Five new 4-(arylvinyl)-2-styrylquinolines have been synthesized using indium chloride-catalyzed condensation reactions between their 4-(arylvinyl)-2-methyl- analogues and either mono- or diketones. The supramolecular arrangements range from isolated molecules via hydrogen-bonded dimers and sheets to three-dimensional framework structures.

Keywords: heterocyclic compounds, synthesis, quinolines, styrylquinolines, NMR spectroscopy, crystal structure, molecular conformation, hydrogen bonding, supramolecular assembly, privilaged scaffold

Abstract

Four new 2,4-distyrylquinolines and one 2-styryl-4-[2-(thiophen-2-yl)vinyl]quinoline have been synthesized using indium trichloride condensation reactions between aromatic aldehydes and the corresponding 2-methylquinolines, which were themselves prepared using Friedländer annulation reactions between mono- or diketones and (2-aminophenyl)chalcones: the products have all been fully characterized by spectroscopic and crystallographic methods. 2,4-Bis[(E)-styryl]quinoline, C25H19N, (IIa), and its dichloro analogue, 2-[(E)-2,4-dichlorostyryl]-4-[(E)-styryl]quinoline, C25H17Cl2N, (IIb), exhibit different orientations of the 2-styryl unit relative to the quinoline nucleus. In each of the 3-benzoyl analogues {2-[(E)-4-bromostyryl]-4-[(E)-styryl]quinolin-3-yl}(phenyl)methanone, C32H22BrNO, (IIc), {2-[(E)-4-bromostyryl]-4-[(E)-4-chlorostyryl]quinolin-3-yl}(phenyl)methanone, C32H21BrClNO, (IId), and {2-[(E)-4-bromostyryl]-4-[(E)-2-(thiophen-2-yl)vinyl]quinolin-3-yl}(phenyl)methanone, C30H20BrNOS, (IIe), the orientation of the 2-styryl unit is similar to that in (IIa), but the orientation of the 4-arylvinyl units show considerable variation. The thiophene unit in (IIe) is disordered over two sets of atomic sites having occupancies of 0.926 (3) and 0.074 (3). There are no hydrogen bonds of any kind in the structure of (IIa), but in (IId), a single C—H⋯O hydrogen bond links the molecules into cyclic centrosymmetric R 2 2(20) dimers. A combination of C—H⋯N and C—H⋯π hydrogen bonds links the molecules of (IIb) into a three-dimensional framework structure. A combination of three C—H⋯π hydrogen bonds links the molecules of (IIc) into sheets, and a combination of C—H⋯O and C—H⋯π hydrogen bonds forms sheets in (IIe). Comparisons are made with the structures of some related compounds.

Introduction

The quinoline nucleus is considered to be one of the most privileged scaffolds and to be a crucial pharmacophore in drug discovery because of its occurrence in a wide variety of natural and synthetic biologically active molecules (Solomon & Lee, 2011 ▸; Musiol et al., 2017 ▸; Matada et al., 2021 ▸). The outstanding therapeutic importance of quinoline derivatives is well known, particularly in the treatment of, for example, microbial (Lam et al., 2014 ▸; Zhang et al., 2018 ▸), malarial (Kaur et al., 2010 ▸; Hu et al., 2017 ▸; Okombo & Chibale, 2018 ▸; Orozco et al., 2020 ▸), fungal (Musiol et al., 2010 ▸; Kumar et al., 2011 ▸), inflammatory (Chen et al., 2006 ▸; Gilbert et al., 2008 ▸), viral (Ghosh et al., 2008 ▸; Matada et al., 2021 ▸), protozoal (Fakhfakh et al., 2003 ▸; Franck et al., 2004 ▸; Kumar et al., 2009 ▸), cardiovascular (Cai et al., 2007 ▸; Bernotas et al., 2009 ▸) and neoplastic diseases (Afzal et al., 2015 ▸; Musiol, 2017 ▸; Cortes et al., 2018 ▸; Lauria et al., 2021 ▸; Yadav & Kamal, 2021 ▸).

Among different classes of quinoline derivatives, styrylquinolines, especially 2-styrylquinolines and to a lesser extent 4-styrylquinolines, have been studied extensively, mainly because of their potential as inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase (Leonard & Roy, 2008 ▸; Mahajan et al., 2018 ▸; Mousnier et al., 2004 ▸) and as antimicrobial (Kamal et al., 2015 ▸), antifungal (Cieslik et al., 2012 ▸; Szczepaniak et al., 2017 ▸), anti-asthma (Matada et al., 2021 ▸) and anticancer agents (Chang et al., 2010 ▸; Mrozek-Wilczkiewicz et al., 2015 ▸, 2019 ▸). The pharmacological

relevance of these types of quinoline derivatives has prompted the development of different methodologies for the synthesis of drug-like compounds containing such styrylquinoline scaffolds (Staderine et al., 2011 ▸; Yaragorla et al., 2015 ▸; Sharma et al., 2017 ▸; Musiol, 2020 ▸; Hazra et al., 2020 ▸; Zhang et al., 2020 ▸; Li et al., 2021 ▸; Omar & Hormi, 2009 ▸; Lee et al., 2009 ▸ Alacíd & Nájera, 2009 ▸; Jamal & Teo, 2014 ▸; Jamal et al., 2016 ▸; Satish et al., 2019 ▸; Meléndez et al., 2020 ▸).

relevance of these types of quinoline derivatives has prompted the development of different methodologies for the synthesis of drug-like compounds containing such styrylquinoline scaffolds (Staderine et al., 2011 ▸; Yaragorla et al., 2015 ▸; Sharma et al., 2017 ▸; Musiol, 2020 ▸; Hazra et al., 2020 ▸; Zhang et al., 2020 ▸; Li et al., 2021 ▸; Omar & Hormi, 2009 ▸; Lee et al., 2009 ▸ Alacíd & Nájera, 2009 ▸; Jamal & Teo, 2014 ▸; Jamal et al., 2016 ▸; Satish et al., 2019 ▸; Meléndez et al., 2020 ▸).

Unlike 2-styryl- and 4-styrylquinolines, the closely-related 2,4-distyrylquinolines have been scarcely investigated, with very few publications related to their synthesis and biological evaluation, and this scarcity may be due, at least in part, to the lack of satisfactory methods for their synthesis. The few reported 2,4-distyrylquinolines have been prepared by methods such as one-pot successive Arbuzov/Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons reactions using ethyl 4-(bromomethyl)-2-(chloromethyl)quinoline-3-carboxylate as the key precursor (Gao et al., 2018 ▸), and the Knoevenagel-type condensation of 2-methyl-4-styrylquinoline with aromatic aldehydes, catalysed by sodium acetate (Satish et al., 2019 ▸).

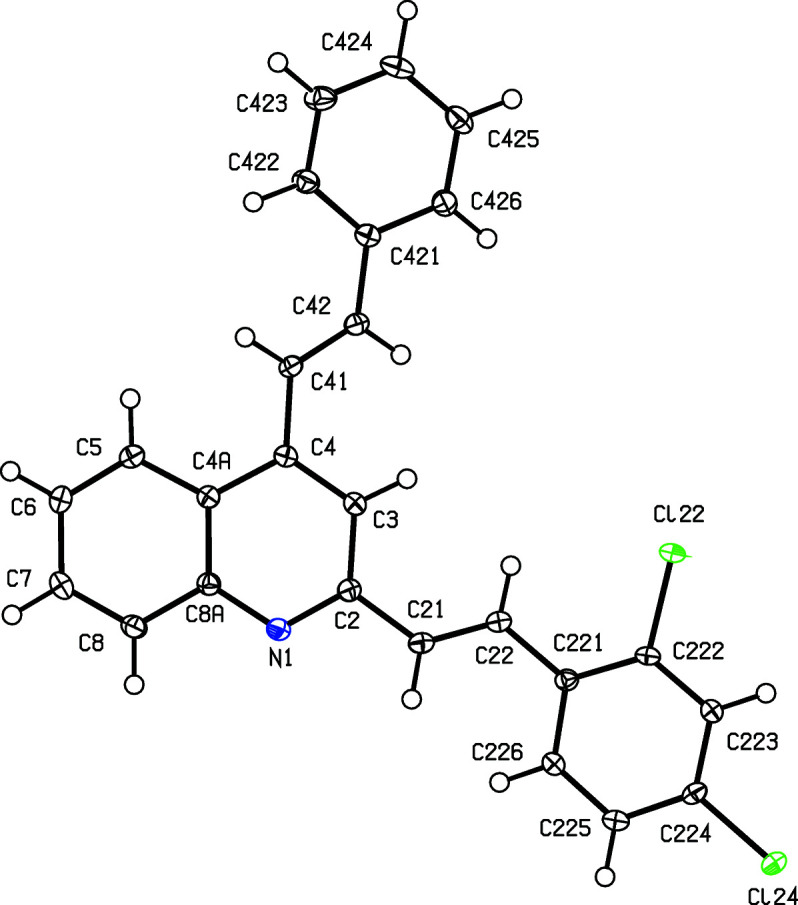

We have recently described an efficient and straightforward synthetic pathway, based on Friedländer annulation and starting from readily available 1-(2-aminophenyl)-3-arylprop-2-en-1-ones, to obtain several new series of polysubstituted 2-methyl-4-styrylquinolines (Meléndez et al., 2020 ▸; Vera et al., 2022 ▸). In an expansion of the scope of this route, in respect of both utility and flexibility, we now describe the synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, and molecular and supramolecular structures of a matched set of five closely-related 2,4-distyrylquinolines, namely, 2,4-bis[(E)-styryl]quinoline, (IIa), 2-[(E)-2,4-dichlorostyryl]-4-[(E)-styryl]quinoline, (IIb), {2-[(E)-4-bromostyryl]-4-[(E)-styryl]quinolin-3-yl}(phenyl)methanone, (IIc), {2-[(E)-4-bromostyryl]-4-[(E)-4-chlorostyryl]quinolin-3-yl}(phenyl)methanone, (IId), and {2-[(E)-4-bromostyryl]-4-[(E)-2-(thiophen-2-yl)vinyl]quinolin-3-yl}(phenyl)methanone, (IIe) (see Scheme 1), which differ only in the nature of the substituents at position C3 of the quinoline ring and the substituents in the 4-(arylvinyl) fragments. To the best of our knowledge, these 2,4-distyrylquinolines have not been reported previously.

The work reported here can be regarded as a continuation of an earlier crystallographic study which reported the structures of 4-styrylquinolines having different substituents at the C2 and C3 positions (Rodríguez et al., 2020 ▸; Vera et al., 2022 ▸; Ardila et al., 2022 ▸).

