SUMMARY

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revealed that adult white adipose tissue (WAT) harbors functionally diverse subpopulations of mesenchymal stromal cells that differentially impact tissue plasticity. To date, the molecular basis of this cellular heterogeneity has not been fully defined. Here, we describe a multilayered omics approach to dissect adipose progenitor cell heterogeneity in three dimensions: progenitor subpopulation, sex, and anatomical localization. We applied state-of-the-art mass spectrometry methods to quantify 4870 proteins in eight different stromal cell populations from perigonadal and inguinal WAT of male and female mice and acquired transcript expression levels of 15477 genes using RNA-seq. Our data unveil molecular signatures defining sex differences in preadipocyte differentiation and identify regulatory pathways that functionally distinguish adipose progenitor subpopulations. This multilayered omics analysis, freely accessible at http://preadprofiler.net, provides unprecedented insights into adipose stromal cell heterogeneity and highlights the benefit of complementary proteomics to support findings from scRNA-seq studies.

Keywords: Multilayered omics, cellular heterogeneity, adipocyte precursor cells, adipogenesis, adipose tissue, PPARγ, inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Adipose tissue is exceptional in its ability to adapt to changes in physiological, pathophysiological, and environmental conditions. The condition of obesity highlights an unparalleled capacity of white adipose tissue (WAT) to expand in size in the face of positive energy balance. This adaption to increased demand for energy storage is critical in order to maintain adequate lipid storage in WAT rather than deleterious ectopic lipid deposition in non-adipose tissues (Hepler and Gupta, 2017). WAT expansion in obesity occurs in a sex- and region-dependent manner (Karastergiou et al., 2012). Preferential expansion of gluteo-femoral subcutaneous WAT depots, often observed in females, is associated with protection against metabolic abnormalities (Lotta et al., 2018). Preferential accumulation of visceral WAT, more often observed in males, is maladaptive and linked to insulin resistance (Carey et al., 1997; Chan et al., 1994).

The expansion and remodeling of WAT is heavily regulated by non-parenchymal cells that constitute the WAT microenvironment. Recent single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) efforts have revealed the cellular heterogeneity of mesenchymal stromal cells and immune cells of the adipose stromal-vascular fraction (SVF) (Burl et al., 2018; Goldberg et al., 2020; Hepler et al., 2018; Merrick et al., 2019; Rabhi et al., 2020; Rajbhandari et al., 2019; Sarvari et al., 2021; Schwalie et al., 2018; Spallanzani et al., 2019; Vijay et al., 2020; Zhong et al., 2020). Notably, many of these studies identified stromal cell subpopulations that differentially impact adipose tissue homeostasis in adulthood. Our own recent efforts have focused on functionally distinct subpopulations of PDGFRβ+ cells within WAT, many of which reside within the vasculature and exhibit properties of mural cells (Hepler et al., 2018; Shan et al., 2020; Shao et al., 2021). We identified and characterized two functionally distinct fibro-inflammatory and adipogenic PDGFRβ-expressing perivascular cell subpopulations in perigonadal WAT (gWAT) of adult mice (Hepler et al., 2018). Fibro-inflammatory precursors (LY6C+ PDGFRβ+ cells), or “FIPs”, exert strong pro-inflammatory, pro-fibrotic, and anti-adipogenic phenotypes. FIPs are activated upon high-fat diet (HFD) feeding and play an important role in controlling metabolic inflammation of WAT associated with obesity (Shan et al., 2020). The phenotype of FIPs is in sharp contrast to the LY6C− CD9− PDGFRβ+ subpopulation which represents adipocyte precursor cells, or “APCs”. APCs highly express Pparg and other pro-adipogenic genes and possess robust adipogenic capacity both in vitro and in vivo (Hepler et al., 2018; Peics et al., 2020). Moreover, we have identified significant WAT-depot differences in the heterogeneity of PDGFRβ+ progenitor cells (Joffin et al., 2021; Shao et al., 2021). In inguinal WAT (iWAT), two predominate clusters of PDGFRβ+ cells are readily apparent and can be defined and isolated on the basis of DPP4 expression. scRNA-seq analysis suggest that iWAT DPP4+ PDGFRβ+ cells and DPP4− PDGFRβ+ cells bear molecular resemblance to gWAT FIPs and APCs, respectively. However, functional analyses highlight significant depot-differences in progenitor cell heterogeneity that are not fully appreciated by the transcriptional profiling approach of scRNA-seq alone (Joffin et al., 2021; Shao et al., 2021). Our analyses, along with earlier work from Merrick et al., suggest that iWAT DPP4+ PDGFRβ+ cells and DPP4− PDGFRβ+ cells represent hierarchical APC populations, where multipotent DPP4+ APCs give rise to more committed DPP4− APCs that are enriched in the expression of Pparg (Merrick et al., 2019). Importantly, there are significant differences in the depot-specific responses of committed APCs to HFD feeding, which underlies their propensities to undergo adipogenesis in vivo (Joffin et al., 2021; Shao et al., 2021). Moreover, we recently reported that DPP4+ APCs regulate cold-induced thermogenic remodeling of iWAT by coupling β-adrenergic receptor signaling to the activation of immune cells. In particular, cold exposure drives striking transcriptomic changes selectively within the DPP4+ subpopulation of APCs, including β-adrenergic receptor/CREB mediated induction in the expression of the pro-thermogenic cytokine, Il33 (Shan et al., 2021).

Despite the feasibility of using scRNA-seq to address adipose tissue stromal cell complexity and heterogeneity at the transcript level, several studies from other fields highlight the potential benefit of a deeper characterization of adipose progenitor subpopulations through the use of multilayered omics approaches. Importantly, transcript levels alone are not sufficient to predict the corresponding protein levels in many scenarios. A moderate protein-mRNA correlation was reported in yeast (Gygi et al., 1999) and observed in several organisms including Caenorhabditis elegans (Grun et al., 2014), Drosophila melanogaster (Casas-Vila et al., 2017), mice (Williams et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2014) and humans (Zhang et al., 2014). Gene expression at multiple levels and its significance in determining adipose stromal cell heterogeneity and function remain largely unknown. This is partly due to the technical limitation in precise and reproducible protein quantification from very limited amounts of samples. Recently, data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry (DIA-MS) was developed and has demonstrated the ability to quantify thousands of proteins with high degree of reproducibility and accuracy across large sample cohorts (Collins et al., 2017; Gillet et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2016). We reasoned that use of this technology would enable a large-scale multi-omics dissection of gene expression in subpopulations of adipose tissue stromal cells and would shed further insight into the functional heterogeneity of adipose stromal cells.

Here, we describe a comprehensive and integrated dataset that details the transcriptomic and proteomic heterogeneity of adipose tissue progenitors in three dimensions: cell type (WAT PDGFRβ + stromal cell subpopulations), anatomical localization (visceral and subcutaneous adipose depots), and sex (male and female mice). We find that expression levels of transcripts have a nominal yet statistically significant correlation with their protein counterparts. Importantly, for several key pathways, we found that the proteomic layer reflects cellular function in a more robust way compared with the transcriptomic layer. We provide proof-of-concept that insight into the molecular mechanisms controlling the adipogenic and pro-inflammatory responses of adipose progenitor subpopulations can be inferred from these data, along with potential mechanisms underlying sex-differences in progenitor cell activity. These data are publicly available at http://preadprofiler.us-east-2.elasticbeanstalk.com/ in a user-friendly search engine we refer to as the “PreadProfiler.” Together, our findings demonstrate the complementarity of multilayered omics, and highlight the power of integrated transcriptomic and proteomic analyses to provide insight into the molecular basis of cellular heterogeneity.

RESULTS

Proteomics reveals adipose tissue progenitor cell heterogeneity

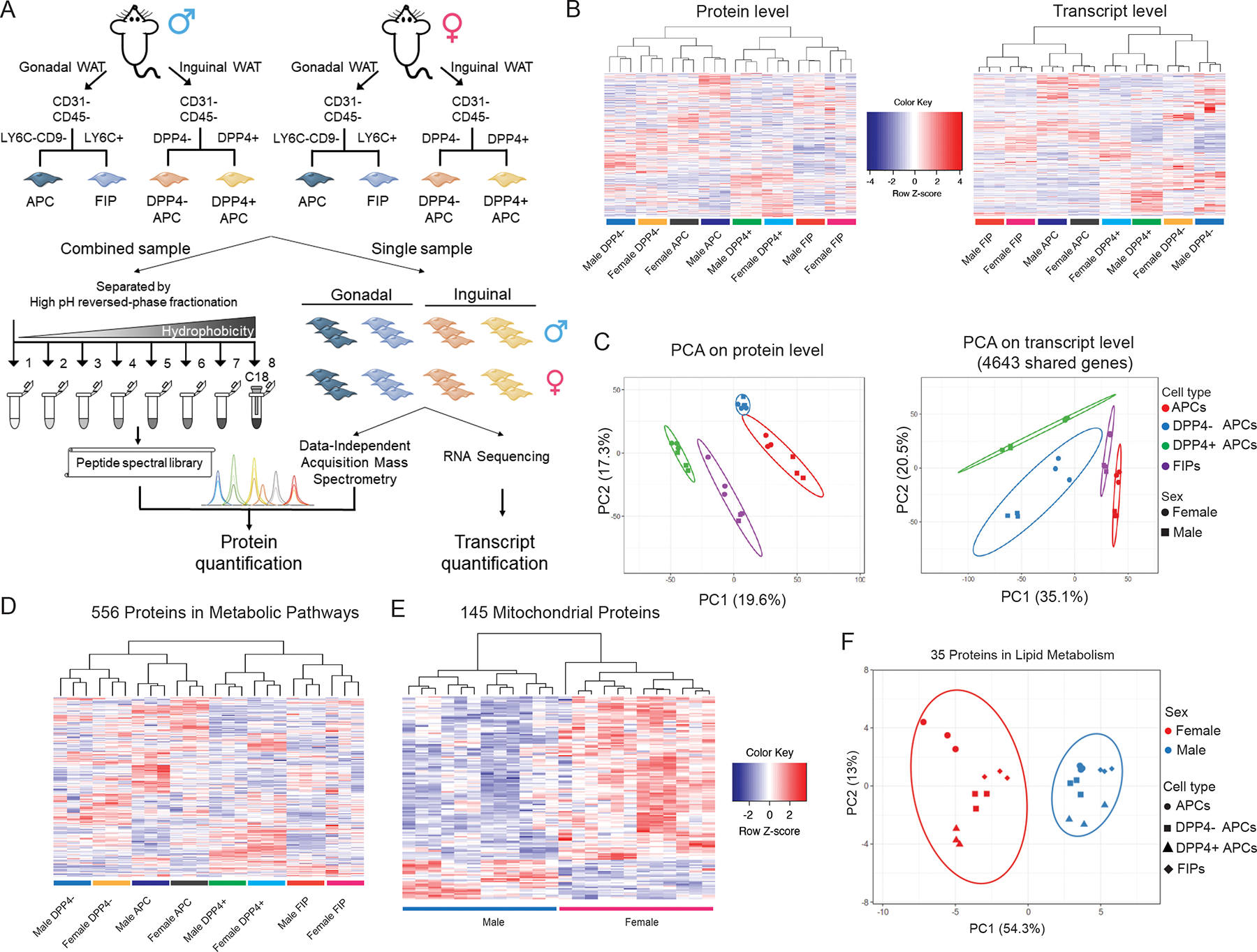

Our objective was to gain deeper insight into the cellular heterogeneity of adipose progenitor cells, with consideration of the apparent depot- and sex-differences in progenitor cell function and regulation in vivo. To this end, we isolated the four characterized PDGFRβ + cell subpopulations from male and female mice WAT using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). This includes adipocyte precursor cells (APCs) and fibro-inflammatory progenitors (FIPs) from intraabdominal gWAT, and DPP4− APC and DPP4+ APC subpopulations from subcutaneous iWAT. Importantly, these are the four progenitor subpopulations that have been identified by several groups as the predominant progenitor subpopulations in murine iWAT and gWAT (Rondini and Granneman, 2020). We then performed a multilayered omics analysis of the isolated populations (Figure 1A). We utilized DIA-MS to measure protein levels in 24 samples representing the eight cell subpopulations. This approach allowed us to quantify 4870 unique proteins across all 24 samples with reproducibility among three biological replicates within respective groups (average coefficient of variation [CV] = 15.3%, Figure S1A, Table S1). Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed an unbiased coverage of proteins from membrane, cytoplasm, nucleus and other subcellular organelles (Figure S1B). In addition, we performed bulk RNA-seq for the same eight groups of cells and quantified 15477 transcripts with their corresponding protein sequences manually annotated in the UniProt Knowledgebase across all groups (Table S2).

