Abstract

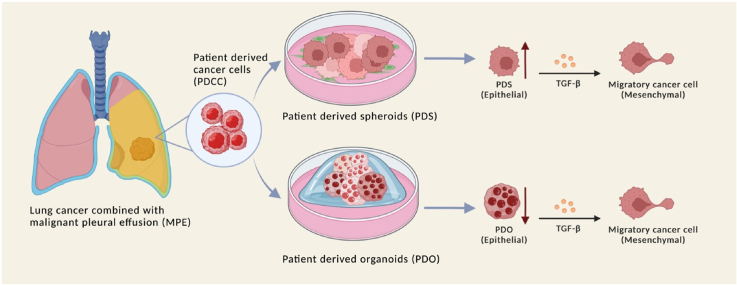

Cancer cells harbor many genetic mutations and gene expression profiles different from normal cells. Patient-derived cancer cells (PDCC) are preferred materials in cancer study. We established patient-derived spheroids (PDSs) and patient-derived organoids (PDOs) from PDCCs isolated from the malignant pleural effusion in 8 patients. The morphologies suggested that PDSs may be a model of local cancer extensions, while PDOs may be a model of distant cancer metastases. The gene expression profiles differed between PDSs and PDOs: Gene sets related to inflammatory responses and EMT were antithetically regulated in PDSs or in PDOs. PDSs demonstrated an attenuation of the pathways that contribute to the enhancement of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) induced epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT), while PDOs demonstrated an attenuation of it. Taken together, PDSs and PDOs have differences in both the interaction to the immune systems and to the stroma. PDSs and PDOs will provide a model system that enable intimate investigation of the behavior of cancer cells in the body.

Keywords: Lung cancer, Spheroid, Organoid, Extracellular matrix, Immune system

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Cancer cells harbor many genetic mutations and gene expression profiles different from normal cells. Studies utilizing cancer cell lines have been a mainstream strategy for elucidating cancer-specific changes. However, cell lines accumulate genetic mutations that occurred during cultivation in vitro and thus diverges from what had been in the patients [17]. Patient-derived cancer cells (PDCCs) and their direct offspring are less affected by such artifacts and may serve as a better material for investigating pathological processes occurring inside the patients. PDCCs has been reported to preserve genetic information and tumor heterogeneity, which is an attractive characteristic in oncology study [40]. Unfortunately, PDCCs are hard to obtain in a large amount and thus are hard to utilize in cancer research.

Malignant pleural effusion (MPE) is a serious complication of lung cancer. There, pleural effusion containing cancer cells accumulate in the thoracic space and necessitates drainage to relieve the compression of heart and lung. We were interested in waste MPE because it contains a large amount of PDCCs that can be used for cancer research [8,19,35,39]. In the previous study, we isolated PDCCs from MPE and investigated the status of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling pathway. At the same time, we found they were hard to cultivate in culture conditions commonly used for cell lines [50]. We thought a lack of cancer stroma may be one of the reasons.

Recently, novel techniques that enable expansion of PDCCs have been developed [29,36,54]. They enable PDCCs and derived biomaterials to serve in oncological investigations [11,45]. Co-culture of PDCCs with the feeder cells provide patient cell-derived spheroids (PDSs) [16,21,28]. PDSs recapitulate physiological and biological identities with original tumors, thus have advantages in studying personalized cancer treatment [46]. Culture of PDCCs in matrix Matrigel provides patient cell-derived organoids (PDOs) [12,60]. PDOs provide 3-dimensional in vitro tumor models and are attractive platform to study the change in tumor properties during its expansion [53]. We thought these techniques may be applicable to PDCCs from MPE.

Clinically, cancer with MPE produces two different types of tumors. One is tumors that expand on the surface of the thoracic wall. The other is tumors formed by the metastases inside distant organs. PDSs are cell congregations formed on the feeder cells and thus may mimic local cancer expansion. PDOs are cell congregations formed in a 3-dimensional matrix that thus may mimic tumor inside distant organs [10,26,48,58]. PDSs and PDOs may be good models for studying biological processes involved in local expansions and distant metastases [4,9].

In the current study, we established PDSs and PDOs from PDCCs. We then investigated the gene expression profiles using the RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) technique. Analyses of the results using bioinformatic tools employing public databases elucidated genes, gene groups, and pathways that were regulated. The results suggested biological mechanisms that will be the foci of future cancer investigations [2,5,62].

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

Cancer cells were obtained between 2019 and 2020 from patients who were hospitalized in the Jichi Medical University Hospital and provided written informed consent according to the protocol approved by the ethical committee of Jichi Medical University (IDEN19-037).

2.2. Patient-derived cancer cell (PDCC)

Cancer cells were isolated from MPE by sedimentation through fetal bovine serum that served as a high-density bouillon [50].

2.3. Patient-cell derived spheroid (PDS)

Mouse 3T3-J2 embryonic fibroblasts (Kerafast, Boston, MA, USA) were irradiated by γ-ray to deprive of the proliferative capacity and seeded on the surface of a flask to form a single cell layer (a feeder cell layer). PDCCs were seeded onto the feeder cell layer at 105 cells/mL in the co-culture medium that was a 2:1 mixture of Nutrient Mixture F-12 Ham (F12; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and Dulbecco's modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich) containing FBS, 5%; hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.4 μg/mL; insulin (FUJIFILM, Wako Pure Chemical Co., Osaka, Japan), 5 μg/mL; cholera toxin (FUJIFILM), 8.4 ng/mL; rH-EGF (SHENANDOAH Biotechnology, Warwick, PA, USA), 10 ng/mL; Adenine (Sigma-Aldrich), 24 μg/mL; and Y-27632 dihydrochloride (Enzo Lifesciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA), 10 μM. Subculture was performed by collecting the cells by pipetting and transferring to a new flask without a feeder layer. At this time, the cells no longer required a feeder cell layer and autonomically proliferated.

2.4. Patient-cell derived organoid (PDO)

Frozen Corning Matrigel matrix (Corning, NY, USA) was melted at 4 °C. Matrix basement media (MBM) was a 1:1 mixture of DMEM/F12 -Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium and Nutrient Mixture F-12 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) containing Gibco bFGF (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 20 ng/mL; EGF, 50 ng/mL; Gibco N-2 MAX Supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1 × ; Gibco B-27 Supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1 × ; ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632), 10 μM; and Penicillin-Streptomycin-Amphotericin B Suspension, 1 × (FUJIFILM). PDCCs were suspended in Corning Matrigel matrix at 107 cells/mL. The suspension was seeded in the prewarmed 24 well culture plate (IWAKA, Tokyo, Japan) and kept at 37 °C for gelation. Then, 500 μL of MBM was added to each well. Media was changed every 4 d. After organoids were formed, they were passaged as follows: Cell recovery solution (Corning) was added to cover the gel and incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. Prechilled phosphate buffer saline (PBS) was added to neutralize the solution. The isolated organoids were completely washed and centrifuged at 1400 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. The steps were repeated until the residual gel was entirely removed. Purified organoids were reseeded in the Matrigel matrix in a new culture plate containing MBM.

2.5. Morphological study

PDCCs, PDSs and PDOs were adhered to slides by centrifugation in Cytospin 4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 2000 rpm for 3 min. Papanicolaou staining and Giemsa staining were performed as described [50]. For immunohistochemistry, cells were reacted with the anti-thyroid transcription factor antibody (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), 10 μg/mL. Bound antibody was visualized with goat anti-rabbit IgG using UltraView DAB Universal kit (Roche Diagnostics K.K., Basel, Swiss) and photographed by Olympus DP74 (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). For immunofluorescence, cells were reacted with anti-cytokeratin 7 monoclonal antibody (LifeSpan BioSciences, Seattle, WA, USA), 10 μg/mL. Bound antibody was visualized with Alexa Fluor™ 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 2 μg/mL. Cell nucleus was stained with Hoechst 33258 (DOJINDO, Kumamoto, Japan), 2 μg/mL. Photographs were taken using Fluoview FV1000 (FV10-ASW, Olympus).

