Abstract

Introduction

Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is characterized by the formation of multiple nodules of cartilage with varying sizes due to metaplastic development of the synovial membrane. Aetiology revolves with primary lesion, and pathogenesis is still unknown with multiple factors, which includes low-grade trauma or internal derangement. This condition remains undiagnosed and leads to therapeutic challenges from clinical manifestations which are non-specific and needs various tools to diagnose with combination of radiologic and histopathological examination.

Materials and Method

We report a case series of five cases which were diagnosed as cases of TMD of the temporomandibular joint. Diagnostic arthroscopy including lysis and lavage with Ringers lactate, hyaluronic acid was carried out. Intra-operative findings were suggestive of synovial chondromatosis. Sample taken for histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of synovial chondromatosis of TMJ. Postoperative status of mouth opening and pain was assessed at 15 days, one month, 3 months, 6 months and one year during the review to evaluate the success of arthroscopy of TMJ.

Results

All patients reported success with the modality of arthroscopy lysis and lavage at 12 months of follow-up with improvement at every follow-up visit in terms of range of motion and reduction of pain score on VAS. Hence, arthroscopy with lysis and lavage came out to be a promising alternative for open joint surgery in cases of synovial chondromatosis of the TMJ with same outcomes in relieving patients who complain of reduced maximum inter-incisal opening and pain.

Conclusion

Thus, arthroscopic procedures can be considered an alternative and effective modality for successful management of cases of synovial chondromatosis of temporomandibular joint.

Keywords: Synovial chondromatosis, TMJ, Arthroscopy

Introduction

Synovial chondromatosis (SC) is a rare proliferative disorder of TMJ which is associated with formation of cartilaginous calcified loose bodies causing symptoms and enlargement of joint capsule. [1] It is a chronic monoarticular condition with formation of highly cellular cartilaginous connective tissue with the aetiology hypothesized towards blunt trauma, joint inflammation due to Temporomandibular joint disorders (TMD) and systemic conditions. [1, 2] The symptoms of the condition include pain on the affected joint, mild swelling and decreased range of motion with joint noises. Due to these presenting symptoms, it is often misdiagnosed as internal derangement and patients often receive treatment for internal derangement before its correct diagnosis. [3] The first documented patient of SC of the TMJ was described by Axhausen in 1933. [4] Since then, there have been more than 200 reported and histopathologically confirmed patients of synovial chondromatosis associated with the TMJ. McCain and de la Rua [5] reported the first arthroscopically treated patient of SC. Arthroscopy was used in 25% of patients, mainly for diagnostic confirmation, while open arthrotomy with synovectomy was the most common treatment reported. [3] Most of the literature about SC comes from patient reports because of the rarity of this disease, and in almost all clinical presentation, there are numerous loose bodies mainly in the upper TMJ compartment. [6] Cai et al. [2] reported a patient of a large solitary SC of the TMJ successfully removed via additional incision in the anterior wall of auditory meatus guided by arthroscopic procedure. These authors proposed the technique as a routine method for removal of larger particles in the posterior recess of the upper joint compartment.[2] The aim of this article is to depict the successful histopathological diagnosis as well as management of SC via TMJ arthroscopy. Objective of the article is to validate TMJ diagnostic arthroscopy as a successful tool for the minimally invasive management of TMJ synovial chondromatosis.

Material and Methods

The case series consist of five cases of three males and two females. Patient age was between 30–42 years with mean age of 36.4 years. Case 1 and 2 were male patients reporting with chief complaint of pain around the temporomandibular joint region. On further evaluation and exploration of past medical history, it was found that both the cases had an episode of road traffic accident (RTA), 3 years back and 18 months back respectively and both were managed conservatively. Case 3 and 4 consisted of one male and one female who reported with the complaint of joint pain and clicking but did not seek any treatment for the same till now. These patients did not report of any history of trauma or infection and were diagnosed as cases of TMJ internal derangement. The fifth case which is our representative case is a female who had an alleged history of trauma with a blunt object one year back and reported with restriction in range of motion and pain in the preauricular area bilaterally.

