Keywords: CGRP, GPCR, migraine, neuropeptide, trigeminal nerve

Abstract

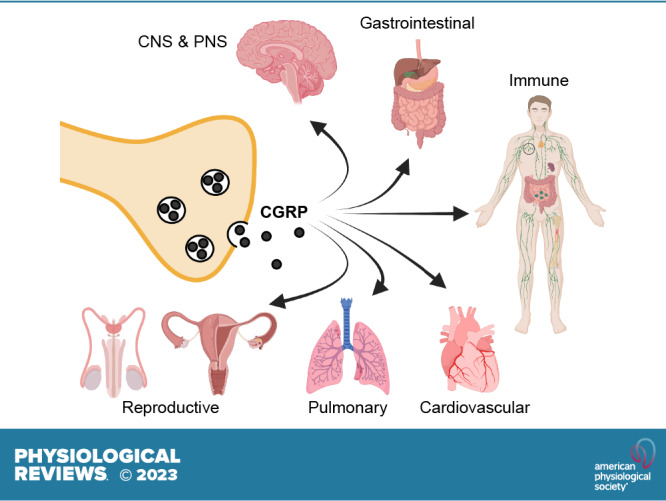

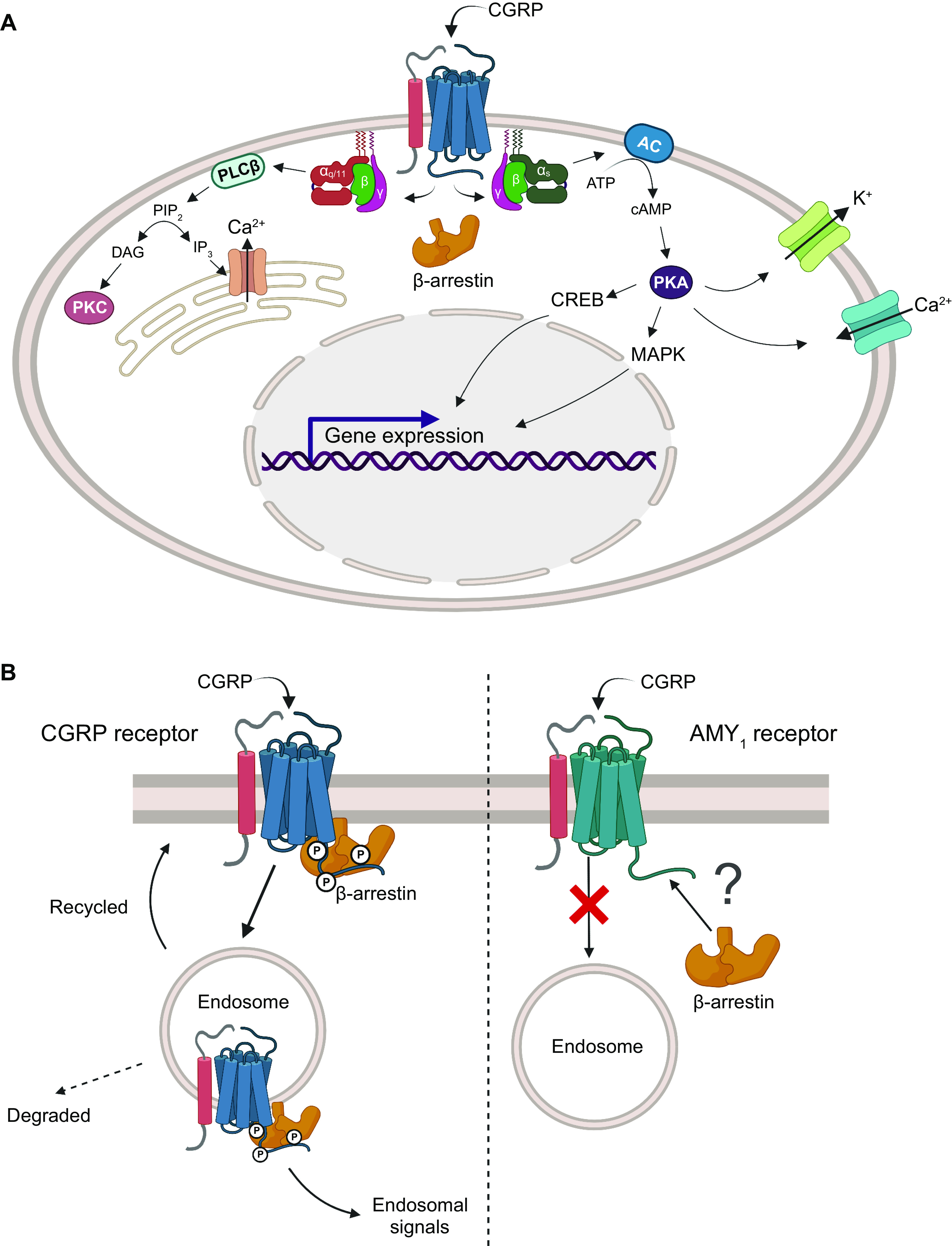

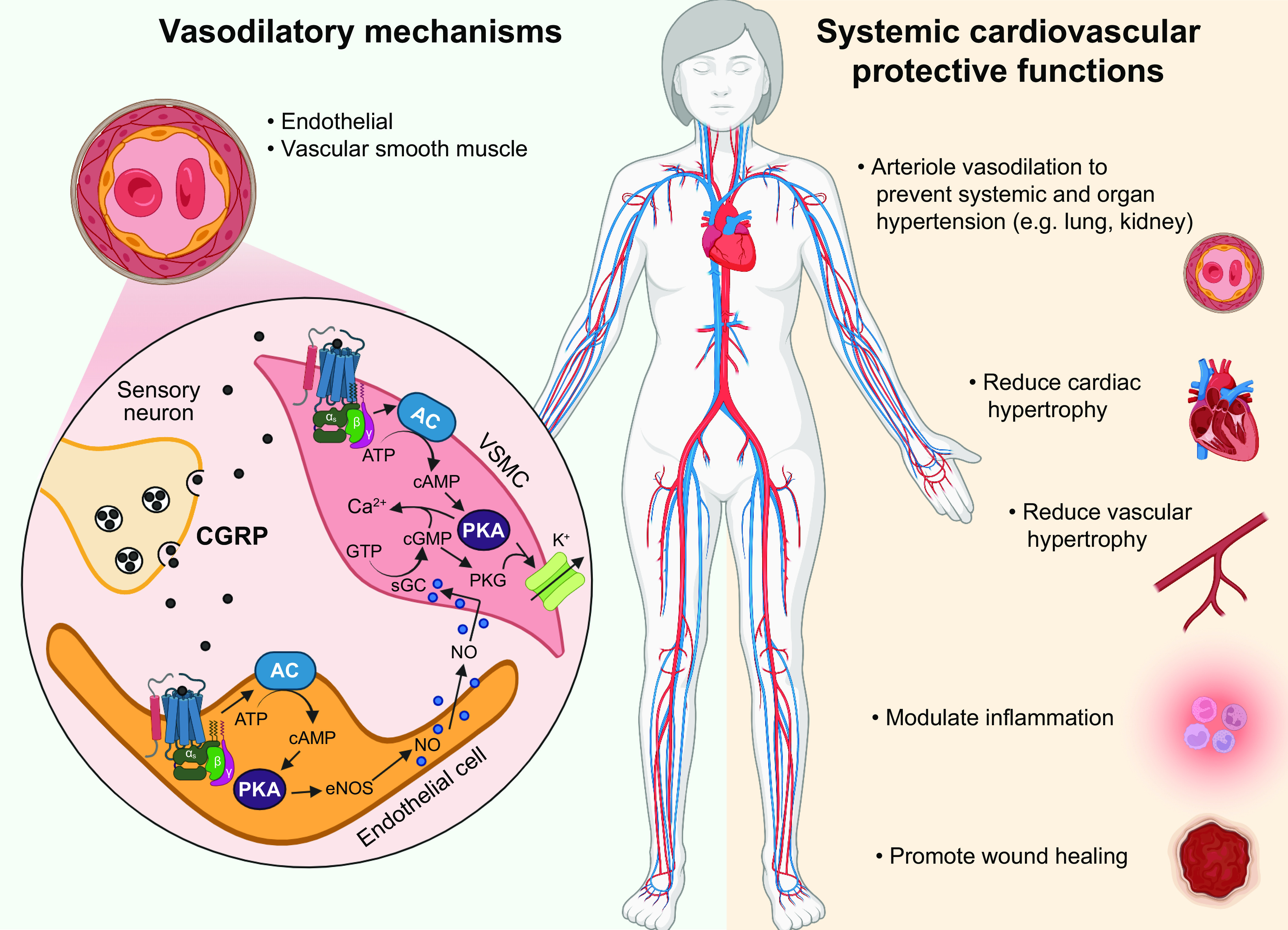

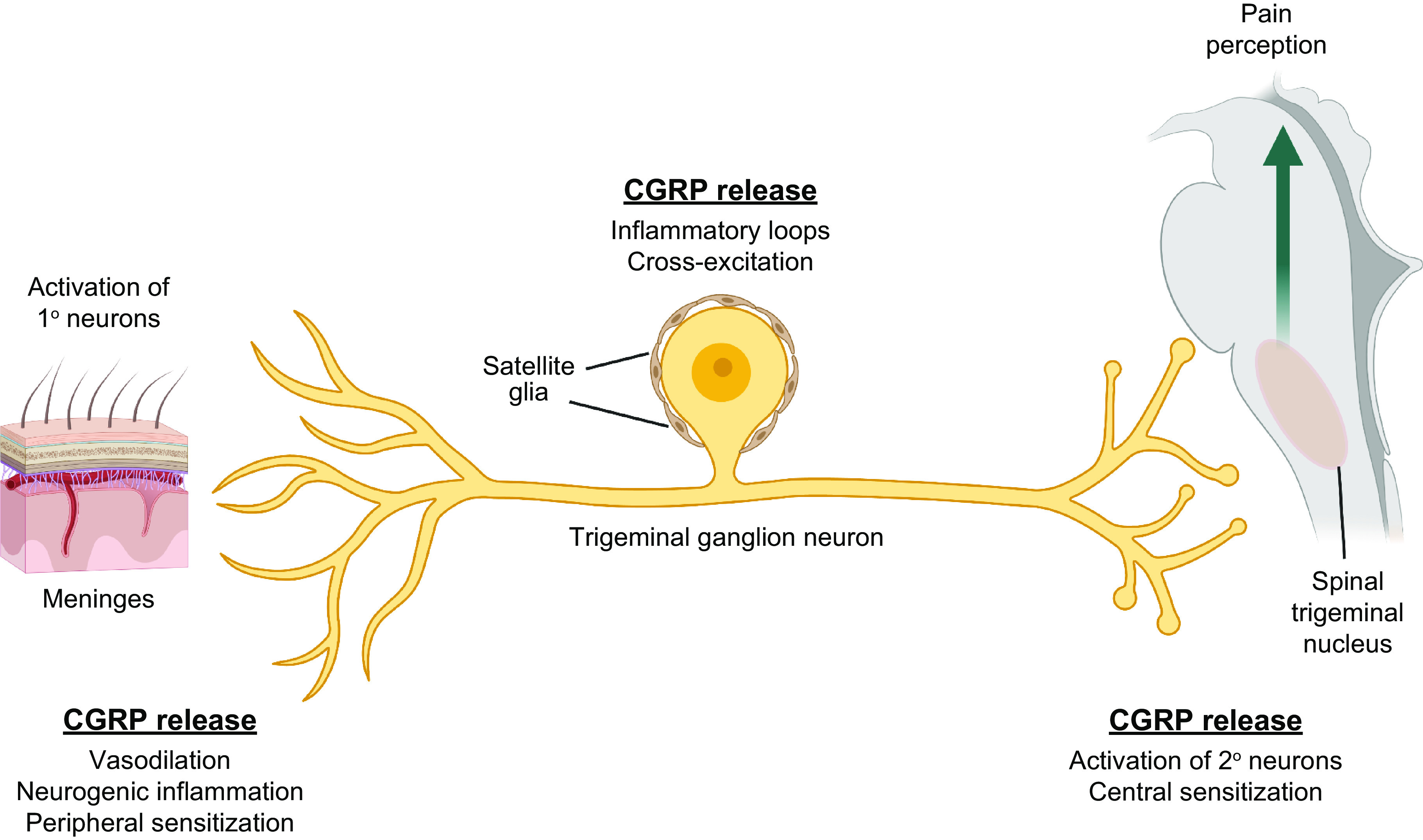

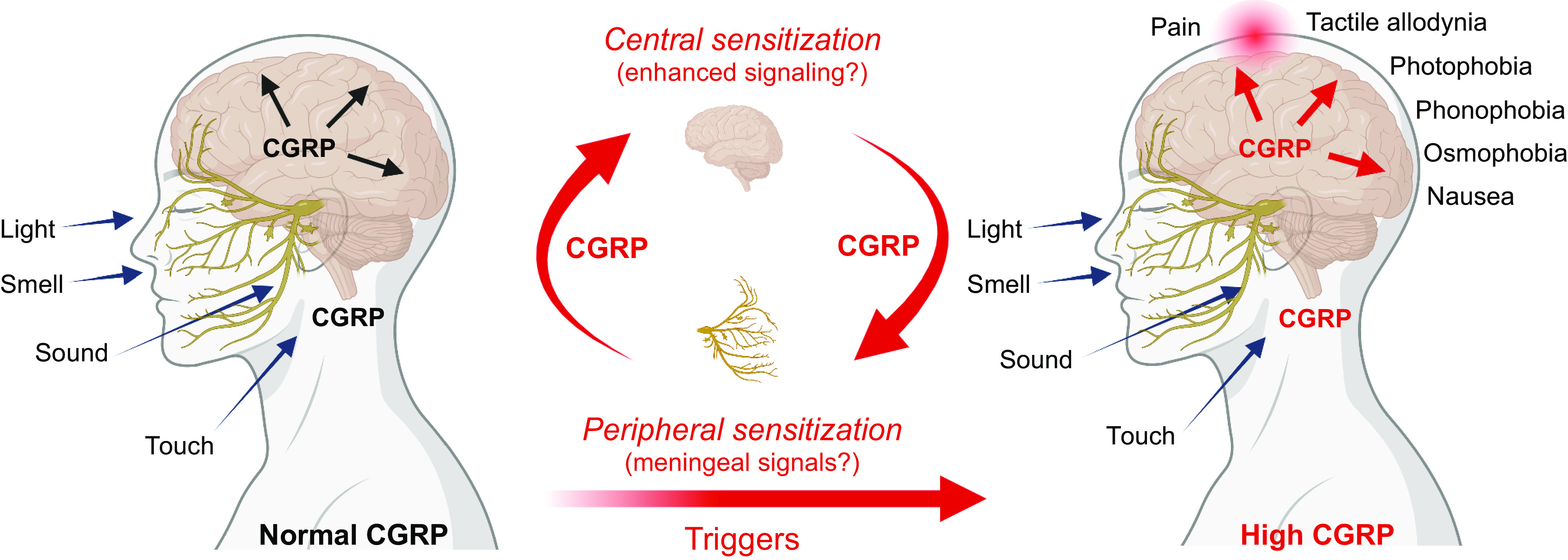

Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is a neuropeptide with diverse physiological functions. Its two isoforms (α and β) are widely expressed throughout the body in sensory neurons as well as in other cell types, such as motor neurons and neuroendocrine cells. CGRP acts via at least two G protein-coupled receptors that form unusual complexes with receptor activity-modifying proteins. These are the CGRP receptor and the AMY1 receptor; in rodents, additional receptors come into play. Although CGRP is known to produce many effects, the precise molecular identity of the receptor(s) that mediates CGRP effects is seldom clear. Despite the many enigmas still in CGRP biology, therapeutics that target the CGRP axis to treat or prevent migraine are a bench-to-bedside success story. This review provides a contextual background on the regulation and sites of CGRP expression and CGRP receptor pharmacology. The physiological actions of CGRP in the nervous system are discussed, along with updates on CGRP actions in the cardiovascular, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, immune, hematopoietic, and reproductive systems and metabolic effects of CGRP in muscle and adipose tissues. We cover how CGRP in these systems is associated with disease states, most notably migraine. In this context, we discuss how CGRP actions in both the peripheral and central nervous systems provide a basis for therapeutic targeting of CGRP in migraine. Finally, we highlight potentially fertile ground for the development of additional therapeutics and combinatorial strategies that could be designed to modulate CGRP signaling for migraine and other diseases.

CLINICAL HIGHLIGHTS.

Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is a neuropeptide with diverse physiological functions. Approved therapeutics for migraine treatment and prevention that target CGRP signaling are a recent success story. This review provides an historical perspective on CGRP, its role as a neuromodulator, its receptors and physiological functions in the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, immune, and reproductive systems, and its metabolic effects. We highlight how CGRP may cause migraine and how CGRP therapeutics may prove useful for additional diseases, including arthritis, hypertension, cardiovascular hypertrophy, rosacea, Raynaud’s phenomenon, airway diseases, gastrointestinal disorders, metabolic diseases, and possibly even COVID.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Overview

The interest in calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) has blossomed in the past few years as a result of the bench-to-bedside success story of CGRP-based therapeutics for preventing and treating migraine. This success has raised many questions, such as just how is CGRP working, can CGRP-based drugs be used for other disorders, and will those drugs be safe for long-term use? It is in the context of these migraine-driven questions that we have delved into the multifaceted functions of CGRP across multiple organ systems that include and go beyond migraine. We cover basic fundamentals, such as the mechanisms and sites of CGRP expression, with particular focus on the nervous system. To better understand how CGRP is working, we discuss the unusual features of the CGRP receptor family, including a second CGRP receptor and how these receptors provide future drug targets not just for migraine but for other disorders that may involve CGRP activities in diverse physiological systems.

1.2. History and Discovery

CGRP is now recognized as an important multifunctional neuropeptide, but its original discovery had nothing to do with function. Rather, it was discovered as one of the first examples of alternative RNA processing. In the early 1980s, a new perspective on gene regulation was revealed by the alternative splicing and polyadenylation of viral transcripts. The dogma that one gene generates one RNA was no longer true, but it remained to be seen whether alternative RNA processing was a viral oddity designed to pack more information into the relatively limited genome of a virus or if it was applicable to cellular genes as well. The first documentation that alternative RNA processing occurred with cellular transcripts came from immunoglobulin M (IgM) heavy chain that switched IgM