Abstract

Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF-4α) (nuclear receptor 2A1) is an essential regulator of hepatocyte differentiation and function. Genetic and molecular evidence suggests that the tissue-restricted expression of HNF-4α is regulated mainly at the transcriptional level. As a step toward understanding the molecular mechanism involved in the transcriptional regulation of the human HNF-4α gene, we cloned and analyzed a 12.1-kb fragment of its upstream region. Major DNase I-hypersensitive sites were found at the proximal promoter, the first intron, and the more-upstream region comprising kb −6.5, −8.0, and −8.8. By the use of reporter constructs, we found that the proximal-promoter region was sufficient to drive high levels of hepatocyte-specific transcription in transient-transfection assays. DNase I footprint analysis and electrophoretic mobility shift experiments revealed binding sites for HNF-1α and -β, Sp-1, GATA-6, and HNF-6. High levels of HNF-4α promoter activity were dependent on the synergism between either HNF-1α and HNF-6 or HNF-1β and GATA-6, which implies that at least two alternative mechanisms may activate HNF-4α gene transcription. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments with human hepatoma cells showed stable association of HNF-1α, HNF-6, Sp-1, and COUP-TFII with the promoter. The last factor acts as a repressor via binding to a newly identified direct repeat 1 (DR-1) sequence of the human promoter, which is absent in the mouse homologue. We present evidence that this sequence is a bona fide retinoic acid response element and that HNF-4α expression is upregulated in vivo upon retinoic acid signaling.

Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF-4α) is a liver-enriched transcription factor which, together with other factors, plays a key role in the tissue-specific expression of a large number of genes (42). Besides HNF-4α's crucial role in the adult liver, where it regulates genes involved in various metabolic pathways (17), HNF-4α function has been implicated in early endodermal development (14). Mouse embryos lacking HNF-4α die before completing gastrulation due to visceral endoderm dysfunction (7). This early-lethal phenotype could be rescued by employing complementation of HNF-4α-deficient embryos with a tetraploid embryo-derived visceral endoderm (32). Analysis of gene expression patterns of the rescued embryos revealed that HNF-4α was dispensable for early developmental specification of the liver but was essential for subsequent steps of hepatocyte differentiation (32). In humans, heterozygous mutations in the HNF-4α gene are associated with an early-onset form of type II diabetes called maturity onset diabetes of the young 1 (52). In addition to the several mutations in the coding region, a 7-bp deletion at the 5′ regulatory region was recently found in association with diabetes (39), suggesting that the expression and activity of HNF-4α are important for pancreatic β-cell function.

The liver-enriched transcription factors are part of a complex transcriptional network which seems to be responsible for both the determination and the maintenance of the hepatic phenotype. This network is established by a number of autoregulatory and cross-regulatory pathways securing balanced, high-level expression of the main factors in hepatocytes (13, 18, 22, 24, 26, 48). HNF-4α has been considered to be at the top of the hierarchy of the transcription factor cascade that drives hepatocyte differentiation, since it is an essential regulator of the HNF-1α gene (26, 48). To fully understand how this regulatory network is established, knowledge of the regulation of the HNF-4α gene itself is required. Previous studies of the mouse HNF-4α promoter revealed a potential reciprocal regulation of HNF-4α expression by HNF-1α (47, 54). This assumption was based on the identification of a functional HNF-1 binding site in the proximal-promoter region (54). However, during visceral endoderm differentiation HNF-4α is activated at an earlier stage than HNF-1α, arguing against the importance of HNF-1α in the initial activation of the HNF-4α gene (5, 12, 14). In addition, HNF-1α-deficient mice showed normal levels of HNF-4α in the liver (38). More-recent studies on GATA-6- and HNF-1β-deficient mice revealed that these two factors may directly or indirectly regulate the mouse HNF-4α gene, as its expression was virtually abolished in both animal models (2, 8, 35). The failure of GATA-6−/− and HNF-1β−/− embryos to properly develop visceral endoderms paralleled the lack of HNF-4α expression and provided strong evidence that these two factors indeed lie upstream of HNF-4α in the transcriptional cascade that regulates early endodermal differentiation (2, 8, 35). Evidence for the potential involvement of at least two additional factors in the regulation of the HNF-4α gene has been recently reported. These are HNF-6 and CPF/FTF, which can bind to and transactivate the mouse HNF-4α promoter (30, 37).

To gain a comprehensive insight into the transcriptional regulation of HNF-4α, we cloned and characterized the promoter region of the human HNF-4α gene. We found that in cultured hepatoma cells the proximal-promoter region was sufficient to drive high levels of expression. Within this region we mapped binding sites for transcription factors HNF-1α and -β, Sp-1, HNF-6, and GATA-6. We describe two alternative mechanisms of how these factors may regulate HNF-4α expression. Moreover, we identified a functional hormone response element (HRE) in the human promoter which is not conserved in the mouse sequence. This element binds COUP-TFII (27), which has a repressive effect on promoter activity; upon retinoic acid signaling, binding of RXRα-RARα heterodimers to the HRE leads to hormone-dependent upregulation of the HNF-4α gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of human HNF-4α genomic clones and plasmid constructions.

A human λEMBL4 genomic DNA library was screened with a 0.6-kb human HNF-4α cDNA fragment encoding the N-terminal part of the protein. The resultant genomic clones were analyzed by restriction enzyme mapping, and the SalI/SacII fragment from one clone containing the upstream 12.1-kb region of the HNF-4α gene was subcloned into the XhoI/BglII sites of pGL3 basic vector (Promega). The resulting plasmid contains the region from bp +67 to kb −12.1 of the human HNF-4α gene in front of the firefly luciferase reporter cassette. 5′ deletion mutants were prepared either by restriction enzyme digestions or by progressive unidirectional digestions with exonuclease III. Site-directed mutagenesis of the footprinted regions was performed with the GeneEditor kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The following oligonucleotides were used for mutagenesis: HNF-1 site mutant, −104 GGGTCGATGGTGGATCCGTCCCCCGCCGGTGGATAGGCTG −143; HRE mutant, −298 GGTGAGTCGACGCACAAATGAGTGCCCG TGA −268; HNF-6 site mutant, −423 GCATTGAGGGTAGAATCTAGAGATTTGGGAAGTTATTG −386; GATA-6 site mutant, −419 AATGCTTTTGCAAAGCTTAGGCTGCCCCATGGCCC −453; Sp-1 site mutant, −160 ATCCCTGCAGCCATGGCCAGCCTATCCACCG −130. Mutated nucleotides are underlined.

The 6xHRE-AdML-CAT plasmid was generated by ligating a double-stranded, phosphorylated oligonucleotide corresponding to the region comprising nucleotides (nt) −298 to −277 into the SalI site of plasmid AdML-44-CAT (21). The construction of pCMV-HNF-1α, pCMV-COUP-TFII, pCMV-RXRα, and pCMV-RARα has been described previously (24, 25). pRSV-HNF-1β (10), pCMV-hGATA-6 (15), pCMV-HNF-6 (31), and pCMV-HNF-3α (29) were kind gifts from R. Cortese, T. Evans, F. Lemaigre, and R. Costa, respectively. pCMV-PPARα (49) and pCMV-VDR (20) were obtained from A. Aranda. pSG-ERα (28) and pCMV-T3Rβ (4) and pCMV-LXRα (51) were from M. Parker and D. Mangelsdorf, respectively. pCMV-CPF/FTF containing the human CPF open reading frame (GenBank accession no. NM_003822) was cloned by PCR from HepG2 cDNA. Proper expression by all the vectors in transfected Cos-1 cells was tested.

Primer extension, reverse transcription (RT-PCR), and DNase I-hypersensitive site analysis.

