Abstract

TBX1 is systematically conserved in the T-box transcription factor family and regulates craniofacial muscle development during various stages of myogenesis, including commitment, proliferation, terminal differentiation, and survival. However, the role and mechanism by which TBX1 regulates the myogenic development of myoblasts remains unclear. In our study, we overexpressed TBX1 in mouse C2C12 myoblasts using a lentivirus method. We found that TBX1 inhibited cell proliferation and muscle differentiation, which had no effect on apoptosis. During myogenic differentiation, we also found that TBX1 overexpressing cells regulate myogenic differentiation by upregulating the expression levels of Smad2 and Smad3 and downregulating the expression level of MEF2C. After treatment with a specific inhibitor of Smad3 (SIS3), the myogenic differentiation of wild-type and TBX1 overexpressing cells increased. Thus, TBX1 may regulate myoblast muscle differentiation by enhancing the expression of Smad2 and Smad3. TBX1 may be a therapeutic target for muscular dystrophy.

Keywords: TBX1, proliferation, myogenic differentiation, apoptosis, Smad2/3, SIS3

Impact Statement

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a common fatal genetic disease, and there is no effective treatment for this disease. Our study has explored the role of TBX1 in the myogenic differentiation, which is expected to provide new potential targets for the treatment of DMD.

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a severe, progressive neuromuscular disease with an incidence of approximately 1/(3600–6000).1,2 The disease is a fatal genetic condition characterized by progressive muscle atrophy, loss of motor function, and impaired cardiovascular and respiratory functions. Most patients are male, mainly related to the spontaneous mutation of the dystrophin gene located on chromosome Xp21.2. 2 Dystrophin gene deletion mutations lead to the disruption of muscle membrane integrity, thus causing muscle weakness, damage, or necrosis as well as inflammation during contractions. Repeated necrosis and regeneration of muscle cells lead to the accumulation of fibrous and fatty connective tissues and depletion of muscle satellite cells. As a result, patients as young as 12 years can only rely on wheelchairs and may eventually die of either heart or respiratory failure around the age of 20–30. 3

TBX1 is systematically conserved in the T-box transcription factor family and has essential functions in the development of the pharynx, craniofacial region, and cardiac outflow tract. TBX1 monoploid deficiency is the main cause of Del22q11.2 syndrome, mainly manifested in craniofacial defects, thymus dysplasia, cardiovascular abnormalities, and throat insufficiency. 4 TBX1 is neither a strong transcription activation factor nor a strong transcription containment factor; it mainly regulates the target gene transcription reaction through epigenetic modifications, which can be activated or inhibited depending on the developmental stage or cell type of the reaction. 5 At present, research on TBX1 mainly focuses on the heart, parathyroid gland, craniofacial, kidney, and basal cell carcinoma. In heart research, the TBX1 gene deletion mutation causes DiGeorge syndrome; heart progenitor cell differentiation is inhibited, leading to large vascular malformations and abnormal development of the cardiac outflow tract.4,6 In a study of the craniofacial mesoderm, TBX1 was expressed upstream of Myf5, and a T-box binding site was present in the Myf5 promoter.7,8 Overexpression of TBX1 increases the number of muscle cells.9,10 TBX1 regulates myogenesis during various stages of myogenic pathway. 11 In different cancers and tumors, TBX1 is both a tumor inhibitor and tumor-promoting factor that regulates the occurrence and development of cancers.12 –14 Although previous studies have shown that TBX1 is an essential factor for regulating myogenic differentiation, the mechanism of TBX1 in limb development is unknown.11,15

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β is an effective suppressor of myogenic differentiation that acts by repressing the transcriptional activity of myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs). 16 Extracellular TGF-β interacts with membrane receptor complexes and participates in intracellular signal cascades to promote the expression of Smad2 and Smad3. It also binds to the Smad4 complex, thereby activating the downstream TGF-β target gene.17,18 Myocyte enhancement factor (MEF2) is the second type of transcription factor necessary for muscle development. MEF2 protein lacks myogenic activity and primarily enhances the transcriptional activity of MRFs through synergistic action, and the two are mutually regulated in a feedback loop. 19

In this study, we used lentiviral transfection to construct a stable transfected cell line overexpressing TBX1 (TBX1 cells). We induced the cells to differentiate into myotubes and explored the mechanism of myogenic differentiation, which is expected to provide a new potential therapy for DMD.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture condition

The C2C12 cell line was purchased from Cybertron Bio Limited (Shanghai, China) and grown in growth medium (GM) or differentiation medium (DM) according to previously reported methods. 20

TBX1 overexpressing cell line construction, transfection, and identification

The human TBX1 gene was constructed using lentivirus (GeneCopoeia, Guangzhou, China). A stable C2C12 cell line overexpressing TBX1 was generated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. TBX1 cells were seeded in GM on six-well plates for 24 h, cellular proteins and RNA were extracted and the expression levels of TBX1 were detected. The primers are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

5-Ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine assays

After treatment for 24 h in GM, wild-type and TBX1 overexpressing cells were harvested to detect cell proliferation ability with the Cell-Light EdU Apollo567 In Vitro Kit (C10310-1, RiboBio, Guangzhou, China). The cells were viewed under a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany).

Flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle and apoptosis

After treatment for 24 h in GM, wild-type and TBX1 overexpressing cells were harvested to detect the cell cycle using a cell cycle detection kit (C1052, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). In addition, after 3 days of differentiation, wild-type and TBX1 overexpressing cells were harvested to detect apoptosis using the Annexin V-APC/7AAD apoptosis detection kit (Catalog No. AP105-100-KIT, Multisciences Biotech, Hangzhou, China). The cells were analyzed using flow cytometry (NovoCyte, ACEA) and Modfit LT software.

SIS3 treatment

The Smad3 inhibitor SIS3 (HY-13013, MCE, USA) is dissolved in DMSO (5 mM) for storage and diluted with the culture medium prior to use. Wild-type cells and TBX1 overexpressing cells were treated with SIS3 (0.5, 1, 3, and 10 μM) for 24 h, and the cell activity was detected by CCK-8 assay (BIOSCIENCE, Shanghai, China). The cells treatment with 0.5 μM SIS3 showed the highest activity. The differentiation of wild-type cells and overexpressed TBX1 cells was obtained by seeding the cells in DM on 6-well plates. A total of 0.5 μM SIS3 was added to the DM, and it was cultured for 7 days.

Western blot

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously. 21 Band intensities were quantified by ImageJ software. The antibodies used are listed in Supplemental Tables S2 and S3.

Immunofluorescence and confocal imaging

Wild-type and TBX1 overexpressing cells were cultured in DM in 24-well plates for 7 days. Immunostaining was performed using MyHC and MyoG primary antibodies and anti-mouse IgG (H + L) and F(ab’)2 fragment (Alexa Fluor® 555 Conjugate) as secondary antibodies, and cell nuclei were treated with DAPI staining solution (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany). The primary and secondary antibodies used are listed in Supplemental Tables S2 and S3.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

All the primers were purchased from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). Primers used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S4.

Data analysis and statistics

Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) and were obtained from at least three independent experiments. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used to compare the results between two groups. P values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

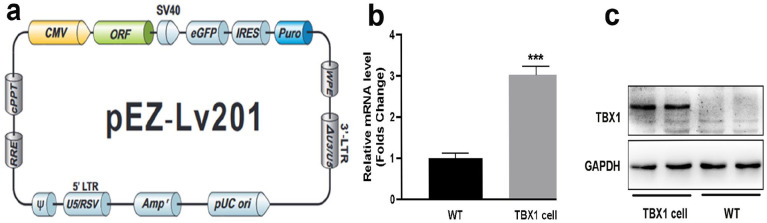

Construction of stable transgenic C2C12 cell line overexpressing TBX1 gene

To explore the role of TBX1 in C2C12 myogenic differentiation, a stable TBX1 overexpressing C2C12 cell line (TBX1 cells) was generated through lentiviral transfection (Figure 1(a)). In this study, the RNA levels of TBX1 were upregulated three-fold in TBX1 cells compared with that in wild-type C2C12 cells (Figure 1(b)). Western blotting showed that the protein levels of TBX1 were successfully expressed in TBX1 cells (Figure 1(c)). Thus, a TBX1 overexpressing C2C12 cell line was successfully constructed and used to study the role of TBX1 in C2C12 myogenic differentiation.

Figure 1.

Identification of TBX1 overexpression cell line: (a) lentivirus used to construct stable TBX1 overexpressing cell line, (b) RNA levels of TBX1 cells increased three-fold in TBX1 compared to that in wild-type cells, and (c) western blot was used to identify the protein level of TBX1 in wild-type and TBX1 overexpressing cells. WT: wild-type C2C12 cells; TBX1cells: TBX1 overexpressing C2C12 cell line. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

