Abstract

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, attention has been drawn to conspiracy theories. To date, research has largely examined commonalities in conspiracy theory belief, however it is important to identify where there may be notable differences. The aim of the present research was first to distinguish between typologies of COVID-19 conspiracy belief and explore demographic, social cognitive factors associated with these beliefs. Secondly, we aimed to examine the effects of such beliefs on adherence to government health guidelines.

Participants (N = 319) rated well known COVID-19 conspiracy theories, completing measures of thinking style, socio-political control, mistrust, verbal intelligence, need for closure and demographic information. Participants also rated the extent to which they followed government health guidelines.

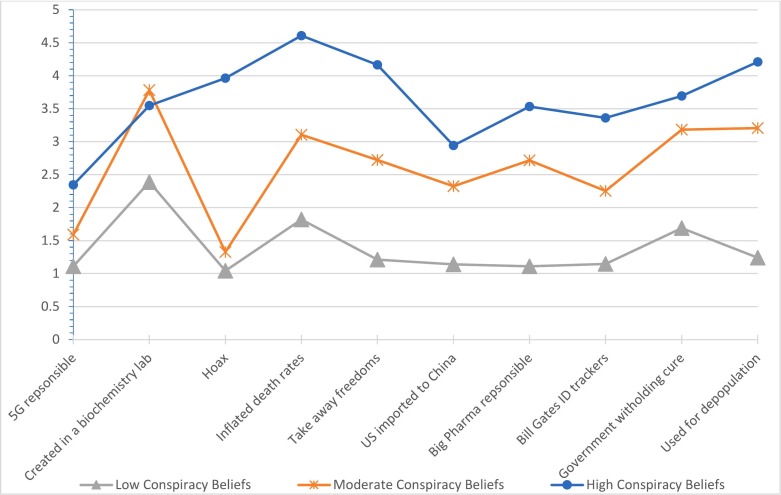

Latent profile analysis suggests three profiles of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs with low, moderate, and high COVID conspiracy belief profiles and successively stronger endorsement on all but one of the COVID-19 conspiracy theories.

Those holding stronger COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs are more likely to reason emotively, feel less socio-political control, mistrust others, have lower verbal ability and adhere less to COVID-19 guidelines. The social and health implications of these findings are discussed.

Keywords: Covid-19, Conspiracy beliefs, Conspiracy theories

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought conspiracy theories (CT) to the fore which have flourished online (Cinelli et al., 2022). Prominent CT posit that coronavirus is a bioweapon, that 5G is responsible for the spread of coronavirus (Ahmed et al., 2020) and even that the virus is a hoax (van Mulukom et al., 2022). CT are defined as ‘attempts to explain the ultimate causes of significant social and political events and circumstances with claims of secret plots by two or more powerful actors’ (Douglas et al., 2019, p.4), and often arise in times of crisis. Feelings of uncertainty and threat contribute towards a greater tendency to endorse CT (Lee & Koo, 2022). In recent years, there have been considerable efforts to understand the psychological factors that underpin belief in CT.

1.1. Psychological motives and COVID-19 CT

One influential perspective is that CT satisfy epistemic (avoiding uncertainty), existential (feeling in control of environment) and social (maintaining a positive self/in-group image) psychological needs not yet met (Douglas, 2021; Douglas et al., 2017; Douglas et al., 2019). Epistemic and existential motives were considered further in our study.

Need for cognitive closure is an important epistemic motive that involves the need to obtain a definitive answer (Webster & Kruglanski, 1997). CT can provide an explanatory framework for otherwise inexplicable or complex events and thus, people high in need for cognitive closure may be more likely to endorse CT (Marchlewska et al., 2018). Avoiding uncertainty has been positively associated with belief in COVID-19 CT (Alper et al., 2021; Miller, 2020) however some evidence suggests that need for cognitive closure has a stronger relationship with general conspiracy mentality and specific CT beliefs compared to COVID-19 CT (Gligoric et al., 2021) therefore warranting further investigation.

