Abstract

Objective

This article presents the Americas regional results of the WHO non-communicable diseases (NCDs) Country Capacity Survey from 2019 to 2021, on NCD service capacity and disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Setting

Information on public sector primary care services for NCDs, and related technical inputs from 35 countries in the Americas region are provided.

Participants

All Ministry of Health officials managing a national NCD programme, from a WHO Member State in the Americas region, were included throughout this study. Government health officials from countries that are not WHO Member States were excluded.

Outcome measures

The availability of evidence-based NCD guidelines, essential NCD medicines and basic technologies in primary care, cardiovascular disease risk stratification, cancer screening and palliative care services were measured in 2019, 2020 and 2021. NCD service interruptions, reassignments of NCD staff during the COVID-19 pandemic and mitigation strategies to reduce disruptions for NCD services were measured in 2020 and 2021.

Results

More than 50% of countries reported a lack of comprehensive package of NCD guidelines, essential medicines and related service inputs. Extensive disruptions in NCD services resulted from the pandemic, with only 12/35 countries (34%), reporting that outpatient NCD services were functioning normally. Ministry of Health staff were largely redirected to work on the COVID-19 response, either full time or partially, reducing the human resources available for NCD services. Six of 24 countries (25%) reported stock out of essential NCD medicines and/or diagnostics at health facilities which affected service continuity. Mitigation strategies to ensure continuity of care for people with NCDs were deployed in many countries and included triaging patients, telemedicine and teleconsultations, and electronic prescriptions and other novel prescribing practices.

Conclusions

The findings from this regional survey suggest significant and sustained disruptions, affecting all countries regardless of the country’s level of investments in healthcare or NCD burden.

Keywords: COVID-19, PUBLIC HEALTH, Organisation of health services

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This is the only region-wide analysis in the Americas, with data from 2019 to 2021, that has systematically measured the non-communicable disease (NCD) service capacity, disruptions of NCD services due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the mitigation strategies used to ensure continuity of services across 35 countries.

It is based on validated government information from a global standardised methodology, applied by the WHO since 2001 to monitor country capacity for NCD policies and services.

The main limitation is that this study did not provide the specificity of information by health centre level of NCD service capacity and disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, it did not provide information on the impact of these disruptions on people’s health outcomes.

The methodological limitation of this study is that it uses a self-administered questionnaire, and the process for responding to the questions could have varied across countries, with little space for qualitative data collection that could contribute to better understand the reasons for service disruptions. Also, country names, for comparison purposes, was not possible due to agreements in this global WHO survey with Member States.

Introduction

People with non-communicable diseases (NCDs) require timely diagnosis, continuous treatment and access to essential medicines, as well as ongoing monitoring of their conditions to prevent complications and premature death. Yet health systems in most low-income and middle-income countries are not adequately equipped to meet the growing NCD health demands, which has led to global calls for universal health coverage and strengthening primary care services to improve NCD (cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases) prevention and control.1 2 The WHO has established, and routinely monitors, targets to strengthen the health system response to NCDs that cover NCD guidelines and access to essential medicines and technologies, for the four main NCDs (cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory diseases), in addition to NCD risk factor targets.3 To strengthen NCD services, the focus has been on increasing the use of evidence-based national guidelines/protocols/standards for the management of the four main NCDs through a primary care approach in the public sector; as well as provision of drug therapy, including glycaemic control, and counselling for eligible persons at high risk to prevent heart attacks and strokes, with emphasis on the primary care level. These interventions are based on a cost effectiveness analysis, that, together with risk factor reduction interventions, are expected to reduce premature NCD mortality.4

In the Americas region, where an estimated 240 million people are living with a chronic condition5 health systems strengthening for NCDs has been a focus for the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) Member States since the adoption of a regional NCD plan of action by the Ministries of Health in 2013.6 Progress has been gradual and an assessment of the NCD plan of action, in 2020, noted that 17/35 countries (48.5%) had implemented a model of integrated management for NCDs, such as a chronic care model with evidence based guidelines, a clinical information system, self-care, community support and multidisciplinary team-based care.7 However, the COVID-19 pandemic subsequently has had a significant adverse impact on the Region, including a marked disruption of NCD services.

