Summary

Introduction

Health literacy refers to “the ability to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and access health services in order to make informed choices.” In essence, being able to acquire, understand, and use information for one’s own health.

Methods

Observational study through the administration of a face-to-face questionnaire conducted between July and September 2020 on 260 individuals residing between Calabria and Sicily, aged between 18 and 89 years. Questions related to education, lifestyle (alcohol, smoking, and physical activity). Multiple-choice questions to assess health literacy and conceptual skills, ability to find information on health topics and services, use of preventive medicine especially vaccinations, and ability to make decisions about one’s own health.

Results

Of 260, 43% were male and 57% female. The most represented age group is between 50 and 59 years. Forty-eight percent of respondents had a high school diploma. 39% smoke and 32% habitually consume alcoholic beverages; only 40% engage in physical activity. Ten percent had a low level of health literacy, average 55%, and adequate 35%.

Conclusions

Given the importance of adequate HL on health choices and on individual and public wellbeing, it is essential to expand the knowledge of the individual, through public and private information campaigns and with an increasing involvement of family physicians, who are fundamental in training and informing their patients.

Keywords: Health literacy, Prevention, Public health

Introduction

Health literacy is gaining critical importance in public health. Since its introduction in the 1970s, the concept gradually expanded and continues to expand [1].

The World Health Organization during the Ninth Global Conference on Health Promotion defined health literacy as the ability of individuals to “gain access to, understand and use information in ways that promote and maintain good health” for themselves, their families and their communities” [2-3].

It is considered a determinant of health, as it is proven to influence healthy lifestyles, adherence to treatment, and appropriate access to health services, providing the foundation upon which citizens are able to play an active role in improving their health [4]. WHO supports the development of appropriate action plans to promote health literacy considering it an evolving concept, not just a personal resource; in fact, higher levels of health literacy within the population produce social welfare. Health Literacy is fundamental to patient empowerment, that is, a process through which people can gain greater control over decisions and actions that affect their health (World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe, 2012) [5].

Health literacy can be considered a factor that affects several aspects of patient care ranging from the use of preventive medicine to the adequate control of chronic diseases to mortality itself.

Poor health literacy is, therefore, related to a lower quality of life for patients and increased costs for the health care system [6].

A systematic review of the literature evaluates the association of low levels of health literacy with several health outcomes by correlating them with a higher probability of emergency room access and hospitalizations and in the elderly population with worse overall health status resulting in increased mortality [7].

The level of health literacy is also correlated with greater/lesser awareness of health-related risk factors [8-9]. The available evidence suggests that more people have limited health literacy than is often assumed. According to population data from the US, nearly half of the American adult population may have difficulties in acting on health information [10]. In Europe, findings from the recent European Health Literacy Survey indicate that 12% of the people surveyed have inadequate general health literacy, and 35% have problematic health literacy [11-12]. Although the prevalence of problematic health literacy varies widely between countries (between 2% inadequate health literacy in the Netherlands versus 27% in Bulgaria) and between groups within populations, it is clear that health literacy is not just a problem of a small minority [13].

In Italy, studies related to functional health literacy are few, a study on the general population states that 11.5% of the Italian population has a high probability of having a limited level of health literacy, it is also pointed that the elderly, the less educated and the poorer have a higher probability of having a limited or inadequate level of health literacy [14].

Eurostat has analyzed the frequency with which European citizens ask for a consultation to primary care physicians, with 75% having done so in the last year and women going more frequently. As for Italy, it is sixth to last in terms of people who have never visited a primary care physicians, but it is in first place in terms of the percentage of people who have seen a general practitioner between one and two times in a year. In light of this, we also asked about the frequency of visits with their family doctor highlighting the communication and health information received.

Despite the enormous implications of inadequate health literacy, knowledge of health literacy in the general population and how health literacy impacts health behavior and health status remain scarce [15-16]. Considering the above, the aim of our study was to evaluate the levels of health literacy in a sample of the general population residing in Calabria and Sicily.

