Abstract

Legionella pneumophila replicates in macrophages and amoeba within a unique compartment, the Legionella‐containing vacuole (LCV). Hallmarks of LCV formation are the phosphoinositide lipid conversion from PtdIns(3)P to PtdIns(4)P, fusion with ER‐derived vesicles and a tight association with the ER. Proteomics of purified LCVs indicate the presence of membrane contact sites (MCS) proteins possibly implicated in lipid exchange. Using dually fluorescence‐labeled Dictyostelium discoideum amoeba, we reveal that VAMP‐associated protein (Vap) and the PtdIns(4)P 4‐phosphatase Sac1 localize to the ER, and Vap also localizes to the LCV membrane. Furthermore, Vap as well as Sac1 promote intracellular replication of L. pneumophila and LCV remodeling. Oxysterol binding proteins (OSBPs) preferentially localize to the ER (OSBP8) or the LCV membrane (OSBP11), respectively, and restrict (OSBP8) or promote (OSBP11) bacterial replication and LCV expansion. The sterol probes GFP‐D4H* and filipin indicate that sterols are rapidly depleted from LCVs, while PtdIns(4)P accumulates. In addition to Sac1, the PtdIns(4)P‐subverting L. pneumophila effector proteins LepB and SidC also support LCV remodeling. Taken together, the Legionella‐ and host cell‐driven PtdIns(4)P gradient at LCV‐ER MCSs promotes Vap‐, OSBP‐ and Sac1‐dependent pathogen vacuole maturation.

Keywords: Atlastin, Dictyostelium discoideum, Legionnaires' disease, oxysterol binding protein, Sac1 phosphoinositide phosphatase

Subject Categories: Membranes & Trafficking; Microbiology, Virology & Host Pathogen Interaction; Organelles

Legionella pneumophila replicates intracellularly within a unique “Legionella‐containing vacuole” (LCV). Dually fluorescence‐labeled Dictyostelium discoideum amoeba reveal that LCVs and the ER form membrane contact sites and Legionella‐ as well as host cell‐driven lipid flux promotes pathogen vacuole remodeling.

Introduction

Legionella pneumophila is an amoeba‐resistant environmental bacterium, which causes a severe pneumonia called Legionnaires' disease (Newton et al, 2010; Mondino et al, 2020). The facultative intracellular pathogen employs a conserved mechanism to grow in free‐living protozoa as well as in alveolar macrophages, which is a prerequisite to cause disease (Hoffmann et al, 2014b; Boamah et al, 2017; Swart et al, 2018; Hilbi & Buchrieser, 2022). To govern the interaction with host cells, L. pneumophila employs the Icm/Dot (Intracellular multiplication/defective organelle trafficking) type IV secretion system (T4SS), which translocates ca. 330 different “effector” proteins into host cells (Qiu & Luo, 2017; Hilbi & Buchrieser, 2022). These effector proteins subvert pivotal host cell processes, including the endocytic, secretory, retrograde and autophagy pathways, lipid metabolism, transcription, translation, and apoptosis (Finsel & Hilbi, 2015; Escoll et al, 2016; Personnic et al, 2016; Bärlocher et al, 2017; Swart et al, 2020).

Within host cells, L. pneumophila forms a unique, membrane‐bound replication compartment, the Legionella‐containing vacuole (LCV), which restricts interactions with the endocytic pathway (Asrat et al, 2014; Sherwood & Roy, 2016; Steiner et al, 2018; Swart & Hilbi, 2020). Hallmarks of LCV formation are the phosphoinositide (PI) lipid conversion from phosphatidylinositol 3‐phosphate (PtdIns(3)P) to PtdIns(4)P, the subversion of the small GTPase Rab1, fusion of the pathogen vacuole with endoplasmic reticulum (ER)‐derived vesicles, and finally, a tight association with the ER (Asrat et al, 2014; Sherwood & Roy, 2016; Steiner et al, 2018; Swart & Hilbi, 2020). In the first 1–2 h after bacterial uptake, the LCV accumulates PtdIns(4)P (Weber et al, 2006), and PtdIns(3)P‐positive endosomal membranes condense to the cell center (Weber et al, 2014). Live‐cell fluorescence microscopy at high temporal and spatial resolution revealed that LCVs gradually lose the endosomal PI PtdIns(3)P within 2 h, while the secretory PI PtdIns(4)P steadily accumulates during this period of time and remains spatially separated from calnexin‐positive ER for at least 8 h (Weber et al, 2014).

The production of PtdIns(4)P on the LCV membrane implicates the sequential activity of L. pneumophila Icm/Dot‐secreted effector proteins: the PtdIns 3‐kinase MavQ (Li et al, 2021), PtdIns(3)P 4‐kinase LepB (Dong et al, 2016) and PtdIns(3,4)P 2 3‐phosphatase SidF (Hsu et al, 2012). Moreover, host PI‐modulating enzymes such as the PtdIns 4‐kinases PI4KIIIα (Hubber et al, 2014) and PI4KIIIβ (Brombacher et al, 2009), as well as the PtdIns(4,5)P 5‐phosphatase OCRL1 (Weber et al, 2009; Choi et al, 2021), might also play a role in the production of PtdIns(4)P on the LCV membrane.

The small GTPase Rab1 is enriched in the cis‐Golgi apparatus and controls ER‐Golgi secretory trafficking (Sherwood & Roy, 2016). Rab1 is recruited to the LCV membrane and activated by the Icm/Dot secreted effector SidM (alias DrrA), which binds to PtdIns(4)P through the novel P4M domain (Brombacher et al, 2009; Schoebel et al, 2010; Del Campo et al, 2014; Hammond et al, 2014; Hubber et al, 2014) and possess Rab1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF)/guanine dissociation inhibitor (GDI) displacement factor (GDF) activity (Machner & Isberg, 2006, 2007; Murata et al, 2006; Ingmundson et al, 2007; Suh et al, 2010; Zhu et al, 2010; Oesterlin et al, 2012) as well as adenosine monophosphorylation (AMPylation) activity (Müller et al, 2010; Hardiman & Roy, 2014). Moreover, Rab1 is de‐AMPylated by the effector SidD (Neunuebel et al, 2011; Tan & Luo, 2011) and reversibly phosphocholinated by the effectors AnkX and Lem3 (Mukherjee et al, 2011; Tan et al, 2011; Campanacci et al, 2013). The covalent modifications of GTP‐bound Rab1 lock the small GTPase in its active state. Finally, Rab1 is inactivated by the GTPase activating protein (GAP) LepB (Ingmundson et al, 2007). The small GTPase ARF1 controls retrograde Golgi‐ER trafficking (Sherwood & Roy, 2016). ARF1 is recruited to and activated on the LCV by the effector RalF, the first L. pneumophila GEF identified (Nagai et al, 2002).

The LCV intercepts trafficking at ER exit sites between the ER and the Golgi apparatus, and inhibition of ER‐Golgi transport blocks the formation of the pathogen vacuole (Kagan & Roy, 2002; Nagai et al, 2002; Robinson & Roy, 2006). Sec22b, a SNARE (soluble N‐ethylmaleimide‐sensitive factor (NSF) attachment protein (SNAP) receptor), which promotes fusion of ER‐derived vesicles with the cis‐Golgi, is recruited to LCVs shortly after infection (Derre & Isberg, 2004; Kagan et al, 2004). The activation of Rab1 by SidM on the LCV mediates the fusion of ER‐derived vesicles with the pathogen vacuole through the non‐canonical pairing of the vesicle (v‐)SNARE Sec22b on the vesicles with plasma membrane (PM)‐derived target (t‐)SNAREs such as syntaxin (Stx) 2, 3, 4 and SNAP23 on the LCV (Arasaki & Roy, 2010; Arasaki et al, 2012). The LCV intercepts anterograde as well as retrograde trafficking between the ER and the Golgi apparatus (Asrat et al, 2014; Escoll et al, 2016; Sherwood & Roy, 2016; Bärlocher et al, 2017). Accordingly, nascent LCVs continuously capture and accumulate PtdIns(4)P‐positive vesicles from the Golgi apparatus, and their sustained association requires a functional T4SS (Weber et al, 2018). LCVs also sequentially recruit the small GTPases Rab33b, Rab6a and the ER‐resident SNARE syntaxin18 (Stx18), which are implicated in Golgi‐ER retrograde trafficking, to promote the association of the pathogen vacuole with the ER (Kawabata et al, 2021).

The association of the LCV with ER in macrophages and amoeba has been initially documented more than 25 years ago (Swanson & Isberg, 1995; Abu Kwaik, 1996). The vacuole containing L. pneumophila associates with rough ER within minutes after uptake, and dependent on the Icm/Dot T4SS, the vacuole and the ER form extended contact sites (> 0.5 μm in length), which are connected by tiny, periodic “hair‐like” structures (Tilney et al, 2001). Remarkably, the ER elements remain attached to LCVs even after cell homogenization (Tilney et al, 2001), and intact LCVs purified from L. pneumophila‐infected D. discoideum co‐purify with extensive fragments of calnexin‐GFP‐positive ER (Urwyler et al, 2009; Hoffmann et al, 2014a; Schmölders et al, 2017). In dually fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum, LCVs accumulate calnexin‐positive ER within minutes, and the ER remains separate from the PtdIns(4)P‐positive pathogen vacuole for at least 8 h post infection (Ragaz et al, 2008; Weber et al, 2014). The ER tubules interacting with LCVs are decorated with reticulon 4 (Rtn4) and the large fusion GTPase atlastin/Sey1, which are implicated in the architecture and dynamics of the ER, respectively (Haenssler et al, 2015; Steiner et al, 2017). The L. pneumophila effector Ceg9 might stabilize the LCV‐ER contact sites by directly binding to the host protein Rtn4 (Haenssler et al, 2015). Finally, depletion of the PtdIns(4)P 4‐phosphatase Sac1, a crucial enzyme of ER membrane contact sites (MCS), reduces the recruitment of endogenous Rab1 to LCVs (Hubber et al, 2014). While the interaction of vesicles with LCVs has been studied in quite some molecular detail, the composition, formation, and dynamics of putative LCV‐ER MCS has not been addressed.

The MCS between two distinct cellular compartments or organelles adopt a number of functions and are of crucial importance for the non‐vesicular exchange of lipids in mammalian cells (Pemberton et al, 2020). MCS between the ER and the PM or organelles promote lipid exchange driven by a gradient of PtdIns(4)P, which is established by PtdIns 4‐kinases on the PM or organelles and maintained by the integral ER membrane protein PtdIns(4)P 4‐phosphatase Sac1 (Mesmin et al, 2013; Zewe et al, 2018). Driven by the PtdIns(4)P gradient, phosphatidylserine accumulates at the inner leaflet of the PM (Chung et al, 2015; Moser von Filseck et al, 2015) and cholesterol accumulates at the Golgi apparatus (Mesmin et al, 2013, 2017). The lipid exchange is promoted by lipid transfer proteins termed oxysterol binding proteins (OSBPs) and oxysterol‐binding protein (OSBP)‐related proteins (ORPs), several of which bind PtdIns(4)P through a PH domain and by the ER‐resident Vap (vesicle‐associated membrane protein (VAMP)‐associated protein) through a FFAT (two phenylalanines (FF) in an acidic tract) motif (Pemberton et al, 2020).

Several intracellular bacterial pathogens hijack MCS components during infection (Derre, 2017). The mechanistically best characterized process is carried out by the pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis, which forms a replication‐permissive compartment termed inclusion (Elwell et al, 2016; Derre, 2017). Intriguingly, the Chlamydia integral membrane proteins IncV and IncD tether the inclusion to the ER (Stanhope & Derre, 2018). IncV directly binds Vap on the ER through a FFAT motif (Stanhope et al, 2017), and the effector recruits the host protein kinase CK2 to the inclusion leading to the hyperphosphorylation of a FFAT motif core and serine‐rich segments immediately upstream of the noncanonical and canonical FFAT motifs, thus promoting the IncV‐Vap interaction (Ende et al, 2022). IncD indirectly makes contact to Vap through the FFAT motif‐containing host protein CERT (ceramide transfer protein; Derre et al, 2011; Elwell et al, 2011).

Given the tight association of the LCV with the ER and the accumulation of PtdIns(4)P on the limiting membrane of the pathogen vacuole, the LCV‐ER interface might actually form functionally important MCS, which promote pathogen vacuole remodeling through a PtdIns(4)P gradient. In this study, we tested the hypotheses that (i) MCS components localize to the LCV‐ER interface, (ii) MCS protein and lipid components are implicated in LCV remodeling and intracellular growth of L. pneumophila, and (iii) L. pneumophila effectors promote PtdIns(4)P‐dependent LCV remodeling. Using dually fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum amoeba, we identify Sac1 and Sey1 on the ER, but not on the LCV membrane, while OSBP8 and OSBP11 exclusively localize to the ER or the LCV membrane, and Vap localizes to both compartments, respectively. The MCS components were found to be implicated in LCV remodeling and intracellular growth of L. pneumophila, and a LCV‐to‐ER PtdIns(4)P gradient is established by bacterial effector proteins. These findings indicate that the Legionella‐ and host cell‐driven PtdIns(4)P gradient at LCV‐ER MCSs promotes Vap‐, Sac1‐ and OSBP‐dependent pathogen vacuole remodeling.

