Abstract

Objective:

The feasibility and 6-month outcome safety of lung transplants (LTs) from HCV-viremic donors for HCV-seronegative recipients (R-) were established in 2019, but longer-term safety and uptake of this practice nationally remain unknown.

Methods:

We identified HCV-seronegative LT recipients (R−) 2015–2020 using SRTR. We classified donors as seronegative (D−) or viremic (D+). We used Chi-square testing, rank-sum testing, and Cox regression to compare post-transplant outcomes between HCV D+/R− and D−/R− LT recipients.

Results:

HCV D+/R− LT increased from 2 to 97/year; centers performing HCV D+/R− LT increased from 1 to 25. HCV D+/R− vs. HCV D−/R− LT recipients had more obstructive disease (35.7% vs. 23.3%, p<0.001), lower lung allocation score (LAS, 36.5 vs. 41.1, p<0.001), and longer waitlist time (p=0.002). HCV D+/R− LT had similar risk of acute rejection (aOR 0.87, p=0.58), ECMO (aOR 1.94, p=0.10), and tracheostomy (aOR 0.42, p=0.16); similar median hospital stay (p=0.07); and lower risk of ventilator>48hrs (aOR 0.68, p=0.006). Adjusting for donor, recipient, and transplant characteristics, risk of all-cause graft failure (ACGF) and mortality were similar at 30 days, 1 year, and 3 years for HCV D+/R− vs. HCV D−/R− LT (all p>0.1), as well as for high- (≥20/year) vs. low-volume LT centers and high- (≥5/year) vs. low-volume HCV D+/R− LT centers (all p>0.5).

Conclusions:

HCV D+/R− and HCV D−/R− LT have similar outcomes at 3 years post-transplant. These results underscore the safety of HCV D+/R− LT and the potential benefit of expanding this practice further.

Keywords: Lung transplant, hepatitis C, outcomes, donor pool

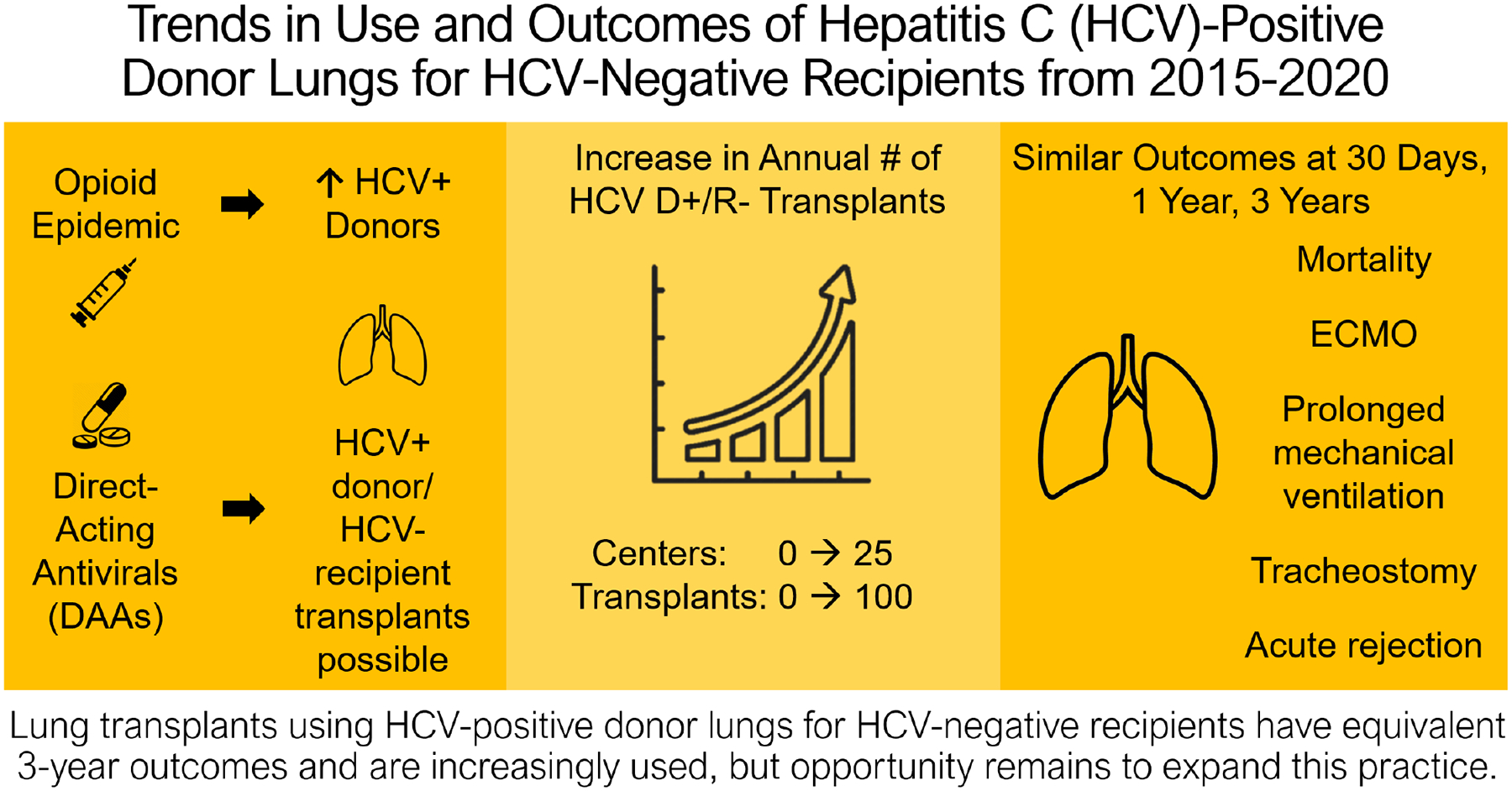

CENTRAL MESSAGE:

Lung transplants from donors with and without HCV viremia into recipients without HCV have similar risk of acute rejection, mortality, and all-cause graft failure at 3 years post-transplant.

CENTRAL PICTURE:

Mortality among U.S. Recipients of HCV-Viremic and HCV-Seronegative Lung Transplants

INTRODUCTION

As with other solid organs transplants, there are ongoing efforts to increase the pool of donor lungs available to transplant candidates to decrease waitlist time and mortality while maintaining survival benefit. While remarkable improvements have been made over the last decade, nearly 5,000 people remain on the lung transplant waitlist,1 and waitlist mortality for lung transplant candidates is 15.3% overall and higher in areas of low lung availability.2 Furthermore, the number of individuals added to the waitlist each year continues to rise.1 These circumstances underscore the need for continued reevaluation of potential donor organs to address the organ shortage.