2.6. Total RNA preparation and double strand cDNA synthesis

RNA was isolated from PDCCs, PDSs (2 × 106 cells), and PDOs (1500 organoids) by TRIzol reagents (Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Double strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the PrimeScript™ Double Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TAKARA-Bio, Shiga, Japan). Synthesized cDNA was purified with 1.8 × AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA).

2.7. RNA library construction

Two oligos, K-orgDelA: 5′-Phospho-GATCGGAAGAGCACACGTCTGAACTCCAGTC-3’ (100 μM) and H-org: 5′-ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT-3' (100 μM) were annealed to form a butterfly adaptor that had a nucleotide sequence required to load on the MiSeq system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Synthesized cDNA was 5′ phosphorylated, blunt-ended, and dA tailed in a reaction mixture containing NEBuffer 2.1 (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), 1 × ; ATP (New England Biolabs), 1 mM; dNTP (TAKARA-Bio, Shiga, Japan), 1 mM; T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs), 10 units; and Taq DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs), 5 units by incubating at 37 °C for 30 min then 70 °C for 20 min. The butterfly adaptor was ligated to both ends of cDNA by adding a mixture containing butterfly adaptor, 1 μM; ATP, 1 mM; T4 DNA ligase buffer (New England Biolabs), 1 × ; T4 polynucleotide kinase, 10 units, and T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs), 400 units and incubated at 25 °C for 12 h. The butterfly adaptor-ligated cDNA was purified with 0.7 × AMPure XP into 20 μL of DDW and cDNA was amplified by a PCR reaction containing K-AMP primer: 5′-GACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT-3′, 200 nM; H-AMP primer: 5′-ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT-3′, 200 nM; 1 × PrimeSTAR GXL buffer (TAKARA-Bio); dNTP, 800 nM; and PrimeSTAR® GXL DNA Polymerase, 0.625 units. The PCR cycling was 98 °C for 5 s followed by 25 cycles of 98 °C for 5 s and 68 °C for 30 s. Additional nucleotide sequence required for loading on MiSeq system and an index sequence that discriminated multiple samples were added by PCR reaction using primer 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGAT-(12-bp index)-GGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT-3′ and primer 5′-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACAC-(12-bp index)-ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT-3′, in a reaction mixture containing each primer; 200 nM, 1 × PrimeSTAR GXL buffer (TAKARA-Bio); dNTP, 800 nM; and PrimeSTAR® GXL DNA Polymerase, 0.625 units. The 12-bp index sequence was arbitrarily chosen from the previous report [25]. The PCR cycling was 98 °C for 5 s followed by 25 cycles of 98 °C for 5 s and 68 °C for 30 s. PCR products >300 bp were selected with 0.7 × AMPure XP. Nucleotide sequences were determined by MiSeq using the MiSeq reagent kit v3 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

2.8. RNA sequencing analysis

The CLC genomic workbench version 20.0.4 (Qiagen, Venlo, Nederland) was used for basic manipulation of the data obtained by the MiSeq system, the principal component analysis, the heatmap plot, and the volcano plot. In the heatmap plot and the volcano plot, p < 0.05 was considered significant. Gene annotation files were downloaded from Ensembl. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) version 4.1.0. In the GSEA, FDR-q value < 25% and p value < 0.05 were considered significant. Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) was performed by R based on the TPM (transcription per million) of each sample, gene set was obtained from molecular signatures database C2. Graphics were processed by Adobe Illustrator 2020 (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA) and R studio April 1, 1106. Graphic abstract was constructed using BioRender. Statistical analyses were performed by GraphPad Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Patients

A total of 8 patients were enrolled. All patients had lung cancer with a histology of either adenocarcinoma (LUAD) or small cell carcinoma (LUSC). Patients’ characteristics were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients' characteristics.

| Patient ID | Gender | Age | Pathology | TNM classificationa | Position of distant metastasis | Prior treatment | Cell culture in mediab | Cell culture on feeder layer/in Matrigel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDEN202001 | Male | 50 | Small Cell Carcinoma | T4N3M1a | Pleura | Cisplatin + Etoposide, Amrubicin, Radiotherapy | No growth | PDS/No growth |

| IDEN202002 | Female | 55 | Adenocarcinoma | T1bN3M1a | Pleura | Erlotinib, Bevacizumab + Osimertinib | No growth | PDS/No growth |

| IDEN202003 | Male | 72 | Adenocarcinoma | T2aN2M1a | Pleura | Osimertinib | No growth | No growth/PDO |

| IDEN202004 | Female | 55 | Adenocarcinoma | T2bN3M1c | Lung, Liver, Pleura, Bone, Lung, Spleen | Cisplatin + Vinorelbine, Pembrolizumab, Carboplatin, Pemetrexed, Bevacizumab, Atezolizumab + Paclitaxel | No growth | No growth/PDO |

| IDEN202005 | Female | 64 | Adenocarcinoma | T2bN2M1a | Pleura | Cisplatin + Vinorelbine, Pembrolizumab, Carboplatin, Pemetrexed, Bevacizumab, Atezolizumab + Paclitaxel | No growth | No growth/PDO |

| IDEN202006 | Female | 79 | Adenocarcinoma | T3N3M1c | Liver, Pleura, Bone, Lymph node | Untreated | No growth | No growth/PDO |

| IDEN202007 | Male | 64 | Adenocarcinoma | T4N3M1c | Brain, Liver, Pleural, Bone, Lymph node | Untreated | No growth | No growth/PDO |

| IDEN202008 | Male | 81 | Small Cell Carcinoma | T4N3M1c | Lung, Liver, Pleura, , Bone | Carboplatin + Etoposide | No growth | PDS/No growth |

TNM classification of malignant tumors 8th edition, UICC.

Three different media (1) RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS, (2) supernatant of MPE from where the PDCCs were isolated, and (3) 1:1 mixture of both were tried.

