Supplemental Digital Content is Available in the Text.

Key Words: HIV, menopause, viral suppression, adherence

Background:

Increasing numbers of women living with HIV transition through menopause. It is unclear whether this transition has an impact on treatment adherence, viral suppression, psychiatric comorbidities, or drug use. We aimed at examining adherence and viral suppression during the perimenopausal period and explored the influence of psychiatric comorbidities and active injection drug use (IDU).

Setting:

Retrospective Swiss HIV Cohort Study analysis from January 2010 to December 2018.

Methods:

We explored perimenopausal and postmenopausal trends of viral blips, low-level viremia, viral failure, adherence, psychiatric comorbidities, and IDU using interrupted time series models.

Results:

Rates of depression and psychiatric care increased during perimenopause before decreasing afterward. Negative treatment outcomes such as viral blips, low-level viremia, viral failure, and low adherence steadily declined while transitioning through menopause—this was also true for subgroups of women with depression, psychiatric treatment, and active IDU.

Conclusions:

Increased rates of depression and psychiatric care while transitioning through menopause do not result in lower rates of adherence or viral suppression in women living with HIV in Switzerland.

INTRODUCTION

As a consequence of longer life expectancy and the ageing of people living with HIV, a growing number of women living with HIV experience transition through menopause.1–3 An increasing body of evidence shows that menopause might occur at an earlier age compared with HIV-negative women, and that many women living with HIV experience severe menopause symptoms.4–7 Independently of the HIV status, menopause transition has been associated with an elevated risk for depression, which has been shown to decrease adherence.8–12 However, it is still unclear whether and how menopause affects adherence and treatment outcomes such as the occurrence of viral blips, low-level viremia, or viral failure.

We investigated trends in self-reported treatment adherence, HIV-RNA viral blips, low-level viremia, and viral failure in women transitioning through menopause, as well as the occurrence of depression, psychiatric care, and active injection drug use (IDU).

METHODS

Study Population and Data Collection

We included all cis-women with onset of menopause between 01/2010 and 12/2018 registered in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS) and excluded those with hysterectomy before menopause onset. The SHCS is a national prospective cohort study covering at least 75% of people living with HIV in Switzerland.13 SHCS data are collected twice yearly during routine visits, including information on menopause onset, self-reported adherence, HIV-RNA measurements, drug use, and comorbidities. Local ethics committees of all participating study sites approved this study, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Definitions

In this study, menopause onset was determined as the first report of presumed menopause defined by the treating physician at a 6 monthly visit in a woman with amenorrhea. To assess perimenopausal and postmenopausal trends and due to the difficulties of exact determination of perimenopause, we chose an observation period of 8 years prior and 8 years after the first menopause report. Self-reported low adherence was defined as missing ART doses once every 2 weeks or more often. Depression diagnosis was made by the treating physicians or psychiatrists, who used standard diagnostic tools. Psychiatric treatment was defined as being in psychiatric (inpatient or outpatient) care. Women were allocated to: A. the depression subgroup if they had at least once a diagnosed depression within ±8 years of menopause onset, B. the psychiatric treatment subgroup if they had at least once been in psychiatric care within ±8 years of menopause onset, C. the active IDU subgroup if they had at least once consumed drugs through injection within ±8 years of menopause onset. The following definitions were used to determine HIV-RNA trends: (1). Viral suppression: having at least 2 consecutive HIV-RNA measurements of <50 copies/mL. Owing to different limits of quantification, the included HIV-RNA measurements at exactly 100, 200, 300, or 400 copies/mL before 2005 were also defined to be virally suppressed. (2). Viral blip: viral suppression followed by a single measurement of HIV-RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL, followed again by viral suppression. (3). Low-level viremia: having more than one consecutive HIV-RNA measurement ≥ 50 copies/mL and <200 copies/mL, including single measurements < 50 copies/mL. (4). Viral failure: having more than one consecutive HIV-RNA measurement of ≥ 200 copies/mL.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population. Group comparisons of categorical variables were investigated using the χ2 test, with continuous variables assessed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Plots of the incidence per year provided an indication of the trends over time. For these plots, the numerator was defined as the occurrence of the respective event in the respective year (maximally once per year per patient, even if the event was measured at multiple visits during that year), and the denominator defined as the number of women in follow-up for that year. The definition was slightly different for viral blips; here, we counted the number of blips per year per patient, so that multiple events per patient year were possible. To confirm perimenopausal and postmenopausal trends, we fitted patient-level interrupted time series logistic regression models with the respective event as dependent variable, with the “interruption” defined as the estimated time of menopause onset. Sandwich-type standard errors were calculated to adjust for intrapatient correlation. A subgroup analysis focussed on differences in trends between women with depression, psychiatric treatment, and active IDU. A sensitivity analysis was performed to account for women with inconsistent bleeding patterns after the report of menopause onset. All statistical analyses were performed with R version 3.6.1.14