For primer extension, 10 μmol of a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe, corresponding to nt +162 to +188 of the human HNF-4α gene, was hybridized to 10 μg of poly(A) RNA prepared from HepG2 cells in a buffer containing 40 mM PIPES, pH 6.4, 1 mM EDTA, 0.4 M NaCl, and 80% formamide. The annealed products were precipitated and resuspended in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris, pH 8.3, 40 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 10 U of RNasin. After addition of 10 U of SuperScript reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL), the reaction was allowed to proceed for 60 min at 37°C, followed by a 30-min digestion with 5 μg of DNase-free RNase. The reaction products were extracted with phenol-chloroform, precipitated with ethanol, and electrophoresed in 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gels.

For RT-PCR analysis, total RNA from HepG2 cells was first treated with 10 U of DNase I (Gibco-BRL) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by extractions with phenol-chloroform and precipitation with ethanol. cDNA synthesis was performed with SuperScript reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL) using oligo(dT) and random hexamer primers. The cDNAs were directly used for PCR amplification (21 cycles) in the presence of 10 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP with primer sets from the human HNF-4α 3′ untranslated region (UTR) (see below). For normalization, the human acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein was amplified by primers 5′ GGAAGGCTGTGGTGCTGATGG 3′ and 5′AAGGAGAAGGGGGAGATGTTG 3′ (41).

Two probes, the HindIII-EcoRV fragment corresponding to nt −3854 to −4134 and the KpnI-EcoRI fragment corresponding to nt −4660 to −5224 were used to map the DNase I-hypersensitive sites in the proximal- and distal-promoter regions, respectively. Nuclei were prepared from HepG2 cells as described previously (22) and partially digested on ice for 10 min by 0 to 20 U of DNase I (Gibco-BRL) in a buffer containing 60 mM KCl, 15 mM NaCl, 15 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.5 mM spermidine, 0.15 mM spermine, and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol. The reactions were stopped by addition of EDTA to 30 mM, followed by digestion with proteinase K at 56°C for 12 h. DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform, precipitated with ethanol, and digested with either KpnI or HindIII. Digestion products were analyzed by Southern blotting.

In vitro DNA binding assays.

Nuclear extracts from HepG2 and transfected Cos-1 cells were prepared as described previously (22, 23). For DNase I footprint analysis three 5′-end-labeled probes encompassing nt −503 to +67, nt −450 to −45, and nt −194 to −595 were prepared and incubated with HepG2 nuclear extracts in a buffer containing 50 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, 0.1 μM zinc acetate, 50 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 30 μg of poly(dI-dC)/ml, 0.25 μg of linearized pUC-18 DNA/ml, and 2% polyvinyl alcohol. After incubation on ice for 45 min, MgCl2 and CaCl2 were added to 1 and 0.2 mM final concentrations, respectively, followed by digestion with 30 μg of DNase I for 5 min. The reactions were stopped by the addition of an equal volume of 20 mM EDTA–1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–50 μg of E. coli tRNA/ml, followed by digestion with 2 μg of proteinase K. After extraction with phenol-chloroform, the DNA fragments were precipitated by ethanol and analyzed in 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gels.

Mobility shift assays with end-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide probes were performed as described previously (22, 23). The oligonucleotide sequences were as follows: FP-1, 5′ TCGACCGATTAACCATTAACCCCCACCCC nt −97; FP-2, 5′ TCGAGCAGCCCCGCCCAGCC nt −139; FP-3, 5′ TCGAGGTGAGTCAAGGGTCAAATGAG nt −277; FP-4, 5′ TCGAGGGTAGAAGTCAATGATTTGGG nt −395; FP-5, 5′ TCGAGGCAGCCTTATCTCTGCAAAAGC nt −422.

For supershift, Western blots, and immunoprecipitations the antibodies used were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (HNF-1α, Sp-1, HNF-3α, GATA-6, and HNF-6). Anti- HNF-1β (5), anti-RXRα and anti-RARα (16), and anti-COUP-TFII (4) were obtained from S. Cereghini, P. Chambon, and M. Parker, respectively. A polyclonal antibody against HNF-4α was raised by immunization of New Zealand White rabbits by a keyhole limpet hemocyanin-linked peptide corresponding to the very C-terminal 12 amino acids of the human HNF-4 protein. In Western blots a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Jackson Laboratories) was used as the secondary antibody and ECL (APB) was used for chemiluminescence detection.

Cell culture and transfections.

HepG2 and Cos-1 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum. The cells were seeded 24 h before transfection at 50 to 60% confluence. In experiments where 9-cis-retinoic acid induction was used, the cells were plated in medium containing 10% dextran-charcoal-stripped fetal calf serum. Various amounts of plasmids along with 1.5 μg of pCMV-β-gal plasmid were introduced into the cells by the calcium phosphate-DNA coprecipitation method as described previously (22, 23). Thirty-six hours later the cells were harvested and lysed by three consecutive freeze-thaw cycles. Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase and β-galactosidase assays were performed as described previously (22, 23). Luciferase assays were performed using the luciferase assay kit (Promega). All data were normalized to β-galactosidase internal-control values.

Chromatin immunoprecipitations.

The chromatin immunoprecipitation assay was performed as described previously (36), with several modifications. Briefly, cells were treated with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Cross-linking was stopped by the addition of glycine to a final concentration of 0.125 M. The cells were washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and swelled on ice for 10 min in a solution containing 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.8, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.1% NP-40, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Following Dounce homogenization (20 strokes; pestle A), the nuclei were collected and resuspended in sonication buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitors and sonicated on ice to an average length of 200 to 1,000 bp. The samples were centrifuged at 20,000 × g and precleared with protein G-Sepharose in the presence of 2 μg of sonicated λ DNA and 1 mg of bovine serum albumin/ml. Twenty-five A260 units of the precleared chromatin was immunoprecipitated with 5 μl of antibodies, and the immune complexes were collected by adsorption to protein G-Sepharose. The beads were washed twice with sonication buffer, twice with sonication buffer containing 500 mM NaCl, twice with 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0)–1 mM EDTA–250 mM LiCl–0.5% NP-40–0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and twice with Tris-EDTA buffer. The immunocomplexes were eluted with 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0–1 mM EDTA–1% SDS at 65°C for 10 min, adjusted to 200 mM NaCl, and incubated at 65°C for 5 h to reverse the cross-links. After successive treatments with 10 μg of Rnase A and 20 μg of proteinase K/ml, the samples were extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. One tenth of the immunoprecipitated DNA and input DNA (from extracts corresponding to 0.025 A260 units) was analyzed by PCR using primers from sequences surrounding the human HNF-4α proximal promoter (GGCAGCCTTATCTCTGCAAAAGC −422 and TCGAGGGGTGGGGTTAATGGTTAATC −119) or the 3′ UTR of the HNF-4α gene (sense oligonuceotide, 5′ GGAGATGACTTGAGGCCTTACT; antisense oligonucleotide, 5′ GGGGAATCGTTTCCAAGGCCTC). Amplifications (25 cycles) were performed in the presence of 10 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP, and the products were analyzed in 4% polyacrylamide gels. To ensure that the amounts of PCR products accurately reflected the amounts of template DNA, control PCRs (20, 25, and 30 cycles) were performed with decreasing amounts of templates (not shown).

RESULTS

Cloning and functional mapping of the human HNF-4α upstream regulatory region.

Screening a human genomic λEMBL-4 library with an N-terminal fragment of the human HNF-4α cDNA, including the 5′ UTR and the A/B domain, resulted in four positive clones. Restriction enzyme mapping and Southern blot analysis revealed that one clone contained part of the first exon and an approximately 12.1-kb upstream region of the human HNF-4α gene. We performed extensive restriction enzyme mapping and determined the nucleotide sequences of several parts of this clone and compared the data with the human chromosome 20 working draft sequence (GenBank accession no. NT_011382). All the sequences determined as well as the restriction enzyme pattern were identical to the deposited sequence and pattern of the human HNF-4α gene, confirming that the isolated clone represents the unrearranged HNF-4α upstream region.

