Summary

Symptom severity and prevalence of erosive disease in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) differ between genders. It is not known how gastroenterologists incorporate patient gender in their decision-making process. We aimed to evaluate how gender influences the diagnosis and management recommendations for patients with GERD. We invited a nationwide sample of gastroenterologists via voluntary listservs to complete an online survey of fictional patient scenarios presenting with different GERD symptoms and endoscopic findings. Patient gender for each case was randomly generated. Study participants were asked for their likelihood of a diagnosis of GERD and subsequent management recommendations. Results were analyzed using chi-square tests, Fisher Exact tests, and multivariable logistic regression. Of 819 survey invitations sent, 135 gastroenterologists responded with 95.6% completion rate. There was no significant association between patient gender and prediction for the likelihood of GERD for any of the five clinical scenarios when analyzed separately or when all survey responses were pooled. There was also no significant association between gender and decision to refer for fundoplication, escalate PPI therapy, or start of neuromodulation/behavioral therapy. Despite documented symptomatic and physiologic differences of GERD between the genders, patient gender did not affect respondents’ estimates of GERD diagnosis or subsequent management. Further outcomes studies should validate whether response to GERD treatment strategies differ between women and men.

Keywords: fundoplication, gender, GERD, reflux, survey

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has an estimated prevalence of 10–30% in the Western world and is argued to be the most common disease seen by gastroenterologists in the United States.1–3 Clinicians make the diagnosis of GERD based on a combination of factors, including patient reported symptoms, response to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, endoscopy showing evidence of erosive esophagitis, and ambulatory reflux monitoring.2,4 Along with these variable methods of diagnosis, another complication for clinicians encountering patients with reflux symptoms is the well-documented difference that exists between the genders in both the reporting of symptoms and in the findings on diagnostic tests.5 Women have been found to have higher rates and severity scores for GERD symptoms compared to men but a lower prevalence of erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus found on endoscopy.3,6 One plausible physiologic factor for this difference is that estrogen has been shown to decrease esophageal epithelial permeability and upregulate tight junction protein expression, protecting the esophagus from irritants.7,8 Conversely, the threshold for esophageal nociception may be lower in females when using balloon distention as a provocation maneuver.9

A systematic review of studies that examined rates of consultations, reflux testing, endoscopy findings, and fundoplication referrals found that women in the United States were more likely to undergo ambulatory reflux testing than men and slightly more likely to undergo fundoplication, the surgical treatment for GERD.10 Notably, these studies were not designed to specifically examine the physician management differences and referral patterns for patients with GERD, nor were gender differences the primary research questions.

Given that guidelines for further testing and treatment in refractory GERD do not differentiate between the genders,2,4 it is not clear why there may be a documented difference in the management of male and female patients presenting with refractory GERD symptoms. Prior studies have shown gender disparities in the rates of referral for certain orthopedic surgeries, wherein men with shoulder injury and knee osteoarthritis are more likely to be referred for shoulder surgery and total knee arthroplasty, respectively, as compared to women with the same pathology.11,12 Similarly, a recent study found differences in physician estimates of complications after lung resection related to physician gender and patient gender.13 While it is not yet known if diagnostic and treatment strategies differ between male and female patients with GERD, gender bias in the treating physician’s perception of patient symptoms and gender disparities in referral recommendations may play a role. We aimed to evaluate how patient gender influences the diagnosis and management of GERD.

METHODS

Study design, sampling strategy, and study population

We invited gastroenterology physicians throughout the United States to complete an online survey that used non-random, convenience sampling between September 2018 and April 2019. Gastroenterology trainees were not included as participants. The survey was distributed via online professional email listservs to which each physician has voluntarily subscribed. Online listservs were society-specific (e.g. American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society) and role-specific (e.g. gastroenterology fellowship program directors). Potential respondents were sent an email inviting them to complete the online survey. The following text was included in the email and in the cover page of the survey: ‘The purpose of this survey is to elucidate how doctors manage patients with GERD. The survey presents five short clinical presentations. After reading the case, you will decide the likelihood this patient has GERD and then select which management option you would most likely pursue, if you were seeing that patient in your office. Completion of the survey should take no more than 5 minutes. Participation in this survey is optional. No compensation will be provided. Answers are fully anonymous and no identifying information can be linked back to your email address.’ No mention of patient gender was made in the email or in the survey cover page.