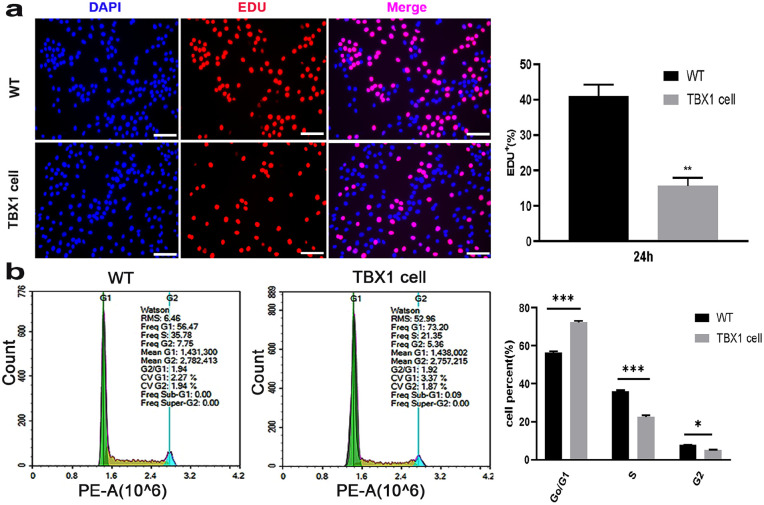

TBX1 overexpression increased C2C12 proliferation

To explore the role of TBX1 in the proliferation of C2C12 cells, we detected the cell cycle of wild-type and TBX1 overexpressing cells, and the results showed that TBX1 overexpression decreased the percentage of 5-ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine (EDU)-positive cells (p < 0.01; Figure 2(a)). Cell cycle analysis indicated that the average proportions of G1, S, and G2 in wild-type cells were 56.47%, 35.78%, and 7.75%, respectively. However, in TBX1 overexpressing cells, the average proportions of cells in G1, S, and G2 were 73.20%, 21.35%, and 5.36%, respectively (Figure 2(b)). The results showed that TBX1 increased the percentage of cells in the G1 phase by 28.47% (p < 0.001) and decreased that in the S phase by 37.48% (p < 0.001). These results indicate that overexpressing TBX1 downregulates the proliferation of C2C12 cells.

Figure 2.

TBX1 overexpression downregulated C2C12 cell proliferation: (a) representative images of the EDU-positive cells (red) were captured in wild-type and TBX1 cells. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue; scale bar = 100 µm) and (b) cell cycle was analyzed by flow cytometry. The green, yellow, and blue peaks represent the G1, S, and G2/M phases, respectively. Mean ± s.e.m., Student’s t-test, two-tailed, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

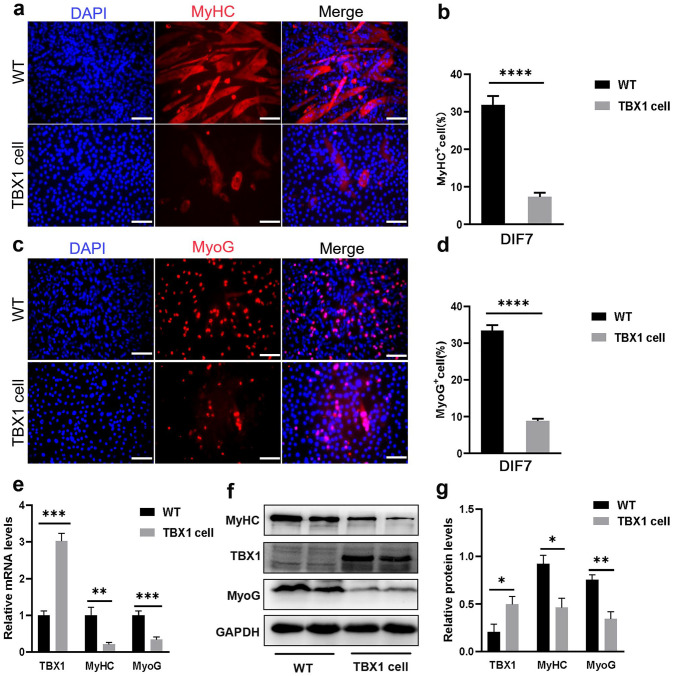

TBX1 overexpression inhibited C2C12 myogenic differentiation

To assess whether TBX1 affected C2C12 myotubes formation, wild-type and TBX1 overexpressing cells were induced to differentiate in DM for 7 days. Immunofluorescence staining analysis showed that the number of MyHC- and MyoG-positive cells was reduced in TBX1 cells (p < 0.0001) compared with that in wild-type C2C12 cells (Figure 3(a) to (d)). The mRNA levels of MyHC (p < 0.01) and MyoG (p < 0.001) were significantly decreased (Figure 3(e)), and the protein levels of MyHC (p < 0.05) and MyoG (p < 0.01) were downregulated in TBX1 cells (Figure 3(f) and (g)). These results indicate that TBX1 overexpression negatively regulates the myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells.

Figure 3.

TBX1 overexpression inhibited C2C12 myogenic differentiation. (a, c) Representative images of MyHC (red) and MyoG (red) immunofluorescence staining of wild-type and TBX1 overexpressing cells on day 7 showing differentiation. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue; scale bar = 100 μm). (b, d) TBX1 decreased the percentage of MyHC- and MyoG-positive cells. (e) qPCR results showed that TBX1 reduced the mRNA levels of MyHC and MyoG on day 7. (f, g) Western blot analysis showed that TBX1 decreased the expression of MyHC and MyoG. Mean ± s.e.m., Student’s t-test, two-tailed, (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001). DIF7: differentiation for 7 days. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

