Abstract

Background

Abiotic stresses, particularly drought and heavy metal toxicity, have presented a significant risk to long-term agricultural output around the world. Although the heavy-metal-associated domain (HMA) gene family has been widely explored in Arabidopsis and other plants, it has not been thoroughly studied in wheat (Triticum aestivum). This study was proposed to investigate the HMA gene family in wheat.

Methods

To analyze the phylogenetic relationships, gene structure, gene ontology, and conserved motifs, a comparative study of wheat HMA genes with the Arabidopsis genome was performed.

Results

A total of 27 T. aestivum proteins belonging to the HMA gene family were identified in this study, with amino acid counts ranging from 262 to 1,071. HMA proteins were found to be grouped into three subgroups in a phylogenetic tree, and closely related proteins in the tree showed the same expression patterns as motifs found in distinct subgroups. Gene structural study elucidated that intron and exon arrangement differed by family.

Conclusion

As a result, the current work offered important information regarding HMA family genes in the T. aestivum genome, which will be valuable in understanding their putative functions in other wheat species.

Keywords: Bioinformatics, Genome-wide analysis, Heavy metal toxicity, HMA gene family, Phylogenetic analysis

Introduction

Wheat (T. aestivum L.), a major food crop worldwide, is cultivated on nearly 20% of agricultural land and serves as a significant source of food for 30% of the world’s population (Vasil, 2007). The global wheat output (growth and yield) is adversely influenced by environmental stresses such as water scarcity and toxic metals, etc. (Javed et al., 2016). Plants have evolved a variety of adaptation strategies, to protect themselves from harsh environmental conditions (Raza et al., 2019). Plant biologists have long been fascinated by the regulation and expression of many genes for improved crop resilience to biotic and abiotic stresses, along with increased productivity. Drought and heavy metal toxicity are among the abiotic stresses that have posed a severe threat to crop yield globally (Bari et al., 2018). Drought is one of the most common stresses in heavy metal contaminated environments (Barceló & Poschenrieder, 2004) and causes a variety of biochemical and physiological changes in plants (Zahra et al., 2021a). Heavy metal accumulation and transportation to grain has a detrimental effect on human health as well. Therefore, it is pivotal to understand the mechanism of metal accumulation and transport in the grain to mitigate this phenomenon (Ahmad et al., 2018).

Plants selectively sense environmental stimuli and resultantly activate signaling cascades to assemble an overall response for their survival, which is mediated by complex signaling networks (Cappetta et al., 2020). Heavy metal associated (HMA) protein, familiar as P1B-ATPase, participates in absorbing and transporting heavy metal ions (Cu2+, Co2+, Zn2+, Pb2+ and Cd2+) by combining ATP hydrolysis with metal ion transport across membranes (Imran et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2021). Currently, the number of identified HMA genes are eight in A. thaliana, nine in rice (Oryza sativa L.), 11 in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.), 11 in maize (Zea mays L.), 20 in soybean (Glycine max L.), 17 in Populus trichocarpa and 21 in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) (Zhang et al., 2021). HMA domain genes are vital for the spatiotemporal transit of metal ions that bind to several enzymes and cofactors throughout the cell (He et al., 2020). It is worth noting that HMA affects not only heavy metal transport but also plant growth and development (Grispen et al., 2011).

Wheat is sensitive to heavy metals. Heavy metals trigger different responses in wheat, leading to yield losses in wheat (Rizvi et al., 2020). However, data regarding this gene family in hexaploid wheat is scanty. Limited similarities have been found in the mechanisms of both drought and heavy metal tolerance strategies in plants (Islam & Sandhi, 2022). Signaling pathways activate proteins that make transporters, proteases, ROS detoxifying enzymes (alternative oxidase, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, copper-zinc superoxide dismutase, glutathione S transferase and chaperones (Zhang & Sonnewald, 2017)), which help plants to ameliorate stress. Under abiotic and biotic stress, the molecular processes and signal transduction pathways of the HMA family of genes, their function in shielding plants from pathogens and environmental stresses are currently poorly known. However, abiotic stress is intimately linked to the HMA gene family (He et al., 2020). In a previous study, the expression of the yeast AcHMA1 gene improved yeast cell’s resilience to stresses such as drought, alkali, salt, and oxygen (Sun et al., 2014).

Several HMA genes were found to play different roles in various species of plants, as OsHMA2 is linked to zinc loading in vascular tissue and tonoplast localization in rice (Yamaji et al., 2013). OsHMA3, which is found in tonoplasts, transports Cd to the roots, whereas OsHMA4 transports copper (Huang et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2021). HvHMA1 aids in the transfer of zinc and cadmium into barley grain (Mikkelsen et al., 2012). There are evidences that HMAs play a vital role in heavy metal transmembrane trafficking. However, little is known about HMAs in wheat. This study reports a complete identification of HMA genes in wheat including syntenic examination, gene structures analysis, and conserved motif analysis. This study may lay the foundation for further investigate the putative functions of the HMA gene family in wheat.

Materials and Methods

Retrieval of protein sequences

HMA protein sequences of Arabidopsis (Table 1) and wheat (Table 2) were retrieved from the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). These sequences were further verified from The Arabidopsis Information Resources (TAIR) (http://www.arabidopsis.org/index.jsp) while the Phytozome database of wheat (T. aestivum) was used to confirm these proteins in wheat using online server (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/).

Table 1. Physio-chemical property of heavy metal associated (HMA) proteins in Arabidopsis.

| S. No. | Gene name | Transcript name | Gene ID | Translation length (a.a) | Protein accession no. | Chr. | Subcellular location | Strand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | HMA1 | AT4G37270.1 | 19648322 | 819 | NP_195444.1 | 4 | Plasma membrane | Reverse |

| 2. | HMA2 | AT4G30110.1 | 19643720 | 951 | NP_001320088.1 | 4 | Plasma membrane | Reverse |

| 3. | HMA3 | AT4G30120.1 | 19645860 | 542 | NP_001328455.1 | 4 | Plasma membrane | Reverse |

| 4. | HMA4 | AT2G19110.1 | 19641614 | 1,172 | NP_179501.1 | 2 | Plasma membrane | Forward |

| 5. | HMA5 | AT1G63440.1 | 19650287 | 995 | NP_176533.1 | 1 | Chloroplast | Forward |

| 6. | HMA6.1 | AT4G33520.2 | 19645604 | 949 | NP_974675.1 | 4 | Chloroplast | Forward |

| 7. | HMA6.2 | AT4G33520.3 | 19645605 | 949 | NP_974676.1 | 4 | Plasma membrane | Forward |

| 8. | HMA7 | AT5G44790.1 | 19665355 | 1,001 | NP_199292.1 | 5 | Chloroplast | Reverse |

| 9. | HMA8 | AT5G21930.1 | 19665627 | 883 | NP_001237371.2 | 5 | Chloroplast | Forward |

| 10. | HMA8.2 | AT5G21930.2 | 19665628 | 883 | NP_001031920.1 | 5 | Plasma membrane | Forward |

Table 2. Physio-chemical properties of heavy metal associated (HMA) proteins in wheat.