COVID-19 has been diagnosed in over 153 million people and led to more than 2.7 million deaths in the Region of the Americas, by the end of April 2022.8 The importance of NCDs as factors leading to severe COVID-19 related illness or death is now well documented, highlighting the importance of optimal NCD management.9 10 However, the pandemic has negatively impacted NCD management, related to the extensive primary care disruptions. Two years into the pandemic, 93% (25/27 countries) of countries in the Americas have reported disruptions in their essential primary care health services along the 66 tracer services in health systems (eg, cancer screening, diabetes management, hypertension management).11

So to what extent have these health system disruptions affected NCD services? This article presents information to respond to the research question on what is the NCD service capacity and disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, from the perspective of the health authorities responsible for the national NCD programmes and services across the Region of the Americas.

Methods

This is a descriptive study, in which information on NCD services and disruptions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic was extracted from the WHO dataset on the NCD Country Capacity Surveys (CCS) 2019–2021, from the 35 Member States of the PAHO. These are a diverse range of countries and to provide context to help situate the findings, the list of countries and selected characteristics are provided in online supplemental appendix 1. The CCS is a closed, non-randomised, web-based survey using a standardised global methodology that collects information on, among other topics, NCD services (module 4), and on NCD service disruptions (module 5). An NCD service was described as healthcare encompassing front-line health service delivery (primary care) or higher-level services for any of the main NCDs. All statistical analyses were carried out using STATA V.17 software (Stata, 2017). P values are not presented due to the descriptive characteristics of the study.

bmjopen-2022-070085supp001.pdf (70.2KB, pdf)

Responses to the CCS were provided by the official Ministry of Health authorities responsible for the national NCD programme, and submitted directly, using their unique access to the WHO CCS on-line tool. Data were then validated by PAHO/WHO, and in the event of any discrepancies or unanswered questions, feedback was sought from the designated Ministry of Health official.

The CCS was administered in March to June 2019; and from May to June 2020 module 5 was administered, with a response rate of 83% (29/35 countries). In 2021, the CCS was administered again from May to September 2021, with a 100% (35/35 countries) response rate.

Results presented are from all 35 countries from CCS 2021, and they are presented as a regional evaluation showing number and proportion of countries, without identifying countries, due to confidentiality agreements. A comparison of the impact of COVID-19 on NCD services in both years are presented, in which case data from the same 29 countries that responded to module 5 in both rounds (2020 and 2021) are presented.

Patient and public involvement

There is no patient involvement in this analysis.

Results

Overall limited NCD service capacity in primary care

For NCD service capacity, the CCS assesses the availability of evidence-based guidelines, essential medicines and technologies in primary care, cardiovascular disease risk stratification in clinical practice, and cancer screening and palliative care. Overall, NCD service capacity is rather limited in the Americas. Evidence-based national guidelines/protocols/standards for the four principal NCDs are available in only 63% (22/35) of countries, a slight improvement from 54% (19/35) in 2019. The most frequently available guidelines used in at least 50% of public healthcare facilities were on diabetes (74%), hypertension (69%), cancer (60%) and chronic respiratory diseases (51%) (online supplemental appendix 2). Only 29% of countries (10/35) offered cardiovascular risk stratification in clinical practice for the management of patients at high risk for heart attack and stroke in half or more of the primary healthcare facilities in the public sector.

Essential technologies for cardiovascular diseases (blood pressure measurement devices, total cholesterol measurement and urine strips for albumin assay) are available in at least half of the healthcare facilities of the public health sector in 51% (18/35) of countries; and only 34% (12/35) of countries reported having all technologies available for diabetes (blood glucose measurement, oral glucose test, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) test, dilated fundus examination, foot vibration perception by tuning fork and urine strips for glucose and ketone measurement). This situation has not changed since 2019 (table 1).

Table 1.

Proportion of countries (%) with available basic NCD technologies and essential medicines in primary care facilities of the public health sector, Americas Region 2019–2021

| Countries (%) | ||

| 2019 | 2021 | |

| All basic NCD technologies* | 5 | 4 |

| Measuring weight | 100 | 97 |

| Measuring height | 100 | 100 |

| Blood glucose measurement | 94 | 94 |

| Oral glucose tolerance test | 63 | 69 |

| HbA1c test | 51 | 54 |

| Dilated fundus examination | 37 | 51 |

| Foot vibration perception by tuning fork | 43 | 51 |

| Urine strips for glucose and ketone measurement | 63 | 57 |

| Blood pressure measurement | 97 | 94 |

| Total cholesterol measurement | 77 | 71 |

| Urine strips for albumin assay | 60 | 54 |

| Peak flow measurement spirometry | 31 | 17 |

| All essential NCD medicines† | 17 | 20 |

| Insulin | 83 | 91 |

| Aspirin (75/100 mg) | 94 | 91 |

| Metformin | 94 | 100 |

| Thiazide diuretics | 91 | 89 |

| ACE inhibitors | 91 | 89 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 77 | 74 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 89 | 89 |

