Abstract

Introduction and importance

Hydrocele canal of the nuck is one of the rarest clinical conditions encountered in adult females. It occurs as a result of a failure to obliterate the canal.

Case presentation

This case report details the surgical treatment in 25 – years old young female presented to the surgical clinic with a one-month history of right-sided painful palpable inguinolabial swelling. A large well-circumscribed cystic lesion with multiseptated, thin walls with no evident peritoneal cavity connectivity was seen on abdominal sonography and enhanced computerized tomography (CT) scan. The patient underwent surgical exploration, and the intraoperative findings revealed an encysted hydrocele distally at the external inguinal ring, with the canal of nuck partially obliterated in the midpoint and the proximal end communicating with a peritoneal cavity at the deep inguinal ring. The hydrocele and round ligament were excised, the canal of the nuck was high-ligatured, and the self-fixing prosthetic mesh was then utilized to repair the anatomical defect through the right inguinal skin creases approach. The patient had a smooth post-operative recovery and was discharged the next day with outpatient surveillance. The patient rested asymptomatic and experienced no recurrence three months after surgery.

Clinical discussion

Female hydrocele, often called “hydrocele canal of nuck,” is a rare developmental abnormality that typically presents later in life, and the condition is poorly understood among surgeons due to the lack of information on this clinical entity in surgical and gynecological textbooks, as well as the rarity of the disorder itself, both of these factors contribute to misdiagnosing as an irreducible inguinal hernia or a femoral hernia is possible in practice.

Conclusion

Hydrocele ultrasound-guided aspiration has no place in surgical practice. The surgical exploration approach is the only practical and standard therapy.

Keywords: Cyst, Canal of nuck, Hydrocele, Encysted, Female, Surgery, Aspiration

Abbreviations: MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging

Highlights

-

•

A unique differential etiology of inguinolabial cystic mass

-

•

Rarely seen in clinical practice that requires a multidisciplinary team

-

•

Intraoperative diagnosis

-

•

No role of ultrasound-guided aspiration of hydrocele in surgical practice

1. Introduction and importance

Female hydrocele is an embryonic developmental malformation. The canal of nuck was named after the anatomist Anton Nuck when he described the first case of the patent process vaginalis of the inguinal canal in a female in 1691. The condition has been described in medical literature by various names. The exact pathogenies are due to incomplete closure of the peritoneum fold during embryogenesis's eight months to the first year of a female's infancy life; the peritoneum fold descends the round ligament of the uterus into the inguinal canal to the labia majors. Therefore, the patency of process vaginalasis “diverticulum of Nuck” consequently increases the chance of developing various pathology during childhood and adulthood, respectively [1], [2]. The work has been reported in line with the SCARE 2020 criteria [3].