Materials and methods

An observational study was conducted, after obtaining informed consent from respondents, by administering anonymous face-to-face questionnaires to a sample of 260 patients. Participants were selected from primary care physicians’ offices of some municipalities in the provinces of Calabria and Sicily: Reggio Calabria, Cosenza, Messina and Catania. The sample was stratified by age, sex, and level of schooling. Inclusion criteria were as follows: age between 18 and 89 years and Italian language. Exclusion criteria included cognitive impairment, severe psychiatric illness, and end-stage disease. The research was conducted for a three-month period from June 1 to September 30, 2020. Questions were asked about education level, also assessing habits and lifestyles regarding, alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking habit and physical activity. An analysis of health-specific literacy and conceptual skills was conducted through multiple-choice questions, assessing the ability to find information on health topics and services and evaluating the use of preventive medicine particularly vaccinations. Also assessed were the ability to clearly express questions and opinions, analyzing risks and benefits, and finally, being able to make decisions related to one’s own health. As far as the relationship with the family doctor is concerned, among European citizens, women go to their family doctor more frequently. The chi-squared test and p-value were used to assess statistical significance.

Results

A total of 260 subjects between 18 and 89 years of age responded to the questionnaire (mean age 49.30 SD 16.14). The most represented age is between 50 and 59 years with 27% of responses, among them there is a significant gender difference with 21.7% males and 78.3% females (chi-square 20,261; p < 0.001). Forty-three percent of respondents were male while 57% were female. At least 48% of all respondents had a high school diploma; among women, 24% had a bachelor’s degree, while among men only 13% had a bachelor’s degree. Twenty percent of respondents are retired, among women 22% are housewives and 27% of men are retired, it is not possible to assess a statistically significant correlation between occupation and gender (Tab. I).

Tab. I.

Sample representation by age, education, occupation.

| Total | Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 260) | (N = 112; 43%) | (N = 148; 57%) | ||

| Age | 18-29 | (45/260) 17% | (19/112) 17% | (26/148) 18% |

| 30-39 | (33/260) 13% | (17/112) 15% | (16/148) 11% | |

| 40-49 | (45/260) 17% | (22/112) 20% | (23/148) 16% | |

| 50-59 | (69/260) 27% | (15/112) 13% | (54/148) 36% | |

| 60-69 | (33/260) 13% | (18/112) 16% | (15/148) 10% | |

| 70-79 | (32/260) 12% | (20/112) 18% | (12/148) 8% | |

| 80-89 | (3/260) 1% | (1/112) 1% | (2/148) 1% | |

| Studies | Elementary school | (17/260) 7% | (9/112) 8% | (8/148) 5% |

| Lower middle school | (67/260) 26% | (32/112) 29% | (35/148) 24% | |

| High school | (126/260) 48% | (57/112) 51% | (69/148) 47% | |

| Graduation | (50/260) 19% | (14/112) 13% | (36/148) 24% | |

| Work | Unemployed | (39/260) 15% | (19/112) 17% | (20/148) 14% |

| Freelancer | (41/260) 16% | (23/112) 21% | (18/148) 12% | |

| Retiree | (51/260) 20% | (30/112) 27% | (21/148) 14% | |

| Public employee | (56/260) 22% | (23/112) 21% | (33/148) 22% | |

| Private employee | (20/260) 8% | (10/112) 9% | (10/148) 7% | |

| Student | (21/260) 8% | (7/112) 6% | (14/148) 9% | |

| Housewife | (32/260) 12% | 0% | (32/148) 22% | |

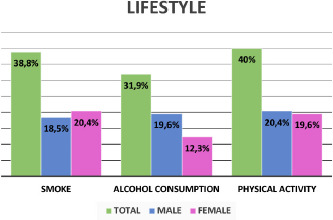

Among those who responded to the questionnaire, 39% smoke and 32% habitually consume alcoholic beverages and only 40% engage in physical activity. Evaluating statistical significance in relation to gender, we found that a highly significant correlation with alcohol consumption (chi-square = 16.777; p < 0.001) with males who drink more than females; a slightly significant correlation with physical activity (chi-square = 4.395; p < 0.036) with males engaging in more physical activity than females; in contrast, there were no significant differences related to smoking habit (chi-square = 1.332; p = 0.248) (Fig. 1). It is not possible to assess a statistically significant correlation between lifestyle variables and age and education level.

Fig. 1.

Lifestyle, gender differences.