Results

D. discoideum MCS components localize to the LCV membrane or the ER

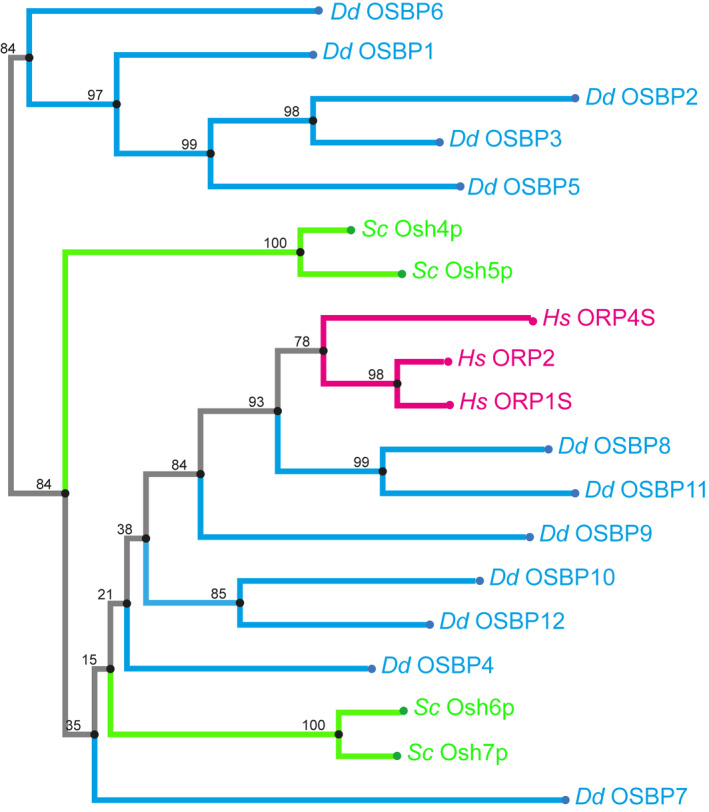

Given the tight and stable association of the LCV limiting membrane with the ER, MCS are likely formed between the compartments. To initially explore this hypothesis, we searched the D. discoideum genome for MCS components. D. discoideum harbors single putative orthologues of the PtdIns(4)P 4‐phosphatase Sac1 (DDB_G0271630; sac1), and the VAMP‐associated protein (Vap; DDB_G0278773), as well as several OSBPs, including OSBP7 (DDB_G0283035; osbG), OSBP8 (DDB_G0283709; osbH) and OSBP11 (DDB_G0288817; osbK). All 12 D. discoideum OSBPs belong to the class of “short OSBPs” (Fig EV1), which harbor a putative lipid‐binding ORD domain (OSBP‐related domain) but lack ankyrin repeats (protein–protein interaction), a PH domain (PI binding), a trans‐membrane domain (TMD; membrane interaction), and the FFAT motif (Vap interaction). OSBP8 and OSBP11 are most similar to one another and most closely related to human short ORPs. OSBP7 represents an OSBP more distantly related to the other paralogues, and OSBP1 (osbA), OSBP2 (osbB), OSBP3 (osbC), OSBP5 (osbE) and OSBP6 (osbF) form a separate cluster (Fig EV1).

Figure EV1. Phylogenetic tree of short OSBPs and ORPs from Dictyostelium discoideum, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and humans.

Sequences of all proteins were either derived from dictybase.org or uniprot and aligned with MAFFT (https://mafft.cbrc.jp) using the G‐INS‐I strategy, unalign level 0.8 and “leave gappy regions” to generate a phylogenetic tree in phylo.ilo using NJ conserved sites and the JTT substitution model. Numbers on the branches indicate bootstrap support for nodes from 100 bootstrap replicates. Hs, Homo sapiens; Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Dd, Dictyostelium discoideum.

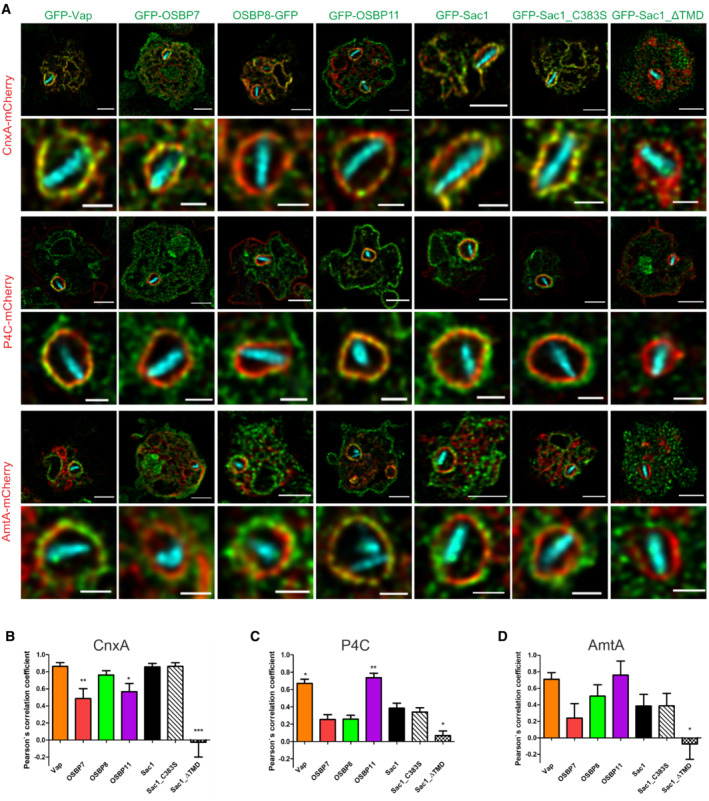

Based on these bioinformatic and cell biological considerations, we sought to analyze the role of the putative MCS components Vap, OSBP7, OSBP8, OSBP11 and Sac1 for LCV formation and the LCV‐ER MCS in detail. Using dually fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum, we assessed by confocal fluorescence microscopy the co‐localization of GFP fusions of Vap, OSBP7, OSBP8, OSBP11 or Sac1 with either the ER‐resident protein calnexin A‐mCherry (CnxA‐mCherry), the PtdIns(4)P/LCV probe P4C‐mCherry (Steiner et al, 2017), or the endosomal transporter AmtA‐mCherry (Fig 1A and Appendix Fig S1A and B). This high‐resolution approach revealed that Vap and OSBP8, but significantly less OSBP7 and OSBP11, co‐localize with CnxA‐mCherry in L. pneumophila‐infected (Fig 1B) as well as in uninfected amoebae (Appendix Fig S1C–E).

Figure 1. Dictyostelium discoideum MCS components localize to LCVs and/or ER.

-

ADually fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum amoebae producing MCS components fused to GFP, and either calnexin (CnxA)‐mCherry (pAW012), P4C‐mCherry (pWS032), or AmtA‐mCherry were infected (MOI 5, 2 h) with mCerulean‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pNP99), fixed with 4% PFA, and imaged by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Merged images are shown. Scale bars: 3 μm (insets: 1 μm).

-

B–DThe Pearson's correlation coefficients were generated using Coloc 2 from Fiji (ImageJ) and are shown for MCS components fused to GFP with respect to (B) CnxA‐mCherry (n = 146), (C) P4C‐mCherry (n = 138), or (D) AmtA‐mCherry (n = 159). Data represent mean and SEM of three independent biological replicates (statistics refer to JR32‐infected D. discoideum producing GFP‐Sac1; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test).

The PtdIns(4)P 4‐phosphatase Sac1 and its catalytically inactive mutant, Sac1_C383S, also co‐localized with CnxA‐mCherry, while a Sac1 variant lacking the ER‐targeting transmembrane domain, Sac1_ΔTMD, diffusely localized throughout the cell (Fig 1B). Moreover, Vap and OSBP11 co‐localized with P4C‐mCherry, while OSBP7, OSBP8 and Sac1 did not (Fig 1C), and Vap and OSBP11 also co‐localized with AmtA‐mCherry more extensively than the other MCS components (Fig 1D). Finally, OSBP11 intensely localized to the PM. In summary, Vap, OSBP8 and Sac1 co‐localize with ER‐resident CnxA‐mCherry at the LCV‐ER interface, and Vap as well as OSBP11 co‐localize with the PtdIns(4)P probe P4C‐mCherry and the endosomal/LCV marker AmtA‐mCherry (Table 1). Hence, the LCV indeed forms MCS with the ER, and at LCV‐ER MCS Vap localizes to LCVs as well as to the ER, while OSBP8 and Sac1 preferentially localize to the ER, and OSBP11 preferentially localizes to LCVs.

Table 1.

Features of selected D. discoideum MCS components.

| MCS component | Colocalization | Localization (PI4P‐dependent) | LCV size b | Legionella growth b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calnexin (ER) | P4C (PI4P/LCV) | AmtA (PM/EE) | ||||

| Vap (Δvap) | ++ | ++ | + | + | Smaller | Reduced |

| OSBP7 (ΔosbG) | ++/− a | − | − | − | No effect | No effect |

| OSBP8 (ΔosbH) | ++ | − | − | + | Larger | Increased |

| OSBP11 (ΔosbK) | − | ++ | ++ | − | Smaller | Reduced |

| Sac1 | ++ | − | − | n.d. | No effect | No effect |

| Sac1_C383S | ++ | − | − | n.d. | No effect | No effect |

| Sac1_ΔTMD | − | − | − | n.d. | Smaller | Reduced |

EE, early endosome; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; n.d., not determined; PI4P/LCV, phosphatidylinositol 4‐phosphate/Legionella‐containing vacuole; PM, plasma membrane.

++/‐, co‐localization or no co‐localization in L. pneumophila‐infected cells.

Intracellular growth or LCV size of L. pneumophila in D. discoideum lacking vap, osbG, osbH or osbK, or producing the Sac1 variants compared with growth or LCV size in the parental strain Ax3.