2. Case presentation

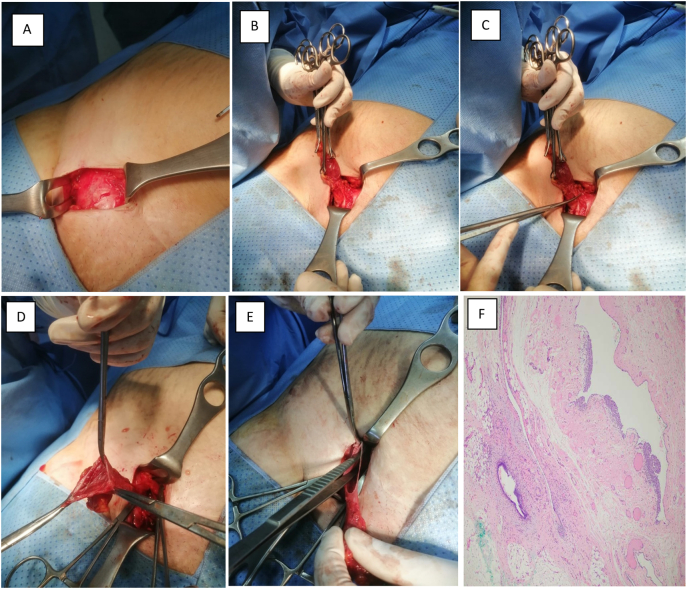

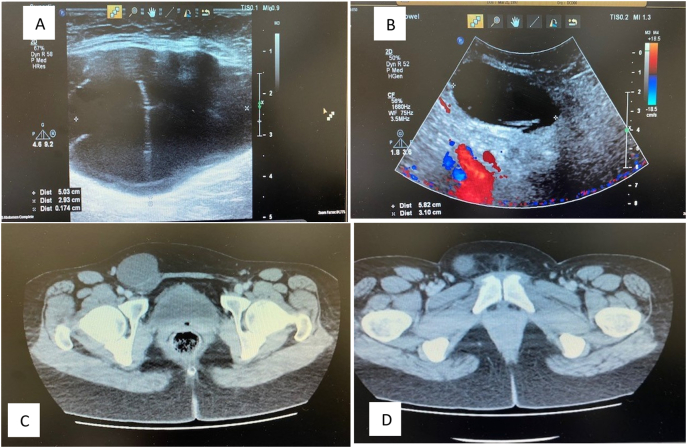

This is a 25-years old young female presented at the surgical clinic with a one-month history of right-sided palpable inguinolabial swelling that had been associated with pain and increased in size; the swelling had not changed with activity. The patient denied having a history of hernias or trauma in the past, and the bulge had not been presented throughout her life. On abdominal examination, there's a right-sided irreducible inguinolabial bulge around 5 × 4 cm that was tender to palpation, no overlying skin changes, and the cough impulse was negative. The blood investigations were unremarkable. Abdominal sonography and computed tomographic scan with intravenous contrast raveled a well-defined cystic lesion measuring 5.8 × 3.1 cm with multiple thin septations walls without obvious communication in a right inguinolabial area without internal and peripheral vascularization. Initially, a clinical diagnosis of femoral hernia was made, and the patient underwent electively for surgical exploration of the swelling through the inguinal skin crease incision. A right inguinal incision was made, and the inguinal canal opened. Dissection was carried out through the skin, subcutaneous tissue, scarp's facia, and external oblique aponeurosis; the inguinal canal was exposed, and the sizeable cyst-filled fluid was found accompanying the round ligament but not originating within it; upon further dissection, it became evident that the hydrocele contained no tube or ovary and no hernia, an isolated “encysted” cystic lesion was noticed lying in the inguinal canal extending from the superficial inguinal ring distally, the fluid-filled cyst was observed. The cyst was dissected en mass to separate from the accompanying round ligament, the proximal end communicated freely within the peritoneal cavity, and the midpoint of the canal of nuck was partially eliminated (Fig. 2E). Then the sac was transfixed. The round ligament and sac were resected, the high ligature was performed, and the specimen was sent for histopathology. Self-fixing prosthesis fashioned to close the anatomical defect and the abdomen closed-in layer. The patient tolerated the procedure well, and during the Postoperative period, the patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged the next day for further follow-up in outpatient. The histopathology examinations of the cyst revealed only a hernia sac: there was also a finding of mesothelial epithelium upon examination. This finding could confirm the presence of fluid. During further clinical evaluation for three months following the operation was unremarkable, and the patient remained asymptomatic without experiencing a recurrence.

Fig. 2.

(A) View shows rounded cystic lesion. (B) Encysted hydrocele was separated from underlying structures. (C) The distal hydrocele dissection en mass. (D) Fluid-filled cyst observed. (E) Cyst connected freely within the peritoneal cavity proximally, the process vaginalis “i.e. canal of nuck” at midpoint was partially patent this finding is equivalent to hydrocele type III “hour-glass”. (F) Histopathological slide hydrocele-typical features, including a mesothelial-lined cavity containing fibro adipose tissue and smooth muscle.

