Abstract

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common disease of the lungs known as the third reason for death worldwide. Frequent COPD exacerbations compel health care workers to apply interventions that are not adverse effect free. Accordingly, adding or replacing Curcumin, a natural meal flavoring, may indicate advantages in this era by its antiproliferative and anti‐inflammatory effects.

Methods

The PRISMA checklist was employed for the systematic review study. On June 3, 2022, PubMed/Medline, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched for studies associated with COPD and Curcumin in the last 10 years. Duplicate or non‐English publications and articles with irrelevant titles and abstracts were excluded. Also, preprints, reviews, short communications, editorials, letters to the editor, comments, conference abstracts, and conference papers were not included.

Results

Overall, 4288 publications were found eligible, after the screening, 9 articles were finally included. Among them, one, four, and four in vitro, in vivo, and both in vivo and in vitro research exist respectively. According to the investigations, Curcumin can inhibit alveolar epithelial thickness and proliferation, lessen the inflammatory response, remodel the airway, produce ROS, alleviate airway inflammation, hinder emphysema and prevent ischemic complications.

Conclusion

Consequently, the findings of the current review demonstrate that Curcumin's modulatory effects on oxidative stress, cell viability, and gene expression could be helpful in COPD management. However, for data confirmation, further randomized clinical trials are required.

Keywords: COPD, Curcumin, pulmonary disease, respiratory symptoms

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common disease of the lungs represented by irreversible airflow limitation. 1 COPD is known as the third reason of death in the world. 2 This respiratory disease caused 3.2 million death in 2015, which was 11.6% higher than the mortality rate of COPD patients in 1990. 3 The prevalence of COPD is estimated to be 15.7% and 10% in men and women, respectively. 4 Air particles and smoking are two major causes of COPD. 5 Air particles cause airway inflammation, reduce the defense of the antioxidant system against oxidants, and increase oxidative stress. 6 , 7 The pathophysiology of COPD is based on this inflammatory process and oxidative stress. 8 , 9

Exacerbation of COPD happens frequently and causes morbidity and mortality. Exacerbation of COPD is featured by symptoms like cough, sputum production, and dyspnea. 10 Clinical guidelines for preventing exacerbation and treating COPD include using pharmacological treatment and changing lifestyle by stopping smoking. Pharmacological treatments such as bronchodilators and corticosteroids can be used. 11

These drugs have some adverse effects, including tremors, osteoporosis and fractures, electrolyte disturbances, increased heart rates, and cardiac effects. 12 , 13 Thus, adding some new agents to these pharmacological treatments or replacing a new agent with a different mechanism, such as alleviating oxidative stress, may be effective in treating COPD. Studies have shown that natural compounds positively treat and prevent diseases like Alzheimer's, osteoarthritis and inflammatory bowel disease. 14 , 15 , 16

Curcumin is a traditional food additive typically used in Asian foods. 17 Curcumin is component of the spice turmeric with phenolic structure. 18 Curcumin has antiproliferative and anti‐inflammatory effects by downregulating pro‐inflammatory cytokines. 19 , 20 Besides, Curcumin accelerates the transcription of genes which helps the expression of the antioxidant system by reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and leading to an increase in the antioxidant defense system. 21 Despite existing studies about the effects of Curcumin on many diseases, all effects of Curcumin on COPD are not clear. 22 Thus, this study aims to review the therapeutic effects of Curcumin in in vitro and in vivo studies on COPD to provide clinical evidence for the treating COPD patients.

2. METHODS

The PRISMA checklist served as the basis for the current systematic review investigation. With attention to this point that most of medical papers can be found in PubMed/Medline, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google scholar, we searched in these data basses based on the plausible keywords in accordance with the aim of this study for any study associated with COPD and Curcumin on June 3, 2022 by two independent authors. Additionally, by reviewing the references of refrences to discover potential eligible articles the findings of the systematic search were finalized. The Mendeley program was used to import the systematic search results. We considered the 10‐year time limit for search, so we only reviewed articles from 2012 to June 2022. The employed keywords are brought in the Supporting Information: Table 1.

The inclusion criteria were all the relevant English research from 2012 to June 2022 with full‐text access. The articles were excluded by following criteria: Non‐English studies and preprints, reviews articles, short coomuniations, editorials, letters to the editor, comments, conference abstracts, conference papers.