Vap colocalizes with OSBP8 and OSBP11 at the LCV‐ER MCS

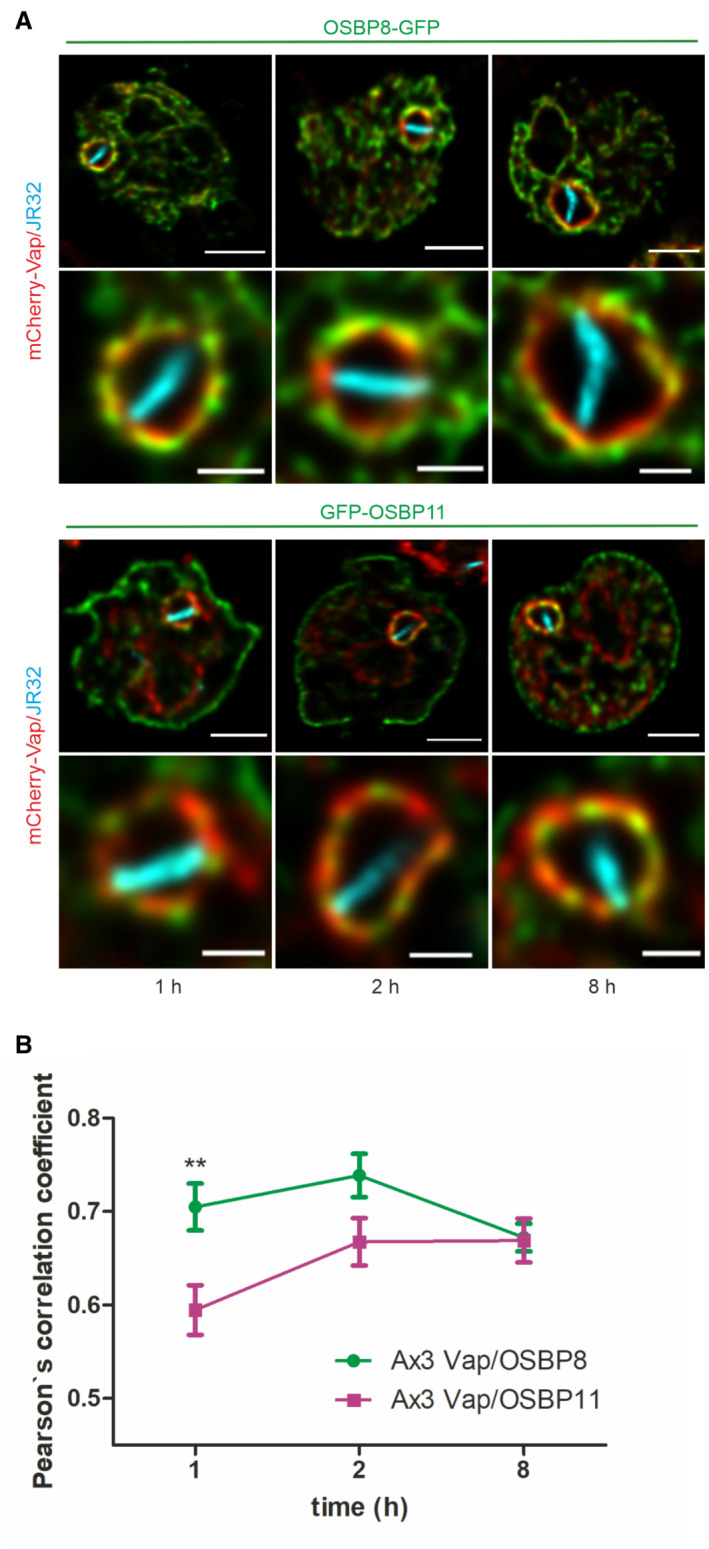

To further study the localization of LCV MCS components, we assessed the localization of Vap relative to the two most similar D. discoideum OSBPs (Fig EV1), the ER‐localizing OSBP8 and the LCV‐localizing OSBP11 (Fig 1). To this end, we used dually fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum producing mCherry‐Vap and either OSBP8‐GFP or GFP‐OSBP11 (Fig 2A and B, and Appendix Fig S2). At 1, 2 and 8 h post infection (p.i.), Vap co‐localized with OSBP8‐GFP as well as with GFP‐OSBP11. While at the earlier time points p.i. (1, 2 h), the co‐localization of Vap with OSBP8 was even more pronounced than the co‐localization with OSBP11, at 8 h p.i. the degree of co‐localization was the same, as indicated by an identical Pearson's correlation coefficient. Taken together, Vap indeed co‐localizes with the ER‐bound OSBP8 as well as with LCV‐bound OSBP11. These results support the finding that Vap localizes to the ER as well as the LCV, and they are in agreement with the notion that in D. discoideum Vap functionally connects the two compartments.

Figure 2. Vap colocalizes with OSBP8 and OSBP11 at the LCV‐ER MCS.

- Dually fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum Ax3 producing mCherry‐Vap (pSV048) and OSBP8‐GFP (pMIB89) or GFP‐OSBP11 (pMIB39) were infected (MOI 5, 1–8 h) with mCerulean‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pNP99) and fixed with 4% PFA. Merged images for the analyzed time points are shown. Scale bars: 3 μm (insets: 1 μm).

- The Pearson's correlation coefficient was generated using Coloc 2 from Fiji (ImageJ) and is shown for OSBP8 or OSBP11 fused to GFP with respect to mCherry‐Vap (n = 100–150 each per time point). Data represent mean and SEM of three independent biological replicates (**P < 0.01, Student's t‐test).

Proteomics of LCVs from D. discoideum wild‐type and Δsey1 reveals MCS components

The ER tubule‐resident large GTPase Sey1/Atl3 (DDB_G0279823) promotes the accumulation of ER on LCVs, and in absence of Sey1, significantly less ER localizes on the pathogen vacuole, while the PtdIns(4)P‐positive LCV appears to form normally (Steiner et al, 2017; Hüsler et al, 2021). Accordingly, formation of the LCV‐ER MCS might be compromised in the D. discoideum Δsey1 mutant strain. To test this hypothesis and to gain further insights into the process of LCV‐ER MCS formation, we analyzed by comparative proteomics LCVs from the L. pneumophila‐infected D. discoideum Ax3 wild‐type strain or the Δsey1 mutant. This approach revealed 2,434 LCV‐associated D. discoideum proteins (Dataset EV1), of a total of 13,126 predicted D. discoideum proteins (UniprotKB). Moreover, 1,224 L. pneumophila proteins were identified (among 3,024 predicted L. pneumophila proteins). This is a reasonable number of proteins identified from an intracellular bacterial pathogen within its vacuole given the LCV isolation and proteomics methods applied (Herweg et al, 2015; Schmölders et al, 2017).

The LCV‐associated proteins include MCS components such as the OSBPs OSBP7 (osbG) and OSBP8 (osbH), and the PtdIns(4)P 4‐phosphatase Sac1 (Dataset EV1; highlighted). Furthermore, we identified many ER and Golgi proteins, as well as proteins implicated in membrane dynamics and vesicle trafficking (Dataset EV1; highlighted). These include the hydrolase receptor sortilin, the ER proteins calnexin, calmodulin, calreticulin and reticulon, the ER‐Golgi intermediate compartment protein‐3 (Ergic3), the Golgi proteins golvesin and YIPF1, the vesicle transport through interaction with t‐SNAREs homolog 1A (Vti1A), the vesicle‐associated membrane protein‐7A/B (Vamp7A/B), the vesicle‐fusing ATPase (NsfA), the vacuolar protein sorting‐associated proteins Vps26, Vps29, and Vps35 (retromer coat complex subunits), dynamin A/B (DymA/B), dynamin‐like protein A/C (DlpA/C), syntaxins (5, 7A/B, 8A/B), t‐SNAREs, synaptobrevin B, α‐SNAP, and many small GTPases or their modulators. Moreover, we identified the interaptin AbpD (Rivero et al, 1998), the metal ion transporter Nramp1 (Peracino et al, 2006; Buracco et al, 2015), and the GPCR and receptor protein kinase RpkA (Riyahi et al, 2011; Dataset EV1, highlighted). Finally, many mitochondrial proteins were found to associate with LCVs, in agreement with the findings that mitochondria communicate with LCVs and L. pneumophila modulates mitochondrial function during infection (Escoll et al, 2017).

We also identified L. pneumophila Icm/Dot T4SS substrates on LCVs from infected D. discoideum Ax3 and Δsey1 (Dataset EV1, highlighted). These L. pneumophila effectors include the PtdIns 4‐kinase/Rab1 GTPase activating protein (GAP) LepB (Ingmundson et al, 2007; Dong et al, 2016), the PtdIns(4)P‐binding effectors SidC, its paralogue SdcA, and SidM/DrrA (Luo & Isberg, 2004; Weber et al, 2006; Brombacher et al, 2009), as well as the retromer interactor RidL (Finsel et al, 2013) and the deAMPylase SidD (Neunuebel et al, 2011; Tan & Luo, 2011).

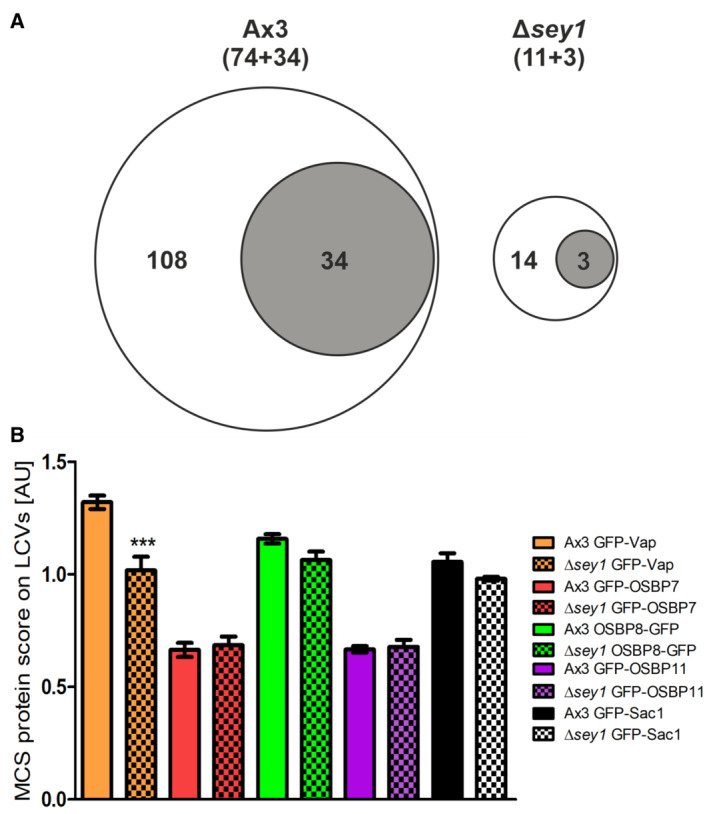

Seventy‐four D. discoideum and 34 L. pneumophila proteins were identified only on LCVs from D. discoideum Ax3 but not from Δsey1 mutant amoeba, while 11 host and three bacterial proteins were present only on LCVs from Δsey1 mutant amoeba but not from the parental strain Ax3 (Fig EV2A and Dataset EV1, highlighted). Among the host proteins present only on LCVs from D. discoideum Ax3, we identified several putative MCS components possibly involved in (PI‐driven) lipid transport (OSBP7, Vps13B, CRAL‐TRIO domain protein), as well as proteins possibly implicated in ER‐Golgi transport (TRAPPC3, YIPF5, γ‐SNAP), or localizing to the ER (syntaxin18, calmodulin, Sey1; Dataset EV1, highlighted). Among the L. pneumophila proteins identified only on LCVs from D. discoideum Δsey1 was the PtdIns(4)P‐binding effector Lpg2603 (Hubber et al, 2014; Sreelatha et al, 2020; Dataset EV1, highlighted).

Figure EV2. Proteomics of D. discoideum wild‐type or Δsey1 reveals MCS components.

- Comparative proteomics was performed by mass spectrometry with LCVs purified from L. pneumophila‐infected D. discoideum Ax3 or Δsey1 (for details see Materials and Methods). Among the total of 3,658 eukaryotic or bacterial proteins identified, the Venn diagrams show proteins identified in biological triplicates only on LCVs from D. discoideum Ax3 (108 proteins; 74 D. discoideum, 34 L. pneumophila) or only on LCVs from Δsey1 mutant amoeba (14 proteins; 11 D. discoideum, 3 L. pneumophila).

- Imaging flow cytometry (IFC) of D. discoideum Ax3 or or Δsey1 producing P4C‐mCherry (pWS032) and GFP fusion proteins of Vap, OSBP7, OSBP8, OSBP11, or Sac1, infected (MOI 5, 1 h) with mPlum‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pAW014). Mean IFC colocalization score and standard error of mean (SEM) for MCS component GFP fusion proteins for > 5,000 LCVs is depicted. The data are representative for three independent biological replicates (***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test).

In order to validate the localization of MCS components to LCVs, we used imaging flow cytometry (IFC; Fig EV2B). To this end, GFP fusion proteins of Vap, OSBP7, OSBP8, OSBP11 or Sac1 were produced in D. discoideum Ax3 or Δsey1 alongside the PtdIns(4)P/LCV probe P4C‐mCherry (Steiner et al, 2017). All putative MCS components were found to localize to PtdIns(4)P‐positive LCVs, and significantly less Vap accumulated on LCVs in Δsey1 mutant amoeba (Fig EV2B). Since IFC has a rather low spatial resolution, the PtdIns(4)P‐positive limiting LCV membrane cannot be discriminated from tightly associated ER. Taken together, comparative proteomics identified MCS components on purified LCVs, the localization of which to the pathogen vacuole was confirmed by IFC. Moreover, significantly less GFP‐Vap localized to LCVs in D. discoideum Δsey1 compared with LCVs in the parental strain.

