Summary

Background

People with immune dysfunction are at higher risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19 infection, but relatively little epidemiologic information is available for mostly vaccinated population in the Omicron era. This population-based study compared relative risk of breakthrough COVID-19 hospitalisation among vaccinated people identified as clinically extremely vulnerable (CEV) vs non-CEV individuals before treatment became more widely available.

Methods

COVID-19 cases and hospitalisations reported to the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) between January 7, 2022 and March 14, 2022 were linked with data on their vaccination and CEV status. Case hospitalisation rates were estimated across CEV status, age groups and vaccination status. For vaccinated individuals, risk ratios for breakthrough hospitalisations were calculated for CEV and non-CEV populations matched on sex, age group, region, and vaccination characteristics.

Findings

Among CEV individuals, a total of 5591 COVID-19 reported cases were included, among which 1153 were hospitalized. A third vaccine dose with mRNA vaccine offered additional protection against severe illness in both CEV and non-CEV individuals. However, 2- and 3-dose vaccinated CEV population still had a significantly higher relative risk of breakthrough COVID-19 hospitalisation compared with non-CEV individuals.

Interpretation

Vaccinated CEV population remains a higher risk group in the context of circulating Omicron variant and may benefit from additional booster doses and pharmacotherapy.

Funding

BC Centre for Disease Control and Provincial Health Services Authority.

Keywords: COVID-19, Omicron, Vaccination, Hospitalisation, Immunocompromised

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Medical comorbidities and advanced age are associated with higher risk of more severe COVID-19 disease, and immunosuppression is associated with lower response to vaccination. A higher rate of hospitalisation after SARS-CoV-2 infection in immunocompromised patients is a function of treatment- and/or disease-related immunosuppression. As a result of suboptimal humoral and cell-mediated response, additional vaccine doses and immunotherapy are provided to prevent viral escape and poor outcomes. However, there is limited information on COVID-19 hospitalisations rates among mostly vaccinated immunocompromised people in the Omicron era.

Added value of this study

This population-based study in a jurisdiction with a universal healthcare system reports recent, Omicron-era COVID-19 case hospitalisation rates among immunocompromised individuals compared to the general population, with stratification by age and vaccination status. The study shows that a third dose was associated with a lower risk of breakthrough hospitalisation regardless of the immune status. Among 3-dose vaccinated, immunocompromised individuals continued to experience a higher risk of breakthrough hospitalisation than non-immunocompromised individuals.

Implications of all the available evidence

This population-based study shows that while three doses of vaccination provides protection against breakthrough hospitalisation in immunocompromised individuals, they remain a higher risk group and may benefit from additional booster doses and pharmacotherapy.

Introduction

The Omicron variant of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is clinically and epidemiologically different from previous variants. It is associated with higher transmissibility, increased immune escape, and less severe COVID-19 illness.1 During the Omicron wave in England, a lower proportion of COVID-19 hospitalisations were admitted primarily for COVID-19 compared to the Delta wave, where incidental diagnoses were less common.2 British Columbia (BC) is a province in Canada (population 5.2 million) where about 90% of individuals over 18 were vaccinated with at least 2 doses as of January 7th 2022. The majority of the population received mRNA vaccines ((BNT162b2 [Pfizer-BioNTech] or mRNA-1273 [Moderna]). The first case of Omicron was identified in BC on 30 November 2021, and by end of December 2021, it became the dominant strain in BC.3

While vaccination is shown to be protective against severe outcomes from COVID-194,5 in the general population, such as hospitalisations and deaths, people with compromised immune systems may produce less robust cell-mediated immunity,6 and lower antibody levels, which may also decline faster over time.7,8 With previous variants, immunocompromised patients have fared worse clinically, but there is limited epidemiological information on COVID-19 severe outcomes during Omicron-era among immunocompromised populations. A recent study in the US found increased risk of breakthrough infection among immunocompromised individuals, independent of age, sex, and other comorbidities.9

Throughout 2021 in BC, clinically extremely vulnerable (CEV) individuals,10 were prioritised for early vaccination against COVID-19. CEV individuals were further classified into three groups, depending on the pathophysiology and severity of conditions: severely immunocompromised (CEV Group 1), moderately immunocompromised (CEV Group 2), and complex conditions that were not immunocompromising but had a very high risk of hospitalisation from COVID-19 (CEV Group 3).

