Abstract

Background

Different materials can be used in filling the extraction socket to achieve an alveolar ridge preservation. The present study compared the wound healing potential and pain management efficacy of the collagen and the xenograft bovine bone, covered by a cellulose mesh, inserted into the socket of extracted teeth.

Materials and Methods

Thirteen patients were willingly chosen to enter our split-mouth study. It was a clinical trial of crossover design with a minimum of two teeth to be extracted for each patient. Randomly, one of the alveolar sockets was filled with collagen material as Collaplug®, and the second alveolar socket was filled with xenograft bovine bone substitute Bio-Oss® and covered with a cellulose mesh Surgicel®. Post-extraction follow-up was observed at day 3, 7 and 14, and each participant was told to document his/her pain experience in our prepared Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) document for 7 consecutive days.

Results

Clinically, the differential wound closure potential between the two groups was significant in the buccolingual (P = 0.045) but not significant in the mesiodistal (P = 0.204) mouth areas. The pain expressed as rated in the NRS was higher in the case of the Bio-Oss®, but there was no significant difference upon comparing the two procedures for 7 consecutive days (P = 0.397) except on day 5 (P = 0.004).

Conclusions

Collagen appears to support faster wound healing rate, higher potential influence on socket healing and decreased pain perception than xenograft bovine bone.

Keywords: Collagen, Xenograft bovine bone, Tooth extraction, Pain, Wound closure

Introduction

After loss of their deciduous teeth and eruption of the permanent ones, patients are subjected again to tooth loss as a result of deep fracture, huge decay, orthodontic treatment and different pathological reasons [1]. Extraction of non-restorable teeth still has its importance in the dental field [2].

Tooth extraction is a process that causes the loss of a tooth and a part of the bony volume around it. The socket undergoes a physiological remodeling process leading to a new shape of the soft tissues following the decrease in the bone volume [3].

Fourteen days after tooth extraction, the socket will lose all the fibers of the periodontal ligament, the blood supply and the buccal bundle bone that were attached to the extracted tooth [4]. Three months after extraction, the socket will present an average loss of 3.87 mm in width and 2.03 mm in height [3]. Twelve months later, according to Schropp et al., the socket will be affected by the biggest loss of the bone volume, losing 50% of its width [5]. After bone resorption and soft tissues reshaping, restorative, prosthetic and implant treatments will be more complex with less options [6]. Clinicians try to reduce this process by protecting the blood clot formation or filling the socket using different materials and techniques like the alveolar ridge preservation [7]. Those techniques will attempt to preserve the socket shape from the day of extraction, thus minimizing its resorption.

Post-extraction changes should be minimized in order to achieve implant or prosthetic rehabilitation with an optimal esthetic result. A systematic literature review of alveolar ridge preservation techniques reported the use of different materials such as autogenous grafts, allografts and xenografts [8]. In a recent randomized controlled trial [9], the collagen material had been introduced, for the first time as a material for ridge preservation. Several reports mentioned that collagen plug might prevent complications such as bleeding and infection after tooth extraction [10]. In 2015, Abdelaziz et al. showed that collagen plug has a hemostatic property and accelerates the soft tissues healing procedure in patients taking oral anticoagulant medication [11]. After tooth extraction, the collagen plug will act as a scaffold for the migration of mesenchymal cells and as a barrier leading to tissue engineering; the collagen is essential for the support of the tissues [12].

In dentistry, the use of bone substitutes aims to regenerate or to fill defected bone areas. The xenograft, one of the bone substitutes, is a low resorbable material and has an osteoconductive property [13]. This bovine or porcine origin material [14] is frequently used in ridge preservation techniques. The frequent use of xenograft material is due to its easy handling and wide availability. The bovine graft named demineralized bovine bone is free from its organic minerals and is more used than the porcine graft [15]. Many studies have assessed the use of xenografts [15] where Bio-Oss® was most commonly used and processed to mimic natural bone without the organic phase [16]. In a histological study on humans, the results confirmed that by inserting the xenograft bone as biomaterial into the socket, the healing was delayed, but the dimensions of the socket and the ridge were preserved when compared to a non-grafted socket [17].

The collagen material, used for ridge preservation, is fully resorbable and biocompatible and allows for a new formed bone in the socket [11].

