Abstract

Ammonium absorbed by roots is assimilated into amino acids. The glutamine synthetase/glutamate synthase (glutamine 2-oxoglutarate aminotransferase) (GS/GOGAT) cycle is essential to this biological process. In Arabidopsis thaliana, GLN1;2 and GLT1 are the GS and GOGAT isoenzymes induced in response to ammonium supply and playing key roles in ammonium utilization. Although recent studies suggest gene regulatory networks involved in transcriptional regulation of ammonium-responsive genes, direct regulatory mechanisms for ammonium-induced expression of GS/GOGAT remain unclear. In this study, we revealed that the expression of GLN1;2 and GLT1 in Arabidopsis is not directly induced by ammonium but is regulated by glutamine or post-glutamine metabolites produced by ammonium assimilation. Previously, we identified a promoter region required for ammonium-responsive expression of GLN1;2. In this study, we further dissected the ammonium-responsive region of the GLN1;2 promoter and also performed a deletion analysis of the GLT1 promoter, which led to the identification of a conserved ammonium-responsive region. Yeast one-hybrid screening using the ammonium-responsive region of the GLN1;2 promoter as a decoy sequence revealed a trihelix family transcription factor DF1 that binds to this region. A putative DF1 binding site was also found in the ammonium-responsive region of the GLT1 promoter.

Keywords: ammonium response, glutamate synthase (GOGAT), glutamine synthetase (GS), GS/GOGAT, promoter, root, transcriptional (regulation)

1. Introduction

Plants absorb nitrogen from the soil to grow (Marschner, 1995). The nitrogen that plants absorb from the soil is either ammonium or nitrate. Nitrate is reduced to ammonium. Ammonium is combined with glutamate and assimilated into glutamine (Marschner, 1995). Ammonium is assimilated primarily in the roots where the glutamine synthetase (GS or GLN) catalyzes this reaction. (Vega-Mas et al., 2019; Kojima et al., 2020). Subsequently, an amino group of glutamine transfers to 2-OG to synthesize glutamate. Glutamate synthase (glutamine 2-oxoglutarate aminotransferase; GOGAT) catalyzes this reaction. Thus, GS and GOGAT are the enzymes for these conjugate reactions. Ammonium assimilation through the GS/GOGAT cycle is the major pathway of nitrogen assimilation in plants (Lea and Miflin, 1974).

Genome sequencing has revealed various isoenzymes of GS/GOGAT in plants. Among them are the isoenzymes expressed in plant roots in response to ammonium supply, such as GS1;2 and NADH-GOGAT1 from rice (Tabuchi et al., 2007) and GLN1;2 and NADH-GOGAT (GLT1) from Arabidopsis (Ishiyama et al., 2004a; Kojima et al., 2014; Konishi et al., 2014). Their transcript and protein accumulation that occurs in response to ammonium manifests the importance of these isoenzymes in ammonium assimilation. Reverse genetic analysis has provided evidence that loss of these ammonium-responsive GS/GOGAT isoenzyme-encoding genes results in reduced ammonium assimilation in plants, particularly in the roots, preventing normal growth (Tamura et al., 2010; Funayama et al., 2013; Konishi et al., 2014; Konishi et al., 2017; Konishi et al., 2018). These results have suggested that ammonium-responsive forms of GS/GOGAT play a central role in the primary assimilation of ammonium in roots (Yamaya and Kusano, 2014). Since the transcripts levels of these isoenzyme-encoding genes increase with ammonium supply, it may be inferred that plants have a transcriptional network to regulate their gene expression in response to ammonium.

Although much of our knowledge has been focused on gene expression networks associated with nitrate as a signal (Konishi and Yanagisawa et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010; Liseron-Monfils et al., 2013), recent studies also highlight transcriptional networks modulating ammonium responses (Gao et al., 2020; Coleto et al., 2021; Di et al., 2021). WRKY46 is a transcription factor induced by ammonium and regulates ammonium efflux by modulating expression of genes involved in the conjugation of IAA and NUDX9 in Arabidopsis roots (Di et al., 2021). MYB28 and MYB29 are found as transcription factors whose genetic defects increase sensitivity to ammonium (Coleto et al., 2021). WRKY23 is another transcription factor found to be necessary for adaptation of Arabidopsis to high concentrations of ammonium supply (Gao et al., 2020). Notably, despite the necessity of this transcription factor in ameliorating the ammonium toxicity, its loss of function that led to an increased ammonium accumulation in roots had no significant impact on ammonium responsiveness of GS gene expression (Gao et al., 2020). Thus, we find genetic evidence to support transcriptional regulation of ammonium response and utilization; however, the information is still fragmental, particularly in regard to mechanisms which directly control GS/GOGAT gene expression for ammonium assimilation. Previous studies reveal that rice NADH-GOGAT1 is expressed in response to ammonium (Hirose et al., 1997; Hirose and Yamaya, 1999). In order to test whether ammonium is a direct signal to induce rice NADH-GOGAT1 gene expression, they used methionine sulfoximine (MSX) as an inhibitor of GS. When MSX was given simultaneously with ammonium, rice NADH-GOGAT1 gene expression was not induced. However, when glutamine was given concurrently with MSX, rice NADH-GOGAT1 gene expression increased. These results suggest that rice NADH-GOGAT1 expression is not directly induced by ammonium, but by glutamine or its post-glutamine metabolites (Hirose and Yamaya, 1999). In the present study, we examined whether the responsiveness of Arabidopsis GLN1;2 and NADH-GOGAT to ammonium could be regulated by glutamine or post-glutamine metabolites as in rice.

To investigate transcriptional regulatory mechanisms involved in ammonium assimilation, we previously performed a promoter analysis of the GLN1;2 glutamine synthetase gene of Arabidopsis and identified a 41-bp region required for the ammonium response (Konishi et al., 2017). In the present study, we analyzed the ammonium-responsive promoter regions of GLN1;2 and GLT1, and found a conserved sequence feature for binding a trihelix family transcription factor DF1.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant growth condition and ammonium treatment

Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia-0 (Col-0) accession was used for all experiments. Plants were cultured in a growth chamber controlled at 22°C with 60% relative humidity under 12 hours light and 8 hours dark cycle as described previously (Ishiyama et al., 2004a). The light intensity was 40 µmol m-2 s-1. Plants grown for two weeks under sterile conditions on MGRL (Molecular Genetics Research Laboratory) medium containing 7 mM nitrate as the nitrogen source (Fujiwara et al., 1992) were subjected to nitrogen starvation for three days prior to the treatment and then transferred to the medium without nitrogen or with 10 mM ammonium chloride (Ishiyama et al., 2004a). Roots of wild-type or transgenic Arabidopsis plants treated with ammonium for 6 hours were used for quantitative real time PCR analysis and visualization of GFP reporter activity. Each medium without nitrogen or with 10 mM ammonium chloride was prepared by adding 10 mM potassium chloride or 10 mM ammonium chloride, respectively, to replace 7 mM potassium nitrate in the MRGL medium.