A variety of therapeutics such as antivirals and monoclonal antibodies have been approved for treatment in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 and became available in Canada in early 2022. At the time, emerging evidence suggested that the heavily mutated Omicron variant lead to a decrease in neutralising activity of many monoclonal antibodies and may be responsible for the decreased effectiveness.11 Further, antiviral treatments are costly, often available in limited supply and/or have the potential to cause adverse effects and drug–drug interactions. Therefore, it was important to accurately characterise the baseline epidemiological risk of severe disease of the intended recipients of these agents in the context of mostly vaccinated population and Omicron being the dominant circulating variant.

In this study, we compare case hospitalisation rates among CEV and non-CEV individuals by age and vaccination status as part of the surveillance program at BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC). We also calculate the relative risk of breakthrough hospitalisations among vaccinated CEV vs non-CEV individuals during the first Omicron wave. This analysis contributed to clinical and policy decisions, weighing the absolute benefit versus risk of pharmacotherapy, and determining which patients should be prioritized for treatment.

Methods

Data sources

COVID-19 cases and hospitalisations

Data for COVID-19 cases and hospitalisations among adults aged 18 years and over were accessed from the BC Regional Health Authority COVID-19 Case Linelist Database. This dataset included all lab-confirmed, lab-probable, and epi-linked COVID-19 cases reported to the BCCDC by all five regional health authorities (HAs) in the province. Detailed case definitions can be found on BCCDC website.12 This dataset also contained information on hospitalisations among these cases, reported as any case admitted to a hospital for at least an overnight stay, for reasons directly or indirectly related to their COVID-19 infection, and with no period of complete recovery between illness and admission. The data also include information on personal health number (PHN), age, sex, regional health authority of residence, and index date, defined as symptom onset date; or earliest lab collection or result date if symptom onset date is not available; or public health case reported date if neither was available.

COVID-19 vaccination

Data for COVID-19 vaccination were included from the Provincial Immunisation Registry (PIR), which recorded all COVID-19 vaccines administered in BC,13 with information of the dose number, date of administration, trade name of the vaccine, as well as the recipients’ PHN, age, sex and regional health authority of residence.

Vaccination status of the COVID-19 cases and hospitalisations at the time of infection was derived after linking vaccination data with the case linelist. It was defined as follows, and consistent with the definitions used for breakthrough case surveillance,14 by BCCDC:

Vaccinated, 3 doses: 14 days and more after administration of third dose; Vaccinated, 2 doses: 14 days and more after administration of second dose AND less than 14 days after administration of third dose; Vaccinated, 1 dose: 21 days or more after administration of first dose AND less than 14 days after administration of second dose; Unvaccinated: no vaccination record OR less than 21 days after administration of first dose.

A small fraction of the BC population received the Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) vaccine (0.001%). They were classified as “vaccinated, 2 doses” 21 days after first dose.

CEV classification

We used January 2022 version of the list of PHNs for individuals with CEV classification extracted by Provincial Health Services Authority. CEV individuals were defined using data-driven approach by National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) having any of the underlying medical conditions listed in Table S1, and further classified into three groups: Group 1 contains severely immunocompromised patients such as those with actively treated haematological malignancies, stem cell or solid organ transplant recipients; Group 2 includes moderately immunocompromised patients such as those with solid tumours, advanced HIV, or receiving certain immunosuppression therapies; Group 3 includes complex conditions associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes such as cystic fibrosis, developmental and intellectual disabilities and insulin-requiring diabetes. These individuals were identified primarily from their health care service records, and more detailed information about the definition and identification can be found elsewhere.15

Data linkage and inclusion

Almost every resident of BC has public-funded healthcare service coverage and holds a unique PHN. Data on reported COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and vaccinations, as well as CEV classification were linked by PHN.