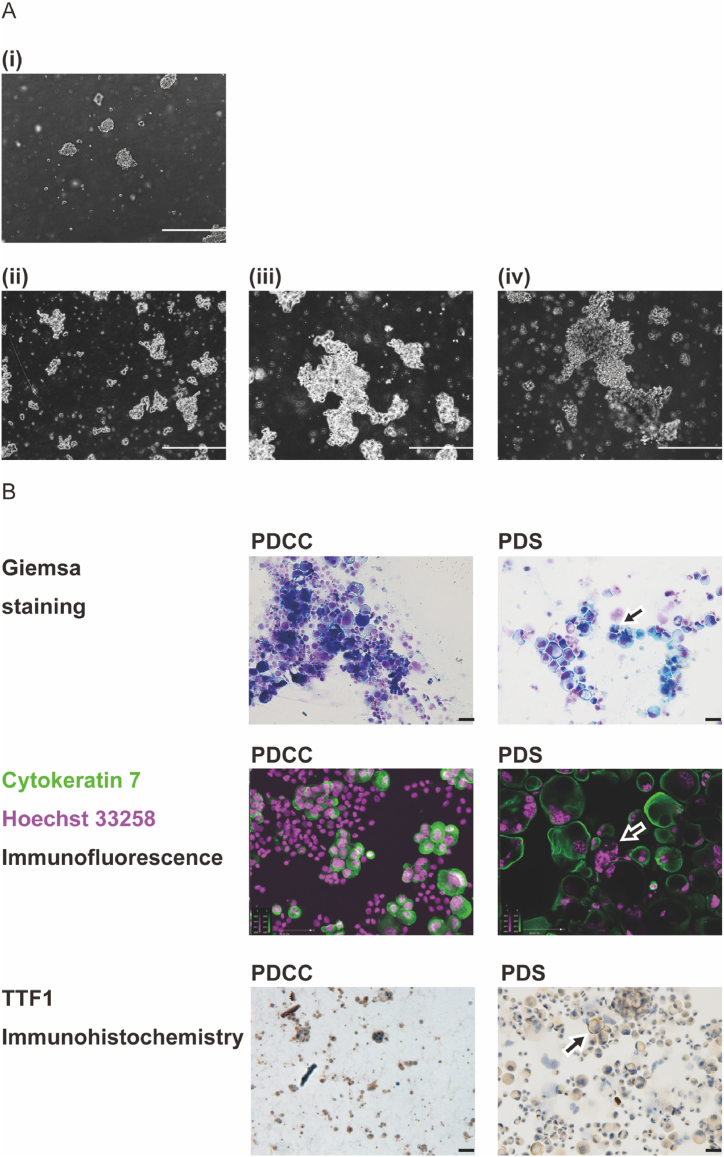

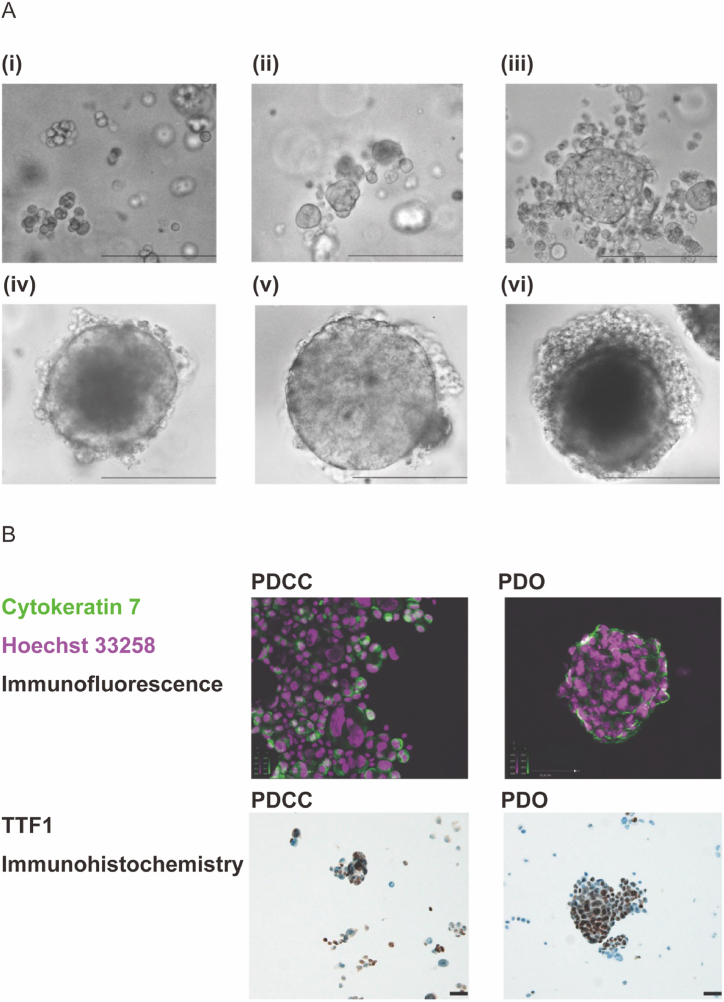

3.2. Primary cell culture, formation of PDS and PDO

In our previous study [50], we tried primary culture of PDCCs in 3 different culture medias: (1) RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS, (2) supernatant of MPE from which the PDCCs were isolated, or (3) 1:1 mixture of both. However, PDCCs grew in none of the media (Supplement Fig. 1A, 1B). This suggested that the interactions with the stroma of the thoracic wall may be indispensable for the cells to grow. In the current study, we cultured PDCCs on a feeder cell layer made of mouse embryonic fibroblasts that provided a 2-dimensional anchorage simulating the surface of thoracic wall. We also cultured PDCCs in Matrigel matrix that provided a 3-dimensional anchorage simulating inside of the organs. We found PDCCs grew well in either condition: the former produced PDSs and the latter produced PDOs. Once PDSs were formed, the cells no longer required a feeder layer and continued to grow without it (Fig. 1A). As passage number increased, PDSs demonstrated a morphology suggestive of more malignant phenotype (Fig. 1B). Once PDOs were formed, it increased in size to a diameter consistent with an organoid (>200 μm) (Fig. 2A) and demonstrated an organ-like structure (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the formation of PDSs and PDOs were mutually exclusive (Table 1); PDCCs that provided PDSs did not provide PDOs and vice versa. This suggested that each PDCC had a tendency to form either a PDS or a PDO.

Fig. 1.

Formation of PDS and its morphology. (A) Observation using a phase contrast microscope. A representative result was shown (patient IDEN 202002). (i) Cells transferred to a flask without a feeder layer (passage 1, day 0). (ii) Cells at passage 1, day 10, (iii) Cells at passage 15, day 10, (iv) Cells at passage 30, day 10. A larger congregation was formed as the passage number increases, suggesting an increased proliferation rate and an advancement to a more malignant phenotype. A scale bar indicates 200 μm. (B) Cell morphology. A representative result was shown (patient IDEN 202002). The appearance of large, multinucleated cells (indicated by an arrow in Giemsa staining, and cytokeratin 7 + Hoechst 33258 double immunofluorescence staining) and a fainter TFF-1 staining (indicated by an arrow) suggests an advancement to a more malignant phenotype. A scale bar indicates 50 μm.

Fig. 2.

Formation of PDO and its morphology. (A) Observation using a phase contrast microscope. A representative result was shown (patient IDEN 202006). (i) PDCCs were embedded in Matrigel matrix (passage 0, day 0). (ii) Cells at passage 0, day 10, (iii) Cells at passage 0, day 20, (iv) Cells after a subculture, at passage 5, day 20. A spherical structure was evident, (v) Cells at passage 10, day 20, (vi) Cells at passage 15, day 20. A scale bar indicates 200 μm. (B) Cell morphology. A representative result was shown (patient IDEN 202006). The cell congregate has a structure and has a diameter consistent of an organoid (i.e., >200 μM). A scale bar indicates 50 μm.

3.3. RNA sequencing

The changes in the RNA expression profiles during the formation of PDSs or PDOs will suggest the biological processes involved. We thus subjected PDSs, PDOs and their parental PDCCs to the RNA-seq analysis. We obtained an average of 163887 cDNA reads per sample. The data were analyzed in the following order: (1) the principal component analysis (PCA) to investigate the gross changes in the expression profile, (2) the heatmap analysis to investigate the expression of each gene, (3) the gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to investigate the expression of sets of genes grouped by the biological processes, and (4) gene set variation analysis (GSVA) to investigate the expression of sets of genes from the biological pathway-centric perspectives.

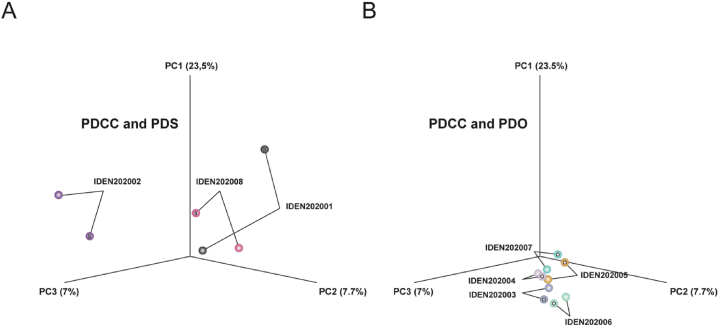

3.4. Principal component analysis (PCA)

The PCA plots the expression profiles in a 3-dimensional space to compare the gross similarity among samples. Here, the distance between PDSs and their parental PDCCs are more than that between PDOs and their parental PDCCs (Fig. 3A and B). This suggested that PDSs had undergone a greater change during their formation than PDOs, which is consistent with the previous report that a contact with the feeder layer re-programs the cells and induces the expression of different sets of genes [50].

