Background:

The surgical plan to reconstruct the palate must be carefully prepared given the morphological peculiarity of the soft palate forming both the roof of the mouth and the floor of the nasal cavity. This article focuses on the use of folded radial forearm free flaps to manage isolated defects of the soft palate in the absence of tonsillar pillar involvement.

Methods:

Three patients affected by squamous cell carcinoma of the palate underwent resection of the soft palate and immediate reconstruction with a folded radial forearm free flap.

Results:

All three patients showed good short-term morphological-functional outcomes as far as swallowing, breathing, and phonation were concerned.

Conclusions:

The folded radial forearm free flap seems to be an efficacious way to manage localized defects of the soft palate, given the positive outcomes of the three patients treated, and in accordance with other authors. In general, the radial forearm free flap was confirmed to be a versatile solution for those intraoral defects of the soft tissue requiring a limited quantity of volume as in the case of the soft palate.

Takeaways

Question: The current surgical plan of soft palate reconstruction should reestablish functional recovery of speech, swallowing, and breathing, and control velopharyngeal and swallowing dysfunction.

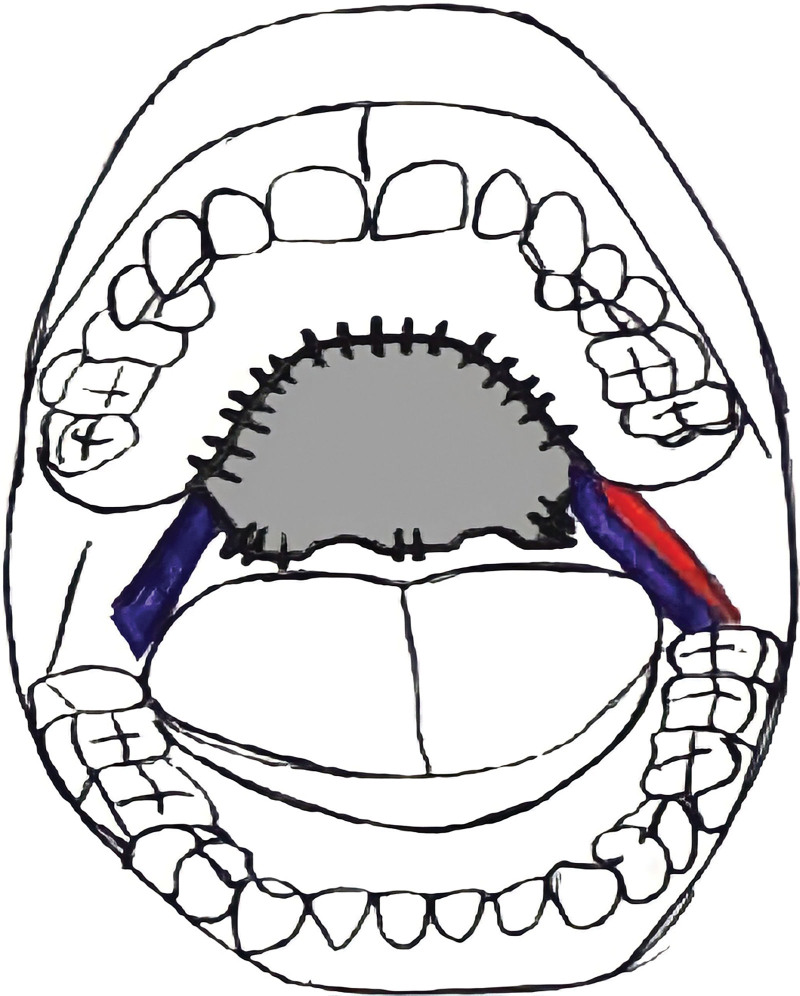

Findings: A personal design of the radial forearm free flap, with a partial de-epithelialization of the median portion, can improve contact of the flap with posterior wall of the oropharynx, reducing the risk of oronasal reflux and velopharyngeal dysfunction. Intraoral synechia was avoided by maintaining two silicone stents.

Meaning: The radial forearm free flap is considered a versatile solution for soft palate reconstruction. Partial adherence of the flap to the posterior wall of the oropharynx can preserve the swallowing reflex and avoid functional problems.

INTRODUCTION

Although challenging, head and neck reconstructive surgery has become commonplace in surgical practice. Though free flaps for soft tissue reconstruction were originally utilized for posttraumatic surgery, the technique is now considered the gold standard for reconstructive surgery after cancer removal.