Data on COVID-19 cases with an index date between January 7, 2022 and March 14, 2022 and hospitalisations with an admission date within two weeks of index date were included. Cases and hospitalisations were excluded if (1) age was unknown; or (2) cases were classified as re-infected according to the Public Health Reporting Data Warehouse reinfection algorithm; or (3) the surveillance health authority was recorded as “out of country”; or (4) residents or patients associated with an acute care facility, long term care facility or assisted living facility reportable outbreak (for hospitalisation only); or (5) they had an admission date 3 or more days before the surveillance episode date, thus reflecting possible nosocomial infections. During this time period, the vast majority of COVID-19 infections were due to the Omicron variant.16

Data analysis

Case hospitalisation rate

A positive COVID test is the starting point and the basis for determining treatment eligibility and represents a practical reference for that purpose. To compare CEV and non-CEV groups, we calculated and visualised case hospitalisation rates stratified by age group, vaccination status and CEV status. Case hospitalisation rate for a given stratum was calculated as the number of hospitalisations for COVID-19 within two weeks of the index date divided by the number of positive COVID-19 cases in each stratum.

A known challenge of COVID-19 statistics in Omicron era is that not all hospitalised patients with a positive COVID-19 test are hospitalised primarily for COVID-19. To address this challenge, we applied an adjustment factor—an estimate of what proportion of hospitalisations in a given stratum were primarily due to COVID-19, based on a retrospective chart review (details can be found in Supplementary material). Adjusted case hospitalisation rate in a given age/vaccine status/CEV status stratum was calculated as follows:

It is important to note that case hospitalisation metric overestimates the true infection hospitalisation rate because it only relies on reported COVID-19 cases in the denominator and does not take into account all other cases/infections in the community that were not tested and/or reported. However, it still illustrates critical patterns across age, vaccination, and CEV status.

Matched analysis

Some potential confounding factors are not accounted for in the case hospitalisation rate comparison above. For example, CEV individuals were prioritised for vaccination in BC throughout the pandemic, and they generally received their vaccination earlier than the non-CEV population. The effectiveness of the vaccine against hospitalisation changes over time.17 In addition, CEV individuals were also more likely to receive the Moderna vaccine than other brands of vaccines, as per the national guidelines,18 and the protection from vaccine might vary by trade brands.19,20 These factors, along with age, sex and geographic region, were potentially associated with both the risk of hospitalisation due to COVID-19, and the likelihood of being in the CEV group.

To account for these potential confounding factors when comparing with a non-CEV population, a matched analysis was conducted with a focus on breakthrough hospitalisations among vaccinated individuals. Matching avoids the parametric assumptions of regression modelling and can therefore be used in a situation where clinical knowledge of the disease pathways is still emerging. For each CEV individual vaccinated with 2 doses or 3 doses, five non-CEV individuals were randomly chosen from the PIR who received the same number of doses, and had the same sex, 10-year age group, administration date of the last dose, trade name of the vaccine, and health authority of residence. Cumulative counts of hospitalisations during the study period were divided by the vaccinated population of CEV and non-CEV individuals to calculate the cumulative incidence. Risk ratios were calculated as the ratio between the cumulative incidence of the CEV groups with that of the non-CEV group, stratified by vaccination status.

We also performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding individuals who were treated with Paxlovid or Sotrovimab during the study period, to account for the potential impact of these treatments on the subsequent hospitalisations.

This work was carried out under BCCDC's mandate to perform population health surveillance and falls under the Behavioural Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia (approval # H20-02097). All data processing, analysis (including random selection of matched controls in the matched analysis), and visualisation were done in R (Version 4.1.2). The confidence intervals for cumulative incidence were calculated using exact method for Poisson rates, and the risk ratios were calculated using unconditional maximum likelihood estimation (Wald method), with the R package epitools.

Role of the funding source

The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the analysis or interpretation of data, or in the writing of the manuscript; this work represents opinion of the authors only.