2.2. GLN1;2, GLT1, and GLU2 promoter-green fluorescence protein (GFP) fusion gene constructs for transformation of Arabidopsis plants

The fusion gene constructs with various lengths of GLN1;2 (At1g66200), GLT1 (At5g53460) and GLU2 (At2g41220) promoters were generated as follows. The 5’-intergenic regions upstream of coding sequences of GLN1;2, GLT1 and GLU2 were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from genomic DNA of Arabidopsis Col-0 accession and cloned as promoter fragments to generate the GFP reporter fusion constructs. PCR was carried out using KOD plus DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) and pairs of forward and reverse oligonucleotide ( Table 1 ). The forward primers were designed for amplification of promoter fragments starting 3,583-bp upstream of the translation initiation site of GLN1;2, 2,814-bp, 2,200-bp, 2,100-bp, 2,000-bp, 1,930-bp, 1,730-bp, and 1,050-bp upstream of GLT1, and 1,358-bp upstream of GLU2. Among these forward primers, GLN1;2P3583L_F designed for the amplification of GLN1;2 promoter region has an overhang of a HindIII site (AAGCTT) at the 5’-end. The rest of the forward primers designed for the amplification of GLT1 and GLU2 promoter regions have an overhang of a BamHI site (GGATCC) at the 5’-end. The reverse primers were designed to have the complementary sequences with the 5’-untranslated regions immediately upstream of the translation initiation sites of GLN1;2, GLT1 and GLU2. These reverse primers have an overhang of an NcoI site (CCATGG) at the 5’-end. The ATG in the NcoI site is the translation initiation site for GFP. The amplified PCR products were subcloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K., Tokyo, Japan), and fully sequenced to confirm the identity. These promoter fragments were then cut out as a HindIII-NcoI fragment (for GLN1;2) or BamHI-NcoI fragments (for GLT1 and GLU2) and cloned into respective restriction sites of pTH-10KI, replacing the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter, to obtain the promoter:GFP:teminator cassettes. pTH-10KI is the modified version of CaMV35S-synthetic GFP (sGFP, S65T) vector(Chiu et al., 1996; Niwa et al., 1999) and has a full EGFP coding sequence (Takara Bio Inc. Shiga, Tokyo) between the 35S promoter and the nopaline synthase terminator (NosT). Finally, the promoter:GFP : NosT cassettes created in pTH-10KI were cut out as a HindIII-EcoRI fragment (for GLN1;2) or BamHI-EcoRI fragments (for GLT1 and GLU2) and cloned into pBI101 (Takara Bio Inc.). These binary vector plasmids were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 (pMP90) by freeze-thaw method as previously described (Ishiyama et al., 2004a). Arabidopsis plants were transformed according to the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Transgenic plants were selected on GM medium (Valvekens et al., 1988) containing 50 mg/L kanamycin sulfate. Kanamycin-resistant T2 progenies were used for analyses.

Table 1.

Primers used for vector construction in this study.

| Name | Gene | Direction | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLN1;2P3583L_F | GLN1;2 | Forward | 5’- GAAGCTTTTACCACATTGTTTAATTGTTTCTTAAC-3’ |

| NGP2814L_F | NADH-GOGAT | Forward | 5’-GGGATCCTCGATAGATGAGGTGGACAGATTCATAGG-3’ |

| NGP2200L_F | NADH-GOGAT | Forward | 5’-GGGATCCTCGTCAACTTTTTGGATGCATAGTTCGAT-3’ |

| NGP2100L_F | NADH-GOGAT | Forward | 5’-GGGATCCTAAGAAGTCATTAAAATTATATAATATTA-3’ |

| NGP2000L_F | NADH-GOGAT | Forward | 5’-GGGATCCTTAATTCTTGAAAGGGTCAACATTTTGTT-3’ |

| NGP1930L_F | NADH-GOGAT | Forward | 5’-GGGATCCTTAAGTATTTAACTAATGTCGTAAGATTA-3’ |

| NGP1730L_F | NADH-GOGAT | Forward | 5’-GGGATCCAGCTTGACTATGAAACGTATCAAATTAGT-3’ |

| NGP1050L_F | NADH-GOGAT | Forward | 5’-GGGATCCCTTAAATTTCTTAAATTATACATATATAT-3’ |

| NGP_R | NADH-GOGAT | Reverse | 5’-GCCATGGTTTTTAGGTTACGGAATCAGCAGTGAGT-3’ |

| FD2P1360_F | Fd-GOGAT2 | Forward | 5’-CGGATCCGATGGTCTCAAGTTGTCTCTGGCGTTTT-3’ |

| FD2P_R | Fd-GOGAT2 | Reverse | 5’-GCCATGGGGAATGAAGCTCCTGAGAAGAAACGCCG-3’ |

2.3. Visualizations of GFP in transgenic Arabidopsis roots

GFP visualizations in whole plants transformed with the promoter:GFP gene constructs were performed as described previously (Maruyama-Nakashita et al., 2004). Expression of GFP in transgenic plants was visualized using an image analyzer FluorImager 595 under 488 nm excitation (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). GFP and autofluorescence of the plant were detected by 530DF30 and 610RG filters, respectively (Maruyama-Nakashita et al., 2005). Relative intensity of GFP signals was quantified with IMAGEQUANT software (Molecular Dynamics). Fluorescence of GFP in transgenic plants were observed under a BX61 microscope equipped with a FV500 confocal laser scanning system and 505-525-nm band pass filter (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), as described previously (Ishiyama et al., 2004a).

2.4. Quantitative real time PCR analysis

Extraction of total RNA, reverse transcription, and real-time PCR were performed as described previously (Maruyama-Nakashita et al., 2004). Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and treated with DNaseI (Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K.). Reverse transcription was carried out using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K.) with oligo-d(T)12-18 priming. Real time PCR was carried out using SYBR green PCR master mix and GeneAmp 5700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Gene specific primer pairs used are shown in Table 2 . Calculation of mRNA contents was carried out using UBQ2 (At2g36170) as a constitutive internal control.

Table 2.

Primers used for RT-qPCR in this study.

| Name | Gene | Direction | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFP_RF | GFP | Forward | 5’-CTACGGCAAGCTGACCCTGAAGTT-3’ |

| GFP_RR | GFP | Reverse | 5’-AGGACCATGTGATCGCGCTTCTC-3’ |

| GLN1;2_RF | GLN1;2 | Forward | 5’-TGTTAACCTTGACATCTCAGACAACAGT-3’ |

| GLN1;2_RR | GLN1;2 | Reverse | 5’-ACTTCAGCAATAACATCAGGGTTAGCA-3’ |

| NG_RF | NADH-GOGAT | Forward | 5’-AGTTGGGAGAAGGATGAAACCGGGAGG-3’ |

| NG_RR | NADH-GOGAT | Reverse | 5’-TTGTAGCTTGGCGTCTTCGTCATCATCC-3’ |

| FG2_RF | Fd-GOGAT2 | Forward | 5’-GTTGAAGGCACTGGAGATCATTGCTGTG-3’ |

| FG2_RR | Fd-GOGAT2 | Reverse | 5’-ATCATTGCCCCTTTGCTGCTTCCCGTTT-3’ |

| UBQ2-144F | UBQ2 | Forward | 5’-CCAAGATCCAGGACAAAGAAGGA-3’ |

| UBQ2-372R | UBQ2 | Reverse | 5’-TGGAGACGAGCATAACACTTGC-3’ |

2.5. Yeast one-hybrid screening

Yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) screening was performed using the Matchmaker Gold Yeast One-Hybrid Library Screening System (Takara Bio Inc.). The 41 bp ammonium-responsive region (–3,604 to –3,564-bp) found in the GLN1;2 promoter was used as a bait fragment. The bait fragment was cloned into the pAbAi vector (Takara Bio Inc.). The vector was linearized with BbsI and subsequently transferred to Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain Y1H Gold with a LiAc method. Auto-activation was checked by the growth of the bait strain on the medium containing various concentration of Aureobasidin A (AbA). The prey library used in this study was the complete Arabidopsis transcription factor collection (Mitsuda et al., 2010). Approximately 3.7 × 104 transformants were initially screened on SD/−Leu medium containing 500 ng mL−1 AbA for 5 days at 30°C to test the possible interaction. Preys were identified from the positive colonies by DNA sequencing.