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

One thousand one hundred thirty postmenopausal women were included. The median age at menopause onset was 50 years (interquartile range 32–55). 10% experienced an early menopause (menopause onset <45 years) and 2% a premature ovarian insufficiency (menopause onset <40 years). 67% of the participants were of White and 25% of Black ethnicity. At menopause onset, 13% had a detectable viral load, 5% a CD4 count below 200/μL, 27% had been diagnosed with depression and/or were in psychiatric care but only 3% reported IDU (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C16 and Ref. 1).

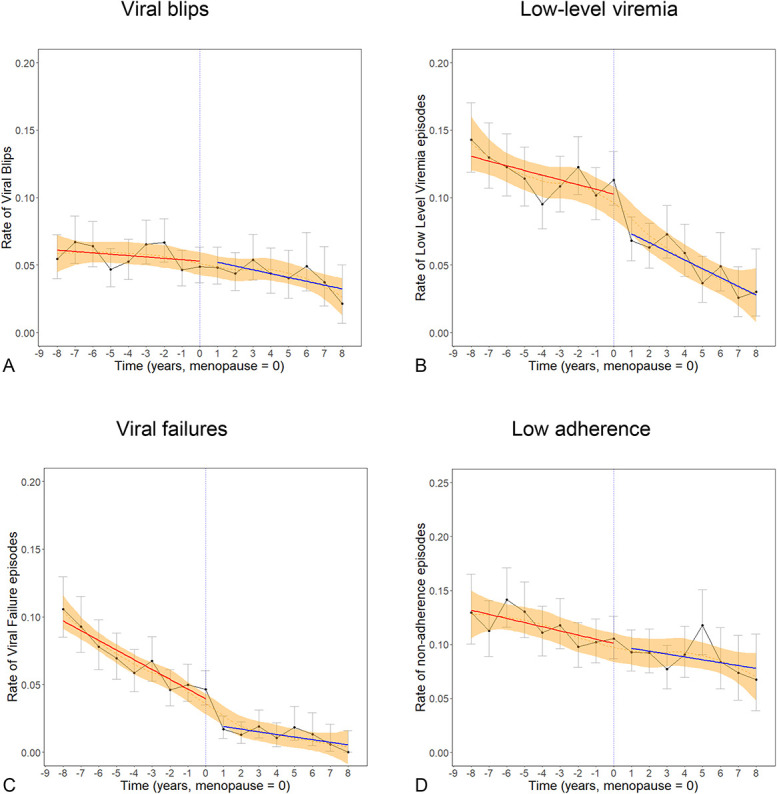

Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Trends in Viral (Non)Suppression and Adherence