| S. No. | Gene name | Transcript name |

Gene ID | Translation length (a.a) | Protein accession no. | Chr. | Subcellular location | Strand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | HMA1 | Traes_2AL_D0EABF355.2 | 31873047 | 863 | KAF7003072.1 | 2A | Plasma membrane | Forward |

| 2. | HMA2 | Traes_2BL_19B3E60AA.1 | 31802866 | 845 | KAF7010487.1 | 2B | Plasma membrane | Forward |

| 3. | HMA3 | Traes_2DL_51FF05F66.1 | 32015465 | 888 | KAF7017839.1 | 2D | Plasma membrane | Reverse |

| 4. | HMA4 | Traes_4AS_622EEFE10.2 | 31758612 | 648 | KAF7041053.1 | 4A | Chloroplast | Forward |

| 5. | HMA5 | Traes_4BL_89775421A.2 | 31775420 | 262 | KAF7050535.1 | 4B | Extracellular | Forward |

| 6. | HMA6 | Traes_4DL_385639507.1 | 31802013 | 604 | KAF7029642.1 | 4D | Chloroplast | Reverse |

| 7. | HMA7 | Traes_5AL_C89EEBE50.2 | 31899687 | 558 | XP_044438068.1 | 5A | Chloroplast | Reverse |

| 8. | HMA8 | Traes_5BL_D6C3DC326.1 | 31786522 | 829 | XP_044401945.1 | 5B | Plasma membrane | Reverse |

| 9. | HMA9 | Traes_5BL_F83C809F0.1 | 31807288 | 458 | XP_044424302.1 | 5B | Cytoplasmic | Forward |

| 10. | HMA10 | Traes_5DL_91C1891D3.1 | 31858473 | 632 | KAF7074611.1 | 5D | Plasma membrane | Forward |

| 11. | HMA11 | Traes_6AS_6F306F27E.1 | 31768608 | 974 | KAF7089256.1 | 6A | Cytoplasmic | Forward |

| 12. | HMA12 | Traes_6AS_9321C1C5B.2 | 31961570 | 1,074 | KAF7084039.1 | 6A | Plasma membrane | Reverse |

| 13. | HMA13 | Traes_6BS_9A12C2A1D.1 | 31766484 | 837 | KAF7098168.1 | 6B | Plasma membrane | Froward |

| 14. | HMA14 | Traes_6BS_A8B960E60.1 | 31836000 | 813 | XP_044412145.1 | 6B | Cytoplasmic | Reverse |

| 15. | HMA15 | Traes_6DS_26C5A0A44.1 | 31904930 | 980 | KAF7084123.1 | 6D | Plasma membrane | Forward |

| 16. | HMA16 | Traes_6DS_9FA053DF8.2 | 31748333 | 862 | KAF7098167.1 | 6D | Plasma membrane | Reverse |

| 17. | HMA17 | Traes_7AL_7A2639A1B.2 | 31943896 | 916 | XP_044424773.1 | 7A | Plasma membrane | Forward |

| 18. | HMA18 | Traes_7AL_8304348B7.1 | 32021814 | 790 | KAF7097469.1 | 7A | Extracellular | Forward |

| 19. | HMA19 | Traes_7DL_A5269C73F.2 | 31916999 | 1,061 | KAF110499.1 | 7D | Plasma membrane | Reverse |

| 20. | HMA20 | Traes_7BS_8EC4B41E4.1 | 31834193 | 737 | KAF7100926.1 | 7B | Chloroplast | Forward |

| 21. | HMA21 | Traes_7DS_04F16455B.1 | 31749939 | 804 | XP_044426682.1 | 7D | Plasma membrane | Reverse |

| 22. | HMA22 | Traes_7AS_766146E70.1 | 31803725 | 806 | KAF7095199.1 | 7A | Plasma membrane | Reverse |

| 23. | HMA23 | Traes_7BL_EFF0E2E31.1 | 31766590 | 718 | XP_037446570.1 | 7B | Chloroplast | Reverse |

| 24. | HMA24 | Traes_7DL_DF97DD324.1 | 31923629 | 959 | XP_020190440.1 | 7D | Chloroplast | Forward |

| 25. | HMA25 | Traes_7BL_041308E74.3 | 31832822 | 636 | XP_037464768.1 | 7B | Plasma membrane | Reverse |

| 26. | HMA26 | Traes_7AL_84D5BAE85.1 | 31955716 | 638 | XP_037460689.1 | 7A | Plasma membrane | Forward |

| 27. | HMA27 | Traes_7DL_271C7BED5.1 | 31915788 | 500 | XP_020187387.1 | 7D | Chloroplast | Forward |

Protein BLAST (Blastp) tool of NCBI was used to find similar sequences in wheat, using 50% identity as a threshold. Further, the motif finder online tool (https://www.genome.jp/tools/motif/) was used to confirm that these genes contain HMA domains. Peptide sequences not possessing HMA domains were deleted.

Determination of HMA protein properties

Different protein properties such as peptide length (a.a), DNA strand, chromosomal location, transcript ID, and subcellular locations were described in wheat while using Arabidopsis as model genome using online tools Expasy (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) and plant Ensemble tool (https://plants.ensembl.org/).

Sequence alignment and construction of phylogenetic tree

Full-length sequences of HMA proteins of Arabidopsis and wheat were aligned using ClustalX (Thompson et al., 1997) and were used for the construction of phylogenetic tree according to the neighbor-joining method of Saitou & Nei (1987) at 1,000 bootstrap value using the MEGA7 tool (Katsu et al., 2021).

Gene structure analysis

To observe the pattern of exon and intron organization in the HMA gene family, an online tool, gene structure display server GSDS 2.0 (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) was used. CDS and genomic sequences of wheat and Arabidopsis were used as input files however the default parameters of the tool remained unchanged.

Conserved motif analysis

Conserved motifs and HMA proteins were analyzed using the online tool MEME SUITE version 4.8.2 (https://meme-suite.org/meme/doc/release-notes.html) according to the method described by Li & Dewey (2011). These motifs were illustrated in the corresponding branch of the phylogenetic tree. Default parameters set were, a maximum number of motifs = 10, minimum motif width = 6 and maximum motif width = 50, minimum sites per motif = 2, and maximum sites per motif = 37.

Prediction of subcellular location

Subcellular locations of HMA proteins in wheat were determined using the tool WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/). An excel sheet was prepared to present the information about gene names and their location and their 14 nearest neighbors using the WoLF PSORT data and then TBTool (Guo et al., 2007) was used to create the heatmap.

Synteny analysis

An online tool of synteny viewer tool (tools.bat.infspire.org/circoletto/) was used to find the evolutionary relationship between Wheat and Arabidopsis HMA proteins. Protein sequences of all the HMA downloaded proteins were used as input files to compare the wheat genome with Arabidopsis using default parameters (Darzentas, 2010).

Identification of homologous pairs and calculating Ks/Ka values

Homologous pairs of HMA genes were manually selected from the phylogenetic tree and Ks/Ka values were calculated using TBTool using genomic sequences, protein sequences, and gene duplication pairs as input files.

Results

Sequencing of the wheat genome has made it possible to identify the HMA genes in this important cereal crop. The HMA gene family was not previously characterized in wheat. Therefore, we selected HMA gene family and performed genome wide survey in wheat (T. aestivum). We used Arabidopsis HMA proteins using the blastp tool to find similar sequences in wheat. A total of 27 genes of the HMA gene family were found in wheat in this study.

