Abstract

Introduction:

This study investigated the effect of pictorial cues on autobiographical memory in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). We assessed autobiographical memory of patients with AD and cognitively normal older adults in two conditions.

Methods:

In one condition, the participants were provided with verbal instructions to retrieve three autobiographical memories. In the second condition, the same verbal instructions were provided; however, the participants were simultaneously presented with three pictures. We analyzed autobiographical memory regarding specificity, that is, the ability to remember unique events situated in time and space.

Results:

Analysis demonstrated higher autobiographical memory after verbal-and-visual cuing than after the no cue condition in both patients with AD and cognitively normal older adults.

Discussion:

Pictorial cues seem to be an effective method to alleviate autobiographical compromise in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, autobiographical memory, pictorial cuing, visual cuing

Autobiographical memory, or memory for personal experiences, is compromised in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and this compromise has been associated with a diminished sense of one’s self in the disease (Addis & Tippett, 2004; Fargeau et al., 2010; El Haj & Antoine, 2017a; El Haj, Antoine, Nandrino, & Kapogiannis, 2015; Klein & Gangi, 2010). One main characteristic of autobiographical compromise in AD is over-generality, i.e., diminished ability retrieving specific memories that occurred at a specific time and place (Barnabe et al., 2012; El Haj et al., 2015a; Hou et al., 2005; Martinelli et al., 2013; Muller et al., 2013). This impoverishment has been demonstrated by studies in which AD patients had difficulty retrieving details related to the “who” “where”, “when” and “how” an event originally took place (Dalla Barba et al., 1999; El Haj et al., 2012b, 2015; El Haj & Kapogiannis, 2016; El Haj & Kessels, 2013; Fairfield & Mammarella, 2009; Mammarella et al., 2012; Multhaup & Balota, 1997; Rosa et al., 2016). Interestingly, the difficulty in retrieving specific autobiographical memories in AD has been associated with a shift from the ability to mentally relive past events to a general subjective experience that becomes manifest as a difficulty in adopting a first-person perspective (Irish et al., 2011; Piolino et al., 2003). The difficulty in retrieving specific autobiographical memories has been also associated with a general a sense of familiarity that may be expressed by AD patients as “having experienced this before” (El Haj, Antoine, Nandrino, & Kapogiannis, 2015; Irish et al., 2011; Piolino et al., 2003).

Considering the consequences of autobiographical compromise in AD, we investigated whether use of pictorial cues may enhance autobiographical retrieval in the disease. Autobiographical memory in AD has been widely cued by verbally asking patients to retrieve specific events, and occasionally by providing them with written instructions (Barnabe et al., 2012; El Haj & Antoine, 2017b; Hou et al., 2005; Lalanne et al., 2015; Leyhe et al., 2009; Martinelli et al., 2013; Piolino et al., 2003; Rauchs et al., 2013). Other studies have verbally cued autobiographical memories after exposing patients to musical cues (Foster & Valentine, 2001; El Haj, Antoine, Nandrino, Gely-Nargeot et al., 2015; El Haj et al., 2013, 2012a; Irish et al., 2006). Besides the paucity of research on the effect of pictorial cues on autobiographical memory in AD, our study was motivated by research on the “picture superiority effect”, demonstrating that pictures are remembered better than words (Erdelyi & Becker, 1974; Shepard, 1967; Standing, 1973; Standing et al., 1970). This line of research has also demonstrated that pictures can be easily remembered in a large number of semantically similar foils, suggesting that picture processing results in high-level encoding of visual stimuli, such as in terms of color or shape (Brady et al., 2008). The distinctiveness of pictures, compared with written or verbal stimuli, is believed to lead to better encoding (Israel & Schacter, 1997) and retrieval (Hanczakowski & Mazzoni, 2011). These findings suggest that pictures are more perceptually rich than words, a richness that may be used to better cue autobiographical retrieval in AD.

The hypothesis that pictorial cues may be more beneficial for autobiographical retrieval in AD than verbal cues is further supported by findings suggesting that autobiographical memories come to mind in the form of visual images and that visual images are the main format of autobiographical reliving (Conway, 2009; Greenberg et al., 2005; Rubin, 2005). According to the theoretical model of Conway and Pleydell-Pearce (2000), pictorial cues facilitate autobiographical retrieval by increasing the ease and speed of search through the hierarchical structure of autobiographical memory. This theoretical premise has been supported by studies showing that mental imagery contributes to several phenomenological properties of autobiographical memory, such as memory specificity (Williams et al., 1999), vividness (D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2006; Rubin et al., 2003) and realness (Mazzoni & Memon, 2003). Also, individuals with high capacity for mental imagery were found to retrieve more autobiographical memories than those with low capacity for mental imagery (Vannucci et al., 2016). The role of visual processing in autobiographical memory was also observed in studies demonstrating that autobiographical memory triggers specific eye movements that reflect the visual construction of memories (El Haj et al., 2014, 2017). These findings suggest that visual processing may enhance autobiographical retrieval, a hypothesis that we sought to investigate in regard to AD.

