Abstract

Ovarian cancer is one of the most aggressive malignancies in women and usually presents at an advanced stage. Complete tumor debulking and platinum sensitivity are the two important determinants of survival in ovarian cancer. Upper abdominal surgery with bowel resections and peritonectomy are usually needed to achieve optimal cytoreduction. Splenic disease in the form of diaphragmatic peritoneal disease or omental caking at the splenic hilum is not infrequent. Around 1–2% of these require distal pancreaticosplenectomy (DPS) and the decision to perform DPS versus splenectomy should be made early in the intraoperative period to prevent unnecessary hilar dissection and bleeding. We hereby describe the surgical anatomy of the spleen and pancreas and point of technique of splenectomy and DPS specific to advanced ovarian cancers.

Keywords: Splenectomy, Distal pancreaticosplenectomy, Advanced ovarian cancer

Background

Ovarian cancer is one of the most aggressive malignancies and accounts for majority of deaths from gynecological cancers as it usually presents at an advanced stage [1]. Burden and size of residual disease at the completion of debulking surgery and varying degrees of platinum sensitivity determine the progression-free interval from initial diagnosis and first recurrence [2]. Platinum sensitivity is largely dependent on tumor biology and host genetic makeup, whereas aggressive debulking surgery is largely dependent on surgical expertise and perioperative care [3–5].

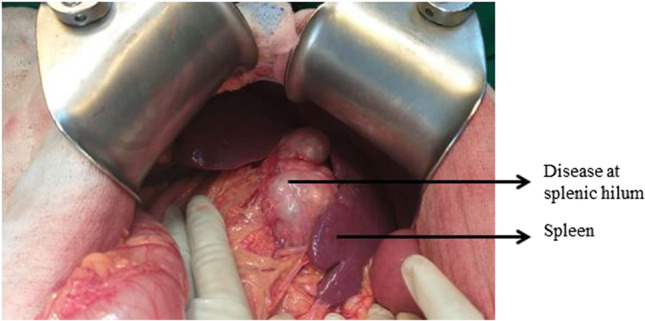

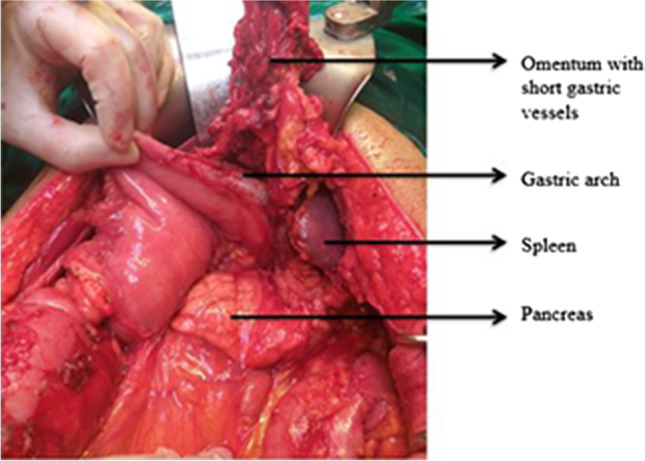

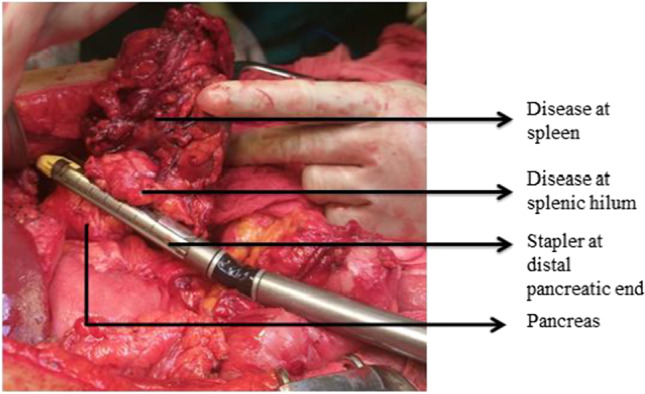

To achieve optimal cytoreduction, upper abdominal surgery has been included by gynecologic oncologists worldwide in their surgical armamentarium and is widely accepted. Bowel resections and peritonectomy (partial/total peritonectomy) procedures are similar to those performed for other gastrointestinal (GI) malignancies. Largely, in published literature, the technique of splenectomy is described for trauma and benign diseases and technique of distal pancreaticosplenectomy (DPS) described for tail of the pancreas tumors and bowel disease [6–9]. However, splenic disease which is seen in advanced ovarian malignancy is either due to diaphragmatic peritoneal disease causing splenic surface adhesions to left dome or due to omental caking which distorts and obscures the anatomy at the splenic hilum (Fig. 1). Splenic parenchymal disease is otherwise rare in advanced ovarian cancer [10, 11]. Around 1–2% of advanced ovarian cancers require DPS as opposed to just splenectomy with or without transverse colectomy [12, 13].

Fig. 1.

Image showing disease at the splenic hilum

The decision to perform DPS versus splenectomy alone should be made early in the intraoperative period when hilum is studded with disease to prevent unnecessary hilar dissection and bleeding. We hereby describe the surgical anatomy of the spleen and pancreas and technique of splenectomy and DPS specific to advanced ovarian cancers.

Surgical Anatomy

Pancreas

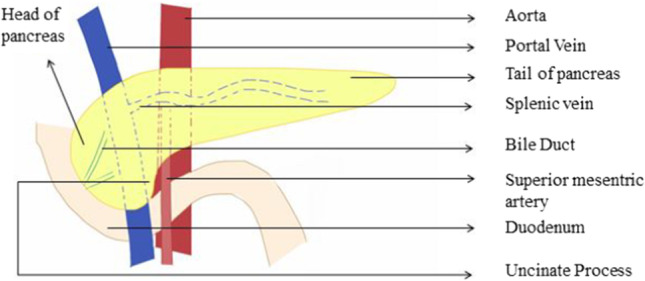

The pancreas is a J-shaped soft lobulated retroperitoneal organ lying transversely behind the posterior wall of the stomach across the lumbar (L1-2) spine (Fig. 2). It is divided somewhat arbitrarily into the head, neck, body, and tail. The head of the pancreas lies in the duodenal C-loop in front of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and left kidney [14]. The body and tail of the pancreas run obliquely upward to the left in front of the aorta and left kidney. The pancreatic neck sits anterior to the superior mesenteric and portal veins and the narrow tip of the tail of the pancreas reaches the splenic hilum in the splenorenal (lienorenal) ligament. The uncinate process is an extension of the lower half of the head towards the left and insinuates behind the superior mesenteric vessels (Fig. 2). The tail of the pancreas terminates variably in relation to the hilum of the spleen, most often abutting the splenic capsule at hilum or may terminate two cm from splenic substance. The root of the transverse mesocolon attaches to the ventral surface of the head and neck and anterior surface of the body of the pancreas. The medial body of the pancreas overlies the abdominal aorta and origin of superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and the lateral part overlies the left crus of the diaphragm, left renal hilum, and left suprarenal gland.