from a membrane-bound to a secreted form. At about this time, Amara and Rosenfeld noticed that serial passage of medullary thyroid carcinoma tumors led to a decrease of calcitonin mRNA that was coupled to an increase of a different, but related, mRNA species (1). The initial name for this alternative transcript was pseudo-cal, which fortunately was soon discarded. Subsequent studies documented that alternative RNA splicing removed the exon encoding calcitonin to allow inclusion of new downstream exons encoding CGRP and noncoding sequences, along with a new polyadenylation site. In recognition of its origin from the calcitonin gene, this new transcript was named “calcitonin gene-related peptide” (2).

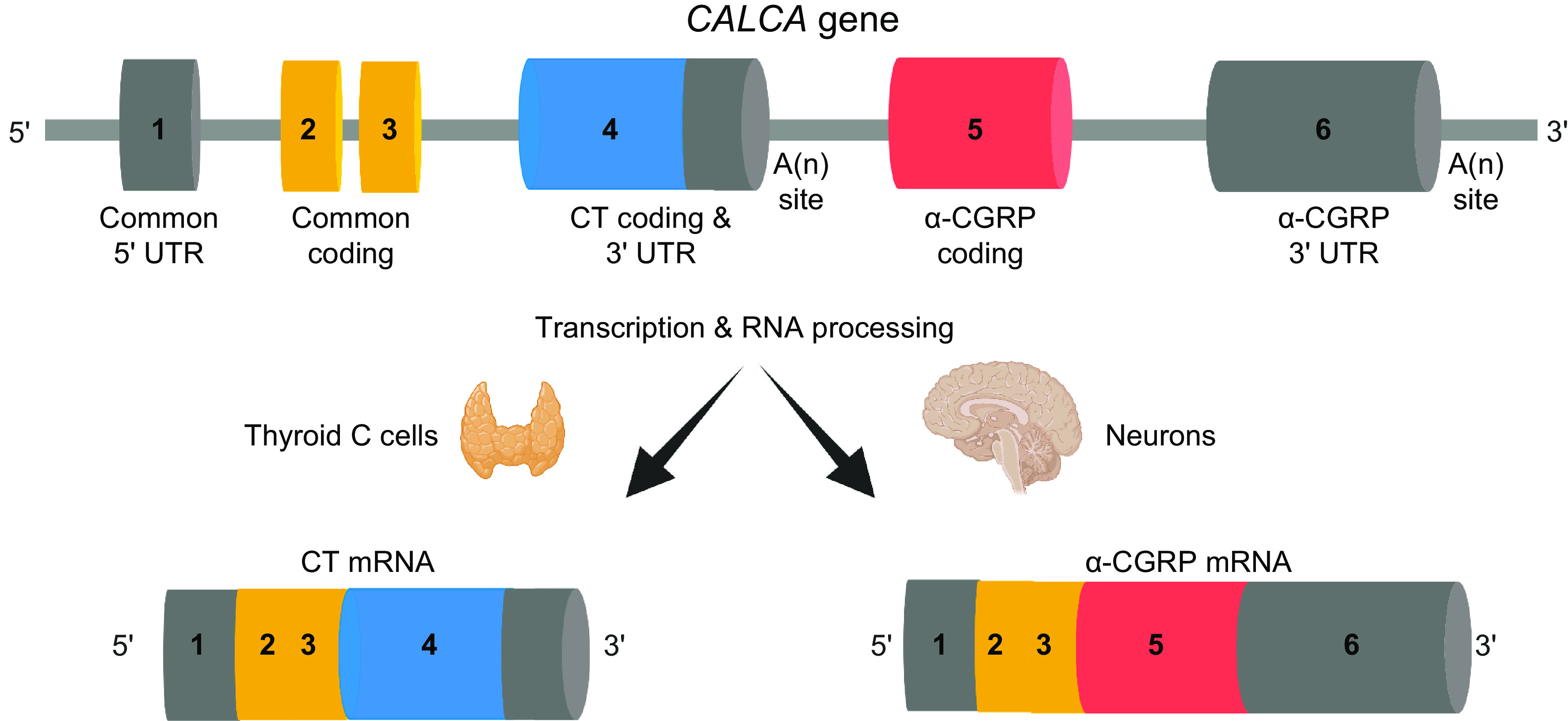

Thus, CGRP is notable as the second example of mammalian alternative RNA processing (FIGURE 1). Since those early days, alternative RNA processing is now recognized as a common theme that greatly expands the diversity of gene products from the mammalian genome. Expression of CGRP as a peptide was quickly confirmed by CGRP immunoreactivity in discrete regions of the central and peripheral nervous systems that suggested activities in cardiovascular, integrative, and gastrointestinal (GI) systems (3). Indeed, we now know that CGRP-containing nerve fibers innervate every major organ system of the body and that endogenous CGRP-expressing cells are also sometimes present in those organs.

Figure 1.

RNA processing of CALCA RNA to yield calcitonin (CT) and α-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). The CALCA gene contains 6 exons. Exon 1 is a 5′ untranslated region (UTR) common to both calcitonin and α-CGRP mRNAs. Exons 2 and 3 encode NH2-terminal sequences common to both calcitonin and α-CGRP propeptides. Exon 4 encodes calcitonin-specific sequences and 3′ UTR, followed by a cleavage and polyadenylation [A(n)] site. Exon 5 encodes α-CGRP-specific sequences that are spliced onto exon 3. Exon 6 is a 3′ UTR specific to α-CGRP mRNA and is followed by an A(n) site. Calcitonin mRNA is predominantly made in thyroid C cells, and α-CGRP mRNA is predominantly made in neurons of the central and peripheral nervous system, as well as in neuroendocrine and other cells. β-CGRP is encoded by a separate gene (CALCB), not shown. Image created with BioRender.com, with permission.

CGRP has been most studied as a neuropeptide, given its abundant expression in sensory neurons, but it is also expressed in nonneuronal cells. Nonneuronal sources of CGRP that have been reported include diffuse neuroendocrine and endocrine cells found in the thyroid (C cells) (4), lung and respiratory tract epithelia (5–7), small intestine mucosal endocrine cells (8), scattered adrenal chromaffin cells (3, 9), pancreatic islets (3), and Merkel cells in the skin (10). In addition to endocrine cells, CGRP is synthesized and secreted from other nonneuronal cells, including epithelial cells (11), adipocytes (12, 13), keratinocytes (14), endothelial cells (15, 16), white blood cells (see sect. 5.5) (17, 18), cardiac fibroblasts (19), and liver parenchymal cells (20). In some of these cell types, expression was only observed under inflammatory or other stress conditions. In general, the biological significance of nonneuronal CGRP is not clear. Likewise, although it seems unlikely that CGRP has significant endocrine activity, in part based on its fairly rapid degradation in human plasma (21), plasma CGRP levels are elevated under certain conditions, including sepsis (see sect. 5.5.1) and pregnancy (see sect. 5.8.1), possibly from perivascular spillover (22).

1.3. CGRP Family Members

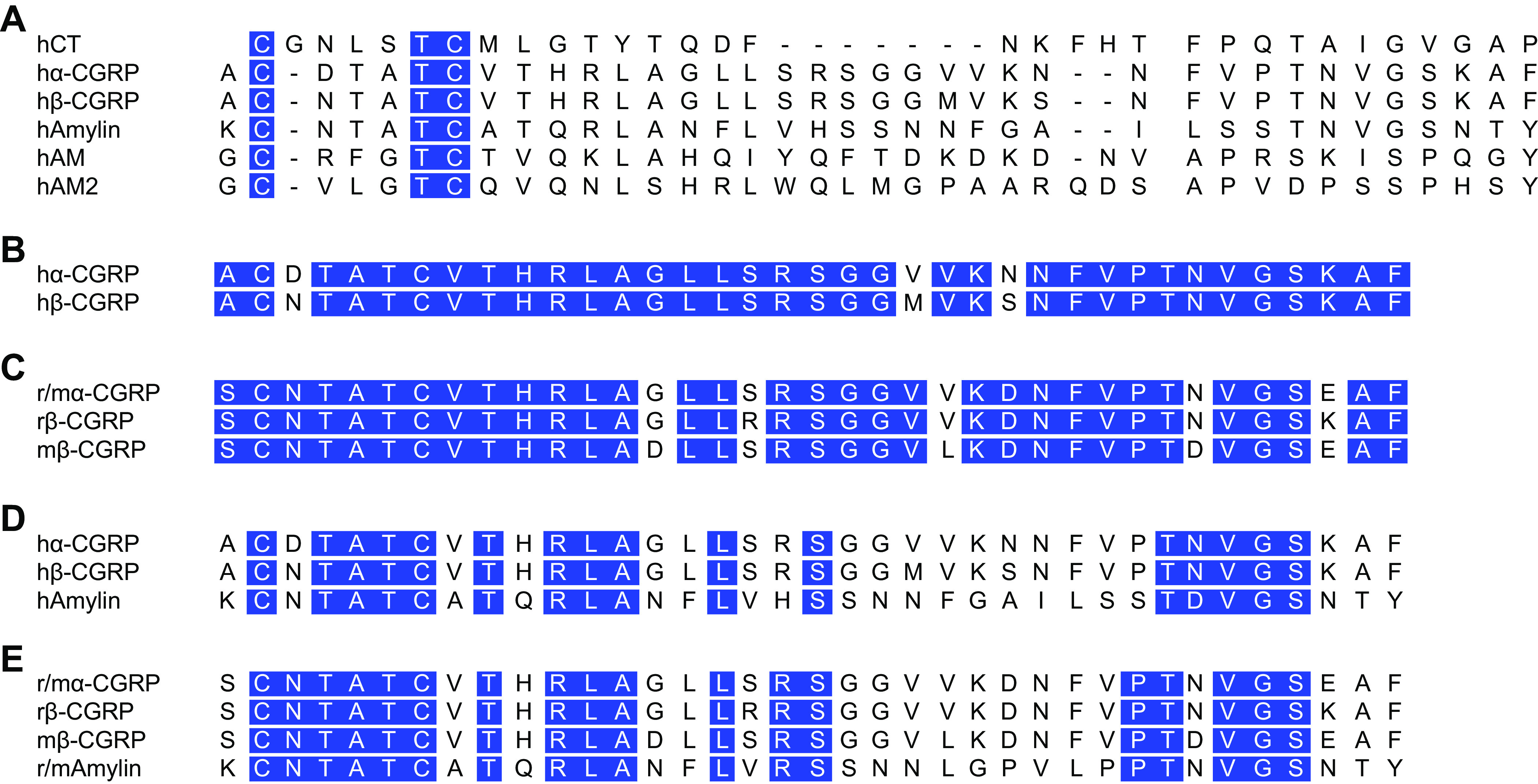

CGRP is a member of a gene family of six related peptides: calcitonin, α-CGRP, β-CGRP, amylin, adrenomedullin (AM), and adrenomedullin 2 (AM2; also known as intermedin) (FIGURE 2) (23). The mature form of CGRP is a 37-amino acid peptide with an NH2-terminal disulfide bond and an amidated COOH terminus (FIGURE 2). Both regions are required for receptor activation. This structure is conserved across all members of the CGRP gene family. In addition to the six canonical members, there are also some related peptides not found in rodents or humans and other unidentified immunoreactive peptides that might be considered distant family members (24). There is also the question of whether the precursor peptide of calcitonin, pro-calcitonin, should be considered a family member since it has been reported to act as a partial agonist at the CGRP receptor (25) and has been implicated in sepsis and other inflammatory pathologies (12, 26, 27).

