Abstract

Limited evidence describing how host genetic variants affect the composition of the microbiota is currently available. The aim of this study was to assess the associations between a set of candidate host genetic variants and microbial composition in both saliva and gut in the TwinsUK registry. A total of 1,746 participants were included in this study and provided stool samples. A subset of 1,018 participants also provided self-reported periodontal data, and 396 of those participants provided a saliva sample. Host DNA was extracted from whole-blood samples and processed for Infinium Global screening array, focusing on 37 selected single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) previously associated with periodontitis. The gut and salivary microbiota of participants were profiled using 16S ribosomal RNA amplicon sequencing. Associations between genotype on the selected SNPs and microbial outcomes, including α diversity, β diversity, and amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), were investigated in a multivariate mixed model. Self-reported periodontal status was also compared with microbial outcomes. Downstream analyses in gut microbiota and salivary microbiota were carried out separately. IL10 rs6667202 and VDR 2228570 SNPs were associated with salivary α diversity, and SNPs in IL10, HSA21, UHRF2, and Fc-γR genes were associated with dissimilarity matrix generated from salivary β diversity. The SNP that was associated with the greatest number of salivary ASVs was VDR 2228570 followed by IL10 rs6667202, and that of gut ASVs was NPY rs2521364. There were 77 salivary ASVs and 39 gut ASVs differentially abundant in self-reported periodontal disease versus periodontal health. The dissimilarity between saliva and gut microbiota within individuals appeared significantly greater in self-reported periodontal cases compared to periodontal health. IL10 and VDR gene variants may affect salivary microbiota composition. Periodontal status may drive variations in the salivary microbiota and possibly, to a lesser extent, in the gut microbiota.

Keywords: bacteria, genetics, microbiome, periodontal disease(s)/periodontitis, infectious disease(s), saliva

Introduction

In periodontitis, inflammation is thought to drive a progressive decrease in microbial diversity, leading to perturbations in the microenvironment, such as increased availability of substrates for growth of Gram-negative bacteria (Hajishengallis and Lamont 2012). The effect of less diverse microbial communities on inflammation and barrier function can ultimately lead to periodontal disease onset and progression (Curtis et al. 2020).

It is now clear that host genetic variants contribute to the risk of periodontitis (Schaefer et al. 2014), although there is still lack of consensus on predisposing single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (Nibali et al. 2016). Some of the impact excreted by host genetic variants on disease is mediated by an effect on subgingival microbial communities, following the concept of “infectogenomics” (Kellam and Weiss 2006). Data have emerged on how host genetic variants may affect the presence and abundance of specific bacteria in the subgingival niche (Socransky et al. 2000; Nibali et al. 2007), presumably by affecting the host’s ability to resolve the self-perpetuating cycle of dysbiosis and inflammation generated by a microbial trigger (Nibali et al. 2014). For example, animal models suggest an increase in gut dysbiosis in the presence of predisposing proinflammatory genotypes (Craven et al. 2012). The current concept is that the human gut microbiota is relatively subject specific, with variations in the Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio mainly associated with inflammatory bowel disease obesity or changes in diet (Boulange et al. 2016). Monozygotic twins have more similar gut microbiotas than do dizygotic twins, suggesting that genetic factors influence the gut microbiota (Turnbaugh et al. 2009; Goodrich et al. 2014, 2016; Kurilshikov et al. 2021). Any changes in the gut microbiota may have important systemic consequences, since the gut microbiota is central to human health, providing important metabolic and immunological functions (Bermudez 2016). Some studies are now suggesting that oral bacteria may affect the gut microbiota (Lourenvarsigmao et al. 2018; Olsen and Yamazaki 2019) in ways that can affect host health.

The salivary microbiota associated with periodontitis mirrors what is observed in the subgingival microbiota, suggesting that periodontopathogens detected in saliva may be spillover from the subgingival microbiota (Belstrom et al. 2018). However, while studies have focused on associations between host genetic variants and subgingival microbes, very little evidence has been gathered on the potential effect of host genetic variants in influencing the salivary microbiota. To address this gap in understanding, we analyzed associations between a subset of host genetic variants associated with periodontitis and the salivary and gut microbiota in the TwinsUK Registry.

Materials and Methods

This article follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines for strengthening the reporting of observational studies.

Study Population

Study participants consisted of twins with a mean age of 61.49 y (Table 1), enrolled in TwinsUK (Verdi et al. 2019). Participants’ rights have been protected by an appropriate institutional review board, and written informed consent was granted prior to the study. Self-reported periodontal disease was defined as at least 1 positive answer to the following questions: “Do your gums bleed when you brush your teeth?” “Do you have any loose teeth?” and “Have you ever been told by a dentist or hygienist that you have gum disease?”

Table 1.

Demographic Information for the Study Participants.

| Characteristic | Total Sample (Gut Microbial Data) (N = 1,746) | Sample with Self-Reported Periodontal Data (N = 1,031) | Sample with Salivary Microbial Data (N = 396) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 61.49 ± 10.51 | 60.69 ± 10.02 | 61.06 ± 9.21 |

| Body mass index, mean ± SD, kg/m2 | 26.24 ± 4.82 | 26.28 ± 4.88 | 26.1 ± 4.64 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 1,613 (92.4) | 931 (90.4) | 376 (94.9) |

| Ethnicity: Caucasian, n (%) | 1,730 (100) | 1,020 (100) | 392 (100) |

| Monozygous, n (%) | 726 (41.7) | 412 (40) | 159 (40.2) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Never smoker | 670 (38.4) | 394 (38.2) | 157 (39.6) |

| Current smoker | 151 (8.6) | 92 (8.9) | 30 (7.6) |

| Former smoker | 322 (18.4) | 196 (19) | 71 (17.9) |

| Not recorded | 594 (34.0) | 351 (34.0) | 138 (34.8) |

| Type 2 diabetes, n (%) | |||

| Positive | 84 (4.9) | 48 (4.7) | 21 (5.3) |

| Negative | 339 (19.4) | 199 (19.3) | 73 (18.4) |

| Not recorded | 1,323 (76.7) | 784 (76) | 302 (76.3) |

Microbiome Profiling

Saliva samples

Participants were instructed not to eat, drink, smoke, or chew gum for at least 1 h prior to producing saliva. Saliva samples were collected into a 50-mL tube until the amount reached 5 mL. Samples were immediately refrigerated, then frozen at −80°C and shipped to Stanford University on dry ice at −40°C. DNA was extracted using the DNeasy PowerSoil HTP 96 DNA extraction kit (Qiagen). The V4 hypervariable region of the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene was polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified in triplicate using bacterial specific primers (515F and 806R) that include error-correcting barcodes and Illumina adapters. Samples were then pooled in equimolar ratios before being sequenced on 2 lanes of an Illumina HiSeq 250000 platform.