MCS components modulate the replication of L. pneumophila in D. discoideum and macrophages

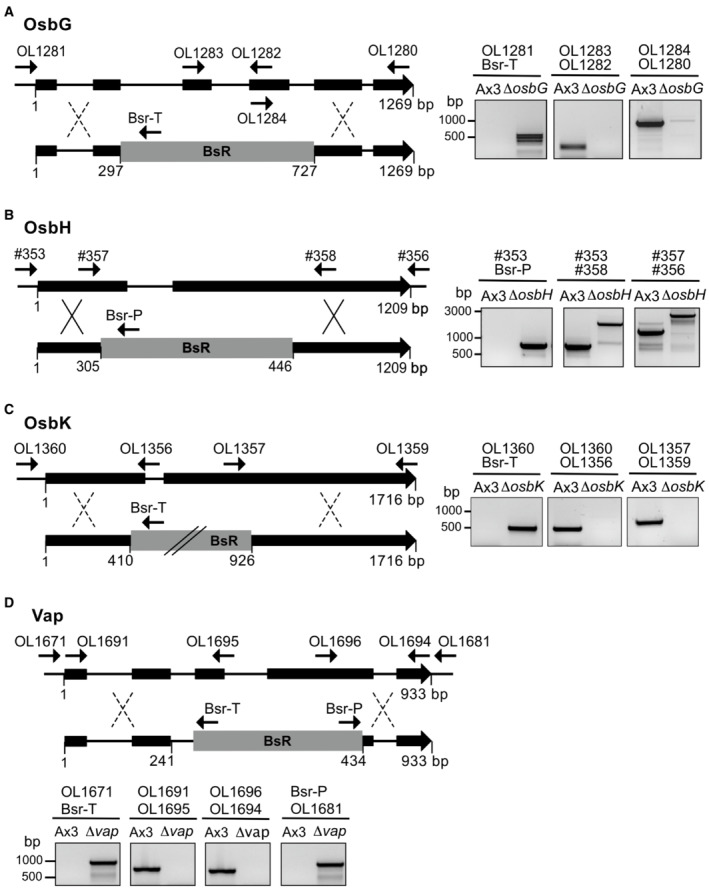

To further assess the role of the MCS components for intracellular replication of L. pneumophila and LCV formation, we constructed D. discoideum deletion mutant strains lacking vap, osbG, osbH, or osbK by disrupting the corresponding genes with a blasticidin selection marker (Fig EV3A–D). Several independent clones of the deletion mutants were picked and further analyzed. Despite repeated attempts, we failed to obtain a Δsac1 deletion mutant, and therefore, the gene might be essential in D. discoideum. Instead, we constructed and used a dominant negative Sac1 variant lacking the ER‐targeting transmembrane domain, Sac1_ΔTMD, and the catalytically inactive Sac1_C383S mutant.

Figure EV3. Construction of D. discoideum deletion mutants.

-

A–DSchematic representation of the strategies followed for the construction of D. discoideum strains lacking (A) osbG, (B) osbH, (C) osbK, or (D) vap, and PCR‐based validation of the deletions.

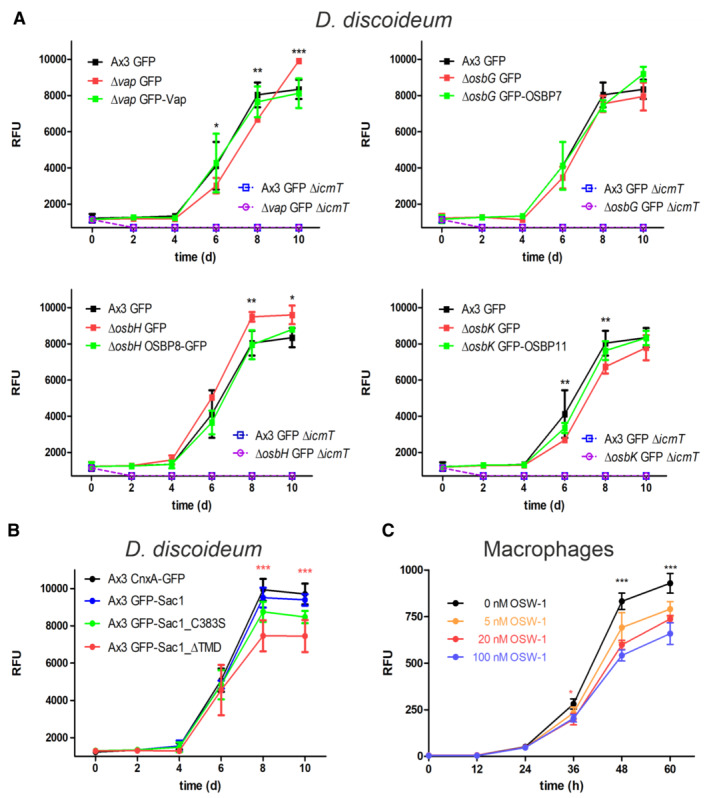

To assess the role of these putative MCS components for intracellular replication of L. pneumophila, we used mCherry‐producing bacteria and quantified fluorescence intensity (RFU; Fig 3) and colony forming units (CFU; Appendix Fig S3). We compared intracellular growth of the wild‐type L. pneumophila strain JR32 in D. discoideum Δvap, as well as in the ΔosbG, ΔosbH, and ΔosbK mutant strains (Fig 3A). In D. discoideum Δvap, intracellular bacterial growth was reduced at 4–8 days p.i. and enhanced at 10 days p.i. Moreover, intracellular bacterial growth was enhanced in D. discoideum ΔosbH, reduced in ΔosbK and not affected in ΔosbG. The intracellular growth phenotypes of L. pneumophila in the D. discoideum Δvap, ΔosbH and ΔosbK mutants were reverted by expressing the corresponding genes on a plasmid (Fig 3A). The intracellular growth of L. pneumophila strain JR32 was similar in D. discoideum Ax3 producing GFP, GFP‐Sac1 or GFP‐Sac1_C383S but significantly reduced in amoeba producing GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD (Fig 3B and Appendix Fig S3). These results are in agreement with the notion that Sac1 is implicated in intracellular growth of L. pneumophila, and Sac1_ΔTMD but not GFP‐Sac1_C383S interfere with growth in a dominant negative manner. An L. pneumophila ΔicmT mutant, lacking a functional Icm/Dot T4SS, did not replicate in any of the D. discoideum mutant strains (Fig 3A). Taken together, compared with the parental D. discoideum strain, L. pneumophila replicates less efficiently in absence of the MCS components Vap or OSBP11 and upon the production of Sac1_ΔTMD, while the bacteria replicate more efficiently in absence of OSBP8 (Table 1).

Figure 3. MCS components modulate replication of L. pneumophila in D. discoideum and macrophages.

- Dictyostelium discoideum Ax3, or the ∆vap, ∆osbG, ∆osbH, or ∆osbK mutant strains producing GFP (pDM317) or GFP fusions of the MCS components were infected (MOI 1) with mCherry‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pNP102), and intracellular replication was assessed by relative fluorescence units (RFU). Mean and SEM of three independent biological replicates are shown (statistics refer to JR32 infected D. discoideum Ax3 producing GFP; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test). To improve clarity, the different mutant strains are shown in separate graphs, each depicting the same data for Ax3/GFP.

- Dictyostelium discoideum Ax3 producing CnxA‐GFP (pAW016), GFP‐Sac1 (pLS037), GFP‐Sac1_C383S (pSV015), or GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD (pSV034) were infected (MOI 1) with mCherry‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pNP102), and intracellular replication was assessed by relative fluorescence units (RFU). Mean and SEM of three independent biological replicates are shown (statistics refer to JR32 infected D. discoideum Ax3 producing GFP‐Sac1; ***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test).

- RAW 264.7 macrophages were treated with increasing concentrations of OSW‐1 (0–100 nM, 1–60 h), infected (MOI 1) with GFP‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pNT28), and intracellular replication was assessed by relative fluorescence units (RFU). Mean and SEM of three independent biological replicates are shown (statistics refer to infected cells treated with 0 nM OSW‐1; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test).

ORP8 (osbpl8) was identified on LCVs purified from L. pneumophila‐infected RAW 264.7 macrophages (Hoffmann et al, 2014a; Schmölders et al, 2017), suggesting that ORPs and MCS components might also play a role for LCV formation in mammalian cells. To assess the role of MCS components for intracellular replication of L. pneumophila in mammalian cells, we used a pharmacological approach. Upon treatment of RAW 264.7 macrophages with the steroidal saponin ORP inhibitor OSW‐1 (Mesmin et al, 2017), the intracellular replication of GFP‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 was significantly inhibited in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig 3C). While OSW‐1 is not exclusively specific as an inhibitor of ORPs, the pharmacological data are in agreement with the notion that MCS components also promote the intracellular replication of L. pneumophila in macrophages. In summary, genetic and pharmacological data indicate that MCS components are implicated in the intracellular replication of L. pneumophila in D. discoideum and macrophages.

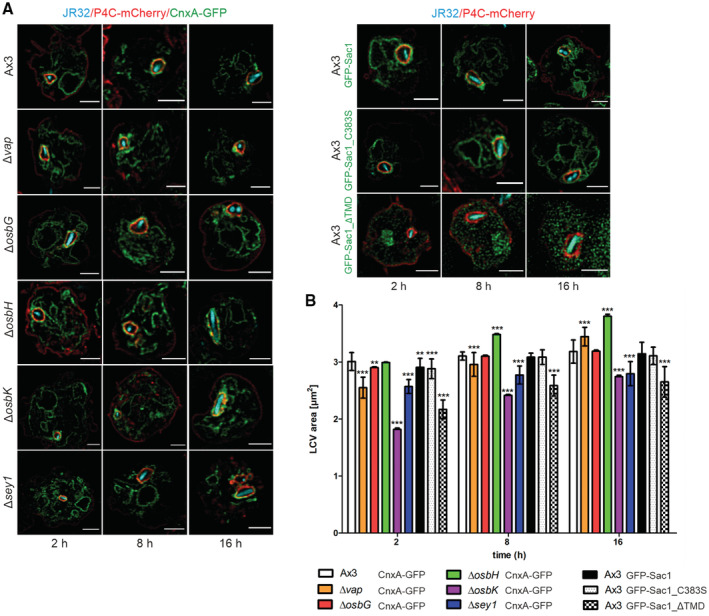

D. discoideum Vap, OSBP11 and Sac1 promote the expansion of PtdIns(4)P‐positive LCVs

Next, we sought to correlate the intracellular replication of L. pneumophila in D. discoideum lacking MCS components with alterations of the LCVs. To this end, we quantified the LCV area in D. discoideum Ax3 and compared it with the LCVs in the Δvap, ΔosbG, ΔosbH, ΔosbK or Δsey1 mutants or to LCVs obtained in strain Ax3 upon production of GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD (Fig 4A and Appendix Fig S4A).

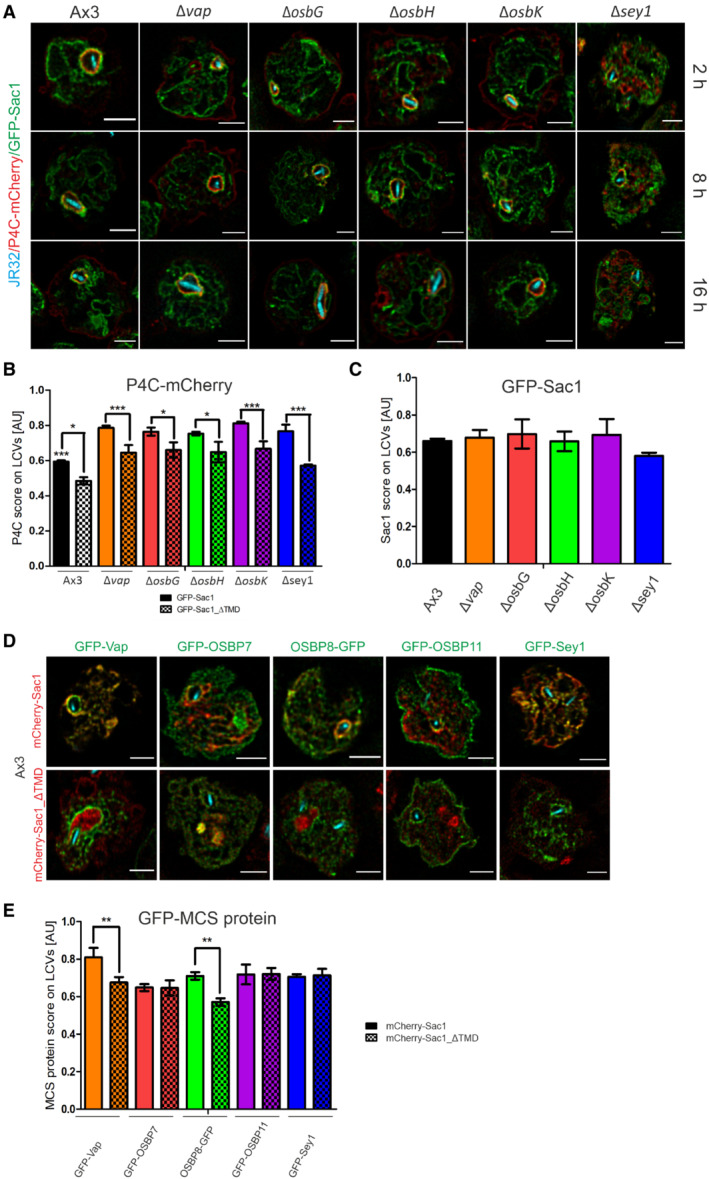

Figure 4. Vap, OSBP11, and Sac1 promote expansion of PtdIns(4)P‐positive LCVs.

