Summary

Background

To improve the sexual satisfaction of pregnant women, there needs to be a culturally appropriate sex education program. This study aimed at determining the effectiveness of a sexual enrichment program on the sexual satisfaction of pregnant women.

Methods

This single-blind randomized clinical trial was conducted on 61 pregnant women aged 18 to 35 years old with low-risk pregnancies and gestational ages of 14 to 32 weeks, who had referred to three healthcare centers in Mashhad. The participants were randomly assigned to two groups of control (n = 31) and intervention (n = 30) based on a table of blocks of four. The intervention group, in addition to receiving routine pregnancy training, participated in six one-hour sessions of a sexual enrichment program held on a weekly basis, while the control group received only the routine pregnancy healthcare. Larson’s sexual satisfaction questionnaire was used to assess the sexual satisfaction of pregnant women prior to the study and two weeks after the intervention. Comparison of mean scores between and within the two groups was performed using SPSS software (version 21) using independent and paired t-tests.

Results

After the intervention, there was a significant difference between the mean sexual satisfaction scores of the two groups (p = 0.02). Comparison of the differences between the mean sexual satisfaction scores of the intervention group before and after the intervention indicated a significant change (p = 0.009), while in case of the control group this change was not significant (p = 0.46).

Conclusion

A sexual enrichment program can be effective in improving the sexual satisfaction of pregnant mothers.

Keywords: Training program, Sexual satisfaction, Pregnant women, Clinical trial, Iran

Introduction

Sexual satisfaction is considered an important component of sexual health, a sexual right and an outcome of sexual well-being [1]. Sexual dissatisfaction of the couples accounts for 80% of marital conflicts and disagreements, and it causes many psychological disturbances and an increased number of infidelity [2].

Women’s sex life is affected by pregnancy. Due to multiple physical and psychological changes which occur during pregnancy, there might also be fluctuations in sexual relations of the couple, including feelings, sexual desire, the frequency of intercourse and sexual satisfaction [3, 4]. The prevalence of sexual problems in non-pregnant women is between 30% and 46%, but during pregnancy, it reaches 57-75% [5-8]. The prevalence of sexual dysfunctions in the first trimester of pregnancy is 46.6%, in the second trimester it is 34.4%, and in the third trimester, it reaches 73.3% [5, 9]. Various reports also indicate a gradual decline in sexual desire and satisfaction throughout pregnancy [10, 11]. According to a study by Lee and colleagues (2002) in Taiwan, the frequency of intercourse decreases from the first to the third trimester [12].

Although there are no specific reasons for limiting sexual activity in pregnancy, and the use of safe, hygienic and non-violent methods is innocuous [3], sexual issues are often overlooked during pregnancy, and couple’s information is often based on superstition and false beliefs [13, 14]. In some cases, the misconceptions and inadequate information of couples about sexual relationships during pregnancy and the negative attitudes toward these issues lead to the decrease or cessation of sexual relationships, which in turn results in a reduced emotional and affectionate relationships on the part of the husband and it also causes anxiety and lower self-confidence for the mother [15]. Research shows that women due to some reasons such as fear of injury to the fetus, abortion, premature rupture of the amniotic sac, preterm delivery, infection, painfulness of the intercourse, and discomfort due to large abdomen avoid sexual relationships during this period [16-18]. This will cause confusion and disagreement among the couples [19] exactly at a time when they need to be closer to each other more than any other time. Since women refrain from sexual relationship during this time, violence in couples’ relationships often begins or worsens during pregnancy [15] and men experience the first sexual relationship outside the family during the pregnancy of their wives [15, 20].

Though pregnancy can be the beginning of marital conflicts and sexual discontent, it is also a good time to create a strong sense of intimacy and mutual commitment [11, 10]. According to Lee (2002), sexual activity during pregnancy improves self-identity, empowers sexual relations, strengthens marital bonds, and reinforces the value of sexuality [12]. Since during pregnancy women have more emotional needs, their sexual orientation declines, which in many cases is rooted in their misconceptions and their beliefs, proper education and counseling can be helpful to lower the problems [21]. Through sexual counseling, people acquire the necessary information and knowledge about sexuality and form their attitudes, beliefs, and values [19]. Research has already confirmed the effect of educational interventions on the sexual performance of couples. In a study by Heidari and colleagues, it was found that the educational program had an impact on sexual performance and satisfaction of pregnant women, and therefore, the researchers concluded the effectiveness of sex education for pregnancy [5].