| Beta blockers | 86 | 91 |

| Statins | 83 | 86 |

| Oral morphine | 49 | 51 |

| Steroid inhaler | 77 | 77 |

| Bronchodilator | 91 | 89 |

| Sulphonylurea(s) | 91 | 97 |

| Benzathine penicillin injection | 89 | 89 |

| Nicotin Replacement Therapy | 23 | 23 |

Range distribution of countries (%).  <25,

<25,  25–49,

25–49,  50–74,

50–74,  75–99,

75–99,  100. WHO NCD Country Capacity Survey, 2019–2021.

100. WHO NCD Country Capacity Survey, 2019–2021.

*Available in 50 or more of the public healthcare facilities.

†Available in 50 or more pharmacies.

NCD, non-communicable disease.

Essential medicines for cardiovascular diseases (aspirin, thiazide diuretics, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) calcium channel blockers, beta blockers and statins) were generally available in pharmacies in all almost all countries, with the exception of ARBs which are available in only 74% of countries (26/35). For diabetes, the essential medicines (insulin, metformin, sulphonylureas) are reported as being generally available in almost all countries and this situation has not changed since 2019. Regarding chronic respiratory diseases, steroid inhalers and bronchodilators are available in 77% (27/35) and 89% (31/35) of countries, respectively. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation remains very limited in the region, with only 23% (8/35) of countries reporting availability. Oral morphine was also identified as an essential medicine which was not widely available in pharmacies, with around half of the countries (51%, 18/35 countries) reporting its availability (table 1).

Cancer screening is offered in primary care in many countries in the Americas, with 63% (22/35 countries) reporting breast cancer screening; 83% (29/35) reporting cervical cancer screening and 43% (15/35) of countries reporting colorectal cancer screening. Overall, only 43% of the countries (15/35) reported having a screening programme for all three cancer types, and this situation had improved somewhat since 2019. Palliative care services to provide supportive and end-of-life care for people with cancer and other chronic conditions are offered in primary healthcare facilities in only 37% of countries (13/35) or community and home-based care in 46% of countries (16/35) and is yet another NCD service that requires strengthening.

NCD service disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic

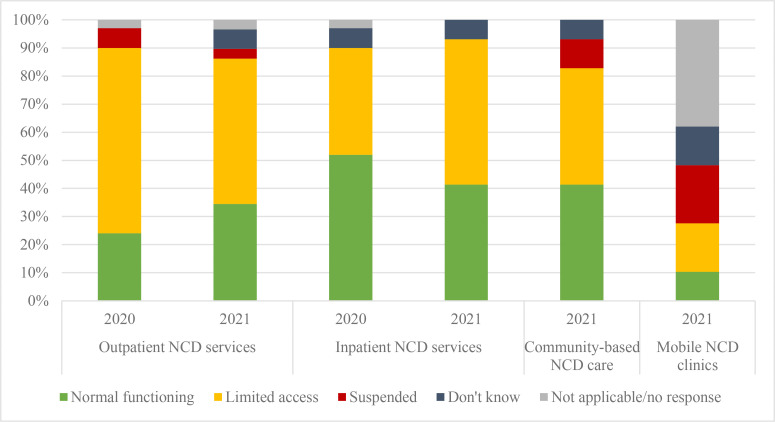

NCD services were identified as part of the government’s core set of essential health services to be maintained during the pandemic in 21 of 26 countries (81%). Nine countries (26%) reported allocating additional funding to NCDs in the government budget for the COVID-19 response (table 2). Despite this, only 12/35 countries (34%) reported that outpatient NCD services were functioning normally and only 11% of countries (4/35) reported that no activities for NCDs had been postponed due to the pandemic (figure 1). In 2021, three more countries reported that NCD outpatient services were functioning normally compared with 2020; while three fewer countries reported that NCD inpatient services were functioning normally (online supplemental appendix 3).

