Abstract

Objective

Our goal is to establish the feasibility of using an artificially intelligent chatbot in diverse healthcare settings to promote COVID-19 vaccination.

Methods

We designed an artificially intelligent chatbot deployed via short message services and web-based platforms. Guided by communication theories, we developed persuasive messages to respond to users’ COVID-19-related questions and encourage vaccination. We implemented the system in healthcare settings in the U.S. between April 2021 and March 2022 and logged the number of users, topics discussed, and information on system accuracy in matching responses to user intents. We regularly reviewed queries and reclassified responses to better match responses to query intents as COVID-19 events evolved.

Results

A total of 2479 users engaged with the system, exchanging 3994 COVID-19 relevant messages. The most popular queries to the system were about boosters and where to get a vaccine. The system's accuracy rate in matching responses to user queries ranged from 54% to 91.1%. Accuracy lagged when new information related to COVID emerged, such as that related to the Delta variant. Accuracy increased when we added new content to the system.

Conclusions

It is feasible and potentially valuable to create chatbot systems using AI to facilitate access to current, accurate, complete, and persuasive information on infectious diseases. Such a system can be adapted to use with patients and populations needing detailed information and motivation to act in support of their health.

Keywords: Artificial intelligent, chatbot, COVID-19 pandemic, vaccine hesitancy, feasibility

Introduction

As of April 2022, there have been over 80 million people infected with COVID-19 and over 984,000 deaths in the U.S., and 69.9% of the population eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine were fully vaccinated.1,2 Despite the strong evidence that vaccines can significantly reduce COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death, vaccine resistance and hesitancy still exist among U.S. populations.3 People who remain unvaccinated tend to be younger, have lower levels of educational attainment, and identify as Republicans.4 Main reasons for hesitancy include a lack of complete and correct information about the types of vaccines available, their level of effectiveness and safety for diverse groups, lack of trust, suspicions about the rapid development of vaccine technology, and concerns about the relatively new mRNA technology.5,6 Additional concerns have been exacerbated by myths and misinformation about vaccines.7 To achieve herd immunity and end the pandemic, a relatively high level of vaccination rate is required. Therefore, proactive COVID-19 educational programs are needed to raise awareness, address safety and efficacy concerns about the vaccine, correct myths, and increase positive attitudes and beliefs about COVID-19 vaccines. It is worth noting that people's attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines have varied across time, with greater hesitancy when vaccines were first introduced and reduced hesitancy as more and more people were vaccinated.8,9 Vaccination programs should consider the dynamic process of vaccine hesitancy, particularly given the uncertainty with the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus, vaccine and booster efficacy. Circumstances such as the pause and resumption of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine, breakthrough cases, and the Delta and Omicron variants require rapid adaptation and updating of messaging to ensure confidence and credibility in public health communication.

Healthcare workers play a critical role in communicating COVID-19 vaccination with patients and promoting vaccine acceptance.10 However, healthcare organizations tasked with primary care and vaccine delivery have found themselves besieged with calls and inquiries about vaccines,11 with queries focused initially on getting an appointment for vaccines before they were widely available and therefore restricted to priority populations, such as older adults.12 Staffing efforts to respond to these queries while maintaining care provision for other priority health concerns, such as screening for hypertension, is challenging. Evidence suggests many patients have forgone critical primary and preventive care, either because of social distancing mandates, fears of COVID infection, or limited staff to provide care given a focus on COVID treatment.13

Finding solutions that could help care providers simultaneously be responsive to queries about COVID and the COVID vaccines while also delivering high-quality primary care to address ongoing challenges with chronic and other infectious conditions has become a critical priority. Creative approaches should be used to manage clinical operations and relieve unproductive performance pressure (e.g. using digital tools to answer repetitive questions and facilitate 24/7 patient access to information).14 Technology-based solutions can offer opportunities to streamline and automate communications with correct, up-to-date, and complete information about COVID and COVID vaccines so that healthcare providers can either focus on more complex considerations related to COVID-19 or return their attention to other primary care priorities.

Interactive, user-centered, artificially intelligent (AI)-based conversational chatbots are emerging as a new strategy in health interventions to support healthy behaviors.15,16 AI chatbots, also called conversational agents or virtual assistants, are software applications based on machine learning (ML) and natural language processing (NLP) to simulate natural human conversations through text or voice interactions and automate tasks. ML is a particular type of AI that has the ability to learn on its own from data inputs, in our case the interactions between the system and users’ language, to optimize its performance over time.17 NLP helps interpret and process users’ input texts.18 This technology has become increasingly sophisticated, including for applications in healthcare delivery.19 Past research on chatbots has focused on finite-state systems (i.e. with a set of pre-determined scripts based on a finite library) rather than those using a more user-centered and resonant NLP system. Recent reports suggest strong provider support for using chatbots within healthcare delivery systems to increase access to care20 and that the NLP approach can be impactful on health behaviors, particularly when they are designed to respond to various user backgrounds, create a social presence during the engagement, and employ persuasive communication strategies.21 Chatbots have been widely used in the health domain for symptom checking or screening, triaging and managing medical services, mental health support, virtual consultation, and facilitating behavior changes.22–24