Figure 2.

Amino acid sequence alignment of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and related peptides from human and rat. In A, the human (h) calcitonin (CT) peptide family are shown, omitting the NH2-terminal extensions of adrenomedullin (AM) and adrenomedullin 2 (AM2). Note that the early nomenclature referred to human α- and β-CGRP as CGRP I and CGRP II, respectively. B and C align the CGRPs to illustrate their similarities and differences. D and E compare the CGRPs to amylin. Mouse and rat α-CGRP/amylin are identical and are therefore noted as “r/m” in the figure. In all peptides, a disulfide bond is formed between the 2 NH2-terminal cysteines, and they each have a COOH-terminal amide (not shown). In all panels, identical amino acids between sets of sequences are highlighted in blue.

The CGRP family peptides share overlapping, yet distinct, biological activities and expression patterns (24, 28, 29). Although this review is focused on CGRP, a broad overview of what CGRP and its family members share is warranted. In general, the CGRP family peptides are all modulators that help maintain homeostasis. What is a modulator? A modulator is a molecule, often a peptide, that either increases or decreases a signal sent by other molecules. This is most often thought of as modulation of neurotransmission, yet as seen throughout this review, for CGRP this modulation is not limited to the nervous system.

Within the CGRP family, the two most closely related peptides are α-CGRP and β-CGRP (FIGURE 2). The α- and β-isoforms are expressed from two genes. Human CALCA (rodent Calca) encodes α-CGRP, which we will often refer to simply as CGRP. Human CALCB (rodent Calcb) encodes β-CGRP and differs from α-CGRP by only a few amino acids dependent upon species. The α- and β-CGRP peptides have nearly indistinguishable activities yet are differentially regulated and expressed in an overlapping pattern (30–32). Although sometimes β-CGRP is referred to as the enteric form of CGRP, this is misleading because both α- and β-CGRP are found in the GI system and both are found in the central nervous system (CNS), as discussed in sects. 3.5 and 5.7. Indeed, given the overlap in expression and the inability of any current antisera to distinguish α- from β-CGRP, a caveat of nearly all CGRP studies is that we really do not know the relative contributions from one gene versus the other. Recent genetic studies implicating the β-CGRP gene in human diseases discussed in sect. 2.1.2 are a reminder that both α- and β-CGRP are important.

Two members of the CGRP family that are clearly distinct from CGRP in structure and receptor affinities but have overlapping activities are AM and AM2. Of note, like CGRP, both AM and AM2 are potent vasodilators and are cardioprotective (33–35). Interestingly, infusion of AM can induce migraine in susceptible patients, similar to CGRP (36). However, unlike CGRP the source of AM and AM2 is primarily nonneuronal. Within the vasculature these peptides are synthesized and released from the endothelium instead of perivascular neurons. Beyond the vasculature, AM and AM2 are expressed in the heart and other tissues that overlap but are distinct from CGRP (37, 38). As discussed in sect. 4, both AM and AM2 signal through the calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CLR)/receptor activity-modifying protein (RAMP) 2 and CLR/RAMP3 receptors, which are similar but distinct from the canonical CGRP receptor composed of CLR/RAMP1. Signaling from CLR/RAMP2 is required for angiogenesis during embryogenesis (39–41). Both AM and AM2 have been suggested as therapeutic targets for diseases such as myocardial infarction and cancer, but to date there are not yet any approved AM-based drugs (35, 42, 43).

The family member that is most similar to CGRP is amylin (FIGURE 2). Human and rodent amylin share very high sequence identity to CGRP. Most notably, the two peptides also share a common receptor, AMY1 (23). Amylin is noteworthy as a glucose-lowering hormone produced by the pancreas (44). A synthetic form of human amylin, pramlintide, was approved in 2005 for treating diabetes (45). Interestingly, headache has been reported as an adverse event in healthy subjects infused with pramlintide (46). As described in sect. 6.6, a recent study reported that infusion of pramlintide causes migraine in migraine patients that is similar to infusion of CGRP (47). Similarly, both CGRP and amylin can cause migraine-like symptoms in mice (47, 48), which provides proof of principle that these two peptides also have overlapping functional roles.

1.4. General Features of CGRP as a Neuropeptide

An inherent feature of CGRP is that it is a neuropeptide. However, the line between a neuropeptide and a neuroendocrine peptide is blurry. Most neuropeptides, including CGRP, are also released from endocrine cells and can act on both neural and nonneural targets. As our definition of endocrine cells and tissues expands, the definition of “neuroendocrine” is becoming even broader. Although strictly speaking CGRP is perhaps better classified as a neuroendocrine peptide, we will refer to it simply as a neuropeptide, since to date that best describes its functions.

Humans have >100 known neuropeptides, many of which fall into the same classification quandary with CGRP, that can be grouped in about two dozen families (49). The pleiotropic potential of neuropeptides was best stated by an early pioneer in the field, Candace Pert: “As our feelings change, this mixture of peptides travels throughout your body and your brain. And they’re literally changing the chemistry of every cell in your body” (50). With this perspective, there are two basic features of neuropeptide expression and pharmacology relevant to CGRP: posttranslational processing and activation of receptors by volume transmission over a relatively large distance.

1.4.1. Posttranslational processing.

CGRP and neuropeptides in general are processed from precursor proteins and released from vesicles. The CGRP precursor protein is proteolytically cleaved and modified by addition of a COOH-terminal amide group that is required for CGRP binding to its receptors and for biological activity (51–54). Hence detection of CGRP RNA or peptide immunoreactivity does not necessarily mean fully modified and functional CGRP. Fortunately, the enzyme required for peptide amidation (PAM) is present in many cell types. For example, 3T3 fibroblasts have low but detectable PAM that is sufficient to modify peptides even from the constitutive secretory pathway (55).

Proteolytic processing of CGRP occurs at dibasic residues that are generally recognized by several proteases, such as furin (56, 57). A feature of the processing pathway that was recognized early on was that it can generate not just one but a portfolio of peptides from a precursor peptide. In this way, along with alternative RNA processing, multiple neuropeptides can be generated from the Calca gene (56), including propeptides containing calcitonin or CGRP sequences and NH2-terminal and COOH-terminal peptides that lack calcitonin or CGRP sequences (25, 58). Processing of CGRP occurs as a progressive mechanism from the endoplasmic reticulum into dense core secretory vesicles (FIGURE 3). The secretory vesicles are transported down the axon, which can take hours or even a day for longer axons. Once released, CGRP and other peptides are only slowly removed from the extracellular space because of the lack of reuptake machinery, such as the pumps that rapidly remove neurotransmitters from the synaptic cleft.

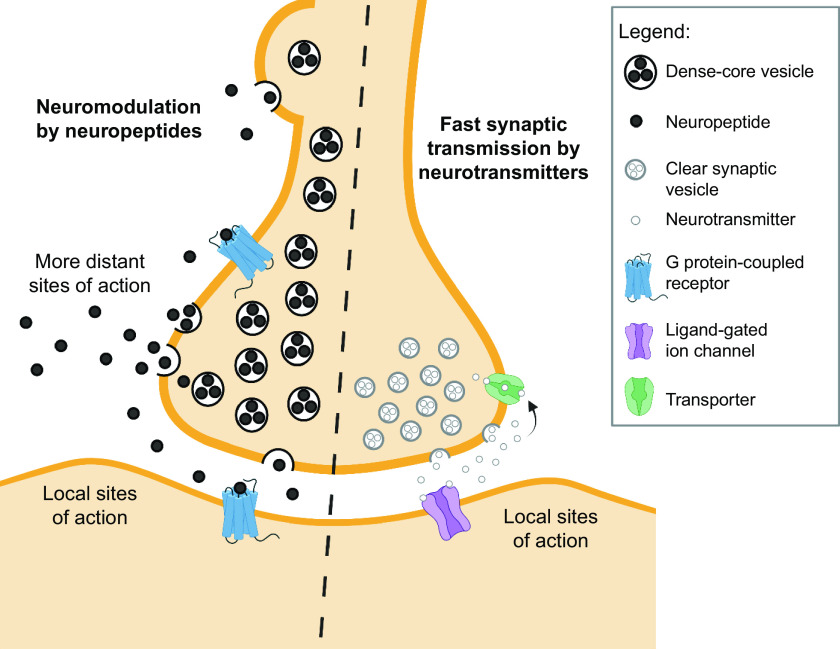

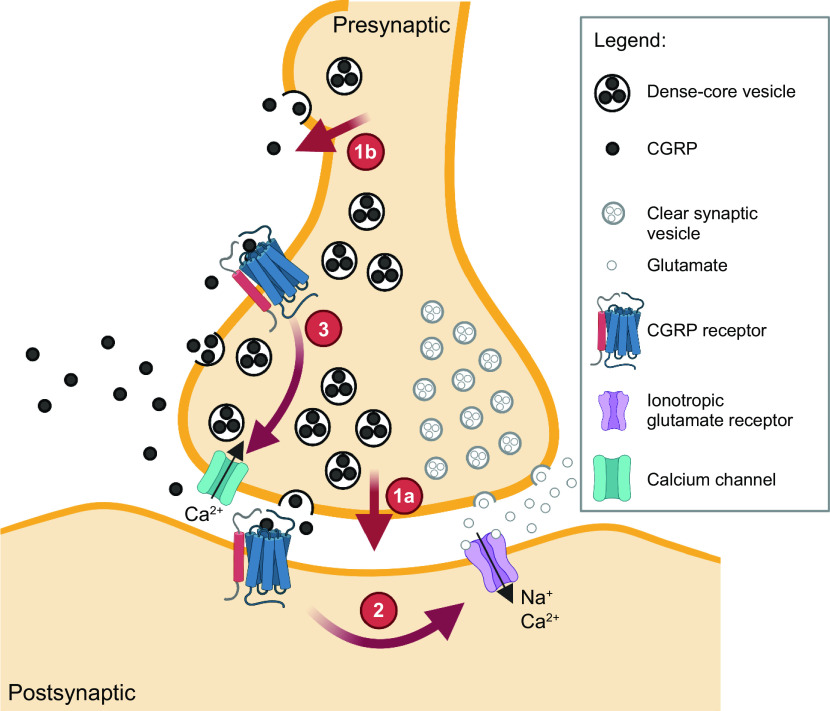

Figure 3.

Neuropeptides versus neurotransmitters. Neuromodulation by volume transmission of neuropeptides compared with fast synaptic transmission by classical neurotransmitters. Release of neuropeptides from cell bodies, axonal varicosities, and synapses allows a broad diffusion or volume transmission of neuropeptides (released from dense core vesicles) to more distant sites of action than the more locally restricted classical neurotransmitters (released from clear synaptic vesicles). Image created with BioRender.com, with permission.

1.4.2. Activation of receptors by volume transmission.

A distinguishing feature of CGRP and all neuropeptides is volume transmission. Volume transmission is diffusion-driven distribution into extracellular fluid and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) over a relatively large distance (59) (FIGURE 3). This feature of neuropeptides is driven by the fact that they can be released from dense core vesicles both at synapses in conjunction with release of neurotransmitters in small clear synaptic vesicles (60), as well as from nonsynaptic sites at the cell body and varicosities in axons (57, 61, 62). The capability for nonsynaptic release allows CGRP action over a larger area than classical neurotransmitters released only at the synaptic cleft (59). However, diffusion can be limited by physical barriers, such as within the meninges as shown by the relatively poor diffusion of CGRP between the dura mater and pia mater (63). The ongoing development of new technologies to measure diffusion within extracellular fluids (64) will advance our understanding of volume transmission of CGRP and other peptides in the brain.

A second feature of volume transmission of CGRP that is not unique to neuropeptides, but still important, is the large number of peptides per dense core vesicle. As a result, each vesicle releases a large bolus of CGRP. There have been surprisingly few measurements of the number of peptides within that bolus. One of us recently attempted to calculate this number (49). Using the available data (56, 65), we calculated ∼1.2 × 104 peptides per dense core vesicle, which agrees with an estimated ∼104 molecules of vasopressin per dense core vesicle in hypothalamic neurons (66). The number of vesicles released per cell and per stimulus will of course vary, but a rate of ∼103 vesicles/s was estimated from capacitance measurements of isolated hypothalamic neurons (67), which have an estimated 106 dense core vesicles and release ∼107 molecules/s (66). A conservative estimate is that many hundreds of vesicles will be released from a neuron over a timescale of seconds. Thus, millions of neuropeptides are likely released in a burst from a single neuron. The relevance of this fact is that it is likely that drugs used to sequester a peptide, such as the CGRP-binding monoclonal antibodies used as migraine therapeutics, are unlikely to be able to bind all the peptides released in this large bolus. Rather, the consequence is likely to be not a complete block of transmission but rather a reduced volume of CGRP transmission so that the released CGRP will have a reduced impact on its targets.

Finally, CGRP and nearly all neuropeptides act at G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (FIGURE 3). This is an important distinction from ion channel-coupled receptors, since GPCR signaling is consistent with a slower modulatory response compared to ion channel signaling. The CGRP receptors have relatively high ligand affinities (nanomolar Kds) compared with classical neurotransmitter receptors. This allows small amounts of diffused CGRP over a relatively large distance to activate receptors. In summary, the combination of volume transmission with high-affinity receptors allows CGRP to potentially be active at relatively large distances at relatively low concentrations.

