Abstract

The CSE1L gene, the human homologue of the yeast chromosome segregation gene CSE1, is a nuclear transport factor that plays a role in proliferation as well as in apoptosis. CSE1 and CSE1L are essential genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and mammalian cells, as shown by conditional yeast mutants and mammalian cell culture experiments with antisense-mediated depletion of CSE1L. To analyze whether CSE1L is also essential in vivo and whether its absence can be compensated for by other genes or mechanisms, we have cloned the murine CSE1L gene (Cse1l) and analyzed its tissue- and development-specific expression: Cse1l was detected at embryonic day 7.0 (E7.0), E11.0, E15.0, and E17.0, and in adults, high expression was observed in proliferating tissues. Subsequently, we inactivated the Cse1l gene in embryonic stem cells to generate heterozygous and homozygous knockout mice. Mice heterozygous for Cse1l appear normal and are fertile. However, no homozygous pups were born after interbreeding of heterozygous mice. In 30 heterozygote interbreeding experiments, 50 Cse1l wild-type mice and 100 heterozygotes were born but no animal with both Cse1l alleles deleted was born. Embryo analyses showed that homozygous mutant embryos were already disorganized and degenerated by E5.5. This implicates with high significance (P < 0.0001, Pearson chi-square test) an embryonically lethal phenotype of homozygous murine CSE1 deficiency and suggests that Cse1l plays a critical role in early embryonic development.

The cellular apoptosis susceptibility (official symbol, CSE1L) gene is the human homologue of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome segregation gene CSE1 (4, 5). The CSE1L gene was originally identified in a genetic screen for genes that affect the sensitivity of breast cancer cells towards toxins and immunotoxins that are used in experimental cancer therapy. In yeast, CSE1 mutations cause a chromosome missegregation phenotype, defects in cyclin B degradation, and arrest in mitosis (9, 18). The high homology of CSE1L to the cell cycle gene CSE1 and the observation that CSE1L is highly expressed in proliferating cells but is expressed only at low levels in most quiescent cells and tissues suggest that CSE1L acts not only in apoptosis but also in the cell cycle and cellular proliferation. The N-terminal domain of CSE1L is homologous to the Ran-binding domain in β importin (6, 8). It has also been reported that CSE1L is a transport factor that is necessary for recycling of importin α from the nucleus to the cytosol (11). This recycling of importin α is essential for nuclear transport of a variety of proteins, among them proteins that are required for mitosis (10, 13) or apoptosis. In yeast, CSE1 is also required for the export of the small ribosomal subunit from the nucleus (14). These reports may explain the pleiotropic phenotype of CSE1L in proliferation and apoptosis. Since CSE1L is associated with proliferation as well as apoptosis, we anticipated that it might be involved in normal development and cancer. Evidence for association of CSE1L with the development of cancer is provided by its high expression in tumor cells and the amplification of the human CSE1L gene in aggressive breast tumors (2, 4, 17).

In yeast and in mammalian cells, CSE1 and CSE1L are essential genes. Yeast mutants display conditional lethal phenotypes (18), and antisense-mediated depletion of CSE1L results in mitotic arrest and subsequent cell death in mammalian cell culture experiments (15). However, it has been frequently observed that genes that were originally considered to be essential as a result of in vitro experiments turned out to be compensable when deleted in vivo, i.e., in murine knockout models (7, 16). To investigate the precise biological function of CSE1L in vivo and whether other genes or mechanisms can compensate for its absence, we disrupted the mouse CSE1L gene (Cse1l) in embryonic stem (ES) cells via homologous recombination. We are able to generate heterozygous mice bearing a single copy of the Cse1l gene but unable to obtain a homozygous knockout mouse because the targeting process resulted in early embryonic lethality. Heterozygous mice appear normal after 15 months, while homozygous mutants die during early embryonic development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and sequencing of Cse1l cDNA.

The human CSE1L cDNA sequence was used to identify the mouse expressed sequence tags (ESTs) for the Cse1l gene by the BLAST program, and the ESTs were aligned with FASTA. Most of the mouse ESTs for the CSE1L gene were centered on the 3′ end of the gene. Several PCR primers were then designed from the EST sequence information to perform rapid amplification of cDNA ends PCR using marathon ready mouse testis cDNA (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) as a template. PCR-amplified fragments were then cloned in Topo TA cloning vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.), and DNA sequences were determined with an ABI 373 DNA sequencer and Applied Biosystem's Dye terminator kit.