AI chatbots offer several advantages over other communication channels in delivering COVID-19 information and promoting vaccination. A chatbot is a cost-effective approach to delivering support that directly addresses questions or concerns and may facilitate long-term adherence to health promotion interventions. It can provide automated, immediate responses to users’ requests with reliable information, addressing the knowledge gap on COVID-19 vaccines and freeing clinic and public health staff to attend to skill-intensive tasks. Users can receive chatbot services at any time in any location. When delivered via text messages, chatbots can be highly accessible because of the nearly universal availability of mobile phones and the ubiquity of text messaging. In the U.S., 96% of adults own a cellphone,25 and 81% of them commonly use text messages to communicate.26 Text-based chatbots could serve as an inexpensive and scalable mechanism to reach a broad population—across the age spectrum, among racial and ethnic minorities, rural populations,27 people who are unhoused,28 people with low socioeconomic status as well as people with limited English proficiency.29 The chatbot system is also easy to be implemented on diverse online platforms, including social media, mobile phone apps, and websites, with the potential to be available in multiple languages. While chatbot messages delivered through mobile technologies may potentially reduce health disparities, it is worth noting that chatbot accessibility is contingent on digital literacy, Internet connection, trust of the source, and how chatbot messages are disseminated. Finally, the content delivered by chatbot systems can be regularly updated and revised as we gain new information or context that can facilitate message tailoring to increase relevance. Both the constant evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic and the global scale require utilization of systems with the capacity to quickly and continually adapt and update communications.30 Chatbot infrastructure can be deployed for circumstances when rapid communication and updates about COVID-19 vaccination are required to mitigate message decay.31 The update process entails a researcher-initiated mechanism, in which researchers manually input new information, update the content repository, monitor and adjust the matching rules, as well as an automatic self-learning mechanism, in which the chatbot, enabled by AI techniques, learns how new expressions of questions for intents should be classified so that every subsequent instance using similar expressions can be mapped correctly, making the system increasingly precise over time.

Although other chatbots have been developed to deliver COVID-19-related information (e.g. COVID-19 Risk Assessment Chatbot; Translators without Borders),32,33 most programs are not optimized to incorporate communication theories to make messages more resonant, and they do not attend to health literacy, language, and tailoring to ensure inclusion of populations facing disparities.34 To address this gap, we developed and tested the feasibility of using an automated, theory-based AI chatbot, with linguistically and culturally appropriate messages to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and promote vaccine uptake. This chatbot contains messages about the COVID-19 vaccines in users’ preferred language (English or Spanish).

In this proof-of-concept study, we describe the design and deployment within diverse healthcare settings of an AI COVID-19 vaccine promotion chatbot utilizing NLP to facilitate access to information and persuade users to vaccinate against COVID-19. We also assess the accuracy of the chatbot and users’ engagement with the chatbot to demonstrate the feasibility of integrating health communication strategies with technology to create more persuasive and influential digital health interventions.

Methods

Partnerships with primary healthcare delivery systems

The COVID-19 vaccine chatbot can deliver messages via short message services (SMS) (the textbot) and websites (the webbot). We endeavored to deploy our chatbot to persons facing disparities in COVID-19 outcomes, including those with higher infection and hospitalization rates, those with lower income, and ethnic minorities. We partnered with five healthcare delivery systems in the state of Colorado. Three of them serve patients across the Denver Metropolitan Area and the other two serve patients outside the Front Range. Each collaborating system is a Federally Qualified Health Center, providing healthcare services to lower-income and/or ethnically underserved patients. Over 75% of patients receiving care at clinics our chatbot supported are either uninsured or receive Medicaid or Medicare and about 62% are non-white (including Latino/Hispanic, Black/African American, American Indian, and Asian). The collaborating clinics utilized one or two strategies for deploying the system. First, each healthcare delivery system created an SMS message campaign alerting their patients that the chatbot was available to them as a resource, including the telephone number for engaging with the system. Additionally, two partnering healthcare systems providing services across 30 clinic sites also embedded a web-based version of the chatbot system on their webpage so that patients seeking information online could click on the webbot, which was the second strategy for deployment.

The textbot initiates the conversation with the following welcome message: “Hi! Welcome to the COVID-19 chatbot! We are working with your healthcare provider to answer questions you have about the COVID-19 vaccines. Please text ‘1’ in English. ¡Hola! ¡Bienvenido al chatbot COVID-19! Si quieres que responda tus preguntas en español, envía un mensaje de texto ‘2’.” Figure 1 demonstrates the initial and conversational interfaces of the webbot.

Figure 1.

The interface of the COVID-19 vaccine chatbot.

Development of the infrastructure for the AI chatbot

We began to build the chatbot system by categorizing anticipated “intents”—that is, the specific topics we believed people wanted to learn or ask about COVID-19 vaccines. To generate a comprehensive list of intents, we reviewed topics of frequently asked questions about COVID-19 vaccination listed on the websites of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) as well as other reputable clinical websites and news outlets. We generated 51 intents for the initial version of the system, covering topics from vaccine safety, effectiveness, ingredients, side effects, eligibility, dosing and schedule, booking, procedures, documentation, and locations, to misinformation (see the Appendix).

Based on the initial set of intents, we further generated multiple variations on questions that users could ask related to each intent so the system could be “trained” to infer the intent of a query based on many possible ways of asking a query. For example, one user may ask “what are the side effects of the COVID vaccine?,” while another might ask, “what symptoms can I expect to have after I get the vaccine?,” and both queries would be matched to the “side effects” intent. To generate a pool of question variations for each intent, we relied on the Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) crowdsourcing platform. This platform enables us to take the advantage of collective intelligence in gathering needed information and outsources the question-generation task to people who can complete it online, accelerating the data collection process.35 MTurk has been used as a reliable and cost-effective tool to conduct health-related research.36 We first conducted the crowdsourcing task in December 2020 and three more waves when new intents about COVID-19 vaccines emerged. For each wave, we asked 35 participants to respond to our survey published on MTurk. Participants were required to be in the United States, have completed at least 50 crowdsourcing tasks on MTurk, and have an approval rate greater than 98% to ensure response quality. We asked participants to write down three to five questions that come to their minds when thinking about various COVID-19 vaccine-related topics. For example, “please list the top three questions you’d like to ask regarding the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines, and you can write more questions if you like.” After collecting crowdsourced questions, the research team screened each question that MTurk workers generated—deleting completely irrelevant questions and reclassifying questions that were not listed under the appropriate topic. This resulted in having at least 18 variations on queries for each intent (M = 57.34; Range = 18–188; SD = 40.79). This allowed the system to have enough initial data to learn how to interpret user questions, tolerate misspellings, grammar mistakes, and slangs, and recognize the underlying intent of each question. The chatbot did not rely on a simple dictionary look-up process to correct the spelling of a word. Instead, it used a combination of Natural Language Processing and probabilistic models to assess whether a term was, in fact, misspelled or grammatically wrong and should be corrected.