Survey design and data collection

Web-mode survey administration was conducted using SurveyMonkey. The online survey consisted of five fictional clinical scenarios of patients with GERD symptoms and was designed such that the gender of each clinical scenario was randomly generated for each separate study participant and each separate scenario in a 1:1 ratio. The five scenarios were distinct in terms of location of symptom (esophageal or extra-esophageal), response to PPI, presence or absence of esophagitis, and presence or absence of a hiatal hernia. For each clinical scenario, respondents were asked for their clinical suspicion of GERD (high probability vs. low probability) and subsequent management recommendation, which could include doubling the PPI dose, referral for reflux testing on PPI, referral for reflux testing off PPI, referral for fundoplication, starting adjunct medication such as baclofen, referral to a behavioral therapist, esophageal manometry, or starting a low-dose antidepressant. Referral for fundoplication was included as an option for every scenario. The complete questionnaire is included in the supplemental material.

In addition to survey responses to the fictional clinical scenario, we collected demographic data from survey participants including age group, gender, type of practice (academic institution, private practice, hybrid model, or other), years in practice, specialty within gastroenterology, and region of the country where the physician practices.

Statistical analysis

We used univariable analysis with Pearson chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact tests to compare between the genders the binary outcomes of high probability versus low probability for GERD, surgical referral versus other management strategies, a respondent’s decision to choose PPI escalation, and initiation of neuromodulator or behavioral therapy versus other strategies. We additionally used multivariable logistic regression to determine if survey respondent gender was associated with prediction of likelihood for GERD and recommendation for surgical referral. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University.

RESULTS

Surveys were sent to 819 gastroenterologists. We obtained 135 responses, with a 95.6% completion rate (response rate 16.5%). Of the 126 respondents who provided demographic data, 62.4% were men, 46.0% were between the ages of 30 and 40 years (46.0%), 76.2% practice at an academic institution, and 46.4% practice general gastroenterology, while 35.2% specialize in motility disorders. The demographic data of survey respondents is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of survey participants (N = 135)*

| Characteristics | Survey participants (N, %) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 30–40 | 58 (46.0) |

| 41–50 | 26 (20.6) |

| 51–60 | 21 (16.7) |

| 61–75 | 19 (15.1) |

| >75 | 2 (1.6) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 47 (37.6) |

| Male | 78 (62.4) |

| Type of practice | |

| Academic institution | 96 (76.2) |

| Private practice | 14 (11.1) |

| Hybrid model | 14 (11.1) |

| Other | 2 (1.6) |

| Years in practice | |

| <5 | 43 (34.4) |

| 5–10 | 29 (23.2) |

| 11–20 | 12 (9.6) |

| >20 | 41 (32.8) |

| Specialty | |

| General gastroenterology | 58 (46.4) |

| Interventional gastroenterology | 10 (8.0) |

| Motility/esophageal | 44 (35.2) |

| Other | 13 (10.4) |

| Region | |

| Northeast | 61 (48.8) |

| Midwest | 21 (16.8) |

| South | 19 (15.2) |

| West | 24 (19.2) |

*Nine participants did not provide demographic data on age or type of practice; 10 participants did not provide data on gender, years out of practice, specialty, or region.

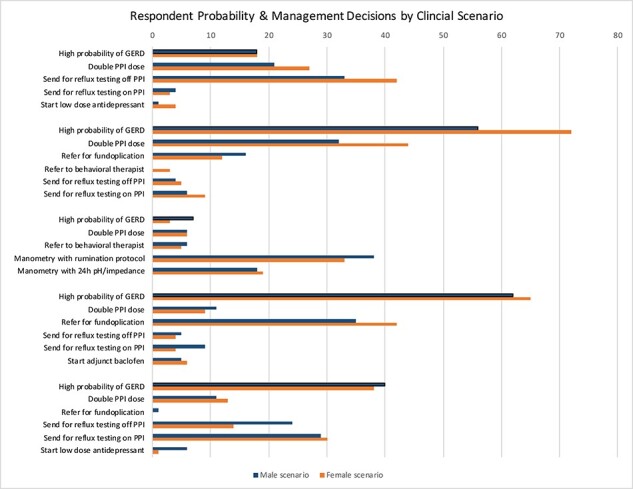

Fig. 1.

Respondent prediction for probability of GERD and management decisions by clinical scenario.