Figure 1. Multilayered omics reveal adipose tissue progenitor cell heterogeneity.

(A) Overview of the multilayered omics approach to dissect molecular signatures of adipose tissue stromal cell populations.

(B) Heat maps depicting protein levels (left) and transcript levels (right) across all 24 samples. Data were normalized to total abundance in each sample and z-score transformed. Red represents a z-score larger than 0 and blue represents a z-score smaller than 0.

(C) Principal component analysis based on proteomics (left) and transcriptomics (right) data.

(D) Sample clustering based on the expression of 556 proteins involved in metabolic pathways as annotation by GO. Data were normalized to total abundance in each sample and z-score transformed. Red represents a z-score larger than 0 and blue represents a z-score smaller than 0.

(E) Sample clustering based on the expression of 145 proteins under the GO term Cellular Component ‘mitochondrion’ that were significantly regulated by sex (ANOVA adjusted p value < 0.05).

(F) Principal component analysis of male and female populations based on expression of 35 proteins under the GO term Biological Process ‘lipid metabolic process’ that were significantly regulated by sex (ANOVA adjusted p value < 0.05).

We performed unsupervised clustering and principal component analysis (PCA) on the basis of either protein expression or transcript levels. The 24 samples clustered into 8 distinct groups as expected; however, the manner in which they clustered and separated from one another differed based on protein abundances or mRNA levels. Consistent with our previous work, and analogous work from others, clustering of cell populations based on transcript levels was driven by their inherent depot-dependent differences in gene expression (Burl et al., 2018; Shao et al., 2021). In other words, gWAT APCs were more similar to gWAT FIPs than they were to iWAT APC populations at the transcript level. Thus, the clustering predominately reflected their anatomical origin rather than functional properties. Clustering on the basis of the 4870 proteins quantified also separated all samples into 8 distinct groups (Figure 1B). Notably, we observed substantial differences in protein expression across subpopulations with a low degree of variance within respective groups. Interestingly, gWAT APCs and iWAT DPP4− APCs clustered closely together at the protein level, which correlated with their shared function as committed preadipocytes in their respective depots. gWAT FIPs and iWAT DPP4+ APCs appeared as distinct clusters that appear more similar to one another, rather than their counterparts in their respective depots (Figure 1C). Thus, gene expression at the protein level appears to better reflect the functional heterogeneity of the different cell populations, rather than the depot of origin or sex.

Among the 4870 quantified proteins, 3444 (70.7%) proteins were differentially expressed (ANOVA adjusted p value < 0.05) among the eight populations, and 2708 (55.6%) proteins discriminated functionally distinct cell populations (Figure S1C). We performed two-group comparisons and found that 1068 proteins differed in their expression between APCs and FIPs, and 1391 proteins were differently expressed between DPP4− APC and DPP4+ APC populations, with 522 proteins shared by these two lists (Figure S1D). To evaluate the impact of sex and depot on protein expression, we grouped the samples into male vs. female, or visceral vs. inguinal populations. For the 2014 proteins that were differently expressed between populations from visceral and subcutaneous WAT, 976 (48.5%) were regulated exclusively in the depot dimension. Interestingly, 506 (94.2%) out of 537 proteins that could distinguish male and female stromal cells were also significantly regulated in other dimensions (Figure S1D). This suggests that a small subset of proteins may play a unique role in defining the differences between male and female progenitor cell populations.

Recently, Joffin et al. reported that PDGFRβ+ progenitor subpopulations in WAT differ substantially in their metabolic activity, and that the adipogenic vs. pro-inflammatory phenotypes of these cells are strongly regulated by mitochondrial metabolism (Joffin et al., 2021). Of the 4870 proteins quantified in our analysis, 556 proteins were annotated as proteins related to metabolism. Interestingly, all sample groups can be distinguished by abundances of these 556 proteins, further indicating a fundamental difference in metabolism among these subpopulations in the steady state (Figure 1D). In addition, GO analysis of proteins significantly regulated by sex (ANOVA adjusted p value < 0.05) revealed notable sex-dependent differences in the expression of mitochondrial proteins and regulators of lipid metabolism. In particular, expression of 145 proteins annotated in GO term Cellular Component ‘mitochondrion’ clearly separated male vs. female populations, with most of them highly expressed in female progenitor cells (Figure 1E). Similarly, expression of 35 proteins that were annotated in GO term Biological Process ‘lipid metabolic process’ clearly segregated the 24 samples according to sex (Figure 1F). Moreover, we observed that the expression of many of the proteins directly involved in glutathione metabolism was selectively increased in male gWAT APCs, and that the abundance of these particular proteins could readily distinguish these cells from all other populations (Figure S1E). Taken together, integrated omics analyses provide deeper insight into the sex- and depot-dependent differences in the molecular and functional heterogeneity of adipose progenitor cells.

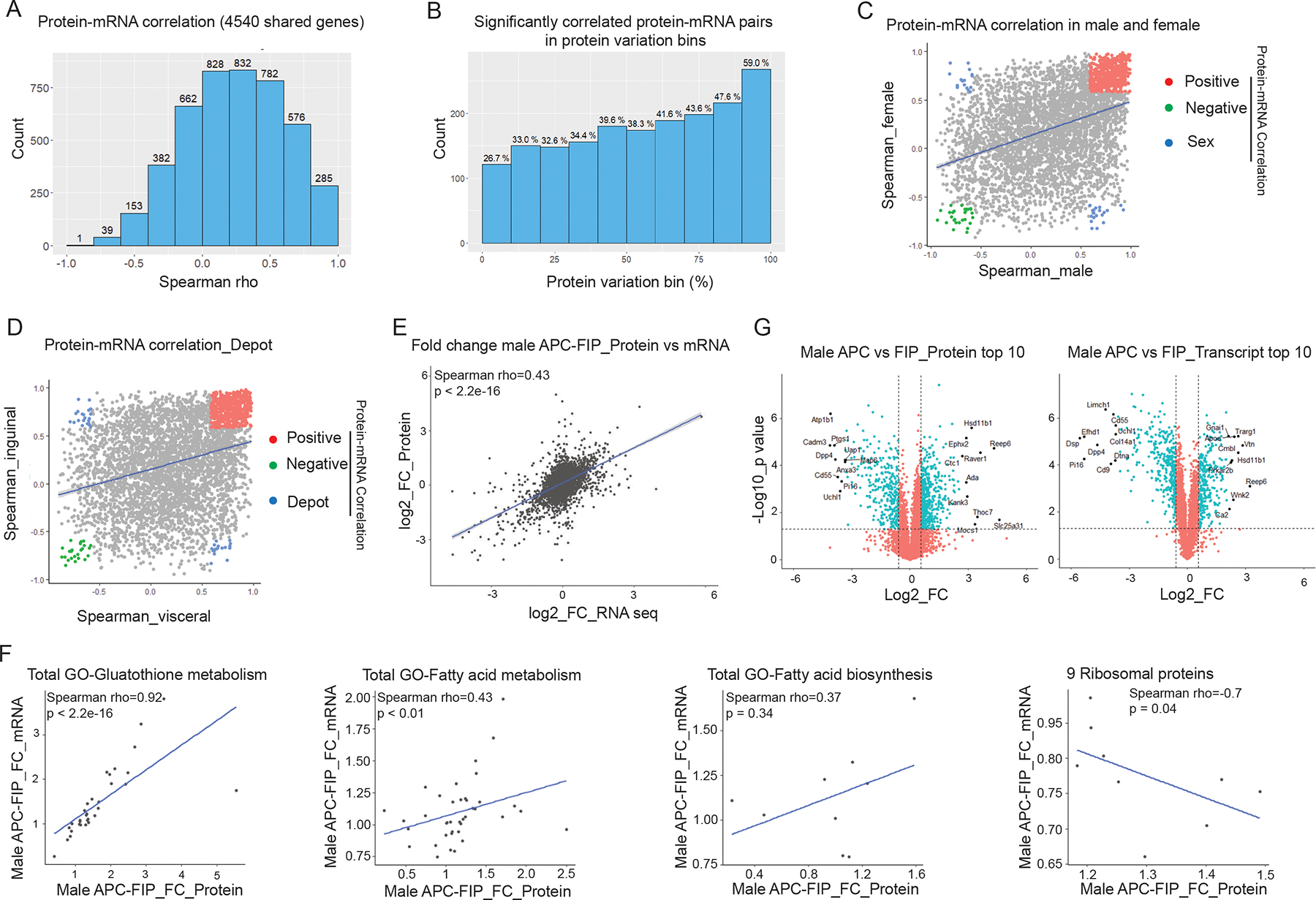

Multilayered omics reveal protein-mRNA correlation in isolated adipose stromal cells

Previous studies have mainly focused on protein-mRNA correlation in bulk tissue, yet little was known about their correlation in specific cell populations or subsets and in multiple dimensions. Integrating transcriptomic and proteomic datasets allowed us to examine the correlation between protein levels and mRNA levels within distinct progenitor cell subpopulations. Of the 4870 proteins quantified in all samples, transcript levels were available for 4643. Among these, 4638 transcripts were quantified in at least 2 samples, and 4540 transcripts were quantified in all 24 samples. We performed Spearman correlation analysis for these 4540 protein-mRNA pairs both across all 24 samples and in pairwise population comparisons. 1800 protein-mRNA pairs correlate at nominal significance (p < 0.05), while 2740 pairs have no significant correlation (Figure 2A). We observed an average Spearman’s correlation efficient (Spearman’s rho) = 0.24 across all samples, which is similar to protein-mRNA correlation in mouse tissue samples reported in a mouse genetic reference population (Williams et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2014). Variation of protein or transcript levels across samples were highly distinct for different gene sets. Thus, we binned the 4540 shared genes quantified in all samples at both levels into 10 groups based on their CV of protein abundances across all samples. We found that the protein-mRNA correlation is strongly related to the variance of protein levels (Figure 2B, Figure S2). The percentage of significantly correlated protein-mRNA pairs increased steadily with increasing CV of protein levels across all samples, with 26.7% in the group of the lowest variable proteins, and 59.0% in the group with the highest protein variability. Consistent with this, protein-mRNA correlation also significantly correlated with variability on transcript levels (Spearman’s rho = 0.37, p < 2.2e-16). These findings suggest that the correlation between protein and mRNA levels is highly influenced by abundance variabilities at both protein and transcript levels.

Figure 2. Protein-mRNA correlation in adipose progenitor cell populations.

(A) Histogram of Spearman’s correlation coefficients (Spearman’s rho) of the 4540 protein-mRNA pairs across all samples.

(B) Spearman’s rho prevalence of 4540 protein-mRNA pairs binned by protein variation. Y-axis shows the number of significantly correlated pairs in each bin. Numbers above the bars represent the percentages of the significantly correlated pairs out of the 454 protein-mRNA pairs in each bin.

(C) Correlation of Spearman’s rho in male vs. female populations. Colored dots represent protein-mRNA pairs with significant correlation in both male and female populations (p < 0.05). Red: positive protein-mRNA correlation. Green: negative protein-mRNA correlation. Blue: protein-mRNA correlation positive in one sex, but negative in the other.

(D) Correlation of Spearman’s rho in visceral vs. inguinal populations. Colored dots represent protein-mRNA pairs with significant correlation in both visceral and inguinal populations (p < 0.05). Red: positive protein-mRNA correlation. Green: negative protein-mRNA correlation. Blue: protein-mRNA correlation positive in one depot, but negative in the other.

(E) Correlation of fold changes (FC) between male APCs and FIPs at protein and mRNA levels.

(F) Protein-mRNA correlation in representative pathways and gene sets. Correlation plots of male APCs vs. FIPs fold changes of genes involved in the indicated pathways.