- Dually fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum Ax3, ∆vap, ∆osbG, ∆osbH, ∆osbK or ∆sey1 mutants producing P4C‐mCherry (pWS032) and CnxA‐GFP (pAW016), or Ax3 producing P4C‐mCherry and either GFP‐Sac1 (pLS037), GFP‐Sac1_C383S (pSV015) or GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD (pSV034) were infected (MOI 5, 2–16 h) with mCerulean‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pNP99) and fixed with 4% PFA. Merged images for the analyzed time points are shown. Scale bars: 3 μm.

- LCV area was measured using ImageJ (n = 100–200 per condition from three independent biological replicates). Means and SEM of single cells are shown (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test).

Compared with LCVs in D. discoideum Ax3, LCVs in the Δvap strain were significantly smaller at 2 and 8 h p.i., and larger at 16 h p.i. (Fig 4B). Moreover, the LCVs were significantly smaller in the ΔosbK mutant strain at 2, 8 and 16 h p.i., larger in the ΔosbH mutant at 8 and 16 h p.i. and did not change in the ΔosbG mutant (Fig 4B). Intriguingly, the LCVs in the ΔosbK mutant strain were even smaller than in the Δsey1 mutant used as a control (Hüsler et al, 2021). The production of GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD in D. discoideum Ax3 significantly reduced the LCV size at 2, 8 and 16 h p.i. compared with amoeba producing GFP‐Sac1 or GFP‐Sac1_C383S (Fig 4B). Upon production of GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD in the Δvap, ΔosbG, ΔosbH, ΔosbK, or Δsey1 mutant strains the LCV size was also reduced at all time points p.i. compared with amoebae producing GFP‐Sac1 (Appendix Fig S4B). Taken together, reduced intracellular replication in some D. discoideum strains (Δvap, ΔosbK, Δsey1, and Sac1_ΔTMD) is positively correlated with a reduced LCV expansion, and increased intracellular replication in the ΔosbH mutant is correlated with an enhanced LCV expansion (Table 1).

Sac1_ΔTMD reduces the accumulation of PtdIns(4)P, Vap and OSBP8 on LCV‐ER MCS

We then sought to assess the effects of D. discoideum MCS components on the LCV PtdIns(4)P levels. To this end, we infected amoeba with either mCerulean‐ or mPlum‐producing L. pneumophila and analyzed PtdIns(4)P on LCVs by confocal microscopy and imaging flow cytometry (IFC) using dually labeled D. discoideum strains producing P4C‐mCherry and either GFP‐Sac1 (Fig 5A and B, and Appendix Fig S5) or GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD (Figs 1A, 4A, and 5B and D, and Appendix Figs S1A, S4A, and S6).

Figure 5. Sac1_ΔTMD reduces the accumulation of PtdIns(4)P, Vap and OSBP8 on LCVs.

-

ADually fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum Ax3, ∆vap, ∆osbG, ∆osbH, ∆osbK or ∆sey1 mutants producing P4C‐mCherry (pWS032) and GFP‐Sac1 (pLS037) were infected (MOI 5, 2–16 h) with mCerulean‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pNP99) and fixed with 4% PFA. Merged images for the analyzed time points are shown. Scale bars: 3 μm.

-

B, CImaging flow cytometry (IFC) analysis of dually labeled D. discoideum Ax3, ∆vap, ∆osbG, ∆osbH, ∆osbK or ∆sey1 mutants producing P4C‐mCherry (pWS032) and either GFP‐Sac1 (pLS037) or GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD (pSV034), infected (MOI 5, 2 h) with mPlum‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pAW014).

-

DDually labeled D. discoideum Ax3 producing GFP fusions of MCS components and either mCherry‐Sac1 (pSV044) or mCherry‐Sac1_ΔTMD (pSV045) were infected (MOI 5, 2 h) with mCerulean‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pNP99) and fixed with 4% PFA. Merged images for the analyzed time points are shown. Scale bars: 3 μm.

-

EIFC analysis of dually labeled D. discoideum Ax3 producing GFP fusions of MCS components and either mCherry‐Sac1 (pSV044) or mCherry‐Sac1_ΔTMD (pSV045), infected (MOI 5, 2 h) with mPlum‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pAW014). Quantification of (B) P4C‐mCherry (C) Sac1‐GFP or (E) GFP fusions of MCS components localizing to LCVs at 2 h p.i. Due to the lower resolution of IFC, “LCVs” designates the LCV limiting membrane and tightly attached ER. Number of events per sample, n = 5,000.

Data information (B, C, E): Data represent mean and SEM of three independent biological replicates (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test).

Compared with the ectopic production of GFP‐Sac1, the production of GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD in D. discoideum Ax3 resulted in a significant decrease in the IFC P4C colocalization score (see Materials and Methods) for the acquisition of P4C‐mCherry on LCV‐ER MCV (Fig 5B). GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD localized in strain Ax3 throughout the cell and does not appear to have an organelle preference (Figs 1A and 4A). Accordingly, this result suggests that ectopic production of GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD reduces the PtdIns(4)P levels on both the ER as well as the limiting LCV membrane, which cannot be discriminated due to the lower resolution of IFC compared with confocal microscopy. Similarly, the ectopic production of GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD in the D. discoideum Δvap, ΔosbG, ΔosbH, or ΔosbK mutant strains resulted in a decrease of PtdIns(4)P on LCV‐ER MCS (Fig 5B), while GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD localized in the parental and mutant strains throughout the cell (Figs 1A, 4A, and 5B and D, and Appendix Figs S1A, S4A, and S6). At the same time the P4C colocalization score on LCV‐ER MCS in the Δvap, ΔosbG, ΔosbH, or ΔosbK mutant strains was similar among the mutants but overall higher than on LCVs in the Ax3 parental strain (Fig 5B). These findings suggest that the depletion of a single MCS component suffices to increase the overall levels of PtdIns(4)P on LCV‐ER MCS.

Upon production of GFP‐Sac1 in the D. discoideum Δvap, ΔosbG, ΔosbH, or ΔosbK mutant strains, the IFC Sac1 colocalization score was similar for all LCV‐ER MCS (Fig 5C). This result indicates that the localization of Sac1 to LCV‐ER MCS is not dependent on Vap or the OSBPs tested. The Sac1 colocalization score was slightly (but not significantly) lower in the Δsey1 mutant strain, suggesting that Sey1 might play a role in the acquisition of Sac1 to LCV‐ER MCS (Fig 5C). This result is reflected in the finding that Sey1 promotes the recruitment of ER to LCVs (Hüsler et al, 2021). In summary, compared with the production of GFP‐Sac1, the production of GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD in D. discoideum Ax3 or the Δvap, ΔosbG, ΔosbH, ΔosbK or Δsey1 mutant strains decreased the PtdIns(4)P level on LCV‐ER MCS, while Sac1 did not change, in agreement with the notion that GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD globally reduces PtdIns(4)P levels.

We also assessed by confocal microscopy and IFC the effect of Sac1_ΔTMD for the accumulation of Vap, OSBP7, OSBP8 or OSBP11 on LCVs (Fig 5D and E, and Appendix Fig S6). To this end, we used dually fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum Ax3 producing either mCherry‐Sac1 or mCherry‐Sac1_ΔTMD and GFP fusion proteins of Vap, OSBP7, OSBP8 or OSBP11. Compared with the ectopic production of mCherry‐Sac1, the production of mCherry‐Sac1_ΔTMD in D. discoideum Ax3 resulted in a significant decrease in the IFC MCS component colocalization score for the acquisition on LCV‐ER MCS of GFP fusions of Vap and OSBP8, but not OSBP7, OSBP11 or Sey1 (Fig 5E). However, the rather low resolution of IFC does not allow to spatially resolve the LCV membrane and the ER. Taken together, compared with the production of mCherry‐Sac1, the production of mCherry‐Sac1_ΔTMD in D. discoideum Ax3, decreased the levels of Vap and OSBP8 at LCV‐ER MCS, suggesting that the localization of these MCS components is regulated by PtdIns(4)P (Table 1).

PtdIns(4)P and sterol exchange occurs at LCV‐ER MCS

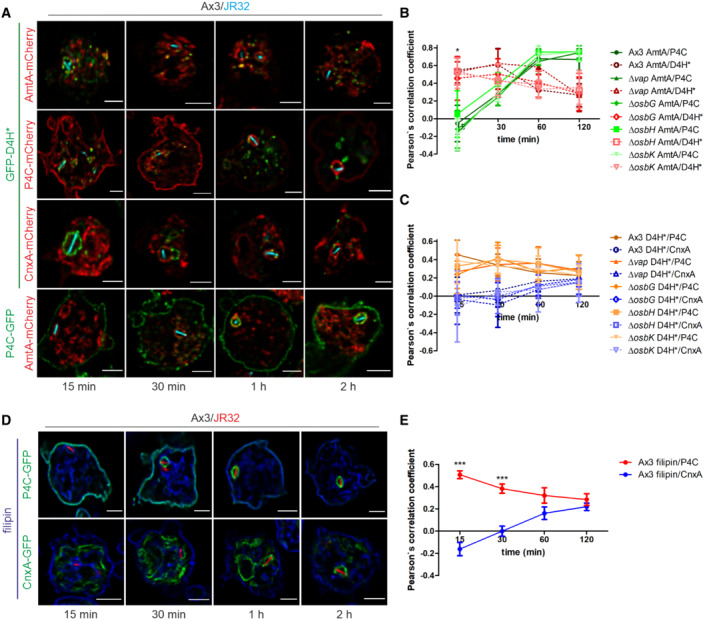

Based on the findings that PtdIns(4)P accumulates on LCVs (Weber et al, 2014), and ER‐localizing Sac1 regulates LCV remodeling (Figs 1 and 4) as well as the localization of Vap and OSBP8 (Fig 5), we sought to assess the presence and kinetics of sterols, putative counter lipids of PtdIns(4)P at MCS. To this end, we used dually fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum producing GFP‐D4H*, a sterol biosensor based on the fourth domain of Clostridium perfringens theta‐toxin (Tweten, 1988; Shatursky et al, 1999), along with mCherry fusions of P4C, calnexin or AmtA (Fig 6A–C and Appendix Fig S7). Dually labeled D. discoideum producing P4C‐GFP and AmtA‐mCherry were used as comparison.

Figure 6. PtdIns(4)P and sterol exchange at LCV‐ER MCS.

-

ADually fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum Ax3 producing GFP‐D4H* (pSV046) or P4C‐GFP (pWS034) and P4C‐mCherry (pWS032), CnxA‐mCherry (pAW012), or AmtA‐mCherry were infected (MOI 5, 15–120 min) with mCerulean‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pNP99) and fixed with 4% PFA. Merged images for the analyzed time points are shown. Scale bars: 3 μm.

-

B, CThe Pearson's correlation coefficient was generated using Coloc 2 from Fiji (ImageJ) and is shown for (B) AmtA‐mCherry with respect to P4C‐GFP or GFP‐D4H* (n = 100–150 per time point), and (C) GFP‐D4H* with respect to P4C‐mCherry or CnxA‐mCherry (n = 100–150 each per time point). Data represent mean and SEM of three independent biological replicates (*P < 0.05, Student's t‐test).

-

DSingle fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum Ax3 producing either CnxA‐GFP (pAW016) or P4C‐GFP (pWS034) were infected (MOI 5, 15–120 min) with mCherry‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pNP102), fixed with 4% PFA and stained with filipin. Merged images for the analyzed time points are shown. Scale bars: 3 μm.

-

EThe Pearson's correlation coefficient was generated using Coloc 2 from Fiji (ImageJ) and is shown for filipin with respect to CnxA‐GFP or P4C‐GFP (n = 80–90 each per time point). Data represent mean and SEM of the means of three independent biological replicates (***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test).

This approach revealed that in the course of 2 h after bacterial uptake the sterol probe GFP‐D4H* decreased on P4C‐ and AmtA‐positive membranes, while the co‐localization of GFP‐D4H* with calnexin‐positive membranes increased (Fig 6B and C). However, the overall concentration of GFP‐D4H* at the LCV decreased over 2 h (Fig 6A and Appendix Fig S7), and the Pearson's correlation coefficient was in a rather low range (−0.1 to +0.2; Fig 6C). Therefore, sterols did not seem to accumulate at the ER. Finally, the pattern of GFP‐D4H* localization was very similar for D. discoideum Ax3 and the Δvap, ΔosbG, ΔosbH, or ΔosbK mutant strains. This result indicates that these MCS components play a redundant or no role in the sterol distribution at LCV‐ER MCS.

