R7 cells (3, 6, 16). In addition to TAFII60XS922, the Df(3L)kto2 deficiency that removes the TAFII60 gene, dominantly suppresses the sev-Ras1V12 rough eye phenotype, indicating that TAFII60XS922 is a loss-of-function allele (Fig. 1 and data not shown).

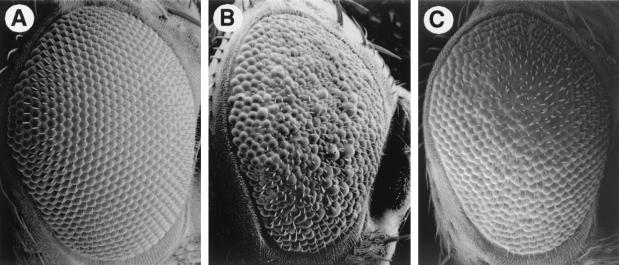

FIG. 1.

TAFII60XS922 suppresses the rough eye phenotype of sev-Ras1V12. Scanning electron micrographs of wild-type (A), P[sev-Ras1V12]/+ (B), and TAFII60XS922/P[sev-Ras1V12] (C) eyes are shown (anterior to the right).

Suppression of the extra R7 cell phenotype by TAFII60XS922 was monitored by counting the number of R7 photoreceptors in apical tangential sections of adult fly retinae (Table 1). In the sev-Ras1V12 background, heterozygous TAFII60XS922 flies had approximately twofold-less R7 cells per ommatidium compared to flies that had two wild-type copies of TAFII60. Thus, mutating one copy of TAFII60 in a diploid organism improves the regularity of the external eye morphology and reduces the number of extra R7 cells caused by sev-Ras1V12. Since the rate of cone-to-R7 cell transformation is exquisitely sensitive to the level of Ras1V12 expression, TAFII60 mutations may suppress the rough eye phenotype by reducing the level of sev-Ras1V12 transcription (30). This predicts that TAFII60 mutations would suppress phenotypes caused by other sev-driven transgenes.

TABLE 1.

Effect of a TAF60 mutation on transcription in the eyea

| Genotype | Ommatidia in sectionsb

|

Relative CAT activityc

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of R7 cells per ommatidium | % wild-type ommatidia | Rh3-CAT/+ | Rh4-CAT/+ | |

| +/+ | 3.1 (160) | 7.7 (494) | 100 (5) | 100 (4) |

| TAF60XS922/+ | 1.5 (197) | 29.7 (475) | 94 ± 15 (5) | 51 ± 8 (4) |

Flies of the indicated genotypes were assayed for eye phenotypes or CAT activity

Tangential sections of adult retinae were scored for R7 photoreceptors in the sev-Ras1V12/+ background or wild-type ommatidia in the sev-rough/+ background. The numbers of ommatidia scored are shown in parentheses. Wild-type flies contain one R7 cell per ommatidium.

CAT assays were performed on extracts prepared from adult flies. The CAT activity of control extracts prepared from flies carrying an Rh3-CAT or Rh4-CAT transgene in an otherwise wild-type background was arbitrarily set at 100%, and the activity of flies heterozygous for TAF60XS922 was normalized to the appropriate control. The number of independent assays is shown in parentheses. See text for details.

Accordingly, TAFII60XS922 dominantly suppressed the R7 to outer photoreceptor cell transformation caused by sev-rough (Table 1) (4, 27). Rough is a homeodomain protein that is expressed in R2, R5, R3, and R4 outer photoreceptor precursor cells and specifies the fate of R2 and R5 (4, 27, 48). Ectopic expression of rough in the R7 precursor cell changes its fate to that of an outer photoreceptor. In the sev-rough background, heterozygous TAFII60XS922 flies had approximately fourfold-more wild-type ommatidia than flies that had two wild-type copies of TAFII60. TAFII60XS922 also dominantly suppressed rough eye phenotypes caused by sev-phyl, sev-yanACT, and sev-Notchact/nucl (data not shown) (9, 38, 52). Since sev-Ras1V12, sev-phyl, sev-rough, sev-yanACT, and sev-Notchact/nucl had different effects on eye development but were similarly affected by a mutation in TAFII60, suppression may result from reduced levels of transcription from the sev-driven transgenes.

To directly examine the effect of the TAFII60XS922 mutation on transcription in the eye, we quantitated the activity of transgenes that express the reporter gene product (CAT) under the regulation of Rh3 or Rh4 enhancer and promoter sequences (17). Rh3 and Rh4 direct expression in nonoverlapping subsets of R7 cells in adult retinae. CAT activities for extracts prepared from Rh3-CAT/+;TAFII60XS922/+ flies were similar to those for control extracts prepared from Rh3-CAT/+;+/+ flies (Table 1). However, extracts prepared from Rh4-CAT/+;TAFII60XS922/+ flies had approximately twofold-less CAT activity than control extracts prepared from Rh4-CAT/+;+/+ flies. In summary, these data indicate that TAFII60 is required for transcription of the sev and Rh4 genes but not the Rh3 gene and that the level of TAFII60 expression is critical for the transcription of some genes in vivo.

Molecular lesions in TAFII60 that cause lethality.

In addition to TAFII60XS922, three other recessive lethal TAFII60 alleles have been described. TAFII601, TAFII602, and TAFII603 were isolated in a screen for lethal mutations in the 76B chromosomal region (15). To identify regions of the TAFII60 protein that are important for its function in vivo, we sequenced the TAFII60 gene from each allele. TAFII60XS922 contains an in-frame insertion of 6 bp (TACTAC) that encodes two tyrosine (Y) residues adjacent to position 207 of the protein (Fig. 2A). TAFII601 contains a 29-bp deletion that causes a frameshift at amino acid 298 of the 593-amino-acid TAFII60 protein. TAFII602 contains a single missense mutation that changes tryptophan (W) 128 to arginine (R) (Fig. 2B). TAFII603 contains a G-to-A transition at the +1 position of the first intron 5′ splice site, which may affect the efficiency of splicing of the TAFII60 pre-mRNA.

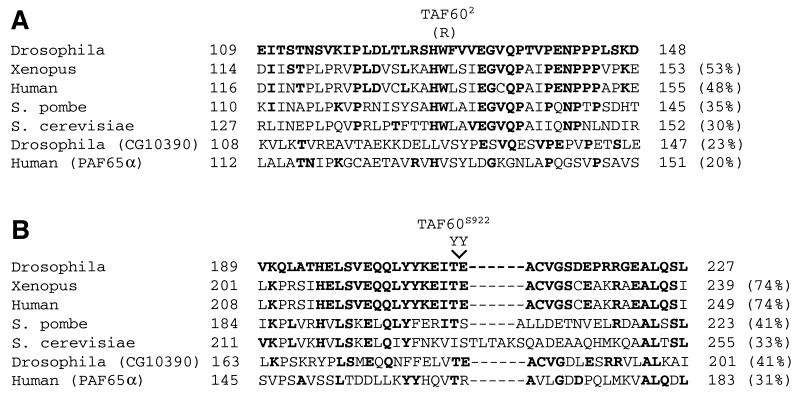

FIG. 2.

