Abstract

The southwest coastal belt of Bangladesh is characterized by a fresh and saline water interaction which gives rise to a discrete inter-saline freshwater convergence zone (ICZ). Hydrology and farming along this transition zone is influenced by upstream and downstream abiotic factors including salinity intrusion and water flow. To better understand the changing geography of the transitional ICZ line and the relative influence of these hydrological events on farming therein, the recent study compared relative changes from 2010 to 2014 based on qualitative and quantitative survey work with 80 households of 4 villages (Shobna, Faltita, Badukhali and Rudaghora) from Khulna and Bagerhat district. Contrary to the conventional hotcake climate change induced salinity intrusion the study found a significant decrease in saltwater influx and increased freshwater volume in the ICZ villages, reflecting a seaward movement trend. Farmer perception shifted to low saline and freshwater in many areas where it was high saline and medium saline in 2010. The factual and perceived salinity were varied from 1 ± 0.44 to 2 ± 0.77 ppt in the studied villages. To confront the condition farmer diversified their farming pattern from single crop like either only shrimp or prawn culture to concurrent culture of shrimp-prawn, shrimp, prawn and rice with an increased production of (68-204 kg/ha), finfish (217-553 kg/ha) and dyke crop (92–800 kg/ha). Thus, affecting the socioeconomic condition of the farmer with an increase in average monthly income, reported for the better-off classes in 2014, ranged from 14,300 to 51,667 BDT and for the worse-off ranged from 5000 to 9900 BDT. In contrast, this average monthly income was 9500- 27,000 for better-off and 3875 - 8600 for worse-off classes, reported in 2010. Besides, farming areas (average 17% for better-off and −0.5% for worse-off) and land leasing (average increment rate per ha 50%) also increased among the surveyed farmers, reported in 2014 compared to 2010. In addition, several adaptation strategies like unrefined salt use, change of water use, diversification through prawn, finfish and dyke crops along with traditional shrimp and overall land use change have a positive impact on farmer’s economic and nutritional security as well as farming intensity. The study showed a unique attributes of salinity extrusion in micro-level of ICZ line where farmers intensified farming system with indigenous knowledge to secured their livelihoods.

Keywords: Seafood, Salinity, Coastal livelihood, Climate change, Bangladesh

1. Introduction

Bangladesh is located at the mouth of the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) basins and is widely recognized as a country with high sensitivity to climate change variabilities [1,2] These climate variabilities of tidal floods and cyclones are often faced at the low-lying waterfront territories of Bangladesh’s southwest (SW) region by frequently affecting the salinity of the coastal zone that leads to a subsequent shift in the coastal people’s land use pattern and farming system [3,4]. Indeed, sea-level rise (SLR)1 can push the saltwater intrusion further inland leading to a salinity level rise in this SW coastal region. Such salinity intrusion occurrences often deter the farmers from engaging in agricultural farming as these instances combined diminish their land and plant productivity [[5], [6], [7], [8]].

The SW regions of Bangladesh mainly include Satkhira, Khulna, Bagerhat, and the southern part of Jassore districts, which comprise a unique inter-saline–freshwater convergence zone (ICZ) [9] or brackish water ecosystem. During the wet season, local rainfall associated with flood flows from upland regions keeps the salinity level near acceptable [[10], [11], [12]]. However, this salinity continues to increase between early November to May when the winter season begins and rainfall stops [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. Although the seasonal variation of climate change and sea-level rise can increase the salinity, siltation and/or sedimentation of canals can prevent saltwater intrusion into the coastal farming zones [17]. Besides, development projects like Coastal Embankment Project (CEP) and the Farakka Barrage have affected the geology, and environment [18], which enclosed approximately one million hectares of land detaching the wetlands from the river system [19,20].

As a consequence, various changes had been observed like tidal inundation on both sides of the rivers was halted [[21], [22], [23]], siltation and sedimentation rate accelerated within their primary river system [24] and also river basin’s hydrology was changed. In Overall the adjacent river systems was destroyed, which was the primary route for salinity intrusion in these region [25,26]. Spatial variation in the levels of soil salinity is extremely high; both extremes can be found within a meter to two, even in the same field. Once an area is salinized, it takes at least 15 years to desalinize by annual precipitation. Some soil and land management may augment the desalinization process and land may become productive after 8–10 years [27].

Many studies have identified adaptations as potential solutions to confront vulnerability due to climate change-driven sea-level rise and salinity effects in coastal areas [[28], [29], [30], [31]]. Tran et al. assessed the livelihood vulnerability and adaptation of two coastal communities to extreme saltwater intrusion and droughts in Soc Trang province of the Vietnam Mekong Delta and found diversification of farming system is one of the preferred adaptation options [28]. Wijayanti and Pratomo, analyzed the adaptation to the vulnerability of socio-economic activities for coastal communities of Semarang, Indonesia [31]. The adaptation was found in social and economic livelihoods based on natural resources (i.e., pond fish cultivation) and other factors (i.e., change to industrial jobs, taxi driver, and/or trading businesses). In Bangladesh the traditional agricultural crop production system in SW region was transformed by the adoption of black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon) and giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) farming in saline and freshwater, respectively [[32], [33], [34], [35]]. Paddy fields were modified by constructing peripheral trenches suitable for shrimp or prawn farming with building dykes to prevent flooding or escape [36]. Milstein et al. stated that traditionally, this modified paddy field is called “ghers,” where farmers adopt shrimp, prawn, and/or finfish alternatively or concurrently [37].

Several studies have assessed the salinity intrusion and adaptation strategies in the SW region of Bangladesh [[38], [39], [40], [41]]. Lam Y.et al. studied the effect of salinity intrusion in SW region, particularly in Saatkhira, Khulna and Bagerhat regions, where people at the community level was adapting through improved irrigation and floodplain management, as well as restrictions on saltwater aquaculture to abate salinity [38]. Shameem et al. focused on other adaptation options like adjustment to aquaculture practices in addition to agriculture [39]. Out of the adaptation option, crop diversification is a significant strategy to improve the coastal people’s livelihoods by generating revenue from this sector [38,42]. Such diversification efforts can also improve the gher efficiency [43].

However, although research examining the salt extrusion and the resilience of coastal populations in relation to climate change are few, adaptive strategies to address salinity incursion susceptibility are extensively documented. Previous research on salinity intrusion and climate change suggested salinity is increasing in this area, and it would be expected to see a northward moving ICZ [[44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51]].

Realizing the importance of sustainability of farming system and livelihood current study is planned to assess the trend of salinity in the study area and how people are adopting their farming practices with the changing salinity based on qualitative and quantitative survey work in two phases. Therefore, the central question for this study in the exploratory phase was what the trend of salinity in the study area is and what possible factors are driving the trend? The question for in depth study was how farmers adopting their farming practices with changing water and salinity. Hence, we have envisioned addressing such adaptation strategies that coastal farmers can adopt during the chronic and/or acute salinity intrusion situation.

2. Methodology

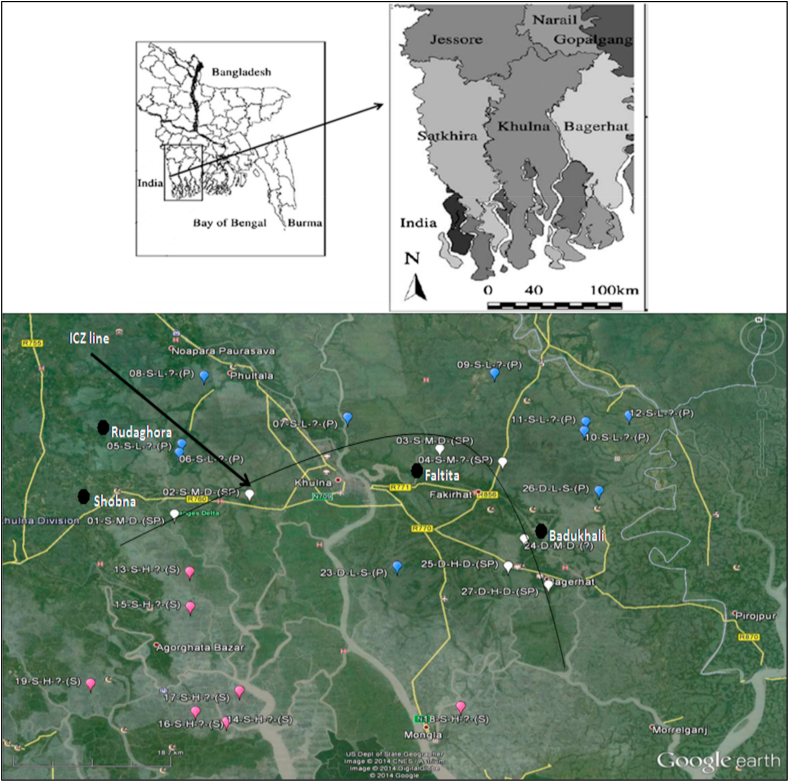

A combination of trend line analysis and on-farm fieldwork survey was conducted on the ghers in Khulna and Bagerhat districts of Bangladesh between 2010 and 2014 (Fig. 1). We have collected the primary data from 24 villages, which were selected randomly based on the previous research executed by theEU funded SEAT (Sustaining Ethical Aquaculture Trade) project (n = 19) and GOLDA (Greater options for local development through aquaculture) projects (n = 5), respectively, SEAT project unearthed the east-west line of semi-saline conditions between Khulna and Bagerhat districts and thereafter, named the ‘Inter Saline Convergence Zone’ (ICZ line; [52]). In order to gather the necessary data for the in-depth study, 24 villages were targeted in the first phase, which was termed the exploratory phase of the project. Out of 24 villages half of them were purposively selected based on previous study outcomes and KI consultation. Among 12 villages three different agro-ecologies were identified for this study to understand the salinity trend and farmer’s perception to the changes:1) inland (north) of the ICZ line is characterized by FW prawn farming (for example Rudaghora, Modhupur, and Alipur village); 2) on-line of ICZ line is characterized by shrimp and FW prawn farming (Shobna, Gutudia, Balati, Faltita, Badukhali, and East Sayera village) and; 3) towards the sea of ICZ (south) is characterized by shrimp farming dominating (Magurakhali, Rampal, and Kumerkhali). Out of the 24 communities in the first phase, four were chosen for the second phase. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to perform a detailed investigation during the second in-depth phase.