Results

Among the 311,818 adult CEV individuals in BC, 5591 CEV individuals had a reported COVID-19 infection during the study period. Of these cases among CEV individuals, 1153 were hospitalised. The CEV population was notably older than non-CEV population (Table 1). The majority of CEV COVID-19 cases were in Group 2 (41%) or Group 3 (49%), reflecting the higher proportion of these individuals in the study population compared to CEV Group 1. Among CEV individuals, vaccine coverage was 88% for 2 doses and 72% for 3 doses at the end of the study period. Approximately 9% of COVID-19 cases and 17% of hospitalised cases among CEV individuals did not receive any type of COVID-19 vaccination as per their record.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the cohorts of study population, COVID-19 positive cases and hospitalization associated with COVID-19 by CEV status.

| Study population | CEV Group 1 14,941 (100)a |

CEV Group 2 122,202 (100) |

CEV Group 3 174,675 (100) |

Non-CEV general population 4,081,457 (100) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccination statusb | ||||

| Unvaccinated | 1001 (7) | 8199 (7) | 22,967 (13) | 285,729 (7) |

| 1 dose | 169 (1) | 1253 (1) | 2708 (2) | 112,004 (3) |

| 2 doses | 1747 (12) | 16,083 (13) | 34,062 (20) | 1,396,053 (34) |

| 3 doses | 12,024 (80) | 96,667 (79) | 114,938 (66) | 2,287,671 (56) |

| Median age (IQR) | 64 (23) | 64 (30) | 68 (33) | 45 (31) |

| Male (%) | 7925 (53) | 46,366 (38) | 907,12 (52) | 2,007,850 (49) |

| Among the vaccinated | 13,940 (100) | 114,003 (100) | 151,708 (100) | 3,795,728 (100) |

| Median (IQR) days since last doseb | 153 (137,173) | 147 (135,155) | 90 (67,133) | 91 (56,204) |

| Last dose as Moderna | 8214 (59) | 69,549 (61) | 80,732 (53) | 1,770,931 (47) |

| Health authority | ||||

| Fraser | 4705 (34) | 38,419 (34) | 53,910 (36) | 1,392,222 (37) |

| Interior | 2564 (18) | 22,461 (20) | 30,859 (20) | 578,126 (15) |

| Northern | 734 (5) | 5988 (5) | 10,545 (7) | 186,952 (5) |

| Vancouver Coastal | 3327 (24) | 24,149 (21) | 27,662 (18) | 989,724 (26) |

| Vancouver Island | 2604 (19) | 22,950 (20) | 28,676 (19) | 640,581 (17) |

| Unspecified | 6 (<1) | 36 (<1) | 55 (<1) | 8122 (<1) |

| COVID-19 positive cases | CEV Group 1 560 (100) |

CEV Group 2 2316 (100) |

CEV Group 3 2715 (100) |

Non-CEV general population 34,993 (100) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccination status | ||||

| Unvaccinated | 28 (5) | 155 (7) | 321 (12) | 4278 (12) |

| 1 dose | 5 (1) | 42 (2) | 55 (2) | 777 (2) |

| 2 doses | 102 (18) | 438 (19) | 1003 (37) | 17,608 (50) |

| 3 doses | 425 (76) | 1681 (73) | 1336 (49) | 12,330 (35) |

| Median age (IQR) | 64 (23) | 64 (30) | 68 (33) | 45 (31) |

| Male (%) | 309 (55) | 956 (41) | 1290 (48) | 13,353 (38) |

| Hospitalisations associated with COVID-19 | CEV Group 1 188 (100) |

CEV Group 2 368 (100) |

CEV Group 3 597 (100) |

Non-CEV general population 2447 (100) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccination status | ||||

| Unvaccinated | 13 (7) | 54 (15) | 132 (22) | 807 (33) |

| 1 dose | 3 (2) | 17 (5) | 20 (3) | 105 (4) |

| 2 doses | 39 (21) | 90 (24) | 236 (40) | 970 (40) |

| 3 doses | 133 (71) | 207 (56) | 209 (35) | 565 (23) |

| Median age (IQR) | 68 (13) | 70 (20) | 73 (22) | 67 (36) |

| Male (%) | 113 (60) | 181 (49) | 332 (56) | 1251 (51) |

Note: Number of individuals (and percent of cohort) are reported unless otherwise indicated.