In the current study, existential motives were conceived as socio-political control and mistrust. Research has demonstrated lower socio-political control is associated with conspiracy mentality (Bruder et al., 2013) and negatively related to both general and COVID-19 CT (Peitz et al., 2021). Furthermore, we examined whether COVID-19 CT are more likely to be endorsed when people are mistrusting of others. Research has found an association between trust, conspiracy beliefs and vaccine hesitancy (Allington et al., 2021; Jennings et al., 2021). Skepticism around COVID-19 death figures, perceived corruption, and scandals over personal protection equipment have been implicated for untrustworthy behaviour by the government (Jennings et al., 2021) highlighting the importance of public trust in government during the pandemic.

1.2. Cognitive factors and COVID-19 CT

While CT satisfy some epistemic and existential motives, they cannot fully explain conspiracy theory beliefs and consequences of these (Douglas et al., 2017). Individuals may differ in relation to their cognitive style (i.e. thinking analytically vs. intuitively) and cognitive ability. Theoretical models posit two types of thinking; experiential thinking (Type 1), which is heuristic based, fast, intuitive, and emotive and rational thinking (Type 2), which is conscious, deliberate, and effortful (Epstein et al., 1996). The dual process model of thinking styles has been challenged (e.g. Kruglanski & Gigerenzer, 2018; Melnikoff & Bargh, 2018) and continues to be developed further (e.g. Pennycook, 2022) however it would be expected that people who engage in rational thinking when processing information, would be in a better position to avoid biases often associated with experiential thinking, such as hasty or erroneous decisions. There is evidence emerging that CT are associated with lower analytical thinking and higher intuitive thinking (van Prooijen et al., 2022; see also Binnendyk & Pennycook, 2022). In the context of the pandemic, rational thinking has been positively associated with rejecting COVID-19 CT (Pennycook et al., 2020; Stanley et al., 2020) in addition to being positively associated to compliance with health guidelines (Swami & Barron, 2021). Furthermore, cognitive ability can shield against conspiracy beliefs (Rizeq et al., 2021; Ståhl & van Prooijen, 2018). Factors such as verbal intelligence could protect against CT by providing the ability to spot language that may be suggestive or inaccurate (Stasielowicz, 2022).

1.3. Aims of the study

We explored demographic factors, psychological motives, cognitive factors and adherence to health guidelines associated with COVID-19 CT. Such psychological motives and cognitive factors are rarely examined together in studies or using analytical methods such as Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) which can tell us whether people that endorse CT belong to distinct profiles or form a general mindset (Frenken & Imhoff, 2021). LPA unlike other variable-centred approaches e.g., confirmatory factor analysis, is a person-centred approach and useful because of its focus on participants' characteristics, and in particular pattern responding (Williams & Kibowski, 2016). It can distinguish between subgroups within a large heterogeneous population and is therefore useful to capture the nature of conspiracy beliefs. First, we aimed to examine whether belief in COVID-19 CT was associated with need for cognitive-closure, socio-political control, mistrust, rational thinking, experiential thinking, and verbal intelligence. Second, correlational evidence supports a link between endorsing COVID related CT and real-life consequences (Jolley & Paterson, 2020). Therefore, we aimed to explore whether belief in COVID CT was associated with adherence to health guidelines.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Three-hundred-nineteen participants took part. There were more females (197, 61.8%) than males (118, 37%), 3 participants did not indicate their gender (0.9%) and one indicated ‘other’ (0.3%). The mean age of the sample was 38 years (SD = 15.0). One-hundred-seventy-four participants had no university education (40%), compared to 143 participants with a university education (33%). Most of the sample were British (n = 258, 81.6%). The sample was recruited online using an online survey platform (Qualtrics) and the study was advertised via Twitter and university contacts. Data were collected between July 2020 and April 2021.

2.2. Materials & Procedure

Once informed consent was complete, participants completed the following measures and demographic information via Qualtrics, an online survey platform.

2.2.1. COVID-19 CT

COVID-19 related CT were gathered from Internet searches. These were CT that were prominent in mainstream news and were formulated into 10 items (α = 0.91; see Table 1). Participants were asked to rate each item on a scale of 1–5 (strongly disagree-strongly agree). Higher scores indicated greater endorsement of COVID-19 CT.

