IMPORTANCE:

Moral distress is common among critical care physicians and can impact negatively healthcare individuals and institutions. Better understanding inter-individual variability in moral distress is needed to inform future wellness interventions.

OBJECTIVES:

To explore when and how critical care physicians experience moral distress in the workplace and its consequences, how physicians’ professional interactions with colleagues affected their perceived level of moral distress, and in which circumstances professional rewards were experienced and mitigated moral distress.

DESIGN:

Interview-based qualitative study using inductive thematic analysis.

SETTING AND PARTICIPANTS:

Twenty critical care physicians practicing in Canadian ICUs who expressed interest in participating in a semi-structured interview after completion of a national, cross-sectional survey of moral distress in ICU physicians.

RESULTS:

Study participants described different ways to perceive and resolve morally challenging clinical situations, which were grouped into four clinical moral orientations: virtuous, resigned, deferring, and empathic. Moral orientations resulted from unique combinations of strength of personal moral beliefs and perceived power over moral clinical decision-making, which led to different rationales for moral decision-making. Study findings illustrate how sociocultural, legal, and clinical contexts influenced individual physicians’ moral orientation and how moral orientation altered perceived moral distress and moral satisfaction. The degree of dissonance between individual moral orientations within care team determined, in part, the quantity of “negative judgments” and/or “social support” that physicians obtained from their colleagues. The levels of moral distress, moral satisfaction, social judgment, and social support ultimately affected the type and severity of the negative consequences experienced by ICU physicians.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE:

An expanded understanding of moral orientations provides an additional tool to address the problem of moral distress in the critical care setting. Diversity in moral orientations may explain, in part, the variability in moral distress levels among clinicians and likely contributes to interpersonal conflicts in the ICU setting. Additional investigations on different moral orientations in various clinical environments are much needed to inform the design of effective systemic and institutional interventions that address healthcare professionals’ moral distress and mitigate its negative consequences.

Keywords: decision making, ethics, job satisfaction, morals, professionalism, psychological distress

KEY POINTS

Question: How Canadian critical care physicians experience and respond to morally challenging clinical situations?

Findings: Physicians’ moral orientation or preferred approach to morally challenging clinical situations is a key mediator of moral wellbeing in critical care environments. Moral orientations (including the virtuous, resigned, deferring, and empathic types) vary among individuals, contexts, and over time and impact team interactions in positive or negative ways.

Meanings: Diversity in moral orientations may explain, in part, the variability in moral distress levels among clinicians and likely contributes to interpersonal conflicts in the ICU setting.

Moral distress is experienced by healthcare professionals who are unable, because of internal or external constraints, to act according to their own moral choices and professional integrity (1–3). Moral distress is a rampant problem that has been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (4–6). First described by Jameton (1) in 1984, moral distress has since been the object of considerable theoretical and empirical research (7, 8). Moral distress is associated with, but also distinct from, other negative indicators of wellness among healthcare professionals (e.g., burnout, compassion fatigue) (2, 9, 10). Multiple reviews have described the epidemiology, causes, subjective experiences, and consequences of moral distress (2, 7, 8, 11–13). Moral distress is more frequently reported among nurses; in acute care settings such as the critical care unit (ICU); in women, and in certain cultures (2, 7, 8). Clinical situations that incite moral distress include nonbeneficial and aggressive treatments provided at the end of life, deceptive or inappropriate care provided by colleagues, and unsafe or understaffed working conditions (7, 10). Many of these situations are related to organizational factors (e.g., nurse-physician relationships, institutional ethical climate, etc.) (2, 8).

Moral distress has been shown to impact physical and psychological wellbeing and is associated with gaps in clinical practice and workforce attrition (12, 14). Moral distress threatens the safety and quality of patient and family care when it results in clinicians displaying avoidant behaviors, negative social judgments, and detached care (12). There are also positive effects of moral distress, such as personal positive growth and increase in moral resilience (15).