Construction of targeting vectors.

A 129 SVJ mouse genomic Lambda FIX II phage library (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) was screened with a probe derived from the 3′ end of the Cse1l cDNA. A clone containing an insert of approximately 12 kb was subcloned in pBluescript II S/K plasmid, and the restriction map of the insert was determined. The locations of exons were mapped by Southern blotting. The precise exon-intron boundaries were determined by DNA sequencing. First, a 2.5-kb NotI-XbaI fragment was inserted into the NotI-XbaI site of pJMM4 vector (1). The resulting vector was then linearized with EcoRI restriction enzyme and gel purified. A 5-kb EcoRI fragments was then cloned. As a result, a 1.5-kb XbaI-EcoRI fragment consisting of the entire exon 23 (encoding amino acids 817 to 866) and part of introns W and X (3) was deleted in the final vector and replaced by a neo marker. The final clone was designated pJMM5.6.

Transfection and generation of ES cells heterozygous for Cse1l.

About 2.0 × 107 ES cells were electroporated with 20 μg of the targeting plasmid pJMM5.6 linearized with NotI. After 18 to 24 h, 250 μg of G418 per ml and 2 μM ganciclovir was added and kept in this selection medium for 3 to 4 days. After the selection, individual neomycin-resistant clones were picked and grown, and 105 of these clones were analyzed. Genomic DNA was extracted (12), digested with EcoRV and BamHI, run on a 0.9% agarose gel, and blotted onto BioDyne membrane (Life Technology, Gaithersburg, Md.) for Southern analysis. The membranes were hybridized with a radiolabeled 3′ probe which was outside of the targeting region (3′ EcoRI fragment). The wild-type allele gives a band of 13 kb, whereas a band of 10 kb represents the correctly targeted allele. Several clones were identified as correctly targeted and were reanalyzed by using the 3′ internal probe.

Generation of chimeric mice and Cse1l heterozygous mice.

Five of these clones were then prepared and injected into blastocysts for generation of chimeric mice. Chimeric males were crossed with C57BL/6 females, and the agouti-colored offspring were analyzed for transmission of the Cse1l mutation. Heterozygous animals were intercrossed to generate homozygous mutated animals. Wild type siblings obtained from the offspring of these crosses were used as control animals in the experiments. All animal work was performed in accordance with guidelines established by the National Institute of Health.

Breeding and genotyping.

Genomic DNA was extracted from the tail tips of 2-week-old mice to determine the genotypes of the pups resulting from breeding of chimeric and heterozygous Cse1l mice. To genotype by PCR, four primers were used: T226-T241 amplifier a 220-bp fragment in wild-type and heterozygous alleles and T239-T240 amplifies a 350-bp fragment in heterozygous and homozygous mutant alleles. The sequences of the primers used are as follows: T226, AAG GTA TCT GGG AAC GTG GA; T241, TCC AGT GGA GAA GCC CAA GAG C; T239, TGC TCT GAT GCC GCC GTG TTC C; and T240, CGA TGT TTC GCT TGG TGG TCG A.

For genotyping of the embryo, time pregnancies were carried out after mating Cse1l heterozygous male and female mice. Uteri from embryonic day 7.5 (E7.5) and E8.5 pregnancies were isolated in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. Deciduae were dissected, snap-frozen on dry ice, and kept at −20°C until used for DNA extraction. To prepare serial sections of E5.5 embryos, whole uteri from E5.5 pregnancies were fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Finally, 5-μm-thick sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Northern hybridization.

Northern blots containing 2 μg of poly (A) mRNA from mouse tissues (Clontech) were hybridized with random-primed 32P-labeled Cse1l cDNA fragments under high-stringency conditions as described elsewhere (1). Briefly, membranes were prehybridized for more than 4 h in hybridization solution containing 50% formamide (Hybrisol I; Oncor, Gaithersburg, Md.) and hybridized for 15 h with probe at 45°C. The membranes were then rinsed in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), washed twice with 2× SSC–0.1% SDS at room temperature, and finally washed at 65°C in 0.2× SSC–0.1% SDS.

Histological analysis.