2.2.2. Self-reported thinking style

The Rational-Experiential Inventory (Epstein et al., 1996) comprises 10 items with 5 items measuring need for cognition (α = 0.78), which relates to rational thought and 5 items measuring faith-in-intuition (α = 0.85) which relates to intuitive-experiential thought. For example, one of the intuitive items reads: ‘I believe in trusting my hunches’ while a rational item reads: ‘I prefer complex problems to simple problems’. Participants respond on a scale of 1–5 (completely false-completely true). Higher scores reflect higher intuitive or rational thought.

2.2.3. Mistrust

The International Personality Item Pool Mistrust Scale (Goldberg et al., 2006) asks participants to describe how they feel at this very moment with 6 items measuring trust (α = 0.77). For example, one item reads: ‘I suspect hidden motives in others. Participants rate items on a scale of 1–6, (Very Inaccurate-Very accurate). Higher scores indicate greater mistrust.

2.2.4. Socio-Political Control

The Socio-Political Control Scale (Paulhus & Van Selst, 1990) examines the level of control participants perceive they have in the socio-political realm. This subscale has 10 items (α = 0.73) that are rated on a scale of 1–7 (totally inaccurate-totally accurate). An example item reads: ‘With enough effort we can wipe out political corruption.’ Higher scores indicate lower perceived socio-political control.

2.2.5. Need for Cognitive Closure

The Need for Cognitive Closure Scale (Roets & Van Hiel, 2011) measures participants' need for certainty. The measure contains 15 items (e.g., ‘When I have made a decision, I feel relieved.’). These are rated on a 6-point scale from 1 to 6 (strongly disagree-strongly agree). Higher total scores indicate a greater need for cognitive closure. This scale showed very good reliability (α = 0.87).

2.2.6. Verbal intelligence

The Wordsum tests vocabulary knowledge and correlates highly with other measures of intelligence (Huang & Hauser, 1996). A list of 10 words is presented to participants. Individual words must be matched with corresponding words of the same meaning, out of 5 possible matches (e.g., LIFT: sort out, raise, value, enjoy, fancy). Verbal intelligence is indicated by the number of correctly matched words.

2.2.7. Adherence to guidelines

A series of guidelines that were produced by the government (handwashing, staying at home, social distancing, not meeting others outside household, avoiding touching face, avoiding public transport and social gatherings) was presented to participants and rated on a scale of 1–5 (definitely have not followed guidelines-definitely have followed guidelines). Seven items were used and displayed acceptable reliability (α = 0.69). Higher scores indicated greater adherence to guidelines.

2.2.8. Demographic information

Demographic information comprised gender, age, education, and nationality.

3. Results

3.1. Correlations

Bivariate correlations were conducted between all variables of interest and COVID-19 CT. All variables showed a weak but significant correlation with COVID-19 CT except for health guidelines (see Table 2).

3.2. Analytic strategy and LPA results

Seventy-four percent of the data was present; however, we tested the data for patterns of missing using Little’'s test (Little, 1988). Results suggested data was missing completely at random (MCAR) (χ2 = 32.520, p = 0.13).

We conducted a 3-step Latent Profile Analysis (LPA: Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014) using ten items pertaining to COVID-19 CT. The LPA framework generated topologies based on participants' experiences, and the emergent typologies were examined in relation to various predictors (age, gender, education) and outcomes (thinking style, mistrust, perceived socio-political control, verbal intelligence, and need for closure; see Table 3 for descriptive statistics). To account for the violation of conditional independence (Collins & Lanza, 2010), we used WITH (correlation) statements in our analysis to allow for partial conditional independence (Muthén, 2004).