Despite extensive research, many aspects of moral distress continue to be poorly understood. Levels of moral distress vary significantly within and across professions (2, 9, 10). The factors explaining this variation are mostly unknown (2). A potential source of inter-individual variability in levels of moral distress is an healthcare professional’s moral orientation, a concept which importance emerged during this study. Moral orientation was first described in 1976 by Kohlberg (16), who argued that “justice” was the fundamental principle of morality (17). Moral decision-making based on a justice orientation involves adjudicating between competing rights (18). Gilligan (19) challenged this view and argued that women typically make moral decisions based on a moral orientation of “care,” which focuses on interpersonal connectedness and maintenance of relationships. A “care” orientation involves emotional engagement and an attempt to simultaneously fulfill competing responsibilities (18). Subsequent studies presented conflicting results about gender differences in moral orientation (20–22) and also suggested that moral orientation differs between healthcare professions (even when controlling for gender); nurses more commonly embrace a moral orientation of “care,” compared with physicians (23). Moral orientation has also been associated with individual factors (e.g., personal motivations) and cultural values (18, 24).

Other aspects of moral distress offer rich opportunities for exploration. For example, moral distress has been studied mostly in nurses (7, 8, 10). Comparatively, little data exist to characterize the prevalence and consequences of moral distress in physicians, especially ICU physicians (9, 25, 26). Even less progress has been made in developing and testing interventions that effectively address moral distress in healthcare professionals. Poor understanding of the complex interactions among healthcare systems, clinical contexts, and the individual and organizational determinants of wellness are likely contributing factors (2, 8, 27–30). Therefore, we conducted a qualitative study to gain an in-depth understanding of moral distress in practicing critical care physicians. We initially sought to explore broadly, when and how critical care physicians experience moral distress in the workplace and its consequences, and then further focused our inquiry on various individual approaches commonly used by ICU physicians to address morally challenging situations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This interview-based qualitative study used a pragmatic approach, which prioritizes the concrete and practical implications of new knowledge rather than its objective truth. The value of theories and hypotheses are evaluated based on their results in practice (31). This study focuses on practicing critical care physicians in Canada and their experience of moral distress in their workplace. Ultimately, we aimed to generate knowledge that can inform the design of effective interventions that improve critical care healthcare professionals’ wellbeing and patient care.

Research Team

The research team included five members (three females, two males) who had different backgrounds, levels of training, and experiences. Four team members are critical care practicing physicians who acknowledged having experienced moral distress in their workplace. All researchers had research interest in health professional wellbeing. Two of the investigators (D.P., A.J.S.) are medical education researchers. A fifth co-investigator (F.C.) is a nurse, psychologist, and ethicist working in a pediatric clinical environment.

Participants, Setting, and Sampling

We recruited 20 of 25 ICU physicians (80%) who expressed interest in participating in a semi-structured interview after completion of a national, cross-sectional survey of moral distress and wellness in ICU physicians (9). In the full cohort of 225 survey respondents, most were male (70%), married (74%), and English (vs French) speaking (89%). They predominantly worked in teaching hospitals (86%) and in adult ICUs (83%), and completed, on average, 15 weeks of ICU clinical work in the year before the survey (pre-COVID-19 pandemic). We used a combination of convenience and purposive sampling (maximum variation) to select participants. We sent the initial interview invitation to survey respondents of different gender, different levels of experience, and different levels of moral distress (as identified from the survey results). Subsequent sampling was also theoretical (e.g., approaching additional senior physicians to further explore evolving moral orientation over a career), within the limitation of the number of survey respondents who had replied to the interview invitation. The final sample size was determined by thematic saturation, which was reached after interviewing 20 of the 25 potential participants. The Providence Healthcare Institute Office of Research Services reviewed and approved the study “Qualitative Study of Canadian Intensivists about Moral Distress and Burnout” on February 19, 2019 (UBC REB No. H19-00147). All study procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional or regional) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Interviews

Interested physicians were initially contacted by email and subsequently by telephone to obtain consent and conduct the interview. All semi-structured interviews were conducted in English by two research assistants, who had extensive experience in qualitative interviewing. Qualitative analysis of free-text written comments made by 131 survey respondents informed the semi-structured interview guide (32), which mostly focused on relational factors involved in moral distress, professional rewards experienced by our participants, and negative consequences of moral distress. Interview recordings were professionally transcribed verbatim into de-identified transcripts for analysis. We made iterative changes (e.g., added questions about perceived work-related rewards) to the original interview guide based on initial analyses.