To validate the localization of GFP‐D4H* in D. discoideum with a pharmacological sterol probe, we used the fluorescent polyene macrolide filipin, which binds to sterol pools at the plasma membrane and endosomes. This approach revealed that during 2 h after bacterial uptake filipin decreased on P4C‐positive membranes (Fig 6D and E, and Appendix Fig S8). Over the same period of time the co‐localization of filipin with calnexin‐positive membranes increased, similar to what was observed with the sterol probe GFP‐D4H*. The overall concentration of filipin at the LCV decreased over 2 h (Fig 6D and Appendix Fig S8), and the Pearson's correlation coefficient was in a rather low range (−0.2 to +0.2) (Fig 6E). These findings are again in agreement with the notion that sterols do not accumulate at the ER, but the transport of sterols from the ER might be hampered. Taken together, these results suggest that during the first 1–2 h p.i. sterols are depleted from LCVs, while in parallel PtdIns(4)P accumulates on the pathogen vacuole. Moreover, the MCS components Vap, OSBP7, OSBP8 and OSBP11 seem to play a redundant or no role in this process.

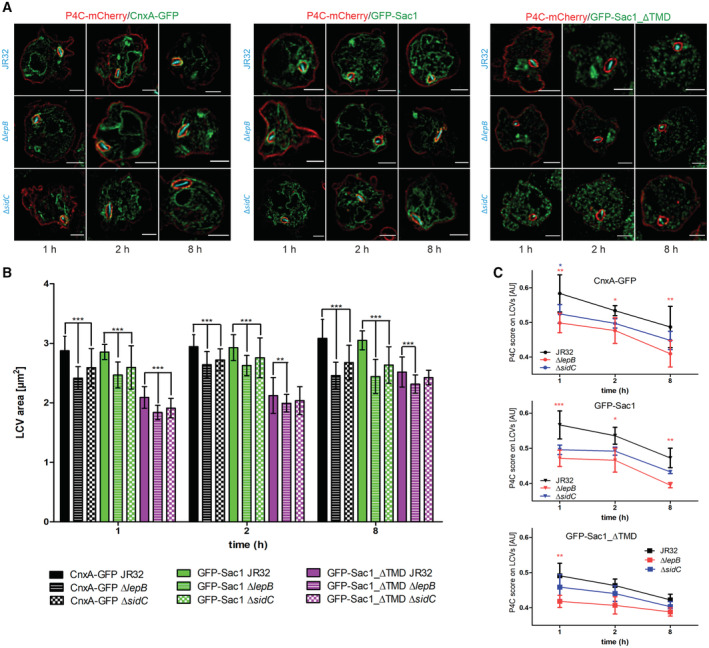

The L. pneumophila effectors LepB and SidC promote expansion of PtdIns(4)P‐positive LCVs

To assess the role of L. pneumophila effector proteins for PtdIns(4)P levels and LCV remodeling, we sought to test effectors known to produce or titrate PtdIns(4)P, and which robustly localize to LCVs (Dataset EV1, highlighted). Accordingly, we analyzed LepB, a PtdIns 4‐kinase/Rab1 GAP (Ingmundson et al, 2007; Dong et al, 2016) and SidC, a PtdIns(4)P interactor/ubiquitin ligase (Weber et al, 2006; Ragaz et al, 2008; Hsu et al, 2014; Luo et al, 2015). To test LCV remodeling by these effectors, we quantified the LCV area in D. discoideum Ax3 producing CnxA‐GFP, GFP‐Sac1 or GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD, following an infection with mCerulean‐producing L. pneumophila JR32, ΔlepB or ΔsidC (Fig 7A and Appendix Fig S9).

Figure 7. The L. pneumophila effectors LepB and SidC modulate PtdIns(4)P enrichment and expansion of LCVs.

- Dually fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum Ax3 producing P4C‐mCherry (pWS032) and either CnxA‐GFP (pAW016), GFP‐Sac1 (pLS037), or GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD (pSV034) were infected (MOI 5, 1–8 h) with mCerulean‐producing L. pneumophila JR32, ΔlepB or ΔsidC (pNP99) and fixed with 4% PFA. Merged images for the analyzed time points are shown. Scale bars: 3 μm.

- LCV area was measured using ImageJ (n = 100–200 per condition). Means and SEM of single cells are shown (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test).

- Imaging flow cytometry (IFC) analysis of dually labeled D. discoideum Ax3 producing P4C‐mCherry (pWS032) and either CnxA‐GFP (pAW016), GFP‐Sac1 (pLS037), or GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD (pSV034), infected (MOI 5, 1–8 h) with mPlum‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pAW014). Number of events per sample, n = 5,000. Data represent mean and SEM of three independent biological replicates (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test).

In D. discoideum producing CnxA‐GFP, LCVs harboring ΔlepB or ΔsidC mutant L. pneumophila were significantly smaller than LCVs harboring strain JR32 at 1, 2 and 8 h p.i. (Fig 7B). Overall, the LCVs were of similar size in D. discoideum producing GFP‐Sac1, but significantly smaller in D. discoideum producing GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD. In the latter case, LCVs harboring ΔlepB or ΔsidC mutant L. pneumophila were also significantly smaller than LCVs harboring strain JR32 at 1, 2 and 8 h p.i. (ΔlepB) and at 1 h p.i. (ΔsidC).

In order to correlate the LCV area with the PtdIns(4)P levels on the pathogen compartment, we used IFC and D. discoideum strains producing in parallel P4C‐mCherry and CnxA‐GFP, GFP‐Sac1 or GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD, infected with mPlum‐producing L. pneumophila JR32, ΔlepB or ΔsidC (Fig 7C). In all cases, the IFC colocalization score for the acquisition of P4C‐mCherry on LCVs decreased in the course of an infection (1–8 h p.i.). Compared with the parental strain JR32, the score was lowest for ΔlepB and intermediate for ΔsidC. The colocalization scores were similar in D. discoideum producing CnxA‐GFP or GFP‐Sac1, but significantly lower in D. discoideum producing GFP‐Sac1_ΔTMD. However, the rather low resolution of IFC does not allow to discriminate between the limiting LCV membrane and the adjacent ER. Taken together, the lack of the L. pneumophila PtdIns 4‐kinase/Rab1 GAP LepB or the PtdIns(4)P interactor/ubiquitin ligase SidC causes a reduction in the LCV size and the PtdIns(4)P levels at the LCV‐ER MCS. These results indicate that the L. pneumophila effector proteins LepB and SidC play a role in the PtdIns(4)P‐dependent LCV remodeling at LCV‐ER MCS.

Discussion

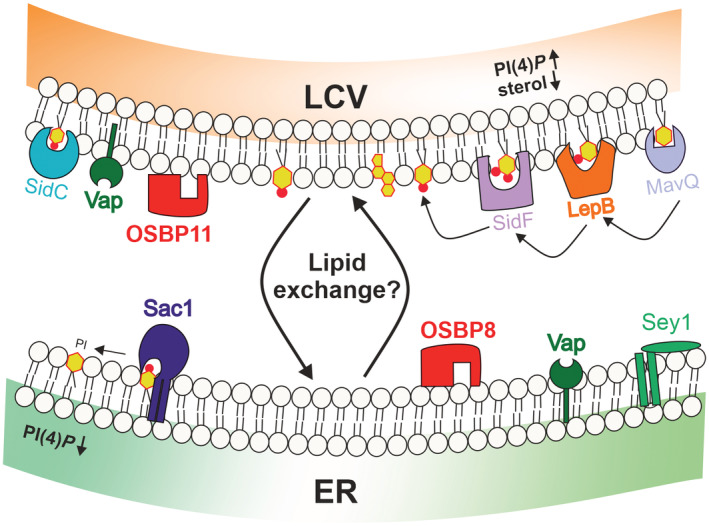

In this study, we used dually fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum amoeba and proteomics to visualize and quantify MCS components at the LCV‐ER interface (Fig 1 and Dataset EV1). The protein Vap localized to the PtdIns(4)P‐positive LCV membrane as well as the ER, while OSBP8 and Sac1 exclusively localized to the ER, and OSBP11 was detected solely on the LCV membrane (Fig 1 and Table 1). Moreover, Vap co‐localized with OSBP8 as well as with OSBP11 (Fig 2). The MCS proteins and lipids were found to be implicated in intracellular growth of L. pneumophila (Fig 3) and LCV remodeling (Figs 4 and 6). Host and bacterial factors regulate the PtdIns(4)P levels on LCVs: a derivative of the PtdIns(4)P 4‐phosphatase Sac1 lacking its membrane anchor, Sac1_ΔTMD (Fig 5), or the lack of the L. pneumophila PtdIns 4‐kinase, LepB (Fig 7), impaired pathogen vacuole remodeling and reduced the PtdIns(4)P score on LCVs. Taken together, these findings are compatible with a model where a Legionella‐ and host cell‐driven PtdIns(4)P gradient at LCV‐ER MCSs promotes Vap‐, Sac1‐ and OSBP‐dependent pathogen vacuole remodeling and intracellular bacterial replication (Fig 8). Overall, the effects of Vap and OSBPs on intracellular growth of L. pneumophila are relatively mild (Fig 3), suggesting functional redundancy of the MCS components at the LCV‐ER interface.

Figure 8. Model of localization and function of LCV‐ER MCS components.

In dually fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum amoeba MCS components such as Vap, OSBPs and Sac1 localize to the LCV‐ER interface. The host proteins Vap, OSBP8, Sac1 and Sey1 localize to the ER, and Vap as well as OSBP11 are detected on the PtdIns(4)P‐positive LCV membrane. The MCS components are implicated in LCV remodeling and intracellular growth of L. pneumophila. The PtdIns(4)P 4‐phosphatase Sac1 lacking its membrane anchor, Sac1_ΔTMD, or the lack of the L. pneumophila PtdIns(3)P 4‐kinase, LepB, reduced the PtdIns(4)P score on LCV‐ER MCS. LCV maturation implicates an increase of PtdIns(4)P and a decrease of sterols at the pathogen vacuole. The putative counter lipid(s) of PtdIns(4)P is/are unknown. Together, the findings suggest that a Legionella‐ and host cell‐driven PtdIns(4)P gradient at LCV‐ER MCS promotes Vap‐, OSBP‐ and Sac1‐dependent pathogen vacuole remodeling and intracellular bacterial growth.

We quantified LCV size changes at different infection time points to assess the role of MCS components in LCV remodeling (Fig 4). This approach revealed that Vap and even more pronouncedly OSBP11 promote LCV expansion, while OSBP8 reduces LCV expansion. Vap appears to have opposite effects on intracellular growth of L. pneumophila and promotes growth early during infection but restricts growth at later timepoints (Fig 3). These opposite effects might be explained by (direct or indirect) interactions of Vap with antagonistic OSBPs. Vap co‐localizes with OSBP8 as well as with OSBP11 on the limiting LCV membrane or the ER, respectively (Fig 2). The absence of OSBP8 (ΔosbH) or OSBP11 (ΔosbK) causes larger or smaller LCVs, and increased or reduced intracellular replication of L. pneumophila, respectively. Thus, OSBP8 restricts and OSBP 11 promotes intracellular growth. Accordingly, the opposite effects on growth of Vap might be explained by its interaction with OSBP11 early and with OSBP8 later during infection.

The size reduction of LCVs in D. discoideum Δvap or ΔosbK mutant strains was relatively small: the LCVs in the mutant strains were ca. 2–2.5 μm2, compared with ca. 3 μm2 in the Ax3 parental strain. Accordingly, these small LCV size changes likely reflect a structural remodeling of the pathogen vacuole rather than a substantial LCV expansion. MCS promote the non‐vesicular exchange of lipids in mammalian cells (Pemberton et al, 2020), and “counter lipids” transported by ORPs along a Sac1‐dependent PtdIns(4)P gradient at ER MCS include phosphatidylserine (Chung et al, 2015; Moser von Filseck et al, 2015) and cholesterol (Mesmin et al, 2013, 2017). Here, we provide evidence that within the first 1–2 h p.i. sterols are depleted from the LCV, while PtdIns(4)P accumulates (Fig 6). The kinetics of the PtdIns(4)P accumulation on LCVs are congruent with a previous study documenting that the PI lipid exchange from the endosomal PI PtdIns(3)P to the secretory PI PtdIns(4)P occurs within 1–2 h p.i. (Weber et al, 2014). Taken together, these findings are in agreement with a PtdIns(4)P/sterol lipid exchange at LCV‐ER MCS. However, since the concentration of sterols is kept low at the ER (Mesmin et al, 2017; Stefan et al, 2017), another cellular organelle is likely the “sterol acceptor compartment”. The further identification and characterization of the lipids exchanged by the LCV‐ER PtdIns(4)P gradient, the lipid trafficking routes and the specific OSBPs involved will be the subject of future studies.