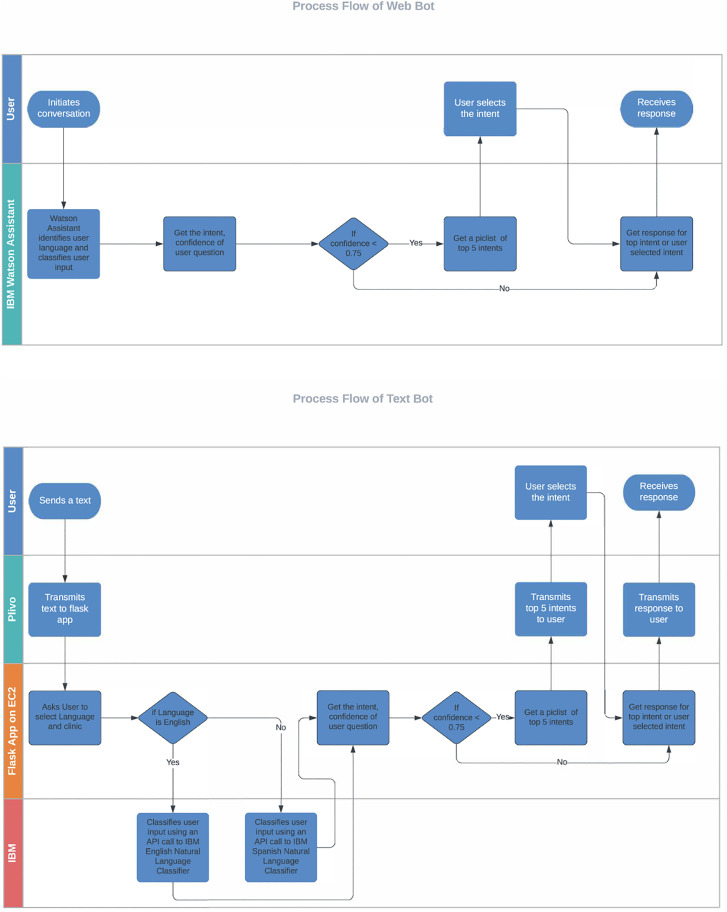

Using an NLP and ML pipeline, user inputs were probabilistically assigned to existing question intents. A response or an answer matched to the user's question intent was then retrieved from the message library. Only one response was matched to each intent. When the system could not match the user input to a question intent with confidence (< 75%), it would reply with a fixed choice (also called a “pick list”) set of responses, for example, “I think you are asking about one of these four topics: (a) side effects, (b) vaccine eligibility, (c) cost of the vaccine, (d) locations to get a vaccine. Please type the letter corresponding to the topic you wish to explore or try your question again.” The chatbot would prioritize the top four intents that had the highest prediction score and were most likely to match the user's question. Listing more intents would not be practical in the limited space afforded through text messaging or the clinics' websites. We tested and optimized multiple versions of the NLP/ML pipeline responsible for identifying the intent of user questions. Our goal was to correctly match user input questions to the intent of the question at least 85% of the time. Figure 2 demonstrates the overall process flow of the textbot and the webbot.

Figure 2.

Process flow of the webbot and the textbot.

The textbot is functional and hosted in a scalable cloud environment using Amazon Web Services EC2. The web chatbot is hosted using the IBM Watson Assistant. The ML and NLP pipelines for the textbot were built using Python 3.8 with NumPy, Pandas, and scikit-learn, flask, npm, pm2 Python modules. Both the webbot and textbot had been load-tested to ensure adequate performance in response time to messages at different times of the day.

Development of theory-based chatbot response messages

We developed a library of response messages in English and Spanish guided by the Integrated Theory of mHealth,37 which proposes three critical considerations when designing mHealth interventions—access, engagement, and facilitating behavioral change. The system is accessible through SMSs and on various health systems’ websites. To improve user engagement and message impact, we adapted information and guidelines from CDC and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and optimized the content based on Cialdini's principles of persuasion.38 The most relevant principles are (1) citing authorities (CDC, WHO, FDA, and healthcare workers) and research evidence to demonstrate credibility; (2) showing social proof or consensus of doing a behavior, such as the majority of the community members have already vaccinated; (3) inviting people to make a commitment; (4) and activating a sense of reciprocation by letting people feel socially obliged to get vaccinated in return for volunteers and others’ efforts in reducing the spread of the virus. Because research indicates that messages with a gain-frame are generally more persuasive than those with a loss-frame in promoting preventive health behaviors (although this effect may be moderated by content type),39–41 we also framed the messages to focus on positive outcomes of vaccination, including (5) getting lives back and (6) protecting loved ones. We calculated the Flesch–Kincaid readability score to ensure messages remain at or below an eighth-grade reading level. To facilitate the vaccination behavior, our library of responses addressed the key constructs proposed by the Integrated Behavior Model and Social Cognitive Theory,42,43 including increasing knowledge and awareness of COVID-19 vaccines (e.g. availability of and differences between various types of COVID-19 vaccines), forming positive attitudes and beliefs (e.g. correcting misbeliefs), understanding social norms (e.g. the total number of people fully vaccinated to date), and enhancing self-efficacy (e.g. how and where to get the vaccine). These are effective pathways to reduce vaccine hesitancy and promote vaccination behavior.6,44 We validated the content by cross-checking at least two credible sources (e.g. CDC, WHO, FDA, Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment, The New York Times) to ensure information accuracy. Target audiences were also involved in the design process. We conducted in-depth interviews with 18 ethnic minority participants to understand their attitudes and concerns about COVID-19 vaccines.45 The research team initially created two or three versions of responses for each intent and then randomly selected 25 draft responses from the repository for each participant to evaluate and provide comments. We asked what they liked or disliked about the initial version of the messages and what suggestions they had for optimizing the messages to be more readable and culturally relevant. We picked the preferred responses for each intent and further revised them based on the participants’ advice. Sample response messages are demonstrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of theory-based chatbot responses to promote COVID-19 vaccination.