3. Results

3.1. Expression profile of three GOGAT genes (GLU1, GLU2 and GLT1) in various organs of Arabidopsis

Arabidopsis has three GOGAT genes which are the NADH-dependent GOGAT coded by GLT1 and two ferredoxin (Fd)-dependent GOGAT coded by GLU1 and GLU2 in its genome. The qPCR analysis showed that GLT1 was the major GOGAT expressed in Arabidopsis roots in addition stems, flowers, and siliques when the plants were grown hydroponically ( Figure S1A ). In contrast, GLU1 was mainly expressed in young rosette and matured leaves ( Figure S1A ). GLU2 was expressed in both roots and aboveground tissues, while the amount of the transcripts was lower than the other two GOGAT ( Figure S1A ). Our previous study indicates that GLN1;2 is the only form of GS showing increased expression in roots in response to ammonium supply among the five cytosolic GS (GS1: GLN1;1 – GLN1;5) and one plastidial GS (GS2: GLN2) in Arabidopsis (Ishiyama et al., 2004a). To test whether expression of the three GOGAT genes is stimulated by exogenous supply of ammonium, nitrogen-starved Arabidopsis seedlings were exposed to 10 mM ammonium chloride for 6 hours as described previously (Ishiyama et al., 2004a) ( Figure S1B ). Relative to no nitrogen control, the transcript level of GLT1 encoding the NADH-GOGAT significantly increased in roots in response to ammonium ( Figure S1B ). Thus, the ammonium response of gene expression was similar between GLT1 ( Figure S1B ) and GLN1;2 (Ishiyama et al., 2004a). In contrast, the transcript levels of GLU1 and GLU2 encoding the Fd-GOGAT did not change when ammonium was supplied to the roots of nitrogen-starved seedlings ( Figure S1B ).

3.2. Cell type-specific expression of GLN1;2 and GLT1 in Arabidopsis Roots

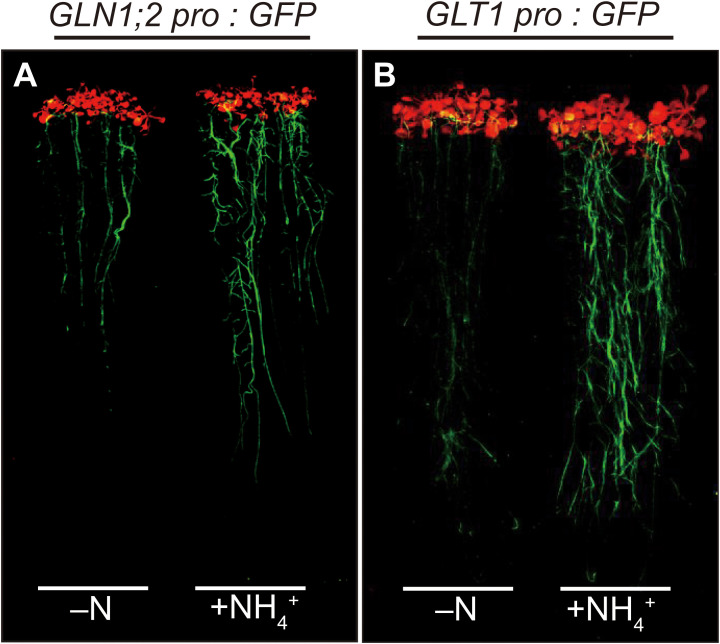

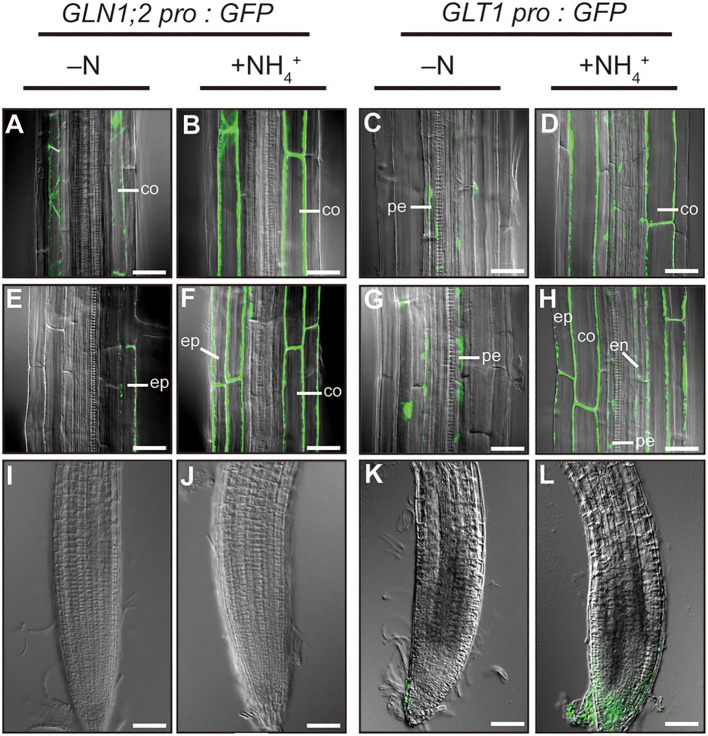

To investigate cell-type specific ammonium responses of GLN1;2 and GLT1 expression in Arabidopsis, transgenic lines carrying the GLN1;2 or GLT1 promoter:GFP fusion gene constructs were grown with or without ammonium supply ( Figure 1 ). Five independent transgenic lines expressing GFP under control of 5,697-bp GLN1;2 promoter (Konishi et al., 2017) and 2,814-bp GLT1 promoter, respectively, were analyzed to assess their ammonium response in roots. Fluorescence scanning of whole seedlings revealed marked increase in the intensity of GFP signals in roots of both transgenic lines with 6 hours of ammonium treatment following nitrogen starvation ( Figure 1 ). Based on these findings, we carried out confocal laser microscopy analyses of these transgenic lines to identify cell types of the roots where the promoter activity of GLN1;2 and GLT1 are present and can be seen as fluorescence of GFP. Under the control of the GLN1;2 promoter, only faint signals of GFP were detected in the epidermis of elongation zone as well as in the cortex of mature zone of roots when there was no nitrogen supply ( Figures 2A, E ). In contrast, strong GFP signals were detected upon ammonium supply, located specifically in the cortex of the mature zone ( Figure 2B ) and in the epidermis and cortex of the elongation zone of roots ( Figure 2F ). In the GLT1 promoter:GFP lines, fluorescent signals derived from GFP expression were present in the pericycle cells of both elongation and mature zones of roots with no nitrogen supply ( Figures 2C, G ), although even stronger signals were detected in the cortex of matured zone ( Figure 2D ) and in the epidermis and cortex of elongation zone of roots ( Figure 2H ) upon ammonium supply. In root tips, almost no or very faint GFP signals were detected in both promoter:GFP lines ( Figures 2I–L ). These results show that both GLN1;2 and GLT1 are expressed in the surface cell layers of roots, particularly in the epidermis and cortex of roots in response to ammonium supply.

Figure 1.