The sexual enrichment program is one of the educational and counseling programs on women’s sexual satisfaction. Sexual enrichment enhances couples’ current sexual relationship, and leaves no need for relationships outside of the family, and provides the couples with complete spiritual relief. In this counseling method, the couple are advised to have realistic and positive expectations. These expectations help to increase sexual satisfaction and intimacy, and intimacy in turn for each side creates a sense of the importance of the other side [22].

Despite the importance of sexual relations in pregnancy, and the emphasis of the previous studies that sexual issues should be an important part of prenatal care [23], not only such information on how couples should manage sexual life and meet sexual needs in pregnancy is not provided to couples [5, 24-29], but also during pregnancy, the couples are not provided with information and education on sexual health [5, 30, 31]. Therefore, a culturally appropriate sexual education program is required to improve the sexual satisfaction of pregnant women. Since the framework of sexual enrichment program is easy to implement, and since no study exists on this issue, it seems necessary to conduct the current study. This study aimed at determining the effectiveness of the sexual enrichment program on the sexual satisfaction of pregnant women.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN

This study was a single-blind randomized clinical trial with two groups. It was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (registration code: IRCT2016022526757N1) and is reported based on the CONSORT statement 2010 checklist.

PARTICIPANTS

This randomized clinical trial with two parallel groups (intervention and control groups) was conducted from August 2016 to February 2017 in Mashhad, Iran, on 61 pregnant women. Participants were 18 to 35-year-old women with gestational ages of 14 to 32 weeks who also had other characteristics including being healthy and at low-risk pregnancies; having singleton pregnancies; without embryonic anomalies; having no sexual problems before the pregnancy; having no medical and obstetric problems (including diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, history of drug use, placenta previa, cerclage); having no history of primary and secondary infertility; having no midwifery problems in previous pregnancies (including abortion, stillbirth, preterm labor, fetal anomalies) and having no psychological problems either themselves or their husbands. The participants and their husbands were required not to have a history of alcohol and drug abuse, and they were required to have at least elementary school education. Having no history of previous marriage or a lawsuit and a divorce request were the other inclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria also included the occurrence of medical and obstetric problems during the study, and failure to attend all educational sessions or failure to complete the questionnaires.

Based on Fatehizadeh’s study [32] and taking into account the mean difference formula, a confidence interval of 95% (α = 0.05), and a test power of 90% (β = 0/10), the minimum sample size was estimated to be 30 in each group, and with the inclusion of 10% of sample dropout, a total of 65 people were selected to take part in the study.

To select the participants, among the five health centers of Mashhad city (from number 1 to 5), three health centers (health center number 1, 2 and 5) were selected through cluster sampling. Then, a comprehensive health service center was selected from each of the centers through cluster sampling (Bahar, Shahid Fatiq and 17 Shahrivar). Subsequently, using the registry book of pregnant women, eligible women (71 women) were listed. Of these, 65 consented to participate in the study.

Randomized blocks size of 4, was used to randomly assign samples to each of the intervention and control groups. In this way, first six possible states of the blocks were listed (AABB, ABAB,ABBA, BBAA, BABA, BAAB). Then, each block was assigned a number from 1 to 6. One number (between 1 and 6) was randomly selected and individuals were assigned to the (A) and (B) based on the respective block, and this continued until the sample size was completed.

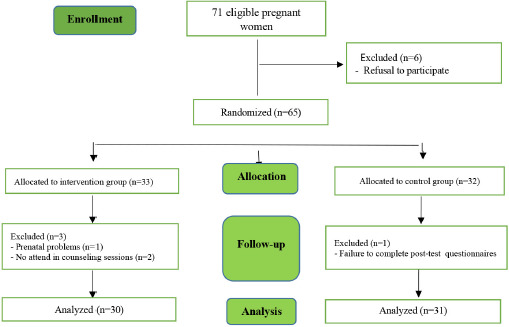

33 people were assigned to the intervention group and 32 people were assigned to the control group. Of these, 3 people in the intervention group (1 due to prenatal problems and 2 because of unwillingness to attend the counseling sessions for personal reasons) and 1 in the control group (due to failure to complete post-test questionnaires) were excluded from the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study.