Status as of March 14, 2022.

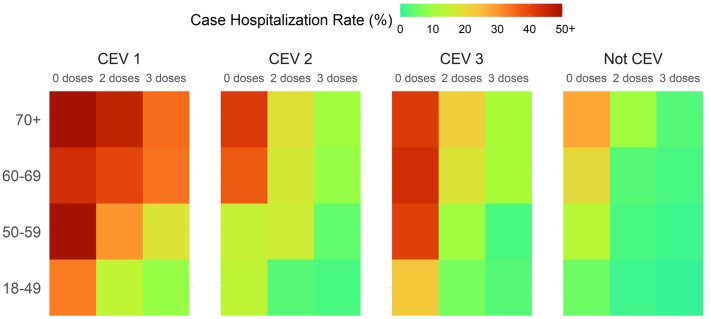

Fig. 1 illustrates adjusted case hospitalisation rates across CEV status, age group and vaccination status, with a clear gradient across the subgroups. Higher rates of hospitalisation are observed among older or/and unvaccinated people in all subgroups. It also illustrates the lower rates among those who received 3 doses of vaccine, both in CEV and non-CEV populations. Individuals in CEV Group 1, who were the most immunocompromised, had much higher case hospitalisation rates compared with other CEV and non-CEV groups in the same age groups and with same vaccination status. Because of much higher rates among the CEV Group 1 population, the colour scheme is heavily skewed towards that group, making it harder to see the age- and dose-gradient in the non-CEV population. It is critical to note that the result represents hospitalisations among reported cases only and thus greatly overestimates the true infection hospitalisation rate among all infections that actually occurred.

Fig. 1.

Heat map of the hospitalisation rate (%) among reported COVID-19 cases by age group and their CEV and vaccination status.

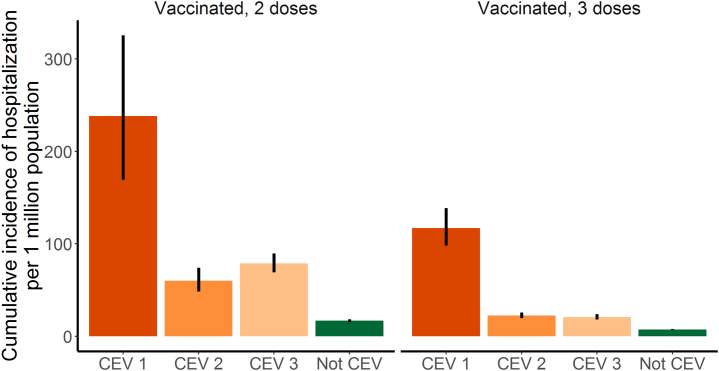

In the matched analysis where we accounted for several potential confounding factors, CEV Group 1 had the highest cumulative breakthrough hospitalisation incidence over the study period, with the risk ratio (RR) of 14.2 (95% CI: 10.2–19.7) and 15.8 (13.2–19.0) times that among matched non-CEV individuals for 2- and 3-dose recipients, respectively (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The RRs for CEV Group 2 vs matched non-CEV was 3.6 (95% CI 2.9–4.5) and 3.0 (95% CI 2.6–3.5) for 2- and 3-dose recipients, respectively. The RRs for CEV Group 3 vs matched non-CEV was 4.7 (95% CI 4.0–5.5) and 2.8 (95% CI 2.4–3.3) for 2- and 3-dose recipients, respectively. For both CEV and non-CEV individuals, cumulative incidence of hospitalisations was significantly higher among 2 dose recipients compared to 3 dose recipients. Exclusion of individuals who received Paxlovid or Sotrovimab (n = 821) revealed minimal impact on the results (data not shown).

Table 2.