Induction of GFP accumulation in GLN1;2 promoter:GFP and GLT1 promoter:GFP lines in response to ammonium supply. The promoter:GFP lines for GLN1;2 and GLT1 were germinated and grown on MGRL agar media for 2 weeks, transferred to media without nitrogen (–N) and subjected to nitrogen starvation for 3 days prior to the treatment, and then transferred again to the MGRL media without nitrogen (–N) or with 10 mM ammonium as the sole nitrogen source (+NH4 +). For the promoter constructs, 5,697-bp GLN1;2 promoter region (A) and 2,814-bp GLT1 promoter region (B) upstream of their translation initiation sites were used. The fluorescence of GFP was visualized using FluorImager. At least five independent transgenic lines for each promoter:GFP construct were examined.

Figure 2.

Cell type-specific expression of GLN1;2 and GLT1 genes in Arabidopsis roots. The promoter:GFP lines for GLN1;2 (5,697-bp promoter) and GLT1 (2,814-bp promoter) were grown and subjected to ammonium treatment as described in Figure 1 . Whole-mount images from root tips (I–L), elongation zones (E–H) and mature zones (A–D) of roots were taken by confocal scanning microscopy. At least five independent transgenic lines for each promoter: GFP construct were examined. co, cortex; en, endodermis; ep, epidermal; pe, pericycle cell. Bar = 50 µm (I–L) and 25 µm (A–H).

3.3. MSX treatment

Since glutamine (or a post-glutamine metabolite) has been shown to induce NADH-GOGAT1 expression in rice (Hirose and Yamaya, 1999), we used methionine sulfoximine (MSX), an inhibitor of GS, to investigate whether Arabidopsis GS/GOGAT also fluctuates in expression depending on glutamine or a post-glutamine metabolite. The qPCR analysis was carried out in the presence or absence of 10 mM MSX. As shown previously (Ishiyama et al., 2004a) and in Figure S1 , a substantial increase in GLN1;2 and GLT1 expression was observed at 6-h after ammonium supply in the roots, but this increase was not observed when MSX was added prior to ammonium supply ( Figure S2 ). Over approximately 3-fold increase in GLN1;2 and GLT1 expression was observed after glutamine supply regardless of the MSX pre-treatment ( Figure S2 ). The expression of GLU2 and UBQ2 was stable after ammonium and glutamine supply with or without MSX ( Figure S2 ).

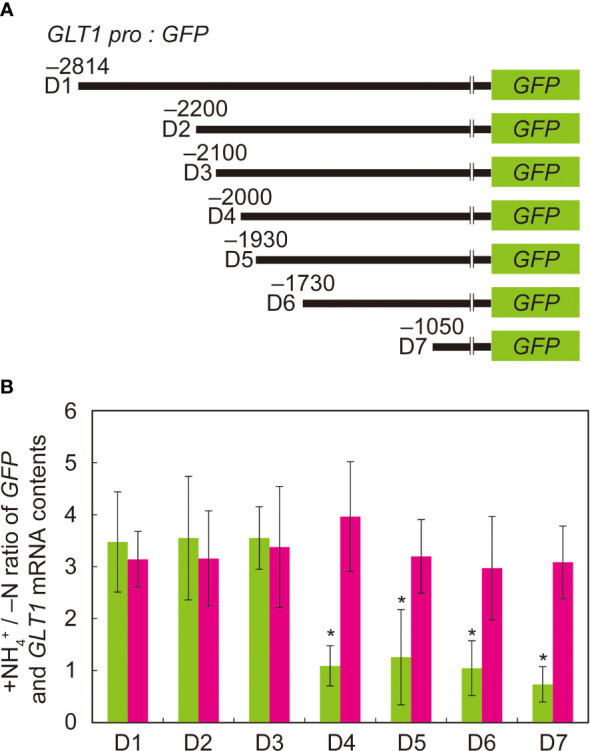

3.4. Identification of ammonium-responsive regions (ARR) in GLT1 promoter

To determine the “ammonium-responsive region” (ARR) in the 5’-intergenic region upstream of the translation initiation site of GLT1, we created a 5’-deletion series of GLT1 promoter:GFP fusion constructs and introduced them into Arabidopsis by Agrobacterium infection. D1, D2, D3, D4, D5, D6 and D7 are the fusion constructs generated to have the GLT1 promoter regions from positions –2,814, –2,200, –2,100, –2,000, –1,930, –1,730 and –1,050 bp, respectively, cloned in front of GFP ( Figure 3A ). Transgenic plants generated with these constructs were grown with or without ammonium supply. Among them, D1, D2 and D3 showed 3.5-fold increase in GFP mRNA levels on ammonium compared to no nitrogen control ( Figure 3B ). In contrast, D4, D5, D6 and D7 showed no induction of GFP expression in response to ammonium ( Figure 3B ). The endogenous GLT1 mRNA levels increased in response to ammonium treatment by 3- to 4-fold relative to no nitrogen control in all GLT1 promoter:GFP lines ( Figure 3B ). Thus, the ammonium-responsive induction of endogenous GLT1 transcript expression was consistent with our previous observation (Konishi et al., 2014).

Figure 3.

Deletion analysis of ammonium-responsive region of GLT1 promoter. (A) Schematic chart of the 5’ deletion of the GLT1 promoter fused to GFP. (B) RT-qPCR analysis of GLT1 and GFP mRNA levels in root tissues of GLT1 promoter: GFP lines. Plants were grown and subjected to ammonium treatment as described in Figure 1 . The letters denote the names of promoter:GFP fusion constructs with various length of GLT1 promoters described in (A): (D1) 2,814-bp, (D2) 2,200-bp, (D3) 2,100-bp, (D4) 2,000-bp, (D5) 1,930-bp, (D6) 1,730-bp, and (D7) 1,050-bp. The ammonium-responsive accumulations of GLT1 (magenta column) and GFP (green column) transcripts were determined based on their relative abundance between the ammonium-treated and no nitrogen control samples (+NH4 +/-N). Means of five to ten independent RNA samples and standard deviations are indicated in the bar graph. Significant differences between GLT1 and GFP were identified by Student’s t-test are indicated with asterisks.