Six separate models were assessed using a range of fit indices to determine best fit of the data, i.e., the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC: Akaike, 1987), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC: Schwarz, 1978) were used to ascertain model fit. Better fitting models are indicated by lower values of the AIC, and the BIC. Parsimony of classes was assessed using the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (p < 0.05) (LRT: Lo et al., 2001) and the Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio test (p > 0.05) (BLRT; McLachlan & Peel, 2004). R3step is a command within Mplus suitable for exploring relationships between the latent class variable and predictor variables i.e., age, gender, and education. The relationship between the latent predictor (profiles of Covid-19 conspiracy theory beliefs) and distal outcomes (rational thinking, intuitive thinking, mistrust, etc.) was evaluated using the BCH command in Mplus. This approach uses regression analysis with a Wald test to estimate a distal outcome model (Table 6 ) (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014; Lanza et al., 2013). Mplus 8.6 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) with maximum-likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR: Yuan & Bentler, 2000) was used. Data is available upon request from the authors or from the Open Science Framework website. Fig. 1 depicts the hypothesized model, where x are covariates, c is the underlying latent variable, y are the distal outcomes and u represent the conspiracy indicators.

Table 6.

Shows profile-specific means of distal outcomes.

| Low conspiracy beliefs |

Moderate conspiracy beliefs |

High conspiracy beliefs |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) P-value | Mean (SE) P-value | Mean (SE) P-value | |

| Rational thinking | 19.44 (0.3)⁎⁎ | 18.36 (0.3)⁎⁎ | 18.50 (0.6)⁎⁎ |

| Emotive thinking | 17.29 (0.2)⁎⁎,a | 19.18 (0.3)⁎⁎, b | 20.68 (0.5)⁎⁎ |

| Mistrust | 14.42 (0.3)⁎⁎, a | 16.66 (0.4)⁎⁎ | 18.00 (0.6)⁎⁎ |

| Socio-political control | 37.83 (0.6)⁎⁎, a | 33.98 (0.9)⁎⁎ | 32.41 (1.0)⁎⁎ |

| Need for closure | 46.74 (0.8)⁎⁎ | 46.80 (1.2)⁎⁎ | 43.96 (1.8)⁎⁎ |

| Verbal ability | 6.57 (0.1)⁎⁎, a | 5.71 (0.1)⁎⁎, b | 5.02 (0.2)⁎⁎ |

| Adherence to health guidelines | 5.80 (0.3)⁎⁎, b | 4.50 (0.4)⁎⁎, b | 3.44 (0.4)⁎⁎ |

P < 0.001.

Estimate is significantly different to other profile estimates.

Estimate is significantly different to only high conspiracy belief estimates.

Fig. 1.

A depiction of the hypothesized model

3.3. Latent profile analysis

The 3-class solution was a better fit for the data than the 1 and 2-class models due to decreasing AIC, and BIC. The higher and insignificant LRMT (P > 0.05) in the 4-class model suggested the 3-class was more parsimonious. Models 5, 6 were rejected based on increasing BICs and insignificant LMRTs but also small class sizes (<20) that were considered impractical. Within the 3-class solution, the average probability of belonging to that class was 0.98–0.99 indicating excellent accuracy (higher values indicate certainty and good class separation). The 3-class solution and estimated means are illustrated in Fig. 2 . Model fit for all profiles are shown in Table 4.

Fig. 2.

Profile plot of conspiracy beliefs.

Profile 1 (56.7%, n = 184) labelled the ‘low conspiracy belief’ group as these individuals endorsed the lowest scores across all conspiracy belief items. Profile 2 (27.9%, n = 90) labelled ‘moderate conspiracy belief’ and represented individuals with moderately high levels of conspiracy beliefs. Profile 3 (15.3%, n = 50) labelled ‘High conspiracy beliefs’ group since these individuals endorsed the highest scores across all conspiracy belief items. There was no observed relationship between the demographic predictors, age, gender, and education and the profiles (p > 0.05). Results for each of the distal outcomes are reported in Table 5. Results of the WALD test showed significant between profile differences on all distal outcomes χ 2(df = 14) = 152.915, p < 0.001. Those with high conspiracy belief scored significantly higher on emotive thinking and mistrust. Those with moderate conspiracy beliefs scored significantly lower on rational thinking. Those with low conspiracy beliefs scored significantly higher on need for closure, socio-political control, verbal ability, and adherence to COVID-19 guidelines.

