Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

What is known about health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) in women with idiopathic primary ovarian insufficiency (POI)?

SUMMARY ANSWER

Women with POI have a range of unmet psychosocial needs relating to three interrelated themes: ‘diagnostic odyssey’, ‘isolation and stigma’ and impaired ‘ego integrity’.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

Prior studies have reported increased depressive symptoms, diminished sexual function and altered body image/self-concept in women with POI.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

A systematic scoping review (11 databases) on HR-QoL in POI including published quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies as well as unpublished gray literature (i.e. unpublished dissertations) through June, 2021.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

After removing duplicates, 1244 articles underwent title and abstract review by independent reviewers. The remaining 72 relevant articles underwent dual full text review to determine inclusion criteria yielding 24 articles (100% concordance) for data extraction. Findings were summarized in tables by methodology and recurrent HR-QoL themes/sub-themes were mapped to define key aspects of HR-QoL in POI. Promoters of active coping were charted at the individual, interpersonal and healthcare system levels. Targets for tailored interventions supporting active coping and improved HR-QoL were mapped to the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB).

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

Three interrelated themes affecting HR-QoL in POI emerged from the data synthesis. First, the theme ‘diagnostic odyssey’ comprised sub-themes of uncertainty, lack of control, knowledge gaps, discontinuous care and negative clinical interactions. The second theme ‘isolation and stigma’ included sub-themes of guilt, shame, concealment, feeling labeled as infertile, lack of social support and unsympathetic clinicians. The third theme, impaired ‘ego integrity’ captured sub-themes of decreased sexual function, altered body image, psychological vulnerability and catastrophizing. Targets promoting active coping at the individual (n = 2), interpersonal (n = 1) and healthcare system (n = 1) levels were mapped to the TPB to inform development of tailored interventions supporting active coping and improved HR-QoL in POI (i.e. narrative intervention, co-creating patient-facing materials, peer-to-peer support and provider resources).

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

No studies using a POI-specific HR-QoL instrument were identified. No interventional studies aimed at improving HR-QoL in POI were identified. Only articles published in English were included in the study.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

Women with POI frequently have impaired HR-QoL related to the life-altering infertility diagnosis. The range of unmet psychosocial needs may be relevant for informing interventions for other populations with infertility.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development ‘Massachusetts General Hospital—Harvard Center for Reproductive Medicine’ (1 P50 HD104224-01 NICHD). The authors have no conflicts to declare.

REGISTRATION NUMBER

N/A.

Keywords: primary ovarian insufficiency, premature menopause, health-related quality of life, psychological distress, coping

Introduction

Primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) is a complicated syndrome characterized by loss of ovarian function by age 40 and has a variable clinical course that includes early onset of menopausal symptoms and infertility. In the literature, POI has been variably termed premature ovarian failure, premature ovarian insufficiency, premature menopause, premature ovarian dysfunction, poor ovarian response and/or diminished ovarian reserve (Welt, 2008). Data suggest that POI affects approximately 1% of women before the age of 40 and roughly 0.1% before 30 years (Coulam et al., 1986). Autoimmune (e.g. autoimmune oophoritis), iatrogenic (e.g. post-chemotherapy, radiotherapy) and genetic factors have been described—including chromosomal abnormalities (e.g. Turner syndrome) and gene variants identified using next generation sequencing (Franca and Mendonca, 2020). However, in most cases, the etiology remains poorly defined, likely related to rare gene variants yet to be discovered or not routinely examined.

In addition to difficulty understanding the cause of POI, patients experience adverse effects from the disorder itself that are challenging to quantify. The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) has developed a guideline to manage the symptoms and complications of POI (European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Guideline Group on POI et al., 2016). ESHRE guidelines recommend treatment to protect bone health and recommend psychosocial support for women diagnosed with POI (European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Guideline Group on POI et al., 2016). Symptom management and mitigating sequelae is also critical as POI symptoms are caused by low estrogen levels and include hot flashes, night sweats, poor sleep, amenorrhea, sexual dysfunction, sub-/infertility and a range of physical effects including impaired bone health and increased risk of cardiovascular disease as well as diminished quality of life (Li et al., 2020).

Measures of health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) have been constructed to assess the impact of disease (and treatment) on an individual across physical, psychological and social dimensions. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 studies on women with POI found low to medium effect size on HR-QoL compared to women with normal ovarian function (Li et al., 2020). Importantly however, many validated HR-QoL measures (i.e. SF-36, World Health Organization Quality of Life—Brief (WHO-QOL Bref)) are generic instruments and it remains unclear if such instruments accurately capture disease-specific constructs that women with POI experience. For example, generic HR-QoL instruments may not appropriately assess menopausal symptoms, sexual dysfunction, altered body image, self-esteem and concerns related to infertility that have been reported in POI. Thus, while evidence suggests women with POI experience decreased HR-QoL, a comprehensive, holistic understanding of the challenges faced by women is lacking. The knowledge gap limits the development of targeted interventions that respond to the priority needs of women with POI.

We aimed to conduct a systematic scoping review to synthesize findings from quantitative studies, qualitative inquiry, mixed-methods studies and unpublished gray literature on HR-QoL in POI. Subsequently, we identified factors promoting active coping within a systems perspective (i.e. individual, interpersonal and healthcare system levels). We then mapped identified targets onto the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991) to inform the development of theory-informed interventions to improve HR-QoL in women with POI.