The PtdIns(4)P 4‐phosphatase Sac1 affects the localization of Vap and OSBP8, since the production of Sac1_ΔTMD reduces the proteins at LCV‐ER MCS (Fig 5E). The mechanistic details of this observation are unknown, but the proper subcellular localization of Vap and OSBP8 might require a functional PtdIns(4)P gradient at LCV‐ER MCS. In addition to Sac1, other host cell factors involved in PtdIns(4)P turnover might play a role at LCV‐ER MCS. The PM‐derived PtdIns 4‐kinase IIIα (PI4KIIIα; Hubber et al, 2014) and trans‐Golgi‐derived PI4KIIIβ (Brombacher et al, 2009) promote the membrane localization of PtdIns(4)P‐binding effectors, and therefore, might modulate PtdIns(4)P levels on LCVs. Moreover, while the PtdIns(4,5)P 2 5‐phosphatase OCRL/Dd5P4 produces PtdIns(4)P on LCVs, it restricts intracellular replication of L. pneumophila (Weber et al, 2009; Finsel et al, 2013), suggesting that this PI phosphatase exerts pleiotropic and complex functions in the context of LCV formation and intracellular bacterial replication.

A massive expansion of the pathogen vacuole at later infection time points (> 8 h p.i.) is required to accommodate intracellular replication of L. pneumophila, and only very late in the infection cycle (> 48 h p.i.) LCV rupture takes place, followed by the lysis of the host amoeba within minutes (Striednig et al, 2021). This pathogen vacuole expansion is likely promoted by vesicle fusion. Indeed, LCV formation implicates the interception of (anterograde and retrograde) vesicular trafficking between the ER and the Golgi apparatus (Kagan & Roy, 2002; Nagai et al, 2002; Robinson & Roy, 2006), and nascent LCVs continuously capture and accumulate PtdIns(4)P‐positive vesicles from the Golgi apparatus (Weber et al, 2018). Further supporting the notion that ER‐derived vesicles fuse with LCVs is the finding that the SNARE Sec22b, which promotes fusion of ER‐derived vesicles with the cis‐Golgi, is recruited to LCVs shortly after infection (Derre & Isberg, 2004; Kagan et al, 2004). The fusion requires the L. pneumophila effector‐mediated activation of Rab1 on LCVs and is mediated by the non‐canonical pairing of the v‐SNARE Sec22b on the vesicles with PM‐derived t‐SNAREs such as syntaxin2, −3, −4 and SNAP23 on the LCV (Arasaki & Roy, 2010; Arasaki et al, 2012). In agreement with this scenario, syntaxins (5, 7A/B, 8A/B, 18), t‐SNAREs, α‐ and γ‐SNAP as well as Vti1A, Vamp7A/B and NsfA were identified on LCVs by proteomics (Dataset EV1).

Several Icm/Dot‐translocated L. pneumophila effector proteins were also identified on LCVs by the comparative proteomics approach (Dataset EV1). These effectors prominently include several PtdIns(4)P‐binding L. pneumophila enzymes: the ubiquitin ligase SidC and its paralogue SdcA, the Rab1 GEF/AMPylase SidM/DrrA and the phytate‐activated protein kinase Lpg2603. Furthermore, the deAMPylase and SidM antagonist SidD, as well as the retromer interactor RidL were identified on purified LCVs. To study the role of effector proteins for LCV remodeling and PtdIns(4)P levels, we analyzed the ΔlepB and ΔsidC mutant strains (Fig 7). LCVs harboring these mutant strains were smaller and showed a reduced P4C score at LCV‐ER MCS. Noteworthy, the effects were augmented in D. discoideum producing Sac1_ΔTMD. These results are readily explicable for the PtdIns 4‐kinase LepB: if this kinase is lacking, the PtdIns(4)P levels on LCVs are lower and LCV remodeling is impaired. The findings are more difficult to interpret for SidC. This effector localizes exclusively on LCVs in L. pneumophila‐infected D. discoideum (Ragaz et al, 2008; Urwyler et al, 2009; Hoffmann et al, 2014a; Schmölders et al, 2017) and tightly binds PtdIns(4)P with a dissociation constant, Kd, in the range of 240 nM (Dolinsky et al, 2014). Hence, SidC might titrate PtdIns(4)P levels on LCVs, and its absence in L. pneumophila is expected to expose more PtdIns(4)P on the pathogen vacuole. Accordingly, the finding that LCVs harboring the ΔsidC mutant strain show a lower P4C score seems to be caused by more indirect features of the effector.

The association of the LCV with ER in amoeba and macrophages represents a longstanding observation (Swanson & Isberg, 1995; Abu Kwaik, 1996), which is not understood on a molecular level. In particular, the identity of the tiny, periodic “hair‐like” structures between the pathogen vacuole and the ER is unknown. On a similar note, the identity of possible (bacterial or host) tether proteins is not known. A possible candidate for a L. pneumophila tether protein is the Icm/Dot‐secreted effector Ceg9. This effector might stabilize the LCV‐ER contact sites by directly binding to the host protein Rtn4 (Haenssler et al, 2015).

In summary, this study has revealed the importance of host and bacterial factors for MCS formation, LCV remodeling and intracellular replication of L. pneumophila. The study paves the way for an in‐depth functional and structural analysis of LCV‐ER MCS, and future studies will identify possible L. pneumophila tethering factors, which promote and stabilize the LCV‐ER MCS.

Materials and Methods

Molecular cloning

All plasmids constructed and used are listed in the Appendix Table S1. The oligonucleotides used are listed in Appendix Table S2. Cloning was performed using standard protocols, plasmids were isolated by using commercially available kits from Macherey‐Nagel, DNA fragments were amplified using Phusion High Fidelity DNA polymerase. For Gibson assembly, the NEBuilder HiFi DNA assembly kit was used. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

To construct the knockout vectors for vap, osbG, and osbK (Appendix Table S1), the corresponding 5′ fragments were amplified from D. discoideum genomic DNA with specific primer pairs oL1277/oL1278, oL1256/oL1356, or oL1687/oL1688, respectively, and cloned into the pBlueScript vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The 3′ fragments were identically produced using the matching primer pairs, oL1279/oL1280, oL1358/oL1359, or oL1693/oL1694, respectively, and cloned into pBlueScript containing the 5′ fragment. After plasmid sequence verification, the blasticidin resistance cassette was inserted between the two 5' and 3′ fragments. The final knockout vectors were digested with KpnI and NotI restriction enzymes before electroporation into Ax3 cells. Blasticidin selection (10 μg/ml) was applied 24 h after transfection. Individual colonies were tested by PCR to confirm gene replacement (Fig EV3A–D). The knockout vectors for osbH (#629), a kind gift of Prof. Markus Maniak (University of Kassel, Germany), was digested by SpeI and SphI before transfection of Ax3 cells, and transfectants were selected as described above.

The lepB deletion strain (IH03) was generated essentially as described (Tiaden et al, 2007) by double homologous recombination using counter‐selection on sucrose (Suc). The 3′ and 5′ flanking regions of lepB (lpg2490) were amplified by PCR using the primer pairs oIH011/oIH013 and oIH012/oIH014, respectively, and genomic L. pneumophila DNA as a template. The flanking regions, the KanR cassette and the pLAW344 backbone cut with the appropriate restriction enzymes were assembled using a four‐way ligation, yielding the suicide plasmid pIH29. L. pneumophila JR32 was transformed by electroporation with pIH29, and co‐integration of the plasmid was assayed by selection on CYE/Km (5–7 days, 30°C). Several clones thus obtained were picked and re‐streaked on CYE/Km, grown overnight in AYE medium (96‐well plates, 180 rpm) and streaked on CYE/Km/2% Suc. After 3–5 days at 37°C, single colonies were spotted on CYE/Cm, CYE/Km/2% Suc and CYE/Km plates to screen for CmS, KmR, SucR colonies. Double‐cross‐over events (deletion mutants) were confirmed by PCR screening and sequencing.

The constructs pMIB39 (gfp‐osbK), pMIB41 (gfp‐vap), pMIB87 (gfp‐osbG), and pMIB89 (osbH‐gfp) were constructed by PCR amplification using the primers oMIB38/oMIB39, oMIB14/oMIB12, oMIB20/oMIB18 or oMIB21/oMIB22 and cloned into plasmid pDM317 (osbK, vap, osbG) or pDM323 (osbH) after digestion with XhoI/SpeI (osbK), BamHI/SpeI (vap) or BglII/SpeI (osbG, osbH).

A GFP‐Sac1 fusion was constructed by PCR amplification of the putative open reading frame using D. discoideum genomic DNA and the primers oLS039 and oLS040, respectively. The DNA fragment was cloned into BglII and SpeI sites of pDM317, yielding pLS037 (GFP‐Sac1). The GFP‐Sac1 catalytically inactive mutant (Sac1_C383S) was obtained exchanging the codon TGT (cysteine) in position 383 to AGC coding for serine. Nucleotide substitution was carried out by site‐directed mutagenesis according to the manufacturer's recommendation (QuickChange, Agilent) using pLS037 as template and the PAGE purified primers oSV159 and oSV161 yielding pSV015 (GFP‐Sac1_C383S). The truncated GFP‐Sac1_∆TMD was obtained by deletion of the transmembrane domain of the D. discoideum sac1 gene. To this end, pLS037 excluding the transmembrane domain was amplified with the primers oSV227 and oSV228 yielding pSV034. The plasmids pSV044 and pSV045 harboring Sac1 or Sac1_ΔTMD fused to mCherry were constructed by releasing the corresponding fragments from pLS037 and pSV034 using BglII and SpeI, and ligating the fragments into the same sites of pDM1042. The plasmid pSV046 harboring an N‐terminal GFP fusion of D4H* was constructed by releasing the fragment encoding the domain from pDM1043‐D4H* using BglII and SpeI, and ligating the fragment into the same sites of pDM317. The plasmid pSV048 was constructed by releasing the vap gene from pDM317‐Vap (pMIB41) using SpeI und BglII, and ligating the fragment into the same sites of pDM1042.

Bacteria, cells, growth conditions, and transformation

Bacterial strains and cell lines used are listed in Appendix Table S1. L. pneumophila strains were grown 3 days on charcoal yeast extract (CYE) agar plates, buffered with N‐(2‐acetamido)‐2‐aminoethane sulfonic acid (ACES) at 37°C. Liquid cultures in ACES yeast extract (AYE) medium were inoculated at an OD600 of 0.1 and grown at 37°C for 21 h to an early stationary phase (2 × 109 bacteria/ml). Chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml) was added as required.

Dictyostelium discoideum stains were grown at 23°C in HL5 medium (ForMedium). Transformation of axenic D. discoideum amoeba were performed as described (Weber et al, 2014; Weber & Hilbi, 2014). Blasticidin (10 μg/ml), geneticin (G418, 20 μg/ml) and hygromycin (50 μg/ml) were appropriately added.

Murine macrophage‐like RAW 264.7 cells were cultivated in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% heat‐inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS: Life Technologies) and 1% glutamine (Life Technologies). The cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere.

Intracellular replication of Legionella pneumophila

Intracellular growth of L. pneumophila JR32 and ΔicmT in different D. discoideum strains was assessed by measuring fluorescence increase during intracellular replication of mCherry‐producing Legionella strains (relative fluorescence units, RFU) and by determining colony‐forming units (CFU).

To determine intracellular replication of mCherry‐producing L. pneumophila, D. discoideum amoebae were seeded (2 × 104 cells) in 96‐well culture‐treated plates (Thermo Fisher) and cultured in HL‐5 medium at 23°C. The cells were infected (MOI 1) with the L. pneumophila strains JR32 or ΔicmT harboring plasmid pNP102. After 21 h growth in AYE medium, the bacteria were diluted in MB medium, centrifuged (450 × g, 10 min, RT), and incubated for 1 h at 25°C (well plate was kept moist with water in extra wells). Subsequently, infected cells were washed three times with MB medium, incubated for the time indicated at 25°C, and mCherry fluorescence was measured every 2 days using a microtiter plate reader (Synergy H1, Biotek).

To assess CFUs, D. discoideum amoebae were infected (MOI 1) with mCherry‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 or ΔicmT grown for 21 h, diluted in MB medium, centrifuged and incubated for 1 h at 25°C. The infected cells were washed three times with MB medium and incubated for the time indicated at 25°C. The infected amoebae were lysed for 10 min with 0.8% saponin (Sigma‐Aldrich, 47036). Subsequently, serial dilutions were plated every 2 days on CYE agar plates containing Cam (5 μg/ml) and incubated for 3 days at 37°C. CFUs were counted using an automated colony counter (CounterMat Flash 4000, IUL Instruments, CounterMat software) and the number of CFUs (per ml) was calculated.