First, duplicate articles from the selection procedure for the study were eliminated. Then the articles were screened and the papers that met the exclusion criteria were excluded from the study. In a two‐step process that involved screening the title and abstract, two reviewers independently examined the retrieved studies and chose the appropriate publications. The same two reviewers examined the entire texts of the research that had passed screening during the full‐text evaluation stage, and the finished papers were included. Discussion between the two reviewers helped to settle the differences in their assessments of the title/abstract and entire text.

We used SYRCLE's tool for assessing risk of bias for in vivo studies to evaluate the risk of bias in the included studies.

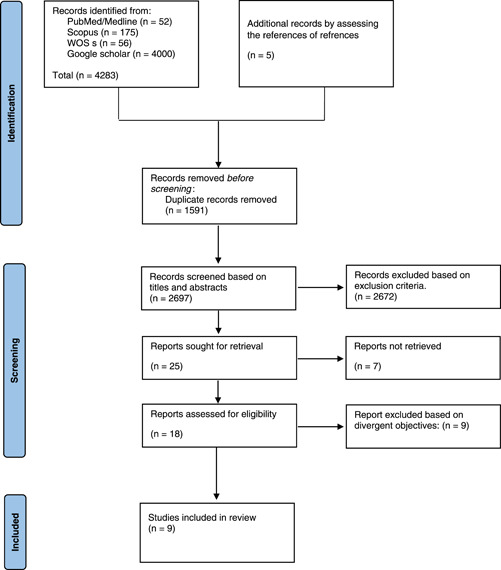

Each criterion was answered with “Yes,” “No,” or “unclear.” A “yes” decision indicates a low risk of bias, a “no” decision shows a high risk of bias, and the decision will be “unclear” if not enough information has been provided to correctly assess the risk of bias. After determining the answer to each question, each study was scored as good, fair, or poor. According to the SYRCLE's tool, two reviewers independently assessed the articles that were included. Discrepancies were resolved by a third expert reviewer (Figure 1). We did not perform quality assessment for in vitro studies because there is no appropriate checklist for this type of studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

After carefully reading the complete texts of the remaining papers, which were chosen using the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the research, and after assessing the quality of them, the necessary data were retrieved.

Two independent reviewers collected data from eligible articles, and a third one revised the data.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search results

The number of published studies identified by PubMed Advanced Search Builder on (((((((((COPD) OR (“chronic obstructive pulmonary disease”)) OR (“Chronic Obstructive Airway Disease”)) OR (“Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease”)) OR (“Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease”)) OR (“Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases”)) OR (“Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease”)) OR (“COAD”))) AND ((((((“Curcumin”) OR (Mervia)) OR (“Diferuloylmethane”)) OR (“Curcumin Phytosome”)) OR (“Turmeric Yellow”)) OR (CURCUMA longa)) was 52. The number of papers through the Scopus Advanced Search database was 175. There were 56 articles achieved through the Web of Science, Google Scholar retrieved 4000 publications and 5 articles were obtained by assessing the refrences of refrences.

3.2. Included studies and summary results

After screening the records, the total number of articles was 4288, of which 1591 were duplicates. The language of 270 studies was not English. There were 462 letters, review articles, and communications. In the second screening stage, 1940 articles were excluded from our analysis due to their irrelevant subjects. Searching subjects and abstracts of the studies, 25 papers were included in the study. In the third step of screening, by studying full texts of the articles and based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, 10 papers passed the eligibility requirements and were included in this review study.

Among these 10 publications, one was a randomized clinical trial (RCT), 23 which was removed. Eventually, nine papers met the inclusion criteria in our systematic review, one was in vitro investigations, 24 four both in vivo and in vitro research, 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 and four were in vivo studies. 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 Only males participated in eight investigations, 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 and gender was not mentioned in one research. 24 Humans and human tissues were utilized in one investigation, 23 , 24 and Sprague‐Dawley, mice, and rats were used in seven studies. 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 The target population of all studies were exposed to smoking for a specific period.

To evaluate the effect of Curcumin on COPD, all groups received treatment with Curcumin at predetermined doses for a varying amount of time, ranging from 4 h to 16 weeks.