Cumulative incidence of hospitalisations and risk ratios by CEV status in the matched analysis.

| Number of hospitalisations | Population at mid-point | Cumulative incidence per 1 million (95% CI) | Risk ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccinated 2 doses | ||||

| Not CEV | 387 | 230,690 | 16.8 (15.1–18.5) | Ref. |

| CEV Group 3 | 236 | 29,922 | 78.9 (69.1–89.6) | 4.7 (4.0–5.5) |

| CEV Group 2 | 90 | 15,420 | 60.2 (48.4–74) | 3.6 (2.9–4.5) |

| CEV Group 1 | 39 | 1638 | 238.1 (169.3–325.5) | 14.2 (10.2–19.7) |

| Vaccinated 3 doses | ||||

| Not CEV | 721 | 974,645 | 7.4 (6.9–8.0) | Ref. |

| CEV Group 3 | 209 | 100,445 | 20.8 (18.1–23.8) | 2.8 (2.4–3.3) |

| CEV Group 2 | 206 | 91,995 | 22.4 (19.4–25.7) | 3.0 (2.6–3.5) |

| CEV Group 1 | 133 | 11,370 | 117.0 (97.9–138.6) | 15.8 (13.2–19.0) |

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence of COVID-19 hospitalisations per million among vaccinated immunocompromised (CEV) individuals compared to matched non-immunocompromised (Not CEV) controls during the first Omicron wave (Jan–March 2022) in British Columbia, Canada.

Discussion

In the context of Omicron predominance, we found that a third vaccine dose with mRNA vaccine offered additional protection against severe illness in both CEV and non-CEV individuals. However, 2- and 3-dose vaccinated CEV population still had a significantly higher relative risk of breakthrough hospitalisation compared with non-CEV individuals.

Most clinical trials of COVID-19 vaccines excluded or underrepresented people with compromised immune systems, resulting in a limited amount of evidence on the impact of vaccination on this population. Here, we provide real-world evidence on hospitalisation rates amid the period when Omicron was the dominant variant of concern. As Omicron is more prone to immune escape but associated with a lower likelihood of severe disease, these findings characterise COVID-19 epidemiology in the current pandemic context before treatment became widely available. Previous epidemiological studies in organ transplant recipients who received three doses of vaccination showed an improvement in the serum neutralizing activity against the Omicron variant. Our study provides evidence from real-world observations, in a more comprehensive immunocompromised population.

We also show that for each immune status, risk of hospitalisation retains a strong independent age-gradient pattern, leading to much higher likelihood of severe disease among older individuals. This finding is consistent with previous studies in BC and other jurisdictions,21,22 which have shown age as one of the major predictors of severe COVID-19.

Among CEV population, CEV Group 1 saw significantly higher hospitalisation rate compared with CEV Group 2 and Group 3. This is expected, because CEV Group 1 includes the most immunocompromised people with higher baseline risk of hospitalisation rate and higher rate of vaccine failure.23,24 The CEV Groups 2 and 3 represent a wide range of conditions treated with immunosuppressive medications. The CEV Group 3 is a broader umbrella in which some members may be minimally or not immune suppressed, but remain at risk for severe disease. While we did not observe notable differences between the two groups, it is important to emphasize that they include a heterogeneous mix of conditions and there is variation in the risk of severe outcomes between different conditions.

Various therapeutic agents shown to reduce disease progression and prevent hospitalisation in clinical trials are now available for early treatment of COVID-19. Selecting the appropriate candidates for therapy is challenging as these trials were conducted in unvaccinated individuals before the emergence of Omicron and had low external generalizability to the current pandemic situation, when most of the adult population is vaccinated and the dominant variant is Omicron. These treatments are also not harmless, with the key drug, Paxlovid, having multiple drug interactions and potentially substantial side effects. This study shows key relationships between age, vaccine status, and immune status to help prioritize patients at highest risk of severe disease in whom treatments may have the most benefit. In British Columbia, CEV populations have been prioritised for treatment on the basis of these findings and other factors and considerations.

Our study has a number of strengths. It is one of the first population-based observational studies reporting breakthrough hospitalisations specific to immunocompromised individuals while adjusting for potentially incidental findings of COVID-19, a key feature that distinguishes Omicron-era epidemiology from prior variants. Our analysis was conducted using data in a large universal health care system with a diverse and stable population, benefitting from comprehensive capture of COVID-19 vaccinations, testing, and disease outcomes. In addition to providing relative metrics, we also provide absolute metrics, which allows for a concrete quantification of risk that is necessary for clinical, operational, and logistical aspects of treatment eligibility decision making.