Fig. 3.

(A) (B) Principle component analysis (PCA) for PDCCs, PDSs and PDOs. The figure displays a three-dimensional scatter plot of the first three principal components (PCs) of the data based on the log transformed TPM. Each point represents an RNA-Seq sample. Each pair of PDCC and PDS or PDO are clustered together.

3.5. Heatmap plot and volcano plot

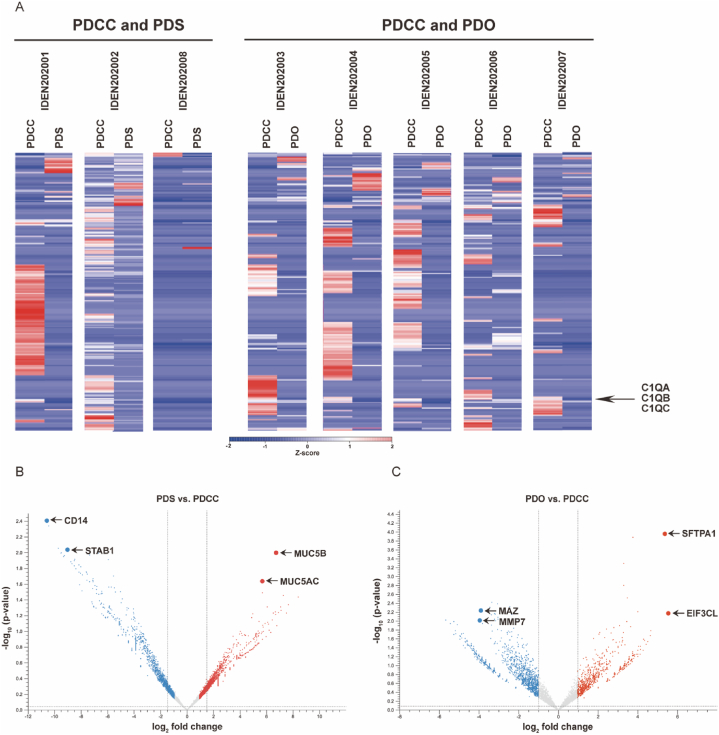

Next, expression profiles of PDSs and PDOs were compared to their parental PDCCs (Fig. 4A and B). Genes similarly regulated in both may be involved in both, while those regulated only in one may be involved in the processes specific to the one.

Fig. 4.

(A) Heatmaps demonstrate the difference in the gene expression profiles. PDS and PDOs were compared to their parental PDCCs. Each column represents a single sample. Upregulated genes were colored by shades of red, while downregulated genes were colored by shades of blue according to the Z-score. (B) (C) Volcano plot demonstrate the difference in the expression of individual genes. PDSs and PDOs were compared to their parental PDCCs. Red plots represented upregulated genes (log2 fold change >1, p value < 0.05). Blue plots represented downregulated genes (log2 fold change >1, p value < 0.05). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.5.1. Genes significantly regulated in both PDSs and PDOs

The only upregulated gene was secretoglobin family 3A member 1 (SCGB3A1; log2 fold change = 8.4, p = 0.04) that specifies epithelium of the distal airway [3,42]. The expression of the gene suggested that PDSs and PDOs developed from the cells that kept characteristics of the distal airway. Downregulated genes (n = 13) included 3 genes that belong to the complement system. They were C1QA (log2 fold change = −9.47, p = 0.01), C1QB (log2 fold change = −10.58; p = 0.004) and C1QC (log2 fold change = −8.04, p = 0.02). Their downregulation has been reported to cause dysfunction of the immune system and thus beneficial for local cancer extension [7].

3.5.2. Genes significantly regulated only in PDSs

Genes upregulated only in PDSs (n = 7) contained mucin 5B (MUC5B; log2 fold change = 6.73, p = 0.01) and mucin 5AC (MUC5AC; log2 fold change = 5.63, p = 0.02) (Fig. 4B). They accumulate in the extracellular matrix (ECM) and provide protection from the outside environment [30,43]. Downregulated genes (n = 96) contained stabiling 1 (STAB1; log2 fold change = −7.34, p = 0.01), a scavenger receptor that suppresses cancer growth and spread [22], and human monocyte differentiation antigen CD14 (log2 fold change = −9.02; p = 0.001), a co-receptor of Toll-like receptor (TLR) that mediates signals elicited by exotic molecules [27,59]. Genes regulated only in PDSs again related to the interaction with the outside environment, pending the GSEA analysis for elucidating the functional gene sets involved.

3.5.3. Genes significantly regulated only in PDOs

Many genes were upregulated (n = 49) or downregulated (n = 110) only in PDOs (Fig. 4C). Among upregulated genes were eukaryotic translation initiation factor subunit 3 (EIF3CL; log2 fold change = 5.55, p = 0.007) that is a promoter of metastasis [13], and lung surfactant protein (SFTPA1; log2 fold change = 5.36, p = 0.0001) that is a key molecule for maintaining cell-airspace interface in the alveoli [64]. Among downregulated genes were myc-associated zinc finger protein (MAZ; log2 fold change = −3.34, p = 0.004) that is a mediator of tumor angiogenesis [49] and matrix metalloproteinase MMP7 (log2 fold change = −3.06; p = 0.004) that is a regulator of breaking down the extracellular matrix [14,65]. Genes related to the outside environment were again listed for PDOs, but the list was different from that of PDSs. The difference may be one of the factors that differentiated PDSs from PDOs, pending the exploration by the GSEA.

3.6. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

The expression of genes with a related function is often regulated as a set. Regulation of a set suggests that the function is regulated in the cells. GSEA is employed to identify such sets.

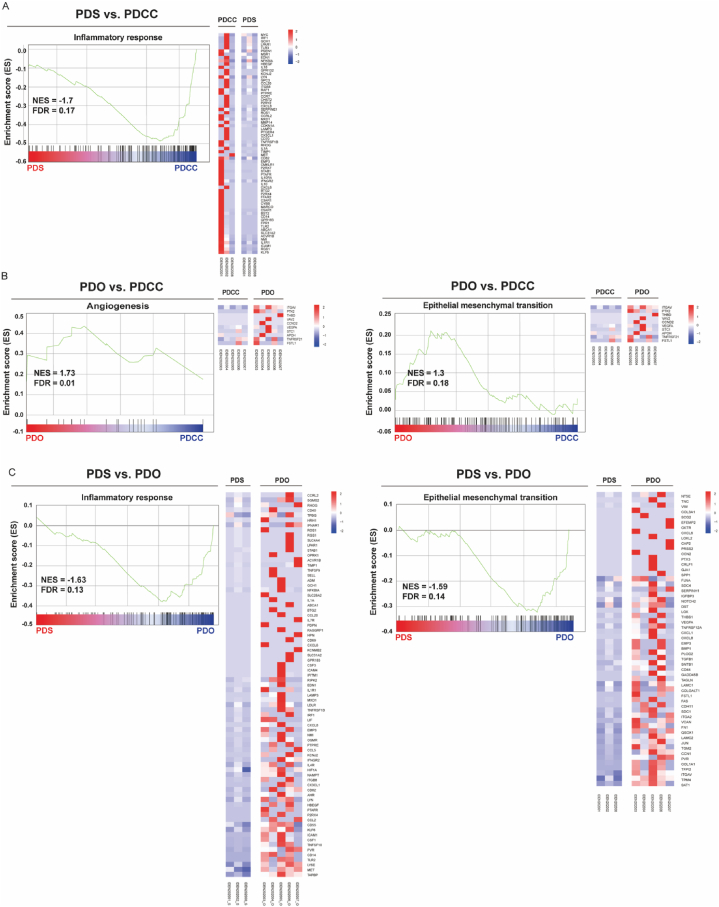

By comparing PDSs and PDCCs, we enriched no biological process that was enhanced in PDSs but found one biological process that was attenuated (Fig. 5A). It was an inflammatory response that includes signaling pathways and biological processes known to be activated in cancer and its stroma [37]. An attenuation of the inflammatory response suggested an attenuation of the anticancer immune response, which may help the cells to expand on the surface of pleura. This supported our speculation that PDSs may be a model of the local tumor extension.