Experimental

Synthesis and crystallization

For the synthesis of compounds (IIa)–(IIe), a mixture of the appropriate 2-methyl-4-styrylquinoline, (I) (see Scheme 1), prepared as described previously (Meléndez et al., 2020 ▸; Vera et al., 2022 ▸) (1.0 mmol), the appropriate aromatic aldehyde (4.0 mmol) and indium trichloride (10 mmol%) in dry toluene (1.2 ml) was stirred magnetically and heated at 393 K until the reactions were complete, shown by the complete consumption of (I), as monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). The reaction times for completion were 18 h for (IIa), 16 h for (IIb), 17 h for (IIc) and 21 h for both (IId) and (IIe). Each reaction mixture was then allowed to cool to ambient temperature, washed with chloroform and the resulting suspension was removed by filtration before the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. In each case, the resulting crude product was purified by silica-gel column chromatography using heptane–ethyl acetate mixtures as eluent (compositions ranged from 10:1 to 2:1 v/v) to give the required solid products (IIa)–(IIe). Crystallization from ethyl acetate–heptane, at ambient temperature and in the presence of air, gave crystals suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

In the NMR data listed below, unprimed ring atoms form part of the quinoline units; ring atoms carrying a single prime form part of the styryl units attached at position C2 of the quinoline system; ring atoms carrying double primes form part of the styryl units attached at position C4 for compounds (IIa) and (IIb), or part of the benzoyl units attached at position C3 for compounds (IIc)–(IIe); and ring atoms carrying triple primes form part of the styryl units attached at position C4 for compounds (IIc)–(IIe).

2,4-Bis[(E)-styryl]quinoline, (IIa). Yellow solid, yield 0.11 g (71%), m.p. 393–394 K, R F = 0.40 (21% ethyl acetate–heptane). IR (ATR, cm−1): 3019 [C(sp 2)H], 1723 (C=N), 1633 (C=Cvinyl), 1581 (C=Carom), 1541 (C=Carom), 961 (=C—H trans ). NMR (CDCl3): δ(1H) (400 MHz) 8.15 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, H5), 8.12 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H8), 7.84 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H, H3), 7.81 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H, HA′′C=), 7.76 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H, =CHB′), 7.72–7.68 (m, 1H, H7), 7.68–7.65 (m, 4H, H2′, H6′, H2′′, H6′′), 7.53 (ddt, J = 8.2, 6.9, 1.3 Hz, 1H, H6), 7.47–7.43 (m, 1H, HA′C=), 7.46–7.41 (m, 4H, H3′, H5′, H3′′, H5′′), 7.40–7.32 (m, 2H, H4′, H4′′), 7.38–7.34 (m, 1H, =CHB′′); δ(13C) (100 MHz) 155.7 (C2), 148.8 (C8a), 143.3 (C4), 136.7 (C1′′), 136.6 (C1′), 135.0 (=CHB′′), 134.3 (=CHB′), 129.9 (C8), 129.6 (C7), 128.9 (C3′′, C5′′), 128.8 (C3′, C5′, C4′′, HA′C=), 128.6 (C4′), 127.3 (C2′′, C6′′), 127.2 (C2′, C6′), 126.2 (C6), 125.7 (C4a), 123.4 (C5, HA′—C=), 115.6 (C3). HRMS (ESI+) m/z found for [M + H]+ 334.1590, C25H19N requires 333.1589.

2-[(E)-2,4-Dichlorostyryl]-4-[(E)-styryl]quinoline, (IIb). Yellow solid, yield 0.19 g (77%), m.p. 449–450 K, R F = 0.41 (21% ethyl acetate–heptane). IR (ATR, cm−1): 3055 [C(sp 2)H], 1639 (C=N), 1580 (C=Cvinyl), 1541 (C=Carom), 1473 (C=Carom), 960 (=C—H trans ). NMR (CDCl3): δ(1H) (400 MHz) 8.17 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.5 Hz, 1H, 5H), 8.11 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.3 Hz, 1H, 8H), 8.03 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H, =CHB′), 7.86 (s, 1H, 3H), 7.81 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1 H, HA′′C=), 7.75 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H6′), 7.73 (ddd, J = 8.4, 6.9, 1.4 Hz, 1H, H7), 7.67–7.64 (m, 2H, H2′′, H6′′), 7.56 (ddd, J = 8.3, 6.8, 1.3 Hz, 1H, H6), 7.47–7.42 (m, 3H, H3′, H3′′, H5′′), 7.39 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H, =CHB′′), 7.39–7.35 (m, 1H, H4′′), 7.38 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H, HA′C=), 7.29 (dd, J = 8.2, 2.0 Hz, 1H, H5′); δ(13C) (100 MHz) 155.1 (C2), 148.8 (C8a), 143.5 (C4), 136.6 (C1′′), 135.3 (=CHB′′), 134.6 (C2′), 134.5 (C4′), 133.4 (C1′), 132.3 (HA′C=), 130.1 (C8), 129.8 (C7, C3′), 129.0 (C3′′, C5′′), 128.9 (=CHB′), 128.8 (C4′′), 127.7 (C6′), 127.5 (C5′), 127.2 (C2′′, C6′′), 126.5 (C6), 125.8 (C4a), 123.5 (C5), 123.2 (HA′′C=), 115.4 (C3). HRMS (ESI+) m/z found for [M + H]+ 402.0812, C25H17 35Cl2N requires 402.0811.

{2-[(E)-4-Bromostyryl]-4-[(E)-styryl]quinolin-3-yl}(phenyl)methanone, (IIc). Orange solid. yield 0.20 g (86%), m.p. 471–472 K, R F = 0.38 (9.1% ethyl acetate–heptane). IR (ATR, cm−1): 3025 [C(sp 2)H], 1666 (C=O), 1627 (C=N), 1595 (C=Cvinyl), 1535 (C=Carom), 1483 (C=Carom), 957 (=C—H trans ). NMR (CDCl3): δ(1H) (400 MHz) 8.20 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.2 Hz, 1H, H8), 8.12 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.4 Hz, 1H, H5), 8.00 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H, =CHB′), 7.80 (ddd, J = 8.6, 6.9, 1.3 Hz 1H, H7), 7.78–7.76 (m, 2H, H2′′, H6′′), 7.57 (ddd, J = 8.3, 6.9, 1.2 Hz, 1H, H6), 7.56–7.52 (m, 1H, H4′′), 7.44–7.42 (m, 2H, H3′, H5′), 7.39 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, H3′′, H5′′), 7.35–7.32 (m, 2H, H2′, H6′), 7.30–7.26 (m, 5H, H2′′′, H6′′′, H3′′′, H5′′′, H4′′′), 7.23 (dd, J = 16.4, 0.8 Hz, 1H, HA′′′C=), 7.09 (dd, J = 15.5, 0.8 Hz, 1H, Ha′C=), 6.87 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H, =CHB′′′); δ(13C) (100 MHz) 198.4 (C=O), 151.4 (C2), 148.1 (C8a), 142.4 (C4), 139.5 (=CHB′′′), 137.9 (C1′′), 136.3 (C1′′′), 135.4 (C1′), 135.0 (=CHB′), 134.0 (C4′′), 131.8 (C3′, C5′), 131.1 (C3), 130.6 (C7), 130.0 (C8), 129.5 (C2′′, C6′′), 129.0 (C2′, C6′), 128.9 (C3′′, C5′′), 128.8 (C4′′′), 128.7 (C3′′′, C5′′′), 126.9 (C6), 126.8 (C2′′′, C6′′′), 125.4 (C4a), 125.2 (C5), 125.0 (HA′C=), 122.7 (C4′), 122.1 (HA′′C=). HRMS (ESI+) m/z found for [M + H]+ 516.09656, C32H22 79BrNO requires 516.09575.

{2-[(E)-4-Bromostyryl]-4-[(E)-4-chlorostyryl]quinolin-3-yl}(phenyl)methanone, (IId). Orange solid, yield 0.19 g (80%), m.p. 476–477 K, R F = 0.35 (9.1% ethyl acetate–heptane). IR (ATR, cm−1): 3046 [C(sp 2)H], 1661 (C=O), 1630 (C=N), 1590, 1595 (C=Cvinyl), 1540 (C=Carom), 1487 (C=Carom), 978 (=C—H trans ). NMR (CDCl3): δ(1H) 8.20 (400 MHz) (dd, J = 8.4, 1.4 Hz, 1H, H8), 8.08 (ddd, J = 8.4, 1.4, 0.7 Hz, 1H, H5), 8.00 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H, =CHB′), 7.80 (ddd, J = 8.4, 6.8, 1.3 Hz, 1H, H7), 7.76–7.74 (m, 2H, H2′′, H6′′), 7.57 (ddd, J = 8.3, 6.8, 1.3 Hz, 1H, H6), 7.56–7.52 (m, 1H, H4′′), 7.44–7.42 (m, 2H, H3′, H5′), 7.39 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, H3′′, H5′′), 7.34–7.31 (m, 2H, H2′, H6′), 7.27–7.25 (m, 2H, H3′′′, H5′′′), 7.22–7.18 (m, 2H, H2′′′, H6′′′), 7.20 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H, HA′′′C=), 7.08 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H, HA′C=), 6.81 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H, =CHB′′′); δ(13C) (100 MHz) 198.4 (C=O), 151.4 (C2), 148.1 (C8a), 142.0 (C4), 138.1 (=CHB′′′), 137.9 (C1′′), 135.4 (C1′), 135.1 (=CHB′), 134.7 (C4′′′), 134.6 (C1′′′), 134.1 (C4′′), 131.8 (C3′, C5′), 131.1 (C3), 130.7 (C7), 130.0 (C8), 129.5 (C2′′, C6′′), 129.0 (C2′, C6′, C3′′′, C5′′′), 128.9 (C3′′, C5′′), 128.0 (C2′′′, C6′′′), 127.0 (C6), 125.2 (C4a), 125.1 (HHA′C=), 124.9 (C5), 122.7 (C4′, HA′′′C=). HRMS (ESI+) m/z found for [M + H]+ 550.05750, C32H21 79Br35ClNO requires 550.05678.