(G) Volcano plot depicting differences between male APCs and FIPs at the protein level (left) and transcript level (right). Top 10 significantly regulated (fold change) genes on each layer are labeled with gene names.

We also estimated protein-mRNA correlation in male and female populations separately. Among the 4540 protein-mRNA pairs, 1517 protein-mRNA pairs correlated at nominal significance in male populations while 1160 pairs correlated in female populations, and 626 pairs correlated at p < 0.05 in both sexes (Figure 2C). Interestingly, of these 626 genes, a majority of 562 protein-mRNA pairs were positively correlated, 28 pairs were negatively correlated in both sexes, while 36 pairs showed opposite correlation between male and female populations. This included 14 proteins in the extracellular exosome and 7 proteins in the Golgi apparatus. In addition, 1425 pairs correlated at nominal significance in one sex but not the other, indicating a sex-dependent regulation on protein-mRNA correlation. Protein-mRNA correlations were similarly influenced by depot of origin (Figure 2D). 758 protein-mRNA pairs correlated (p < 0.05) only in the visceral populations while 720 pairs correlated only in the inguinal populations. Out of the 592 protein-mRNA pairs that were correlated at a permissive significance (p < 0.05) in both visceral and inguinal WAT populations, 528 pairs showed positive correlation, 25 pairs were negatively correlated, while 39 pairs showed a depot-dependent correlation. Interestingly, only 3 genes (Mfn2, Ppp4r3a, wSf3b4) were shared between the two lists of genes that showed opposite correlation across sexes or depots, suggesting that different mechanisms underlie differential gene expression in the dimensions of sex or depot.

We then estimated correlation of fold changes between two cell populations at protein and mRNA levels. Comparing male APCs and FIPs, we observed a moderate yet significant protein-mRNA correlation [Spearman’s rho = 0.43, p < 2.2E-16] between these two populations (Figure 2E). Interestingly, protein-mRNA correlation not only related to variance on each layer, but also varied depending on the specific pathway analyzed. For the 32 genes involved in glutathione metabolism, their protein expression levels significantly correlated with their transcript levels (Spearman’s rho = 0.92, p < 2.2E-16) (Figure 2F). Similarly, genes involved in fatty acid metabolism showed a protein-mRNA correlation of Spearman’s rho 0.43 (p < 0.01). On the other hand, genes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis did not have a significant correlation between their protein and transcript levels. Moreover, for some pathways and gene sets (e.g., 9 ribosomal proteins), protein and mRNA levels were negatively correlated with statistical significance (p = 0.04) (Figure 2F).

We then compared expression levels of the 4572 shared genes that were quantified in all replicates of male APCs and FIPs on both omics layers (Figure 2G). Using a cutoff of 1.5-fold change, 757 genes were significantly regulated at the protein level (t-test p value < 0.05), with 454 proteins significantly upregulated in APCs and 303 proteins significantly upregulated in FIPs. At the transcript level, 626 genes were significantly expressed between these two populations, with 280 transcripts upregulated in APCs and 346 transcripts upregulated in FIPs. Interestingly, for the 454 genes that were upregulated in the APCs at the protein level, only 139 genes were also upregulated at the transcript level. While 49.6% of the increased transcripts resulted in upregulation of their corresponding proteins, increases of 315 proteins could not be predicted from their transcript counterparts. Similarly, only 56.1% of the genes upregulated in FIPs at the protein level showed a significant increase in their corresponding transcript levels. By comparing the genes with the most significantly altered expression levels on each layer, we found that only 2 genes were shared among the top 10 up-regulated genes (Hsd11b1 and Reep6) in APCs at both protein and mRNA levels, and 4 genes were shared among the top 10 down-regulated genes (Cd55, Dpp4, Pi16 and Uchl1). These observations indicate that transcript levels are not always a good proxy for predicting abundances of their proteins, and multilayered-omics data have provided additional information that cannot be obtained from a single layer alone.

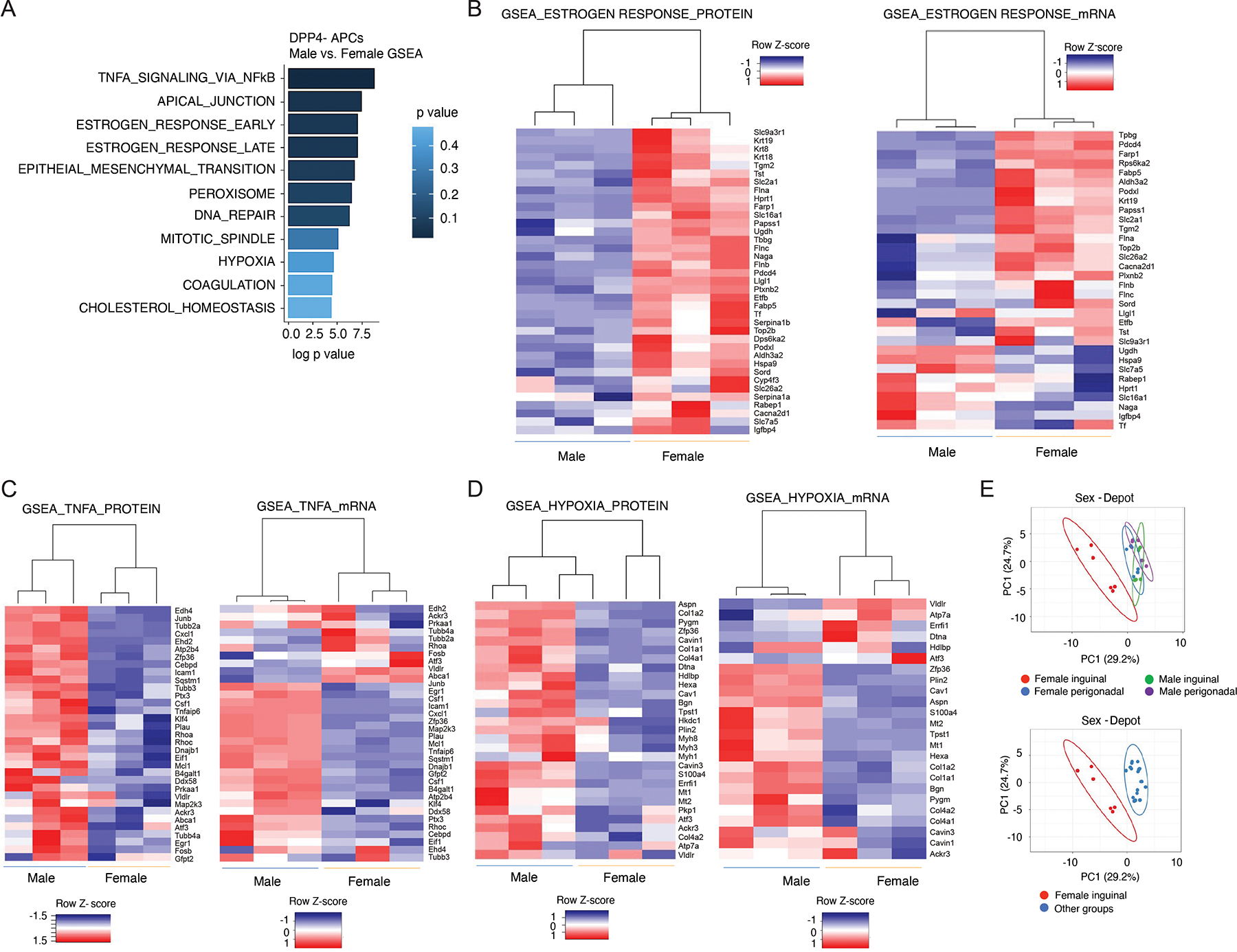

Differential PPARγ phosphorylation underlies sex differences in iWAT APC differentiation

Our data indicate that 11.0% of the translationally active genes in the analyzed precursor cells exhibit sex-dependent expression (ANOVA adjusted p value < 0.05). This observation is notable given the well-known sex-dependent expansion of subcutaneous WAT in obesity. Adipocyte turnover studies also revealed sex-dependent activation of APCs in iWAT of mice following HFD (60% kcal from fat) feeding (Jeffery et al., 2016). In male mice, iWAT APCs are resistant to undergoing adipogenesis upon HFD feeding whereas gWAT APCs are activated to undergo differentiation (Kim et al., 2014; Shao et al., 2018; Vishvanath et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2013). In female mice, de novo adipogenesis can be observed in both iWAT and gWAT following HFD feeding (Jeffery et al., 2016). This suggests that there are key sex differences between male and female committed DPP4− APCs. Indeed, pathway analysis of the proteomic dataset revealed notable differences in the expression of proteins reflective of several pathways relevant to WAT remodeling, including “Estrogen Response,” “TNFα signaling via NFκB,” and “hypoxia” (Figure 3A, Table S3). Closer inspection of these data revealed that the differential expression of these molecular signatures was more readily apparent and consistent at the protein level than at the mRNA level (Figure 3B–D). Our proteomics analysis captured 37 proteins whose expression was reflective of early and late estrogen response; nearly all of these proteins were expressed at higher levels in female inguinal DPP4− APCs than in male DPP4− APCs (Figure 3B). Notably, levels of these proteins clearly distinguished female iWAT populations from female gWAT populations and all male populations (Figure 3E).

Figure 3. Proteomic data highlight the sex differences in iWAT committed APCs.

(A) Gene signatures enriched in male vs. female DPP4− APCs based on proteomics dataset.

(B) Heat maps depicting protein expression (left) and mRNA expression (right) of an “estrogen response” signature in male and female committed DPP4− APCs.

(C) Heat maps depicting protein expression (left) and mRNA expression (right) of a “TNFα signaling” signature in male vs. female DPP4− APCs.

(D) Heat maps depicting protein expression (left) and mRNA expression (right) of “hypoxia” gene signature in male vs. female DPP4− APCs.

(E) Principal component analysis showing separation of female iWAT populations from the rest of the populations based on expression of proteins represented in the “estrogen response” signature.