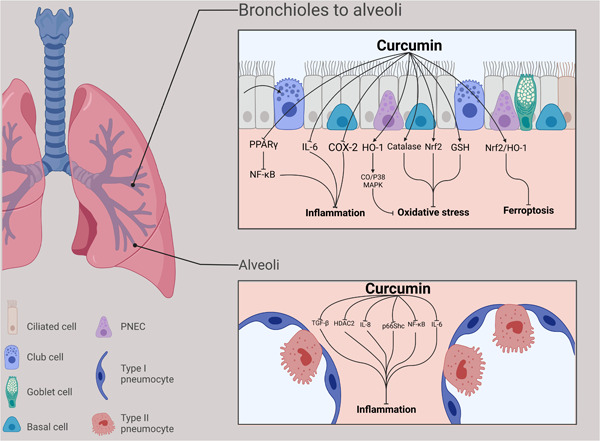

According to the results of studies, Curcumin offers several benefits including inhibition of alveolar epithelial thickness and proliferation, 28 , 30 diminution of inflammatory response, 24 airway remodeling, and ROS production. 24

Curcumin reduces airway inflammation by suppressing LPC and CS‐induced COX‐2 expression as well as by modifying HDAC2 activity. Additionally, Curcumin suppresses the production of IL‐6,8, TGF beta, NF‐kappa B, COX‐2, NF‐κB, 28 , 30 adapter protein p66Shc, 30 and TNF‐α. It also prevents H3/H4 acetylation and H3K9 dimethylation. According to the findings, Curcumin impedes cell apoptosis 30 and modulates HDAC2 activity. 26

Curcumin facilitates autophagy 24 and inhibits endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) by enhanced expression of NAD‐dependent protein deacetylase sirtuin‐1 (SIRT1), LC3‐I, LC3‐II, and Beclin1and downregulation of C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) and GRP78. 31

By amplifying the expression of antioxidant heme oxygenase‐1 (HO‐1), nuclear factor E2, and nuclear‐related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway, Curcumin reduces ferroptosis. 24 , 27 , 29

Curcumin alleviates mitochondrial dysfunction of skeletal muscle and upregulates the Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐gamma coactivator 1‐α (PGC‐1α)/silent mating‐type information regulation 2 homolog 3 (SIRT3) signaling pathway. 32 Furthermore, it promotes the production of CO/P38 MAPK 27 and increases GSH regeneration. 24

Studies revealed that Curcumin can restrict emphysema 30 and prevent ischemic complications by lowering α1‐Antitrypsin–low‐density lipoprotein (AT‐LDL) in patients with mild to moderate COPD.

Curcumin notably relieves inflammation by inhibition of NF‐κB which was induced by CS‐extraction. Curcumin also significantly inhibited CS‐induced infiltration of inflammatory cells in the parenchyma and airway, and it also inhibited CS‐induced secretions of IL‐6 and TNF‐α in both the serum and BALF. 25

Based on the studies and data extraction complied in the Table 1, in reducing and improving the symptoms of COPD, Curcumin functions through a variety of signaling pathways, the most significant of which are PGC‐1α/SIRT3, p66Shc, and NF‐κB (Figure 2). 28 , 30 , 32

Table 1.

Articles included in this study in details.

| Authors | Date of study (year and month) | Type of study | Number of population/respondents/participants (n) | Age group | Gender identity/sexual orientation | Race/ethnicity | Country/city | curcumin (mean)/dose | Treatment duration/follow‐up period days | severity of COPD | gene | FEV1 before/after | signaling/molecular pathway | Fev1/FVC | Smoking | outcomes/author's conclusions | adverse effect adverse events | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gan et al. 26 | November 2016 | In vitro and in vivo | 32 SPF grade Sprague‐Dawley rats, control=16, COPD = 16 | 6‐week‐old | Male | ‐ | China | 100 µM | 24 h | ‐ | HDAC2, IL‐8, MCP‐1, and MIP‐2α | ‐ | ‐ | COPD model: Inhale 15 min per cigarette and 10 cigarettes each day for 90 days | Curcumin reduces inflammation by modifying HDAC2 function | ‐ | |

| 2 | Huang et al. 27 | August 2019 | In vitro and in vivo | 28 SPF‐grade Kunming mice (control=6, normal saline control = 6, PM2.5 = 8, curcumin = 8) | ‐ | Male | ‐ | China | 100 mg/kg | 7 days | ‐ | ‐ | HO‐1/CO/P38 MAPK | ‐ | ‐ | Curcumin can boost the production of the antioxidant HO‐1 and its subsequent product CO/P38 MAPK | ‐ | |