We investigated the effect of visual and verbal cues on autobiographical memory in AD, taking inspiration from studies looking at the same issue in posttraumatic stress disorder and depression, two clinical disorders also characterized by difficulties in accessing specific memories and a tendency to retrieve general memories (Harvey et al., 1998; Sumner, 2012; Williams et al., 2007). Schonfeld and Ehlers (2006) cued autobiographical memories with words and images in participants with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Results showed that pictures facilitated specific memory retrieval in all participants. In a study on depression, Ridout et al. (2016) assessed whether cuing autobiographical memories with images would reduce the memory specificity deficit. The authors cued autobiographical memories of depressed patients and controls with emotional words and images. Results demonstrated that depressed patients retrieved a similar number of specific memories to both images and words, whereas controls retrieved more specific memories to images compared to words. The absence of a positive effect of images on specificity in depressed patients in the study of Ridout et al. (2016) can be attributed to the fact that patients were allocated a very short interval to retrieve memories (30 seconds), in a disease characterized by slowed mental processing. In our paper, this potential issue was taken into account and AD participants were allocated 2 min to retrieve each memory.

In summary, autobiographical compromise in AD is mainly characterized by a difficulty retrieving specific events (Barnabe et al., 2012; El Haj et al., 2015a; Hou et al., 2005; Martinelli et al., 2013; Muller et al., 2013). Our study investigated whether pictorial cues could alleviate this impairment, motivated by research suggesting positive effect of visual processing on autobiographical retrieval in the general population (D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2006; Vannucci et al., 2016) and patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (Schonfeld & Ehlers, 2006). To address the hypothesis that pictures would help AD patients visualize events, leading to better autobiographical retrieval, we compared autobiographical retrieval in AD patients and controls following verbal instructions alone, or verbal instructions combined with visual cues.

Methods

Participants

The study included 27 participants with clinical diagnosis of probable mild AD [18 women and 9 men; Mean (SD) age = 71.67 (5.31) years; years of formal education = 8.63 (2.27)] and 30 control healthy and cognitively normal (CN) older adults [19 women and 11 men; age = 68.80 (8.01) years; years of formal education = 9.27 (4.47)]. The AD participants were recruited from local retirement homes. Probable AD diagnosis was made by an experienced neurologist or geriatrician according to the clinical criteria developed by the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association for probable Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis (McKhann et al., 2011). The control participants were often spouses or companions of AD participants, were independent and living at home. These participants were matched to AD patients according to sex [X2 (1, N = 57) = .37, p > .10], age [t(55) = 1.57, p > .10], and educational level [t(55) = 1.09, p > .10].

Exclusion criteria for all participants were other significant neurological or psychiatric illness and alcohol or drug abuse. No participants presented any major visual or auditory acuity difficulties. All participants provided informed consent and were able to withdraw whenever they wished. Cognitive characteristics of participants were assessed with a comprehensive battery detailed below.

Cognitive characteristics

Cognitive and affective characteristics were evaluated with a battery tapping general cognitive function, episodic memory, working memory, flexibility and depression. General cognitive function was assessed with the Mini-Mental State Exam (Folstein et al., 1975) and the maximum score was 30 points. Episodic memory was assessed with a French version (Van der Linden et al., 2004) of the episodic task by Grober and Buschke (Grober & Buschke, 1987), in which the participants had to retain 16 words, each describing an item from a different semantic category. Immediate cued recall was succeeded by a distraction task, during which participants had to count backwards from 374 in 20 s. This distraction task was succeeded by 2 min of free recall and the score from this task provided a measure of episodic recall (16 points maximum). For working memory assessment, participants were asked to repeat a string of single digits in the same order (i.e., forward spans) or in reverse order (i.e., backward spans). Flexibility was assessed with the Plus–Minus task including three lists, each containing 20 numbers. In List 1, participants had to add one to each number, in List 2 they had to subtract one from each number, and in List 3 they had to add and subtract one alternately. The score referred to the difference between the time participants needed to complete List 3 and the average time that they needed to complete Lists 1 and 2. Depression was assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983) which consists of seven items that were scored by participants on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (not present) to 3 (considerable). The cutoff for definite depression was set at > 10/21 points (Herrmann, 1997).