Fig. 2.

Anatomy and relation of the pancreas to adjoining structures

Vascular Supply of Pancreas

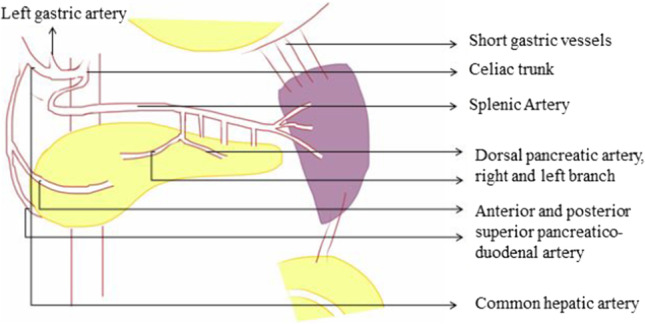

The pancreas has a rich blood supply from celiac axis and SMA with multiple collaterals and the neck acting as a watershed area between the two (Fig. 3). The splenic artery runs along the superior border of the pancreas and gives off three branches to the dorsal surface of the pancreas [14]. The gastroduodenal artery, a branch of CHA, runs behind the first part of duodenum in front of the neck of the pancreas and divides into right gastroepiploic artery and superior pancreatico-duodenal artery (SPDA). The SMA descends down in front of uncinate process and gives off inferior PDA (IPDA) before entering the small bowel mesentery.

Fig. 3.

Arterial supply of the pancreas and spleen

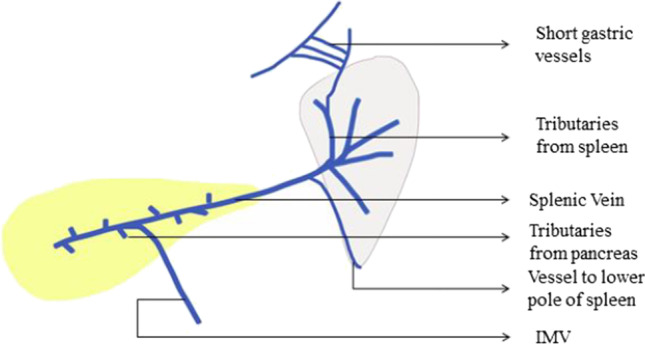

The veins accompany the SPDA and IPDA which drain into portal vein and SMV, respectively. The splenic vein receives five to twelve tributaries from the tail and body of the pancreas besides receiving the inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) just 2–3 cm before joining the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) to form the hepatic portal vein (Fig. 4). Uncinate veins often drain into a large first jejunal tributary vein, which then empties into the SMV. A nearly constant posterior superior pancreatico-duodenal vein enters the right lateral side of the portal vein at the level of the duodenum. [14].

Fig. 4.

Venous drainage of the pancreas and spleen

Lymphatic vessels draining the pancreas accompany the pancreatic arteries. The body and tail of the pancreas drain into the retropancreatic nodes. The upper half of the head and neck drains into the celiac lymph nodes while the lower half of the head drains into the superior mesenteric nodes. The main pancreatic duct (of Wirsung) runs along the length of gland and joins the terminal part of common bile duct to form a common channel (ampulla of Vater) and opens at the postero-medial wall of the second part of duodenum. Another accessory duct (of Santorini) passes from the upper part of the head of the pancreas and drains around 2 cm proximal to the opening of major duct.

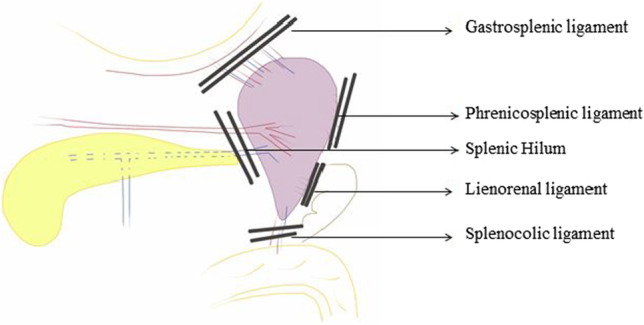

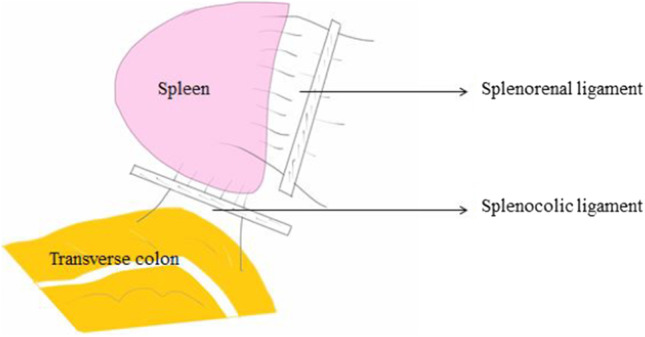

Spleen

The spleen is the largest lymphoid organ in the body, fist-sized, and is encapsulated by a fibroelastic capsule. It sits underneath the left diaphragm and spans 9–11th rib along the left mid to posterior axillary line (Fig. 5). The anterior end lies along the greater curvature of the stomach and tail of the pancreas and is directed forward and downwards to reach midaxillary line [15, 16]. The posterior end is rounded and rests on the upper pole of the left kidney. The splenic hilum is found on the infero-medial part of the gastric impression and includes the splenic vessels and nerves and provides attachment to gastrosplenic and lienorenal ligaments. The splenic flexure of the colon is inferior to the spleen and the tail of the pancreas is generally within one cm of the splenic hilum.

Fig. 5.