PROCEDURES AND MEASUREMENTS

After extracting the names of qualified pregnant women from health records, they were contacted by telephone and the willing ones were invited to participate in the study. After obtaining written consent from the participants, all members of both groups completed the Larsson Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire. Then, the intervention group, in addition to routine healthcare, received sexual counseling sessions. Considering the appropriate number of people for group counseling and also based on the suggested time and the possibility of participants attending the counseling sessions, the intervention group was divided into 3 group counseling groups (8, 10, and 12 people).

Sexual enrichment counseling and education classes were held in form of six weekly one-hour sessions for each group in the healthcare center. The training was conducted by one of the researchers (a graduate student), who is a midwife trained in sexual counseling. Meetings included group discussions, question and answer, slideshow, assignment setting and checking the previous session’s tasks. Educational content was developed based on existing books [33], then using the judgment of specialists in sexology (as well as taking into account the educational needs of pregnant women and the Iranian culture), the content was modified. The control group received only routine pregnancy care. Two weeks after the intervention, the two groups completed Larson’s Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire again.

To maintain blindness in studying the outcome (sexual satisfaction), after determining which group the pregnant mother was assigned to, a code was assigned to her and based on that, a guide card with a code was given to her. Two weeks after the sixth session, each mother received the Larsson Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire based on the code and the card she had, while the researcher was not aware to which group the participant belonged. The content of the sessions of the enrichment program is presented in Table I.

Tab. I.

How to implement the sexual enrichment program.

First Session

|

Second Session

|

Third Session

|

Fourth Session

|

Fifth Session

|

Sixth session

|

The Larsson Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire was designed and developed by Hudson in 1981 [34]. This Questionnaire has 25 items on a five-point Likert scale which ranges from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always) [35]. All items except items 1, 2, 3, 10, 12, 13, 16, 17, 19, 21, 22 and 23 are scored in reverse. The minimum score on this scale is 25, and the maximum score is 125. A score of 25-50 indicates sexual dissatisfaction, a score of 51-75 indicates low sexual satisfaction, a score of 76-100 indicates average sexual satisfaction, and a score of 101-125 is interpreted as high sexual satisfaction. The questionnaire was completed before the intervention and then two weeks after the sixth session by both groups.

The reliability of the questionnaire in Larson’s study was confirmed with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 [35]. Bahrami and colleagues (2016) examined the face and content validity of the questionnaire and reported a Cronbach’s alpha reliability of 0.93 [36].

DATA ANALYSIS

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (Version 21). The assumption of the normality of the data distribution was checked through Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and paired t-test and independent t-test were used as the appropriate tests to compare the quantitative variables in two groups and the chi-square test was used for comparing the qualitative variables in two groups. A p-value less than 0.05 (P < 0.05) was considered statistically significant.

Results

The average age of the participants in the intervention and control groups was 27.69 ± 5.33 and 30.29 ± 5.32 years, respectively. In terms of education level, 53.4% and 54.8% of the participants in the intervention and control groups had below high school diploma education, respectively. In terms of employment status, the majority of participants in the intervention (66.7%) and control (77.4%) groups were housewives.

There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of the main characteristics such as occupation, education, kinship with husband, age difference with husband, husband’s occupation, husband’s education, type of housing, age, marriage age, Distance to previous pregnancy and gestational age (Tab. II).

Tab. II.

Comparison of demographic and midwifery characteristics of the participants in two groups of intervention and control.