Characteristics of Arabidopsis HMA proteins

In Arabidopsis HMA gene family was comprised of 10 members. In Arabidopsis HMA genes were located on all the chromosomes except chromosome 3. Amino acid length of HMA proteins was ranged from 542 to 1,172 (Table 1). The subcellular location analysis indicated that six HMA proteins were present in the plasma membrane and four in the chloroplast. Four genes were located on reverse strand and six on the forward strand.

We identified 27 HMA proteins in wheat. Gene location indicated that wheat HMA genes were present on the 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th chromosomes. Out of 27 proteins, 15 were present in the plasma membrane, 10 in the chloroplast, and two in extracellular locations. Seventeen proteins were present on the forward strand and 10 on the reverse strand. Amino acid length of wheat HMA proteins ranged from 262 to 1,071 (Table 2).

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic association

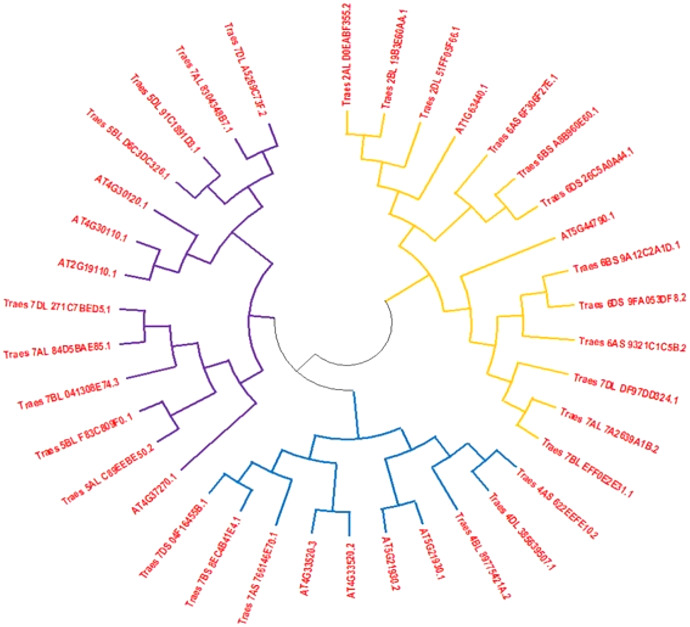

Full-length HMA protein sequences from wheat and Arabidopsis obtained from different databases were used to construct the phylogenetic tree to assess the phylogenetic association among both plant species. The phylogenetic tree indicated that HMA proteins were distributed in three subgroups. Clad one was the largest subgroup containing 14 proteins that were belonging to both species, second clad consisted of 11 members and third clad was comprised of 13 members (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. An unrooted phylogenetic tree of Arabidopsis (At) and wheat (Ta).

Tree of HMA proteins constructed by the following of neighbor-joining method with MEGA6.0 software. Three subclasses were differentiated by orange, blue and dark blue colors.

Gene structure analysis

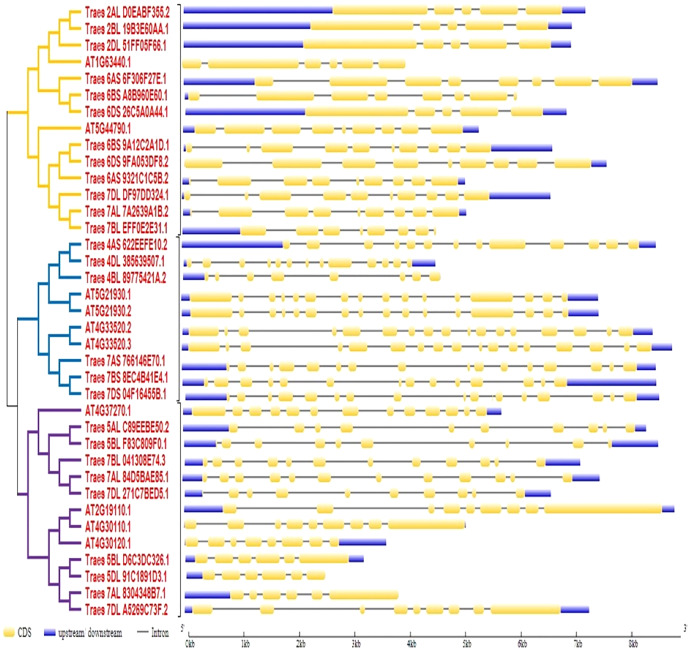

To predict the exon-intron organization in wheat and Arabidopsis HMA genes, CDS and genomic DNA were used as input files. The organization pattern of intron/exons in HMA genes was displayed to the relative branch in the phylogenetic tree. It was observed that several introns and exons varied among these genes. Arabidopsis genes ATG33520.2 and ATG33520.3 showed the largest number of exons (17) whereas four wheat genes showed the fewest (five) exons. Further, it was observed that closely related members in a subclass showed similar intron-exon pattern (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Gene structure analysis of HMA genes in wheat and Arabidopsis.

Exon/intron pattern was predicted by gene structure display server 2. CDS/Exons were presented with yellow color, intron with the black line, and upstream/downstream with blue color.

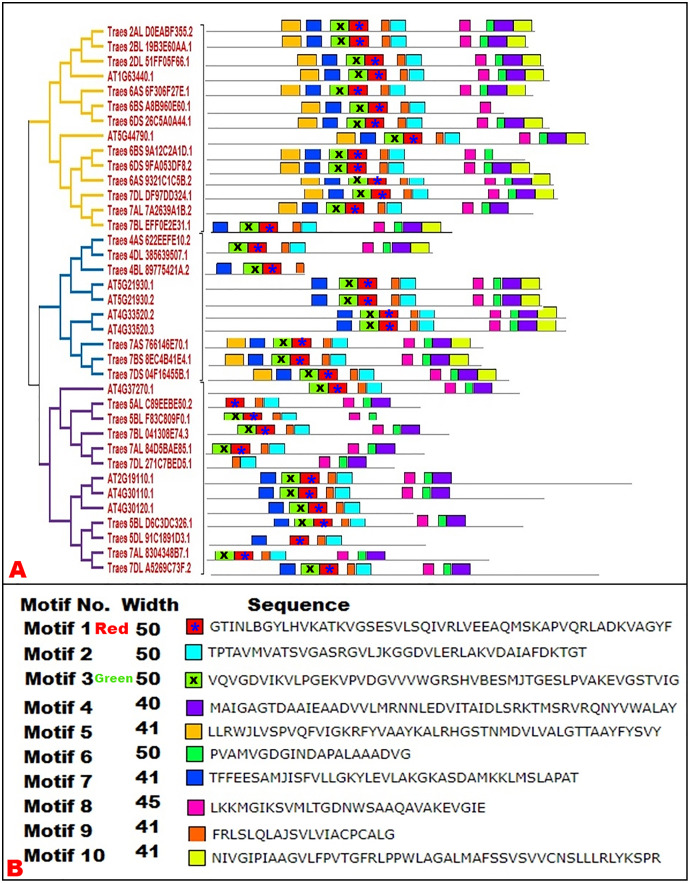

Conserved motif analysis

To predict the conserved domains in wheat and Arabidopsis HMA proteins, motif analysis was performed. Ten distinct motifs were discovered in both plant species. We selected the motif width from 10 to 50 as default parameters however it was noted that motif width was ranging from 40 to 50 indicating that highly conserved regions in HMA proteins were present. Each motif was displayed to the concerned protein on the phylogenetic tree to explore the motif pattern according to the phylogenetic association. It was noted that closely linked proteins in phylogenetic tree were showing the same expression pattern as the motifs falling in different subgroups of tree (Fig. 3). Our results regarding the conservation of motifs within subgroups were supported by previous studies on different gene families (Azeem et al., 2018; Waqas et al., 2019).