Pain will be present after tooth extraction. Pain management is important since it can give an idea about the patient’s attitude toward any surgical treatment by using scales. The Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) has good sensitivity and generates data that can be statistically analyzed for audit purposes” [18]. In the literature, many methods have been described for the management of pain including the Verbal Rating Scale (VRS), the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and the NRS [19].

The aim of this study was to compare the healing rate and pain perception supported by collagen plug, a degraded material [20], and the xenograft bovine bone, a slowly degraded bone substitute [21], as materials used in ridge preservation techniques. Our hypothesis was that collagen might ensure faster wound healing potential but lower pain perception than xenograft.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study was a split-mouth clinical trial of crossover design, approved by the scientific and ethical committee of the Neuroscience Research Center (NRC) at the Lebanese University, Beirut, Lebanon. The recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975) for human subjects, involved in biomedical research as revised in 2013 in its seventh revision, were adopted. We had chosen a fixed place for the surgery for all patients, with the same kind of instruments and the same clinician to eliminate all the variables interfering with our experiment. The patients were given almost the same environment for the study. The surgeries were made by the same surgeon.

A consent form containing procedures, benefits and precautions of the present work was carefully read explained and signed by each patient.

Patients’ Selection

Since the pain management and the wound healing rate are subjective for each patient, we have thus chosen to compare the two materials in sockets in the same jaw for each patient.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All patients were included consecutively between May 2019 till June 2019. All included patients were 18 years old and above and had a minimum of two teeth to be extracted in the same jaw.

The causes of teeth extraction were indeed either severe decay, deep fracture, periodontal disease or orthodontic treatment, and the teeth had a remaining half of the periodontal support.

No active lesions or pus were present on the roots of the extracted teeth or in the surrounding areas. A minimum of two teeth were in need to be extracted in the same jaw for each patient.

Patients with a history of systemic diseases like hyperthyroidism, uncontrolled diabetes, smoking, active pathology or uncontrolled periodontal disease were excluded from the study.

Moreover, the patient should have no interference with the healing process. The patient does not take bisphosphonates, has no addiction on drug or alcohol, has no history of xenograft or collagen rejection and does not have allergy neither on the materials used in the study techniques, nor on the medication given after the surgical procedures.

Surgical Extractions

The extractions were atraumatic, conserved the four bony walls of the socket and separated by 2 weeks (Figs. 1, 2).

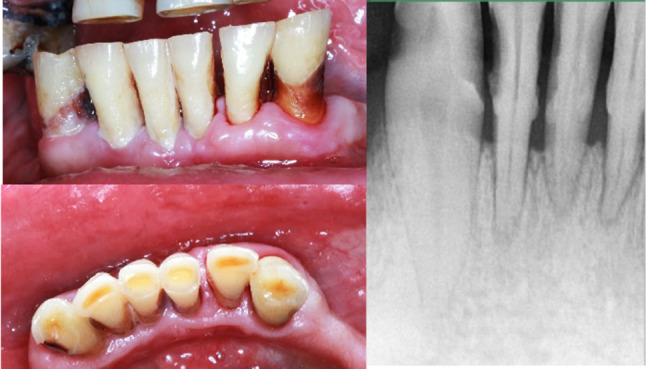

Fig. 1.

Selection of two anterior teeth on the same side of the mandible. On the left, the clinical aspect is shown and the related X-ray is on the right

Fig. 2.

Selection of two molars on the two sides of the maxilla. In the center, the clinical aspect is shown and the related X-rays are on the right and the left

Before the surgery procedure was performed, all patients underwent a prophylaxis session and were given Paroex® (Sunstar GUM, Germany) which is a mouthwash containing 0.12% of chlorhexidine diclocunate and cetylpiridinium chloride with 0% alcohol to use it 3 times a day for 1 week.

At the day of the first extraction, randomly one site was chosen to do the extraction with one of the described materials, and based on allocation concealment, the site of the lower tooth number was chosen as the first technique to be made. An envelope was then opened to choose one of the two adopted techniques. Moreover, the patient was not informed by the surgeon about the exact technique used in the session. All patients were expected to have no pain before starting the procedure, and this was essential for precise results in the pain scale later on. This was indeed clearly noted for obtaining the number 0 on the pain scales of our patients before giving them the anesthesia.