TAFII60 mutations disrupt residues or domains that are conserved in metazoan family members. Sequences of a region surrounding the tryptophan (W)-to-arginine (R) mutation in TAFII602 (A) and a region surrounding the two tyrosine (Y) insertion in TAFII60XS922 (B) from Drosophila melanogaster, Xenopus laevis, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae as well as TAFII60-like proteins, Drosophila melanogaster CG10390 (also denoted TAFII60-2), and human PAF65α are shown. Residues identical to those in TAFII60 are indicated in bold type, and the percent sequence identity of each region to Drosophila TAFII60 is indicated in parentheses to the right of the sequences. Amino acid positions of the ends of each sequence are shown to the left and right of each sequence. Dashes indicate gaps introduced to maximize sequence alignment.

Amino acid changes in TAFII60XS922 and TAFII602 are located within regions that are conserved in metazoan TAFII60 proteins but not in TAFII60-like proteins, such as PAF65α and TAFII60-2 (Fig. 2). This suggests that these regions carry out functions that are unique to TFIID. Furthermore, the TAFII60XS922 lesion defines a region that is not conserved in Schizosaccharomyces pombe or Saccharomyces cerevisiae TAFII60 proteins, possibly defining a function that is particular to higher eukaryotes. Unfortunately, it is difficult to ascribe a function to these regions because they do not display sequence similarity to previously described protein motifs and have not been implicated in specific protein-protein interactions.

TAFII60 is required throughout Drosophila development.

Embryos transheterozygous for TAFII60 alleles die during the first or second larval instar stage, with the exception of TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 flies which die late in the pupal stage (Table 2). Survival of TAFII60 mutants through embryonic and early larval stages is probably dependent on the maternal contribution of TAFII60 mRNA, and zygotic expression is necessary during the second larval instar. Maternal expression of TAFII60 appears to be required for oogenesis as homozygous germ line clones of TAFII60XS922 failed to produce eggs. TAFII60 is also required for cell proliferation and/or survival, since mitotic clones of TAFII60XS922 generated in the eye were not recovered, unlike the twin spot of wild-type tissue generated by the same recombination event. Thus, TAFII60 is essential for the development of both germ cells and somatic cells. Furthermore, the essential nature of TAFII60 suggests that TAFII60 and TAFII60-2, a TAFII60 family member that is ubiquitously expressed in flies (N. Aoyagi and D. A. Wassarman, unpublished observation), have nonredundant functions.

TABLE 2.

Results of TAF60 complementation and lethal phase analyses

| Genotype | % Viability by complementation analysisa

|

Lethal phase analysisb

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TAF602

|

TAF60XS922

|

TAF603

|

TAF601

|

TAF602

|

TAF60XS922

|

TAF603

|

TAF601

|

|||||||||||||||||

| A | B | C | A | B | C | A | B | C | A | B | C | A | B | C | A | B | C | A | B | C | A | B | C | |

| TAF602 | <1 | 0 | <1 | EL | EL | EL | ||||||||||||||||||

| TAF60XS922 | 0 | 20 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 6 | LP | C | C | EL | EP | C | ||||||||||||

| TAF603 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 22 | 0 | 0 | <1 | EL | EL | EL | EL | C | C | EL | EL | EL | ||||||

| TAF601 | 0 | 16 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 18 | 16 | 0 | 0 | <1 | EL | C | C | EL | LP | C | EL | C | C | EL | EL | EL |

Percent viability was determined for each homozygous and transheterozygous combination of TAF60 alleles under the following conditions: A, not heat shocked and lacking the P[hsp70-eTAF60] transgene; B, not heat shocked and has two copies of the P[hsp70-eTAF60] transgene; C, heat shocked and has two copies of the P[hsp70-eTAF60] transgene (heat shock treatment consisted of 30 min at 37°C every 8 h). Percent viability is defined as the number of rescued homozygous or transheterozygous progeny divided by the total number of progeny (150 > n > 1,200). Fully viable combinations should be 33%. <1 denotes that flies were observed at a rate of less than 1%.

The lethal phase was determined for each homozygous and transheterozygous combination of TAF60 alleles under the same conditions as in footnote a (heat shock and the P[hsp70-eTAF60] transgene). Abbreviations: C, complement; EL, first- or second-instar larval stage; EP, white pupal stage; LP, dark pupal stage.

The inability to eliminate the maternal contribution of TAFII60 in the egg or to produce homozygous TAFII60 mutant cells in adult tissues makes it difficult to determine the developmental and transcriptional requirements for TAFII60 in the germ line, larvae, pupae, and adults. To circumvent this problem, we attempted to rescue TAFII60 mutants with an inducible, ubiquitously expressed TAFII60 transgene. We generated transgenic lines that expressed the TAFII60 cDNA under control of the heat shock protein 70 (hsp70) promoter. Transgenic TAFII60 protein (designated eTAF60) was tagged with the FLAG epitope so that it could be distinguished from endogenous TAFII60 protein. In the absence of heat shock treatment, eTAF60 expression was not detected by Western blot analysis of adult or 12- to 24-h-old embryo extracts but was detected in 0- to 12-h-old embryo extracts, indicating higher levels of leaky expression early in embryonic development (Fig. 3A and C). After a 30-min heat shock at 37°C, eTAF60 was detected with either an anti-FLAG antibody or an anti-TAFII60 antibody at all stages of development (Fig. 3A and data not shown). Expression of eTAF60 perdured for 8 to 12 h after heat shock treatment of adult flies (Fig. 3B).

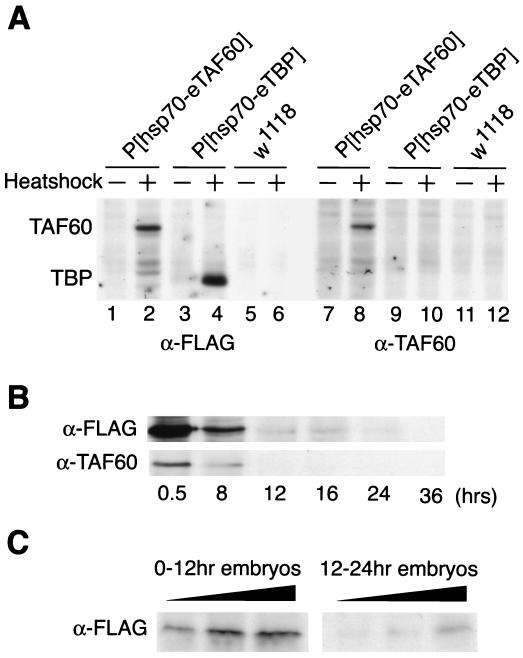

FIG. 3.

