Abstract

Objective

Addressing gaps in COVID-19 vaccine-hesitancy research, the current study aimed to add depth and nuance to the exploratory research examining vaccine-hesitant groups. Using a larger, but more focused conversation occurring on social media, the results can be used by health communicators to frame emotionally resonant messaging to improve COVID-19 vaccine advocacy while also mitigating negative concerns for vaccine-hesitant individuals.

Methods

Social media mentions were collected using a social media listening software, Brandwatch, to examine topics and sentiments in COVID-19 hesitancy discourse during a period of September 1, 2020, through December 31, 2020. The results from this query included publicly available mentions on two popular social media sites, Twitter and Reddit. The dataset of 14,901 global, English language messages were analyzed using a computer-assisted process in SAS text-mining and Brandwatch software. The data revealed eight unique topics before being analyzed by sentiment.

Results

Among the COVID-19 hesitancy data, trust-related topics emerged that included declining vaccine acceptance, a parallel pandemic of distrust, and a call for politicians to let the scientific process work, among others. Positive sentiment revealed interest in the sources which included healthcare professionals, doctors, and government organizations. Pfizer was found to elicit both positive and negative emotions in the vaccine-hesitancy data. The negative sentiment tended to dominate the hesitancy conversation, accelerating once vaccines hit the market.

Conclusions

Relevant topics were identified to help support targeted communication, strategically accelerate vaccine acceptance, and mitigate COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the public. Strategic methods of online and offline messaging tactics are suggested to reach diverse, malleable populations of interest. Topics of personal anecdotes of safety, effectiveness, and recommendations among families are identified as persuasive communication opportunities.

Keywords: COVID-19, vaccine hesitancy, Pfizer, health communication, social media

Introduction

As COVID-19 continues to spread, public health experts state that inoculations are imperative to help end the pandemic. Meanwhile, many people remain hesitant or opposed to receiving the COVID-19 vaccine,1 with about one-tenth of unvaccinated U.S. adults saying that they “probably will not” or “definitely will not” get a vaccine.2 Among those who are unsure, distrust, and uncertainty play a large role.3 Between a lack of trust and knowledge about the vaccine, some hesitancy can be expected.4 However, despite the perceived reasons for not getting a vaccine, research is also growing which shows that COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is malleable.5 This indicates that among hesitant groups, some people may be more easily persuaded. The heterogeneity of these groups further suggests the need to address vaccine concerns strategically. Positive and negative emotions may be one way to frame emotionally resonant messaging to either complement communication opportunities or on the other hand, combat manipulation efforts by anti-vaxxers.6

Calls for more research to address the scope of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy1 include priorities for digital health communication strategies and digital education, which are considered key to much-needed industry innovation.7 In particular, emotional appeals can be used in health communication to drive behavior change.6,8,9 In order to mitigate hesitancy, it is useful to not only understand the type of information that is being shared but also to examine people's underlying opinions to improve vaccine uptake among the public. Building upon previous research, the current study extends the use of social media discourse to provide communication guidance to public health officials and understand frames of community concern regarding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.

COVID-19-related research

The World Health Organization has identified vaccine hesitancy as one of the biggest threats to global health.10 Previous social media analyses regarding COVID-19 have investigated the evolution of public priorities,11 health disparities,12 and general reactions, concerns, and sentiments toward COVID-19.12,13 Other studies have looked broadly at vaccine hesitancy, remaining focused on specific social media platforms and countries,14 or on short time periods before the vaccines were being rolled out to the general population.15 For instance, one related study relied on Twitter discourse to understand COVID-19 topics in Canada. In their analysis, Griffith et al. collected an initial sample of 3915 tweets using the search query “vaccine” AND “COVID” and then used content analysis to identify the final, relevant sample of 605 tweets.14 The researchers selected the time period between December 10 and 23, 2020, following the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine approval in Canada. Topics of mistrust identified concerns for safety, politics, and economics, a lack of knowledge, confusion in messaging or antivaccine messages from authoritative figures, and a lack of legal liability on behalf of the vaccine companies.

Interprofessional sources, such as healthcare practitioners and office staff, can be useful for knowledge sharing with one another.16 Thus, identifying similar trusted sources online can be useful, as these sources may have the power to influence other individuals whom they work alongside and are still unsure about the vaccines. With the aim of guiding strategic messaging for health providers, we are particularly interested in the attributes in online conversations related to trust, mistrust, and trusted sources, which are unique from previous studies. Thus, when exploring the underlying topics of interest among the online rhetoric regarding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, special interest is given to topics that provide insight into trust and trusted sources regarding vaccine hesitancy. Hence, for public health experts to appropriately communicate in a manner that may mitigate vaccine hesitancy, understanding topics, trusted sources, and opinions can yield insights to be employed in message-framing strategies.

The present study aims to address several outstanding research gaps from similar studies14,15 while adding a unique perspective due to the time period of data collection. First, the study addresses the limited information from Griffith et al.14 on mistrust and authoritative figures as sources of information. The present study further explores the area of trust, mistrust, and distrust surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine, as well as identifying specific trusted sources for information about the vaccine. Second, the present study includes a larger dataset than previous studies and it captures posts over a longer period of time (4 months, compared to Griffith et al.'s 2 months and Hou et al.'s 2 weeks). As such, the present study addresses these research gaps and raises the following questions:

RQ1: What general topics will arise in the COVID-19 vaccine-hesitancy conversation?