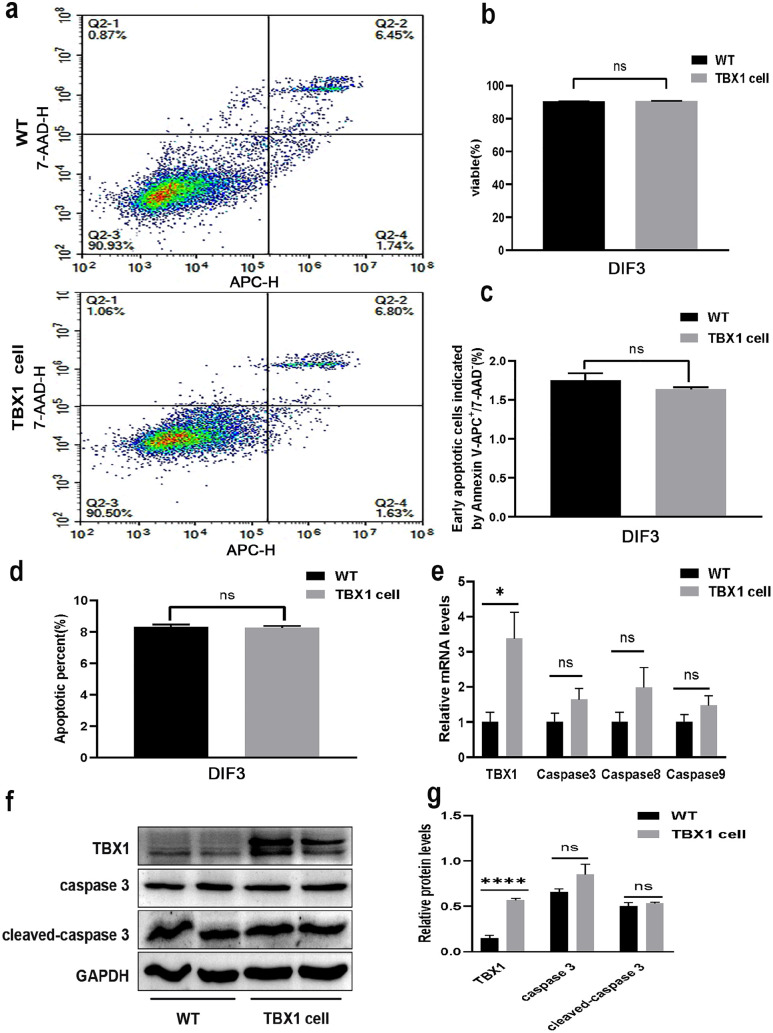

Overexpression of TBX1 has no effect on C2C12 cell apoptosis

To explore the role of TBX1 in C2C12 apoptosis, flow cytometry analysis was performed to determine whether TBX1 overexpression in the differentiation stage induced cell apoptosis (Figure 4(a)). On the third day of differentiation, there was no significant difference in the number of viable cells (p > 0.05, Figure 4(b)), the number of early apoptotic cells (p > 0.05, Figure 4(c)), and the total number of apoptotic cells (p > 0.05, Figure 4(d)). Similarly, overexpression of TBX1 had no effect on the mRNA levels of caspase 3, caspase 8, and caspase 9 (p > 0.05, Figure 4(e)). TBX1 had no effect on the protein levels of caspase 3 and cleaved-caspase 3 (p > 0.05, Figure 4(f) and (g)) on day 3. These results show that TBX1 has no effect on apoptosis during C2C12 myogenic differentiation.

Figure 4.

TBX1 overexpression has no effect on cell apoptosis during C2C12 myogenic differentiation. (a, b, c) Proportion of apoptotic cells was analyzed using Annexin V-APC/7AAD Apoptosis Detection Kit by flow cytometry and quantitative analysis showed that TBX1 had no effect on the number of viable and apoptotic cells on day 3. (d) There were no differences in total apoptotic cells between wild-type and TBX1 cells on day 3. (e) qPCR results indicated that TBX1 does not affect the mRNA levels of caspase 3, caspase 8, and caspase 9 on day 3. (f, g) Western blot analysis showed that TBX1 had no effect on the protein levels of caspase 3 and cleaved-caspase 3 on day 3. Mean ± s.e.m., Student’s t-test, two-tailed, (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001). DIF3: differentiation for 3 days. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

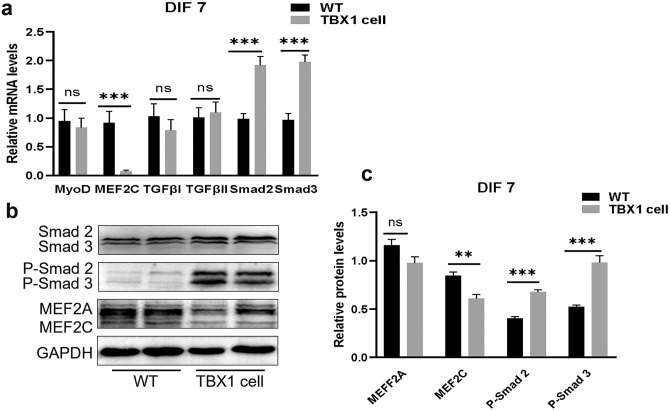

TBX1 regulates muscle differentiation through Smad2 and Smad3

Overexpression of TBX1 upregulated the expression levels of Smad2 and Smad3, also increased their phosphorylation levels. Meanwhile, overexpression of TBX1 downregulated the expression levels of myogenic regulators MEF2C (Figure 5(a) to (c)) as well as reduced the number of myotubes. Thus, we conclude that TBX1 overexpression may downregulate the myogenic differentiation of C2C12 by enhancing the expression levels of Smad2 and Smad3 as well as inhibiting the expression of MEF2C.

Figure 5.