Materials and methods

The project involved three sequential components. First, we performed a systematic scoping review of the literature to identify and synthesize existing data on HR-QoL in women with POI. Second, we identified factors supporting active coping at the individual, interpersonal and healthcare system levels. Finally, we mapped results onto the TPB to identify targets for interventions.

Systematic scoping review

We employed Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) framework that involves five steps.

Identifying the research question: The scoping review process was guided by a single primary question ‘what is known about HR-QoL in persons with primary ovarian insufficiency?’

Identifying the relevant literature: We performed a systematic, structured literature search of articles in English (published and grey literature) in 11 electronic databases (Medline, PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science Core Collection, The Cochrane Library, Joanna Briggs Institute EBP Database, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, TRIP and Greylit.org). Appropriate search terms for each respective database were used related to POI (i.e. primary ovarian insufficiency, premature menopause, premature ovarian insufficiency, primary ovarian failure, premature ovarian failure, diminished ovarian reserve, poor ovarian response) and HR-QoL (quality of life, health-related quality of life, well-being, health outcome). Database search results were exported into Endnote™ (V20, Clarivate, Boston, MA, USA). Additional articles were identified using a ‘snowball’ technique to review the reference lists of included articles and the publications of frequently cited authors. Articles identified using the ‘snowball’ approach were added to the list of articles identified in the database search.

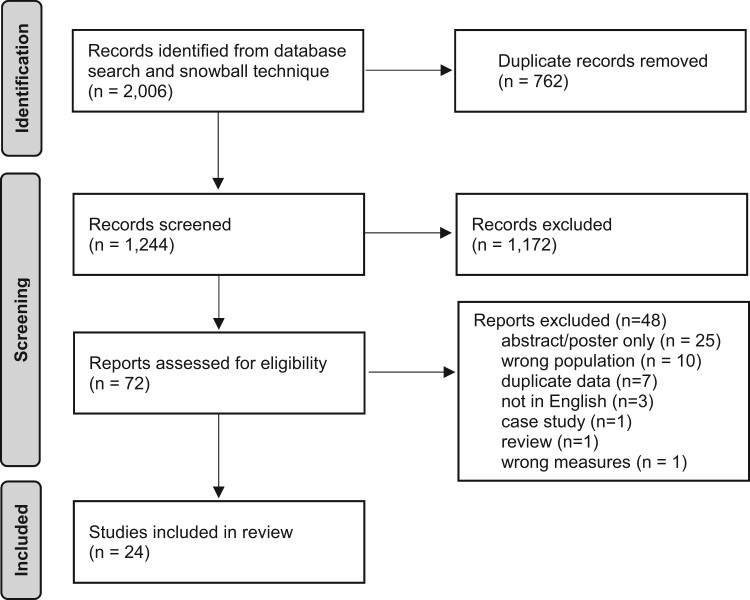

Selecting the literature: Literature search results were imported into Covidence online systematic review software (www.covidence.org, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia). After duplicates (n = 762) were removed, two researchers (I.R.M. and A.A.D.) independently reviewed titles and abstracts of the remaining 1244 articles for relevancy and inclusion criteria. Included articles were primary research reports including qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies of HR-QoL in women with idiopathic POI. Studies focusing exclusively on iatrogenic (e.g. post-chemotherapy) or syndromic (e.g. Turner syndrome) forms were excluded as were case reports, review articles, opinion pieces and articles not published in English. Discrepancies were discussed (29/1244, 2%) until consensus was reached regarding relevancy and inclusion. Subsequently, 72 potentially relevant articles were independently reviewed by two researchers (I.R.M. and A.A.D.) to determine relevancy and inclusion/exclusion criteria. No discrepancies were identified between independent reviewers. In total, 24 articles were included for data extraction and analysis. The screening process is summarized in a PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Scoping review PRISMA diagram.

Charting the data

Data were extracted from articles including study design, inclusion/exclusion criteria, sample size, validated instruments/tools and study findings. Risk of bias was not conducted due to methodological variability of included studies (i.e. only one randomized controlled trial).

Collating, summarizing and reporting results

Extracted data from the 24 articles were organized by study methodology (quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods). Findings were reviewed and analyzed using an iterative process to identify thematic elements (Saldaña, 2021). Briefly, investigators discussed and organized study findings into relevant categorical themes and sub-themes (i.e. dimensions of the categorical theme). Thematic categories were then added to the data extraction summary tables. Additionally, promoters/barriers were organized and grouped according to theme and categorized using a systems perspective (i.e. individual factors, interpersonal influences or healthcare system factors).

Theoretical framework

We used the TPB as a guiding theoretical framework for mapping targets for intervention (Ajzen, 1991). Briefly, the TPB applies to an individual’s behavioral intention. The TPB posits that ‘intention’ precedes action and behavior. The TPB considers that intention is shaped by attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control—all of which are shaped by prior experience (i.e. behavior beliefs, normative beliefs and control beliefs, respectively). ‘Attitudes’ reflect an individual’s perceptions of a behavior being positive/negative. ‘Subjective norms’ refer to expectations of family, friends, healthcare providers, etc. (i.e. interpersonal mediating factors). ‘Perceived behavioral control’ relates to an individual’s perceived self-efficacy and agency. An active coping response could be considered an essential component for mitigating factors contributing to impaired HR-QoL in women with POI. Accordingly, we conceptualized behavior in the TPB as an active coping response to receiving a POI diagnosis (facilitating identity integration).