In 2013, the introduction of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) to cure hepatitis C (HCV) infection reopened the possibility of using organs from HCV-viremic donors (D+) for HCV-seronegative recipients (R-).3, 4 HCV D+/R− cardiothoracic transplantation had previously been attempted, but this practice was stopped after studies showed approximately 3-fold higher risk of mortality.5, 6 Evidence of successful HCV D+/R− kidney transplants with sustained virologic response to DAAs7, 8 prompted reconsideration of this practice in cardiothoracic transplant. This is particularly relevant given increases in the HCV D+ population due to the opioid epidemic.9 A landmark study in 2019 by Woolley et al. found that HCV D+/R− heart and lung transplants were feasible and had similar short-term safety as HCV D−/R− transplants, but showed a potentially higher risk of acute rejection associated with HCV D+/R−.10 Evaluation of the same cohort of 44 patients at 12 months showed similar graft and patient survival but was limited by sample size.11 Other studies of HCV D+/R− transplants have found similar short-term outcomes.12–14 Based on this evidence, the ISHLT released an expert consensus statement regarding HCV D+/R− transplants that noted the benefit of these organs in terminally ill patients but noted the paucity of longer-term outcomes data, which limited their ability to gauge the safety of these transplants.15 It is unknown how this tempered enthusiasm for HCV D+/R− transplants has affected the uptake of this practice across transplant centers.

Using national registry data, we evaluated trends in the annual number of HCV D+/R− transplants and the number of transplant centers performing HCV D+/R− transplants (figure 6). We also compared outcomes of acute rejection, mortality, and all-cause graft failure to three years for HCV D+/R− vs HCV D−/R− lung transplants.

Figure 6.

Visual Abstract

METHODS

Data source

This study used data from the United States Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The SRTR data system includes data on all donors, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the U.S., submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors. These data have been described elsewhere.16 Variables available in the SRTR dataset can be viewed at https://www.srtr.org/requesting-srtr-data/saf-data-dictionary/.

Study population

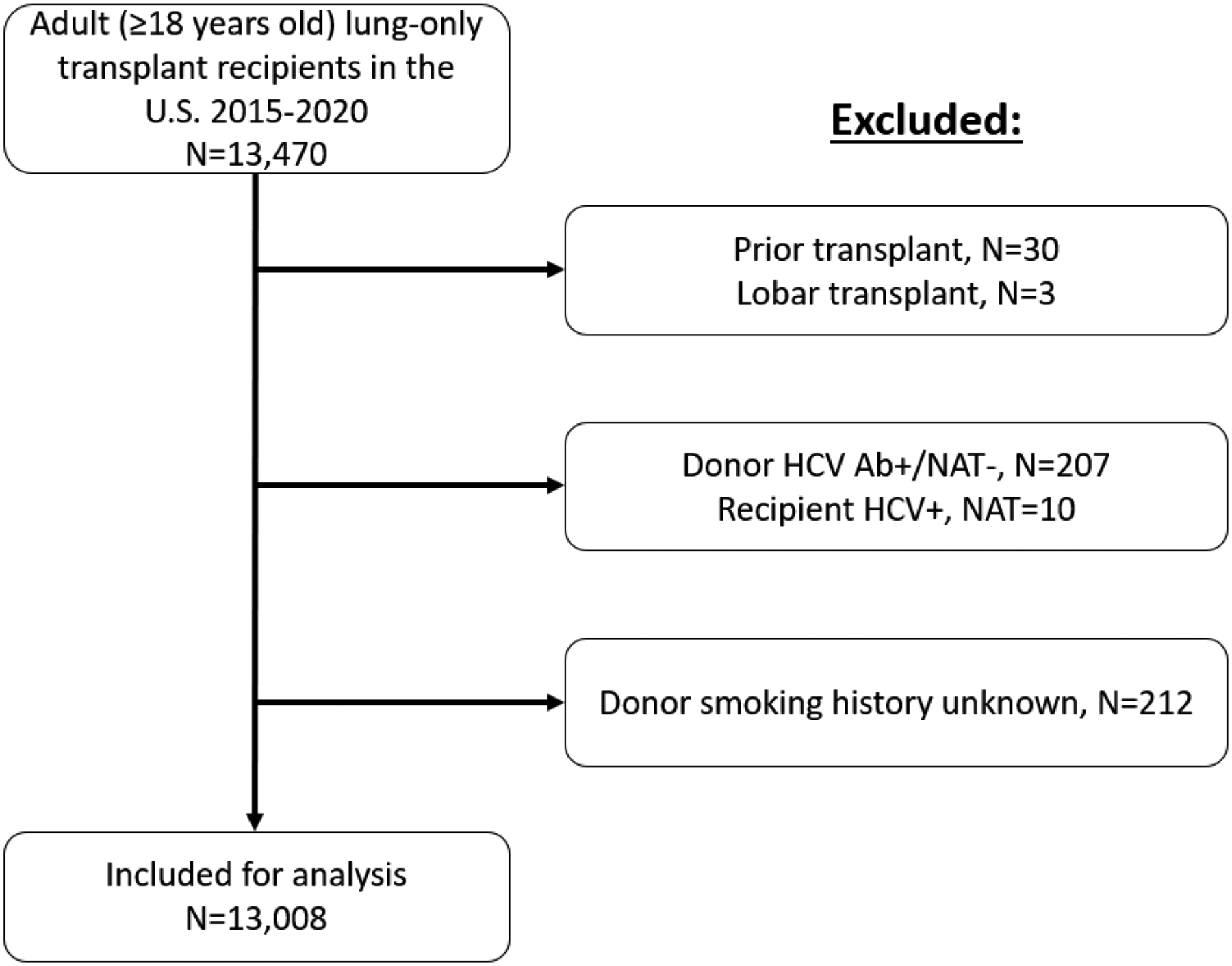

Using SRTR data, we identified all HCV-seronegative adult (≥18 years old) LT recipients (R-) in the United States from January 2015 through December 2020. We restricted our time period to 2020 to ensure that follow-up data were available for all transplants. We classified recipients as seronegative if they had a negative HCV antibody test. We then classified donors as seronegative (D−) or viremic (D+). Viremic donors had a reactive HCV nucleic acid test. We excluded donors who had a positive HCV antibody test but a negative HCV nucleic acid test. There were no transplants in which the donor or recipient HCV status was unknown. We excluded recipients of prior transplants or “lobar” lung transplants (Figure 1). This study was deemed exempt for the need for institutional review board approval by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board (NA_00042871).

Figure 1.