| Intents | Theoretical construct | Persuasive strategies | Responses | Spanish version |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity after vaccination | To enhance self-efficacy | Authority & Getting lives back | You will be fully protected from the vaccine 2 to 4 weeks after your final dose. You may have some side effects after getting the shot, which are normal signs that your body is building protection. These side effects may affect your ability to do daily activities, but they should go away in a few days. Some people have no side effects. Doctors recommend not to take excessive alcohol after getting the vaccine as it can impair your immune system and affect vaccine efficacy. Because of the Delta variant, the CDC recommends wearing a mask indoors in areas where there is substantial COVID-19 transmission, which is in most of the U.S. Keep washing your hands too! The more people who vaccinate, the sooner we all can get our lives back again. | Estará completamente protegido de la vacuna de 2 a 4 semanas después de su última dosis. Es posible que tenga algunos efectos secundarios después de recibir la inyección, que son signos normales de que su cuerpo está creando protección. Estos efectos secundarios pueden afectar su capacidad para realizar las actividades diarias, pero deberían desaparecer en unos pocos días. Algunas personas no tienen efectos secundarios. Los médicos recomiendan no consumir alcohol en exceso después de recibir la vacuna, ya que puede dañar su sistema inmunológico y afectar la eficacia de la vacuna. Debido a la variante Delta, los de la CDC recomiendan usar una máscara en espacios cerrados en áreas donde hay una transmisión sustancial de COVID-19, que es en la mayor parte de los EE. UU. ¡Siga lavándose las manos también! Cuantas más personas se vacunen, mas rápido podremos recuperar nuestras vidas. |

| Total number of people fully vaccinated to date | To understand social norms | Social proof | More than 170 million people in the US are fully vaccinated—great news, because this gets us all closer to relaxing COVID restrictions. Join them to get vaccinated and protect your community. | Más de 170 millones de personas en los EE. UU. están completamente vacunadas: excelentes noticias, porque esto nos acerca a todos a relajar las restricciones de COVID. Únase a ellos para vacunarse y proteger a su comunidad. |

| Eligibility for vaccine | To enhance self-efficacy; understand social norms | Commitment & Getting lives back | In Colorado, anyone age 12 or older can get vaccinated, and you can get a gift card to Walmart valued at $100 while supplies last for your first or second shot! Make a commitment to get your vaccine as soon as you can and tell people around you that they can get their vaccine now! You do not need to be a resident or U.S. citizen to get the vaccine. We need as many people to vaccinate as we can to stop COVID-19 and return to the activities and people we are missing. Go to this website or call 1-877-CO-VAX CO (1-877-268-2926) to register for a shot. | En Colorado, cualquier persona de 12 años o más puede vacunarse, ¡y puede obtener una tarjeta de regalo de Walmart valorada en $ 100 (hasta que se termine) para su primera o segunda vacuna! ¡Comprométase a vacunarse lo antes posible y dígales a las personas que lo rodean que pueden vacunarse ahora! No es necesario ser residente o ciudadano estadounidense para recibir la vacuna. Necesitamos vacunar a tantas personas como podamos para detener el COVID-19 y volver a las actividades y volver a ver a las personas que extrañamos. Visite este sitio web o llame al 1-877-CO-VAX CO (1-877-268-2926) para registrarse para recibir una vacuna. |

| Ethnic minorities and COVID vaccination | To understand social norms | Reciprocation | Many of the more than 100,000 volunteers who were part of the research to develop the vaccines were from the Black, Latinx, and American Indian communities, where the levels of illness and death from COVID have been much higher than for other groups. Their involvement was an important reason we have safe and effective vaccines today. | Muchos de los más de 100,000 voluntarios que formaron parte de la investigación para desarrollar las vacunas eran de las comunidades afroamericanas, latinas e indios americanos, donde los niveles de enfermedad y muerte por COVID han sido mucho más altos que para otros grupos. Su participación fue una razón importante por la que hoy tenemos vacunas seguras y efectivas. |

| Death from COVID or vaccines | To increase knowledge and awareness; correct misbeliefs; enhance self-efficacy; | Social proof & Commitment | Deaths after COVID-19 vaccination are extremely rare and there is no evidence that the vaccine is the cause. COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective in protecting you from serious illness and death. More than 95 out of every 100 people hospitalized with COVID-19 and 99 of every 100 people who died from COVID are not vaccinated. If you have not been vaccinated, check https://www.vaccines.gov/ to find a COVID-19 vaccine near you and get the shot as soon as you can. | Las muertes después de la vacunación COVID-19 son extremadamente raras y no hay evidencia de que la vacuna sea la causa. Las vacunas COVID-19 son seguras y efectivas para protegerlo de enfermedades graves y la muerte. Más de 95 de cada 100 personas hospitalizadas con COVID-19 y 99 de cada 100 personas que murieron por COVID-19 no estaban vacunadas. Si no se ha vacunado, consulte https://www.vaccines.gov/ para encontrar una vacuna COVID-19 cerca de usted y vacúnese lo antes posible. |

| Vaccine safety for kids | To increase knowledge and awareness; form positive attitudes and beliefs | Authority | Vaccines must go through careful research to make sure they are safe and effective at saving lives and preventing infection. Most vaccines are studied in adults first, then in children. Pfizer's clinical trials among 2260 ages 12–15 showed that the vaccine is safe and effective for kids. Another trial among children between 5–11 years old also shows that the vaccine is safe and can help children develop a strong antibody response against the virus. The FDA has authorized the emergency use of both Pfizer/BioNTech's and Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine for children 6 months through 17 years. If your kids are 6 months old or older, you can get them vaccinated against COVID-19 now. If your kid has a history of an allergic reaction, you should consult their pediatrician before vaccinating. | Las vacunas deben someterse a una cuidadosa investigación para garantizar que sean seguras y eficaces para salvar vidas y prevenir infecciones. La mayoría de las vacunas se estudian primero en adultos y luego en niños. Los ensayos clínicos de Pfizer entre 2260 personas de 12 a 15 años mostraron que la vacuna es segura y eficaz para los niños. Otro ensayo entre niños de 5 a 11 años también muestra que la vacuna es segura y puede ayudar a los niños a desarrollar una fuerte respuesta de anticuerpos contra el virus. La FDA ha autorizado el uso de emergencia de la vacuna COVID-19 de Pfizer/BioNTech y Moderna para niños de 6 meses a 17 años. Si sus hijos tienen 6 meses o más, puede vacunarlos contra el COVID-19 ahora. Si su hijo tiene antecedentes de reacción alérgica, debe consultar a su pediatra antes de vacunarlo. |