{2-[(E)-4-Bromostyryl]-4-[(E)-2-(thiophen-2-yl)vinyl]quinolin-3-yl}(phenyl)methanone, (IIe). Yellow solid, yield 0.24 g (93%), m.p. 472–473 K, R F = 0.38 (9.1% ethyl acetate–heptane). IR (ATR, cm−1): 3026 [C(sp 2)H], 1663 (C=O), 1627 (C=N), 1589 (C=Cvinyl), 1537 (C=Carom), 1483 (C=Carom), 957 (=C—H trans ). NMR (CDCl3): δ(1H) (400 MHz) 8.18 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, H8), 8.11 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, H5), 7.99 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H, =CHB′), 7.82–7.78 (m, 1H, H7), 7.77–7.75 (m, 2H, H2′′, H6′′), 7.58 (ddd, J = 8.3, 6.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H, H6), 7.56–7.52 (m, 1H, H4′′), 7.43 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, H3′, H5′), 7.38 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, H3′′, H5′′), 7.33 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, H2′, H6′), 7.21 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H, H3′′′), 7.08 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H, HA′C=), 7.08 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H, Ha′′′C=), 6.99 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H, =CHB′′′), 6.98–6.95 (m, 2H, H4′′′, H5′′′); δ(13C) (100 MHz) 198.5 (C=O), 151.4 (C2), 148.1 (C8a), 141.7 (C4), 141.3 (C2′′′), 137.8 (C1′′), 135.4 (C1′), 135.0 (=CHB′), 134.0 (C4′′), 132.3 (=CHB′′′), 131.8 (C3′, C5′), 130.9 (C3), 130.6 (C7), 130.0 (C8), 129.5 (C2′′, C6′′), 129.0 (C2′, C6′), 128.9 (C3′′, C5′′), 128.0 (C5′′′), 127.7 (C4′′′), 127.0 (C6), 126.1 (C3′′′), 125.2 (C4a), 125.1 (HA′C=), 124.9 (C5), 122.7 (C4′), 121.1 (HA′′′C=). HRMS (ESI+) m/z found for [M + H]+ 522.05249, C30H20 79BrNOS = requires 522.05217.

Refinement

Crystal data, data collection and refinement details for compounds (IIa)–(IIe) are summarized in Table 1 ▸. For compound (IId), the reflection 100, which had been attenuated by the beam stop, was removed from the data set. In addition, a small number of bad outlier reflections [

04 for (IIa) and 141, 231, 241, 033 and

04 for (IIa) and 141, 231, 241, 033 and

03 for (IIc)] were also removed. Compound (IIc) was handled as a nonmerohedral twin, with twin matrix (−0.053, 0.000, 0.947/0.000, −1.000, 0.000/1.053, 0.000, 0.053) and with refined twin fractions of 0.865 (2) and 0.135 (2). In compound (IIe), the thienyl unit was disordered over two sets of atomic sites having unequal occupancies. For the minor-disorder component, the bonded distances and the 1,3 nonbonded distances were restrained to be the same as the corresponding distances in the major-disorder component, subject to s.u. values of 0.01 and 0.02 Å, respectively. In addition, the anisotropic displacement parameters for pairs of partial-occupancy atoms occupying essentially the same physical space were constrained to be identical. All H atoms, apart from those in the minor-disorder component of compound (IIe), were located in difference maps and then treated as riding atoms in geometrically idealized positions, with C—H = 0.95 Å and U

iso(H) = 1.2U

eq(C); the H atoms in the minor-disorder component of compound (IIe) were included in the refinement in exactly the same manner. Subject to these conditions, the refined occupancy values for the disorder components of (IIe) were 0.926 (3) and 0.074 (3). In the final difference map, the largest maximum of 1.65 e Å−3 was 0.86 Å from atom Br24, while the largest minimum of −1.18 e Å−3 was 0.66 Å from Br24. While these features might indicate some further minor disorder, the anisotropic displacement parameters provided no support for this possibility, which was therefore not pursued further.

03 for (IIc)] were also removed. Compound (IIc) was handled as a nonmerohedral twin, with twin matrix (−0.053, 0.000, 0.947/0.000, −1.000, 0.000/1.053, 0.000, 0.053) and with refined twin fractions of 0.865 (2) and 0.135 (2). In compound (IIe), the thienyl unit was disordered over two sets of atomic sites having unequal occupancies. For the minor-disorder component, the bonded distances and the 1,3 nonbonded distances were restrained to be the same as the corresponding distances in the major-disorder component, subject to s.u. values of 0.01 and 0.02 Å, respectively. In addition, the anisotropic displacement parameters for pairs of partial-occupancy atoms occupying essentially the same physical space were constrained to be identical. All H atoms, apart from those in the minor-disorder component of compound (IIe), were located in difference maps and then treated as riding atoms in geometrically idealized positions, with C—H = 0.95 Å and U

iso(H) = 1.2U

eq(C); the H atoms in the minor-disorder component of compound (IIe) were included in the refinement in exactly the same manner. Subject to these conditions, the refined occupancy values for the disorder components of (IIe) were 0.926 (3) and 0.074 (3). In the final difference map, the largest maximum of 1.65 e Å−3 was 0.86 Å from atom Br24, while the largest minimum of −1.18 e Å−3 was 0.66 Å from Br24. While these features might indicate some further minor disorder, the anisotropic displacement parameters provided no support for this possibility, which was therefore not pursued further.

Table 1. Experimental details.

Experiments were carried out at 100 K with Mo Kα radiation using a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer. Absorption was corrected for by multi-scan methods (SADABS; Bruker, 2016 ▸). H-atom parameters were constrained.

| (IIa) | (IIb) | (IIc) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal data | |||

| Chemical formula | C25H19N | C25H17Cl2N | C32H22BrNO |

| M r | 333.41 | 402.29 | 516.41 |

| Crystal system, space group | Monoclinic, P21/c | Monoclinic, C2/c | Monoclinic, P21/n |

| a, b, c (Å) | 12.6112 (6), 8.6352 (4), 17.3080 (8) | 28.4950 (7), 9.5384 (3), 16.0520 (5) | 12.287 (2), 15.528 (3), 12.844 (3) |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 105.925 (2), 90 | 90, 118.581 (1), 90 | 90, 99.877 (6), 90 |

| V (Å3) | 1812.51 (15) | 3831.2 (2) | 2414.2 (8) |

| Z | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| μ (mm−1) | 0.07 | 0.35 | 1.73 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.19 × 0.14 × 0.08 | 0.21 × 0.10 × 0.09 | 0.15 × 0.12 × 0.08 |

| Data collection | |||

| T min, T max | 0.924, 0.994 | 0.901, 0.969 | 0.720, 0.871 |

| No. of measured, independent and observed [I > 2σ(I)] reflections | 38720, 4161, 3388 | 47555, 4414, 3914 | 5530, 5530, 4290 |

| R int | 0.060 | 0.056 | – |

| (sin θ/λ)max (Å−1) | 0.650 | 0.650 | 0.653 |

| Refinement | |||

| R[F 2 > 2σ(F 2)], wR(F 2), S | 0.050, 0.118, 1.09 | 0.032, 0.078, 1.09 | 0.064, 0.196, 1.05 |

| No. of reflections | 4161 | 4414 | 5530 |

| No. of parameters | 235 | 253 | 317 |

| No. of restraints | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e Å−3) | 0.25, −0.24 | 0.35, −0.22 | 1.40, −0.70 |

| (IId) | (IIe) | |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal data | ||

| Chemical formula | C32H21BrClNO | C30H20BrNOS |

| M r | 550.86 | 522.44 |

| Crystal system, space group | Triclinic, P

|

Orthorhombic, P b c a |

| a, b, c (Å) | 9.9051 (12), 11.3936 (16), 11.8192 (16) | 15.5785 (8), 16.4215 (7), 18.3126 (9) |

| α, β, γ (°) | 77.727 (5), 76.116 (5), 86.448 (5) | 90, 90, 90 |

| V (Å3) | 1265.2 (3) | 4684.8 (4) |

| Z | 2 | 8 |

| μ (mm−1) | 1.76 | 1.87 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.19 × 0.12 × 0.10 | 0.20 × 0.12 × 0.08 |

| Data collection | ||

| T min, T max | 0.735, 0.836 | 0.768, 0.861 |

| No. of measured, independent and observed [I > 2σ(I)] reflections | 61838, 5807, 5014 | 63672, 5363, 4456 |

| R int | 0.064 | 0.060 |

| (sin θ/λ)max (Å−1) | 0.650 | 0.649 |

| Refinement | ||

| R[F 2 > 2σ(F 2)], wR(F 2), S | 0.028, 0.065, 1.03 | 0.040, 0.101, 1.02 |

| No. of reflections | 5807 | 5363 |

| No. of parameters | 325 | 320 |

| No. of restraints | 0 | 10 |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e Å−3) | 0.33, −0.39 | 1.65, −1.18 |

Results and discussion

The 2-methyl-4-styrylquinoline precursors of type (I) (see Scheme 1) were prepared in high yields using Friedländer annulation reactions (Meléndez et al., 2020 ▸; Vera et al., 2022 ▸) between (2-aminophenyl)chalcones and either acetone, for compounds (Ia) and (Ib), or 1-phenylbutane-l-1,3-dione, for compounds (Ic)–(Ie). These precursors of type (I) were then converted successfully into the target 2,4-distyrylquinolines (IIa)–(IIe) in yields of 71–93% by means of indium trichloride-catalyzed Knoevenagel-type condensation reactions with the appropriate aromatic aldehydes (see Scheme 1). Compounds (IIa)–(IIe) were all fully characterized by standard spectroscopic means (FT–IR, 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, and high-resolution mass spectrometry) and full details of the spectroscopic characterization are provided in Section 2.1.

The formation of the second styryl fragment in products (IIa)–(IIe) was established by the disappearance from both the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of the signals from the methyl group at position C2, and their replacement by new sets of signals corresponding to the newly-introduced C and H atoms; thus, eight new C atoms in each case and seven new H atoms in (IIa), five in (IIb) and six in each of (IIc)–(IIe). In each case, the Knoevenagel-type condensation proceeded in a highly stereoselective manner giving exclusively the E stereoisomers, as indicated by the 1H NMR spectra. The E configuration of the newly-formed styryl fragment was deduced on the basis of the coupling constant values (3 J HA′,HB′ ca 16.0 Hz) between HA′ and HB′. The constitutions of compounds (IIa)–(IIe), which were deduced from the spectroscopic data, were then fully confirmed by the results of single-crystal X-ray diffraction, which additionally provided information on the molecular conformations and the intermolecular interactions in the solid state.

The versatility of this synthetic route to 2,4-distyrylquinolines and their analogues is underpinned by the possibility of incorporating a wide variety of substituents into the initial chalcone precursor, into the ketone employed in the annulation step and into the aldehyde used in the final condensation step.