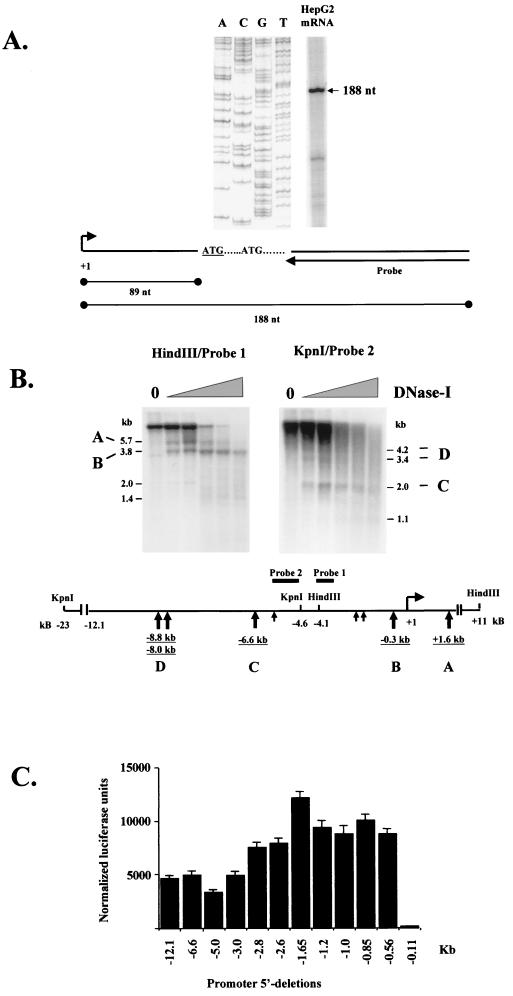

The transcriptional start site was determined by primer extension assay using a 26-nt end-labeled primer, which hybridizes 73 bp downstream of the first ATG codon. One major band of 188 bp was detected in HepG2 poly(A) RNA, which places the transcriptional start site 89 bp upstream of the first ATG codon (11) (Fig. 1A). To map the regions interacting with DNA-binding proteins, we performed DNase I-hypersensitive-site analysis. With probe 1 we could detect two major DNase I-hypersensitive sites: one at the proximal promoter region, about −300 bp from the transcriptional start site, while the second was located at the intronic region between exon 1b and exon 2, about 1.6 kb downstream of the transcriptional start site (Fig. 1B). With probe 2 we detected three major DNase I-hypersensitive sites at the far-upstream region, about −6.6, −8.0, and −8.8 kb from the transcriptional start site (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Functional mapping of the human HNF-4α upstream region. (A) Determination of the transcription start site by primer extension analysis using HepG2 poly(A) RNA. Arrow, oligonucleotide used for reverse transcription and the DNA sequencing reaction. The underlined ATG codon corresponds to the upstream translation initiation site proposed previously (11). (B) DNase I-hypersensitive-site analysis. HepG2 nuclei were treated with 0, 5, 10, 15, 17, and 20 U of DNase I, and genomic DNA was prepared and digested with HindIII (left) or KpnI (right). Indirect end labeling was performed with the indicated probes. The schematic shows the positions of the major hypersensitive sites relative to the transcription start site (large arrows). Small arrows, positions of minor DNase I-hypersensitive sites located at around −2.1, −2.7, and −5.6 kb from the transcriptional start site. (C) Promoter activity of the human HNF-4α upstream region in HepG2 cells. Bars, luciferase activities obtained with transfected constructs containing the full-length human HNF-4α gene, the region from kb −12.1 to bp +67 of the HNF-4α gene, and derivatives of HNF-4α with deletions of portions of the 5′ region (indicated by the 5′ nucleotide position) and normalized to β-galactosidase activities (internal control). Standard errors were calculated from four independent experiments.

To identify the minimal regulatory region of HNF-4α, we fused the 12.1-kb upstream sequence to a luciferase reporter and 5′ deletion derivatives of this clone were used in transient transfection assays with the human hepatoma-derived HepG2 cell line. As shown in Fig. 1C, mutants with 5′ deletions up to kb −0.56 had little effect on promoter activity. Since further deletions abolished promoter activity and since all constructs were inactive in the nonhepatic HeLa cell line, we concluded that the proximal promoter region of the HNF-4α gene contains all the important elements required for high levels of hepatic transcription in transient transfection assays.

Transcription factors binding to the proximal promoter region.