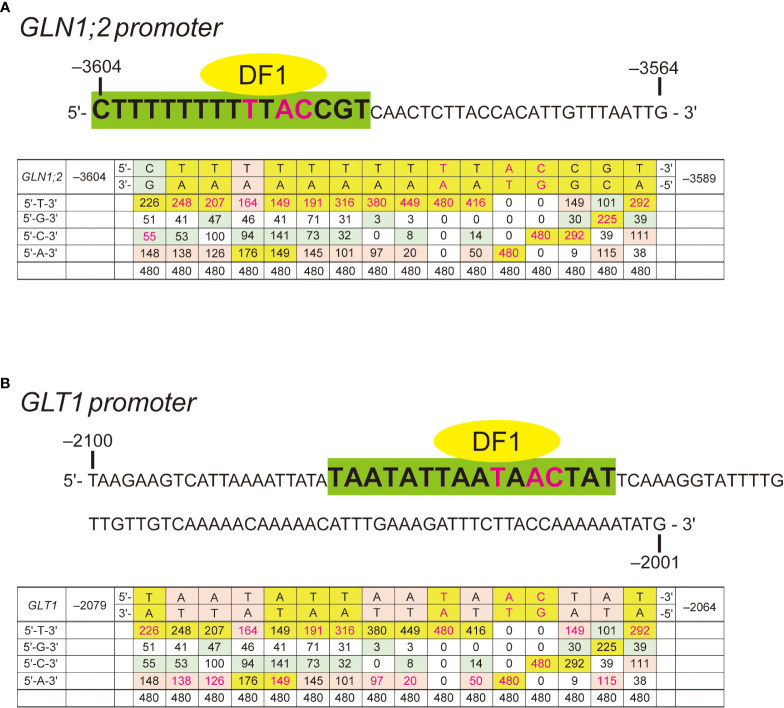

3.5. Trihelix family transcription factor DF1 binds ARR

In our previous study, we found the ARR in the GLN1;2 promoter between the positions –3,604 and –3,564 bp upstream of the translation initiation site (Konishi et al., 2017). To explore potential transcription factor binding sites in the ARR, we performed yeast one-hybrid screening. A GAL4-AD library for yeast one-hybrid system consisting only of Arabidopsis transcription factors (Mitsuda et al., 2010) was screened using the 41-bp region of the GLN1;2 promoter required for the ammonium response (i.e., –3,604 to –3,564 bp) as a decoy sequence. Approximately 3.7 × 104 yeast colonies were screened, and 24 positive clones were obtained, of which 22 gave the insert sequence information ( Table 3 ). Of these 22 Arabidopsis genes identified, 14 were of the AHL family and 3 were DF1. Other transcription factors such as TT16, TTG1, ZFP3, ZFHD2, and LBD22 were also identified as positive clones. Among these transcription factors, a DF1-binding sequences was found between the positions –3,604 and –3,564 bp of GLN1;2 promoter ( Figure 4A ). The DF1-binding sequence was also found within the ARR of GLT1 promoter ( Figure 4B ). AHL and ZFHD2 were predicted to recognize and bind TTTAATT in the decoy sequence ( Figure 4A ). In contrast, binding sites for TT16, TTG1, ZFP3, ZFHD2 and LBD22 were not found in the decoy sequence ( Figure 4A ).

Table 3.

Genes found in yeast one-hybrid screening with ammonium responsive region found in GLN1;2 promoter.

| Clone ID of yeast colonies | Locus ID | name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | AT5G23260 | TT16 |

| 2 | AT4G00200 | AHL7 |

| 3 | AT1G14490 | AHL28 |

| 4 | AT1G76880 | DF1 |

| 5 | AT1G14490 | AHL28 |

| 12 | AT4G35390 | AHL25 |

| 13 | AT3G55560 | AHL15 |

| 19 | AT1G76880 | DF1 |

| 11 | AT3G55560 | AHL15 |

| 15 | AT4G17800 | AHL23 |

| 17 | AT5G24520 | TTG1 |

| 18 | AT1G14490 | AHL28 |

| 20 | AT1G20900 | AHL27 |

| 21 | unknown | IV |

| 22 | AT5G25160 | ZFP3 |

| 23 | AT1G14490 | AHL28 |

| 24 | AT4G17800 | AHL23 |

| 26 | ST1G76880 | DF1 |

| 27 | AT3G55580 | AHL15 |

| 28 | AT3G04570 | AHL19 |

| 29 | AT1G94490 | AHL28 |

| 31 | AT5G65410 | ZFHD2 |

| 32 | AT3G13850 | LBD22 |

| 33 | unknown | IV |

Figure 4.

Ammonium responsive regions (ARRs) with DF1 binding sequence signatures. (A) The 41-bp (–3,604 to –3,564) ARR in the GLN1;2 promoter. A predicted DF1-binding motif (–3604 CTTTTTTTTTTACCGT –3,589) is highlighted in green. (B) The 100-bp (–2,100 to –2,001) ARR in the GLT1 promoter. A predicted DF1-binding motif (–2,079 TAATATTAATAACTAT –2,064) is highlighted in green. The frequency matrix of DF1 was compared to sequences predicted to be recognized by DF1 found within the ammonium-responsive promoter regions of GLN1;2 (A) and GLT1 (B). Frequency matrix was obtained from JASPAR (Castro-Mondragon et al., 2021).

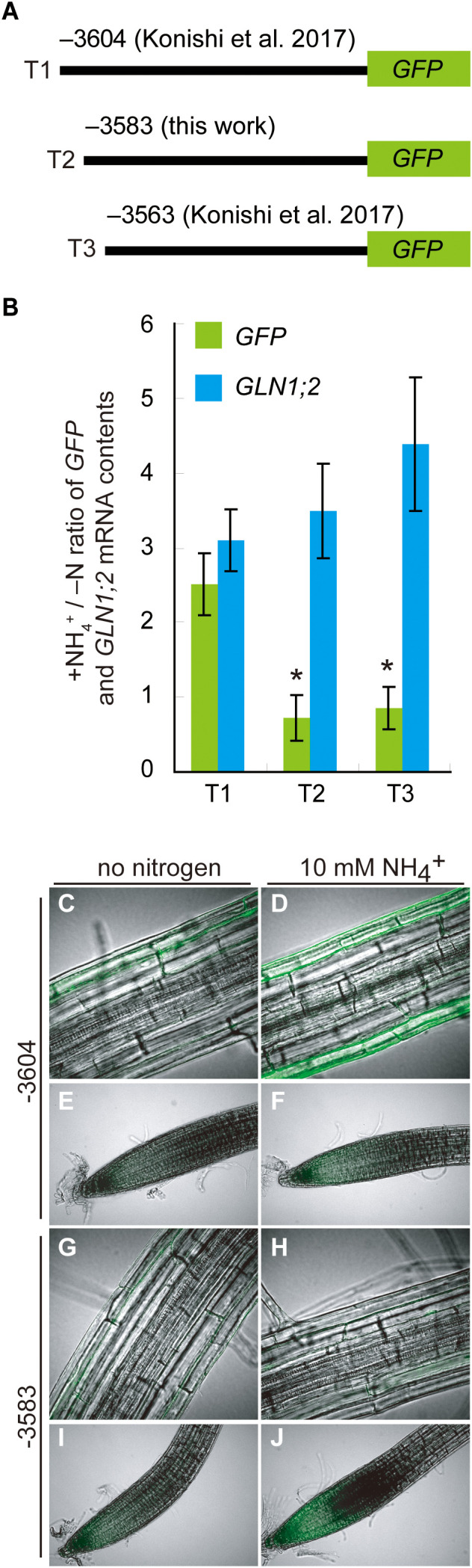

To gain further insights into this ARR, we generated promoter:GFP lines designated T2 with a construct which has the 5’-promoter region of GLN1;2 starting from the position –3,583 bp and lacking the DF1-binding site ( Figures 4A , 5A ). T1 and T3 lines generated previously with the GLN1;2 promoter region with or without the ARR starting from –3,604 and –3,564 bp, respectively, were used in parallel to study the ammonium responsiveness of GFP reporter expression (Konishi et al., 2017). Among these GLN1;2 promoter:GFP lines, only the T1 lines showed a significant increase in GFP mRNA accumulation on ammonium relative to no nitrogen control ( Figure 5B ). In contrast, in the T2 and T3 lines, the ammonium treatment rather resulted in decreasing GFP mRNA accumulation levels down to 0.6- to 0.8-fold of no nitrogen control ( Figure 5B ). In all these GLN1;2 promoter:GFP lines, the endogenous GLN1;2 mRNA levels increased upon ammonium treatment by 3.0 to 4.4-fold relative to no nitrogen control ( Figure 5B ). At the cell-type levels, T1 responded to ammonium and expressed GFP in the epidermis of roots ( Figure 5D ), while T2 did not ( Figure 5H ). In both T1 and T2, the root tip did not respond strongly to ammonium ( Figures 5E, F, I, J ). The cell-type specific patterns of GFP expression identified in T1 lines resembled those with the –5,697 bp GLN1;2 promoter ( Figure 2 ), as both demonstrated strong ammonium response in the epidermis of elongation zone of roots, while they were not exclusively identical in all cell types. These results indicated that the ARR for ammonium-inducible expression is located between the positions –3,604 and –3,583 bp in the GLN1;2 promoter and between –2,100 and –2,001 bp in the GLT1 promoter, respectively.

