Abstract

The sarcoid-like reaction is a rare autoinflammatory disease that can affect lymph nodes or organs but does not meet the diagnostic criteria for systemic sarcoidosis. Several drug classes have been associated with the development of a systemic sarcoid-like reaction, which defines drug-induced sarcoidosis-like reactions and can affect a single organ. Anti-CD20 antibodies (rituximab) have rarely been reported as responsible for this reaction and this adverse effect has mainly been described during the treatment of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. We report a unique case of a sarcoid-like reaction complicating rituximab following the treatment of a mantle cell lymphoma and interesting only the kidney. The 60-year-old patient presented with severe acute renal failure 6 months after the end of his r-CHOP protocol and the urgent renal biopsy revealed acute interstitial nephritis rich in granulomas without caseous necrosis. After ruling out other causes of granulomatous nephritis, a sarcoid-like reaction was retained since infiltration was limited to the kidney. The temporal relationship between rituximab administration and the sarcoid-like reaction onset in our patient supported the diagnosis of a rituximab-induced sarcoidosis-like reaction. Oral corticosteroid treatment led to rapid and lasting improvement in renal function. Clinicians should be warned of this adverse effect and regular and prolonged monitoring of renal function should be recommended during the follow-up of patients after the end of treatment with rituximab.

Keywords: rituximab, granuloma, interstitial nephritis, kidney, sarcoidosis

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory multisystem disease with unknown etiology characterized by the presence of non-caseating epithelioid cell granulomas in involved tissues (El Jammal et al., 2020).

Sarcoid-like reactions (SLRs) are an autoinflammatory cause of mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy which can also affect other lymphadenopathy and organs but do not meet the diagnostic criteria for systemic sarcoidosis (Winkelmann et al., 2021) This rare phenomenon has been reported primarily in patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma or solid tumors (especially melanoma) receiving immunotherapy and chemotherapy. Cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) are extremely rare (Winkelmann et al., 2021).

We report an uncommon case of SLR related to rituximab and affecting only the kidney in a patient who received chemotherapy with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) and rituximab for mantle cell lymphoma, a rare and aggressive form of NHL that preferentially affects men (sex ratio M/F of 6.5; Decaudin et al., 2000).

Case Report

A 60-year-old man with a history of gout and prostate adenoma consulted in August 2019 for deterioration of the general condition and a significant weight loss of 35 kg. Clinical examination and radiological investigation found multiple lymphadenopathies (cervical, axillary, inguinal, mediastinal, abdominal, intra, and retroperitoneal) associated with hepatosplenomegaly. The biopsy of inguinal lymphadenopathy showed a blast variant mantle cell lymphoma. Chemotherapy with CHOP and rituximab therapy (r-CHOP) were initiated and he underwent six cycles of chemotherapy and four cycles of rituximab (protocol of 375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 weeks) with a good clinical and radiological response always keeping a normal renal function. Six months after the chemo- and immunotherapy completion, the patient suffered epigastralgia and vomiting with balance sheet deterioration of renal function (creatinine at 680 µmol /L).

He was on examination hemodynamically and respiratory stable with a diuresis at 1.5 L/day. There was no peripheral lymphadenopathy.

Biology showed no fluid electrolyte disturbance, normochromic normocytic anemia at 9.1 g/dL, and 24 hr proteinuria at 1.76 g.

The tumor markers were negative as well as the immunological assessment, which included antinuclear, anti-glomerular basement membrane, and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). Abdominal ultrasound showed kidneys of normal size. There was no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly on computed tomography.

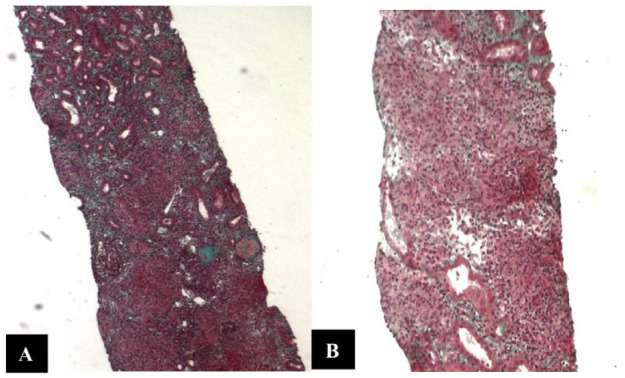

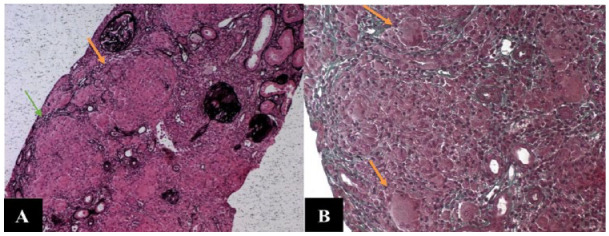

The acute kidney injury rapidly worsened (creatinine 996 then 1042 µmol/L) and remained unexplained, indicating an urgent renal biopsy which was performed within 72 hr after admission. The biopsy showed severe acute interstitial nephritis made of lymphocytic infiltrate with many non-necrotizing granulomas (Figures 1 and 2). These findings were strongly suggestive of sarcoidosis. Therefore, in the absence of recent medication and after ruling out other causes of granulomatous interstitial nephritis (GIN), sarcoidosis was the most likely diagnosis. Indeed, the negativity of the ANCA eliminated Wegener’s granulomatosis and tuberculous interstitial nephritis was ruled out by the absence of Koch’s bacillus in urine and non-necrotizing granulomas.