A local analgesia was given, using Septanest® (Septodont, France), which contains articaine hydrochloride with 1:100,000 adrenaline.

A minimally flapless invasive extraction was made taking care of the surrounding soft and hard tissues. We used a surgical blade (No. 15c) for intra sulcular incisions to preserve the papillae and the gingival margins. The teeth included in the study had either one root or multiple roots. We used periotomes to cut the fibers in the periodontium and small straight elevators to mobilize the tooth. Then, by using adequate forceps, we made slow and limited movements of rotation, and we pulled out the tooth from the socket with minimum damage to the surrounding soft and hard tissues (Fig. 3a–d). When a retention was preventing the extraction of teeth with multiple roots, we sectioned the teeth using carbide burs on a high-speed turbine preserving as much as possible the surrounding bone and soft tissues, and the roots were finally pulled out with minimum damage. We used small curettes to eliminate all the remaining fibers of the periodontal ligament and the granulation tissues. The remaining bony walls were checked using a probe. Finally, we irrigated the socket by a sodium chloride solution to be ready to receive the grafting material.

Fig. 3.

Atraumatic extraction of one root. a A lower left canine partially pulled out from the socket atraumatically, b a lower right canine showing its atraumatic extraction, we can see the conservation of the soft tissues around it, c minimum damage to the surrounding tissues at the lower left canine area showing the clean socket without any remaining tooth pieces, d the socket of the lower right canine filled with blood with healthy surrounding tissues

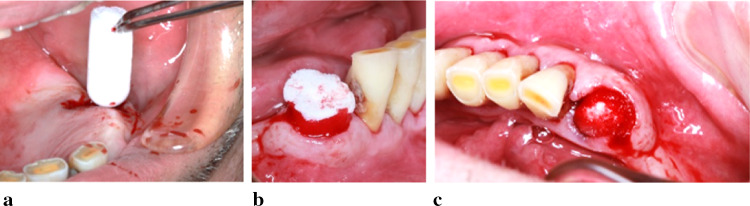

In the first group, the socket was filled with Collaplug® (Zimmer Biomet dental, USA) that contains bovine collagen type I extracted from the achilles tendons. The material is a kind of nonfriable white sponge that has high porosity and softness, controls bleeding, protects and stabilizes the wound blood clot. We used the (10 mm × 20 mm) piece that will resorb in 10 to 14 days. The Collaplug® was inserted into the socket to fill it completely at the level of the soft tissues closing all the gap done by the extraction and reshaped to cover the socket (Fig. 4). In case of multiple root structure, the plug was sectioned and all the parts were inserted into the gaps of the roots (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Handling and insertion of one piece of Collaplug® into the socket. a We can see the insertion of the Collaplug® with a forceps without the need of shaping it. In b, we see clearly the Collaplug® inserted into the socket with the blood entering into its white material, while in c we can see that the Collaplug® filled the entire socket to the level of the soft tissues with blood all around and inside it

Fig. 5.

Sectioning of the Collaplug to fill the holes of the multiple roots and insertion into the socket. In a, we sectioned the Collaplug® in a way to have a shape like the gap of each root. In b, we can see the Collaplug® parts while being inserted into the socket confirming its right volume, while in c all the parts inserted to the level of the soft tissues are shown well embedded by blood from the socket and thus closing all the gaps of the roots

When there was not enough bleeding from the socket, a curettage was made before the insertion of the Collaplug®, so it would be filled with enough blood for the clot formation.

In the second group, the socket was filled with Bio-Oss®, (Geistlich, Switzerland) covered by a cellulose mesh, Surgicel® (Ethicon®, Switzerland). It is a 5 cm × 7.5 cm absorbable hemostat without collagen material reshaped and sutured on the graft. We did not choose the collagen membrane to cover the bone graft in order to eliminate the existence of the collagen. Thus, we could compare between the collagen and the xenograft bovine bone substitute.

The Bio-Oss® contains a mineral and hard natural bovine bone portion with a very similar human bone structure, and it is used as an allergen-free xenograft material. It is deproteinized with different sizes of particles. We used the 1–2 mm spongy bone granules.

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the Bio-Oss® granules hydrated by a physiological solution were inserted in small amounts into the socket. They were then compacted to fill all the socket gap to the level of the buccal bone, thus leaving the adequate space for the Surgicel® mesh to cover it and substitute the soft tissues.