TBX1 regulates TGF-β signaling pathway-related factors: (a) qPCR results confirmed that TBX1 increased the mRNA levels of Smad2 and Smad3 and decreased those of MEF2C on day 7. (b, c) Western blot analysis showed that TBX1 increased the expression levels of Smad2/Smad3 and P-Smad2/Smad3, decreased those of MEF2C. Mean ± s.e.m., Student’s t-test, two-tailed, (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). DIF7: differentiation for 7 days. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

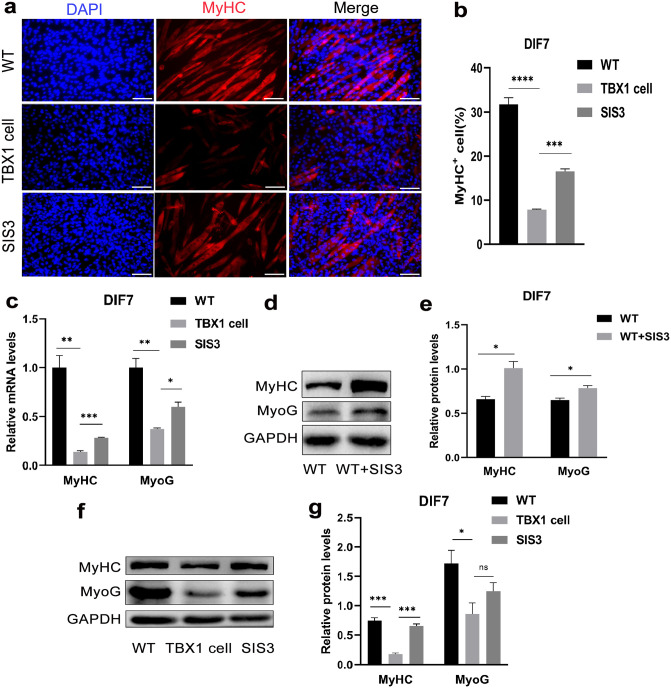

Smad3 inhibition improves the myogenic differentiation of wild-type cells and TBX1 overexpressing cells

To further investigate how TBX1 regulates muscle differentiation through Smad2 and Smad3, 0.5 μM SIS3 was added to the DM and cultured for 7 days. Treatment with Smad3 inhibitor (SIS3), a downstream effector of TGF-β, increased the myogenic differentiation of TBX1 overexpressing cells. The immunofluorescent results showed that SIS3 treatment increased (p < 0.001) the number of MyHC-positive cells (Figure 6(a) and (b)) and increased the mRNA levels of MyHC (p < 0.001) and MyoG (p < 0.05; Figure 6(c)). Western blot results showed that SIS3 treatment also upregulated the protein levels of MyHC and MyoG in TBX1 overexpressing and wild-type C2C12 cells (Figure 6(d) to (g)), suggesting that Smad3-related signaling pathways have a strong negative role in myogenic differentiation. These results strongly support the hypothesis that TBX1 downregulates the myogenic differentiation by activating the Smad3-related signaling pathway in TBX1 overexpressing cells.

Figure 6.

SIS3 treatment increased the myogenic differentiation of TBX1 overexpressing cells: (a) immunofluorescent staining; fluorescence microscopy images were captured with MyHC-positive cells (red) and DAPI (blue) in wild-type and TBX1 cells treated with or without SIS3 (0.5 uM) on day 7. (scale bar = 100 μm). (b) Treatment with SIS3, the percentage of MyHC-positive cells significantly increased in TBX1 cells. (c) Real-time PCR confirmed TBX1 cells treated with SIS3 increased the expression of MyHC and MyoG on day 7. (d, e, f, g) Western blot also showed that protein levels of MyHC and MyoG were increased in TBX1 overexpressing and wild-type C2C12 cells with SIS3 treatment. Mean ± s.e.m., Student’s t-test, two-tailed, (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001). DIF7: differentiation for 7 days. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

Discussion

The proliferation of myoblasts determines the regeneration of skeletal muscles and maintenance of muscle development. C2C12 cells differentiate according to a somitic myogenic program and are commonly used to study the skeletal muscle as an in vitro cellular model. 22 During embryonic development in mice, TBX1 promotes cell proliferation and inhibits cell differentiation. Some studies have found that disrupting the TBX1 gene reduces the vitality and proliferation of cancer cells and induces stage G0/G1 cell stagnation.12,23 In addition, TBX1 is relative to the development of tumors, cancer progression, and potential tumor inhibitors. Usually, after TBX1 is downregulated by initiator methylation, thyroid cancer growth is reduced by disrupting the PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK signaling pathways. 24 In another study, overexpression of TBX1 resulted in decreased proliferation of oral epithelial cells and promoted cell cycle arrest. 25 Therefore, the effect of TBX1 on proliferation may differ between tissue or cell types. In our study, we used EdU detection and flow cytometry analysis to analyze cell cycles. We found that overexpression of TBX1 reduced the proportion of proliferative cells and inhibited C2C12 cell proliferation by blocking cells in phase G1. Therefore, overexpression of TBX1 may inhibit the proliferation of myoblasts.