| 3 | Reis et al. 24 | September 2021 | Human BronchialEpithelialCell LineBEAS‐2B | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | turkey | 5–20 µM | 4 h | ‐ | ROS, CAT, IL‐6, GSH, NRF2 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 3R4F reference cigarette extract (CSE) | Curcumin reduces CSE‐induced cell autophagy, ROS production, IL‐6 and lung inflammation. Additionally, it increases the nuclear translocation of Nrf2, Catalase activity restoration, and GSH restoration. | ‐ |

| 4 | Yuan et al. 28 | October 2018 | In vitro and in vivo | 70 LC‐induced COPD mice and BEAS‐2B cell | 6–8 weeks | Male | ‐ | China | 100–200 mg/kg days | 10 days | ‐ | IL‐6, TGF beta, NF‐kappa B, COX‐2, IκBα | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 5 min cigarette smoke per exposure once a day for 35 days | Curcumin suppresses IL‐6, TGF beta, NF‐kappa B, COX‐2, IκBα, alveolar epithelial thickness and proliferation | ‐ |

| 5 | Zhang et al. 30 | November 2016 | In vivo | 38 Sprague‐Dawley rats | ‐ | Male | ‐ | China | 100 mg/kg | 60 days | ‐ | IL‐6, IL‐8, TNF‐α, and p66Shc | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Twice a day for 60 days | Curcumin suppresses emphysema and ultrastructural damage of alveolar epithelial cells. additionally, it inhibits the production of IL‐6,8, TNF‐α, p66Shc, and poptosis. | ‐ |

| 6 | Tang et a. 31 | October 2019 | In vivo | 135 Sprague–Dawley rats | ‐ | Male | ‐ | China | 100–200 mg/kg | 28 days | ‐ | SIRT1, LC3‐I, LC3‐II, Beclin1, CHOP and GRP78 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 20 cigarettes in a 1‐m3 closed glass box for 30 min/day for 4 weeks | Curcumin lowers the expression of CHOP, GRP78, and autophagy. It enhances the expression of SIRT1, LC3‐I, LC3‐II, and Beclin1. | ‐ |

| 7 | Zhang et al. 32 | September 2017 | In vivo | 38 Sprague‐Dawley | ‐ | Male | ‐ | China/Xi'an | 100 mg/kg | 60 days | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | PGC‐1α/SIRT3 signaling pathway | ‐ | 30 min per exposure, twice a day, for all days of the study except day 1 and 15. | Curcumin improves mitochondrial dysfunction of skeletal muscle and activates the PGC‐1α/SIRT3 signaling pathway | ‐ |

| 8 | Tang et al. 29 | November 2021 | In vivo | 20 Sprague‐Dawley | 7‐week‐old | Male | ‐ | China/Tianjin | 100 mg/kg/day | 16 weeks | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 30 min per exposure, twice a day, and 6 days a week for 16 weeks | Curcumin decreases ferroptosis through triggering the nuclear factor E2 related factor 2 (Nrf2)/heme oxygenase‐1 (HO‐1) signaling network. | ‐ |

| 9 | Li et al. 25 | November 2021 | In vitro and in vivo | 32 Sprague‐Dawley | 6‐week‐old | Male | ‐ | China | 100 mg/kg/day | 6 months | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | PPARγ‐NF‐κB signaling pathway | ‐ | 1 h per day, 6 days per week for 6 months. | Curcumin offers therapeutic effects for COPD by decreasing airway inflammation. furthermore, suppresses NF‐κB through modifying PPARγ‐NF‐κB signaling cascade. | ‐ |

Abbreviations: CHOP, C/EBP homologous protein; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Figure 2.

Curcumin's effects on signaling pathways.

4. DISCUSSION

There are a limited number of studies that investigate the effectiveness of Curcumin in COPD. Reviewed studies show improvement in COPD samples that received Curcumin supplements. Most studies suggest decreasing airway inflammation as the reason for the alleviation effect of Curcumin. The results demonstrate several different mechanisms and signaling pathways for this effect. These results investigate not only the alleviation of airway inflammation but also comorbidities.