On clinical examination mouth opening ranged from 22 to 30 mm with a mean mouth opening of 26 mm (Table 1).

Table 1.

Post-arthrocentesis mouth opening of five cases

| Sr no | Age (y) | Sex | Preoperative mouth opening (mm) | Mouth opening after arthrocentesis (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | M | 22 | 24 |

| 2 | 34 | M | 25 | 27 |

| 3 | 36 | M | 23 | 26 |

| 4 | 39 | F | 27 | 27 |

| 5 | 42 | F | 26 | 29 |

All patients had a Class I molar and canine occlusion with no evidence of tooth attrition and wear facets. On palpation of the TMJ, there was tenderness present bilaterally over the muscles of mastication in cases 1 and 2. There was elicitable pain bilaterally on joint palpation which was more pronounced on the left side than on the right side of case 3 and 4 with click on opening and a reciprocal click on closure on left side. On examination of Case 5, there was pre-auricular pain bilaterally but severe pain on left side which aggravated on opening beyond 26 mm along with reciprocal click. Thus, a preliminary diagnosis of TMJ dysfunction was made.

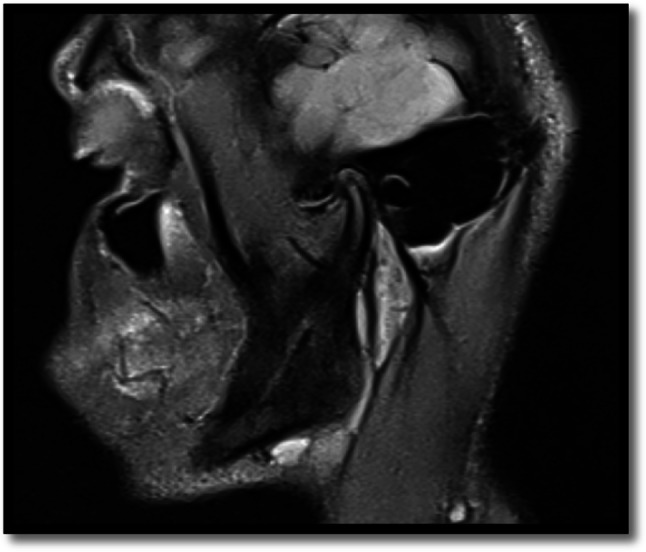

This was followed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of TMJ of case 1 and 2, which showed mild anterior displacement of the disc of the left TMJ with disc returning to its position, while mouth is closed. MRI of case 3 and 4 reported the thickening of lateral pterygoid muscle on left side in closed position. On opening, the disc returned to its normal position and MRI of representative case showed effusion of joint space and increase in amount of synovial fluid with relative thickening of the articular disc and soft tissue swelling on left side. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Preoperative MRI shows relative thickening of articular disc

Management consisted of initial conservative therapy with occlusal soft splints, isometric exercises for muscles of mastication and pharmacological therapy protocol in a step ladder pattern followed by arthrocentesis (Table 1). There was no significant improvement in mouth opening after performing arthrocentesis. Hence, a step ahead therapy of arthroscopy of TMJ was formulated.