| Vaccine and women's health | To increase knowledge and awareness; correct misbeliefs | Protecting loved ones | The COVID-19 vaccine is safe for women who are pregnant, breastfeeding, and planning to become pregnant. People who menstruate can receive the COVID-19 vaccine or the booster at any point in their menstrual cycle. Evidence from a study of 4000 women shows that COVID vaccines have a very minimal and temporary impact on menstruation. For more information, check here. Getting the COVID-19 vaccine will not cause infertility or impact your reproductive organs. There is no evidence that the vaccine will cause miscarriage. Another myth is out there that vaccines cause infertility or impact puberty. This is also not true. It is totally understandable that people have questions and concerns about vaccines. What we know is no myth is that the benefits to you, your family, and your community from the vaccines are very real! | La vacuna COVID-19 es segura para las mujeres que están embarazadas, amamantando y planeando quedar embarazadas. Las personas que menstrúan pueden recibir la vacuna COVID-19 o el refuerzo en cualquier momento de su ciclo menstrual. La evidencia de un estudio de 4000 mujeres muestra que las vacunas COVID tienen un impacto mínimo y temporal en la menstruación. Para obtener más información, consulte aquí. Recibir la vacuna COVID-19 no causará infertilidad ni afectará sus órganos reproductivos. No hay evidencia de que la vacuna provoque un aborto espontáneo. Otro mito es que las vacunas causan infertilidad o afectan la pubertad. Esto tampoco es cierto. Es totalmente comprensible que las personas tengan preguntas e inquietudes sobre las vacunas. ¡Lo que sabemos no es un mito, es que los beneficios para usted, su familia y la comunidad de las vacunas son muy reales! |

| Vaccines and DNA and tracking | To increase knowledge and awareness; correct misbeliefs | Commitment | Receiving an mRNA or viral vector vaccine will not affect your DNA in any way. COVID-19 vaccines work with our natural defense system to safely develop immunity to COVID-19. Once you get a vaccine, you will have a card that documents you have had it, and your provider may also put that information in your medical record. There is no other tracking of people with a vaccine, so keep your vaccine card to prove you are protected from COVID-19! | Al recibir una vacuna mRNA o vector viral no hará que su DNA se afecte de ninguna manera. Las vacunas del COVID-19 trabajan con nuestro sistema de defensas para que de manera segura desarrolles inmunidad contra el COVID-19. Una vez que tenga la vacuna, tendrá una tarjeta que documentara la vacuna que tiene, y su proveedor de salud tal vez ponga esa información en su historial medico. No hay otra forma de realizar seguimiento a las personas con la vacuna, así que mantén la tarjeta de vacunación para comprobar de que su esta protegido del COVID-19. |

| Vaccine effectiveness | To increase knowledge and awareness; form positive attitudes and beliefs | Protecting loved ones | We know that COVID-19 vaccines are safe and will protect most people from the COVID-19 virus, including the Delta variant. Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson vaccines work equally well across different ages, racial groups, ethnicities, and genders. Getting a vaccine is the best tool you can use to protect yourself and your loved ones and help stop the pandemic! | Sabemos que las vacunas COVID-19 son seguras y protegerán a la mayoría de las personas del virus COVID-19, incluida la variante Delta. Las vacunas Pfizer, Moderna y Johnson & Johnson funcionan igual de bien en diferentes edades, grupos raciales, etnias y géneros. ¡Vacunarse es la mejor herramienta que puede usar para protegerse a sí mismo y a sus seres queridos y ayudar a detener la pandemia! |

Tracking metrics and protocol for updates

Throughout the deployment of the chatbot, we closely monitored logs that documented each question posed to the system and each response sent by the system as well as the time of day and date for each interaction. We also identified (a) system errors (e.g. failing to react) and (b) inaccurate matching between user queries and responses, which included providing a wrong direct answer or a picklist without the user's intent, or not being able to categorize the question into existing intents. The mismatched queries were reviewed and reclassified manually to improve the ML model and reassign the specific language of a mismatched query to the appropriate intent. If there was no existing intent to match a query, and the query was related to COVID-19 vaccines, we would create new intents, develop theory-informed responses, and generate at least 18 variations on queries using the MTurk crowdsourcing process described above. We generated weekly reports on the number of messages by type (text or web), message timing, and message content for our clinic partners.

Besides ongoing monitoring of the system performance, it was also crucial to continuously update the response message library to keep consistent with the rapidly changing situation, the most current evidence, and vaccine policies and regulations. For example, when vaccine eligibility criteria changed to include children aged 5–11 years, we reviewed the library to make sure that references to those under 12 are correct. All versions of the webbot and textbot files in both English and Spanish were archived on a shared drive. Key changes were summarized in a tracking document.

Data collection and analysis

To evaluate the feasibility of the COVID-19 vaccine chatbot, we collected data regarding the following dimensions: usage, accuracy, reaction time, and user satisfaction. Usage was reflected by the total number of users, the total number of questions posted to the chatbot, and the average number of questions asked for each user. Accuracy refers to the percentage of chatbot responses that correctly answered users’ questions either by providing a direct response or a picklist containing the appropriate intent of the question. Reaction time indicated whether users could get timely feedback from the chatbot. We measured the duration between when a user's input hit the server and when a response left the server. User satisfaction was measured by asking users how satisfied they were with the chatbot on a scale of five through a survey question when they closed the webbot window or when the conversation was inactive for more than 5 min. However, since we did not receive sufficient feedback on satisfaction, we were not able to report on this dimension. Informed consent for participation in the study was waived as all users interacted with the chatbot anonymously and no identifiable information was collected. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved this study (protocol # 20-2014).