Procedures

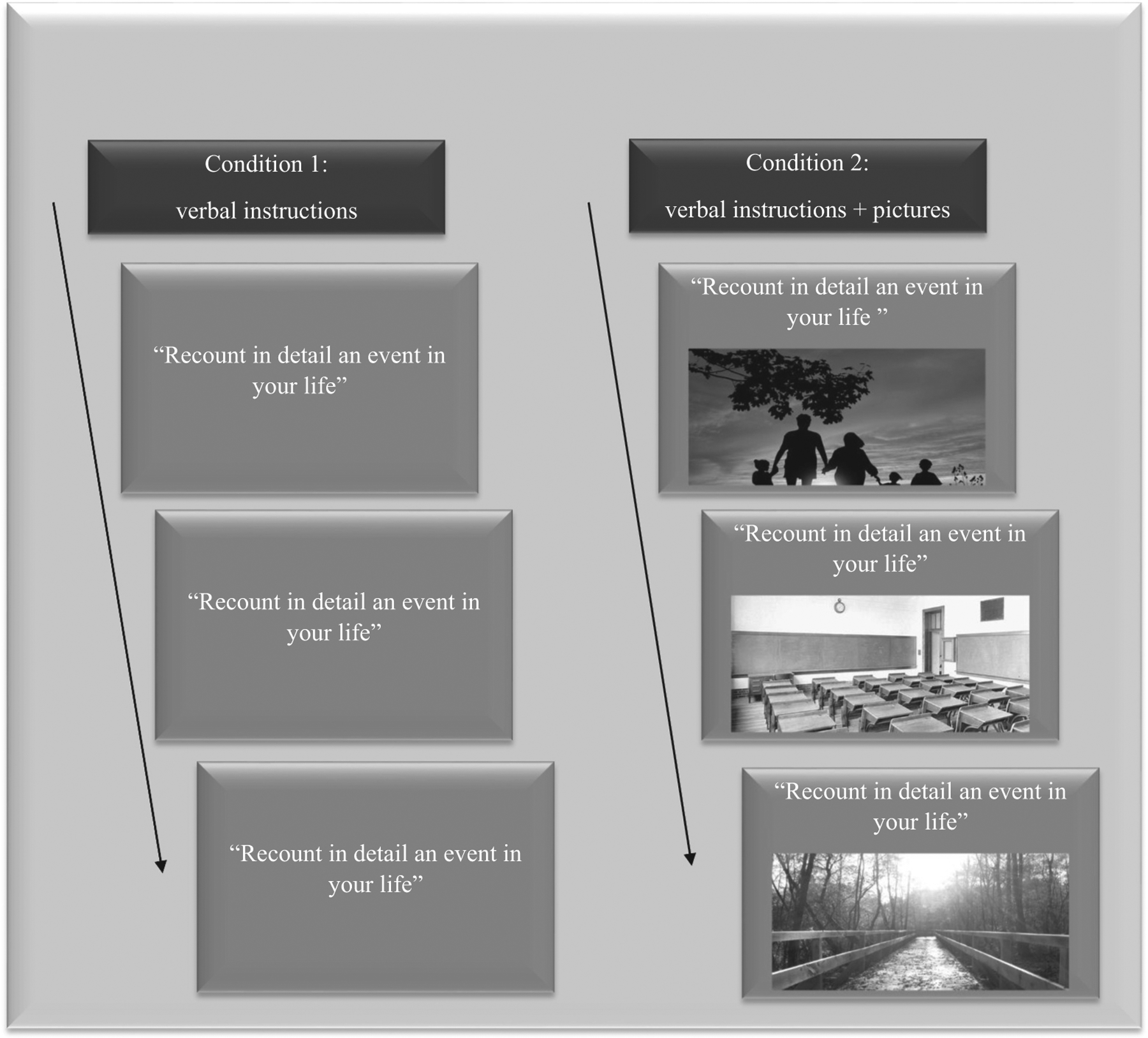

Procedures are depicted in Figure 1. Autobiographical cuing took place in two conditions, the order by which they were administered to participants was counterba-lanced; conditions were separated by approximately 1 week. One condition included no cue condition only and the other condition included verbal and visual cuing simultaneously. In both conditions, we cued three autobiographical memories by asking participants three times to “recount in detail an event in your life ”. Participants were asked to be precise and specific, so events had to have lasted no more than a day and spatiotemporal details had to be provided, such as the time and place at which the events had occurred. Participants were allowed 2 min each time to describe their memories, and the duration was disclosed to them ahead of each task, so that they could structure their memories accordingly. This time limit was adopted to avoid redundancy or distractibility and was found to be sufficient for autobiographical recollection in individuals with AD (El Haj et al., 2015a, 2015b).

Figure 1.

Participants were tested in two conditions. In condition 1, they were verbally asked to retrieve three autobiographical memories. In condition 2, the same verbal instructions were used, however, participants were also asked to look at three pictures.

The difference between the two conditions was that, in the no cue condition, participants were provided only with verbal instructions, whereas in the second condition participants were simultaneously provided with verbal instructions and were asked to look at three pictures; each time the participants were asked to recount a personal event, they had to look at a different picture. The pictures were counterbalanced and chosen according to their attractiveness and ability to cue autobiographical memories. To select suitable pictures, we asked seven different healthy and cognitively normal older adults to examine a set of 20 pictures and rate on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much), the attractiveness of each picture and its ability to cue autobiographical memory. Attractiveness was rated on the following item “this picture is attractive”, while the its ability to cue autobiographical memory was rated on the following item “this picture triggers some personal memories”. The three most highly rated photos (see Figure 1) were used in the study (rating of attractiveness > 2.21, rating of autobiographical cuing > 2.11). The pictures were thus selected based on their attractiveness and their ability to cue autobiographical memory and did not have known salience to the participants. Each picture was printed in the same size, in color, on A4-sized paper. During the second condition, while asking participants to recount in detail a personal event, we also asked them to look at a picture. The participants were free to look elsewhere or even to close their eyes, if they so wished.

Autobiographical specificity was assessed with the TEMPau scale ((Test épisodique de mémoire du passé (Piolino et al., 2002), which was derived from classic autobiographical tests (Kopelman, 1994) and adapted in French. For each retrieved event, we scored zero, if there was no memory or only general information about a theme could be produced; one point for a repeated or an extended event; two points for an event situated in time and/or space; three points for a specific event lasting less than 24 h and situated in time and space; and four points for a specific event situated in time and space enriched with phenomenological details, such as perceptions, feelings, thoughts, or visual imagery. Thus, the maximum specificity score for each memory was four points and the maximum score in each condition was four points × three memories = 12 points. To avoid bias in scoring, a second independent rater rated a random sample of 20% of the data, inter-rater Cohen’s kappa was 0.87; cases of disagreement were discussed until a consensus was reached.

Statistics

Prior to comparing differences on autobiographical specificity, we summarize in Table 1 differences regarding cognitive and affective characteristics (i.e., general cognitive function, episodic memory, working memory, flexibility and depression) between the two groups i.e., AD patients vs. older controls).

Table1.