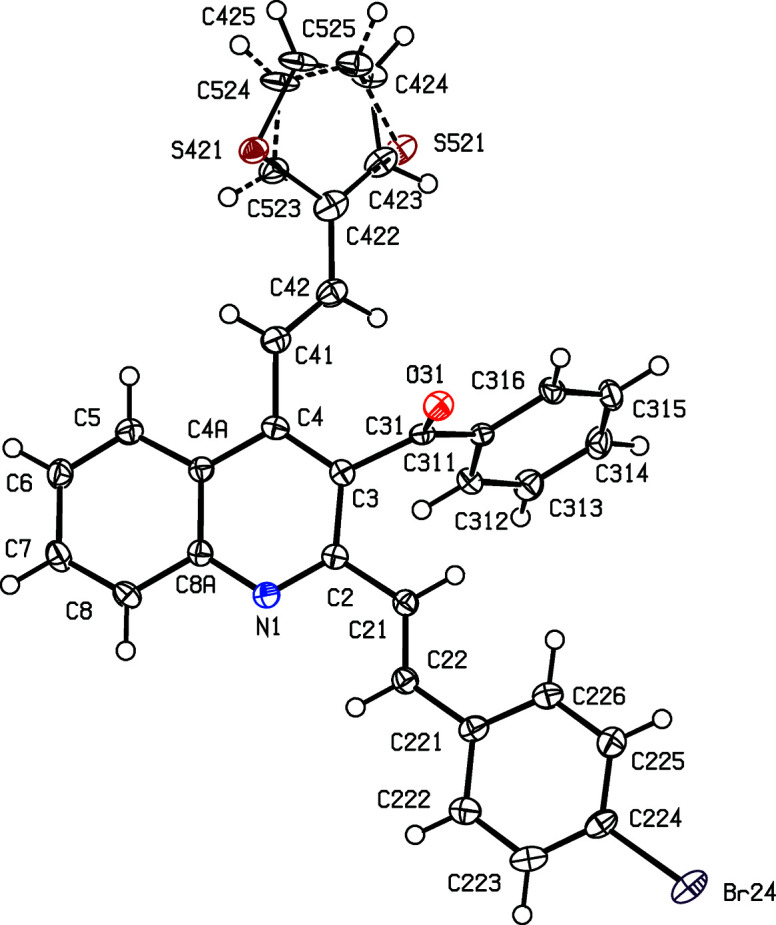

In compound (IIe), the thiophene unit is disordered over two sets of atomic sites having occupancies of 0.926 (3) and 0.074 (3), such that the two disorder forms are related by a rotation of approximately 180° around the exocyclic C—C bond; the dihedral angle between the mean planes of the two disorder components is only 4(2)°.

The molecules of compounds (IIa)–(IIe) exhibit no internal symmetry and hence these compounds are all conformationally chiral (Moss, 1996 ▸; Flack & Bernardinelli, 1999 ▸), but the centrosymmetric space groups (Table 1 ▸) confirm that equal numbers of the two conformational enantiomers are present in each of (IIa)–(IIe).