Results

Over the course of this feasibility study, we continually updated message content in response to new COVID-19 vaccine guidance, resulting in 55 versions of the textbot and 33 versions of the webbot as the webbot was developed and implemented three months later than the textbot. We added 20 new intents and corresponding responses to the message library. Five initial intents were merged with other existing intents to improve the efficiency of the chatbot if they met one of the following criteria: (1) very few users inquired about this intent; (2) questions generated to ask about this intent were largely overlapped with another intent; (3) the response to this intent was similar to the response to another intent, making it redundant as a separate intent.

Reach and usage

The COVID-19 vaccine promotion chatbot was first launched on 19 April 2021. Between then and 22 March 2022, a total of 2479 users interacted with the chatbot, generating a total number of 3994 unique questions. Figure 3 illustrates the cumulative number of queries and users over time. Each user posted an average of 1.8 questions (SD = 1.8; Median = 5; Mode = 2), ranging from 1 to 38 questions (Q1 = 1; Q3 = 8). Among the users, 2254 interacted with the chatbot over the websites, and 225 over short message services. Most of the interactions were in English (91.1%).

Figure 3.

Cumulative weekly queries and users.

Frequently asked questions

The most asked topic was related to “boosters,” which was asked 648 times. This was followed by “where to get the vaccine” (601 times), then “COVID-19 symptoms, testing, and reporting” (464 times). Figure 4 summarized the top 10 most frequently asked questions for the chatbot. There were also circumstances when users asked irrelevant questions and the chatbot could not provide an answer. Table 2 summarizes the types of failed or irrelevant conversations.

Figure 4.

Top 10 frequently asked intents.

Table 2.

Examples of failed or irrelevant conversations.

| Types | Raw count | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Unrelated topics | 513 | “birth certificate”; “scholarships”; “cook job.” |

| Not a question | 102 | “I have been vaccinated”; “My daughter received her shot on Thursday.” |

| Uncivil or sarcastic expressions | 52 | “when can I buy a burn permit?” |

| Social conversations | 23 | “Hi!” “Are you a robot? Answer my question please.” “I doubt your a real person. I think your some. Not that is pretty much useless.” “Alexa actually answers my questions.” |

| Political concerns | 21 | “Why is the Biden administration so insistent on pushing an experimental vaccine? I have been taking vaccines since before I can remember. I am definitely NOT against vaccines! Why did Kamala discourage everyone from getting the vaccine? She has made me afraid!” “If it's so secure and safe why did the Government sign an executive order to protect vaccine manufacturers from lawsuits that result from side effects and complications from the covid vaccine??” |

| Appreciation | 8 | “I am looking for a new primary care physician and I have Medicaid. Sorry I just realized that (you are a covid-19 vaccine chatbot) thank you.” “I want to thank Dr XX for treating me after a car accident.” |

| Religious expressions | 1 | “Stop spreading lies, crazy commies. Why do you insist on feeding lies. There is no science behind your lies. Stop. Jesus is coming. It's not too late to turn to Him.” |

Accuracy

Whether a chatbot can provide an appropriate answer to users’ specific questions is key to the chatbot's performance. The accuracy rate of the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy chatbot fluctuated over time. The average accuracy rate of non-numerical, non-greeting interactions1 was 74.8%. In the first week of launching the chatbot, the chatbot had a relatively low accuracy rate of 54.0%. At the end of the study period, the accuracy rate achieved a high level of 91.1%.

Response time

Quick feedback on users’ queries is one of the most important criteria for evaluating the performance of digital health tools. Although the speed of return largely depends on factors on the receivers’ end, such as the internet speed and computer processing speed, we can still calculate the average reaction time on the system's side. The medium of the waiting time was 0.199 s (mode = 0.099 s), guaranteeing that users with adequate equipment can receive timely responses.

Discussion

The COVID-19 vaccine chatbot functioned well in delivering credible, novel, and persuasive information at scale, correcting misinformation, addressing health concerns, providing personalized health resources, and triaging people to needed health services. This chatbot system demonstrated the feasibility and easy implementation into partner health systems’ websites. People engaged more with the webbot compared to the textbot, probably because the webbot was easier to access, had better visualization, and induced higher trust as it was embedded on their clinic's website. The accuracy of matching users’ questions with the appropriate answers was acceptable and increased over time, demonstrating the chatbot's ability to quickly increase accuracy when new topics/questions emerged. One advantage of our chatbot is that it focuses on high-risk populations for COVID-19 and delivers culturally appropriate messages for ethnic minorities. The chatbot is available in both English and Spanish. Compared to the generic solution offered by most chatbot services, our chatbot provides targeted responses to address people's specific questions.

The current chatbot system also has some limitations. First, we do not have well-established science for COVID-19. Since COVID-19 is an evolving health crisis, our responses need to be based on emerging evidence, which requires constant and timely updates of the response content and question pool; otherwise, the accuracy rate will plummet. Second, AI or ML usually requires a large volume of data to learn and achieve high accuracy. We used thousands of questions to reach an accuracy rate of 90%. More data and time may be needed to further increase accuracy.

This proof-of-concept pilot study contributes to understanding whether this system-level effort is feasible and impactful. Furthermore, our efforts allow healthcare delivery systems to consider strategies to deploy AI chatbot services in response to other emergent issues, for example, annual flu vaccination campaigns or different epidemics. It can also be adapted for screenings and medical care that require annual or episodic visits and detailed instructions. The next steps include adapting the current message library to fit the COVID-19 contexts in Canada and developing a chatbot targeting health providers to facilitate their COVID-19-related healthcare delivery. We also plan to conduct an efficacy test of this chatbot, which will require setting up restrictions to access and randomization or using a quasi-experimental design to evaluate patients’ vaccination rates among our five partners implemented the COVID-19 vaccine chatbot and other comparable healthcare delivery systems without the chatbot. It is worth further research on systematically reviewing the usability and efficacy of existing chatbots or other AI-based tools for COVID-19 prevention and vaccination promotion.