RQ2: What related topics of trust, mistrust, or distrust will be identified in the COVID-19 vaccine-hesitancy conversation?

RQ3: Who, if any, are the trusted sources mentioned within the topics?

Emotion as a frame

Framing theory suggests that message presentation, called “the frame,” can affect how an audience accepts the message, conceptualizes an issue, or reorients to a topic.17 Message framing has been used before to promote vaccine acceptance18 and perceived effectiveness.19 Public health interventions, too, can benefit by being grounded in framing, providing usefulness in the application of interpreting public discourse related to vaccine hesitancy.

Moreover, framing theory shows that how an issue is presented will influence how it is perceived which in turn affects how opinions are shaped. In the framing literature, message-induced emotion can act as a frame for how people perceive an incoming message, mediating the effects of the message on persuasion outcomes.8,20 Indeed, research continues to grow to show that frames shape opinions.20–22

Positive and negative emotion

When emotion is framed within a message, it may arouse feelings of positive or negative sentiment. Because positive affect has been associated with feelings of freedom, safety, and ease,23 the frames associated with positive affect may be useful in guiding health communication language to improve feelings24 about the COVID-19 vaccine while also useful in mitigating COVID-19 hesitancy. On the other hand, negative emotions are pervasive in vaccine hesitancy and must be acknowledged alongside specific predispositions of intended audiences.6 Contributing to the heightened negative emotion surrounding vaccines is the usage of emotional manipulation to promote negative views by antivaccination groups.25,26 One strategy for dealing with uncertain and uncontrollable situations is to focus on negative emotion reduction as opposed to changing behaviors.27 Framing a concrete actionable strategy for COVID-19 risk reduction could lead to increased feelings of self-efficacy.6,28

As one of the more common approaches for measuring emotion in text, sentiment analyses measure text on a scale of emotion as either positive or negative and is expressed with measures of associated sentiment scores.29 Sentiment analysis can be helpful in recognizing the emotional tone behind a sequence of words,30 both positive and negative. Therefore, while COVID-19 social media analyses have examined overall sentiment and were able to identify which social media mentions had positive or negative sentiment,12,13,31 few studies have examined COVID-19 hesitancy topics using an affective computing method to measure sentiment.

Sharing behavior

Frames of emotion have been found to affect desired attitudes and advocacy,32 which can lead to an uptick in word of mouth (WOM), as well as additional positive sentiment being shared online. During the COVID-19 pandemic, people have used social media to share information, news, stories, and reactions toward COVID-19. Research shows sharing stories online can be cathartic during a crisis33 and that emotional valence can influence the online virality (e.g. sharing) of information like news articles. For instance, news article-sharing behavior that is associated with sad content leads to less sharing behavior compared to news articles containing positive emotions.34 Sharing can also represent brand loyalty, suggesting that consumers who advocate on behalf of a brand are more valuable. When consumers feel connected with a brand, those feelings can be used to improve loyalty or even drive increases in the information that is shared with a brand.35 Additionally, a consumer's perceived brand attachment also suggests their future behavior and purchase intention36 with every interaction acting as an opportunity to build upon this momentum. Because people share their thoughts and stories online, understanding public conversations can enable public health experts to tailor their strategies and interventions.13 Thus, the sentiment and underlying emotion of topics can lead to powerful effects on the fight against COVID-19.

Moreover, gaps persist surrounding the nuance in vaccine hesitancy, particularly related to the use of affective computing. Previous COVID-19 social media analyses using sentiment analysis12,13,31 did not explore the COVID-19 vaccine or vaccine hesitancy, nor did they utilize affective computing to determine sentiment. This nuance can be explored using COVID-19 vaccine-hesitancy conversation data to mine for topics and sentiment. Additionally, the present study uniquely captures the time period both before the vaccine was available to the public (September–November 2020) and the first month of the vaccine's availability to the public (December 2020). This allows the data to be analyzed over time, thus showing how frames (positive and negative) may have changed as the vaccine became available. Taken together, sentiment and hesitancy toward the COVID-19 vaccine are measured over time and by topic with the goal of answering the following proposed research questions:

RQ4: How have frames changed (e.g. more positive or negative) since the vaccine has become available?

RQ5: How are topics framed (positive or negative) in the COVID-19 vaccine-hesitancy discourse?