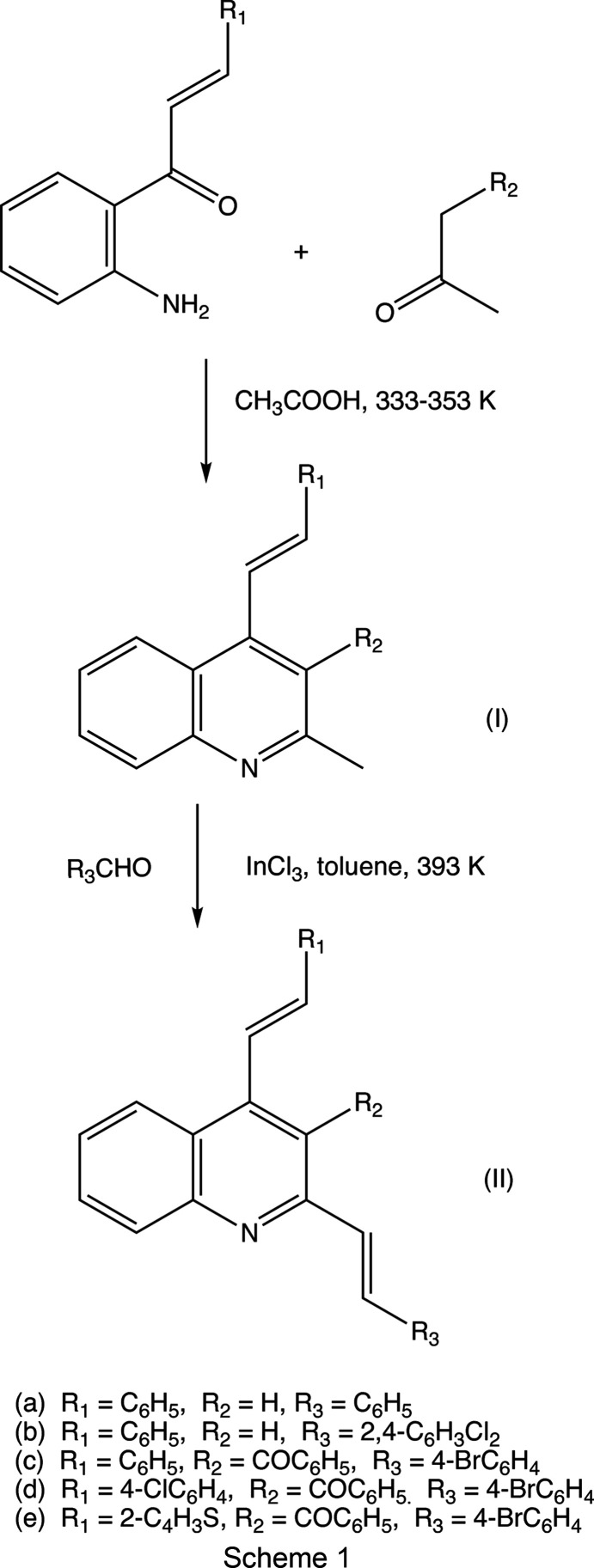

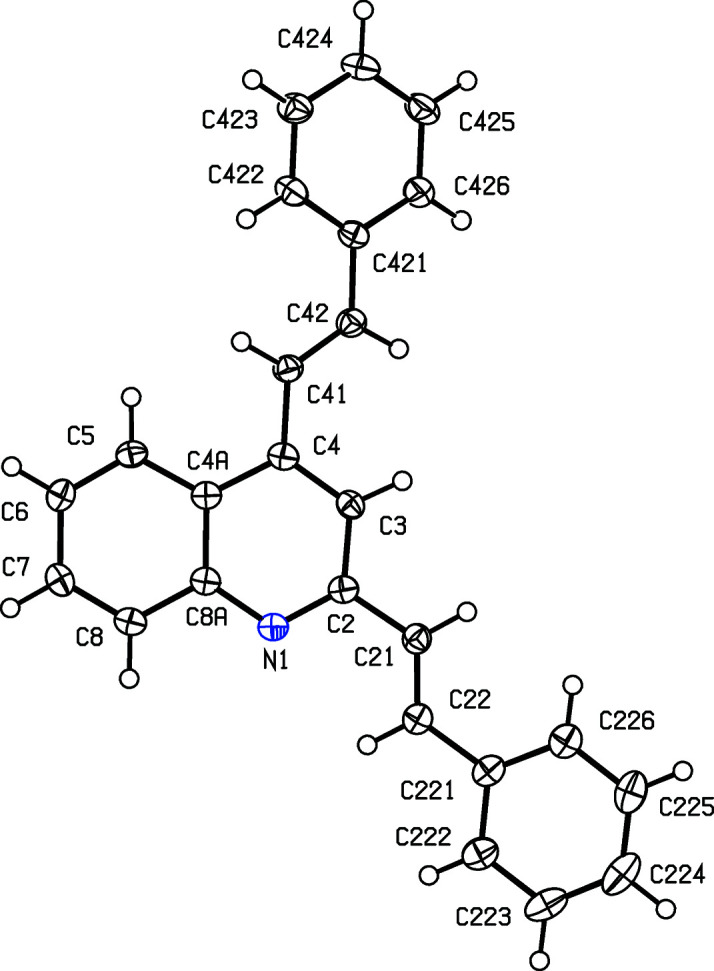

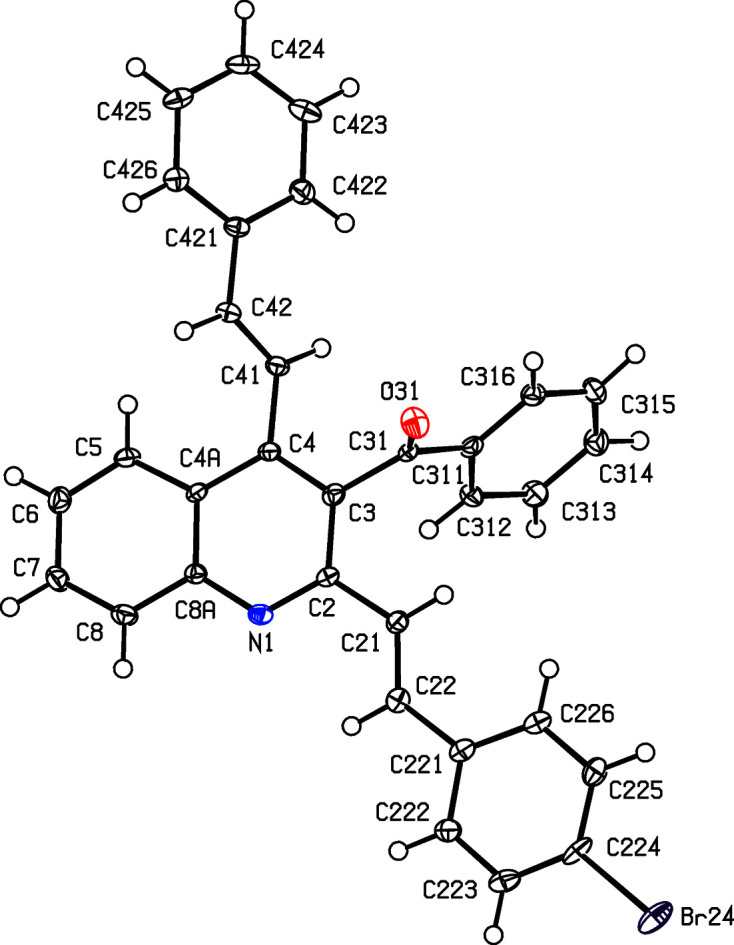

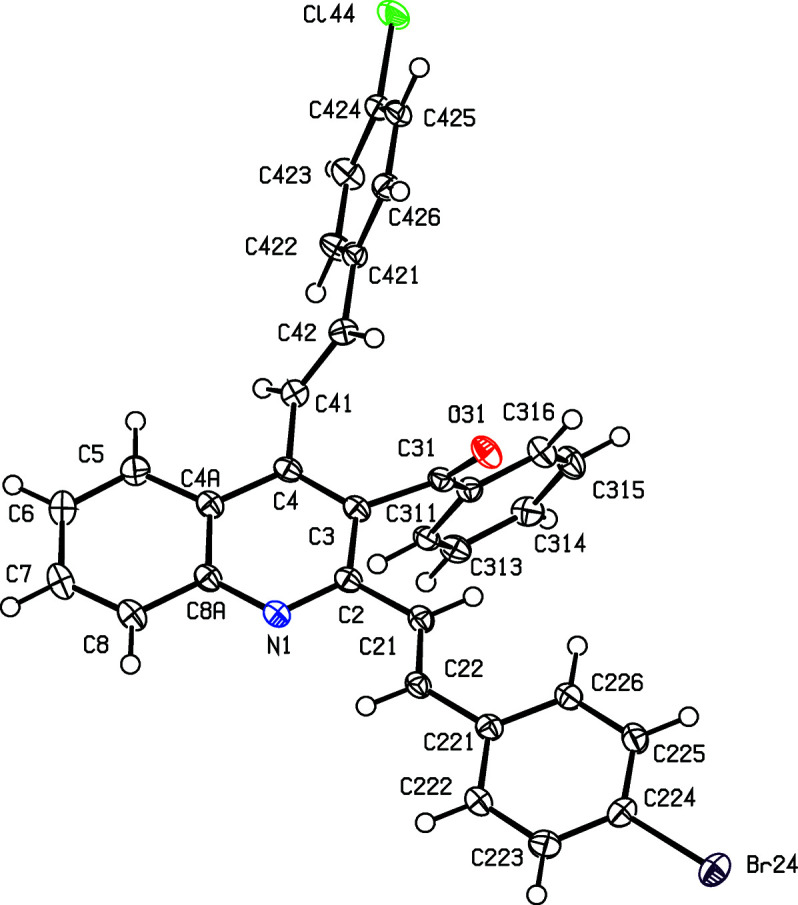

For the 3-benzoyl products (IIc)–(IIe), the reference molecules are all such that the torsion angle C2—C3—C31—C311 has a positive sign (Table 2 ▸), while the value of the torsion angle C3—C4—C41—C42 in (IIc) is markedly different from those in the other four compound reported here (Table 2 ▸ and Figs. 1 ▸–5 ▸ ▸ ▸ ▸). In each of (IIa)–(IIe), the 2-styryl unit is close to being coplanar with the quinoline unit, while the 4-substituent is twisted well out of the plane of the quinoline unit. These observations thus complement the general pattern in styrylquinolines that we have noted previously (Vera et al., 2022 ▸; Ardila et al., 2022 ▸). Amongst the styrylquinolines whose structures are recorded in the Cambridge Structural Database (Groom et al., 2016 ▸), 2-styryl- and 8-styrylquinolines all have molecular skeletons which are effectively planar, while in 4-styrylquinolines, the styryl unit is always markedly twisted out of the plane of the quinoline unit by a rotation about the exocyclic bond corresponding to C4—C41 in the numbering system used here.

Table 2. Selected torsion angles (°) for compounds (IIa)–(IIe).

| Parameter | (IIa) | (IIb) | (IIc) | (IId) | (IIe) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C3—C2—C21—C22 | −178.77 (14) | −12.9 (2) | −171.8 (4) | 179.16 (16) | 178.5 (2) |

| C21—C22—C221—C222 | −173.99 (15) | −161.58 (14) | 171.4 (4) | −171.95 (17) | −174.5 (3) |

| C2—C3—C31—C311 | 87.2 (5) | 109.43 (17) | 85.9 (3) | ||

| C3—C31—C311—C312 | −15.6 (6) | −12.3 (2) | −10.9 (3) | ||

| C3—C4—C41—C42 | 19.8 (2) | 23.4 (2) | −131.9 (4) | −44.4 (2) | 37.6 (4) |

| C41—C42—C421—C422 | 8.3 (2) | −6.1 (2) | −4.5 (6) | −21.4 (3) | |

| C41—C42—C422—S421 | 0.8 (4) | ||||

| C41—C42—C522—S521 | −175.9 (7) |

Figure 1.

The molecular structure of compound (IIa), showing the atom-labelling scheme. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

Figure 2.

The molecular structure of compound (IIb), showing the atom-labelling scheme. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

Figure 3.

The molecular structure of compound (IIc), showing the atom-labelling scheme. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

Figure 4.

The molecular structure of compound (IId), showing the atom-labelling scheme. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

Figure 5.

The molecular structure of compound (IIe), showing the conformational disorder and the atom-labelling scheme. The major-disorder component is drawn with full lines and the minor-disorder component is drawn using broken lines. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

Despite this, there are some unexpected differences in the molecular orientations of the two arylvinyl units (Figs. 1 ▸–5 ▸ ▸ ▸ ▸ and Table 2 ▸). Thus, the orientation of the 2-styryl substituent in (IIb) differs from that in each of (IIa) and (IIc)–(IIe) by a rotation about the C2—C21 bond of approximately 180°. In addition, the orientation of the 4-stryl unit in (IIc) differs markedly from that in each of the other examples, but the torsion angle C3—C4—C41—C42 shows quite a wide range of variation (Table 2 ▸). These differences in conformation cannot reasonably be explained in terms of the patterns of hydrogen bonding discussed below (cf. Table 3 ▸).

Table 3. Hydrogen bonds and short intermolecular contacts (Å, °) for compounds (IIb)–(IIe).

Cg1–Cg4 represent the centroids of rings C421–C426, C4A/C5–C8/C8A, C311–C316 and C221–C216, respectively.

| Compound | D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (IIb) | C225—H225⋯N1i | 0.95 | 2.62 | 3.522 (2) | 158 | |

| C6—H6⋯Cg1ii | 0.95 | 2.65 | 3.4152 (16) | 138 | ||

| C422—H422⋯Cg2iii | 0.95 | 2.88 | 3.5843 (17) | 132 | ||

| (IIc) | C8—H8⋯O31iv | 0.95 | 2.51 | 3.164 (6) | 126 | |

| C5—H5⋯Cg3v | 0.95 | 2.96 | 3.728 (4) | 138 | ||

| C42—H42⋯Cg4vi | 0.95 | 2.88 | 3.766 (5) | 155 | ||

| C223—H223⋯Cg2vii | 0.95 | 2.84 | 3.429 (3) | 122 | ||

| (IId) | C225—H225⋯O31v | 0.95 | 2.37 | 3.266 (2) | 156 | |

| (IIe) | C8—H8⋯O31viii | 0.95 | 2.58 | 3.122 (3) | 116 | |

| C425—H425⋯O31ix | 0.95 | 2.45 | 3.361 (4) | 161 | ||

| C5—H5⋯Cg3v | 0.95 | 2.90 | 3.647 (3) | 136 | ||

| C423—H423⋯Cg3v | 0.95 | 2.76 | 3.449 (3) | 130 |

Symmetry codes: (i) −x +

, y −

, y −

, −z +

, −z +

; (ii) x, −y + 2, z +

; (ii) x, −y + 2, z +

; (iii) −x + 1, y, −z +

; (iii) −x + 1, y, −z +

; (iv) x +

; (iv) x +

, −y +

, −y +

, z +

, z +

; (v) −x + 1, −y + 1, −z + 1; (vi) x +

; (v) −x + 1, −y + 1, −z + 1; (vi) x +

, −y +

, −y +

, z −

, z −

; (vii) x −

; (vii) x −

, −y +

, −y +

, z +

, z +

; (viii) −x +

; (viii) −x +

, y −

, y −

, z; (ix) x, −y + 2, z −

, z; (ix) x, −y + 2, z −

.

.