We identified a number of trends in the timeframe 8 years before and 8 years after the first menopause report. Viral blips declined slightly but constantly over the 17-year period (Fig. 1A). Episodes of low-level viremia decreased significantly over the whole period {slope odds ratio (OR) 0.95 per year, 95% confidence interval (CI) [0.93 to 0.97], P < 0.001}, with a slightly steeper decline after menopause onset [0.89 per year, 95% CI: (0.83 to 0.96), P = 0.002, Figure 1B]. Viral failures exhibited a steeper decline over the whole period [OR 0.80 per year, 95% CI: (0.78 to 0.82), P < 0.001] compared with the episodes of low-level viremia, but this trend flattened after menopause onset (Fig. 1C). Similarly, self-reported low-adherence episodes decreased over time [OR 0.97 per year, 95% CI: (0.95 to 0.99), P = 0.004], with a slight stabilization after menopause onset (Fig. 1D). A sensitivity analysis excluding 130 women with inconsistent bleeding patterns confirmed the reported trends (results not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Perimenopausal and postmenopausal trends of (A) viral blips (B) low-level viremia (C) viral failures and (D) low adherence. Rate of events over time (black solid), point-wise 95% confidence intervals (gray), LOESS smoother in orange (with 95% confidence intervals shaded), interrupted time series for perimenopause (red) and postmenopause (blue).

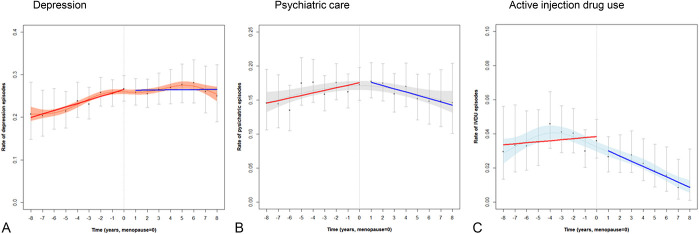

Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Trends of Psychiatric Events and Active Drug Use

We observed a modest increase in depression diagnoses until menopause onset [OR 1.04 per year, 95% CI: (1.00 to 1.08), P = 0.03, Figure 2A], when 23% of women had been diagnosed with depression, and a stabilization without significant decrease afterward. The rate of women attending psychiatric care increased slightly until menopause onset to 17% [OR 1.02 per year, 95% CI: (0.99 to 1.05), P = 0.26], but subsequently decreased in the postmenopausal period to rates similar to before menopause [OR 0.95 per year, 95% CI: (0.91 to 1.01), P = 0.08, Figure 2B]. Active IDU events were rare with no apparent trend until menopause onset. After menopause onset, the rate of women reporting IDU declined steeply [OR 0.85, 95% CI: (0.85 to 0.97), P = 0.01, Figure 2C]. “For non-IDU, there was a rather steep increase in the years up to approximately 4 years before the estimated menopause year (P value for slope 0.001), followed by stabilization (see Figure S1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C15).”

FIGURE 2.

Perimenopausal and postmenopausal trends of patients with depression diagnosis (A), psychiatric care (B), active injection drug use (C) during 8 years before and after menopause onset. Rate of events over time (black solid), point-wise 95% confidence intervals (gray), fitted cubic spline (6 knots, orange, gray, and blue) dashed with 95% confidence intervals shaded), interrupted time series for perimenopause (red) and postmenopause (blue).

Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Trends of Viral (Non)Suppression in Different Subgroups

Subgroup analyses of women diagnosed with depression, being in psychiatric care, or injecting drugs showed no significant differences in the overall rates of viral nonsuppression. The only difference was noted in women with active IDU and women in psychiatric care who experienced a slight increase of low-level viremia before menopause onset. After menopause onset, the trajectories realigned with the other patient groups (see Figure S2, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/QAI/C15).

DISCUSSION

Women living with HIV in Switzerland experience a steady decline in viral blips, low-level viremia, viral failure, and low adherence while transitioning through menopause. By contrast, rates of depression and psychiatric care increase during perimenopause before decreasing afterward. Nonetheless, women with depression and/or psychiatric care do not experience decreased viral suppression during their menopause transition.

