Abstract

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is a common malignancy arising from the liver with limited 5-year survival. Thus, there is an urgency to explore new treatment methods. Chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR T) cell therapy is a very promising cancer treatment. Though, several groups have investigated CAR T cells targeting MUC1 in solid cancer models, Tn-MUC1-targeted CAR T cells have not yet to be reported in ICC. In this study, we confirmed Tn-MUC1 as a potential therapeutic target for ICC and demonstrated that its expression level was positively correlated with the poor prognosis of ICC patients. More importantly, we successfully developed effective CAR T cells to target Tn-MUC1-positive ICC tumors and explored their antitumor activities. Our results suggest the CAR T cells could specifically eliminate Tn-MUC1-positive ICC cells, but not Tn-MUC1-negative ICC cells, in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, our study is expected to provide new therapeutic strategies and ideas for the treatment of ICC.

Key Words: Tn-MUC1, CAR T-cell therapy, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, glycosylation

Liver cancer is classified as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) according to the tumor cell origin. ICC is a highly heterogeneous tumor that originates from epithelial cells of the intrahepatic bile duct. This cancer usually occurs in the small intrahepatic bile duct or the bold intrahepatic duct near the bifurcation. On the basis of the pathologic characteristics of the tumor, the degree of malignancy of ICC is relatively high and usually asymptomatic in the early stage. When the tumor is clinically diagnosed, it has often advanced to the malignant stage. Although available treatment options are basically the same as those of HCC, including surgical resection, ablation, intervention, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and targeted therapy, the effectiveness on ICC is poorer and the recurrence rate and death are higher.1,2 Exploration of new effective treatment methods for ICC is critical and needed urgently in the clinic.

ICC tumor tissue consists of a complex tumor microenvironment, and it is difficult for T cells to achieve tumor resistance.3 Recently, different methods have been discovered to utilize the immune system to destroy tumor cells. Among them, cellular immunotherapy, especially T cells modified with a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR), has been demonstrated as a promising strategy for cancer treatment.4 CAR is a receptor expressed on T cells that can recognize tumor cell antigens and eliminate tumor cells in a nonmajor histocompatibility complex-restricted manner. The extracellular recognition fragment of this receptor is a single-chain fragment variable (scFv), which recognizes tumor cell surface antigens. CAR T-cell therapy targeting CD19 has shown tremendous efficacy in eliminating hematologic tumors and thus has been approved to treat leukemia and lymphoma patients.5 Several studies of CAR T cells targeting solid tumors, including GPC3 and AFP CAR T-cell for the treatment of HCC, have also shown therapeutic potential.6,7

Tumor progression is often accompanied by protein glycosylation, which is closely related to tumorigenesis and metastasis.8 MUC1 is a high-molecular-weight transmembrane mucin family protein that consists of highly glycosylated tandem repeats. The inactivation of T-synthase (glycoprotein-N-acetylgalactosamine 3-β-galactosyltransferase one, C1GALT1) and C1GALT1-specific chaperone one (COSMC) leads to aberrant glycosylation of MUC1 in cancer cells and produces a large amount of Tn-MUC1 antigen, which is completely different from the sugar chains of MUC1 in normal cells.9,10 The glycosylation modification exposes tumor cell-specific glycopeptide epitopes, making MUC1 an attractive target for cancer treatment.11 Studies demonstrated that 5E5 antibodies recognize the cancer-associated Tn glycoform of MUC1.12,13 Posey et al14 developed a CAR-targeting aberrant MUC1 glycosylation on the membrane of T-cell leukemia and pancreatic cancer cells, but not on any normal human tissues. Moreover, several groups have investigated CAR T cells targeting MUC1 in solid cancer models.15–20 However, Tn-MUC1-targeted CAR T cells have yet to be reported in ICC. Therefore, in this study, we developed Tn-MUC1 CAR T cells based on the 5E5 antibody sequence and investigated their antitumor activities in ICC in vitro and in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines

Five human ICC cell lines were used in this study, namely HuCCT1, SG231, and CCLP1 (kindly provided by Dr. Robert Anders at Johns Hopkins University), as well as HCCC-9810 and RBE (purchased from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Shanghai Branch Cell Bank, Shanghai, China). These cell lines were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2. SG231 were cultured in Minimum Essential Media (Gibco), while the other cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Patients and Tissue Samples

ICC tumor tissues were obtained from 328 ICC patients who underwent surgical resection between January 2009 and December 2013 at the Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University. Ethical approval for the use of human subjects was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital (Shanghai, China), and informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The ICC tissue microarray was immunostained using the 5E5 antibody, a recombinant antibody in which the scFv sequence was derived from US2017/0145108A1 (manufactured by Sino Biological; Supplemental Fig. 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JIT/A710 for sequence information). To detect human T cells in xenografts, sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissues were immunostained using an anti-CD3 antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Rehydration and microwave antigen retrieval were performed first, then BSA blocking samples were stained with diluted primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with a secondary antibody (GK500705; Gene Tech, China) at 37°C for one hour. Addition of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine and counterstaining with Mayer’s hematoxylin were used to stain the slides. The final IHC results were confirmed by at least two experienced pathologists.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

The expression of Tn-MUC1 and 5E5 CAR was analyzed using a flow cytometry (FACSAria II, BD Biosciences). In brief, 1×106 cells were suspended in cold PBS and incubated with 5E5 antibody or biotin-streptavidin-conjugated goat antimouse immunoglobulin (Ig)G (Fab) (Jackson Immunoresearch, 115-065-072) for one hour at 4°C. Then, the cells were washed with cold PBS and incubated with PE-conjugated rat antimouse IgG (BD Biosciences, 550083) or PE-conjugated streptavidin (BD Biosciences, 554061) for one hour at 4°C. After washing with PBS, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Western Blot

The expression of total MUC1 was detected by Western blot. Briefly, total cell lysates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore). Primary antibodies against MUC1 (Cell Signaling Technology, #4538S) and GAPDH (Proteintech, 60004-1-Ig) were applied before incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #G-21040).

Generation of HuCCT1 Knockout Cells by CRISPR/Cas9

A gRNA (ATCCTATTGCTGATCCACAG) targeting human C1GALT1 gene was cloned into the pSpCas9 (BB)-2A-green fluorescent protein (PX458) vector (Addgene, #48138). Then the gRNA/Cas9 expression construct was transfected into HuCCT1 cells using the Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. At 24 hours posttransfection, green fluorescent protein-positive cells were sorted by flow cytometry (FACSAria II, BD Biosciences) and transferred into 96-well plates at one cell per well. After two weeks of culture, the candidate clones were analyzed by PCR and sequenced. The primer sequences used were: 5′-GCAGCAAATAGAGGGGTAAACTC-3′ and 5′-GCAATTCCCTTCTCTTGAGGC-3′.

CAR Lentivirus Production

The 5E5 CAR sequence was synthesized by Genewiz, a gene synthesis company, and subcloned into the EF-1α promoter-based lentiviral expression vector. The sequence encoding the 5E5 scFv antibody was derived from US2017/0145108A1. The other CAR sequence was derived from patent US8911993. Recombinant lentiviral particles were produced in 293T cells and then concentrated by ultracentrifugation for two hours at 100,000g.

CAR T-Cell Generation

CD3 T cells were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of human healthy donors by negative selection (Stem Cell Technologies). Human T cells were cultured in ImmunoCult-XF T-Cell Expansion Medium (Stem Cell Technologies) and activated with ImmunoCult Human CD3/CD28 T-Cell Activator (Stem Cell Technologies). One day after activation, human T cells were transduced with concentrated lentivirus at multiplicity of infection=30. The titer of concentrated lentivirus was measured by quantitative PCR in 293 T-cell. And then expanded in the presence of 300 U/ml interleukin-two (Shandong Quangang Pharmaceutical) for eight–12 days with 175 cm2 Angled Neck Cell Culture Flask with Vent Cap (Corning) for large scale expansion.

