Status

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is characterized by the unnatural descent of the pelvic organs (bladder, urethra, uterus, rectum) into the vagina. Parity (defined as the number of vaginal deliveries), advanced age, and obesity are leading risk factors for POP development [1]. Beginning as early as the mid-4th century BC, various objects such as fruits (e.g., pomegranates) and metals were used to relieve the symptoms of POP [2]. These early materials blocked the pelvic organs from protruding into the vagina, like modern-day pessaries. Current pessaries, however, are primarily manufactured from plastic (e.g., silicone) and are used to treat patients who are unfit or decline surgery and for those seeking temporary relief of POP-related symptoms. Alternatively, synthetic mesh and biologic grafts are utilized in the surgical repairs of POP (Figure 1–2).

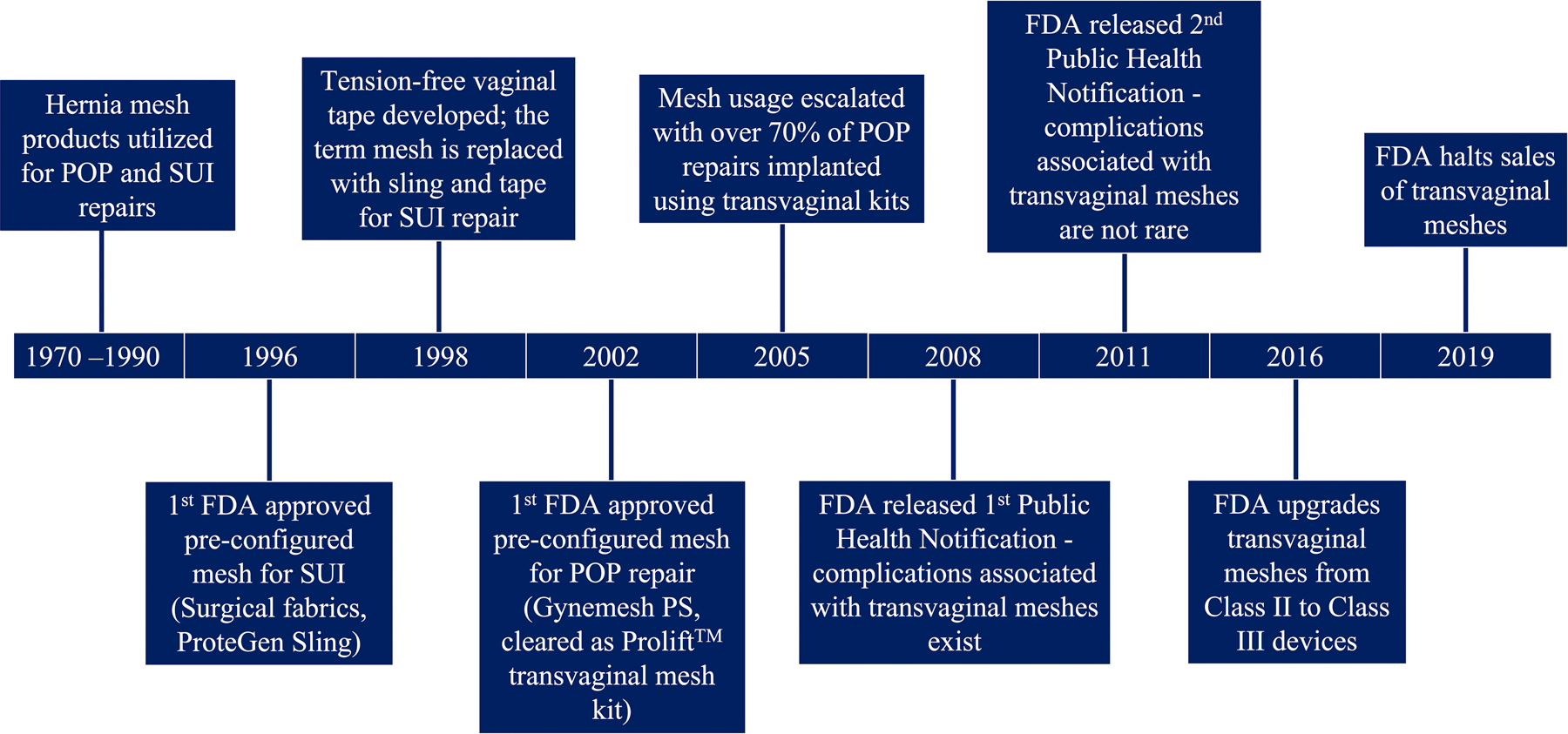

Figure 1:

Synthetic meshes have been utilized in the treatment of pelvic floor disorders for many years. Pictured is a timeline of synthetic mesh usage in pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI) repairs, focusing mainly on the progression of synthetic mesh in POP repairs. Reproduced with permission from K. M. Knight, B. R. Egnot, and P. A. Moalli, “Synthetic Mesh and Biologic Grafts: Properties and Biomechanics,” in Walters and Karram Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, 5th ed. M. D. Barber, C. S. Bradley, M. M. Karram, and M. D. Walters, Eds. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2021, ch. 7 pp. 93–114 [9].

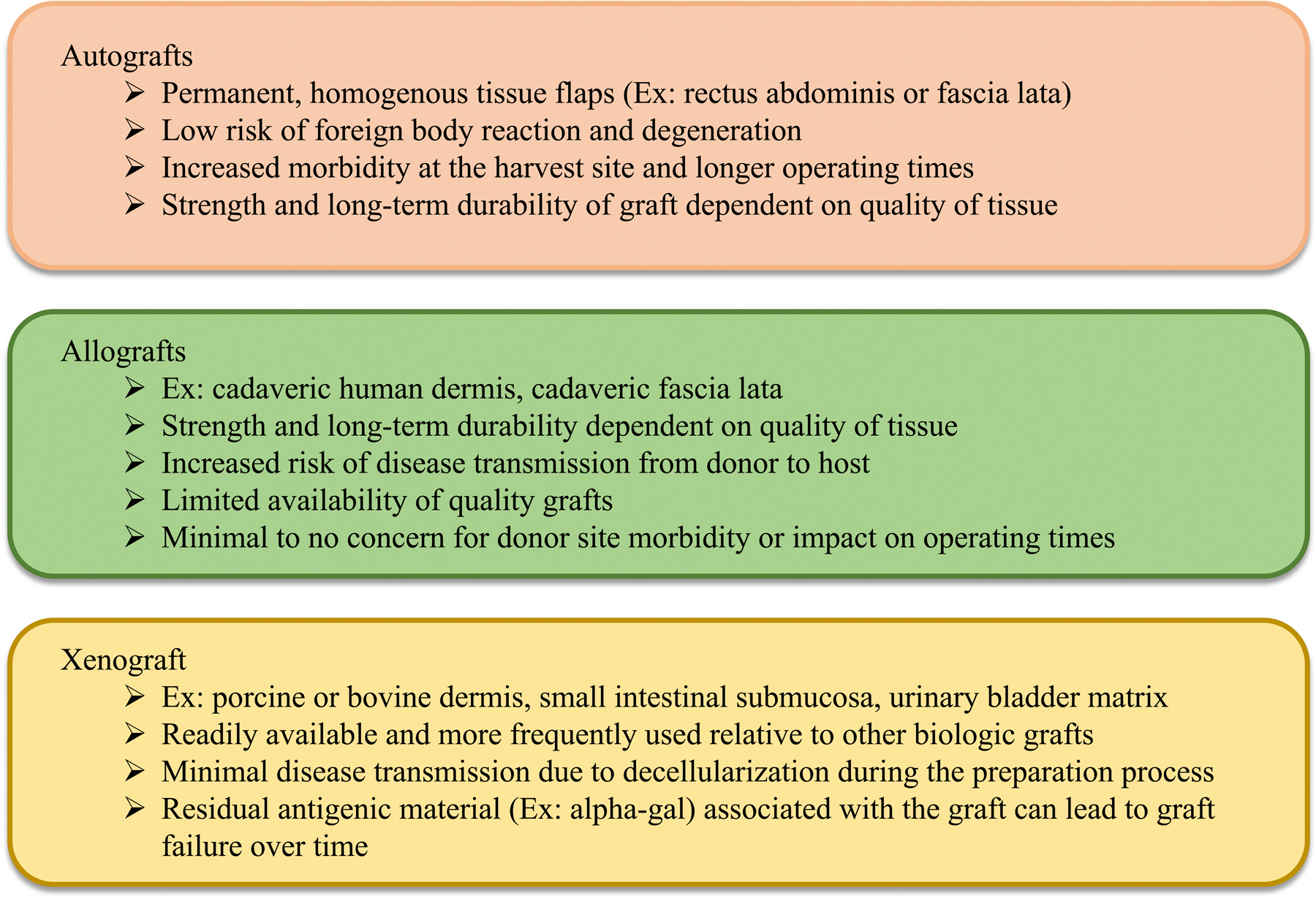

Figure 2:

There are three main types of biologic grafts utilized in pelvic organ prolapse repairs: autografts (derived from patient), allografts (human source excluding patient), and xenografts (animal source). Examples of each type of graft as well as the associated pros and cons are discussed. Reproduced with permission from K. M. Knight, B. R. Egnot, and P. A. Moalli, “Synthetic Mesh and Biologic Grafts: Properties and Biomechanics,” in Walters and Karram Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, 5th ed. M. D. Barber, C. S. Bradley, M. M. Karram, and M. D. Walters, Eds. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2021, ch. 7 pp. 93–114 [9].

Surgical repairs of POP using a patient’s own tissues are associated with unacceptably high complication rates (up to 70% at 5 years [3, 4]); thus, synthetic meshes are used to re-enforce repairs. Synthetic meshes are implanted via a transabdominal or transvaginal approach. Initially FDA approved via the 510(k) mechanism, synthetic meshes are hernia mesh products marketed for POP repairs. They were not designed for the unique biologic and mechanical environment of the female pelvis. Hence, mesh usage has been plagued by complications, particularly for transvaginally implanted meshes (~20%) [5] which ultimately caused the FDA to halt the distribution of transvaginal mesh products in 2019. Though less common, there are a concerning number of complications (~10%) [6] associated with transabdominally implanted meshes. Pain and exposure of mesh fibers through the vaginal epithelium are the two most reported complications.

Once integrated into pelvic tissues, mesh cannot be easily removed (if at all) and in some instances the reoperation results in significant removal of portions of the vagina. Despite mesh removal, often complications (especially pain) fail to resolve [7]. This is particularly concerning given that approximately 12.6% of women will undergo surgery to repair POP by age 80 and this percentage is expected to rise (~50%) by 2050 [4, 8]. Ultimately, synthetic mesh complications have left limited treatment options for surgeons and their patients and has sparked a renewed interest in biologic grafts. The etiology of synthetic mesh complications is unclear and understanding the pathogenesis of mesh complications is a critical next step towards improving patient outcomes and developing alternative biomaterials to the benefit of women worldwide.

Current and Future Challenges

Understanding the mechanisms of mesh complications is challenging given the ethical dilemmas with the procurement of human vaginal tissue. Research utilizing ex vivo mechanical testing demonstrates that mesh tensioning results in pore collapse for most meshes, which potentially leads to inadequate tissue incorporation, encapsulation, and pain [10]. Tensioning mesh also causes the mesh to wrinkle, resulting in regional increases in the concentration of mesh and a heightened foreign body response [11]. These architectural changes are observed clinically as meshes removed for complications often demonstrate pore collapse and wrinkling. Furthermore, analyzing mesh-explants removed for exposure implicate tissue degradation as a plausible mechanism of exposure whereas fibrosis has been linked to pain [12–14]. There likely exists a continuum along which mesh complications exist and understanding the factors that lead to exposure versus pain is crucial to preventing mesh complications and improving patient outcomes.

Advancements in biomaterials inventions for POP repairs are hindered by our limited knowledge of pelvic anatomy. Support to the vagina (and indirectly the pelvic organs) is provided by a complex network of connective tissues and muscles. The morphological properties (e.g., position, orientation, and shape) of vaginal anatomy consistent with a well-supported pelvis in the absence of POP is poorly defined. Furthermore, it is unclear how vaginal morphologic properties change with aging (from adolescent to adult), pregnancy and delivery, and following injury, nor how these changes are associated with POP development. Collectively, these gaps in knowledge present a challenge in developing novel biomaterials interventions for POP repairs. This is particularly true for biologic grafts and regenerative medicine approaches to POP repairs, in which an understanding of the patient specific cause of POP and the tissues needed to regenerate is key.