Table 2.

NCD service disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic, Americas Region, 2020–2021

| Countries (%) | Comparison of countries (%) in 2020 and in 2021 | ||

| 2021 (n=35 countries) |

2020 (n=29 countries) |

2021 (n=29 countries) |

|

| Redirected NCD resources | |||

| Staff reassigned/deployed to COVID-19 response | |||

| Some staff partially reassigned | 40 (14/35) | 38 (11/29) | 48 (14/29) |

| Some staff fully reassigned | 26 (9/35) | 21 (6/29) | 31 (9/29) |

| All staff partially reassigned | 20 (7/35) | 31 (9/29) | 28 (8/29) |

| All staff fully reassigned | 6 (2/35) | 7 (2/29) | 7 (2/29) |

| No staff reassigned | 6 (2/35) | 3 (1/29) | 7 (2/29) |

| Don’t know | 3 (1/35) | 0 (0/29) | 3 (1/29) |

| Government NCD funds allocated to support COVID-19 response | |||

| None or not yet | 29 (10/35) | 59 (17/29) | 31 (9/29) |

| Don’t know | 49 (17/35) | 34 (10/29) | 48 (14/29) |

| 1%–25% | 14 (5/35) | 0 (0/29) | 10 (3/29) |

| 26%–50% | 3 (1/35) | 0 (0/29) | 3 (1/29) |

| 51%–75% | 6 (2/35) | 3 (1/29) | 7 (2/29) |

| 76%–100% | 0 (0/35) | 3 (1/29) | 0 (0/29) |

| NCD services included in COVID-19 response | |||

| NCD services included as part of the list of essential health services in the COVID-19 plan | |||

| Cardiovascular disease services | 95 (20/21) | N/A | N/A |

| Cancer services | 86 (18/21) | N/A | N/A |

| Diabetes services | 100 (21/21) | N/A | N/A |

| Chronic respiratory disease services | 86 (12/21) | N/A | N/A |

| Chronic kidney disease and dialysis services | 0 (0/35) | N/A | N/A |

| Tobacco cessation services | 48 (10/21) | N/A | N/A |

| Other | 14 (3/21) | N/A | N/A |

| Additional funding allocated for NCDs | 26 (9/35) | 10 (3/29) | 10 (3/29) |

| NCD activities postponed due to COVID-19 pandemic | |||

| None | 11 (4/35) | 17 (5/29) | 10 (3/29) |

| Implementation of NCD surveys | 40 (14/35) | 55 (16/29) | 45 (13/29) |

| Public screening programmes for NCDs | 51 (18/35) | 45 (13/29) | 48 (14/29) |

| WHO PEN package implementation* | 23 (8/35) | 21 (6/29) | 24 (7/29) |

| WHO HEARTS package† implementation | 29 (10/35) | 31 (9/29) | 31 (9/29) |

| Mass communication campaigns | 34 (12/35) | 24 (7/29) | 34 (10/29) |

| Other | 11 (4/35) | 24 (7/29) | 10 (3/29) |

WHO NCD Country Capacity Survey, 2019–2021. Round 1 (R1) conducted in 2020 and Round 2 (R2) conducted in 2021. Data for comparison not available between 2020 and 2021.

*WHO PEN package is a set of essential primary care interventions for the main NCDs, and can be found here: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240009226.

†WHO Hearts package is the primary care interventions to improve hypertension diagnosis, treatment and control and can be found here: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240001367.

N/A, not applicable; NCD, non-communicable disease.

Figure 1.

Proportion of countries (%) with disruptions in NCD services during the COVID-19 pandemic, Americas region, 2020–2021. NCD, non-communicable disease.

Ministry of Health staff designated to work on NCD services were largely redirected to work on the COVID-19 response, either full time or part time, reducing the human resources available to provide care for people with NCDs. Only 2 countries (6%, 2/35 countries) reported that no NCD staff had been redirected to support the COVID-19 effort. By 2021 this situation had worsened, with 14 countries reporting NCD staff were reassigned to the pandemic, up from 11 countries in 2020 (table 2).

Regarding service disruptions, outpatient NCD services were suspended in one country, community NCD services were suspended in four countries and mobile NCD clinics were suspended in six countries. The majority of countries reported limited access to outpatient services (19/35 countries, 54%), and to inpatient NCD services (19/35 countries, 54%) (figure 1).