It is well established that surgical treatment of oral cancer should foresee an approximately 2-cm resection safety margin.1 In the case of lesions located in the soft palate, this strategy has important implications as far as functional deficits and reconstructive strategies are concerned. In fact, velopharyngeal dysfunction and swallowing disturbances can have a very negative impact on the patient’s quality of life.2 Moreover, the surgical plan to reconstruct the palate and to harvest a flap must be carefully prepared given the morphological peculiarity of the soft palate forming both the roof of the mouth and the floor of the nasal cavity. The radial forearm free flap (RFFF) technique is considered one of the most reliable soft tissue reconstruction flaps. It is often used for reconstruction purposes in postablative defects of the tongue, cheek, or retromolar area.3 The current study set out to evaluate the use of folded RFFF to manage isolated defects of the soft palate in the absence of tonsillar pillar involvement.

METHODS

We hereby present the cases of three adult patients who underwent reconstructive surgery of the palate by means of a folded RFFF (Figs. 1 and 2). The flap was harvested from the patient’s nondominant forearm after the Allen test for blood flow was performed to exclude that the loss of the radial artery blood flow would lead to hand ischemia. The shape of the flap was generally rectangular although its actual dimension was determined by the entity of the defect. The width of the flap should be double the length between the palatine margin of the resection and the posterior wall of the oropharynx; normally it tends to be ~8 cm wide (Fig. 3). The length of the flap, which instead depends on the entity of the involvement of the tonsillar pillars, fell between 4 and 5 cm, as those structures were not involved in the cases examined, and the defects were limited to the soft palate. The flap was harvested, maintaining two venous drainage systems, including both the venae comitantes and the cephalic vein.

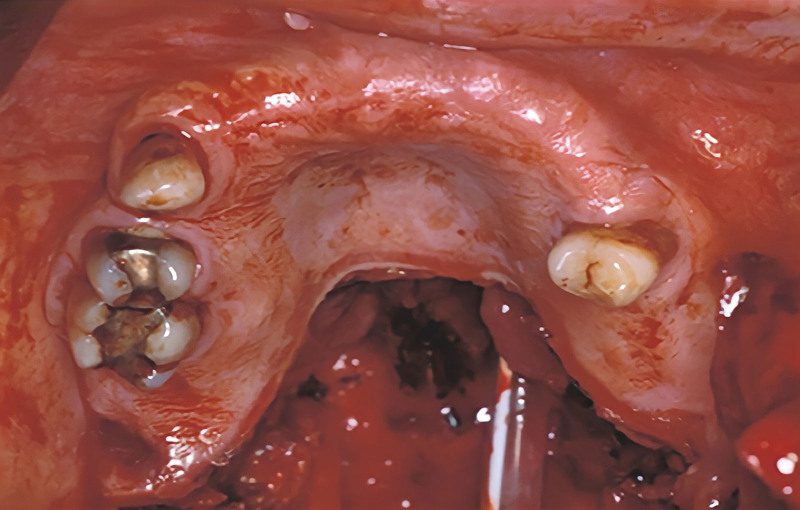

Fig. 1.

Intraoral preoperative view.

Fig. 2.

Intraoral view after resection.

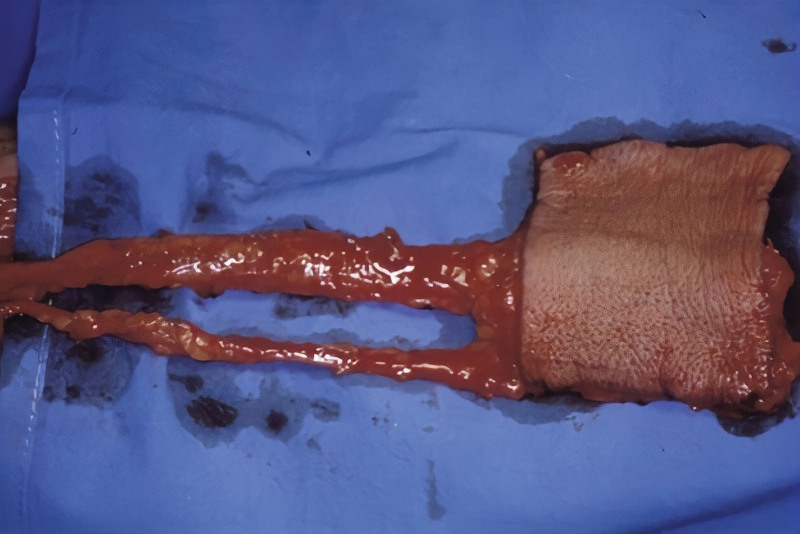

Fig. 3.