Stool samples

Collection and processing of stool samples has been previously described (Goodrich et al. 2014). Briefly, participants collected stool samples at home, which were refrigerated for up to 2 d prior to their clinical visit at TwinsUK. Stool samples, received from participants, were immediately stored at −80°C, then shipped to Cornell University. DNA extraction was performed and the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified. Sequencing was performed using an Illumina MisSeq platform (Caporaso et al. 2010).

Genotype Profiling

Blood samples, obtained during the clinical visit, were genotyped using the Illumina HumanHap300 BeadChip and the Illumina HumanHap610 QuadChip.

Choice of Target SNP Panel

A group of 37 SNPs across 25 genes was selected based on previous systematic reviews of genes associated with periodontitis and with the subgingival microbiota (Nibali et al. 2016, 2017), complemented by recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and periodontal infectogenomics studies (Divaris et al. 2012; Divaris et al. 2013; Shusterman et al. 2013; Rhodin et al. 2014; Shusterman et al. 2017; Munz et al. 2017, 2018; Cavalla et al. 2018). The list mainly includes genes with functions on microbial recognition and host response, although some genes with yet unclear function are also included.

Statistical Analysis

All the analyses were performed with statistical software R version 4.0.3. The investigated outcomes were as follows:

- Microbial diversity and dissimilarity (saliva and gut microbiota)

- Amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) (saliva and gut microbiota)

- Presence of self-reported periodontal disease

For bacterial taxonomic identification, ASVs were generated from the Twins UK data set, using the DADA2 pipeline (version 1.0.3). Samples with fewer than 10,000 raw sequencing reads were excluded, and ASVs below 5% prevalence were removed from the data set. The α diversity was calculated by vegan package (version 2.5-7). Both Simpson and Shannon indices were based on the raw ASV counts. These 2 metrics reflect different aspects of α diversity; the Simpson index takes the proportion of species into account, while the Shannon index considers both richness and evenness of the microbial community. Log normalization was applied to raw ASVs for further analysis. The β diversity ordination was generated by applying Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to Aitchison distance, calculated from Euclidean distance after centered log ratio transform.

Associations between selected genetic variants and microbial outcomes (α diversity and ASVs) were assessed by a generalized linear mixed model (R package MCMCglmm, version 2.32) adjusted for confounders including age, body mass index (BMI), sequencing depth, storage time, and self-reported periodontal status as fixed effects and zygosity and family structure as random effects. Bonferroni corrections for multiple testing were used accordingly, lowering the α value to 0.002. Since some of the tested SNPs are located in the same region of a gene, resulting in strong linkage disequilibrium, 25 independent tests were assumed for each microbial outcome. No adjustments for sex and ethnicity were performed, since >92% of participants were Caucasian females (Table 1). Compositional differences of microbiota in genotypes were assessed using permutational multivariate analysis adjusting for age and storage time of variance (PERMANOVA) applied to the Aitchison distance matrix. R package vegan version 2.5-7 was used for adonis function to perform PERMANOVA, and phyloseq version 1.16.2 was used for multidimensional microbial data. Significance was set as P = 0.05 for the above tests.

To analyze the association between self-reported periodontal status and microbial outcomes (α diversity and ASVs), age, BMI, storage time, and sequencing depth (fixed effects), as well as family and zygosity (random effects), were used as covariates. Compositional difference of microbiota in self-reported periodontal status was analyzed in the method addressed above.

Differences between saliva and gut microbiota in relation to self-reported periodontal status were also independently investigated. Dissimilarities between saliva and gut microbiota were extracted from a Euclidean distance matrix of the normalized ASV counts and fitted with a generalized logistic regression adjusting for age and time difference between saliva and stool sample collection.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The initial analysis included 1,746 participants with available data on host genetic analysis and gut microbial outcomes. A subset of 1,018 participants had self-reported periodontal outcomes. Salivary microbial data were available for 396 participants, of whom 322 provided self-reported periodontal outcomes. Demographic characteristics of participants are reported in Table 1. Most were female (92.4%), with an average age of 61.5 (±10.5) years and an average BMI of 26.2 (±4.8) kg/m2. Genotype distributions for each SNP are shown in Appendix Figure 1. A total of 46.8% subjects were classified as having self-reported periodontal disease (Appendix Table 1). The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was satisfied for most SNPs in the whole sample (n = 1,746), except for PKN2 rs12032672, Fc-γR rs1011108, ANRIL rs1333048, VDR rs2228570, and NPY rs2521364 (P < 0.05).

Microbiome Data

A total of 736 ASVs were identified in gut samples from all included individuals (n = 1,746 participants). In subjects who provided saliva samples (n = 396), 431 ASVs were identified. Taxonomic information for salivary and gut microbiome is provided in Appendix Table 2 and Appendix Table 3, respectively.