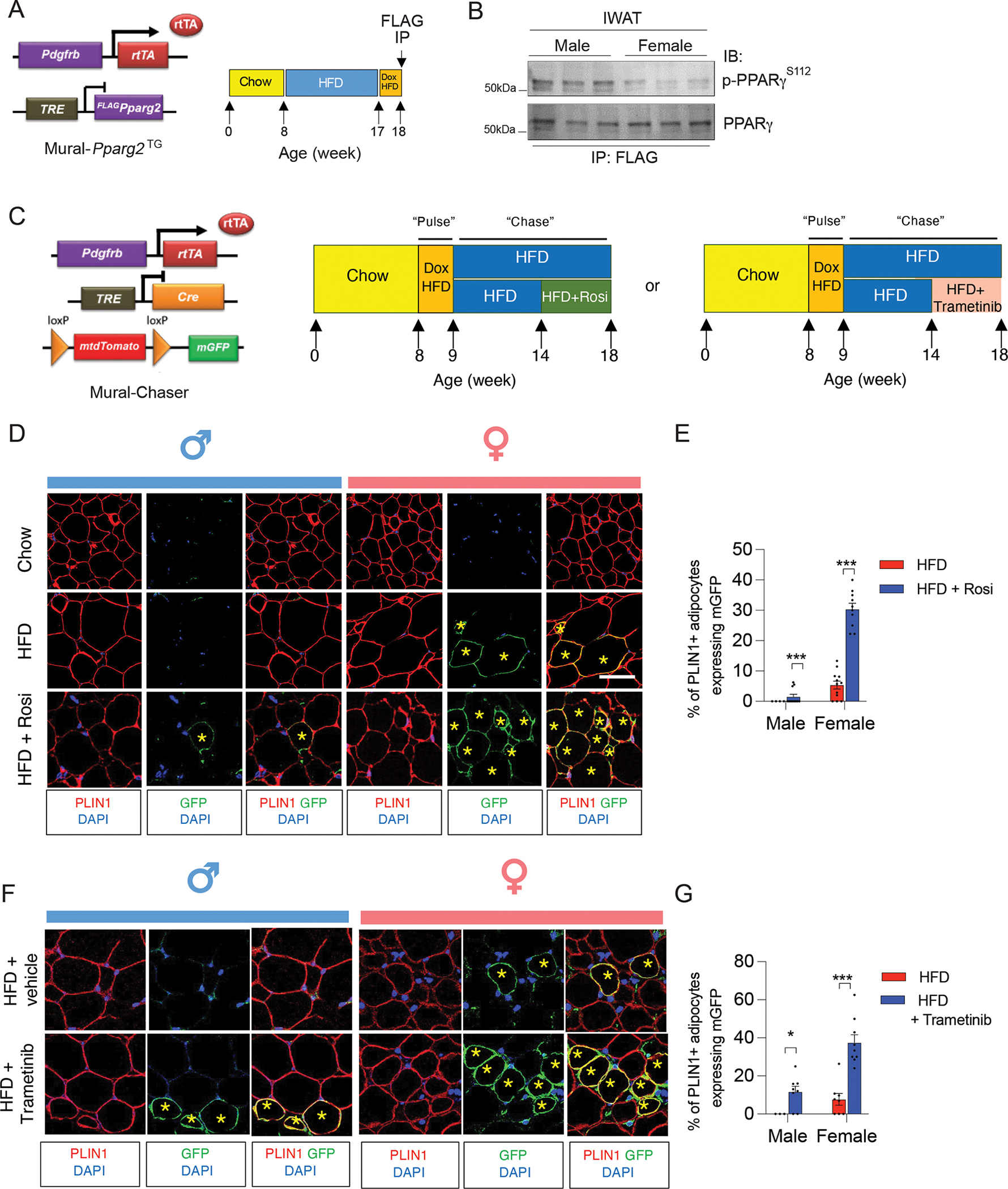

The enrichment of a gene signature reflective of “Hypoxia” in male DPP4− APCs vs. female DPP4− APCs is notable given our recent study highlighting the inhibitory effect of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) signaling on the activity of PPARγ, the master regulator of adipogenesis (Shao et al., 2021). HIF1α activation within adipose progenitors triggers a PDGFR signaling cascade leading to inhibitory serine 112 (S112) phosphorylation of PPARγ. Levels of PPARγ S112 phosphorylation in WAT PDGFRβ+ cells are depot-dependent and controlled by HIF1α signaling (Shao et al., 2021). The degree of inhibitory PPARγ S112 phosphorylation in iWAT progenitor cells is higher in comparison to levels in gWAT PDGFRβ+ cells. Thus, levels of PPARγ S112 phosphorylation in adipose progenitors inversely correlate with their capacity for adipogenesis upon HFD feeding. The sex difference in the “hypoxia” signature suggests that differences in the degree of PPARγ S112 phosphorylation may also underlie sex differences in PPARγ activity of APCs. To address this, we utilized our previously described “Mural-PpargTG” mice, which express FLAG epitope-tagged PPARγ2 in PDGFRβ+ cells in a doxycycline (Dox)- inducible manner (Figure 4A) (Shao et al., 2018). We placed 8-week-old male and female Mural-PpargTG mice on a HFD for 9 weeks and then switched animals to Dox-containing HFD for 7 days (Dox-HFD). Following 7 days of transgene expression, we assayed PPARγ S112 phosphorylation by western blotting of immunoprecipitated FLAG-tagged PPARγ protein (anti-FLAG antibody) from isolated iWAT depots. This allowed us to assess PPARγ S112 phosphorylation specifically in PDGFRβ+ cells of iWAT. After HFD feeding, the levels of phosphorylated PPARγ in female iWAT PDGFRβ+ cells were appreciably lower than in male iWAT progenitors (Figure 4B). This suggests that there are sex-differences in the activity of PPARγ within APCs in the setting of diet-induced obesity.

Figure 4. Sex differences in progenitor levels of PPARγ S112 phosphorylation and adipogenic potential in vivo.

(A) Approach to assay PPARγ S112 phosphorylation in iWAT of obese male and female mice: Doxycycline (Dox)-inducible Mural-Pparg2TG mice were fed a standard chow diet until 8 weeks of age before being switched to HFD feeding for another 9 weeks. Following HFD-feeding, male and female Mural-Pparg2TG mice were fed with Dox-HFD for another 7 days to induce the expression of FLAG-tagged Pparg2 transgene in PDGFRβ+ cells. FLAG-tagged PPARγ protein was then immunoprecipitated from whole depots using anti-FLAG antibodies for western blot analysis.

(B) Western blot analysis of PPARγ S112 phosphorylation in PDGFRβ+ cells of iWAT of male and female Mural-Pparg2TG mice as described in (A).

(C) “Pulse-chase” lineage tracing analysis: MuralChaser mice were maintained on a standard chow diet until 8 weeks old before being switched to Dox-HFD feeding for 7 days (“pulse”). Following the Dox administration, male and female MuralChaser mice were switched to regular HFD (no Dox) for an additional 9 weeks (“chase”) before iWAT samples were harvested for immunofluorescence staining. During the last 4 weeks of HFD feeding, animals were administered either Rosiglitazone (via diet), Trametinib (via oral gavage, 3 mg/kg body weight every two days), or the appropriate vehicle.

(D) Representative confocal immunofluorescence images of GFP (green) and PLIN1 (red) expression in iWAT from male and female obese MuralChaser mice maintained on HFD feeding with or without Rosiglitazone. Asterisks indicate GFP+ adipocytes, which represent newly formed fat cells. Scale bar = 50 μm.

(E) Quantification of the frequency of GFP+ adipocytes (PERILIPIN+) in iWAT depots from male and female mice maintained on HFD feeding with or without Rosiglitazone. Bars represent mean + s.e.m. Male mice, n= 4 for HFD, n=10 for HFD+Rosi; Female mice, n=12 for HFD, n=10 for HFD+Rosi. *** denotes p value <0.001 by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

(F) Representative confocal immunofluorescence images of GFP (green) and PLIN1 (red) expression in iWAT from male and female obese MuralChaser mice maintained on HFD feeding with or without Trametinib. Asterisks indicate GFP+ adipocytes, which represent newly formed fat cells. Scale bar = 50 μm.

(G) Quantification of the frequency of GFP+ adipocytes (PERILIPIN+) in iWAT depots from male and female mice maintained on HFD feeding with or without Trametinib. Bars represent mean + s.e.m. Male mice, n= 3 for HFD, n=8 for HFD+Trametinib; Female mice, n=8 for HFD, n=9 for HFD++Trametinib. * denotes p value <0.05, *** denotes p value <0.001 by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

We tested this hypothesis by first examining the gene expression response of male and female APCs to the PPARγ agonist, rosiglitazone. 8 weeks-old male and female were maintained on a HFD for five weeks before switching animals to a HFD containing rosiglitazone (100 mg/kg) for another four weeks (Figure S3A). Rosiglitazone treatment during this period did not significantly impact overall body weight (Figure S3B). We observed a slight but statistically significant increase in iWAT mass only in male animals treated with rosiglitazone (Figure S3B). Gene expression analysis revealed clear sex-differences in the mRNA levels of well-characterized pro-adipogenic genes, most notably in the committed DPP4− APC subpopulation. Rosiglitazone treatment led to a stronger induction in the expression of classic PPARγ target genes, including Pparg2, Cd36, Lpl, Fabp4, and Cebpa, in female DPP4− APCs than observed in male DPP4− APCs (Figure S3C). We also examined sex-differences in the degree of de novo adipogenesis that occurs upon HFD feeding. We performed genetic lineage tracing analysis of PDGFRβ+ cells using the previously described “MuralChaser” model (Figure 4C). This model allows for Dox-inducible and indelible labeling of Pdgfrb-expressing cells with membrane-bound GFP (mGFP) expression (Vishvanath et al., 2016). 8-week-old male and female MuralChaser mice were administered Dox-HFD for one week in order to mark PDGFRβ+ cells with mGFP expression. Animals were then switched to standard HFD for 9 additional weeks (Figure 4C). In line with previous studies, very few mGFP+ adipocytes emerge from PDGFRβ+ cells in iWAT of male mice (Shao et al., 2018; Vishvanath et al., 2016) (Figure 4D,E). On the contrary, mGFP+ adipocytes are readily apparent in female iWAT following 10 weeks of HFD feeding (Figure 4D,E). Rosiglitazone treatment during the last four weeks of the HFD feeding period further drove adipogenesis within the iWAT depots of female mice. Remarkably, following Rosiglitazone treatment ~30% of female iWAT adipocyte represent newly formed adipocytes. The corresponding frequency within iWAT of male mice remained much lower (< 2% of adipocytes). These data provide evidence that PPARγ is indeed more active in female subcutaneous WAT progenitors than in corresponding male progenitors in the setting of diet-induced obesity.

PPARγ S122 phosphorylation is mediated by extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). We examined how pharmacological blockade of ERK activation, and thus inhibition of PPARγ S122 phosphorylation, would impact the capacity for de novo adipogenesis in iWAT of male and female mice maintained on HFD. Treatment of animals with the MEK inhibitor, Trametinib (GSK1120212), during the last four weeks of a 10 weeks HFD period reduced levels of PPARγ S122 phosphorylation in PDGFRβ+ cells of both male and female iWAT without impacting body weight and iWAT mass (Figure S3D–F). Parallel lineage tracing experiments revealed that treatment with Trametinib allowed de novo adipogenesis to occur in the iWAT depot of male mice, at greater extent than Rosiglitazone treatment. Remarkably, the frequency of newly formed mGFP+ adipocytes in iWAT of male mice was now comparable to what is observed in iWAT depots of female mice maintained on HFD (Figure 4F,G). In female mice, Trametinib also induced a significant degree of de novo adipogenesis in the iWAT depot. Following Trametinib treatment, nearly 40% of female iWAT adipocytes present represent newly formed adipocytes. Taken all together, these data provide evidence that differential PPARγ phosphorylation underlies sex differences in iWAT APC differentiation.

Functional annotation identifies regulatory pathways controlling gWAT APCs and FIPs