Overall, respondents thought there was a high probability of a GERD diagnosis for 58.5% of the female scenarios and 57.0% of the male scenarios (P = 0.87). For each distinct clinical scenario, there was no significant difference in physician clinical suspicion of GERD based on patient gender (Table 2). Physicians had a high level of agreement with one another on the probability of GERD in the cases of erosive esophagitis with hiatal hernia (97.7% agreement for high probability), erosive esophagitis without hiatal hernia (99.2% agreement for high probability), and non-erosive regurgitation (92.4% agreement for low probability). Physicians had less consistent clinical suspicion of GERD in the cases of non-erosive esophagitis without a hiatal hernia (73.3% low probability) and extra-esophageal reflux (60.5% high probability). Respondent gender was not associated with the prediction of likelihood of GERD in any of the five clinical scenarios.

Table 2.

Univariable analysis of high pretest probability of GERD by clinical scenario and gender

| Subjects indicating a high pretest probability of GERD (N, %) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Esophageal symptom, non-erosive, no hernia’ | 0.374 | |

| Male scenario | 18 (30.5) | |

| Female scenario | 18 (23.7) | |

| ‘Esophageal symptom, erosive with hernia’ | 0.430 | |

| Male scenario | 56 (96.6) | |

| Female scenario | 72 (98.6) | |

| ‘Non-erosive regurgitation’ | 0.234 | |

| Male scenario | 7 (10.3) | |

| Female scenario | 3 (4.8) | |

| ‘Esophageal symptom, erosive, no hernia’ | 0.492 | |

| Male scenario | 62 (98.4) | |

| Female scenario | 65 (100.0) | |

| ‘Extra-esophageal reflux symptom’ | 0.289 | |

| Male scenario | 40 (56.3) | |

| Female scenario | 38 (65.5) |

In the three clinical scenarios where survey respondents chose fundoplication as a management strategy, there were no significant differences in the referral patterns by patient gender (Table 3). In the erosive esophagitis with hiatal hernia case, survey respondents recommended fundoplication for 16 of 58 male patients (27.6%) and 12 of 73 female patients (16.4%, P = 0.122). In the erosive esophagitis case without hiatal hernia, 35 of 66 male patients (53.0%) and 42 of 65 female patients (64.6%, P = 0.357) were recommended for referral for antireflux surgery. One respondent recommended fundoplication for a male patient with extra-esophageal reflux, while no female patients in this clinical scenario were recommended for surgery. As was seen in the analysis of predicting the likelihood of GERD, survey respondent gender was also not associated with making a recommendation for surgical referral for any of the three clinical scenarios where fundoplication was recommended. In the remaining two clinical scenarios, respondents did not recommend any fictional patients be referred for antireflux surgery.

Table 3.

Univariable analysis of surgical referral versus medical management of GERD by clinical scenario gender (including only cases where surgical referral was selected as a strategy)

| Subjects referred for surgery (N, %) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Esophageal symptom, erosive with hernia’ Male scenario Female scenario |

16 (27.6) 12 (16.4) |

0.122 |

| ‘Esophageal symptom, erosive, no hernia’ Male scenario Female scenario |

35 (53.0) 42 (64.6) |

0.178 |

| ‘Extra-esophageal reflux symptom’ Male scenario Female scenario |

1 (1.5) 0 (0.0) |

0.357 |

Among the 129 respondents with complete surveys, 74 (57.3%) recommended escalation of PPI therapy in at least one female patient, and 62 (48%) recommended PPI escalation in at least one male patient (P = 0.170). Similarly, among the four vignettes in which antidepressant or behavioral therapy was an option, there was no difference in the proportion of respondents ever recommending this option for female patients (8.5%) compared to male patients (9.3%, P = 0.999).

DISCUSSION

GERD is a highly prevalent condition and whether providers formulate management plans based on patient demographics, symptom description, or results of testing is unclear. Given that the clinical presentation and natural history of GERD can be disparate between the genders (i.e. males are more likely to present with erosive esophagitis/Barrett’s esophagus, and females are more likely to present with more symptomatic but non-erosive disease), we aimed to determine whether a patient’s gender influenced the physician diagnostic and management decisions. In this survey of a nationwide sample of gastroenterologists with fictional clinical scenarios, patient gender was not significantly associated with the clinical suspicion of GERD. It was expected that gender did not influence the probability of GERD in the scenarios with erosive esophagitis, as it is a GERD equivalent. Interestingly, however, we also did not find a difference in the non-erosive cases. We had hypothesized that physicians would assume lower probability in female scenarios owing to the well described overlap between functional disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome and GERD symptoms in female patients.14,15 Instead, our findings are consistent with Spechler et al.’s16 recent randomized study of patients with refractory reflux symptoms, which found that the rate of reflux-related symptoms versus functional heartburn defined by ambulatory pH testing was indeed no different between the patient genders, although the majority of the study population was comprised of male participants.