Skeletal muscle impairment is another extrapulmonary complication in COPD patients. This complication is caused by oxidative stress, energy metabolism disorders and, systemic inflammation. This complication could lead to muscle atrophy, which starts with exercise intolerance. There isn't still an efficient treatment for this muscle dysfunction. 33 According to Zhang et al. 32 Curcumin significantly upregulates the expression of PGC‐1α and SIRT3, which contribute to the regulation of mitochondrial fatty‐acid oxidation and mitochondrial metabolism, respectively. 32 , 34 Subsequently, Curcumin improves skeletal muscles function in COPD patients by improving mitochondrial function, attenuating energy metabolism disorders and oxidative stress.

Regular smoking, the primary cause of COPD, attracts lymphocytes and neutrophils to the airways. Neutrophils attraction in turn provokes the release of inflammatory cytokines such as TGF‐β and IL‐6. These cytokines provoke a tissue remolding and inflammatory response which are responsible for airway limitation in COPD. CS contains free radicals, LPS, and superoxide radicals. Inhalation of these particles is associated with NF‐κB signaling pathway. Evidence has shown that NF‐κB contributes to the airway remodeling processes of COPD. 35 It is involved in the transcription of several inflammatory mediators. 36 Previous studies have reported that Curcumin could have an inhibitory effect on COX‐2 expression and NF‐κB pathway in asthmatic rats. 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 Yuan et al. 28 have shown this inhibitory effect in COPD models. Histopathological data from this study has confirmed the significant impact of Curcumin in the alleviation of airway remolding and airway inflammation. This improvement in airway condition could be responsible for the downregulation of COX‐2 expression and NF‐κB pathway by Curcumin. 28

Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) could contribute to the inflammatory responses of COPD as a nuclear receptor. 41 Evidence has shown that the expression of PPARγ is associated with less severity of COPD. 42 PPARγ reduces the expressions of the activation of inflammatory cells and pro‐inflammatory genes through inhibition of NF‐κB. 41 Curcumin plays its therapeutic role in COPD by reducing airway inflammation through inhibiting NF‐κB via modulating PPARγ‐NF‐κB signaling. 25 Histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) is another factor that inhibits the expression of the pro‐inflammatory genes via deacetylation of core histones. 43 The level of HDAC2 decreases in type II alveolar epithelial cells in COPD. Curcumin could reverse the decreased level of HDAC2 and increased level of IL‐8, monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1, and macrophage inflammatory protein‐2α in the COPD models. They also have revealed that CS inhibited H3K9 dimethylation, but induced H3/H4 acetylation. CS prompted mRNA expression of IL‐8 and Curcumin significantly blocked these effects of CS on the expression of IL‐8. 26

Adapter protein p66Shc is an important part of response signals to oxidative stress. 44 P66Shc contributes to the injury of human cells such as hepatocytes, renal tubular epithelial cells, and cardiomyocytes under pathological conditions. 32 P66Shc phosphorylation can be induced during oxidative stress. This phosphorylation promotes the binding of p66Shc and cytochrome C inside mitochondria. 44 This binding is responsible for the releasing of ROS by diverting oxidized cytochrome C within mitochondria. Eventually, the transition pore of mitochondria opens and leads to mitochondrial injury. 44 In another study, Zhang et al. 30 have shown that the protein expression of p66Shc was significantly elevated in alveolar cells of COPD rats. They have demonstrated that Curcumin downregulates the expression of p66Shc in the epithelia of COPD rats, suggesting the therapeutic effect of Curcumin on injured alveolar epithelial via the inhibition of p66Shc signaling. 30

Autophagy is an necessary process that eliminates damaged cellular components and there are more senescence cells in COPD when there is insufficient autophagy. 45 The SIRT1, as a critical mediator of the various process including oxidative stress and apoptosis, could significantly affect autophagy. 46 Increased expression of SIRT1 activates autophagy and subsequent elimination of damaged CS‐induced human bronchial epithelial cells. Treatment with Curcumin increased SIRT1 activation which in turn increased autophagy. 31 Ferroptosis, a novel and nonapoptotic type of regulated cell death, is associated with injury of lung cells in COPD. Ferroptosis is accompanied by increasing lipid peroxidation, accumulation of lipid‐ROS, intracellular iron overload and glutathione (GSH) depletion. 47 The results suggested that CS extract could trigger ferroptosis‐related changes in BEAS‐2B cells. Curcumin alleviates the ferroptotic characteristic changes in COPD. Subsequently, Curcumin improved inflammatory response and lung injury caused by CS in COPD. 29