Flap harvesting.

The flap was inset after it was folded in half and the cut edge was positioned anteriorly; it was sutured to the hard palate (Fig. 4). The folded side of the flap was sutured after the median portion on the posterior wall of the oropharynx was de-epithelialized to stabilize the flap and to reduce the risk of oronasal reflux. Two silicone tubes reaching the distal margin of the reconstruction were positioned at the nasal apertures (choanae) to ensure the patency of the pharynx and to preserve nasal breathing (Fig. 5). The vascular pedicles run laterally in the paramedian region to the tonsillar pillars (Fig. 6). Vascular anastomoses with the facial artery and branches of the thyrolinguofacial trunk were carried out. The silicone tubes were kept in place for 30 days during the postoperative period to allow for the flap to stabilize.

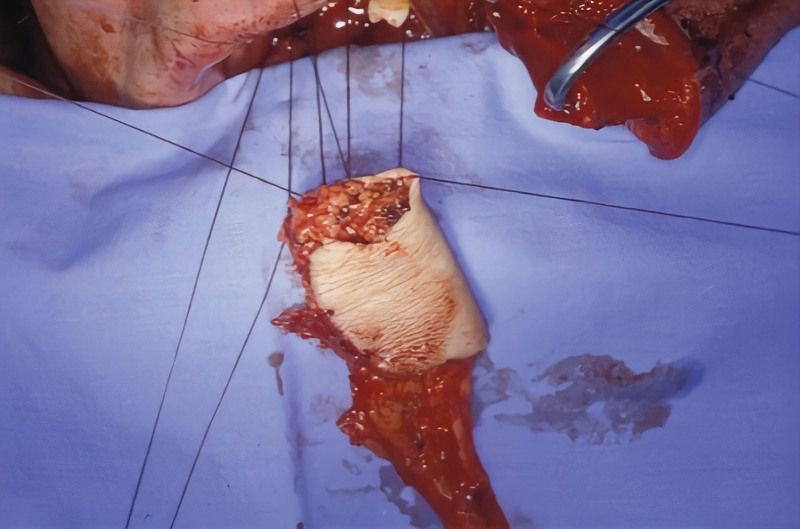

Fig. 4.

Folding of the flap.

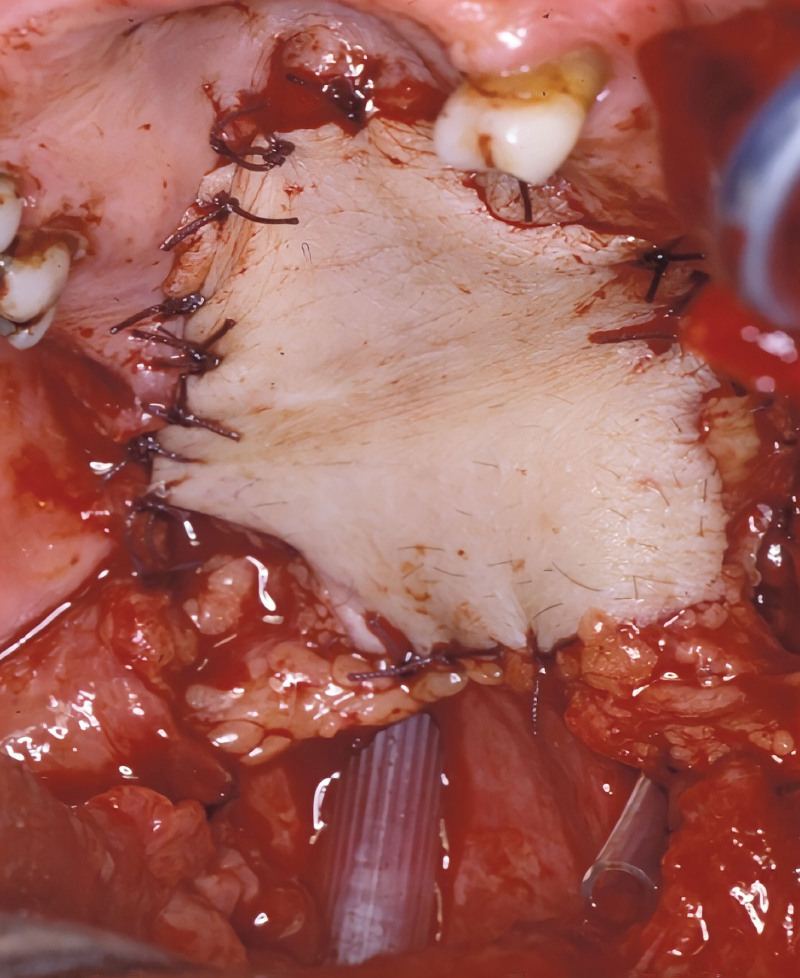

Fig. 5.