| Variable | Intervention group | Control group | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 30) | (n = 31) | ||

| Qualitative variables | |||

| Occupation | |||

| Housewife | 8 (26.7) | 7 (22.6) | 0.83 |

| Working | 20 (66.7) | 24(77.4) | |

| Student | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Education | |||

| Below high school diploma | 16 (53.4) | 17 (54.8) | 0.6 |

| Diploma or Bachelor’s | 10 (33.3) | 12 (38.7) | |

| Mater’s or higher | 3 (10 ) | 1 (3.2) | |

| No answer | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Kinship with husband | |||

| Yes | 7(23.3) | 11 (35.5) | 0.4 |

| No | 22 (73.4) | 20 (64.5) | |

| No answer | 1 (3.3) | 0 | |

| Age difference | |||

| Husband is older | 25 (83.3) | 24 (77.5) | 0.75 |

| Wife is older | 5 (16.7) | 5 (16.1) | |

| The same age | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | |

| No answer | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Husband’s occupation | |||

| Employee | 8 (26.7) | 10 (32.2) | 0.76 |

| Self-employed | 21 (73.3) | 21 (67.74) | |

| No answer | 1 (3.3) | 0 | |

| Husband’s education | |||

| Below high school diploma | 18(60) | 16 (51.6) | 0.4 |

| Diploma or Bachelor’s | 8 (26.7) | 14 (45.2) | |

| Master’s or higher | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | |

| No answer | 3(10) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Housing | |||

| Owned | 11 (36.7) | 10 (32.3) | 0.13 |

| Rented | 18(60) | 18 (58.1) | |

| Others | 1 (3.3) | 3 (9.7) | |

| Quantitative variables | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| 0.06 a | |||

| Age | 27.69 ± 5.33 | 30.29 ± 5.32 | 0.1 b |

| Marriage age | 2.79 ± 1.65 | 2.79 ± 1.65 | 0.06 a |

| Distance to previous pregnancy (month) | 39.25 ± 41.45 | 75.23 ± 47.4 | |

| Gestational age before intervention (week) | 22.86 ± 3.62 | 24.42 ± 3.27 | 0.08 a |

SD: Standard Deviation;

a Independent-samples t test;

b Mann whitney test.

In both groups 88.1% of the participants were multigravidae and there was no significant difference between the two groups. Moreover, 84.7% of pregnancies were planned and 96.2% of the participants were satisfied with the fetal sex, and the two groups were not significantly different in this regard.

Prior to the intervention, the mean sexual satisfaction scores in intervention and control groups were 113.17 ± 25.06 and 110.74 ± 22.88, respectively and there was no significant difference between the groups (p = 0.69). However, after the intervention, the results of the independent t-test showed a significant difference between the mean sexual satisfaction scores of the two groups (p = 0.02). The results of paired t-test also showed a significant difference between the mean sexual satisfaction scores before and after the intervention in the intervention group (p = 0.009), but this difference was not significant in the control group (p = 0.46). Another independent t-test comparing the mean differences between the two groups before and after the intervention also showed a significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.01) (Tab. III).

Tab. III.

Comparison of sexual satisfaction scores before and after the intervention in the two groups.

| Groups | N | Befor intervention | After intervention | Difference | Paired T- test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 30 | 113.17 ± 25.06 | 120.50 ± 16.51 | 7.3 ± 14.35 | p = 0.009 |

| Control | 31 | 110.74 ± 22.88 | 109.16 ± 22.03 | 1.58 ± 11.99 | P = 0.46 |

| T- test | P = 0.69 | P = 0.02 | P = 0.01 |

SD: Standard Deviation.

Regarding the frequency of different types of touch per week in the intervention group, affectionate touch had the most frequency and the intercourse touch was the least frequent (Tab. IV).

Tab. IV.

Frequency of different types of touch in the intervention group.

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affectionate touch | 3.58 ± 1.95 | 1 | 7 |

| Sensual touch | 1.65 ± 2.79 | 1 | 7 |

| Playful touch | 1.91 ± 2.69 | 1 | 8 |

| Erotic touch | 1.69 ± 2.19 | 1 | 8 |

| Intercourse touch | 1.44 ± 1.66 | 0 | 7 |

SD: Standard Deviation.

Discussion

The present study showed that sexual enrichment program can be effective in increasing the sexual satisfaction of pregnant women. Since the sexual enrichment program in the present study focused on reformulating the attitudes of participants towards sexual activity in pregnancy and providing the knowledge required for engagement in healthy sexual relationships, the resulting enhancement of participants’ sexual satisfaction seems reasonable. In other words, training women and increasing their information reduces fear and therefore, improves their sexual satisfaction. This finding was consistent with reports of previous studies on the positive role of education of pregnant women in the improvement of their sexual performance and sexual satisfaction [5, 25, 28, 37-40].