Cognitive and affective characteristics of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients and cognitively normal older adult participants.

| Task | AD n = 27 |

Older adults n = 30 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| General Cognitive functioning | Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) | 21.44 (1.87)*** | 27.73 (1.55) |

| Episodic memory | Grober and Buschke | 5.63 (2.48)*** | 11.07 (2.91) |

| Working memory | Forward span | 5.44 (1.28)** | 6.80 (1.58) |

| Backward span | 3.70 (1.17)** | 4.87 (1.50) | |

| Flexibility | Plus-Minus | 12.39 (6.37)*** | 5.85 (3.28) |

| Depression | HADS | 8.26 (1.51)*** | 6.13 (2.30) |

Standard deviations are given between parentheses. The maximum MMSE score was 30 points; the maximum score on the Grober and Buschke task was 16 points. Performance on the forward and backward spans refer to the number of correctly repeated digits. Score on the Plus-minus tasks refers to reaction time. The cutoff on the HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) was > 10/21 points. Differences between groups were significant at:

p < .01,

p < .001.

Critically, we compared differences on autobiographical specificity between the two conditions (i.e., no cue condition vs. verbal-and-visual cuing) in the two groups (i.e., AD patients vs. older controls). Owing to the scale nature of the variables and their abnormal distribution, non-parametric tests were conducted. Between-group comparisons were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test and within-group comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Significant results were provided with an effect size [d = .2 can be considered a small effect size, d = .5 represents a medium effect size and d = .8 refers to a large effect size (Cohen, 1988)]. The effect size was calculated for non-parametric tests following recommendations by Rosenthal and DiMatteo (2001), and Ellis (2010). For all tests, level of significance was set as p ≤ 0.05, p values between 0.051 and 0.10 were considered as trends, if any.

Results

Cognitive and affective characteristics

As demonstrated in Table 1, AD participants showed poorer cognitive and clinical performances compared to controls.

Autobiographical memory

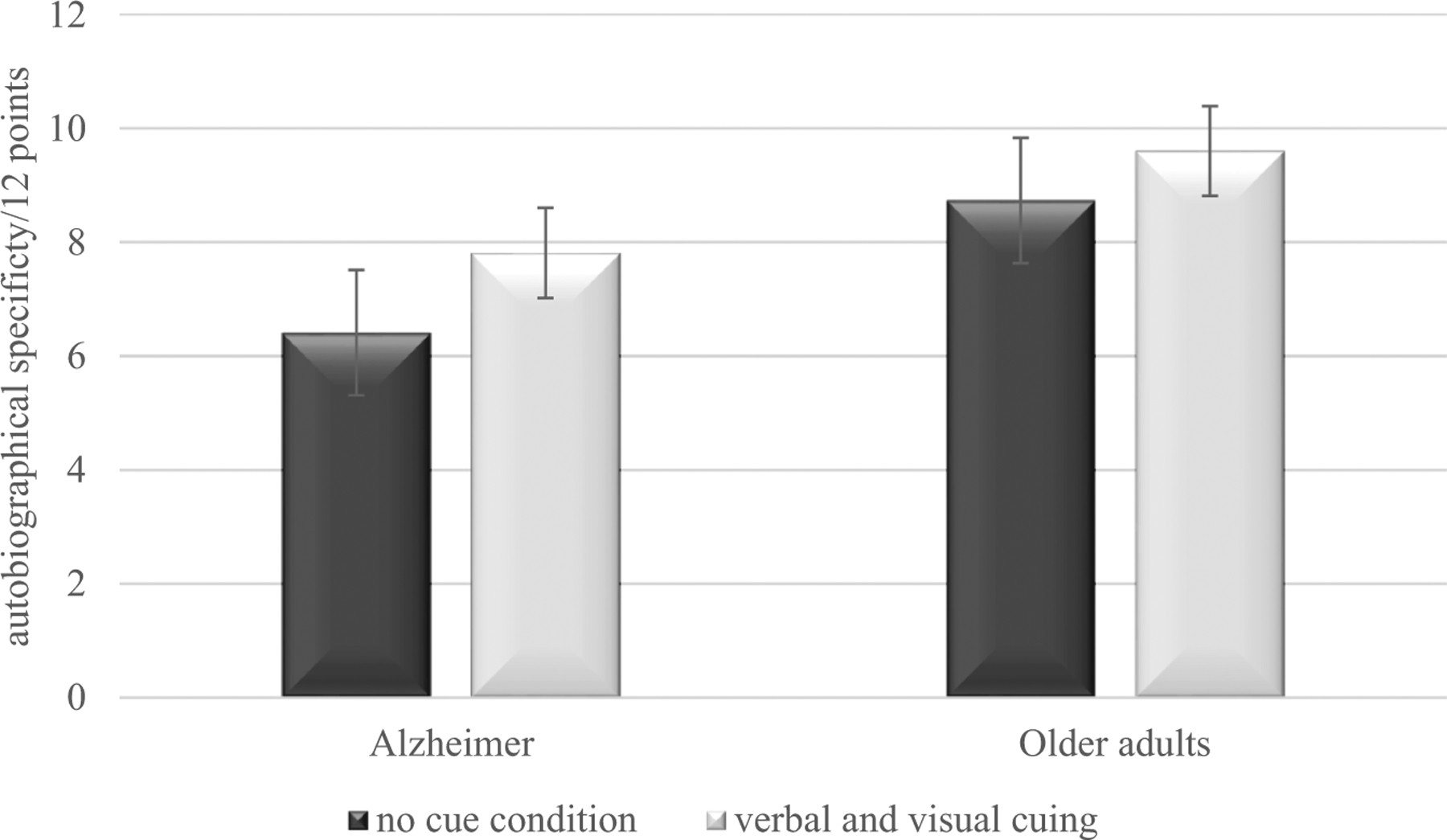

Autobiographical scores are depicted in Figure 2. Relative to controls, AD participants showed lower autobiographical specificity during the no cue condition (Z = −3.67, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.11) and during the verbal-and-visual cuing condition (Z = −3.90, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.20). However, higher specificity was observed during the verbal-and-visual cuing condition than during the verbal condition in AD participants (Z = −2.76, p < .01, Cohen’s d = .78) and controls (Z = −2.61, p < .01, Cohen’s d = .74).