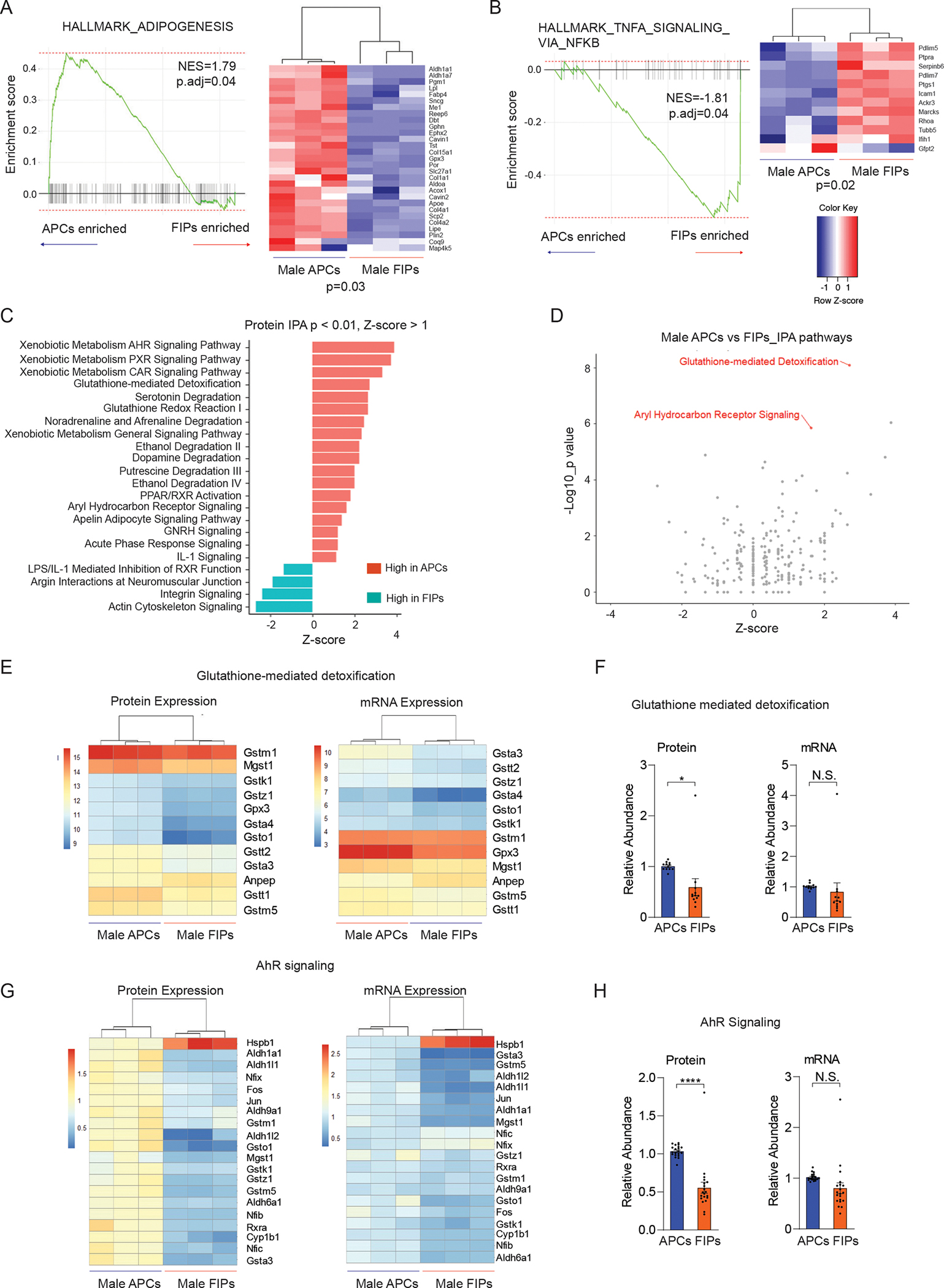

Our prior studies indicated that gWAT APCs and FIPs represent functionally distinct PDGFRβ+ subpopulations. Initial transcriptomic analyses and follow-up functional studies in vitro and in vivo established that APCs represent highly committed preadipocytes of gWAT while FIPs exhibit pro-inflammatory potential and modulate immune cell homeostasis associated with diet-induced obesity (DIO) (Hepler et al., 2018; Shan et al., 2020). Results from gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) based on proteomic data were consistent with the initial findings from transcriptomic data. In comparison to male FIPs, male APCs were enriched in pathways related to adipogenesis (p. adj = 0.04, normalized enrichment score (NES) = 1.79) (Figure 5A, Table S4). In addition, APCs were also enriched in signatures of fatty acid metabolism and bile acid metabolism. As predicted, “TNFα signaling via NFκB” was significantly enriched in male FIPs (p. adj = 0.04, NES= -1.81; Figure 5B, Table S4). One technical limitation to the analysis is the need for tissue mincing and enzymatic digestion prior to the isolation of distinct cell subpopulations by FACS. Lodish and colleagues previously reported that the commonly used collagenase-based tissue digestion protocol induces pro-inflammatory gene expression in adipose tissue cells (Ruan et al., 2003). We also evaluated the adipogenic and pro-inflammatory gene expression profile of APCs and FIPs isolated under conditions in which the transcriptional inhibitor, actinomycin D, is present throughout the tissue isolation, digestion, and cell separation process. The presence of actinomycin D did not impact the expression of any of the transcripts evaluated, indicating that the pro-inflammatory expression profile of FIPs is not secondary to the cell isolation process (Figure S4A,B). All together, these data are consistent with the assertion that APCs are highly adipogenic, whereas FIPs have intrinsic pro-inflammatory characteristics.

Figure 5. Gene signatures distinguishing gWAT APCs and FIPs.

(A) Gene set enriched analysis (GSEA) based on proteomic data reveals that male APCs are enriched in an “adipogenesis” gene signature in comparison to FIPs. Heat map depicting the expression of leading-edge subset of genes.

(B) Gene set enriched analysis (GSEA) based on proteomic data reveals that male FIPs are enriched in a “TNFα signaling via NFκB” gene signature in comparison to APCs. Heat map depicting the expression of leading-edge subset of genes.

(C) Most significantly enriched pathways discriminating male APCs and FIPs identified by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). Canonical pathways with significant coverage (p < 0.01) and a |z-score| >= 1.00 are shown.

(D) Glutathione-mediated detoxification and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) signaling were two of the most significantly upregulated pathways in male APCs when compared to FIPs.

(E) Heat map of protein levels (left) and transcript levels (right) of genes involved in glutathione-mediated detoxification in male APCs and FIPs.

(F) Expression of genes involved in glutathione-mediated detoxification were significantly enhanced in male APCs on the protein level, but not transcript level. * p < 0.05 by paired t-test. Each data point represents one gene corresponding to panel E, and y-axis shows their relative abundances.

(G) Heat map of protein levels (left) and transcript levels (right) of genes involved in AhR signaling in male APCs and FIPs. Differences in expression are more apparent on the protein level than on transcript level.

(H) Expression of genes involved in AhR signaling was significantly upregulated in male APCs on the protein level, but not transcript level. **** p < 0.00001 by paired t-test. Each data point represents one gene corresponding to panel G, and y-axis shows their relative abundances.

We also utilized additional predictive pathway analysis tools to identify potential regulatory mechanisms governing the properties of gWAT APCs and FIPs. Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) identified 46 enriched pathways (p < 0.01) comparing male APCs and FIPs. Among the 46 pathways, 18 pathways were enhanced in male APCs (z-score > 1.00), while 4 pathways including actin cytoskeleton signaling (p = 1.63E-4, z-score = −2.68) and integrin signaling (p = 3.25E-3, z-score = −2.36) were elevated in male FIPs (z-score < −1.00) (Figure 5C). Notably, glutathione-mediated detoxification (p = 8.32E-09, z-score = 2.71) and aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling (AhR signaling, p = 1.42E-06, z-score = 1.63) were among the most up-regulated pathways in male APCs at the protein level (Figure 5C,D). At the transcript level, however, AhR signaling was not significantly enriched in the APCs based on the RNA-seq data (p > 0.05, z-score = 0.91). Consistent with IPA, GO analysis also implicated glutathione metabolism as one of the most enriched pathways in male APCs (Benjamini adjusted p value = 3.63E-05). We looked more closely at the 12 genes involved in glutathione-mediated detoxification that were quantified at both protein and mRNA levels. Protein and mRNA levels of many of these genes were indeed distinguishable between APCs and FIPs (Figure 5E). Interestingly, despite the significant correlation between protein and mRNA levels of these genes, GSTM1 was the most abundant at the protein level, while Gpx3 had the highest abundance at the transcript level (Figure 5E and S6A). In aggregate, the expression of these genes was only statistically different between these two groups at the protein level (p < 0.05), but not at the mRNA level (Figure 5F). Similarly, the expression of genes involved in AhR signaling could distinguish APCs and FIPs at both the protein and mRNA levels; however, the enrichment of AhR signaling components in APCs was much more evident at the protein level than the transcript level (Figure 5G,H). We ruled out the possibility that the isolation process altered the transcript levels of these AhR signaling components by performing quantitative PCR analysis of APCs and FIPs isolated in the presence of actinomycin D (Figure S4C). As such, these data highlight the ability of the proteomic analysis to capture differences in regulatory pathways that are not readily reflected at the transcript level.

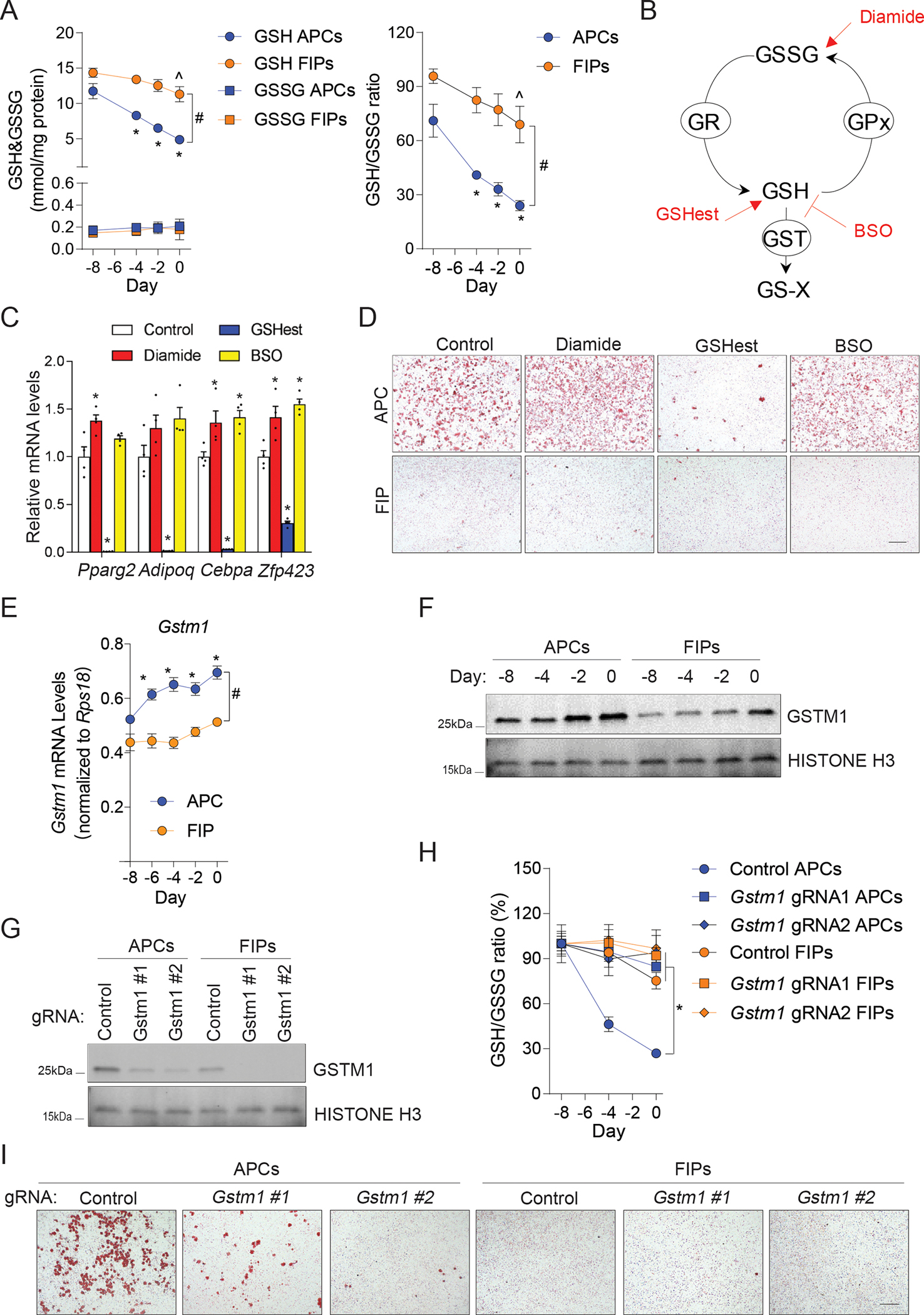

GSTM1 is required for cellular redox balance in APCs

It is notable that enzymes critically involved in glutathione (GSH) metabolism were highly enriched in male APCs compared to male FIPs. GSH metabolism controls intracellular redox status and is essential for numerous cellular processes, including cell differentiation (Ardite et al., 2004; Vigilanza et al., 2011). We measured the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in APCs and FIPs in culture during the 8-day time-period leading up to confluence (Day 0). Levels of cellular ROS were higher in APCs and FIPs at all time points examined and increased at a greater rate in APCs than observed in FIPs (Figure S5A). Consistent with prior studies (de Villiers et al., 2018), the ROS accumulation appears essential for normal adipocyte differentiation. The addition of N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) blocks differentiation of APCs in vitro in a dose dependent manner (Figure S5B,C). Glutathione exists in reduced (GSH) and oxidized (GSSG) forms, with the ratio of GSH to GSSG (GSH:GSSG) indicative of cellular redox status and oxidative stress. Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) enzymes are amongst the most enriched proteins in gWAT APCs (Figure S1E, Figure 5E). GSTs are involved in redox reactions of the GSH pathway, and thus regulate cellular GSH:GSSG ratios. We measured the GSH and GSSG levels in cell lysates of cultured primary APCs and FIPs. In APCs, the GSH levels, but not GSSG levels, rapidly decline as cells approach confluence and undergo spontaneous differentiation (Figure 6A). As a result, the GSH:GSSG ratios reduced by ~70% during APC differentiation (Figure 6A). Under identical conditions, similar trends of changes of intracellular GSH and GSSH occurred in FIPs, but to a much-lesser degree, suggesting a subpopulation-selective mechanism that permits APCs to maintain lower GSH:GSSG ratios (Figure 6A). To validate the importance of maintaining low GSH:GSSG ratios for adipogenesis, isolated APCs and FIPs were treated with chemicals to alter the GSH:GSSG ratios: diamide to induce rapid conversion of GSH to GSSG; L-buthionine-sulfoximine (BSO) to block GSH biosynthesis; or GSH ethyl ester (GSHest), a cell-permeable derivative of GSH which can be quickly hydrolyzed by intracellular esterases to release GSH (Figure 6B). APCs treated with diamide and BSO showed slight but statistically significant elevated adipogenic capacity (Figure 6C). On the other hand, GSHest treatment robustly inhibited the spontaneous differentiation of APCs (Figure 6D). Notably, none of the treatments could effectively induce FIPs to differentiate (Figure 6D). Thus, lowering GSH:GSSG ratios is not sufficient to drive non-adipogenic FIPs to undergo adipogenesis, while GSH catabolism appears essential for APCs to undergo differentiation.