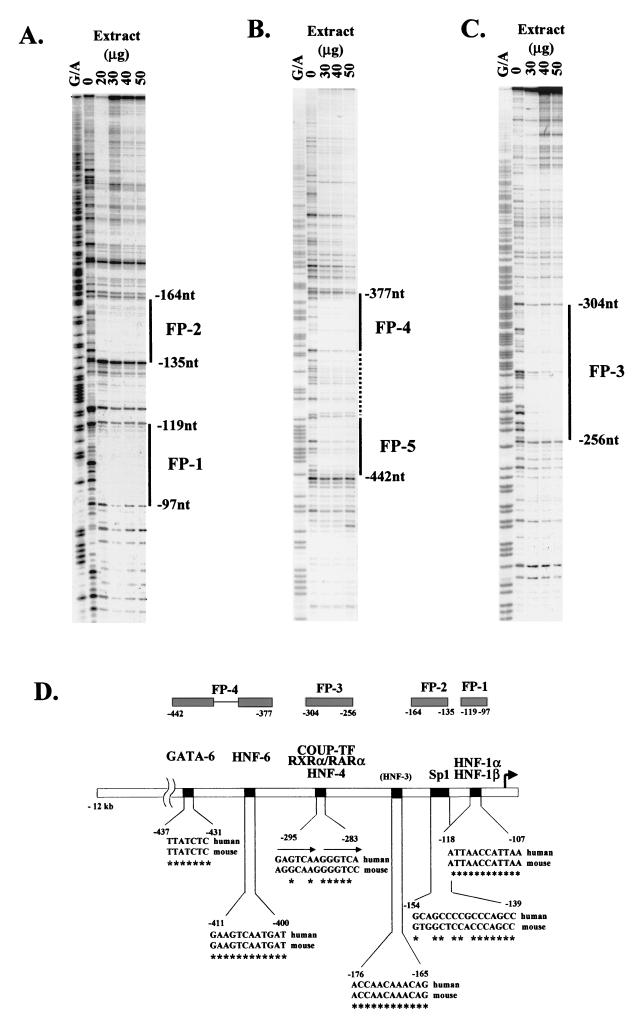

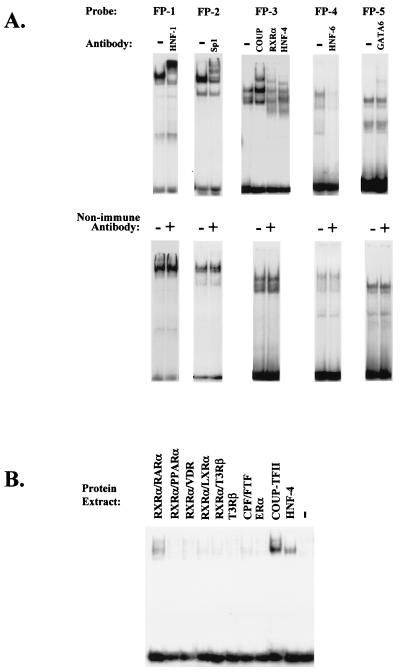

To identify transcription factor binding sites within this region, we performed in vitro DNase I footprint analysis. Five major DNase I-protected regions were detected with HepG2 nuclear extracts. Footprint 1 extends from bp −97 to −119, footprint 2 extends from bp −135 to −164, footprint 3 extends from bp −256 to −304, and footprints 4 and 5 extend from bp −377 to −442 (Fig. 2A to C). Careful inspection of the nucleotide sequences corresponding to the protected regions revealed that footprint 1, footprint 4, and footprint 5 contain canonical binding sites for HNF-1α and -β, HNF-6, and GATA-6, respectively, whose sequences are identical to the mouse promoter sequences (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, the region comprising nt −165 to −176, which resembles an HNF-3 binding site, was not protected. Sequence comparison of the mouse and human proximal-promoter region (nt −453 to +1; GenBank accession no. S77762 and NT_011382) by the Clustal W-1.5 multiple sequence alignment program revealed an overall identity of 68% with six gaps, while the sequences within the footprinted regions were 72% identical (data not shown). Sequence identity within the core binding motifs shown in Fig. 2D was 85%. Footprint 2, which contains a canonical Sp-1 binding site, is not conserved in the corresponding mouse promoter sequence. Footprint 3 contains direct repeat 1 (DR-1), which is a potential binding site for nuclear hormone receptors. This sequence is also different in the corresponding region of the mouse HNF-4α promoter (Fig. 2D). These differences point to potential species-specific variations with respect to the involvement of trans-acting factors in the regulation of the HNF-4α gene. To confirm the identity of the transcription factors that bind to the above footprinted regions, we performed antibody-mediated supershift assays. Antibodies against HNF-1, Sp-1, HNF-6, and GATA-6 were able to partially supershift or eliminate the complexes formed on FP-1-, FP-2-, FP-4-, and FP-5-derived double-stranded oligonucleotides, respectively (Fig. 3A). Complexes formed on the FP-3 probe were supershifted by COUP-TF, RXRα, and HNF-4α antibodies, suggesting that this element is a potential HRE. To test the potential association of other known nuclear hormone receptors with this element, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays with Cos-1 cellular extracts expressing RXRα-RARα, PPARα, VDR, LXRα, T3Rβ, CPF/FTF, COUP-TFII, and HNF-4α. Strong binding only by COUP-TFII was observed. A weaker but significant binding by RXRα-RARα and HNF-4α (Fig. 3B) was detected.

FIG. 2.

Identification of transcription factor binding sites in the proximal-promoter region of the human HNF-4α gene. In vitro DNase I footprint analysis was performed using 5′-end-labeled probes containing the nt −45 to −450 (A), the nt −503 to +67 (B), and the nt −194 to −595 (C) regions of the human HNF-4α promoter and the indicated amounts of HepG2 nuclear extracts. Lanes G/A, Maxam-Gilbert chemical sequencing ladders of the same probes. (D) Schematic presentation of the footprinted areas and comparison of their sequence motifs with the corresponding regions of the mouse HNF-4α promoter.

FIG. 3.

Identification of the main transcription factors associating with the proximal-promoter region of the human HNF-4α gene. (A) Electrophoretic mobility shift experiments were performed using rat liver nuclear extracts and labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides corresponding to the indicated footprinted regions. Incubations with antibodies and the binding reactions were performed on ice except for preincubations with anti-RXRα and anti-HNF-4α, which were done at room temperature. (B) Electrophoretic mobility shift experiments were performed with extracts from mock-transfected Cos-1 cells (−) and Cos-1 cells transfected with the indicated expression vectors and a labeled FP-3 probe.

Functional analysis of the proximal promoter region.

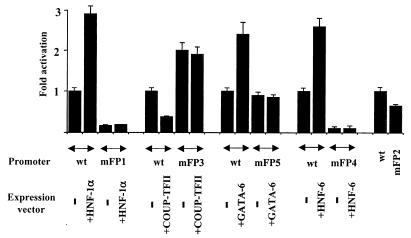

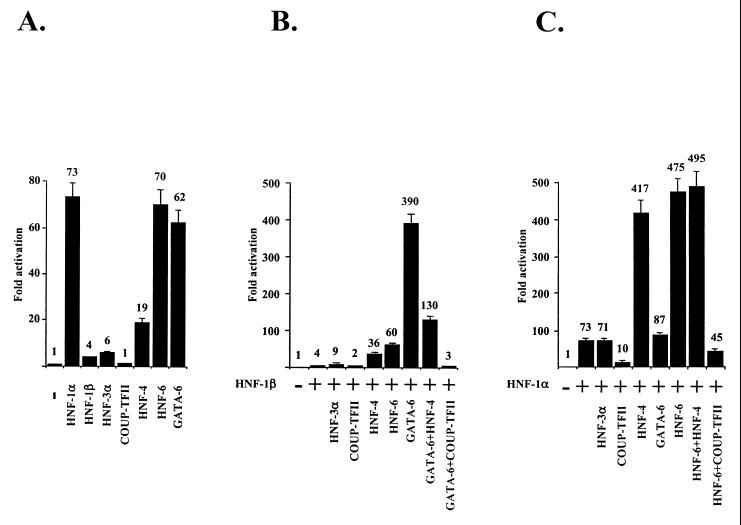

To ascertain the functional importance of the above cis elements and trans-acting factors, we introduced mutations into the individual footprinted regions that abolish the binding of the corresponding transcription factors. Transient transfection assays with HepG2 cells revealed that mutations in the HNF-1 (footprint 1), Sp-1 (footprint 2), and HNF-6 (footprint 4) binding sites reduced promoter activity to 17, 70, and 10%, respectively, of the wild-type value (Fig. 4). In contrast, mutation of the HRE region (footprint 3) led to approximately a twofold increase in promoter activity, while mutations at the GATA-6 (footprint 5) site had only a marginal effect on it. Overexpression of HNF-1α, HNF-6, or GATA-6 stimulated transcription from the wild-type promoter 2.9-fold, 2.6-fold, and 2.4-fold, respectively (Fig. 4). In contrast, overexpression of COUP-TFII inhibited the activity of the promoter to about 38% of wild-type levels. None of the factors affected the activity of the corresponding mutant constructs (Fig. 4). These data suggest that HNF-1α, Sp-1, and HNF-6 may act as essential positive regulators for the high-level transcription of the human HNF-4α gene in HepG2 cells, while COUP-TFII, through binding to the HRE, negatively regulates it. Although GATA-6 was able to transactivate the promoter, its function, at least in HepG2 cells, seems to be redundant, since disruption of its binding site did not change the activity of the promoter. Since HepG2 cells contain, endogenously, high levels of the above transcription factors, the relative degrees of transactivation and the potential synergistic effects between pairs of transcription factors are difficult to assess using this cell line. To overcome this problem, we performed the cotransfection experiments with HeLa cells, which do not express endogenous HNFs. Strong transactivations were observed by overexpression of HNF-1α, HNF-6, and GATA-6 (73-fold, 70-fold, and 62-fold, respectively) (Fig. 5A). HNF-1β-, HNF-3α-, and HNF-4α-dependent transactivations were less pronounced (4-fold, 6-fold, and 19-fold, respectively), while COUP-TFII overexpression, as expected, did not activate the promoter (Fig. 5A). As is evident up to this point, multiple factors have the potential to activate the HNF-4α promoter. This raised the question whether, as in most other complex regulatory regions, the simultaneous action of more than one factor may be required for high-level transcription of the HNF-4α gene. This was tested by analyzing the potential synergism of the above factors on the promoter. As shown in Fig. 5B, coexpression of HNF-1β and GATA-6 resulted in a transactivation far above the sum of the activations obtained by the individual factors (390-fold versus 4-fold plus 62-fold). Coexpression of the other factors with HNF-1β did not lead to strong synergistic effects. Interestingly, overexpression of HNF-4α resulted in reduction of the HNF-1β–GATA-6 synergism, and, as expected, overexpression of COUP-TFII abolished transcription (Fig. 5B). HNF-1α, however, did not exhibit any synergism with GATA-6, but it did so with HNF-6 or HNF-4α (475-fold versus 73-fold plus 70-fold and 417-fold versus 73-fold plus 19-fold, respectively) (Fig. 5C). Overexpression of all three factors did not lead to further enhancement, while overexpression of COUP-TFII inhibited transcription (Fig. 5C). These results point to the possibility of alternative transcription factor combinations in the formation of an active transcription initiation complex on the human HNF-4α promoter.