Fig. 5.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). Comparisons were based on the transcripts per million (TPM). (A) PDSs and their originating PDCCs. (B) PDOs and their originating PDCCs. (C) PDSs and PDOs. The green curve shows the enrichment score (ES) for the gene set. The bar at the bottom represents the genes. The far left (red) correlated with the most up-regulated genes and the far right (blue) correlated with the most down-regulated genes, the vertical black lines indicated the position of the gene sets. The heatmap indicated the core enriched gene sets. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

By comparing PDOs and PDCCs, we enriched several biological processes enhanced in PDOs. They were angiogenesis and epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT), cell proliferation and signaling pathways that affect cell growth (Fig. 5B, Supplement Fig. 2A and 2B). Enhancement of these processes may help the cells to intrude into the stroma and distantly metastasize via the tumor vessel [38,44]. This supported our hypothesis that PDOs may be a model of distant metastasis.

Gene sets that differentiated PDSs from PDOs were of our special interest, because the formation of PDSs and PDOs were mutually exclusive (Table 1). We found several biological processes were attenuated in PDSs and enhanced in PDOs, while no processes enhanced in PDSs and attenuated in PDOs. The processes included inflammatory responses and their signaling pathways as well as those related to the EMT (Fig. 5C, Supplement Fig. 2C, 2D, 2E) [31,66]. Taken together, gene sets related to inflammatory responses and EMT were antithetically regulated in PDSs or in PDOs. We further explored through gene set variation analysis (GSVA).

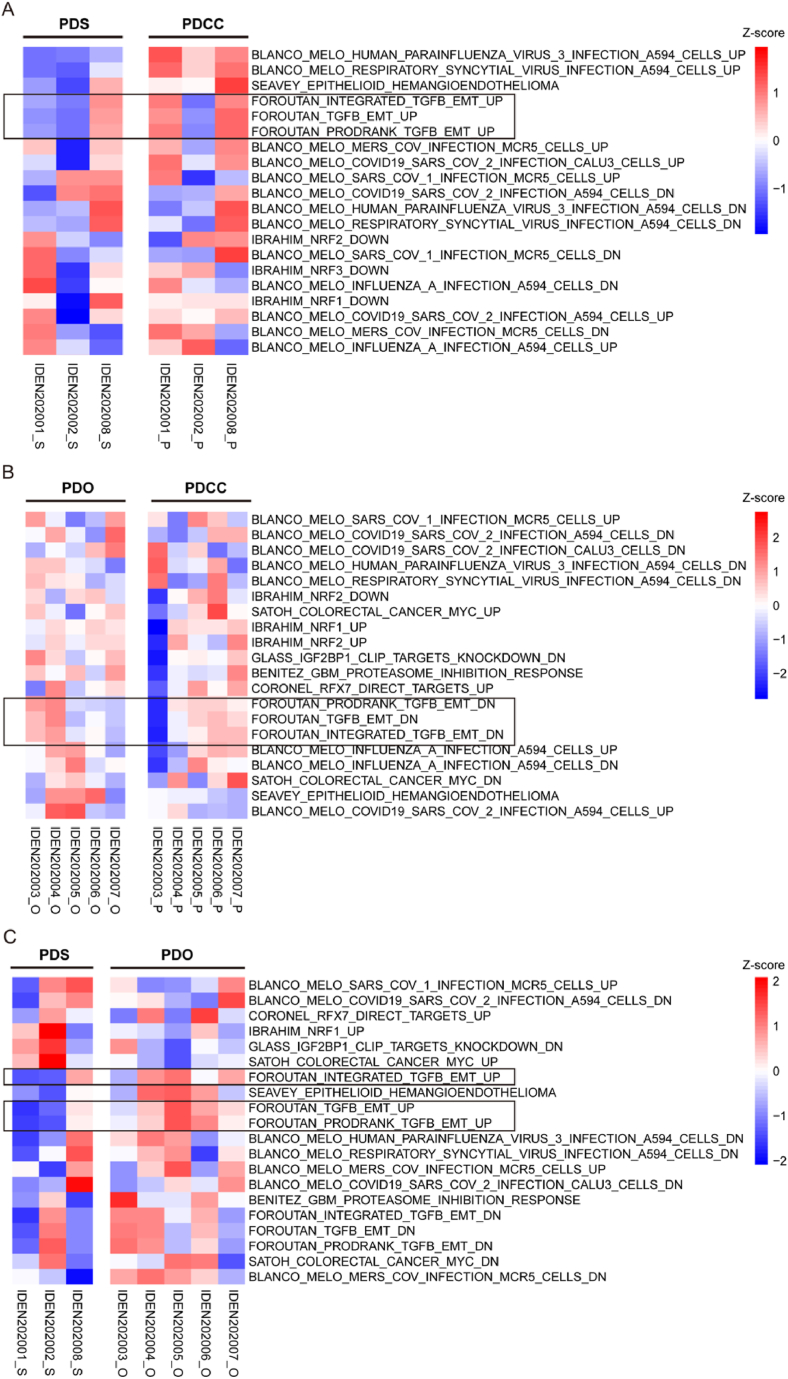

3.7. Gene set variation analysis (GSVA)

GSVA is a pathway-centric analysis that illuminates the pathways regulated [20]. We subjected PDCCs, PDSs and PDOs to the GSVA.

By comparing PDCCs, PDSs demonstrated an attenuation of the pathways that contribute to the enhancement of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) induced epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Fig. 6A), while PDOs demonstrated an attenuation of it (Fig. 6B). The result was further confirmed by the comparison of PDSs and PDO (Fig. 6C). Taken together, PDSs and PDOs have differences in both the interaction to the immune systems and to the stroma.

Fig. 6.

Heatmaps demonstrating the difference in curated gene sets proofed by experts (C2 in MSigDB collections: http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/collections.jsp). (A) PDS and its parental PDCC (B) PDO and its parental PDCC (C) PDS and PDO. Each column represented a single sample. Upregulated pathways were colored by shades of red, while downregulated pathways were colored by shades of blue according to the Z-score. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

Application of PDCCs is a new trend in oncological study [1]. PDCCs conserve bioinformation that reflect tumorigenesis, which is preferable characteristics for studying individualized cancer treatment [63]. In the current study, we used patient-derived cancer cells (PDCCs) isolated from the malignant pleural effusion (MPE), established patient cell-derived spheroids (PDSs), and patient cell-derived organoids (PDOs). Both PDSs or PDOs are direct offspring of PDCCs and are good models for the biological process in vitro. Our results showed the establishment of PDSs and PDOs were mutually exclusive; PDCCs that provided PDSs did not provided PDOs, and vice versa. We subjected PDCCs, PDSs and PDOs to RNA-seq analyses and found that many genes and pathways were regulated. The heatmap, GSEA, and GSVA demonstrated that PDSs were featured by an expression profile that attenuates interaction with the immune system and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and PDOs were by expression profiles that enhances interaction with immune system and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).

