Abstract

Due to the advantageous characteristics of laser welding technology, it is being increasingly used for constructing stainless steel rail vehicles. It can improve the appearance of a vehicle, enable designs with a relatively high degree of flatness, and ensure higher-quality connections between different parts of a vehicle. Moreover, it can improve the strength and stiffness of the components of the vehicle. In this study, a large-scale assembly module of a stainless steel side-wall was considered as the research object. The combined heat source model of a Gaussian heat source and a cylindrical volume heat source was used to obtain the heat source parameters of laser welding to match the experimental data. Based on the thermal cycle curve method (TCCM), the influence of the number of weld segments and mesh divisions of the local model on the efficiency and accuracy of laser welding simulations was investigated. Thereafter, the research results were applied to the welding simulation of the whole side-wall module. The shape of the molten pool obtained using the combined heat source was closer to that of the experiments (error < 10%), demonstrating the accuracy and effectiveness of the developed the heat source model for laser welding simulation. For local model laser welding using the TCCM, a coarse mesh was used, and the weld was divided into four segments, and highly accurate results were obtained. This calculation time was only 5.97% of that of a moving heat source in case of the thermo-elastic-plastic method (TEPM). Residual stress and welding deformation of the stainless steel side-wall module were calculated according to actual process parameters and the results of local model simulation. Residual stress was discontinuously distributed at the weld segments, and it only slightly influenced the overall stress distribution. The maximum residual stress (462.15 MPa) occurred at the weld of the large crossbeam. Welding eight small and two large crossbeams influenced the deformation change and the maximum deformation (1.26 mm) appeared in the middle position of the left side-wall. The findings of this study show that the TCCM has high calculation accuracy and is sufficiently economical for predicting laser welding of large structures.

Keywords: Large-scale, Stainless steel side-wall, Laser welding, Combined heat source, Thermal cycle curve method

1. Introduction

Laser welding is an emerging welding process; it is widely used in rail vehicles, aerospace, energy, and other fields because of its advantages such as small welding deformation, green protection, and high efficiency. In rail vehicles, stainless steel side-walls are large structures that require high flatness. Due to the problem of indentation in the traditional spot welding process, it has been replaced gradually by laser welding in recent years for manufacturing stainless steel side-walls. Laser welding has certain advantages over traditional spot welding in terms of deformation control. However, it also has a high thermal cycle efficiency with a more intense melting and solidification process, which leads to residual deformation problems and influences the geometric and mechanical properties of the side-walls. Therefore, numerical simulations are being used for predicting welding deformation and residual stress, mastering their distribution laws, and optimizing the welding process for improving production efficiency, as these are key considerations in the manufacturing development of stainless steel vehicles.

Contemporary simulation techniques for laser welding of large-scale components suffer from issues such as long computational time, insufficient computational accuracy, and computational convergence [1]. Some typical numerical simulation methods include the thermo-elastic-plastic method (TEPM), the inherent strain method (ISM), shrinkage force method (SFM), similarity theory method (STM), and local-global mapping method (LGMM) [[2], [3], [4]]. Wu et al. [5] investigated the dual laser beam bilateral synchronous welding process of an Al–Li alloy skin-stringer structure using the TEMP. They simulated residual stresses and deformations of large thin-walled structures of aircraft fuselage. Tang et al. [6] numerically simulated the laser hybrid welding deformation of metro traction beams using the ISM and they investigated the influence of different values of constraints on welding deformation and compared them with experiments to obtain optimized constraint schemes. Song et al. [7] successfully predicted the welding deformation of the aluminum alloy side-walls of a high-speed train under different welding sequences and constraint modes using the ISM. Xu et al. [8] applied the SFM to predict the welding distortion of deck block structures. This calculation process of welding distortion in engineering structures was easy to converge, and it significantly improved the calculation efficiency. Chen et al. [9] studied the welding numerical simulation of a spiral case stay ring using the STM. Zhang et al. [10] calculated and analyzed the deformation of a steam turbine cylinder sub-component using the LGMM. The computational results provided technical guidance and theoretical support for the safety assessment of large complex thin plate welding structures. Chang et al. [11] proposed and validated a finite element simulation method that combined local thermo-elastic-plastic and local-global mapping and predicted welding deformation and residual stress of large-scale diversion tubes. The TEPM has certain advantages in terms of computational accuracy and can accurately determine the welding deformation and residual stress. However, its modeling process is complex because it requires defining a large number of welding paths and thermodynamic boundary conditions. It has a long modeling cycle and low computational efficiency compared to the ISM [12,13]. In the ISM, the inherent strain value of the welded joint should be first obtained, followed by elastic calculation of welding deformation. This process seriously affects the accuracy of welding deformation simulation, and it cannot provide the accurate value of the residual stress. The SFM cannot be used to analyze the evolution of stress and deformation in the welding process because it is highly simplified and does not consider the welding heating and cooling processes. Although the simplified model can reduce the amount of calculation and cost to some extent, the application of the STM in welding still needs to be further studied because some parameters are not accurately equivalent. While the LGMM can quickly predict the welding deformation of complex structures, few studies have investigated LGMM for laser welding simulation.