Wild type and Cse1l mutant mice were maintained in the same colony by following the appropriate animal care and handling guidelines. Fifteen mice from each group 3 months old) were euthanized by CO2 inhalation, and complete necropsies were performed. Different tissues from each animal were dissected out and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Sections (5 μm thick) were cut from the formalin-fixed tissues and stained with hematoxylin and cosin.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence for Cse1l has been submitted to GenBank under accession no. AF301152.

RESULTS

Mouse homologue of the CSE1 gene.

The coding regions of human CSE1L and yeast CSE1 are of approximately the same size, and their sequences are similar over their whole lengths with some small gaps. The overall homology is 59%, and in some portions the homology is >75% with 50% identity (4). The extensive homology between human and yeast genes indicates that the CSE1 genes from different species are very conserved and may have similar and essential functions. To determine the similarity of the mouse homologue of the CSE1 gene, we cloned Cse1l cDNA by rapid amplification of cDNA ends PCR using mouse testis cDNA as a template (see Materials and Methods). The nucleotide sequence of the Cse1l gene was determined. The deduced amino acid sequences of the Cse1l coding regions and CSE1L are identical in size, and their sequence identity is over 96% over their whole lengths (data not shown).

Expression of Cse1l in different tissues.

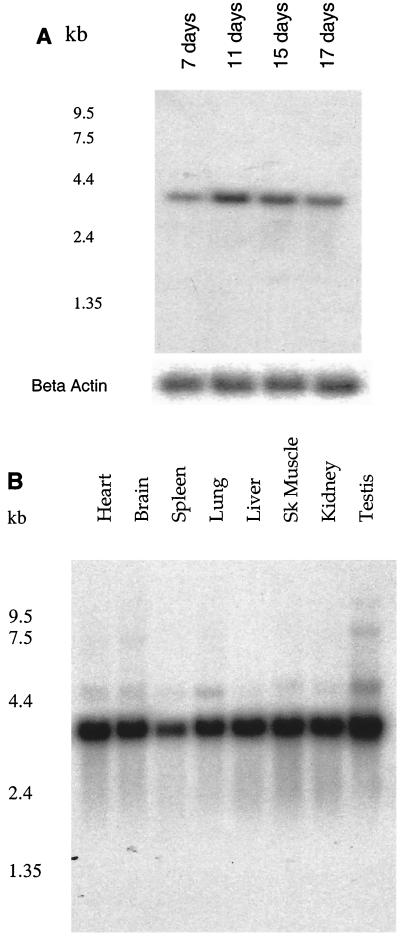

The extensive sequence homology demonstrates that the CSE1 genes are very conserved and have similar and important functions. Furthermore, analyses of the expression patterns of a gene during development and adulthood can provide valuable insights regarding its function. Therefore, we analyzed the expression of Cse1l in different developmental stages and various adult tissues by Northern hybridizations (Fig. 1). The 3.1-kb Cse1l transcript can be detected in the mRNA of mouse embryos from E7.0, and higher expression was observed on E11.0, E15.0, and E17.0 of mouse development (Fig. 1A). In adult tissues the expression of the Cse1l gene was predominant in most of the tissues tested, including testis, heart, brain, lung, liver, skeletal muscle, and kidney (Fig. 1B). However, the expression of Cse1l is lower in spleen than in other tissues tested. These data indicate that, like in humans, Cse1l is expressed in the mouse in a regulated manner in different tissues and that the functions of Cse1l in the different tissues are similar in humans and mice.

FIG. 1.

Tissue- and development-specific expression of the Cse1l transcript in mice. Northern blot analysis of Cse1l expression in developmental stages (A) and in eight adult tissues (B). The filters were obtained from Clontech and contained 2 μg of poly (A)+ RNA in each lane. Beta Actin, blots hybridized with the beta-actin probe; Sk Muscle, skeletal muscle.

Targeted inactivation of the mouse Cse1l gene.