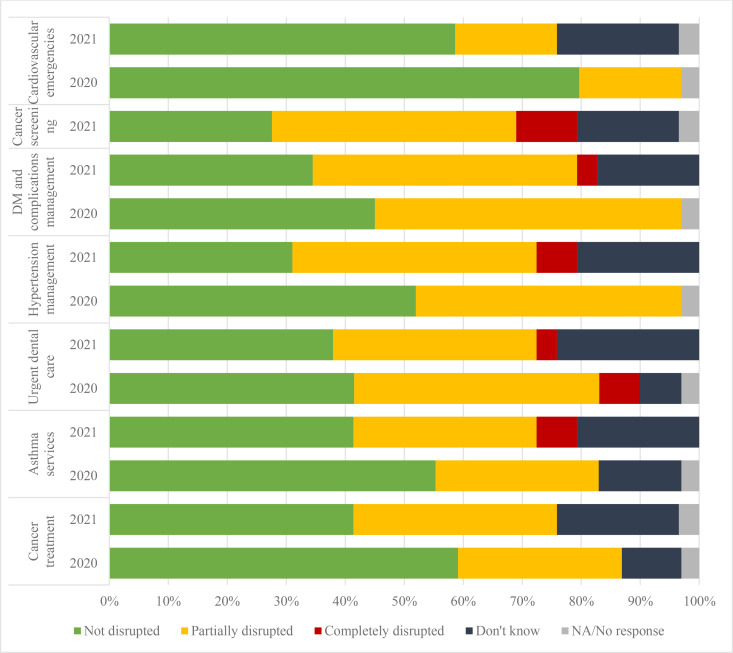

The disruption in NCD services, either partially or completely, affected all types of care for people with NCDs, but more so for diabetes and hypertension services (figure 2 and online supplemental appendix 4). The main reasons cited for disruption of NCD services related to human resources, where 17 countries (74%, 17/24 countries) reported it was due to NCD staff deployed to the COVID response, or simply insufficient clinical staff to provide the service (46%, 11/24 countries). Two countries (8%, 2/24 countries) noted clinical staff did not have personal protective equipment which affected service provision. Six countries (25%, 6/24 countries) reported stock out of essential NCD medicines and or diagnostics at the health facility level which affected service continuity. Inpatient NCD services were mainly disrupted due to the cancellation of elective procedures (63%, 15/24 countries), and hospital beds or inpatient service were simply not available in 46% of countries (11/24 countries). The extent of disruptions for NCD services worsened in 2021, as compared with the situation in 2020 for all types of NCD services (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of countries (%) with NCD Service Disruptions by Service Type due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Americas Region, 2020–2021. Country does not provide the service. Cancer screening was not included in the 2020 survey. Cardiovascular emergencies include myocardial infarctions, stroke and cardiac arrhythmias. DM, diabetes mellitus; N/A, not applicable; NCD, non-communicable disease.

Beyond service disruption, planned NCD activities have been suspended or postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and only small improvements over time were observed (table 2). The activities most commonly reported as suspended were screening people for cancer, diabetes and other NCDs in 51% of the countries (18/35 countries), the implementation of NCD surveys, where 14 countries (40%) report postponing surveys and the implementation of the Hearts technical package was suspended or postponed in 10 countries.

Perhaps the more influential driver of NCD service disruptions, however, is on the demand side, where COVID-19 lock down measures and fear or mistrust with community transmission led to many people not seeking care or patients not presenting for care, as reported in 18 countries and 17 countries, respectively (75%, 18/24 countries; 71% 17/24 countries). Financial difficulties (46% 11/24 countries) and travel restrictions hindering people’s access to health facilities (50%, 12/24 countries) were also cited as important causes of disrupted NCD services.