Identification of study population

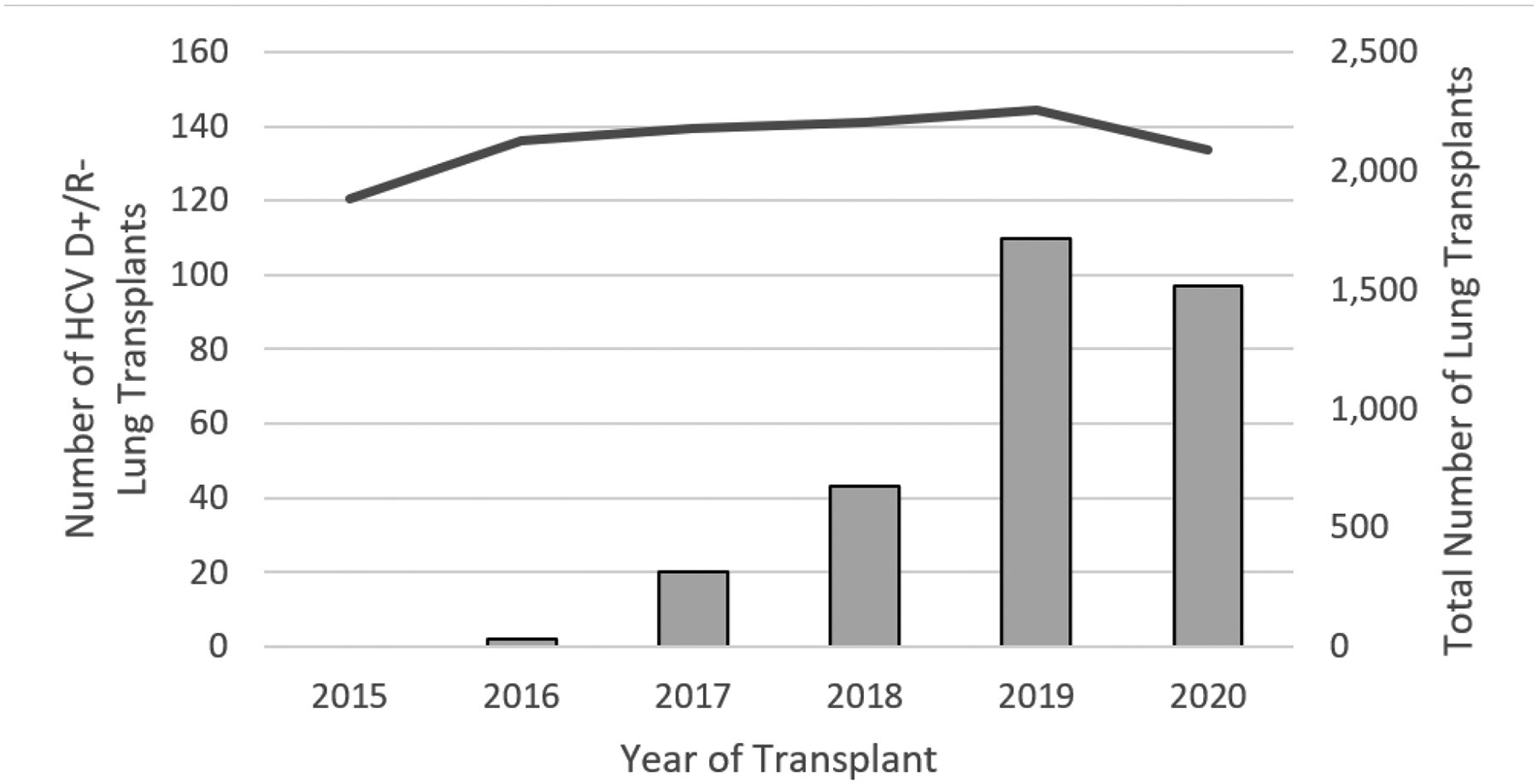

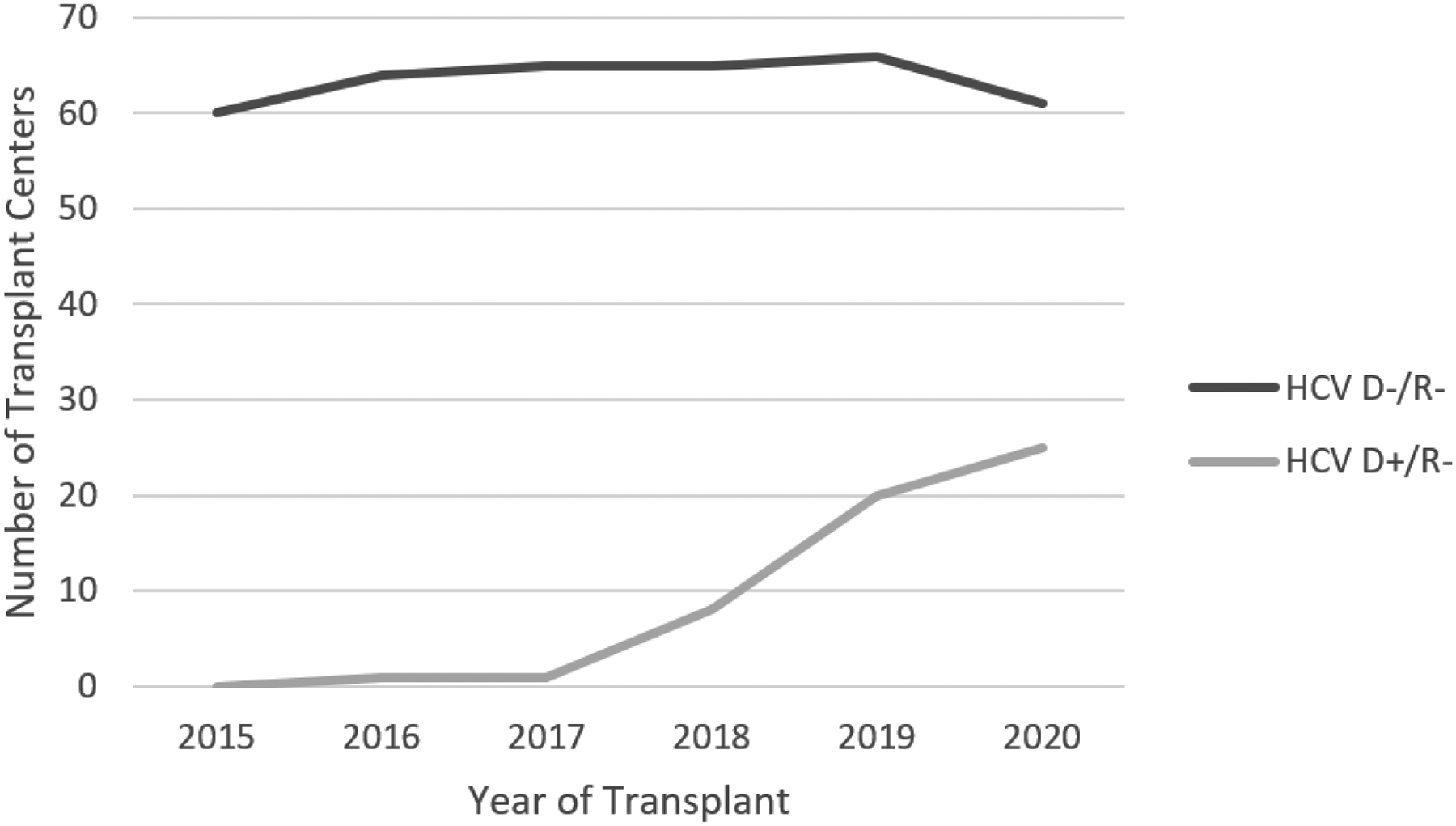

Temporal trends in use of lungs from HCV-viremic donors for transplant

We quantified the number of lung transplants from HCV-viremic donors to HCV-seronegative recipients (HCV D+/R−) performed in each year. We also quantified the number of centers performing HCV D+/R− lung transplants in each year. Transplant centers were defined as high-volume if they performed at least an average of 20 lung transplants per year during the study period. This cutoff was chosen because it has been used as a threshold to determine high-volume centers for both lung transplant and other complex thoracic surgeries.17, 18 Given the rapidly changing number of HCV D+/R− transplants by center, transplant centers were defined as high-volume for HCV D+/R− transplants if they performed at least 5 HCV D+/R− transplants in any year.