2. REGULATION OF CGRP LEVELS

2.1. Transcriptional Regulation

Given the importance of CGRP in migraine and possibly other pathologies, a key question is how are CGRP levels normally controlled? The genes encoding α-CGRP and β-CGRP are in tandem (in opposite directions) on human chromosome 11 but are differentially regulated. α-CGRP and β-CGRP are encoded by human CALCA and CALCB, respectively. Human and rodent α-CGRP genes have been much more extensively studied than β-CGRP, but recent studies described below remind us that β-CGRP is important, too.

2.1.1. Transcriptional regulatory elements and factors.

The CALCA and Calca promoters are regulated by two distinct elements: a proximal cyclic AMP response element (CRE) and a distal cell-specific enhancer. In contrast to CALCA/Calca, the regulatory elements of CALCB and Calcb have not been identified, although we do know that the genes are differentially expressed in the nervous system (30, 68) and differentially regulated by extracellular signals (32).

Cell-specific expression of CALCA/Calca has been studied with reporter genes in cell cultures and transgenic mice. A 1.7-kb 5′ flanking region of rat Calca was sufficient to direct expression primarily to thyroid C cells and to a lesser degree to dorsal root ganglia (DRG), spinal cord ventral horn, and the brain of transgenic mice (69). Later studies using cultured neurons indicated that a 1.25-kb 5′ flanking region was sufficient to drive a reporter gene in CGRP-positive neurons (70). Both fragments contain the proximal and distal elements. The proximal element (−255 to −72 bp in CALCA) is an inducible enhancer activated by cAMP, Ras, and nerve growth factor (NGF) signaling pathways but does not contribute to cell specificity (71–74) (FIGURE 4). The distal element is responsible for cell-specific CGRP gene expression (75, 76), and was narrowed down to an 18-bp element (at about −1 kb) containing overlapping helix-loop-helix (HLH) and octamer motifs (77) (FIGURE 4). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays revealed complexes bound to each motif, including the homeodomain protein Oct 1 at the octamer motif that was initially termed octamer-binding protein 1 (OB1, as a nod to Obi-Wan of Star Wars fame) and a cell-specific complex termed OB2 (77). The 18-bp element was capable of driving reporter gene expression specifically in neurons (78), and disruption of the HLH motif reduced the 1.25-kb promoter activity (79). These results indicate that the 18-bp element of the distal element has strong cell-specific enhancer activity. In addition, the 18-bp element can be stimulated by mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, including those activated by proinflammatory cytokines (80) (FIGURE 4). CGRP can directly activate these pathways to boost its own expression and potentially increase CGRP actions in a positive feedback loop (81) (FIGURE 4). These pathways may contribute to the elevated CGRP levels in diseases involving inflammatory signals, such as sepsis and possibly migraine.

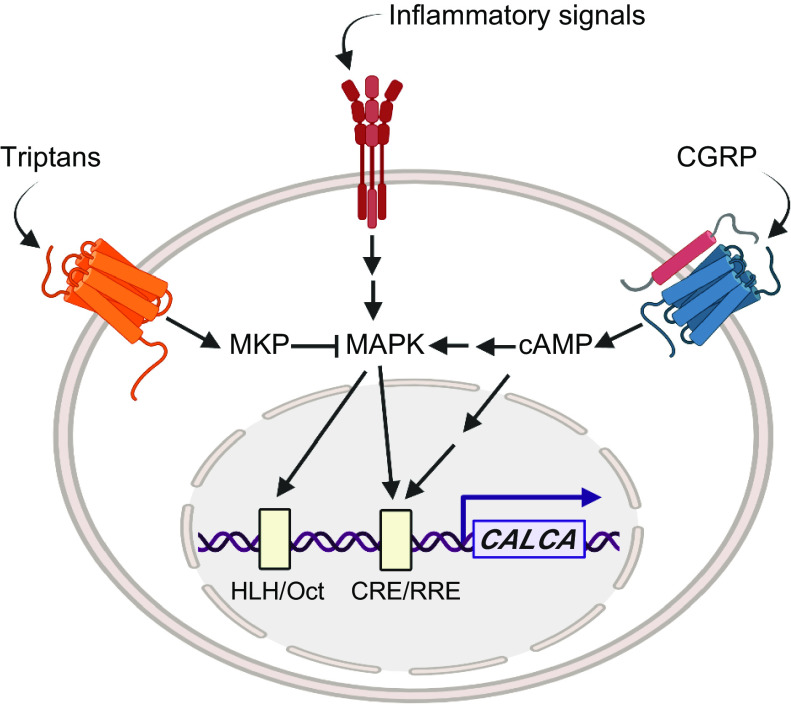

Figure 4.

Regulation of CALCA gene expression. CALCA transcription is stimulated by cAMP and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways that are activated and repressed by extracellular signals. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and other ligands that act via GPCRs coupled to Gαs increase cAMP, which activates a kinase cascade leading to activation of factors at the CRE/RRE enhancer. The cAMP cascade can also activate MAPK signaling pathways that lead to activation of factors at the helix-loop-helix (HLH)/Oct enhancer. Inflammatory signals, such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and other cytokines, activate MAPK signaling pathways leading to activation of factors at the HLH/Oct and CRE/RRE enhancers. Triptans, which act via inhibitory GPCRs, can activate MKP-1, which inhibits MAPK and hence reduces enhancer activity. Glucocorticoids, retinoic acid, and vitamin D3 also repress the gene by less defined mechanisms that inhibit the enhancers (not shown). The CGRP receptor shown represents a generic CGRP-responsive receptor, not specifically the canonical receptor or AMY1. Image created with BioRender.com, with permission.

Transcription factors that bind the 18-bp enhancer are a heterodimer of upstream stimulatory factor (USF1 and USF2) bound to the HLH motif (79) and forkhead protein FoxA2 bound to the octamer motif (OB2 complex) (82). Mutation studies confirmed the importance of these factors and showed that Oct 1 (OB1 complex) was not required. Importantly, these two DNA motifs were required to be adjacent for full enhancer activity (77), which suggests that USF and FoxA2 act synergistically for transcriptional activation. Besides their DNA binding ability, physiological roles of these transcription factors were demonstrated through small interfering (si)RNA-mediated knockdown of USF and FoxA2 (78, 82). However, a puzzle was that because the 18-bp enhancer is a cell-specific enhancer, transcription factors bound to this enhancer were expected to be neural and endocrine specific. Yet FoxA2, although present in the CGRP-positive cell lines, is predominantly expressed in the liver and is not detected in adult brain (83) or trigeminal ganglia (TG) neurons (K. Y. Park and A. F. Russo, unpublished data). Whether another FoxA2-like protein acts at the enhancer in neural cells remains to be seen. The other transcription factor, USF, is expressed in the adult brain (84) and TG neurons (78) but is not neural or endocrine specific. However, it should be noted that USF levels were higher in TG neurons than glia (78). The possibility that USF may be rate limiting for CGRP gene expression is supported by the relatively weak binding of USF to its nonconsensus site within the 18-bp enhancer and the ability of MAPK to further activate USF (79) (FIGURE 4). Thus, relatively high levels of USF in neurons along with MAPK stimulation may be necessary to activate a less-than-optimal USF-binding site, which could then contribute to CGRP neural specificity (78).

Although much is known about the cell-specific elements and factors, the story is not complete. The relative expression of the reporter gene in the transgenic mouse line described above was not determined (69). Another study did find that the 2-kb CALCA promoter was able to drive expression of a luciferase reporter gene predominantly in the brain, spinal cord, and neurons of sensory ganglia (A. Kuburas and A. F. Russo, unpublished observations). However, in the brain, expression was broadly distributed in a pattern that did not match the relative levels of endogenous CGRP RNA. This suggests that additional elements, such as a repressor element that restricts panneuronal expression, may lie outside the 2-kb promoter. This is consistent with a report that mice with Cre recombinase inserted into the Calca locus have widespread expression of a Cre-dependent reporter gene in the brain, most likely due to Calca expression during embryogenesis (85). Thus, the final story of neural-specific CGRP gene expression remains to be finished but is likely to involve epigenetic mechanisms, possibly from evolutionarily conserved elements 10 to 35 kb flanking the CALCA locus (A. F. Russo, unpublished data).

2.1.2. Epigenetic regulation of CALCA and CALCB.

The involvement of epigenetic mechanisms to restrict CALCA gene expression was suggested 30 years ago by findings that CALCA was silenced by DNA methylation in some tumors but not those that express CGRP (86, 87). These early studies reported multiple CpG islands from about −1.8 kb into exon 1 and possibly intron 2 of the human CALCA gene (86, 88). However, correlation of the methylation status with CALCA gene expression was not clear; some negative tissues and cell lines express low levels of CALCA, and the analysis was limited by the technology of the era, which only recognized a subset of CpG sites. Thus, although there was a general correlation between methylation and a more closed chromatin structure (89), the key methylation sites were not known. Subsequently, epigenetic induction of Calca was investigated in TG satellite glia (90). This study identified a hypermethylated CpG island flanking the 18-bp enhancer that was surrounded by hypoacetylated chromatin in glia and nonexpressing cell lines. Treatment with a DNA methylation inhibitor induced calcitonin mRNA in glial cultures, and with a histone deacetylase inhibitor there was a synergistic ∼80-fold increase in calcitonin and ∼3-fold increase in CGRP mRNA. Thus, epigenetic mechanisms can keep the Calca gene silent in satellite glia.

Recently, epigenetic regulation of CALCB has been examined. Sustained stimulation by the inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), which stimulates Calca expression (80), led to demethylation of CALCB so that the gene was sensitized to low doses of TNF-α (91). This mechanism involved a nearby primate-specific retroviral element, which highlights that mice will not always reveal human mechanisms. Although this study was done only in HEK293F cells, it does portend a potential for epigenetic modulation of CALCB, in addition to CALCA. Furthermore, it is a good reminder that although the TG is 90% α-CGRP, β-CGRP still represents 10% of the signal (30). It is also a reminder that the two genes can be differentially regulated (32).

2.1.3. Regulation of CALCA by multiple signaling pathways.

Several stimuli that upregulate CALCA expression go through MAPK pathways (FIGURE 4). As noted above, in contrast to CALCA, very little is known about CALCB regulation. However, the recent report that CALCB is stimulated by inflammatory signals (91) (see sect. 2.1.2), suggests that CALCB may also be upregulated by MAPK pathways. NGF treatment increased CGRP mRNA levels (92) via MAPK pathways (93, 94). Cytokines such as TNF-α and interleukin (IL)-1β also activated MAPK pathways to increase CGRP levels in neurons (80, 95). Finally, nitric oxide (NO) increased CGRP promoter activity, possibly through MAPK (96). Interestingly, repeated treatments with a NO donor (nitroglycerin) also increased trigeminal CGRP levels in vivo, which was prevented by a delta opioid receptor agonist (97). The DNA element responsible for MAPK stimulation of CALCA was pinpointed to the 18-bp cell-specific enhancer since mutation of the USF binding site prevented MAPK stimulation (94) and siRNA knockdown of USF compromised MAPK stimulation (78). In other systems, USF was shown to be phosphorylated by p38 MAPK (98). In summary, MAPK pathways are a critical signal transduction pathway that increases CGRP gene expression.

Even before MAPK, one of the earliest identified regulators of CALCA was cAMP and protein kinase A (PKA) (99) (FIGURE 4). An inhibitor of PKA decreased NGF- and cAMP-stimulated CGRP promoter activity (100) and CGRP-activated promoter activity (81). Protein kinase C (PKC) was also shown to be involved in CGRP gene expression (99, 101, 102). Combination of a PKC activator (phorbol ester) and cAMP increased calcitonin and CGRP mRNA levels in an additive way, implying that PKC and PKA signaling pathways worked independently (99). On the other hand, inhibition of MAPK-stimulated CGRP promoter by a dominant-negative form of CREB (100) suggests that there is a possible cross talk between PKA and at least MAPK pathways.

The question remains as to whether CGRP autoregulates its own levels. CGRP treatment of DRG neurons, as well as cultured myotubes, activated the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway, a known pathway to increase CGRP gene expression (103–105) (FIGURE 4). Similar signaling mechanisms have been demonstrated in the trigeminal system (81, 106). Importantly, CGRP treatment increased CGRP mRNA levels and promoter activity in cultured TG neurons (81). This autostimulation was inhibited by CGRP receptor antagonists, which verifies activation via a CGRP receptor. Although very few neurons in the TG coexpress CGRP and the canonical CGRP receptor (107–109), the finding that the AMY1 CGRP receptor is in small-diameter TG neurons known to express CGRP (110) is suggestive that autoregulation may occur in the TG. This possibility is strongly supported by the recent finding that small-diameter TG neurons coexpress both CGRP and the calcitonin receptor (CTR) subunit of the AMY1 receptor (111). In addition to TG neurons, colocalization of CGRP and CGRP receptor subunits has been reported in Purkinje neurons of the cerebellum (112).

A variable for autoregulation that is often overlooked is nervous system plasticity, which can alter the receptor and peptide expression landscape. CGRP receptor subunits are dynamically regulated by stress (113), and a marked increase in the number of TG neurons activated by CGRP was recently observed after repeated nitroglycerin treatments (a migraine trigger) (114). Hence, dynamic and/or multiple receptor expressions support the possibility of an autocrine positive feedback that would sustain CGRP synthesis in the ganglia and elsewhere.

CGRP gene expression is known to be repressed by several steroidlike molecules and serotonin autoreceptors (FIGURE 4). The vitamin A metabolite retinoic acid decreased calcitonin and CGRP mRNA level in the CA77 thyroid C cell line (115), and the negative-response cis-element was identified to be the 18-bp cell-specific enhancer (116). Likewise, the synthetic glucocorticoid dexamethasone reduced CGRP mRNA and promoter activity in a cell-specific manner that was dependent on the 18-bp enhancer (117). Another agent that represses CGRP gene expression is the calcium homeostasis hormone vitamin D. Vitamin D decreased calcitonin mRNA level in parathyroid-thyroid glands of rats in a time- and dose-dependent manner (118). This repressive effect of vitamin D required both the proximal CRE and the distal enhancer in TT thyroid C cells (119), possibly by interrupting interactions between CREB and the enhancer binding proteins (120). Taken together, it is likely that retinoic acid, glucocorticoids, and vitamin D repress the CGRP gene by interfering with USF and FoxA2 at the 18-bp enhancer.