Viral Suppression and Adherence During Menopause Transition

Estrogens have a protective role in the course of HIV infection with 17beta-estradiol being able to reduce HIV transcription,15–17 HIV susceptibility of CD4+ T cells and macrophages, and by regulating the HIV reservoir through the estrogen receptor-1.18 Gianella et al19 found a slower HIV reservoir decline in women compared with men and more inducible HIV-RNA+ cells in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women compared with premenopausal. However, clinical studies show that ART response to HIV seems not to be negatively influenced by menopausal status with low estradiol levels.20–22 Moreover, disregarding menopause, adherence and viral suppression improve in both sexes over time being on ART and increasing age.23–25 Our results not only confirm this but also show that viral suppression is not significantly affected by menopause transition. Our findings are supported by Okhai et al23 who also reported higher viral suppression rates and fewer viral rebounds in perimenopausal women compared with younger women. The steeper decline of LLV after menopause onset compared with before is difficult to interpret. It could theoretically be that the natural decline of nonsuppressed episodes is slowed during menopause transition but there have not been any studies with the respective study design to confirm this, and we did not observe this trend regarding the viral blips and viral failure. Three recent studies indicated that women with severe menopausal symptoms are less likely to engage in medical care and to take their ART.26–28 Data on its effect on virological control are only provided in one study, which found a nonsignificant trend toward lower viral suppression rates in women with severe menopausal symptoms.26 Unfortunately, information on menopause symptoms in our patients are lacking, and we are not able to determine whether adverse virologic events occur more often in this subset of patients.

Psychiatric Comorbidities and IDU During Menopause Transition

Our observation of increasing depression during perimenopausal and postmenopause is in line with other studies showing increased depressive symptoms during menopause transition in HIV-positive and HIV-negative women with already diagnosed depression and in those without.8–10 Cohen et al9 found that women with an early menopause transition had a higher risk for depression. This is of importance regarding the earlier menopause onset in women living with HIV reported in our cohort compared with HIV-negative women living in Switzerland.1 The very high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities at the time of menopause onset in our cohort highlights the need of routine mental health screening and treatment possibilities in this population. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports of menopause and its association with IDU.

Viral Suppression and Adherence in Patients With Psychiatric Comorbidities or IDU

Drug use and psychiatric comorbidities including depression have been associated with lower adherence and less viral suppression.8,11,27 Although rates of depression, psychiatric treatment, and IDU increased until menopause, this did not translate into higher rates of detectable viral loads in the entire study population or in the respective subgroups. Based on the assumption that having a psychiatric illness or injecting drugs are frequently chronic conditions—we used generous inclusion criteria for the subgroups and might have missed a signal of increased viral detection in those with more pronounced psychiatric problems.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first analysis exploring viral load trajectories around menopause in women living with HIV in Switzerland. This study provides important information around treatment adherence and success in ageing women living with HIV, which has direct implications for health care providers. However, this study has several limitations. Our data set did not allow to define the reproductive stages according to the STRAW +10 or SWAN criteria.29,30 Furthermore, defining menopause onset as a single time point is problematic because the reproductive stages including perimenopausal and postmenopause are periods whose beginning and end may be blurred. We have addressed these challenges in 2 ways: By using the first report of presumed menopause reported by the treating physician, we have based our analysis on a clinical assessment and by using the time series analysis over a period of 16 years we assert that perimenopausal and postmenopausal as well as premenopausal trends are captured. Moreover, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding women with inconsistent bleeding patterns which showed similar results. HIV-RNA detection is prone to several biases. First, increasingly sensitive HIV assays detect more viral blips and low-level viremia. Second, the introduction of more potent and better tolerable ART combinations over time resulted in better HIV-suppression rates. Third, the decline of viral reservoirs over time, as well as the time on ART and age, also influence viral suppression rates.19,24,25 The definitions of viral blips, low-level viremia, and viral failure are not used consistently between published studies, making comparisons difficult. Our rather high rates of low-level viremia and viral failure are partly due to our conservative definitions based on the official IAS definitions.31 Moreover, we counted low-level viremia and viral failure events which span 2 calendar years as 2 separate events and might have overestimated its incidence. Of importance, neither the definition nor the possible overestimation have an influence on the slope of viral suppression over time and thus do not influence our overall findings. Recall and desirability bias may limit the self-reported adherence information. The findings concerning women with IDU need to be interpreted with caution due to the low numbers of included women and, consequently, the wide confidence intervals.