Images showing relation of the spleen and pancreas

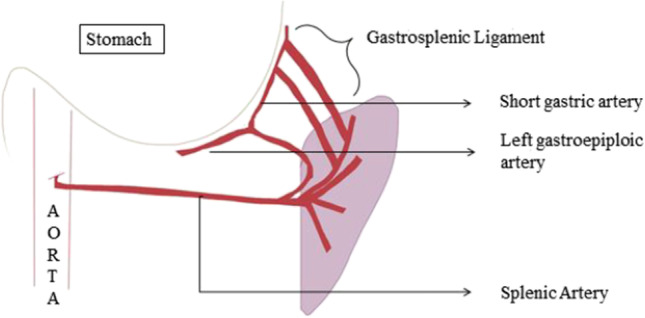

Vascular Supply of Spleen

The majority of arterial supply is from the splenic artery, one of the major branches from celiac axis of the aorta. It has a serpentine course that runs along the superior border of the pancreas, giving off a few pancreatic branches and a branch to the superior pole of the spleen prior to diving into the splenic hilum (Figs. 3, 4). Several short gastric vessels from the left gastroepiploic artery also supply the spleen. Segmental venous tributaries unite into the main splenic vein in the hilum which is intimately associated with the posterior surface of the tail and body of the pancreas. The short gastric, left gastro-omental, pancreatic, and inferior mesenteric veins are its tributaries.

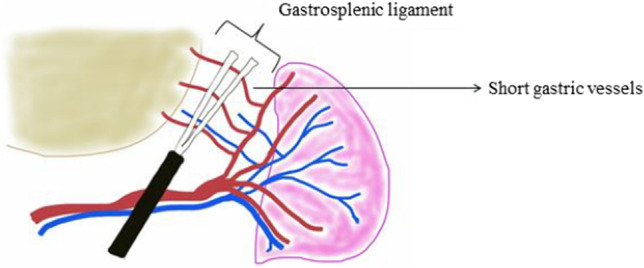

The spleen is intraperitoneal and is suspended in this position by various ligaments. The gastrosplenic ligament extends from the hilum of the spleen to the greater curvature of the stomach and contains the left gastroepiploic vessels and short gastric vessels (Fig. 11). The splenorenal ligament extends from the hilum of the spleen to the anterior surface of the left kidney through Gerota’s fascia [15, 16]. The splenocolic ligament extends from the splenic flexure of the colon to the diaphragm along the midaxillary line; it can be short and may contain vessels to the lower pole of the spleen. There may be attachments from the lower pole of the spleen to the omentum to various degrees. Attachments to the diaphragm may also be present to varying degrees. Accessory spleens are nodules of the splenic tissue, usually ranging from 0.5 to 4 cm in size and are present in 10 to 20% of patients. They can be located anywhere in the abdomen but are most often found in the splenic hilum or omentum near the spleen (Fig. 6).

Fig. 11.

Splenectomy (anterior approach)

Fig. 6.

Various common locations of accessory spleen

Surgical Steps to Splenectomy Alone with or Without DPS

Mobilization of Spleen

Lateral Approach

The midline abdominal incision needs to be extended, usually up to the xiphisternum. The spleen is retracted downwards and medially with the help of a gauze piece to expose the various peritoneal attachments to the diaphragm. The retraction needs to be done very carefully and gently as the splenic capsule is very thin and the parenchyma is soft and friable. Forceful retraction or handling can easily lead to capsular and parenchymal tear with excessive blood loss which can only be controlled after ligation of the splenic vessels and splenectomy is completed. Once the retraction is achieved, the avascular peritoneal attachments (phrenicosplenic, splenocolic, and lienorenal ligaments) are usually dissected and removed using electrocautery or bipolar electrocautery [17, 18] (Figs. 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11). These peritoneal ligaments are usually avascular except the gastrosplenic ligament which contains the short gastric vessels and should be carefully ligated and divided (Figs. 7, 8). After mobilization of the spleen to medial side, the decision to perform DPS versus splenectomy depends on the extent of disease at the hilum and preferably should be decided at the beginning of mobilization of the spleen. This decision reduces surgical time and also prevents unnecessary hemorrhage during mobilization of the hilum. If the splenic hilum is not obscured or infiltrated by large ovarian metastatic disease, the hilum is carefully dissected wherein the splenic artery and vein are identified and doubly ligated with non-absorbable suture or hemostatic clips or a vascular stapler. Since the tail of the pancreas is relatively close to the hilum, it is preferred to stay as close to the splenic surface as possible. With this approach, the tail of the pancreas is spared and splenectomy with greater omentectomy may be done.

Fig. 7.

Gastrosplenic ligament division

Fig. 8.

Steps towards gastrosplenic division

Fig. 9.

Splenocolic and splenorenal ligament division

Fig. 10.

Division of splenic hilum

Anterior Approach

This is an alternative approach in which the splenic vessels are secured and ligated early in the course before handling spleen. Dissection is initiated by dividing the gastrocolic ligament, thereby revealing the lesser sac and lower pole of the spleen. Complete mobilization of greater curvature of the stomach is performed by dividing gastrosplenic ligament with the accompanying short gastric vessels which are clipped and divided. Control of the splenic artery away from the splenic hilum is achieved on the superior border of the pancreas (Fig. 9). Hilar dissection is done from an inferior to superior fashion followed by individual clipping of hilar vessels or by ligation of the splenic artery just proximal to the branching [17, 18]. The splenic vein is difficult to ligate without pancreatic tail resection as it lies behind the pancreatic parenchyma and hence individual polar veins needs to be ligated or clipped. In the event of bleeding, during dissection of the splenic vessels at the hilum, often control is achieved by applying multiple clamps at the hilum and the spleen is removed in quick succession. Alternatively, depending on the intraoperative situation, the splenic artery is controlled and ligated proximal to the hilum/bleeding area and in most events a distal pancreatectomy is necessary to help early ligation of the splenic vein and completing splenectomy. Once the short gastric and hilar vessels are ligated, the lateral and posterior attachments of the spleen are divided. This step may require significant traction on the spleen, resulting in avulsion of the splenic parenchyma. The evolution of the technique has come with better understanding of the surgical anatomy of the spleen, making the lateral approach preferable in absence of splenomegaly and lack of adhesions/disease around the splenic capsule and the lateral ligamentous attachments.