Methods

Data acquisition

In the present study, the research questions were explored through a social media text analytic process used to identify topics in the COVID-19 vaccine-hesitancy discourse on social media. The text analytic process involves first capturing the mentions, then using the corpus of mentions, or dataset, to mine for topics. To guide public health communication and strategy, topics are identified as they emerge from the data before determining how they relate to the research goals. Thus, a text analytic process was used to identify topics and extract meanings contained in unstructured textual data. Social media mentions were collected using Brandwatch software.37 Brandwatch provides full “firehose” data access to the Twitter and Reddit social media application programming interface (API).38 As an analytic tool, Brandwatch mitigates many of the issues associated with low-quality text mining by removing duplicates, spam, and promotional content. For sentiment analysis, a three-step hybrid approach was used to maximize accuracy. The three-step process includes a combination of manual and automated natural language processing (NLP) using knowledge-based, machine learning, and rule-based methods to measure sentiment.39

Because our focus was on conversations surrounding COVID-19 and the vaccines, our analysis uses Boolean queries consisting of simple terms to form a Boolean expression based on social media mentions of the COVID-19 vaccines and language relating to hesitancy including the truncated terms of hesitate, hesitant, and reluctant (see Appendix for Boolean code). The aim of these queries is to mitigate erroneous noise in the data while also capturing relevant discourse that may illuminate new findings regarding vaccine-hesitant individuals. Our process is designed to be comprehensive while also being specific in the terms used in the query. Therefore, mentions like, “I do not want to vaccinate because,” were purposefully excluded because those conversations may instead represent an individual whose opinions toward vaccines are not malleable. On the other hand, the current study's query is searching to identify hesitant individuals with specific language (e.g. reluctant or hesitant) suggesting that they are hesitant, and therefore persuadable because they are not completely against receiving a vaccination.

Social media mentions were captured during a period of September 1 through December 31, 2020, and included 14,901 global, English language messages from publicly available sources. These dates were selected to provide a holistic dataset including vaccine-hesitancy discourse before and after the availability of the first COVID-19 vaccines occurred in the United States on December 10, 2020,40 with mass vaccinations beginning 4 days after.

As the biggest source for social media data, approximately 10,579 out of 14,901 messages (71%) were sourced from Twitter followed by approximately 2980 out of 14,901 messages (20%) sourced from news websites. The other three sources included Reddit, forums, and blogs which accounted for less than 894 mentions or about 6% of the remaining source volume.

As tracked by the online location meta-data, approximately 9427 out of 14,901 of the mentions (63%) originated in the United States, 1799 out of 14,901 of the mentions (12%) originated in the United Kingdom, 1371 out of 14,901 of the mentions (8%) originated in Canada, 642 out of 14,901 of the mentions (4%) originated in India, 415 out of 14,901 of the mentions (2%) originated in Australia, 238 out of 14,901 of the mentions (1%) originated in the Republic of Ireland, 68 or fewer out of 8472 of the mentions (<1%) originated in all other global locations.

Naturally, collecting and working with unstructured data requires data cleaning as an important step in social media analytics and is discussed in further detail in the following paragraphs. To understand conversations taking place on the COVID vaccine topic, duplicate (shares and retweets) and robotic (bots) messages were removed prior to the text analysis. A Python script written to remove duplicate and robotic messages was used and resulted in a total of 5740 individual mentions for the final dataset. Doing so allowed the researchers to extract messages that may tend to amplify certain viewpoints or distort public conversations. Mentions were then analyzed using text-mining software, SAS Text Miner 15.1.41 SAS employs a series of algorithms that select words that are used together frequently to build the topic groups that help to identify underlying themes in the data. In this instance, the program identified eight topic groups (described in Table 1).

Table 1.

Hesitancy data by topic.

| ID | Topic description | Topic | Number of mentions | Exemplary message |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Declining acceptance | +country, acceptance, +study, vaccine acceptance, +decline | 146 | Johns Hopkins study finds declining acceptance rate, describing a pandemic of distrust |

| 2 | Parallel pandemic of distrust | pandemic, defeat, parallel pandemic, parallel, societies | 125 | The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies said that to beat the pandemic, we also must defeat the parallel pandemic of distrust, a growing hesitancy about vaccines in general and about a COVID vaccine |

| 3 | Let science work | +politician, +doctor, back, primary care, primary | 86 | Dr William Schaffner, vaccine specialist at Vanderbilt University says even primary care physicians have questions, politicians should let the scientific process work |

| 4 | Racial disparities | +american, white, +compare, ap-norc poll, ap-norc | 74 | AP-NORC poll finds that while Black Americans have been especially hard-hit by COVID-19, just 22% say they plan to get vaccinated compared with 48% of white Americans |

| 5 | Need for global communities of trust | rocca, vaccinating people, importance, francesco, critical importance | 68 | Mr Rocca, the International Federation of Red Cross president, says leaders need to start building trust in communities globally about the importance of vaccinating people |

| 6 | Myth busting | +read, b.c., +reason, health, +break | 67 | BC expert breaks down COVID-19 vaccine myths, approved by Health Canada, and Northern Health said the vaccines are safe |

| 7 | Russian interference | jha, russian vaccine, russian,+end,working | 27 | Concern about mixed signals if the Russian vaccine ends up not working |

| 8 | Hesitancy is normal | omenka, ogbonnaya, +accompany, infectious, infectious disease | 23 | Ogbonnaya Omenka, an associate professor and public health specialist at Butler University says vaccine hesitancy is normal when a country tries to contain an infectious disease |

Note. The ‘+’ symbol represents the inclusion of alternative forms of the word similar to the wildcard character in Boolean language such as plurals or active or past tense, etc.