Fig. 1.

Map of southwest regions of Bangladesh showing the Inter saline Convergence Zone (ICZ) line. Blue indicates a prawn-dominated farming system, white indicates prawn and shrimp farming, and pink indicates the shrimp clusters in SW region examined (Source Murray 2010). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

2.1. Phase-1: exploratory phase

To determine the farming and salinity trends between 2010 and 2014, we conducted the first phase of our study based on some key guiding questions. The questions included mainly farmers perception on salinity trend, causes of salinity change and their reaction to the changing salinity. Three key informants (KIs), primarily elders and local leaders with farming experience, were questioned on the spot in 12 communities. To analyze the KIs' practical experiences to determine the salinity level of the water without the use of external measurement tools, we requested them to take part in a straightforward gustatory test of salinity [53,54]. A refractometer (Model: RGBS-MR0007) was used to prepare four samples at rates of 0.5, 5, 10, and 15 ppt (parts per thousand), and participants were asked to rank the solutions according to salinity. Then we asked them to choose the best options for their prawn and shrimp farming.

At the start of the rainy season, when soil and water salinity are at their highest, spot refractometer test readings were also made in nearby ghers and rivers/streams [41]. These on-site salinity measurements are consistent with the salt solution test results that the key informants supplied to support their understanding of salinity changes. Ten knowledgeable farmers (excluding KIs) per community participated in semi-structured questionnaire interviews and salinity taste tests. For the purposes of validating farmers' impressions, participants were chosen at random by the different KI's.

2.2. Phase two: in-depth study

In a second phase, four villages—Shobna, Badukhali, Faltita (on the ICZ line), and Rudaghora (inland of ICZ)—were chosen for a thorough investigation (from phase one). Selection criteria included salinity extrusion factors (such as river siltation, inadequate polder and sluice gate management), as well as adaptation options such artificial salt use for shrimp farming, additional freshwater fish farming, and dyke vegetable cultivation. Semi-structured qualitative interviews were employed to support and clarify the study area's quantitative patterns. The same KI's who participated in the exploratory phase of the study were asked to rank farmers and communities according to various categories of perceived wealth. From Shobna, Faltita, Badukhali, and Rudaghora villages, a list of 51, 110, 39, and 21 fish farmers was compiled (chosen at random), representing about 6% of farming households. Based on three indicators—land size, income, and house type—they divided the farmers into four well-being levels: rich (W1), medium (W2), poor (W3), and ultra-poor (W4). Rich and medium were designated as the “better-off” classes, while poor and ultra-poor were designated as the “worse-off” classes [55]. Key informant characteristics of the primary well-being indicators that were modified by household surveys in the aquatic farming regions of southwest Bangladesh (Appendices Table A1). 20 fish farmers were chosen at random from each village's households to participate in in-depth interviews. In the comparable communities, a draft questionnaire was pre-tested before being modified for use. Socioeconomic data for households, the effects of salinity change on farming methods, and the farmers' adaptation techniques to deal with such salinity change were among the topics covered.

The semi-structured questionnaire was prepared through a robust literature review and personal experiences. The questionnaire was pre-tested/piloting in a similar settings. After piloting questionnaire was reframed and maintained chronology to get data in a logical way. The questionnaire was preferred in English and then translated into Bengali for easy operation.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Survey data were coded, for exploratory analysis in Microsoft ExcelTM and geographic features study villages visualized in Google maps. Differences between socio-economic groups were evaluated using ANOVA (SPSS Version 25). Differences were considered significant at the 5% level. Qualitative survey data was used to triangulate and interpret outcomes of the exploratory and statistical analysis described above. The values of latitude and longitude were collected by a German GPS (Global Positioning System) machine (Germin eTrex 22x Handsheld GPS). The GPS data were collected from each selected community for the study. After that these data were used to create study area map through google map.

3. Results

3.1. Community perception of salinity levels

With situations ranging from fresh water to brackish (>10 ppt), salinity level testing with KI's and farmers showed an overall accuracy of 82% compared to real world (through refractometer) results. With the exception of Faltita village, variations between individual farms and the closest surface water supply were minor (Table 1). Except for Magurakhali and Rampal, respondents in every village thought that the salinity had been diminishing recently.

Table 1.

Farmer perceptions of water salinity in fields and local surface water sources during peak saline season between 2010 and 2014.

| Village | Field salinity according to farmer’s perception |

changing pattern |

Average refractometer reading found on farming land, in 2014; n = 10/village (A) | Refractometer reading on near water body in 2014; n = 10/village (B) | Salinity difference between farming land and near water source (A-B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2014 | |||||

| Rhudaghora | MS | LS | _ | 1 ± 0.77 | 5 ± 0.47 | 4 |

| Modhupur | MS | LS | ∼ | 1 ± 0.89 | 6 ± 0.34 | 5 |

| Balati | MS | LS | ∼ | 2 ± 0.45 | 6 ± 0.44 | 4 |

| Gutudia | MS | LS | ∼ | 1 ± 0.74 | ND | ND |

| Shobna | MS | LS | _ | 2 ± 0.45 | 5 ± 0.77 | 3 |

| Magurakhali | MS | HS | + | 11 ± 0.64 | 16 ± 0.47 | 5 |

| Faltita | MS | FW | _ | 1 ± 0.42 | 16 ± 0.51 | 15 |

| Badukhali | HS | LS | _ | 2 ± 0.77 | 6 ± 1.63 | 4 |

| East Sayera | HS | FW | _ | 1 ± 0.87 | 1 ± 0.92 | 0 |

| Kumerkhali | MS | FW | _ | 1 ± 0.44 | ND | ND |

| Rampal | MS | HS | + | 4 ± 1.63 | 8 ± 1.82 | 4 |

| Alipur | HS | MS | _ | 4 ± 1.25 | 5 ± 1.62 | 1 |

Notes: FW = Freshwater, LS- low saline, MS = medium saline, HS = high saline, ND = due to no river connection; (−) = Salinity decreasing, (+) = Salinity increasing, (∼) = almost same or little change.