Results

The systematic database search and review of article reference lists identified a total of 2006 articles (Fig. 1). After 762 duplicates were removed, 1244 articles underwent initial title and abstract screening. The remaining 72 articles underwent independent full text review for inclusion criteria and relevance yielding 24 included studies (quantitative (n = 17), qualitative (n = 4), mixed methods (n = 3), 100% concordance between independent reviewers) for data extraction and analysis.

Recurring themes in study findings

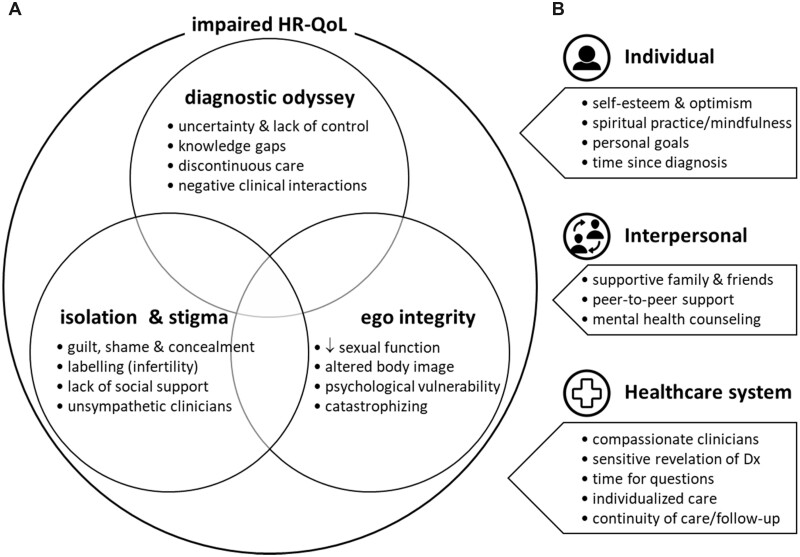

After collating study findings, thematic analysis identified several major, recurring themes (Fig. 2a). The overarching theme was ‘impaired HR-QoL’—referring to the impact of health status and/or healthcare on physical, mental, social and emotional well-being. Within ‘impaired HR-QoL’, three distinct, interacting themes were identified relating to the experiences of women with POI. The ‘diagnostic odyssey’ theme refers to the often-extended journey women experienced in receiving a POI diagnosis. The theme includes several dimensions including feelings of uncertainty, perceived lack of control, knowledge gaps (i.e. not understanding what was wrong), discontinuity of care (i.e. seeing multiple different providers and specialists) and negative clinical interactions with providers. The ‘isolation & stigma’ theme relates to the social and emotional responses women experienced following diagnosis. Dimensions include feelings of guilt and shame (from peers and providers) resulting in efforts to conceal the diagnosis, feeling labeled (i.e. infertile), lack of social support and perceptions of providers being unsympathetic to their situation. The ‘ego integrity’ theme refers to the impact the diagnosis and symptoms had on their sense of self and psyche. Dimensions of the theme include decreased sexual function, altered body image, feeling psychologically vulnerable/fragile and the tendency to ‘catastrophize’ experiences (i.e. any event will be deleterious).

Figure 2.

Themes and dimensions related to impaired health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) in women with primary ovarian insufficiency (POI). Synthesizing the results of the scoping review identified potential targets for interventions to improve health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) in women with primary ovarian insufficiency (POI). (A) Three interacting themes (bold text in overlapping circles: diagnostic odyssey, isolation and stigma, ego integrity) contributed to impaired HR-QoL in women with POI (i.e. anxiety, depression, psychological distress, diminished health status). Dimensions for each theme are depicted by bullets. (B) Several mitigating factors were identified from the literature and are categorized at the individual, interpersonal and healthcare system levels. Protective factors are noted by bulleted points for each respective level. Dx, diagnosis.

Findings from quantitative studies

In total, 17 quantitative research studies were included (Table I). Quantitative study findings most often related to the themes of ‘impaired HR-QoL’ and ‘ego integrity’—noted in 10/17 (59%) articles for each theme. Studies used several validated measures to assess anxiety, depression and psychological distress including the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) Structured Clinical Interview (SCID). Several studies noted the high psychological burden associated with a POI diagnosis (Liao et al., 2000; Van Der Stege et al., 2008; Davis et al., 2010; Mann et al., 2012). Studies report that between 64% and 70% of women with POI have been diagnosed with a DSM-IV axis-1 disorder in their lifetime, including major (49–55%) and minor (11–13%) depression (Schmidt et al., 2011; Guerrieri et al., 2014). The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) was a validated measure used to assess sexual function. Notably, 5/17 (29%) studies reported impaired sexual function in POI that was distressful or bothersome to women (Kalantaridou et al., 2008; Van Der Stege et al., 2008; Gibson-Helm et al., 2014; Yela et al., 2018; Javadpour et al., 2021). Yela et al. (2018) found sexual satisfaction was correlated with all four domains of HR-QoL (physical, psychological, social relationships and environment)—suggesting global effects on wellbeing. Notably, the ‘diagnostic odyssey’ and ‘isolation/stigma’ themes were noted less frequently in the quantitative studies (5/17 (29%) and 4/17 (24%), respectively). While few validated scales exist related to the construct of ‘diagnostic odyssey’, two groups employed the Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale to assess uncertainty and lack of control (dimensions of the theme) (Davis et al., 2010; Rivers, 2014; Driscoll et al., 2016).