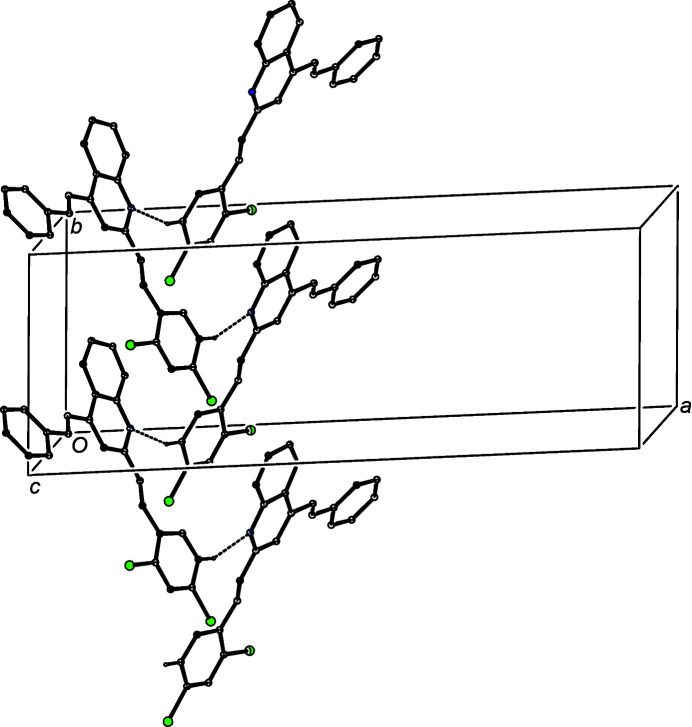

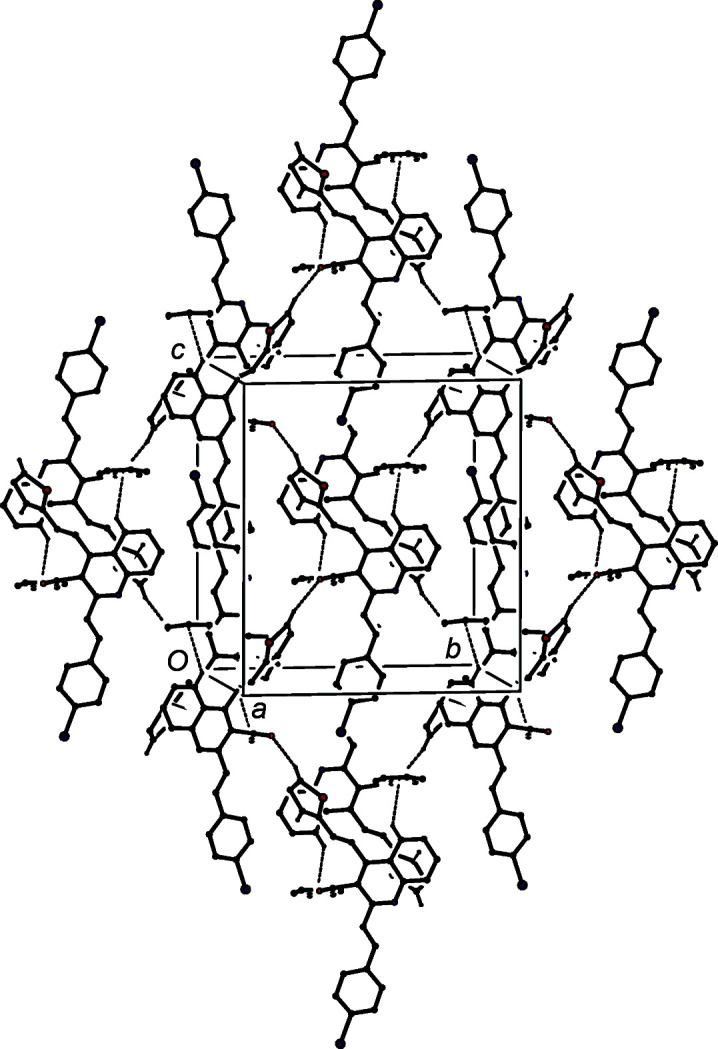

The patterns of supramolecular assembly in compounds (IIa)–(IIe) show some wide variations. Despite the large numbers of aromatic rings and C—H bonds in the molecules of (IIa), the crystal structure contains no significant direction-specific intermolecular interactions of any sort. By contrast, in the dichloro analogue (IIb), a combination of one C—H⋯N hydrogen bond and two independent C—H⋯π(arene) hydrogen bonds (Table 3 ▸) links the molecules into a three-dimensional framework structure, whose formation is readily analysed in terms of three simple substructures (Ferguson et al., 1998a

▸,b

▸; Gregson et al., 2000 ▸). The C—H⋯N hydrogen bonds link molecules of (IIb) which are related by the 21 screw axis along (

, y,

, y,

) to form a C(8) (Etter, 1990 ▸; Etter et al., 1990 ▸; Bernstein et al., 1995 ▸) chain running parallel to the [010] direction (Fig. 6 ▸). In the second substructure, the C—H⋯π(arene) hydrogen bond having atom C6 as the donor links molecules which are related by the c-glide plane at y = 1 to form a chain running parallel to the [001] direction (Fig. 7 ▸). The combination of the chains along [010] and [001] generates a sheet lying parallel to (100) in the domain 0 < x <

) to form a C(8) (Etter, 1990 ▸; Etter et al., 1990 ▸; Bernstein et al., 1995 ▸) chain running parallel to the [010] direction (Fig. 6 ▸). In the second substructure, the C—H⋯π(arene) hydrogen bond having atom C6 as the donor links molecules which are related by the c-glide plane at y = 1 to form a chain running parallel to the [001] direction (Fig. 7 ▸). The combination of the chains along [010] and [001] generates a sheet lying parallel to (100) in the domain 0 < x <

. A second sheet, related to the first by inversion, lies in the domain

. A second sheet, related to the first by inversion, lies in the domain

< x < 1.0, and adjacent sheets are linked by the third substructure which takes the form of a cyclic centrosymmetric dimer built from C—H⋯π(arene) hydrogen bonds having atom C422 as the donor (Fig. 8 ▸).

< x < 1.0, and adjacent sheets are linked by the third substructure which takes the form of a cyclic centrosymmetric dimer built from C—H⋯π(arene) hydrogen bonds having atom C422 as the donor (Fig. 8 ▸).

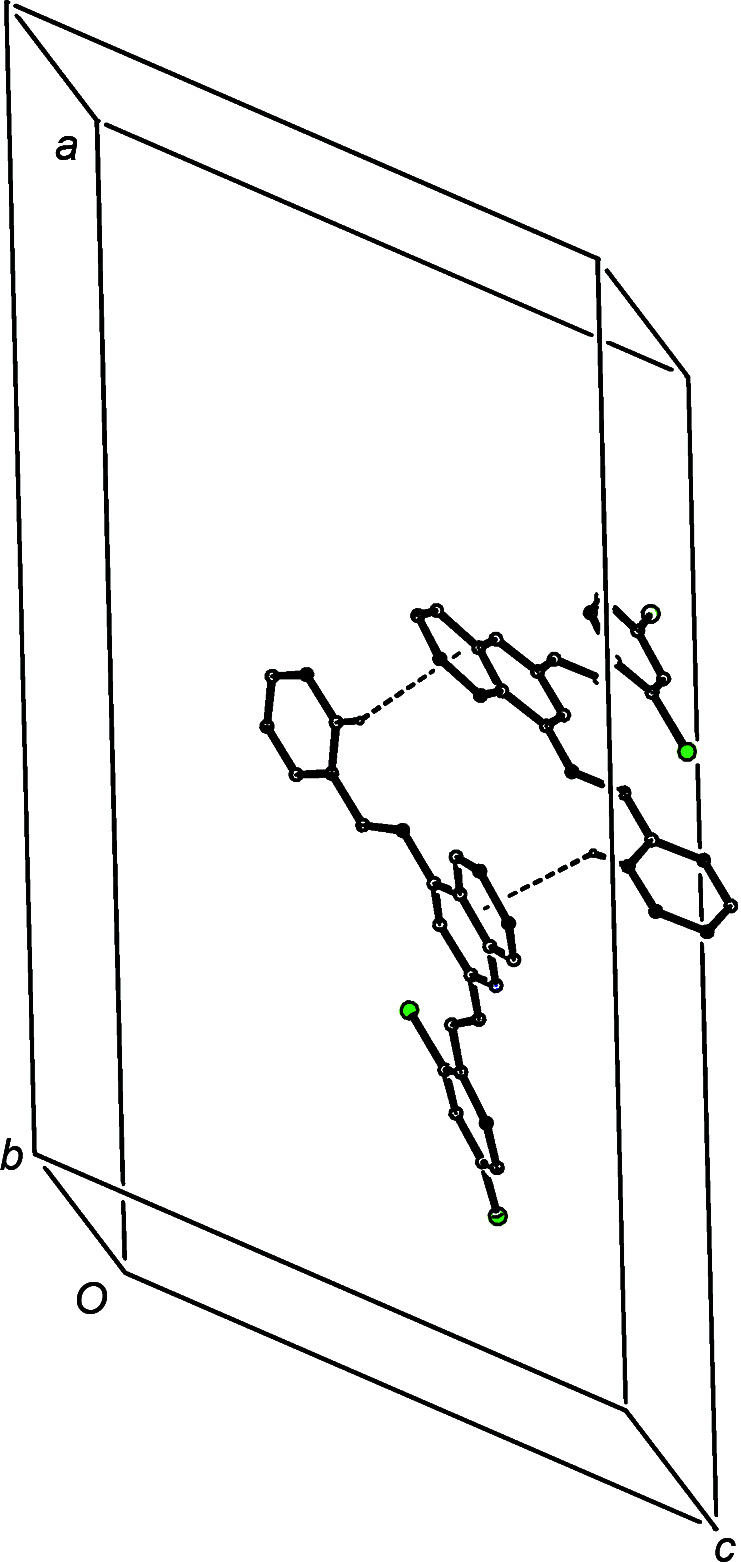

Figure 6.

Part of the crystal structure of compound (IIb), showing the formation of a C(8) chain parallel to [010], built from C—H⋯N hydrogen bonds, which are drawn as dashed lines. For the sake of clarity, H atoms which are not involved in the motif shown have been omitted.

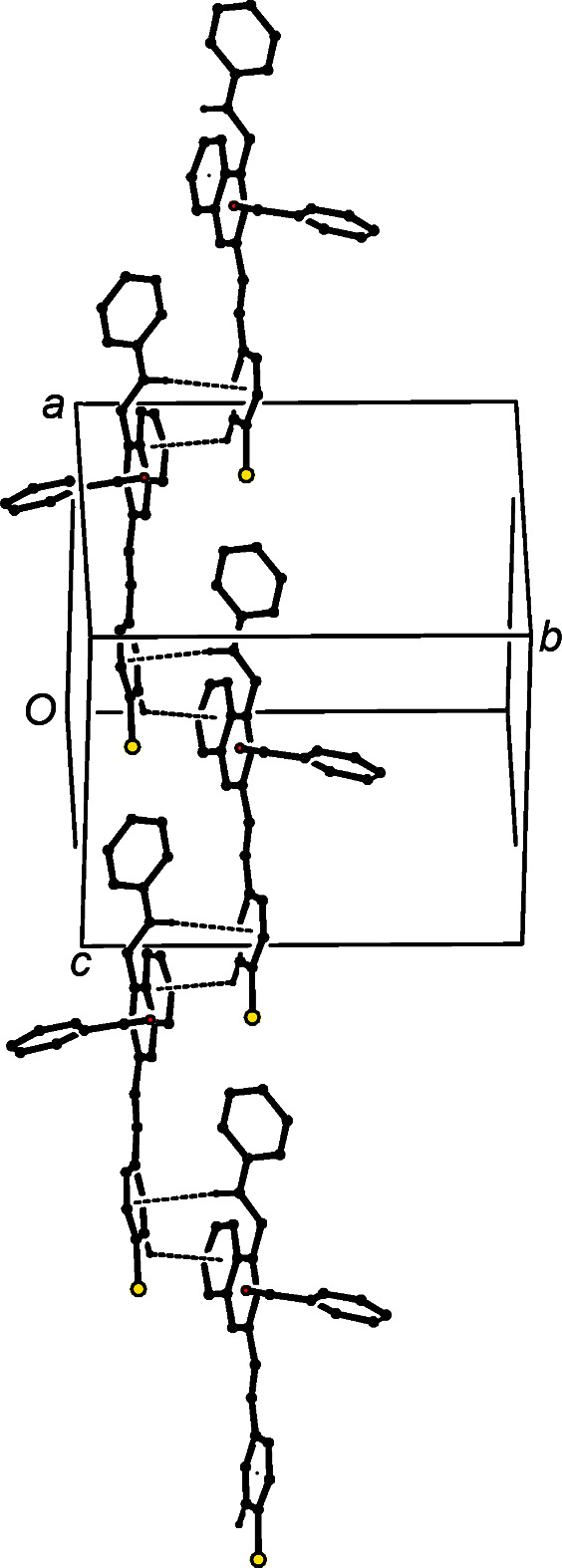

Figure 7.

Part of the crystal structure of compound (IIb), showing the formation of a chain parallel to [001], built from C—H⋯π(arene) hydrogen bonds, which are drawn as dashed lines. For the sake of clarity, H atoms which are not involved in the motif shown have been omitted.