Identifying the ideal biomaterial for POP repairs is also a challenge. Synthetic meshes are manufactured primarily from polypropylene, which is significantly stiffer than vaginal tissue. Generally, devices that are substantially stiffer than the tissues they are designed to augment are associated with poor outcomes – a phenomenon known as stress shielding. Indeed, implanting stiff mesh onto the vagina of nonhuman primates via a transabdominal approach resulted in compromised vaginal structure and function consistent with stress shielding [15, 16]. Stiffness also was attributed to tissue degradation and mesh exposure in an ovine transvaginal model [17]. Consequently, researchers are exploring alternative (softer) materials; however, the target material stiffness is unknown. Numerous research studies have characterized the mechanical properties of the vagina and how these properties change with aging, parity, POP, and menopausal status [18]. The variations in testing protocols and inconsistences in anatomic location of samples analyzed however makes comparing results and the development of a consensus regarding the mechanical properties of the vagina difficult. Standardized protocols, increased sample sizes, and consistency in sampling location are therefore needed to manufacture a device(s) from a material that complements rather than inhibits the function of the vagina.

Advances in Science and Technology to Meet Challenges

The development of suitable animal models is key for the advancement of basic science research as it relates to mesh complication pathogenesis. Recently, Knight et al. reproduced the mesh complication of exposure by implanting deformed mesh (pores collapsed and wrinkled) onto the vagina of nonhuman primates [19]. Specifically, mesh deformation led to two differing responses: tissue degradation (likely mechanism of mesh exposure) and myofibroblast proliferation (likely mechanism of pain). Knowing that mesh deformation leads to mesh complications, researchers can use this approach to induce complications and fill the gaps in knowledge regarding mesh complication pathogenesis on both the tissue and cellular level. Furthermore, it will inform the design of mesh modifications and aid in the development of novel devices.

Defining what is “normal anatomy” will require an interdisciplinary approach with a team of researchers and clinicians working collaboratively to assess positional changes of the pelvic organs throughout a woman’s lifespan. Recently, researchers within the field have begun to combine MRI imaging and statistical shape modeling (SSM) to assess differences in anatomy, for example differences with age, pregnancy, and POP status [20]. Relatively new to the urogynecology field, SSM will serve as a powerful tool that will enhance our knowledge of anatomic changes and normality; it will also aid in the identification of patient-specific needs (including tailored devices) for POP repairs. Furthermore, SSM, along with computational modeling, can be used to predict patients at risk for developing POP, allowing for early intervention. Ultimately, understanding what tissues are compromised in POP can lead to the development of targeted regeneration using biologic grafts.

Although studies exist, there is a need for more studies (mechanical, histologic, and biochemical) investigating the structure and function of the vagina obtained from biopsies, cadavers, and animals. Similarly, the development of novel in vivo devices for vaginal mechanics are warranted. Such studies and devices will aid in the development of a device (or devices) that closely mimic the vagina. The optimization of the design of novel biomaterials for POP repair will also depend on enhancing our knowledge of the host response to mesh on both a tissue and a cellular level using both human and animal tissues.

Concluding Remarks

Great strides have been made from the initial biomaterials utilized in POP repairs to now. However, there is still more to learn. The ideal biomaterial(s) for POP repairs should be designed specifically for the unique tissues and loading conditions within the female pelvis. Ultimately, filling the gaps in knowledge of anatomy, patient-specific POP etiology, vaginal structure and function, the host (vaginal) response to biomaterials, and pathogenesis of mesh complications will be crucial to the success of future biomaterial interventions. Such gaps can be filled with an interdisciplinary research approach that combines basic science (animal models, computational modeling, imaging, SSM, in vivo measurement and imaging techniques, etc.) and clinical research. Over the next 10 to 15 years, it is anticipated that novel materials and techniques to improve the integration of biomaterials with the host will be developed to improve patient outcomes while concomitantly providing more options for patients.

Acknowledgements

KMK would like to acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health under Grant No. K12HD043441.