Figure 3. Conserved motifs of HMA proteins in wheat and Arabidopsis.

Each motif was distinct from the other and represented by various colors, discovered by MEME Suit tool. (A) An asterisk (*) in the red and ‘x’ in the green color box is to distinguish between the colors for greater accessibility.

Prediction of subcellular locations

Subcellular locations of 27 HMA proteins were predicted in various subcellular components such as nucleus, plasma membrane, cytoplasm, vacuole, endoplasmic reticulum, chloroplast, golgi bodies, mitochondria, and extracellular locations. Results indicated that most of the proteins were present in plasma membranes followed by endoplasmic reticulum and vacuoles whereas lowest proteins were located on extracellular locations and golgi bodies (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Subcellular location of HMA proteins in Arabidopsis and wheat.

Heatmap was constructed by using TBTool. Where NUC, nucleus; Plas, plasma membrane; Cyto, cytoplasm; VAC, vacuole; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; CHL, chloroplast; GOLG, golgi body; Mito, mitochondria; EXTRA, extracellular.

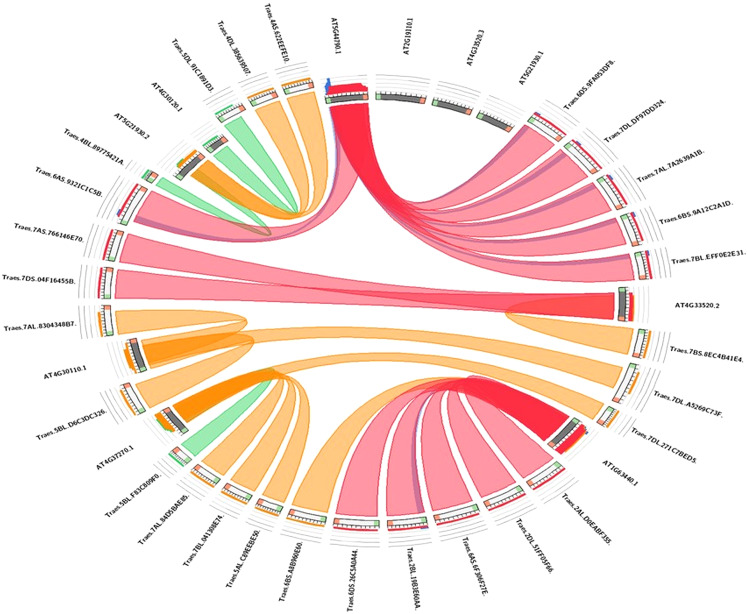

Synteny analysis

The evolutionary link of Arabidopsis HMA genes with wheat genes was assessed through a micro-syntenic tool. It was concluded that most of the wheat HMA genes and Arabidopsis HMA genes have similar evolutionary origin (Fig. 5). Traes.7AS.766146E70.1 and Traes.7DS.04F16455B.1 were originated from Arabidopsis gene AT4G33520.2. Similarly, Arabidopsis gene AT4G30110.1 gave rise to wheat Traes_5BL_D6C3DC326.1, Traes_7AL_8304348B7.1 and Traes_7BS_8EC4B41E4.1. Traes_6DS_9FA053DF8.2, Traes_7DL_DF97DD324.1, Traes_7AL_7A2639A1B.2, Traes_6BS_9A12C2A1D.1 and Traes_7BL_EFF0E2E31.1 were evolutionary originated from AT2G19110.1.

Figure 5. Visualization of the sequence similarity of wheat HMA genes with Arabidopsis HMA genes.

In the circuletto tool wheat HMA proteins were used as query and Arabidopsis proteins as comparative files as per default parameters of the tool. Colored lines which connect two regions indicate syntenic regions between Arabidopsis and wheat.

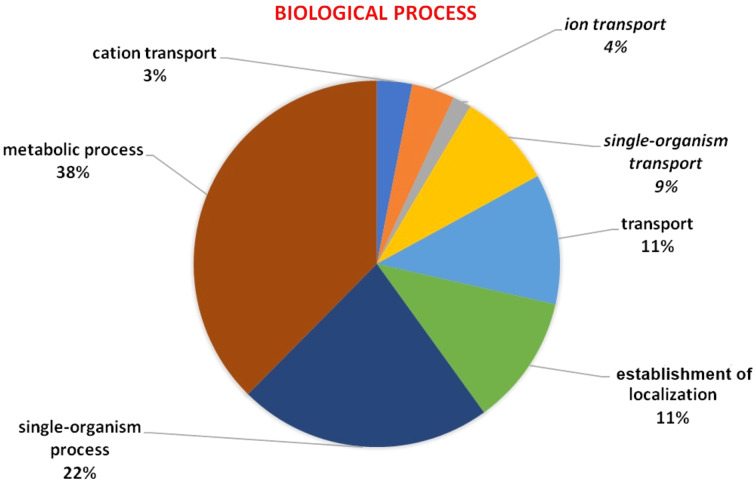

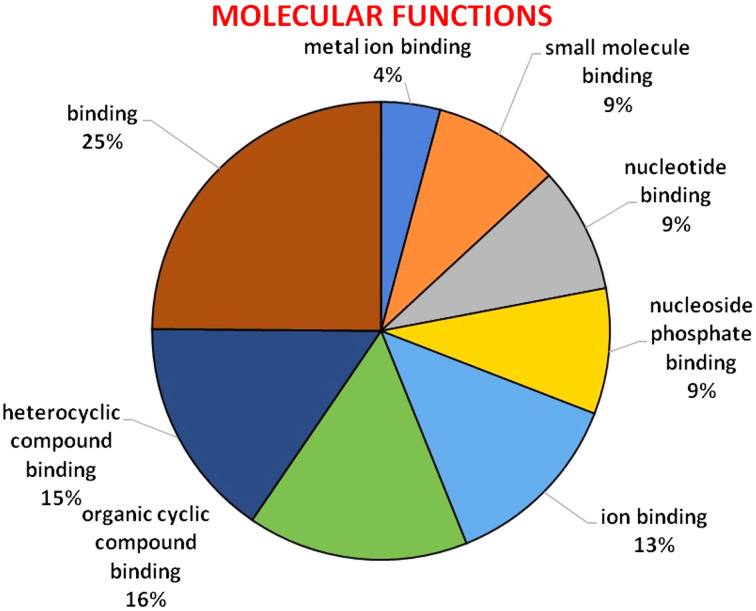

Gene ontology

GO analysis was used to describe the functions of a gene such as involvement in biological processes, molecular activities of the gene products, and location of these activities. GO analysis indicated that HMA genes were mainly involved in metabolic processes, single-organism process, localization establishment, single organism transport, metal ion, ion, and cation transport (Fig. 6). Molecular functions of HMA genes observed through GO tools indicated that these genes are mainly involved in various types of binding activities. The percentage of binding with different compounds is shown in Fig. 7. HMA genes mainly bind with organic cyclic compounds, heterocyclic compounds, ion binding, nucleotides, and nucleoside bindings.