Splenectomy is a relatively simple procedure when done in normal-sized spleens and as an elective procedure. But in cases of malignant diseases, in presence of extensive peritoneal disease, surgical trauma, splenomegaly, disease at the splenic hilum, and extensive adhesions, there are chances of injury at various steps and it should be managed cautiously. Important steps requiring special attention depending on the anatomical variation are highlighted below.

Dealing with short gastric vessels:

Just before entering the splenic hilum, either the main trunk of the splenic artery or one or other of the terminal divisions of the splenic artery gives rise to the short gastric arteries and the left gastroepiploic artery (Fig. 12). These vessels travel proximally to the gastric fundus within the gastrosplenic ligament, while the left gastroepiploic artery travels distally, along the greater curvature, to meet the right gastroepiploic artery [15, 16].

These vessels do not create much hemorrhage in cases with normal/preserved anatomy, but in cases of portal hypertension or extensive splenic hilar metastases, extensive hemorrhage may occur because of friable and dilated veins and collaterals and these vessels should be individually ligated with utmost care.

If gastric wall tissue is incorporated into the suture ligature while dealing with short gastric vessels, gastric fistula can result from necrosis of the gastric wall.

A Lambert suture may be placed in the gastric wall in a seromuscular fashion to avoid the complication of gastric fistula when one is unable to identify the source of bleeding from the stomach or in cases of serosal tears during retraction or handling (Fig. 13).

Dealing with splenic vein:

Fig. 12.

Short gastric vessels

Fig. 13.

Lambert’s suture

A variable number of segmental venous tributaries (3–6) emerge from the splenic hilum and unite within the splenorenal ligament to form the trunk of the splenic vein (Fig. 14). The splenic vein pursues a straight course unlike the splenic artery and is intimately associated or is partially embedded in a fibrous tunnel within the posterior wall of the body and tail of the pancreas (Fig. 14). IMV drains into the splenic vein near the splenoportal confluence behind pancreatic body. There are also several tributaries from the pancreatic tissue that directly enter the splenic vein. During splenectomy alone, these small veins from the pancreas are never encountered; however, their knowledge is important while dissection and ligation of the splenic vein during DPS.

Prevention: Early vascular control of the splenic vessels proximal to the site of proposed pancreatic transection allows for minimization of any bleeding from the perforating vessels.

Dealing with splenic hilum:

Fig. 14.

Splenic vein and its tributaries

Dissection and ligation (double ligation or transfixation) of individual hilar vessels can be performed; however, it can result in bleeding or injury to the tail of the pancreas. Dissection is carried out at the hilum in close proximity to the spleen to avoid injury to the pancreas [19]. Alternatively, a linear cutting stapler with a vascular load can be used to divide the hilum after complete mobilization of the spleen from its lateral attachments and lifting the pancreatic tail from retroperitoneum (Fig. 10). If pancreatic tail is in close relation to the splenic hilum, it can be included in the staple line.

While delivering the spleen into the wound with sharp dissection of the posterior attachments, care should be taken to not divide posterior attachments too far medially as we may enter the splenic vein.

It is also important to avoid axial rotation of the spleen before securing the splenic vessels with vascular loop or clamps; such rotation may lead to disruption of the splenic vein or occasionally artery as well.

Other aberrant vessels:

There is often a separate vessel to the lower pole inferior to the hilar bundle, in the splenocolic ligament, that may need to be separately clipped [20] (Fig. 14). Generally, clips are not preferred at the splenic hilum as they can affect the ability to safely staple the vascular structures, if vascular stapler is used.

There may be attachments from the lower pole of the spleen to the omentum to various degrees. Care must be taken to avoid excessive traction on the omentum, as this is the area that usually results in capsular tears.

Attachments to the diaphragm may also be present with small vessels to varying degrees.

Splenomegaly:

In cases of splenomegaly, it is often preferred to place a vascular loop or vascular clamp on the splenic vessels and doubly ligate the vessels with heavy non-absorbable suture. One may then proceed with suture ligation using a transfixed technique. This may avoid slipped-off sutures and helps prevent postoperative bleeding [21].

Larger and pathologic spleens tend to have more attachments, and may contain aberrant vessels that are parasitized off the diaphragm or splenocolic attachments, which may complicate an otherwise bloodless field of dissection.

Intraoperative Complications

Intraoperative complications may include splenic capsular rupture, pancreatic, vascular, colonic, gastric, and diaphragmatic injuries. Bleeding from major vessels is dealt with as described above in detail.

Rupture of splenic capsule:

Splenic capsule may rupture during handling, mobilization, or due to dense adhesions or a large spleen. Ligation of the splenic artery at the hilum of the spleen early in the course of mobilization will limit blood loss if splenic injury occurs.

Argon beam coagulation or other local measures can temporarily halt splenic capsular or ligamentous bleeding; however, the best and most effective way is placing packs around the spleen while hilar dissection to ligate the splenic artery is being performed.

Pancreatic injury:

Injury to the pancreas may occur in around 3% of cases which may be unrecognized intraoperatively [22]. Postoperatively these patients can develop pancreatitis if injury is severe which can be detected by high serum amylase and lipase levels in presence of signs of pancreatitis (epigastric pain, delayed gastric emptying, fever), or can develop pancreatic fistula.

Symptoms and signs usually develop within 4 to 5 days after splenectomy.

Pancreatic injury can be prevented by careful manipulation of the pancreas during splenectomy and by maintaining a distance between the pancreatic tail and the splenic hilum while isolating the splenic vessels. Superficial injuries generally do not need any intervention when detected intraoperatively. Deep parenchymal injuries at the pancreatic tail region should be managed by distal pancreatectomy.

Drains are not routinely required, except in cases where an injury of the tail of the pancreas is suspected or confirmed.

Colonic/gastric injuries:

These can be best avoided by maintaining the anatomical plane during surgery during dissection of splenocolic and gastrocolic ligaments.

When detected intraoperatively, they should be managed appropriately by placing seromuscular/full thickness sutures or local/formal resection of the organ, depending on the extent of injury.

If undetected, they may present as sepsis with bilious/feculent drain effluent and may lead to significant morbidity and mortality if not detected and treated on time.

Diaphragmatic injury:

In cases with adhesions/disease at the diaphragmatic attachments, diaphragmatic injury may happen and resection may be required. Diaphragmatic defect should be closed with non-absorbable suture and often an intercostal drainage tube is required.