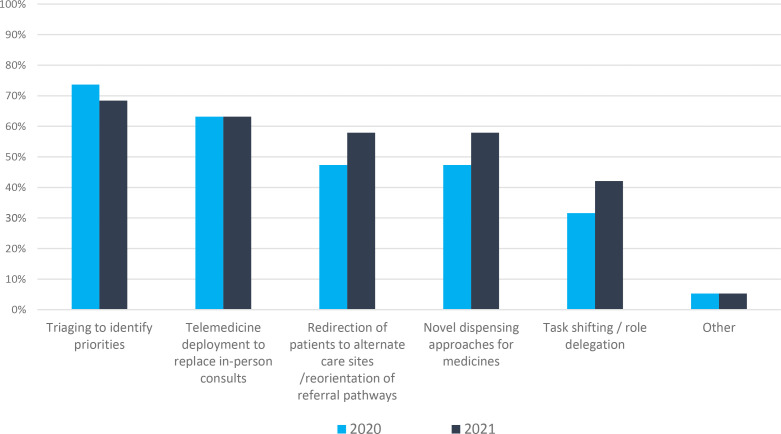

Strategies and plans to mitigate NCD service disruptions

Many different approaches were employed to minimise the disruption in NCD services during the pandemic which did not change over 2020–2021: home-based care, triage patients and prioritise care based on severity of condition, and support for self-care were most commonly reported (figure 3). Telemedicine was employed to replace in person consultations (16/24 countries, 67%) and this was sustained over time (online supplemental appendix 5).

Figure 3.

Proportion of countries (%) with approaches employed to overcome NCD service disruptions due to COVID-19 Pandemic, Americas Region, 2020–2021. NCD, non-communicable disease.

When prompted on plans to reinitiate disrupted NCD services, most respondents indicated that the priority was to train healthcare professionals in NCD diagnosis and treatment, reinitiate cancer screening services, continue use of recurring medicine prescription and continue the use of telemedicine.

Respondents also identified their immediate needs to assist with building stronger health services for NCDs. The main needs identified were guidelines for NCD and COVID-19 clinical management; guidance on promoting healthy lifestyles especially post-COVID-19 to motivate behaviour change; extension of telemedicine services to facilitate continuous communication with patients especially those living in remote areas or large distances from health facilities; systems for tracking patients with NCDs including Apps that can better support self-management; and rehabilitation services for those people suffering long-term symptoms from COVID-19 including respiratory symptoms.

Discussion

This is the only region-wide survey in the Americas, that has systematically measured the NCD service capacity, the disruption of NCD services due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the mitigation strategies used to ensure continuity of services. More than half of the countries in the region do not have the comprehensive package of guidelines, technologies and medicines for all four major NCDs and there was little reported change between 2019 and 2021 on the NCD service capacity. Nonetheless, the Americas region has been noted to have among the higher levels of NCD service capacity as compared with the other World regions12; and a much greater NCD service capacity than as reported in a similar survey conducted in primary care centres in India.13

The findings from this regional survey suggest significant and sustained disruptions, affecting all countries regardless of the country’s level of investments in healthcare or NCD burden. This situation appears to be consistent with the situation reported in other regions of the world.12 14–16

To assist governments in maintaining essential NCD services at this time, PAHO/WHO has published guidelines to assist with triaging patients, use telemedicine and multimonth prescriptions more broadly, and reorganise oncology services.17 The extent of use or application of these guidelines is not known, although the results of this survey indicate that many national NCD programme managers had use for the guidance on maintaining essential NCD services.

More research is needed to document the extent, and consequences of NCD service disruption in the Americas region. Further research is also needed to better understand how effective the mitigation strategies of triaging patients, e-prescriptions and telemedicine, were as substitution for face-to-face encounters; and whether inequities in access to primary NCD services were further exacerbated by the NCD service disruptions.

Some of this research has begun in the region. For example, a survey of NCD patient advocacy organisations in Latin America, noted the dissatisfaction and poorer quality of care during 2020–2021, where 52% of respondents experienced delays of 30 days or more for primary care; telemedicine was reported as not accessible to patients by 37% of respondents and a majority (76%) of NCD patients faced challenges with refilling prescription medication.18 In Mexico, the social security system, IMSS, noted reduced screening for breast and cervical cancer (−79% and −68%), diabetes and hypertension care (−32% in both), attributed to underfunding, shortages in human resources and reallocation of health staff and infrastructure due to COVID-19.19

Similarly in the USA, cancer screening declined sharply in 2020 compared with 2019, (breast, −90.8%; colorectal, −79.3%; prostate, −63.4%) and breast cancer diagnosis has been observed to decrease during the pandemic.20 21 The USA has also been noted to have the highest absolute number of excess deaths in 2020 (458 000) as compared with 29 other countries.22 A large excess death rate of 64% more deaths in 2020 than 2019 were also reported in Ecuador, where it was found that indigenous populations had four times the excess death rate of the majority mestizo group, indicating unequal impact of COVID on vulnerable populations.23