Figure 6. GO of biological process determined through Blast2GO tool using the Arabidopsis, and wheat HMA proteins as a query.

Various biological processes carried out by these genes were distinguished by different colors.

Figure 7. GO of molecular functions determined through Blast2GO tool using the Arabidopsis, and wheat HMA proteins as a query.

The genes were distinguished by different colors.

Ka/Ks ratio determines the ratio of beneficial mutations and neutral mutations present on a set of homologous genes. This ratio also indicates the net balance between beneficial and deleterious mutations. Six gene pairs were duplicated in wheat belonging to the HMA family. Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks ratio was calculated using TBtool. The ratio of Ka/Ks value in the Table 3 indicated that all the six homologous pairs showed a value less than one. Ka/Ks greater than one expressed positive selection, less than one indicates purified/stable selection and equal to one indicates neutral selection. Hence according to results, Ka/Ks value of all the pairs is below one which means HMA genes have the stable and purifying selection.

Table 3. Estimated time of divergence of wheat heavy metal associated (HMA) genes.

| S. No. | Seq_1 | Seq_2 | Ka | Ks | Ka/Ks | T (MYA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Traes_7AL_7A2639A1B.2 | Traes_7BL_EFF0E2E31.1 | 0.007469 | 0.118871 | 0.062836074 | 9.90589E−09 |

| 2. | Traes_7BS_8EC4B41E4.1 | Traes_7DS_04F16455B.1 | 0.008408 | 0.042414 | 0.1982277 | 3.53451E−09 |

| 3. | Traes_5AL_C89EEBE50.2 | Traes_5BL_F83C809F0.1 | 0.033487 | 0.10141 | 0.330218025 | 8.4508E−09 |

| 4. | Traes_7AL_84D5BAE85.1 | Traes_7DL_271C7BED5.1 | 0.001769 | 0.050569 | 0.03498181 | 4.21409E−09 |

| 5. | Traes_5BL_D6C3DC326.1 | Traes_5DL_91C1891D3.1 | 0.181692 | 0.332826 | 0.545906617 | 2.77355E−08 |

| 6. | Traes_7AL_8304348B7.1 | Traes_7DL_A5269C73F.2 | 0.007949 | 0.090577 | 0.087758967 | 7.54811E−09 |

Discussion

Abiotic stresses like drought and heavy metal toxicity have presented a severe challenge to global food production. The impacts of heavy metals on plants and their ability to withstand metal toxicity have been widely studied (Gao et al., 2020). The consequences of heavy metal stress on a plant’s ability to deal with other environmental difficulties, including water scarcity, have received less attention (Barceló & Poschenrieder, 2004). Previously, a mutation in HMA domain in the chimeric allele of the drought resistant wheat mutant NN1-M-700 was responsible for drought stress tolerance (Zahra et al., 2021b). Heavy-metal-associated domain (HMAD) has been found to have a variety of vital roles in Arabidopsis, and significant progress was achieved in identifying HMA genes in many other plants (Li et al., 2016; Sutkovic et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021). However, reports regarding this gene in hexaploid wheat are meager. In wheat and other crop species, the HMA gene family plays a significant role in heavy metal transport and abiotic stress tolerance (Wu et al., 2019).

Drought is known as one of the most prevalent strain in metal-contaminated ecosystems (Sitko et al., 2021). Various plant indicators are used to compare heavy metal exposure with drought stress, such as photosynthetic performance and stomatal behavior, photosynthetic pigment, proline, and peroxidase. Abiotic stress crosstalk includes the ROS (reactive oxygen species) signal and the antioxidant system, as well as drought stress and heavy metal stress (Khan, Ahmed & Shah, 2022). Metal-rich soils often have poor structure, reduced bacterial activity, and minimal organic matter content, resulting in inadequate moisture-holding capacity (Derome & Nieminen, 1998; Wang et al., 2007).Toxic metal exposure has also been shown to affect plant traits essential for plant-water associations, including abscisic acid (ABA) concentrations (Barceló & Poschenrieder, 1986), cell wall elasticity (Barceló & Poschenrieder, 1986), root elongation (Kahle, 1993), organic matter allocation to roots (Ryser & Emerson, 2007), and root permeability for water (Ryser & Emerson, 2007; Przedpelska-Wasowicz & Wierzbicka, 2011). Furthermore, in metal-exposed plants, hydraulic and stomatal conductance has been reported to be reduced (Lamoreaux & Chaney, 1977; Disante, Fuentes & Cortina, 2011). Similar findings were observed in EMS mutant lines of NN-1 wheat (NN1-M-363, NN1-M-506, NN1-M-700, NN1-M-701, and NN1-M-1621) (Zahra et al., 2021b). All of the above physiological processes may reduce water uptake in metal-stressed plants, aggravating the consequences of drought stress.

In the present research, we provided a complete overview of HMA gene family in wheat. Further, we analyzed the phylogenetic relationship, subcellular location, gene structure, conserved motifs, identification of homologous pairs, and Ka/Ks ratio under drought conditions. A plant’s sensitivity to various stresses cannot always be inferred from their responses to specific stresses (Mittler, 2006). Despite substantial study of the effects of drought and metals on plants as separate stimuli, experiments subjecting plants to both stresses at the same time are rare. For annual plants like wheat and rye (Klimov, 1985), sunflower (Krizek, Foy & Wergin, 1988), and barley (Krizek, Foy & Wergin, 1988), metal stress and drought stress have been demonstrated to have synergistic growth-reducing effects (Krizek, Foy & Wergin, 1988). In this study, the phylogenetic tree domenstrated six homologous pairs of HMA genes in the wheat genome. Similar findings were published in another study on wheat by (Zhou et al., 2019). According to gene ontology, the activity or action done by a gene product is determined by its molecular function. In general terms, a molecular function, is a process carried out by a single molecular mechanism through direct physical contact with other molecular entities.

Furthermore, the distribution pattern of intron and exon is a significant tool to study comparative genomics in order to acquire understanding about a gene family, because it supports the evolutionary link of a gene with its predecessors (Waqas et al., 2019). It was observed that several introns and exons varied among these genes. Arabidopsis genes ATG33520.2 and ATG33520.3 showed the largest number of exons (17) whereas four wheat genes showed the fewest (5) exons. Further, it was observed that closely related members in a subclass showed similar intron- exon pattern (Zhang et al., 2019). To check the significance of HMA proteins in plant growth and development, we examined their distribution in several subcellular components. Locations of twenty-seven identified HMA proteins were predicted in various subcellular components such as the nucleus, plasma membrane, cytoplasm, vacuole, endoplasmic reticulum, chloroplast, golgi bodies, mitochondria, and extracellular locations. These proteins were shown to be abundant in the plasma membrane, demonstrating their importance in metal ion transport. Our findings are comparable with those of Zhou et al. (2019), who showed similar results in wheat HMA proteins. Variances in gene structure among members of the same class may be due to differences in evolutionary history, and these proteins may have novel functional properties (Yang et al., 2019).