Here, we ensured that the bleeding in the socket was enough to fill the grafting material. In case of multiple root structures, all the gaps of the roots were filled with the xenograft bone (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Insertion and suturing of the xenograft. In a, the Bio-Oss® is well placed into the socket of an upper first molar at the level of the bone, we can see the surrounding tissues well preserved and the bone grafting granules seated without any excessive pressure. In b, the sutures done without any excessive pressure on the soft tissue conserving the initial volume of the socket

After the surgical procedure in both groups, sutures were done by using a 6-0 violet monofilament (Glycolon®, Resorba, Germany) with a reverse cutting 11 mm, 3/8 premium needle. Mattress sutures were made to fix the materials in place, conserving the initial volume of the soft tissues of the socket without any excessive pressure (Fig. 6b).

Post-grafting Care

The patient was instructed to bite on a sterile gauze on the surgical area for 1 h.

To avoid interferences in the measures of pain feelings, he/she had to put an ice pack on the external side of the cheek at the site of the extraction for 3 h.

Precautions were given to the patient; he/she should be away from heat and should not eat hot or hard food and never rinse his mouth for 2 days after the surgery. On the other hand, the patient should not take any medicine before the anesthesia was gone. In case of pain, the patient could take paracetamol as a pain killer, 2 tablets of 500 mg Panadol® every 6 h without exceeding 8 tablets or 4000 mg a day.

If he/she continued to experience any pain, he/she could contact his dentist. The patient is well instructed to write down the level of pain on the pain assessment tool before taking the pain killer.

Mouth rinse should be done for 10 days, starting from the second day following the surgery, by using Paroex® (Gum, Germany) 0.12% at an amount of half of a capful 3 times a day. Moreover, the patient should not touch or cut the sutures and smoking is not allowed for 1 week after the surgery.

We avoid to prescribe antibiotics, as they could interfere with the pain experience documented on the NRS.

Pain Management

The patients recorded their pain perception every day for 1 week, 3 times a day. Each patient was seen at day 3 after the extraction, day 7 and day 14. Before leaving the clinic, the patient was informed how to document on a given journal (Fig. 7) his pain experience using the NRS. Analgesic medications were taken 3 times a day in case of pain, and the pain perception was noted on the scale. The pain experience was measured by collecting the data in the journal given to the patients, where they documented the pain on the NRS; 0 to 10 zero means no pain and 10 means the maximum pain.

Fig. 7.

Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) journal given to the patient

On the pain scale, we have expressive faces with their related numbers with short words in order to facilitate the procedure of choosing the right number compatible with the pain feeling. In the first line, we note Emoji-like faces with different expressions. Below are the numbers linked to the related pain perceptions. At the bottom of the figure, we see the week days with spaces to be filled by the patient with the pain related numbers, 3 times a day.

Under each day of the week in the journal were three spaces to write down the pain perception in the morning, noon and in the evening.

Wound Healing Rate

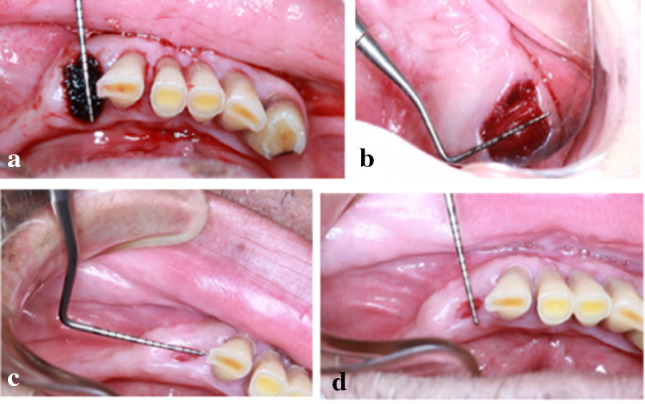

At the day of the extraction, and after pulling out the tooth, the distance between soft tissues margins was measured by a periodontal probe (Kohler® 7545 Germany), mesiodistally and buccolingually, before and after the insertion of the material in the socket. Photographs with the probe in place were taken at day 0, day 3, day 7 and day 14 to collect the data (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Wound healing measurements. We see in a measurements of the wound at surgery day buccolingually by the periodontal probe of the xenograft technique, in b measurements at the surgery day of the collagen technique, in c measurements at day 7 and in d measurements at day 14 were performed

Statistical Analyses

We used the IBM SPSS software for the statistical analysis. The mean values and the standard deviations were calculated using the recorded data. The Mann–Whitney U test and the Friedman Test were both used for the statistical differences in the pain and the wound healing rates.