In Vitro Coculture Killing Experiments

Cytotoxicity determined by annexin V staining

To detect the cytotoxic effect of CAR T cells to target cells, we used Annexin V staining to analyze carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled target cell apoptosis by flow cytometry. Target cells were labeled with five µmol/l CFSE (BD Biosciences) in one mL PBS for 10 minutes at 37°C, then washed three times with culture medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. ICC cells were cocultured with Mock or CAR T cells at an effector to target (E:T) ratio of 1:1. Following 18 hours of culture, cells were stained with allophycocyanin-conjugated Annexin V (BD Biosciences) and the percentage of dead target cells (defined as CFSE+ Annexin V+) was determined by a flow cytometric analysis (FACSAria II, BD Biosciences).

Cytotoxicity determined by cell counting kit-8 assay

The cytotoxicity of CAR T cells toward ICC cells at effector: target ratios of 3:1, 1:1, and 1:3 was measured. After the T cells and target cells were incubated for 18 hours, the number of remaining adherent target cells was detected using the cell counting kit-8 assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cytokine Release Assays

After coculture with target cells, interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α secretion by T cells was determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Novus Biologicals) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

In Vivo Antitumor Experiments

All studies complied with the ethical regulations established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhongshan Hospital (Shanghai, China). Female B-NDG mice aged six–eight weeks (Biocytogen) were used in this study. HuCCT1 cells (5×106) were implanted per mouse to establish the subcutaneous ICC model. Mice were randomized into two groups at seven days after tumor cell implantation. Mock and CAR T cells were injected through the tail vein twice.

RESULTS

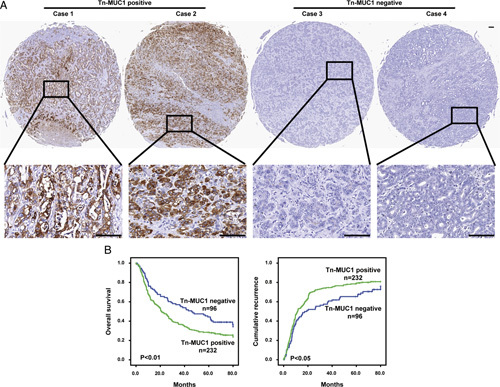

Tn-MUC1 Expression Correlates With Poor Prognosis in ICC Patients

Tumor-associated antigens are potential targets for antitumor therapy development. It was reported that the level of Tn-MUC1 was high in adenocarcinomas including breast and ovarian carcinomas, but limited in normal tissues.14 While its expression in ICC has less been studied. To determine the expression of Tn-MUC1 in ICC, we generated a Tn-MUC1 specific monoclonal antibody 5E5 (Supplemental Fig. 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JIT/A710 for antibody sequence). The expression of Tn-MUC1 in 328 cases of ICC patients on tumor tissue microarray was examined by IHC experiments using the 5E5 antibody. We found that Tn-MUC1 was highly expressed in tumor tissues of 70.73% ICC patients, while barely detectable in adjacent normal tissues. Representative immunostaining images of two Tn-MUC1-positive cases and two Tn-MUC1-negative cases were presented in Figure 1A. These data suggest Tn-MUC1 is also a tumor-associated antigen for ICC. To explore the prognostic significance of Tn-MUC1 in ICC patients, 328 ICC patients were divided into two groups based on Tn-MUC1 expression, namely the Tn-MUC1-positive or Tn-MUC1-negative group, and then survival and recurrence analysis were performed for these two groups of patients (Fig. 1B). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that the one, three, and five years survival rates of ICC patients with positive Tn-MUC1 expression were lower than patients with negative Tn-MUC1 expression (62.3% vs. 75.0%, 36.5% vs. 57.0%, 28.5% vs. 44.4%, respectively), and the overall survival rate of patients with positive Tn-MUC1 expression was significantly lower than those with negative Tn-MUC1 expression. Similarly, the one, three, and five years cumulative recurrence rates of patients with positive Tn-MUC1 expression were higher than those with negative Tn-MUC1 expression (52.7% vs. 42.3%, 74.7% vs. 57.5%, 79.0% vs. 65.3%, respectively). The clinical information of individual patient was shown in Supplemental Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JIT/A711. Taken together, these data suggest Tn-MUC1 expression was related to poor prognosis in ICC patients.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of Tn-MUC1 correlates with poor prognosis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients. A, Representative Tn-MUC1 expression in tumor tissues by immunohistochemical staining analysis (scale bar, 100 µm). B, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showing cumulative recurrence rates and overall survival (OS) rates based on Tn-MUC1 expression. Compared with the Tn-MUC1-positive group, the Tn-MUC1-negative group exhibited a significantly higher OS and time to recurrence. For the statistical analyses, SPSS 25.0 was used. Student’s t tests were used to process quantitative data. The Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to calculate OS and cumulative recurrence rates. P values below 0.05 were considered to be significant.