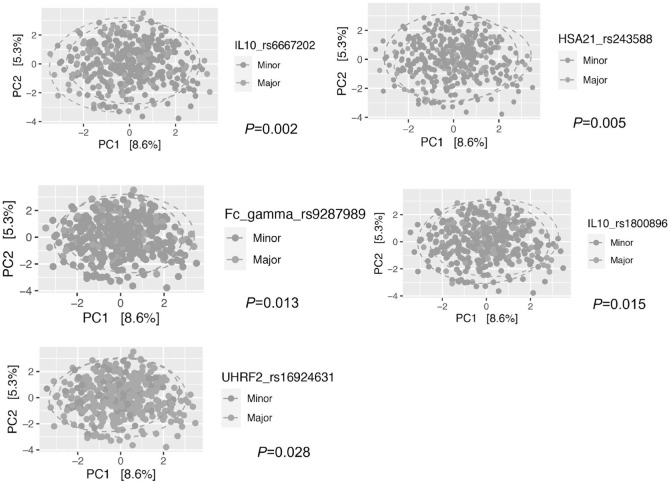

Microbial Diversity

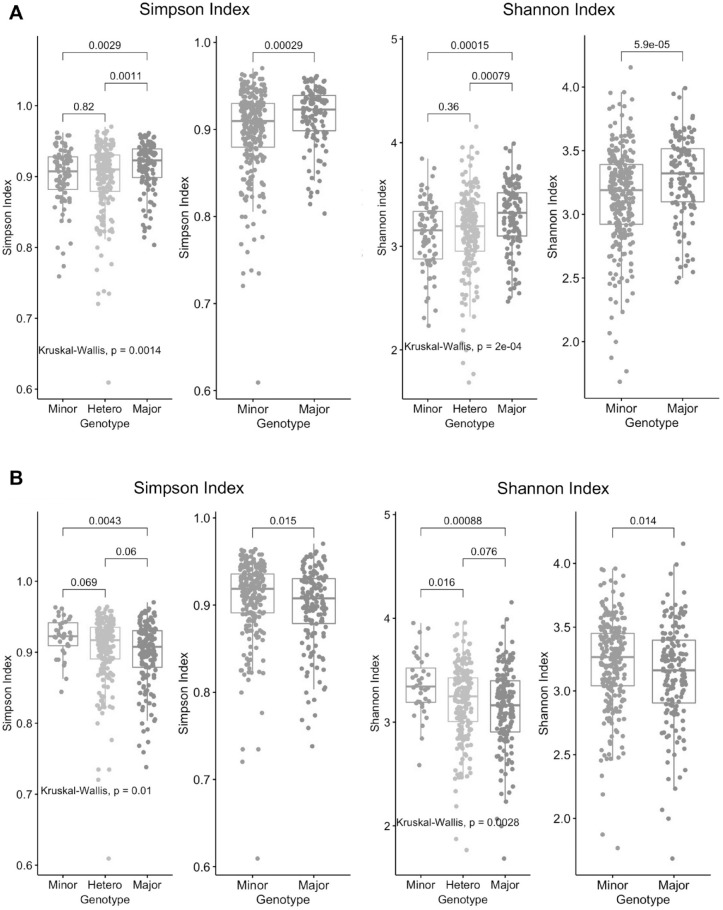

In salivary microbiota, the only investigated SNP that showed significant associations with α diversity at P < 0.002 in a multivariate model (N = 322) was IL10 rs6667202; both Simpson and Shannon indices in the common genotype were significantly higher in the dominant model (Shannon: P = 0.00039; Simpson: P = 0.0016). Dominant model for the VDR rs2228570 showed a borderline association with lower diversity (Shannon: P = 0.0087; Simpson: P = 0.049) in a multivariate model. The distributions of α diversity for the above SNPs are shown in Figure 1. The β diversity was also different between common and rare genotypes for IL10 rs6667202 (P = 0.002) and for the other SNPs: HSA21 rs243588 (P = 0.005), Fc-γR rs9287989 (P = 0.013), IL10 rs1800896 (P = 0.015), and UHRF2 rs16924631 (P = 0.028) (Fig. 2). Self-reported periodontal status showed no associations with α diversity (Shannon: P = 0.16; Simpson: P = 0.48; not shown in figures), but it did with β diversity (P = 0.001) (Appendix Fig. 2A).

Figure 1.

The distribution of Simpson/Shannon salivary α diversity by genotypes in (A) IL10_rs666702 and (B) VDR_rs2228570. All the above showed statistical difference between genotypes (divided into minor or homozygous for rare allele, heterozygous and major or homozygous for common allele) with either a Kruskal-Wallis test or Student’s t test (N = 396).

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis plots on the first 2 components with Aitchison distances in salivary microbiota. Samples highlighted with red are minor genotype and with green are major genotype.

In the gut microbiota, some significant associations were detected between SNPs (FBX038 rs10043775, Fc-γR rs1801274, ANRIL rs10760187, IL10 rs6667202) and α diversity (Appendix Fig. 3) in the univariate test, but all the associations were not statistically significant in the multivariate analysis. The β diversity was marginally significant for PKN2 rs12032672 (P = 0.044) and NCR2 rs7762544 (P = 0.045) (Appendix Fig. 2B).

No associations were detected for either microbial α diversity (Shannon: P = 0.22; Simpson: P = 0.49; not shown in figures) or β diversity (PERMANOVA, P = 0.38; not shown in figures) by self-reported periodontal status in the subset of 1,031 participants.