Questions were then asked regarding basic concepts and common notions of what the health terms are most frequently encountered in daily life. Terms such as drug package insert, contraindications, posology, but also the concept of over-the-counter medication or the use of antibiotics, were not always answered correctly, as shown in Table II.

Tab. II.

Percentage of correct answers to definitions of common health terms.

| Correct Answer Total | Correct Answer Male | Correct Answer Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 260) | (n = 112; 3%) | (n = 148; 57%) | |

| What is the meaning of the term “bugiardino” (alias package insert)? | (214) 82% | (85) 76% | (129) 87% |

| What are over-the-counter medications? | (219) 84% | (92) 82% | (127) 86% |

| Are antibiotics drugs for treatment of…? | (192) 74% | (72) 64% | (120) 81% |

| What are contraindications? | (139) 53% | (60) 54% | (79) 53% |

| What does the posology represent? | (210) 81% | (85) 76% | (125) 84% |

| What is a vaccine? | (209) 80% | (85) 76% | (124) 84% |

Another section of the questionnaire investigated the knowledge in the field of prevention and in particular on vaccines and even more the fear for the same. In this case, 40% of subjects said they were afraid of the side effects of the vaccine, 44.6% do not know whether the vaccine is or is not the cause of autism as well as 45% do not know the possible correlation with an increased risk of developing allergies. Furthermore 43.5% of respondents admitted that in their opinion doctors do not provide enough information on the side effects of the vaccine (Tab. III).

Tab. III.

Questions related to vaccine knowledge.

| Total | Yes | No | Don’t know | No answer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The side effects of vaccinations worry me | (105) 40% | (107) 41% | (48) 18% | 0% |

| Vaccines are important because they prevent diseases that can have even serious effects | (203) 78% | (24) 9% | (33) 13% | 0% |

| Substances in vaccines are dangerous to humans | (46) 17,7% | (103) 39,6% | (110) 42,3% | (1) 0,4% |

| Doctors often fail to provide information about the side effects of vaccines | (113) 43,5% | (66) 25,4% | (79) 30,4% | (2) 0,8% |

| Autism could be caused by vaccinations | (51) 19,6% | (91) 35% | (116) 44,6% | (2) 0,8% |

| Vaccinations increase the risk of allergies | (40) 15% | (103) 40% | (117) 45% | 0% |

* Percentage on the total of those who answered the questionnaire.

By assigning a value of 0 to incorrect or missed responses and 1 to correct responses, it was possible to obtain ranges to assess the level of health literacy (HL), with a minimum total of 1 and a maximum of 10. On our sample of 260 individuals, the mean score obtained was 6.47 (SD 2.12). Statistical significance between the mean score and several parameters was then assessed. Considering the mean HL score obtained by males and females, the female gender has a higher score than males slightly significant Pvalue 0.046. The different occupation slightly significantly affects comparing the results obtained by public employees compared to students with a post-hoc Pvalue 0.040, where students have a higher average HL parameter value than public employees. Educational qualification highly significantly affects pvalue post-hoc 0.001, relating the mean of values obtained by high school graduates to those with only an elementary degree. In contrast, there is no correlation between HL value and age pvalue 0.124. Finally, the correlation between voluptuous habits, physical activity with the HL parameter obtained on average from the sample was evaluated. There was no significant correlation between smoking (p value 0.084) and alcohol consumption (p value 0.163) and HL. But regarding physical activity the correlation is highly significant with pvalue 0.001 those who do physical activity have a higher mean HL than those who do not (Tab. IV).

Tab. IV.

Relationship between average HL value and behavioral variables.

| Behavioral variables | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical activity (No) | Average | 6,09 | |