Due to the relative lack of robust GERD outcomes studies in the last 10 years, we theorized that physicians may instead use personal experience to determine management decisions and thus have the potential to be subject to unintended biases. As an example, popular media reports of potential long-term PPI risks have led some patients and providers to avoid high-dose PPI strategies despite the low-quality evidence supporting these risks, and female patients are slightly more likely to have attempted to discontinue PPI therapy.17–19 As a result, physicians may avoid escalation of PPI dose in women due to perceived risk of osteoporosis and bone fracture. Conversely, they may favor PPI escalation in men, given its role for chemoprevention in Barrett’s esophagus, even when the patient is not presenting with Barrett’s.20 We also thought bias could influence surgery referral as described in other fields,11–13 or the decision to start antidepressants/behavioral therapy, in light of proclivity to interpret female symptoms as ‘psychosomatic’ as illustrated in the medical literature.21 However, we found that gender was not significantly associated with the management decisions offered in our survey, whether it be referral for antireflux surgery, escalation of PPI therapy, or decision to attempt neuromodulation/behavioral therapy. One possible explanation is that respondents instead often chose to send patients for further testing, either ambulatory reflux testing or manometry, in 50% of the cases, which shows a rising awareness of factors other than acid exposure, namely, visceral hypersensitivity, anxiety, and hypervigilance.22 These factors highlight the importance of reflux testing in defining the etiology of refractory GERD.23

This is the first study attempting to determine the role of patient gender in physicians’ decision-making in the diagnosis and management of GERD. Our survey was designed to include a variety of scenarios that are clinically relevant, including variable symptom presentations and endoscopic findings. By randomizing gender in each scenario, we attempted to determine its influence in a ‘real-life’ setting. While this study is strengthened by participation from a diverse group of gastroenterologists from a variety of practice settings and regions, we recognize several limitations. Live standardized patients would likely be more effective in creating scenarios closer to real-life practice settings. However, prior studies have shown that clinical vignettes may offer better quality measures of care over retrospective medical chart reviews.24 While any power calculation for this study is limited by a lack of prior work in this specific question, it is possible our study was underpowered to detect a significant difference in the management strategies between the genders due to a lower-than-expected response rate, which occurred despite attempts at optimizing the response numbers by making the survey being web-based and brief. It is also not possible to know whether the participants were adequately ‘primed’ to the patient’s gender when presented with the clinical vignette. Finally, given the high percentage of respondents who specialize in motility disorders and due to the study population being drawn from those subscribed to online listservs, these results may not be generalizable to the general population of gastroenterologists.

Our survey of a national sample of gastroenterologists shows that while the symptoms and manifestations of GERD differ between the male and female patients, physicians may not incorporate gender into either their estimation of probability of GERD or into their management decisions. Despite this finding, physicians should remain aware of potential biases when diagnosing and managing prevalent and protean disorders. Objective testing to determine not only acid exposure but the contribution of afferent nerve sensitization may reduce these biases and guide management decisions. Finally, future outcomes studies should validate whether response to GERD treatment strategies differ between women and men.

Specific author contributions: Study concept and design: Anna Krigel, Benjamin Lebwohl, Rena Yadlapati, Daniela Jodorkovsky; Acquisition of data: Anna Krigel, Daniela Jodorkovsky; Analysis and interpretation of data: Anna Krigel, Benjamin Lebwohl, Rena Yadlapati, Daniela Jodorkovsky; Drafting of the manuscript: Anna Krigel, Daniela Jodorkovsky; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Anna Krigel, Benjamin Lebwohl, Rena Yadlapati, Daniela Jodorkovsky; Statistical analysis: Anna Krigel; Study supervision: Daniela Jodorkovsky; Approval of final draft submitted and the authorship list: Anna Krigel, Benjamin Lebwohl, Rena Yadlapati, Daniela Jodorkovsky.Financial support: Benjamin Lebwohl was supported by the Louis and Gloria Flanzer Philanthropic Trust.Potential competing interests: Rena Yadlapati is the consultant for Medtronic, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Diversatek, Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Research support was provided by Ironwood. RJS Mediagnostix was the advisory board with stock options.Details of ethics approval: This analysis was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University.