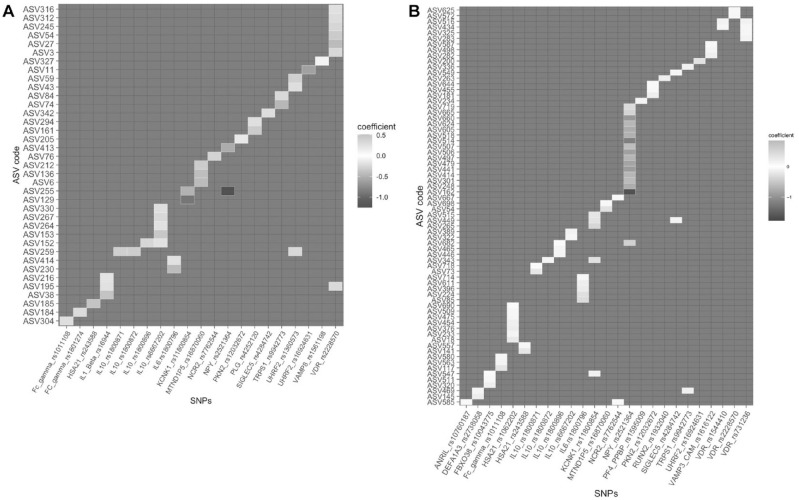

Association between SNPs and ASVs

In saliva samples, multivariate statistical models resulted in 42 significant associations with 21 SNPs (P = 0.001; Fig. 3A, Table 2), of which the greatest number of associations were detected for VDR rs2228570, followed by IL10 rs6667202. The major genotype (homozygosity of common allele) in VDR rs2228570 was negatively associated with 3 ASVs in Prevotella sp. (ASV316, ASV245, and ASV3), ASV312 (Rikenellaceae), ASV54 (Campylobacter sp.), and ASV27 (Fusobacterium nucleatum). The major genotype in IL10 rs6667202 was positively associated with ASV330 (Alloprevotella sp.), ASV267 (Capnocytophaga sp.), ASV264 (Leptotrichia sp.), ASV153 (Absconditabacteriales [SR1]), and ASV152 (Cardiobacterium hominis). ASV255 (Eikenella), ASV152 (Cardiobacterium hominis), ASV259 (Actinomyces sp.), and ASV195 (Fretibacterium fastidiosum) presented significant associations with multiple SNPs.

Figure 3.

Heatmap depicting associations between amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) in (A) saliva and (B) gut and genotypes (used dominant model) with multivariate analysis. Higher color concentration represents stronger associations; positive correlations are shown in red, and negative correlations are shown in blue. The taxonomic information for all the ASVs in the y-axis is listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Taxonomic Information Corresponding to ASVs Shown in Figure 3.

| ASV Code | Phylum | Class | Order | Family | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomy corresponding to the salivary ASVs shown in Figure 3A | ||||||

| ASV316 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Prevotellaceae | Prevotella_2 | marshii |

| ASV312 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Rikenellaceae | Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group | NA |

| ASV245 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Prevotellaceae | Prevotella_2 | NA |

| ASV54 | Epsilonbacteraeota | Campylobacteria | Campylobacterales | Campylobacteraceae | Campylobacter | rectus/showae |

| ASV27 | Fusobacteria | Fusobacteriia | Fusobacteriales | Fusobacteriaceae | Fusobacterium | nucleatum |

| ASV3 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Prevotellaceae | Prevotella_7 | melaninogenica |

| ASV327 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Flavobacteriales | Weeksellaceae | Bergeyella | NA |

| ASV11 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria | Pasteurellales | Pasteurellaceae | Aggregatibacter | segnis |

| ASV59 | Patescibacteria | Gracilibacteria | Absconditabacteriales_(SR1) | NA | NA | NA |

| ASV43 | Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria | Micrococcales | Micrococcaceae | Rothia | dentocariosa |

| ASV84 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | Lachnoanaerobaculum | cf. |

| ASV74 | Fusobacteria | Fusobacteriia | Fusobacteriales | Leptotrichiaceae | Leptotrichia | NA |

| ASV342 | Firmicutes | Bacilli | Lactobacillales | Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus | NA |

| ASV294 | Spirochaetes | Spirochaetia | Spirochaetales | Spirochaetaceae | Treponema_2 | NA |

| ASV161 | Tenericutes | Mollicutes | Mollicutes_RF39 | NA | NA | NA |

| ASV205 | Fusobacteria | Fusobacteriia | Fusobacteriales | Leptotrichiaceae | Leptotrichia | NA |

| ASV413 | Firmicutes | Negativicutes | Selenomonadales | Veillonellaceae | Dialister | NA |

| ASV76 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria | Pasteurellales | Pasteurellaceae | Mannheimia | NA |

| ASV212 | Spirochaetes | Spirochaetia | Spirochaetales | Spirochaetaceae | Treponema_2 | NA |

| ASV136 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | Oribacterium | parvum |

| ASV6 | Fusobacteria | Fusobacteriia | Fusobacteriales | Fusobacteriaceae | Fusobacterium | periodonticum |

| ASV255 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria | Betaproteobacteriales | Neisseriaceae | Eikenella | NA |

| ASV129 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Family_XI | Parvimonas | micra |

| ASV330 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Prevotellaceae | Alloprevotella | NA |

| ASV267 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Flavobacteriales | Flavobacteriaceae | Capnocytophaga | NA |

| ASV264 | Fusobacteria | Fusobacteriia | Fusobacteriales | Leptotrichiaceae | Leptotrichia | NA |

| ASV153 | Patescibacteria | Gracilibacteria | Absconditabacteriales_(SR1) | NA | NA | NA |

| ASV152 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria | Cardiobacteriales | Cardiobacteriaceae | Cardiobacterium | hominis |

| ASV259 | Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria | Actinomycetales | Actinomycetaceae | Actinomyces | johnsonii/naeslundii/oris |

| ASV414 | Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria | Actinomycetales | Actinomycetaceae | NA | NA |

| ASV230 | Firmicutes | Bacilli | Lactobacillales | Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus | anginosus/constellatus/intermedius/lutetiensis |

| ASV216 | Synergistetes | Synergistia | Synergistales | Synergistaceae | Fretibacterium | NA |

| ASV195 | Synergistetes | Synergistia | Synergistales | Synergistaceae | Fretibacterium | fastidiosum |

| ASV38 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Prevotellaceae | Prevotella | NA |

| ASV185 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria | Betaproteobacteriales | Neisseriaceae | Alysiella | NA |

| ASV184 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Flavobacteriales | Weeksellaceae | Bergeyella | NA |

| ASV304 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Rikenellaceae | Blvii28_wastewater-sludge_group | NA |

| Taxonomy corresponding to the gut ASVs shown Figure 3B | ||||||

| ASV625 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | NA | NA |

| ASV572 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Ruminiclostridium_9 | NA |

| ASV516 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | NA | NA |

| ASV434 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Ruminococcaceae_UCG-014 | NA |