3. Clinical discussion

The term canal of Nuck it's described as the end protrusion of partial peritoneum in a female and corresponds to the process vaginalis peritonei in males. In females, the canal of nuck is a blind-ended evagination of partial peritoneum that descends the round ligament of the uterus in the inguinal canal into the labia majora, normally; the cephalic part of this peritoneal fold is obliterated before the birth, and then between the eight months to the first year of life usually the caudal structure eliminated in normal fetal development. Therefore the patency of the fold creates a potential space for specific pathology [4], [5]. Regardless of the etiological factor that amplify the site of the congenital disorder, the pathophysiology associated with inadequate embryological development owing to failure or incomplete closure of this communication, that potentiate the site of congenital disorder, either inguinal hernia or failure of obliteration at distal point result a cyst- fluid filled known as hydrocele canal of Nuck; the origin of the cysts, they are usually found accompanying the round ligament but not originating within it, there are two pathogenic mechanisms involved in the formation of the cyst fluid: the first results from accumulation due to the patency of the peritoneal fold and the inguinal canal, and the second is linked with the secretion of fluid from the peritoneal serosa of the cyst that cannot be reabsorbed [6], [7], [8], [9]. The term hydrocele pre-se is commonly seen in a male infant rather than a female's the hydrocele in females is the counterpart to spermatic cord hydrocele in males. Microscopically, the canal of the nuck has distinct feature layers; the outer layer of the abdominal wall (a fibrous layer thick with smooth muscle fibers) and the inner wall (a single layer of mesothelial cells) will be founded during the histopathological examination of the specimen. This condition has been reported under several names in medical literature, hydrocele canal of nuck, Nuck's cyst, female hydrocele, and cyst of the canal of nuck. It's a unique developmental disorder in adulthood, [10], [11]. The hydrocele of the canal of Nuck predominantly occurs in adult females and less frequently in infants and post-pubertal girls and the exact etiology is unknown, but an etiological factor contributes to the hydrocele canal of the nuck several [Table 1]. Anatomically, the hydrocele canal of Nuck has a variation and is classified into types depending on the cystic lesion’s location and peritoneal cavity communication into three varieties: communicating, non-communicating, and combination “hour-glass” hydrocele, type I known as non-communicable hydrocele is characterized by the encysted lesion that can be originated anywhere from the deep ring to the labia majora without peritoneal cavity communication. This type is considered a familiar one; type II hydrocele with persistent communication between a hydrocele and peritoneal cavity and quite a bit congenital type III, known as bilocular hydrocele, there is a constriction situated at the deep inguinal ring resulting in two parts; one is communicating, and another part is enclosed, known as an hour-glass hydrocele, it looks like a cyst within the cyst, and this type is the rarest variant one that documented in a single case only. In general, the female groin cystic mass is infrequently observed in clinical practice [12], [13], [14]. Besides that, an adult female hydrocele is an exceedingly rare developmental anomaly, and the incidence of cystic groin mass in surgical practice cystic groin mass is uncommon among adult females [13]. Clinically; most of the time, the inguinolabial lump in adult females populations is usually indistinguishable from other groin bulges and frequently misdiagnosed as an irreducible inguinal or femoral hernia respectively; less often than other groin differentials. It's worth mentioning that the inguinal hernia co-existed with a hydrocele canal of nuck and was observed in one-third of patients (30–40 %) of reported cases [12], [14]. The most clinical symptomatology is an ipsilateral palpable groin mass, usually painless; however, less often painful, slowly increases in size with time, and rarely does the hydrocele cause nausea and vomiting. The clinical findings on examination are ipsilateral inguinal or inguinolabial extended lump, neither compressible nor irreducible, non-tender to palpation, negative cough impulse, and transillumination report in a few cases. In the present case, the transillumination was difficult to appreciate; similarly, as in most reported cases, The diagnosis of a hydrocele is not guaranteed by transillumination, and the other groin differentials will also illuminate, e.g., gas-filled incarcerated intestine. The reason behind the difficult to be transilluminated is the coverage of external oblique aponeurosis. The bilateral hydrocele canal of nuck was documented in medical in a single case reported by Suman Bara et al. Based on each situation, the diagnosis varies, and most of the hydrocele canal of nuck is diagnosed intraoperatively. With a qualified and experienced radiologist’s hands, the various imaging modalities such as sonography, computed tomography scan, and magnetic resonance imaging are crucial for diagnosing the canal of the nuck hydrocele. Abdominal ultrasonography is a helpful evaluation of solid and cystic lesions, and easily applied, and is accurate for proper diagnosis with features of hypoechoic or anechoic, generally unilocular, and rarely multilocular (including the linear septa) cystic masses with posterior shadowing without internal and peripheral vascularization (Fig. 1A & B). Edmund et al. reported that Valsalva maneuvers during ultrasound visualization could also help differentiate from hernias [15], [16]. In addition, a computed tomography scan of the abdomen with intravenous contrast media is a diagnostic tool has featured such as a comma- sign like cyst (Fig. 1D). But the best pre-operatively imaging modality is MRI. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging has a higher diagnostic value. It provides specific detailed anatomical relation with the other structural and above that in evaluating consistency, contact of mass, assessing peritoneal cavity communication, and utilizing other groin masses, the lesion in T1 hypointense and hyperintense in T2 [17]. Most of the cases, the diagnosis was made intra-operatively as mentioned earlier, as in the present case. Operative management is the standard treatment of adult female hydrocele by conventional or minimally invasive surgery. Complete surgical resection of hydrocele “hydrocelectomy”, round ligament, as well as high ligation of the canal of nuck, and prosthetic applying mesh, is the treatment of choice [18]. The anatomical repair has been reported. Laparoscopic surgery had been recorded in a few cases in a selected group of patients of childbearing age, without current pathology, an experienced surgeon's hands. Alternative treatment options, including ultrasound-guided aspiration of cysts, have not been documented in a single case in medical literature and carry a higher risk of recurrence once it is done [19], [20]. In this case, intra-operatively, a rare variant type of hydrocele was discovered. The lesion's distal ‘lower’ part was encysted and extended from the superficial inguinal ring down to the labia. The midline of the canal of the nuck is partially obliterated and constricted by the deep inguinal ring and the proximal “upper” end was freely communicating within the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 2E). The highlights in the current case are these findings correspondingly type III “hour-glass” hydrocele canal of nuck. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of a hydrocele canal of nuck in an adult female operated by conventional surgery in our institute in Saudi Arabia. That has the rarest variant type of hydrocele that has been documented in a single case report through the medical literature worldwide (Illustration 1).