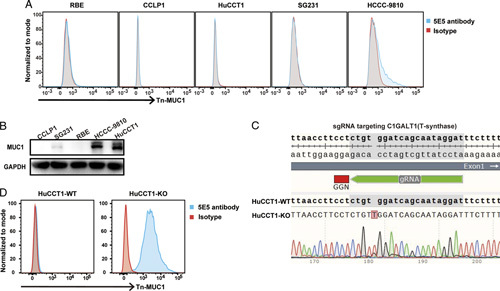

Construction of ICC Cell Line Expressing Tn-MUC1

Further, ICC cell lines were screened for Tn-MUC1 expression. The level of Tn-MUC1 and total MUC1 in ICC cell lines HuCCT1, SG231, CCLP1, HCCC-9810, and RBE were detected by FACS and Western blot, respectively. Tn-MUC1 was barely detectable in all five ICC cell lines (Fig. 2A), but total MUC1 was detected in HCCC-9810 and HuCCT1 cells (Fig. 2B). And then we utilized CRISPR/Cas9 method to knockout C1GALT1 gene in HuCCT1 cells to inactivate T-synthase, thereby accumulating Tn glycoforms. As shown in Figures 2C, A frameshift mutation was introduced into exon one of C1GALT1 gene to generate C1GALT1 knockout HuCCT1 cells (HuCCT1-KO). Abundant Tn-MUC1 was detected in HuCCT1-KO cells (Fig. 2D). Collectively, a Tn-MUC1-positive ICC cell line was constructed successfully for further study.

FIGURE 2.

Construction of an intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) cell line expressing Tn-MUC1. A, The protein levels of Tn-MUC1 were determined by flow cytometry in five common ICC cell lines. B, Relative total MUC1 levels in five common ICC cell lines was detected by western blot. C, Deletion of T-synthase in HuCCT1 cells through the CRISPR/Cas9 method. Single guide RNA (sgRNA) was used to specifically target C1GALT1, which encodes T-synthase, resulting in the introduction of a frameshift insertion mutation into the HuCCT1-KO cell line. D, The protein levels of Tn-MUC1 were determined by flow cytometry in HuCCT1-WT and HuCCT1-KO cell lines.

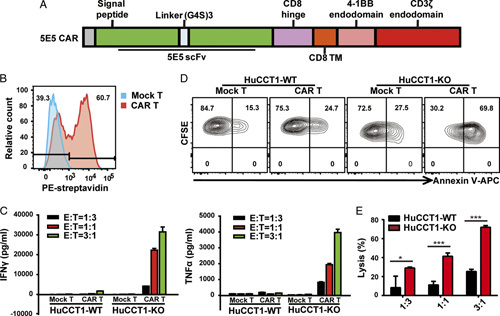

In Vitro Cytotoxicity of 5E5 CAR T Cells

We synthesized the heavy and light chains of the 5E5 antibody that specifically recognizes Tn-MUC1 and constructed the second-generation CAR structure with 4-1BB as the costimulator. We used lentiviral vectors to encode 5E5 CAR as schematically represented in Figure 3A. The transduction efficiency was around 60% (Fig. 3B). When the 5E5 CAR T cells were cocultured with Tn-MUC1-positive HuCCT1-KO cells or Tn-MUC1-negative wild-type HuCCT1 cells (HuCCT1-WT), we found that only HuCCT1-KO cells activated 5E5 CAR T cells to release large amounts of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ (Fig. 3C). Moreover, 5E5 CAR T cells could effectively lyse and kill HuCCT1-KO cells, but not HuCCT1-WT cells (Figs. 3D–E). These data indicate that Tn-MUC1 receptor-modified T cells specifically recognize and kill Tn-MUC1-positive ICC cells in vitro.