Therefore it is recommended that couples are well educated to understand changes in sexual function during pregnancy [41]. Many studies have emphasized that sexual education during pregnancy can reduce the fear and concern of the couples, and as a result, they can continue their close and intimate relationships and sexual activity during pregnancy [42-45].

A decrease in sexual satisfaction may cause a decrease in the mental comfort of pregnant women, a disturbance in the process of pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum. Therefore, there is an obvious need for sexual counseling during pregnancy [46]. In other words, a normal sex life during pregnancy is the key to becoming parents [47].

Although in terms of the impact of educational programs on the sexual satisfaction of pregnant women the present study is in line with many other ones, it is unique because it focused on a sexual enrichment program where the false beliefs and misconceptions of the participants were recognized and through using five types of touches and providing the participants with materials and appropriate ways of sexual relationship during pregnancy, their sexual satisfaction was improved.

The findings of this study are also inconsistent with the report of Wannakosit and Phupong (2010) in which there was no significant difference between sexual behavior and sexual satisfaction of pregnant women in the control and intervention groups after sex education. The reason for this difference might be the demographic characteristics of the participants and the content and manner of implementation of the program. In the present study, six one-hour weekly sessions were held using a special educational program, while in the study conducted by Wannakosit and Phupong, the participants were trained in a 20-minute class [48].

Concerning the five-fold touches in the intervention group (affectionate touch, sensual touch, playful touch, erotic and intercourse touch), the findings showed that affectionate touch had the highest frequency and sexual touch was the least frequent. The results of the research indicate that even those who, for any reason, had had no sexual activity or full sexual intercourse and had often used non-sexual touches and had maintained warm and intimate relationships with their spouses, reported higher sexual satisfaction than what they reported before the intervention and compared to what the control group reported. This finding implies that sexual satisfaction does not necessarily mean full intercourse, a point which has also been emphasized in the protocol of the sexual enrichment and is, in fact, one of the strengths and novelties of the present study. During these emotional relationships, women are more likely to feel protected and experience more calmness and comfort during pregnancy. Evidence strongly suggests that non-genital sexual behavior is important for stimulation, pleasure, and orgasm of many people. According to Galinsky (2012), there is a positive relationship between sexual touch and satisfaction with emotional relationships. She also reported that people who do not engage in sexual touch during sexual intercourse are more likely to suffer from arousal, erection, and orgasm disorders [49].

Although the participants in the study were only pregnant women and their spouses did not participate in the training sessions, based on the implementation guidelines of the enrichment program which recommend participants to transfer information to their partners, the sexual enrichment program could increase the sexual satisfaction of the pregnant women. Heidari and colleagues (2017) also reported no significant differences in sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction of pregnant women who participated in their education programs with their spouses and received a training booklet and those who were participated in the training classes by themselves but had studied the booklet along with their spouses. The researchers concluded that if pregnant women who receive the sexual education have a good relationship with their partner, they can easily exchange educational topics with them while their spouses may not take part in the classes, a finding which is in line with the current study [5]. In line with the present study, Ghasemi Moghadam and colleagues (2012) also reported that the overall marital satisfaction in the experimental group was more than the control group and concluded that the sexual enrichment program could increase marital satisfaction even when husbands did not participate in the enrichment program [50].

Despite the fact that some previous studies have argued that increasing sexual behavior during pregnancy requires the care and understanding of the couples [48] and therefore they recommend that husbands should also participate in the sexual education programs for pregnant women [51, 52, 25, 26], since the implementation guidelines of the sexual enrichment program requires women to do some assignments and confer the information with their husbands, the obligation of husbands’ attendance in training sessions can be ignored, taking into account time and occupational inconveniences that this obligation might bring about.

The results of this study showed that sexual enrichment program can be effective in increasing the sexual satisfaction of pregnant women, even in the absence of their husbands in educational classes. Therefore, the sexual enrichment program can be used as a simple user-friendly academic framework by health personnel, especially midwifery counselors, in healthcare centers to help women solve their sexual problems in particular pregnancy situations.