There are several limitations. Due to changes in immunocompromising conditions or medications, there is some risk of misclassification to and from the study groups as some people may not have met the criteria for CEV definitions used in this study throughout the whole study period, but we expect this number to be small. Rapid antigen self-test for COVID-19 have become more widely available in 2022, but these test results were not captured in the case dataset used for this study. PCR testing rates were higher among CEV individuals compared with non-CEV individuals, reflecting, at least in part, BC's “test-to-treat” strategy to navigate appropriate use of limited antiviral treatment for high-risk COVID-19 positive cases. This means that otherwise younger and healthy adults would not have been eligible for publicly funded PCR testing, while those at higher risk, including CEV individuals, were prioritised. As such, results likely overestimate case hospitalisation rate in the non-CEV group; the relative difference in case hospitalisation rates between CEV and non-CEV populations is likely even greater. Case hospitalisation rate calculations do not account for time since last vaccine dose, but we address this limitation in the matched analysis. In the matched analysis, we assumed equal risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in the matched CEV and non-CEV individuals, but this assumption may not always hold. The non-CEV population who were vaccinated at the same time as the CEV population might have some special characteristics for prioritization, such as being health care workers, which may present different risk of exposure to the virus than the general population. Although this study was done with the entire population of a well-defined geographic region, it is possible that we missed some individuals who were not in the province for the full study period or misclassified vaccination status for those who received vaccination outside of the province. We were limited in our ability to stratify results by sex in order to conserve statistical power. Information on ethnicity of the study population was not available.

The higher level of breakthrough hospitalisations among CEV individuals who received 3 doses compared with non-CEV individuals suggests that the CEV population remains a higher risk group and may benefit from additional booster doses and pharmacotherapy. Our findings also highlight the need to continuously monitor health outcomes among immunocompromised individuals. Further studies should assess the risk-benefit of pharmacotherapy following infection among the CEV and non-CEV populations.

Contributors

KS conceived the study idea. KS, CM, and JAY designed the study. CM and JAY performed the data analyses. CM and JAY had access to raw data. TB performed the literature review and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JP and JMG provided clinical consultations. All authors contributed to revising or critically reviewing the article. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data sharing statement

Data is used for public health surveillance and cannot be shared by the authors. Data access request should be made to the data stewards (BC Ministry of Health and Provincial Health Services Authority) as per existing processes. R codes for data processing, analysis and visualization can be shared upon request.

Declaration of interests

Jennifer M. Grant acted as expert witness in a federal court case regarding vaccination mandates for air travel.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Joanne Shum, Alexandra Flatt, and Dr. Maureen O'Donnell for providing CEV information and supporting this work. We also acknowledge Dr. Hind Sbihi and BC Public Health Laboratories for providing testing data. We thank Dr. Felicity Clemens for statistical consultation. Our gratitude also goes to the individuals involved in health authority chart review and analysis to produce estimates of the proportion of hospitalisations primarily due to COVID-19: Sara Miles, Monica Durigon, Mei Chong, Marsha Taylor, Dr. Caren Rose, Vancouver Coastal Health Public Health Surveillance Unit, Dr. Naveed Janjua and Dr. Jat Sandhu.

Footnotes

Sources of support: This study was funded by BC Centre for Disease Control and Provincial Health Services Authority.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2023.100461.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Nyberg T., Ferguson N.M., Nash S.G., et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B. 1.1. 529) and delta (B. 1.617. 2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet. 2022;399(10332):1303–1312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00462-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS COVID-19 hospital activity. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/covid-19-hospital-activity/ [cited 2022 Apr 13]. Available from:

- 3.BC Centre for Disease Control . 2022. BC COVID-19 data.http://www.bccdc.ca/health-info/diseases-conditions/covid-19/data#variants Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Funk C.D., Laferrière C., Ardakani A. Target product profile analysis of COVID-19 vaccines in phase III clinical trials and beyond: an early 2021 perspective. Viruses. 2021;13(3):418. doi: 10.3390/v13030418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordström P., Ballin M., Nordström A. Risk of infection, hospitalisation, and death up to 9 months after a second dose of COVID-19 vaccine: a retrospective, total population cohort study in Sweden. Lancet. 2022;399(10327):814–823. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00089-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prendecki M., Clarke C., Edwards H., et al. Humoral and T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients receiving immunosuppression. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(10):1322–1329. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun J., Zheng Q., Madhira V., et al. Association between immune dysfunction and COVID-19 breakthrough infection after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(2):153–162. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.7024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galmiche S., Luong Nguyen L.B., Tartour E., et al. Immunological and clinical efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in immunocompromised populations: a systematic review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28(2):163–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belsky J.A., Tullius B.P., Lamb M.G., Sayegh R., Stanek J.R., Auletta J.J. COVID-19 in immunocompromised patients: a systematic review of cancer, hematopoietic cell and solid organ transplant patients. J Infect. 2021;82(3):329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.BC COVID-19 Therapeutic Committee (CTC) 2022. Practice Tool #2 – definitions of CEV/immunosuppressed.http://www.bccdc.ca/Health-Professionals-Site/Documents/COVID-treatment/PracticeTool2_CEVCriteria.pdf [cited 2022 Mar 28]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tada T., Zhou H., Dcosta B.M., et al. Increased resistance of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant to neutralization by vaccine-elicited and therapeutic antibodies. EBioMedicine. 2022;78:103944. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bc Centre for Disease Control COVID-19 (Novel Coronavirus) http://www.bccdc.ca/health-professionals/clinical-resources/case-definitions/covid-19-(novel-coronavirus [cited 2022 Mar 28]. Available from:

- 13.Provincial Health Services Authority [creator] Provincial Immunizations Registry, Provincial Public Health Information Systems; 2020. COVID-19 vaccination data. [Google Scholar]

- 14.BCCDC COVID-19 Regional Surveillance Dashboard Data notes 2022. https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/bccdc/viz/BCCDCCOVID-19RegionalSurveillanceDashboardArchived/Introduction [cited 2022 Mar 28]. Available from:

- 15.Health Canada Immunization of immunocompromised persons: Canadian Immunization Guide, 2007. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-3-vaccination-specific-populations/page-8-immunization-immunocompromised-persons.html [cited 2022 Mar 28]. Available from:

- 16.Health Canada COVID-19 daily epidemiology update 2020. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/epidemiological-summary-covid-19-cases.html#VOC [cited 2022 Mar 28]. Available from:

- 17.Andrews N., Tessier E., Stowe J., et al. Duration of protection against mild and severe disease by COVID-19 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):340–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2115481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) Recommendations on the use of COVID-19 vaccines. 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-26-covid-19-vaccine.html#t3 Available from:

- 19.Self W.H., Tenforde M.W., Rhoads J.P., et al. Comparative effectiveness of Moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech, and Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) vaccines in preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations among adults without immunocompromising conditions — United States, March–August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(38):1337–1343. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7038e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bajema K.L., Dahl R.M., Evener S.L., et al. Comparative effectiveness and antibody responses to Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines among hospitalized veterans — five veterans affairs medical centers, United States, February 1–September 30, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(49):1700–1705. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7049a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Velásquez García H.A., Wilton J., Smolina K., et al. Mental health and substance use associated with hospitalization among people with COVID-19: a population-based cohort study. Viruses. 2021;13(11):2196. doi: 10.3390/v13112196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yek C., Warner S., Wiltz J.L., et al. Risk factors for severe COVID-19 outcomes among persons aged ≥18 years who completed a primary COVID-19 vaccination series — 465 health care Facilities, United States, December 2020–October 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(1):19–25. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7101a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehrabi Nejad M.M., Moosaie F., Dehghanbanadaki H., et al. Immunogenicity of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines in immunocompromised patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res. 2022;27(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s40001-022-00648-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fung M., Babik J.M. COVID-19 in immunocompromised hosts: what we know so far. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(2):340–350. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.