Table I.

Summary of quantitative studies on health-related quality of life in POI (n = 17).

| Study information | Measures | Summary findings |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; COPE, Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; fourth edition Dx, diagnosis; HR-QoL, health-related quality of life; POI, primary ovarian insufficiency; QoL, quality of life; WHOQoL-BREF, World Health Organization Quality of Life—Brief.

Findings from qualitative and mixed-methods studies

Four qualitative and three mixed-methods studies were included for data extraction and subsequent thematic analysis (Table II). The ‘isolation and stigma’ and ‘diagnostic odyssey’ themes were the most common (both 5/7, 71%) among qualitative and mixed-methods studies. Feelings of isolation and stigma, including the stigma associated with the label of ‘infertile’, were frequently reported by women with POI. Similarly, feelings of guilt and shame or concealment of their diagnosis were common (Halliday and Boughton, 2009; Singer et al., 2011; Golezar et al., 2020). Women reported that their emotional responses were magnified by interactions with providers they perceived as unsympathetic (Boughton and Halliday, 2008; Halliday and Boughton, 2009) as well as lack of adequate social support (Halliday and Boughton, 2009; Vemuri et al., 2019). Several studies reported women’s experiences of negative clinical interactions during clinical encounters (i.e. feeling their symptoms were dismissed/delegitimized because of their young age/non-specific complaints or not receiving enough information about POI from providers) (Boughton and Halliday, 2008; Halliday and Boughton, 2009; Singer et al., 2011; Johnston-Ataata et al., 2020). Such experiences left many women with knowledge gaps about their diagnosis or treatment plans and inadequate support in weighing risks/benefits of hormone therapy (Groff et al., 2005; Halliday and Boughton, 2009; Singer et al., 2011; Johnston-Ataata et al., 2020). Boughton and Halliday (2008) described patients’ feelings of undergoing pregnancy tests during the diagnostic process (i.e. evaluating amenorrhea) as a source of both hope and despair—when they ultimately were diagnosed with POI. Singer et al. (2011) reported that women with POI may speculate that stress or preceding life events caused POI. For some women, fear of the risks associated with hormone therapy and lack of clinical support contributed to non-adherence and treatment cessation (Johnston-Ataata et al., 2020). The ‘ego integrity’ theme was prevalent (4/7, 57%) among qualitative and mixed-methods studies. Indeed, several studies found women described altered body image resulting from the POI diagnosis (i.e. felt older, less confident, less feminine) (Groff et al., 2005; Singer et al., 2011; Golezar et al., 2020).

Table II.

Summary of qualitative and mixed-methods studies on health-related quality of life in POI (n = 7).

| Study | Type and methods | Summary findings |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

Dx, diagnosis; POI, primary ovarian insufficiency; QoL, quality of life.

Promoters of effective coping with a POI diagnosis

Among the 24 included studies, many identified promoters/barriers to an active coping response following a POI diagnosis. As the factors were heterogeneous, we clustered them using an ecological (systems) perspective by categorizing factors at the level of the individual, interpersonal level or healthcare system (Fig. 2b). The three levels represent potential targets for intervention to support active coping and help improve HR-QoL in women with POI.

Among quantitative studies, four studies identified mental health counseling as a critical component in managing POI given the high psychological burden (Liao et al., 2000; Davis et al., 2010; Guerrieri et al., 2014; Luiro et al., 2019). Similarly, several studies highlight the importance of social/emotional support for reducing feelings of isolation following diagnosis (Liao et al., 2000; Orshan et al., 2009; Davis et al., 2010; Driscoll et al., 2016). Orshan et al. (2009) found a positive association between perceived social support and self-esteem. In line with these findings, Yela et al. (2018) identified improving social relationships as a potential target for interventions aimed at improving HR-QoL. Two studies reported that women with POI scored poorly on measures of self-esteem (Orshan et al., 2009; Guerrieri et al., 2014). However, women with POI appear to have different coping trajectories following diagnosis. Higher baseline levels of resilience (e.g. active coping, acceptance, purpose in life, optimism) is positively correlated with well-being, and negatively correlated with distress, at 12 months (Rivers, 2014; Driscoll et al., 2016). Conversely, women with high baseline vulnerability measures (e.g. anxiety, depression, emotionality, interpersonal sensitivity, pessimism) had greater distress and lower well-being at 12 months (Rivers, 2014; Driscoll et al., 2016). Additional factors that may support an effective coping response and adaptation to living with POI include spiritual practice/mindfulness (Ventura et al., 2007; Allshouse et al., 2015), focusing on personal goals (Ventura et al., 2007; Rivers, 2014; Driscoll et al., 2016), and time since diagnosis (Liao et al., 2000). In summary, the quantitative studies point to factors at the individual and interpersonal levels (Fig. 2).