Skeletal muscle formation is a dynamic process; myogenic differentiation is mainly governed by MRFs, including MyoD, Myf5, MyoG, and MRF4. 26 The muscle-derived regulatory factor is a basic/helix-loop-Helix (bHLH) transcription factor which can form a complex with the E proteins, which are other types of the bHLH transcription factor. It activates MRFs by interacting with the E-box (CANNTG) in the regulatory region. 27 Defects in TBX1 do not fully activate MRFs and its associated factor expression, which negatively regulates myogenic differentiation and defects in organ tissues. 4 Lui et al. 8 showed that TBX1 was expressed upstream of Myf5, and a T-box binding site was present in the Xenopus Myf5 promoter. Kelly et al. 7 showed that Tbx1 expressed in the pharyngeal mesoderm forms branchiomeric skeletal muscles of the head and neck. Myf5 and MyoD cannot be normally promoted in the pharyngeal mesoderm without Tbx1. Moncaut et al. 28 showed that MSC and TCF21 directly regulated Myf5 and MyoD in branchiomeric myogenesis, and TBX1 regulated the expression of Msc and Tcf21 in a direct or indirect manner. In this study, we found that TBX1 overexpression inhibited muscle production regulatory factor expression levels and the number of myotube formations, while the proportion of MyHC- and MyoG-positive cells decreased. These results show that TBX1 inhibits myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells.

Studies have shown that TBX1 may be involved in the regulation of aging and apoptosis in certain cells or tissues and that their expression levels and functions vary from cell to tissue in different types. In a study by Jiang et al., 29 disrupting TBX1 gene expression detected more apoptosis in rat kidney cells. Furthermore, Liu et al. 30 showed that TBX1 overexpression not only suppressed the growth of cervical cancer cells but also disrupted their migration and invasive capability. Kong et al. 31 showed that the muscles responsible for mastication did not form because of cell apoptosis in the core mesoderm of Tbx1−/− null mutant embryos. In our study, western blot results showed no variation in the expression of key proteins, cleaved-caspase 3. Moreover, we also obtained the same results in qPCR testing. In addition, we analyzed the apoptosis cycle using flow cytometry and found that the number of apoptotic cells did not differ between the experimental and control groups. Thus, overexpression of TBX1 may not have a significant effect on C2C12 apoptosis.

TGF-β is an effective suppressor of differentiation in skeletal muscles, mainly through the Smad3 inhibition of the MyoD factor family, and interferes with MyoD/E protein isomerization, which mediates C2C12 myocyte muscle differentiation inhibition. 16 In addition to MyoD, TGF-β/Smad3 also target MEF2 to downregulate myogenic transcription. In the process of muscle formation, the family factor of muscle cell enhancement factor 2 (MEF2) is the second type of transcription factor essential for muscle development. MEF2 lacks myogenic activity, thus mainly acting through synergy for enhancing the transcription activity of MRFs; the two in the feedback loop adjust to each other. 27 Previous researches have found that TGF-β/Smad3 downregulated the function of MEF2, inhibits myocytogens independent from E-box expression, and prevents connected MyoD-E47 dimers from indirectly activating transcription through MEF2 binding sites. In addition, Smad3 interferes with the association of GRIP-1, an MEF2 co-activator, with MEF2C, thereby reducing the transcription activity of MEF2C. 32

TBX1 is the regulatory factor of myogenic differentiation, which mainly relies on transcription. In vitro and out-of-body experimental evidence suggests that TBX1 reduces VEGFR3 levels by interacting with T-box binding elements. 33 On the contrary, TBX1 can also prevent Smad1–Smad4 interaction by negatively adjusting the BMP–Smad1 pathway by combining Smad1. 34 TBX1 interacts with a variety of factors and regulates downstream genes to regulate muscle-derived differentiation. MEF2C is a downstream factor of TBX1; its expression is negatively correlated with TBX1 dose.19,35 In this study, we detected an increase in Smad2/3 and in phosphorylation expression levels in stable cells that expressed TBX1. Treatment with Smad3 inhibitor (SIS3) increased the expression levels of MyHC and MyoG in TBX1 overexpressing and wild-type C2C12 cells. Zhang et al. 36 also showed that pretreatment with SIS3 enhanced myoblast differentiation and increased the expression levels of MyoD and myoG. Significantly, Tbx1 overexpressing cells treated with SIS3 did not completely recover to the expression levels of wild-type cells, indicating that TBX1 reduced myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells by upregulating Smad3 and may not depend only on Smad3.