Serotonin receptor (5-HT1B/D/F) agonists that include triptan drugs used for migraine treatment also repress the CGRP gene (121) (FIGURE 4). The well-known migraine drug sumatriptan is an agonist of these receptors and decreases plasma CGRP (122). The 5-HT1 agonists decreased phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) and JNK MAP kinases and decreased CGRP mRNA in the CA77 thyroid C cell line (94, 123). Unexpectedly, sumatriptan inhibited MAPK signaling pathways via an abnormally prolonged low-level elevation of intracellular Ca2+ (124), which in turn elevated a dual-specificity phosphatase (MAPK phosphatase-1) (94). It is possible that use of triptans to inhibit dual-specificity phosphatases may be useful for treating other diseases, such as obesity and diabetes (125–128). However, the time course of sumatriptan action in migraine patients precludes transcriptional regulation as the drug mechanism for abortive treatment of migraine. Instead, it is more likely that the mechanism is via inhibiting CGRP release (129–132). The first clear evidence for triptan inhibition of CGRP release was shown in patients by Goadsby and Edvinsson (133), who showed that CGRP levels in the external jugular outflow of migraine patients were reduced concomitant with headache relief following sumatriptan administration (see sect. 6.2.1). Although speculative, it is possible that the actions of sumatriptan on CGRP gene transcription may have more long-term effects on patients, such as contributing to chronic headaches associated with medication overuse (70, 134). In this scenario, repeated triptan usage might reduce CGRP levels, which then leads to a rebound of elevated CGRP and migraine upon triptan withdrawal.

2.2. Posttranscriptional Regulation

An understanding of CGRP alternative splicing was long an elusive holy grail that appears to have been finally resolved. The splice choice is largely determined by a family of RNA-binding proteins enriched in several tissues, including the brain (135, 136). Early studies on the calcitonin/CGRP splice mechanism had implicated an intronic site in the third intron (upstream of the calcitonin-specific exon 4) (137). Later studies implicated an intronic site in the fourth intron (138, 139) and a splice enhancer within exon 4 bound by a protein called SRp55 (140). Another study pointed to intronic sequences upstream of exon 5 (141). In the following years, further studies showed that, not surprisingly, it is likely a combination of these sites that contributes to alternative splicing of the calcitonin/CGRP transcript. The best evidence points to an exon exclusion mechanism mediated by Fox-1 and Fox-2 RNA binding proteins (not to be confused with transcription factor FoxA2) (135, 136). These Fox proteins can prevent inclusion of the calcitonin-specific exon 4 by binding to silencer elements in exon 4 and in the upstream intron 3. As a result, Fox proteins prevent calcitonin exon splicing by two distinct steps in the spliceosome complex (135). Along with binding of Hu proteins to the downstream intron 4 site (142), this provides a redundant and tightly regulated alternative splicing mechanism that leads to the preferential production of CGRP in neurons.

Thus, the decision of whether to include or exclude the calcitonin exon (exon 4) is regulated by a balance of positive and negative regulation mediated by many proteins but especially by the Fox-1 and Fox-2 proteins. A caveat of these studies is that to date the splice choice can be modulated in cell culture, but no evidence of that modulation by Fox proteins occurring in vivo has been fully documented. To be clear, a splice switch between calcitonin and CGRP can occur in vivo, since it was the switch upon serial passages of medullary thyroid carcinoma tumors that originally led to the discovery of CGRP. Whether such a switch in calcitonin/CGRP splicing occurs physiologically or underlies any pathologies remains to be seen.

2.3. Control of Release

CGRP release is regulated by several mechanisms. Most relevant clinically is inhibition by 5-HT1B/D/F agonists that include the triptan migraine drugs. Notably, acute sumatriptan treatment reduces plasma CGRP levels in migraine patients (133). Inhibition by triptans has been reported in several preclinical models (24), including the recently approved 5-HT1F agonist (143). Inhibition of CGRP release has also been reported in response to other agents, most notably adenosine (144) and TRPC4 agonists (145). Conversely, stimulation of release by several agents, including cytokines, NO, and purinergic receptors, has been reported (see sect. 5.2.2). CGRP release is also indirectly stimulated by microRNA miR-34a-5p via an IL-1β inflammatory pathway in rat TG neurons (146). Interestingly, this microRNA is reportedly elevated in serum during acute migraine attacks (147) and interictally in chronic migraine patients (148).

An important point to remember for CGRP release is that it can occur from both synaptic and nonsynaptic sites, which allows volume transmission as described in sect. 1.4.2 (49). In particular, the role of cell body transmission may be very relevant within the TG, as discussed in sect. 5.2. Recent studies have suggested that intraganglionic CGRP transmission plays a role in activation of the trigeminovascular pathway by acute exposure to nasal TRPA1 agonists associated with migraine (149). Interestingly, TG cell bodies are key sites of TRPA1-mediated allodynia following nitroglycerin stimulation in mice (150). Paracrine signaling of CGRP within the ganglia has also been demonstrated between satellite glia and neurons (151). As with cell bodies, CGRP release from varicosities and terminals may act in a paracrine manner on multiple targets to influence afferent signals from sensory tissues such as the eyes, ears, nose, and mouth (152).

2.4. Degradation and Clearance

Although long lived compared with neurotransmitters, neuropeptide actions are eventually terminated by extracellular proteases. The half-life of most peptides is on the order of minutes in the plasma (59). However, an untapped area of research is the more biologically relevant half-life of peptides in extracellular or cerebrospinal fluid. For example, the half-life of CGRP in the plasma is 7 min (21), whereas in the skin CGRP actions can be on the order of hours, suggesting a longer half-life (153, 154).

CGRP degradation has largely been studied by incubating synthetic CGRP from different species with purified enzymes, cocktails of enzymes, tissue lysates such as spinal cord, or fluids such as plasma and CSF (155–164). Collectively, such studies have identified many different enzymes that are capable of cleaving CGRP into smaller fragments, and a range of different cleavage sites occur within the peptide. Enzymes implicated in CGRP degradation include neutral endopeptidase, human lung mast cell tryptase, insulin-degrading enzyme, plasmin, thrombin, matrix metalloproteinase 2, trypsin, and endothelin-converting enzyme (ECE). There is a general consensus that cleavage commonly occurs between the following pairs of amino acids: Arg11-Leu12, Gly14-Leu15, Ser17-Arg18, Arg18-Ser19, Lys24-Asn25, and Asn26-Phe27. Cleavage between Cys7 and Val8 has also been reported. Over the range of individual enzymes and studies, there are also other reported cleavage sites, such as Glu35-Ala36 and Ala36-Phe37. However, which of these serve as physiological mechanisms for controlling CGRP activity is less clear, though none of the resulting peptide fragments would be expected to be biologically active, based on currently understood structure-function relationships for CGRP (see sect. 4.4). Degradation by ECE-1 has been linked to regulation of the receptor once internalized into endosomes, whereby this promotes recycling of the receptor back to the cell surface (165). Therefore, although the peptide may be degraded, this degradation can prompt resensitization of the system to CGRP, enabling the receptor to bind a new intact CGRP molecule again at the cell surface. CGRP uptake into nerve terminals could also contribute to CGRP clearance (166). In addition to degradation, CGRP clearance occurs through the kidney and to a smaller extent the liver, based on the limited data available (167, 168). The vast majority of studies have investigated α-CGRP degradation or have not specified the form used. One study that compared human α-CGRP and β-CGRP found that both were cleaved by matrix metalloproteinase 2 (169). However, the amino acid sequence differences between human α-CGRP and β-CGRP (positions 3, 22, 25) or rat α-CGRP and β-CGRP (positions 17, 35) (FIGURE 2) could potentially result in altered recognition by different proteases, thus differentially affecting degradation and therefore function of each peptide. This possibility requires experimental confirmation.

3. SITES OF CGRP EXPRESSION

3.1. Overview and Context for Interpreting Expression Studies

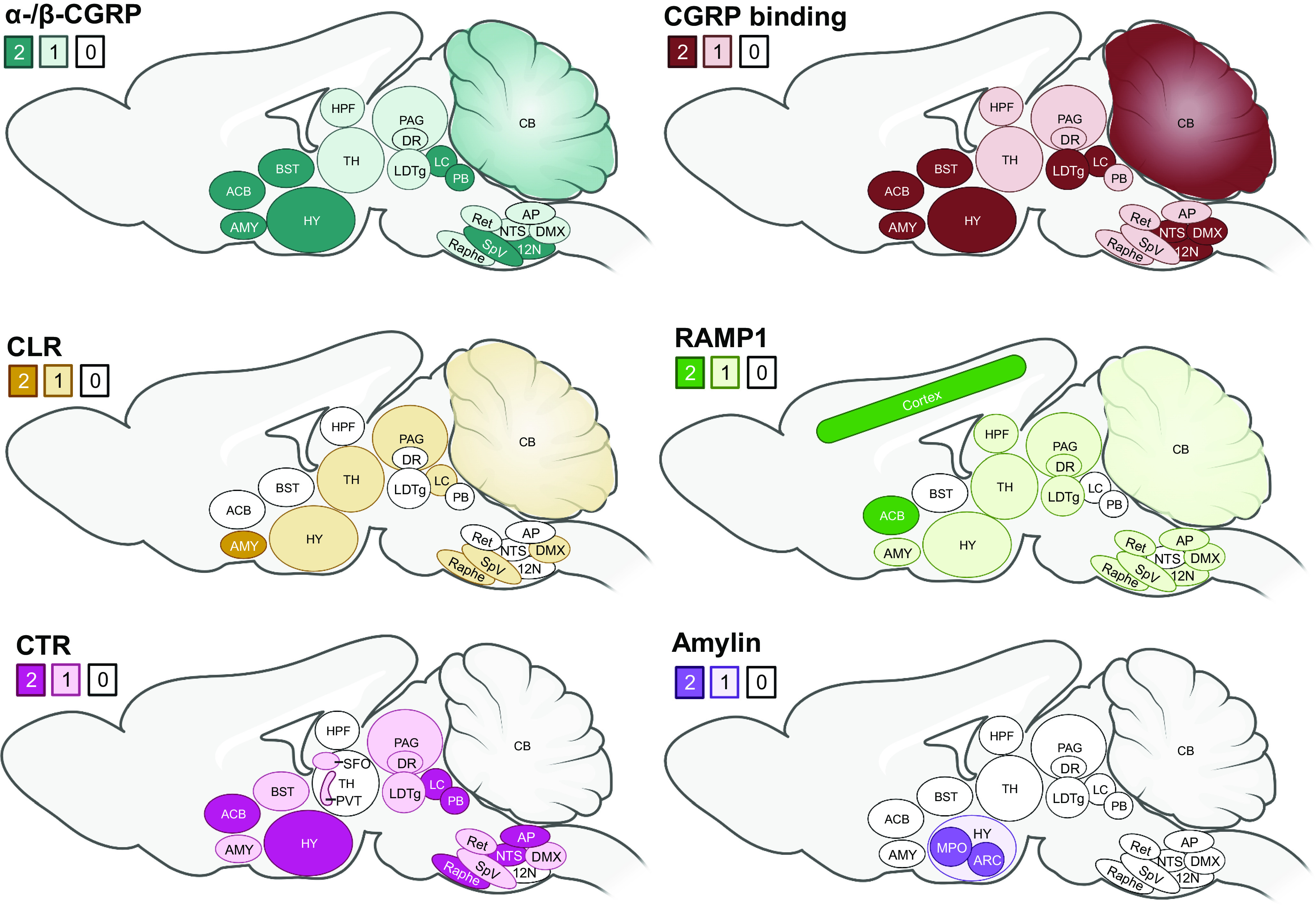

Understanding exactly where CGRP is located, and how this relates to where its receptors are found, is vital for understanding its functions. CGRP is broadly distributed throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems of vertebrates. There are regions of the brain with relatively high abundance, such as the amygdala, parabrachial nucleus (PBN), and locus coeruleus (FIGURE 5) (108, 110, 112, 170–219). Other well-known sites containing CGRP are the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, the perivascular neural network of blood vessels, and sensory nerves. However, beneath these broad statements lie several layers of complexity that create challenges for defining the precise details at a cellular level. Many of these complexities also apply to receptor expression studies that are considered in sect. 4.

Figure 5.

Sites of α-/β-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), amylin, CGRP binding (125I-CGRP), and receptor subunit expression in the brain. Calcitonin is not shown as it is not detected in the brain. CLR, calcitonin receptor-like receptor; CTR, calcitonin receptor; HY, hypothalamus; LDTg, laterodorsal tegmental nucleus; RAMP1, receptor activity-modifying protein 1; TH, thalamus; see TABLE 1 for other abbreviations. The shaded numbers reflect approximate differences in abundance or number of binding sites, with 2 reflecting the most and 0 the least. Much data are not clear-cut. For binding, this largely relates to radiolabeled forms of CGRP in autoradiography. For peptide and receptor subunits, this is a composite of mRNA and immunoreactivity across multiple studies. The data are mostly from rodent and primate from the following citations: rodent CGRP (see TABLE 1), primate CGRP (170–175), CGRP binding (170, 172, 176–182), CLR (108, 112, 170, 171, 176, 183–194), RAMP1 (108, 110, 112, 170, 171, 176, 183, 184, 186, 187, 192–200), CTR (110, 195, 197, 198, 201–211), and amylin (207, 212–219). Image created with BioRender.com, with permission.