| Median | 6,00 | ||

| DS | 2,21 | ||

| Lowest value | 1,00 | ||

| Max value | 10,00 | ||

| IQR | 3,00 | ||

| Physical activity (Yes) | Average | 7,05 | 0.001 |

| Median | 7,00 | ||

| DS | 1,85 | ||

| Lowest value | 1,00 | ||

| Max value | 10,00 | ||

| IQR | 2,00 | ||

| Alcohol consumption (No) | Average | 6,5989 | |

| Median | 7,0000 | ||

| DS | 2,07052 | ||

| Lowest value | 2,00 | ||

| Max value | 10,00 | ||

| IQR | 3,00 | ||

| Alcohol consumption (Yes) | Average | 6,2048 | 0.162 |

| Median | 6,0000 | ||

| DS | 2,21282 | ||

| Lowest value | 1,00 | ||

| Max value | 10,00 | ||

| IQR | 3,00 | ||

| Smoke (No) | Average | 6,65 | |

| Median | 7,00 | ||

| DS | 2,00 | ||

| Lowest value | 2,00 | ||

| Max value | 10,00 | ||

| IQR | 3,00 | ||

| Smoke (Yes) | Average | 6,19 | 0.084 |

| Median | 6,00 | ||

| DS | 2,28 | ||

| Lowest value | 1,00 | ||

| Max value | 10,00 | ||

| IQR | 3,00 | ||

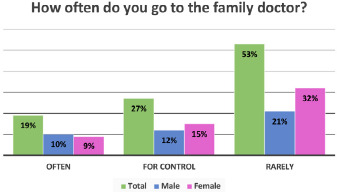

Finally, the role of the general practitioner in communication and information with their patients and the frequency with which they visit was explored (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Representation of the frequency with which subjects visit their general practitioner.

When asked if the doctor’s instructions and prescriptions on illnesses are always understandable, 70% answered yes, 59% not always and often unclear for 23%. In case of lack of clarity, only 24% ask the general practitioner for further clarification, 8% prefer to turn to a friend or acquaintance who practices medicine, 7% discuss it in the family, 3% ask the pharmacist for advice and 5% turn to the web.

With regard to information obtained via the web, 13% stated that they always resort to it after having spoken with their doctor, whereas 32% do so only a few times. Among those who make use of information obtained from social networks and medical websites, 17% do so to better understand their disease, 26% to learn more and, finally, 4% to know what to do. 16% use the web constantly to obtain information about their health and of these, 18% do not seek discussion with their doctor while 23% do so only sometimes.

87% of those who responded to the questionnaire, said they follow the instructions of the doctor for the treatment and use of drugs, but only 33% have ensured that they follow the directions of the doctor or pharmacist regarding the timing and mode of treatment, 39% do not trust either the directions of the doctor or the pharmacist and 25% follow the prescriptions only sometimes. The 12% of the subjects, stop taking drugs and antibiotics as soon as they feel better, without following the prescribed times and do it on their own initiative, without asking for the advice of the doctor.

Conclusion

From our survey has emerged a general lack of awareness of what are the terms that are most commonly encountered in everyday life about their health and care as well as a general distrust of prevention especially towards vaccines. The age group most represented in our survey is over 50 years old and 47% of them have a level of education that does not exceed a secondary school diploma. They are mainly housewives and retired people. Sixty percent of our sample does not engage in physical activity, and it is females who do less than men. On the other hand, men consume alcohol and drink significantly more than women, with significant gender differences. In our study, we stratified the responses of the subjects so that we could obtain three macro-categories, based on the formulation of correct or incorrect responses: those who have a substantially low, medium, and adequate level of functional health literacy. Of the total, 10% have an evidently low level and of these, 6% are males and 4% females; 55% have a medium-intermediate level, (25% are males and 30% females) and 35% have an adequate level (12% are males and 23% females). Compared to the national data where 63.9% of the sample has an adequate level of health literacy, our sample has an adequate HL much lower than the national average, almost halved; we are in line, however, regarding the high probability of having a limited level of literacy [14]. We also observed how belonging to the female gender affects a higher HL value, as does student status and degree, where greater education also implies greater knowledge of the terminology and meaning of common health terms. There is no correlation between basic health knowledge and age. Interesting, however, is the correlation between physical activity and HL, based on the data obtained it would seem that those who practice physical activity have a greater awareness of their health and risk factors, showing more basic health knowledge. It is interesting to point out that 19% of our sample goes frequently to the family doctor, among them most are over 50 years old and are women; 7% and 23% often or not always understand what they are told by the doctor and 10% of them do not have enough confidence in the general practitioner to follow his prescriptions or directions on health. In addition to the barriers that low health literacy creates in the context of the clinical encounter, low health literacy also reduces the likelihood that people will access the health care system in a timely manner and understand the importance of the many risk factors such as smoking, alcohol, diet, lack of physical activity, and infectious agents [17-23] and understand how not following doctor’s prescriptions in the time/dose of antibiotics gives rise to antibiotic resistance (AMR) is important drivers of increased morbidity and mortality rates resulting in rising healthcare costs. Antibiotic resistance is multifactorial and may be favored by inappropriately prescribed antibiotics or due to erroneous dosages, by empirical therapies in which broad-spectrum antibiotics are used in the absence of adequate diagnostic procedures. WHO recommends that antibiotics be used only when prescribed by a certified health care professional and in accordance with the prescription and dosage [24-25].