LIMITATIONS

Among the limitations in implementing the study was that pregnant women due to pregnancy problems were reluctant to attend the counseling classes. Furthermore, it was not possible to predict the health condition of healthy pregnant women either and some of them because of prenatal problems could not attend the sessions and withdrew from the study. Another limitation was that the researchers could not guarantee the participants’ commitment to do the assignments and exercises. Sexual satisfaction of pregnant women requires mutual cooperation of the couple, therefore, absence of attendance spouses in counseling sessions are one of the limitations of the study.

Conclusion

The results of the study showed that the sexual enrichment program could impact on the sexual satisfaction of pregnant women. After conducting additional studies with similar methodology and larger sample size, if the findings of this study are confirmed, the integration of this program is suggested as a simple, practical and cost-effective intervention in the prenatal care system.

Ethics Approval

Before launching the study, the proposal of the study was approved of by the Ethics Committee of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences (Ethical code No: IR.SHMU.REC.1395.39) and it was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (Code: IRCT2016092930048N). Then after obtaining written permission from the concerned authorities, the researchers were introduced to the research environments. Informed written consents were also obtained from all participants.

Acknowledgment

The present study was supported by Shahroud University of medical sciences as a MSc Thesis. We hereby acknowledge the research deputy for grant.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contributions

FBG, AMN, AK, ZM, FHT: Study conception and design.

FBG, AMN: Acquisition of data.

FBG, AMN, AK, ZM, FHT: Analysis and interpretation of data.

FHT, FBG: Drafting of manuscript.

FHT: Critical revision. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Figures and tables