Data Analysis

We first conducted an inductive thematic analysis of the interview transcripts (33). One investigator (D.P.) and a research assistant independently read the full text of initial interviews, before proceeding with line-by-line coding. Codes were then compared and categorized by topics. Any discrepancy between codes was resolved through discussion. Emerging themes within and across categories were elaborated by using constant comparisons between clinical examples within an interview and across participants. Once a preliminary coding scheme was developed, additional thematic elaboration was discussed through regular meetings among investigators to consider alternative interpretations and further refine the analytical framework (researcher triangulation). We kept analytical memos as an audit trail, and the analysis was mindful of the researchers’ own positions (34). The final coding schema was applied to all the transcripts. We used NVivo10 software (QSR International Pty Ltd, Australia) for the storage and management of the data.

During our analysis, we started noticing across interviews recurrent individual patterns or approaches used by physicians to deal with morally challenging situations. We initially called this theme “physicians guiding principles/approaches to morally challenging situations,” until one of our co-principal investigators (F.C.) proposed the term “moral orientation” to label this theme. Our choice of the word “orientation” was initially made based on its general meaning, that is, “the particular ways that a person prefers, believes, thinks, or usually does,” or a “natural tendency to do something in a certain way.” We then realized the existence of a similar concept in the literature, which we decided to further explore for our discussion. At that time, our coding scheme was already established. Because our concept of “moral orientation” was similar in many ways to the one already described in the literature, we kept the same term and focused our discussion on highlighting the commonalities and points of divergence between the existing and our proposed perspectives on moral orientation.

RESULTS

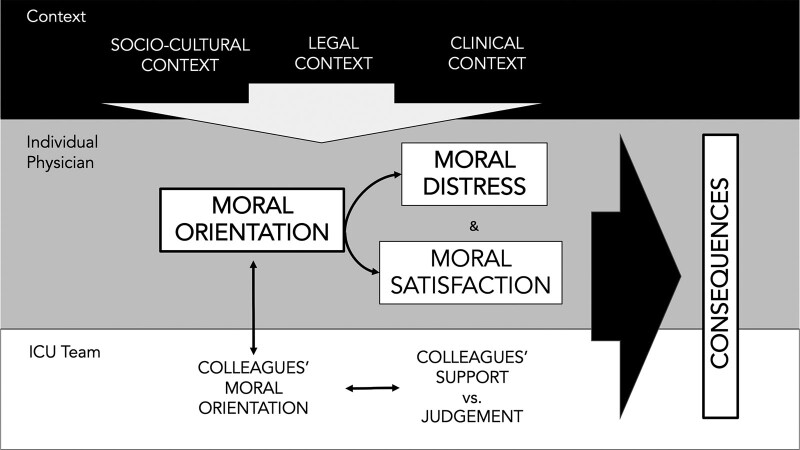

Interviews were conducted between May 2019 and December 2019, and interview duration ranged from 17 minutes to 1 hour and 29 minutes (mean: 63 min). Of the 20 participating critical care physicians, 14 (70%) were male, 17 (85%) were adult intensivists, 15 (75%) were working in teaching hospitals, 18 had a spouse (90%), and 9 (45%) lived with young children. Study participants described different approaches to perceiving and resolving morally challenging clinical situations, which we grouped into four types of clinical moral orientation. We first present the types of clinical moral orientation and the individual factors contributing to their development. Then, we explain how contextual factors (external to the individuals) also influence the choice and development of moral orientations. Next, we describe reported relationships between moral orientations and moral distress and sense of reward. Finally, we illustrate how the level of homogeneity of moral orientations within a care team (inter-individual factor) affects the level of support perceived by physicians (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Role of moral orientation in critical care physicians’ moral distress and its consequences. Sociocultural, legal, and clinical contexts dynamically affected individual physicians’ moral orientation, which acted as a key determinant of perceived moral distress and moral satisfaction in the clinical environment. Variable individual moral orientations within care teams contribute to negative interactions between physicians and their colleagues. Imbalances in the levels of moral distress and moral satisfaction, combined to the nature of the interactions with their colleagues determined, in part, the consequences of dealing with morally challenging for ICU physicians.