Flap insetting.

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of the reconstruction.

After healing, the patients were evaluated with the scoring system of Hirose as far as phonation was concerned, and with the Seattle Questionnaire for swallowing function4 (Tables 1 and 2). Patients were taken in charge by a speech therapist 20 days after surgery for a rehabilitation of about 6 months.

Table 1.

Speech Intelligibility Assessment

| Factors | By Family | By Others |

|---|---|---|

| Clearly understood (no hypernasality) | 5 points | 5 points |

| Occasionally misunderstood (minimal hypernasality) | 4 points | 4 points |

| Understood only when subject is known (mild hypernasality) | 3 points | 3 points |

| Occasionally understood (moderate hypernasality) | 2 points | 2 points |

| Never understood (severe hypernasality) | 1 point | 1 point |

Table 2.

Seattle Questionnaire

| Factors | Score |

|---|---|

| I can swallow as well as ever | 4 points |

| I cannot swallow certain foods (mild regurgitation) | 3 points |

| I can only swallow liquid food (moderate regurgitation) | 2 points |

| I cannot swallow liquids or solids (severe regurgitation) | 1 point |

RESULTS

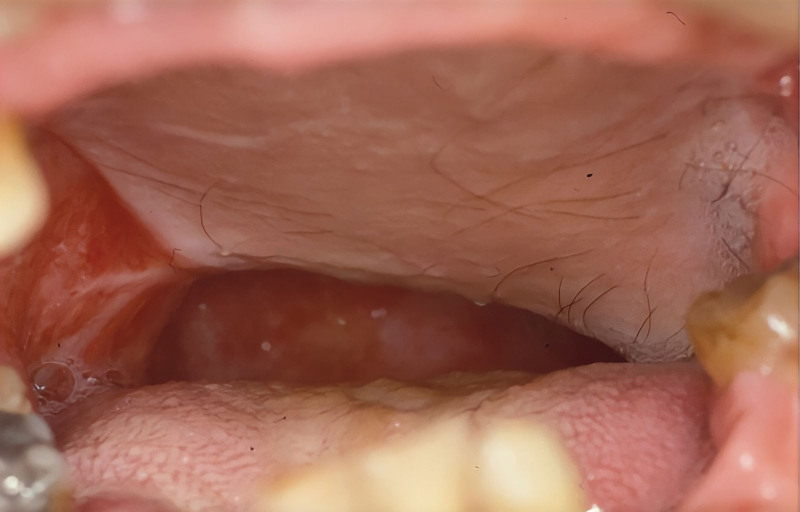

All free flaps survived intact, without any dehiscence or fistula. All three patients showed good short-term morphological-functional outcomes as far as swallowing, breathing, and phonation were concerned (Figs. 7 and 8). Hirose score was eight in two cases, and seven in one case. On the other hand, the score of the Seattle Questionnaire was three in all cases. Over time, thanks to the rehabilitation carried out by the speech therapists, a subjective improvement was reported by all patients.

Fig. 7.

Postoperative MRI (sagittal view).

Fig. 8.

Intraoral postoperative view.