CONCLUSIONS

Increased rates of depression and psychiatric care while transitioning through menopause do not result in lower rates of adherence or viral suppression in women living with HIV in Switzerland.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all patients, doctors, and nurses associated with the SHCS. The authors specially thank Prof. Andri Rauch for advising us through the course of the project and Dr. Chloe Pasin for sharing her insights on menopause definition and data collection.

Footnotes

This study has been financed within the framework of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study, supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant #177499) by SHCS project # 854 and by the SHCS research foundation. The data are gathered by the Five Swiss University Hospitals, 2 Cantonal Hospitals, 15 affiliated hospitals, and 36 private physicians (listed in http://www.shcs.ch/180-health-care-providers).

None of the authors has declared a possible conflict of interest related to this study. A.H.'s institution has received travel grants, congress and advisory fees from MSD, ViiV, and Gilead, unrelated to this work. B.B. Flury has undertaken Advisory Boards or ad hoc consultancy for Merck/MSD, Melinta/Menarini, Shionogi, and Pfizer, and has received research grants from Melinta/Menarini unrelated to this work. K.E.A.D.'s institution has received research funding unrelated to this publication from Gilead and offered expert testimony for MSD. P.T.'s institution has received grants, advisory fees, and educational grants from Gilead, MSD, and ViiV outside the submitted work. K.A.-P.’s institution has received travel grants and advisory fees from MSD, Gilead, and ViiV healthcare unrelated to this work. I.A.A. is supported by the ProMedica Foundation.

Meetings at which parts of the data were presented “Menopause impacts drug use and mental health in women living with HIV in Switzerland,” E-poster presentation at EACS 2019 Basel, Switzerland.

A.H. and A.A. authors equally contributed to the work. A.H., K.A.-P., and A.A. developed and designed the study. A.A. planned and performed the statistical analyses. A.H. wrote the manuscript with inputs from K.A.-P., and A.A. P.S., A.C., P.E.T., K.D., B.B.F., C.P., L.S.-B., and I.A.A. contributed with their professional expertise, critically reviewed and discussed the analyses and the manuscript.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (www.jaids.com).

Contributor Information

Andrew Atkinson, Email: andrew.atkinson@insel.ch.

Petra Stute, Email: petra.stute@insel.ch.

Alexandra Calmy, Email: Alexandra.Calmy@hcuge.ch.

Philip E. Tarr, Email: philip.tarr@unibas.ch.

Katharine E.A. Darling, Email: Katharine.Darling@chuv.ch.

Baharak Babouee Flury, Email: Baharak.BaboueeFlury@kssg.ch.

Christian Polli, Email: Christian.Polli@eoc.ch.

Leila Sultan-Beyer, Email: leila.sultan-beyer@ksw.ch.

Irene A. Abela, Email: abela.irene@virology.uzh.ch.