3.2. Salinity condition in ICZ surrounding villages and causes of change

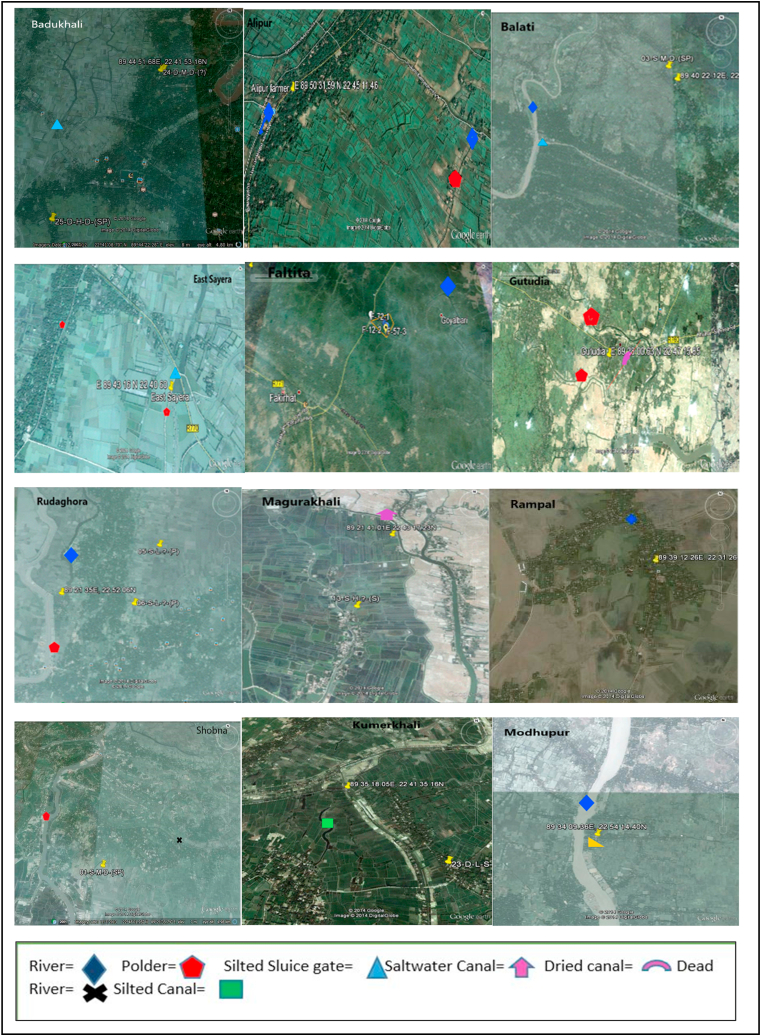

Six villages including Shobna, Gutudia, Balati, Faltita, Badukhali, and East Sayera are located along the ICZ. Rudaghora, Modhupur, and Alipur are located immediately to the north and the Magurakhali, Kumerkhali, and Rampal are situated to the south. In Magurakhali, shrimp and prawn farmers perceived opposing trends; increasing and decreasing salinity, respectively, consistent with protection from saline surface waters afforded to rice/prawn farmers by a local embankment. Salinity trends in Rampal were heavily influenced by the continuous siltation of the Mongla channel river, in the short term at least amplifying the effect of monsoon fresh water intrusion (Fig. 2). Respondents further upstream (in villages closer to Bagerhat) also felt that siltation of the Mongla channel was the main reason for the recent decreasing salinity trend in riparian villages, including Faltita, Badukhali, and East Sayera. Consequently, culture of both shrimp and prawns occurred in these villages, effectively serving as a biomarker for the ICZ boundary. Then, individual adoption was affected by (i) minute variations in local salinity and farmers' access to these water resources, (ii) capacity to pay for various capital expenses, and (iii) risk-taking attitudes toward the culture possibilities. Farmers from Balati, Gutudia, and Rampal began using ground water for farming purposes in 2010, making up about 62% of those polled. Households from Alipur and Kumerkhali remained more reliant on monsoon water (>3000 households; Table 2). Groundwater aquifers ranging from 30 to 82 m depth supply moderately brackish water (>4 ppt) [56] suitable for shrimp production further decoupling farmers from surface water conditions. Farmers advised prawn, finfish, and some dyke crops could also be grown using such ground water. A small number of farmers in Shobna (5%) and Rudaghora (3%) adjacent to a highly silted canal (Fig. 2), still canal water during the dry season, to culture juvenile shrimp from the post-larvae (PL) stage.

Fig. 2.

Localized issues impacting salinity and water sources of ICZ villages in south-west coastal Bangladesh (source-Google map).

Table 2.

Trend of salinity extrusion in the gher of southwest coastal Bangladesh during the peak salinity season between 2010 and 2014 and their potential causes.

| Village | Number of farming households | Perceived salinity changes over four years (ppt) | Water source for farming in 2010 | Water source for farming in 2014 | Causes of change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Villages in landwards of ICZ | Rhudaghora | 350 | Slight decrease: 5-4 | RW | R, GW | Polder, silting river |

| Modhupur | 600 | No change: almost 6 around fours years | RW | GW | Silting sluice gate, diversification | |

| Alipur | 500 | No change or little decrease:1-0 | West saline RW, east fresh RW | MW, minimal west saline RW, mainly east fresh RW | Silting saline river and sluice gate | |

| Villages in line of ICZ | Balati | 350 | Slight decrease: almost 7 around 4 years | RW and MW | RW and MW | River silting, silting sluice gate |

| Gutudia | 150 | Slight decrease: almost 4 around 4 years | GW | GW | Saline source river completely dead | |

| Shobna | 1000 | Large decrease: 15-5 | RW, MW | MW, GW, AS | Silting river, diversification | |

| Faltita | 2000 | Large decrease: 12-2 | RW | RW, AS | Silting river | |

| Badukhali | 800 | Large decrease: 12 to 2 | RW | RW, GW | Silting sluice gate, diversification | |

| East Sayera | 600 | Slight decrease:0.5 to 1 | RW | GW | Polder, silting sluice gate, diversification | |

| Villages seawards of ICZ | Kumerkhali | 360 | No change: almost 0.5 around 4 years | RW | MW, GW | Polder, silting sluice gate, Silting saline river, diversification |

| Rampal | 1000 | No change: almost 3 around 4 years/Decreasing (Abrupt increasing and decreasing. Now decreasing) | Fresh – MW, Salt - RW | Fresh – MW, Salt - RW | siltation of Mongla river leading back to Pashur reducing salinity | |

| Magurakhali | 1500 | Increased: 10–16 in saline side, Decrease to 0 in other side of polder | RW | RW in saline side, GW in fresh = water side | polder makes salinity zoning, now decreasing over years of flushing |

RW = River Water, MW = Monsoon Water, GW = Ground Water, AS = Artificial Salt.

Results indicated that respondents were switching their water use from the river to underground and/or monsoon water sources. The siltation problem of river/canal, disfunctioning of sluice gates and to avoid coastal salinity intrusion in view to adopting their preferred diversification are the causes found behind the shifting.

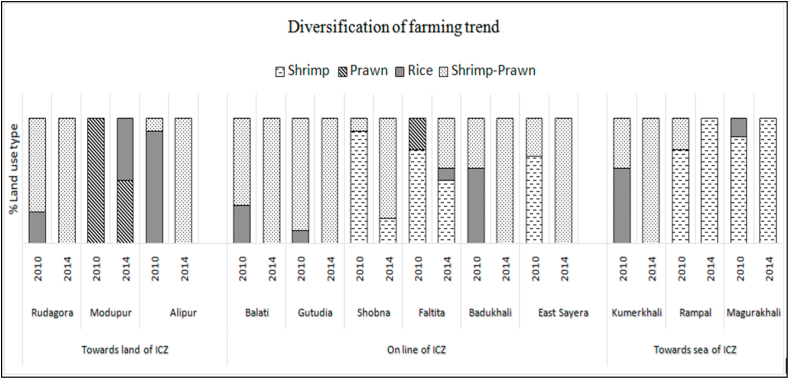

3.3. Diversification of farming system in ICZ surrounding villages

During the late 1970s, farming systems in the SW region have been transformed from terrestrial-crop-based systems to semi/aquatic gher-based aquaculture systems, as this region is located next to the coastal zone. Gher based aquaculture system has been modified later given the adaptation of salinity trends, reducing shrimp and prawn farming risk and improving market access. Such changes in the farming practices have also been observed in all studied villages during the experimental period (Fig. 3). Some NGOs (non-governmental organizations) have also persuaded coastal farmers to diversify their farming practices because doing so lessens their vulnerability to unforeseen events like viral diseases and/or water quality criteria deterioration.

Fig. 3.

Diversification of farming pattern in the study villages between 2010 and 2014.

Results also indicated that farmers from Shobna village, located at the ICZ line, changed their aquaculture crops over time. For example, in 2010, these villagers had produced only shrimp (90%gher in number) and/or a combination of shrimp and prawn items (10%). But in 2014, they shifted their production trend by producing more on integrated shrimp-prawn items (combined, 80%) and/or shrimp (20%). In Badukhali, 60% and 40% of the farmers grew rice and shrimp/prawn in 2010, respectively, but in 2014, they completely switched their production trend by producing both shrimp and prawn (100%). Changes have been observed in villages towards the land and sea of ICZ. In Modhupur, all respondents ultimately adopted prawn farming, reported in 2010. However, in 2014, they switched to 50% farm prawn and 50% rice farming. All the reported farmers in Magurakhali and Rampal villages have adopted shrimp farming (100%), whereas the farmers in Kumerkhali have adopted both shrimp and prawn farming. Such adoption in Magurakhali, Rampal, and Kumerkhali is due to the declining salinity trend resulting from the siltation occurring at their nearby major canals.

3.4. Phase-2: changes in yields of seafood, finfish and dyke crops

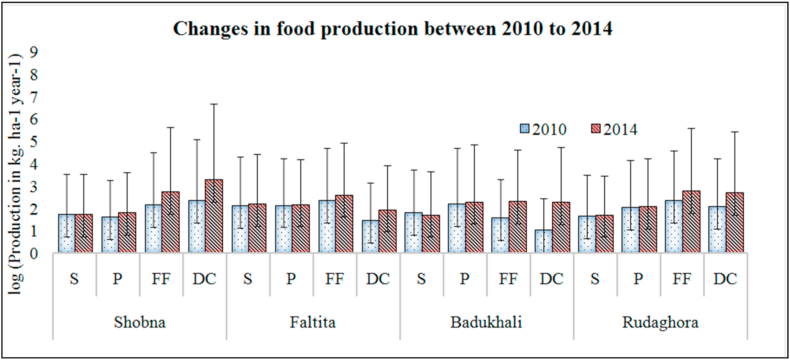

3.4.1. Seafood production trend

Over the last four years, the surveyed farmers have contributed mainly to seafood production in this region. However, it varies across the villages examined. In Shobna, most shrimp farmers have indicated a fluctuating trend in their seafood production. For example, in Shobna, approximately 43% of shrimp farmers have witnessed a decreasing trend in their production, whereas 38% found an increasing trend, and the rest sustained their production. Similar instances were observed for the surveyed farmers in the Badukhali village over the last four years. Moreover, the highest prawn production was observed in this Badukhali village (mean ± SD, 203 ± 339 kg/household). The examined villages also indicate the deviation between the better and worse-off. Among the worse off, 19% of the farmers had no production, reported in 2010 in Badukhali, which stated that they were likely to be the beginners in aquaculture. Among the studied villages, the adoption of shrimp farming significantly impacts the socioeconomic status between the better-off and the poor classes. Such improved socioeconomic status has been reported in Faltita village, where 57% of the examined farmers' socioeconomic status has improved their wealth after receiving increased production from shrimp. The opposite scenario was reported for the surveyed farmers of Rudaghora and Shobna as their socioeconomic status declined after witnessing a decreasing trend of shrimp production. However, a satisfactory prawn yield was reported with an increasing pattern in all villages examined (Fig. 4). For example, in Shobna, 63% of the sampled farmers have increased their prawn production and thereafter, sustained respectively. Comparatively, prawn production has increased (60%) over the last four years compared to shrimp yield (38%). The average prawn production in Shobna, Faltita, Badukhali, and Rudaghora was reported to be 68, 157, 203, and 154 kg/household, reported in 2014, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Changes in seafood production, fresh water related finfish and dyke crop production in the study villages between 2010 and 2014(S= Shrimp, P= Prawn, FF= Finfish, and DC = Dyke crop).