With advances in the numerical simulation of welding, the TCCM is being increasingly used for predicting welding simulation for large-scale structures. TCCM considers computational accuracy as well as efficiency, and it can predict welding deformation efficiently and obtain more accurate values of the residual stress for large structures. Wu et al. [14,15] established a segmented moving combined welding heat source model using TCCM with control variables. They efficiently completed thermo-elastic-plastic finite element analysis of the excavator boom, demonstrating that the TCCM has high calculation accuracy and is suitable for welding simulation of large and complex components. Dai et al. [16] performed deep penetration laser welding of thick plates on the magnet system of the bottom and top correction coils (BTCC) model. They demonstrated that the combined model was suitable for laser welding of a plate with a thickness of 18 mm. The welding deformation of the global structure was simulated using the TCCM. Limited studies have investigated laser welding deformation of side-wall modules of stainless steel rail vehicles based on the TCCM, and even fewer studies have conducted residual stress analysis.

In this study, based on heat source calibration and comparative analysis, using the TCCM, the influence of calculation efficiency and accuracy for different number of laser welding segments and mesh division schemes on the local model was investigated. The welding residual stress and welding deformation of the side-wall module of a stainless steel vehicle were determined, providing insights for laser welding control and process optimization of large components of rail vehicles.

2. Fundamental principle

2.1. Thermal cycle curve method

The TCCM is a highly efficient method for welding simulation calculation based on a segmented moving heat source. By applying TCCM to a weld, the temperatures of all nodes within the weld were replaced by thermal cycle curves. All nodes within the weld were heated and cooled simultaneously to simulate the welding process of the entire length of a weld, which improved the efficiency of the welding simulation calculation. While the maximum temperature of the thermal cycle curve was different for the same workpiece at different locations, the form of the thermal cycle was essentially the same, as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Thermal cycle curve.

The temperature of other nodes at other time is determined using Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where represents material density, represents the specific heat capacity, represents the heat transfer time, represents the temperature distribution function, , , and represent thermal conductivity in the , , and directions, respectively.

This method improves the accuracy and efficiency of welding simulation and facilitates further analysis, while reducing the large number of computation processes.

2.2. Heat source model

The heat source model is a basic condition in welding simulation, and its the accuracy of a heat source model directly affects the accuracy of the numerical simulation results. Weld section morphology in laser welding contains a bowl-shaped feature of conduction welding as well as nail-shaped or columnar features of deep penetration welding. Therefore, selection of its heat source model is a rather complex process. There has been extensive research on laser welding heat source models. Wu et al. [17] proposed a Rotary-Gauss body heat source model that was better adapted to the nail head shaped welds for deep fusion welding with high energy beams. Kim et al. [18] established a new circular cone type heat source model that can more accurately simulate the melting pool morphology of single-pass laser welding of T-joints. Bendaoud et al. [19] achieved 20 mm thick duplex stainless steel laser-arc hybrid Y-shape prediction by building a double ellipsoid-Goldak cone hybrid heat source model. Kubiak et al. [20] proposed a super-Gaussian distributed heat flux density function for simulating Yb:YAG laser welding. Zhao et al. [21] used a new combined heat source model of a Gaussian surface heat source with a self-adaptive body heat source to numerically simulate double-sided laser simultaneous welding of T-joints. The simulation results were in good agreement with the experimental measurements. Wu et al. [22] proposed a volumetric heat source distribution mode combined “double ellipsoidal” and “linearly-increased peak value cylinder” according to the characteristics of laser + GMAW hybrid heat source welding. The heat source was used to verify the advantages of the laser + GMAW composite welding process.