DISCUSSION

Reconstruction of the palatine region after oncological resection can be challenging due to its anatomic and functional pecularities. The primary aim of soft palate reconstruction is to reinstate as much as possible its original function.5 The reconstruction techniques seek thus to reestablish the mass and mucous lining and to achieve good functional recovery of speech, swallowing, and breathing. Local flaps are generally utilized for reconstruction in those cases in which defects make up less than 50% of the palatal surface.6,7 The blood supply and the risk of velopharyngeal dysfunction also need to be considered if the patient has undergone radiotherapy or is a candidate for it. Reconstruction using regional rotation muscle or fasciocutaneous flaps, instead, envisions insetting tissue harvested from regions outside of the aerodigestive tract, in which case the tissue is not mucosal by nature and thus has a different original form and function. The use of a microsurgical flap normally creates the conditions for a more precise reconstruction of the defect, in particular, of those of a larger dimension. The first cases of soft palate reconstruction described in the literature regarded jejunal free flaps used to manage large oropharyngeal defects.8 Other authors described using RFFF to treat isolated defects of the soft palate, including folded RFFF, similarly to the presently reported technique.1,9 The cases reported by such authors in some cases, such as Sinha et al, focus on defects analogous to the ones in the present study. The technique likewise turned out to provide very good outcomes. Some other authors reported on anterolateral thigh flaps used to treat bulky defects.10–12 It should be remembered that the thickness and maneuverability characterizing RFFF facilitate good coverage of palatal defects. As previously stated, soft palate reconstruction aims to achieve two important objectives: to reestablish the function of the pharynx, and to ensure an adequate mucous lining of the areas undergoing demolition in order to prevent, as much as possible, synechia and scar retraction. Several variations of a surgical technique originally described by Urken have been outlined over the years.13 More recently, Lacombe, Biglioli, and Kang have reported on procedures using flaps to reconstruct a part of tonsillar pillars and the oropharynx.1,14,15 Together with other investigators,4,16,17 we are convinced that from a functional point of view, the way to preserve the swallowing reflex and to avoid nasal regurgitation of food is to create a partial adherence of a fraction of the posterior margin of the flap with the back wall of the oropharynx. Intra-oral synechia was avoided in our patients by maintaining the two silicone stents for 30 days during the postoperative period. It should be remembered that the vascular pedicle of the flap needs to be rather long so that it can easily reach the receiving vessels in the neck. It is also important to avoid tortuosity and bottlenecks such as, for example, that represented by the mylohyoid line of the mandible. Such an area may in fact be particularly acute and pronounced at the retromolar trigone. Bone spicules, which may occur, need to be evaluated and, if necessary, treated using a rotary cutting device before anastomosis is carried out as in the cases described here.

CONCLUSIONS

Although our experience with folded RFFF was limited to only three patients, we found it to be an efficacious way to manage localized defects of the soft palate. In all three cases, the patients made a satisfactory recovery as far as the respiratory, phonatory, and, in particular, the swallowing mechanisms were concerned, and velopharyngeal dysfunction was avoided. The RFFF was confirmed to be a versatile solution for those intraoral defects of the soft tissue requiring a limited quantity of volume as in the case of the soft palate.

Footnotes

Published online 6 March 2023.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biglioli F, Brusati R. The folded radial forearm flap in soft-palate and tonsillary fossa reconstruction: technical note. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37:76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta V, Cohan DM, Arshad H, et al. Palatal reconstruction. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;20:225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Britt CJ, Hwang MS, Day AT, et al. A review of and algorithmic approach to soft palate reconstruction. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019;21:332–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JH, Chu HR, Kang JM, et al. Functional benefit after modification of radial forearm free flap for soft palate reconstruction. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;1:161–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sabri A. Oropharyngeal reconstruction: current state of the art. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;11:251–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillespie MB, Eisele DW. The uvulopalatal flap for reconstruction of the soft palate. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:612–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Genden EM, Lee BB, Urken ML. The palatal island flap for reconstruction of palatal and retromolar trigone defects revisited. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:837–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schultz-Coulon HJ, Berger A, Tizian C, et al. Reconstruction of large defects of the oral mucosa with free, revascularized jejunum transplants [in German]. HNO. 1985;33:349–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinha UK, Young P, Hurvitz K, et al. Functional outcomes following palatal reconstruction with a folded radial forearm free flap. Ear Nose Throat J. 2004;83:45–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuchiya S, Nakatsuka T, Sakuraba M. One-sided soft palatal reconstruction with an anterolateral thigh fasciocutaneous flap: report of two cases. Microsurgery. 2011;31:150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyamoto S, Sakuraba M, Nagamatsu S, et al. Combined use of anterolateral thigh flap and pharyngeal flap for reconstruction of extensive soft-palate defects. Microsurgery. 2016;36:291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolff KD, Kesting M, Thurmüller P, et al. The early use of a perforator flap of the lateral lower limb in maxillofacial reconstructive surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:602–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urken ML. Advances in head and neck reconstruction. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1473–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lacombe V, Blackwell KE. Radial forearm free flap for soft palate reconstruction. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 1999;1:130–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang HG, Park MC, Lim H, et al. Modified folding radial forearm flap in soft palate and tonsillar fossa reconstruction. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:458–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCombe D, Lyons B, Winkler R, et al. Speech and swallowing following radial forearm flap reconstruction of major soft palate defects. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:306–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lv M, Shen Y, Li J, et al. Immediate reconstruction of soft palate defects after ablative surgery and evaluation of postoperative function: an analysis of 45 consecutive patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72:1397–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]