In this review we use the term “expression” broadly to indicate both RNA and peptide. Since peptides are generally located in remote fibers as well as the cell body, and mRNA can sometimes be transported from the cell body (220), mRNA and protein expression data may not always be consistent. Adding to these challenges is that the interpretation of peptide or protein data can be influenced by several confounding factors. For example, definitively determining which isoforms of CGRP are expressed is complicated by the fact that antibodies are unlikely to distinguish between α-CGRP and β-CGRP because of their extremely high amino acid sequence identity. Therefore, it is challenging to obtain specific information about only one of these peptides, and about their relationships to one another. Another significant issue for the CGRP field is the potential for cross-reactivity between amylin and CGRP antibodies because of their high amino acid sequence identity, which is concentrated in certain regions of the peptide sequences (FIGURE 2). This becomes more important as the abundance of the peptide increases, with even low-level cross-reactivity for the nontarget peptide becoming amplified where it is expressed at high levels, as recently discussed (221, 222). Antibodies are nevertheless commonly employed in measuring peptide expression, but they can additionally bind nonspecifically to unrelated proteins. Ideally all antibodies would be carefully validated, but this is often not the case (223). In interpreting the data described below, it is important to recognize that not all of the studies used well-characterized probes, and that the evidence presented must be taken in the light of the potential limitations of the tools used. Hence, data obtained with antibodies are more accurately reported as CGRP-like immunoreactivity rather than CGRP expression. However, for simplicity we use the term “CGRP” or “CGRP immunoreactivity” rather than CGRP-like immunoreactivity in this review.

A further important consideration for all studies is that rodents are not always the same as humans. For example, recent studies have revealed that the spinal projections of peptidergic (CGRP) and nonpeptidergic (P2X3R) DRG nociceptors are different between mice and humans. In mice the two subsets of nociceptors are distinct, whereas in humans they largely overlap (224, 225). We briefly mention species considerations in sect. 3.5.

In the subsequent text, the sites of expression of CGRP in general are first covered, followed by a separate review of the sites of β-CGRP expression and of how this expression may differ from that of α-CGRP, where the information is available (see sect. 3.4). The reasons for not specifically discussing α-CGRP and β-CGRP by location and for separating β-CGRP to its own section are that 1) antibodies cannot separate these two peptides, and thus this distinction cannot be made, and 2) β-CGRP is rarely studied compared to α-CGRP, and so there are not sufficient data to provide a detailed comparison. The data for CGRP in major peripheral ganglia and CNS of rats and mice are detailed in TABLE 1. Some of these areas are then illustrated in FIGURE 5, in relation to CGRP binding sites and sites of receptor subunit expression.

Table 1.

CGRP mRNA and peptide expression in neural sites of rat and mouse

| Region | mRNA | Peptide |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoreactivity | Location | ||

| TG | Y (3, 30) | Y (3, 5, 108, 111, 177, 226–230) | CF |

| DRG | Y (231–234) | Y (227, 230, 232, 235) | CF |

| Spinal cord | |||

| Dorsal horn | Y (236) | Y (3, 230, 232, 236–238) | CF |

| Ventral horn | Y (231, 233, 236) | Y (3, 230, 232, 238) | CF |

| Sensory cranial nuclei | |||

| Mesencephalic trigeminal [V, VII, IX, X] | N (231) | Y (193, 239) | C |

| Principal trigeminal [V, VII, IX, X] | Y (229, 240) | F | |

| Vestibular [VIII] | Y (3, 230, 240, 241) | CF | |

| Cochlear [VIII] | Y (3, 229, 230, 240) | CF | |

| Spinal trigeminal [V, VII, IX, X] (SpV) | Y (3, 108, 171, 229, 238, 240, 241) | CF | |

| Nucleus of the solitary tract [VII, IX, X] (NTS) | ? (231) | Y (3, 193, 229, 230, 238, 240, 242) | CF |

| Motor cranial nuclei | |||

| Oculomotor [III] | Y (30, 231, 243, 244) | Y (230, 238, 240–242, 244) | CF |

| Accessory oculomotor (Edinger–Westphal) [III] | ? | Y (240, 242) | C |

| Trochlear [IV] | Y (30, 231, 244) | Y (230, 240, 242, 244) | C |

| Trigeminal [V] | Y (30, 231, 244) | Y (229, 230, 238, 240–242, 244) | C |

| Abducens [VI] | Y (30, 231, 244) | Y (230, 240, 242, 244) | C |

| Facial [VII] | Y (30, 231, 244) | Y (3, 193, 230, 238, 240–242, 244) | CF |

| Salivatory [VII, IX] | Y (245) | F | |

| Hypoglossal [XII] (12N) | Y (30, 231, 244) | Y (3, 193, 230, 238, 240–242, 244) | CF |

| Dorsal nucleus of the vagus [X] (DMX) | ? | Y (193, 242) | CF |

| Nucleus ambiguus [IX, X] | Y (30, 231, 244) | Y (3, 229–231, 238, 240–242, 244) | CF |

| Medulla oblongata | |||

| Gigantocellular reticular nucleus | Y (193, 240) | CF | |

| Cuneate/external cuneate nucleus | Y (244) | Y (229, 230, 240) | CF |

| Intercalated nucleus of the medulla oblongata | Y (244) | ? (244) | |

| Nucleus of Roller | Y (244) | ? (244) | |

| Reticular nucleus (Ret) | Y (244) | Y (229, 230, 240, 242) | CF |

| Raphe magnus nucleus | Y (193) | C | |

| Dorsal raphe nucleus | Y (240) | F | |

| Other raphe nuclei | ? (244) | N (240) | |

| Gracile nucleus | Y (193, 229, 230, 240) | CF | |

| Area postrema (AP) | Y (230, 240) | CF | |

| Pons | |||

| Lateral lemniscus | Y (244) | Y (230, 240, 244) | CF |

| Pontine nuclei | ? (244) | Y (193, 230, 242, 244) | C |

| Pontine reticular nucleus | Y (244) | Y (230, 244) | F |

| Ventral nucleus of the lateral lemniscus | Y (244) | Y (242, 244) | C |

| Dorsal nucleus of the lateral lemniscus | Y (244) | Y (230, 244) | F |

| Superior olive | Y (30, 231, 244) | Y (230, 238, 240, 242, 244) | CF |

| Central gray of the pons | ? (244) | Y (230) | C |

| Locus coeruleus (LC) | Y (193, 230, 241) | CF | |

| Cerebellum | Y (112, 193, 231, 238, 240, 242, 246) | CF | |

| Midbrain | |||

| Central periaqueductal gray (PAG) | ? (243, 244) | Y (229,230, 241, 244) | C |

| Ventral periaqueductal gray (PAG) | Y (243) | ||

| Parabigeminal nucleus | Y (244) | Y (240, 244) | CF |

| Cuneiform nucleus | Y (244) | Y (230, 240, 244) | CF |

| Ventral tegmental nucleus (Gudden) | ? (244) | Y (230, 244) | F |

| Dorsal tegmental nucleus/area | ? (244) | Y (230, 241, 244) | CF |

| Parabrachial nucleus/area (PB) | Y (30, 231, 244) | Y (3, 229, 230, 238, 240, 244, 247) | CF |

| Kölliker–Fuse nucleus | Y (244) | Y (229, 244) | C |

| Inferior colliculus | Y (230, 231, 238, 240) | CF | |

| Red nucleus | Y (193, 230) | CF | |

| Central nucleus of the inferior colliculus | ? (244) | Y (230) | C |

| Superior colliculus | Y (238, 240) | CF | |

| Forebrain | |||

| Organum vasculosum lamina terminalis | Y (230) | F | |

| Subfornical organ (SFO) | Y (230, 238) | F | |

| Medial preoptic nucleus/area (MPO) | Y (244) | Y (230, 238, 240, 244) | CF |

| Periventricular hypothalamic nucleus/zone | ? (244) | Y (230, 238, 244) | F |

| Lateral hypothalamic area | Y (244) | Y (3, 240, 244) | CF |

| Anterior hypothalamic area | ? (244) | Y (230, 238, 244) | C |

| Posterior hypothalamic nucleus | N (240) | ||

| Ventromedial hypothalamic area | Y (240) | F | |

| Paraventricular hypothalamic nuclei | ? (244) | Y (193, 230, 240, 244) | CF |

| Arcuate hypothalamic nucleus (ARC) | Y (244) | Y (230, 238, 240, 244) | CF |

| Mammillary body/supramammillary region | Y (230, 240) | F | |

| Zona incerta | Y (244) | Y (240, 244, 247–249) | F |

| Dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus | ? (244) | Y (230, 238, 244) | C |

| Perifornical nucleus | ? (244) | Y (230, 244) | C |

| Premammillary nucleus, ventral part | ? (244) | Y (230, 244) | CF |

| Ventromedial thalamic nucleus | ? (244) | Y (238, 240, 247, 249) | CF |

| Centromedial thalamic nucleus | Y (193, 229, 247, 249) | CF | |

| Centrolateral thalamic nucleus | Y (248) | F | |

| Mediodorsal thalamic nucleus | Y (247–249) | F | |

| Laterodorsal thalamic nucleus | Y (248) | F | |

| Paracentral thalamic nucleus | Y (244) | Y (230, 244, 248, 249) | F |

| Ventroposterior thalamic nucleus, parvicellular | ? (244) | Y (230, 244, 247–250) | CF |

| Ventroposterior medial thalamic nucleus | Y (247–249) | F | |

| Ventroposterior lateral thalamic nucleus | Y (248) | F | |

| Subparafascicular thalamic nucleus | Y (244) | Y (229, 230, 244, 247, 249) | CF |

| Lateral subparafascicular thalamic nucleus | Y (244) | Y (230, 244) | C |

| Parafascicular thalamic nucleus | Y (244) | Y (230, 244, 247, 249) | CF |

| Paraventricular thalamic nucleus (PVT) | Y (193, 238, 240, 247, 249) | CF | |

| Posterior thalamic nuclear group | Y (244) | Y (230, 244, 247–249) | F |

| Lateroposterior thalamic nucleus | Y (248) | F | |

| Posterior intralaminar thalamic nucleus | Y (244) | Y (230, 244) | C |

| Peripeduncular nucleus | Y (30, 231, 244) | Y (3, 229,230, 238, 240, 247, 249) | CF |

| Geniculate body | Y (230) | F | |

| Central gray matter | Y (230, 247, 249) | CF | |

| Hippocampal formation (HPF) | |||

| CA1–CA4 | Y (244) | Y (193, 230) | C |

| Dentate gyrus (ventral) | Y (193, 230, 240) | CF | |

| Septal area (medial, lateral) | Y (3, 193, 230, 238, 240, 242) | F | |

| Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis/nucleus accumbens (BST/ACB), stria terminalis | Y (244) | Y (3, 230, 238, 240, 242, 244) | F |

| Globus pallidus | Y (3, 238, 240) | F | |

| Caudate-putamen | Y (3, 229, 230, 238, 240) | F | |

| Medial corticohypothalamic tract | Y (244) | ? (230) | |

| Olfactory bulb/tract/nuclei | Y (244) | Y (230) | F |

| Amygdala (AMY) | ? (244) | Y (3, 229, 230, 238, 240, 244, 248) | CF |

| Primary olfactory cortex | ? (244) | Y (230) | C |

| Infralimbic prefrontal area | Y (3) | ||

| Insular cortex | Y (3, 230, 238, 240, 249) | F | |

| Perirhinal cortex | Y (3, 249) | F | |

| Entorhinal cortex | Y (230) | C | |

| Cortical layers II–VI | Y (193, 246) | C | |

The identification of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in a particular area is indicated as Y or N, indicating yes or no, respectively. “?” indicates” either none or very low expression. In these studies it is possible that expression could be localized to a very few cells, but in early publications it is not possible to discern this level of detail from the images. It is difficult to ascribe some regions as Y or N. Some studies are conflicting, either reporting presence or absence of CGRP. These have been described as “Y” because of the overall consensus, but the references that also report an absence have also been cited for completeness. For peptide expression, this is then further defined as cell body (C) or fiber (F) immunoreactivity from histological studies. The table lists ganglia, followed by cranial nerve nuclei (associated cranial nerves shown in brackets) and then brain regions from brain stem forward. The citations provide a representative sample from a large volume of literature.

3.2. Nervous System

3.2.1. Peripheral ganglia.

One of the earliest known sites of CGRP expression was the TG, a finding that has been replicated in many independent studies (3, 5, 226–228, 251–253). Numerous reports have led to the consensus that CGRP mRNA and peptide are robustly expressed in the TG and DRG; they are detected in ∼30–50% of neuronal cell bodies. Several representative studies are cited in TABLE 1. Most CGRP-positive neurons are small or of medium size; the largest neurons (>45 µm in diameter) tend not to be CGRP positive (107, 108, 111, 227). Some mRNA data suggest that CGRP is more highly expressed in the DRG than in the TG (254). In DRG, CGRP has been reported in C, Aβ, and Aδ fiber neurons (255). CGRP immunoreactivity in the TG and DRG typically manifests as dense cytoplasmic staining (in small neurons) or granular staining (in the vesicles of medium-large neurons), consistent with its role as a neuropeptide. Expression of CGRP is commonly observed in fibers as pearl-like CGRP immunoreactivity (107, 108, 111, 256). Few detailed comparisons of CGRP abundance or cellular localization across the three trigeminal nerve branches are available, but expression has been noted in all three (257). In the case of the DRG, CGRP is found at the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral levels (258). CGRP is also expressed in the nodose ganglia (227). The expression of CGRP in glial cells of the TG and DRG is inconsistent, with CGRP mRNA and immunoreactivity reported as present or absent in different studies, although in most studies glia do not appear to be CGRP positive (3, 47, 226, 254, 259, 260). Nonetheless, glial CGRP expression may be subject to regulation by inflammatory stimuli, and thus glia may be an additional source of CGRP under certain conditions (90, 261). Glial CGRP expression within the TG could contribute to paracrine cross talk and neural sensitization (151, 256).

3.2.2. Central nervous system.

As is evident from TABLE 1, CGRP expression in the CNS is very widespread. This expression extends from the brain stem through to the cortex and encompasses discrete nuclei and extensive fiber networks. CGRP is abundant in sensory and motor cranial nuclei. A large body of research has focused on the relationship between CGRP expression and brain regions that contribute to migraine. For example, CGRP mRNA and pearllike immunoreactivity are prevalent in the fibers of the spinal trigeminal nucleus in rodents and humans (171, 262, 263). In general, these studies have been highly concordant, but, unsurprisingly for such a large volume of data, there are also inconsistencies. For example, expression in the cerebellum can be ambiguous. One study reported that the dendritic arbors of Purkinje cells in the molecular layer were often CGRP positive. Also, a low to moderate density of CGRP-immunoreactive fibers was detected in the nucleus cerebellaris lateralis; such fibers were also present in other cerebellar nuclei but were less conspicuous there. This study also reported detecting a few CGRP fibers in the cerebellar white matter (240). However, mRNA was not detectable in Purkinje cells (231). A comparison of CGRP immunoreactivity in human and rhesus monkey cerebellum showed immunoreactivity in Purkinje cells, both in the cytoplasm of cell bodies and in dendrites, and within cells in the molecular layer (170). Interestingly, not all Purkinje cells contained CGRP. TABLE 1 provides additional citations for studies that have examined CGRP immunoreactivity in rodent cerebellum. It may be that overall expression levels are quite low in the cerebellum but there are discrete cells or locations that contain more substantial levels of CGRP immunoreactivity. Data for the thalamus are also difficult to interpret (TABLE 1). In part, this is due to the fact that the thalamus contains many nuclei the nomenclature for which has changed significantly over time. Most studies report that CGRP is detected in fibers in the thalamus, but cell body staining has also been reported (193). A further consideration is whether immunoreactivity is associated with neurons or other cell types. For example, one study reported CGRP in the rat cortex, but it was colocalized with alpha smooth muscle actin and Claudin-5, suggesting that it is present in cortical blood vessels rather than neurons (264).