Text analytics

SAS Text Miner provides the ability to parse and extract information from text, filter and store the information, and assemble tweets into related topics for introspection and insights from the unstructured data.41 After the unstructured data was cleaned using the Python script, the initial step in Text Miner was to extract and create a dictionary of words using NLP. Using the Text Parsing node, each message was divided into individual words. These words were listed in a frequency matrix and words that contributed little to the understanding of the topic such as auxiliary verbs, conjunctions, determiners, interjections, participles, prepositions, and pronouns, were excluded from the analysis.

Following, a Text Filter node was used to exclude words that appeared in less than four messages, as a conservative measure to reduce noise. A single author with knowledge of the subject matter visually inspected and manually removed irrelevant terms. The words initially included (and excluded) in the analysis were visually inspected to ensure accuracy and identify unrecognizable symbols and letter groups for exclusion.41

With the inclusion criteria set, the Text Topic node was used to combine terms into topic groups. This clustering divided the document collection into groups based on the presence of similar topics using expectation maximization clustering. After visually examining each of the created topics, an eight-topic solution most clearly illustrated the main topics from the dataset. Lastly, the researchers reviewed the individual messages of the final topic groups to interpret the final groupings. This was accomplished by individually reviewing the actual messages from each cluster or topic to arrive at the description that appears in Table 1.

Results

The aim of this study was to examine topics in public COVID-19 vaccine-hesitancy discourse to help mitigate vaccine hesitancy and guide language in public health communication. In recognition of the widespread benefit to public health and considering the high risk associated with those individuals who remain unvaccinated, the results may be useful in accelerating vaccine acceptance. Thus, our first research question sought to identify topics in the COVID-19 hesitancy social media discourse. The eight topics that were extracted are presented in Table 1 and discussed in the following section as they relate to our research questions of interest.

Our second research question sought to understand if topics related to trust, mistrust, and distrust would emerge. As the most prominent topic identified in the social media data, vaccine acceptance rate was discussed in a Johns Hopkins study that reported declining acceptance amidst a pandemic of distrust. Additionally, the results show defeat as a topic term, and distrust is identified in the second topic's messaging when the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies describes the parallel pandemic. Issues of distrust can further be interpreted from the fourth through seventh topics which include concerns related to race, global rust, myths, and Russian interference.

The third research question related to topics of COVID-19 hesitancy and sought to reveal insight into who, if anyone, was mentioned as a trusted resource. These were slightly different from the third topic result, which in contrast highlighted an individual source, Dr William Schaffner. A vaccine specialist, Schaffner suggested that even primary care physicians have questions, but that politicians should trust in science. Other people and organizations mentioned included John Hopkins, Mr Rocca, the International Federation of Red Cross president, and Ogbonnaya Omenka, an associate professor and public health specialist. The third and fourth topics differed from the first two, with the third topic more positively highlighting the importance of trust versus the negative valence of the word distrust. The fourth topic identified in the discourse related to differences in hesitancy between races in an AP-NORC poll. The results reported that of Black Americans, only 22%, compared to 48% of white Americans, planned to get a COVID-19 vaccine. This topic indirectly focused on variance in trust across race. From both the personal and organizational voice, the fifth topic centered on building trust through leadership. In this topic, Mr Rocca, president of the International Federation of the Red Cross, states that trust is important to get people vaccinated and suggests community outreach as one tactic for building trust. In the sixth topic, an expert from British Columbia debunked perceived myths about the COVID-19 vaccines and said that the vaccines are safe. The seventh topic covers interest in the Russian COVID-19 vaccine and shows concern relating to its efficacy. The final and eighth topic, as mentioned previously, identified interest in a professor and public health expert in infectious disease who said vaccine hesitancy is normal during the time of containment.

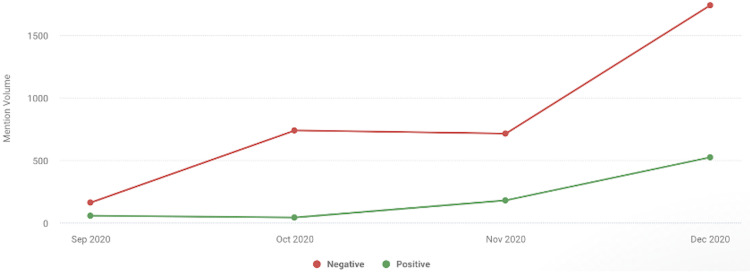

Topics in sentiment

Sentiment was the focus of the fourth and fifth research questions which sought to understand the change in sentiment over time and to explore topic by sentiment. Addressing RQ4, the volume of messages was found to increase in both positive and negative sentiment during the time period under investigation. Between September 1 and December 31, 2020, the number of posts captured on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and related topics appears to have increased (see Figure 1). This coincided with the COVID-19 vaccine becoming available in the United States when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.42 A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to analyze the effect of time (e.g. before and after vaccine availability) and sentiment (e.g. positive and negative) on volume. The results confirmed that both time (p = 0.02) and sentiment (p < 0.01) had a statistically significant effect on mention volume. Looking at sentiment data by volume and topic, the results show that while both positive and negative sentiment volume increased between November and December when the initial doses of the vaccine became available in the United States, negative sentiment volume occurred at an accelerated rate when compared to positive volume. The two-way ANOVA confirmed that this interaction was statistically significant (F(1, 93) = 11.31, p < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Hesitancy sentiment by time (September–December 2020).