Figure 6. Glutathione metabolism regulates adipogenesis through controlling cellular redox balance.

(A) Levels of glutathione (GSH) and glutathione disulfide (GSSG) (left), and GSH:GSSG ratios (right), in cell lysates from primary FIPs and APCs maintained in ITS growth media for 8 days up until the time of confluence (Day 0). N = 6. Data are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. * denotes p < 0.05 compared to APCs at Day -8, ^ denotes p < 0.05 compared to FIPs at Day -8, # denotes p < 0.05 between APCs and FIPs by two-way ANOVA.

(B) Schematic diagram of the effects of diamide, L-buthionine-sulfoximine (BSO), and GSH ethyl ester (GSHest), on the glutathione redox pathway. GST, glutatione s-transferase; GR, glutathione reductase; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; GS-X, GSH conjugates or GSH conjugated metabolites.

(C) mRNA levels of adipocyte-selective genes (Pparg2, Adipoq, Cebpa and Zfp423) in differentiated primary APCs exposed to the indicated treatments during differentiation. Differentiation was allowed to occur spontaneously while cells were maintained in ITS growth media. N = 4. Bars represent mean ± s.e.m. * denotes p < 0.05 compared to control group by one-way ANOVA.

(D) Representative bright-field images of Oil-red O-stained cultures described in (C). Scale bar = 200 μm.

(E) mRNA levels of Gstm1 in primary FIPs and APCs maintained in ITS growth media for 8 days up until the time of confluence (Day 0). N = 3. Data points represent mean ± s.e.m. * denotes p < 0.05 compared to APC day -8, # denotes p < 0.05 between APC and FIP by two-way ANOVA.

(F) Western blot analysis of GSTM1 levels in primary FIPs and APCs maintained in ITS growth media for 8 days up until the time of confluence (Day 0).

(G) Western blot analysis of GSTM1 in primary FIPs and APCs transduced with the indicated CRISPR lentivirus.

(H) GSH:GSSG ratios in cell lysates of primary FIPs and APCs transduced with the indicated CRISPR lentivirus and maintained in ITS growth media for 8 days up until the time of confluence (Day 0). N = 4. Data points represent mean ± s.e.m. * denotes p < 0.05 compared to Control APCs by two-way ANOVA.

(I) Representative bright-field images of Oil-red O-stained cultures of differentiated primary FIPs and APCs transduced with the indicated CRISPR lentivirus. Differentiation was allowed to occur spontaneously while cells were maintained in ITS growth media. Scale bar = 200 μm.

GSTs catalyze the conjugation of GSH to xenobiotic substrates for the purpose of cellular detoxification, a process which efficiently consumes GSH (Figure 6B). This prompted us to ask whether GSTs maintain low GSH levels in APCs during differentiation. Among all detected GSTs in WAT PDGFRβ+ cells, GSTM1 appeared to be the most abundant at the protein level (Figure 5E). In fact, both Gstm1 RNA and protein steadily increased during APC spontaneous differentiation (Figure 6E,F). Protein and mRNA levels of Gstm1 in FIPs remained significantly lower than observed in APCs under identical cell culture conditions (Figure 6E,F). We utilized CRISPR-cas9 gene editing, with two individual gRNAs, to inactivate Gstm1 in isolated APCs and FIPs (Figure 6G). The differentiation-linked decrease in the GSH:GSSG ratio was almost completely blocked in APCs expressing either of the two gRNAs. (Figure 6H). Thus, Gstm1 is essential in the control of intracellular redox status in this setting. Gstm1-deficiency also reduces the adipogenic potential of APCs (Figure 6I). Notably, the most highly expressed gene at the RNA level, Gpx3, is functionally dispensable for the maintenance of cellular redox status and differentiation of APCs (Figure S6A–D). As such, these data support the growing appreciation of cellular metabolism as critical regulator of adipose progenitor function and uncover GSTM1 as a primary enzyme of intracellular glutathione metabolism in gWAT APCs.

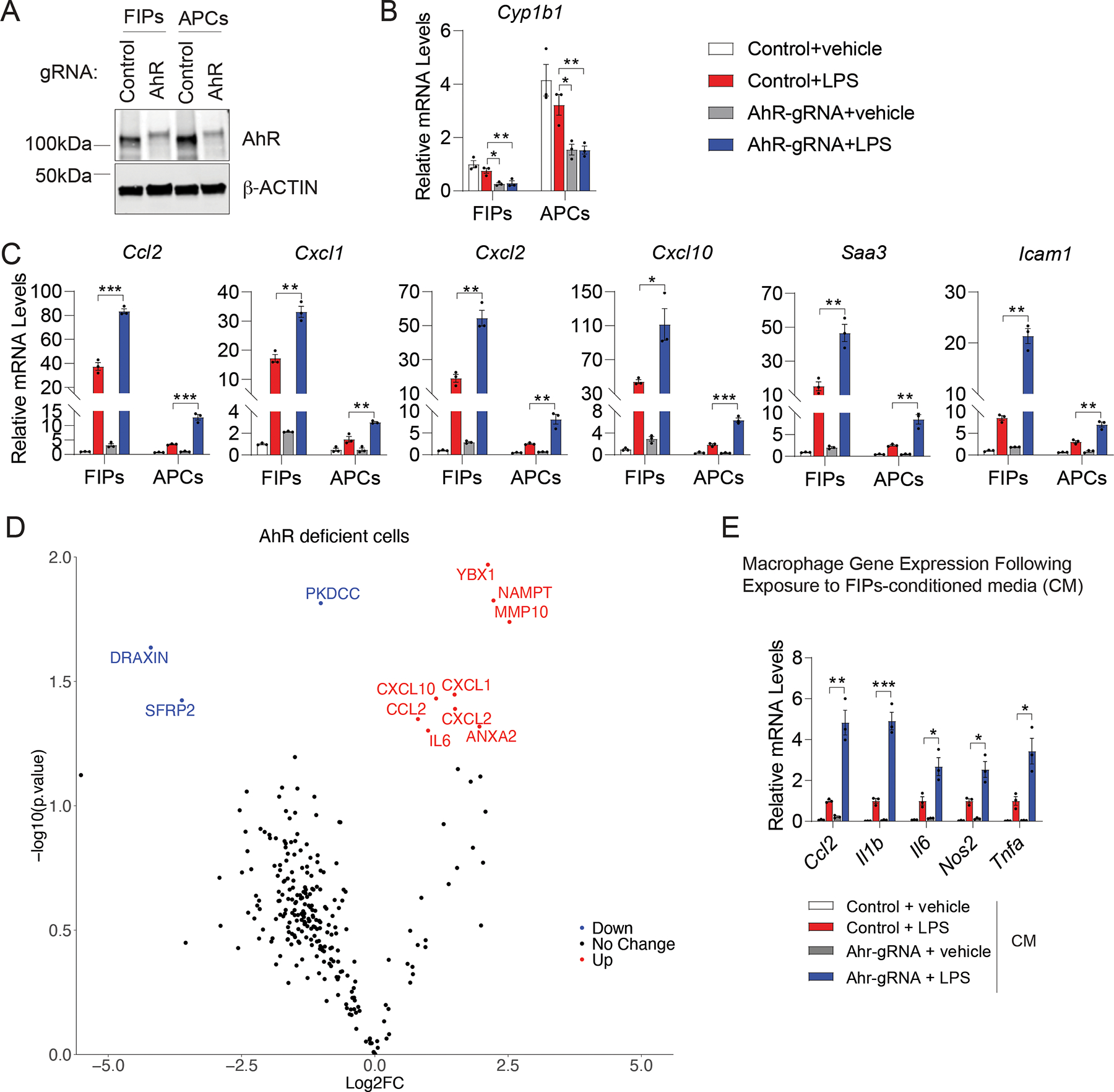

AhR signaling suppresses the inflammatory responses of FIPs and APCs

AhR is a receptor and transcription factor which is involved in regulating inflammatory responses of various cell types, most notably in macrophages (Shinde et al., 2018; Shinde and McGaha, 2018). The enrichment of AhR signaling components in APCs relative to their expression in FIPs was thus notable, given the differences in inflammatory potential of these two cell subpopulations (Figure 5G,H). We observed that CRISPR-Cas9-mediated inactivation of AhR led to a substantial reduction in AhR protein expression in cultures of APCs and FIPs (Figure 7A). This coincided with a reduction in Cyp1b1 levels, a direct transcriptional target of AhR (Figure 7B). Notably, inactivation of AhR robustly sensitizes FIPs and APCs to the pro-inflammatory transcriptional response to LPS stimulation (Figure 7C). Following LPS treatment in vitro, AhR-deficient FIPs and APCs express higher mRNA levels of well-described pro-inflammatory genes, including cytokine/chemokines (Ccl2, Cxcl1, Cxcl2, Cxcl10, Saa3) and the adhesion molecule, Icam1. These data were corroborated by proteomic analysis of the conditioned media from cultured FIPs using LC-MS. Protein levels of CCL2, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL10, and IL-6 were all significantly elevated in the conditioned media of AhR-deficient FIPs in comparison to media collected from Control FIPs (Figure 7D). We then asked whether the enhanced expression of these pro-inflammatory molecules reflects a heightened functional pro-inflammatory phenotype. We exposed primary cultures of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) to conditioned media collected from cultured control and AhR-deficient FIPs following LPS treatment. We observed that the expression levels of Ccl2, Il1b, Il6, Nos2, and Tnfα (indicators of activated macrophages), were further elevated in the macrophages exposed to the conditioned media from AhR-deficient FIPs compared to BMDMs exposed to conditioned media from control FIPs (Figure 7E). This provides evidence that AhR-deficient FIPs exhibit a heightened pro-inflammatory phenotype. These observations were further supported by experiments utilizing an AhR agonist (indoxyl 3-sulfate, I3S) or antagonist (CH223191) to modulate the activity of AhR signaling in these two populations. The addition of AhR agonist to LPS-treated cells amplified the activation of Cyp1b1 expression and suppressed the expression levels of pro-inflammatory genes which were induced by LPS treatment in both subpopulations (Figure S7A,B). Moreover, suppression of AhR activity by CH223191 resulted in markedly elevated pro-inflammatory gene expression in both cell populations (Figure S7A,B). In addition, pharmacological modulation of AhR using the agonist or antagonist impacted the ability of FIPs to modulate co-cultured BMDMs (Figure S7C). Together, our data demonstrate that AhR serves a key role in controlling inflammatory responses of PDGFRβ+ perivascular cells within gonadal adipose tissue, which was not clearly unveiled by transcriptomic data alone.

Figure 7. AhR activity impacts the inflammatory responses of FIPs and APCs.

(A) Western blot of AhR and β-ACTIN in cell lysates of primary FIPs and APCs transduced with CRISPR lentivirus expressing indicated gRNAs.

(B) mRNA levels of Cyp1b1 in targeted FIPs and APCs 2 hours after treatment with vehicle or 100ng/ml LPS. N = 4 each group. Each represents cells pooled from depots of 6 individual mice. Bars represent mean ± s.e.m., * denotes p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA.

(C) mRNA levels of indicated pro-inflammatory genes in cultures of FIPs and APCs described in B). N = 4 each group. Bars represent mean ± s.e.m., * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA.