Notably, qualitative and mixed-methods studies also identified many of the same promoters of coping (Fig. 2) among women with POI. Factors including mental health counseling (Groff et al., 2005; Singer et al., 2011), supportive family/friends (Vemuri et al., 2019), focusing on personal goals (Vemuri et al., 2019) and spiritual practice/mindfulness (Groff et al., 2005) were found to support active coping—thereby lending further support for the quantitative findings. Notably, qualitative inquiry (e.g. interviews, analysis of discussion board messages) identified additional factors at the interpersonal and healthcare system levels. Emergent constructs include peer-to-peer support (Groff et al., 2005; Halliday and Boughton, 2009), compassionate clinicians (Groff et al., 2005; Vemuri et al., 2019), a sensitive revelation of POI diagnosis (Groff et al., 2005), individualized care (Vemuri et al., 2019; Johnston-Ataata et al., 2020), adequate time for patient education/questions (Groff et al., 2005) and continuity of care with regular follow-up (Singer et al., 2011).

Discussion

Herein, we report findings from a systematic scoping review of the literature on HR-QoL in women with idiopathic POI. Within the broad umbrella concept of HR-QoL, three key interrelated themes emerged from the quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies: ‘diagnostic odyssey’, ‘isolation and stigma’ and impaired ‘ego integrity’. First, the ‘diagnostic odyssey’ theme relates to an extended journey to reach a clinical diagnosis. The diagnostic odyssey is well documented among patients with rare, poorly understood conditions (Bogart et al., 2022). Women with POI frequently report feelings of uncertainty, perceived lack of control, knowledge gaps (i.e. not understanding their health condition) and negative clinical interactions with providers across multiple specialties (i.e. discontinuous care). Findings point to challenges in navigating a complex healthcare ecosystem to reach a diagnosis.

The second interrelated theme ‘isolation & stigma’ characterizes the emotional coping response of women after being diagnosed with POI. Women often feel labeled as infertile—contributing to guilt and shame. In parallel, negative (unsympathetic) clinical encounters and lack of social support can exacerbate the emotional response to the diagnosis. Many women respond by trying to conceal their diagnosis—an avoidant coping response that can amplify feelings of isolation. These observations point to a need for tailored, person-centered and holistic approaches to care that not only address infertility and hormone replacement, but also the psychosocial impact of receiving a life-altering POI diagnosis.

The third interrelated theme ‘ego integrity’ refers to the impact the diagnosis and symptoms have on an individual’s identity. The theme suggests that acquired POI-related changes like infertility, decreased sexual function and altered body image disrupt the continuity of one’s sense of self and threaten ego integrity (Adler et al., 2021). Given the personal and societal value placed on reproductive capacity, infertility is often accompanied by a loss of control and diminished self-worth (Greil, 1997). Individuals who are unable to incorporate the real (physical) and perceived (psychological) changes into their sense of self (i.e. identity integration) can suffer significantly impaired health and wellbeing (Mitchell et al., 2021).

It is plausible that the personal/societal value placed on reproductive capacity and the protective factor of focusing on personal goals may be linked. Namely, women who are more inclined to focus on personal goals may be less invested in their ability to bear children—and thus relatively insulated from the compromised HR-QoL associated with subfertility/infertility. Reviewing the existing literature we did not identify any clear, direct link between these concepts. However, Liao et al. (2000) noted that already having children was associated with greater life satisfaction—yet not lower rates of depression. Thus, it appears that that individual coping responses appear to be patient-specific and one should be cautious about making sweeping conclusions based on the available data.

It is worthwhile to note that although many women experience psychological distress following a POI diagnosis, other women adjust rather well—indicating variability in coping response to POI. Historically, models examining adaptation to health threats have been unidimensional with a ‘negative’ focus (i.e. psychological/emotional risk factors, maladaptive coping responses, negative psychosocial outcomes). More recent models embrace a 2-dimensional approach that also includes ‘positive’ factors like resilience, adaptive (active) coping and positive outcomes (Ryff and Singer, 1998). In one of the few longitudinal studies conducted in women with POI, Driscoll et al. (2016) applied a 2-dimensional model of risk and resilience to examine coping response to infertility. Using confirmatory factor analysis, investigators found that baseline vulnerability and resilience factors predicted distress and well-being respectively at 12 months. Notably, avoidant coping (i.e. refusing to acknowledge diagnosis-related stress) mediated the observed association between baseline vulnerability and distress at 12 months (Driscoll et al., 2016).