Prawn production was dominated by the better-off classes in Badukhali, with 80% of the total production controlled by wealthy farmers, reported in both 2010 and 2014. Similar to Badukhali, prawn production is the highest amongst the better-off farmers in Faltita. However, worse-off farmers still have a reasonable share in the market considered as per unit area in Faltita. In Rudaghora, better-off groups dominated the overall production, but worse-off people are not negligible, like Badukhali and Faltita. Approximately 35% of farmers decreased their prawn production while 15% increased production in the villages examined. Such an outcome is due to the preference for finfish production over the prawn. Because prawn farming requires more capital and continuous monitoring to prevent sudden viral disease outbreaks.

3.4.2. Finfish and dyke crops

Since 2010, freshwater production of fin fish and dyke crops has doubled or more in the studied villages (Fig. 4). In Shobna, 82% of the sampled farmers have increased their freshwater fish and dyke crop production. In Badukhali, the poorer classes have significantly dropped their farm prawn production and emphasized finfish production more than their counterparts of the affluent classes. Overall, 90% of the wealthier classes in Badukhali have improved their production. In Faltita, finfish production increases across all wealth classes. Approximately 84% of farmers in Faltita have doubled their production since 2010. Finfish production has exceeded the seafood yield in Rudaghora for the last four years. Among the four villages examined, the highest amount of finfish has reported in Shobna in 2014 (553Kg/household; Fig. 4). All types of carps, mainly Indian major carp-rohu (Labeo rohita), catla (Gibelion catla), silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix), grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), mrigal (Cirrhinus cirrhosus), common carp (Cyprinous carpio), and tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus/Oreochromis niloticus), Japanese punti (Puntius sarana), tengra (Mystus vittatus/Mystus blekeri), green back mullet (Chelon subviridis) are commonly cultured in these examined villages. In Shobna, the percentage of farmers producing dyke crops increased from 26% in 2010 to 78% in 2014. According to Badukhali, dyke crops have been widely accepted, especially by the richest classes. In contrast, Faltita village stated that dyke crop production did not provide some farmers with a suitable return, with the greatest harvest being 300 kg per household. Both Shobna and Badukhali are produced at over 800 Kg per family. In Rudaghora, 45% of those surveyed stated that no dyke crops were produced in 2010. Farmers in the studied villages cultivate mainly fresh water and low salinity tolerant vegetables, including ladies-finger (Abelmoschus esculentus), brinjal (Solanum melongena), bitter melon (Momordica charantia), pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima), chili (Capsicum species/annum), bottle gourd (Lagenariasi siceraria), radish (Raphanus sativus), cabbage (Brassica oleracea), basil (Basella alba), tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum), ribbed gourd (Luffa acutagula), yardlong bean (Vigna sesquipedalis), and green banana (Musa spp).

3.5. Changes in income and contribution of aquaculture

Income generation between 2010 and 2014 is shown in Table 3. Income generated through aquaculture shows a dramatic increase between the wealthier classes. Even the poorer households have raised their income through aquaculture, albeit not as well as the better-off prosperous farmers. The main reason for the divide is the capital required to invest in greater production. Worse-off farmers are less willing to risk the option of a loan whilst also engaged in other work such as day labor. After switching to aquaculture farming, 76% of the Shobna farmers in the sample saw an improvement in their income. In comparison, the rest of them could not improve their income partly due to their combined age and/or health factors. Average income varied between socioeconomic categories and villages (p < 0.05). The average income of the better-off classes was significantly higher than worse-off classes, reported both in 2010 and 2014 (p < 0 0.05). However, there was no significant difference in terms of income between the poor (W3) and ultra-poor group (W4), reported both the year (p > 0.05). Approximately 70% of the farmers in Badukhali has increased their income, while the remaining indicated a decreasing income trend due to their retirement from other job or business they were continued with aquaculture. Faltita shows an apparent deviation between income and well-being classes. Although income increased through all socioeconomic groups, farmers in classes W1 and W2 have an average 40% increase in monthly income compared to 30% with the worse-off classes. Similarly, the better-off groups have an average 60% increase in their aquaculture-related income compared to 38% seen in the worse-off, although these increases remain relatively small. Like other villages, Rudaghora farmers increase their overall income over the four years. Across all socioeconomic groups, 75% increased their income, while only 5% decreased their income. However, surveyed participants under the worse-off group did not witness any aquaculture-related income reduction, while 25% of better-off farmers had experienced an income reduction under the above-noted category. The reasons behind such a declining trend were the PL (post larvae) mortality, viral loss associated with shrimp and prawn farming, age factor, and/or health status of farmers.

Table 3.

Contribution of aquaculture income on total income in inter-saline convergence zone (ICZ) in south-west coastal region of Bangladesh.

| Village name | Socio-economic status | Average monthly income (BDT) |

Aquaculture contribution (BDT) |

% Aquaculture contribution |

Changes from 2010 to 2014 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2014 | 2010 | 2014 | 2010 | 2014 | |||

| Shobna | W1 | 27,000 (4242)a | 38,500 (16,263)a | 18,500 (9192)a | 19,000 (8485)a | 68.5 | 49.4 | −19.1 |

| W2 | 12,000 (6403)a | 19,000 (7334)a | 8318 (3822)a | 12,591 (6506)b | 69.3 | 66.3 | −3 | |

| W3 | 4500 (2798)b | 6600 (2836)b | 1950 (1571)b | 3350 (2333)b | 43.3 | 50.8 | +7.4 | |

| W4 | 4000 (5656)b | 5500 (3535)b | 1000 (1414)b | 1500 (707)b | 25 | 27.3 | +2.3 | |

| Badukhali | W1 | 23,333 (15,275)a | 51,667 (59,651)a | 19,000 (16,822)a | 45,667 (64,392)a | 81.4 | 88.4 | +7 |

| W2 | 17,375 (7130)a | 22,125 (6791)a | 11,000 (6524)a | 14,625 (7029)b | 63.3 | 66.1 | +2.8 | |

| W3 | 8600 (5581)b | 9900 (3478)b | 3450 (3989)b | 5500 (2223)b | 40.1 | 55.6 | +15.4 | |

| W4 | 4500 (500)b | 5000 (1000)b | 1200 (200)b | 2000 (0)b | 26.7 | 40 | +13.3 | |

| Faltita | W1 | 25,000 (5000)a | 36,667 (11,547)a | 14,000 (1732)a | 15,000 (0)a | 56 | 40.9 | −15.1 |

| W2 | 11,714 (4270)a | 15,714 (3352)a | 10,286 (4644)a | 11,857 (3387)b | 87.8 | 75.5 | −12.4 | |

| W3 | 5111 (3443)b | 7667 (5522)b | 3600 (2624)b | 5711 (3556)b | 70.4 | 74.5 | +4.1 | |

| W4 | 5000 (1000)b | 5000 (500)b | 1000 (1000)b | 1700 (700)b | 20 | 34 | +14 | |

| Rudaghora | W1 | 16,000 (5656)a | 19,500 (707)a | 14,500 (6363)a | 10,500 (2121)a | 90.6 | 53.8 | −36.8 |

| W2 | 9500 (5212)a | 14,300 (11,195)a | 5550 (5519)a | 9900 (10,743)b | 58.4 | 69.2 | +10.8 | |

| W3 | 4375 (1973)b | 8000 (2449)b | 2000 (1825)b | 3500 (2516)b | 45.7 | 43.8 | −1.9 | |

| W4 | 3875 (853)b | 4375 (1108)b | 800 (355)b | 1000 (424)b | 20.6 | 22.9 | +2.2 | |

Figures in the parentheses are standard deviation. Mean values followed by different superscript letters in 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th row indicate significantly different (p < 0.05) based on ANOVA.

(1 BDT = 0.012 USD; Source: Bangladesh Bank).

Though aquaculture-related income increased across the well-being classes in four villages, overall income decreased mainly in better-off groups in Shobna, Faltita, and Rudaghora. This is primarily due to the transition from high currency-earning shrimp farming to low priced freshwater fish farming. Besides these, surveyed villagers are engaged in other professions such as fruit selling business, teaching, and others.