4. Discussion

This study identified COVID-19 conspiracy belief typologies and their associations with thinking styles, mistrust, need for closure, verbal intelligence, perceived socio-political control and adherence to health guidelines. LPA revealed low, moderate, and high COVID-19 conspiracy belief profiles with progressively stronger endorsement of all but one questionnaire item. Using a different methodological approach, our findings partially replicate previous research (e.g., Alper et al., 2021) and support Frenken and Imhoff's (2021) proposal that conspiracy topics can be viewed as a unified mindset that varies across situations but remains consistent among individuals.

Correlations and LPA demonstrated that those more prone to intuitive/emotive thinking were more susceptible to believing in COVID-19 conspiracies. COVID-19 evokes strong emotions (Maxfield & Pituch, 2021) and COVID-related worries would likely amplify emotive reasoning, leaving those with such tendencies more vulnerable to other COVID-related theories, further agitating strong emotions. Conversely, those low in conspiracy beliefs were more likely to see themselves as rational thinkers. As with studies on other types of conspiracy belief (Barron et al., 2018; Georgiou et al., 2019), this suggests analytical thinking can protect against believing in COVID conspiracies. However, this relationship was not linear - those with moderate rather than high COVID conspiracy beliefs scored the lowest on rational thinking. Those with high COVID conspiracy beliefs were lower in verbal ability, consistent with previous studies showing that cognitive ability is protective against conspiracy beliefs (Rizeq et al., 2021; Ståhl & van Prooijen, 2018).

Contrary to expectations, need for closure was lower in those with the strongest COVID conspiracy beliefs, suggesting that COVID conspiracy believers are more (not less) tolerant of uncertainty. This conflicts with Douglas et al., 2017, Douglas et al., 2019, Douglas (2021) thesis that conspiracy beliefs attract those with epistemic need for straightforward answers to uncertainties. Perhaps a more nuanced analysis of need for closure is needed. We measured this construct as a trait, but it can also be situationally determined (Webber et al., 2018) or culturally influenced (Chiu et al., 2000). There are also separate dimensions to need for closure: in particular, the seizing effect (the drive to reach a conclusion quickly) and the freezing effect (desire to maintain conclusions over time rather than amend them) (see Kruglanski & Webster, 1996). Future work should consider these more fine-grained aspects when studying the role of need for closure in conspiracy belief.

Our data reveal that social-cognitive factors may be just as crucial in predicting belief on COVID conspiracies as thinking styles or need for closure. Recourse to CTs emerge as a response to feelings of powerlessness and diminished control (Bruder et al., 2013). Our data concur with this: those with the strongest COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs felt significantly less socio-political control than those with the weakest COVID conspiracy beliefs. This suggests that COVID conspiracies arise in part, as a way to make sense of such power imbalances (see Swami & Coles, 2010) or, in Douglas et al., 2017, Douglas et al., 2019, Douglas (2021), to satisfy existential needs around feeling safe and in control of one’'s environment.

Perceiving such lack of control can result in externalising anger onto perceived enemy outgroups and mistrust of others (Abalakina-Paap et al., 1999; Goertzel, 1994). Our findings show mistrust of others was stronger in those with higher conspiracy beliefs compared to those with lowest conspiracy beliefs. Indeed, suspicion about others' intentions is a motif commonly reflected in other CT whereby malevolent others operate in secret to benefit themselves at the expense of the rest (Sunstein & Vermeule, 2009). Hence, it is conceivable how a baseline tendency for mistrust enhances belief in theories about pernicious and untrustworthy actors. The combination of mistrust and perception of low political control has potential to erode faith in political institutions and weaken social relationships (Frenken & Imhoff, 2022; van Prooijen et al., 2022).

Taken as a whole, these findings are in line with van Prooijen's (2019) existential threat model. According to Van Prooijen, perceptions of existential threat are fostered by mistrust of others and perceived vulnerability - which in the current study can be conceptualised as low socio-political control. In such conditions, conspiracy belief formation is more likely due to cognitive biases such as emotive thinking or low analytical thought. An important component of Van Prooijen’'s model not measured here was the existence of a despised outgroup onto which conspiracies could be projected.