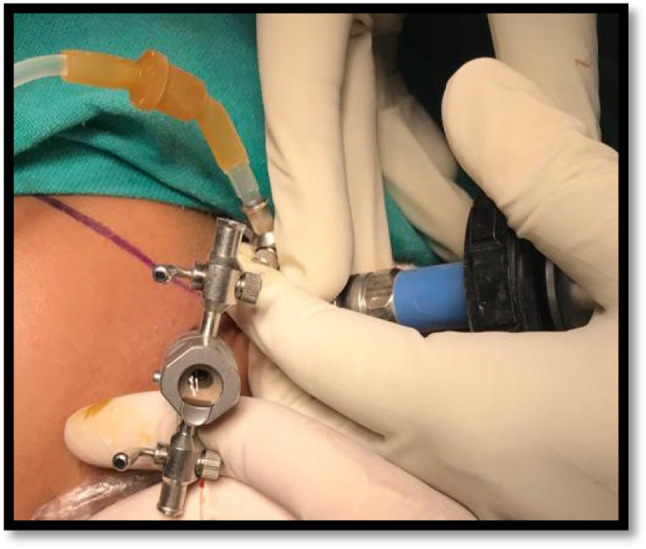

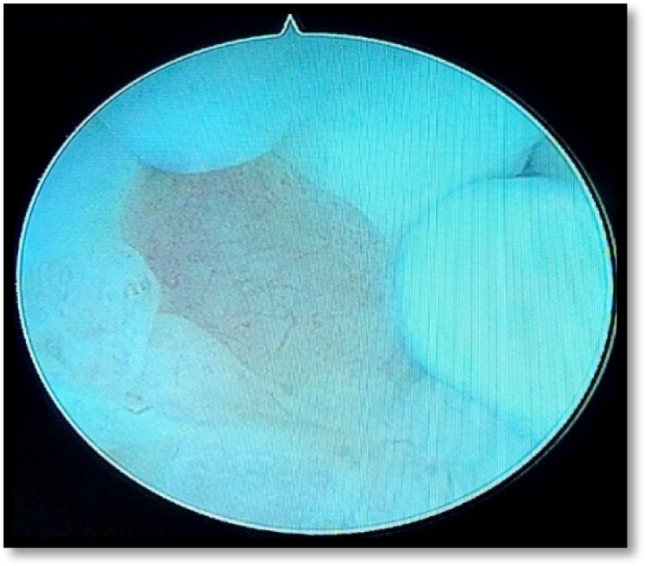

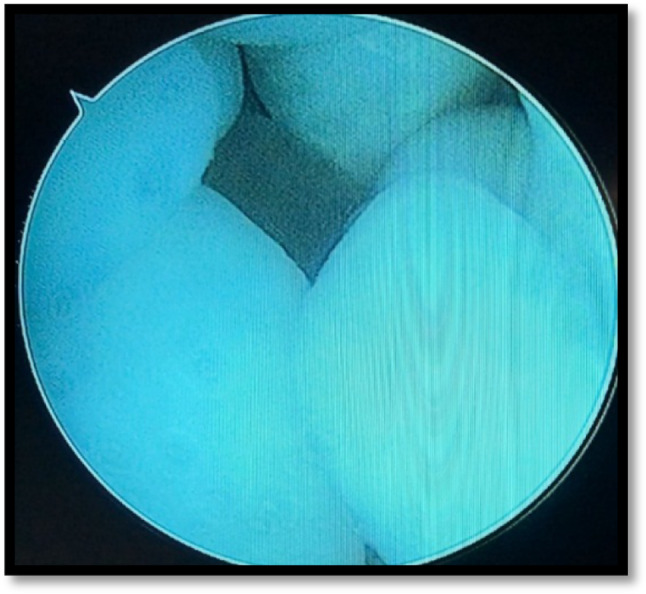

The final diagnosis after clinical and radiological examination was internal joint derangement with disc displacement. All patients underwent proper clinical evaluation and laboratory investigations before undergoing arthroscopy under GA. All patients except 1 were accepted under ASA I. Diagnostic arthroscopy lysis and lavage were done and access was gained using the arthroscopic techniques described by McCain. [7] Arthroscopic examination (Fig. 2) of representative case (case 5) showed a mild degree of hyperemia in the anterior joint space of superior compartment (Fig. 3). Attachments were seen on posterior and posteromedial synovial drapes which were small and four in numbers and attached to each other with a whitish hue (Fig. 4). The fibro-cartilaginous lining of the superior compartment of the joint space showed mild disc fragmentation with attachment of whitish particles. This area was explored and consistency was soft when palpated with an arthroscopic probe, indicating localized, early degenerative changes (Fig. 5). With the condyle seated, there appeared to be approximately 90% roofing of the condyle by the disc (Fig. 6). A second cannula was placed anterior to the first, and the particles were palpated with a blunt probe (Fig. 7). The particles were relatively smooth in texture when explored with the probe. An ovoid portion of the anterior synovium was sectioned, removed with biopsy forceps and submitted for histopathologic examination. The area was irrigated with copious amounts of Ringer's lactate solution before removal of the instruments, and 1500 IU hyaluronic acid was introduced during removal. Patients were followed up sequentially at 15 days, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months for improvement of mouth opening, (Table 2) review of symptoms and any deterioration or improvement of prearthroscopic procedure stage.