Moral Orientations: Four Individual Approaches to Morally Challenging Situations

Moral orientations relied on different underpinnings for moral decision-making, and resulted from unique combinations of strength of personal moral beliefs and perceived power over moral clinical decision-making (Table 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B151).

A “virtuous moral orientation” was characterized by firm personal beliefs on the morality of decisional choices available in morally challenging clinical situations (what is “right” or “wrong”), combined with the perceived capacity to act according to one’s values. Moral decision-making was based on a perceived sense of “justice” for the society or for the patient.

I have a hard time thinking of a time when I did something that I thought was immoral because I won’t do that. I know that makes me different than the colleagues that I work with, but I put my foot down many, many, many times and, so far, nobody has called me on it. [P7]

A “resigned moral orientation” was also characterized by strong personal beliefs regarding what was morally right or wrong in a given clinical situation, but lack the perceived power to act in accordance with these beliefs. Moral decision-making was thus based on the avoidance of negative consequences associated with morally challenging clinical situations.

[…] I mean, this patient is like dead in the bed. That’s all I can say to you. This patient is like a dead baby on a ventilator. There’s no conversation after that. Once you see this, you’re like, this is not right. Then, I think, the distress flows (flows) from that when parents don’t see it, they don’t understand that conversation, they don’t see the obvious consequences of that. Then, you get the logistics as well. So, even though there’s the internal distress, there’s also the distress that’s created every day when this patient is taking up bed space and nursing time and we’re refusing patients that are unwell. Now, that’s just the way it is, we’ve accepted that as well. […] This is an extreme case, that feels the patient, it may not be in the best interest to be there. It’s definitely not in the best interest of the system. So, you feel helpless. You feel powerless to make decisions. [P10]

A “deferring moral orientation” was based on an open-mindedness toward others’ moral views and the belief that one’s own moral judgment of a situation was irrelevant to clinical moral decision-making. This orientation was also defined by a feeling of disempowerment regarding clinical moral decisions because of current contextual factors, such as societal expectations. Moral decisions were thus made based on others’ beliefs (most often patient or patient surrogates’ beliefs).

There was also an implicit [understanding] that if the family insisted on interventions, I would absolutely proceed with that, taking their definition of futility and not mine, into account. […] And while there was an option of objecting to it on the basis of what I believed was potentially more indicated decisions, in my view the moral distress of a physician who doesn’t think that their views are aligned with patients’ best interests is irrelevant. Because what is relevant is what patients think about his or her best interests. And if the patient cannot think, what the people closest to that person think. [P1]

An “empathic moral orientation” also relied on relativist views of moral judgments (different moral decisions may be valuable/justifiable), with careful consideration of others’ moral beliefs. However, in contrast to the deferring orientation, the empathic approach to morally challenging clinical situations was based on active involvement in a negotiation process between all those involved to reach a consensus on morally sounded decisions.

For myself, as long as I can understand the reasons behind it and just be open to what people are telling me, then I’m fine with it. It wouldn’t be my choice, but I get it. I can try to understand what makes them operate. Those sorts of situations are fairly frequent, and I don’t find them particularly distressing. I just say to myself, well, I need to do more work. I need to sit down and listen to the family more closely and find out what makes them tick. Maybe they’re afraid of something. Maybe there’s something else going on. [P11]

Impact of Contexts on Moral Orientation

Although participants reported having a preferred approach to various morally challenging clinical situations, “moral orientation” was also “adaptive,” as physicians’ moral decision-making could be influenced by changing sociocultural and clinical contexts (specific patient’s or family’s clinical circumstances). In addition, moral orientation was not described as a fixed individual characteristic and could evolve over the course of one’s career.