| ASV325 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | NA | NA |

| ASV283 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Ruminococcaceae_UCG-014 | NA |

| ASV587 | Lentisphaerae | Lentisphaeria | Victivallales | vadinBE97 | NA | NA |

| ASV498 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Family_XIII | Family_XIII_AD3011_group | NA |

| ASV282 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Clostridiales_vadinBB60_group | NA | NA |

| ASV200 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Faecalibacterium | prausnitzii |

| ASV336 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Ruminococcus_1 | champanellensis |

| ASV549 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Clostridiaceae_1 | Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1 | disporicum |

| ASV263 | Actinobacteria | Coriobacteriia | Coriobacteriales | Coriobacteriales_Incertae_Sedis | NA | NA |

| ASV644 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Prevotellaceae | Prevotella | timonensis |

| ASV455 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Christensenellaceae | Christensenellaceae_R-7_group | NA |

| ASV181 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Bacteroidaceae | Bacteroides | finegoldii |

| ASV234 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | NA | NA |

| ASV719 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | NA | NA |

| ASV665 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Ruminococcaceae_UCG-007 | NA |

| ASV660 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | NA | NA |

| ASV624 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Christensenellaceae | NA | NA |

| ASV605 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group | NA |

| ASV518 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | Hungatella | NA |

| ASV514 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | NA | NA |

| ASV507 | Lentisphaerae | Lentisphaeria | Victivallales | Victivallaceae | Victivallis | NA |

| ASV506 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Angelakisella | NA |

| ASV497 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | Lachnoclostridium | NA |

| ASV479 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Defluviitaleaceae | Defluviitaleaceae_UCG-011 | NA |

| ASV441 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Negativibacillus | massiliensis |

| ASV414 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Intestinimonas | butyriciproducens |

| ASV301 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | NA | NA |

| ASV248 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Ruminococcaceae_UCG-010 | NA |

| ASV162 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria | Betaproteobacteriales | Burkholderiaceae | Sutterella | wadsworthensis |

| ASV667 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | NA | NA |

| ASV698 | Firmicutes | Bacilli | Lactobacillales | Carnobacteriaceae | Granulicatella | NA |

| ASV54 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Bacteroidaceae | Bacteroides | eggerthii |

| ASV515 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Peptococcaceae | NA | NA |

| ASV449 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | Tyzzerella_3 | NA |

| ASV265 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | NA | NA |

| ASV389 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Marinifilaceae | Butyricimonas | virosa |

| ASV322 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Ruminococcaceae_UCG-014 | NA |

| ASV682 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Clostridiales_vadinBB60_group | NA | NA |

| ASV465 | Firmicutes | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| ASV446 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Hydrogenoanaerobacterium | NA |

| ASV343 | Firmicutes | Bacilli | Lactobacillales | Enterococcaceae | Enterococcus | NA |

| ASV718 | Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria | Actinomycetales | Actinomycetaceae | Actinomyces | odontolyticus |

| ASV73 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Barnesiellaceae | Barnesiella | intestinihominis |

| ASV714 | Firmicutes | Erysipelotrichia | Erysipelotrichales | Erysipelotrichaceae | Dielma | NA |

| ASV611 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | NA | NA |

| ASV396 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | NA | NA |

| ASV224 | Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria | Bifidobacteriales | Bifidobacteriaceae | Bifidobacterium | animalis |

| ASV85 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Barnesiellaceae | Barnesiella | NA |

| ASV690 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Defluviitaleaceae | Defluviitaleaceae_UCG-011 | NA |

| ASV509 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Ruminococcaceae_UCG-005 | NA |

| ASV475 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | NA | NA |

| ASV454 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | NA | NA |

| ASV376 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Ruminiclostridium_9 | NA |

| ASV233 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | Blautia | caecimuris |

| ASV18 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Faecalibacterium | prausnitzii |

| ASV557 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | Lachnoclostridium | NA |

| ASV141 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Ruminococcaceae_UCG-002 | NA |

| ASV580 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Angelakisella | NA |

| ASV563 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | DTU089 | NA |

| ASV117 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Bacteroidaceae | Bacteroides | ovatus |

| ASV547 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Clostridiales_vadinBB60_group | NA | NA |

| ASV511 | Firmicutes | Negativicutes | Selenomonadales | Veillonellaceae | Veillonella | NA |

| ASV320 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Ruminococcaceae_UCG-010 | NA |

| ASV469 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Ruminococcaceae_UCG-005 | NA |

| ASV145 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Faecalibacterium | prausnitzii |

| ASV585 | Actinobacteria | Coriobacteriia | Coriobacteriales | Atopobiaceae | Olsenella | NA |

| ASV162 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria | Betaproteobacteriales | Burkholderiaceae | Sutterella | wadsworthensis |

| ASV667 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | NA | NA |

| ASV698 | Firmicutes | Bacilli | Lactobacillales | Carnobacteriaceae | Granulicatella | NA |

| ASV54 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Bacteroidaceae | Bacteroides | eggerthii |

| ASV515 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Peptococcaceae | NA | NA |

| ASV449 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Lachnospiraceae | Tyzzerella_3 | NA |

| ASV265 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | NA | NA |

| ASV389 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia | Bacteroidales | Marinifilaceae | Butyricimonas | virosa |

| ASV322 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Clostridiales | Ruminococcaceae | Ruminococcaceae_UCG-014 | NA |

ASV, amplicon sequence variant; NA, Not Applicable.

Figure 3B and Table 2 show the list of SNPs exhibiting significant association with gut ASVs (using a dominant allele model in multivariate regression models with P < 0.002). NPY rs2521364 accounted for the greatest number of associations with ASVs. The positive association with NPY rs2521364 major genotype was seen only with ASV 301 (Ruminococcaceae); the other 15 ASVs were negatively associated with the major genotype in NPY rs2521364. There were 6 ASVs significantly associated with more than 1 SNP. ASV526 (Lachnospiraceae) and ASV434 (Ruminococcaceae) were both associated with SNPs in VDR. ASV449 (Tyzzerella sp.), ASV682 (Clostridiales_vadinBB60_group), ASV343 (Enterococcus sp.), and ASV547 (Clostridiales_vadinBB60_group) were also mutually found across different SNPs.