(D) Volcano plot depicting differential protein levels within the conditioned media of AhR-deficient vs. Control FIPs. P value <0.05 and Log2(Fold change) >0.5 or <-0.5 were defined as UP or DOWN.

(E) mRNA levels of genes associated with macrophage activation in cultured BMDMs following exposure to the indicated FIPs conditioned medium for 90 min. N = 3 each group. Bars represent mean ± s.e.m., * denotes p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.01, *** denotes p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA.

FIPs (isolated from pooled depots of 8 mice) were treated with vehicle or LPS (100 ng/ml) for 2 hours following indicated CRISPR lentivirus transduction. The cells were then incubated in serum-free medium for an additional 24 hour to produce conditioned medium (D, E).

DISCUSSION

Single-cell and single-nuclei RNA sequencing studies have firmly established the existence of heterogeneity amongst adipose progenitor cells residing in adult adipose tissues (Burl et al., 2018; Hepler et al., 2018; Merrick et al., 2019; Sarvari et al., 2021; Schwalie et al., 2018; Shao et al., 2021; Spallanzani et al., 2019). Importantly, engineered mouse models have begun to highlight the importance of such functionally diverse progenitor populations in establishing and maintaining adipose tissue health and plasticity in adulthood (Gao et al., 2020; Joffin et al., 2021; Shan et al., 2021; Shan et al., 2020; Shao et al., 2021; Shao et al., 2018). In this study, we performed a multilayered proteomic and transcriptomic analysis of adipose tissue progenitor cell heterogeneity. These data, accessible through the PreadProfiler (http://preadprofiler.net), provide deeper insight into molecular heterogeneity of these cell subpopulations and allow investigators to explore protein/gene expression in the dimensions of sex and depot of origin. Moreover, the comprehensive peptide spectral library we have generated here can be readily applied to other quantitative proteomics studies of adipose stromal cell populations.

The analyzed stromal cell populations exhibit quite distinct steady state molecular signatures at both protein and transcript levels; however, it is notable that the manner in which the populations can be grouped depends on the layer of analysis. Clustering based on proteomic data highlight the functional similarities and differences between the subgroups of cells, whereas clustering on the basis of transcriptomic data is driven by expression signatures reflecting their anatomical origins (i.e., visceral vs. subcutaneous depots). As such, proteomic data may serve as a more effective predictor of functional similarity of cell subpopulations.

Transcript levels are not indicative of cognate protein levels in many scenarios (Casas-Vila et al., 2017; Grun et al., 2014; Gygi et al., 1999; Williams et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2014). Indeed, in general expression of protein had significant yet nominal correlation with their transcript counterparts in isolated stromal cells. This correlation was strongly influenced by variation in protein and transcript abundances across samples: proteins with higher variation across samples were more likely to significantly correlate with their corresponding transcripts, and vice versa. Thus, changes in a certain transcript may not necessarily be reflected at the protein level. Surprisingly, both sex and depot had an impact on protein-transcript correlation. Notably, the correlation was also highly dependent on the individual pathway or gene set examined. We observed a strong correlation between the proteome and transcriptome layers for canonical pathways including glutathione metabolism, fatty acid metabolism and glycolysis, suggesting that these pathways were mostly transcriptionally regulated. For other gene sets, expression at protein and transcript levels did not significantly correlate, or even inversely correlated. At present, we cannot offer a mechanism for the discordance between RNA and protein levels; however, numerous possibilities exist including differences in half-life between mRNAs and proteins and mechanisms involving post-translational modifications. Further investigation will be needed to understand the underlying mechanisms for this variation in more detail. Nevertheless, these findings highlight the benefits of concurrent measurements of both the proteome and the transcriptome, and that each layer can unveil different regulatory mechanisms.

DIA-MS facilitated the identification of potential regulatory pathways governing the unique functional properties of adipose progenitor subpopulations. Notably, all of the progenitor subpopulations can be distinguished based on the expression of the 556 proteins implicated in cellular metabolism, in line with the recent study from Joffin et al. indicating a fundamental role for energy metabolism in the control of adipose progenitor cell heterogeneity (Joffin et al., 2021). Furthermore, the expression of 145 mitochondrial proteins is sex-dependent, with enrichment in female progenitor cell populations. This warrants further investigation into sex-differences in the cellular metabolism of adipose progenitors. Importantly, the enrichment of proteins related to hypoxia response and HIF1α signaling in male vs. female committed iWAT APCs led us to the finding that differences in the levels of PPARγ S112 phosphorylation may underlie the sex differences in the adipogenic potential of these cells following HFD feeding. Moreover, proteomic analysis also revealed functionally important pathways, some of which were not visible based on the RNA-seq data, despite a larger coverage. We observed that glutathione metabolism and AhR signaling contribute to the adipogenic and pro-inflammatory properties of adipose progenitors, respectively. In particular, we found that GSTM1, the most abundant of GST proteins detected, is essential for cellular redox balance in APCs and for maintaining adipogenic potential. Additional studies will be required to better define how redox balance impacts the expression and/or activity of critical proteins that mediate adipogenesis. Collectively, these findings represent proof-of-concept that multilayered omics datasets provide additional insights into regulatory pathways controlling the functional properties of distinct adipose progenitor subpopulations, along with mechanisms driving sex- and depot-dependent differences in their behavior. More broadly, the approach described here may be leveraged to gain insight into the functional heterogeneity of other complicated cell subpopulations in other tissues and settings. The data here highlight the benefits of utilizing complementary proteomics to support findings from scRNA-seq studies and define the functional properties of proposed cell subpopulations.

Limitations of study

As noted above, an important caveat to our expression analyses is the need for extensive tissue processing for the isolation of distinct cell subpopulations by FACS. Our gene expression analysis of FIPs and APCs isolated in the presence of actinomycin D confirm that the distinct pro-inflammatory and adipogenic expression profiles of these cell subpopulations are not a product of the overall isolation protocol. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that the isolation procedure impacts the transcriptomic and/or proteomic profiles of the cell subpopulations examined here. Going forward, the development of genetic approaches to selectively target specific stromal cell subpopulations may enable affinity purification of translating ribosomes and cell-type specific RNAs from intact tissues.

Our analysis of progenitor cell heterogeneity described here focuses on four progenitor subpopulations identified in murine adipose depots. The cell populations described for iWAT and gWAT were independently found in other studies as being the predominant progenitor subpopulations present in these depots; however, we certainly cannot exclude the possibility that other functionally distinct subpopulations exist that do not express PDGFRβ and/or were not captured in our approach. In particular, the recently characterized anti-adipogenic Aregs of iWAT were not included in this study, as they were not identified amongst the PDGFRβ+ cells initially characterized (Schwalie et al., 2018). Furthermore, additional heterogeneity may exist amongst the individual subpopulations described here. For instance, Merrick et al. described two distinct subpopulations of DPP4− APCs in iWAT depot (Merrick et al., 2019). Thus, the pool of DPP4− APCs from iWAT studied here may in fact be further heterogeneous. In addition, our analyses were restricted to the progenitor subpopulations of iWAT and gWAT in the steady state. It is likely that additional WAT or brown adipose tissue depots harbor progenitors with depot-selective properties. Further analysis of anatomically distinct adipose depots, and under different physiological and pathophysiological conditions, is needed to shed further insight into the molecular heterogeneity of adipose tissue progenitors.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Yibo Wu (yibo.wu@riken.jp).

Material Availability

Unique materials and reagents generated in this study are available upon request from the Lead Contact with a completed Material Transfer Agreement.

Data and Code Availability

The RNA sequencing datasets are available at GEO Accession viewer (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under the accession number GSE165600; the mass spectrometry datasets are available at ProteomeXchange (https://www.proteomexchange.org) under the accession number PXD023829.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Animals

All animals used in this study were on a pure C57BL/6J background. Rosa26RmT/mG (B6 129(Cg)-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo/J; JAX 007676) and TRE-Cre (B6.Cg-Tg(tetO-cre)1Jaw/J; JAX 006234) strains were obtained from Jackson laboratory. PdgfrbrtTA transgenic mice (C57BL/6-Tg(Pdgfrb-rtTA)58Gpta/J; JAX 028570) and TRE-Pparg2 have been described previously (Shao et al., 2018; Vishvanath et al., 2016). Mice were maintained with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and free access to food and water. All animal experiments were performed according to procedures approved by the UTSW Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Rodent diets and drug treatments

Mice were maintained on a standard rodent chow diet prior to high-fat-diet feeding as described. For high-fat diet studies, mice were fed a standard high-fat diet (60 kcal% fat, Research Diets, D12492i), a standard high-fat diet (60 kcal% fat, Research Diets, D12492i) supplemented with Rosiglitazone (100 mg/kg), or doxycycline-containing high-fat diet (600 mg/kg dox, 60 kcal% fat, Bio-Serv, S5867) as indicated.

Mice were administered Trametinib (3 mg/kg body weight; Selleckchem, #S2673) or vehicle control by oral gavage every two days as indicated.

Isolation of Adipose SVF cells and FACS

The SVFs of gonadal and inguinal white adipose tissue were prepared as previously described (Peics et al., 2020; Shao et al., 2018). In brief, depots of gonadal and inguinal WAT were minced thoroughly before being incubated for 40 min. (gonadal) or 80 min. (inguinal) in 10 ml digestion buffer (1X HBSS, 1.5% BSA and 1 mg/ml collagenase D (Roche, no. 11088882001) at 37°C in a shaking water bath. 1 μg/ml Actinomycin D was added to the digestion buffer in indicated experiments. The digested mixture was placed on the ice immediately after digestion and then filtered through a 100 μm cell strainer into 20 ml pre-chilled 2% FBS/PBS. After centrifugation (600 × g for 5 min. at 4 °C), the stromal pellet was resuspended and briefly (1–2 minutes) incubated in 1 ml RBC lysis buffer (eBioscience, no. 00-4300-54) to remove red blood cells. Red blood cell lysis was stopped by the addition of 5 ml of pre-chilled 2% FBS/PBS. Cells were then filtered again through a 40 μm cell strainer before centrifugation at 600 × g for 5 min. at 4 °C. After centrifugation, cells were resuspended in blocking buffer (2% FBS/PBS containing anti-mouse CD16/CD32 Fc Block, 1:200 dilution) for 10 min incubation on ice.

For cell sorting of FIPs, APCs, DPP4+ APCs, and DPP4− APCs, primary antibodies were added to the cells in blocking buffer and incubated at 4°C for 15 min. After washing, the cells were resuspended in 2% FBS/PBS for sorting. FACS was conducted using a BD Bioscience FACSAria cytometer at the Flow Cytometry Core Facility at UT Southwestern. The primary antibodies and the dilution were as follows: CD45-PerCP/Cyanine5.5, 1:400 (Biolegend, clone 30-F11, no. 103132); CD31-PerCP/Cyanine 5.5, 1:400 (Biolegend, clone 390, no. 102420); PDGFRβ-PE, 1:75 (Biolegend, clone APB5, no. 136006); LY6C-APC, 1:400 (Biolegend, clone HK1.4, no. 128016); CD9-FITC, 1:400 (Biolegend, clone MZ3, no. 124808); DPP4-APC, 1:200 (Biolegend, clone H194–112, no. 137807).