Previous studies have indicated that Tbx1 is a regulator of upstream events in branchiomeric myogenesis.7,15 In this study, we explored the function of Tbx1 in somitic myogenesis and found that TBX1 inhibited cell proliferation and muscle differentiation by increasing the expression levels of Smad2 and Smad3, as well as downregulating the expression level of MEF2C, which is expected to provide new potential targets for the treatment of DMD. In addition, we speculated that the expression of TBX1 regulated muscle differentiation in two ways: (1) TBX1 may further activate phosphorylation by enhancing Smad2/3 expression, while reducing the transcription activity of MEF2C. In addition, Smad2/3 interacts with the MyoD-bHLH domain by interfering with functional MyoD/E protein isomer formation, thus blocking transcription activation of downstream MyoG factors and inhibiting muscle formation; (2) overexpression of TBX1 independent from E-box expression directly or indirectly regulates the transcription activity of MEF2C and reduces the transcription activity of MRFs through a negative feedback loop, thus affecting myocellular production and inhibiting muscle formation.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-ebm-10.1177_15353702221112087 for TBX1 regulates myogenic differentiation by activating the TGFβ-Smad2/3 pathway in myoblasts by Haimei Cen, Hong Luo, Bin Luo, Pin Fan, Yusheng Zhang and Yu Zhang in Experimental Biology and Medicine

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: H.C. and H.L. designed and performed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; B.L. and P.F. performed experiments and helped with interpretation of the data. Y.Z. contributed with experimental design, interpretation of the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81801246), the Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Plan (grant no. 2017A020215094), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant nos. 2018A030313636 and 2020A1515011249), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. 21620406).

ORCID iD: Yu Zhang  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3239-3796