Postoperative Complications

According to the latest literature, the overall morbidity and mortality associated with splenectomy ranges from 0 to 30% and 0 to 8.8%, respectively. Early postoperative complications include pulmonary complications (most commonly left lower lobe atelectasis), pleural effusion, pneumonia, subphrenic abscess, ileus, portal vein thrombosis, thrombocytosis, thromboembolic complications, sepsis, and wound complications (hematomas, seromas, and wound infections). Late complications include sepsis and splenosis [23, 24].

Sepsis:

Infectious complications are very common after splenectomy and are usually mild which can be managed conservatively with antibiotics. Overwhelming postsplenectomy infection (OPSI) is associated with high mortality rates despite adequate treatment. Vaccination 2 weeks prior to procedure for prevention of opportunistic infections (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Haemophilus influenzae) is advised. In cases of intraoperative decisions for splenectomy, a postoperative vaccination after two weeks is advised [25]. Influenza vaccine should be undertaken yearly. Patients developing infection, despite the above measures, should be admitted and administered systemic antibiotics.

General Concerns

Patients with low platelet count should have a platelet count maintained above 30,000 preoperatively and transfusion of platelets should be avoided until after surgery or during surgery after ligation of the splenic artery. If it is necessary to increase platelet count in these patients prior to surgery, usually a steroid bolus or parenteral IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin) can boost platelet count prior to surgery.

There is an increased risk of thrombosis and thrombocytosis after splenectomy (around 5%) which may cause thrombotic events such as acute myocardial infarction, mesenteric vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism [26]. Use of postoperative anticoagulant prophylaxis for oncosurgery patients is done routinely but it may increase the risk of hemorrhage.

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension may develop possibly due to reduced clearance of reticuloendothelial cells thereby causing increased circulating micro particle levels and thromboembolism and pulmonary hypertension in a dose-dependent fashion [27].

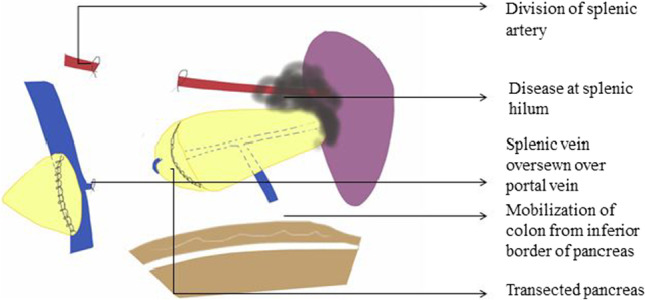

Distal Pancreatectomy with Enbloc Splenectomy

The pancreatic tail is anatomically proximal to the spleen. Distal pancreatectomy is a relatively uncommon procedure as a part of surgical debulking, but may be mandatory in a few cases to achieve optimal cytoreduction like splenic hilar metastases, pancreatic infiltration, or where there is an increased chance of damage to the pancreatic tail during splenectomy [22]. In usual circumstances, wherein the splenic hilum is involved, only a part of the tail of the pancreas is resected and the rest of the pancreas can be preserved, unlike a formal left pancreatic resection for pancreatic body/tail malignancy, where the entire body and pancreatic tail are removed by dividing the pancreas at the neck (RAMPS procedure—Radical Antegrade Modular Pancreaticosplenectomy) [28]. Usually, an abdominal drain is kept at the bed of the pancreas and managed conservatively.

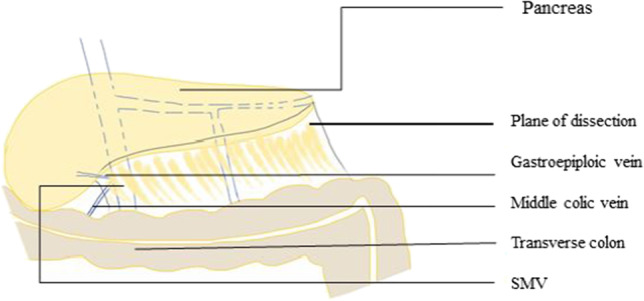

Operative Technique

The gastrocolic omentum is dissected and the pancreatic tail and body are exposed by displacing the omentum and colon along with mesocolon inferiorly away from the pancreas. The greater omentum is dissected up to the uppermost part by ligating the short gastric vessels. The posterior wall of the stomach is retracted superiorly after bluntly dissecting the adhesions between the stomach and pancreas [29–31]. Splenic flexure of the colon is mobilized and inferior border of the pancreas is delineated. The splenopancreatic block is fully mobilized and brought to the right. The splenic artery is identified at the superior border of the pancreas just proximal to the planned division of pancreatic parenchyma and doubly ligated before division (Figs. 15, 16). Formal identification of celiac axis and hepatic artery is not required for such distal resections and the splenic artery can safely be divided by staying to the left of the coronary vein (left gastric vein), at superior border of the pancreas. Also, for more safety, just before ligation, the splenic artery can be occluded by vascular clamp and hepatic artery pulsations are checked at porta hepatis, in order to prevent accidental hepatic artery ligation. If a larger part of the distal pancreas needs to be removed requiring pancreatic division at the neck, formal identification and dissection to safeguard hepatic artery is a must.

Fig. 15.

Technique of distal pancreaticosplenectomy (note: splenopancreatic block is mobilized and brought to the right)

Fig. 16.

Distal pancreaticosplenectomy with stapler transection of distal pancreatic end

The mobilized part of the distal pancreas is lifted and the splenic vein is dissected and ligated behind the pancreatic body at the same level as the splenic artery. The pancreas is then transected by either gastrointestinal/anastomosis (GIA) stapler with a vascular load or by electrocautery followed by over sewing with a non-absorbable suture to prevent risk of pancreatic fistula [13, 32]. The splenic vein can also be safely transected together with the pancreas by GIA stapler. Another method is transection of the pancreas by the ultrasonic dissector; during the transection procedure, even small pancreatic ducts and vessels are adequately exposed, tied proximally, and divided. The pancreatic stump is left open without parenchymal suturing.

Special attention to important anatomical structures depending on anatomical variation and extent of pancreatic resection is highlighted below.