In this study, a combined heat source model of Gaussian surface + cylindrical volume hybrid heat source was used, which can meet the requirements of the full range of simulation [23]. The heat flow distribution of Gaussian surface heat source , and cylindrical volume heat source , are given using Eqs. (2), (3), (4).

| (2) |

| (3) |

| Q = QS + Qv | (4) |

where r represents the distance from the heating center, R represents the effective heating radius of the laser, H represents the effective depth of the cylindrical volume heat source, represents the total heating power, represents the Gaussian surface heat source power, and represents the cylindrical volume heat source power. , , and represents the proportionality factor.

3. Laser welding heat source calibration

The stainless steel side-wall is made of SUS301L, and the relevant parameters are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2, Fig. 3.

Table 1.

Property of SUS301L.

| Material | Poisson ration | Density/kg·m−3 | Solidus temperature/ | Melting temperature/ | Latent heat/J·kg−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUS301L | 0.3 | 7900 | 1280 | 1450 |

Fig. 2.

Thermal performance parameters: (a) thermal conductivity, (b) specific heat capacity, (c) coefficient of thermal expansion.

Fig. 3.

Mechanical property parameters: (a) elasticity modulus, (b) yield strength, (c) shear modulus.

The joint type of side-wall laser welding was overlap joint. According to the thickness of the plate, two overlap joints were investigated with a weld length of 100 mm (thickness = 0.8 mm + 1.5 mm and 1.5 mm + 1.5 mm), and they were labeled as T01 and T02, respectively (Fig. 4(a and b)).

Fig. 4.

Model of overlap joint: (a) geometry dimension, (b) 3D model.

According to the welding process parameters in Table 2, laser welding heat source calibration was simulated using the combined Gaussian heat source + cylindrical volume heat source.

Table 2.

Process parameters.

| Weld joint | Welding power/W | Welding speed/m·min−1 | Defocus/mm |

|---|---|---|---|

| T01 | 3000 | 4.8 | +4 |

| T02 | 3500 | 4.2 | +4 |

After repeated debugging, the heat source calibration results matched the actual molten pool shape from measurement data given in Refs. [23,24] for laser welding of both joints. The measurement positions of molten pool and comparison results are shown in Fig. 5, Fig. 6.

Fig. 5.

Characterization parameters of weld pool.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of molten pool boundary.

Fig. 6 showed that the simulation calculation of the T01 heat source calibration was in good agreement with the experimental results and satisfied the molten pool boundary criteria (T02 had the similar molten pool boundary, but the surface weld width, middle weld width, and weld penetration were larger than T01 as shown in Table 3, Table 4). Relative errors of the simulated surface weld width, middle weld width, and weld penetration for the T01 and T02 joints, compared with the experimental tests, were 6.10%, 6.67%, and 2.17%, and 1.94%, 1.19%, and 2.12%, respectively.

Table 3.

Comparison of simulation and experimental results of T01.

| Surface weld width | Middle weld width | Weld penetration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | 1.39 mm | 0.80 mm | 1.41 mm |

| Simulation | 1.31 mm | 0.75 mm | 1.38 mm |

| Deviation | 6.10% | 6.67% | 2.17% |

Table 4.