Figure 8.

Part of the crystal structure of compound (IIb), showing the formation of a centrosymmetric dimer built from C—H⋯π(arene) hydrogen bonds, which are drawn as dashed lines. For the sake of clarity, H atoms which are not involved in the motif shown have been omitted.

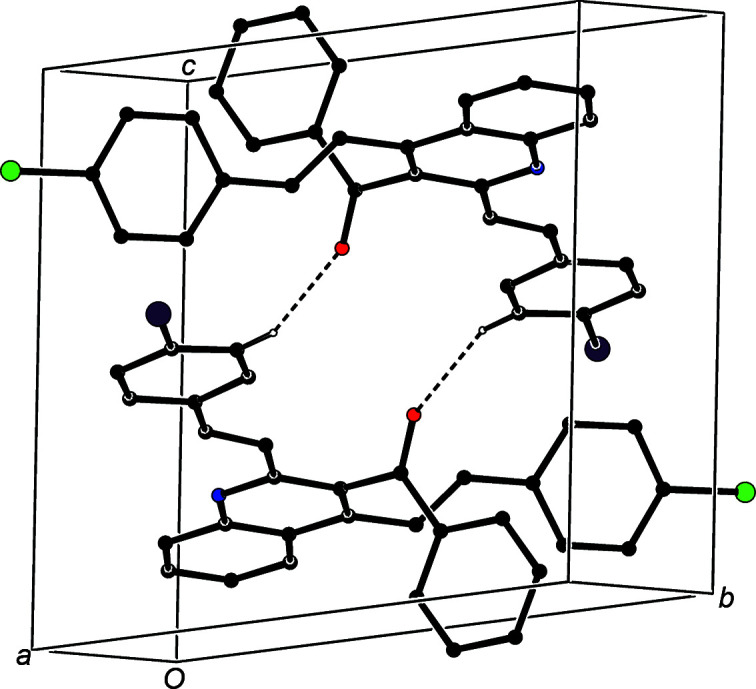

The short intermolecular C—H⋯O contact in compound (IIc) has a very small C—H⋯O angle (Table 3 ▸), and so cannot be regarded as structurally significant (Wood et al., 2009 ▸). However, the co-operative action of two C—H⋯π(arene) hydrogen bonds links molecules which are related by the n-glide plane at y =

into a chain of rings running parallel to the [10

into a chain of rings running parallel to the [10

] direction (Fig. 9 ▸). The structure also contains a third C—H⋯π(arene) contact, involving atom C5, but here the H⋯A distance is quite long; if this were regarded as structurally significant, its action would be to link the chains of rings into a sheet parallel to (101).

] direction (Fig. 9 ▸). The structure also contains a third C—H⋯π(arene) contact, involving atom C5, but here the H⋯A distance is quite long; if this were regarded as structurally significant, its action would be to link the chains of rings into a sheet parallel to (101).

Figure 9.

Part of the crystal structure of compound (IIc), showing the formation of a chain of rings running parallel to the [10

] direction and built from two independent C—H⋯π(arene) hydrogen bonds, which are drawn as dashed lines. For the sake of clarity, H atoms which are not involved in the motif shown have been omitted.

] direction and built from two independent C—H⋯π(arene) hydrogen bonds, which are drawn as dashed lines. For the sake of clarity, H atoms which are not involved in the motif shown have been omitted.

A single C—H⋯O hydrogen bond links inversion-related molecules of compound (IId) into a cyclic centrosymmetric

(20) dimer (Fig. 10 ▸), but there are no direction-specific interactions between adjacent dimers.

(20) dimer (Fig. 10 ▸), but there are no direction-specific interactions between adjacent dimers.

Figure 10.

Part of the crystal structure of compound (IId), showing the formation of a cyclic

(20) dimer built from C—H⋯O hydrogen bonds, which are drawn as dashed lines. For the sake of clarity, H atoms which are not involved in the motif shown have been omitted.

(20) dimer built from C—H⋯O hydrogen bonds, which are drawn as dashed lines. For the sake of clarity, H atoms which are not involved in the motif shown have been omitted.

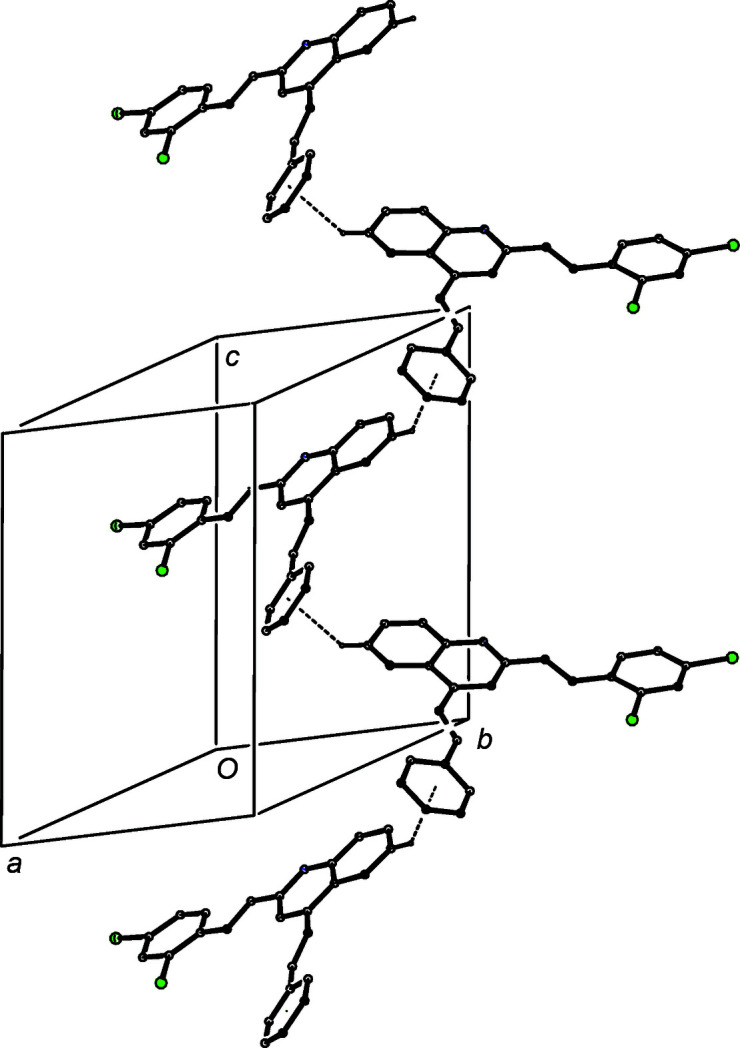

In the crystal structure of compound (IIe), the C—H⋯O contact involving atom C8 is not structurally significant (Wood et al., 2009 ▸), but the combination of the C—H⋯O hydrogen bond involving atom C425 with the two C—H⋯π(arene) hydrogen bonds links the molecules into a complex sheet lying parallel to (100) in the domain

< x <

< x <

(Fig. 11 ▸). A second sheet, related to the first by the action of the 21 screw axes, lies in the domain

(Fig. 11 ▸). A second sheet, related to the first by the action of the 21 screw axes, lies in the domain

< x < 1.35, but there are no direction-specific interactions between adjacent sheets.

< x < 1.35, but there are no direction-specific interactions between adjacent sheets.

Figure 11.

Part of the crystal structure of compound (IIe), showing the formation of a sheet lying parallel to {100} and built from a combination of C—H⋯O and C—H⋯π(arene) hydrogen bonds, which are drawn as dashed lines. For the sake of clarity, the minor-disorder component and H atoms which are not involved in the motif shown have been omitted.

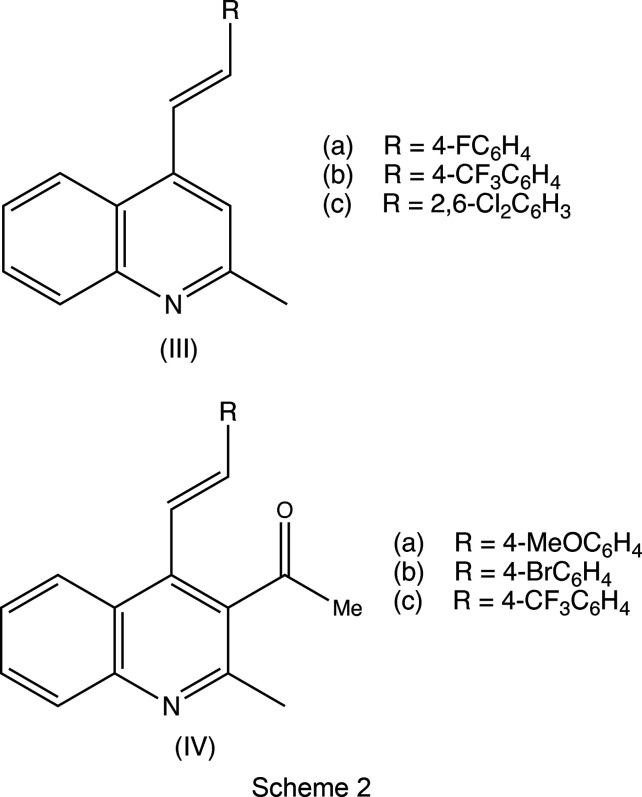

It is of interest briefly to compare the supramolecular assembly in compounds (IIa)–(IIe) reported here with those of some simpler 2-methyl-4-styrylquinoline analogues. Crystal structures have been reported (Vera et al., 2022 ▸) for compounds (IIIa)–(IIIc) (see Scheme 2), which have no substituent at position C3 of the quinoline unit, and are thus related to compounds (IIa) and (IIb) reported here. In the crystal structure of (IIIa), the molecules are linked into sheets by a combination of C—H⋯N hydrogen bonds and π–π stacking interactions, while a similar combination of interactions links the molecules of (IIIb) into chains of rings. There are no hydrogen bonds in the structure of (IIIc), but a π–π stacking interaction links the molecules into stacks.

Compounds of the type (IV) (see Scheme 2), carrying a 3-acetyl substituent, are thus analogous to compounds (IIc)–(IIe). Compounds (IVa)–(IVc) are isomorphous (Rodríguez et al., 2020 ▸); in each, the molecules are linked into chains by a C—H⋯O hydrogen bond, but only in (IVa) is this augmented by a C—H⋯π hydrogen bonds to form a chain of rings. Thus, although (IVa)–(IVc) are isomorphous, they are not strictly isostructural.