FIG. 4.

Functional analysis of the cis elements of the human HNF-4α promoter. HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with the region comprising nt −560 to +67 and containing the luciferase construct (wt) and its derivatives carrying internal mutations at the indicated footprinted regions (mFP1, mFP3, mFP5, mFP4, and mFP2). Where indicated, the cells were cotransfected with 500 ng of the corresponding expression vectors. Bars, mean values and standard errors of normalized luciferase activities from at least four independent experiments expressed as multiples of the activity obtained with the wild-type promoter.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of the synergism between transcription factors on the human HNF-4α promoter. (A) HeLa cells were cotransfected with 2 μg of DNA from the region comprising nt −560 to +67 and containing the luciferase reporter and 250 ng of the indicated expression vectors. (B and C) The cells were cotransfected with the indicated expression vectors together with 250 ng of the HNF-β or HNF-1α expression vector (+), respectively. Bars, mean values and standard errors of normalized luciferase activities from at least four independent rounds of experiments performed in duplicate with all samples and expressed as multiples of the activity obtained in transfections using the promoter-reporter alone (−). Note the different scale of the ordinate in panel A.

Recruitment of transcription factors on the HNF-4α promoter in HepG2 cells.

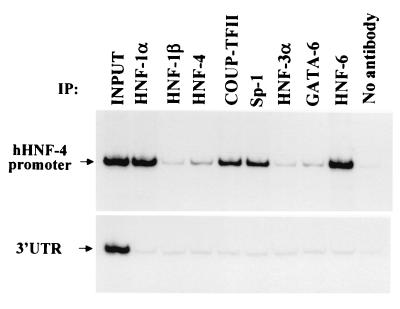

To verify the in vivo relevance of the data obtained by transient-transfection assays in the context of chromatin in intact cells, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments using the human hepatoma HepG2 cell line, which expresses HNF-4α at high levels. Antibodies raised against HNF-1α, HNF-6, COUP-TFII, and Sp-1 could efficiently and specifically immunoprecipitate the HNF-4α promoter DNA, suggesting stable in vivo association of these factors with the promoter (Fig. 6). On the other hand, we failed to detect promoter occupancy by HNF-1β, HNF-4α, HNF-3α, or GATA-6, in spite of the fact that, apart from HNF-1β, these factors are abundantly expressed in HepG2 cells (data not shown). Therefore, at least in HepG2 cells, HNF-4α transcription seems to be regulated by the combined action of HNF-1α, HNF-6, and Sp-1 and fine-tuned by the concomitant presence of COUP-TFII, which acts as a negative modulator.

FIG. 6.

Transcription factor recruitment to the human HNF-4α promoter in the context of chromatin in intact cells. Soluble chromatin from formaldehyde-fixed HepG2 cells was prepared and immunoprecipitated (IP) with antibodies to the indicated proteins. The DNAs in the immunoprecipitates were amplified using primers encompassing the proximal HNF-4α promoter (hHNF-4 promoter) or the 3′ UTR of the human HNF-4α gene. The autoradiographic image of the products separated on a 5% polyacrylamide gel is shown.

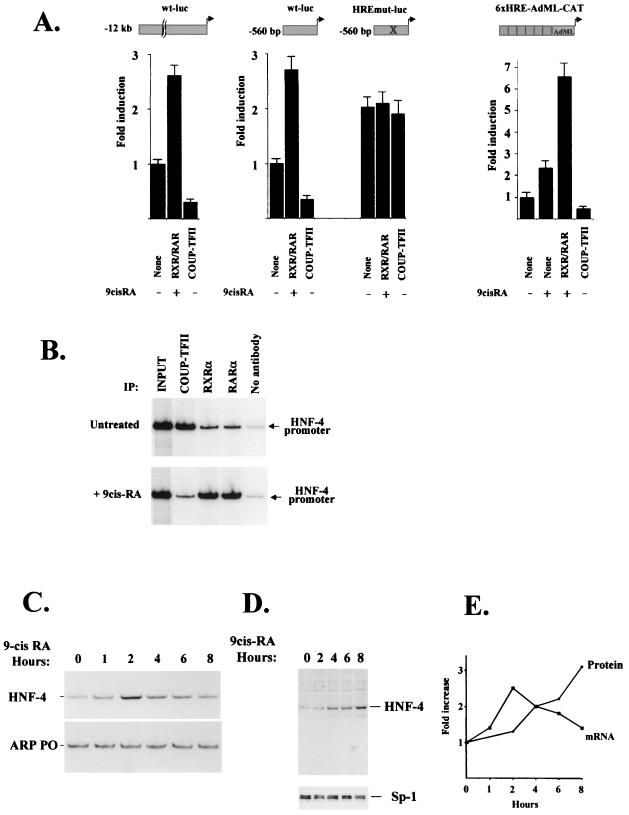

The retinoic acid signaling pathway positively affects human HNF-4α expression.

As shown above, the HRE sequence of footprint 3 can also associate with RXRα-RARα heterodimers. To test the functional relevance of this interaction, we asked whether overexpression of RXRα-RARα influences the activity of the human HNF-4α promoter in HepG2 cells. As shown in Fig. 7A, RXRα-RARα could induce the activity of both the full-length and the proximal (beginning 12.1 kb and 560 bp, respectively, upstream of the transcription start site)-promoter-containing reporters in a ligand-dependent manner. Similar induction was observed with a chimeric promoter construct containing six copies of the HNF-4α HRE sequence in front of the AdML minimal promoter. COUP-TFII antagonized this activation in all cases (Fig. 7A). When the HRE site was mutated, no retinoic acid-mediated activation was observed. The molecular basis for the COUP-TFII–RXRα-RARα antagonism could involve a competition of these factors for the HNF-4α HRE. To test this, we investigated the in vivo occupancy of the human HNF-4 promoter by these factors in untreated and retinoic acid-treated HepG2 cells. Differential occupancy of the promoter by COUP-TFII and RXRα or RARα in the majority of the cells was evident because the signal detected in COUP-TFII chromatin immunoprecipitates decreased after 2 h of retinoic acid treatment, with a concomitant increase of the signal in either RXRα or RARα immunoprecipitates (Fig. 7B). The above results suggested that the HNF-4α HRE is a bona fide retinoic acid response element and that HNF-4α expression may increase under certain physiological conditions. To verify this possibility in vivo, we treated HepG2 cells with 9-cis-retinoic acid and monitored the expression levels of HNF-4α by semiquantitative RT-PCR and Western blot analysis. A 2.5-fold increase in steady-state HNF-4α mRNA levels was observed; the level peaked around 2 h after treatment and then gradually decreased for the next 6 h (Fig. 7C and E). Interestingly, cellular HNF-4α protein levels continued to increase for up to 8 h (Fig. 7D and E), suggesting that, in addition to its involvement in transcriptional potentiation, 9-cis-retinoic acid may also act at a later step, possibly affecting HNF-4α protein stability.

FIG. 7.