Contributor Information

Anna Krigel, Department of Medicine, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, USA.

Benjamin Lebwohl, Department of Medicine, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, USA; Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, USA.

Rena Yadlapati, Department of Medicine, UC San Diego School of Medicine, San Diego, CA, USA.

Daniela Jodorkovsky, Department of Medicine, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, USA.

References

- 1. Dent J, El-Serag H B, Wallander M A, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-esophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut 2005; 54(5): 710–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Katz P O, Gerson L B, Vela M F. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(3): 308–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Delshad S D, Almario C V, Chey W D, Spiegel B M R. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease and proton pump inhibitor-refractory symptoms. Gastoenterology 2020; 158(5): 1250–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gyawali C P, Kahrilas P J, Savarino E et al. Modern diagnosis of GERD: the Lyon consensus. Gut 2018; 67(7): 1351–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim Y S, Kim N, Kim G H. Sex and gender differences in gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2016; 22(4): 575–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lin M, Gerson L B, Lascar R, Davila M, Triadafilopoulos G. Features of gastroesophageal reflux disease in women. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99(8): 1442–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim J J, Kim N, Park J H et al. Comparison of tight junction protein related gene mRNA expression levels between male and female gastroesophageal reflux disease patients. Gut Liver 2018; 12(4): 411–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Honda J, Iijima K, Asanuma K et al. Estrogen enhances esophageal barrier function by potentiating occluding expression. Dig Dis Sci 2016; 61: 1028–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nguygen P, Lee S D, Castell D O. Evidence of gender differences in esophageal pain threshold. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90(6): 901–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nusrat S, Nusrat S, Bielefeldt K. Reflux and sex: what drives testing, what drives treatment? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 24(3): 233–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Razmjou H, Lincoln S, Macritchie I, Richards R R, Medeiros D, Elmaraghy A. Sex and gender disparity in pathology, disability, referral pattern, and wait time for surgery in workers with shoulder injury. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016; 17(1): 401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Borkhoff C M, Hawker G A, Kreder H J, Glazier R H, Mahomed N N, Wright J G. The effect of patients’ sex on physicians’ recommendations for total knee arthroplasty. CMAJ 2008; 178(6): 681–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferguson M K, Huisingh-Scheetz M, Thompson K, Wroblewski K, Farnan J, Acevedo J. The influence of physician and patient gender on risk assessment for lung cancer resection. Ann Thorac Surg 2017; 104(1): 284–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lovell R M, Ford A C. Prevalence of gastro-esophageal reflux-type symptoms in individuals with irritable bowel syndrome in the community: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107(12): 1793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Choung R S, Richard Locke G III, Schleck C D, Zinsmeister A R, Talley N J. Multiple functional gastrointestinal disorders linked to gastroesophageal reflux and somatization: a population-based study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017; 29(7): e13041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spechler S J, Hunter J G, Jones K M et al. Randomized trial of medical versus surgical treatment for refractory heartburn. N Engl J Med 2019; 381(16): 1513–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Freedberg D E, Kim L S, Yang Y X. The risks and benefits of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: expert review and best practice advice from the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology 2017; 152(4): 706–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kurlander J E, Kennedy J K, Rubenstein J H et al. Patients’ perceptions of proton pump inhibitor risks and attempts at discontinuination: a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol 2019; 114(2): 244–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kurlander J E, Rubenstein J H, Richardson C R et al. Physicians’ perceptions of proton pump inhibitor risks and recommendations to discontinue: a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol 2020; 115(5): 689–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jankowski J A Z, de Caestecker J, Love S B et al. Esomeprazole and aspirin in Barrett’s oesophagus (AspECT): a randomised factorial trial. Lancet 2018; 392(10145): 400–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Samulowitz A, Gramyr I, Eriksson E, Hensing G. “Brave men” and “emotional women”: a theory guided literature review on gender bias in health care and gendered norms toward patients with chronic pain. Pain Res Manag 2018; 2018: 6358624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Katzka D A, Pandolfino J E, Kahrilas P J. Phenotypes of gastroesophageal reflux disease: where Rome, Lyon, and Montreal meet. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18(4): 767–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yadlapati R, Pandolfino J E. Personalized approach in the work-up and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2020; 30(2): 227–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Veloski J, Tai S, Evans A S, Nash D B. Clinical vignette-based surveys: a tool for assessing physician practice variation. Am J Med Qual 2005; 20(3): 151–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]