Expression analysis of transgenic FLAG-tagged TAFII60 protein (eTAF60). (A) Western blot analysis of eTAF60 from whole-cell extracts of heat-shocked (+) and non-heat-shocked (−) adult flies. Lanes 1, 2, 7, and 8, extracts from flies carrying the P[hsp70-eTAF60] transgene; lanes 3, 4, 9, and 10, extracts from flies carrying the P[hsp70-eTBP] transgene which expresses FLAG-tagged TBP; lanes 5, 6, 11, and 12, extracts from w1118 flies that do not contain a transgene (7). Lanes 1 to 6 were probed with an antibody to the FLAG epitope (α-FLAG), and lanes 7 to 12 were probed with an antibody to TAFII60 (α-TAF60). (B) Western blot analysis to examine the perdurance of eTAF60 expression after a 30-min heat shock treatment at 37°C. Extracts were prepared from flies at the times indicated after heat shock and then probed with an α-FLAG or α-TAF60 antibody. (C) Western blot analysis of eTAF60 expression in non-heat-shocked embryos. Blots were probed with an α-FLAG antibody. Lanes 1 to 3 contain increasing amounts of extract from 0- to 12-h-old embryos, and lanes 4 to 6 contain increasing amounts of extract from 12- to 24-h-old embryos.

It is important to note that the level of eTAF60 protein produced after heat shock induction is significantly higher than endogenous TAFII60 protein level (Fig. 3A, compare lane 8 to lane 12). However, in wild-type flies, expression of eTAF60 throughout development did not appear to cause any abnormalities, suggesting that overexpression of TAFII60 does not interfere with endogenous transcriptional mechanisms.

In the absence of heat shock treatment, some transheterozygous TAFII60 mutants survived to adulthood, indicating that low levels of eTAF60 expression are sufficient to complement some mutants. By using a variety of heat shock regimens, we determined that heat shock treatment every 8 h throughout development was necessary to rescue homozygous TAFII60 adult flies. However, even though this regimen provided a constant source of TAFII60 protein, the normal number of viable adult flies was not obtained with any transheterozygous mutant combination, indicating that the level or timing of TAFII60 expression is critical during development. This proposal is consistent with the finding that adult phenotypes are less severe in adult flies that are rescued under heat shock conditions (i.e., high TAFII60 conditions) than those that are rescued at 25°C (i.e., low TAFII60 conditions) (Table 2 and Fig. 4 and 5).

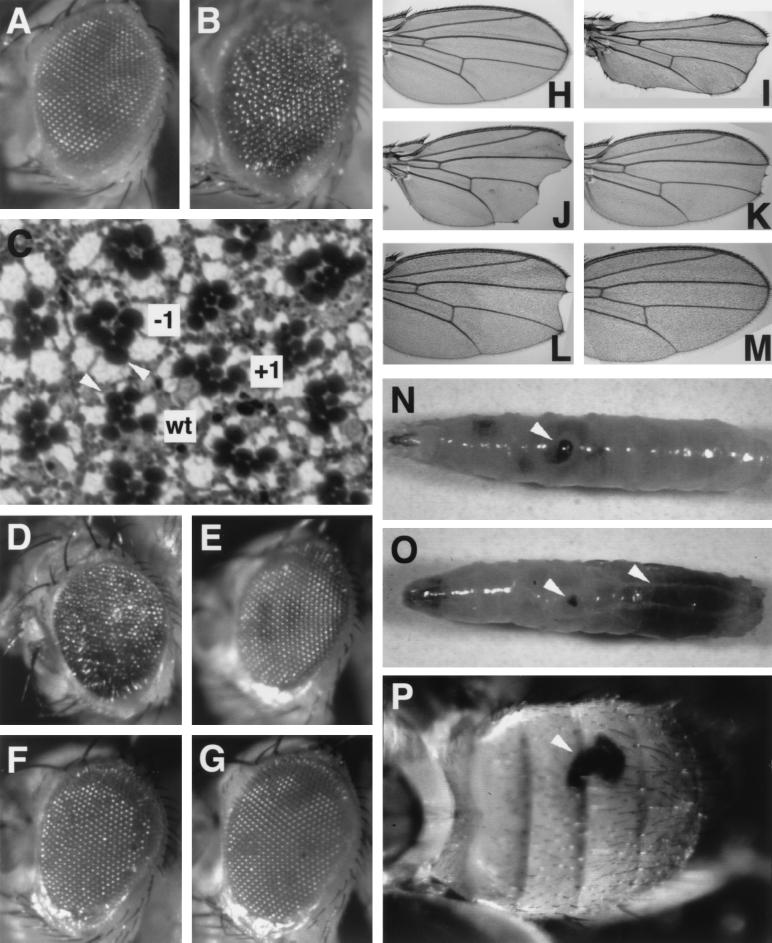

FIG. 4.