Protein Extraction and Mass Spectrometry Sample Preparation

Sorted cell pellets (1 × 105 cells) were prepared for mass spectrometry following the phase transfer surfactant method (Masuda et al., 2009; Masuda et al., 2008), with modifications described as follows: The cell pellets were suspended in 15 μL 12 mM sodium deoxycholate, 12 mM sodium N-dodecanoylsarcosinate (sodium N-Lauroyl sarcosinate), 100 mM Tris.Cl pH 9.0, with cOmplete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Switzerland) and sonicated for 5 min using a Bioruptor (Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd., Japan) on high power with 1-min on/1-min off cycles. Protein concentration of each sample was determined using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). Reduction of cysteine-cysteine disulfide bonds was done by the addition of DL-dithiothreitol to 10 mM and incubation at 50°C for 30 min with shaking in a Thermomixer (Eppendorf, Germany), followed by alkylation of free thiol groups by the addition of iodoacetamide (MilliporeSigma, USA) to 40 mM in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. Alkylation was quenched with addition of cysteine to 55 mM at room temperature for 10 min. The samples were diluted with 2.76 volumes of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Mass spectrometry grade lysyl endopeptidase (Lysine-C; FUJIFILM Wako Chemical Corporation, Japan) was added at 200 ng and, after mixing, sequencing grade modified trypsin (Promega, USA) was added at 200 ng, followed by digestion for 14 hours at 37°C. Afterwards, 1.83 volumes ethyl acetate was added, and the samples were acidified with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), which was added to 0.5% (v/v). Following centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature, the samples separated into two phases, the upper organic phase containing sodium deoxycholate was removed, while the lower aqueous phase containing digested tryptic peptides was dried using a centrifugal vacuum concentrator. After digestion, samples were desalted with ZipTip C18, 0.6 μL Pipette Tips (MilliporeSigma, USA) and dried using a vacuum centrifuge. For generation of the spectral library, a mixture of the tryptic peptide samples was fractionated using a Pierce High pH Reversed-Phase (HPRP) Fractionation Kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). Eight fractions were collected in solution with increasing acetonitrile concentration from 5% (v/v) to 50% (v/v) in 0.1% (v/v) triethylamine in water. Afterwards, the fractions were dried by vacuum centrifugation.

Mass Spectrometry Measurement

LC-MS/MS measurements were made using a Q-Exactive Plus Orbitrap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) equipped with a Nanospray Flex ion source coupled to an EASY-nLC 1200 system (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). For LC, the peptides were concentrated using an Acclaim PepMap 100 trap column with 3 μm C18 particles, an inner diameter of 75 μm, and a filling length of 2 cm (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) and then separated using an analytical column with 3 μm C18 particles, an inner diameter of 75 μm and a length of 12.5 cm (Nikkyo Technos Co., Ltd., Japan). LC solvent A consisted of 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water and LC solvent B consisted of 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in 80% (v/v) acetonitrile. The solvents were LC/MS grade. A flow rate of 300 nL/min was used with a two-hour gradient: 2% B to 34% B in 108 min, 34% B to 95% B in 2 min, with a final wash at 95% B for 10 min. The mass spectrometer ion transfer tube temperature was 250°C and 2.0 kV spray voltage was applied during sample measurement.

For data-independent acquisition (DIA), dried tryptic peptide samples were dissolved in about 10 μL of 0.1% (v/v) formic acid, 3% (v/v) acetonitrile in water, the exact volume depended upon the original protein amount, and 3 μL was loaded onto a trap column, corresponding to sample prepared from an average of 2.7 × 104 cells. Data were acquired with 1 full MS and 32 overlapping isolation windows constructed covering the precursor mass range of 400–1200 m/z. For full MS, resolution was set to 70,000, AGC target was set to 5e6, and the maximum injection time (IT) was set to 120 ms. DIA segments were acquired at 35,000 resolution with an AGC target of 3e6 and an automatic maximum IT. The first mass was fixed at 150 m/z. HCD fragmentation was set to normalized collision energy of 27%.

For data-dependent acquisition (DDA) of the HPRP fractionated samples, each fraction was dissolved in 6.5 μL of 0.1% (v/v) formic acid, 3% (v/v) acetonitrile in water and 5.0 μL was loaded onto the trap column. The full MS spectra were acquired from 380 to 1500 m/z at a resolution of 70,000, the AGC target was set to 3e6 and a maximum IT of 100 ms. The MS2 scans were recorded for the top 20 precursors at 17,500 resolution with an AGC target of 1e5 and a maximum IT of 60 ms. The default charge state for the MS2 was set to 2. HCD fragmentation was set to normalized collision energy of 27%. The intensity threshold was set to 1.3e4, charge states 2–5 were included, and the dynamic exclusion was set to 20 s.

Protein Identification and Quantification

For generation of the spectral library, the 8 raw data files obtained from DDA of the HPRP-fractionated tryptic peptide fractions derived from the FACS-sorted cell samples were analyzed together with 8 raw data files obtained from DDA of HPRP-fractionated tryptic peptide fractions derived from adipose tissue SVF samples prepared separately. The 16 files were analyzed together using Proteome Discoverer version 2.4 (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) against the Uniprot reviewed Mus musculus (taxon 10090) database to generate a single results file. Digestion enzyme specificity was set to Trypsin (Full). Precursor and fragment mass tolerances were set to 10 ppm and 0.02 Da, respectively. Modifications included carbamidomethylation of cysteine as a static modification, and oxidation of methionine, and protein N-terminal acetylation, methionine loss, and acetylation and methionine loss as dynamic modifications. Up to 2 missed cleavages were allowed. A concatenated decoy database was used to calculate the false discovery rate (FDR). Search results were filtered with FDR 0.01 at both peptide and protein levels. The filtered output from Proteome Discoverer was used to generate a sample-specific spectral library using Spectronaut software (Biognosys, Switzerland). Raw data files from DIA measurement were used for extraction of protein quantities with the generated spectral library. FDR was estimated with the mProphet approach and set to 0.01 at both peptide precursor level and protein level (Reiter et al., 2011; Rosenberger et al., 2017). Data filtering parameters for quantification were Q-value percentile fraction 0.5 with global imputing, and cross run normalization with global normalization on the median. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD023829.

RNA-seq Analysis

PDGFRβ+ cell RNA-seq analysis was performed as described (Shan et al., 2020). Briefly, reads with phred quality scores <20 and <35 bp after trimming were removed from further analysis using trimgalore version 0.4.1. Quality-filtered reads were aligned to the mouse reference genome GRCm38 (mm10) by HISAT2 version 2.0.1 using default settings. Aligned reads were quantified using featureCounts version 1.4.6 per gene ID against mouse Gencode version 20. Analysis of differential gene expression was done using DEseq2 version 1.6.3. Cut-off values of fold change and FDR used to select for differentially expressed genes were described in the text. All RNA-seq data have been deposited to GEO under the accession number GSE165600.

Bioinformatics Data Analysis

The global clustering and comparative analyses were performed on normalized protein and transcript abundances. For transcriptomic data, only the 15477 transcripts with corresponding protein sequences manually annotated in the Uniprot Knowledgebase were kept for further analysis. GO annotation was done using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (Huang da et al., 2009a, b). ANOVA for proteomic data and hierarchical clustering were performed on either Z-scores or log2-transformed values in R. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using ClustVis (https://biit.cs.ut.ee/clustvis/) (Metsalu and Vilo, 2015). To estimate protein-transcript correlation, only transcripts quantified in all samples were compared with the corresponding proteins. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated in R using the cor.test function. For a two-group comparison and/or volcano plot, a paired t-test was performed. Proteins and transcripts regulated by > = 1.5-fold and p value < 0.05 were considered significant. The same significance cutoff for a protein/transcript was applied in pathway analysis of both proteomic and transcriptomic data using the QIAGEN Ingenuity Pathway Analysis application (Qiagen IPA). Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using R package of fast gene set enrichment analysis (https://github.com/ctlab/fgsea). Gene set files for this analysis were obtained from GSEA website (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea). Bar plots showed data as mean ± SEM and depicted p values from paired t-test or ANOVA as noted in figure legends.

Cell Culture and Cellular Assays

Culture of PDGFRβ+ subpopulations

For FIPs and APCs, freshly isolated cells were cultured in previously defined “ITS media” [60% low glucose DMEM, 40% MCDB-201 media, 2% FBS, 1% ITS premix (Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium) (BD Bioscience, #354352), 0.1 mM L-ascorbic acid-2-2phosphate (Sigma, #A8960–5G), 10 ng/mL FGF basic (R&D systems, #3139-FB-025/CF), Pen/Strep, and gentamicin]. For modulation of AhR activity by chemical compounds, isolated cells from wild type C57BL/6J male mice were incubated with AhR agonist I3S (100 ug/ml; Sigma, no. I3857) or inhibitor CH223191 (10 uM; Simga, no. C8124) in ITS media for 12 hours before further experiments. For loss of function studies in vitro, isolated cells were transduced with diluted lentivirus (1:10 ratio) in ITS media containing 8 mg/ml polybrene (Sigma, #TR-1003) for 24 hr. Following transduction, cells were maintained in ITS media for > 48 hr before beginning treatments.

Preparation of FIP conditioned medium

FIPs were isolated from gonadal WAT of wild-type C57BL/6J male mice and then plated in 24-well plates (1×105 cells/well) prior to lentivirus transduction or chemical treatments as described above. The cells were subsequently treated with vehicle or LPS (100 ng/ml) for 2 hours. After three washes with PBS (to remove LPS), cells were replaced with fresh serum-free ITS media and incubated for 24 hours. Medium was then collected and briefly centrifuged (3000 × g for 15 min) to remove debris. For all experiments, the conditioned medium was mixed 1:1 with fresh serum-free ITS media before being placed on target cells.

Macrophage differentiation and assays

Bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) used in this study were derived from bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) isolated from the femurs and tibias of male mice as previously described (Shan et al., 2017). BMSCs were maintained in L929 cell-derived differentiation medium for 7 days to induce the differentiation of mature macrophages. Mature BMDMs were then maintained in 2% FBS-containing ITS media for at least 24 hours before being switched to serum-free ITS media for more than 6 hours for further experiments. For conditioned medium experiments, BMDMs were incubated in conditioned medium for 1.5 hours and then harvested for RNA analysis.

Lentiviral CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Targeting

Lentiviral CRIPSR plasmids targeting Gstm1, Ahr, Gpx3 were constructed by cloning gRNAs (Gstm1 #1: 5’-ATTCCAGGAGCATGCGGATC-3’; Gstm1 #2: 5’-CCTTGCCCGAAAGCACCACC-3’, Ahr: 5’-CTCCACTATCCAAGATTACC-3’; Gpx3 #1: 5’-ATGGAGCCCTCACCATCGAT-3’; Gpx3 #2: 5’-TGGTACCACTCATACCGCCA-3’) into the LentiCRISPR V2 (Addgene #52961) plasmid backbone. For lentivirus production, 10 μg lentiviral CRISPR plasmids were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent (ThermoFisher, #11668019) into Phoenix packaging cells along with 5 μg pMD2.G (Addgene #12259) and 5 μg psPAX2 (Addgene #12260). Viral supernatants were harvested 48 hours after transfection. For viral infection, viral supernatants were applied to primary PDGFRβ+ cells for 24 hours in the presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma, H9268). Next, infected cells were cultured in virus-free media for at least another 24 hours before being used for the indicated experiments.

Indirect Immunofluorescence

Paraffin sections for histological analysis were processed at the Molecular Pathology Core Facility at UTSW. For indirect immunofluorescence, the following primary and secondary antibodies and concentrations were used: guinea pig anti-PLIN1, 1:1000 (Fitzgerald, 20R-PP004); chicken anti-GFP, 1:500 (Abcam, ab13970); goat anti-chicken Alexa 488, 1:200 (ThermoFisher, A-11039); and goat anti-guinea pig Alexa 647, 1:200 (ThermoFisher, A-21450). Dewaxed and dehydrated slides were placed in chambers containing 1xR-buffer A pH 6.0 solution and antigen retrieval was performed using Antigen Retriever 2100 (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 2 hours. Following one PBS wash for 5 minutes, Fx Signal Enhancer (ThermoFisher, I36933) was applied to the slides for 30 minutes at room temperature. Slides were then blocked in 10% normal goat serum (NGS)/PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. Primary antibodies diluted in 10% NGS/PBS were added to the slides for overnight incubation at 4°C. Following the incubation, slides were washed in PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies diluted in 10% NGS/PBS for 2 hours at room temperature. After three PBS washes, slides were mounted with Prolong Gold Anti-Fade mounting medium containing DAPI (ThermoFisher, P36931) before confocal images were captured using a Zeiss LSM880 Airyscan system (Zeiss Germany) at the UTSW Live Cell Imaging Core.

Gene Expression Analysis by Quantitative PCR

Total RNA from tissue and cultured cells was extracted and purified using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, no. 15596026). cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers (ThermoFisher Scientific, no. N8080127) and M-MLV reverse transcriptase (ThermoFisher Scientific, no. 28025013). Relative levels of mRNAs were measured by quantitative real-time PCR using SYBR Green PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and Rps18 was used as an internal control for calculation using the DD-Ct method. All primer sequences used in this study are listed in the Table S5.

Immunoblotting and Antibodies