It is therefore essential that health promotion includes concerted efforts to raise levels of health literacy from early childhood through adulthood, taking advantage of all means of communication, media campaigns, and all living and working environments such as schools of all levels. It becomes important and indispensable for the entire health care community to make a concerted effort to guide and transmit health education that is not limited to the mere transmission of information but to educate the patient so that he or she reaches an optimal level of health literacy. In addition, it would be appropriate to involve all healthcare professionals and especially the network of family physicians, the only ones who really come into contact with women and men throughout their lives, who often show little interest in prevention, especially with regard to the importance of vaccination in general, as shown by previous studies [26-27].

Even today, universal health literacy precautions need to be recommended to facilitate a better match between people’s needs and the services and information offered through the health care system and to provide understandable and accessible information to all patients, regardless of their literacy or education level. This includes avoiding medical jargon, breaking down information or instructions into small, concrete steps, limiting the focus of a visit to three key points or activities, and assessing comprehension [28-30].

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Authors’ contributions

Writing, data processing and commentary: VA, VLF.

Statistical calculation: GT.

Data collection: CC, FM, RP.

Figures and tables

References

- [1].Van den Broucke S. Health literacy: a critical concept for public health. Arch Public Health 2014;72:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-3258-72-10 10.1186/2049-3258-72-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].#HealthInSDGs Policy brief 4: Health literacy 9th Global Conference on Health Promotion, Shanghai 2016. Available at: https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/9gchp/policy-brief1-healthy-cities.pdf?ua=1 (Accessed on: 23/08/2021). [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nutbeam D. Health promotion glossary. Health Promot Int 1998;13:349-64. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/13.4.349 10.1093/heapro/13.4.349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [4].ECOSOC. 2009. “MINISTERIAL DECLARATION – 2009 HIGH-LEVEL SEGMENT: Implementing the internationally agreed goals and commitments in regard to global public health.” Available at: https://www.un.org/en/ecosoc/julyhls/pdf09/ministerial_declaration-2009.pdf (Accessed on: 23/08/2021).

- [5].WHO. Measurement of and target-setting for well-being: an initiative by the WHO Regional Office for Europe. 2012. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/108617/e96764.pdf (Accessed on: 23/08/2021).

- [6].Hersh L, Salzman B, Snyderman D. Health Literacy in Primary Care Practice. Am Fam Physician 2015;92:118-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:97-107. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].La Fauci V, Squeri R, Genovese C, Alessi V, Facciolà A. The ‘Dangerous Cocktail’: an epidemiological survey on the attitude of a population of pregnant women towards some pregnancy risk factors. J Obstet Gynaecol 2020;40:330-5. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2019.1621818 10.1080/01443615.2019.1621818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Facciolà A, Squeri R, Genovese C, Alessi V, La Fauci V. Perception of rubella risk in pregnancy: an epidemiological survey on a sample of pregnant women. Ann Ig 2019;31(2 Suppl. 1):65-71. https://doi.org/10.7416/ai.2019.227 10.7416/ai.2019.227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Literacy. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. In: Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, eds. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2021;12:80. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-80 10.1186/1471-2458-12-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C, White S. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults – Results. From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. NAAL 2003. Report of U.S. Department of Education. NCES 2006-483. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kickbusch I, Pelikan JM, Apfel F, Tsouros A. Health Literacy: The Solid Facts. Copenhagen: World Health Organization (WHO); 2013. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/128703/e96854.pdf (Accessed on: 23/08/2021). [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bonaccorsi G, Lastrucci V, Vettori V, Lorini C. Functional health literacy in a population-based sample in Florence: a cross-sectional study using the Newest Vital Sign. BMJ Open 2019;9:e026356. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026356 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pelikan JM, Ganahl K. Measuring health literacy in general populations: primary findings from the HLS-EU Consortium’s health literacy assessment effort. Stud Health Technol Inform 2017;240:34-59. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-790-0-34 10.3233/978-1-61499-790-0-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Eurostat. 2019. How often do you see a doctor? Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20190225-1 (Accessed on: 23/08/2021).