To test if members of the ORP family affect intracellular replication of L. pneumophila in murine RAW 264.7 macrophages, the steroidal saponin ORP inhibitor OSW‐1 (Cayman, CAY‐30310) was added at different concentrations. The macrophages were detached diluted with pre‐warmed supplemented RPMI to a concentration of 2.5 × 104 cells/140 μl medium and grown for 24 h in 96‐well plates. Liquid cultures of GFP‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pNT28) were grown for 21 h and diluted in pre‐warmed supplemented RPMI to a concentration of 5 × 104 cells/50 μl medium. A 10 μM OSW‐1 stock solution was prepared freshly. Bacterial suspensions, the OSW‐1 working solution (final concentration 5, 20 or 100 nM) and sterile DPBS were added to wells, yielding an MOI 1. The infection was synchronized by centrifugation (450 × g, 10 min). Plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. At the indicated time points (12, 24, 36, 48, 60 h p.i.) intracellular replication was assessed by measuring bacterial GFP production with a plate reader.

Confocal fluorescence microscopy of infected D. discoideum

Dually fluorescence‐labeled D. discoideum strains were infected, fixed, and imaged by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Prior to infection, exponential phase D. discoideum amoebae were seeded (1 × 105 cells per well) in HL5 medium containing geneticin (G418, 20 μg/ml) and hygromycin (50 μg/ml) in culture treated 6‐well plates (VWR) and cultured overnight at 23°C. Cells were infected (MOI 5) with mCerulean‐producing L. pneumophila JR32 (pNP99), centrifuged (450 × g, 10 min, RT) and incubated at 25°C for 1 h. Subsequently, infected cells were washed three times with HL5 medium and incubated at 25°C for the time indicated. At given time points, infected cells (including supernatant) were collected from the 6‐well plates, centrifuged (500 × g, 5 min, RT) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 30 min at RT. Following fixation, the cells were washed twice with PBS, transferred to a 18‐well μ‐slide dish (Ibidi) and immobilized by adding a layer of PBS/0.5% agarose.

Image acquisition was performed using the confocal microscope Leica TCS SP8 X CLSM (HC PL APO CS2, objective 63×/1.4–0.60 oil; Leica Microsystems) with a scanning speed of 200 Hz, bi‐directional laser scan. Pictures were acquired with a pixel/voxel size close to the instrument's Nyquist criterion of 43 × 43 × 130 nm (xyz). Images were deconvolved with Huygens professional version 19.10 software (Scientific Volume Imaging, http://svi.nl) using the CMLE algorithm, set to 10–20 iterations and quality threshold of 0.05.

To stain D. discoideum sterols with filipin, Filipin III was used (Sigma‐Aldrich, F‐4767), and a 2.5 mg/ml stock solution was prepared freshly in DMSO. The infected cells were fixed with 4% PFA (30 min, RT), and stained (final concentration: 100 μg/ml; 30 min, RT in the dark).

Imaging flow cytometry of infected D. discoideum

Processing of infected D. discoideum for IFC was performed as described (Welin et al, 2018, 2019). D. discoideum cells harboring the plasmids indicated were seeded in a 12‐well plate containing HL5 medium, geneticin and hygromycin, and infected (MOI 5) with mPlum‐producing L. pneumophila JR32, ΔlepB or ΔsidC (pAW014). The infection was synchronized by centrifugation (450 × g, 10 min, RT). The cells were incubated for 1 h at 25°C, washed three times with HL5 and incubated at 25°C. At the indicates time points cells were collected, centrifuged (450 × g, 5 min, RT) and fixed in 2% PFA for 90 min on ice. Fixed infected amoebae were washed twice in phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 20 μl ice cold PBS prior to IFC analysis.

At least 5,000 cells were acquired using an imaging flow cytometer (ImageStramX MkII, Amnis) and analyzed with the IDEAS (v6.2) software (Amnis). Infected amoeba containing one intracellular L. pneumophila bacterium were gated and assessed for colocalization of GFP and mCherry (host) with mPlum produced by the bacteria. The software computes the IFC colocalization score (bright detail similarity), which is the log‐transformed Pearson's correlation coefficient of the localized bright spots with a radius of 3 pixels or less in two images and is used to quantify relative enrichment of a marker on the LCV. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism.

Comparative proteomics of purified LCVs

LCVs from D. discoideum amoebae were purified basically as described (Urwyler et al, 2010). Briefly, D. discoideum Ax3 or Δsey1 producing CnxA‐GFP (pAW016) was seeded in T75 flasks (3 per sample) 1 day before the experiment to reach 80% confluency. The amoebae were infected (MOI 50, 1 h) with L. pneumophila JR32 producing mCherry (pNP102) grown to stationary phase (21 h liquid culture). Subsequently, the cells were washed with SorC buffer and scraped in homogenization buffer (20 mM HEPES, 250 mM sucrose, 0.5 mM EGTA, pH 7.2; Derre & Isberg, 2004). Cells were homogenized using a ball homogenizer (Isobiotec) with an exclusion size of 8 μm and incubated with a polyclonal anti‐SidC antibody (Weber et al, 2006) followed by a secondary anti‐rabbit antibody coupled to magnetic beads. The LCVs were separated in a magnetic field and further purified by a density gradient centrifugation step as described (Hoffmann et al, 2013). Three independent biological samples were prepared each for LCVs purified from L. pneumophila‐infected D. discoideum Ax3 or Δsey1.

LCVs purified by immuno‐magnetic separation and density gradient centrifugation (fraction 4) were resolved by 1D‐SDS–PAGE, the gel lanes were excised in 10 equidistant pieces and subjected to trypsin digestion (Bonn et al, 2014). For the subsequent LC–MS/MS measurements, the digests were separated by reversed phase column chromatography using an EASY nLC 1000 (Thermo Fisher) with self‐packed columns (OD 360 μm, ID 100 μm, length 20 cm) filled with 3 μm diameter C18 particles (Dr. Maisch, Ammerbuch‐Entringen) in a one‐column setup. Following loading/desalting in 0.1% acetic acid in water, the peptides were separated by applying a binary non‐linear gradient from 5 to 53% acetonitrile in 0.1% acetic acid over 82 min. The LC was coupled online to a LTQ Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, Bremen) with a spray voltage of 2.5 kV. After a survey scan in the Orbitrap (r = 60,000), MS/MS data were recorded for the 20 most intensive precursor ions in the linear ion trap. Singly charged ions were not considered for MS/MS analysis. The lock mass option was enabled throughout all analyzes.

After mass spectrometric measurement, database search against a database of D. discoideum and L. pneumophila Philadelphia‐1 downloaded Uniprot on 14/10/2019 (25,478 and 3,024 entries, respectively) as well as label‐free quantification (LFQ) was performed using MaxQuant (version 1.6.7.0; Cox & Mann, 2008). Common laboratory contaminants and reversed sequences were included by MaxQuant. Search parameters were set as follows: trypsin/P specific digestion with up to two missed cleavages, methionine oxidation and N‐terminal acetylation as variable modification, match between runs with default parameters enabled. The FDRs (false discovery rates) of protein and PSM (peptide spectrum match) levels were set to 0.01. Two identified unique peptides were required for protein identification. LFQ was performed using the following settings: LFQ minimum ratio count 2 considering only unique for quantification.

Results were filtered for proteins quantified in at least two out of three biological replicates before statistical analysis. Here, two conditions were compared by a Student's t‐test applying a threshold P‐value of 0.01, which was based on all possible permutations. Proteins were considered differentially abundant if the log2‐fold change was greater than ¦0.8¦. The dataset was also filtered for so‐called “on–off” proteins. These proteins are interesting candidates as their changes in abundance might be so drastic that their abundance is below the limit of detection in the “off” condition. To robustly filter for these proteins, “on” proteins were defined at being quantified in all three biological replicates of the Δsey1 mutant setup and in none of the replicates of the Ax3 wild‐type setup, whereas “off” proteins were quantified in none of the three biological replicates of the mutant setup but in all replicates of the wild‐type setup.

Statistical methods

Microscopy data analysis was performed without blinding and by using GraphPad Prism. The two‐sample Student's t‐test (Mann–Whitney test, no assumption of Gaussian distributions) was used. Probability values of less than 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 were used to show statistically significant differences and are represented with *, **, or ***, respectively. The value of “n” represents the number of independent biological replicates performed or the number of analyzed cells per conditions (Figs 4B and 7B). For the comparative proteomics, the summarized protein expression values were used for statistical testing of between condition differentially abundant proteins. Empirical Bayes moderated t‐tests were applied, as implemented in the R/Bioconductor limma package.

Disclosure and competing interests statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Dataset EV1

PDF+

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Markus Maniak for providing the deletion construct for osbH, Angélique Perret and Thierry Soldati for providing pDM1043‐D4H*, Leoni Swart, Xiaoli Ma, Deise G. Schäfer, and Iris Hube for help with cloning, Sebastian Grund for technical support with the preparation of MS samples, and the Center for Microscopy and Image Analysis of the University of Zürich. Work in the group of HH was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF; 31003A_175557, 310030_207826). Work in the group of DB was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; grant 031A410B). Work in the group of CB was supported by the DFG and the SFB944 (grant SFB 944/3‐P25). Work in the group of FL was supported by the Région Occitanie, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and the University of Montpellier (UM).

Author contributions

Simone Vormittag: Formal analysis; supervision; investigation; visualization; methodology; writing – original draft. Dario Hüsler: Investigation; visualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Ina Haneburger: Investigation; methodology; writing – review and editing. Tobias Kroniger: Investigation; methodology. Aby Anand: Visualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Manuel Prantl: Investigation; methodology. Caroline Barisch: Supervision; funding acquisition; visualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Sandra Maaß: Data curation; software; formal analysis; supervision; investigation; visualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Dörte Becher: Resources; supervision; funding acquisition. François Letourneur: Conceptualization; resources; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; visualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Hubert Hilbi: Conceptualization; resources; formal analysis; supervision; funding acquisition; visualization; writing – original draft; project administration.

EMBO reports (2023) 24: e56007

Data availability

The MS proteomics data discussed in this publication have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE (Perez‐Riverol et al, 2019) partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD034490 (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org/cgi/GetDataset?ID=PXD034490).

References

- Abu Kwaik Y (1996) The phagosome containing Legionella pneumophila within the protozoan Hartmannella vermiformis is surrounded by the rough endoplasmic reticulum. Appl Environ Microbiol 62: 2022–2028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arasaki K, Roy CR (2010) Legionella pneumophila promotes functional interactions between plasma membrane syntaxins and Sec22b. Traffic 11: 587–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arasaki K, Toomre DK, Roy CR (2012) The Legionella pneumophila effector DrrA is sufficient to stimulate SNARE‐dependent membrane fusion. Cell Host Microbe 11: 46–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asrat S, de Jesus DA, Hempstead AD, Ramabhadran V, Isberg RR (2014) Bacterial pathogen manipulation of host membrane trafficking. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 30: 79–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bärlocher K, Welin A, Hilbi H (2017) Formation of the Legionella replicative compartment at the crossroads of retrograde trafficking. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7: 482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boamah DK, Zhou G, Ensminger AW, O'Connor TJ (2017) From many hosts, one accidental pathogen: the diverse protozoan hosts of Legionella . Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7: 477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn F, Bartel J, Buttner K, Hecker M, Otto A, Becher D (2014) Picking vanished proteins from the void: how to collect and ship/share extremely dilute proteins in a reproducible and highly efficient manner. Anal Chem 86: 7421–7427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brombacher E, Urwyler S, Ragaz C, Weber SS, Kami K, Overduin M, Hilbi H (2009) Rab1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor SidM is a major phosphatidylinositol 4‐phosphate‐binding effector protein of Legionella pneumophila . J Biol Chem 284: 4846–4856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buracco S, Peracino B, Cinquetti R, Signoretto E, Vollero A, Imperiali F, Castagna M, Bossi E, Bozzaro S (2015) Dictyostelium Nramp1, which is structurally and functionally similar to mammalian DMT1 transporter, mediates phagosomal iron efflux. J Cell Sci 128: 3304–3316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanacci V, Mukherjee S, Roy CR, Cherfils J (2013) Structure of the Legionella effector AnkX reveals the mechanism of phosphocholine transfer by the FIC domain. EMBO J 32: 1469–1477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WY, Kim S, Aurass P, Huo W, Creasey EA, Edwards M, Lowe M, Isberg RR (2021) SdhA blocks disruption of the Legionella‐containing vacuole by hijacking the OCRL phosphatase. Cell Rep 37: 109894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung J, Torta F, Masai K, Lucast L, Czapla H, Tanner LB, Narayanaswamy P, Wenk MR, Nakatsu F, De Camilli P (2015) PI4P/phosphatidylserine countertransport at ORP5‐ and ORP8‐mediated ER‐plasma membrane contacts. Science 349: 428–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Mann M (2008) MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.‐range mass accuracies and proteome‐wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol 26: 1367–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Campo CM, Mishra AK, Wang YH, Roy CR, Janmey PA, Lambright DG (2014) Structural basis for PI(4)P‐specific membrane recruitment of the Legionella pneumophila effector DrrA/SidM. Structure 22: 397–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]