Table 1.

An etiological factor that contributes of the hydrocele canal of nuck.

|

Fig. 1.

Abdominal sonography showed a large cystic lesion around 5.8 × 3.1 with internal septation (A). No internal or peripheral vascularity was demonstrated (B) Ct axial raveled a comma-like-cyst (D).

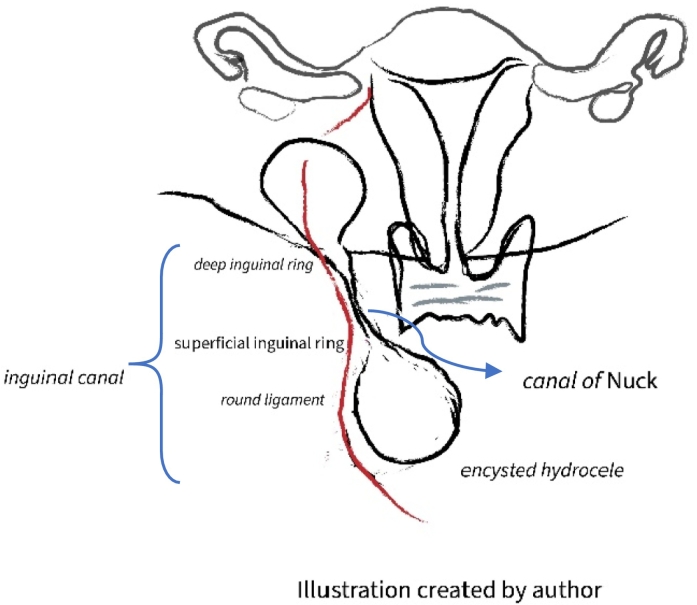

Illustration 1.