Fig. 2.

Arthroscopic examination of representative case

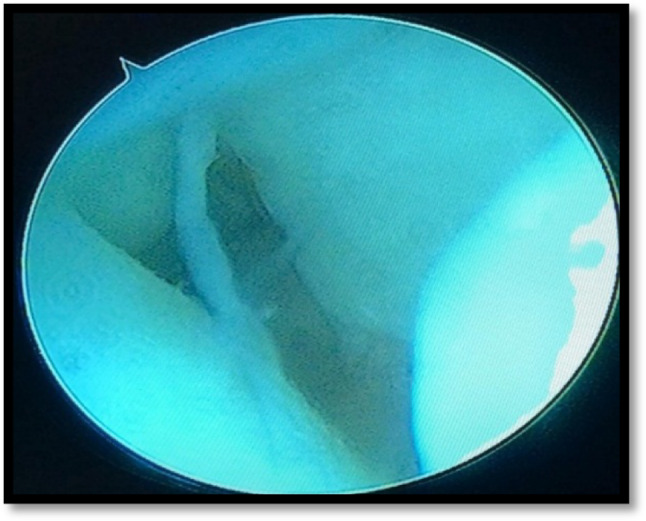

Fig. 3.

An arthroscopic image showing mild degree of hyperemia in the anterior joint space

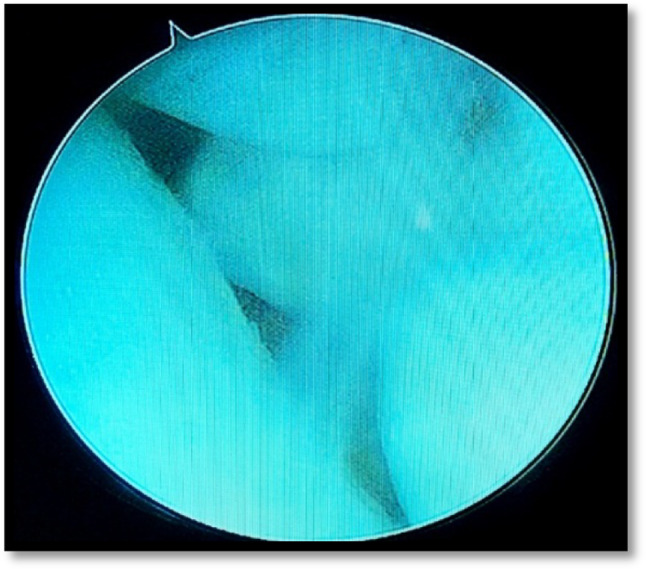

Fig. 4.

Arthrosopic image showing the presence of calcified bodies four in number with whitish hue