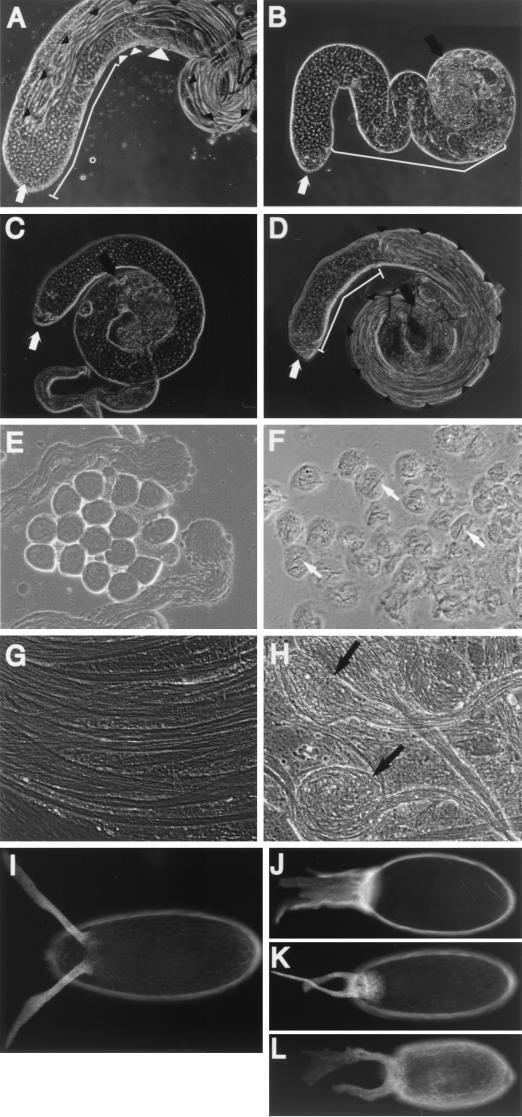

Phenotypes of rescued TAFII60 mutant flies. All of the flies shown carry a copy of the P[hsp70-eTAF60] transgene on each of the second chromosomes. (A) A heterozygous heat-shocked TAFII60XS922 eye that is phenotypically wild type, (B) a homozygous heat-shocked TAFII60XS922 eye, (C) a tangential section of a heat-shocked TAFII60XS922 homozygous eye [arrowheads indicate representative photoreceptor rhabdomeres that are larger in mutant ommatidia (−1) than in wild-type (wt) ommatidia], (D) a non-heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 male eye, (E) a heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 male eye, (F) a non-heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 female eye, (G) a heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 female eye, (H) a heat-shocked TAFII60XS922 heterozygous wing, (I) a heat-shocked TAFII60XS922homozygous wing, (J) a non-heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 male wing, (K) a heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 male wing, (L) a non-heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 female wing, (M) a heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 female wing, and (N, O, and P) melanotic pseudotumors (arrowheads) in heat-shocked homozygous TAFII603 third-instar larvae (N and O) and an adult abdomen (P).

FIG. 5.

Testis and egg phenotypes of rescued TAFII60 mutant flies. The flies shown in panels A to H carry a copy of the P[hsp70-eTAF60] transgene on each of the second chromosomes. The images in panels A to D, E and F, G and H, and I to L were photographed at the same magnification. (A) A heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/+ testis that is phenotypically wild type, (B) a heat-shocked TAFII60XS922 homozygous testis, (C) a non-heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 testis, (D) a heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 testis, (E) a high-magnification image of primary spermatocytes from heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/+ testis, (F) a high-magnification image of primary spermatocytes from heat-shocked TAFII60XS922 homozygous testis, (G) a high-magnification image of sperm tails from heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/+ testis, and (H) a high-magnification image of sperm tails from heat-shocked TAFII60XS922 homozygous testis. In panels A to D, thick white arrows indicate the apical tip of the testis, white lines indicate the region that contains primary spermatocytes, small white arrowheads indicate meiotic cells, large white arrowheads indicate postmeiotic cells, thick black arrows indicate degenerate spermatocytes, and small black arrowheads indicate sperm bundles. In panel F, white arrows indicate crystal structures. In panel H, black arrows indicate aberrant axonemes. (I) A wild-type egg shell. The dorsal pattern is identified by a pair of dorsal appendages separated by a narrow gap. (J to L) Rescued TAFII60 eggshells that appear dorsalized (J), ventralized (K), and have a mixture of dorsalized and ventralized characteristics (L).

In the case of mutant combinations, such as TAFII60XS922/TAFII601, that required heat shock treatment for adult rescue, cessation of heat shock treatment during larval or pupal stages precluded adult rescue, indicating that a high level of TAFII60 expression is required during these developmental stages. However, cessation of heat shock treatment during the adult stage did not affect the life span of the flies. Thus, the requirement for TAFII60 appears to be either reduced or dispensable for the postmitotic and fully differentiated cells of the adult fly.

TAFII60 is required for a variety of developmental events.

Homozygous and transheterozygous TAFII60 flies that were rescued to adulthood by the eTAF60 transgene, exhibited a common set of developmental phenotypes (Fig. 4 and 5). Abnormalities were exhibited in organs derived from imaginal tissues and in testes and ovaries. Development of these tissues may be more sensitive to the level or timing of TAFII60 expression, or as anecdotal evidence suggests, the hsp70 promoter may not be efficiently induced in the germ line, which may explain why the P[hsp70-eTAF60] transgene is unable to rescue spermatogenesis or oogenesis. We most thoroughly characterized the phenotypes of rescued homozygous TAFII60XS922 and transheterozygous TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 flies because they were the easiest to obtain.

TAFII60 is required for cell fate specification in the eye.

Rescued TAFII60 adults had an external rough eye phenotype (Fig. 4, compare panels A and B). The phenotype was less severe if the flies were raised under heat shock conditions (Fig. 4, compare panel D to panel E and panel F to panel G) and was less severe in females than males (Fig. 4, compare panel D to panel F). The rough eye phenotype was due to a change in the number and size (see below) of photoreceptor cells. In wild-type flies, apical tangential sections reveal a trapezoid pattern of photoreceptors with six large outer photoreceptors (R1 to R6) forming the perimeter of the trapezoid and one small inner photoreceptor (R7) in the center of the trapezoid (Fig. 4C) (56). In TAFII60 rescued flies, ommatidia were either missing an inner or outer photoreceptor or had an extra inner or outer photoreceptor. In flies that had the strongest rough eye phenotype, approximately 25% of ommatidia contained an abnormal number of photoreceptors. Thus, TAFII60 is involved in specifying photoreceptor cell identities.

TAFII60 is required for wing development.

Rescued TAFII60 adults had a notched wing phenotype (Fig. 4, compare panel H to panel I). Regions of the wing margin were most commonly missing at the tip, but wing veins and bristles appeared normal. As occurred in the eye, the wing phenotype was less severe if the flies were raised under heat shock conditions (Fig. 4, compare panels J and K and panels L and M) and was less severe in females than males (Fig. 4, compare panels J and L and panels K and M).

TAFII60 may regulate cell growth.

Rescued homozygous TAFII60XS922, TAFII602, and TAFII603 larvae and adults had dark black masses of cells phenotypically similar to melanotic pseudotumors described in flies mutant for genes that regulate cell growth, dE2F, dDP, S6 ribosomal protein (RpS6), and S21 ribosomal protein (RpS21) (Fig. 4N, O, and P) (39, 46, 50). Melanotic pseudotumors arise in larvae when groups of aberrant cells, often imaginal precursor cells, are recognized by plasmatocytes and lamellocytes in the immune system and are encapsulated in melanized cuticle (10). In TAFII60 mutants, small pseudotumors were first observed in second-instar larvae and grew as the larvae developed.

In addition, in mutant ommatidia, most rhabdomeres, the light-sensitive membrane of photoreceptors, were larger than in wild-type ommatidia, however, the size of the eye did not appear to be larger (Fig. 4C). This phenotype resembles that of dE2F and Rbf mutants in which the size of individual cells are affected but the size of the organ is not altered (33).

TAFII60 is required for spermatogenesis.