Donor and recipient characteristics

We compared the donor, recipient, and transplant characteristics of HCV D+/R− transplants and HCV-seronegative donor HCV-seronegative recipient (HCV D−/R−) transplants using Chis-quared and Wilcoxon rank-sum testing. We empirically included donor age, sex, race, and smoking history (≥ vs. <20 pack-years); recipient age, sex, race, and lung allocation score (LAS);19 and the type of transplant (unilateral vs. bilateral lung transplant) as covariates in our multivariable model. Of the empirically included covariates, only donor smoking history had missing values (N=212); these patients were excluded. Of note, waitlist time for recipients was unable to be separated into time before and after deciding to consider HCV-positive donor organ offers. Therefore, only total waitlist time is reported.

Post-transplant outcomes

We studied incidence of post-transplant outcomes including acute rejection, extracorporeal membranous oxygenation (ECMO), tracheostomy, prolonged ventilator support (>48 hours), length of stay, mortality, and all-cause graft failure (ACGF; ACGF is a composite of mortality, graft loss, or re-transplantation). In SRTR, mortality and graft loss are reported by individual transplant centers, and ascertainment is supplemented through linkage to the Social Security Master Death File (mortality) and the waiting list (graft loss).

For post-transplant outcomes available in SRTR as binary variables, including acute rejection, ECMO, prolonged ventilator support, and tracheostomy, we compared the proportion of HCV D+/R− and HCV D−/R− LT recipients who experienced the outcome during the study period using Chi-squared testing. For each outcome, sensitivity analysis was performed including only transplants since 2017 to reduce the likelihood that differences in accrued follow-up time between the groups affected results, as well as to ensure inferences remained the same after the national experience of the first two years of HCV D+/R− transplants (a management “learning curve” period). Post-transplant length of stay was analyzed as a continuous variable, with comparison of the distribution of length of stay between groups using Wilcoxon rank-sum testing.

For mortality and ACGF, we performed time-to-event analysis and visualized the incidence of each outcomes using Kaplan-Meier curves. We used Cox regression to compare the time to death or ACGF among HCV D+/R− vs. HCV D−/R− transplants, adjusting for donor, recipient, and transplant characteristics chosen a priori, as described above. As a sensitivity analysis, we also performed multilevel modeling to account for center-level clustering. We followed recipients until the outcome of interest or administrative censorship on February 28, 2022. For patients who died during the study period, cause of death was classified as due to graft failure, infection, cardiovascular, pulmonary, cerebrovascular, hemorrhagic, or other causes. Hepatitis C infection was not available as a cause of death, but both viral hepatitis and liver failure as causes of death were specifically evaluated. All analyses were performed using Stata 16.1/SE for Windows (College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Practice of HCV D+/R− lung transplantation

The first HCV D+/R− LT was performed in 2016. The number of HCV D+/R− LT increased from 2 in 2016 to 97 in 2020. From 2019–2020, 207 HCV D+/R− LT transplants were performed, representing 4.4% of all LT performed during that time period (Figure 2). The number of transplant centers performing HCV D+/R− LT increased over the same period, from 1 in 2016 to 25 in 2020 (Figure 3). In 2020, 41.0% of all the centers that performed LTs were also performing HCV D+/R− LT. Among high-volume LT centers, 20/43 (46.5%) performed HCV D+/R− LT. Among low-volume LT centers, 6/27 (22.2%) performed HCV D+/R− LT.

Figure 2.

Number of Lung Transplants from HCV-Viremic Donors for HCV-Seronegative Recipients Performed in the United States, by Year, 2015–2020

Figure 3.

Number of U.S. Transplant Centers Performing Lung Transplants from HCV-Viremic and HCV-Seronegative Donors into HCV-Seronegative Recipients, by Year, 2015–2020. Of note, the number of transplant centers performing HCV D−/R− lung transplants is equivalent to the total number of transplant centers performing lung transplants in a given year.

Study population

Donor age was similar between groups, while donors in HCV D+/R− LT were less likely to be male (52.6% vs. 60.8%, p=0.006) and more likely to be of white race (81.6% vs. 60.5%, p<0.001), to die of anoxic brain injury (69.1% vs. 29.2%, p<0.001), and have a ≥20 pack-year smoking history (16.9% vs. 7.3%, p<0.001; Table 1) than for HCV D−/R− LT.

Table 1.

Donor, Recipient, and Transplant Characteristics by Donor and Recipient HCV Status

| Characteristic | HCV D−/R− | HCV D+/R− | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 12,736 | 272 | |

| Donor Characteristics | |||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 33 (24, 47) | 32 (28, 38) | 0.18 |

| Male sex | 60.8% | 52.6% | 0.006 |

| White race | 60.5% | 81.6% | <0.001 |

| ≥20 pack-year smoking history | 7.3% | 16.9% | <0.001 |

| Donation after cardiac death (DCD) | 5.0% | 3.7% | 0.32 |

| Recipient Characteristics | |||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 61 (53, 67) | 61 (54, 67) | 0.58 |

| Male sex | 59.3% | 54.4% | 0.10 |

| White race | 78.6% | 84.9% | 0.04 |

| Blood type | |||

| O | 45.1% | 45.6% | >0.87 |

| A | 39.5% | 40.1% | |

| B | 11.4% | 11.4% | |

| AB | 4.0% | 2.9% | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Obstructive | 23.3% | 35.7% | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary vascular | 4.9% | 5.5% | |

| Cystic fibrosis and immunodeficiency | 8.9% | 4.0% | |

| Restrictive | 39.6% | 33.1% | |

| Other | 23.3% | 21.7% | |

| On ventilator pre-transplant | 5.0% | 2.6% | 0.07 |

| Waitlist time (days), median (IQR) | 48 (14, 149) | 57 (21, 203) | 0.002 |

| Lung allocation score, median (IQR) | 41.1 (35.2, 54.0) | 36.5 (33.8, 45.9) | <0.001 |

| Lung allograft ischemia time (hours), median (IQR) | 5.4 (4.4, 6.5) | 5.9 (4.9, 6.8) | <0.001 |

| Bilateral lung transplant | 73.9% | 82.7% | <0.001 |

HCV D−/R−: donor and recipient both HCV-seronegative

HCV D+/R−: HCV-viremic donor and HCV-seronegative recipient

Obstructive lung disease was more common among HCV D+/R− LT recipients (35.7% vs. 23.3%, p<0.001). Waitlist time was longer for HCV D+/R− LT recipients (median 57 vs. 48 days, p=0.002). Recipients of HCV D+/R− LT had a lower median LAS than recipients of HCV D−/R− LT (36.5 vs. 41.1, p<0.001) and were more likely to receive a bilateral lung transplant (82.7% vs. 73.9%, p=0.001). Donor allografts in HCV D+/R− transplants had a median ischemic time that was 26 minutes longer than for allografts in HCV D−/R− transplants (p<0.001). Recipient characteristics were otherwise similar between groups. Median (IQR) follow-up time was 3.1 (1.7, 4.7) years for HCV D−/R− transplants and 2.3 (1.6, 2.9) years for HCV D+/R− transplants.