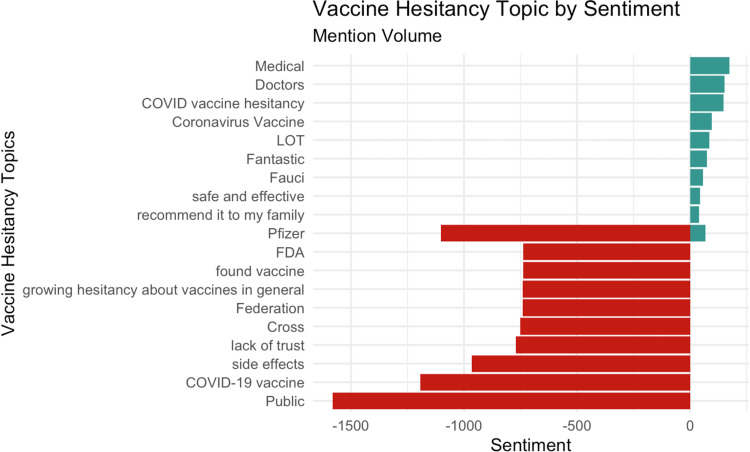

The final research question, RQ5, sought to measure the topics by sentiment (see Figure 2). Consistent with the RQ4 findings, negative sentiment dominated the results when being delineated by topic. Because the last research question sought to explore the topics by sentiment, a sentiment analysis was employed. Thus, the topics by sentiment are not identical to the topics in Table 1 because they are using a sentiment analysis to identify the emotional undertone in topics whereas a topic analysis is based only on subtopics regardless of emotion or opinion.

Figure 2.

Hesitancy topic by sentiment.

Looking at the hesitancy topics by sentiment illustrated how positive sentiment across topics were identified relating to vaccine recommendation among family, safety, and effectiveness, Dr Fauci, the vaccine, vaccine hesitancy, doctors, and medical terms. Interestingly, we see that Pfizer trends as both a positive and negative topic of interest in the hesitancy data. As shown in Figure 1, the volume of negative sentiment is larger when compared to the positive sentiment volume. The negative sentiment topics included the public, the vaccine, side effects, lack of trust, (Red) Cross, Federation, growing hesitancy, the FDA, and Pfizer.

By examining examples of the mentions that were identified in the negative sentiment, the results provide an additional lens to understand the voices, science, and opinions contributing to the conversations behind COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, topics, and sentiment trends (Table 2). The results also illustrate how the Boolean query (see Appendix) works to capture the conversations. One example provides context into vaccine hesitancy in general, tweeting that there is “growing hesitancy about vaccines in general, and about a Covid vaccine in particular” which highlight two heterogenous groups of vaccine-hesitant people who were likely vaccine hesitant prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and those who are specifically COVID-19 vaccine hesitant.

Table 2.

Negative topics by mentions.

| Topic group | Example mention |

|---|---|

| Pfizer | “(I am) oddly hesitant to let them inject me. Not sure why but I am positive it has something to do with Trump. I know Pfizer and Moderna refused to take part in Operation Warp Speed, and that's the only reason I will let them blast the stuff into me.” |

| FDA | “I wasn't going to hesitate taking the new COVID vaccine. But, now that I read the FDA must approve it today under threat of the FDA chief being fired, I'm very much inclined to wait.” |

| Found vaccine | “A PEW study found that 58% of African-Americans would not take the Covid vaccine. Local leaders in these communities say a lack of trust is the reason.” |

| Growing hesitancy about vaccines in general | “Mr Rocca said there was a growing hesitancy about vaccines in general, and about a Covid vaccine in particular.” |

| Federation | “Governments around the world need to combat ‘fake news’ around Covid-19 vaccines which has become ‘a second pandemic’, the International Federation of Red Cross president said.” |

| Cross | “Francesco Rocca, who works as president of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, appeared before the United Nations Correspondents on Monday in a virtual call where he endorsed Orwellian measures to prevent resistance to COVID-19 inoculations.” |

| Lack of trust | “A new study finds a lack of trust in a #COVID19 vaccine among Black and Latino communities. This sentiment isn't surprising but reflects a long history of mistreatment by the health community.” |

| Side effects | “I’m reluctant to get the covid vaccine cause it's so new. They don’t even know if a booster would be needed or what long term side effects might be. I would rather they didn’t learn all of that from me.” |

| COVID-19 vaccine | “Our effort is that everyone in our priority list takes COVID vaccine. We will address the issue of #vaccine hesitancy. But if anyone decides not to take it, we can't force them.” |

| Public | “Many, if not most, doctors and nurses are thrilled to have a COVID vaccine. But just like the public at large, some healthcare workers have doubts and fears.” |

A qualitative review of another tweet where the individual shares, “oddly hesitant to let them inject me. Not sure why but I am positive it has something to do with Trump. I know Pfizer and Moderna refused to take part in Operation Warp Speed, and that's the only reason I will let them blast the stuff into me” seems to support research suggesting that issues of trust also relate to the government.3 The user refers to being hesitant to let “them” inject him or her and go on to mention “operation warp speed” which suggests hesitancy related to the speed of the science and FDA approval on the vaccine. Additional narratives are illustrated with regard to African Americans, the Red Cross, and the novelty of the vaccine.