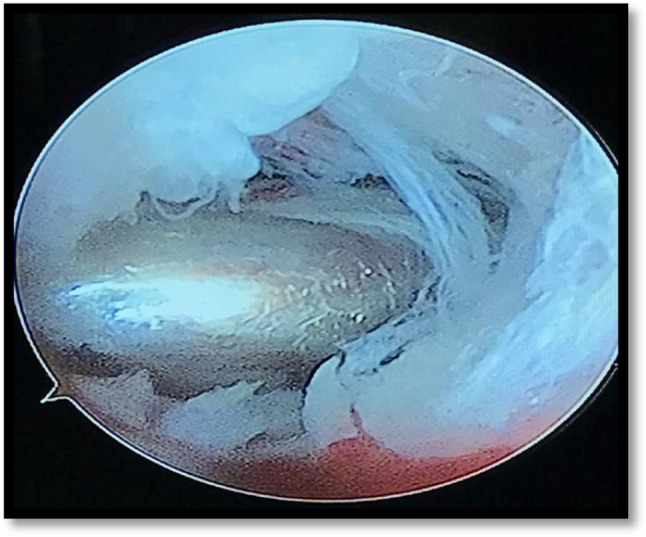

Fig. 5.

Arthrosopic image showing the presence disc fragmentation with attached whitish particles

Fig. 6.

Arthrosopic image showing roofing of condyle by the disc

Fig. 7.

Arthrosopic image showing placement of second cannula

Table 2.

Post-arthroscopy mouth opening at follow-up

| Sr no | Age/sex | Pre-arthroscopy mouth opening | Post-arthroscopy mouth opening | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 days | 1 month | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | |||||

| 1 | 30y M | 24 mm | 29 mm | 31 mm | 32 mm | 32 mm | 33 mm | ||

| 2 | 34y M | 27 mm | 32 mm | 33 mm | 34 mm | 35 mm | 36 mm | ||

| 3 | 36y M | 26 mm | 32 mm | 32 mm | 33 mm | 33 mm | 35 mm | ||

| 4 | 39y F | 27 mm | 34 mm | 36 mm | 36 mm | 37 mm | 37 mm | ||

| 5 | 42y F | 29 mm | 35 mm | 37 mm | 37 mm | 39 mm | 40 mm | ||

Results

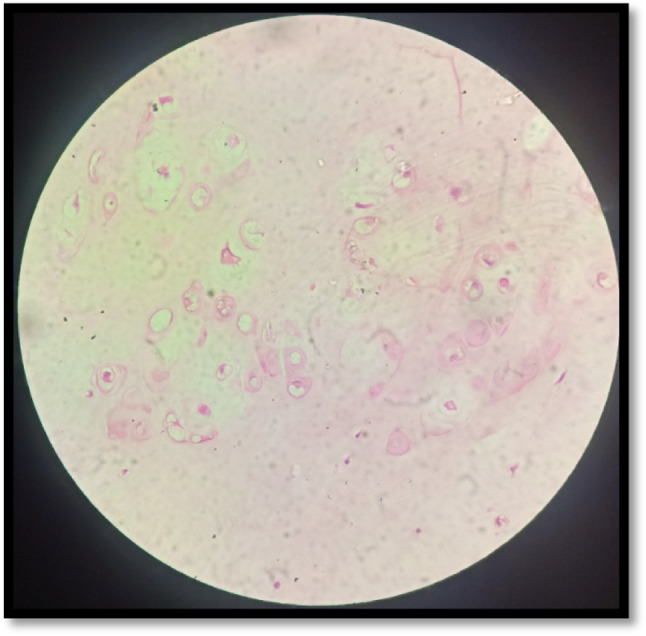

Five patients two female and three male diagnosed clinico-radiologically as cases of internal derangement of TMJ unilateral were taken up under GA for diagnostic arthroscopy lysis and lavage. Along with arthroscopy lysis and lavage anterior synovium sample from the joint were taken arthroscopically and sent for histopathological examination (HPE) (Fig. 8). The HPE of all the specimens confirmed the diagnosis of synovial chondromatosis (Fig. 9). Postoperatively on clinical evaluation of mouth opening was followed up at interval of 15 days, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months as depicted in (Table 2). Mouth opening in all cases ranged from 24 to 29 mm (mean 26.5 mm) preoperatively, which improved to range of 33 mm to 40 mm (mean 36.5) postoperatively after 12 months of follow-up. Thus, a satisfactory improvement in mouth opening of 10 mm has been achieved along with histopathological confirmation of synovial chondromatosis. There was no recurrence of sign and symptom of internal derangement like clicking, crepitus or restriction in mouth opening 12 months postoperatively, and thus, the results observed in our series of patients treated by arthroscopy were satisfactory. Pain followed by restricted mouth opening was the main symptom in our patients, which improved significantly after arthroscopic treatment and was also improving throughout the follow-up. Mouth opening improved dynamically in first postoperative month in all patients and patients reported good and consistent improvement with no deviation and stable occlusion. On examination the TMJs was not tender, and patients were comfortable with no evidence of any postoperative complication and discomfort.