Figure 1.

Microscopic Examination of Renal Biopsy Showing a Heavy Lymphocytic Infiltrate Within Interstitium. (A) Trichrome Staining ×40 and (B) Trichome Staining ×100

Figure 2.

High Magnification of Non-necrotizing Epithelioid and Giant Cell Granulomas Within the Interstitium. Granulomas (A, arrows), Multinucleated Giant Cells (B, arrows). (A) Reticulin Staining ×100 and (B) Trichrome Staining ×200

The assessment of sarcoidosis did not show extrarenal involvement. Indeed, the dermatological examination did not find skin lesions, the ophthalmological examination was without abnormality, the thoracic-abdominal-pelvic scan did not show any signs of sarcoidosis, and serum calcium, vitamin D, and converting enzyme levels were normal.

Oral corticosteroid therapy was initiated at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day per os with a favorable outcome and significantly improved renal function (creatinine from 1042 to 570 µmol/L in 8 days and to 150 µmol/L in 15 days).

At follow-ups 6 and 9 months later, renal function was stable with plasma creatinine around 120 µmol/L. He has not had a relapse of his lymphoma or other organ involvement of SLR.

Discussion

We reported the case of a patient who presented a severe acute renal failure secondary to GIN 6 months after the end of an r-CHOP treatment for mantle lymphoma.

Granulomatous interstitial nephritis is a rare histological diagnosis that occurs in 0.5% to 0.9% of biopsies (Joss et al., 2007). It is associated with medication, infections, sarcoidosis, crystallization, paraproteinemia, and Wegener’s granulomatosis, and is also observed in idiopathic patterns (Joss et al., 2007).

Based on the overall clinical picture and the histological appearance of the granulomas strongly suggestive of sarcoidosis, we retained an SLR in the absence of evidence of systemic involvement of the granulomatous infiltration.

Sarcoid-like reaction is characterized by the development of a granulomatous reaction that is indistinguishable from sarcoidosis. Multiple drug classes have been associated with SLR, which defines drug-induced sarcoidosis-like reactions (DISRs; Miedema & Nunes, 2021) and may affect a single organ such as the skin or the spleen (Reilly et al., 2007; Vesely et al., 2020).

The onset of DISRs is not necessarily concomitant with treatment and may occur months after discontinuation of the drug (Vesely et al., 2020).

Most reported medications can be classified as antiretroviral combination therapies, tumor necrosis factor-α antagonists, interferons, and immune checkpoint inhibitors (Miedema & Nunes, 2021).

The reported patient presented an SRL following CHOP and rituximab therapy.

Limited literature described DISRs as an uncommon adverse effect of rituximab when prescribed alone without chemotherapy (Galimberti & Fernandez, 2016; Pescitelli et al., 2017; Vesely et al., 2020), while we did not find any study describing this adverse effect associated with CHOP-based chemotherapy prescribed alone. This would incriminate rituximab in the induction of the DISRs in patients who received an r-CHOP protocol like our patient.

The temporal relationship between rituximab administration and SLR onset in our patient supports the diagnosis of rituximab-DISRs. Indeed, B cells that are targeted by rituximab play an important pathogenic role in sarcoidosis (Eisenberg & Albert, 2006; Galimberti & Fernandez, 2016; Mouquet et al., 2008).

Rituximab binds to CD20-positive B lymphocytes ranging from pre-B cells to early plasmablasts, resulting in complete B-cell depletion 21 days after infusion. Four to 6 months after that rituximab clearance occurs coinciding with a peripheral B-cell repopulation which is higher than before treatment, and the re-establishment of a naive B-cell pool (Eisenberg & Albert, 2006; Mouquet et al., 2008). Thus, our patient would have been early in the process of repopulation of peripheral B cells at the time of SLR onset, approximately 6 months after his last rituximab infusion.

London et al. (2014) described the development of sarcoidosis in 39 patients treated for lymphoma (14 cases published for the first time and 25 cases from a literature review). About one-third (13/39) of these patients received rituximab, expressing concern about drug-induced sarcoidosis associated with rituximab. The time from rituximab to the onset of sarcoidosis was not reported in this study, but the median time from the diagnosis of lymphoma to the diagnosis of sarcoidosis was 18 months. This ranged from just under 3 months to over 24 months.

Immunotherapy-DISRs are usually associated with airway and skin lesions. Other clinical features include fever, extrathoracic lymph node swelling, uveitis, hypercalcemia, nervous system, hepatic spleen, and muscle and bone joint involvement (Miedema & Nunes, 2021). The organs involved in the study of London et al. were the lung and the lymph nodes. No kidney involvement was described in the literature, meaning this is the first reported case of renal SLR in the context of rituximab-DISRs.