Consistent with this and previous literature (Douglas, 2021), COVID-19 conspiracies have negative consequences associated with guideline compliance. Previous research shows such beliefs are negatively associated with preventative behaviors and intentions to vaccinate (Imhoff & Lamberty, 2020). The current study is no exception, the stronger the endorsement of CT, the lower the adherence to COVID-19 related health guidelines.

4.1. Limitations

The study has limitations, including that some of the COVID-related CT items could be more explicit (specifically Items 1 and 2, Table 1), and it's uncertain whether the items cover the full range of current COVID-19 CT. While the measures used were mostly validated, the measure of COVID-19 CT and health guidelines were developed for this study and not psychometrically validated. COVID-19 conspiracies are a new concept, and no measures were available at the time of the study's development. Nonetheless, the specific theories were prominent and well known to the general population.

4.2. Implications and future research

Our research has two main implications: first, belief in COVID CT is associated with psychological motives, cognitive factors, and behaviour (specifically, following government guidance). Second, CT are endorsed in a consistent pattern across social cognitive factors and supports a general conspiracy mentality approach (Frenken & Imhoff, 2021). Future research should examine both psychological motives and cognitive factors for specific CT that challenge the conspiracy mentality. The causality in these associations is unclear, therefore, it is vital that future research examines causation. Our research provides insight into the interrelationships between endorsement level of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and psychological factors, providing vital understanding of how to tackle CT belief and their consequences.

4.3. Conclusions

The results from LPA suggested three profiles of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs showing successively stronger endorsement of the COVID-19 CT, which provides evidence of a general conspiracy mindset. Generally, stronger COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs are associated with emotive reasoning, feeling lower socio-political control, mistrusting others, lower verbal ability and lower adherence to COVID-19 guidelines.

Funding sources

None.

Research & publication ethics

This manuscript adheres to ethical guidelines specified in the APA Code of Conduct and authors' national ethics guidelines.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2023.112155.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary tables

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abalakina-Paap M., Stephan W.G., Craig T., Gregory L.W. Belief in conspiracies. Political Psychology. 1999;20(3):637–647. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W., Vidal-Alaball J., Downing J., Sigui F.L. COVID-19 and the 5G conspiracy theory: Social network analysis of twitter data. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020;22(5) doi: 10.2196/19458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaike H. Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika. 1987;52(3):317–332. [Google Scholar]

- Allington D., Duffy B., Wessely S., Dhavan N., Rubin J. Health-protective behaviour, social media usage and conspiracy belief during the COVID-19 public health emergency. Psychological Medicine. 2021;51(10):1763–1769. doi: 10.1017/S003329172000224X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alper S., Bayrak F., Yilmaz O. Psychological correlates of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and preventive measures: Evidence from Turkey. Current Psychology. 2021;40:5708–5717. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00903-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T., Muthén B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2014;21(3):329–341. [Google Scholar]