Fig. 8.

Arthrosopic image showing biopsy scissor in situ

Fig. 9.

Histopathological image confirmed synovial chondromatosis of the biopsy sample

Discussion

Synovial chondromatosis of the TMJ is an extremely rare condition. All reported cases have been monoarticular, with women affected more frequently than men.

Temporomandibular joint SC affects an older age group when compared with this disease in the axial skeleton. A mean age of 47 years at diagnosis and a range of 18 to 75 years of age have been reported for temporomandibular involvement. [16]

The most widely accepted predictions on the origin of TMJ synovial chondromatosis are metaplastic cartilaginous change of subintimal layer of the synovial membrane which is a mesenchymal remnant during embryonic life. [8–10] Some metaplastic foci form a spheroidal body with villous processes of synovium serving as a scaffold which is nourished by blood supply of the synovial tissue and nutrients of synovial fluid. These foci form a perichondrium and allow chondrocytes to grow by proliferation. [11–13] Calcification of these cartilagenous foci occurs in advanced stages of the disorder, and as growth continues, they detach from the synovial wall and become free-floating bodies within the joint space. [3, 9, 12]

Further diagnostic confusion occurs when synovial chondromatosis is found in the presence of other joint diseases. A review of the literature by Forsell et al. [16] has demonstrated that the frequency of signs and symptoms in the TMJ is similar to that found in the axial skeleton. Pain was present 78% of the time and varied from mild discomfort to severe pain. Other common manifestations included swelling (73%), decreased range of motion (41%) and mandibular deviation on opening (35%). Joint noise included crepitus (41%) and clicking or popping (24%). Other signs and symptoms included joint laxity, mandibular displacement to the contralateral side, inability to achieve centric occlusion, vertigo and tinnitus. [8] Radiographic findings can range from no indication of disease to the presence of multiple calcified bodies in the joint space. Other radiographic findings include increased or decreased joint space and irregular or sclerotic bony surfaces. However, the presence of loose bodies in the joint is neither a universal finding, nor is it diagnostic.

Synovial chondromatosis can present with symptoms at any stage of nodule formation or calcification. Milgram classified synovial chondromatosis into three developmental stages. [13]

Stage 1 shows synovial metaplasia without detached bodies.

Stage 2 shows synovial metaplasia and the presence of loose bodies.

Stage 3 shows loose bodies in the joint space with no synovial disease. Calcifications of the loose bodies are present at diagnosis 50% of the time. Other diseases such as degenerative joint disease, inflammatory arthropathies, osteochondritis dissecans and osteochondral fractures can be associated with joint bodies.

Aetiology of synovial chondromatosis includes infection, embryologic disturbance and trauma as potential causes [17]. The presence of coexisting disease may represent a cause of synovial chondromatosis, or it may represent further manifestations of disease [17, 18]. No single imaging modality has been shown to yield consistent findings in cases of synovial chondromatosis. The most common findings include calcified joint bodies, widening of the joint space and degenerative findings in the condyle and fossa [19].

According to Sim [14], it is believed that treatment should consist of removal of the affected synovial tissue and of any free particles. Arthroscopy of the joint with lysis and lavage is also a recommended therapy. [15] The cases of synovial chondromatosis of the TMJ reported in our case series, were detected and treated using arthroscopic techniques. Radiographically the cases did not show bony changes in condylar morphology nor any intra-articular calcific changes or loose bodies. The suggestive findings of TMJ synovial chondromatosis were detected only while performing the arthroscopy of the joint. The diagnosis and operative outcomes are enhanced by the degree of magnification, and the image quality provided by the arthroscope. The therapeutic advantages provided by arthroscope are vast and are not only limited to the area involved.