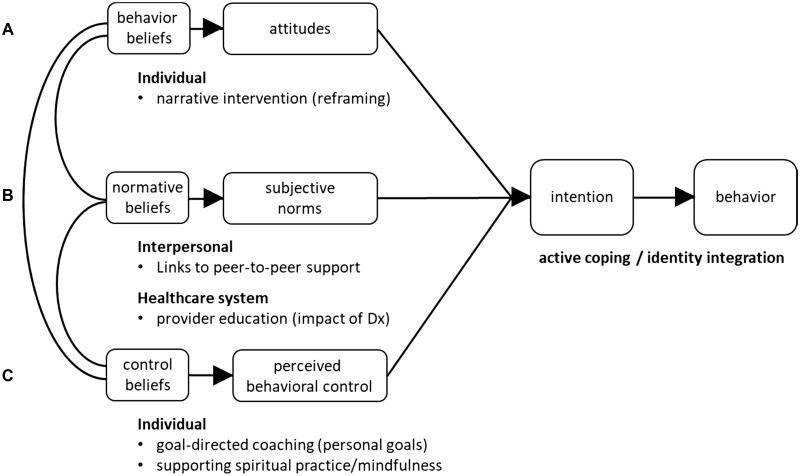

Our systematic scoping review did not identify any POI-specific measures of HR-QoL. Importantly, general HR-QoL instruments (e.g. SF-36, WHOQOL-Bref) often do not capture the salient constructs for particular conditions. Thus, general instruments may underestimate the impact of condition-specific symptoms and the degree to which wellbeing is impacted (Ware et al., 2016). Accordingly, future directions could include work to develop and validate a disease-specific POI HR-QoL measure or patient-reported outcome measure (PROM). Our synthesis of existing data in this scoping review could provide foundational insights for developing a POI-specific HR-QoL instrument and could inform the development of PROMs to inform a comprehensive, holistic approach to management of POI. Such disease-specific tools would be a useful addition as they would offer a reliable means to measure changes in response to hormonal and/or psychosocial interventions. We acknowledge that not all people born with ovaries identify as women. As such, additional future directions may include describing the experiences of individuals with POI across the continuum of gender identity. In addition, we did not identify any interventional studies that specifically address the psychosocial wellbeing of women with POI. Coping response (i.e. avoidant vs active) is a critical link between psychosocial traits (i.e. vulnerability, resilience) and outcomes (i.e. distress, wellbeing) (Driscoll et al., 2016). We used an ecological perspective to categorize factors promoting active coping at the level of the individual, interpersonal level or healthcare system. We considered that such targets could be the basis for theory-informed interventions (i.e. TPB) to support active coping and identity integration to foster wellbeing in women with POI (Fig. 3). Notably, a 2021 narrative review conducted to guide the development of models of care for POI identified six key themes: stakeholder engagement, supporting integrated care, evidence-based care, defined outcomes and evaluation, incorporating behavior change methodology and adaptability (Jones et al., 2020). Importantly, stakeholder (patient) engagement was considered central to all of the themes, indicating that there are opportunities to involve patients in the development of models of care and interventions.

Figure 3.

Targets for interventions supporting active coping mapped to the theory of planned behavior. To inform multilevel interventions to support identity integration and active coping (i.e. intention and behavior), we mapped targets from the individual, interpersonal and healthcare system levels to the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). (A) Factors relating to TPB beliefs/attitudes include narrative interventions to reframe the primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) diagnosis and support individuals in integrating the diagnosis into their identity. (B) Factors relating to TPB norms include connecting patients to peer-to-peer support to normalize experiences with other patients and decrease isolation. Educating providers on the psychosocial impact of the POI diagnosis could shift prevailing norms within the healthcare system and support more sensitive patient interactions. (C) Factors relating to perceived behavioral control include supporting taking active steps toward personal goals and reinforcing the importance of spiritual/religious practices and mindfulness. Dx, diagnosis.

At the individual level, narrative interventions (Adler et al., 2016; Mitchell et al., 2021) could help reframe the POI diagnosis and support women in integrating POI into their identity (TPB: behavior beliefs that shape attitudes). Similarly, a positive forward looking approach using goal-directed coaching and supporting spiritual practice/mindfulness could foster and reinforce an internal locus of control over their life (TPB: control beliefs that shape perceived behavioral control). At the interpersonal level, creating patient-facing materials with links to peer-to-peer support could help patients find others to help them normalize their experiences and pierce the veil of isolation and shame (TPB: normative beliefs that shape subjective norms). Peer-to-peer support has proven to be critical for overcoming similar emotional responses among rare disease patient populations (Dwyer et al., 2014). Moreover, a ‘design thinking’ (i.e. human centered design) approach has been posited for developing more comprehensive, integrated care for POI (Martin et al., 2017). We have previously shown that partnering with patients and using design thinking to co-create patient-facing materials produces high quality, lay language materials that are responsive to patient priorities (COST Action BM1105 et al., 2017; Dwyer et al., 2021). Work is currently underway to engage patients to co-create patient-facing materials for POI. At the healthcare system level, educating providers about the psychosocial aspects of POI and making patient-facing materials freely available online could shift the prevailing norms of providers (TPB normative beliefs that shape subjective norms) (Fig. 3).

Relative strengths of the scoping review include the comprehensive, systematic review of the literature with review by independent investigators (100% concordance) to extract findings from quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies. There are limitations to the scoping review. First, we identified a wide range of validated instruments that were used to study HR-QoL in women with POI. The lack of a validated, disease specific instrument limits our ability to understand the full scope of how POI affects HR-QoL. Second, we did not identify any interventional studies. Thus, the best approach to improving HR-QoL in POI remains unclear. Last, we only included publications in English. As such, it is possible that work published in other languages may add other insights into the experiences of women with POI.