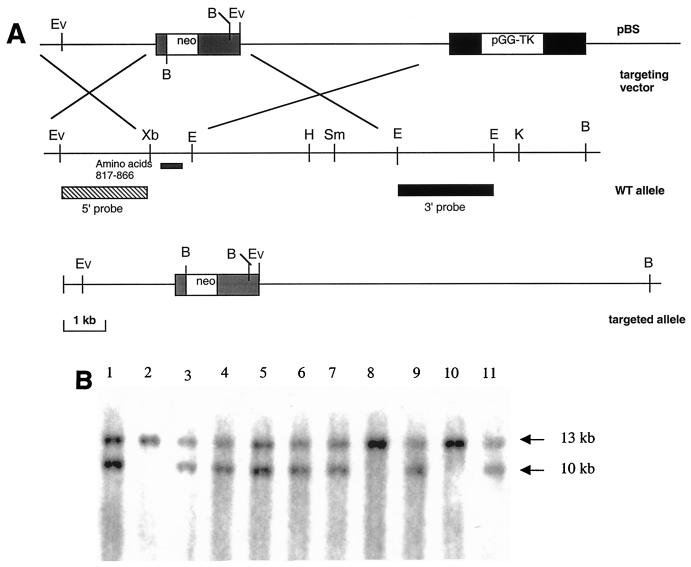

To assess the role of the Cse1l gene in mouse development and growth, we inactivated the Cse1l gene. A 12-kb isogenic genomic fragment containing exons 19 to 25 of the mouse Cse1l gene was isolated from a mouse genomic library (Stratagene). The genomic structure was determined by direct sequencing and restriction site mapping. The genomic fragment of mouse Cse1l was used to create the construct for homologous recombination in ES cells. The strategy used to construct the targeting vector is illustrated in Fig. 2A. As shown in Fig. 2A, a 1.5-kb XbaI and EcoRI fragment containing the entire exon 23 and part of introns W and X was replaced with a PGK-neo cassette. Of 125 ES cell clones analyzed by Southern analysis (Fig. 2B), 21 underwent homologous recombination. Five different Cse1l+/− ES cell clones were independently injected into blastocysts and gave rise to germ line-transmitting chimeric mice that were used to breed homozygous mutant progeny. Southern blot analysis was used to verify the transmission of the mutant allele through the germ line via chimera formation.

FIG. 2.

Targeted disruption of the Cse1l gene. (A) Diagram showing the genomic organization of Cse1l gene, the targeting vector, and the targeted allele after the homologous recombination. Restriction sites are indicated: B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; Ev, EcoRV; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; Sm, SmaI, and Xb, XbaI. The DNA fragments used for probe are indicated (5′ and 3′ probe). (B) Southern blot analysis of representative tail DNA samples derived from 2-week-old offspring of intercrosses between heterozygous Cse1l mice. The 13-kh band represents the wild-type allele, and the 10-kb band represents the targeted allele.

Phenotype of Cse1l heterozygous mice.

Several high-percentage chimeric male mice were obtained from the targeted ES cell injection into the C57BL/6 blastocysts. These chimeras appeared phenotypically normal (except for their skin color indicating chimerism), and the males were mated with C57BL/6 female mice for germ line transmission of the mutant allele. Heterozygous male and female mice were obtained from the germ line transmission. These heterozygotes were phenotypically normal and fertile, with no development of tumors or other abnormalities for up to 16 months. Histological analysis of several organs from wild-type and heterozygous adult mice of matched age also showed no detectable phenotype in the Cse1l heterozygous mice (data not shown).

Cse1l−/− is embryonically lethal.