- Barron D., Furnham A., Weis L., Morgan K.D., Towell A., Swami V. The relationship between schizotypal facets and conspiracist beliefs via cognitive processes. Psychiatry Research. 2018;259:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binnendyk J., Pennycook G. Intuition, reason, and conspiracy beliefs. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2022;47 doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruder M., Haffke P., Neave N., Nouripanah N., Imhoff R. Measuring individual differences in generic beliefs in CT across cultures: Conspiracy mentality questionnaire. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4:225. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C.Y., Morris M.W., Hong Y.Y., Menon T. Motivated cultural cognition: The impact of implicit cultural theories on dispositional attribution varies as a function of need for closure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78(2):247. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinelli M., Etta G., Avalle M., Quattrociocchi A., Di Marco N., Valensise C., Galeazzi A., Quattrociocchi W. CT and social media platforms. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2022;47 doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L., Lanza S. Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social. Behavioral, and Health Sciences. 2010 doi: 10.1002/9780470567333.indsub. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas K.M. Covid-19 CT. Group Processes & Inter-group Relations. 2021;24(2):270–275. doi: 10.1177/1368430220982068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas K.M., Sutton R.M., Cichocka A. The psychology of CT. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2017;26(6):538–542. doi: 10.1177/0963721417718261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas K.M., Uscinski J.E., Sutton R.M., Cichocka A., Nefes T., Ang C.S., Deravi S. Understanding CT. Political Psychology. 2019;40(S1):3–35. doi: 10.1111/pops.12568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein S., Pacini R., Denes-Raj V., Heier H. Individual differences in intuitive–experiential and analytical–rational thinking styles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71(2):390–405. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.2.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenken M., Imhoff R. A uniform conspiracy mindset or differentiated reactions to specific conspiracy beliefs? Evidence from latent profile analyses. International Review of Social Psychology. 2021;34(1):27. doi: 10.5334/irsp.590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frenken M., Imhoff R. Malevolent intentions and secret coordination. Dissecting cognitive processes in conspiracy beliefs via diffusion modeling. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2022;103 [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou M., Delfabbro P.H., Balzan R. Conspiracy beliefs in the general population: The importance of psychopathology, cognitive style and educational attainment. Personality and Individual Differences. 2019;151 [Google Scholar]

- Gligoric V., da Silva, Eker S., van Hoek N., Nieuwenhuijzen E.…Zeighami G. The usual suspects: How psychological motives and thinking styles predict the endorsement of well-known and COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2021;35(5):1171–1181. doi: 10.1002/acp.3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goertzel T. Belief in CT. Political Psychology. 1994;15(4):731–742. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg L.R., Johnson J.A., Eber H.W., Hogan R., Ashton M.C., Cloninger C.R., Gough H.G. The international personality item pool and the future of public- domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Huang M.H., Hauser R.M. Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin; Madison: 1996. Trends in Black-White test score differentials: II. The WORDSUM vocabulary test. [Google Scholar]

- Imhoff R., Lamberty P. A bioweapon or a Hoax? The link between distinct conspiracy beliefs about the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak and pandemic behavior. Social Psychological & Personality Science. 2020;11(8):1110–1118. doi: 10.1177/1948550620934692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings W., Stoker G., Bunting H., Valgarðsson V.O., Gaskell J., Devine D., McKay L., Mills M.C. Lack of trust, conspiracy beliefs, and social media use predict COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines. 2021;9:593. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley D., Paterson J.L. Pylons ablaze: Examining the role of 5G COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and support for violence. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2020;59(3):628–640. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski A.W., Gigerenzer G. In: The Motivated Mind. Kruglanski A.W., editor. Routledge; 2018. Intuitive and deliberate judgments are based on common principles. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski A.W., Webster D.M. Motivated closing of the mind:" seizing" and" freezing". Psychological Review. 1996;103(2):263–283. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza S.T., Tan X., Bray B.C. Latent class analysis with distal outcomes: A flexible model-based approach. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2013;20(1):1–26. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2013.742377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T., Koo G.H. What drives belief in COVID-19 CT? Examining the role of uncertainty, negative emotions, and perceived relevance and threat. Health Communication. 2022 doi: 10.1080/10410236.2022.2134703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R.J.A. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1988;83:1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y., Mendell N.R., Rubin D.B. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88(3):767–778. [Google Scholar]

- Marchlewska M., Cichocka A., Kossowska M. Addicted to answers: Need for cognitive closure and the endorsement of conspiracy beliefs. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2018;48(2):109–117. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield M., Pituch K.A. COVID-19 worry, mental health indicators, and preparedness for future care needs across the adult lifespan. Aging Mental Health. 2021;25(7):1273–1280. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1828272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan G., Peel D. John Wiley & Sons; 2004. Finite mixture models. [Google Scholar]