FIGURE 3.

In vitro cytotoxicity of 5E5 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. A, Schematic representation of 5E5 CAR. The 5E5 CAR was comprised of a scFv, human CD8 hinge, and transmembrane region derived from human CD8 transmembrane region, as well as the intracellular signaling domains of human 4-1BB and CD3ζ. B, Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of 5E5 CAR in transduced T lymphocytes. Mock T and 5E5 CAR T cells were stained with biotinylated goat antimouse immunoglobulin G and streptavidin-PE. C, Mock or 5E5 CAR T cells were incubated with HuCCT1-WT or HuCCT1-KO at different effector: target (E:T) ratios for 24 hours. Then the production of interferon (IFN)-γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data representative of three independent experiments were shown. D, In vitro cytotoxic activities of 5E5 CAR T cells. The Mock or 5E5 CAR-modified T cells were incubated with CFSE-labeled HuCCT1-WT or HuCCT1-KO cell lines at an E:T ratio of 1:1 for 18 hours. Flow cytometric analysis of target cells stained with CFSE and APC-labeled Annexin V. E, Mock or 5E5 CAR T cells were incubated with HuCCT1-WT or HuCCT1-KO at different E:T ratios for 18 hours. Specific lysis of target cells was measured by performing the cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay on the remaining live target cells. The error bars indicated the SD, and an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was used for comparisons to determine statistical significance (*P<0.05, ***P<0.001). APC indicates allophycocyanin; CFSE, carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester.

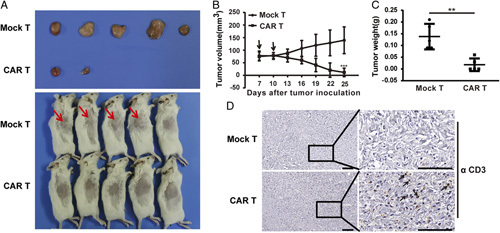

5E5 CAR T Cells Suppress the Growth of Tn-MUC1-Positive Xenografts

HuCCT1-KO xenograft mouse model was established to evaluate efficacy of 5E5 CAR T cells in vivo. HuCCT1-KO cells were inoculated subcutaneously into severe immunodeficiency B-NDG mice, followed by intravenous injection of 5E5 CAR T cells or Mock T cells seven and 10 days after tumor inoculation. Tumor volume was measured every three days. Tumors were collected and weighted at the endpoint of the experiment. In 5E5 CAR T cells treatment group, three of five mice were tumor free (Fig. 4A). 5E5 CAR T cells but not Mock T cells effectively inhibited HuCCT1-KO xenografts growth (Figs. 4B and C). Previous mouse studies have demonstrated that the persistence of transferred T cells is highly correlated with tumor regression. In our study, two weeks after administration, more T cells were detected in tumors treated with 5E5 CAR T cells than in tumors treated with Mock T cells (Fig. 4D). Consistent with findings in in vitro assay, neither 5E5 CAR T cells nor Mock T cells could inhibit HuCCT1-WT xenografts growth (Supplemental Fig. 2, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/JIT/A712). These data indicate that 5E5 CAR T cells specifically eliminate Tn-MUC1-positive ICC xenografts in vivo.

FIGURE 4.