Results

Thirteen patients were included in this study, 6 females and 7 males, giving a total of 26 post-extraction filled sockets (Table 1). All procedures were carried out according to our experimental protocols and all the patients that participated in the study did not have any complications. Out of patients that had two teeth to be extracted in the same jaw, 13 patients fulfilled all the inclusion criteria and filled their sockets with collagen on a site and Bio-Oss® on the other site.

Table 1.

Patients’ distribution

| Case number | Gender | Age (year) | Collagen site* | Bio-Oss® site* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 45 | 43 | 33 |

| 2 | M | 45 | 16 | 26 |

| 3 | F | 26 | 45 | 35 |

| 4 | F | 26 | 24 | 14 |

| 5 | F | 21 | 38 | 48 |

| 6 | M | 67 | 17 | 26 |

| 7 | M | 55 | 37 | 36 |

| 8 | M | 68 | 15 | 21 |

| 9 | F | 29 | 38 | 47 |

| 10 | F | 28 | 25 | 14 |

| 11 | F | 60 | 36 | 46 |

| 12 | M | 45 | 24 | 16 |

| 13 | M | 52 | 37 | 46 |

| Mean ± SD | – | 43.6 ± 16.1 | – | – |

| Female | 6 (46.2%) | |||

| Male | 7 (53.8%) | |||

| Frequency N | All (N = 13) |

Thirteen cases, 7 males (53.8% of the cases) and 6 females (46.2% of the cases) with a mean of 43.6 as age, with standard deviation of 16.1. For each case, we put the extracted teeth numbers and the related technique of ridge preservation

SD standard deviation; FDI (Federation Dentaire Internationale); N frequency

*FDI provided tooth number

Pain Management

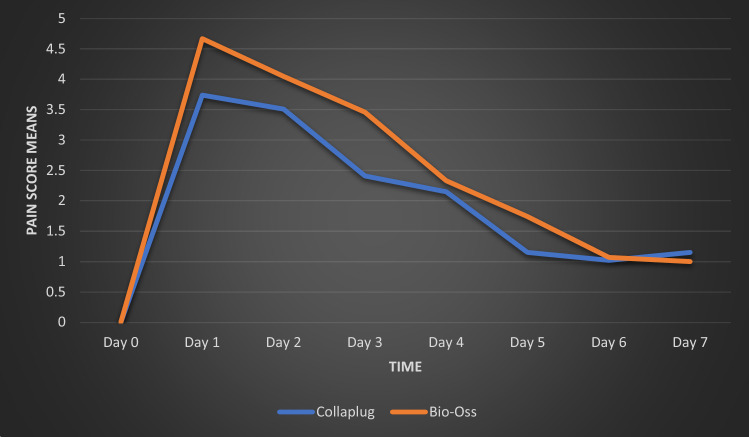

In fact, the pain decreased gradually from the first to the seventh day where no pain was felt anymore, and it was confirmed by the Friedman Test within each group; P = 7.44E−37 < 0.05. The Mann–Whitney U test revealed that there were no significant differences in the means of the pain rating scores between the collagen and the xenograft bone; P = 0.397 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of pain scores in each group at day 0 and at seven consecutive postoperative days

| Pain scores | Total (N = 26) |

Collagen group (n = 13) |

Bio-Oss group (n = 13) |

P value between groups* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | 1.00 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.0) | |

| Day 1 | 0.268 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.20 (2.15) | 3.74 (1.77) | 4.67 (2.47) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (1.00–9.67) | (2.00–7.33) | (1.00–9.67) | |

| Day 2 | 0.589 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.78 (1.79) | 3.51 (1.45) | 4.05 (2.10) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (1.33–8.33) | (1.67–7.33) | (1.33–8.33) | |

| Day 3 | 0.171 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.93 (1.88) | 2.41 (1.09) | 3.46 (2.36) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (1.00–9.67) | (1.33–4.33) | (1.00–9.67) | |