- Middle colic vein and the inferior mesenteric veinThe IMV may be encountered while dissecting the posterior surface of the pancreas where it drains into the splenic vein. Similarly, middle colic vein which runs in the transverse mesocolon near the inferior border of the pancreas may be encountered during the medial portion of the dissection of the pancreatic neck (Fig. 17) [33].

Prevention:

The pancreatic tail should be dissected from distal towards the body and the splenic vein identified and separated carefully.

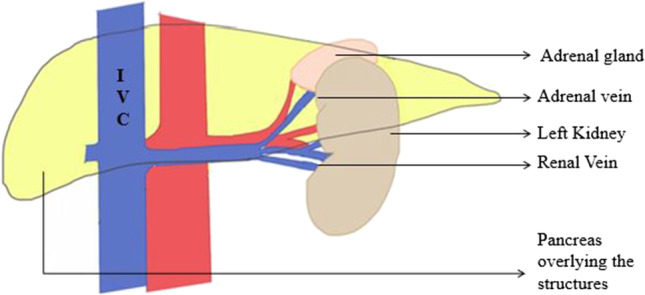

- Left renal vein and left adrenal veinThe left renal vein usually lies posterior to the inferior margin of the tail of the pancreas. The left adrenal vein enters the superior surface of the renal vein, and the adrenal gland can sometimes be adherent to the posterior capsule of the pancreas, which might make mobilization of the pancreas more difficult (Fig. 18). While reflecting the pancreas medially, the left renal vein, adrenal gland, or adrenal vein may get injured [33].Prevention:Careful dissection while medially reflecting the pancreas by maintaining the posterior avascular anatomic plane will prevent this complication.Repair:Repairing renal vein may require vascular control of the vein proximally and distally. This can be achieved by ligating left gonadal vein and the retroperitoneal collateral vein from the left renal vein in order to gain mobility for repair with good visualization.

- Right gastroepiploic vesselsA branch of the right gastroepiploic artery might communicate with the middle colic vessels inferior to the pylorus and while trying to elevate the stomach, it may get injured [33].

Prevention:

Maintaining an avascular plane while entering gastrocolic omentum and identifying and ligating these aberrant vessels while proceeding towards short gastric vessels may prevent this complication.

Fig. 17.

Middle colic vein and IMV

Fig. 18.

Left adrenal vein and pancreas

Complications

There are several reports of increased morbidity and mortality associated with distal pancreatic resection and thorough knowledge of anatomy of important vessels and management of complications is necessary.

- Pancreatic leak/fistula:Pancreatic leak is a relatively common complication that can occur after distal pancreatectomy in more than 30% of cases [34]. Awareness and understanding of pancreatic leaks allow for this complication to be diagnosed in a timely manner and successfully treated with minimal morbidity and minimal impact on the patient’s overall treatment course and outcome. Patients usually present with leukocytosis and abdominal pain. Leukocytosis may often be seen after splenectomy; however, if there are any other associated symptoms or if the white cell count dramatically increases after a downward trend, a CT (computed tomography) scan should be performed immediately to evaluate the upper abdomen [22, 34]. If fluid collection is seen, it should be drained to avoid worsening ongoing leakage and possible abscess formation. This fluid should be sent for an amylase level test for diagnosis.

The International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) defined postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) as any measurable drainage from an intraoperatively or postoperatively placed drain on or after postoperative day 3 with amylase content three times the normal serum amylase level. The ISGPS developed a grading system based on clinical criteria to define the severity of the fistula; grade A fistulae are transient and asymptomatic; grade B fistulae are clinically evident by symptoms and require intervention; and grade C fistulae have severe clinical manifestations and may require surgical re-exploration [35, 36]. Once the diagnosis of a pancreatic leak is made, continued drainage under antibiotic cover with close monitoring for signs and symptoms of sepsis is vital [22]. While grade A fistula generally resolve within 2 weeks, those with grade B fistula require 3 to 6 weeks for complete healing [35, 36]. Rarely, re-exploration may be needed to achieve optimal drainage. Patients can return to a regular diet after the diagnosis of a pancreatic leak as long as they appear to be improving (decreasing white blood cell count and no signs of sepsis) and as long as they do not display symptoms of ileus or obstruction.

There have been numerous reports of strategies to reduce the risk of pancreatic leak after distal pancreatectomy. Most of these techniques have been unsuccessful. The mainstay of treatment followed at most centers is closed-suction drainage of the pancreatic bed after surgery, the institution of a low-fat diet, and the judicious use of antibiotics to treat superinfection when it occurs [22, 34]. But studies have not shown any benefit from intraperitoneal suction drainage catheters placed at the time of surgery in reducing the rate of pancreatic leak. These drainage tubes are usually removed if the patient has no fever/upper abdominal pain after diet and there is minimum fluid in drainage tubes for more than 1 day or the value of amylase in drainage fluid is normal.

The rate of pancreatic fistula and leak is higher when transection occurs at the body rather than the neck of the pancreas. However, surgical technique may have a role in reducing the rate of pancreatic leak. Several resection methods and closure techniques of protecting the pancreatic remnant have been developed and are described below.

- Transection and closure techniques:Hand-sewn closure and stapler closure are the most commonly performed techniques for pancreatic remnant management but recent evidence does not show superiority of stapler closure over hand-sewn closure [39]. Conventional ligation of the main pancreatic duct with closure of the resected margin with sutures may leave these small branches open and allow them to leak. The staple method has the advantage of simplicity and speed. Dividing the pancreas using 2.5mm vascular staple cartridges rather than 4.5mm staple cartridges; gradual closing of the stapler over the course of about 2 to 3 min and reinforcement of a stapled transection line have been found to reduce the POPF rate [37, 38].

- Somatostatin analogues:Routine use or prophylactic administration of somatostatin or an analogue such as octreotide is controversial. It may decrease the volume of fistula output but does not result in earlier time to fistula closure [42, 43]. Their efficacy is reported to be improved, by selective administration in the setting of high-risk patients, including patients with a soft pancreatic gland or a small pancreatic duct, or patients in whom intraoperative blood loss was excessive.

- 2) Abdominal collection:Encapsulated effusion or the development of asymptomatic pancreatic pseudocyst does not always require special intervention, as the majority of such complications disappear spontaneously [32]. Left pleural effusion and atelectasis were treated by chest physiotherapy and drainage. Intra-abdominal abscess formation may occur in around 3% cases and is a frequent cause of re-hospitalization and usually requires drainage under adequate antibiotic cover.