This is a drawing illustration demonstrated the present case. Type III hydrocele had a combination of enclosed encysted hydrocele and peritoneal cavity -communicating cyst with the construction of process vaginalasis ‘canal of Nuck’ at the midpoint of the deep inguinal ring which gave a characteristic shape of the hour-glass cyst.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, encysted “isolated” female hydrocele is extremely rare in surgical practice and should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any inguinolabial swelling in adult females. This condition can be misdiagnosed as an irreducible inguinal or strangulated femoral hernia due to its rarity, which makes the clinical diagnosis challenging. The diagnosis can be suspected after a completed medical history and a careful clinical examination. A skilled-qualified multidisciplinary team of a surgeons, radiologists, and pathologists is required to approach the condition. In some patients, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is employed for diagnosis. The best way to make a final diagnosis of a female hydrocele canal of nuck is based on surgical-pathological correlation. The conventional surgical approach is an excellent and safe option for treating an adult female encysted hydrocele canal of nuck.

Learning point

-

1-

Be familiar with uncommon causes of inguinal labial swelling in adult females.

-

2-

Integrating the clinical-radiological features of the hydrocele canal of nuck.

-

3-

The final diagnosis is made by surgical approach and confirmed by histopathological examination.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Ethical approval

IRB approval.

Funding

No source of funding.

Guarantor

Sahar M. Aldhafeeri.

Research registration number

N/A.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

-

-

Sahar M Aldhafeeri: the corresponding author, writing the paper & revising the manuscript and illustration.

-

-

Ali Aalaqoul, Faisal Sabaa, Abdulaziz Alghazwi: articles review.

-

-

May Alkhaldi: searched for references.

-

-

Muhanned Alqahatani: highlights, tables, imaging, intraoperative views, and references citation.

Conflicts of interest

N/A.

References

- 1.Prodromidou Anastasia. Cyst of the Canal of Nuck in adult females: a case report and systematic review. Biomed. Rep. 2020 Jun;12(6):333–338. doi: 10.3892/br.2020.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Javed Nafees. Laparoscopic excision of cyst of the canal of nuck. J. Minimal Access Surg. Apr-Jun 2014;10(2) doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.129960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., for the SCARE Group The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagul A. Endometriosis in the canal of nuck hydrocele: an unusual presentation. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2011:288–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim Kwang Seog. Hydrocele of the canal of nuck in a female adult. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2016 Sep;43(5) doi: 10.5999/aps.2016.43.5.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shariff M.H. A rare developmental disorder ‘Hydrocele of canal of Nuck’ - a case report. IJBAR. 2014;05(03) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soh Edmund. Hydrocele of the canal of Nuck: ultrasound and MRI findings. Rep. Med. Imaging. 2011;4:15–17. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heer Jagdipak. Hydrocele of the canal of nuck. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2015 Sep;16(5):786–787. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.6.27582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaeser Martha A. Hydrocele in the canal of nuck. J. Med. Ultrason. 2011;19 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucas J.W. Canal of nuck hydrocele in an adult female. Urol. Case Rep. 2019;23:67–68. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patnam Varun. A cautionary approach to adult female groin swelling: hydrocoele of the canal of nuck with a review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-212547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caviezel A. Female hydrocele: the cyst of nuck. Urol. Int. 2009;82:242–245. doi: 10.1159/000200808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunni John. Hydrocele of the canal of nuck — an old problem revisited. Front. Med. 2013;7(4):517–519. doi: 10.1007/s11684-013-0300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Topal Ugur. Cyst of the canal of nuck mimicking inguinal hernia. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2018;52:117–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vinod Kumar Nigam Hydrocele of canal of the nuck: a case report. Int. J. Surg. Sci. 2021;5(4):97–99. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baral Suman. Bilateral Hydrocele of the Canal of Nuck: A Rare Presentation in an Adult Female. Vol. 13. 2020. pp. 313–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott Michael. Rare encounter: hydrocoele of canal of nuck in a scottish rural hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-237169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fikatas Panagiotis. Hydroceles of the canal of nuck in adults—diagnostic, treatment, and results of a rare condition in females. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9:4026. doi: 10.3390/jcm9124026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biggs Danielle. Hydroceles—not just for men. J. Emerg. Med. 2017 Sep;53(3):388–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Liming. Laparoscopic-assisted hydrocelectomy of the canal of Nuck: a case report. Surg. Case Rep. 2021;7:52. doi: 10.1186/s40792-021-01137-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]