Associations between Periodontal Disease and ASVs

In saliva samples, multivariate analysis using a generalized linear mixed model showed 70 ASVs increased and 7 decreased in patients with self-reported periodontal disease (Appendix Fig. 4A).

In gut samples, multivariate analysis using a generalized linear mixed model showed 39 ASVs associated with self-reported periodontal disease (P < 0.05), of which 9 were decreased in self-reported periodontal disease (Appendix Fig. 4B).

Association of Gut and Salivary Microbiota Dissimilarity with Self-Reported Periodontal Status

The combined microbial data from saliva and stool samples initially contained 30,732 ASVs. Removing ASVs with a prevalence below 7.5% resulted in 656 ASVs in total (481 ASVs from gut samples, 67 ASVs from saliva samples, and 108 in both). The taxa data for the shared ASVs are presented in Appendix Table 4. Logistic regression analysis adjusted for age and time difference of saliva and stool sample collection showed that the difference in Euclidean distance matrix between saliva and gut microbiota was significantly greater in self-reported periodontal cases compared to periodontal health (P = 0.03). Other confounding factors did not present significant association in the model.

Discussion

This study investigated associations between host genetic variants and both salivary and gut microbiota. Among the 25 studied genes containing putative host genetic variants relevant for periodontal disease, IL10 emerged as the most consistent. SNPs in the IL10 gene were associated with salivary microbiota α and β diversity and the greatest number of ASVs with gut microbiota α diversity.

The IL10 promoter region is highly polymorphic, and 3 SNPs at positions −1082 (rs1800896), −819 (rs1800871), and −592 (rs1800872) have been reported to be correlated with altered IL-10 production in vitro (Turner et al. 1997; Reuss et al. 2002). An analysis of SNPs in the promoter region of IL10 revealed an association with increased susceptibility to periodontitis (Berglundh et al. 2003) while a lack of association has also been reported (Chambrone et al. 2014). A systematic review including both candidate gene studies and GWAS identified the IL10 gene, along with VDR and Fc-γR genes, as those with the highest level of evidence for an association with periodontitis, based on specific predefined criteria (Nibali et al. 2017). The findings of the present study suggest that IL10 host genetic variants may influence the salivary microbiota. These associations were particularly consistent for IL10 rs6667202. As well as with microbial diversity, this SNP was associated with ASV330 (Alloprevotella sp.) and ASV267 (Capnocytophaga sp.), which were reported to have a link to periodontal disease. All 5 ASVs in relation to IL10 rs6667202 were Gram negative and anaerobic. Interestingly, a similar trend for increased diversity for common homozygosity for this SNP was detected for both salivary and gut microbiota, although the association was stronger for salivary microbiota. This agrees with a potential effect of IL10 SNPs on the subgingival microbiota (Reichert et al. 2008; Luo et al. 2013). The influence of IL10 genotypes on the salivary microbiota may be mediated by an effect on IL-10 production and on the inflammatory cascade, which may in turn favor the growth of pathogenic microbes as well as Gram-negative, anaerobic bacteria leading to microbial dysbiosis (Nibali et al. 2014), which in turn promotes more inflammation. If and how this “infectogenomics” influence can affect the “Inflammation-Mediated Polymicrobial-Emergence and Dysbiotic-Exacerbation” (IMPEDE) model (Van Dyke et al. 2020) remains to be clarified. This model suggests that inflammation is the main driver of periodontitis, which in turn facilitates colonization by proinflammatory microbes.

Among the other host gene variants investigated, another prominent association with microbial outcomes was found for SNPs in the VDR gene. For VDR rs2228570, the α diversity for the rare allele was significantly higher than for the dominant allele, and an association was detected with lower abundance of 7 ASVs, including 3 ASVs (ASV316, ASV245, and ASV3) in the genus Prevotella and ASV27 (Fusobacterium nucleatum), which are recognized periodontopathogenic bacteria. The biological mechanisms linking VDR polymorphisms and susceptibility to periodontitis may be modulated by effects on the immune system and bone metabolism, possibly resulting in a dysbiotic effect.

In general, the SNPs in this study (which were selected for a suspected role in periodontal pathogenesis) appeared to exert a more profound effect on the salivary microbiota than that of the gut, suggesting that their effect may be more restricted to the oral cavity. An interesting finding was the association between gene variants in NPY rs2521364 and gut ASVs; there were 16 ASVs showing significant associations, 7 of which (ASV719, ASV665, ASV506, ASV441, ASV414, ASV301, ASV248) are assigned to Ruminococcaceae and 5 ASVs (ASV660, ASV605, ASV518, ASV514, ASV497) are corresponding to Lachnospiraceae. NPY gene has a function of regulating the secretion of neuropeptides and cortisol. Those substances inhibit secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and potentially maintain periodontal health (Lundy et al. 2009). The effect on gut ASVs may be mediated by effects on the central nervous system through the activity of neuropeptides as endocrine messengers in the microbial-gut-brain axis (Holzer and Farzi 2014).

Salivary microbiome structure in the abundance of species such as Prevotella intermedia, Tannerella forsythia, and Fusobacterium nucleatum as well as β-diversity was significantly associated with self-reported periodontal status. The gut microbiome did not express strong associations with either self-reported periodontal status or periodontitis-related genetic variants (only borderline associations were identified with the examined SNPs). This suggests that the gut microbiota is less influenced by periodontitis than the salivary microbiota. Although the salivary microbiome only partially reflects changes in the subgingival environment, it has been shown that periodontopathogenic bacteria such as Tannerella forsythia and Filifactor alocis are increased in the saliva of patients with periodontitis versus healthy individuals (Lundmark et al. 2019; Sabharwal et al. 2019). The combined microbial data of gut and saliva showed significantly greater dissimilarity in periodontal cases. These data indicate that the individual difference in the composition of microbial communities between gut and saliva is greater in periodontal cases than in periodontal health. Given this, the presence of periodontitis (albeit self-reported) in these cohorts may be reflected in shifts in the salivary microbiota.