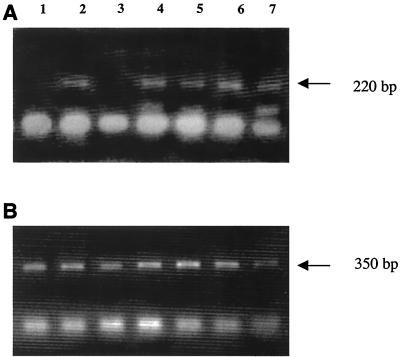

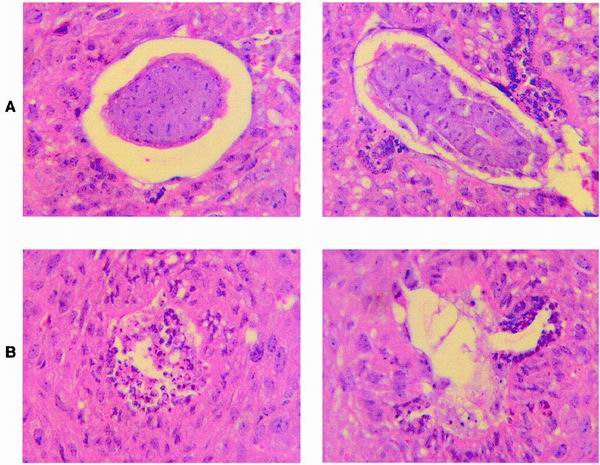

Heterozygous Cse1l mice were interbred in an attempt to generate homozygous Cse1l knockouts. However, the genotype analysis of mice arising from interbred Cse1l heterozygous mice failed to show any homozygous null Cse1l mice in over 150 offspring that were analyzed. Of the progeny from heterozygote intercrosses, 30% (n = 49) were wild type and 70% (n = 101) were heterozygous for the Cse1l gene. None was homozygous, although approximately 50 homozygous knockout offspring would have been expected, provided that there was no negative selection for this genotype. These results indicate with high significance (P < 0.0001, Pearson chi-square test) that loss of Cse1l function is associated with an embryonically lethal condition. The fact that the frequency of observed heterozygotes corresponds to the expected numbers (without assumption of negative effects) indicates that the level of Cse1l in heterozygotes is adequate to permit normal growth and development throughout life. To determine the time of embryonic lethality in homozygously deleted embryos, embryos from heterozygote intercrosses were collected at different times of gestation. DNAs from the isolated embryos were extracted and then genotyped by Southern blot hybridization. No homozygous mutant embryos were recovered at or after E8.5, and the percentage of resorptions at this time point was as high as 25%. At E7.5 Cse1l−/− mutants could be identified by PCR (Fig. 3). To investigate further the nature of the lethality, we examined serial sections of the embryos grown in uteri at E5.5. As shown in Fig. 4B, mutant embryos were significantly smaller than their wild-type littermates. Moreover, the mutant embryos lacked any detectable structure, and their cells were morphologically disorganized and degenerated.

FIG. 3.

Representative genotype analysis of E7.5 embryos from Cse1l+/− intercrosses. DNA samples were subjected to PCR amplification using a primer pair specific for wild-type and heterozygous alleles (A) and a primer pair specific for heterozygous and null alleles (B).

FIG. 4.

Histological sections of embryos grown in utero at E5.5. Two hematoxylin- and eosin-stained representative normal embryos (A) and two presumed mutant embryos (B) are shown at ×200 original magnification.

DISCUSSION

The cellular apoptosis susceptibility gene CSE1L, highly homologous to yeast CSE1, is an essential gene that is necessary for accurate chromosome segregation during mitosis and is located on human chromosome 20q13. This region shows a remarkable degree of instability in various types of cancer (2, 4). The mouse homologue of CSE1L, Cse1l, is over 98% identical to human CSE1L at the amino acid level and has the same number of amino acids. The high interspecies homology of the CSE1 genes, overlapping expression patterns in adult tissues, and high expression in embryonic development suggest that it might be a gene with an essential and conserved function.

Heterozygous Cse1l mice are phenotypically normal.

Heterozygous mice expressing Cse1l protein from one normal allele are healthy and reproduce normally. There is no difference in expression of the Cse1l gene in tissues from wild-type and heterozygous mutant mice, suggesting that one normal allele of the Cse1l gene is sufficient to maintain the level of Cse1l protein necessary to exert its normal function. We assume that the remaining active Cse1l allele becomes activated to compensate (most likely on the transcriptional level) for the missing allele. To date there is no report on functional characterization of either the promoter region or the factors regulating the CSE1 gene. It would be necessary to identify and characterize those elements to understand how the expression of this gene is regulated in vivo.

Cse1l homozygous embryos die before E5.5.

Since CSE1L functions in apoptosis as well as in proliferation, two important processes that regulate normal development, one would expect that Cse1l plays an essential role during development. Experiments in yeast and in mammalian cells indicate CSE1 and CSE1L to be essential genes, because yeast strains that carry CSE1 mutations display conditional lethal phenotypes (18) and antisense-mediated depletion of CSE1L results in mitotic arrest and subsequent cell death in mammalian cell culture experiments (15). Also, mutations in pendulin, an importin α gene homologue that almost certainly acts in an equivalent nuclear-transport pathway in fly cells, not only display aberrant cell proliferation but ultimately cause the death of Drosophila larvae (10). However, some observations of living animals with complete knockouts of genes that were previously thought to be essential due to the results of cell culture experiments indicate that in vitro experiments are severely limited in determining essentiality of genes (7, 16). Obviously, in the development of living organisms, unidentified mechanisms that can compensate even for severe deficiencies may occur.