In conclusion, the systematic scoping review found that receiving a POI diagnosis is a watershed moment in a woman’s life with significant implications for HR-QoL. We identified three interrelated themes highlighting unmet psychosocial needs of women with POI. The study findings identify targets for theory-informed interventions at the individual, interpersonal and healthcare system levels to support active coping and improve HR-QoL in women with POI. There are opportunities to include patients in designing interventions that respond to high-priority unmet patient needs. Targeted, person-centered interventions are needed to deliver comprehensive, high-quality care for women with POI.

Acknowledgements

We thank research librarian Ms Wanda Anderson for her assistance with the literature search.

Authors’ roles

I.R.M. made significant contributions to data collection, data curation, data validation, formal analysis, writing the original draft, reviewing/editing the manuscript and project administration. C.K.W. made significant contributions to data validation and reviewing/editing the manuscript. A.A.D. made significant contributions to conceptualization, methodology, data validation, formal analysis, creating visualizations, writing the original draft, reviewing/editing the manuscript, supervision, project administration and funding acquisition. All authors have read and approved the submitted manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development ‘Massachusetts General Hospital—Harvard Center for Reproductive Medicine’ (1 P50 HD104224-01 NICHD).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest or disclosures.

Contributor Information

Isabella R McDonald, William F. Connell School of Nursing, Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA, USA.

Corrine K Welt, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA; Massachusetts General Hospital-Harvard Center for Reproductive Medicine, Boston, MA, USA.

Andrew A Dwyer, William F. Connell School of Nursing, Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA, USA; Massachusetts General Hospital-Harvard Center for Reproductive Medicine, Boston, MA, USA.

Data Availability

No new data were generated or analyzed in support of this research.