In vivo antitumor activity of 5E5 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells in established subcutaneous intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma tumor xenografts. A, Tumor tissue and images of mice treated with the indicated T cells at the endpoint of the assay. Tumor bulges were indicated with an arrow. B, Growth curve of HuCCT1-KO xenografts treated with the indicated T cells. At the endpoint, the residual tumors treated with 5E5 CAR T cells were significantly smaller than those in the control groups. The time point of T-cell infusion was shown with an arrow. The data represented the mean±SD, and two-way analysis of variance was used for comparisons between two groups (***P<0.001). C, The tumor weight was measured for Mock T and CAR T groups at the endpoint of the experiment. The data represented the mean±SD, and an unpaired two-tailed Student t test was used for comparisons to determine statistical significance (**P<0.01). D, Representative immunostained images of CD3+ T-cell infiltration into tumor tissues from intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma tumor xenografts. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded mouse tissue sections were stained for human CD3 (brown). Representative staining of tumor sections from each experimental group was shown and some human CD3 T cells were indicated with an arrow. Each scale bar represents 100 µm.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we confirmed that Tn-MUC1 may be a potential therapeutic target for ICC, and its expression level was positively correlated with poor prognosis of ICC patients. More importantly, we successfully developed effective CAR T cells to target Tn-MUC1-positive ICC tumors, which provides a new method for the treatment of ICC.

A Tn-MUC1-positive ICC cell line was not available in our lab unfortunately; however, Tn-MUC1 in tumor tissue was detected in 70.73% ICC patients. We suppose that Tn-MUC1-positive cells were not the predominant clone when the cell lines were developed. Indeed, this phenomenon also occurs for the Claudin18.2 protein. Claudin18.2 is specifically expressed in normal stomach cells yet highly expressed in gastric cancer tissues. However, few gastric cancer cell lines with uniform expression of Claudin18.2 are available.21 Many studies utilized Claudin18.2-positive cell lines that were developed through overexpression.22–24 In our system, we detected low expression of Tn-MUC1 in some HCCC-9810 cells (Fig. 2A). Nevertheless, when we enriched for positive cells by sorting and expansion, the percentage of Tn-MUC1-positive cells remained low, similar to pre-sorting levels (Supplemental . 3, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/JIT/A713). Sun et al25 suggested that the maintenance of Tn-positive subpopulations after sorting was difficult in SW480 and that its expression was reversible in these cells. Collectively, it is reasonable that high Tn-MUC1 expression was detected in most ICC tumor tissues, even if it was not detected in ICC cell lines.

Our results demonstrate 5E5 CAR T cells effectively eliminate Tn-MUC1-positive ICC cells in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, He et al26 reveal that alternative Tn-antigens (such as podoplanin-Tn) are also tumor-specific antigens and can be targeted by 5E5 CAR. These data suggests 5E5 CAR has broader targeting beyond Tn-MUC1, and 5E5 CAR T-cell therapy is a potential approach to treat tumor patients with different Tn-antigens. More importantly, Tn-MUC1 may be a prospective CAR T-cell therapeutic target for ICC and it is necessary to screen humanized antibodies with high affinity and high specificity, as humanized CAR T cells appear to persist longer than the murine CAR T cells. At present, the potency of CAR T cells on solid tumors is still limited. The key difficulty is how CAR T cells can break through the fibrous matrix barrier of solid tumors and resist the suppressive tumor environment before infiltrating the tumor site and eradicating the tumor cells. Developing armed CAR T cells with a greater ability to infiltrate and longer persistence is a promising direction for research on solid tumors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST/FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

This study was jointly supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 91942313) and the Major Special Projects of the Ministry of Science and Technology (2018ZX10302207).

All authors have declared that there are no financial conflicts of interest with regard to this work.

Footnotes

L.M., S.S., J.L., and S.Y. contributed equally to this work.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.immunotherapy-journal.com.

Contributor Information

Li Mao, Email: sysuncml@163.com.

Sheng Su, Email: 20211210058@fudan.edu.cn.

Jia Li, Email: li.jia@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

Songyang Yu, Email: 19111210076@fudan.edu.cn.

Yu Gong, Email: gong.yu@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

Changzhou Chen, Email: chenchangzhou00@163.com.