Figure 5.

Deletion analysis of ammonium responsive region of GLN1;2 promoter. (A) Schematic chart of the 5’ deletion of the GLN1;2 promoter fused to GFP. (B) RT-qPCR analysis of GLN1;2 and GFP mRNA levels in root tissues of GLN1;2 promoter:GFP lines. Plants were grown and subjected to ammonium treatment as described in Figure 1. The letters denote the names of promoter:GFP fusion constructs with various length of GLN1;2 promoters described in (A): (T1) 3,604-bp, (T2) 3,583-bp, and (T3) 3,563-bp. The ammonium-responsive accumulations of GLN1;2 (cyan column) and GFP (green column) transcripts were determined based on their relative abundance between the ammonium-treated and no nitrogen control samples (+NH4 +/–N). Means of five to ten independent RNA samples and standard deviations are indicated. Significant differences between GLN1;2 and GFP were identified by Student’s t-test are indicated with asterisk symbols. (C–J) Cell type-specific expression of GFP in promoter:GFP lines with 3,604-bp and 3,583-bp GLN1;2 promoter regions. Plants were subjected to ammonium treatment (D, F, H, J) or no nitrogen media (C, E, G, I) as described in Figure 1 . Whole-mount images from root tips (E, F, I, J) and elongation zones of roots (C, D, G, H) were taken by confocal scanning microscopy.

4. Discussion

Plants show different adaptations to ammonium environments even within a species, and their responses to ammonium environments are genetically diverse (Sarasketa et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2021). Arabidopsis thrives in oxidative soils, where nitrate is the primary source of nitrogen (Miller et al., 2007). However, some ecotypes of Arabidopsis native to various geographical locations are adapted to ammonium environments (Sarasketa et al., 2014; Yasuda et al., 2017). Previously, we compared the Arabidopsis ecotypes and found three important mechanisms for adaptation to ammonium environments: 1) the rapid response of GS/GOGAT in roots when ammonium is supplied (Yasuda et al., 2017); 2) the development of lateral roots by suppressing main root elongation when ammonium is supplied (Kojima, 2018; Sasaki and Kojima, 2018); and 3) the maintenance of a high capacity for low-affinity ammonium transport (Yasuda et al., 2017). In this study, we focused on ammonium-responsive transcriptional regulation of GS/GOGAT, particularly of GLT1 encoding the NADH-dependent GOGAT and GLN1;2 encoding the cytosolic GS, the two key enzymes for ammonium assimilation in Arabidopsis roots ( Figures 1 , 2 ).

The tissue-specific expression patterns of Arabidopsis genes encoding GOGAT isoenzymes indicate that GLT1 is the most highly expressed GOGAT in Arabidopsis roots ( Figure S1 ). Of two Fd-dependent GOGAT, GLU2 is lowly expressed but GLU1 transcript was hardly detected in roots ( Figure S1 ). GLT1 is the ammonium-inducible form of GOGAT ( Figures 1–3 , S1B ); however, this transcript accumulation is abolished in the presence of a GS inhibitor methionine sulfoximine (MSX) but restored by supplying glutamine ( Figue S2B ). These results suggest that, as with GLN1;2, GLT1 expression is not directly induced by ammonium, but is rather dependent on glutamine or post-glutamine metabolites ( Figure S2 ), as well as OsGS1;2, OsNADH-GOGAT1, and OsAS1 genes in rice (Hirose et al., 1997; Yabuki et al., 2017; Ohashi et al., 2018). In contrast to GLT1, GLU2 does not respond to ammonium in roots ( Figures S1–S3 ). Among these GOGAT, the NADH-GOGAT encoded by GLT1 is suggested as the isoenzyme playing a central role in supplying substrates to GS when ammonium is supplied as the nitrogen source (Konishi et al., 2014). The results shown in our present study support this idea, as the ammonium-supplied Arabidopsis roots display an increased promoter activity of GLN1;2 and GLT1 in the epidermis and cortex in response to ammonium supply, and these cell types where the promoters of the two genes were active overlap significantly ( Figures 1 , 2 ). GS/GOGAT expression in the root surface cell layers in response to ammonium may prevent ammonium from being transported to the vascular tissues (Ishiyama et al., 1998; Konishi et al., 2017). The increase in mRNA accumulation can be attributed to increased transcriptional activity and increased mRNA stability (Hirose and Yamaya, 1999). We found in this study that the increase in GLT1 mRNA levels on ammonium supply is promoter-dependent and likely due to increased transcriptional activity ( Figures 1 – 3 ). NADH-GOGAT1 in rice is also transcriptionally activated upon ammonium supply (Hirose and Yamaya, 1999), and as a result, mRNA (Ishiyama et al., 2003) and protein (Ishiyama et al., 1998) accumulate in root surface cell populations. The expression pattern and ammonium response of NADH-GOGAT appear physiologically relevant and conserved across the plant species.

We have previously shown that a 41-bp sequence in the GLN1;2 promoter is important for this GS isoenzyme to respond to ammonium (Konishi et al., 2017). In this study, we show that the first 20 bp of the 41 bp ARR of the GLN1;2 promoter is particularly important. A GLN1;2 promoter lacking this region was unable to express GFP in the root surface cell layers in response to ammonium ( Figure 5 ). The mode of accumulation of ammonium-responsive GS (OsGS1;2) isoenzymes in root surface cells in response to ammonium is likely a common feature shared in rice (Ishiyama et al., 2004b) and Arabidopsis ( Figures 2 , 5 ). In this study, we isolated several transcription factors by yeast one-hybrid screening using the ARR of GLN1;2 as a decoy sequence. Our findings implicate that ARRs of GS/GOGAT involved in assimilation of ammonium in roots contain a conserved sequence signature to which DF1 binds ( Figure 4 ). DE1 BINDING FACTOR1 (DF1) is a transcription factor that has been shown to regulate adhesive polysaccharides in seeds (Xu et al., 2022) and contribute to root hair formation in roots (Shibata et al., 2018; Shibata et al., 2022). The mucilage surrounding hydrated Arabidopsis seeds is a extracellular matrix composed mainly of the pectic polysaccharide rhamnogalacturonan I (RG-I). DF1 physically interacts with GLABRA2 (GL2) and both proteins transcriptionally regulate the expression of the RG-I biosynthesis genes MUCILAGE MODIFIED4 (MUM4) and GALACTURONOSYLTRANSFERASE-LIKE5 (GATL5) (Xu et al., 2022). The expression of DF1 and GL2 is directly regulated by TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA2 (TTG2) and, in turn, DF1 directly represses the expression of TTG2 (Xu et al., 2022). Shibata et al. (2018) reported that a basic helix-loop helix transcription factor ROOT HAIR DEFECTIVE 6-LIKE 4 (RSL4) promotes, but DF1 and a trihelix transcription factor GT-2-LIKE1 (GTL1) repress root hair growth in Arabidopsis. In addition, transcriptional analysis combined with genome-wide chromatin-binding data showed that DF1 and GTL1 directly bind the RSL4 promoter and regulate its expression to repress root hair growth (Shibata et al., 2018). DF1 is also a transcription factor involved in regulation of nitrogen metabolism (Gaudinier et al., 2018). The networks of transcriptional responses involved in nitrogen utilization in Arabidopsis elucidated by Gaudinier et al. (2018) indicate holistic interactions between transcription factors and promoters of genes involved in nitrogen transport, metabolism, signaling, amino acid metabolism, carbon metabolism, carbon transport, tissue growth, and hormone responses. Their data suggest that DF1 binds to the promoter regions of genes related to nitrogen metabolism, such as NR, NiR, AS1, and nitrate transporter; a group of genes known to respond to ammonium (Kan et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2015; Subudhi et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2021). We predict that DF1 would be a candidate of transcription factors involved in the regulation of GLN1;2 and GLT1, which has not been reported previously (Gaudinier et al., 2018). The promoter regions for GLN1;2 and GLT1 used by Gaudinier et al. (2018) are roughly 2 kbp, not including the ARR found in our present study.