Discussion

Principal findings

Topics and sentiments of consumer interest related to vaccine hesitancy were identified using 14,901 social media mentions collected from Reddit and Twitter using the social media listening software, Brandwatch. SAS text miner was then used to identify 626 social media mentions that had an underlying relation to one another, particularly in an overlapping interest identified in the text. After exploring the data, specific attributes were identified in the results before being analyzed for sentiment with the aim of providing communication guidance to public health officials and indicating relevant topics of community concern regarding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Positive and negative emotions were considered because both are important to understanding how to effectively counteract unwanted negative attitudes while activating other positive feelings.6

Based on framing theory, previous literature has shown how positive and negative emotions can act as a frame for how people interpret incoming messaging.43 Previous studies examining emotion as a frame tend to conceptualize emotion as an exogenous variable, treating emotion as a consequence of the frame. The current study, instead, argues for the usefulness of emotion within the frame itself. The results contribute to the few studies that have considered the role of emotion in text, aside from examining how terms may evoke an emotion using survey-based methods. The results from this analysis can be used in health communication to frame subtopics of interest alongside emotionally resonant messaging to strategically disseminate COVID-19 vaccine information.

Because of the potential for emotion to mediate outcomes of message persuasion, behavior, and advocacy,3,8 specific topics were identified in the text. A topic like Pfizer, which was uniquely identified as having both a positive and negative emotional undertone, can offer an opportunity for strategic communicators to reach people in an emotionally resonant manner with both positive and negative framed messages. Because Pfizer was first-to-market in the United States, the brand may have gained initial loyalty among the eligible vaccine population. If the positive sentiment was related to brand loyalty, the results also suggest that those individuals who are least hesitant may place more trust in the Pfizer brand for vaccination. Positive sentiment may also be attributed to consumers who had previously used a biopharma product that had been produced by Pfizer and could have developed positive sentiment toward Pfizer through that exposure. Because Pfizer may play two roles, as both big pharma and a potentially life-saving vaccine, the company may be perceived as both positive and negative by different groups of people.

Voices of trust, especially those that have said vaccine hesitancy is normal during the time of pandemic containment, were identified as a topic of interest in the study. Interest in the source of the information seems to validate previous research that suggested sources to be important to mitigating vaccine hesitancy. Positive topics also emerged regarding the sources of information as being emotionally relevant, namely healthcare professionals, doctors, and government organizations. Broadly speaking, professional sources of politicians and primary care physicians were also relevant. Specific representatives included people like Dr Anthony Fauci, Dr William Schaffner, Professor Ogbonnaya Omenka, and Francesco Rocca, the president of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent. Taken together, the current study identified a variety of topics in the vaccine-hesitant social media conversation.

Practical implications

Recommending the vaccine to family members was identified as a positive topic of interest and can be used by health communicators as an emotionally resonant frame to mitigate the spread of negative sentiment and accelerate the rate of trust in vaccines. Personal narratives such as this example can be framed as an effective messaging tool to increase trust, mitigate hesitancy, and accelerate the speed of vaccination. Thus, health communicators can employ vaccine safety messaging in the context of a family member. This finding is consistent with a prepandemic study that found that among pediatricians, physicians who share personal anecdotes about family members can be effective in building vaccine-related trust in vaccine-hesitant families.44 As concerns among the public can range from hesitancy to refusal, healthcare staff and physicians can and do play an important role in framing COVID-19 information to educate people and change opinions.

In addition to distrust and skepticism, heterogeneous differences among vaccine-hesitant individuals have led to a disproportionate impact on racial and ethnic minorities.45 Coupled with the current study's findings which identified a “lack of trust” related to African Americans and Black Americans in the conversation, health communicators have an opportunity to build upon the momentum of public interest in the COVID-19 vaccines while addressing specific problems related to mistrust. Among underserved populations of interest, efforts should not solely focus on the historical inequities in the medical care of BIPOC (black, Indigenous, and people of color) communities but also address the systemic racial bias that exists in the current medical system.5 This suggestion extends from framing research which has shown that how information is presented not only affects how people interpret the message20–22 but also how they share it online.46 A practical example of this occurred when vaccine selfies were being shared by patients during and after their inoculation appointments. Thus, information can be positioned to appeal to diverse communities in both clinical settings as well as social media channels used by healthcare professionals.

Limitations and future research

Future research may employ Facebook as a research tool47 to accelerate the COVID-19 hesitancy literature and expand upon the results in the current study. Building upon the interests (e.g. family, Red Cross, etc.) and behaviors (e.g. philanthropy, family-friendly events, etc.) that were identified, topics and emotion could be used to reach vaccine-hesitant groups. Furthermore, as the current study suggests, there is an opportunity for future research to examine the relationship between sentiment and mention volume using these topics. Predictive analysis may also be useful in suggesting how the sentiment could amplify volume and sharing behaviors among vaccine-hesitant individuals.