Figure 2.

Autobiographical performance in Alzheimer’s disease and cognitively normal older adults in the no cue condition and in the verbal-and-visual cuing condition. Error bars represent intervals of 95% within-subjects confidence.

Further analysis

We carried out correlation analysis between cognitive and affective characteristics and autobiographical performances in the no cue condition and verbal-and-visual cuing condition. Analysis demonstrated significant positive correlation between scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination and autobiographical performances in the no cue condition (r = .41, p = .033) and verbal-and-visual cuing condition (r = .41, p = .025) in AD patients. Analysis also demonstrated significant positive correlation between scores on the Grober and Buschke test and autobiographical performances in the no cue condition (r = .45, p = .018) and verbal-and-visual cuing condition (r = .42, p = .029) in AD patients. Autobiographical performances in the two conditions were not significantly correlated with the remaining cognitive and clinical tests (i.e., spans, plus-minus, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale). In control participants, autobiographical performances in the two conditions were not significantly correlated with any of the cognitive and clinical tests.

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of verbal and verbal-and-visual cuing on autobiographical memory in AD. In one condition, AD patients and controls were asked verbally to retrieve three autobiographical memories, whereas in the other condition, they were also invited to look at three pictures. Results demonstrated better autobiographical memory, in both groups, after participants were provided with verbal instructions-and-pictures than when provided with only verbal instructions.

One main characteristic of the autobiographical compromise in AD is the diminished ability to retrieve specific memories (Barnabe et al., 2012; El Haj et al., 2015a; Hou et al., 2005; Martinelli et al., 2013; Muller et al., 2013). In line with this, diminished autobiographical memory in AD patients, compared with control participants, was observed when the patients were provided with verbal instructions and pictures, as well as when they were provided with only verbal instructions. This compromise of specificity may have several consequences. According to the AMAD model (Autobiographical Memory in Alzheimer’s Disease model (El Haj, Antoine, Nandrino, & Kapogiannis, 2015), the loss of episodic details (e.g., when, where, or how an autobiographical event took place) leads to a decontextualization of autobiographical memories and a shift from mentally reliving past events to a general sense of familiarity (an experience reported by AD patients as “having experienced this before”). The compromise of specificity in AD has been also associated with a general subjective experience, during which AD patients relive memories as a spectator rather than through their own eyes (Irish et al., 2011; Piolino et al., 2003). To explore a potential therapeutic avenue for the specificity compromise in AD, we investigated how visual cuing can alleviate this deficit.

The most important finding of this study was the higher specificity of autobiographical memory in AD patients when provided with verbal instructions and pictures than when provided with verbal instructions alone. The positive effect of pictures can be attributed to the perceptual salience of these stimuli. Generally speaking, pictures are rich in visual information such as color, shape, and spatial location, and engaging the brain network processing these visual elements is likely to facilitate its engagement with memory retrieval processes and improve the visual construction of memories. This interpretation of our findings can be supported by evidence that autobiographical memories are constructed in the form of visual images, which are the main format of autobiographical reliving (Conway, 2009; Greenberg et al., 2005; Rubin, 2005). In a similar vein, studies demonstrate that visual imagery contributes to several phenomenological properties of autobiographical memory, such as memory specificity (Williams et al., 1999), vividness (D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2006; Rubin et al., 2003) and realness (Mazzoni & Memon, 2003). Therefore, providing AD patients with visual stimuli might have facilitated the creation and manipulation of visual representation of the memories, resulting in better construction and retrieval of the events. Visual cuing might also have alleviated the difficulty AD patients face in integrating components of their autobiographical experience into a coherent visual scene. The latter difficulty was observed in a study, in which AD patients were asked to rate phenomenological characteristics of memories, such as metacognitive judgments (i.e., degree by which a retrieved memory engaged reliving, instilled feelings of being back in time, confidence in remembering, and realness), component processes (i.e., visual imagery, auditory imagery, language, and emotion), and narrative properties (i.e., rehearsal and importance) (El Haj et al., 2016). Among these phenomenological characteristics, AD patients compared to control participants showed the lowest rating for visual imagery, in contrast to auditory imagery or other characteristics. In interpreting this study (El Haj et al., 2016), we speculated that the difficulty of AD patients in constructing visual images of memories results in a visual reconstruction resembling static snapshots akin to photographs or hazy images lacking a real-life three-dimensional quality. Altogether, the evidence suggests that AD patients have specific difficulty in reconstructing visual images of memories, a difficulty that may be alleviated by providing them with pictorial cues.