3.6. Changes in seafood farming land in the examined four villages

Significant increases in farming land have been observed across well-being classes in four villages examined (Table 4). In Shobna, 57% of the better-off farmers have increased their farming land by leasing from others or transforming their land from rice to shrimp–prawn and/or finfish farming, reported during the study period. Rich people are significantly higher among all groups than the other groups examined (p < 0.05). Ultra-poor farmers from worse-off groups still possess a tiny farming land but trying to involve more in farming activities by taking leases from others. Moreover, no significant difference was reported between the ultra-poor and poor groups for the examined farming land (p > 0.05). In Badukhali, wealthy and medium classes people had increased 40% of their farming land area, while only 5% for the poor had made such achievement. Among all socioeconomic rank examined a positive change was reported in Faltita and Rudaghora. The better-off classes in Faltita and Rudaghora have an average farming land of 405 decimal (±100.58) and 225 decimal (±35.4), respectively (2014). The average area increased by 17% and 34% in Faltita and Rudaghora. Among the four villages, ultra-poor farmers from Faltita showed a significant change by having an increasing trend of their land area (18%). This scenario of Faltita suggested that declining salinity over four years helped the ultra-poor farmer engage in more farming activities.

Table 4.

Farming land-use change (decimal) of respondent’s households in the study villages between 2010 and 2014.

| Village Name | Socio-economic status | Average land (decimal) |

% of changes (±) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2014 | |||

| Shobna | W1 | 200 (142.1)a | 225 (142.12)a | +12.5 |

| W2 | 122 (90.91)b | 144 (70.18)b | +18 | |

| W3 | 113.6 (87.7)b | 108.9 (54.2)b | −4.1 | |

| W4 | 11 (7.07)a | 12 (8.49)a | +9.1 | |

| Badukhali | W1 | 700 (360.6)a | 773.3 (410)a | +10.5 |

| W2 | 307 (354.7)b | 307 (339.2)b | 0 | |

| W3 | 180 (216.5)b | 132 (77)b | −26.7 | |

| W4 | 10 (2.83)a | 10 (2.83)a | 0 | |

| Faltita | W1 | 346.6 (120.1)a | 405 (100.5)a | +16.8 |

| W2 | 156 (63.2)b | 189 (73.4)b | +21.2 | |

| W3 | 94 (67.9)b | 114 (48.8)b | +21.2 | |

| W4 | 17 (9.8)a | 20 (11.3)a | +17.6 | |

| Rudaghora | W1 | 152 (67.9)a | 225 (35.4)a | +48 |

| W2 | 177 (59.6)b | 198 (73.1)b | +11.9 | |

| W3 | 110 (28.6)b | 100 (70.7)b | −9.1 | |

| W4 | 25 (23.9)a | 22 (20.8)a | −12 | |

*Different superscripts letter in 3rd and 5th rows indicate significantly different (p < 0.05) based on ANOVA.

3.7. Land use pattern and lease-in cost trend

Leasing-in costs required for farmland is a good predictor of increasing competition within the market. In 2014, 34% of the household-owned their farming land outright while the rest leased in land from the landlord. Price hike has also appeared while leasing the land between 2010 and 2014, reported by all socioeconomic groups. In 2010, 49% of sample farmers in Shobna leased-in land from others (Table 5). More villagers may attempt to participate in farming as a result of landlords raising leasing prices. Within all wealth classes, the average leased-in cost was 23,114.26 ± 6838 BDT in 2010, whereas it was average 41,654 ± 12,375 BDT per ha in 2014. In Badukhali, with 47% of the sample group owning their land outright, the remaining 53% experienced a considerable price rise compared to Shobna. In Faltita, only 30% of respondents leased-in the land, and costs were varied. In Faltita, the average lease-in cost was 20,900 ± 7802 BDT, reported in 2010 relative to 25,650 ± 10,429 BDT per ha in 2014. In Rudaghora, many farmers lease-in land from landowners, and the tendency to lease land within worse-off increases. In Rudaghora, 66% of farmers from all socioeconomic status leased - in land from others, reported in 2014. It shows that present salinity-related diversity is more profitable and superior to single crops. The cost of leasing was higher for all farmers, including Shobna and Faltita.

Table 5.

Changes in farmers leased-in land by percentage and lease-in cost in the study villages between 2010 and 2014.

| Villages | Farmers (%) |

Changes of farmers number (%) | Average leased-in cost (BDT)/ha |

Increment rate per ha over four years period (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leased-in land in 2010 | Leased-in land in 2014 | |||||

| 2010 | 2014 | |||||

| Shobna | 49 | 66 | +26% | 23114.26 | 41,654 | 80.20 |

| Badukhali | 40 | 53 | +25% | 17812.5 | 25,650 | 44 |

| Faltita | 20 | 30 | +33.3% | 20,900 | 25,650 | 22.72 |

| Rudaghora | 31 | 66 | +53% | 22114.8 | 34254.24 | 54.89 |

3.8. Adaptation strategies to salinity changes of ICZ villages

The majority of the questioned farmers in all of the villages under study rely on conventional shrimp farming as their main source of income. The farmers generally had good reactions to the salinity changes because it increased their income through diversification. They diversify their farming by growing dyke crops, freshwater fish, and prawns, which increased demand for land leases in the survey villages. The price of the land that was leased in as a result has gone up. With the changing climate variabilities situation, the farmer has, however, been adopted various strategies to cope with. The major adaptation approaches involved water use change, changing the land use and farming techniques, diversification through prawn, finfish, and dyke crops along with traditional shrimp, more leased-in land, and emerging new techniques such as the use of table salt (Appendices Table A2). These adaptation mechanisms ensured unwavering household exposure to risk and seasonality and provided a regular cash flow for running their business smoothly. Farmer adopts their farming system according to salinity level, and in many cases, they have been implementing their technique like the use of crushed or unrefined salt for their farming. For example, in the village Shobna, the examined farmer found decreasing salinity trend in the last four years and currently using groundwater (95%) for farming practices supplemented with monsoon water. Again, the farmer noted that underground water salinity causes no harm to prawn, finfish, and dyke crops, so they are using it. A small portion (5%) uses crushed salt with the available canal water for their shrimp PL growth. The same trend also followed in the village Faltita. Here the farmers extensively use the market salt mix with water to increase salinity to sustain traditional shrimp farming. Among the 75% of households surveyed in Faltita had adopted this technique. In Shobna, some farmers (18%) also used market salt in their culture pond to grow shrimp PL to the juvenile stage. Farmers in Shobna and Faltita utilize the amount of salt based on their prior experience rather than a scientific assessment. Although the amount of artificial salt varies, the average was roughly 1658 kg per hectare. Household capacity, household location, and salinity are essential in different adaptation options. Based on the salinity level, households of different groups acted differently to deal with the impact.

However, the diversification of farming practice remains the most preferred adaptation measure as it enables the farmers to create opportunities for sustaining their livelihoods and ensuring food security. Surveyed farmers from Shobna have used the highest percentage (89%) of diversification options; they still have a moderate saline water source but use a low saline underground water for diversification (Appendices Table A2). Additionally, Shobna has had the greatest land use change, primarily the conversion of rice fields into aquaculture ponds. Additionally, households are more likely to lease-in land because the current trend in salinity decline offers the opportunity to grow a variety of crops. During the survey, some evidence of the current salinity situation was discovered. The majority of respondents concurred with the favorable site of diversification of crops.

4. Discussion

4.1. Salinity condition study in southwest region

In global deltaic coastal zones salinity is one of the significant drivers of land-use change and the farming system [[28], [29], [30],57]. The SW region of Bangladesh lying on the one of the most active coastal deltaic zone are subjected to changing salinity and associated farming practices [4,14,15,25]. Contrary to another study in a similar geographical location [6], salinity in this particular region is decreasing due to siltation of local and regional rivers and canals limiting surface water access. Studies in Vietnamies coastal delta found many salinity-control structures such as dykes, sluicegates and irrigation infrastructures limit the salinity-affected areas and improve freshwater supplies and increased freshwater production from both agriculture and aquaculture [30,57,58]. Sensory testing for determining salinity is a well-established method. Narahari (2012) used such sensory tests to determine the salinity level in integrated poultry and fish project in India [59]. In general, the southern coastal people of Bangladesh typically perceive drinking water salinity by taste [53]. We have used such a method in this study to evaluate the farmer’s perception of salinity. The timing of the research allowed for spot test measurements to be taken using a refractometer. Furthermore, the salinity measurements corroborate the qualitative information provided by the key informants on salinity trends and found an almost accurate results. According to the ‘National Water Management Plan’, the ‘Water Resources Planning Organization in Bangladesh’ has categorized the surface water salinity into the following groups: (i) <1 dS/m: slightly saline; (ii) 1–5 dS/m: slightly to moderately saline; (iii) 5–10 dS/m: moderately to highly saline; and (iv) > 10 dS/m: highly saline. (ECw = ¼ (TDS/640) × 1000, where ECw is the electrical conductivity of the water (dS/m), and TDS is the total dissolved solids (ppt) [13]. In our study, we made four group of salt water solutions −0.5 ppt, 5 ppt, 10 ppt and 15 ppt, confirmed with the refractometer. Participants ranked the solutions in order of salinity, low to high as freshwater, low saline, medium saline and high saline which is almost similar to ‘National Water Management plan.’ and saline divide got by Refs. [56,60]. Even though multiple authors reported increasing salinization in the SW region, in our case study we have found a decreasing salinity in SW region due to siltation of local and regional rivers and canals limiting surface water access [25,51]. Moreover, the saline-water-logged area in the studied Kumerkhali village has been gradually decreasing due to the monsoon water run-off, making the area fresher, while siltation or embankment prevents saline water intrusion other areas. Paul et al. showed that the total waterlogged area in this SW basin had been decreased by 4395.35 ha (4.36%), and the agricultural land area has increased to 4766.52 ha (4.73%) from 2000 to 2004 as the sediment inflow and deposition raised the river bed [61]. People use it for agricultural production. They studied through remote sensing and GIS (geographic information system) mapping in HariTeka river basin, the distributaries of the Bhairab river in the SW coastal zone of Bangladesh [61]. They also found that the river is now disconnecting with the Bhairab river due to sedimentation limiting the natural water course. Taskov indicates a major silted river in this area [52]. The Mongla river is the first major branch of the Passur, carrying saline water further inland to Badukhali and Faltita. Both siltation and sedimentation continuously increase the riverbed height and discharge a lesser amount of water. This localized effect significantly impacts the villages almost 100 km northwards from the coastline [62].