Comparison of simulation and experimental results of T02.

| Surface weld width | Middle weld width | Weld penetration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | 2.02 mm | 0.85 mm | 2.31 mm |

| Simulation | 2.06 mm | 0.84 mm | 2.36 mm |

| Deviation | 1.94% | 1.19% | 2.12% |

According to the heat source calibration results, the various heat source parameters of the finalized combined heat source are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Shape parameters of the heat source model.

| Weld joint | Radius of volume heat source/mm | Depth of volume heat source/mm | Gauss parameter of volume heat source | Radius of surface heat source/mm | Depth of surface heat source/mm | Gauss parameter of surface heat source | Ratio coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T01 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 3 | 1 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.8 |

| T02 | 1 | 2.4 | 3 | 3 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.75 |

Thermal cycle curves were extracted at the center point location of the weld (Fig. 7(a,d)). Then the thermal cycle curves were normalized with the highest temperature as the standard (Fig. 7(b,e)). Compared with welding temperature field distribution characteristics, the normalized coefficient was adjusted to 1.2 to obtain the normalization table (Fig. 7(c,f)). Applied normalization table on all nodes of the weld for welding simulation. The detailed description is as presented in Ref. [25].

Fig. 7.

Extraction process of thermal cycle curves: (a)T01 thermal cycle curve, (b)T01 normalization curve, (c)T01 extraction table of normalization curve, (d)T02 thermal cycle curve, (e)T02 normalization curve, and (f)T02 extraction table of normalization curve.

4. Determination of the number of segments and mesh divisions using the TCCM

Based on the principle of the TCCM introduced in section 1.1, the number of segments and coarse or fine meshes considerably influence welding accuracy and the efficiency of numerical simulation. Infinite number of segments and fine mesh divisions can result in welding simulation with high calculation accuracy but low calculation efficiency. To determine the appropriate number of segments and coarse or fine mesh division settings, a small crossbeam (thickness = 0.8 mm and length = 640 mm) from the side-wall components was selected for simulation analysis.

The small crossbeam division model had two types of meshes, coarse and fine mesh. A fine mesh is shown in Fig. 8(a); the minimum mesh size at the weld joint was 0.8 mm × 0.25 mm × 0.27 mm (elements = 160,038, nodes = 235,704). A coarse mesh is shown in Fig. 8(b); the minimum mesh size at the weld joint was 5 mm × 1.75 mm × 0.8 mm (elements = 10,669, nodes = 18,030). There was a supporting platform under the side wall panel, and six clamps were applied only where the crossbeams were welded to side wal panel which was similar to clamps setting in Fig. 13.

Fig. 8.

Meshing model of small crossbeam: (a) fine mesh model, (b) coarse mesh model.

Fig. 13.

Clamping locations.

Combining two mesh division strategies, two simulation methods, and various number of segments, nine schemes were designed to compare the computation efficiency and accuracy, as shown in Table 6. Computer hardware configurations used for all simulations were 11th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-11700K processors.

Table 6.

Comparison of calculation accuracy and efficiency from various schemes.

| Scheme number | Model + Method | Computation time/h | Computation time ratio/% | Residual stress/MPa | Residual deformation/mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fine mesh + TEPM | 49.50 | 100 | 537.09 | 0.26 |

| 2 | Fine mesh + TCCM (one segment) | 5.57 | 11.25 | 518.57 | 0.13 |

| 3 | Fine mesh + TCCM (two segments) | 7.22 | 14.59 | 555.43 | 0.17 |

| 4 | Fine mesh + TCCM (four segments) | 10.63 | 21.47 | 533.20 | 0.21 |

| 5 | Fine mesh + TCCM (ten segments) | 16.48 | 33.29 | 516.97 | 0.24 |

| 6 | Coarse mesh + TCCM (one segment) | 0.13 | 0.26 | 479.49 | 0.12 |

| 7 | Coarse mesh + TCCM (two segments) | 0.99 | 2.00 | 499.78 | 0.16 |

| 8 | Coarse mesh + TCCM (four segments) | 2.96 | 5.97 | 504.65 | 0.19 |

| 9 | Coarse mesh + TCCM (ten segments) | 5.35 | 10.80 | 497.25 | 0.22 |

As shown in Table 6, compared with all calculation results of Scheme one, the calculation time of Scheme six was the least, the residual stress result of Scheme four was more accurate, and the welding deformation result of Scheme five was more accurate. However, considering all factors, the calculation time of Scheme eight was relatively less, and the residual stress and welding deformation were closer to the calculation result of the TEPM under fine mesh (Scheme one).