The current findings show that HMA proteins have a wide range of activities. It has also been shown that there is a phylogenetic specific pattern of conserved domains (Azeem et al., 2018; Waqas et al., 2019). This pattern of conserved motifs suggested that HMA genes shared a recent common ancestor. Furthermore, the occurrence of conserved motifs leads to functional conservation and gene duplication processes in plants (Waqas et al., 2019). In polyploids, gene and genome duplication is a dominant factor in the evolution of complexity and diversity. Conserved motifs also indicate the variety of domain design, which has been used to retain domains outside the key parts of HMA genes, and play a vital role in protein function (Du et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2020). Various HMA proteins including the A. thaliana AtHMA1 protein, were shown to be involved in zinc/cadmium transport and chloroplast copper mobilization (Moreno et al., 2008). Furthermore, HvHMA in barley grains (Mikkelsen et al., 2012), studies on expression of OsHMA1 in rice (Zhou et al., 2019), and analysis of Arabidopsis HMA2 gene (Eren & Arguello, 2004) shown their role in important cellular processes. In wheat, TaHMA2 is restricted to the plasma membrane and promotes Zn and Cd translocation from the root to the shoot (Tan et al., 2017).

Proteins from Arabidopsis (AtHMA3), rice (OsHMA3), and wheat (TaHMA3) are found in tonoplasts and are involved in transport of Zn and Cu to the vacuole (Zhang et al., 2021). In Brassica juncea, the HMA4 gene promotes heavy metal transport and binding, as well as increasing heavy metal resistance in yeast and E. coli (Wang et al., 2019). AtHMA5 mediates Cu transport from roots to the leaves or root detoxification (Zhou et al., 2019). Cu is transported to chloroplast envelope AtHMA6 (also known as PAA1), whereas it is transported into the thylakoid lumen to provide plastocyanin by AtHMA8 (PAA2) (Zhang et al., 2019). Cu is transported to ethylene receptors and Cu homeostasis in seedlings are mainly mediated by AtHMA7 (Binder, Rodríguez & Bleecker, 2010). Furthermore, studies with numerous species, including A. thaliana (Eren & Arguello, 2004), O. sativa (Huang et al., 2016), Noccaea caerulescens (Lochlainn et al., 2011), Sedum alfredii (Zhang et al., 2016), and Sedum plumbi zincicola (Liu et al., 2017) have reports on proteins like HMA2, HMA3, HMA4, HMA5 or HMA9.

Prior investigations have demonstrated that several similar proteins are engaged in the transport of different heavy metals and are responsible for the cross-tolerance process when combined with antioxidative enzymes. They assist plants in adapting to a wide range of stresses (Zschiesche et al., 2015; Cowan et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020). In Quercus suber and Coriandrum sativum L, however, the presence of large amounts of Zn and Cd reduced the impact of water stress on photosynthesis, stomatal conductance, and relative water content (Khan et al., 2021; Disante, Fuentes & Cortina, 2011). Metal contamination of the substrate decreased the effect of substrate moisture on white birch growth when the water supply was adequate (Santala & Ryser, 2009). The Ka/Ks ratio, also known as the dN/dS ratio, is the ratio of the number of nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site (Ka) in a certain time period to the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (Ks) in the same period. According to the current findings, the synonymous/nonsynonymous ratio was greater than one in all of the chosen homologous pairs, indicating that selection among HMA genes in wheat is stable and purified. However, because no data on HMA genes in wheat was previously available, the results were not compared.

Conclusions

In the current study, the comprehensive identification of HMA genes in wheat (T. aestivum L) along with their syntenic analysis, gene structure, conserved motifs analysis, and Ka/Ks values were investigated. The result revealed a total of 27 wheat proteins belonging to the HMA gene family, ranging in amino acid count from 262 to 1,071. The study examined the specific functions of the HMAD gene family in drought-stressed wheat. The phylogenetic tree revealed that HMA proteins were divided into three subgroups, with closely related proteins in the tree displaying the same expression pattern as motifs from different subgroups. Gene structural analysis revealed that intron and exon arrangement was family-specific. Our results offer a base for further investigation on the crosstalk of molecular mechanisms of HMA genes under abiotic stress and heavy metal conditions. In future, this research might be used to better describe the significance of the HMA gene family in wheat and other crops by manipulating stress responsive genes.

Supplemental Information

Funding Statement

The authors received no funding for this work.

Contributor Information

Tayyaba Shaheen, Email: tayyabashaheen@gcuf.edu.pk.

Mahmood-ur-Rahman, Email: mahmoodansari@gcuf.edu.pk.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

Mahmood-ur-Rahman is an Academic Editor for PeerJ.

Author Contributions

Sadaf Zahra performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Tayyaba Shaheen conceived and designed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Muhammad Qasim analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Mahmood-ur-Rahman conceived and designed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Momina Hussain performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Sana Zulfiqar performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Kanval Shaukat analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Mehboob-ur-Rahman analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data is available in the Supplemental Files.

References

- Ahmad et al. (2018).Ahmad HM, Mahmood-ur-Rahman, Azeem F, Tahir N, Iqbal MS. QTL mapping for crop improvement against abiotic stresses in cereals. Journal of Animal & Plant Sciences. 2018;26(6):1558–1573. [Google Scholar]

- Azeem et al. (2018).Azeem F, Ahmad B, Atif RM, Ali MA, Nadeem H, Hussain S, Manzoor H, Azeem M, Afzal M. Genome-wide analysis of potassium transport-related genes in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) and their role in abiotic stress responses. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter. 2018;36(3):451–468. doi: 10.1007/s11105-018-1090-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barceló & Poschenrieder (2004).Barceló J, Poschenrieder C. Heavy Metal Stress in Plants. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2004. Structural and ultrastructural changes in heavy metal exposed plants; pp. 223–248. [Google Scholar]