3.2.2.1. spinal cord.

The spinal cord is innervated by a dense network of fibers that are immunoreactive for CGRP. These are located in laminae I and II of the dorsal horn, which includes fibers originating in the TG and DRG. Cell bodies immunoreactive for CGRP are also present in the spinal cord. In the dorsal horn, CGRP-expressing excitatory interneurons have been reported (265). The sensory expression of CGRP has held the greatest prominence in recent years, but it is important to recognize that CGRP is also found in motor neurons. Large cells immunoreactive for CGRP are found in the ventral horn of the spinal cord. Large CGRP-positive neurons are noted in areas associated with innervation of large muscles (258). CGRP mRNA is also found in motoneurons of the ventral horn, indicating that CGRP is actually synthesized in these cells (266). Similar patterns of expression have been observed across species, at the cervical, lumbar, and thoracic levels of the spinal cord. Spinal cord CGRP has been quantified across dorsal and ventral cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions (172).

3.3. Other Sites of Expression

As a consequence of its presence in nerve fibers, CGRP can be found in many locations throughout the body. To avoid duplication, we describe many sites of expression in relation to a particular function elsewhere in this review. Other sites of expression could reflect functions that have not been deeply explored. Examples include the tongue (fibers), soft and hard palates, epiglottis, and esophagus (267). Similarly, the nonneuronal sites briefly covered in sect. 1.2 merit further consideration.

3.4. Specific Consideration of β-CGRP Expression

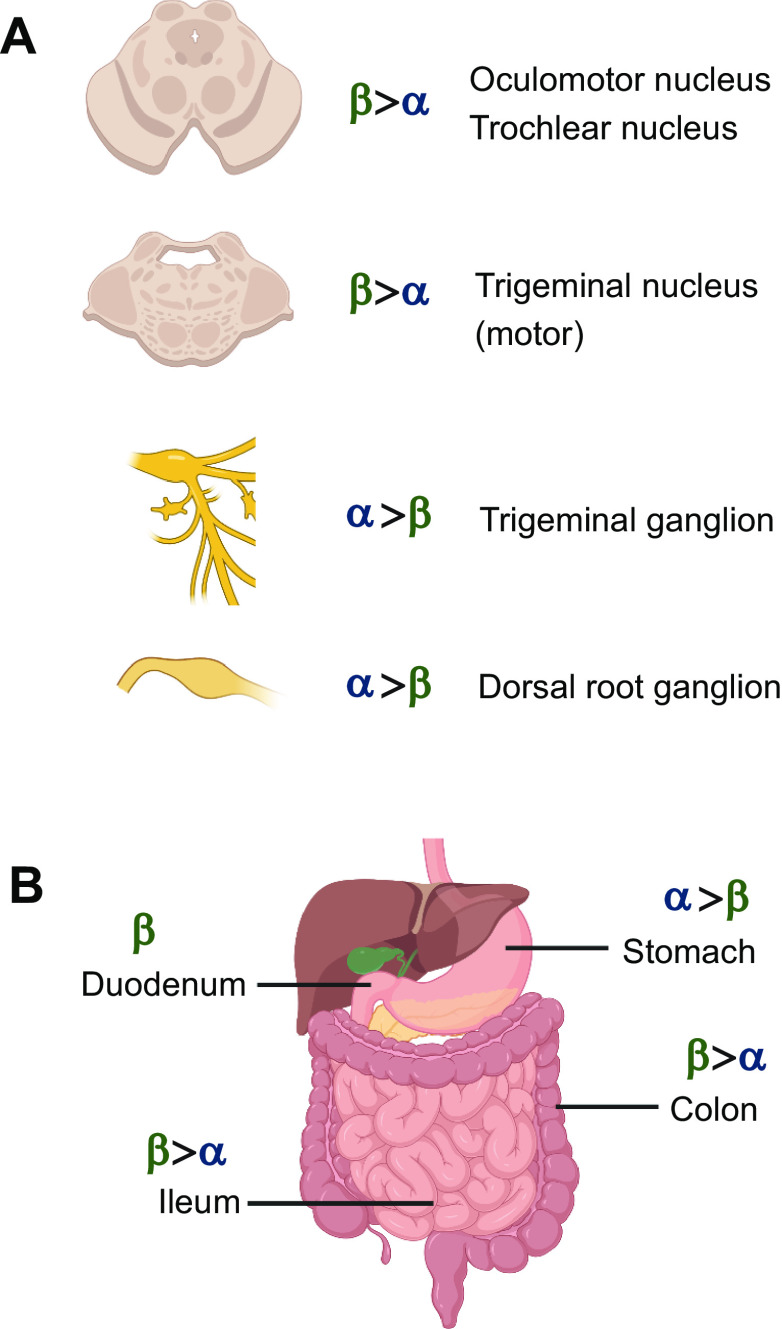

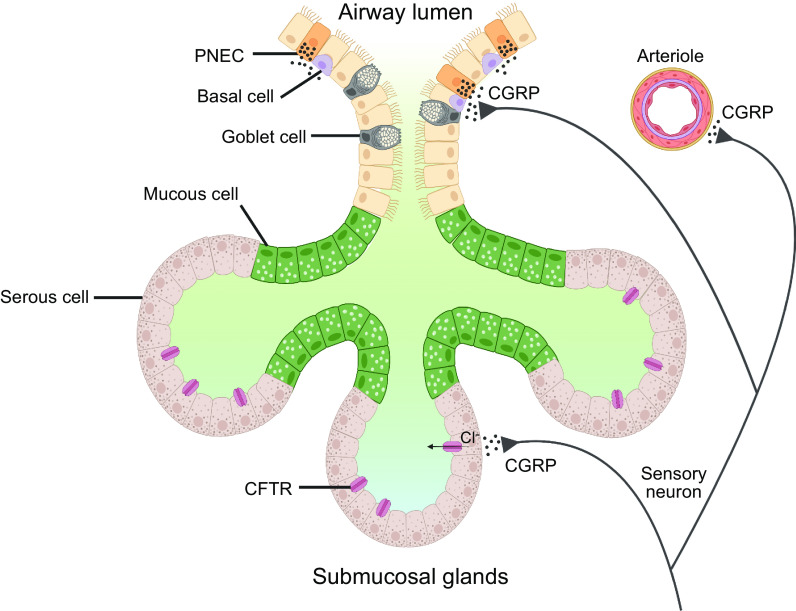

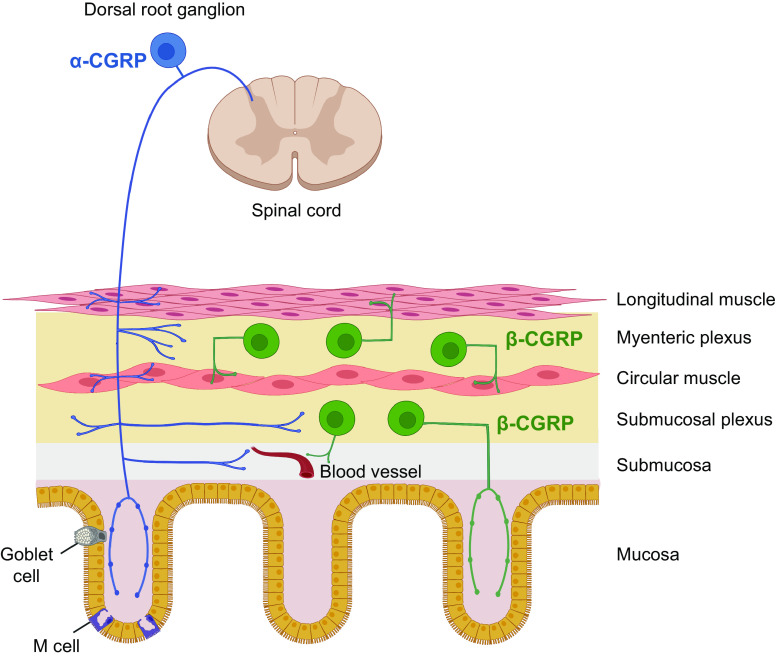

Although the distributions of α-CGRP and β-CGRP predominantly overlap, β-CGRP has been reported as the major isoform in the enteric nervous system (31, 232). However, this does not mean that this is its exclusive site of expression. The high amino acid sequence identity of the CGRPs has made it difficult to develop specific probes for each peptide, but the available data show that β-CGRP expression is widespread. The two isoforms differ in relative abundance, and occasional reports have suggested the exclusive expression of only one form at particular sites. Expression in the enteric nervous system is described in sect. 5.7 on gastrointestinal physiology (see also summary in FIGURE 6) (30, 31, 232). Other sites of expression are outlined here, and some are summarized in FIGURE 6. The cited literature covers human and rodent.

Figure 6.

Selected sites of expression of α-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and β-CGRP, with relative expression indicated. A: sites of expression in the nervous system. B: sites of expression in the gastrointestinal tract, including expression from extrinsic and intrinsic nerves. In many locations, such as the trigeminal ganglion and dorsal root ganglion, α-CGRP expression exceeds β-CGRP expression, whereas in other locations the reverse is true. Note that human anatomy is shown for simplicity but the majority of supporting literature is rat and mouse (30, 31, 232). Image created with BioRender.com, with permission.

Some studies have been particularly informative with respect to the expression of the two isoforms. For example, in their seminal work, Amara and colleagues showed that β-CGRP mRNA was expressed in the TG, lateral medulla, hypothalamus, and, to a lesser extent, the midbrain. Cerebellar signal was thought to be nonspecific. Hybridization to probes specific for each mRNA was observed in the TG; the motor nuclei of the third (oculomotor), fourth (trochlear), fifth (trigeminal), seventh, tenth, and twelfth cranial nerves; cells of the ventral horn (motoneurons); and other brain nuclei including the parabrachial and peripeduncular (30). Among the many sites of expression, the hybridization signal was greater in the TG for α-CGRP. This is consistent with other mRNA data suggesting that the expression of β-CGRP can be up to 10-fold lower than that of α-CGRP (232, 268,269). In contrast, in the nuclei of the third, fourth, and fifth cranial nerves the β-CGRP hybridization signal was greater than that for α-CGRP (30). In other areas, the signals were often equivalent (30). The mRNA encoding β-CGRP is also found in the DRG and spinal cord (7, 31, 233, 234, 266, 270). Recent studies using RNA-seq also identified β-CGRP in sensory ganglia (268, 271).

Peptide, rather than mRNA, data tell a similar story, supporting the evidence that β-CGRP is widely expressed. For example, important early data indicated that β-CGRP is present in the spinal cord, cerebellar cortex, and thalamus and that the concentration of β-CGRP is higher than that of α-CGRP in the cerebellum and thalamus (272). Data from α-CGRP knockout mice suggest that α-CGRP and β-CGRP are typically coexpressed, although the relative quantities of each varies (232). Interestingly, β-CGRP was expressed primarily in small neuronal cell bodies in the DRG as puncta, indicating a presence in vesicles.

Intriguing reports of differential or regulated expression of β-CGRP suggest that greater scrutiny of its functions may be worthwhile. For example, cultured normal human epidermal keratinocytes had between ∼8- and 12-fold greater β-CGRP than α-CGRP mRNA expression, depending on the culture conditions (14). Similarly, epidermal keratinocytes derived from two different transgenic mouse lines (BMP4 and noggin) had greater β-CGRP than α-CGRP mRNA expression (∼3.5-fold) (14).

3.5. Comparison Between Species and Sexes

The broad anatomical distribution of CGRP appears to be largely similar across species (221, 273). This includes expression in the spinal cord, TG, spinal trigeminal tract, PBN, and thalamus (47, 107, 172, 174, 274).

For many early studies, either the sex of animals used was not reported or only males were used. This makes it difficult to draw comparisons between male and female. There is, however, some evidence suggesting that CGRP expression is sexually dimorphic and that it is regulated by estrogen (275, 276). Peripheral inflammation due to administration of complete Freund adjuvant increased CGRP expression in female TG to a greater degree than in male mice (277). In female mice, significantly fewer neurons in the DRG were CGRP positive than in males (275). This difference appeared to be linked to activation of the estrogen receptor, which is coexpressed in DRG neurons. Consistent with this possibility, CGRP expression in the same neurons of ovariectomized females was similar to that in males. CGRP expression was lowered when ovariectomized mice were treated with estrogen, mimicking the lower-level expression observed in intact females (275). In the medulla of female rats, levels of CGRP mRNA were significantly higher than in males (191). In addition, the number of CGRP mRNA and peptide-positive cells in the medial preoptic nucleus was higher in female than in male rats (278, 279). The reverse was apparent in some hypothalamic regions, with the number of CGRP-positive cells higher in males than in females (280). Thus, there appear to be regional differences in CGRP levels between male and female rodents. Additional considerations on CGRP and sex are given in sects. 5.8 and 6.3.

4. CGRP RECEPTORS

4.1. Overview and Historical Perspective

Like the CGRP peptides themselves, CGRP binding sites are found centrally and peripherally (281). Two factors are important for weighing the relevance of binding sites: abundance and relative affinity. Sites in which the density of CGRP binding sites is high include the cerebellum, nucleus accumbens, substantia nigra, spinal cord, atria, vas deferens, and spleen (FIGURE 5). High-affinity binding sites are found in the brain (e.g., the cerebellum; FIGURE 5) and peripheral tissues including in the heart (atria and ventricles), liver, spleen, skeletal muscle, lung, and lymphocytes (281, 282). CGRP binding is sensitive to guanine nucleotides, suggesting that its receptors are members of the cell surface-localized GPCR superfamily. More specifically, receptor activation causes cAMP levels to increase, suggesting that they are of the Gαs-coupled type. Deconvoluting the molecular composition of these CGRP binding sites proved challenging, with several false starts over a number of years. Some of the literature still refers to other receptors that have been proposed as CGRP receptors, although the experimental evidence does not support this classification (28).