Conclusion

Synovial chondromatosis is one of the rare diseases affecting TMJ and surgery for removal of calcific masses is the only option as mentioned in the literature. However, in early stages of disease, if the condition can be diagnosed management by diagnostic arthroscopy has proven to be an option to outpass open joint surgery of TMJ. Hence, TMJ arthroscopy serves as a valuable option in management of synovial chondromstosis with improvement in function of TMJ.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted after clearance from institutional ethical committee.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was taken in all patients, and the procedure was explained to them in the language they understand.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

P. Satyanarayan, Email: dr.satyanarayan.pandey@gmail.com

I. D. Roy, Email: indranilcdu@yahoo.co.in

Yuvraj Issar, Email: yuvraj.issar189@gmail.com.

Kapil Tomar, Email: kapiltomar@yahoo.co.in.

Sabareesh Jakka, Email: jsabareesh@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Sink J, Bell B, Mesa H. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint clinical, cytologic, histologic, radiologic, therapeutic aspects, and differential diagnosis of an uncommon lesion. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;117:e269. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai XY, Yang C, Chen MJ, et al. Arthroscopically guided removal oflarge solitary synovial chondromatosis from the temporomandibularjoint. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:1236. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ardekian L, FaquinW TMJ, et al. Synovial chondromatosis of thetemporomandibular joint: report and analysis of eleven cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:941. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axhausen G. Pathology and therapy of the temporomandibular joint [in German] Fortschr Zahnheilk. 1933;9:171–186. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCain JP, de la Rua H. Arthroscopic observation and treatment ofsynovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;18:233. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(89)80060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blankenstijn J, Panders AK, Vermey A. Synovial chondromatosisof the temporomandibular joint. Report of 3 cases and a review of theliterature. Cancer. 1985;55:479–485. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850115)55:2<479::AID-CNCR2820550232>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MCCAIN JP Arthroscopy of the human temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;48:648–655. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(88)90107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrish RB, Hansen LS, Ware WH. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibularjoint. J Craniomand Prac. 1983;2:65–70. doi: 10.1080/07345410.1983.11677854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spjut HJ, Dorfman HD, Fechner RE, Ackerman LV (1977) Tumors of bone and cartilage. In Atlas of tumor pathology, 2ndSeries, Fascicle 5. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington; pp 391–396

- 10.Thompson K, Schwarz HC, Miles JW. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibularjoint presenting as a parotidmass: possibility of confusion with a benignmixed tumor. Oral Surg. 1986;62:377–380. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy GP, Dahlin DC, Sullivan CR. Articular synovial chondromatosis JBone Joint Surg. 1962;44:7286. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ronald JB, Keller EE, Weiland LH. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibularjoint. Cancer. 1972;30:791–795. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197209)30:3<791::AID-CNCR2820300329>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulax WC, Rhvne RR. Synovial chondromatosis of temporomandibularjoint: report of a case. Oral Surg. 1969;28:906–913. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(69)90347-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sim FH. Synovial proliferative disorders: role of synovectomy. Arthroscopy. 1985;1:198–203. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(85)80012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.KusenGJ, Chondromatosis: report of a case. J Oral Surg. 1969;27:735–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forssell K, Happonen R-P, Forssell H. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint Report of a case and review ofthe literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;17:237–241. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(88)80048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deboise A, Roche Y. Synovial chondromatosis of the TMJpossibly secondary to trauma. A case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;20:90–92. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80714-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quinn PD, Stanton DC, Foote JW. Synovial chondromatosiswith cranial extension. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:398–402. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90313-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herzog S, Mafee M. Synovial chondromatosis of the TMJ: MRI and CT findings. Am J Neuroradiol. 1990;11:742–745. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]