In our yeast one-hybrid screening, various homologs of the AHL family transcription factor were repeatedly isolated. However, we consider it unlikely that AHLs are directly involved in modulating the ammonium responsiveness of GLN1;2. This is because AHLs are predicted to bind TTTAATT, which is located within a non-essential region downstream of the ARR of GLN1;2. ZFHD2 is also predicted to bind TTTAATT. ZFHD2, like AHL, is not expected to be a transcription factor directly involved in ammonium response. TTG1 and LBD22 are known to bind bHLH. The ammonium-responsive sequence of GLN1;2 used a decoy in our yeast one-hybrid screening contains a bHLH binding sequence CAACTC (Konishi et al., 2017). It is possible that TTG1 and LBD22 interacted with the decoy using yeast bHLH as a scaffold. No DNA motifs for TT16 and ZFP3 binding were found within the ARR of GLN1;2. Future analysis of mutants and overexpressors of these transcription factors will help better understand how they interact with GLN1;2 and GLT1 promoter regions to modulate expression of these key enzymes involved in ammonium utilization.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

KI, HT, and SK contributed to conception and design of the study. KI and EI performed the qPCR analysis. KI, EI, and SK performed microscopic analysis. KI, EI, and HT prepared for whole mount GFP image. CY, HM, and SK performed yeast one hybrid screening. KI and SK performed promoter analysis. KI and SK wrote the first draft of the manuscript. HT edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Nobutaka Mitsuda for sharing yeast AD library.

Funding Statement

Japan Advanced Plant Research Network supported by JSPS was also acknowledged for the use of Elemental Analyzer. JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers, 21688006, 26450073, 22K05365 to SK.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2023.1127006/full#supplementary-material

References

- Castro-Mondragon J. A., Riudavets-Puig R., Rauluseviciute I., Berhanu Lemma R., Turchi L., Blanc-Mathieu R., et al. (2021). JASPAR 2022: the 9th release of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 50 (D1), D165–D173. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu W. L., Niwa Y., Zeng W., Hirano T., Kobayashi H., Sheen J. (1996). Engineered GFP as a vital reporter in plants. Curr. Biol. 6 (3), 325–330. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00483-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S. J., Bent A. F. (1998). Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant J. 16 (6), 735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleto I., Bejarano I., Marín-Peña A. J., Medina J., Rioja C., Burow M., et al. (2021). Arabidopsis thaliana transcription factors MYB28 and MYB29 shape ammonium stress responses by regulating fe homeostasis. New Phytol. 229 (2), 1021–1035. doi: 10.1111/nph.16918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di D.-W., Sun L., Wang M., Wu J., Kronzucker H. J., Fang S., et al. (2021). WRKY46 promotes ammonium tolerance in arabidopsis by repressing NUDX9 and indole-3-acetic acid-conjugating genes and by inhibiting ammonium efflux in the root elongation zone. New Phytol. 232 (1), 190–207. doi: 10.1111/nph.17554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T., Hirai M. Y., Chino M., Komeda Y., Naito S. (1992). Effects of sulfur nutrition on expression of the soybean seed storage protein genes in transgenic petunia. Plant Physiol. 99 (1), 263–268. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.1.263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funayama K., Kojima S., Tabuchi-Kobayashi M., Sawa Y., Nakayama Y., Hayakawa T., et al. (2013). Cytosolic glutamine synthetase1;2 is responsible for the primary assimilation of ammonium in rice roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 54 (6), 934–943. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao K., Zhou T., Hua Y., Guan C., Zhang Z. (2020). Transcription factor WRKY23 is involved in ammonium-induced repression of Arabidopsis primary root growth under ammonium toxicity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 150, 90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudinier A., Rodriguez-Medina J., Zhang L. F., Olson A., Liseron-Monfils C., Bagman A. M., et al. (2018). Transcriptional regulation of nitrogen-associated metabolism and growth. Nature 563 (7730), 259–264. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0656-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose N., Hayakawa T., Yamaya T. (1997). Inducible accumulation of mRNA for NADH-dependent glutamate synthase in rice roots in response to ammonium ions. Plant Cell Physiol. 38 (11), 1295–1297. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose N., Yamaya T. (1999). Okadaic acid mimics nitrogen-stimulated transcription of the NADH-glutamate synthase gene in rice cell cultures. Plant Physiol. 121 (3), 805–812. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.3.805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama K., Hayakawa T., Yamaya T. (1998). Expression of NADH-dependent glutamate synthase protein in the epidermis and exodermis of rice roots in response to the supply of ammonium ions. Planta 204 (3), 288–294. doi: 10.1007/s004250050258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama K., Inoue E., Tabuchi M., Yamaya T., Takahashi H. (2004. b). Biochemical background and compartmentalized functions of cytosolic glutamine synthetase for active ammonium assimilation in rice roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 45 (11), 1640–1647. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama K., Inoue E., Watanabe-Takahashi A., Obara M., Yamaya T., Takahashi H. (2004. a). Kinetic properties and ammonium-dependent regulation of cytosolic isoenzymes of glutamine synthetase in arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 279 (16), 16598–16605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313710200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama K., Kojima S., Takahashi H., Hayakawa T., Yamaya T. (2003). Cell type distinct accumulations of mRNA and protein for NADH-dependent glutamate synthase in rice roots in response to the supply of NH4 + . Plant Physiol. Biochem. 41 (6-7), 643–647. doi: 10.1016/S0981-9428(03)00078-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kan C. C., Chung T. Y., Juo Y. A., Hsieh M. H. (2015). Glutamine rapidly induces the expression of key transcription factor genes involved in nitrogen and stress responses in rice roots. BMC Genomics 16 (1), 731. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1892-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima S. (2018). The possible interaction of ammonium and auxin polar transport on root system architectures in the two ecotypes of Arabidopsis thaliana. Soil Sci.Plant Nutri. 64 (5), 616–622. [Google Scholar]