4.2. Current salinity trend and diversification of farming pattern

A study in Thailand by Flaherty et al. noted that although shrimp production can improve the livelihood of a population, diversification is a much more favored practice [56]. Crop diversification is a valuable means to increase output by increasing food production, economic returns, self-sufficiency, resource use optimization, and higher land utilization efficiency [56,63]. Such an option can also spur sustainable growth in the rural sector by eradicating poverty and increasing job opportunities [[64], [65], [66]]. Hence, Mahmud et al. addressed the diversification requirement in Bangladesh as it could influence the growth and sustainability of agricultural production [67]. Moreover, diversification with crops-fish-horticulture combined can cause the productivity of nearly three times and profitability gains of almost four times higher than the farmers' adopting traditional single rice crop practice [68]. With decreasing salinity our study found that the freshwater production from fin fish and dyke crops has doubled or more in only four-year periods. Diversification is also adaptive management for environmental change and climate change [[69], [70], [71]]. With traditional shrimp farming, farmers in the study areas diversified their production, combining freshwater agriculture and aquaculture to combat extreme climatic issues, mainly salinity. Oleke et al. found that land ownership, land size, income from crops, non-farm income, and family size were the main factors that could influence the farmer’s decision to diversify crops [72]. In the study, income generated through diversification of agriculture and aquaculture shows a dramatic increase among the wealthier classes. Poorer classes have increased their aquaculture income, however not as successfully as the richer farmers. The main reason for the divide is the capital required to invest in greater production. Poorer people are less willing to risk the option of a loan whilst also engaged in other work such as day labor. Although shrimp is a much more favored product due to its economic benefits and low input costs, aquaculture income in Faltita has generally struggled to improve over the last four years, whereas Badukhali has seen greater income increases through moving towards the production of more freshwater species.

Barghouti et al. noted six points that influence the diversification such as (1) feasibility, (2) policy, (3) infrastructure and markets, (4) research, extension, and training, (5) private sector and supply chains, and (6) natural resources [65]. The findings from this study identified the integration of vegetable production alongside aquaculture has been shown to improve the livelihoods and in Shobna and Badukhali, interestingly, in most cases crop production has tripled since 2010, suggesting that salinity levels are decreasing. Market demand or access to market may be a cause but Shobna with limited market access produces vast dyke crops and increased fin fish production across the villages suggests that salinity decreases are contributing in part to the increased production. Salinity is the major reason behind the use of low land and adopts cropping intensity in the coastal region of Bangladesh [73]. Current diversification with vast freshwater production can support the declining trend of salinity. BRAC reported that farmers diversify their farming by using tidal non-saline river water and/or storing non-saline water, referred to as block approach (a contiguous area of farmers' land) [68,74,75]. Such a similar block trend was observed in the studied villages of Kumerkhali, Rudaghoras, and Magurakhali in view to diversifying their production. In Magurakhali, farmers with large land produce both saline and freshwater species by creating saline and freshwater blocks. Surveyed farmers from the experimental villages prefer to adopt crop diversification rather than single production as diversification improves their livelihood by recovering quickly from any unexpected disaster and/or sudden loss. Several studies found that ‘Integrated Agriculture with Aquaculture’ (IAA) increases the farm’s productivity, income, and sustainability [76,77]. Farmers recently introduced freshwater farming such as prawns and vegetables as a coping strategy to salinity changes [50,78]. The current study found that diversification is a technique the farmer uses to ensure their income and livelihood stability. Hence, they prefer to block the saline water intrusion inside their gher, even though they have access.

4.3. Seafood production trend

As three villages lies in line of ICZ and one landward of ICZ, farmers can engage in shrimp and prawn farming. The difference in production trends with doubled fin fish production and tripled dyke crop production, further highlights the necessity to examine each localized area individually as farmers make livelihood choices based on their localized environment [17]. With decreasing salinity, farmers are getting better prawn production as they can grow in low salinity [[79], [80], [81]]. The increase in shrimp production in Rudaghora and Faltita is mainly due to increased land area and adaptation processes such as using artificial salt. During the 1980’s, in land farming of Penaeus monodon within Thailand began to take form as farmers exploited the durability of the species in low saline water [82]. Transferring coastal PL to this environment required a transition period, where salinity was decreased over a number of days to allow for acclimatization. In contrast, Badukhali farmers have reported a low shrimp production compared to 2010 as they more area for freshwater farming. The study finding is very similar to some contemporary research in the same geographic area where farmers are farming more prawn than shrimp to cope with the scarcity of salinity, mass mortality of shrimp due to viral attack [3,78,83].

4.4. Finfish and dyke crop production

The integration of vegetable production alongside aquaculture has been shown to improve the livelihoods of those who practice such methods [84]. Toufique and Gregory stated that wealthier farmers often benefited more than the poor regarding fish production, citing land dominance as the main reason for this [85]. It is contrary to this study’s findings, where poorer households could still produce the same levels of finfish as the wealthier groups, even though the land sizes were vastly different [56,[86], [87], [88]]. This difference can be understood when comparing prawn and finfish production in Badukhali. Whereas prawn production is controlled mainly by the wealthier farmers, the opposite is true for whitefish production. The poorer farmers cited the lower risk factors associated with disease and loss of stock for prawn farming as the reason for the preference of finfish over prawn. Furthermore, the relative input costs are much lower in finfish production than prawn, generating higher income for the poor [62]. Solidarites International and Uttaran found the same by suggesting that farmers are now intensively monitoring the salinity of their land and producing more finfishes, prawn, and dyke crops [78]. All four villages showed increasing rates of finfish production; this could suggest salinity decreases, and farming techniques were driving the trends. Studies in coastal Vietnamies delta found similar result of higher fish and vegetables production with reduced salinity by salinity protective infrastructure [28,30,58]. Furthermore, a reduction in salinity can improve vegetable crops significantly [89]. The findings from this study identified significant increases in dyke crop production in Shobna and Badukhali; interestingly, in most cases, crop production has doubled or tripled since 2010, suggesting that salinity levels are decreasing. Alternatively, these rapid increases may be farmers' responses to a booming market, and with significant population increases, demand for vegetables is likely to increase [90,91]. A study in Asia access to markets is also considered by Ettienne, citing that good infrastructure often improves agricultural output, as farmers can sell more crops and improve their livelihood [91].

Though with limited access to markets, Shobna still produces a more significant amount of dyke crops than Faltita suggests that salinity decreases are contributing in part to the increased production. In truth, this study did not establish the true drivers of vegetable production but one can reasonably assume increase in production is a combination of salinity decreases and market demand.

4.5. Leased-in area and cost

With decreasing salinity, the option to diversify agriculture practices and improve income could indicate why farmers were experiencing price increases for land rent. The results show that prices were rising, observed between all wealth classes, with an overall rental cost variation. Although this could indicate increasing competition, the lease-in costs are based on a yearly figure. Therefore, it is uncertain whether lease costs have risen due to increased competition or farmers purchasing more land. Rent value rises are also likely to be attributed to several socioeconomic factors, including land quality. In Shobna and Badukhali, increased land competition resulted in increased rent, and the overall land size was being scaled down. As landlords realized the potential to increase their income, ghers were frequently being scaled down into smaller ‘pocket’ ghers [62].

This is contrary to a study by Niroula and Thaupa, who showed that other Asian countries were reducing the amount of smaller scale farms by intensifying production with larger companies, thus improving the productivity of the land [92]. Rahman showed that farmers are more willing to leased-in land when the land is fertile or more productive in order to increase their agricultural output [93]. This coincides with the findings from this study, where differences can be seen between Shobna and Faltita’s production. Qualitative analysis revealed that Faltita experiences less production from poor soil quality with high levels of iron content, evident through the orange color in the surface soil. Local farmers from all wealth classes acknowledged that the land quality was awful within the area due to historical salinity encroachment. As a result, only 30% of farmers leased-in land of the total sample group interviewed.