- Barceló & Poschenrieder (1986).Barceló JU, Poschenrieder C. Cadmium-induced decrease of water stress resistance in bush bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L. cv Contender). II. Effects of Cd on endogenous abscisic acid levels. Journal of Plant Physiology. 1986;125(1–2):27–34. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(86)80240-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bari et al. (2018).Bari A, Farooq M, Hussain A, Qamar MT, Abbas MW, Mustafa G, Karim A, Ahmed I, Hussain T. Genome-wide bioinformatics analysis of aquaporin gene family in maize (Zea mays L.) Journal of Phylogenetics & Evolutionary Biology. 2018;6(2):1000197. doi: 10.4172/2329-9002.1000197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Binder, Rodríguez & Bleecker (2010).Binder BM, Rodríguez FI, Bleecker AB. The copper transporter RAN1 is essential for biogenesis of ethylene receptors in Arabidopsis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(48):37263–37270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.170027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappetta et al. (2020).Cappetta E, Andolfo G, Di Matteo A, Ercolano MR. Empowering crop resilience to environmental multiple stress through the modulation of key response components. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2020;246(8):153134. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2020.153134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan et al. (2018).Cowan GH, Roberts AG, Jones S, Kumar P, Kalyandurg PB, Gil JF, Savenkov EI, Hemsley PA, Torrance L. Potato mop-top virus co-opts the stress sensor HIPP26 for long-distance movement. Plant Physiology. 2018;176(3):2052–2070. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzentas (2010).Darzentas N. Circoletto: visualizing sequence similarity with Circos. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(20):2620–2621. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derome & Nieminen (1998).Derome J, Nieminen T. Metal and macronutrient fluxes in heavy-metal polluted scots pine ecosystems in SW Finland. Environmental Pollution. 1998;103(2–3):219–228. doi: 10.1016/S0269-7491(98)00118-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Disante, Fuentes & Cortina (2011).Disante KB, Fuentes D, Cortina J. Response to drought of Zn-stressed Quercus suber L. seedlings. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2011;70(2–3):96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2010.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du et al. (2013).Du HA, Wang YB, Xie YI, Liang ZH, Jiang SJ, Zhang SS, Huang YB, Tang YX. Genome-wide identification and evolutionary and expression analyses of MYB-related genes in land plants. DNA Research. 2013;20(5):437–448. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dst021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eren & Arguello (2004).Eren E, Arguello JM. Arabidopsis HMA2, a divalent heavy metal-transporting PIB-type ATPase, is involved in cytoplasmic Zn2+ homeostasis. Plant Physiology. 2004;136(3):3712–3723. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.046292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao et al. (2020).Gao M, Xu Y, Chang X, Dong Y, Song Z. Effects of foliar application of graphene oxide on cadmium uptake by lettuce. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2020;398(1–3):122859. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grispen et al. (2011).Grispen VM, Hakvoort HW, Bliek T, Verkleij JA, Schat H. Combined expression of the Arabidopsis metallothionein MT2b and the heavy metal transporting ATPase HMA4 enhances cadmium tolerance and the root to shoot translocation of cadmium and zinc in tobacco. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2011;72(1):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2010.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo et al. (2007).Guo AY, Zhu QH, Chen X, Luo JC. GSDS: a gene structure display server. Yi Chuan Hereditas. 2007;29(8):1023–1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He et al. (2020).He G, Qin L, Tian W, Meng L, He T, Zhao D. Heavy metal transporters-associated proteins in Solanum tuberosum: genome-wide identification, comprehensive gene feature, evolution and expression analysis. Genes. 2020;11(11):1269. doi: 10.3390/genes11111269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang et al. (2016).Huang XY, Deng F, Yamaji N, Pinson SR, Fujii-Kashino M, Danku J, Douglas A, Guerinot ML, Salt DE, Ma JF. A heavy metal P-type ATPase OsHMA4 prevents copper accumulation in rice grain. Nature Communications. 2016;7(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imran et al. (2016).Imran QM, Falak N, Hussain A, Mun BG, Sharma A, Lee SU, Kim KM, Yun BW. Nitric oxide responsive heavy metal-associated gene AtHMAD1 contributes to development and disease resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2016;7(170):1712. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam & Sandhi (2022).Islam M, Sandhi A. Heavy metal and drought stress in plants: the role of microbes—a review. Gesunde Pflanzen. 2022;227(1):37. doi: 10.1007/s10343-022-00762-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Javed et al. (2016).Javed I, Awan SI, Ahmad HM, Rao A. Assesment of genetic diversity in wheat synthetic double haploids for yield and drought related traits through factor and cluster analyses. Plant Gene and Trait. 2016;7(3):1–9. doi: 10.5376/pgt.2016.07.0003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle (1993).Kahle H. Response of roots of trees to heavy metals. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 1993;33(1):99–119. doi: 10.1016/0098-8472(93)90059-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katsu et al. (2021).Katsu K, Nijo T, Yoshida T, Okano Y, Nishikawa M, Miyazaki A, Maejima K, Namba S, Yamaji Y. Complete genome sequence of pleioblastus mosaic virus, a distinct member of the genus Potyvirus. Archives of Virology. 2021;166(2):645–649. doi: 10.1007/s00705-020-04916-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Ahmed & Shah (2022).Khan MT, Ahmed S, Shah AA. Regulatory role of folic acid in biomass production and physiological activities of Coriandrum sativum L. under irrigation regimes. International Journal of Phytoremediation. 2022;24(10):1025–1038. doi: 10.1080/15226514.2021.1993785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan et al. (2021).Khan MT, Ahmed S, Shah AA, Noor Shah A, Tanveer M, El-Sheikh MA, Siddiqui MH. Influence of zinc oxide nanoparticles to regulate the antioxidants enzymes, some osmolytes and agronomic attributes in Coriandrum sativum L. grown under water stress. Agronomy. 2021;11(10):2004. doi: 10.3390/agronomy11102004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klimov (1985).Klimov SV. Interaction of stress factors: increase of drought effect by the presence of Al3+ in the medium. Fiziologi Rasteni. 1985;32:532–538. [Google Scholar]