Ligand-dependent activation of the human HNF-4α gene by RXRα-RARα in HepG2 cells.(A) HepG2 cells were grown in 10% dextran-coated charcoal-stripped fetal calf serum containing DMEM and transiently transfected with 2 μg of the indicated reporters and 500 ng of the indicated expression vectors. After transfection the cells were treated with 1 μM 9-cis-retinoic acid or left untreated for 36 h until harvest. Bars, mean values and standard errors of normalized luciferase activities from at least four independent experiments. (B) HepG2 cells, grown in stripped serum containing DMEM, were left untreated or treated with 1 μM 9-cis-retinoic acid for 2 h. Soluble chromatin from formaldehyde-fixed HepG2 cells was prepared and immunoprecipitated (IP) with antibodies to the indicated proteins. The DNAs in the immunoprecipitates were amplified using primers encompassing the proximal HNF-4α promoter (hHNF-4 promoter). The autoradiographic image of the products separated on a 5% polyacrylamide gel is shown. (C and D) HepG2 cells, grown in stripped serum containing DMEM, were treated with 1 μM 9-cis-retinoic acid for the indicated time periods. Total RNAs and nuclear extracts were prepared, and the expression of HNF-4α was analyzed by RT-PCR using human acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein as the control (C) or by Western blotting using a primary antibody against HNF-4α or an Sp-1 antibody as an internal control (D). (E) Relative HNF-4α mRNA and protein levels versus time after 9-cis-retinoic acid addition were plotted.

DISCUSSION

HNF-4α is a key member of the complex regulatory network that defines the hepatocyte phenotype (13, 18, 22, 24, 26, 48). The activity of HNF-4α has been shown to be regulated in a number of ways including posttranscriptional modifications, such as phosphorylation (19, 23, 50) or acetylation (44), as well as protein-protein interactions with other factors (9, 43, 44, 53). Further complexity in the control of HNF-4-dependent genes arises from the existence of several isoforms of HNF-4α generated by alternative splicing (6, 11, 21). HNF-4α expression is restricted to the liver, kidney, intestine, and pancreatic β cells, a pattern that is highly conserved among different species (12, 13). In addition to this restricted expression pattern, the hierarchical cascade of activation of hepatic transcription factors during early embryogenesis and the cross-regulatory pathways functioning in the adult liver point to the importance of HNF-4α regulation at the transcriptional level (13, 17, 18, 22, 24, 26, 48).

In this work we cloned the human HNF-4α regulatory region and analyzed it in a human hepatoma cell line. Several lines of evidence suggest that in HepG2 cells the human HNF-4α gene is mainly regulated by the synergistic action of two other liver-enriched transcription factors, HNF-1α and HNF-6. First, mutagenesis of either the HNF-1α or the HNF-6 binding site on the human HNF-4α promoter highly reduced its activity. Second, cotransfection of HNF-1α and HNF-6 resulted in high levels of synergistic activation. Third, immunoprecipitation of cross-linked HepG2 chromatin revealed that in vivo both factors are stably associated with the HNF-4α proximal promoter. Since HNF-4α is known to be an essential regulator of the HNF-1α gene, the effect of HNF-1α on the HNF-4α promoter is particularly interesting and points to a positive autoregulatory loop between these two factors. Previous studies of the mouse HNF-4α promoter have indicated a similar reciprocal relationship, and these studies have been further strengthened by studies of hepatoma cell variants (1, 3, 45, 46). Although HNF-1α seems to be essential for HNF-4α expression, it should not participate in the initial activation of the HNF-4α gene during early embryonic development, since HNF-4α expression precedes that of HNF-1α (5, 12, 14). What could then be the mechanism that turns on HNF-4α expression? Previous studies on HNF-1β null mice have indicated that HNF-1β, whose expression precedes that of HNF-4α, is essential for visceral endoderm differentiation (2, 8). HNF-1β−/− mice fail to express HNF-4α and HNF-1α, suggesting that it may be directly or indirectly involved in the initial activation of the HNF-4α gene (2, 8). We found that HNF-1β, which binds the same sequence motif as HNF-1α, poorly activated the human HNF-4α promoter in transfection assays. However, together with GATA-6, it produced a dramatic induction of transcription. Since disruption of the GATA-6 gene in mice results in a phenotype similar to that of the HNF-1β−/− mice (35), it seems possible that the initial activation of HNF-4α requires the combined action of GATA-6 and HNF-1β. Our promoter analysis demonstrates that both factors could be directly involved in HNF-4α activation, driving high levels of transcription by a synergistic mechanism.

Taken together, the results imply multiple pathways for the regulation of the HNF-4α gene. The synergistic action of HNF-1β and GATA-6 may be responsible for its initial activation, while at later stages of hepatocyte differentiation, when HNF-1α levels reach a critical threshold and HNF-1β expression gradually decreases, the promoter activity depends on the synergism between HNF-1α and HNF-6. In this respect HepG2 cells resemble differentiated hepatocytes, since they express HNF-1α at high levels but very little HNF-1β. According to this model, the actual balance of HNF-1α and HNF-1β levels in a given cell may play a determinative role in the composition of the transcription initiation complex formed on the HNF-4α promoter. This may explain why in adult HNF-1 null mice HNF-4α expression is not seriously affected, since these animals express elevated levels of HNF-1β, which may compensate for the loss of HNF-1α in certain promoters (38).

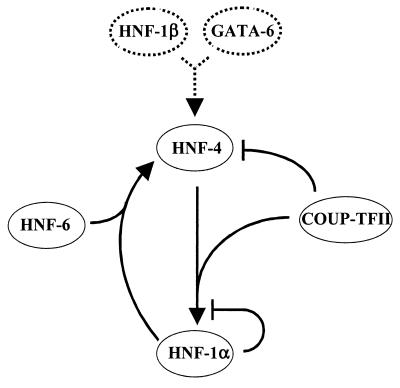

The existence of a reciprocal cross-regulation between HNF-1α and HNF-4α in hepatic cells raises some important concerns with respect to the control of the levels of these transcription factors in the cell. Once such a loop is established, it could be self-perpetuating, which may eventually lead to abnormally high intracellular quantities of the two factors. However, other regulatory events in the same circuit, schematically presented in Fig. 8, may prevent this. As shown in this study, a major member of this loop, COUP-TFII, negatively regulates HNF-4α expression. On the other hand COUP-TFII may increase HNF-1α transcription by potentiating HNF-4α activity via protein-protein interaction with its ligand-binding domain (25). Increased levels of HNF-1α inhibit its own transcription, again via protein-protein interaction with HNF-4α (24), which would prevent further activation of HNF-4α. Furthermore, efficient transactivation of the HNF-4α promoter by HNF-1 requires HNF-6, which may provide an additional control step. Thus, according to this model, the expression of HNF-1 and HNF-4α is strictly controlled by multiple interdependent regulatory pathways, securing balanced levels of HNF-1 and HNF-4α in the cell.

FIG. 8.

Schematic representation of the positive (pointed arrows) and negative (flat-headed arrows) effects in the proposed regulatory network. Dashed and solid arrows indicate alternative activation mechanisms.

Although, as discussed so far, one could assign biological significance to the HNF-1α–HNF-6 and HNF-1β–GATA-6 synergism, the available data are insufficient to explain the potential biological role of the observed direct positive effect of HNF-4α itself on its own promoter. HNF-4α could synergize with HNF-1α but not with HNF-1β, while it inhibited HNF-1β–GATA-6-dependent activation. It is tempting to speculate that the last effect may relate to a signal that switches the HNF-1β–GATA-6 complex to the HNF-1α–HNF-6 complex on the HNF-4α promoter once HNF-4α expression and consequently HNF-1α expression reached a critical level. The possibility that HNF-4α can directly autoregulate its own expression in HNF-1α-expressing cells, however, remains to be demonstrated. At least in HepG2 cells, which express both factors at high levels, no such direct autoregulation is evident. HNF-4α was not found to be associated with the promoter in vivo, and mutagenesis of its binding site increased, rather than decreased, promoter activity. Perhaps such a mechanism might function only in cell types expressing low levels of HNF-6.