| Day 4 | 0.638 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.24 (1.11) | 2.15 (0.78) | 2.33 (1.40) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (1.00–5.00) | (1.33–4.00) | (1.00–5.00) | |

| Day 5 | 0.004 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.44 (0.61) | 1.15 (0.29) | 1.74 (0.71) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (1.00–3.33) | (1.00–2.00) | (1.00–3.33) | |

| Day 6 | 0.286 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.05 (0.12) | 1.02 (0.09) | 1.07 (0.14) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (1.00–3.33) | (1.00–1.33) | (1.00–1.33) | |

| Day 7 | 0.317 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.08 (0.39) | 1.15 (0.55) | 1 (0) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (1.00–3.00) | (1.00–3.00) | (1.00–1.00) | |

| P value within each group† | 7.44E−37 | 2.38E−17 | 2.85E−15 | |

| Total pain score | 0.397 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 16.74 (6.90) | 15.15 (4.49) | 18.33 (8.59) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (7.66–33.66) | (9.66–23.00) | (7.66–33.66) |

P value < 0.05 is considered significant

SD standard deviation; Min minimum; Max maximum; N frequency

*Mann–Whitney test

†Friedman test

However, we noticed that the Bio-Oss® showed more pain experience during the 7 days after the surgery (Fig. 9), especially in the fifth day with P = 0.004 < 0.05 (Table 2).

Fig. 9.

Means of pain scores between the first and the second techniques during 7 days

We compared the rate of the wound closure by measuring the space between the soft tissue margins in buccolingual and mesiodistal directions of the filled sockets using a periodontal probe (Kohler® 7545 Germany) in place. As we expected, the wound closure began directly after the surgery, and from one visit to another the measures confirmed it, P = 1.91E−16 in the mesiodistal and P = 3.37E−16 in the buccolingual. The means and the standard deviations of the wound closure rates are shown in Tables 3 and 4. The Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to check the significant differences between the two groups. The test results are as follows:

In Table 3, we noticed that there was no significant difference in the mesiodistal healing rate between the collagen and the xenograft bone; P = 0.204. As shown in Fig. 10, the graph reveals that the collagen group was always in a higher rate of closure than the Bio-Oss® group.

In Table 4, the difference between the collagen and the xenograft bone in the buccolingual healing rate was significant; P = 0.045. In Fig. 11, the graph shows clearly the higher wound closure rate of the collagen group that reached at day 14 more than 60% of the wound closure. The Bio-Oss® group did not reach the 60% of the wound closure at day 14.

Table 3.

Comparison of the mesiodistal healing rate scores in each group at day 0, day 3, day 7 and day 14

| Scores of the MD wound healing rate | Total (N = 26) |

Collagen group (n = 13) |

Bio-Oss group (n = 13) |

P value between groups* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | 1.00 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.0) | |

| Day 3 | 0.188 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.15 (0.12) | 0.19 (0.13) | 0.13 (0.1) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (0.08–0.50) | (0.05–0.50) | (0.0–0.38) | |

| Day 7 | 0.088 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.27 (0.16) | 0.31 (0.16) | 0.22 (0.16) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (0.10–0.80) | (0.11–0.63) | (0.0–0.63) | |

| Day 14 | 0.269 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.41 (0.19) | 0.45 (0.19) | 0.36 (0.17) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (0.30–1.00) | (0.22–0.82) | (0.13–0.75) | |

| P value within each group† | 1.91E−16 | 2.23E−8 | 3.03E−8 | |

| Total healing score | 0.204 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.83 (0.46) | 0.95 (0.47) | 0.71 (0.43) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (0.20–1.88) | (0.44–1.88) | (0.20–1.76) |

P value < 0.05 is considered significant

SD standard deviation; Min minimum; Max maximum; N frequency; MD mesiodistal

*Mann–Whitney test

†Friedman test

Table 4.