One of the limitations of this study is the use of self-reported data to assess periodontal disease status. The specificity and sensitivity of the definition used in this study were previously investigated in a subset of TwinsUK cohort and found to be 71% and 49%, respectively (unpublished data). The low sensitivity is likely to underestimate the presence of disease compared to the clinically measured parameters. However, a recent study (Deng et al. 2021) found that a questionnaire related to loose teeth may be the most appropriate for identifying the periodontal disease, including both periodontitis and gingivitis. Furthermore, the outcome “periodontal disease,” albeit important, was not the main outcome of this study. Another limitation is that history of systemic diseases was not included in the analyses. The analyses were not adjusted for smoking status, diet, and other systemic health conditions due to missing data and in order to avoid overadjusting in multivariate models. Another limitation is that some SNPs were not in HWE, and it is difficult to speculate about reasons for this. However, this was not the case for IL10 SNPs.

The strengths of this study lie in the novelty of assessing the effects of host genetic variants on both salivary and gut microbiota in a large cohort of twins and of taking self-reported periodontal conditions into consideration when assessing these associations. Overall, this study produced considerable evidence pointing toward IL10 and VDR gene variants in the hunt for host genetic variants that influence salivary dysbiosis and confirmed that periodontal disease may drive variations in the salivary microbiota. Examination of the data reported here also sheds light into the intriguing associations between the salivary and gut microbiota in relation to periodontal disease.

Author Contributions

Y. Kurushima, contributed to conception and design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafted the manuscript; P.M. Wells, R.C.E. Bowyer, S. Doran, contributed to conception and design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; N. Zoheir, contributed to data conception, drafted the manuscript; J.P. Richardson, contributed to conception, data interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; D.D. Sprockett, D. Relman, contributed to conception, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; C.J. Steves, contributed to conception, data interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; L. Nibali, contributed to conception, data interpretation, drafted the manuscript. All authors gave their final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jdr-10.1177_00220345221125402 for Host Genotype Links to Salivary and Gut Microbiota by Periodontal Status by Y. Kurushima, P.M. Wells, R.C.E. Bowyer, N. Zoheir, S. Doran, J.P. Richardson, D.D. Sprockett, D.A. Relman, C.J. Steves and L. Nibali in Journal of Dental Research

Footnotes

A supplemental appendix to this article is available online.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: TwinsUK is funded by the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council, European Union, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)–funded BioResource, Clinical Research Facility, and Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’s NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King’s College London. This research was supported by the National Science Foundation NSF GRF DGE-114747 (D.D. Sprockett), National Institute of Health grants NIH/NIGMS T32GM007276 (D.D. Sprockett), the Thomas C. and Joan M. Merigan Endowment at Stanford University (D. Relman), and the Chan Zuckerburg Biohub Microbiome Initiative (D. Relman).

ORCID iDs: David Relman  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8331-1354