The effect of pictorial cues on autobiographical memory in AD, as observed in our study, can be compared with a study using SenseCam, a small wearable digital camera and multiple sensors that detect changes in motion, light levels, and ambient temperature. In a study by De Leo et al. (2011), SenseCam was used to record the daily lives of six patients with mild to moderate AD. Better autobiographical recall was observed for events reviewed on the SenseCam (regardless of the motion, light levels, or ambient temperature) compared with the dairy. Another study programmed a smartphone to take pictures of a patient’s life each day for 4 weeks (Woodberry et al., 2014). The pictures were combined into a video and were reviewed by the participant, with results showing better autobiographical recall after watching the video. Overall, pictorial cues seem to be an effective method for alleviating autobiographical compromise in AD.

We also found a positive effect of visual cuing in control participants. These findings are in agreement with a study by Piolino et al. (2006) that demonstrated a diminished ability to relive “in-field” perspective in normal aging. In the study of Piolino et al. (2006), older adults were required to provide a “Field” response, if they mentally “saw” memories through their own eyes, or an “Observer” response if they mentally “saw” themselves in the memory as a spectator would [for more information about this paradigm, see (Nigro & Neisser, 1983)]. The study demonstrated an increase in “Observer” responses and a decrease in “Field” ones with aging, suggesting a diminished ability in older adults to construct memories through their own eyes. In our study, providing control participants with pictorial cues improved their ability to reconstruct images of memories, and consequently, their autobiographical retrieval.

Regarding our correlation analysis, autobiographical performances in the no cue condition and verbal-and-visual cuing condition in AD patients were significantly correlated with scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination and Grober and Buschke test. Thus, general cognitive characteristics in AD, as assessed with the Mini-Mental State Examination, is associated with autobiographical memory, regardless of the cuing condition. Also, autobiographical performances of AD patients, regardless of the cuing condition, are associated with their verbal memory, as assessed with the Grober and Buschke test, not surprisingly as both autobiographical memory and performances on the Grober and Buschke test require verbal production.

The positive effect of pictures, as observed in our study can be attributed to their attractiveness and their ability to cue autobiographical memory, as rated by the independent sample. However, their effect may be also attributed to some salience to some participants. Future research can address this issue by investigating the effects of pictures with personal salience, for instance, by using past images from participants’ life, although such methodology would pose some challenges such as the heterogeneity of stimuli (e.g., differences in colors, differences in degree of salience, difficulties ascertaining degree of salience). That said, future research may create and validate a database of pictures that may be highly effective for autobiographical cuing in AD, which would enable clinicians to incorporate assessment of autobiographical recall into their practice, or even to improve reminiscence therapy by further including pictorial stimuli. It would be also of interest to compare the effects of picture vs. that of other cues, such as auditory ones. Finally, it would be of interest to investigate the effects of visual cuing of the subjective experience of remembering, by inviting, for instance, patients to rate whether the retrieved memories are “remembered” or “known”, or even whether they are retrieved form a “field” or “observer” perspective.