Comparison of the buccolingual healing rate scores in each group at day 0, day 3, day 7 and day 14

| Scores of the BL wound healing rate | Total (N = 26) |

Collagen group (n = 13) |

Bio-Oss Group (n = 13) |

P value between groups* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | 1.00 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.0) |

| Day 3 | 0.76 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.25 (0.12) | 0.28 (0.11) | 0.21 (0.13) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (0.08–0.50) | (0.15–0.50) | (0.08–0.50) | |

| Day 7 | 0.035 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.4 (0.18) | 0.48 (0.17) | 0.33 (0.17) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (0.10–0.80) | (0.20–0.80) | (0.10–0.67) | |

| Day 14 | 0.158 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.58 (0.2) | 0.64 (0.21) | 0.52 (0.18) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (0.30–1.00) | (0.30–1.00) | (0.30–0.89) | |

| P value within each group | 3.37E−16 | 1.99E−8 | 5.47E−8 | |

| Total BL healing score | 0.045 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.22 (0.46) | 1.39 (0.45) | 1.06 (0.42) | |

| Range (Min–Max) | (0.60–2.20) | (0.65–2.20) | (0.60–1.78) |

P value < 0.05 is considered significant

SD standard deviation; Min minimum; Max maximum; N frequency; BL buccolingual

*Mann–Whitney test

†Friedman test

Fig. 10.

Means comparison of the mesiodistal healing rates between the two used techniques during 14 days. MD Mesiodistal

Fig. 11.

Means comparison of the buccolingual healing rates between the two used techniques during 14 days. BL Buccolingual

Discussion

In the present study, we assessed the wound healing rate and pain perception supported by collagen material or xenograft bovine bone covered with cellulose mesh that were used to fill sockets.

Concerning the pain management, to eliminate a number of variables interfering with the scores and knowing that the pain rating of the patient is subjective, we had chosen to compare the two groups in the same jaw and the mouth of the same patient.

In fact, in the two groups, the Mann–Whitney U test showed no significant difference upon comparing the pain rating scores for 7 consecutive days; P = 0.397 (Table 2). The fact that the P value is > 0.05 means that the difference between the two groups is statistically not significant. Thus, the pain expression was not statistically different between the collagen versus the xenograft bovine bone group. Intriguingly, we noted in Fig. 9 that the means of the pain rating scores of the xenograft bovine bone group were always more than those of the collagen group throughout the 7 consecutive days, with P = 0.04 in the fifth day (Table 2). A better conclusion could be obtained by testing a higher number of cases in ongoing investigations more elaborated than our present pilot study. Concerning the rate of the wound healing, we evaluated each group by both the dental mesiodistal and buccolingual measures. The Mann–Whitney U test results showed P = 0.204 for the mesiodistal measures and P = 0.045 for the buccolingual measures. This indicates that the differential wound closure between the two groups was significant in the buccolingual but not significant in the mesiodistal. This could be explained by the fact that, in the mesiodistal area, the proximal bone and the surrounding soft tissues are considered as thick biotype highly vascularized cancellous bone covered by a thick papilla [22]. This highly vascularized portion of the socket maintained during the healing period by the proximal anatomy of bone and teeth will heal regardless of the type of the biomaterial inserted into the wound. That might explain the insignificant difference between the two groups in the mesiodistal measurements.

On the other hand, in the buccolingual area of the socket, the buccal bone and the surrounding soft tissues are supported by the biomaterial inserted into the socket. In our study, for the same patient with the same biotype in the buccolingual area, the collagen had a direct effect on the wound healing since there was a significant difference between the two groups. Tsai et al. focused on the role of collagen in the stabilization of the blood clot that is a scaffold where angiogenesis began with fibrous tissues formation [23]. Interestingly, it has been shown that the presence of the collagen in the socket had given the opportunity for the healing to be faster [24]. The fast healing might have protected the clot and could be considered as a good potential for bone growth in the socket. In the xenograft group, the socket was filled with slowly degraded xenograft bovine bone particles without any collagen material and that might be responsible for the difference in the healing closure rate.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations of this pilot study, we can conclude that collagen seems to be more efficient than xenograft in terms of both wound closure and pain management. In future studies, our results should be powered by a larger sample size in order to make definite conclusions concerning the comparison between the two materials. Furthermore, the bone quality of the filled socket should also be compared in the two concerned groups.

Funding

None.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The authors do not have any financial interests, either directly or indirectly, in the products or information listed in this paper.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Vincent Saliba, Email: vincentfsaliba@gmail.com.

Nabih Nader, Email: nabihnader@gmail.com.