4.6. Adaptation mechanism

A study in Sub-Saharan Africa by Kassie et al. revealed that land productivity could significantly improve when crops are rotated [94]. The study findings support that diversification increase income and sustainability rather than a single harvest of shrimp, prawn, finfish or dyke crops. As the results show, income has increased in four study villages over the last four years. Findings were similar to that which has been found elsewhere in the literature, where the richer classes were able to improve their financial situation much more successfully than the marginalized poor [5]. This relates to the availability the richer classes have to taking more calculated risks, whereas the poor do not have the option to take increased risk as their lack of capital prevents increasing production [36,88]. As a result, diversifying livelihoods becomes difficult for the poor as they struggle to find alternative methods of income generation [95]. Aquaculture income does differ significantly between the villages. The primary reason for the differences in aquaculture income is the direct result of the adaptation strategies that each village has adopted. For example, Faltita is a village steeped in shrimp culture, and their efforts to continue producing shrimp have seen drastic measures are taken, such as the use of artificial salt. The quantity of artificial salt is varied however an average amount taken was 1658 kg/ha by the surveyed farmers. Although Flaherty et al. calculated 3048 kg/ha which is almost double, these results still show a large amount of salt being placed on a relatively small area of land [56]. In some cases, farmers did note that fewer dyke crops were prevalent in the areas where the salt was being applied than other areas, leading to environmental concerns and sustainability of production in Faltita in general and the possible cause for the reduction of salt use. In comparison, the farmers in Badukhali adapt to the environmental changes more naturally, pushing towards increased diversification with related freshwater aquaculture. Although shrimp is a much more popular product due to its economic benefits and low input costs, aquaculture income in Faltita has generally struggled to improve over the last four years. In contrast, Badukhali has seen more significant income increases by producing more freshwater species. Flaherty et al. noted that although shrimp production can improve the livelihood of a population, diversification is a much more favored practice [56]. Our current findings related to salinity-related adaptation strategies matches the results of Tri et al. and Nguyen et al. as they have also reported the same while researching in the coastal area of Vietnam [30,58]. They also added that changing farming practices was the best solution, and farming of more freshwater fish and diversification with dyke crops were introduced to the areas with low and moderate salinity levels. Shrimp or brackish water fish species were promoted as adaptation options for fish farmers considering changing [30,58]. The decreasing trend of salinity helped farmers to intensify their farming system by incorporating more fish species and dyke crop varieties. Such diversity enhances the profitability of the system and a good pathway of sustainable agri-aqua development.

5. Conclusions and future recommendations

Improved production of freshwater aquaculture and agriculture within four study villages is an indication that salinity is decreasing in the ICZ. Furthermore, although there are differences between the wealth groups, the range of adopted agricultural activities is increasing, which indicates that livelihoods are, to some degree, more stable and secure. While the villages adopt different mitigation strategies to cope with changes in salinity, all four variations appear to improve livelihoods. External actors like the silting and sedimentation of nearby canals, which may be the reasons why the salinity is dropping, are a problem rather than a solution. Access to surface water is becoming increasingly scarce and might, at some point, reach a critical level where continued aquaculture and agriculture may become impossible regardless of salinity changes. Regardless of the common salinity scenario, more studies should be done to determine the impacts of local intervention and ongoing river siltation and sedimentation on the hydrology and geography, especially to the salinity of SW Bangladesh. Sustainability of the current adaptation process to the future threat of salinity intrusion into empoldered area should be thoroughly revised. With different villages having individual physical characteristics, further research is required within each localized area of Bangladesh and wider field to create a clear picture of how climate change and future SLR will impact the rural people. In short, the use of macro-level concepts to address micro-level situations misrepresents the actual reality of the livelihood decisions which rural people face.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank all of the informants and farmers for their valuable time and cooperation in data collection. We would like to thank EU funded “International Strategic Partnership in Research and Education (INSPIRE)” project (SP_0015) for their financial contribution to the research.

Footnotes

SLR: According to World Bank (2010), greater saline intrusion progressively in low lying area is defined as SLR.

Appendix A.

Table A1.

Social well-being classification by the KI’s of the community based on household’s resources

| Social well-being | Resources | Specific attributes | General attributes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rich | Land | Owned large area of land (>0.91ha) | The rich were the local leaders, owner of big shops, fish depot, and gher. The rich hired permanent and seasonal labours more frequently than the other social groups. |

| Average monthly income (BDT) | >20,000 | ||

| House type | Building, semi-building, tin-shade | ||

| Occupation | Community leader, service holder | ||

| Aquatic farming | Farming in own land & leased-out | ||

| Medium | Land | Own medium area of land (>0.58ha) | Households involved in farming, business, and medium paid service. |

| Average monthly income (BDT) | 10,000–20,000 | ||

| House type | Semi-building, tin-shade, bamboo-tin | ||

| Occupation | Trader, school teacher, farmer | ||

| Aquatic farming | Farming in own land | ||

| Poor | Land | Own small area of land (>0.4ha) | The poor had a small piece of land for farming. Involved in small business within the village market including working in the fish depot and lower paid job. |

| Average monthly income (BDT) | 7000–10,000 | ||

| House type | Tin-shade, bamboo-tin, mud, straw-shade | ||

| Occupation | Farmer, shopkeeper | ||

| Aquatic farming | Own land as well as leased-in | ||

| Ultra-poor | Land | Own tiny area of land (>0.04 ha) | Possess only a small piece of land. They worked on the shrimp and prawn gher, rice land and in some extent sold their labour in the nearest district town. |

| Average monthly income (BDT) | 2000–8000 | ||

| House type | Tin-shade, bamboo-tin, mud, straw-shade | ||

| Occupation | Selling labour, rickshaw/van puller, work in shop | ||

| Aquatic farming | Tiny owned and leased in. |

Table A2.

Major adaptation strategies over the years (2010–2014) followed by the farmers in the study villages with the declining salinity

| Adaptation strategies | Households (%) |

Impact on Livelihood | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shobna | Badukhali | Faltita | Rudaghora | Mean | ||

| Water use change | 95 | 12 | 0 | 50 | 39.25 | |

| Use of unrefined table salt | 18 | 0 | 75 | 0 | 23.25 | Maximum utilization of resource Increased diversity and productivity Increased cash flow and economical security Increased women participation Nutritional security through diverse production Reduce risk from shrimp and prawn farming |

| Diversification through prawn, finfish and dyke crops along with traditional shrimp | 89 | 88 | 87 | 86 | 87.5 | |

| Overall land use change | 40 | 35 | 20 | 15 | 27.5 | |

References

- 1.Islam M.A., Hoque M.A., Ahmed K.M., Butler A.P. Impact of climate change and land use on groundwater salinization in southern Bangladesh: implications for other Asian deltas. Environ. Manag. 2019;64(5):640–649. doi: 10.1007/s00267-019-01220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oppenheimer M., Glavovic B.C., Hinkel J., van de Wal R., Magnan A.K., Abd-Elgawad A., et al. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. Portner H.O., Roberts D.C., Masson-Delmotte V., Zhai P., Tignor M., Poloczanska E., editors. 2019. Sea level rise and implicationsfor low-lying islands, coasts and communities; pp. 321–445. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahab Md, Nahid S., Ahmed N., Haque, Karim M.M. Current status and prospects of farming the giant river prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii (De Man) in Bangladesh. Aquacult. Res. 2019;43 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2012.03137.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Islam M.R. first ed. University Press; 2004. Where Land Meets the Sea: A Profile of the Coastal Zone of Bangladesh.https://www.worldcat.org/title/where-land-meets-the-sea-a-profile-of-the-coastal-zone-of-bangladesh/oclc/57236949 Dhaka, Bangladesh: Published for Program Development Office for Integrated Coastal Zone Management Plan (PDO-ICZMP), Water Resources Planning Organization (WARPO). Available at: Accessed on: 10/08/21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afroz T., Alam S. Sustainable shrimp farming in Bangladesh: a quest for an integrated coastal zone management. Ocean Coast Manag. 2013;71:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paul A.K., Roskaft E. Environmental degradation and loss of traditional agriculture as two causes of conflicts in shrimp farming in the southwestern coastal Bangladesh: present status and probable solutions. Ocean Coast Manag. 2013;85(Part A):19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2013.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahman M., Lund T., Bryceson I. Salinity impacts on agro-biodiversity in three coastal, rural villages of Bangladesh. Ocean Coast Manag. 2011;54:455–468. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Páez-Osuna F. The environmental impact of shrimp aquaculture: causes, effects, and mitigating alternatives. Environ. Manag. 2001;28(1):131–140. doi: 10.1007/s002670010212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray J.F. Sustainable ethical aquaculture trade (SEAT) 2010. http://seatglobal.eu/ Available at. Accessed on: 15/04/2014.