There has been literature that reported characterization of spheroids established from lung cancer cell lines or xenografts [23,45]. The list of the genes or pathways that change during the formation of spheroids were partially similar but partially different from ours. For example, EMT-associated genes were enhanced in the spheroid established from A549 cell line, while attenuated in ours [45]. It may be interesting to investigate why such difference occurs. Advantage of the use of MPE is that it is a frequent clinical condition and gives us a chance to establish spheroids from many patients. Furthermore, information of patients' clinical course will be also available. By increasing the numbers of patients, we may have more general overview on what clinical characteristics are represented in PDSs and their gene expression profiles.

PDSs and PDOs should have originated from cancer cells having expression profiles suitable to expand on the irradiated fibroblasts or in the Matrigel matrix. These environments simulate the surface of the thoracic wall or inside of the interstitium, suggesting that the profiles may have an advantage in these environments.

PDCCs used in the current study include both non-small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer. Although non-small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer are histologically different, they may be interchangeable. A significant part of lung cancer has a combined small histology where some part is non-small cell lung cancer and the other part is small cell lung cancer [56], indicating that both histologies may have been derived from the same ancestral cell. Small cell lung cancer transition is one of the frequent mechanisms that confer the acquired resistance to the molecular-targeting drugs [32], suggesting that small cell lung cancer may have resided or emerged from the original tumor. We thus analyzed the expression profiles without discriminating the histology of the ancestral PDCCs. It may also avoid the analyses being affected by the histology-specific features. Accordingly, we were able to extract gene sets that are commonly altered during the formation of PDSs or PDOs.

Interaction with the hosts’ immune system determines the behavior of cancer cells in the body [34]. The immune system not always suppresses tumor proliferation but also promotes tumor progression, depending on the local context of the immune system. Cancer cells may secrete cytokines such as TGF-β [15,41], modify the reactivity of immune cells, and may promote cancer [61,67]. Comparison of PDSs and PDOs focusing on the interaction with the immune system will elucidate the genes that contribute to the local invasion or to the distant metastases.

PDSs and PDOs are direct descendants of PDCCs after only a few dozens of cell divisions. PDCCs have advantages in personalizing the therapeutical strategy. PDSs and PDOs construct platforms to mimic the in vivo tumorigenesis processes and reproduce the interaction of cancer cells to the microenvironment and forecast the cancer development [18,33,51,52,57]. PDSs and PDOs bridge the in vivo and in vitro study and clue the clinical and the biological phenomenon [6,19,24,47,55]. Our study suggested that they provide attracting models for analyzing the behavior of cancer cells and research seeds that contribute to both basic and clinical studies.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Surina: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Tanggis, Shu Hisata, Kazutaka Fujita, Satomi Fujiwara, Noriyoshi Fukushima: Performed the experiments.