Fig. 9 shows the deformation distribution of L1 at the edge of the side-wall panel. The number of segments with the TCCM had a greater impact on the deformation. Higher number of segments resulted in higher accuracy of predicted deformation. When 4 or 8 segments were used, the entire deformation trend was clearly reflected. When divided into the same number of segments, the calculation results for coarse and fine mesh models showed small differences, showing that the use of a coarser mesh can also yield better calculation results of welding deformation.

Fig. 9.

Deformation distribution.

Fig. 10 shows the longitudinal stress distribution on the upper surface of the small crossbeam along the vertical weld direction. In the TCCM, the number of segments had a smaller effect on the residual stress. The residual stress distribution of various schemes was almost the same, but the residual stress of the fine mesh schemes was closer to the calculation results of the TEPM (Scheme one).

Fig. 10.

Longitudinal stress distribution.

Table 6, Fig. 9, Fig. 10 show that the results of welding deformation and residual stress with high calculation accuracy and efficiency were be obtained using the TCCM when the optimal number of sections and mesh divisions were selected. To obtain high-precision welding deformation, the coarse mesh model was suitable, and the number of segments was maximum. To obtain high-precision residual stress, the fine mesh model was suitable and the number of segments was decreased appropriately. Considering calculation accuracy and efficiency, Scheme eight was selected for welding simulation of a small crossbeam; that is, the 640 mm long weld was divided into four segments, and the TCCM was adopted. Similarly, the large crossbeam, above or under the window on side-wall module (length = 2964 mm), was divided into 16 segments to ensure calculation accuracy and efficiency.

5. Laser welding simulation introduction

5.1. Structural composition

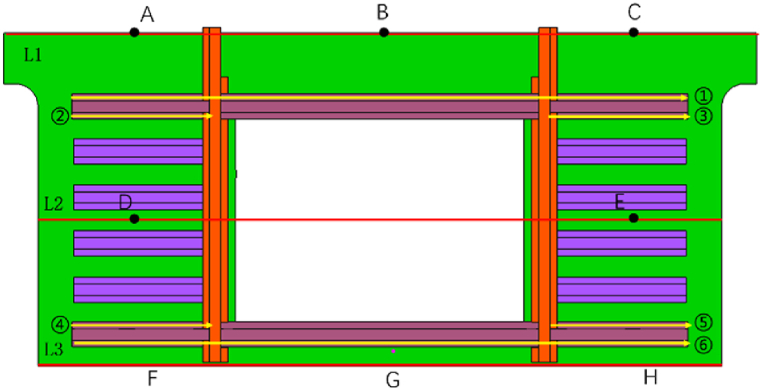

A stainless steel side-wall module mainly comprises one exterior wall panel, eight small crossbeams (thickness = 0.8 mm), two large crossbeams (thickness = 1.5 mm), and two longitudinal beams. In this study, other welding types were not considered, and only laser welding parts were simulated, as shown in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Geometric model of side-wall.

5.2. Welding process

The laser welding process of the side-wall module comprised two steps. In the first step, the welding between the exterior wall panel and eight small crossbeams was simulated, and in the second step, the welding between two large crossbeams (above and under the window) and the exterior wall panel was completed.

-

(1)

Simulated welding of eight small crossbeams

There were 16 laser welds on eight small crossbeams with a total weld length of 10,240 mm. The whole model was meshed with a hexahedral solid mesh (elements 188,616, nodes 317,805). The welding sequence is shown in Fig. 12. Eight small crossbeams were welded from the middle to both sides, and two welding guns were used simultaneously on both sides; the welding clamping conditions are shown in Fig. 13.

-

(2)

Welding simulation of the global side-wall module

Fig. 12.

Welding sequence.

After welding the eight small crossbeams, two large crossbeams began to be welded from top to bottom and from left to right in the welding direction; the welding sequence is shown in Fig. 14, and the welding clamping conditions are shown in Fig. 15.