The use of social media for data collection does introduce some limitations. A social media analysis can clarify users’ reactions toward a topic, but it is important to note that about 8-in-10 (80%) posts on Twitter come from about 1-in10 (10%) users.48 While the study may capture the opinions of a loud minority, this group of posters can be useful when considering online opinion leaders who influence other users. These other users may be especially useful when they are still hesitant and forming opinions about the COVID-19 vaccine. Additional limitations of the study relate to the sampling bias that occurs when querying English-speaking populations on social media. This excludes other languages making the sample less representative of the global population. Similarly, Facebook was not included in the study because the platform does not provide publicly available data. Thus, one should bear in mind that some naturally occurring sampling biases and errors can be introduced into the results. While we hope that the study is representative, future research may benefit from additional methods of study including international groups, self-report surveys, or qualitative research.

Conclusion

Topics of interest and emotional undertones were identified in information regarding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among a subset of online COVID-19-related hesitancy discourse. The research findings from the current study can be useful to improve message framing regarding vaccine acceptance, increase the rate of positive sentiment, and decrease hesitancy-related fear. Both negative and positive sentiments offer unique strategic opportunities for public health efforts. Because emotionally resonant frames tend to help improve how a message is received, the results can be used to improve advocacy and mitigate vaccine hesitancy. Moreover, the topics can combat downstream misinformation by appealing through message-relevant approaches to increase the overall share of voice in online conversation. Of course, there are some people who are strongly against the COVID-19 vaccine and no amount of information or strategic communication will change their minds. However, others are malleable and can be influenced by social norms and strategic communication. Thus, efforts can be used to effectively communicate with at-risk communities and drive desired behavior in hesitant populations.

Appendix

The Boolean query code for hesitancy data that was used to source social media discourse relating to COVID-19 hesitancy is included here. The aim is to include a comprehensive query that collects relevant mentions but does not include erroneous data or noise. The results from this query were received at a 100% sample rate, meaning this includes all publicly available mentions collected through the Twitter and Reddit API captured through the defined query during the time period under investigation.

(“Covid vaccine” NEAR/10 (hesitant OR hesitat* OR hesitancy OR reluctant*)) OR (“corona vaccine” NEAR/10 (hesitant OR hesitate* OR hesitancy OR reluctant*)) OR (“covid vaccination” NEAR/10 (hesitant OR hesitate* OR hesitancy OR reluctant*)) OR (“rona vaccine” NEAR/10 (hesitant OR hesitate* OR hesitancy OR reluctant*)) OR (“rona vaccination” NEAR/10 (hesitant OR hesitate* OR hesitancy OR reluctant*)) OR (“#covid19 vaccine” NEAR/10 (hesitant OR hesitate* OR hesitancy OR reluctant*))

Footnotes

Contributorship: This study was first conceptualized by MM and KLS. The development and data analysis was completed by KLS and GBW. The manuscript's first draft was completed by KLS and LB. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Kristen L. Sussman https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0704-6701

References

- 1.Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: A concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines (Basel) 2021; 9: 160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bureau USC. Household pulse survey covid-19 vaccination tracker. Census.gov. Retrieved October 14, 2022, from https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/household-pulse-survey-covid-19-vaccination-tracker.html. 2021, December 22.

- 3.Wernau J, Overberg P. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy complicates herd-immunity push. Wall Street Journal 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/covid-19-vaccine-hesitancy-presents-challenge-for-herd-immunity-push-11612369671#_=_. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mewhirter J, Sagir M, Sanders R. Towards a predictive model of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among American adults. Vaccine 2022; 40: 1783–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajaj SS, Stanford FC. Beyond Tuskegee – vaccine distrust and everyday racism. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: e12. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMpv2035827#article_citing_articles [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou WYS, Budenz A. Considering emotion in COVID-19 vaccine communication: Addressing vaccine hesitancy and fostering vaccine confidence. Health Commun 2020; 35: 1718–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robbins T, Hudson S, Ray Pet al. et al. COVID-19: A new digital dawn? Digital Health 2020; 6: 2055207620920083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dillard JP, Nabi RL. The persuasive influence of emotion in cancer prevention and detection messages. J Commun 2006; 56: S123–S139. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang A, Yegiyan NS. Understanding the interactive effects of emotional appeal and claim strength in health messages. J Broadcast Electron MEdia 2008; 52: 432–447. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ten threats to global health in 2019. World Health Organization. URL: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 [accessed 2020-12-31])