So, we do not practice in silos, there is clearly an institutional culture which considers what is right and what is wrong or at least in the range within which we move. And there is no doubt when we influence each other. [P1]

… so I’m going to introduce the difficult situation to the family and I’m going to see how they respond. If the initial response from the family is one of portraying a patient who is very aggressive in terms of their goals of care, who would undertake most risks for even a marginal improvement in the quality of life or length of life, […] then I’m going to be able to take a step back and reassess and probably move the goal posts a little bit. I readjust my plan for that patient’s care, right and so, maybe it is, instead of withholding life-sustaining therapy right at that moment, because ultimately, I think it’s futile, maybe we say okay we’ll do a short trial. [P19]

[…] despite [the patient’s family choosing] a care plan that is not what I would think is the best, I’m able to say, you know, even though I don’t think we are adding to quality of life, at least we’re generally not increasing discomfort or pain in the patient… Thinking about this patient, she’s mostly unconscious and not interacting or not likely perceiving what’s going on in their environment. Even though I think the care may be non-beneficial, maybe there’s some consolation in saying I don’t think they’re in pain. That can help to mitigate the sense of conflict a bit. [P12]

I’m the second youngest recruit here. And typically, when I came, I would have counted myself among the more militant types. But what we find is over time that our practices sort of become similar. You hand over to these folks week after week, you start to learn their practice pattern, and you kind of learn what makes the unit run smoothly from intensivist to intensivist. [P3]

Evolving legislative frameworks, institutional culture and policies, and societal expectations affected physicians’ perceived power over moral decision-making, with resulting changes in preferred moral orientation and/or levels of moral distress. For example, the changing legal context pushed certain physicians toward adopting a resigned type of moral orientation.

I think, at least in Ontario, for the last three years, we’ve felt an increasing amount of pressure because of the College [College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario] policy around end-of-life care. Basically, requiring us to provide whatever the patient would request in terms of life support with very little autonomy at all to say no. [P8]

[…] once you know that legally you can’t just do a unilateral withdrawal … at least, that was the interpretation of our lawyers and of the CMPA [Canadian Medical Protective Association]. Well, what do you want to do? I’m not going to put myself at risk of a murder trial to liberate this bed. [P15]

Relationship Between Moral Orientation and Moral Distress/Sense of Reward

Moral orientation appeared as a “modulator of moral distress” since it determined in part if and how specific clinical situations elicited moral distress. Certain approaches (e.g., virtuous or deferring types) appeared to shield individuals against experiencing moral distress, whereas other approaches (e.g., resigned type) generally resulted in higher levels of moral distress.

We live in a society that has decided that, considering our current utilization of resources, we’re going to devote a lot of resources to people who are severely incapacitated […] that is the decision that we have made as a society, and ultimately, the patient is going to get to decide for just about every therapy that they want. There are a few hard ‘NOs’, but for the most part, if there are reasonable therapeutic options, and certainly if therapeutic options that have been initiated, we have decided that autonomy is valued. And so you have to be able to respect the family’s decision to go against healthcare recommendations, or there isn’t autonomy. […] for decisions around withdrawal of therapy for patients, I do respect patient autonomy, and I think that is something which we, as a healthcare community, need to be the mature party and say it’s not what I want, it’s not what I would do for my family, but if we’re going to have autonomy in society, they have to be able to go against us. That is, for me, a very reassuring thought, and it really eliminates almost all of my moral distress in these situations. [P15]

I am distressed that this patient is alive. I’m distressed that we are intervening inappropriately, and we have no control over that decision-making. My distress with the parent is that she’s being manipulated by a third-party advocate, who has different motivations […]. I’m distressed about seeing my nursing staff, the staff I work with, not having any control over the situation, because it’s their job, they have to be at the bedside. They’re having distress, but I’m feeling distress for them. [P10]

Moral orientation also affected participants’ perceived personal satisfaction and their sense of reward, as physicians valued and prioritized differently the possible moral outcomes of clinical situations. These outcomes included, for example, the moral satisfaction of acting according to their own personal beliefs (doing the “right” thing), of honoring patient/family’s wishes, or of maintaining positive relationships with families and colleagues.