Fig. 14.

Welding sequence.

Fig. 15.

Clamping conditions.

There were a total of 22 laser welds on the whole side-wall module, with total length of 18,188 mm, and a total of 267,444 elements and 435,945 nodes, as shown in Fig. 16(a–c).

Fig. 16.

FEM model of side-wall: (a) global mesh model, (b) small crossbeam (0.8 mm), (c) large crossbeam (1.5 mm).

6. Laser welding simulation analysis

6.1. Simulation of eight small crossbeams

After the first step of welding eight small crossbeams, the welding deformation and residual stress of the side-wall modules were as shown in Fig. 17, Fig. 18. The welding sequence was from the middle to both sides. Therefore, the welding deformations were symmetrical and the maximum deformation (2.51 mm) occurred mainly at the lower edge of the side-wall. Residual stresses were mainly concentrated in the weld area and their vicinity, and they decreased with increasing distance from the weld. Stress concentration occurred at both the starting and stopping points of welding. This phenomenon was attributed to the high fluctuation of temperature values in the area near the weld, where the maximum temperature can even exceed the boiling point of the material. After the heat source passed through, the large temperature value in the weld zone decreased significantly, which resulted in an unstable change field in the region. The eight small crossbeams were firmly controlled by the clamps and could not be moved to adjust the shrinkage. Thus, stress concentration areas were caused at the weld joints with a maximum value of 460.9 MPa.

Fig. 17.

Residual deformation.

Fig. 18.

Residual stress.

6.2. Simulation of global side-wall module

Based on the discussion in section 6.1, two large crossbeams were added for laser welding simulation and welding deformation results, as shown in Fig. 20.

Fig. 20.

Residual stress.

Fig. 19(a) shows welding deformation at 64 s after all small crossbeams were welded; the maximum deformation was only 0.36 mm, which was attributed to the setting of the clamping conditions for limiting the movement of the side-wall. Fig. 19(b) shows welding deformation at 176 s after large crossbeams welding; the maximum deformation was 1.91 mm, which was located in the lower right part of the exterior wall panel. Fig. 19(c) shows the final welding deformation (after cooling to room temperature [20 °C]); the deformation was 1.26 mm, which was located in the middle of the left side of the side-wall.

Fig. 19.

Welding deformation at different times: (a) 64 s, (b) 176 s, and (c) 500 s.

Fig. 20 shows the residual stress for all completed weld simulations. The high stress region was concentrated in a narrow area near the weld, where the stress gradient was extremely high, and the stress value decreased sharply as the distance from the weld increased; the maximum residual stress was 462.15 MPa. Due to the characteristics of the weld segments heated by the TCCM, the distribution of residual stresses at the weld segments was discontinuous, and it had the minimal effect on the global stress distribution.

6.3. Results analysis

The maximum welding deformation of the eight small crossbeams was 2.51 mm; the maximum deformation was only 1.26 mm after the upper and lower large crossbeams were added during welding, indicating that the welding of large crossbeams increased the stiffness of the side-wall. To enable more convenient observation of the difference of welding deformation before and after adding the large crossbeams, results of three deformation paths (L1-L3 in Fig. 14)were considered (Fig. 21).

Fig. 21.

Deformation of different paths: (a)–(c) paths L1-L3, respectively.

Fig. 21(a) shows that the deformation on path L1 increased after adding two large crossbeams, with the maximum deformation being 0.36 mm. This was mainly because transverse shrinkage was produced by the long weld of the large crossbeam, which caused point A to deform from 0.11 mm to 0.17 mm, point B to deform from 0.15 mm to 0.26 mm, and point C to deform from 0.06 mm to 0.28 mm.

Fig. 21(b) shows that the deformation on path L2 also increased after adding two large crossbeams, making point D deform from 0.92 mm to 1.23 mm and point E to deform from 0.93 mm to 1.08 mm. Exterior wall deformation tended to become asymmetric, that is, deformation in the left side was greater than that on the right side, which was attributed to the welding sequence from left to right side, thus producing an asymmetric deformation.