References

- Adler JM, Lakmazaheri A, O’Brien E, Palmer A, Reid M, Tawes E. Identity integration in people with acquired disabilities: a qualitative study. J Pers 2021;89:84–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler JM, Lodi-Smith J, Philippe FL, Houle I. The incremental validity of narrative identity in predicting well-being: a review of the field and recommendations for the future. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 2016;20:142–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Proc 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Allshouse AA, Semple AL, Santoro NF. Evidence for prolonged and unique amenorrhea-related symptoms in women with premature ovarian failure/primary ovarian insufficiency. Menopause 2015;22:166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Benetti-Pinto CL, de Almeida DM, Makuch MY. Quality of life in women with premature ovarian failure. Gynecol Endocrinol 2011;27:645–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart K, Hemmesch A, Barnes E, Blissenbach T, Beisang A, Engel P; Chloe Barnes Advisory Council on Rare Diseases. Healthcare access, satisfaction, and health-related quality of life among children and adults with rare diseases. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2022;17:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boughton M, Halliday L. A challenge to the menopause stereotype: young Australian women’s reflections of ‘being diagnosed’ as menopausal. Health Soc Care Community 2008;16:565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COST Action BM1105, Badiu C, Bonomi M, Borshchevsky I, Cools M, Craen M, Ghervan C, Hauschild M, Hershkovitz E, Hrabovszky E, Juul A et al. Developing and evaluating rare disease educational materials co-created by expert clinicians and patients: the paradigm of congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017;12:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulam CB, Adamson SC, Annegers JF. Incidence of premature ovarian failure. Obstet Gynecol 1986;67:604–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Ventura JL, Wieners M, Covington SN, Vanderhoof VH, Ryan ME, Koziol DE, Popat VB, Nelson LM. The psychosocial transition associated with spontaneous 46,XX primary ovarian insufficiency: illness uncertainty, stigma, goal flexibility, and purpose in life as factors in emotional health. Fertil Steril 2010;93:2321–2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll MA, Davis MC, Aiken LS, Yeung EW, Sterling EW, Vanderhoof V, Calis KA, Popat V, Covington SN, Nelson LM. Psychosocial vulnerability, resilience resources, and coping with infertility: a longitudinal model of adjustment to primary ovarian insufficiency. Ann Behav Med 2016;50:272–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer AA, Au MG, Smith N, Plummer L, Lippincott MF, Balasubramanian R, Seminara SB. Evaluating co-created patient-facing materials to increase understanding of genetic test results. J Genet Couns 2021;30:598–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer AA, Quinton R, Morin D, Pitteloud N. Identifying the unmet health needs of patients with congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism using a web-based needs assessment: implications for online interventions and peer-to-peer support. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014;9:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Guideline Group on POI, Webber L, Davies M, Anderson R, Bartlett J, Braat D, Cartwright B, Cifkova R et al. ESHRE Guideline: management of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum Reprod 2016;31:926–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franca MM, Mendonca BB. Genetics of primary ovarian insufficiency in the next-generation sequencing era. J Endocr Soc 2020;4:bvz037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Helm M, Teede H, Vincent A. Symptoms, health behavior and understanding of menopause therapy in women with premature menopause. Climacteric 2014;17:666–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golezar S, Keshavarz Z, Ramezani Tehrani F, Ebadi A. An exploration of factors affecting the quality of life of women with primary ovarian insufficiency: a qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health 2020;20:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greil AL. Infertility and psychological distress: a critical review of the literature. Soc Sci Med 1997;45:1679–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groff AA, Covington SN, Halverson LR, Fitzgerald OR, Vanderhoof V, Calis K, Nelson LM. Assessing the emotional needs of women with spontaneous premature ovarian failure. Fertil Steril 2005;83:1734–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrieri GM, Martinez PE, Klug SP, Haq NA, Vanderhoof VH, Koziol DE, Popat VB, Kalantaridou SN, Calis KA, Rubinow DR et al. Effects of physiologic testosterone therapy on quality of life, self-esteem, and mood in women with primary ovarian insufficiency. Menopause 2014;21:952–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday L, Boughton M. Premature menopause: exploring the experience through online communication. Nurs Health Sci 2009;11:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javadpour S, Sharifi N, Mosallanezhad Z, Rasekhjahromi A, Jamali S. Assessment of premature menopause on the sexual function and quality of life in women. Gynecol Endocrinol 2021;37:307–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston-Ataata K, Flore J, Kokanović R. Women’s experiences of diagnosis and treatment of early menopause and premature ovarian insufficiency: a qualitative study. Semin Reprod Med 2020;38:247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AR, Tay CT, Melder A, Vincent AJ, Teede H. What are models of care? A systematic search and narrative review to guide development of care models for premature ovarian insufficiency. Semin Reprod Med 2020;38:323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalantaridou SN, Vanderhoof VH, Calis KA, Corrigan EC, Troendle JF, Nelson LM. Sexual function in young women with spontaneous 46,XX primary ovarian insufficiency. Fertil Steril 2008;90:1805–1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XT, Li PY, Liu Y, Yang HS, He LY, Fang YG, Liu J, Liu BY, Chaplin JE. Health-related quality-of-life among patients with premature ovarian insufficiency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual Life Res 2020;29:19–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao KL, Wood N, Conway GS. Premature menopause and psychological well-being. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2000;21:167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luiro K, Aittomaki K, Jousilahti P, Tapanainen JS. Long-term health of women with genetic POI due to FSH-resistant ovaries. Endocr Connect 2019;8:1354–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann E, Singer D, Pitkin J, Panay N, Hunter MS. Psychosocial adjustment in women with premature menopause: a cross-sectional survey. Climacteric 2012;15:481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LA, Porter AG, Pelligrini VA, Schnatz PF, Jiang X, Kleinstreuer N, Hall JE, Verbiest S, Olmstead J, Fair R. et al. ; Rachel’s Well Primary Ovarian Insufficiency Community of Practice Group. A design thinking approach to primary ovarian insufficiency. Panminerva Med 2017;59:15–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell LL, Adler JM, Carlsson J, Eriksson PL, Syed M. A conceptual review of identity integration across adulthood. Dev Psychol 2021;57:1981–1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orshan SA, Ventura JL, Covington SN, Vanderhoof VH, Troendle JF, Nelson LM. Women with spontaneous 46,XX primary ovarian insufficiency (hypergonadotropic hypogonadism) have lower perceived social support than control women. Fertil Steril 2009;92:688–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers S. Optimism and Mastery as Psychosocial Outcomes in Women with Primary Ovarian Insufficiency (Publication Number 3613821) [Ph.D., Walden University]. Ann Arbor: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, 2014. https://go.openathens.net/redirector/bc.edu?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/optimism-mastery-as-psychosocial-outcomes-women/docview/1512435775/se-2?accountid=9673 (18 November 2021, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer B. The contours of positive human health. Psychol Inq 1998;9:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt PJ, Luff JA, Haq NA, Vanderhoof VH, Koziol DE, Calis KA, Rubinow DR, Nelson LM. Depression in women with spontaneous 46, XX primary ovarian insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:E278–E287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer D, Mann E, Hunter MS, Pitkin J, Panay N. The silent grief: psychosocial aspects of premature ovarian failure. Climacteric 2011;14:428–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Stege JG, Groen H, Van Zadelhoff SJN, Lambalk CB, Braat DDM, Van Kasteren YM, Van Santbrink EJP, Apperloo MJA, Weijmar Schultz WCM, Hoek A. Decreased androgen concentrations and diminished general and sexual well-being in women with premature ovarian failure. Menopause 2008;15:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vemuri M, Covington SN, Baker VL. Primary ovarian insufficiency investigating women’s views and lived experiences. J Reprod Med 2019;64:171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura JL, Fitzgerald OR, Koziol DE, Covington SN, Vanderhoof VH, Calis KA, Nelson LM. Functional well-being is positively correlated with spiritual well-being in women who have spontaneous premature ovarian failure. Fertil Steril 2007;87:584–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE Jr, Gandek B, Guyer R, Deng N. Standardizing disease-specific quality of life measures across multiple chronic conditions: development and initial evaluation of the QOL Disease Impact Scale (QDIS(R)). Health Qual Life Outcomes 2016;14:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welt CK. Primary ovarian insufficiency: a more accurate term for premature ovarian failure. Clin Endocrinol 2008;68:499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yela DA, Soares PM, Benetti-Pinto CL. Influence of sexual function on the social relations and quality of life of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Rev Bras Ginecol E Obstet 2018;40:66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analyzed in support of this research.