Antoine Berberi, Email: anberberi@gmail.com.

Wafaa Takash Chamoun, Email: wafaatakash@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Willenbacher M, et al. The effects of alveolar ridge preservation: a meta-analysis. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2016;18(6):1248–1268. doi: 10.1111/cid.12364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Presson SM, Niendorff WJ, Martin RF. Tooth loss and need for extractions in American Indian and Alaska Native dental patients. J Public Health Dent. 2000;60(Suppl 1):267–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2000.tb04073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van der Weijden F, Dell’Acqua F, Slot DE. Alveolar bone dimensional changes of post-extraction sockets in humans: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36(12):1048–1058. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardaropoli G, Araujo M, Lindhe J. Dynamics of bone tissue formation in tooth extraction sites. An experimental study in dogs. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30(9):809–818. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051X.2003.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schropp L, et al. Bone healing and soft tissue contour changes following single-tooth extraction: a clinical and radiographic 12-month prospective study. Int J Periodontics Restorat Dent. 2003;23(4):313–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elian N, et al. A simplified socket classification and repair technique. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2007;19(2):99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ettl T, et al. Bone resorption and complications in alveolar distraction osteogenesis. Clin Oral Investig. 2010;14(5):481–489. doi: 10.1007/s00784-009-0340-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jambhekar S, Kernen F, Bidra AS. Clinical and histologic outcomes of socket grafting after flapless tooth extraction: a systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. J Prosthet Dent. 2015;113(5):371–382. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schnutenhaus S, et al. Alveolar ridge preservation with a collagen material: a randomized controlled trial. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2018;48(4):236–250. doi: 10.5051/jpis.2018.48.4.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niki H, et al. Computed tomographic examination of bone healing after placement of collagen sponge matrix in the tooth extraction site. J Osaka Odontol Soc. 2001;64:369–374. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdelaziz MA, et al. Effect of collaplug® on the healing of extraction sockets in patients under oral anticoagulant therapy (clinical study) Alex Dent J. 2015;40(2):166–172. doi: 10.21608/adjalexu.2015.59145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kao RT, Murakami S, Beirne OR. The use of biologic mediators and tissue engineering in dentistry. Periodontol. 2000;50:127–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2008.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McAllister BS, et al. Eighteen-month radiographic and histologic evaluation of sinus grafting with anorganic bovine bone in the chimpanzee. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1999;14(3):361–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pelegrine AA, et al. Clinical and histomorphometric evaluation of extraction sockets treated with an autologous bone marrow graft. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010;21(5):535–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Proussaefs P, et al. The use of titanium mesh in conjunction with autogenous bone graft and inorganic bovine bone mineral (bio-oss) for localized alveolar ridge augmentation: a human study. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent. 2003;23(2):185–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X, et al. Maxillary sinus floor augmentation and dental implant placement using dentin matrix protein-1 gene-modified bone marrow stromal cells mixed with deproteinized boving bone: a comparative study in beagles. Arch Oral Biol. 2016;64:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindhe J, et al. Ridge preservation with the use of deproteinized bovine bone mineral. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2014;25(7):786–790. doi: 10.1111/clr.12170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(7):798–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lund I, et al. Repeated massage-like stimulation induces long-term effects on nociception: contribution of oxytocinergic mechanisms. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16(2):330–338. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goissis G, et al. Biocompatibility studies of anionic collagen membranes with different degree of glutaraldehyde cross-linking. Biomaterials. 1999;20(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(97)00198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gholami GA, et al. Clinical, histologic and histomorphometric evaluation of socket preservation using a synthetic nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite in comparison with a bovine xenograft: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23(10):1198–1204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed AJ, Nichani AS, Venugopal R. An evaluation of the effect of periodontal biotype on inter-dental papilla proportions, distances between facial and palatal papillae in the maxillary anterior dentition. J Prosthodont. 2018;27(6):517–522. doi: 10.1111/jopr.12640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai SJ, et al. Pure type-1 collagen application to third molar extraction socket reduces postoperative pain score and duration and promotes socket bone healing. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118(1 Pt 3):481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun Y, et al. Test in canine extraction site preservations by using mineralized collagen plug with or without membrane. J Biomater Appl. 2016;30(9):1285–1299. doi: 10.1177/0885328215625429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]