Summary

We have developed an efficient and highly versatile route to 2,4-distyrylquinolines and to their 2-arylvinyl analogues, using only simple and readily accessible building blocks such as simple aldehydes and ketone. We have characterized by spectroscopic means (IR, 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, and HRMS) five representative examples and we have determined their molecular and crystal structures, which fully confirm the molecular constitutions deduced from the spectroscopic data, as well as providing further information on their molecular conformations in the solid state, and on their supramolecular assemblies.

Supplementary Material

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) global, IIa, IIb, IIc, IId, IIe. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) IIa. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIasup2.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) IIb. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIbsup3.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) IIc. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIcsup4.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) IId. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIdsup5.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) IIe. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIesup6.hkl

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIasup7.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIbsup8.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIcsup9.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIdsup10.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIesup11.cml

Acknowledgments

JC thanks the Centro de Instrumentación Científico-Técnica of the Universidad de Jaén (UJA) and its staff for the data collection. AP thanks the Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Extensión of the Industrial University of Santander for support. JC thanks the Universidad de Jaén and the Consejería de Economía, Innovación, Ciencia y Empleo (Junta de Andalucá, Spain) for financial support.

Funding Statement

Funding for this research was provided by: Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Extensión of the Industrial University of Santander (grant No. 2680).

References

- Afzal, O., Kumar, S., Haider, R., Ali, R., Kumar, R., Jaggi, M. & Bawa, S. (2015). Eur. J. Med. Chem. 97, 871–910. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Alacíd, E. & Nájera, C. (2009). J. Org. Chem. 74, 8191–8195. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ardila, D. M., Rodríguez, D. F., Palma, A., Díaz Costa, I., Cobo, J. & Glidewell, C. (2022). Acta Cryst. C78, 671–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bernotas, R. C., Singhaus, R. R., Kaufman, D. H., Ullrich, J., Fletcher, H., Quinet, E., Nambi, P., Unwalla, R., Wilhelmsson, A., Goos-Nilsson, A., Farnegardh, M. & Wrobel, J. (2009). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17, 1663–1670. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, J., Davis, R. E., Shimoni, L. & Chang, N.-L. (1995). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 34, 1555–1573.

- Bruker (2016). SADABS. Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

- Bruker (2017). SAINT. Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

- Bruker (2018). APEX3. Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

- Cai, Z., Zhou, W. & Sun, L. (2007). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 15, 7809–7829. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chang, F. S., Chen, W., Wang, C., Tzeng, C. C. & Chen, Y. L. (2010). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 18, 124–133. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y., Zhao, Y., Lu, C., Tzeng, C. & Wang, J. P. (2006). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14, 4373–4378. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cieslik, W., Musiol, R., Nycz, J. E., Jampilek, J., Vejsova, M., Wolff, M., Machura, B. & Polanski, J. (2012). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 20, 6960–6968. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cortes, J. E., Apperley, J. F., DeAngelo, D. J., Deininger, M. W., Kota, V. K., Rousselot, P. & Gambacorti-Passerini, C. (2018). J. Hematol. Oncol. 11, 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Etter, M. C. (1990). Acc. Chem. Res. 23, 120–126.

- Etter, M. C., MacDonald, J. C. & Bernstein, J. (1990). Acta Cryst. B46, 256–262. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fakhfakh, M. A., Fournet, A., Prina, E., Mouscadet, J.-F., Franck, X., Hocquemiller, R. & Figadère, B. (2003). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 11, 5013–5023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, G., Glidewell, C., Gregson, R. M. & Meehan, P. R. (1998a). Acta Cryst. B54, 129–138.

- Ferguson, G., Glidewell, C., Gregson, R. M. & Meehan, P. R. (1998b). Acta Cryst. B54, 139–150.

- Flack, H. D. & Bernardinelli, G. (1999). Acta Cryst. A55, 908–915. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Franck, X., Fournet, A., Prina, E., Mahieux, R., Hocquemiller, R. & Figadère, B. (2004). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 14, 3635–3638. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gao, W., Li, Z., Xu, Q. & Li, Y. (2018). RSC Adv. 8, 38844–38849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, J., Swarup, V., Saxena, A., Das, S., Hazra, A., Paira, P., Banerjee, S., Mondal, N. B. & Basu, A. (2008). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents, 32, 349–354. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, A. M., Bursavich, M. G., Lombardi, S., Georgiadis, K. E., Reifenberg, E., Flannery, C. & Morris, E. A. (2008). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 18, 6454–6457. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gregson, R. M., Glidewell, C., Ferguson, G. & Lough, A. J. (2000). Acta Cryst. B56, 39–57. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Groom, C. R., Bruno, I. J., Lightfoot, M. P. & Ward, S. C. (2016). Acta Cryst. B72, 171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hazra, S., Tiwari, V., Verma, A., Dolui, P. & Elias, A. J. (2020). Org. Lett. 22, 5496–5501. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.-Q., Gao, C., Zhang, S., Xu, L., Xu, Z., Feng, L.-S., Wu, X. & Zhao, F. (2017). Eur. J. Med. Chem. 139, 22–47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jamal, Z. & Teo, Y. C. (2014). Synlett, 25, 2049–2053.

- Jamal, Z., Teo, Y.-C. & Lim, G. S. (2016). Tetrahedron, 72, 2132–2138.

- Kamal, A., Rahim, A., Riyaz, S., Poornachandra, Y., Balakrishna, M., Kumar, C., Hussaini, S., Sridhar, B. & Machiraju, P. (2015). Org. Biomol. Chem. 13, 1347–1357. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kaur, K., Jain, M., Reddy, R. P. & Jain, R. (2010). Eur. J. Med. Chem. 45, 3245–3264. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S., Bawa, S., Drabu, S. & Panda, B. P. (2011). Med. Chem. Res. 20, 1340–1348.

- Kumar, S., Bawa, S. & Gupta, H. (2009). Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 9, 1648–1654. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lam, K.-H., Gambari, R., Lee, K. K.-H., Chen, Y.-X., Kok, S. H.-L., Wong, R. S.-M., Lau, F.-Y., Cheng, C.-H., Wong, W.-Y., Bian, Z.-X., Chan, A. S.-C., Tang, J. C.-O. & Chui, C.-H. (2014). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 24, 367–370. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lauria, A., La Monica, G., Bono, A. & Martorana, A. (2021). Eur. J. Med. Chem. 220, 113555. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lee, V. M., Gavrishova, T. N. & Budyka, M. F. (2009). Chem. Heterocycl. C, 45, 1279–1280.

- Leonard, J. T. & Roy, K. (2008). Eur. J. Med. Chem. 43, 81–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li, X., Huang, B., Wang, J. W., Zhang, Y. Y. & Liao, W. B. (2021). J. Chem. Res. 45, 903–910.

- Mahajan, S., Gupta, S., Jariwala, N., Bhadane, D., Bhutani, L., Kulkarni, S. & Singh, I. (2018). Lett. Drug. Des. Discov. 15, 937–944.

- Matada, B. S., Pattanashettar, R. & Yernale, N. G. (2021). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 32, 115973. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Meléndez, A., Plata, E., Rodríguez, D., Ardila, D., Guerrero, S., Acosta, L., Cobo, J., Nogueras, M. & Palma, A. (2020). Synthesis, 52, 1804–1822.

- Moss, G. P. (1996). Pure Appl. Chem. 68, 2193–2222.

- Mousnier, A., Leh, H., Mouscadet, J.-F. & Dargemont, C. (2004). Mol. Pharmacol. 66, 783–788. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mrozek-Wilczkiewicz, A., Kuczak, M., Malarz, K., Cieślik, W., Spaczyńska, E. & Musiol, R. (2019). Eur. J. Med. Chem. 177, 338–349. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mrozek-Wilczkiewicz, A., Spaczynska, E., Malarz, K., Cieślik, W., Rams-Baron, M., Kryštof, V. & Musiol, R. (2015). PLoS One, 10, e0142678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Musiol, R. (2017). Exp. Opin. Drug. Discov. 12, 583–597. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Musiol, R. (2020). Med. Chem. 16, 141–154. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Musiol, R., Serda, M., Hensel-Bielowka, S. & Polanski, J. (2010). Curr. Med. Chem. 17, 1960–1973. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Okombo, J. & Chibale, K. (2018). MedChemComm, 9, 437–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Omar, W. A. E. & Hormi, O. E. O. (2009). Tetrahedron, 65, 4422–4428.

- Orozco, D., Kouznetsov, V. V., Bermúdez, A., Vargas Méndez, L. Y., Mendoza Salgado, A. R. & Meléndez Gómez, C. M. (2020). RSC Adv. 10, 4876–4898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, D., Guerrero, S. A., Palma, A., Cobo, J. & Glidewell, C. (2020). Acta Cryst. C76, 883–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Satish, G., Ashok, P., Kota, L. & Ilangovan, A. (2019). ChemistrySelect, 4, 1346–1349.

- Sharma, R., Abdullaha, M. & Bharate, S. B. (2017). J. Org. Chem. 82, 9786–9793. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2015a). Acta Cryst. A71, 3–8.

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2015b). Acta Cryst. C71, 3–8.

- Solomon, R. V. & Lee, H. (2011). Curr. Med. Chem. 18, 1488–1508. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Spek, A. L. (2020). Acta Cryst. E76, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Staderini, M., Cabezas, N., Bolognesi, M. L. & Menéndez, J. C. (2011). Synlett, 2011, 2577–2579.

- Szczepaniak, J., Cieślik, W., Romanowicz, A., Musioł, R. & Krasowska, A. (2017). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents, 50, 171–176. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vera, D. R., Mantilla, J. P., Palma, A., Cobo, J. & Glidewell, C. (2022). Acta Cryst. C78, 524–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wood, P. A., Allen, F. H. & Pidcock, E. (2009). CrystEngComm, 11, 1563–1571.

- Yadav, P. & Shah, K. (2021). Bioorg. Chem. 109, 104639. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yaragorla, S., Singh, G. & Dada, R. (2015). Tetrahedron Lett. 56, 5924–5929.

- Zhang, G.-F., Liu, X., Zhang, S., Pan, B. & Liu, M.-L. (2018). Eur. J. Med. Chem. 146, 599–612. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C., Li, Z., Fang, Y., Jiang, S., Wang, M. & Zhang, G. (2020). Tetrahedron, 76, 130968.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) global, IIa, IIb, IIc, IId, IIe. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) IIa. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIasup2.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) IIb. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIbsup3.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) IIc. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIcsup4.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) IId. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIdsup5.hkl

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) IIe. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIesup6.hkl

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIasup7.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIbsup8.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIcsup9.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIdsup10.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229623001432/ov3167IIesup11.cml