Brazil has also reported significant declines in utilisation of primary care services by people with NCDs,24 and in one state almost a third of people living with NCDs reported impaired management of their NCD as a result of the COVID-19 restrictions.25 Brazil has also noted excess deaths from cancer and cardiovascular diseases related to the COVID-19 pandemic.26 The full extent of foregone care, however, is yet to be observed, and more research is needed throughout countries in the Americas region, to determine the impact of NCD service disruptions on diagnosis, treatment and health outcomes for people with NCDs. For example, in the USA, cancer mortality is expected to increase due to reduced screening and early diagnosis,20 and in the UK, a substantial increase in cancer deaths and morbidity have been predicted due to COVID-19 restrictions.27–29

Improving NCD service capacity and NCD management is tied closely to universal health coverage and primary care strengthening. As a way forward, the Americas region has charted a path for creating more resilient health services, which includes strengthening primary care and increasing financial investments in health systems.30 And as COVID-19 cases continue to decline and health services resume to capacity, the public health priority now needs to be on improving the equitable access to NCD diagnosis and treatment in primary care, which includes updating NCD guidelines, training multidisciplinary healthcare teams, increasing access to essential NCD medicines and technologies, improving self-management support, among others.31 With regard to NCD medicines and technologies, governments in the Americas region can use the PAHO Strategic Fund which offers a useful mechanism for pooled procurement of quality assured essential NCD medicines and technologies, and was successfully deployed in government responses to COVID-19, and other health priorities.32

Conclusions

This analysis documents the limitations in NCD service capacity in the Americas region, and the degree of disruptions in access to essential NCD services and medicines. While there are limited published data on the impact that these service disruptions will have on health outcomes, given the significant number of people with NCDs in the Americas, the limited NCD service capacity and extensive disruptions in NCD services from the COVID-19 pandemic, the priority must now be strengthening primary care services for NCDs and addressing the backlog and foregone care for NCD management.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SL and RC conceived the original idea. RC, CC and DO collected and analysad the data. SL, RC, CC, DO and AH interpreted the results. SL wrote the paper, RC, CC, DO and AH reviewed and contributed to the paper. SL, RC, CC, DO and AH approved the final version. SL acted as guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data reported in this analysis are from the WHO NCD Country Capacity Survey and available in the WHO Global Health Observatory. Data from the Americas region are available on reasonable request (deidentified data by country) from PAHO/WHO per request at: nmhsurveillance@paho.org.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.United Nations . Political declaration of the high-level meeting on universal health coverage “Universal health coverage: moving together to build a healthier world. New York: UN; 2019. Available: https://www.un.org/pga/73/wp-content/uploads/sites/53/2019/07/FINAL-draft-UHC-Political-Declaration.pdf [Accessed 08 Apr 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Global action plan for the prevention and control of ncds 2013-2020. Geneva: WHO; 2013. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506236 [Accessed 08 Apr 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . NCD global monitoring framework. Indicator definitions and specifications. Geneva: WHO; 2014. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/noncommunicable-diseases-global-monitoring-framework-indicator-definitions-and-specifications [Accessed 08 Apr 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . Tackling ncds best buys. best buys and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. WHO: Geneva; 2017. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9-eng.pdf [Accessed 25 Apr 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark A, Jit M, Warren-Gash C, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of the population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions in 2020: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e1003–17. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30264-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan American Health Organization . Plan of action for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2014. Available: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/35009 [Accessed 08 Apr 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan American Health Organization . Plan of action for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: final report. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2020. Available: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/cd58inf6-plan-action-prevention-and-control-noncommunicable-diseases-final-report [Accessed 08 Apr 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan American Health Organization . PAHO COVID-19 dashboard. Washington, D.C: PAHO; 2022. Available: https://ais.paho.org/phip/viz/COVID19Table.asp [Accessed 02 May 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azarpazhooh MR, Morovatdar N, Avan A, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and burden of non-communicable diseases: an ecological study on data of 185 countries. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2020;29:105089. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang AY, Cullen MR, Harrington RA, et al. The impact of novel coronavirus COVID-19 on noncommunicable disease patients and health systems: a review. J Intern Med 2021;289:450–62. 10.1111/joim.13184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . Third round of the global pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Geneva: WHO; 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS_continuity-survey-2022 [Accessed 10 Apr 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . Rapid assessment of service delivery for ncds during the COVID-19 pandemic. Geneva: WHO; 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/rapid-assessment-of-service-delivery-for-ncds-during-the-covid-19-pandemic [Accessed 08 Apr 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnan A, Mathur P, Kulothungan V, et al. Preparedness of primary and secondary health facilities in India to address major noncommunicable diseases: results of a national noncommunicable disease monitoring survey (NNMS). BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21:757. 10.1186/s12913-021-06530-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dyer O. Covid-19: pandemic is having “severe” impact on non-communicable disease care, who survey finds. BMJ 2020;369:m2210. 10.1136/bmj.m2210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suva MA, Suvarna VR, Mohan V. Impact of COVID-19 on noncommunicable diseases (NCDS). J Diabetol 2021;12:252. 10.4103/JOD.JOD_75_20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ágh T, van Boven JF, Wettermark B, et al. A cross-sectional survey on medication management practices for noncommunicable diseases in europe during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Pharmacol 2021;12:685696. 10.3389/fphar.2021.685696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan American Health Organization . Maintaining essential services for people with noncommunicable diseases; 2020. Available: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/52493 [Accessed 28 Apr 2022].