Conclusion

It is feasible and potentially useful to create chatbot systems using AI to facilitate access to complete and persuasive information on infectious diseases. Such a system can be adapted to use with patients and populations needing detailed information and motivation to act in support of their health.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Tepayac Community Health Center, Salud Family Health Center, Valley-Wide Health Systems, Clinica Colorado, and STRIDE Community Health Center for their support and efforts in implementing the chatbot in their health systems.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Intents for the COVID-19 vaccine chatbot

| Number | Intent |

|---|---|

| 1 | How to register for vaccines (including registration, appointment, where to vaccinate, where do I go for an appointment, where can I get a vaccine) |

| 2 | Activity after vaccination |

| 3 | Cost of the vaccine |

| 4 | COVID transmission |

| 5 | COVID-19 prevention after vaccination |

| 6 | COVID-19 quarantine and isolation rules |

| 7 | COVID-19 prevention |

| 8 | COVID-19 symptoms, testing, home testing & reporting |

| 9 | Difference between vaccines (merged with “Vaccine choices”) |

| 10 | Eligibility for vaccine (merged with “The timeline to distribute vaccines to everyone”) |

| 11 | Ethnic minorities and COVID vaccination |

| 12 | Fairness of the process to distribute vaccines |

| 13 | Getting and Giving COVID post vaccine |

| 14 | Getting COVID from the vaccine |

| 15 | Getting the vaccine while having COVID (or sick) |

| 16 | How COVID vaccines work |

| 17 | How long does the vaccine effect last? (merged with “How often to vaccinate”) |

| 18 | Intro to chatbot I (Language) |

| 19 | Intro to chatbot II (Welcome) |

| 20 | Is the vaccine mandatory? |

| 21 | Side effects |

| 22 | Total number of people vaccinated to date |

| 23 | Vaccine distribution |

| 24 | Vaccine effectiveness |

| 25 | Vaccine effectiveness after COVID infection |

| 26 | Vaccine ingredients |

| 27 | Vaccine process |

| 28 | Vaccine research |

| 29 | Vaccine safety |

| 30 | Vaccine Scams |

| 31 | Vaccine trustworthiness |

| 32 | Vaccines and COVID-19 variants |

| 33 | Vaccines and DNA and tracking |

| 34 | Vaccines fetal tissue |

| 35 | Vaccines for children (merged with “When can children get vaccinated?”) |

| 36 | Vaccine and women's health (merged with “Vaccines miscarriage infertility”) |

| 37 | Vulnerable groups and vaccinations |

| 38 | What is herd immunity |

| 39 | What you need to know about getting vaccinated |

| 40 | When protected from COVID |

| 41 | Who should and should not vaccinate |

| 42 | Why vaccinate |

| 43 | Vaccine documentation |

| 44 | Evaluation message I |

| 45 | Evaluation message II |

| 46 | Why the 2nd dose is important? |

| 47 | Vaccine safety for kids |

| 48 | Vaccine side effects for kids |

| 49 | How to get kids vaccinated |

| 50 | Why get my kids vaccinated (target: parents) |

| 51 | Why does it matter to me to get vaccinated? (target: kids 12–18) |

| 52 | Timing for teenagers |

| 53 | Are vaccines different for children? |

| 54 | Vaccine availability for children |

| 55 | Time between two shots |

| 56 | J&J concerns |

| 57 | Speak to a live person |

| 58 | Death from COVID or vaccines |

| 59 | Delta variant |

| 60 | Full approval of COVID-19 vaccines |

| 61 | Booster |

| 62 | School policy for testing and prevention |

| 63 | Omicron variant |

| 64 | Treatment |

| 65 | Mask |

| 66 | Travel |

Numerical interactions take place when a user picks their intents from a picklist or selects their preferred language. We removed these questions when calculating the accuracy of our models as responses to these questions are rule-based and their accuracy is always 100%. Greetings refer to when a user says “hi” or “hello” to the chatbot. Social conversation was not a part of the interaction and was not the purpose of this chatbot. Therefore, we also removed greetings from accuracy analysis. Other types of failed or irrelevant interactions were summarized and demonstrated in Table 2.

Footnotes

Contributorship: SZ and SB researched literature and conceived the study. SZ and SB were involved in protocol development and gaining ethical approval. JS and AS designed and implemented the chatbot. SZ, SB, and CChavez developed and updated chatbot messages. CClark monitored the performance of the chatbot and conducted data analysis. SZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved this study (protocol # 20-2014).

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Colorado Office of Economic Development and International Trade (grant nos. 1UH3 HL144163, NIH UH3 AT009845, CTGG1-2021-3435).

Guarantor: SZ.

ORCID iD: Shuo Zhou https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7514-3522

References

- 1.The New York Times. Coronavirus in the U.S.: Latest map and case count, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/us/covid-cases.html (2022, accessed 10 April 2022).

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker, https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations_vacc-people-onedose-pop-5yr (2022, accessed 11 April 2022).

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimates of vaccine hesitancy for COVID-19, https://data.cdc.gov/stories/s/Vaccine-Hesitancy-for-COVID-19/cnd2-a6zw/ (2022, accessed 11 April 2022).

- 4.Kaiser Family Foundation. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: February 2022, https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-february-2022/ (2022, accessed 12 April 2022).

- 5.Troiano G, Nardi A. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19. Public Health 2021; 194: 245–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Schulz WS, et al. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: the development of a survey tool. Vaccine 2015; 33: 4165–4175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaiser Family Foundation. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: Media and Misinformation, https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-media-and-misinformation/ (2022, accessed 12 April 2022).

- 8.Kaiser Family Foundation. Nearly Eight In Ten Believe Or Are Unsure About At Least One Common Falsehood About COVID-19 Or The Vaccine, https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/dashboard/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-dashboard/#(mis)information (2021, accessed 12 April 2022).