References

- [1].Pascoal PM, Narciso Ide S, Pereira NM. What is sexual satisfaction? Thematic analysis of lay people’s definitions. J Sex Res 2014;51:22-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.815149 10.1080/00224499.2013.815149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Shafi Abadi A, Honarparvaran N, Tabrizi M, Navabi Nezhad SH. Efficacy of emotion-focused couple therapy training with regard to increasing sexual satisfaction among, couples. Journal of clinical psychology Andisheh & Raftar 2010;4:59-70. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jahanfar S, Molae Nezhad M. Sexual Problems. 2th ed. Tehran: Bezheh & Salemi Company; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Trutnovsky G, Haas J, Lang U, Petru E. Women’s perception of sexuality during pregnancy and after birth. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2006;46:282-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00592.x 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00592.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Heidari M, Amin Shokravi F, Zayeri F, Azin SA, Merghati-Khoei E. Sexual life during pregnancy: effect of an educational intervention on the sexuality of iranian couples: a quasiexperimental study. J Sex Marital Ther 2018;44:45-55.https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2017.1313799 10.1080/0092623X.2017.1313799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Abdo CH, Oliveira WM, Jr, Moreira ED, Jr, Fittipaldi JA. Prevalence of sexual dysfunctions and correlated conditions in a sample of Brazilian women – results of the Brazilian study on sexual behavior (BSSB). Int J Impot Res 2004;16:160-6. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901198 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ahmed MR, Madny EH, Sayed Ahmed WA. Prevalence of female sexual dysfunction during pregnancy among Egyptian women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2014;40:1023-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.12313 10.1111/jog.12313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Naldoni LM, Pazmiño MA, Pezzan PA, Pereira SB, Duarte G, Ferreira CH. Evaluation of sexual function in Brazilian pregnant women. J Sex Marital Ther 2011;37:116-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2011.560537 10.1080/0092623X.2011.560537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Leite AP, Campos AA, Dias AR, Amed AM, De Souza E, Camano L. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction during pregnancy. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2009;55:563-8. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-42302009000500020 10.1590/s0104-42302009000500020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Asgari P, Pasha GH, Azar Kish M. A Comparative Study of Marital Commitment, Sexual Satisfaction, and Life Satisfaction between Employed and Unemployed Women in Dezful City. Thought Behav Clin Psychol 2011;6:53-60. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajnr-8-5-2 10.12691/ajnr-8-5-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bartellas E, Crane JM, Daley M, Bennett KA, Hutchens D. Sexuality and sexual activity in pregnancy. BJOG 2000;107:964-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb10397.x 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb10397.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lee JT. The meaning of sexual satisfaction in pregnant Taiwanese women. J. Midwifery Women's Health 2002;47:278-86. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/s1526-9523(02)00264-7 10.1016/s1526-9523(02)00264-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Spence SH. Psychosexual therapy: a cognitive-behavioural approach. London: Chapman & Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hyde JS, Delamater JD. Understanding human sexuality. 7th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bayrami R, Sattarzadeh N, Ranjbar Kooc F. Evalution of sexual behaviors and some of its related factors in pregnant women. J Urmia University Med Sci 2009;20:1-7. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Heydari M, Kiani Asiabar A, Faghih zade S. Couples’ knowledge and attitude about sexuality in pregnancy. Tehran Univ Med J 2006. 64:83-9. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Naim M, Bhutto E. Sexuality during pregnancy in Pakistan women. J Pak Med Assoc 2000;50:38-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Walbroehl G. Sexuality during pregnancy. Am Fam Physician 1984;29:273-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Masoomi S Z, Nejati B, Mortazavi A, Parsa P, Karami M. Investigating the effects of sexual consultation on marital satisfaction among the pregnant women coming to the health centers in the city of Malayer in the year 1394. Avicenna J Nurs Midwifery Care 2016;24:256-63. https://doi.org/10.21859/nmj-24046 10.21859/nmj-24046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ahmadi Z, Molaie Yarandi E, Malekzadegan A, Hosseini AF. Sexual Satisfaction and its Related Factors in Primigravidas. IJN 2011;24:54-62 [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ebrahimian A, Heydari MB, Saberi Zafarghandi MB. Comparison of female sexual dysfunctions before and during pregnancy. Iran J Obstet. Gynecol Infertil 2010;5:30-6. https://doi.org/10.22038/ijogi.2010.5826 10.22038/ijogi.2010.5826 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Nazari AM. Foundations and family therapy. Tehran: Elm; 2014, pp. 166-81. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rivas RE, Navío JF, Martínez MC, Miranda León MT, Castillo RF, Hernández OO. Modifications in Sexual Behaviour during Pregnancy and Postpartum: Related Factors. The West Indian medical journal 2016;10:326. https://doi.org/10.7727/wimj.2015.326 10.7727/wimj.2015.326 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Andrews G. Women’s sexual health. 3rd ed. London: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Babazadeh R, Najmabadi KM, Masomi Z. Changes in sexual desire and activity during pregnancy among women in Shahroud, Iran. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2013;120:82-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.07.021 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gałązka I, Drosdzol-Cop A, Naworska B, Czajkowska M, Skrzypulec-Plinta V. Changes in the sexual function during pregnancy. J Sex Med 2015;12:445-54. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/jsm.12747 10.1111/jsm.12747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Read J. Sexual problems associated with infertility, pregnancy, and ageing. BMJ 2004;329:559-61. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.329.7465.559 10.1136/bmj.329.7465.559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sossah L. Sexual behavior during pregnancy: a descriptive correlational study among pregnant women. European Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 2014;2:16-27. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yeniel AO, Petri E. Pregnancy, childbirth, and sexual function: perceptions and facts. Int Urogynecol J 2014;25:5-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-013-2118-7 10.1007/s00192-013-2118-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].de Pierrepont C, Polomeno V, Bouchard L, Reissing E. Que savons-nous sur la sexualité périnatale? Un examen de la portée sur la sexopérinatalité – partie 1 (What do we know about perinatal sexuality? A scoping review on sexoperinatality - part 1). J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2016;45:796-808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgyn.2016.06.003 10.1016/j.jgyn.2016.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Senkumwong N, Chaovisitsaree S, Rugpao S, Chandrawongse W, Yanunto S. The changes of sexuality in Thai women during pregnancy. J Med Assoc Thai 2006;89:124-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Fatehizadeh M, Mofid V, Ahmadi A, Etemadi O. The Comparison of Cognitive-Behavioral Counseling and Solution-Oriented Counseling on Women’s Sexual Satisfaction in Isfahan. Quarterly Journal of Women and Society 2014;5:67-83. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Barry WM, Emily M. Discovering Your Couple Sexual Style: Sharing Desire, Pleasure, and Satisfaction. In: chapter 3: Communicating your sexuality: the five dimensions of touch. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2009, pp. 21-31. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hudson WW, Harrison DF, Crosscup PC: A short-form scale to measure sexual discord in dyadic relationships. J Sex Res 1981;17:157-74. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120503 10.3390/bs12120503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Larson JH, Anderson SM, Holman TB, Niemann BK. A longitudinal study of the effects of premarital communication, relationship stability, and self-esteem on sexual satisfaction in the first year of marriage. J Sex Marital Ther 1998; 24:193-206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926239808404933 10.1080/00926239808404933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bahrami N, Yaghoobzadeh A, Sharif Nia H, Soleimani MA. Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of Larsons Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire in a Sample of Iranian Infertile Couples. Iranian Journal of Epidemiology 2016;12:18-31. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Afshar M, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Merghti-Khoei ES, Yavarikia P. The effect of sex education on the sexual function of women in the first half of pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. J Caring Sci 2012;22;1:173-81. https://doi.org/10.5681/jcs.2012.025 10.5681/jcs.2012.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bahadoran P, MohammadiMahdiabadzade M, Nasiri H, GholamiDehaghi A. The effect of face-to-face or group education during pregnancy on sexual function of couples in Isfahan. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 2015;20:582-7. https://doi.org/10.4103/1735-9066.164512 10.4103/1735-9066.164512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Shojaa M, Jouybari L, Sanagoo A. The sexual activity during pregnancy among a group of Iranian women. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2009;279:353-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-008-0735-z 10.1007/s00404-008-0735-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Sagiv-Reiss DM, Birnbaum GE, Safir MP. Changes in sexual experiences and relationship quality during pregnancy. Arch Sex Behav 2012;41:1241-51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9839-9 10.1007/s10508-011-9839-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Oche OM, Abdullahi Z, Tunau K, Ango JT, Yahaya M, Raji IA. Sexual activities of pregnant women attending antenatal clinic of a tertiary hospital in North-West Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J 2020;37:140. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2020.37.140.25471 10.11604/pamj.2020.37.140.25471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Corbacioglu Esmer A, Akca A, Akbayir O, Goksedef BP, Bakir VL. Female sexual function and associated factors during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2013;39:1165-72. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.12048 10.1111/jog.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Fok WY, Chan LY, Yuen PM. Sexual behavior and activity in Chinese pregnant women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2005;84:934-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00743.x 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00743.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Liu HL, Hsu P, Chen KH. Sexual activity during pregnancy in Taiwan: a qualitative study. Sex Med 2013;1:54-61. https://doi.org/10.1002/sm2.13 10.1002/sm2.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Riazi H, Banoo Zadeh S, Moghim Beig A, Amini L. Effects of sex education on beliefs of pregnant women to sexual activity during pregnancy. Payesh 2013;12;367-74. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Branecka-Woźniak D, Wójcik A, Błażejewska-Jaśkowiak J, Kurzawa R. Sexual and Life Satisfaction of Pregnant Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:5894. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165894 10.3390/ijerph17165894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Zacharis K, Chrysafopoulou E, Kravvaritis S, Charitos T, Fouka A. Changes in sexual experiences and sexual satisfaction during pregnancy: data from a Greek secondary hospital. The Pan African Medical Journal 2020;37:312. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2020.37.312.26813 10.11604/pamj.2020.37.312.26813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wannakosit S, Phupong V. Sexual behavior in pregnancy: comparing between sexual education group and nonsexual education group. The journal of sexual medicine 2010;7:3434-8. https://doi.org/org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01715.x 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01715.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Galinsky AM. Sexual touching and difficulties with sexual arousal and orgasm among US older adults. Arch Sex Behav 2012;41:875-90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9873-7 10.1007/s10508-011-9873-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ghasemi Moghadam K, Asgari A. Effectiveness of group education of marital enrichment program (Olson Style) on improvement of married womenâs satisfaction. Clinical Psychology and Personality 2013;11:1-10. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Johnson CE. Sexual health during pregnancy and the postpartum. J Sex Med 2011;8:1267-84; quiz 1285-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02223.x 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02223.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Serati M, Salvatore S, Siesto G, Cattoni E, Zanirato M, Khullar V, Cromi A, Ghezzi F, Bolis P. Female sexual function during pregnancy and after childbirth. J Sex Med 2010;7:2782-90.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01893.x 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01893.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]