Fangyuan Liu: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Takuji Suzuki, Naoko Mato: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Koichi Hagiwara: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific external grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. All researches were done using the research fund of Jichi Medical University.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13829.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Amini L., Silbert S.K., Maude S.L., Nastoupil L.J., Ramos C.A., Brentjens R.J., Sauter C.S., Shah N.N., Abou-El-Enein M. Preparing for CAR T cell therapy: patient selection, bridging therapies and lymphodepletion. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022;19:342–355. doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00607-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banda M., McKim K.L., Myers M.B., Inoue M., Parsons B.L. Outgrowth of erlotinib-resistant subpopulations recapitulated in patient-derived lung tumor spheroids and organoids. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basil M.C., Cardenas-Diaz F.L., Kathiriya J.J., Morley M.P., Carl J., Brumwell A.N., Katzen J., Slovik K.J., Babu A., Zhou S., Kremp M.M., McCauley K.B., Li S., Planer J.D., Hussain S.S., Liu X., Windmueller R., Ying Y., Stewart K.M., Oyster M., Christie J.D., Diamond J.M., Engelhardt J.F., Cantu E., Rowe S.M., Kotton D.N., Chapman H.A., Morrisey E.E. Human distal airways contain a multipotent secretory cell that can regenerate alveoli. Nature. 2022;604:120–126. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04552-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleijs M., van de Wetering M., Clevers H., Drost J. Xenograft and organoid model systems in cancer research. EMBO J. 2019;38 doi: 10.15252/embj.2019101654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boucherit N., Gorvel L., Olive D. 3D tumor models and their use for the testing of immunotherapies. Front. Immunol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.603640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calejo I., Heinrich M.A., Zambito G., Mezzanotte L., Prakash J., Moreira Teixeira L. Advancing tumor microenvironment research by combining organs-on-chips and biosensors. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2022;1379:171–203. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-04039-9_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L.-H., Liu J.-F., Lu Y., He X.-Y., Zhang C., Zhou H.-H. Complement C1q (C1qA, C1qB, and C1qC) may Be a potential prognostic factor and an index of tumor microenvironment remodeling in osteosarcoma. Front. Oncol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.642144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y., Mathy N.W., Lu H. The role of VEGF in the diagnosis and treatment of malignant pleural effusion in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (Review) Mol. Med. Rep. 2018;17:8019–8030. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Correa B.R.S., Hu J., Penalva L.O.F., Schlegel R., Rimm D.L., Galante P.A.F., Agarwal S. Patient-derived conditionally reprogrammed cells maintain intra-tumor genetic heterogeneity. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:4097. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22427-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dijkstra K.K., Monkhorst K., Schipper L.J., Hartemink K.J., Smit E.F., Kaing S., de Groot R., Wolkers M.C., Clevers H., Cuppen E., Voest E.E. Challenges in establishing pure lung cancer organoids limit their utility for personalized medicine. Cell Rep. 2020;31 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding S., Hsu C., Wang Z., Natesh N.R., Millen R., Negrete M., Giroux N., Rivera G.O., Dohlman A., Bose S., Rotstein T., Spiller K., Yeung A., Sun Z., Jiang C., Xi R., Wilkin B., Randon P.M., Williamson I., Nelson D.A., Delubac D., Oh S., Rupprecht G., Isaacs J., Jia J., Chen C., Shen J.P., Kopetz S., McCall S., Smith A., Gjorevski N., Walz A.-C., Antonia S., Marrer-Berger E., Clevers H., Hsu D., Shen X. Patient-derived micro-organospheres enable clinical precision oncology. Cell Stem Cell. 2022;29:905–917.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2022.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dost A.F.M., Moye A.L., Vedaie M., Tran L.M., Fung E., Heinze D., Villacorta-Martin C., Huang J., Hekman R., Kwan J.H., Blum B.C., Louie S.M., Rowbotham S.P., Sainz de Aja J., Piper M.E., Bhetariya P.J., Bronson R.T., Emili A., Mostoslavsky G., Fishbein G.A., Wallace W.D., Krysan K., Dubinett S.M., Yanagawa J., Kotton D.N., Kim C.F. Organoids model transcriptional hallmarks of oncogenic KRAS activation in lung epithelial progenitor cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;27:663–678.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esteves P., Dard L., Brillac A., Hubert C., Sarlak S., Rousseau B., Dumon E., Izotte J., Bonneu M., Lacombe D., Dupuy J.-W., Amoedo N., Rossignol R. Nuclear control of lung cancer cells migration, invasion and bioenergetics by eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3F. Oncogene. 2020;39:617–636. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-1009-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang Y.-J., Lu Z.-H., Wang F., Wu X.-J., Li L.-R., Zhang L.-Y., Pan Z.-Z., Wan D.-S. Prognostic impact of ERβ and MMP7 expression on overall survival in colon cancer. Tumour Biol. J. Int. Soc. Oncodevelopmental Biol. Med. 2010;31:651–658. doi: 10.1007/s13277-010-0082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gajewski T.F., Schreiber H., Fu Y.-X. Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:1014–1022. doi: 10.1038/ni.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao J., Song T., Che D., Li C., Jiang J., Pang J., Yang Y., Goma null, Li P. The effect of bisphenol a exposure onto endothelial and decidualized stromal cells on regulation of the invasion ability of trophoblastic spheroids in in vitro co-culture model. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019;516:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gazdar A.F., Gao B., Minna J.D. Lung cancer cell lines: useless artifacts or invaluable tools for medical science?, Lung Cancer Amst. Net. 2010;68:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guillen K.P., Fujita M., Butterfield A.J., Scherer S.D., Bailey M.H., Chu Z., DeRose Y.S., Zhao L., Cortes-Sanchez E., Yang C.-H., Toner J., Wang G., Qiao Y., Huang X., Greenland J.A., Vahrenkamp J.M., Lum D.H., Factor R.E., Nelson E.W., Matsen C.B., Poretta J.M., Rosenthal R., Beck A.C., Buys S.S., Vaklavas C., Ward J.H., Jensen R.L., Jones K.B., Li Z., Oesterreich S., Dobrolecki L.E., Pathi S.S., Woo X.Y., Berrett K.C., Wadsworth M.E., Chuang J.H., Lewis M.T., Marth G.T., Gertz J., Varley K.E., Welm B.E., Welm A.L. A human breast cancer-derived xenograft and organoid platform for drug discovery and precision oncology. Nat. Can. (Que.) 2022;3:232–250. doi: 10.1038/s43018-022-00337-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guinde J., Georges S., Bourinet V., Laroumagne S., Dutau H., Astoul P. Recent developments in pleurodesis for malignant pleural disease. Clin. Res. J. 2018;12:2463–2468. doi: 10.1111/crj.12958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hänzelmann S., Castelo R., Guinney J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinf. 2013;14:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haridas P., Penington C.J., McGovern J.A., McElwain D.L.S., Simpson M.J. Quantifying rates of cell migration and cell proliferation in co-culture barrier assays reveals how skin and melanoma cells interact during melanoma spreading and invasion. J. Theor. Biol. 2017;423:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hollmén M., Figueiredo C.R., Jalkanen S. New tools to prevent cancer growth and spread: a “Clever” approach. Br. J. Cancer. 2020;123:501–509. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-0953-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong H.K., Pyo D.H., Kim T.W., Yun N.H., Lee Y.S., Song S.J., Lee W.Y., Cho Y.B. Efficient primary culture model of patient-derived tumor cells from colorectal cancer using a Rho-associated protein kinase inhibitor and feeder cells. Oncol. Rep. 2019;42:2029–2038. doi: 10.3892/or.2019.7285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang L., Rong Y., Tang X., Yi K., Qi P., Hou J., Liu W., He Y., Gao X., Yuan C., Wang F. Engineered exosomes as an in situ DC-primed vaccine to boost antitumor immunity in breast cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2022;21:45. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01515-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inoue Y., Shiihara J., Miyazawa H., Ohta H., Higo M., Nagai Y., Kobayashi K., Saijo Y., Tsuchida M., Nakayama M., Hagiwara K. A highly specific and sensitive massive parallel sequencer-based test for somatic mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin M.-Z., Han R.-R., Qiu G.-Z., Ju X.-C., Lou G., Jin W.-L. Organoids: an intermediate modeling platform in precision oncology. Cancer Lett. 2018;414:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawasaki T., Kawai T. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:461. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim S.-A., Lee E.K., Kuh H.-J. Co-culture of 3D tumor spheroids with fibroblasts as a model for epithelial-mesenchymal transition in vitro. Exp. Cell Res. 2015;335:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koshkin S., Danilova A., Raskin G., Petrov N., Bajenova O., O'Brien S.J., Tomilin A., Tolkunova E. Primary cultures of human colon cancer as a model to study cancer stem cells. Tumour Biol. J. Int. Soc. Oncodevelopmental Biol. Med. 2016;37:12833–12842. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakshmanan I., Rachagani S., Hauke R., Krishn S.R., Paknikar S., Seshacharyulu P., Karmakar S., Nimmakayala R.K., Kaushik G., Johansson S.L., Carey G.B., Ponnusamy M.P., Kaur S., Batra S.K., Ganti A.K. MUC5AC interactions with integrin β4 enhances the migration of lung cancer cells through FAK signaling. Oncogene. 2016;35:4112–4121. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawal B., Tseng S.-H., Olugbodi J.O., Iamsaard S., Ilesanmi O.B., Mahmoud M.H., Ahmed S.H., Batiha G.E.-S., Wu A.T.H. Pan-cancer analysis of immune complement signature C3/C5/C3AR1/C5AR1 in association with tumor immune evasion and therapy resistance. Cancers. 2021;13:4124. doi: 10.3390/cancers13164124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leonetti A., Minari R., Mazzaschi G., Gnetti L., La Monica S., Alfieri R., Campanini N., Verzè M., Olivani A., Ventura L., Tiseo M. Small cell lung cancer transformation as a resistance mechanism to osimertinib in epidermal growth factor receptor-mutated lung adenocarcinoma: case report and literature review. Front. Oncol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.642190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu S., Wang T., Li S., Wang X. Application status of sacrificial biomaterials in 3D bioprinting. Polymers. 