- 3) Pancreatitis:This is a very rare complication after distal pancreaticosplenectomy. Acute pancreatitis may present as upper abdominal pain (acute onset of a persistent, severe, epigastric pain often radiating to the back) or raised levels of serum lipase and/or amylase at least three times the upper limit of normal or imaging (ultrasonography - USG) showing diffuse pancreatic edema [44]. An increase in the serum levels of pancreatic enzymes is often expected after pancreatectomy; thus, the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis might be a challenge. A CECT (contrast-enhanced computed tomography) may be done in cases of suspected leakage and an early diagnosis is vital to prevent SIRS (Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome) which may cause multi-organ failure and mortality. Early fluid infusion (Ringer’s lactate) and analgesics and anti-inflammatory agents are the standard of treatment for mild/moderate acute pancreatitis management. Although the ideal timing to initiate enteral feeding remains undetermined, administration within 48 h appears to be safe and tolerated.

- 4) Iatrogenic diabetes:New onset of diabetes mellitus (NODM) is a late complication of distal pancreatectomy and is diagnosed by oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) performed 6 months after surgery. Its incidence ranges between 14 and 39% depending on the extent of pancreatectomy and underlying quality of the pancreas [45].

- 5) Hemorrhage:Postoperative hemorrhage is one of the most feared complications and may have an underlying complication like pancreatic fistula [44]. Leaked pancreatic enzymes along with infection may erode the splenic artery stump, resulting in significant bleeding. An immediate re-intervention along with hemodynamic support with transfusion may be needed with angiographic embolization in the case of stable patients.

In non-gynecological literature, distal pancreatectomy may be associated with a postoperative morbidity close to 15% but when it comes to pancreatic tumoral involvement in the context of advanced stage or relapsed ovarian cancer, the surgeon often needs to perform multiple other associated visceral resections, some of them involving other upper abdominal viscera; therefore, the morbidity rate and other associated complications may vary, when compared to standard surgery for isolated pancreatic tumors [24, 46–48].

Conclusion

Approach to splenic hilar disease in advanced ovarian cancer is different from conventional splenectomy or DPS technique described in the literature. Even though the spleen and pancreas may largely look normal, surgical anatomy is distorted at the splenic hilum in many cases pulling the tail of the pancreas. The decision to perform splenectomy alone/distal pancreaticosplenectomy with or without resection of the transverse colon should be made before starting the dissection to prevent unnecessary hemorrhage and to save the surgical time. Hence, gynecological oncologists and surgical oncologists should be aware of the various surgical approaches in advanced ovarian cancer.

Author Contribution

TS Shylasree: technique/protocol development; literature search; manuscript writing/editing.

Pabashi Poddar: literature search; manuscript writing/editing.

Manish Bhandare: technique development and editing.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2014 - SEER Statistics. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2014/

- 2.Zivanovic O, Sima CS, Iasonos A, Hoskins WJ, Pingle PR, Leitao MMM, et al. The effect of primary cytoreduction on outcomes of patients with FIGO stage IIIC ovarian cancer stratified by the initial tumor burden in the upper abdomen cephalad to the greater omentum. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116(3):351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ang C, Chan KKL, Bryant A, Naik R, Dickinson HO. Ultra-radical (extensive) surgery versus standard surgery for the primary cytoreduction of advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Vol. 2011, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Wimberger P, Lehmann N, Kimmig R, Burges A, Meier W, Du Bois A. Prognostic factors for complete debulking in advanced ovarian cancer and its impact on survival. An exploratory analysis of a prospectively randomized phase III study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Ovarian Cancer Study Group (AGO-OVAR) Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106(1):69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shylasree TS, Howells REJ, Lim K, Jones PW, Fiander A, Adams M, et al. Survival in ovarian cancer in Wales: prior to introduction of all Wales guidelines. Vol. 16, International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer; 2006. p. 1770–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Lillemoe KD, Kaushal S, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ. Distal pancreatectomy: indications and outcomes in 235 patients. In: Annals of Surgery. Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 1999. p. 693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Fernández-Cruz L, Orduña D, Cesar-Borges G, López-Boado MA. Distal pancreatectomy: en-bloc splenectomy vs spleen-preserving pancreatectomy. Vol. 7, HPB. Taylor and Francis Ltd.; 2005. p. 93–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Rodeghiero F, Ruggeri M. Short- and long-term risks of splenectomy for benign haematological disorders: should we revisit the indications? Br J Haematol. 2012;158(1):16–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomes CA, Junior CS, Coccolini F, Montori G, Soares A, Junior CP, et al. Splenectomy in non-traumatic diseases What this review adds : 2018;11(5):295–304

- 10.Gemignani ML, Chi DS, Gurin CC, Curtin JP, Barakat RR. Splenectomy in recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;72(3):407–410. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghani AA, Hashmi ZA, Chase DM, Patel SB, Jones DF. Intraparenchymal metastases to the spleen from ovarian cancer: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:30. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun H, Bi X, Cao D, Yang J, Wu M, Pan L, et al. Splenectomy during cytoreductive surgery in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:3473–3482. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S172687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bacalbasa N, Balescu I, Dima S, Brasoveanu V, Popescu I. Pancreatic resection as part of cytoreductive surgery in advanced-stage and recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer - a single-center experience. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(7):4125–4130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Longnecker D. Anatomy and histology of the pancreas. Pancreapedia Exocrine Pancreas Knowl Base. 2014;1–26.