Transplant hospitalization outcomes

Post-LT, the proportion of HCV D+/R− and HCV D−/R− LT recipients that required ECMO was similar (5.2% vs. 5.7%, p=0.72). The odds of post-LT ECMO were also similar for HCV D+/R− and HCV D−/R− LT (aOR 1.94, 95% CI 0.89–4.22, p=0.10) after adjusting for donor, recipient, and transplant characteristics. HCV D+/R− LT recipients were less likely to require prolonged ventilator support (29.9% vs. 38.7%, p=0.003); this inference remained unchanged in an adjusted model (HCV D+/R− vs. HCV D−/R−: aOR ventilator 0.68 [95% CI 0.52–0.89], p=0.006). HCV D+/R− LT recipients were less likely than HCV D−/R− recipients to require tracheostomy in an unadjusted analysis (1.1% vs. 3.6%, p=0.03); however, this difference was no longer significant in an adjusted model (aOR 0.43, 95% CI 0.13–1.39, p=0.16). These inferences were unchanged in a sensitivity analysis restricted to LT performed since 2017. Median (IQR) hospital length of stay was similar for HCV D+/R− and HCV D−/R− recipients [17 (12, 29) vs. 18 (12, 30) days, p=0.21]. This inference remained unchanged in an adjusted model (HCV D+/R− vs. HCV D−/R− LOS difference −3.8 days, 95% CI −7.9, 0.2, p=0.07). A sensitivity analysis restricted to LT performed since 2017 found that HCV D+/R− LT were associated with a 4.6 day-shorter length of stay (95% CI 0.4, 8.9 days, p=0.03).

Acute rejection

The proportion of recipients experiencing acute rejection was similar among HCV D+/R− and HCV D−/R− LT (7.0% vs. 7.9%, p=0.58). After adjusting for donor, recipient, and transplant characteristics, the odds of acute rejection were similar for HCV D+/R− and HCV D−/R− LT (aOR 0.87, 95% CI 0.54–1.41, p=0.58). A sensitivity analysis performed on LT since 2017 had similar results.

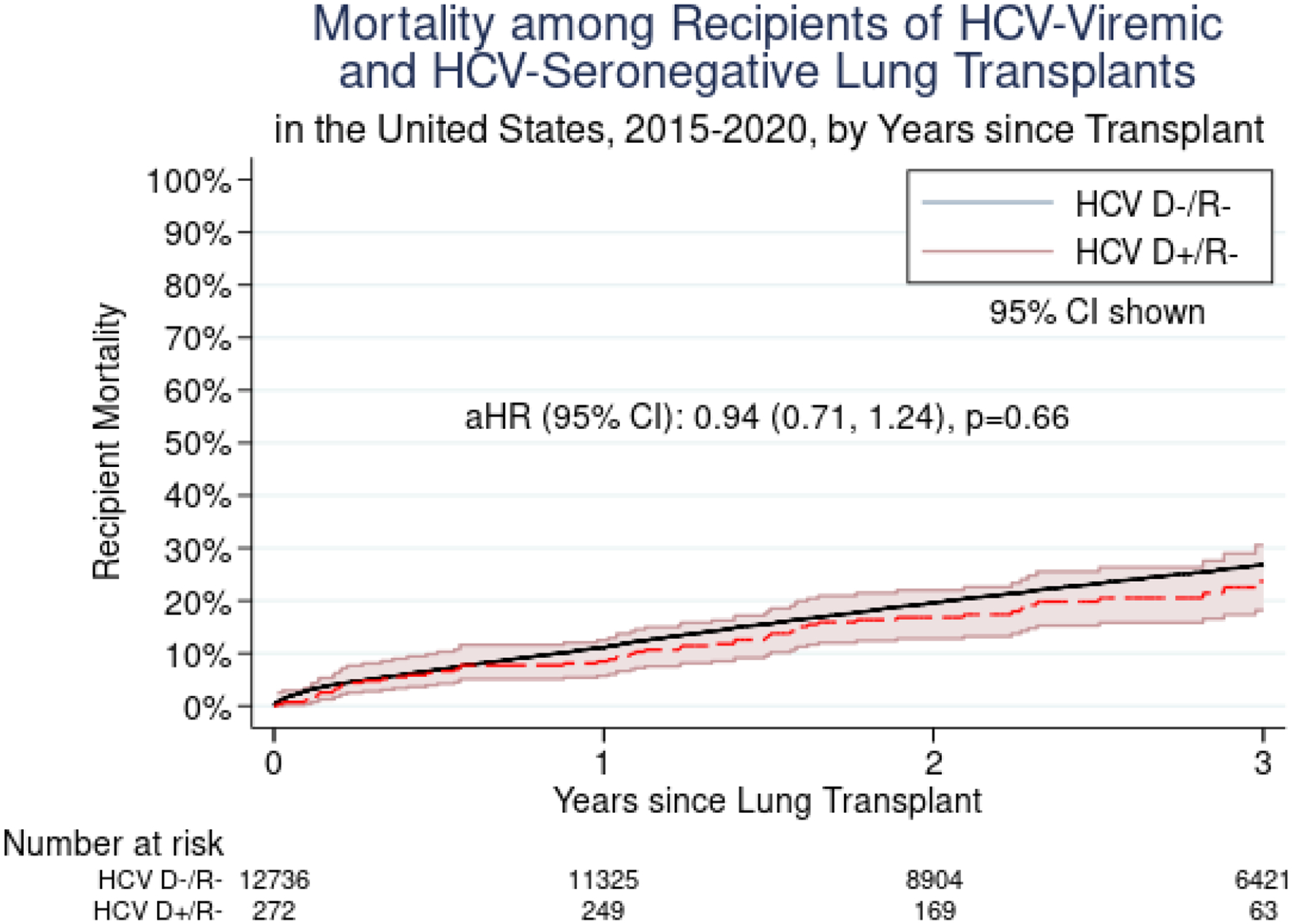

Mortality

The risk of mortality for HCV D+/R− vs. HCV D−/R− LT was similar at 30 days (aHR 0.32, 95% CI 0.08–1.28, p=0.11), 1 year (aHR 0.80, 95% CI 0.52–1.22, p=0.31), and 3 years (aHR 0.94, 95% CI 0.71–1.24, p=0.66) post-transplant after adjusting for donor, recipient, and transplant characteristics (Figure 4). There were no significant differences in mortality for HCV D+/R− LT when comparing centers performing ≥20 to <20 LT per year (HR 1.31, 95% CI 0.52–3.31, p=0.58), or when comparing centers that had performed ≥5 HCV D+/R− LT in a year to those that had lower HCV D+/R− LT volumes (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.39–1.94, p=0.74). A sensitivity analysis accounting for potential center-level clustering showed no difference in mortality between recipients of HCV D+/R− and HCV D−/R− transplants. There was no change in point estimates to suggest center-level effects on mortality.

Figure 4.