- Krizek, Foy & Wergin (1988).Krizek DT, Foy CD, Wergin WP. Role of water stress in differential aluminum tolerance of six sunflower cultivars grown in an acid soil. Journal of Plant Nutrition. 1988;11(4):387–408. doi: 10.1080/01904168809363810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamoreaux & Chaney (1977).Lamoreaux RJ, Chaney WR. Growth and water movement in silver maple seedlings affected by cadmium. American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, and Soil Science Society of America. 1977;6(2):201–205. doi: 10.2134/jeq1977.00472425000600020021x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li & Dewey (2011).Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al. (2016).Li C, Sun Y, Liu H, Zeng Q, Wang Y, Ma J, Yang Y, Xu M. Genetic variation analysis of heavy metal ATPase-like gene in rice. Southwest China Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 2016;29(9):2009–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liu et al. (2017).Liu X, Fan Y, Mak M, Babla M, Holford P, Wang F, Chen G, Scott G, Wang G, Shabala S, Zhou M. QTLs for stomatal and photosynthetic traits related to salinity tolerance in barley. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3380-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochlainn et al. (2011).Lochlainn SO, Bowen HC, Fray RG, Hammond JP, King GJ, White PJ, Graham NS, Broadley MR. Tandem Quadruplication of HMA4 in the Zinc (Zn) and Cadmium (Cd) Hyperaccumulator Noccaea caerulescens. PLOS ONE. 2011;6(3):e17814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen et al. (2012).Mikkelsen MD, Pedas P, Schiller M, Vincze E, Mills RF, Borg S, Møller A, Schjoerring JK, Williams LE, Baekgaard L, Holm PB. Barley HvHMA1 is a heavy metal pump involved in mobilizing organellar Zn and Cu and plays a role in metal loading into grains. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(11):e49027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler (2006).Mittler R. Abiotic stress, the field environment and stress combination. Trends in Plant Science. 2006;11(1):15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno et al. (2008).Moreno I, Norambuena L, Maturana D, Toro M, Vergara C, Orellana A, Zurita-Silva A, Ordenes VR. AtHMA1 is a thapsigargin-sensitive Ca2+/heavy metal pump. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(15):9633–9641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przedpelska-Wasowicz & Wierzbicka (2011).Przedpelska-Wasowicz EM, Wierzbicka M. Gating of aquaporins by heavy metals in Allium cepa L. epidermal cells. Protoplasma. 2011;248(4):663–671. doi: 10.1007/s00709-010-0222-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza et al. (2019).Raza A, Razzaq A, Mehmood SS, Zou X, Zhang X, Lv Y, Xu J. Impact of climate change on crops adaptation and strategies to tackle its outcome: a review. Plants. 2019;8(2):34. doi: 10.3390/plants8020034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi et al. (2020).Rizvi A, Zaidi A, Ameen F, Ahmed B, AlKahtani MD, Khan MS. Heavy metal induced stress on wheat: phytotoxicity and microbiological management. RSC Advances. 2020;2020(10):38379–38403. doi: 10.1039/D0RA05610C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryser & Emerson (2007).Ryser P, Emerson P. Growth, root and leaf structure, and biomass allocation in Leucanthemum vulgare Lam.(Asteraceae) as influenced by heavy-metal-containing slag. Plant and Soil. 2007;301(1):315–324. doi: 10.1007/s11104-007-9451-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou & Nei (1987).Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1987;4(4):406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santala & Ryser (2009).Santala KR, Ryser P. Influence of heavy-metal contamination on plant response to water availability in white birch, Betula papyrifera. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2009;66(2):334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2009.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sitko et al. (2021).Sitko K, Opała-Owczarek M, Jemioła G, Gieroń Ż, Szopiński M, Owczarek P, Rudnicka M, Małkowski E. Effect of drought and heavy metal contamination on growth and photosynthesis of silver birch trees growing on post-industrial heaps. Cells. 2021;11(1):53. doi: 10.3390/cells11010053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun et al. (2014).Sun XH, Yu G, Li JT, Jia P, Zhang JC, Jia CG, Zhang YH, Pan HY. A heavy metal-associated protein (AcHMA1) from the halophyte, Atriplex canescens (Pursh) Nutt., confers tolerance to iron and other abiotic stresses when expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2014;15(8):14891–14906. doi: 10.3390/ijms150814891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutkovic et al. (2016).Sutkovic J, Kekić M, Ljubijankić M, Glamočlija P. An in silico approach for structural and functional analysis of heavy metal associated (HMA) proteins in Brassica oleracea. Periodicals of Engineering and Natural Sciences. 2016;4(2):41–59. doi: 10.21533/pen.v4i2.63. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan et al. (2017).Tan M, Cheng D, Yang Y, Zhang G, Qin M, Chen J, Chen Y, Jiang M. Co-expression network analysis of the transcriptomes of rice roots exposed to various cadmium stresses reveals universal cadmium-responsive genes. BMC Plant Biology. 2017;17(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1143-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan et al. (2020).Tan L, Ijaz U, Salih H, Cheng Z, Ni Win Htet N, Ge Y, Azeem F. Genome-wide identification and comparative analysis of MYB transcription factor family in Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana. Plants. 2020;9(4):413. doi: 10.3390/plants9040413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson et al. (1997).Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25(24):4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasil (2007).Vasil IK. Molecular genetic improvement of cereals: transgenic wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Plant Cell Reports. 2007;26(8):1133–1154. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. (2019).Wang F, Huang C, Chen Z, Bao K. Distribution, ecological risk assessment, and bioavailability of cadmium in soil from Nansha, Pearl River Delta, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16(19):3637. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16193637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. (2007).Wang Y, Shi J, Wang H, Lin Q, Chen X, Chen Y. The influence of soil heavy metals pollution on soil microbial biomass, enzyme activity, and community composition near a copper smelter. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2007;67(1):75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waqas et al. (2019).Waqas M, Azhar MT, Rana IA, Azeem F, Ali MA, Nawaz MA, Chung G, Atif RM. Genome-wide identification and expression analyses of WRKY transcription factor family members from chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) reveal their role in abiotic stress-responses. Genes & Genomics. 2019;41(4):467–481. doi: 10.1007/s13258-018-00780-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu et al. (2019).Wu Y, Li X, Chen D, Han X, Li B, Yang Y, Yang Y. Comparative expression analysis of heavy metal ATPase subfamily genes between Cd-tolerant and Cd-sensitive turnip landraces. Plant Diversity. 2019;41(4):275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.pld.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji et al. (2013).Yamaji N, Xia J, Mitani-Ueno N, Yokosho K, Feng Ma J. Preferential delivery of zinc to developing tissues in rice is mediated by P-type heavy metal ATPase OsHMA2. Plant Physiology. 2013;162(2):927–939. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.216564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang et al. (2019).Yang K, Li Y, Wang S, Xu X, Sun H, Zhao H, Li X, Gao Z. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the MYB transcription factor in moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) PeerJ. 2019;6:e6242. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahra et al. (2021a).Zahra S, Hussain M, Zulfiqar S, Ishfaq S, Shaheen T, Akhtar M. EMS-based mutants are useful for enhancing drought tolerance in spring wheat. Cereal Research Communications. 2021a;50:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s42976-021-00220-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zahra et al. (2021b).Zahra S, Shaheen T, Hussain M, Zulfiqar S, Rahman MU. Multivariate analysis of mutant wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) lines under drought stress. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry. 2021b;45(5):617–633. doi: 10.3906/tar-2106-73. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang & Sonnewald (2017).Zhang H, Sonnewald U. Differences and commonalities of plant responses to single and combined stresses. The Plant Journal. 2017;90(5):839–855. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2019).Zhang L, Wu J, Tang Z, Huang XY, Wang X, Salt DE, Zhao FJ. Variation in the BrHMA3 coding region controls natural variation in cadmium accumulation in Brassica rapa vegetables. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2019;70(20):5865–5878. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2021).Zhang C, Yang Q, Zhang X, Zhang X, Yu T, Wu Y, Fang Y, Xue D. Genome-wide identification of the HMA gene family and expression analysis under Cd stress in barley. Plants. 2021;10(9):1849. doi: 10.3390/plants10091849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2020).Zhang H, Zhang X, Liu J, Niu Y, Chen Y, Hao Y, Zhao J, Sun L, Wang H, Xiao J, Wang X. Characterization of the heavy-metal-associated isoprenylated plant protein (HIPP) gene family from Triticeae species. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020;21(17):6191. doi: 10.3390/ijms21176191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2016).Zhang J, Zhang M, Shohag M, Islam J, Tian S, Song H, Feng Y, Yang X. Enhanced expression of SaHMA3 plays critical roles in Cd hyper accumulation and hyper tolerance in Cd hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii Hance. Planta. 2016;243(3):577–589. doi: 10.1007/s00425-015-2429-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou et al. (2019).Zhou M, Zheng S, Liu R, Lu L, Zhang C, Zhang L, Yant L, Wu Y. The genome-wide impact of cadmium on microRNA and mRNA expression in contrasting Cd responsive wheat genotypes. BMC Genomics. 2019;20(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5939-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zschiesche et al. (2015).Zschiesche W, Barth O, Daniel K, Böhme S, Rausche J, Humbeck K. The zinc-binding nuclear protein HIPP 3 acts as an upstream regulator of the salicylate-dependent plant immunity pathway and of flowering time in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytologist. 2015;207(4):1084–1096. doi: 10.1111/nph.13419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data is available in the Supplemental Files.