The series of London et al. counted only seven cases of NHL, and to the best of our knowledge, it was not reported, after this study of SLR associated with rituximab in patients with NHL and especially mantle cells. The only study found in the literature focusing on mantle cell lymphoma and sarcoidosis described a patient who developed mantle cell lymphoma after several years of evolution of sarcoidosis (Krause & Sohn, 2020).

The SLR responded well to oral corticosteroids at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day in our patient. In the series by London et al., 14 patients received prednisone at a dose of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day with partial to complete remission. Only two presented a relapse of the granulomatous infiltration. Corticosteroids would be therefore an effective treatment for this pathology.

Conclusion

We presented a one-of-a-kind case of an SLR involving only the kidney and secondary to rituximab in a 60-year-old patient after r-CHOP for mantle cell lymphoma. Clinicians should be aware of this paradoxical class effect and prolonged monitoring of renal function should be recommended during the follow-up of patients after the end of treatment with rituximab.

Early renal biopsy is indispensable for fast and adequate diagnosis, knowing that the pathology would respond well to oral corticosteroid therapy.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors have contributed to the manuscript in significant ways, reviewed, and agreed upon the manuscript. S.M., D.Z., A.A., and R.D. defined the research theme. S.M., R.B., M.M., and W.S. designed the methods and experiments; carried out the laboratory experiments; analyzed data; and interpreted the results. A.A., A.F., N.A., A.J., and N.B.A. discussed the interpretation and presentation.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Given the nature of the article, a case report, no ethical approval was required.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

ORCID iD: Sanda Mrabet  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1769-5422

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1769-5422

References

- Decaudin D., Salanoubat C., Carde P. (2000). Is mantle cell lymphoma a sex-related disease? Leukemia & Lymphoma, 37(1–2), 181–184. 10.3109/10428190009057643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg R., Albert D. (2006). B-cell targeted therapies in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature Clinical Practice Rheumatology, 2(1), 20–27. 10.1038/ncprheum0042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Jammal T., Jamilloux Y., Gerfaud-Valentin M., Valeyre D., Sève P. (2020). Refractory sarcoidosis: A review. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management, 16, 323–345. 10.2147/TCRM.S192922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimberti F., Fernandez A. P. (2016). Sarcoidosis following successful treatment of pemphigus vulgaris with rituximab: A rituximab-induced reaction further supporting B-cell contribution to sarcoidosis pathogenesis? Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, 41(4), 413–416. 10.1111/ced.12793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joss N., Morris S., Young B., Geddes C. (2007). Granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 2(2), 222–230. 10.2215/CJN.01790506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause J. R., Sohn A. (2020). Coexisting sarcoidosis and occult mantle cell lymphoma. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, 33(4), 651–652. 10.1080/08998280.2020.1792746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London J., Grados A., Fermé C., Charmillon A., Maurier F., Deau B., Crickx E., Brice P., Chapelon-Abric C., Haioun C., Burroni B., Alifano M., Le Jeunne C., Guillevin L., Costedoat-Chalumeau N., Schleinitz N., Mouthon L., Terrier B. (2014). Sarcoidosis occurring after lymphoma: Report of 14 patients and review of the literature. Medicine, 93(21), Article e121. 10.1097/MD.0000000000000121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miedema J., Nunes H. (2021). Drug-induced sarcoidosis-like reactions. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine, 27(5), 439–447. 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouquet H., Musette P., Gougeon M.-L., Jacquot S., Lemercier B., Lim A., Gilbert D., Dutot I., Roujeau J. C., D’Incan M., Bedane C., Tron F., Joly P. (2008). B-cell depletion immunotherapy in pemphigus: Effects on cellular and humoral immune responses. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 128(12), 2859–2869. 10.1038/jid.2008.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescitelli L., Emmi G., Tripo L., Lazzeri L., Urban M. L., Silvesri E., Vannucchi M., Prignano F. (2017). Cutaneous sarcoidosis during rituximab treatment for microscopic polyangiitis: An uncommon adverse effect? European Journal of Dermatology, 27(6), 667–668. 10.1684/ejd.2017.3143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly T. B., Schuster D. M., Starsiak M. D., Kost C. B., Halkar R. K. (2007). Sarcoid-like reaction in the spleen following chemotherapy for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clinical Nuclear Medicine, 32(7), 569–571. 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3180646aad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesely N. C., Thomas R. M., Rudnick E., Longo M. I. (2020). Scar sarcoidosis following rituximab therapy. Dermatologic Therapy, 33(6), Article e13693. 10.1111/dth.13693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann M., Rejeski K., Subklewe M., Ricke J., Unterrainer M., Rudelius M., Kunz W. G. (2021). Sarcoid-like reaction in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma—A diagnostic challenge for deauville scoring on 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging. Diagnostics, 11(6), 1009. 10.3390/diagnostics11061009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]