ERS is accompanied by protein modification, handling, folding, and subsequent accumulation of misfolded proteins within the endoplasmic reticulum. The unfolded protein response (UPR) is a signaling pathway which induced by ERS and maintains ER homeostasis. 48 Evidence has considered elevated ERS as potential pathophysiology of COPD. It is associated with upregulation in the expression of the CHOP and GRP78 which are ERS‐associated markers. 49 Tang et al. 31 have demonstrated that these two markers are elevated in COPD models and may be inhibited by SIRT1 which is a response to ERS. They have revealed that treatment with Curcumin significantly reduced CHOP and GRP78 via SIRT1 activation. 31

The need for novel and safe treatment for COPD is increasing in recent years. However, guidelines have suggested known drugs for the treatment of this chronic disease, these drugs have many side effects and reports of drug resistance. On the other hand, Curcumin is generally known as a safe food additive. 50 Its side effects are found yellow stool, rash, diarrhea, and headache 51 and no serious adverse effect is mentioned for Curcumin in therapeutic doses. Thus, Curcumin could be a suitable alternative or additive treatment for patients with COPD. Besides, various studies demonstrated that the dual effect of Curcumin on the COPD process depending on its therapeutic dosage. These data show that a low dose of Curcumin has a protective effect on the cell viability against CSE while an increased amount of it has a reverse effect on cell viability. 24 Curcumin poor absorption leads to rapid elimination which in turn causes poor bioavailability of Curcumin as one of the usage limitations. There are some formulations for improving its bioavailability; for example, the combination of Curcumin with piperine was associated with a 2000% improvement in Curcumin bioavailability. 52 , 53

The current systematic review has investigated studies about the efficacy of Curcumin on patients with COPD, however, as a limitation, there was a lack of sufficient numbers of randomized clinical trials (RCT). Short treatment duration, different dosages of Curcumin, and small sample size were some of the other limitations which can be the reason of different outcomes reported in reviewed research.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, there is a need for the novel COPD therapy because of the current drugs' limitations. The findings of our study suggest that Curcumin might be potentially a beneficial food additive and could be effective in treating COPD for alternation or addition to previous pharmacological managements. It has been demonstrated that this impact is related to Curcumin's modulatory effects on oxidative stress, cell viability, and inflammation, though further RCTs are required to confirm our results.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Saeid Safari: Conceptualization; data curation; supervision; validation. Poorya Davoodi: Conceptualization; methodology; supervision; validation. Afsaneh Soltani: Formal analysis; software; writing—original draft. Mohammadreza Fadavipour: Investigation; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing. AhmadReza Rezaeian: Data curation; investigation; writing—review & editing. Fateme Heydari: Project administration; resources; writing—original draft. Mohammad Amin Khazeei Tabari: Project administration; software; visualization. Meisam Akhlaghdoust: Conceptualization; resources; supervision; validation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

TRANSPARENCY STATEMENT

The lead author Meisam Akhlaghdoust affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Supporting information

Supplementary information.

Safari S, Davoodi P, Soltani A, et al. Curcumin effects on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:e1145. 10.1002/hsr2.1145