2022;14:2182. doi: 10.3390/polym14112182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y., Cao X. Immunosuppressive cells in tumor immune escape and metastasis. J. Mol. Med. Berl. Ger. 2016;94:509–522. doi: 10.1007/s00109-015-1376-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marquez-Medina D., Popat S. Closing faucets: the role of anti-angiogenic therapies in malignant pleural diseases. Clin. Transl. Oncol. Off. Publ. Fed. Span. Oncol. Soc. Natl. Cancer Inst. Mex. 2016;18:760–768. doi: 10.1007/s12094-015-1464-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Namekawa T., Ikeda K., Horie-Inoue K., Inoue S. Application of prostate cancer models for preclinical study: advantages and limitations of cell lines, patient-derived xenografts, and three-dimensional culture of patient-derived cells. Cells. 2019;8:74. doi: 10.3390/cells8010074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neagu M., Zipeto D., Popescu I.D. Inflammation in cancer: Part of the problem or part of the solution? J. Immunol. Res. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/5403910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishida N., Yano H., Nishida T., Kamura T., Kojiro M. Angiogenesis in cancer, vasc. Healthc. Risk Manag. 2006;2:213–219. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.2006.2.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Numico G., Cristofano A., Occelli M., Sicuro M., Mozzicafreddo A., Fea E., Colantonio I., Merlano M., Piovano P., Silvestris N. Prolonged drainage and intrapericardial bleomycin administration for cardiac tamponade secondary to cancer-related pericardial effusion. Medicine (Baltim.) 2016;95 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poonpanichakul T., Shiao M.-S., Jiravejchakul N., Matangkasombut P., Sirachainan E., Charoensawan V., Jinawath N. Capturing tumour heterogeneity in pre- and post-chemotherapy colorectal cancer ascites-derived cells using single-cell RNA-sequencing. Biosci. Rep. 2021;41 doi: 10.1042/BSR20212093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quatromoni J.G., Eruslanov E. Tumor-associated macrophages: function, phenotype, and link to prognosis in human lung cancer. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2012;4:376–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reynolds S.D., Reynolds P.R., Pryhuber G.S., Finder J.D., Stripp B.R. Secretoglobins SCGB3A1 and SCGB3A2 define secretory cell subsets in mouse and human airways. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002;166:1498–1509. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200204-285OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rico S.D., Mahnken M., Büscheck F., Dum D., Luebke A.M., Kluth M., Hube-Magg C., Hinsch A., Höflmayer D., Möller-Koop C., Fraune C., Möller K., Menz A., Bernreuther C., Jacobsen F., Lebok P., Clauditz T.S., Sauter G., Uhlig R., Wilczak W., Simon R., Steurer S., Minner S., Burandt E., Krech T., Marx A.H. MUC5AC expression in various tumor types and nonneoplastic tissue: a tissue microarray study on 10 399 tissue samples. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021;20 doi: 10.1177/15330338211043328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roche J. The epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cancer. Cancers. 2018;10:52. doi: 10.3390/cancers10020052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roudi R., Madjd Z., Ebrahimi M., Najafi A., Korourian A., Shariftabrizi A., Samadikuchaksaraei A. Evidence for embryonic stem-like signature and epithelial-mesenchymal transition features in the spheroid cells derived from lung adenocarcinoma. Tumor Biol. 2016;37:11843–11859. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5041-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rozenberg J.M., Filkov G.I., Trofimenko A.V., Karpulevich E.A., Parshin V.D., Royuk V.V., Sekacheva M.I., Durymanov M.O. Biomedical applications of non-small cell lung cancer spheroids. Front. Oncol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.791069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Serratì S., Guida M., Di Fonte R., De Summa S., Strippoli S., Iacobazzi R.M., Quarta A., De Risi I., Guida G., Paradiso A., Porcelli L., Azzariti A. Circulating extracellular vesicles expressing PD1 and PD-L1 predict response and mediate resistance to checkpoint inhibitors immunotherapy in metastatic melanoma. Mol. Cancer. 2022;21:20. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01490-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi R., Radulovich N., Ng C., Liu N., Notsuda H., Cabanero M., Martins-Filho S.N., Raghavan V., Li Q., Mer A.S., Rosen J.C., Li M., Wang Y.-H., Tamblyn L., Pham N.-A., Haibe-Kains B., Liu G., Moghal N., Tsao M.-S. Organoid cultures as preclinical models of non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2020;26:1162–1174. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smits M., Wurdinger T., van het Hof B., Drexhage J.A.R., Geerts D., Wesseling P., Noske D.P., Vandertop W.P., de Vries H.E., Reijerkerk A. Myc-associated zinc finger protein (MAZ) is regulated by miR-125b and mediates VEGF-induced angiogenesis in glioblastoma. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2012;26:2639–2647. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-202820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Surina M., Sata Tanggis, Fujiwara S., Hisata S., Suzuki T., Mato N., Hagiwara K. Cultivation of cancer cells in malignant pleural effusion and their use in a vascular endothelial growth factor study. Ann. Cancer Res. Ther. 2020;28:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takano A., Koh I., Hagiwara M. 3D culture platform for enabling large-scale imaging and control of cell distribution into complex shapes by combining 3D printing with a cube device. Micromachines. 2022;13:156. doi: 10.3390/mi13020156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tran C.G., Borbon L.C., Mudd J.L., Abusada E., AghaAmiri S., Ghosh S.C., Vargas S.H., Li G., Beyer G.V., McDonough M., Li R., Chan C.H.F., Walsh S.A., Wadas T.J., O'Dorisio T., O'Dorisio M.S., Govindan R., Cliften P.F., Azhdarinia A., Bellizzi A.M., Fields R.C., Howe J.R., Ear P.H. Establishment of novel neuroendocrine carcinoma patient-derived xenograft models for receptor peptide-targeted therapy. Cancers. 2022;14:1910. doi: 10.3390/cancers14081910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tran E., Shi T., Li X., Chowdhury A.Y., Jiang D., Liu Y., Wang H., Yan C., Wallace W.D., Lu R., Ryan A.L., Marconett C.N., Zhou B., Borok Z., Offringa I.A. Development of human alveolar epithelial cell models to study distal lung biology and disease. iScience. 2022;25 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.103780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsai S., McOlash L., Palen K., Johnson B., Duris C., Yang Q., Dwinell M.B., Hunt B., Evans D.B., Gershan J., James M.A. Development of primary human pancreatic cancer organoids, matched stromal and immune cells and 3D tumor microenvironment models. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:335. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4238-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vivas A., van den Berg A., Passier R., Odijk M., van der Meer A.D. Fluidic circuit board with modular sensor and valves enables stand-alone, tubeless microfluidic flow control in organs-on-chips. Lab Chip. 2022;22:1231–1243. doi: 10.1039/d1lc00999k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wagner P.L., Kitabayashi N., Chen Y.-T., Saqi A. Combined small cell lung carcinomas: genotypic and immunophenotypic analysis of the separate morphologic components. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2009;131:376–382. doi: 10.1309/AJCPYNPFL56POZQY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang D., Guo Y., Zhu J., Liu F., Xue Y., Huang Y., Zhu B., Wu D., Pan H., Gong T., Lu Y., Yang Y., Wang Z. Hyaluronic acid methacrylate/pancreatic extracellular matrix as a potential 3D printing bioink for constructing islet organoids. Acta Biomater. 2022:S1742–S7061. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.06.036. 22 00375–0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weeber F., Ooft S.N., Dijkstra K.K., Voest E.E. Tumor organoids as a pre-clinical cancer model for drug discovery. Cell Chem. Biol. 2017;24:1092–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu Z., Zhang Z., Lei Z., Lei P. CD14: biology and role in the pathogenesis of disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2019;48:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yan H.H.N., Siu H.C., Law S., Ho S.L., Yue S.S.K., Tsui W.Y., Chan D., Chan A.S., Ma S., Lam K.O., Bartfeld S., Man A.H.Y., Lee B.C.H., Chan A.S.Y., Wong J.W.H., Cheng P.S.W., Chan A.K.W., Zhang J., Shi J., Fan X., Kwong D.L.W., Mak T.W., Yuen S.T., Clevers H., Leung S.Y. A comprehensive human gastric cancer organoid biobank captures tumor subtype heterogeneity and enables therapeutic screening. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:882–897.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang L., Pang Y., Moses H.L. TGF-beta and immune cells: an important regulatory axis in the tumor microenvironment and progression. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoon C., Till J., Cho S.-J., Chang K.K., Lin J.-X., Huang C.-M., Ryeom S., Yoon S.S. KRAS activation in gastric adenocarcinoma stimulates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition to cancer stem-like cells and promotes metastasis. Mol. Cancer Res. MCR. 2019;17:1945–1957. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-19-0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 63.Yu L., Li Z., Mei H., Li W., Chen D., Liu L., Zhang Z., Sun Y., Song F., Chen W., Huang W. Patient-derived organoids of bladder cancer recapitulate antigen expression profiles and serve as a personal evaluation model for CAR-T cells in vitro. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2021;10:e1248. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yuan L., Wu X., Zhang L., Yang M., Wang X., Huang W., Pan H., Wu Y., Huang J., Liang W., Li J., Zhu X., Wang S., Guan J., Liu L. SFTPA1 is a potential prognostic biomarker correlated with immune cell infiltration and response to immunotherapy in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. CII. 2022;71:399–415. doi: 10.1007/s00262-021-02995-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Q., Liu S., Parajuli K.R., Zhang W., Zhang K., Mo Z., Liu J., Chen Z., Yang S., Wang A.R., Myers L., You Z. Interleukin-17 promotes prostate cancer via MMP7-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene. 2017;36:687–699. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang R., Liu Q., Li T., Liao Q., Zhao Y. Role of the complement system in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:300. doi: 10.1186/s12935-019-1027-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zheng L., Liang H., Zhang Q., Shen Z., Sun Y., Zhao X., Gong J., Hou Z., Jiang K., Wang Q., Jin Y., Yin Y. circPTEN1, a circular RNA generated from PTEN, suppresses cancer progression through inhibition of TGF-β/Smad signaling. Mol. Cancer. 2022;21:41. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01495-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.