Fig. 21(c) shows that the global deformation of path L3 decreased significantly after adding two large crossbeams, resulting in point F to deform from 2.50 mm to 0.52 mm, point G to deform from 0.05 mm to 0.79 mm, and point H to deform from 2.49 mm to 0.93 mm. The large crossbeam under the window and two longitudinal beams between the windows strengthened the stiffness of the lower side-wall, ensuring that this location does not deform during welding, and thereby decreasing deformation.

7. Conclusion

For laser welding of large-scale assembly modules of stainless steel side-walls, the TCCM is a cost efficient and feasible method for predicting residual stress and welding deformation.

-

(1)

A combined heat source of Gaussian surface heat source + cylindrical volume heat source was established, and the obtained molten pool shape and experimental results were in accordance with the molten pool boundary criterion; the errors were all <10%, verifying the accuracy of the heat source model.

-

(2)

Based the TCCM, the simulation model should be as fine mesh as possible for addressing the issue of residual stress, while it should have the maximum number of weld segments with coarse mesh for addressing the issue of welding deformation; this can ensure highly accurate and efficient calculation.

-

(3)

In the welding simulation of eight small crossbeams of the side-wall, the welding sequence was from the middle to both sides and the maximum deformation value was 2.51 mm, which occurred in the edge of the side-wall under the window, showing a symmetrical distribution.

-

(4)

When two large crossbeams were added to the side-wall module, the residual stress was mainly concentrated in the narrow region near the weld, and the maximum stress value was 462.15 MPa, which decreased considerably with increasing distance from the weld. The maximum deformation (1.26 mm) appeared in the middle position of the left side-wall, indicating that adding large crossbeams can change the stiffness to reduce deformation.

-

(5)

For the large 3D solid structure of a side-wall with many welds and many boundary conditions, TCCM reduces the calculation time, improves the calculation accuracy, and makes the calculation converge quickly. It is thus a cost efficient and suitable welding simulation method.

-

(6)

Based on simulation results, the optimization of welding process, such as welding parameters, clamping conditions, and welding sequences, need to be further investigated.

Author contribution statement

Yana Li: Conceived and designed the study experiments.

Yangfan Wang: Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Xingfu Yin: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Zeyang Zhang: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

Yana Li was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China [52075066], Liaoning Provincial Department of Education Project from China [LJKZ0497].