Our data show that the Cse1l gene plays a vital role in a very early stage of mouse development and that its activity cannot be compensated for in homozygous knockout mice. The growth deficit of Cse1l homozygous embryos could result from generalized metabolic collapse, excess cell death, decreased cell proliferation, or a combination of these processes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Wilfred Vieira for technical assistance and Shannon Merry and Anna Mazzuca for editorial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bera T K, Pastan I. Mesothelin is not required for normal mouse development or reproduction. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2902–2906. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.8.2902-2906.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinkmann U. CAS, the human homologue of the yeast chromosome-segregation gene CSE1, in proliferation, apoptosis, and cancer. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:509–513. doi: 10.1086/301773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinkmann U, Brinkmann E, Bera T K, Wellmann A, Pastan I. Tissue specific alternatively spliced variants of hCSE1/CAS may be regulators of nuclear transporter of tissue specific proteins. Genomics. 1999;58:41–49. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brinkmann U, Brinkmann E, Gallo M, Pastan I. Cloning and characterization of a cellular apoptosis susceptibility gene, the human homolog to the yeast chromosome segregation gene CSE1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10427–10431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinkmann U, Brinkmann E, Pastan I. Expression cloning of cDNAs that render cancer-cells resistant to pseudomonas and diphtheria-toxin and immunotoxins. Mol Med. 1995;1:206–216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chi N C, Adam S A. Functional domains in nuclear import factor p97 for binding the nuclear localization sequence receptor and the nuclear pore. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:945–956. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.6.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colucci-Guyon E, Portier M M, Dunia L, Paulin D, Pournin S, Babinet C. Mice lacking vimentin develop and reproduce without an obvious phenotype. Cell. 1994;79:679–694. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorlich D, Dabrowski M, Bischoff F R, Kutay U, Bork P, Hartmann E, Prehn S, Izaurralde E. A novel class of RanGTP binding proteins. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:65–80. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irniger S, Piatti S, Michaelis C, Nasmyth K. Genes involved in sister-chromatid separation are needed for B-type cyclin proteolysis in budding yeast. Cell. 1995;81:269–278. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kussel P, Frasch M. Pendulin, a drosophila protein with cell cycle-dependent nuclear-localization, is required for normal-cell proliferation. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:1491–1507. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.6.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kutay U, Bischoff F R, Kostka S, Kraft R, Gorlich D. Export of importin alpha from the nucleus is mediated by a specific nuclear transport factor. Cell. 1997;90:1061–1071. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80372-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laird P W, Zijderveld D A, Linders L, Rudnicki M A, Jaenisch R, Berns A. Simplified mammalian DNA isolation procedure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4293–4293. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.15.4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moroianu J, Blobel G, Radu A. Nuclear protein import: Ran-GTP dissociates the karyopherin alpha beta heterodimer by displacing alpha from an overlapping binding site on beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7059–7062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moy T I, Silver P A. Nuclear export of the small ribosomal subunit requires the Ran-GTPase cycle and certain nucleoporins. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2118–2133. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.16.2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogryzko V V, Brinkmann E, Howard B H, Pastan I, Brinkmann U. Antisense inhibition of CAS, the human homologue of the yeast chromosome segregation gene CSE1, interferes with mitosis in HeLa cells. Biochemistry. 1997;36:9493–9500. doi: 10.1021/bi970236o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saga Y, Yagi T, Ikawa Y, Sakakura T, Aizawa S. Mice develop normally without tenascin. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1821–1831. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wellmann A, Krenacs L, Fest T, Scherf U, Pastan I, Raffeld M, Brinkmann U. Localization of the cell proliferation and apoptosis-associated CAS protein in lymphoid neoplasms. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:25–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao Z X, McGrew J T, Schroeder A J, FitzGerald-Hayes M. CSE1 and CSE2, two new genes required for accurate mitotic chromosome segregation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4691–4702. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]