Rescued TAFII60 adult males were sterile. To determine the defect that caused sterility, testes were dissected from heat shock rescued TAFII60 males and analyzed by phase-contrast microscopy (Fig. 5). In wild-type males, the various stages of spermatogenesis are ordered from the tip to the base of the testis (Fig. 5A) (18). At the tip, stem cells divide to produce a spermatogonium cell that undergoes four rounds of mitotic division to produce a cyst of 16 primary spermatocyte cells. After the fourth division, spermatocytes cease mitosis and initiate the meiotic program which contains an extended G2 phase, during which time cells grow considerably and transcription occurs at a high level. Upon completion of the growth phase, most transcription is shut down and primary spermatocytes undergo meiosis I and II, resulting in a cyst of 64 haploid spermatids. Spermatid bundles then migrate toward the base of the testis and differentiate, which is marked by a number of morphological changes; subcellular compartments are remodeled, a sperm tail containing the axoneme (a microtubule-based organelle for motility) is generated, DNA condenses, and nuclei change shape.

TAFII60 mutant alleles displayed a range of spermatogenesis defects (Fig. 5). Heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/+ flies that carry two copies of the P[hsp70-eTAF60] transgene were phenotypically normal, indicating that expression of the transgene and inactivation of one copy of TAFII60 does not interfere with spermatogenesis (Fig. 5A). In a more severe case, such as heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 flies, postmeiotic stages, including mature spermatids, were observed but were less abundant than in wild-type flies (Fig. 5, compare panels A and D). Finally, in the most severe case, such as non-heat-shocked TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 flies, proliferation of stem cells to primary spermatocytes was normal (Fig. 5B and C). Primary spermatocytes became mature in size and occupied an abnormally large portion of the testis but degenerated without initiating meiotic chromosome condensation (13). Subsequent stages, beginning with the growth phase, were absent or defective. Thus, transcriptional regulation by TAFII60 is required during spermatogenesis for meiotic cell cycle progression and spermatid differentiation.

TAFII60 is required for dorsoventral patterning of the egg.

Rescued TAFII60 adult females were sterile and laid eggs that had polarity defects. In wild-type eggs, follicle cells on the dorsal side of the egg form two dorsal respiratory appendages called dorsal appendages that serve as a marker for dorsal identity (Fig. 5I) (51). By examination of dorsal appendages, eggs produced by rescued TAFII60 females had phenotypes that ranged from strongly dorsalized (Fig. 5J), where dorsal appendage tissue was no longer localized to a portion of the eggshell but instead surrounded the egg, to strongly ventralized (Fig. 5K), where dorsal appendages were positioned closer together than in wild-type eggs. Finally, some eggs were small, had thin egg shells, and appeared both dorsalized and ventralized (Fig. 5L). Asymmetric distribution of gurken mRNA and protein to the dorsal side of the egg is critical to the establishment of dorsal follicle cell fates (34). Localized Gurken protein activates the epidermal growth factor receptor triggering a signal transduction pathway that specifies dorsal follicle cell fates (51). By in situ hybridization, we found that gurken mRNA levels and localization were normal in rescued TAFII60 egg chambers, suggesting that TAFII60 is required for a downstream event in the pathway (data not shown).

Transcription in TAFII60 mutants.

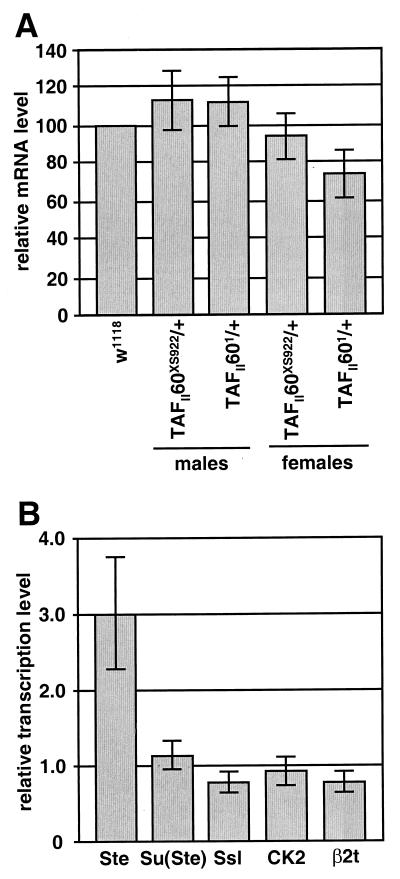

Since heterozygous TAFII60XS922 mutants dominantly affected the transcription of sev- and Rh4-driven transgenes in the eye, we were interested in determining if TAFII60XS922 had a general effect on the transcription of endogenous mRNA-encoding genes. While heterozygous TAFII60XS922 mutants appeared phenotypically normal at all stages of development, small changes in transcription may have occurred but were not deleterious to development. As an initial step to address this question, we analyzed the level of poly(A)+ mRNA in TAFII60XS922/+ mutants versus w1118 control flies. Total RNA was isolated from TAFII60XS922/+ and w1118 flies and was hybridized with 32P-labeled oligo(dT) and 5S rRNA probes. The ratio of oligo(dT) to 5S rRNA signal was used as a measure of mRNA level. 5S rRNA, which is transcribed by RNA Pol III and therefore should not be affected by TAFII60 mutations, served as a control for total RNA levels. This analysis revealed that for both male and female flies, total mRNA levels were statistically similar between TAFII60XS922/+ and w1118 strains (Fig. 6A). Total mRNA levels were also not affected in male or female heterozygous TAFII601 flies. Thus, mRNA levels do not appear to be globally affected by reducing the dose of TAFII60 twofold. However, the sensitivity of the assay does not exclude the possibility that transcription levels are affected less than twofold, as was observed for Rh4-CAT and genes expressed in testes (Table 1 and Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Analysis of transcription in TAFII60 mutant flies. (A) Analysis of total mRNA levels in heterozygous TAFII60 mutants. The ratio of poly(A)+ RNA to 5S rRNA was determined for TAFII60 mutant adult males and females and normalized to that of w1118 males or females. (B) The transcription level of Ste, Su(Ste), Ssl, CK2, and β2t was determined by quantitative PCR from total mRNA extracted from homozygous TAFII60XS922 testes and normalized to w1118 levels.

Further analysis of spermatogenic stages in rescued TAFII60 flies revealed phenotypes that suggested specific transcriptional targets for TAFII60. First, needle-like structures were observed in spermatocytes (compare Fig. 5E to F). The needles were similar in size and shape to those observed in X/O males lacking a Y chromosome and in recessive mutants of Stellate (Ste), Suppressor of Stellate [Su(Ste)], Stellate-interacting gene [sting (sti)], and hsp83 (also known as scratch) (19, 44, 59). Ste mRNA levels are 30- to 70-fold-more abundant in X/O males or males deficient for the Su(Ste) locus than in wild-type males. Overexpression of Ste genes results in self-aggregation of the Ste protein in needle-shaped crystals. The Ste protein is highly similar to the β subunit of Drosophila casein kinase 2 (CK2) and in vitro can interact with the α subunit of casein kinase 2 to form a complex with properties similar to an active α2β2 holoenzyme (44). The Su(Ste) and Suppressor of Stellate-like (Ssl) proteins are also highly similar to the β subunit of CK2. This suggests that crystals in TAFII60 mutants may be due to reduced expression of a CK2 family member.