To summarize, our study has demonstrated how a simple procedure may cue autobiographical memories. The use of pictorial cues can be a powerful tool to evoke autobiographical memoires in research and clinical practice. We have all swapped childhood stories at some family gathering to reminisce about the past around a photo album. Our seemingly natural tendency to cue memories with pictures is gaining more and more popularity as, in this digital age, we are witnessing a shift toward using photography as a catalyst for not only reminiscence, but also for peer bonding and social interactions. Taking photographs is no longer an act of memory intended to safeguard a special moment, but is increasingly becoming a tool for identity formation and communication. Therefore, the growing number of AD patients may use pictures not only as a facilitator of remembering, but also as a tool to reestablish their identity by reflecting on how they have grown to become the person they are.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported in part by the LABEX (excellence laboratory, program investment for the future) DISTALZ (Development of Innovative Strategies for a Transdisciplinary approach to Alzheimer disease), in part by the EU Interreg CASCADE 2 Seas Programme 2014–2020 (co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund), and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Addis DR, & Tippett LJ (2004). Memory of myself: Autobiographical memory and identity in Alzheimer’s disease. Memory, 12(1), 56–74. 10.1080/09658210244000423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnabe A, Whitehead V, Pilon R, Arsenault-Lapierre G, & Chertkow H (2012). Autobiographical memory in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: A comparison between the Levine and Kopelman interview methodologies. Hippocampus, 22(9), 1809–1825. 10.1002/hipo.22015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady TF, Konkle T, Alvarez GA, & Oliva A (2008). Visual long-term memory has a massive storage capacity for object details. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(38), 14325–14329. 10.1073/pnas.0803390105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Conway MA (2009). Episodic memories. Neuropsychologia, 47(11), 2305–2313. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway MA, & Pleydell-Pearce CW (2000). The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system. Psychological Review, 107(2), 261–288. 10.1037/0033-295X.107.2.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Argembeau A, & Van der Linden M (2006). Individual differences in the phenomenology of mental time travel: The effect of vivid visual imagery and emotion regulation strategies. Consciousness and Cognition, 15(2), 342–350. 10.1016/j.concog.2005.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Barba G, Nedjam Z, & Dubois B (1999). Confabulation, executive functions, and source memory in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 16 (3–5), 385–398. 10.1080/026432999380843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Leo G, Brivio E, & Sautter SW (2011). Supporting autobiographical memory in patients with Alzheimer’s disease using smart phones. Applied Neuropsychology, 18(1), 69–76. 10.1080/09084282.2011.545730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj M, & Antoine P (2017a). Describe yourself to improve your autobiographical memory: A study in Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex, 88, 165–172. 10.1016/j.cortex.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj M, & Antoine P (2017b). Discrepancy between subjective autobiographical reliving and objective recall: The past as seen by Alzheimer’s disease patients. Consciousness and Cognition, 49, 110–116. 10.1016/j.concog.2017.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj M, Antoine P, & Kapogiannis D (2015a). Flexibility decline contributes to similarity of past and future thinking in Alzheimer’s disease. Hippocampus, 25(11), 1447–1455. 10.1002/hipo.22465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj M, Antoine P, & Kapogiannis D (2015b). Similarity between remembering the past and imagining the future in Alzheimer’s disease: Implication of episodic memory. Neuropsychologia, 66, 119–125. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj M, Antoine P, Nandrino JL, Gely-Nargeot MC, & Raffard S (2015). Self-defining memories during exposure to music in Alzheimer’s disease. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(10), 1719–1730. 10.1017/S1041610215000812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj M, Antoine P, Nandrino JL, & Kapogiannis D (2015). Autobiographical memory decline in Alzheimer’s disease, a theoretical and clinical overview. Ageing Research Reviews, 23(Pt B), 183–192. 10.1016/j.arr.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj M, Clément S, Fasotti L, & Allain P (2013). Effects of music on autobiographical verbal narration in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 26(6), 691–700. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2013.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj M, Delerue C, Omigie D, Antoine P, Nandrino JL, & Boucart M (2014). Autobiographical recall triggers visual exploration. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 7(5), 1–7. 10.16910/jemr.7.5.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj M, Fasotti L, & Allain P (2012a). The involuntary nature of music-evoked autobiographical memories in Alzheimer’s disease. Consciousness and Cognition, 21(1), 238–246. 10.1016/j.concog.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj M, Fasotti L, & Allain P (2012b). Source monitoring in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain and Cognition, 80(2), 185–191. 10.1016/j.bandc.2012.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj M, Fasotti L, & Allain P (2015). Directed forgetting of source memory in normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 27(3), 329–336. 10.1007/s40520-014-0276-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj M, & Kapogiannis D (2016). Time distortions in Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and theoretical integration. Npj Aging and Mechanisms of Disease, 2(1), 16016. 10.1038/npjamd.2016.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj M, Kapogiannis D, & Antoine P (2016). Phenomenological reliving and visual imagery during autobiographical recall in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 52(2), 421–431. 10.3233/JAD-151122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj M, & Kessels RPC (2013). Context memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders Extra, 3(1), 342–350. 10.1159/000354187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj M, Nandrino JL, Antoine P, Boucart M, & Lenoble Q (2017). Eye movement during retrieval of emotional autobiographical memories. Acta psychologica, 174, 54–58. 10.1016/j.actpsy.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis PD (2010). The essential guide to effect sizes: Statistical power, meta-analysis, and the interpretation of research results. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erdelyi MH, & Becker J (1974). Hypermnesia for pictures: Incremental memory for pictures but not words in multiple recall trials. Cognitive Psychology, 6(1), 159–171. 10.1016/0010-0285(74)90008-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fairfield B, & Mammarella N (2009). The role of cognitive operations in reality monitoring: A study with healthy older adults and Alzheimer’s-type dementia. The Journal of General Psychology, 136(1), 21–39. 10.3200/GENP.136.1.21-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fargeau MN, Jaafari N, Ragot S, Houeto JL, Pluchon C, & Gil R (2010). Alzheimer’s disease and impairment of the Self. Consciousness and Cognition, 19(4), 969–976. 10.1016/j.concog.2010.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, & McHugh PR (1975). “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster NA, & Valentine ER (2001). The effect of auditory stimulation on autobiographical recall in dementia. Experimental Aging Research, 27(3), 215–228. 10.1080/036107301300208664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg DL, Eacott MJ, Brechin D, & Rubin DC (2005). Visual memory loss and autobiographical amnesia: A case study. Neuropsychologia, 43(10), 1493–1502. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, & Buschke H (1987). Genuine memory deficits in dementia. Developmental Neuropsychology, 3(1), 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hanczakowski M, & Mazzoni G (2011). Both differences in encoding processes and monitoring at retrieval reduce false alarms when distinctive information is studied. Memory, 19 (3), 280–289. 10.1080/09658211.2011.558514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, Bryant RA, & Dang ST (1998). Autobiographical memory in acute stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(3), 500–506. 