Mortality among Recipients of HCV-Viremic and HCV-Seronegative Lung Transplants in the United States, 2015–2020, by Years since Transplant

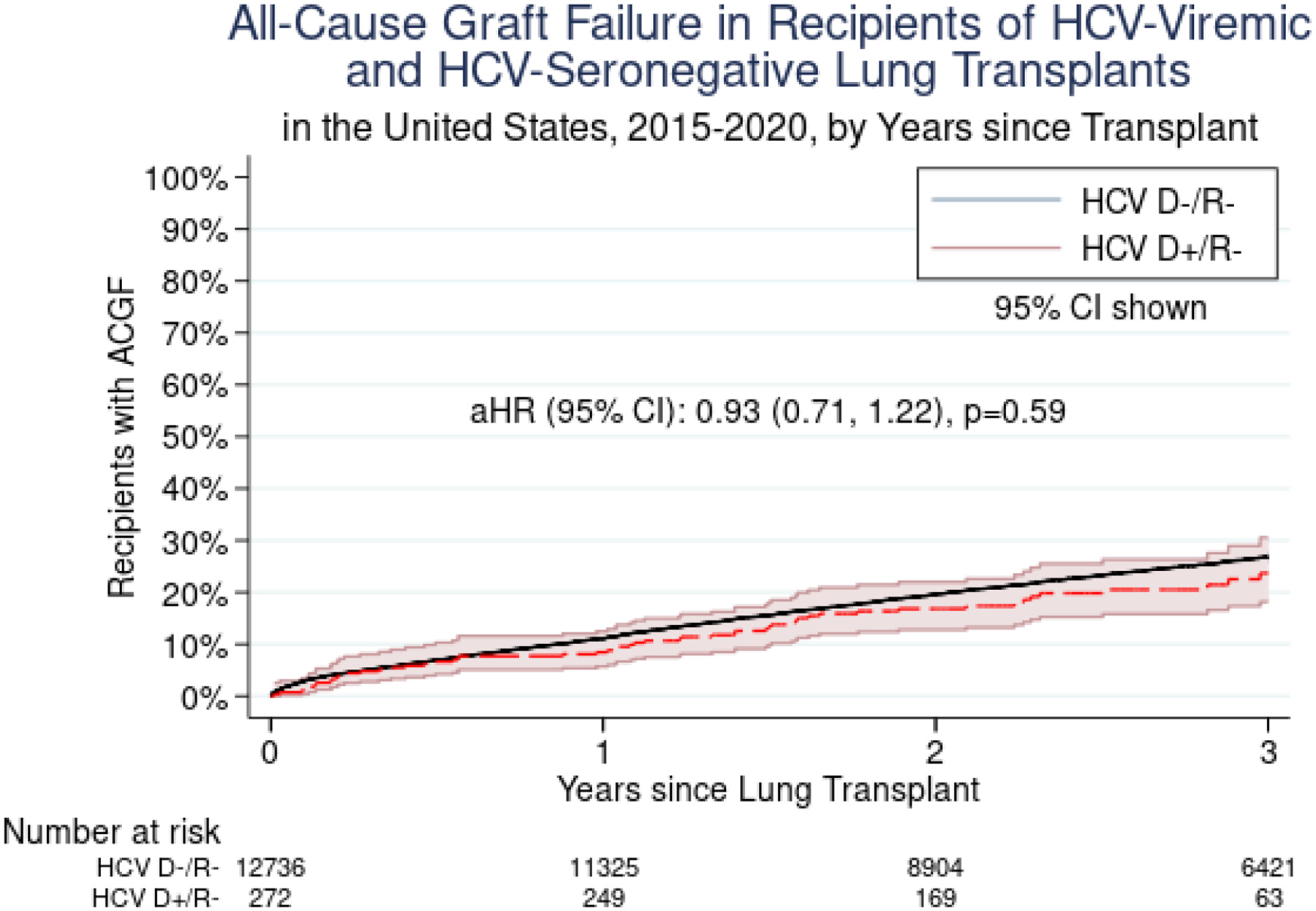

All-cause graft failure

The risk of ACGF for HCV D+/R− vs. HCV D−/R− LT was similar at 30 days (aHR 0.31, 95% CI 0.08–1.25, p=0.10), 1 year (aHR 0.80, 95% CI 0.53–1.22, p=0.30), and 3 years (aHR 0.93, 95% CI 0.71–1.22, p=0.59) post-transplant after adjusting for donor, recipient, and transplant characteristics (Figure 5). There were no significant differences in ACGF for HCV D+/R− LT when comparing centers performing ≥20 to <20 LT per year (HR 1.11, 95% CI 0.48–2.61, p=0.80), or when comparing centers that had performed ≥5 HCV D+/R− LT in a year to those that had lower HCV D+/R− LT volumes (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.41–2.02, p=0.81). A sensitivity analysis accounting for potential center-level clustering showed no difference in mortality between recipients of HCV D+/R− and HCV D−/R− transplants. There was no change in point estimates to suggest center-level effects on ACGF.

Figure 5.

All-Cause Graft Failure among Recipients of HCV-Viremic and HCV-Seronegative Lung Transplants in the United States, 2015–2020, by Years since Transplant

Cause of death

Of the 4,276 patients who died during the study period, 4,224 received HCV D−/R− transplants and 52 received HCV D+/R− transplants. Overall, 91.2% had an available cause of death. For those with an available cause of death, there were no significant differences in cause of death between recipients of HCV D+/R− and HCV D−/R− transplants (p=0.32). Causes of death included graft failure (HCV D+/R− vs. HCV D−/R− 17.5% v. 8.7%), infection (16.9% vs. 19.6%), cardiovascular (8.4% vs. 8.8%), pulmonary (20.8% vs. 23.9%), cerebrovascular (3.4% vs. 6.5%), hemorrhagic (1.9 vs. 4.4%), and other (32.1% vs. 28.3%). No patients had viral hepatitis listed as a cause of death. A total of 25 patients (0.2%) had liver failure as a cause of death, all of whom had received HCV D−/R− transplants.

DISCUSSION

In this national study of utilization and mid-term outcomes of HCV D+/R− lung transplants, we found that the number of HCV D+/R− transplants has risen almost exponentially since 2016, as has the number of centers performing HCV D+/R− lung transplants. Compared to HCV D−/R− lung transplants, HCV D+/R− transplants had statistically similar risk of mortality and ACGF at 30 days, one year, and three years post-transplant and of acute rejection, post-transplant ECMO, and tracheostomy. Additionally, HCV D+/R− transplant recipients had similar hospital length of stay overall, but a significantly shorter hospital length of stay for LT performed since 2017, compared to HCV D−/R− transplant recipients. These findings demonstrate favorable outcomes and mid-term safety of HCV D+/R− transplants and an encouraging uptake of this practice by transplant centers.

Our finding that HCV D+/R− lung transplants have similar mid-term outcomes to HCV D−/R− transplants is highly encouraging and consistent with literature on HCV D+/R− vs. D−/R− kidney transplants.20, 21 While this technique was pioneered in kidney and liver transplants, all solid organ transplants face a similar shortage of donors to treat growing candidate waitlists and benefit from this expansion of the donor pool. Still, the use of HCV D+/R− transplants remains novel for all types of solid organ transplant and longer-term outcomes should continue to be monitored, particularly in organs such as kidney and liver with median graft survivals greater than 10 years. Our finding that HCV D+/R− LT had equivalent outcomes despite a 26-minute longer median ischemic time might reflect higher HCV D+ vs. D− organ quality; this warrants further study in a database with more granular donor organ quality information. Additionally, we observed a higher percentage of HCV-viremic vs. HCV-seronegative donors with a ≥20-pack year smoking history (16.9% vs. 7.3%, p<0.001) without evidence of negative effect on recipient transplant outcomes. While the impact of donor smoking history on recipient outcomes is controversial in the overall lung transplant population,22–26 our findings suggest that the overall quality of HCV-viremic donor organs support their continued use even in the setting of donor smoking history. Observed differences in cause of death between HCV D+R− and HCV D−/R were not significant, but the low number of deaths among recipients of HCV D+/R− transplants indicates that ongoing monitoring is warranted.