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8331-1354

Luigi Nibali  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7750-5010

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7750-5010

References

- Belstrom D, Grande MA, Sembler-Moller ML, Kirkby N, Cotton SL, Paster BJ, Holmstrup P. 2018. Influence of periodontal treatment on subgingival and salivary microbiotas. J Periodontol. 89(5):531–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglundh T, Donati M, Hahn-Zoric M, Hanson LA, Padyukov L. 2003. Association of the –1087 IL 10 gene polymorphism with severe chronic periodontitis in Swedish Caucasians. J Clin Periodontol. 30(3):249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulange CL, Neves AL, Chilloux J, Nicholson JK, Dumas ME. 2016. Impact of the gut microbiota on inflammation, obesity, and metabolic disease. Genome Med. 8(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, et al. 2010. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 7(5):335–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalla F, Biguetti CC, Melchiades JL, Tabanez AP, Azevedo MCS, Trombone APF, Faveri M, Feres M, Garlet GP. 2018. Genetic association with subgingival bacterial colonization in chronic periodontitis. Genes (Basel). 9(6):271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambrone L, Ascarza A, Guerrero ME, Pannuti C, de la Rosa M, Salinas-Prieto E, Mendoza G. 2014. Association of –1082 interleukin-10 genepolymorphism in Peruvian adults with chronic periodontitis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 19(6):e569–e573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven M, Egan CE, Dowd SE, McDonough SP, Dogan B, Denkers EY, Bowman D, Scherl EJ, Simpson KW. 2012. Inflammation drives dysbiosis and bacterial invasion in murine models of ileal crohn’s disease. PLoS One. 7(7):e41594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MA, Diaz PI, Van Dyke TE. 2020. The role of the microbiota in periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 83(1):14–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng K, Pelekos G, Jin L, Tonetti MS. 2021. Diagnostic accuracy of self-reported measures of periodontal disease: a clinical validation study using the 2017 case definitions. J Clin Periodontol. 48(8):1037–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divaris K, Monda KL, North KE, Olshan AF, Lange EM, Moss K, Barros SP, Beck JD, Offenbacher S. 2012. Genome-wide association study of periodontal pathogen colonization. J Dent Res. 91(7 Suppl):21S–28S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divaris K, Monda KL, North KE, Olshan AF, Reynolds LM, Hsueh WC, Lange EM, Moss K, Barros SP, Weyant RJ, et al. 2013. Exploring the genetic basis of chronic periodontitis: a genome-wide association study. Hum Mol Genet. 22(11):2312–2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich JK, Davenport ER, Beaumont M, Jackson MA, Knight R, Ober C, Spector TD, Bell JT, Clark AG, Ley RE. 2016. Genetic determinants of the gut microbiome in UK twins. Cell Host Microbe. 19(5):731–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich JK, Waters JL, Poole AC, Sutter JL, Koren O, Blekhman R, Beaumont M, Van Treuren W, Knight R, Bell JT, et al. 2014. Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell. 159(4):789–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. 2012. Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Mol Oral Microbiol. 27(6):409–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer P, Farzi A. 2014. Neuropeptides and the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 817:195–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam P, Weiss RA. 2006. Infectogenomics: insights from the host genome into infectious diseases. Cell. 124(4):695–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurilshikov A, Medina-Gomez C, Bacigalupe R, Radjabzadeh D, Wang J, Demirkan A, Le Roy CI, Raygoza Garay JA, Finnicum CT, Liu X, et al. 2021. Large-scale association analyses identify host factors influencing human gut microbiome composition. Nat Genet. 53(2):156–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourenvarsigmao TGB, Spencer SJ, Alm EJ, Colombo APV. 2018. Defining the gut microbiota in individuals with periodontal diseases: an exploratory study. J Oral Microbiol. 10(1):1487741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundmark A, Hu YOO, Huss M, Johannsen G, Andersson AF, Yucel-Lindberg T. 2019. Identification of salivary microbiota and its association with host inflammatory mediators in periodontitis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 9:216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundy FT, El Karim IA, Linden GJ. 2009. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) and NPY Y1 receptor in periodontal health and disease. Arch Oral Biol. 54(3):258–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Gong Y, Yu Y. 2013. Interleukin-10 gene promoter polymorphisms are associated with cyclosporin A–induced gingival overgrowth in renal transplant patients. Arch Oral Biol. 58(9):1199–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munz M, Willenborg C, Richter GM, Jockel-Schneider Y, Graetz C, Staufenbiel I, Wellmann J, Berger K, Krone B, Hoffmann P, et al. 2017. A genome-wide association study identifies nucleotide variants at SIGLEC5 and DEFA1A3 as risk loci for periodontitis. Hum Mol Genet. 26(13):2577–2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munz M, Willenborg C, Richter GM, Jockel-Schneider Y, Graetz C, Staufenbiel I, Wellmann J, Berger K, Krone B, Hoffmann P, et al. 2018. A genome-wide association study identifies nucleotide variants at SIGLEC5 and DEFA1A3 as risk loci for periodontitis. Hum Mol Genet. 27(5):941–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibali L, Di Iorio A, Onabolu O, Lin GH. 2016. Periodontal infectogenomics: systematic review of associations between host genetic variants and subgingival microbial detection. J Clin Periodontol. 43(11):889–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibali L, Di Iorio A, Tu YK, Vieira AR. 2017. Host genetics role in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease and caries. J Clin Periodontol. 44(Suppl 18):S52–S78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibali L, Henderson B, Sadiq ST, Donos N. 2014. Genetic dysbiosis: the role of microbial insults in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Oral Microbiol. 6:1–10. doi: 10.3402/jom.v6.22962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibali L, Ready DR, Parkar M, Brett PM, Wilson M, Tonetti MS, Griffiths GS. 2007. Gene polymorphisms and the prevalence of key periodontal pathogens. J Dent Res. 86(5):416–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen I, Yamazaki K. 2019. Can oral bacteria affect the microbiome of the gut? J Oral Microbiol. 11(1):1586422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert S, Machulla HK, Klapproth J, Zimmermann U, Reichert Y, Glaser CH, Schaller HG, Stein J, Schulz S. 2008. The interleukin-10 promoter haplotype ata is a putative risk factor for aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 43(1):40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuss E, Fimmers R, Kruger A, Becker C, Rittner C, Hohler T. 2002. Differential regulation of interleukin-10 production by genetic and environmental factors—a twin study. Genes Immun. 3(7):407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodin K, Divaris K, North KE, Barros SP, Moss K, Beck JD, Offenbacher S. 2014. Chronic periodontitis genome-wide association studies: gene-centric and gene set enrichment analyses. J Dent Res. 93(9):882–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabharwal A, Ganley K, Miecznikowski JC, Haase EM, Barnes V, Scannapieco FA. 2019. The salivary microbiome of diabetic and non-diabetic adults with periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 90(1):26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer AS, Jochens A, Dommisch H, Graetz C, Jockel-Schneider Y, Harks I, Staufenbiel I, Meyle J, Eickholz P, Folwaczny M, et al. 2014. A large candidate-gene association study suggests genetic variants at IRF5 and PRDM1 to be associated with aggressive periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 41(12):1122–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shusterman A, Durrant C, Mott R, Polak D, Schaefer A, Weiss EI, Iraqi FA, Houri-Haddad Y. 2013. Host susceptibility to periodontitis: mapping murine genomic regions. J Dent Res. 92(5):438–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shusterman A, Munz M, Richter G, Jepsen S, Lieb W, Krone B, Hoffman P, Laudes M, Wellmann J, Berger K, et al. 2017. The PF4/PPBP/CXCL5 gene cluster is associated with periodontitis. J Dent Res. 96(8):945–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Smith C, Duff GW. 2000. Microbiological parameters associated with IL-1 gene polymorphisms in periodontitis patients.J Clin Periodontol. 27(11):810–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, Sogin ML, Jones WJ, Roe BA, Affourtit JP, et al. 2009. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 457(7228):480–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner DM, Williams DM, Sankaran D, Lazarus M, Sinnott PJ, Hutchinson IV. 1997. An investigation of polymorphism in the interleukin-10 gene promoter. Eur J Immunogenet. 24(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke TE, Bartold PM, Reynolds EC. 2020. The nexus between periodontal inflammation and dysbiosis. Front Immunol. 11:511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdi S, Abbasian G, Bowyer RCE, Lachance G, Yarand D, Christofidou P, Mangino M, Menni C, Bell JT, Falchi M, et al. 2019. TwinsUK: The UK adult twin registry update. Twin Res Hum Genet. 22(6):523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jdr-10.1177_00220345221125402 for Host Genotype Links to Salivary and Gut Microbiota by Periodontal Status by Y. Kurushima, P.M. Wells, R.C.E. Bowyer, N. Zoheir, S. Doran, J.P. Richardson, D.D. Sprockett, D.A. Relman, C.J. Steves and L. Nibali in Journal of Dental Research