10.1037/0022-006X.66.3.500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann C (1997). International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–a review of validation data and clinical results. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 42(1), 17–41. 10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00216-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou CE, Miller BL, & Kramer JH (2005). Patterns of autobiographical memory loss in dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(9), 809–815. 10.1002/gps.1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Cunningham CJ, Walsh JB, Coakley D, Lawlor BA, Robertson IH, & Coen RF (2006). Investigating the enhancing effect of music on autobiographical memory in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 22(1), 108–120. 10.1159/000093487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Lawlor BA, O’Mara SM, & Coen RF (2011). Impaired capacity for autonoetic reliving during autobiographical event recall in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex, 47(2), 236–249. 10.1016/j.cortex.2010.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel L, & Schacter DL (1997). Pictorial encoding reduces false recognition of semantic associates. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 4(4), 577–581. 10.3758/bf03214352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SB, & Gangi CE (2010). The multiplicity of self: Neuropsychological evidence and its implications for the self as a construct in psychological research. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1191, 1–15. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05441.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopelman MD (1994). The Autobiographical Memory Interview (AMI) in organic and psychogenic amnesia. Memory, 2(2), 211–235. 10.1080/09658219408258945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalanne J, Gallarda T, & Piolino P (2015). “The Castle of Remembrance”: New insights from a cognitive training programme for autobiographical memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 25(2), 254–282. 10.1080/09602011.2014.949276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyhe T, Muller S, Milian M, Eschweiler GW, & Saur R (2009). Impairment of episodic and semantic autobiographical memory in patients with mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia, 47(12), 2464–2469. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammarella N, Fairfield B, & Di Domenico A (2012). Comparing different types of source memory attributes in dementia of Alzheimer’s type. International Psychogeriatrics, 24(4), 666–673. 10.1017/S1041610211002274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli P, Anssens A, Sperduti M, & Piolino P (2013). The influence of normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease in autobiographical memory highly related to the self. Neuropsychology, 27(1), 69–78. 10.1037/a0030453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni G, & Memon A (2003). Imagination can create false autobiographical memories. Psychological Science, 14 (2), 186–188. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00020.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr., Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, & Phelps CH (2011). The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 7(3), 263–269. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller S, Saur R, Greve B, Melms A, Hautzinger M, Fallgatter AJ, & Leyhe T (2013). Similar autobiographical memory impairment in long-term secondary progressive multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England), 19(2), 225–232. 10.1177/1352458512450352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multhaup KS, & Balota DA (1997). Generation effects and source memory in healthy older adults and in adults with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neuropsychology, 11(3), 382–391. 10.1037/0894-4105.11.3.382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro G, & Neisser U (1983). Point of view in personal memories. Cognitive Psychology, 15(4), 467–482. 10.1016/0010-0285(83)90016-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piolino P, Desgranges B, Belliard S, Matuszewski V, Lalevee C, De la Sayette V, & Eustache F (2003). Autobiographical memory and autonoetic consciousness: Triple dissociation in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain, 126(Pt 10), 2203–2219. 10.1093/brain/awg222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piolino P, Desgranges B, Benali K, & Eustache F (2002). Episodic and semantic remote autobiographical memory in ageing. Memory, 10(4), 239–257. 10.1080/09658210143000353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piolino P, Desgranges B, Clarys D, Guillery-Girard B, Taconnat L, Isingrini M, & Eustache F (2006). Autobiographical memory, autonoetic consciousness, and self-perspective in aging. Psychology and Aging, 21(3), 510–525. 10.1037/0882-7974.21.3.510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauchs G, Piolino P, Bertran F, de La Sayette V, Viader F, Eustache F, & Desgranges B (2013). Retrieval of recent autobiographical memories is associated with slow-wave sleep in early AD. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 7(114). 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridout N, Dritschel B, Matthews K, & O’Carroll R (2016). Autobiographical memory specificity in response to verbal and pictorial cues in clinical depression. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 51, 109–115. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa NM, Deason RG, Budson AE, & Gutchess AH (2016). Source memory for self and other in patients with mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71(1), 59–65. 10.1093/geronb/gbu062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, & DiMatteo MR (2001). Meta-analysis: Recent developments in quantitative methods for literature reviews. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 59–82. 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC (2005). A basic-systems approach to autobiographical memory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(2), 79–83. 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00339.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC, Schrauf RW, & Greenberg DL (2003). Belief and recollection of autobiographical memories. Memory & Cognition, 31(6), 887–901. 10.3758/BF03196443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonfeld S, & Ehlers A (2006). Overgeneral memory extends to pictorial retrieval cues and correlates with cognitive features in posttraumatic stress disorder. Emotion, 6 (4), 611–621. 10.1037/1528-3542.6.4.611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard RN (1967). Recognition memory for words, sentences, and pictures. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 6(1), 156–163. 10.1016/S0022-5371(67)80067-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Standing L (1973). Learning 10,000 pictures. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 25(2), 207–222. 10.1080/14640747308400340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standing L, Conezio J, & Haber RN (1970). Perception and memory for pictures: Single-trial learning of 2500 visual stimuli. Psychonomic Science, 19(2), 73–74. 10.3758/BF03337426 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner JA (2012). The mechanisms underlying overgeneral autobiographical memory: An evaluative review of evidence for the CaR-FA-X model. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(1), 34–48. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Linden M, Adam S, Agniel A, Baisset- Mouly C, Bardet F, & Coyette F (2004). L’évaluation des troubles de la mémoire: Présentation de quatre tests de mémoire épisodique (avec leur étalonnage) [Evaluation of memory deficits: Presentation of four tests of episodic memory (with standardization)]. Solal Editeurs. [Google Scholar]

- Vannucci M, Pelagatti C, Chiorri C, & Mazzoni G (2016). Visual object imagery and autobiographical memory: Object Imagers are better at remembering their personal past. Memory, 24(4), 455–470. 10.1080/09658211.2015.1018277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM, Barnhofer T, Crane C, Herman D, Raes F, Watkins E, & Dalgleish T (2007). Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 122–148. 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM, Healy HG, & Ellis NC (1999). The effect of imageability and predicability of cues in autobiographical memory. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology A, 52(3), 555–579. 10.1080/713755828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodberry E, Browne G, Hodges S, Watson P, Kapur N, & Woodberry K (2014). The use of a wearable camera improves autobiographical memory in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Memory (ahead-of-print), 23(3), 340–349. 10.1080/09658211.2014.886703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, & Snaith RP (1983). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67 (6), 361–370. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]