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Patel AR, Patel AR, Singh S, Singh S, Khawaja I. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease: the changes made. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095‐2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Soriano JB, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability‐adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990‐2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(9):691‐706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Varmaghani M, Dehghani M, Heidari E, Sharifi F, Saeedi Moghaddam S, Farzadfar F. Global prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta‐analysis. East Mediterr Health J. 2019;25(1):47‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vestbo J. COPD. Clin Chest Med. 2014;35(1):1‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhao J, Pu J, Hao B, et al. LncRNA RP11‐86H7. 1 promotes airway inflammation induced by TRAPM2. 5 by acting as a ceRNA of miRNA‐9‐5p to regulate NFKB1 in HBECS. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zinellu E, Zinellu A, Fois AG, et al. Reliability and usefulness of different biomarkers of oxidative stress in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Oxid Med Cell Longevity. 2020;2020:1‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zuo L, Wijegunawardana D. Redox role of ROS and inflammation in pulmonary diseases. Lung Inflamm Health Dis. 2021;II:187‐204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kirkham PA, Barnes PJ. Oxidative stress in COPD. Chest. 2013;144(1):266‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ko FW, Chan KP, Hui DS, et al. Acute exacerbation of COPD. Respirology. 2016;21(7):1152‐1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kwon C‐Y, Lee B, Lee B‐J, Kim K‐I, Jung H‐J, eds. Comparative effectiveness of western and eastern manual therapies for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Healthcare. MDPI; 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gupta P, O'mahony MS. Potential adverse effects of bronchodilators in the treatment of airways obstruction in older people. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(5):415‐443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barnes BJ, Hollands JM. Drug‐induced arrhythmias. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:S188‐S197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Samadi F, Kahrizi MS, Heydari F, et al. Quercetin and osteoarthritis: a mechanistic review on the present documents. Pharmacology. 2022;107:464‐471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lashgari NA, Momeni Roudsari N, Khayatan D, et al. Ginger and its constituents: role in treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Biofactors. 2022;48(1):7‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Seibel R, Schneider RH, Gottlieb MGV. Effects of spices (saffron, rosemary, cinnamon, turmeric and ginger) in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2021;18(4):347‐357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ng TP, Niti M, Yap KB, Tan WC. Curcumins‐rich curry diet and pulmonary function in Asian older adults. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang Y, Rauf Khan A, Fu M, et al. Advances in curcumin‐loaded nanopreparations: improving bioavailability and overcoming inherent drawbacks. J Drug Target. 2019;27(9):917‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mollazadeh H, Cicero AFG, Blesso CN, Pirro M, Majeed M, Sahebkar A. Immune modulation by curcumin: the role of interleukin‐10. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59(1):89‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aggarwal BB, Sung B. Pharmacological basis for the role of curcumin in chronic diseases: an age‐old spice with modern targets. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30(2):85‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Trujillo J, Chirino YI, Molina‐Jijón E, Andérica‐Romero AC, Tapia E, Pedraza‐Chaverrí J. Renoprotective effect of the antioxidant curcumin: recent findings. Redox Biol. 2013;1(1):448‐456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ashrafizadeh M, Ahmadi Z, Mohamamdinejad R, et al. Curcumin therapeutic modulation of the wnt signaling pathway. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2020;21(11):1006‐1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morimoto T, Funamoto M, Sunagawa Y, et al. Highly absorptive curcumin reduces serum atherosclerotic low‐density lipoprotein levels in patients with mild COPD. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulm Dis. 2016;11:2029‐2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reis R, Orak D, Yilmaz D, Cimen H, Sipahi H. Modulation of cigarette smoke extract‐induced human bronchial epithelial damage by eucalyptol and curcumin. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2021;40(9):1445‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li Q, Sun J, Mohammadtursun N, Wu J, Dong J, Li L. Curcumin inhibits cigarette smoke‐induced inflammation via modulating the PPARγ‐NF‐κB signaling pathway. Food Funct. 2019;10(12):7983‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gan X, Li C, Wang J, Guo X. Curcumin modulates the effect of histone modification on the expression of chemokines by type II alveolar epithelial cells in a rat COPD model. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulm Dis. 2016;11:2765‐2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huang K, Shi C, Min J, et al. Study on the mechanism of curcumin regulating lung injury induced by outdoor fine particulate matter (PM2. 5). Mediators Inflamm. 2019;2019:1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yuan J, Liu R, Ma Y, Zhang Z, Xie Z. Curcumin attenuates airway inflammation and airway remolding by inhibiting NF‐κB signaling and COX‐2 in cigarette smoke‐induced COPD mice. Inflammation. 2018;41(5):1804‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tang X, Li Z, Yu Z, et al. Effect of curcumin on lung epithelial injury and ferroptosis induced by cigarette smoke. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2021;40(suppl 12):753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang M, Xie Y, Yan R, et al. Curcumin ameliorates alveolar epithelial injury in a rat model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Life Sci. 2016;164:1‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tang F, Ling C. Curcumin ameliorates chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by modulating autophagy and endoplasmic reticulum stress through regulation of SIRT1 in a rat model. J Int Med Res. 2019;47(10):4764‐74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang M, Tang J, Li Y, et al. Curcumin attenuates skeletal muscle mitochondrial impairment in COPD rats: PGC‐1α/SIRT3 pathway involved. Chem biol interact. 2017;277:168‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bernard S, LeBlanc P, Whittom F, et al. Peripheral muscle weakness in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(2):629‐634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Goetzman E, et al. SIRT3 regulates mitochondrial fatty‐acid oxidation by reversible enzyme deacetylation. Nature. 2010;464(7285):121‐125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Di Stefano A, Caramori G, Oates T, et al. Increased expression of nuclear factor‐κB in bronchial biopsies from smokers and patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2002;20(3):556‐563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Al‐Harbi NO, Imam F, Al‐Harbi MM, et al. Dexamethasone attenuates LPS‐induced acute lung injury through inhibition of NF‐κB, COX‐2, and pro‐inflammatory mediators. Immunol Invest. 2016;45(4):349‐369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fan Z, Jing H, Yao J, et al. The protective effects of curcumin on experimental acute liver lesion induced by intestinal ischemia‐reperfusion through inhibiting the pathway of NF‐κB in a rat model. Oxid Med Cell Longevity. 2014;2014:1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ni H, Jin W, Zhu T, et al. Curcumin modulates TLR4/NF‐κB inflammatory signaling pathway following traumatic spinal cord injury in rats. J Spinal Cord Med. 2015;38(2):199‐206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang J, Ma J, Gu JH, et al. Regulation of type II collagen, matrix metalloproteinase‐13 and cell proliferation by interleukin‐1β is mediated by curcumin via inhibition of NF‐κB signaling in rat chondrocytes. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16(2):1837‐45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sharafkhaneh A, Velamuri S, Badmaev V, Lan C, Hanania N. Review: the potential role of natural agents in treatment of airway inflammation. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2007;1(2):105‐120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Belvisi MG, Mitchell JA. Targeting PPAR receptors in the airway for the treatment of inflammatory lung disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(4):994‐1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lea S, Plumb J, Metcalfe H, et al. The effect of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐γ ligands on in vitro and in vivo models of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(2):409‐420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Barnes PJ. Histone acetylation and deacetylation: importance in inflammatory lung diseases. Eur Respir J. 2005;25(3):552‐563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Orsini F, et al. Electron transfer between cytochrome c and p66Shc generates reactive oxygen species that trigger mitochondrial apoptosis. Cell. 2005;122(2):221‐233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Takasaka N, Araya J, Hara H, et al. Autophagy induction by SIRT6 through attenuation of insulin‐like growth factor signaling is involved in the regulation of human bronchial epithelial cell senescence. J Immun. 2014;192(3):958‐968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chung S, Yao H, Caito S, Hwang J, Arunachalam G, Rahman I. Regulation of SIRT1 in cellular functions: role of polyphenols. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;501(1):79‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Koskenkorva‐Frank TS, Weiss G, Koppenol WH, Burckhardt S. The complex interplay of iron metabolism, reactive oxygen species, and reactive nitrogen species: insights into the potential of various iron therapies to induce oxidative and nitrosative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;65:1174‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Oakes SA, Papa FR. The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in human pathology. Annu Rev Pathol: Mech Dis. 2015;10:173‐194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Aksoy M, Ji R, Katamreddy SR, et al. The unfolded protein response (UPR) to heightened endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is impaired in the COPD lung. C22 Pathobiology of COPD: lessons from inflammatory mechanisms and genomic studies. Am Thorac Soc. 2011;183:A4094. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kocaadam B, Şanlier N. Curcumin, an active component of turmeric (CURCUMA longa), and its effects on health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57(13):2889‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lao CD, Ruffin MT, Normolle D, et al. Dose escalation of a curcuminoid formulation. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Miryan M, Soleimani D, Askari G, et al. Curcumin and piperine in COVID‐19: a promising duo to the rescue? Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1327:197‐204. 10.1007/978-3-030-71697-4_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shoba G, Joy D, Joseph T, Majeed M, Rajendran R, Srinivas P. Influence of piperine on the pharmacokinetics of curcumin in animals and human volunteers. Planta Med. 1998;64(04):353‐356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Komiyama M, Wada H, Ura S, et al. The effects of weight gain after smoking cessation on atherogenic α1‐antitrypsin–low‐density lipoprotein. Heart Vessels. 2015;30(6):734‐739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.