Zhiqiang Hu, Email: Hu.zhiqiang@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

Xiaowu Huang, Email: huang.xiaowu@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bridgewater J, Galle PR, Khan SA, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2014;60:1268–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang H, Yang T, Wu M, et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and surgical management. Cancer Lett. 2016;379:198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sirica AE, Strazzabosco M, Cadamuro M. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: morpho-molecular pathology, tumor reactive microenvironment, and malignant progression. Adv Cancer Res. 2021;149:321–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadelain M, Riviere I, Riddell S. Therapeutic T cell engineering. Nature. 2017;545:423–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamprecht M, Dansereau C. CAR T-cell therapy: update on the State of the Science. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2019;23:6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi D, Shi Y, Kaseb AO, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-glypican-3 T-cell therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results of phase I trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:3979–3989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu H, Xu Y, Xiang J, et al. Targeting alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)-MHC complex with CAR T-cell therapy for liver cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:478–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magalhaes A, Duarte HO, Reis CA. Aberrant glycosylation in cancer: a novel molecular mechanism controlling metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:733–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ju T, Cummings RD. A unique molecular chaperone Cosmc required for activity of the mammalian core 1 beta 3-galactosyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16613–16618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger EG. Tn-syndrome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1455:255–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nath S, Mukherjee P. MUC1: a multifaceted oncoprotein with a key role in cancer progression. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:332–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tarp MA, Sorensen AL, Mandel U, et al. Identification of a novel cancer-specific immunodominant glycopeptide epitope in the MUC1 tandem repeat. Glycobiology. 2007;17:197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorensen AL, Reis CA, Tarp MA, et al. Chemoenzymatically synthesized multimeric Tn/STn MUC1 glycopeptides elicit cancer-specific anti-MUC1 antibody responses and override tolerance. Glycobiology. 2006;16:96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Posey AD, Jr, Schwab RD, Boesteanu AC, et al. Engineered CAR T cells targeting the cancer-associated Tn-glycoform of the membrane mucin MUC1 control adenocarcinoma. Immunity. 2016;44:1444–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilkie S, Picco G, Foster J, et al. Retargeting of human T cells to tumor-associated MUC1: the evolution of a chimeric antigen receptor. J Immunol. 2008;180:4901–4909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bajgain P, Tawinwung S, D’Elia L, et al. CAR T cell therapy for breast cancer: harnessing the tumor milieu to drive T cell activation. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:34–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou R, Yazdanifar M, Roy LD, et al. CAR T cells targeting the tumor MUC1 glycoprotein reduce triple-negative breast cancer growth. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1149–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mei Z, Zhang K, Lam AK, et al. MUC1 as a target for CAR-T therapy in head and neck squamous cell carinoma. Cancer Med. 2020;9:640–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Supimon K, Sangsuwannukul T, Sujjitjoon J, et al. Anti-mucin 1 chimeric antigen receptor T cells for adoptive T cell therapy of cholangiocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 2021;11:6276–6289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yazdanifar M, Zhou R, Grover P, et al. Overcoming immunological resistance enhances the efficacy of a novel anti-tMUC1-CAR T cell treatment against pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cells. 2019;8:1070–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahin U, Koslowski M, Dhaene K, et al. Claudin-18 splice variant 2 is a pan-cancer target suitable for therapeutic antibody development. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7624–7634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang H, Shi Z, Wang P, et al. Claudin18.2-specific chimeric antigen receptor engineered T cells for the treatment of gastric cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu G, Foletti D, Liu X, et al. Targeting CLDN18.2 by CD3 bispecific and ADC modalities for the treatments of gastric and pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep. 2019;9:8420–8430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang J, Zhang H, Huang Y, et al. A CLDN18.2-targeting bispecific T cell co-stimulatory activator for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:6977–6987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun X, Ju T, Cummings RD. Differential expression of Cosmc, T-synthase and mucins in Tn-positive colorectal cancers. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:827–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He Y, Schreiber K, Wolf SP, et al. Multiple cancer-specific antigens are targeted by a chimeric antigen receptor on a single cancer cell. JCI Insight. 2019;4:130416–130427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]