A recent study indicated the potential involvement of a novel orphan nuclear receptor (CPF/FTF) in the regulation of the HNF-4α promoter (37). This factor was shown to be able to bind to and weakly transactivate the mouse HNF-4α proximal-promoter region (37). However, both of the two potential binding sites, positioned at nt −250 and −321, are located outside of the footprinted regions in the human promoter and only one of them (that at nt −250) is partially conserved. In addition, we could not observe CPF/FTF-mediated transactivation of the human promoter in HepG2 or HeLa cells (data not shown). Although we cannot entirely exclude a possible role for this factor in the activation of the human HNF-4α gene, it seems likely that, if it is involved, it may act as a “competence factor” rather than a major activator, in analogy to its function on the CYP7A1 promoter (33).

Comparison of the human and mouse HNF-4α proximal-promoter sequences revealed some fundamental differences. Although the core binding sites for HNF-1α and -β, HNF-6, and GATA-6 were identical, the human promoter contained two additional cis elements of functional importance. The first is a binding site for Sp-1, which is occupied in vivo by this factor, and the second is DR-1, a common binding motif for nuclear hormone receptors. This element can bind HNF-4α, COUP-TFII, and the retinoic acid receptors RXRα-RARα. Our results suggest that this region represents a negative regulatory element in HepG2 cells. COUP-TFII binding is responsible for this negative effect. On the other hand, binding of RXRα-RARα to this region leads to ligand-dependent activation of the promoter. As demonstrated in this study, the molecular basis for this antagonistic effect involves a retinoic acid-mediated exchange of occupancy of the HNF-4α HRE by these two factors. The physiological relevance of this finding is highlighted by the increase of HNF-4α expression in HepG2 cells upon short-term retinoic acid treatment. Interestingly, the kinetics of the retinoic acid-induced increases in HNF-4α mRNA and protein levels were distinct. Steady-state HNF-4α mRNA levels were initially increased up to 2 h after treatment; this was followed by a decrease to close to the initial levels. In contrast, HNF-4α protein levels steadily increased up to 8 h. This suggests that, in addition to affecting direct transcriptional activation, the retinoic acid signaling pathway may affect HNF-4 protein stability. The mechanism for such stabilization is unknown. A direct ligand effect can be excluded, since retinoids are not ligands for HNF-4α. We speculate that the involvement of retinoic acid-induced protein kinase cascades in this phenomenon is a more likely mechanism, since HNF-4α is a phosphoprotein (19, 23, 50). Supporting our results on the role of retinoic acid signaling in HNF-4α expression is the recent finding that long-term (72-h) retinoic acid treatment of Hep3B cells, which leads to downregulation of RXRα, decreased HNF-4α mRNA (34, 40). The positive influence of a well-characterized signaling pathway on human HNF-4α expression may provide the molecular basis for the design of novel therapeutic-intervention protocols to combat diseases caused by low HNF-4α expression levels. Such a disease is maturity onset diabetes of the young 1, a diabetic syndrome, which, according to the current view, is causally related to HNF-4α haploinsufficiency due to heterozygous mutations of the HNF-4α gene (52).

In summary, our results demonstrate that in cultured hepatoma cells the regulation of human HNF-4α depends on the interplay of positive and negative transcription factors. Transcriptional activation is achieved by the synergistic action of alternative sets of factors (HNF-1β–GATA-6 or HNF-1α–HNF-6), which may act sequentially during early hepatocyte specification and subsequent differentiation. In HepG2 cells, the concomitant action of positive regulators (HNF-1α and HNF-6) and COUP-TFII, which acts as a repressor, determines the actual rate of transcription from this gene. The repressive effect of COUP-TFII may be alleviated by liganded RXRα-RARα acting via competition for the same binding site and increasing HNF-4α expression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to A. Aranda, S. Cereghini, P. Chambon, R. Cortese, R. Costa, T. Evans, F. Lemaigre, D. Mangelsdorf, and M. Parker for providing the indicated reagents. We are grateful to N. Katrakili for expert technical assistance, C. Mamalaki for advice with HS analysis, E. Soutoglou and K. Boulias for helpful discussions, G. Keszler for critical reading of the manuscript, and an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments.