By quantitative PCR, we examined mRNA levels for Ste, Su(Ste), Ssl, and CK2 in testes from rescued TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 flies relative to w1118 control flies. Ste mRNA levels increased approximately threefold in TAFII60 mutant flies, but the level of the other mRNAs was not affected (Fig. 6B). The second phenotype that suggested a gene target for TAFII60 is that spermatid bundles remained spherical and did elongate (compare Fig. 5G to H). A similar phenotype is observed in mutants of a testis-specific β2-tubulin (β2t) that affect axonemal microtubules of the sperm tail (26). However, quantitative PCR revealed that β2t mRNA levels in TAFII60XS922/TAFII602 flies were not significantly different than in control w1118 flies. The most-straightforward interpretation of these observations is that reduced levels of TAFII60 protein either cause minor changes in transcription of the genes we examined or affect other genes.

DISCUSSION

We have presented the following evidence in Drosophila. (i) Two evolutionarily conserved regions of TAFII60 are critical for viability. (ii) TAFII60 is essential for development of germ cells and somatic cells. (iii) TAFII60 is required, to various degrees, during all stages of development. (iv) Imaginal disk development and gametogenesis are particularly sensitive to the level of TAFII60 expression. (v) Males are more sensitive than females to the level of TAFII60 expression. (vi) TAFII60 is limiting in the eye for the transcription of the sev and Rh4 genes. (vii) A twofold reduction in the dose of TAFII60 does not affect bulk mRNA transcription. (viii) TAFII60 mutant phenotypes are consistent with roles for TAFII60 in cell fate specification, cell growth, and cell proliferation.

Based on in vitro defined mechanistic roles for TAFII60, as a structural component of TFIID, as a coactivator, and as a promoter-interacting factor, one can imagine that the developmental and transcriptional defects observed in TAFII60 mutants are due to disassembly of TFIID, disruption of interactions with activators, or disruption of interactions with promoters. At present, it is difficult to discriminate between these potential mechanisms, but our data indicate that the defective mechanism can be compensated by overexpression of wild-type TAFII60 protein. The degree of compensation is correlated to the level of TAFII60 expression, suggesting that the affinity of genes for TAFII60 varies greatly in vivo.

Interestingly, overexpression of TAFII60 (i.e., eTAF60) does not affect development or presumably transcriptional activity in wild-type flies. These data indicate that phenotypes observed in rescued TAFII60 mutants are not due to excessive levels of TAFII60 and that TAFII60 protein that exceeds normal endogenous TAFII60 levels is either nonfunctional or induces minor changes in transcription that lead to nondetectable phenotypic alterations. These data contradict the observation that overexpression of TAFII60 or other TAFIIs in Drosophila or mammalian tissue culture cells modulates transcription directed by specific activators and hints at the existence of an in vivo mechanism that buffers the transcription level of TAFII-regulated genes (11, 14, 31).

Mutant phenotypes identify dosage-sensitive TAFII60 gene targets.

TAFII60 is expressed ubiquitously and is essential for cell survival or proliferation, yet specific developmental pathways were disrupted when TAFII60 levels were reduced but not eliminated, suggesting that for a subset of TAFII60-regulated genes, a reduction in the level of transcription of less than twofold has phenotypic consequences. This hypothesis is supported by two lines of evidence. First, only minor changes in transcription levels were observed in TAFII60 mutants. Suppression of the sev-Ras1V12 eye phenotype by a TAFII60 mutation is most likely due to a small change in expression of the sev-Ras1V12 transgene, as we have previously shown that a twofold reduction in the number of R7 cells in sev-Ras1V12 flies resulted from a less than twofold reduction in the level of sev-Ras1V12 transcription (Table 1) (30). Furthermore, a less than twofold change was observed in Rh4 transcription and no change was observed in bulk mRNA transcription or the transcription of numerous genes expressed in testes (Table 1 and Fig. 6).

Second, TAFII60 mutant males had more severe phenotypes than females, suggesting that TAFII60 mutations affect the transcription of Y-chromosome genes or dosage-compensated genes in males. In Drosophila, transcription of most X-linked genes in males is increased approximately twofold to compensate for the presence of only a single X chromosome (29). Mutations in components of the dosage compensation machinery cause male-specific lethality. TAFII60 mutations also cause male lethality. The male/female ratio for rescued homozygous TAFII60XS922 flies was 1:4.3 (n = 283). In addition, rescued TAFII60 mutant males had stronger eye and wing phenotypes than rescue females (Fig. 4). This may be due to downregulation of the sev and Notch genes, which reside on the X chromosome. Sev mutations cause loss of R7 cells in the eye, and Notch mutations cause notches along the wing margin, phenotypes that were stronger in rescued TAFII60 males than females (Fig. 4). These findings imply that TAFII60 is required for the twofold upregulation of genes on the X chromosome in males and, more generally, that TAFII60 is a limiting component of the machinery that regulates the transcription of dosage-sensitive genes.

Does a DPE specify the requirement for TAFII60?

In the absence of a TATA box, the DPE functions in conjunction with the Inr element for binding of TFIID. Cross-linking experiments have shown that TAFII60 is in intimate contact with the DPE, suggesting that TAFII60 mutations would affect transcriptional activation of DPE-containing genes (7, 8, 28). We have found that in TAFII60 mutant testes, the steady-state transcription levels of the DPE- and Inr-containing genes Su(Ste) and Ssl were not affected and Ste levels increased approximately threefold (Fig. 6B) (28) (http://www.biology.ucsd.edu/labs/Kadonaga/DCPD.html). We have also found that TAFII60 mutations affect the sev and Rh4 genes but not the Rh3 or β2t genes (Table 1). The sev promoter contains an atypical TATA box (TTAAAA), a consensus Inr element and no DPE, both Rh4 and Rh3 contain consensus TATA boxes and Inr elements and no DPEs, and β2t contains an Inr element but no TATA box or DPE (3, 6, 17, 41). These results suggest that TAFII60 is not absolutely required for the transcription of DPE-containing genes, a conclusion that was also reached upon analysis of transcriptional defects in TAFII40 mutant flies (45). Alternatively, the presence or absence of a DPE within these genes may be incorrect because sequence similarity may not accurately predict functional DPEs or the characterized TAFII60 mutations, which are probably not null mutations, may not affect DPE recognition. The latter alternative, that different TAFII60 alleles affect different TAFII60 functions, is consistent with TAFII60 complementation analysis which showed that TAFII60 alleles are not equivalent, some combinations can be complemented while others cannot.