Data availability statement

The data that has been used is confidential.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Zhan Xiaohong, Zhao Yanqiu, Chen Shuai, Kang Yue. Research progress on double laser-beam bilateral synchronous welding of T-joints for light alloy. Aeronaut. Manuf. Technol. 2020;63(11):20–31. doi: 10.16080/j.issn1671-833x.2020.11.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang Hui, Wang Jiandong, Li Liqun, Ma Ninshu. Prediction of laser welding induced deformation thin sheets by efficient numerical modeling. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2016;227:117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2015.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim Jae Woong, Jang Beom Seon, Kim Yong Tai, Chun Kwang San. A study on an efficient prediction of welding deformation for T-joint laser welding of sandwich panel. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2014;6:245–256. doi: 10.2478/ijnaoe-2013-0176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagy M., Behulova M. 2017. Design of Welding Parameters for Laser Welding of Thin-Walled Stainless Steel Tubes Using Numerical Simulation. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Youfa. Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics; 2020. Study on Laser Welding Deformation and Stresses of Al-Li Alloy Large Thin-Wall Structure Based on Shell Element. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qi Tang, Chen Peng, Chen Jingqing, Liang Yong, Liu Zan. Numerical simulation of welding deformation in laser hybrid welding based on SYSWELD. Trans. China Weld. Inst. 2019;40(3):32–36. doi: 10.12073/j.hjxb.2019400067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song Kunlin, Zhan Xuhe, Xu Liang, Yang Haifeng, Cui Hui. Numerical simulation on laser hybrid welding deformation of side walls of train body based on inherent strain method. Weld. Join. 2021;(12):42–47. doi: 10.12073/j.hj.20210621001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong Xu, Xing Li, Li Xiaoyan, Zhang Yingbin. Research on the calculation of welding distortion based on welding shrinkage method. Ship Build. Technol. 2015;(2):85–91. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3878.2015.02.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Chong. Kunming University of Science and Technology; 2021. Numerical Simulation of Volute-Seat Ring Welding Based on Similarity Theory. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Zhilian, Xiao Yunfeng, Wang Zhonghui. Numerical simulation of assembling deformation in large welded component based on local-global mapping Method. Weld. Technol. 2018;47(2):81–85. doi: 10.13846/j.cnki.cn12-1070/tg.2018.02.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang Yong. Huazhong University of Science and Technology; 2017. Finite Element Analysis of Welding Deformation and Residual Stress for Large Scale Structure Based on Local-Global Mapping. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao Yunfeng, Ding Jieqiong, Liang Lianjie, Li Xingfei, Wei Yanhong. Finite element analysis of welding deformation and residual stress in large structure of railway vehicles. Weld. Join. 2019;(11):13–19. doi: 10.12073/j.hj.20190515002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang Yuanbin, Li Liancheng, Zhang Liping, Lu Yongneng, Shi Jun. Influence of heat resource loading modes on deformation and stress of large parts. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2017;17(14) doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-1815.2017.14.008. 54-58. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Zhen, Wang Fazhan, An Gaoling, Liu Taiping, Li Zhen, Zheng Jianxiao. Research of segmented moving combined welding heat source using thermal cycle curve as control variables. Hot Work. Technol. 2015;44(11):211–216. doi: 10.14158/j.cnki.1001-3814.2015.11.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Zhen, Wang FaZhan, An Gaoling, Liu Taiping, Ding Pugang. Analysis of welding residual deformation for excavator boom by using thermal elastic-plastic finite element method. Mech. Sci. Technol. Aerosp. Eng. 2016;35(5):696–700. doi: 10.13433/j.cnki.1003-8728.2016.0507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai Wenhua, Song Yuntao, Xin Jijun, Fang Chao, Jing Wei, Wu Jiefeng. Numerical simulation of the ITER BTCC prototype case enclosure welding. Fusion Eng. Des. 2020;(154) doi: 10.1016/j.fusengdes.2020.111538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Su, Zhao Haiyan, Wang Yu, Zhang Xiaohong. A new heat source model in numerical simulation of high energy beam welding. Trans. China Weld. Inst. 2004;(1) doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0253-360X.2004.01.024. 91-94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J.W., Jang B.S., Kim Y.T., et al. A study on an efficient prediction of welding deformation for T-joint laser welding of sandwich panel PART I : proposal of a heat source model. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2013;5(3):348–363. doi: 10.2478/ijnaoe-2013-0138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bendaoud I., Matte S., Cicala E., et al. The numerical simulation of heat transfer during a hybrid laser–MIG welding using equivalent heat source approach. Opt Laser. Technol. 2014;56:334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.optlastec.2013.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubiak M., Piekarska W., Stano S. Modelling of laser beam heat source based on experimental research of Yb:YAG laser power distribution. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2015;83:679–689. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2014.12.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Xin, Yang Zhibin. Eetablishment and verification of heat source model of double-sided laser beam welding for T-joint. Electr. Weld. Mach. 2018;48(7):25–30. doi: 10.7512/j.issn.1001-2303.2018.07.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Xiangyang, Su Hao, Sun Yan, Chen Ji, Wu Chuansong. Thermal-mechanical coupled numerical analysis of laser+GMAW hybrid heat source welding process. Trans. China Weld. Inst. 2021;42(1):91–96. doi: 10.12073/j.hjxb.20200708001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han Xiaohui, Chen Jing, Kan Ying, Chen Huaining, Zhao Ruirong. Heat source model for non-penetration laser lap welding of stainless steel sheets. Chin. J. Lasers. 2017;44(5):89–96. doi: 10.3788/CJL201744.0502002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tian Man. Huazhong University of Science and Technology; 2015. Study on Laser Welding Process of Railway Dedicated Stainless Steel. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Yunhao. North China Institute of Aerospace Engineering; 2019. Welding Process Research on the Large Robot Structure with Complex Welds. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.