References

- [1].Jelovsek JE, Maher C, and Barber MD, “Pelvic organ prolapse,” Lancet, vol. 369, no. 9566, pp. 1027–1038, 2007. [Online]. Available: http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-33947203965&partnerID=40&md5=acfc0b7a783b6c91f3210ca49ca265c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Emge LA and Durfee RB, “Pelvic organ prolapse: four thousand years of treatment,” Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 997–1032, 1966. [Online]. Available: http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-0013991920&partnerID=40&md5=f227a2bbb82b422b63841bf86e309d66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Barber MD et al. , “Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: The OPTIMAL randomized trial,” JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 311, no. 10, pp. 1023–1034, 2014, doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jelovsek JE et al. , “Effect of uterosacral ligament suspension vs sacrospinous ligament fixation with or without perioperative behavioral therapy for pelvic organ vaginal prolapse on surgical outcomes and prolapse symptoms at 5 years in the OPTIMAL randomized clinical trial,” JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association, Article vol. 319, no. 15, pp. 1554–1565, 2018, doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].FDA. (2011). Surgical Mesh for Treatment of Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Stress Urinary Incontinence: FDA Executive Summary [Online] Available: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/UCM270402.pdf

- [6].Nygaard I et al. , “Long-term outcomes following abdominal sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse,” (in eng), Jama, vol. 309, no. 19, pp. 2016–24, May 15 2013, doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pace N et al. , “Symptomatic improvement after mesh removal: a prospective longitudinal study of women with urogynaecological mesh complications,” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Article vol. 128, no. 12, pp. 2034–2043, 2021, doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, and Jonsson Funk M, “Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery,” Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 123, no. 6, pp. 1201–1206, 2014. [Online]. Available: http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84901586066&partnerID=40&md5=f3213ca5ce49e060ece3fe67ae10eee0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Knight KM, Egnot BR, and Moalli PA, “Synthetic Mesh and Biologic Grafts: Properties and Biomechanics,” in Walters and Karram Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery 5th ed, Barber MD, Bradley CS, Karram MM, and Walters MD Eds. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2021, ch. 7, pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Barone WR, Moalli PA, and Abramowitch SD, “Textile properties of synthetic prolapse mesh in response to uniaxial loading,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Conference Paper vol. 215, no. 3, pp. 326.e1–326.e9, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Barone WR, Amini R, Maiti S, Moalli PA, and Abramowitch SD, “The impact of boundary conditions on surface curvature of polypropylene mesh in response to uniaxial loading,” Journal of Biomechanics, vol. 48, no. 9, pp. 1566–1574, 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.02.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nolfi AL et al. , “Host response to synthetic mesh in women with mesh complications,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 215, no. 2, pp. 206.e1–206.e8, 8// 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tennyson L, Rytel M, Palcsey S, Meyn L, Liang R, and Moalli P, “Characterization of the T-cell response to polypropylene mesh in women with complications,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 220, no. 2, pp. 187.e1–187.e8, 2019/02/01/ 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.11.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Artsen AM et al. , “T regulatory cells and TGF-β1: Predictors of the host response in mesh complications,” (in eng), Acta biomaterialia, vol. 115, pp. 127–135, Oct 1 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Feola A et al. , “Deterioration in biomechanical properties of the vagina following implantation of a high-stiffness prolapse mesh,” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, vol. 120, no. 2, pp. 224–232, 2013. [Online]. Available: http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84871247182&partnerID=40&md5=544a5a3039b0ace8125e9257ce5d21d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Liang R et al. , “Vaginal degeneration following implantation of synthetic mesh with increased stiffness,” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, vol. 120, no. 2, pp. 233–243, 2013. [Online]. Available: http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84871217055&partnerID=40&md5=87708d6a0f6daa72151f2dab22a06c27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Emmerson S et al. , “Composite mesh design for delivery of autologous mesenchymal stem cells influences mesh integration, exposure and biocompatibility in an ovine model of pelvic organ prolapse,” Biomaterials, vol. 225, p. 119495, 2019/12/01/ 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Baah-Dwomoh A, McGuire J, Tan T, and De Vita R, “Mechanical Properties of Female Reproductive Organs and Supporting Connective Tissues: A Review of the Current State of Knowledge,” Applied Mechanics Reviews, Review vol. 68, no. 6, 2016, Art no. 060801, doi: 10.1115/1.4034442. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Knight KM, King GE, Palcsey SL, Suda A, Liang R, and Moalli PA, “Mesh deformation: A mechanism underlying polypropylene prolapse mesh complications in vivo,” Acta biomaterialia, 2022/06/06/ 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Routzong MR, Rostaminia G, Moalli PA, and Abramowitch SD, “Pelvic floor shape variations during pregnancy and after vaginal delivery,” Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, vol. 194, p. 105516, 2020/10/01/ 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2020.105516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]