Requirements for TAFII60 overlap with but are distinct from other TAFIIs.

Our results support the conclusion, drawn from gene expression studies in yeast and biochemical studies in reconstituted transcription systems, that genes differ in their requirement for TAFIIs. Genetic studies presented here and elsewhere indicate that Drosophila TAFII60, TAFII110, and TAFII250 participate in transcriptional activation of the sev, twist, and snail genes, but differences in phenotypes of TAFII60 and TAFII250 mutant flies suggest that the transcription of some genes requires TAFII60 and TAFII250 to different extents (37, 53, 60). (i) In TAFII60 mutant flies, notches occur along the wing margin but wing veins appear normal, while in TAFII250 mutant flies, deltas form at the distal end of wing veins but the wing margin appears normal. These phenotypes are similar to those of Notch and Delta mutants, respectively. Notch and Delta are components of the Notch signaling pathway that includes many of the relatively few haploinsufficient genes in Drosophila, including Notch and Delta. Thus, TAFII60 and TAFII250 may regulate different dose-sensitive genes in the Notch pathway. (ii) TAFII60 and TAFII250 are both required for cell fate specification in the eye, but only TAFII60 mutations affect the size of photoreceptor cells, suggesting a TAFII60-specific role in regulating genes involved in growth control. (iii) TAFII60 and TAFII250 mutants are sterile females, while TAFII60 mutants are sterile males, suggesting TAFII60-specific gene targets during spermatogenesis. Recently, a testis-specific isoform of TAFII80, called Cannonball (Can), has been shown to be required for transcriptional regulation during spermatogenesis (23). can mutations, like TAFII60 mutations, prevent the initiation of spermatid differentiation, resulting in male sterility (55). Phenotypic similarities between can and TAFII60 mutants suggest that TAFII60 is a component of an alternative TFIID complex that plays a role in male germ cell-specific gene expression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Henry Chang, Felix Karim, Marc Therrien, and Gerald Rubin for their assistance characterizing the TAFII60XS922 allele, Jim Kennison for generously providing the TAFII601, TAFII602, and TAFII603 alleles, Erin Schlag for assistance sequencing the TAFII60 alleles, Robert Tjian for providing TAFII60 antibody, Tom Burke and Jim Kadonaga for providing eTBP flies, and Sue Haynes for assistance analyzing the spermatogenesis defect. N. A. was supported by a fellowship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. This work was supported by the Intramural Program in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albright S R, Tjian R. TAFs revisited: more data reveal new twists and confirm old ideas. Gene. 2000;242:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00495-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoyagi N, Wassarman D A. Genes encoding Drosophila melanogaster RNA polymerase II general transcription factors: diversity in TFIIA and TFIID components contributes to gene-specific transcriptional regulation. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:F45–F49. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.2.f45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basler K, Siegrist R, Hafen E. The spatial and temporal expression pattern of sevenless is exclusively controlled by gene-internal elements. EMBO J. 1989;8:2381–2386. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08367.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basler K, Yen D, Tomlinson A, Hafen E. Reprogramming cell fate in the developing Drosophila retina: transformation of R7 cells by ectopic expression of Rough. Genes Dev. 1990;4:728–739. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.5.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell D, Tora L. Regulation of gene expression by multiple forms of TFIID and TAFII-containing complexes. Exp Cell Res. 1999;246:11–19. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowtell D D, Lila T, Michael W M, Hackett D, Rubin G M. Analysis of the enhancer element that controls expression of sevenless in the developing Drosophila eye. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6853–6857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke T W, Kadonaga J T. Drosophila TFIID binds to a conserved downstream basal promoter element that is present in many TATA-box-deficient promoters. Genes Dev. 1996;10:711–724. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.6.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke T W, Kadonaga J T. The downstream core promoter element, DPE, is conserved from Drosophila to humans and is recognized by TAFII60 of Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3020–3031. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang H C, Solomon N M, Wassarman D A, Karim F D, Therrien M, Rubin G M. phyllopod functions in the fate determination of a subset of photoreceptors in Drosophila. Cell. 1995;80:463–472. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90497-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dearolf C R. Fruit fly “leukemia.”. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1377:M13–M23. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(97)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dikstein R, Zhou S, Tjian R. Human TAFII105 is a cell type-specific TFIID subunit related to hTAFII130. Cell. 1996;87:137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dynlacht B D, Hoey T, Tjian R. Isolation of coactivators associated with the TATA-binding protein that mediate transcriptional activation. Cell. 1991;55:563–576. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Endo K, Akiyama T, Kobayashi S, Okada M. degenerative spermatocyte, a novel gene encoding a transmembrane protein required for the initiation of meiosis in Drosophila spermatogenesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;253:157–165. doi: 10.1007/s004380050308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farmer G, Colgan J, Nakatani Y, Manley J L, Prives C. Functional interaction between p53: the TATA-binding protein (TBP) and TBP-associated factors in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4295–4304. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flybase Consortium. Flybase: a Drosophila database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:85–88. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fortini M E, Simon M A, Rubin G M. Signaling by the Sevenless protein tyrosine kinase is mimicked by Ras1 activation. Nature. 1992;355:559–561. doi: 10.1038/355559a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fortini M E, Rubin G M. Analysis of cis-acting requirements of the Rh3 and Rh4 genes reveals a bipartite organization to rhodopsin promoters in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 1990;4:444–463. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.3.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuller M T. Genetic control of cell proliferation and differentiation in Drosophila spermatogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9:433–444. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1998.0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gatti M, Pimpinelli S. Functional elements in Drosophila melanogaster heterochromatin. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:239–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.001323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grant P A, Schieltz D, Pray-Grant M G, Steger D J, Reese J C, Yates III J R, Workman J L. A subset of TAF(II)s are integral components of the SAGA complex required for nucleosome acetylation and transcriptional stimulation. Cell. 1998;94:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guermah M, Malik S, Roeder R G. Involvement of TFIID and USA components in transcriptional activation of the human immunodeficiency virus promoter by NF-κB and Sp1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3224–3244. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hampsey M. Molecular genetics of the RNA polymerase II general transcription machinery. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:465–503. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.465-503.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiller M A, Lin T-Y, Wood C, Fuller M T. Developmental regulation of transcription by a tissue-specific TAF homolog. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1021–1030. doi: 10.1101/gad.869101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hou X S, Chou T B, Melnick M B, Perrimon N. The Torso receptor tyrosine kinase can activate Raf in a Ras-independent pathway. Cell. 1995;81:63–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karim F D, Chang H C, Therrien M, Wassarman D A, Laverty T, Rubin G M. A screen for genes that function downstream of Ras1 during Drosophila eye development. Genetics. 1996;143:315–327. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.1.