- Kojima S., Ishiyama K., Beier M. P., Hayakawa T. (2020). “Ammonium assimilation and metabolism in rice,” in Progress in botany, vol. 82 . Eds. Cánovas F. M., Lüttge U., Risueño M.-C., Pretzsch H. (Cham: Springer International Publishing; ), 211–231. doi: 10.1007/124_2020_40 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima S., Konishi N., Beier M. P., Ishiyama K., Maru I., Hayakawa T., et al. (2014). NADH-dependent glutamate synthase participated in ammonium assimilation in Arabidopsis root. Plant Signal. Behav. 9 (8), e29402. doi: 10.4161/psb.29402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi N., Ishiyama K., Beier M. P., Inoue E., Kanno K., Yamaya T., et al. (2017). Contribution of two glutamine synthetase isozymes to ammonium assimilation in arabidopsis roots. J. Exp. Bot. 68 (3), 613–625. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi N., Ishiyama K., Matsuoka K., Maru I., Hayakawa T., Yamaya T., et al. (2014). NADH-dependent glutamate synthase plays a crucial role in assimilating ammonium in the arabidopsis root. Physiol. Plantar 152 (1), 138–151. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi N., Saito M., Imagawa F., Kanno K., Yamaya T., Kojima S. (2018). Cytosolic glutamine synthetase isozymes play redundant roles in ammonium assimilation under low-ammonium conditions in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant Cell Physiol. 59 (3), 601–613. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi M., Yanagisawa S. (2010). Identification of a nitrate-responsive cis-element in the arabidopsis NIR1 promoter defines the presence of multiple cis-regulatory elements for nitrogen response. Plant J. 63 (2), 269–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04239.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea P. J., Miflin B. J. (1974). Alternative route for nitrogen assimilation in higher plants. Nature 251 (5476), 614–616. doi: 10.1038/251614a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang T., Yuan Z., Fu L., Zhu M., Luo X., Xu W., et al. (2021). Integrative transcriptomic and proteomic analysis reveals an alternative molecular network of glutamine synthetase 2 corresponding to nitrogen deficiency in rice (Oryza sativa l.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (14). doi: 10.3390/ijms22147674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liseron-Monfils C., Bi Y. M., Downs G. S., Wu W., Signorelli T., Lu G., et al. (2013). Nitrogen transporter and assimilation genes exhibit developmental stage-selective expression in maize (Zea mays l.) associated with distinct cis-acting promoter motifs. Plant Signal. Behav. 8 (10). doi: 10.4161/psb.26056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschner H. (1995). Mineral nutrition of higher plants (London: Academic Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama-Nakashita A., Nakamura Y., Watanabe-Takahashi A., Inoue E., Yamaya T., Takahashi H. (2005). Identification of a novel cis-acting element conferring sulfur deficiency response in arabidopsis roots. Plant J. 42 (3), 305–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02363.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama-Nakashita A., Nakamura Y., Yamaya T., Takahashi H. (2004). A novel regulatory pathway of sulfate uptake in Arabidopsis roots: Implication of CRE1/WOL/AHK4-mediated cytokinin-dependent regulation. Plant J. 38 (5), 779–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02079.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. J., Fan X. R., Orsel M., Smith S. J., Wells D. M. (2007). Nitrate transport and signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 58 (9), 2297–2306. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuda N., Ikeda M., Takada S., Takiguchi Y., Kondou Y., Yoshizumi T., et al. (2010). Efficient yeast one-/two-hybrid screening using a library composed only of transcription factors in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant Cell Physiol. 51 (12), 2145–2151. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito S., Hirai M. Y., Chino M., Komeda Y. (1994). Expression of a soybean (Glycine max [L.] merr.) seed storage protein gene in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana and its response to nutritional stress and to abscisic acid mutations. Plant Physiol. 104 (2), 497–503. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.2.497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa Y., Hirano T., Yoshimoto K., Shimizu M., Kobayashi H. (1999). Non-invasive quantitative detection and applications of non-toxic, S65T-type green fluorescent protein in living plants. Plant J. 18 (4), 455–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00464.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi M., Ishiyama K., Kojima S., Konishi N., Sasaki K., Miyao M., et al. (2018). Outgrowth of rice tillers requires availability of glutamine in the basal portions of shoots. Rice 11 (31). doi: 10.1186/s12284-018-0225-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarasketa A., González-Moro M. B., González-Murua C., Marino D. (2014). Exploring ammonium tolerance in a large panel of arabidopsis thaliana natural accessions. J. Exp. Bot. 65 (20), 6023–6033. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki K., Kojima S. (2018). Identification of genomic regions regulating ammonium-dependent inhibition of primary root length in Arabidopsis thaliana . Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 64 (6), 746–751. doi: 10.1080/00380768.2018.1524268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M., Breuer C., Kawamura A., Clark N. M., Rymen B., Braidwood L., et al. (2018). GTL1 and DF1 regulate root hair growth through transcriptional repression of ROOT HAIR DEFECTIVE 6-LIKE 4 in Arabidopsis . Development 145 (3). doi: 10.1242/dev.159707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M., Favero D. S., Takebayashi R., Takebayashi A., Kawamura A., Rymen B., et al. (2022). Trihelix transcription factors GTL1 and DF1 prevent aberrant root hair formation in an excess nutrient condition. New Phytol. 235 (4), 1426–1441. doi: 10.1111/nph.18255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subudhi P. K., Garcia R. S., Coronejo S., Tapia R. (2020). Comparative transcriptomics of rice genotypes with contrasting responses to nitrogen stress reveals genes influencing nitrogen uptake through the regulation of root architecture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (16). doi: 10.3390/ijms21165759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi M., Abiko T., Yamaya T. (2007). Assimilation of ammonium ions and reutilization of nitrogen in rice (Oryza sativa l.). J. Exp. Bot. 58 (9), 2319–2327. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura W., Hidaka Y., Tabuchi M., Kojima S., Hayakawa T., Sato T., et al. (2010). Reverse genetics approach to characterize a function of NADH-glutamate synthase1 in rice plants. Amino Acids 39 (4), 1003–1012. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0531-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valvekens D., Vanmontagu M., Vanlijsebettens M. (1988). Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana root explants by using kanamycin selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85 (15), 5536–5540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Mas I., Cukier C., Coleto I., González-Murua C., Limami A. M., González-Moro M. B., et al. (2019). Isotopic labelling reveals the efficient adaptation of wheat root TCA cycle flux modes to match carbon demand under ammonium nutrition. Sci. Rep. 9 (1). doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45393-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Guan P., Chen M., Xing X., Zhang Y., Crawford N. M. (2010). Multiple regulatory elements in the arabidopsis NIA1 promoter act synergistically to form a nitrate enhancer. Plant Physiol. 154 (1), 423–432. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.162586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Wang Y., Du J., Pei S., Guo S., Hao R., et al. (2022). A DE1 BINDING FACTOR 1–GLABRA2 module regulates rhamnogalacturonan I biosynthesis in arabidopsis seed coat mucilage. Plant Cell 34 (4), 1396–1414. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koac011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuki Y., Ohashi M., Imagawa F., Ishiyama K., Beier M. P., Konishi N., et al. (2017). A temporal and spatial contribution of asparaginase to asparagine catabolism during development of rice grains. Rice 10, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12284-017-0143-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaya T., Kusano M. (2014). Evidence supporting distinct functions of three cytosolic glutamine synthetases and two NADH-glutamate synthases in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 65 (19), 5519–5525. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.-y., Hao D.-l., Song Z.-z., Yang G.-z., Wang L., Su Y.-h. (2015). RNA-Seq analysis of differentially expressed genes in rice under varied nitrogen supplies. Gene 555 (2), 305–317. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda T., Konishi N., Kojima S. (2017). Ammonium uptake capacity and response of cytosolic glutamine synthetase 1;2 to ammonium supply are key factors for the adaptation of ammonium nutrition in arabidopsis thaliana. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 63 (6), 553–560. doi: 10.1080/00380768.2017.1395292 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T., Hua Y., Yue C., Huang J., Zhang Z. (2021). Physiologic, metabolomic, and genomic investigations reveal distinct glutamine and mannose metabolism responses to ammonium toxicity in allotetraploid rapeseed genotypes. Plant Sci. 310, 110963. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2021.110963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.