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3239-3796

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Bushby K, Finkel R, Birnkrant DJ, Case LE, Clemens PR, Cripe L, Kaul A, Kinnett K, McDonald C, Pandya S, Poysky J, Shapiro F, Tomezsko J, Constantin C, DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and pharmacological and psychosocial management. Lancet Neurol 2010; 9:77–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kapsa R, Kornberg AJ, Byrne E. Novel therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Lancet Neurol 2003;2:299–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iftikhar M, Frey J, Shohan MJ, Malek S, Mousa SA. Current and emerging therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy. Pharmacol Ther 2021;220:107719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yagi H, Furutani Y, Hamada H, Sasaki T, Asakawa S, Minoshima S, Ichida F, Joo K, Kimura M, Imamura S, Kamatani N, Momma K, Takao A, Nakazawa M, Shimizu N, Matsuoka R. Role of TBX1 in human del22q11.2 syndrome. Lancet 2003;362:1366–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fulcoli FG, Franzese M, Liu X, Zhang Z, Angelini C, Baldini A. Rebalancing gene haploinsufficiency in vivo by targeting chromatin. Nat Commun 2016;7:11688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Racedo SE, Hasten E, Lin M, Devakanmalai GS, Guo T, Ozbudak EM, Cai CL, Zheng D, Morrow BE. Reduced dosage of beta-catenin provides significant rescue of cardiac outflow tract anomalies in a Tbx1 conditional null mouse model of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. PLoS Genet 2017;13:e1006687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kelly RG, Jerome-Majewska LA, Papaioannou VE. The del22q11.2 candidate gene Tbx1 regulates branchiomeric myogenesis. Human Molecular Genetics 2004;13:2829–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin GF, Geng X, Chen Y, Qu B, Wang F, Hu R, Ding X. T-box binding site mediates the dorsal activation of myf-5 in Xenopus gastrula embryos. Dev Dyn 2003;226:51–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu H, Morishima M, Wylie JN, Schwartz RJ, Bruneau BG, Lindsay EA, Baldini A. Tbx1 has a dual role in the morphogenesis of the cardiac outflow tract. Development 2004;131:3217–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang Z, Huynh T, Baldini A. Mesodermal expression of Tbx1 is necessary and sufficient for pharyngeal arch and cardiac outflow tract development. Development 2006;133:3587–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dastjerdi A, Robson L, Walker R, Hadley J, Zhang Z, Rodriguez-Niedenführ M, Ataliotis P, Baldini A, Scambler P, Francis-West P. Tbx1 regulation of myogenic differentiation in the limb and cranial mesoderm. Dev Dyn 2007;236:353–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Verdelli C, Avagliano L, Guarnieri V, Cetani F, Ferrero S, Vicentini L, Beretta E, Scillitani A, Creo P, Bulfamante GP, Vaira V, Corbetta S. Expression, function, and regulation of the embryonic transcription factor TBX1 in parathyroid tumors. Lab Invest 2017;97:1488–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caprio C, Varricchio S, Bilio M, Feo F, Ferrentino R, Russo D, Staibano S, Alfano D, Missero C, Ilardi G, Baldini A. TBX1 and basal cell carcinoma: expression and interactions with Gli2 and Dvl2 signaling. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ronneberg JA, Fleischer T, Solvang HK, Nordgard SH, Edvardsen H, Potapenko I, Nebdal D, Daviaud C, Gut I, Bukholm I, Naume B, Borresen-Dale AL, Tost J, Kristensen V. Methylation profiling with a panel of cancer related genes: association with estrogen receptor, TP53 mutation status and expression subtypes in sporadic breast cancer. Mol Oncol 2011;5:61–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grifone R, Jarry T, Dandonneau M, Grenier J, Duprez D, Kelly RG. Properties of branchiomeric and somite-derived muscle development in Tbx1 mutant embryos. Dev Dyn 2008;237:3071–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu D, Black BL, Derynck R. TGF-beta inhibits muscle differentiation through functional repression of myogenic transcription factors by Smad3. Genes Dev 2001;15:2950–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miyazawa K, Miyazono K. Regulation of TGF-beta family signaling by inhibitory Smads. Cold Spr Harbor Persp Biol 2017;9:a022095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wrighton KH, Lin X, Feng XH. Phospho-control of TGF-beta superfamily signaling. Cell Res 2009;19:8–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pane LS, Zhang Z, Ferrentino R, Huynh T, Cutillo L, Baldini A. Tbx1 is a negative modulator of Mef2c. Hum Mol Genet 2012;21:2485–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ling M, Quan L, Lai X, Lang L, Li F, Yang X, Fu Y, Feng S, Yi X, Zhu C, Gao P, Zhu X, Wang L, Shu G, Jiang Q, Wang S. VEGFB promotes myoblasts proliferation and differentiation through VEGFR1-PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:13352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Li Y, Cao J, Zhang H, Chen M, Wang L, Zhang C. Long-term engraftment of myogenic progenitors from adipose-derived stem cells and muscle regeneration in dystrophic mice. Hum Mol Genet 2015;24:6029–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abdelmoez AM, Sardón Puig L, Smith JAB, Gabriel BM, Savikj M, Dollet L, Chibalin AV, Krook A, Zierath JR, Pillon NJ. Comparative profiling of skeletal muscle models reveals heterogeneity of transcriptome and metabolism. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2020;318:C615–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cui J, Zhang Y, Ren X, Jin L, Zhang H. TBX1 Functions as a tumor activator in prostate cancer by promoting ribosome RNA gene transcription. Front Oncol 2020;10:616173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang N, Li Y, Wei J, Pu J, Liu R, Yang Q, Guan H, Shi B, Hou P, Ji M. TBX1 functions as a tumor suppressor in thyroid cancer through inhibiting the activities of the PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways. Thyroid 2019;29:378–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Funato N, Nakamura M, Richardson JA, Srivastava D, Yanagisawa H. Tbx1 regulates oral epithelial adhesion and palatal development. Hum Mol Genet 2012;21:2524–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arnold JS, Werling U, Braunstein EM, Liao J, Nowotschin S, Edelmann W, Hebert JM, Morrow BE. Inactivation of Tbx1 in the pharyngeal endoderm results in 22q11DS malformations. Development 2006;133:977–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Asfour HA, Allouh MZ, Said RS. Myogenic regulatory factors: the orchestrators of myogenesis after 30 years of discovery. Exp Biol Med 2018;243:118–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moncaut N, Cross JW, Siligan C, Keith A, Taylor K, Rigby PW, Carvajal JJ. Musculin and TCF21 coordinate the maintenance of myogenic regulatory factor expression levels during mouse craniofacial development. Development 2012;139:958–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jiang H, Li L, Li-Ling J, Qiu G, Niu Z, Jiang H, Li Y, Huang Y, Sun K. Increased Tbx1 expression may play a role via TGFbeta-Smad2/3 signaling pathway in acute kidney injury induced by gentamicin. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014;7:1595–605 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu H, Song M, Sun X, Zhang X, Miao H, Wang Y. T-box transcription factor TBX1, targeted by microRNA-6727-5p, inhibits cell growth and enhances cisplatin chemosensitivity of cervical cancer cells through AKT and MAPK pathways. Bioengineered 2021;12:565–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kong P, Racedo SE, Macchiarulo S, Hu Z, Carpenter C, Guo T, Wang T, Zheng D, Morrow BE. Tbx1 is required autonomously for cell survival and fate in the pharyngeal core mesoderm to form the muscles of mastication. Human Molecular Genetics 2014;23:4215–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu D, Kang JS, Derynck R. TGF-beta-activated Smad3 represses MEF2-dependent transcription in myogenic differentiation. EMBO J 2004;23:1557–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen L, Mupo A, Huynh T, Cioffi S, Woods M, Jin C, McKeehan W, Thompson-Snipes L, Baldini A, Illingworth E. Tbx1 regulates Vegfr3 and is required for lymphatic vessel development. J Cell Biol 2010;189:417–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fu Y, Li F, Zhao DY, Zhang JS, Lv Y, Li-Ling J. Interaction between Tbx1 and Hoxd10 and connection with TGFbeta-BMP signal pathway during kidney development. Gene 2014;536:197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Motohashi N, Uezumi A, Asakura A, Ikemoto-Uezumi M, Mori S, Mizunoe Y, Takashima R, Miyagoe-Suzuki Y, Takeda S, Shigemoto K. Tbx1 regulates inherited metabolic and myogenic abilities of progenitor cells derived from slow- and fast-type muscle. Cell Death Differ 2019;26:1024–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang P, Li W, Wang L, Liu H, Gong J, Wang F, Chen X. Salidroside inhibits myogenesis by modulating p-Smad3-induced Myf5 transcription. Front Pharmacol 2018;9:209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-ebm-10.1177_15353702221112087 for TBX1 regulates myogenic differentiation by activating the TGFβ-Smad2/3 pathway in myoblasts by Haimei Cen, Hong Luo, Bin Luo, Pin Fan, Yusheng Zhang and Yu Zhang in Experimental Biology and Medicine