- 9.Wiysonge CS, Ndwandwe D, Ryan J, et al. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19: could lessons from the past help in divining the future? Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022; 18: 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeRoo SS, Pudalov NJ, Fu LY. Planning for a COVID-19 vaccination program. JAMA 2020; 323: 2458–2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willems SH, Rao J, Bhambere S, et al. Digital solutions to alleviate the burden on health systems during a public health care crisis: COVID-19 as an opportunity. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021; 9: e25021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikolovski J, Koldijk M, Weverling GJ, et al. Factors indicating intention to vaccinate with a COVID-19 vaccine among older US adults. PLoS One 2021; 16: e0251963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pothiawala S. COVID-19 and its danger of distraction. Qatar Med J 2020; 2020: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nembhard IM, Burns LR, Shortell SM. Responding to COVID-19: lessons from management research. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv 2020; 1: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avila-Tomas JF, Olano-Espinosa E, Minué-Lorenzo C, et al. Effectiveness of a chat-bot for the adult population to quit smoking: protocol of a pragmatic clinical trial in primary care (Dejal@). BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2019; 19: 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oh K-J, Lee D, Ko Bet al. et al. Empathy bot: conversational service for psychiatric counseling with chat assistant. Stud Health Technol Inform 2017; 245: 1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayanouz S, Abdelhakim BA, Benhmed M. A smart chatbot architecture based NLP and machine learning for health care assistance. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Networking, Information Systems & Security 2020, pp.1-6.

- 18.Adamopoulou E, Moussiades L. An overview of chatbot technology. In: IFIP International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations 2020, pp.373-383. Springer.

- 19.Mierzwa S, Souidi S, Conroy T, et al. On the potential, feasibility, and effectiveness of chat bots in public health research going forward. Online J Public Health Inform 2019; 11: e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palanica A, Flaschner P, Thommandram Aet al. et al. Fossat YPhysicians' perceptions of chatbots in health care: cross-sectional web-based Survey. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21: e12887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Oh YJ, Lange Pet al. et al. Artificial intelligence chatbot behavior change model for designing artificial intelligence chatbots to promote physical activity and a healthy diet: viewpoint. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e22845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nadarzynski T, Miles O, Cowie A, et al. Acceptability of artificial intelligence (AI)-led chatbot services in healthcare: a mixed-methods study. Digit Health 2019; 5: 2055207619871808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin A, Nateqi J, Gruarin S, et al. An artificial intelligence-based first-line defence against COVID-19: digitally screening citizens for risks via a chatbot. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gentner T, Neitzel T, Schulze J, et al. A Systematic literature review of medical chatbot research from a behavior change perspective. In: 2020 IEEE 44th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC) 2020, pp.735-740. IEEE.

- 25.Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Demographics of Mobile Device Ownership and Adoption in the United States, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/ (2021, accessed April 2, 2021).

- 26.Rhoades H, Wenzel SL, Rice Eet al. et al. No digital divide? Technology use among homeless adults. J Soc Distress Homeless 2017; 26: 73–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lenhart A. Cell phones and American adults. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2010/09/02/cell-phones-and-american-adults/ (2010, accessed April 2, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Posadzki P, Mastellos N, Ryan R, et al. Automated telephone communication systems for preventive healthcare and management of long-term conditions. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev December 2016; 12: CD009921. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009921.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choudhry NK, Krumme AA, Ercole PM, et al. Effect of reminder devices on medication adherence: the REMIND randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Denver Channel. Fauci expects more waves of COVID-19 outbreaks, but says US will be better prepared to handle them, https://www.thedenverchannel.com/news/national/coronavirus/fauciexpects-more-waves-of-covid-19-outbreaks-but-says-us-will-be-better-prepared-to-handle-them (2020, accessed 19 November 2020).

- 31.Snyder LB, Hamilton MA, Mitchell EW, et al. A meta-analysis of the effect of mediated health communication campaigns on behavior change in the United States. J Health Commun 2004; 9: 71–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chatbot and Infermedica. COVID-19 Risk Assessment Chatbot, https://www.chatbot.com/covid19-chatbot/ (2022, accessed 5 November 2022).

- 33.Translators without Borders. Chatbots against COVID-19: Using chatbots to answer questions on COVID-19 in the user’s language, https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/science-translation/case-studies-1/cs7_chatbots.pdf?sfvrsn=4fa08841_4 (2020, accessed 5 November 2022).

- 34.Smith B, Magnani JW. New technologies, new disparities: the intersection of electronic health and digital health literacy. Int J Cardiol 2019; 292: 280–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amazon Mechanical Turk. https://www.mturk.com/ (accessed 10 April 2022).

- 36.Mortensen K, Hughes TL. Comparing Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform to conventional data collection methods in the health and medical research literature. J Gen Intern Med 2018; 33: 533–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bull S, Ezeanochie N. From Foucault to Freire through Facebook: toward an integrated theory of mHealth. Health Educ Behav 2016; 43: 399–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cialdini RB. Influence: The psychology of persuasion. Rev. ed. New York: Morrow, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gantiva C, Jiménez-Leal W, Urriago-Rayo J. Framing messages to deal with the COVID-19 crisis: the role of loss/gain frames and content. Front Psychol 2021; 12: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rutten LJF, Zhu X, Leppin AL, et al. Evidence-based strategies for clinical organizations to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Mayo Clin Proc 2021; 96: 699–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rothman AJ, Bartels RD, Wlaschin J, et al. The strategic use of gain-and loss-framed messages to promote healthy behavior: how theory can inform practice. J Commun 2006; 56: S202–S220. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fishbein M, Yzer MC. Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Commun Theor 2003; 13: 164–183. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol 2001; 52: 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol Health 1998 Jul; 13: 623–649. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou S, Villalobos JP, Munoz Aet al. et al. Ethnic minorities’ perceptions of COVID-19 vaccines and challenges in the pandemic: a qualitative study to inform COVID-19 prevention interventions. Health Commun 2022 Oct 15; 37: 1476–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]