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kemphues K J, Kaufman T C, Raff R A, Raff E C. The testis-specific β-tubulin subunit in Drosophila melanogaster has multiple functions in spermatogenesis. Cell. 1982;31:655–670. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimmel B E, Heberlein U, Rubin G M. The homeodomain protein Rough is expressed in a subset of cells in the developing Drosophila eye where it can specify photoreceptor subtype. Genes Dev. 1990;4:712–727. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.5.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kutach A K, Kadonaga J T. The downstream promoter element DPE appears to be as widely used as the TATA box in Drosophila core promoters. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4754–4764. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.13.4754-4764.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucchesi J C. Dosage compensation in Drosophila and the ‘complex’ world of transcriptional regulation. Bioessays. 1996;18:541–547. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maixner A, Hecker T P, Phan Q N, Wassarman D A. A screen for mutations that prevent lethality caused by expression of activated Sevenless and Ras1 in the Drosophila embryo. Dev Genet. 1998;23:347–361. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1998)23:4<347::AID-DVG9>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mengus G, May M, Carre L, Chambon P, Davidson I. Human TAFII135 potentiates transcriptional activation by the AF-2s of the retinoic acid, vitamin D3, and thyroid hormone receptors in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1381–1395. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.11.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michel B, Komarnitsky P, Buratowski S. Histone-like TAFs are essential for transcription in vivo. Mol Cell. 1998;2:663–673. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neufeld T P, de la Cruz A F, Johnston L A, Edgar B A. Coordination of growth and cell division in the Drosophila wing. Cell. 1998;93:1183–2001. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neuman-Silberberg F S, Schupbach T. The Drosophila TGF-alpha-like protein Gurken: expression and cellular localization during Drosophila oogenesis. Mech Dev. 1996;59:105–113. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ogrzyko V V, Kotani T, Zhang X, Schlitz R L, Howard T, Yang X-J, Howard B H, Qin J, Nakatani Y. Histone-like TAFs within the PCAF histone acetylase complex. Cell. 1998;94:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orphanides G, Lagrange T, Reinberg D. The general transcription factors of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2657–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pham A-D, Muller S, Sauer F. Mesoderm-determining transcription in Drosophila is alleviated by mutations in TAFII60 and TAFII110. Mech Dev. 1999;84:3–16. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rebay I, Chen F, Hsiao F, Kolodziej P A, Kuang B H, Laverty T, Suh C, Voas M, Williams A, Rubin G M. A genetic screen for novel components of the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway that interact with the yan gene of Drosophila identifies split ends, a new RNA recognition motif-containing protein. Genetics. 2000;154:695–712. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.2.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Royzman I, Whittaker A J, Orr-Weaver T L. Mutations in Drosophila DP and E2F distinguish G1-S progression from an associated transcriptional program. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1999–2011. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.15.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubin G M, Spradling A C. Genetic transformation of Drosophila with transposable element vectors. Science. 1982;218:348–353. doi: 10.1126/science.6289436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santel A, Kaufmann J, Hyland R, Renkawitz-Pohl R. The initiator element of the Drosophila β2 tubulin gene core promoter contributes to gene expression in vivo but is not required for male germ-cell specific expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1439–1446. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.6.1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sauer F, Hansen S K, Tjian R. DNA template and activator-coactivator requirements for transcriptional synergism by Drosophila Bicoid. Science. 1995;270:1825–1828. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schlag E M, Wassarman D A. Identifying mutations in Drosophila genes by direct sequencing of PCR products. BioTechniques. 1999;27:262–263. doi: 10.2144/99272bm09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt A, Palumbo G, Bozzetti M P, Tritto P, Pimpinelli S, Schafer U. Genetic and molecular characterization of sting, a gene involved in crystal formation and meiotic drive in the male germ line of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1999;151:749–760. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.2.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soldatov A, Nabirochkina E, Georgieva S, Belenkaja T, Georgiev P. TAFII40 protein is encoded by the e(y)1 gene: biological consequences of mutations. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3769–3778. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stewart M J, Denell R. Mutations in the Drosophila gene encoding ribosomal protein S6 causes tissue overgrowth. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2524–2535. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thut C J, Chen J-L, Klemm R, Tjian R. p53 transcriptional activation mediated by coactivators TAFII40 and TAFII60. Science. 1995;267:100–104. doi: 10.1126/science.7809597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomlinson A, Kimmel B E, Rubin G M. rough, a Drosophila homeobox gene required in photoreceptors R2 and R5 for inductive interactions in the developing eye. Cell. 1988;55:771–784. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomlinson A, Ready D F. Cell fate in the Drosophila ommatidium. Dev Biol. 1987;123:264–275. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Török I, Herrmann-Horle D, Kiss I, Tick G, Speer G, Schmitt R, Mechler B M. Down-regulation of RpS21, a putative translation initiation factor interacting with P40, produces viable minute imagos and larval lethality with overgrown hematopoietic organs and imaginal discs. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2308–2321. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Buskirk C, Schupbach T. Versatility in signaling: multiple responses to EGF receptor activation during Drosophila oogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verheyen E M, Purcell K J, Fortini M E, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Analysis of dominant enhancers and suppressors of activated Notch in Drosophila. Genetics. 1996;144:1127–1141. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.3.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wassarman D A, Aoyagi N, Pile L A, Schlag E M. TAF250 is required for multiple developmental events in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1154–1159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weinzierl R O J, Ruppert S, Dynlacht B D, Tanese N, Tjian R. Cloning and expression of Drosophila TAFII60 and human TAFII70 reveal conserved interactions with other subunits of TFIID. EMBO J. 1993;12:5303–5309. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.White-Cooper H, Schafer M A, Alphey L S, Fuller M T. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional control mechanisms coordinate the onset of spermatid differentiation with meiosis I in Drosophila. Development. 1996;125:125–134. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolff T, Ready D F. Pattern formation in the Drosophila retinae. In: Bate M, Martinez A, editors. The development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1993. pp. 1277–1325. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xie X, Kokubo T, Cohen S L, Mizra U A, Hoffmann A, Chait B T, Roeder R G, Nakatani Y, Burley S K. Structural similarity between TAFs and the heterotetrameric core of the histone octamer. Nature. 1996;380:316–322. doi: 10.1038/380316a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu T, Rubin G M. Analysis of genetic mosiacs in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development. 1993;117:1223–1237. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yue L, Karr T L, Nathan D F, Swift H, Srinivasan S, Lindquist S. Genetic analysis of viable Hsp90 alleles reveals a critical role in Drosophila spermatogenesis. Genetics. 1999;151:1065–1079. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.3.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou J, Zwicker J, Szymanski P, Levine M, Tjian R. TAFII mutations disrupt Dorsal activation in the Drosophila embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13483–13488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]