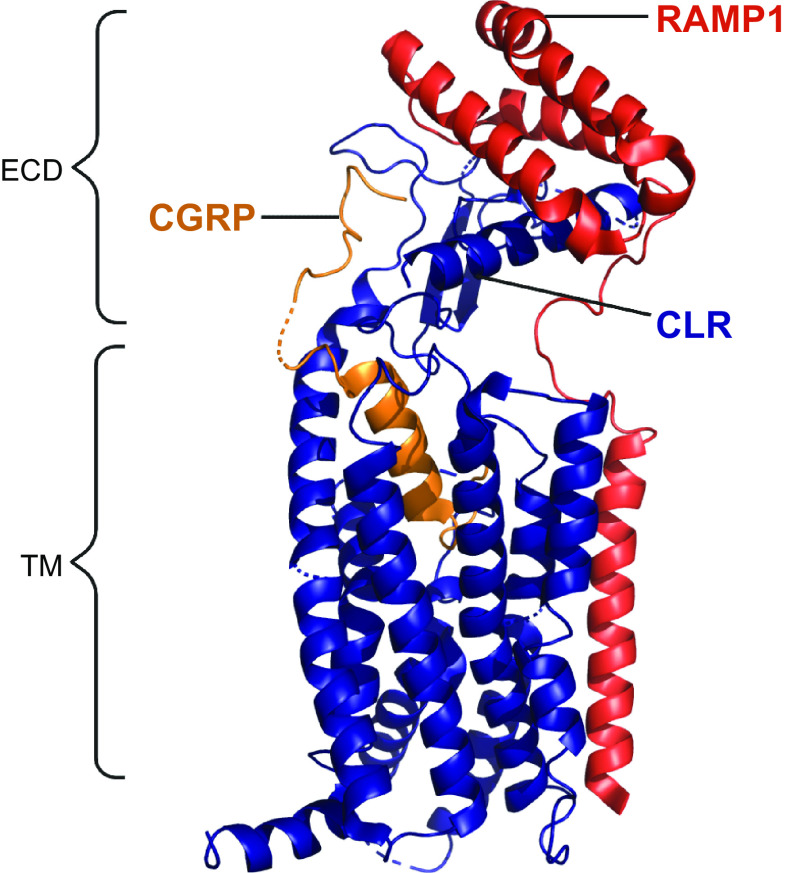

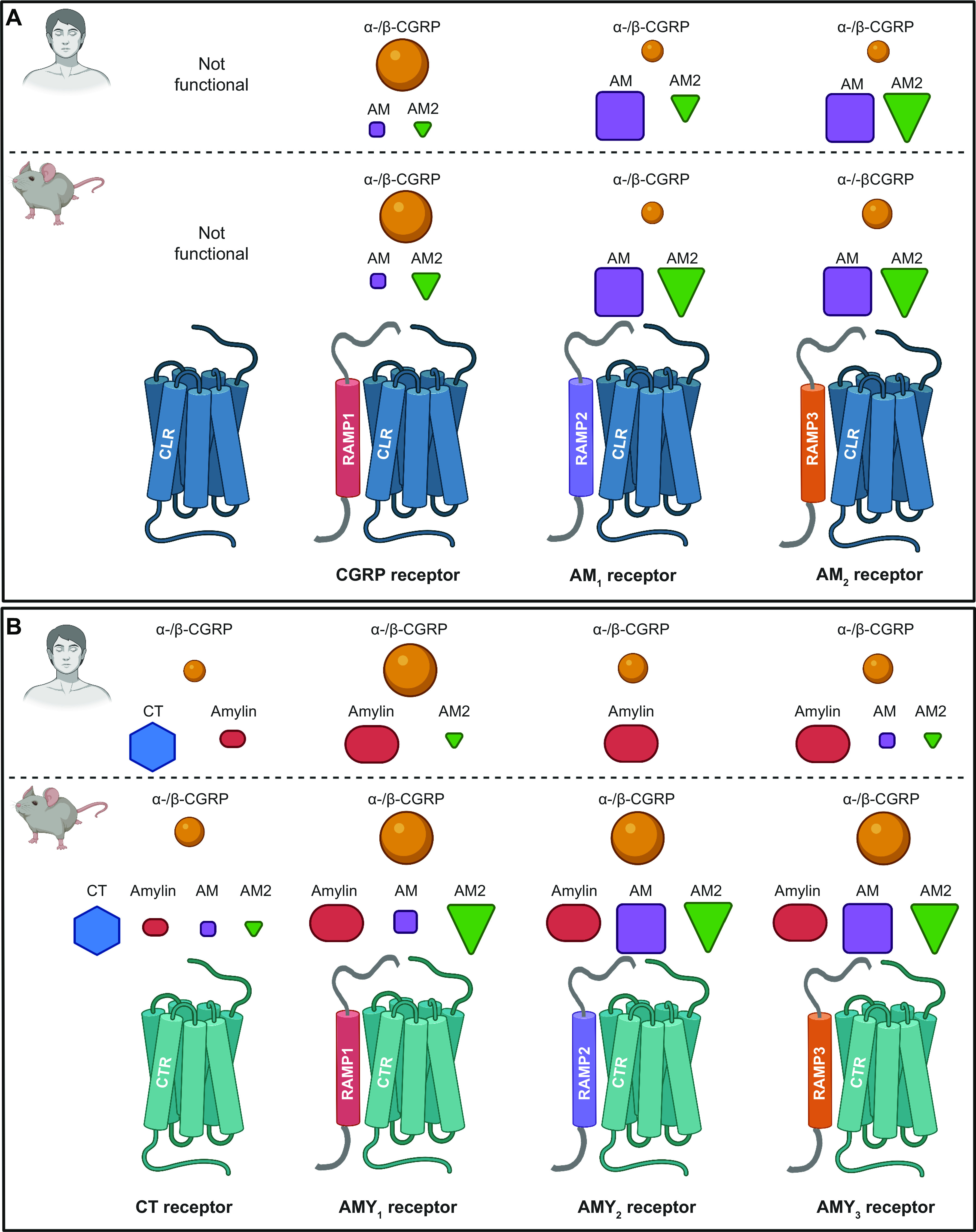

In the early-mid 1990s, the most likely GPCR candidate for a high-affinity CGRP receptor was the calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CLR). This was because of its high level of amino acid sequence identity to the CTR, whose cognate ligand, calcitonin, itself shares amino acids with CGRP (FIGURE 2) (283–285). However, it took several more years to discover that CLR required an accessory protein, receptor activity-modifying protein (RAMP)1, to reach the cell surface and to bind CGRP with high affinity (286). This combination of CLR and RAMP1 was then put forward as a likely candidate for the “CGRP1” receptor previously reported in the literature (28). This receptor was potently activated by CGRP, was effectively antagonized by the antagonist peptide fragment CGRP8-37, and could be activated by AM as well as by CGRP, though with lower potency. The tissue distribution of CLR and RAMP1 aligns with the presence of CGRP binding sites (273, 282). For example, there was a statistically significant correlation between RAMP1 mRNA and CGRP binding across eight rat tissues (heart atria and ventricles, cerebellum, spinal cord, liver, spleen, vas deferens, lung) (282). Thus the CLR/RAMP1 complex was formally ratified as “the CGRP receptor” in 2002 (FIGURE 7) (28).

Figure 7.

Members of the calcitonin family of receptors, showing their molecular composition and relative preferences for endogenous agonist peptides, comparing human and mouse pharmacology. A: calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CLR)-based receptors with associated receptor activity-modifying proteins (RAMPs). B: calcitonin receptor (CTR)-based receptors with associated RAMPs. For A and B, CLR or CTR combines with either RAMP1, RAMP2, or RAMP3 to form receptors for calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), adrenomedullin (AM), adrenomedullin 2 (AM2), calcitonin (CT), or amylin. In A and B, the agonist pharmacology at human receptors is shown at top above the dashed line and at mouse receptors at bottom. The relative size of the peptide ligand symbol indicates the relative potency. A large symbol indicates that this is the most potent/cognate ligand or is approximately equal in potency to the cognate ligand, a medium-sized symbol indicates a ligand that is approximately ≤10-fold less potent than the cognate/most potent ligand for that receptor, and the smallest-sized symbol represents a ligand that is between 10- and 100-fold less potent than the cognate/most potent ligand for that receptor. In all cases, other ligands have been tested, but their potency is >100-fold less potent than the cognate/most potent ligand for each receptor at which they have been tested and they are therefore not shown. A broad consensus is given, using species-matched ligands where possible and using data from multiple studies, as summarized in www.guidetopharmacology.org. Thus, at the human CGRP receptor, CGRP (α-CGRP and β-CGRP) is between 10- and 100-fold more potent than AM or AM2. Mouse receptors are activated by more ligands. CLR is functional only with RAMP, as it cannot reach the cell surface without it (286, 287). CTR can act as a receptor for calcitonin without RAMP. Splice variants of CTR can also partner with RAMPs to create additional receptor subtypes; the figure represents CT(a). Image created with BioRender.com, with permission.

We now know that the CLR/RAMP1 complex is an important receptor for CGRP. However, numerous activities of CGRP cannot easily be blocked by CGRP8-37 and/or have functional behavior that does not precisely match that of the CLR/RAMP1 complex. These can be found in the literature as pharmacological phenotypes consistent with a “CGRP2” receptor (288–295). This nomenclature is not currently used because it continues to be difficult to assign a molecular identity to endogenous receptors that exhibit such profiles, but the existence of “noncanonical” CGRP receptor pharmacology is as valid now as when it was first described. Detailed pharmacological profiling of receptors that are related to CLR/RAMP1 shows that several potential candidates could explain functional “CGRP2” receptor phenotypes.

4.2. Molecular Composition

Identification of the CLR/RAMP1 complex as a high-affinity CGRP receptor was accompanied by the identification of two further RAMPs, RAMP2 and RAMP3 (286). At around the same time, RAMPs were found to associate with the CTR (296, 297). Efforts to deconvolute the agonist pharmacology of these receptors led to the current classification scheme, which is summarized in FIGURE 7 (23, 28). Accordingly, it is now well established that the calcitonin/CGRP peptide-receptor family comprises two GPCRs (CLR and CTR) with or without (for CTR) the three RAMPs. CLR with RAMP1 forms the canonical CGRP receptor, whereas CLR with RAMP2 or RAMP3 generates the AM1 and AM2 receptors, respectively. This nomenclature was developed based on evidence that the preferred ligands for these receptors were CGRP and AM peptides, respectively. Since then, however, the AM2 peptide was discovered and collated data from multiple studies indicate that, like AM, it is capable of activating all three receptors but seems to have a slight preference for the AM2 receptor when considering human receptors, upon which nomenclature is based (FIGURE 7) (23). In time, the nomenclature could be updated to reflect this, but additional work is needed to confirm that the AM2 peptide is the endogenous ligand for the AM2 receptor (23). An additional player in the function of the CGRP receptor in particular is receptor component protein (RCP), which appears to help the receptor to couple to G proteins (298). Studies on RCP are ongoing, but interpretation of RCP functions as a modulator of receptor signaling may be complicated by the possibility of nuclear functions, since RCP has been reported to be a subunit of RNA polymerase III (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O75575).

CTR is a functional receptor for calcitonin in the absence of RAMPs. When CTR interacts with a RAMP, it forms the AMY1, AMY2, or AMY3 receptor, respectively (FIGURE 7). This nomenclature reflects the high affinity of amylin for each of these receptors. However, CGRP is also a high-affinity ligand for the AMY1 receptor, as further detailed in sect. 4.3. This receptor has been part of the “CGRP2” receptor conversation for many years (288, 289, 299).

Further diversity within this receptor family is apparent from the CTR (polymorphic and splice) variants, and when their combination with RAMPs is considered further subtypes of receptor are possible: AMY1(a), AMY1(b), and so on (28). This nomenclature reflects the CTR splice variant CT(a) or CT(b), respectively. The CTR splice variants differ to some extent in their functional properties and can also differ between species, and in general they are poorly studied (28, 300, 301). Notably, this can affect CGRP pharmacology (302). In humans, an additional splice variant that lacks the initial 47 amino acids of the receptor NH2 terminus is especially well activated by CGRP (302). The significance of this in physiological terms is unknown, but it indicates the potential importance of CTR splice variants in the activities of peptides beyond calcitonin and amylin.

4.3. Pharmacology: Agonists and Antagonists, and Species Differences

The agonist and antagonist pharmacology of CGRP and related receptors is regularly updated and provided as a resource online via www.guidetopharmacology.org. From time to time, consensus statements are published in collaboration with the International Union of Pharmacology Receptor Nomenclature Committee (NC-IUPHAR) to update the overall status of receptor pharmacology and nomenclature. The reviews to note are Ref. 28, which provides the original nomenclature; Ref. 288, which discusses considerations for CGRP1 and CGRP2 receptors; and Ref. 23, which provides more recent updates.

4.3.1. Agonist pharmacology.

FIGURE 7 shows the broad consensus for the relative agonist potency of endogenous ligands at human receptors. From most to least potent, the agonists of the CGRP receptor are α-CGRP and β-CGRP, AM and AM2. Although capable of activating the CGRP receptor at high concentrations, amylin is a weak agonist of the human CGRP receptor, being >100-fold weaker than CGRP at activating this receptor (23). The AM receptors are both activated by AM and AM2. CTR is potently activated by calcitonin and to a lesser degree by amylin, but the potency and/or affinity of the latter increases in the presence of each RAMP. Importantly in the context of CGRP, RAMP1 in particular increases the affinity of the CTR for CGRP. The result is the AMY1 receptor, which the collective evidence suggests is equipotently activated by CGRP and by amylin (23). The pharmacology of β-CGRP is very similar to that of α-CGRP, but an analysis for several literature studies showed that on average β-CGRP is approximately fivefold more potent than α-CGRP at the AMY1 receptor (23).