We found that waitlist time was longer for HCV D+/R− recipients than for HCV D−/R− recipients. This contrasts with the shorter waitlist times for HCV D+/R− recipients reported in prior literature.27, 28 However, this likely reflects differences in measurement of waitlist time; we only had access to overall waitlist time, not waitlist time since decision to consider HCV D+ organ offers. Therefore, our findings likely indicate that patients who had been on the waitlist longer were more likely to consider HCV D+/R− transplants, particularly since the recipients of HCV D+/R− LT had longer waitlist times and lower LAS scores than recipients of HCV D−/R− LT. This is also consistent with interviews with HCV D+/R− lung transplant recipients that said they made the decision to broaden their donor acceptance criteria because of desperation and increasing symptom severity.29 This might reflect a strategy of HCV D+ organ utilization for those likely to accrue more waitlist time before becoming critically ill enough to receive organ offers.

While broadening the donor pool should increase the number of transplants, there has been disagreement over the true impact of using HCV D+/R− transplants on national transplant volume. Models in Italy suggested a low rate of suitable lungs,30 but models using the US population suggest increased transplant volume and better waitlist outcomes.31 When modeling the impact of all candidates accepting potential HCV-positive donor offers from 2014–2019, Wayda et al. estimated an increase of 232 transplants, 132 fewer delistings due to health deterioration, and 50 fewer waitlist deaths during that 5-year period. This would have reduced waitlist times by 3–11%, depending on priority status.31 Since both the number of waitlist candidates and the number of annual lung transplants have increased since that time,1 the impact in the current era could be even greater. Evidence suggests that the interest in HCV D+ organ offers has increased despite concerns about stigma; Yuan et al. found that DAAs have caused a 2.1-fold increase per year in waitlist candidate willingness to accept HCV D+/R− transplants.32 Additionally, interviews of candidates who indicated willingness to accept an HCV D+/R− transplant reported they felt it would be very safe, regardless of the type of transplant they ended up receiving.29

One of the greatest perceived obstacles to expanding the use of HCV D+/R− transplants is the availability and cost of DAAs. Several studies have found that the cost of these medications has been a barrier to insurance approval, with up to 95% requiring prior authorization and 24–35% requiring appeals to obtain insurance coverage.33, 34 However, in both studies, insurance coverage was eventually obtained for all patients, and out-of-pocket cost was reduced to a median of $0–10 through patient assistance programs.33, 34 In models, DAA therapy and HCV-related care were estimated to account for 11% of the cost of a HCV D+/R− transplant.31 Studies of the cost effectiveness of HCV D+/R− transplants in Australia identify significant cost savings per patient at multiple levels of DAA cost, suggesting a cost benefit in other health care systems.35 However, studies of the cost effectiveness of HCV D+/R− transplants in the United States are needed to aid advocacy efforts for insurance coverage of DAAs for HCV D+/R− transplant recipients. Additionally, exploration of methods that shorten the necessary duration of DAA therapy, such as prophylaxis7 or the ezetimibe-DAA combination therapy suggested by Feld et al.,13 or even eradicate HCV from the donor organ prior to transplantation using sterilization or viral load techniques during ex-vivo lung perfusion12, 36 could reduce HCV-related costs of HCV D+/R− transplants and increase uptake of and access to these transplants. As noted by Nangia et al., the ethical permissibility of HCV D+/R− organ transplantation relies on access to post-transplant curative DAA therapy.37 The ongoing use of HCV D+/R− organ transplantation also requires close monitoring for any other postoperative effects of HCV-viremic organs – particularly when administration of DAAs is delayed to the outpatient setting – or administration of DAAs in this patient population whose pharmacotherapy is already complex.

An additional barrier to expanding the use of HCV D+/R− transplants might be center discomfort with the post-transplant care of these patients. At our center, we performed 15 HCV D+/R− transplants from 2019–2020; this represented 25% of our center’s lung transplant volume in those years. Unadjusted one-year survival is similar among recipients of HCV D+/R− and HCV D−/R− lung transplants (93.3% vs. 91.9%). This is accomplished through a clear treatment protocol. Recipients of HCV D+/R− lung transplants receive a Transplant Infectious Disease consult, all Public Health Service Increased Risk Donor testing, and additional laboratory serologies including a hepatitis C quantitative PCR weekly for the first twelve weeks. A positive assay results in referral to the Transplant Infectious Disease service for testing (including HCV genotyping), management, and treatment. Treatment of viremia is prescribed by the transplant physician or transplant infectious disease specialist according to the most recent guidelines for a particular HCV genotype (see www.hcvguidelines.org). Lung transplant recipients with HCV viremia who remain in patient past post-transplant day 14 will commence HCV treatment in the inpatient setting, while patients discharged by that time commence HCV treatment as outpatients. Monitoring while on HCV therapy includes monthly HCV PCR and CMP. An additional source of discomfort caring for these patients is concern about risk to health care personnel. However, recent data estimates this risk of infection transmission at 0.2% for those exposed to HCV-antibody-positive blood through needlestick or sharps injury.38, 39

Our ability to study HCV D+/R− transplants in the United States was limited by the information available in the SRTR database, which might not include all variables considered by transplant centers, providers, and candidates when accepting an offer. Therefore, our evaluations of transplant decision-making must be made at the center and national levels. While these data include all lung transplants performed in the United States, the recent uptake of HCV D+/R− transplants results in a limited sample size and follow-up time with which to draw conclusions about the mid-term results of HCV D+/R− transplants. We therefore encourage ongoing evaluation of these outcomes as the number of transplants and duration of follow-up increase. Finally, the development of new medications and/or treatment regimens for HCV, which are ongoing, may affect the outcomes and cost of HCV D+/R− transplants and should be evaluated when sufficient data are available.

In conclusion, our findings underscore the mid-term safety of HCV D+/R− lung transplants and potential benefit of expanding the utilization of these donor lungs further. The growing evidence of the safety of HCV D+/R− lung transplants should be disseminated through educational campaigns to ensure maximum waitlist candidate access to these life-saving transplants.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVE STATEMENT:

Hepatitis C-viremic donors represent a growing portion of the donor pool, mostly due to intravenous drug abuse associated with the ongoing opioid epidemic. Understanding the long term safety of lung transplants from hepatitis C-viremic donors into hepatitis C-seronegative recipients is critical to encourage uptake of this practice, which will further expand the donor pool and access to transplantation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grant number F32-AG067642091A1 (Ruck) from the National Institute of Aging (NIA) and K24-AI144954-08 (Segev) from The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID). The analyses described here are the responsibility of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

The data reported here have been supplied by the Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute (HHRI) as the contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the U.S. Government.

GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS:

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- NIA

National Institute of Aging

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

- HHRI

Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute

- LT

lung transplant

- R−

HCV-seronegative recipient

- D−

HCV-seronegative donor

- D+

HCV-viremic donor

- ECMO

extracorporeal membranous oxygenation

- ACGF

all-cause graft failure

- ISHLT

International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation

- HRSA

Health Resources and Service Administration

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- LAS

lung allocation score

- IQR

interquartile range

- HR

hazard ratio

- DAAs

direct-acting antivirals

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

IRB Number: NA_00042871

REFERENCES

- 1.Valapour M, Lehr CJ, Skeans MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2019 Annual Data Report: Lung. American Journal of Transplantation. 2021;21:441–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kulkarni HS, Korenblat KM, Kreisel D. Expanding the donor pool for lung transplantation using HCV-positive donors. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:S1942–s1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Approval of Victrelis (boceprevir) a direct acting antiviral drug (DAA) to treat hepatitis C virus (HCV). In: Administration UFaD, ed2013.

- 4.Approval of Incivek (telaprevir) a direct-acting antiviral (DAA) to treat hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. In: Administration UFaD, ed2013.

- 5.Haji SA, Starling RC, Avery RK, et al. Donor hepatitis-C seropositivity is an independent risk factor for the development of accelerated coronary vasculopathy and predicts outcome after cardiac transplantation. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2004;23:277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koenig A, Stepanova M, Saab S, Ahmed A, Wong R, Younossi ZM. Long-term outcomes of lung transplant recipients with hepatitis C infection: a retrospective study of the U.S. transplant registry. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2016;44:271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durand CM, Bowring MG, Brown DM, et al. Direct-Acting Antiviral Prophylaxis in Kidney Transplantation From Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Donors to Noninfected Recipients: An Open-Label Nonrandomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:533–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg DS, Abt PL, Blumberg EA, et al. Trial of Transplantation of HCV-Infected Kidneys into Uninfected Recipients. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376:2394–2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durand CM, Bowring MG, Thomas AG, et al. The Drug Overdose Epidemic and Deceased-Donor Transplantation in the United States: A National Registry Study. Ann Intern Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woolley AE, Singh SK, Goldberg HJ, et al. Heart and Lung Transplants from HCV-Infected Donors to Uninfected Recipients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1606–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woolley AE, Piechura LM, Goldberg HJ, et al. The impact of hepatitis C viremic donor lung allograft characteristics on post-transplantation outcomes. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2020;9:42–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cypel M, Feld JJ, Galasso M, et al. Prevention of viral transmission during lung transplantation with hepatitis C-viraemic donors: an open-label, single-centre, pilot trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feld JJ, Cypel M, Kumar D, et al. Short-course, direct-acting antivirals and ezetimibe to prevent HCV infection in recipients of organs from HCV-infected donors: a phase 3, single-centre, open-label study. The lancet. Gastroenterology & hepatology 2020;5:649–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li SS, Osho A, Moonsamy P, et al. Outcomes of Lung Transplantation From Hepatitis C Viremic Donors. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aslam S, Grossi P, Schlendorf KH, et al. Utilization of hepatitis C virus-infected organ donors in cardiothoracic transplantation: An ISHLT expert consensus statement. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2020;39:418–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Massie AB, Kuricka LM, Segev DL. Big Data in Organ Transplantation: Registries and Administrative Claims. American Journal of Transplantation. 2014;14:1723–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel DC, Jeffrey Yang CF, He H, et al. Influence of facility volume on long-term survival of patients undergoing esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022;163:1536–1546.e1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss ES, Allen JG, Meguid RA, et al. The impact of center volume on survival in lung transplantation: an analysis of more than 10,000 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1062–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whited WM, Trivedi JR, van Berkel VH, Fox MP. Objective Donor Scoring System for Lung Transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107:425–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Potluri VS, Goldberg DS, Mohan S, et al. National Trends in Utilization and 1-Year Outcomes with Transplantation of HCV-Viremic Kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30:1939–1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reese PP, Abt PL, Blumberg EA, et al. Twelve-Month Outcomes After Transplant of Hepatitis C-Infected Kidneys Into Uninfected Recipients: A Single-Group Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiavon M, Lloret Madrid A, Lunardi F, et al. Short- and Long-Term Impact of Smoking Donors in Lung Transplantation: Clinical and Pathological Analysis. Journal of clinical medicine. 2021;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okahara S, Levvey B, McDonald M, et al. Influence of the donor history of tobacco and marijuana smoking on early and intermediate lung transplant outcomes. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2020;39:962–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonser RS, Taylor R, Collett D, Thomas HL, Dark JH, Neuberger J. Effect of donor smoking on survival after lung transplantation: a cohort study of a prospective registry. Lancet. 2012;380:747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cypel M, Keshavjee S. Expansion of the donor lung pool: use of lungs from smokers. The Lancet. 2012;380:709–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taghavi S, Jayarajan S, Komaroff E, et al. Double-lung transplantation can be safely performed using donors with heavy smoking history. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:1912–1917; discussion 1917–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gernhofer YK, Brambatti M, Greenberg BH, Adler E, Aslam S, Pretorius V. The impact of using hepatitis c virus nucleic acid test-positive donor hearts on heart transplant waitlist time and transplant rate. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2019;38:1178–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schlendorf KH, Zalawadiya S, Shah AS, et al. Early outcomes using hepatitis C-positive donors for cardiac transplantation in the era of effective direct-acting anti-viral therapies. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2018;37:763–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Humar SS, Pinzon N, Cypel M, Abbey S. Lung transplant recipient attitudes and beliefs on accepting an organ that is positive for hepatitis C virus. Transplant infectious disease : an official journal of the Transplantation Society. 2021;23:e13684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solli P, Dolci G, Ranieri VM. The new frontier of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-mismatched heart and lung transplantation. Annals of translational medicine. 2019;7:S279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wayda B, Sandhu AT, Parizo J, Teuteberg JJ, Khush KK. Cost-effectiveness and system-wide impact of using Hepatitis C-viremic donors for heart transplant. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2022;41:37–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan Q, Cui H, Leya GA, et al. Temporal trends and impact of willingness to accept organs from donors with hepatitis C virus. Transpl Int. 2021;34:2562–2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bova S, Cameron A, Durand C, et al. Access to direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C-negative transplant recipients receiving organs from hepatitis C-viremic donors. American journal of health-system pharmacy : AJHP : official journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edmonds C, Carver A, DeClercq J, et al. Access to hepatitis C direct-acting antiviral therapy in hepatitis C-positive donor to hepatitis C-negative recipient solid-organ transplantation in a real-world setting. American journal of surgery. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott N, Snell G, Westall G, et al. Cost-effectiveness of transplanting lungs and kidneys from donors with potential hepatitis C exposure or infection. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ribeiro RVP, Ali A, Cypel M. Ex vivo perfusion in lung transplantation and removal of HCV: the next level. Transpl Int. 2020;33:1589–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nangia G, Borges K, Reddy KR. Use of HCV-infected organs in solid organ transplantation: An ethical challenge but plausible option. Journal of viral hepatitis. 2019;26:1362–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Egro FM, Nwaiwu CA, Smith S, Harper JD, Spiess AM. Seroconversion rates among health care workers exposed to hepatitis C virus-contaminated body fluids: The University of Pittsburgh 13-year experience. American journal of infection control. 2017;45:1001–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hepatitis C Questions and Answers for Health Professionals. Viral Hepatitis. Vol 2022: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.