- 15.Chadburn A. The spleen: anatomy and anatomical function. Semin Hematol. 2000;37(1 SUPPL. 1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/S0037-1963(00)90113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaudhry SR, Panuganti KK. Anatomy, abdomen and pelivs, spleen. StatPearls: StatPearls Publishing; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Misiakos EP, Bagias G, Liakakos T, Machairas A. Laparoscopic splenectomy: current concepts. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;9(9):428. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i9.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Attri MR, Ahangar S, Bhardwaj R, Bashir MI. Laparoscopic spleenectomy. JK Sci. 2015;17(2):96–97. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vecchio R, Marchese S, Swehli E, Intagliata E. Splenic hilum management during laparoscopic splenectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2011;21(8):717–720. doi: 10.1089/lap.2011.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng CH, Xu M, Huang CM, Li P, Xie JW, Bin Wang J, et al. Anatomy and influence of the splenic artery in laparoscopic spleen-preserving splenic lymphadenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(27):8389–97. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i27.8389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taner T, Nagorney DM, Tefferi A, Habermann TM, Harmsen WS, Slettedahl SW, et al. Splenectomy for massive splenomegaly: long-term results and risks for mortality. Ann Surg. 2013;258(6):1034–1039. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318278d1bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bizzarri N, Bizzarri N, Korompelis P, Ghirardi V, Ghirardi V, O’donnell RL, et al. Post-operative pancreatic fistula following splenectomy with or without distal pancreatectomy at cytoreductive surgery in advanced ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020;1043–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Cadili A, de Gara C. Complications of splenectomy. Vol. 121, American Journal of Medicine. Elsevier; 2008. p. 371–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Dagbert F, Thievenaz R, Decullier E, Bakrin N, Cotte E, Rousset P, et al. Splenectomy increases postoperative complications following cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(6):1980–1985. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okabayashi T, Hanazaki K. Overwhelming postsplenectomy infection syndrome in adults - a clinically preventable disease. Vol. 14, World Journal of Gastroenterology. Baishideng Publishing Group Inc; 2008. p. 176–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Khan PN, Nair RJ, Olivares J, Tingle LE, Li Z. Postsplenectomy reactive thrombocytosis. Baylor Univ Med Cent Proc. 2009;22(1):9–12. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2009.11928458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McNeil K, Dunning J. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH). Vol. 93, Heart. BMJ Publishing Group; 2007. p. 1152–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Cao F, Li J, Li A, Li F. Radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy versus standard procedure in the treatment of left-sided pancreatic cancer: a systemic review and meta-analysis. BMC Surg. 2017;17(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s12893-017-0259-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Rooij T, Sitarz R, Busch OR, Besselink MG, Abu Hilal M. Technical aspects of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy for benign and malignant disease: review of the literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Di Donato V, Bardhi E, Tramontano L, Capomacchia FM, Palaia I, Perniola G, et al. Management of morbidity associated with pancreatic resection during cytoreductive surgery for epithelial ovarian cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46(4):694–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.11.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernández-Cruz L. Distal pancreatic resection: Technical differences between open and laparoscopic approaches. HPB. 2006;8(1):49–56. doi: 10.1080/13651820500468059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiang L, Tu Y, He T, Shen X, Li Z, Wu X, et al. Distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy for the management of splenic hilum metastasis in cytoreductive surgery of epithelial ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2016;27(6):62. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2016.27.e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitagawa H, Tajima H, Nakagawara H, Makino I, Miyashita T, Terakawa H, et al. A Modification of radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy for adenocarcinoma of the left pancreas: significance of en bloc resection including the anterior renal fascia. World J Surg. 2014;38(9):2448–2454. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2572-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kehoe SM, Eisenhauer EL, Abu-Rustum NR, Sonoda Y, D’Angelica M, Jarnagin WR, et al. Incidence and management of pancreatic leaks after splenectomy with distal pancreatectomy performed during primary cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian, peritoneal and fallopian tube cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(3):496–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomimaru Y, Noguchi K, Noura S, Imamura H, Iwazawa TKD. Factors affecting healing time and postoperative pancreatic fistula in patients undergoing pancreticoduodenectomy. Mol Clin Oncol. 2019;10(4):435–40. doi: 10.3892/mco.2019.1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.S Andrianello, G Marchegiani, E Bannone, P Vacca, A Esposito, L Casetti et al. Predictors of pancreatic fistula healing time after distal pancreatectomy. J hepatobiliarypancreatic Sci. 2020; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Grobmyer SR, Hunt DL, Forsmark CE, Draganov PV, Behrns KE, Hochwald SN. Pancreatic stent placement is associated with resolution of refractory grade C pancreatic fistula after left-sided pancreatectomy. Am Surg. 2009;75(8):654–657. doi: 10.1177/000313480907500804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyasaka Y, Mori Y, Nakata K, Ohtsuka T, Nakamura M. Attempts to prevent postoperative pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy. Vol. 47, Surgery Today. Springer Tokyo; 2017. p. 416–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Diener MK, Seiler CM, Rossion I, Kleeff J, Glanemann M, Butturini G, et al. Efficacy of stapler versus hand-sewn closure after distal pancreatectomy (DISPACT): a randomised, controlled multicentre trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1514–1522. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hassenpflug M, Hinz U, Strobel O, Volpert J, Knebel P, Diener MK, et al. Teres ligament patch reduces relevant morbidity after distal pancreatectomy (the DISCOVER Randomized Controlled Trial) Ann Surg. 2016;264(5):723–730. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sa Cunha A, Carrere N, Meunier B, Fabre JM, Sauvanet A, Pessaux P, et al. Stump closure reinforcement with absorbable fibrin collagen sealant sponge (TachoSil) does not prevent pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy: the FIABLE multicenter controlled randomized study. Am J Surg. 2015;210(4):739–748. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elliott IA, Dann AM, Ghukasyan R, Damato L, Girgis MD, King JC, et al. Pasireotide does not prevent postoperative pancreatic fistula: a prospective study. HPB. 2018;20(5):418–422. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2017.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allen PJ, Gönen M, Brennan MF, Bucknor AA, Robinson LM, Pappas MM, et al. Pasireotide for postoperative pancreatic fistula. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(21):2014–2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryska M, Rudis J. Pancreatic fistula and postoperative pancreatitis after pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2014;3(5):268–26875. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2014.09.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Bruijn KMJ, van Eijck CHJ. New-onset diabetes after distal pancreatectomy. Ann Surg. 2015;261(5):854–861. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McPhee JT, Hill JS, Whalen GF, Zayaruzny M, Litwin DE, Sullivan ME, et al. Perioperative mortality for pancreatectomy: a national perspective. Ann Surg. 2007;246(2):246–253. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000259993.17350.3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fahy BN, Frey CF, Ho HS, Beckett L, Bold RJ. Morbidity, mortality, and technical factors of distal pancreatectomy. Am J Surg. 2002;183(3):237–241. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(02)00790-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kleeff J, Diener MK, Z’graggen K, Hinz U, Wagner M, Bachmann J, et al. Distal pancreatectomy: risk factors for surgical failure in 302 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2007;245(4):573–82. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251438.43135.fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]