Karoline Aebi-Popp, Email: mail@aebi-popp.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hachfeld A, Atkinson A, Stute P, et al. Women with HIV transitioning through menopause: insights from the Swiss HIV cohort study (SHCS). HIV Med. 2022;23:417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smit M, Brinkman K, Geerlings S, et al. Future challenges for clinical care of an ageing population infected with HIV: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:810–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smit M, Cassidy R, Cozzi-Lepri A, et al. Projections of non-communicable disease and health care costs among HIV-positive persons in Italy and the U.S.A.: A modelling study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0186638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Ommen CE, King EM, Murray MCM. Age at menopause in women living with HIV: a systematic review. Menopause. 2021;28:1428–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreira CE, Pinto-Neto AM, Conde DM, et al. Menopause symptoms in women infected with HIV: Prevalence and associated factors. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2007;23:198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tariq S. Positive tRansItions through Menopause (PRIME). Institute for Global Health; 2018. Available at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/global-health/research/a-z/PRIME. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Looby SE. Symptoms of menopause or symptoms of HIV? Untangling the knot. Menopause. 2018;25:728–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maki PM, Rubin LH, Cohen M, et al. Depressive symptoms are increased in the early perimenopausal stage in ethnically diverse human immunodeficiency virus–infected and human immunodeficiency virus–uninfected women. Menopause. 2012;19:1215–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen LS, Soares CN, Vitonis AF, et al. Risk for new onset of depression during the menopausal transition: The Harvard study of moods and cycles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bromberger JT, Kravitz HM, Chang YF, et al. Major depression during and after the menopausal transition: Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Psychol Med. 2011;41:1879–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook JA, Cohen MH, Burke J, et al. Effects of depressive symptoms and mental health quality of life on use of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-seropositive women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999–2002;30:401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Relf MV, Pan W, Edmonds A, et al. Discrimination, medical distrust, stigma, depressive symptoms, antiretroviral medication adherence, engagement in care, and quality of life among women living with hiv in north carolina: a mediated structural equation model. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;81:328–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scherrer AU, Traytel A, Braun DL, et al. Cohort profile update: The Swiss HIV cohort study (SHCS). Int J Epidemiol. 2022;51:33–34j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2019. Available at: http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tasker C, Ding J, Schmolke M, et al. 17β-estradiol protects primary macrophages against hiv infection through induction of interferon-alpha. Viral Immunol. 2014;27:140–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez-Garcia M, Biswas N, Patel MV, et al. Estradiol reduces susceptibility of CD4+ T cells and macrophages to HIV-infection. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szotek EL, Narasipura SD, Al-Harthi L. 17β-estradiol inhibits HIV-1 by inducing a complex formation between β-catenin and estrogen receptor on the HIV promoter to suppress HIV transcription. Virology. 2013;443:375–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das B, Dobrowolski C, Luttge B, et al. Estrogen receptor-1 is a key regulator of HIV-1 latency that imparts gender-specific restrictions on the latent reservoir. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E7795–E7804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gianella S, Rawlings SA, Nakazawa M, et al. Sex differences in HIV Persistence and Reservoir Size during Aging. Clin Infect Dis. 2021:ciab873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alejos B, Suárez-García I, Bernardino JI, et al. Effectiveness and safety of antiretroviral treatment in pre- and postmenopausal women living with HIV in a multicentre cohort. Antivir Ther. 2020;25:335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calvet GA, Velasque L, Luz PM, et al. Absence of effect of menopause status at initiation of first-line antiretroviral therapy on immunologic or virologic responses: A Cohort Study from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patterson KB, Cohn SE, Uyanik J, et al. Treatment responses in antiretroviral treatment–naive premenopausal and postmenopausal HIV‐1–infected women: An analysis from AIDS clinical trials group studies. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:473–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okhai H, Tariq S, Burns F, et al. Associations of menopausal age with virological outcomes and engagement in care among women living with HIV in the UK. HIV Res Clin Pract. 2020;21:174–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghidei L, Simone MJ, Salow MJ, et al. Aging, antiretrovirals, and adherence: a meta analysis of adherence among older HIV-infected individuals. Drugs Aging. 2013;30:809–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiplagat J, Mwangi A, Keter A, et al. Retention in care among older adults living with HIV in western Kenya: A retrospective observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solomon D, Sabin CA, Burns F, et al. The association between severe menopausal symptoms and engagement with HIV care and treatment in women living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2021;33:101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duff PK, Money DM, Ogilvie GS, et al. Severe menopausal symptoms associated with reduced adherence to antiretroviral therapy among perimenopausal and menopausal women living with HIV in Metro Vancouver. Menopause. 2018;25:531–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cutimanco-Pacheco V, Arriola-Montenegro J, Mezones-Holguin E, et al. Menopausal symptoms are associated with non-adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus-infected middle-aged women. Climacteric. 2020;23:229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, et al. Executive summary of the stages of reproductive aging workshop +10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Climacteric. 2012;15:105–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El Khoudary SR, Greendale G, Crawford SL, et al. The menopause transition and women's health at midlife: a progress report from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Menopause. 2019;26:1213–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Virologic Failure. NIH [Internet]. Available at: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-arv/virologic-failure