- Melnikoff D.E., Bargh J.A. The mythical number two. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2018;22(4):280–293. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. Psychological, political, and situational factors combine to boost COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs. Canadian Journal of Political Science. 2020;53(2):327–334. doi: 10.1017/S000842392000058X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. In: Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences. Kaplan D., editor. Sage; 2004. Latent variable analysis: Growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data; pp. 345–368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L.K., Muthén B.O. 2017. Mplus: Statistical Analysis With Latent Variables: User's Guide (Version 8) Authors. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus D.L., Van Selst M. The spheres of control scale: 10Yr of research. Journal of Personality and Individual Differences. 1990;11(10):1029–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Peitz L., Lalot F., Douglas K., Sutton R., Abrams D. COVID-19 CT and compliance with governmental restrictions: The mediating roles of anger, anxiety, and hope. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology. 2021;15 doi: 10.1177/18344909211046646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pennycook G. A framework for understanding reasoning errors: From fake news to climate change and beyond. 2022. https://psyarxiv.com/j3w7d

- Pennycook G., Cheyne J.A., Koehler D.J., Fugelsang J.A. On the belief that beliefs should change according to evidence: Implications for conspiratorial, moral, paranormal, political, religious, and science beliefs. Judgment & Decision Making. 2020;15(4):476–498. [Google Scholar]

- Rizeq J., Flora D.B., Toplak M.E. An examination of the underlying dimensional structure of three domains of contaminated mindware: Paranormal beliefs, conspiracy beliefs, and anti-science attitudes. Thinking and Reasoning. 2021;27(2):187–211. doi: 10.1080/13546783.2020.1759688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roets A., Van Hiel A. Item selection and validation of a brief, 15-item version of the need for closure scale. Personality & Individual Differences. 2011;50:90–94. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 1978;6(2):461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Ståhl T., van Prooijen J.W. Epistemic rationality: Skepticism toward unfounded beliefs requires sufficient cognitive ability and motivation to be rational. Personality and Individual Differences. 2018;122:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.10.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley M.L., Barr N., Peters K., Seli P. Analytic-thinking predicts hoax beliefs and helping behaviors in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Thinking & Reasoning. 2020;1–14 doi: 10.1080/13546783.2020.1813806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stasielowicz L. Who believes in CT? A meta-analysis on personality correlates. Journal of Research in Personality. 2022;98 doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2022.104229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein C.R., Vermeule A. CT: Causes and cures. The Journal of Political Philosophy. 2009;17(2):202–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9760.2008.00325.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swami V., Barron D. Rationalthinking, rejection of Coronavirus (COVID-19) conspiracy theories/ theorists, and compliance with mandated requirments: Direct and indirect relationships in a nationally representative sample of adults in the United Kingdom. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology. 2021;15:1–11. doi: 10.1177/18344909211037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swami V., Coles R. The truth is out there: Belief in CT. The Psychologist. 2010;23(7):560–563. [Google Scholar]

- van Mulukom V., Pummerer L.J., Alper S., Bai H., Čavojová V., Farias J., Kay C.S., Lazarevic L.B., Lobato E.J.C., Marinthe G., Pavela Banai I., Šrol J., Žeželj I. Antecedents and consequences of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine. 2022;301 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Prooijen J.W. An existential threat model of CT. European Psychologist. 2019;25(1):16–25. [Google Scholar]

- van Prooijen J.W., Spadaro G., Wang H. Suspicion of institutions: How distrust and CT deteriorate social relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2022;43:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber D., Babush M., Schori-Eyal N., Vazeou-Nieuwenhuis A., Hettiarachchi M., Bélanger J.J., Moyano M., Trujillo H.M., Gunaratna R., Kruglanski A.W., Gelfand M.J. The road to extremism: Field and experimental evidence that significance loss-induced need for closure fosters radicalization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2018;114(2):270–285. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster D.M., Kruglanski A.W. Cognitive and social consequences of the need for cognitive closure. European Review of Social Psychology. 1997;8(1):133–173. doi: 10.1080/14792779643000100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G.A., Kibowski F. Handbook of Methodological Approaches to Community-based Research: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods. 2016. Latent class analysis and latent profile analysis; pp. 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan K.-H., Bentler P.M. Three likelihood-based methods for mean and covariance structure analysis with nonnormal missing data. Sociological Methodology. 2000;30(1):165–200. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.