- 10.Gain A.K., Uddin M.N., Sana P. Impact of river salinity on fish diversity in the south-west coastal region of Bangladesh. Int. J. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2008;34(1):49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rashid M., Islam M.S. 2007. Adaptation to Climate Change for Sustainable Development of Agriculture, Bangladesh Country Paper for the 3rd Session of the Technical Committee of Asian and Pacific Center for Agricultural Engineering and Machinery (APCAEM), November 20-21, Beijing, China.http://un-csam.org/node/949 Available at: Accessed on: 12/08/21. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nobi N., Gupta A. Simulation of regional flow and salinity intrusion in an integrated stream‐aquifer system in coastal region: southwest region of Bangladesh. Ground Water. 1997;35:786–796. doi: 10.1111/J.1745-6584.1997.TB00147.X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke D., Williams S., Jahiruddin M., Parksa K., Salehinc M. The Royal Society of Chemistry; 2015. Projections of on-farm salinity in coastal Bangladesh. (Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dasgupta S.K., Farhana A., Khan Z.H., Choudhury S., Nishat A. In: River Salinity and Climate Change: Evidence from Coastal Bangladesh, in Asia and the World Economy - Actions on Climate Change by Asian Countries. Whalley John, Pan Jiahua., editors. World Scientific Press; 2015. pp. 205–242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dasgupta S., Moqbul H., Huq M., Wheeler D. Climate change and soil salinity: the case of coastal Bangladesh. Ambio. 2015;44(8):815–826. doi: 10.1007/s13280-015-0681-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.EGIS (Environment. Geographic Information Systems) vol. I. EGIS, Dhaka. Bangladesh Water Development Board; 2001. Environmental and Social Impact Assessment of Gorai River Restoration Project. Main Report. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brammer H. Bangladesh's dynamic coastal regions and sea-level rise. Clim, Risk Manag. 2014;1:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.crm.2013.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soil Resources Development Institute (SRDI) first ed. Ministry of Agriculture; Dhaka, Bangladesh: 2010. Saline Soils of Bangladesh.http://srdi.portal.gov.bd Available at: ›files›files›publications Accessed on: 12/08/21. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministry of water resources . 2013. Coastal embankment improvement project phase-1.https://www.wds.worldbank.org/.../RP1396v20Bangl0150201300Box374390 (Bangladesh Water Development. (Pdf)). Available at: Accessed on 11/07/2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haq A.H.M. 2000. Integrated Wetland System for Mitigation of the Salinzation of Southwest Region of Bangladesh.https://www.academia.edu/7497822/Integrated_wetland_system (paper Presented at the Eco Summit -2000, Ecological Engineering Society, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada). Available at: Accessed on : 06/08/21. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dewan C., Mukherji A., Buisson M.C. Evolution of water management in coastal Bangladesh: from temporary earthen embankments to depoliticized community-managed polders. Water Int. 2015;40(3):401–416. doi: 10.1080/02508060.2015.1025196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pukinskis I. 2015. The Polder Promise: Unleashing the Productive Potential in Southern Bangladesh. Colombo, Sri Lanka: CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE)https://wle.cgiar.org/news/polder-promise-unleashing-productive-potential-southern-bangladesh Available at: Accessed on: 12/08/21. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Islam K., Kibria Z. 2006. Unraveling KJDRP-ADB Financed Project of Mass Desturction in Southwest Coastal Region of Bangladesh. Khulna: Uttaran.https://uttaran.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/unravelingKJDRP.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adri N., Islam I. 2010. Water logging in keshabpur: A focus to the coping strategies of the people (Pdf)http://benjapan.org/iceab10/6.pdf (Proc. Of International Conference on Environmental Aspects of Bangladesh (ICEAB10), Japan). Available at: Accessed on 05/06/2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alamgir F. Environment and Sustainable Development (ESD). International institute of social studies; Hague, Netherlands: 2010. Contested Waters, Conflicting Livelihoods and Water Regimes in Bangladesh; p. 57.http://hdl.handle.net/2105/8633 Msc dissertation. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirza M.M.Q. Diversion of the Ganges water at Farakkaanf its effects on salinity in Bangladesh. Environ. Manag. 1998;22(5):711–722. doi: 10.1007/s002679900141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sattar S.A., Abedin M.Z. 2012. Options for coastal farmers of Bangladesh adapting to impacts of climate change. (International Conference on Environment, Agriculture and Food Sciences (ICEAFS'2012)). Phuket (Thailand) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tran D.D., Dang M.M., Du Duong B., Sea W., Thang V.T. Livelihood vulnerability and adaptability of coastal communities to extreme drought and salinity intrusion in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102183. 102183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen H.Q., Tran D.D., Luan P.D.M.H., Ho L.H., Loan V.T.K., Anh Ngoc P.T., Quang N.D., Wyatt A., Sea W. Socio-ecological resilience of mangrove-shrimp models under various threats exacerbated from salinity intrusion in coastal area of the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020;27(7):638–651. doi: 10.1080/13504509.2020.1731859. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen M.T., Renaud F.G., Sebesvari Z. Drivers of change and adaptation pathways of agricultural systems facing increased salinity intrusion in coastal areas of the Mekong and Red River deltas in Vietnam. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2019;92:331–348. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2018.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wijayanti W.P., Pratomo R.A. Adaptation of social-economic livelihoods in coastal community: the case of mangunharjo sub-district, Semarang city. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016;227:477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.06.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karim M., Sarwer R.H., Phillips M., Belton B. Profitability and adoption of improved shrimp farming technologies in the aquatic agricultural systems of southwestern Bangladesh. Aqua. 2014;428–429:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.02.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmed N. Linking prawn and shrimp farming towards a green economy in Bangladesh: confronting climate change. Ocean Coast Manag. 2013;75:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2013.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmed N., Demaine H., Muir J.F. Freshwater prawn farming in Bangladesh: history, present status and future prospects. Aquacult. Res. 2008;39(8):806–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2008.01931.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rutherford S. Bangladesh Aquaculture and Fisheries Resource Unit (BAFRU); Dhaka, Bangladesh: 1994. An Investigation of How Freshwater Prawn Cultivation Is Financed; p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belton B., Karim M., Thilsted S., Jahan K.M., Collis W., Phillips M. Review of aquaculture and fish consumption in Bangladesh. Stud. Rev. 2011;53:76. Penang: The WorldFish Center. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milstein A., Islam M.S., Wahab M.A., Kamal A.H.M., Dewan S. Characterization of water quality in shrimp ponds of different sizes and with different management regimes using multivariate statistical analysis. Aquacult. Int. 2005;13(6):501–551. doi: 10.5923/s.plant.201401.02. no. 4A, pp. 8–13, 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lam Y., Winch P.J., Nizame F.A., et al. Salinity and food security in southwest coastal Bangladesh: impacts on household food production and strategies for adaptation. Food Secur. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12571-021-01177-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shameem M.I.M., Salim M., Anthony S.K. Local perceptions of and adaptation to climate variability and change: the case of shrimp farming communities in the coastal region of Bangladesh. Climatic Change. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10584-015-1470-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rabbani G., Rahman A., Mainuddin K. Salinity-induced loss and damage to farming households in coastal Bangladesh. Int. J. Glob. Warming. 2013;5:400–415. doi: 10.1504/Ijgw.2013.057284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mondal M.K., Bhuiyan S.I., Franco D.T. Soil salinity reduction and prediction of salt dynamics in the coastal rice lands of Bangladesh. Agric. Water Manag. 2001;47(1):9–23. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3774(00)00098-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allison E., Ellis F. The livelihoods approach and management of small-scale Fisheries. Mar. Pol. 2001;25:377–388. doi: 10.1016/S0308-597X(01)00023-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rahman S., Barmon B.K., Ahmed N. Diversification economies and efficiencies in a ‘blue-green revolution’ combination: a case study of prawn-carp-rice farming in the ‘gher’ system in Bangladesh. Aquat. Int. 2010;19:665–682. doi: 10.1007/s10499-010-9382-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kulsum U., Timmermans J., Haasnoot M., Alam M.S. Why uncertainty in community livelihood adaptation is important for adaptive delta management : a case study in polders of Southwest Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2021;119:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2021.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahbubur S., Mori A. Dissemination and perception of adaptation co-benefits: insights from the coastal area of Bangladesh. World Dev. Perspect. 2020;20 doi: 10.1016/j.wdp.2020.100247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoque M.Z., Cui S., Lilai X., Islam I., Ali G., Tang J. Resilience of coastal communities to climate change in Bangladesh: research gaps and future directions. Watershed Ecol. Environ. 2019;1:42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.wsee.2019.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rakib M.A., Sasaki J., Pal S., Newaz A., Bhuiyan M.A.H. An investigation of coastal vulnerability and internal consistency of local perceptions under climate change risk in the southwest part of Bangladesh. J. Environ. Manag. 2019;231:419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salehin M., Chowdhury M.M., Clarke D., Mondal S., Nowreen S., Jahiruddin M., Haque A. In: Ecosystem Services for Well-Being in Deltas: Integrated Assessmentfor Policy Analysis. Nicholls R.J., Hutton C.W., Adger W.N., Hanson S.E., Rahman M.M., Salehin M., editors. Springer International Publishing; 2018. Mechanisms and drivers of soil salinity in coastal Bangladesh. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dasgupta S., Huq M., Mustafa G., Sobhan I., Wheeler D. The impact of aquatic salinization on fish habitats and poor communities in a changing climate : evidence from southwest coastal Bangladesh. Ecol. Econ. 2017;139:128–139. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deb A.K., Haque C.E. Livelihood diversification as a climate change coping strategy adopted by small-scale Fishers of Bangladesh. Clim. Change Manag. 2016:345–368. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahmuduzzaman Md, Ahmed Z.U., Nuruzzaman A.K.M., Ahmed F.R.S. Causes of salinity intrusion in coastal belt of Bangladesh. Int. J. Plant Res. 2014;4(4A):8–13. doi: 10.5923/s.plant.201401.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taskov D. University of Stirling; 2014. Qualitative Assessment of the Long-Term Impacts of the CARE GOLDA Project on Freshwater Prawn Farming Methods and Communities in Bagerhat District of Bangladesh; pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]