- [17].Genovese C, La Fauci V, Costa GB, Buda A, Nucera S, Antonuccio GM, Alessi V, Carnuccio S, Cristiano P, Laudani N, Spataro P, Di Pietro A, Squeri A, Squeri R. A potential outbreak of measles and chickenpox among healthcare workers in a university hospital. EMBJ 2019;14:045-8. https://doi.org/10.3269/1970-5492.2019.14.10 10.3269/1970-5492.2019.14.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sansom-Daly UM, Lin M, Robertson EG, Wakefield CE, McGill BC, Girgis A, Cohn RJ. Health literacy in adolescents and young adults: an updated review. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2016;5:106-18. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2015.0059 10.1089/jayao.2015.0059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].La Fauci V, Alessi V, Assefa DZ, Lo Giudice D, Calimeri S, Ceccio C, Antonuccio GM, Genovese C, Squeri R. Mediterranean diet: knowledge and adherence in Italian young people. Clin Ter 2020;171:e437-e443. https://doi.org/10.7417/CT.2020.2254 10.7417/CT.2020.2254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].La Fauci V, Squeri R, Lo Giudice D, Calimeri S, Alessi V, Antonuccio GM, Genovese C. Nutritional disorders and related risk factors in a cohort of young Mediterranean population. EMBJ 2021;16:05-09. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Squeri R, Genovese C, Palamara MAR, Trimarchi G, Ceccio C, Donia V. An observational study on the effects of early and late risk factors on the development of childhood obesity in the South of Italy.Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Public Health 2018;15. [Google Scholar]

- [22].LA Fauci V, Squeri R, Spataro P, Genovese C, Laudani N, Alessi V. Young people, young adults and binge drinking. J Prev Med Hyg 2019;60:E376-E385. https://doi.org/10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2019.60.4.1309 10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2019.60.4.1309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].La Fauci V, Mondello S, Squeri R, Alessi V, Genovese C, Laudani N, Cattaruzza MS. Family, lifestyles and new and old type of smoking in young adults: insights from an italian multiple-center study. Ann Ig 2021;33:131-40. https://doi.org/10.7416/ai.2021.2419 10.7416/ai.2021.2419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].World Health Organization, Antibiotic resistance. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antibiotic-resistance (Accessed on: 23/08/2021).

- [25].La Fauci V, Alessi V. Antibiotic resistance: Where are we going? Ann Ig 2018;30(4 Supple 1):52-57. https://doi.org/10.7416/ai.2018.2235 10.7416/ai.2018.2235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Squeri R, La Fauci V, Picerno IAM, Trimarchi G, Cannavò G, Egitto G, Cosenza B, Merlina V, Genovese C. Evaluation of Vaccination Coverages in the Health Care Workers of a University Hospital in Southern Italy. Ann Ig 2019;31(2 Supple 1):13-24. https://doi.org/10.7416/ai.2019.2273 10.7416/ai.2019.2273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].La Fauci V, Squeri R, Genovese C, Anzalone C, Fedele F, Squeri A, Alessi V. An observational study of university students of healthcare area: knowledge, attitudes and behaviour towards vaccinations. Clin Ter 2019;170:e448-e453. https://doi.org/10.7417/CT.2019.2174 10.7417/CT.2019.2174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Levy H, Janke A. Health Literacy and Access to Care. J Health Commun. 2016;21 Suppl 1(Suppl):43-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1131776 10.1080/10810730.2015.1131776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hersh L, Salzman B, Snyderman D. Health Literacy in Primary Care Practice. Am Fam Physician 2015;92:118-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].DeWalt DA, Broucksou KA, Hawk V, Brach C, Hink A, Rudd R, Callahan L. Developing and testing the health literacy universal precautions toolkit. Nurs Outlook. 2011;59:85-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2010.12.002 10.1016/j.outlook.2010.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]