- 18.Kruse MH, Durstine A, Evans DP. Effect of COVID-19 on patient access to health services for noncommunicable diseases in Latin America: a perspective from patient advocacy organizations. Int J Equity Health 2022;21:45. 10.1186/s12939-022-01648-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doubova SV, Robledo-Aburto ZA, Duque-Molina C, et al. Overcoming disruptions in essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. BMJ Glob Health 2022;7:e008099. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-008099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen RC, Haynes K, Du S, et al. Association of cancer screening deficit in the United States with the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol 2021;7:878–84. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang Y-J, Baek JM, Kim Y-S, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the diagnosis and surgery of breast cancer: a multi-institutional study. J Breast Cancer 2021;24:491–503. 10.4048/jbc.2021.24.e55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Islam N, Shkolnikov VM, Acosta RJ, et al. Excess deaths associated with covid-19 pandemic in 2020: age and sex disaggregated time series analysis in 29 high income countries. BMJ 2021;373:n1137. 10.1136/bmj.n1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuéllar L, Torres I, Romero-Severson E, et al. Excess deaths reveal unequal impact of COVID-19 in Ecuador. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e006446. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malta DC, Gomes CS, Silva A da, et al. Use of health services and adherence to social distancing by adults with noncommunicable diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic, brazil, 2020. Cien Saude Colet 2021;26:2833–42. 10.1590/1413-81232021267.00602021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leite JS, Feter N, Caputo EL, et al. Managing noncommunicable diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic in brazil: findings from the PAMPA cohort. Cien Saude Colet 2021;26:987–1000. 10.1590/1413-81232021263.39232020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jardim BC, Migowski A, Corrêa F de M, et al. Covid-19 in Brazil in 2020: impact on deaths from cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Rev Saude Publica 2022;56:22. 10.11606/s1518-8787.2022056004040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sud A, Torr B, Jones ME, et al. Effect of delays in the 2-week-wait cancer referral pathway during the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer survival in the UK: a modelling study. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:1035–44. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30392-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in england, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:1023–34. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30388-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai AG, Pasea L, Banerjee A, et al. Estimated impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer services and excess 1-year mortality in people with cancer and multimorbidity: near real-time data on cancer care, cancer deaths and a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e043828. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Etienne CF, Fitzgerald J, Almeida G, et al. COVID-19: transformative actions for more equitable, resilient, sustainable societies and health systems in the Americas. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e003509. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luciani S, Agurto I, Caixeta R, et al. Prioritizing noncommunicable diseases in the Americas region in the era of covid-19. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2022;46:e83. 10.26633/RPSP.2022.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lal A, Lim C, Almeida G, et al. Minimizing COVID-19 disruption: ensuring the supply of essential health products for health emergencies and routine health services. Lancet Reg Health Am 2022;6:100129. 10.1016/j.lana.2021.100129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-070085supp001.pdf (70.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data reported in this analysis are from the WHO NCD Country Capacity Survey and available in the WHO Global Health Observatory. Data from the Americas region are available on reasonable request (deidentified data by country) from PAHO/WHO per request at: nmhsurveillance@paho.org.