- 11.Stokes DC, Andy A, Guntuku SCet al. et al. Public priorities and concerns regarding COVID-19 in an online discussion forum: Longitudinal topic modeling. J Gen Intern Med 2020 Jul; 35: 2244–2247.. Medline: 32399912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abd-Alrazaq A, Alhuwail D, Househ Met al. et al. Top concerns of tweeters during the COVID-19 pandemic: Infoveillance study. J Med Internet Res 2020 Apr 21; 22: e19016.. Medline: 32287039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jang H, Rempel E, Roth Det al. et al. Tracking COVID-19 discourse on Twitter in North America: Infodemiology study using topic modeling and aspect-based sentiment analysis. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e25431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffith J, Marani H, Monkman H. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Canada: Content analysis of tweets using the theoretical domains framework. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e26874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hou Z, Tong Y, Du Fet al. et al. Assessing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, confidence, and public engagement: A global social listening study. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e27632. URL: https://www.jmir.org/2021/6/e27632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart SA, Abidi SSR. Applying social network analysis to understand the knowledge sharing behaviour of practitioners in a clinical online discussion forum. J Med Internet Res 2012; 14: e170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chong D, Druckman JN. Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science 2007; 10: 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerend MA, Shepherd JE. Using message framing to promote acceptance of the human papillomavirus vaccine. Health Psychol 2007; 26: 745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bigman CA, Cappella JN, Hornik RC. Effective or ineffective: attribute framing and the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Patient Educ Couns 2010; 81: S70–S76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iyengar S. Is anyone responsible?: How television frames political issues. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaller JR. The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson TE, Clawson RA, Oxley ZM. Media framing of a civil liberties conflict and its effect on tolerance. American Political Science Review 1997; 91: 567–583. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson MK. Joy: A review of the literature and suggestions for future directions. J Posit Psychol 2020; 15: 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander R, Aragón OR, Bookwala Jet al. et al. The neuroscience of positive emotions and affect: Implications for cultivating happiness and wellbeing. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021; 121: 220–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bean SJ. Emerging and continuing trends in vaccine opposition website content. Vaccine 2011; 29: 1874–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kata A. A postmodern Pandora's box: Anti-vaccination misinformation on the internet. Vaccine 2010; 28: 1709–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lerner JS, Keltner D. Fear, anger, and risk. J Pers Soc Psychol 2001; 81: 146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witte K, Allen M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ Behav 2000; 27: 591–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feldman Barrett L, Russell JA. Independence and bipolarity in the structure of current affect. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998; 74: 967. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bannister K. Sentiment analysis: How does it work? Why should we use it? Brandwatch 2018. https://www.brandwatch.com/blog/understanding-sentiment-analysis. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Odlum M, Cho H, Broadwell P, et al. Application of topic modeling to tweets as the Foundation for Health Disparity Research for COVID-19. Stud Health Technol Inform 2020 Jun 26; 272: 24–27. [Medline: 32604591]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nabi RL, Gustafson A, Jensen R. Framing climate change: Exploring the role of emotion in generating advocacy behavior. Sci Commun 2018; 40: 442–468. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Veer E, Ozanne LK, Hall CM. Sharing cathartic stories online: The internet as a means of expression following a crisis event. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 2016; 15: 314–324. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berger J, Milkman KL. What makes online content viral? Journal of Marketing Research 2012; 49: 192–205. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Labrecque LI. Fostering consumer–brand relationships in social media environments: The role of parasocial interaction. Journal of Interactive Marketing 2014; 28: 134–148. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park CW, MacInnis DJ, Priester Jet al. et al. Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. J Mark 2010; 74: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 37.The social suite of the future. Brandwatch. (n.d.). Retrieved October 14, 2022, from https://www.brandwatch.com/

- 38.Data Sources Included in Cision Social Listening | Next Gen English Global. (n.d.). Help.cision.com. Retrieved June 1, 2022, from https://help.cision.com/help/data-sources-included-in-cision-social-listening-csl

- 39.Brandwatch. (n.d.). Sentiment analysis. Brandwatch-Sentiment-Analysis.pdf. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://www.brandwatch.com/wp-content/uploads/brandwatch/Brandwatch-Sentiment-Analysis.pdf

- 40.Lafraniere S, Thomas K, Weiland Net al. et al. Politics, science and the remarkable race for a coronavirus vaccine. The New York Times. Retrieved October 14, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/21/us/politics/coronavirus-vaccine.html. 2020, November 21.

- 41.Chakraborty G, Pagolu M, Garla S. Text mining and analysis: Practical methods, examples, and case studies using SAS®. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas K, Weiland N, Lafraniere S. F.D.A. advisory panel gives Green Light to Pfizer vaccine. The New York Times. Retrieved August 4, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/10/health/covid-vaccine-pfizer-fda.html. December 10, 2020.

- 43.Nabi RL. Exploring the framing effects of emotion: Do discrete emotions differentially influence information accessibility, information seeking, and policy preference? Communic Res 2003; 30: 224–247. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kempe A, O’Leary ST, Kennedy Aet al. et al. Physician response to parental requests to spread out the recommended vaccine schedule. Pediatrics 2015; 135: 666–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CAet al. et al. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72: 703–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huete-Alcocer N. A literature review of word of mouth and electronic word of mouth: Implications for consumer behavior. Front Psychol 2017; 8: 1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kosinski M, Matz SC, Gosling SDet al. et al. Facebook as a research tool for the social sciences: Opportunities, challenges, ethical considerations, and practical guidelines. Am Psychol 2015; 70: 543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeRoo SS, Pudalov NJ, Fu LY. Planning for a COVID-19 vaccination program. JAMA 2020; 323: 2458–2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]