This work was supported by funds from the Greek General Secretariat for Science and Technology, by HFSP RGP-0024, and by EU HPRN-CT-2000-00087 programs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailly A, Spath G, Bender V, Weiss M C. Phenotypic effects of the forced expression of HNF4 and HNF1alpha are conditioned by properties of the recipient cell. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2411–2421. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.16.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbacci E, Reber M, Ott M O, Breillat C, Huetz F, Cereghini S. Variant hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 is required for visceral endoderm specification. Development. 1999;126:4795–4805. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.21.4795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bulla G A. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-4 prevents silencing of hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 expression in hepatoma x fibroblast cell hybrids. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2501–2508. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.12.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler A J, Parker M G. COUP-TF II homodimers are formed in preference to heterodimers with RXR alpha or TR beta in intact cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4143–4150. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.20.4143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cereghini S, Ott M O, Power S, Maury M. Expression patterns of vHNF1 and HNF1 homeoproteins in early postimplantation embryos suggest distinct and sequential developmental roles. Development. 1992;116:783–797. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.3.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chartier F L, Bossu J P, Laudet V, Fruchart J C, Laine B. Cloning and sequencing of cDNAs encoding the human hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 indicate the presence of two isoforms in human liver. Gene. 1994;147:269–272. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W S, Manova K, Weinstein D C, Duncan S A, Plump A S, Prezioso V R, Bachvarova R F, Darnell J E. Disruption of the HNF-4 gene, expressed in visceral endoderm, leads to cell death in embryonic ectoderm and impaired gastrulation of mouse embryos. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2466–2477. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.20.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffinier C, Thepot D, Babinet C, Yaniv M, Barra J. Essential role for the homeoprotein vHNF1/HNF1beta in visceral endoderm differentiation. Development. 1999;126:4785–4794. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.21.4785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dell H, Hadzopoulou-Cladaras M. CREB-binding protein is a transcriptional coactivator for hepatocyte nuclear factor-4 and enhances apolipoprotein gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9013–9021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.9013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Simone V, De Magistris L, Lazzaro D, Gerstner J, Monaci P, Nicosia A, Cortese R. LFB3, a heterodimer-forming homeoprotein of the LFB1 family, is expressed in specialized epithelia. EMBO J. 1991;10:1435–1443. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07664.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drewes T, Senkel S, Holewa B, Ryffel G U. Human hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 isoforms are encoded by distinct and differentially expressed genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:925–931. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan S A, Manova K, Chen W S, Hoodless P, Weinstein D C, Bachvarova R F, Darnell J E. Expression of transcription factor HNF-4 in the extraembryonic endoderm, gut, and nephrogenic tissue of the developing mouse embryo: HNF-4 is a marker for primary endoderm in the implanting blastocyst. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7598–7602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duncan S A, Navas M A, Dufort D, Rossant J, Stoffel M. Regulation of a transcription factor network required for differentiation and metabolism. Science. 1998;281:692–695. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5377.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duncan S A. Transcriptional regulation of liver development. Dev Dyn. 2000;219:131–142. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::aid-dvdy1051>3.3.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao X, Sedgwick T, Shi Y B, Evans T. Distinct functions are implicated for the GATA-4, -5, and -6 transcription factors in the regulation of intestine epithelial cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2901–2911. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaub M P, Rochette-Egly C, Lutz Y, Ali S, Matthes H, Scheuer I, Chambon P. Immunodetection of multiple species of retinoic acid receptor alpha: evidence for phosphorylation. Exp Cell Res. 1992;201:335–346. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90282-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayhurst G P, Lee Y H, Lambert G, Ward J M, Gonzalez F J. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (nuclear receptor 2A1) is essential for maintenance of hepatic gene expression and lipid homeostasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1393–1403. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1393-1403.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holewa B, Strandmann E P, Zapp D, Lorenz P, Ryffel G U. Transcriptional hierarchy in Xenopus embryogenesis: HNF4 a maternal factor involved in the developmental activation of the gene encoding the tissue specific transcription factor HNF1 alpha (LFB1) Mech Dev. 1996;54:45–57. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang G, Nepomuceno L, Yang Q, Sladek F M. Serine/threonine phosphorylation of orphan receptor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;340:1–9. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.9914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jimenez-Lara A M, Aranda A. Lysine 246 of the vitamin D receptor is crucial for ligand-dependent interaction with coactivators and transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13503–13510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kritis A A, Argyrokastritis A, Moschonas N K, Power S, Katrakili N, Zannis V I, Cereghini S, Talianidis I. Isolation and characterization of a third isoform of human hepatocyte nuclear factor 4. Gene. 1996;173:275–280. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kritis A A, Ktistaki E, Barda D, Zannis V I, Talianidis I. An indirect negative autoregulatory mechanism involved in hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5882–5889. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.25.5882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ktistaki E, Ktistakis N T, Papadogeorgaki E, Talianidis I. Recruitment of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 into specific intranuclear compartments depends on tyrosine phosphorylation that affects its DNA-binding and transactivation potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9876–9880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ktistaki E, Talianidis I. Modulation of hepatic gene expression by hepatocyte nuclear factor 1. Science. 1997;277:109–112. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ktistaki E, Talianidis I. Chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factors act as auxiliary cofactors for hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 and enhance hepatic gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2790–2797. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuo C J, Conley P B, Chen L, Sladek F M, Darnell J E, Jr, Crabtree G R. A transcriptional hierarchy involved in mammalian cell-type specification. Nature. 1992;355:457–461. doi: 10.1038/355457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ladias J A, Karathanasis S K. Regulation of the apolipoprotein AI gene by ARP-1, a novel member of the steroid receptor superfamily. Science. 1991;251:561–565. doi: 10.1126/science.1899293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lahooti H, White R, Danielian P S, Parker M G. Characterization of ligand-dependent phosphorylation of the estrogen receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:182–188. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.2.8170474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai E, Prezioso V R, Smith E, Litvin O, Costa R H, Darnell J E. HNF-3A, a hepatocyte-enriched transcription factor of novel structure is regulated transcriptionally. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1427–1436. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.8.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landry C, Clotman F, Hioki T, Oda H, Picard J J, Lemaigre F P, Rousseau G G. HNF-6 is expressed in endoderm derivatives and nervous system of the mouse embryo and participates to the cross-regulatory network of liver-enriched transcription factors. Dev Biol. 1997;192:247–257. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lemaigre F P, Durviaux S M, Truong O, Lannoy V J, Hsuan J J, Rousseau G G. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 6, a transcription factor that contains a novel type of homeodomain and a single cut domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9460–9664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li J, Ning G, Duncan S A. Mammalian hepatocyte differentiation requires the transcription factor HNF-4alpha. Genes Dev. 2000;14:464–474. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu T T, Makishima M, Repa J J, Schoonjans K, Kerr T A, Auwerx J, Mangelsdorf D J. Molecular basis for feedback regulation of bile acid synthesis by nuclear receptors. Mol Cell. 2000;6:507–515. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magee T R, Cai Y, El-Houseini M E, Locker J, Wan Y J. Retinoic acid mediates down-regulation of the alpha-fetoprotein gene through decreased expression of hepatocyte nuclear factors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30024–30032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.30024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morrisey E E, Tang Z, Sigrist K, Lu M M, Jiang F, Ip H S, Parmacek M S. GATA6 regulates HNF4 and is required for differentiation of visceral endoderm in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3579–3590. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orlando V, Strutt H, Paro R. Analysis of chromatin structure by in vivo formaldehyde cross-linking. Methods. 1997;11:205–214. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pare J F, Roy S, Galarneau L, Belanger L. The mouse fetoprotein transcription factor (ftf) gene promoter is regulated by three gata elements with tandem e box and nkx motifs, and ftf in turn activates the hnf3beta, hnf4alpha, and hnf1alpha gene promoters. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13136–13144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pontoglio M, Barra J, Hadchouel M, Doyen A, Kress C, Bach J P, Babinet C, Yaniv M. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 inactivation results in hepatic dysfunction, phenylketonuria, and renal Fanconi syndrome. Cell. 1996;84:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price J A, Fossey S C, Sale M M, Brewer C S, Freedman B I, Wuerth J P, Bowden D W. Analysis of the HNF4 alpha gene in Caucasian type II diabetic nephropathic patients. Diabetologia. 2000;43:364–372. doi: 10.1007/s001250050055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qian A, Cai Y, Magee T R, Wan Y J. Identification of retinoic acid-responsive elements on the HNF1alpha and HNF4alpha genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:837–842. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rich B E, Steitz J A. Human acidic ribosomal phosphoproteins P0, P1, and P2: analysis of cDNA clones, in vitro synthesis, and assembly. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:4065–4074. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.11.4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sladek F M, Zhong W M, Lai E, Darnell J E. Liver-enriched transcription factor HNF-4 is a novel member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2353–2365. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sladek F M, Ruse M D, Nepomuceno L, Huang S M, Stallcup M R. Modulation of transcriptional activation and coactivator interaction by a splicing variation in the F domain of nuclear receptor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α1. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6509–6522. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soutoglou E, Katrakili N, Talianidis I. Acetylation regulates transcription factor activity at multiple levels. Mol Cell. 2000;5:745–751. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spath G F, Weiss M C. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 expression overcomes repression of the hepatic phenotype in dedifferentiated hepatoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1913–1922. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spath G F, Weiss M C. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 provokes expression of epithelial marker genes, acting as a morphogen in dedifferentiated hepatoma cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:935–946. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taraviras S, Monaghan A P, Schutz G, Kelsey G. Characterization of the mouse HNF-4 gene and its expression during mouse embryogenesis. Mech Dev. 1994;48:67–79. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tian J M, Schibler U. Tissue-specific expression of the gene encoding hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 may involve hepatocyte nuclear factor 4. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2225–2234. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12a.2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tolon R M, Castillo A I, Aranda A. Activation of the prolactin gene by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha appears to be DNA binding-independent. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26652–26661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Viollet B, Kahn A, Raymondjean M. Protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation modulates DNA-binding activity of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4208–4219. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willy P J, Umesono K, Ong E S, Evans R M, Heyman R A, Mangelsdorf D J. LXR, a nuclear receptor that defines a distinct retinoid response pathway. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1033–1045. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.9.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamagata K, Furuta H, Oda N, Kaisaki P J, Menzel S, Cox N J, Fajans S S, Signorini S, Stoffel M, Bell G I. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha gene in maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY1) Nature. 1996;384:458–460. doi: 10.1038/384458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshida E, Aratani S, Itou H, Miyagishi M, Takiguchi M, Osumu T, Murakami K, Fukamizu A. Functional association between CBP and HNF4 in trans-activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;241:664–669. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhong W, Mirkovitch J, Darnell J E. Tissue-specific regulation of mouse hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7276–7284. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]