I guess that’s an easier type of reward, when you can reconcile your beliefs with the patient’s wishes through communication. Like this person with an esophageal cancer who we brought to the ICU; it was very rewarding regardless of ongoing moral distress, because the moral distress I believe was due to the fact that there was no communication among all interested parties sitting together in one place. When things were explained and the family clearly heard what we recommended but also that we would respect their choice; and then allowed for the realignment of it, it really felt good. Because there was a whole bunch of people who benefited from it. The anxiety and anger was gone, the animosity between physicians was gone. And I had no doubt that what we had done was for the benefit of the patient. [P1]

I guess I get - I don’t know if pleasure is the right word - I don’t get pleasure out of putting my foot down on those situations, but I feel like it’s the right thing to do and I get satisfaction out of doing the right thing. [P7]

Moral Orientations Within a Team

Participants commonly described “clashing moral orientations within a care team.” Working environments in which healthcare professionals shared patient care responsibilities could be taxing when moral orientations differed between work colleagues. In these circumstances, certain physicians expressed strong judgments about colleagues who dealt with morally challenging clinical situations in ways that differed from their usual approach.

And the other thing that is important is that there’s a group of physicians who really do have a Dr. God complex. They do believe in telling people what to do because they know better. And for those people, when others don’t follow their instructions, they find it frustrating. [P16]

We as a profession feel self-pity because we are in a situation where we don’t want to be and there is moral distress coming from the fact that our values and preferences are not aligned with patients and families’ values, that we are forced to do things which we don’t consider beneficial or right. But I have quite strong opinions that it is our problem, that it is self-pity, that the whole healthcare is not about clinicians but it’s about the other side. And the moral distress frequently comes from the fact that we don’t communicate about it to the patients. And we try to impose our values without hearing their values. [P1]

In contrast, in clinical environments that presented more homogeneity in terms of moral orientation, colleagues were seen as a valuable source of support.

I think we’ve got an ethos in our ICU. Humanism is important and we try to be very patient and family centred. We try to have perspective about things that are frustrating in the workplace and try to find workarounds or acknowledging when they exist and trying to deal with them on our own. I think we talk to each other about what’s going on and how we’re thinking and feeling a fair bit. [P20]

[…] at least the medical team and the hospital has rallied around our group to support us, to try to help us move towards a more positive outcome. People in the hospital get this situation, our colleagues have been supportive. So, as far as relationships, it actually hasn’t caused any rifts or issues amongst the group, the nurses, RPs, physicians. We have tried to support each other. [P10]

What is helpful also is we do have open discussions within our care team about the appropriateness of care and explain different points of view. I think that could be better or even improved. We are open about sharing our ideas, but I think it definitely could be facilitated if we had additional human resources in the ICU that were specifically there to help us manage those discussions. [P13]

Taken together, these findings illustrate how sociocultural, legal, and clinical contexts influenced individual physicians’ moral orientation. Moral orientation altered perceived moral distress and moral satisfaction. The degree of dissonance between individual moral orientations within care team affected the extent of colleagues’ negative judgments and/or social support that physicians experienced. The balance between levels of moral distress and moral satisfaction, social judgment, and social support ultimately affected the type and severity of the negative consequences experienced by ICU physicians and their ICU teams (Fig. 1).

DISCUSSION

Moral distress is a prevalent and important problem among healthcare professionals, especially among critical care clinicians who routinely face morally challenging decisions (2, 8, 9, 29, 35–37). Yet, levels of moral distress vary greatly across critical care clinicians and institutions (2, 9). Our study findings indicate that moral orientation partially explains these variations. Based on our results, moral orientation is not a personal static trait, but rather an individual adaptation—either rapidly or progressively—to dynamic surrounding personal and professional circumstances; it appears to affect individual levels of moral distress and moral satisfaction. Interestingly, moral distress and satisfaction could emerge from the same clinical situations, a finding that has been described by others (38). In addition, differing moral orientations among a clinical team represented a common interpersonal source of distress for our participants and could elicit harsh judgments among colleagues. Based on these results, we argue that moral orientation can indirectly contribute to physician professional wellbeing and career choices (Fig. 1).

The concept of moral orientation is not new. Our findings partially align with the commonly described moral orientations of “justice” and “care” originally described by Kohlberg (16) and Gilligan (19), respectively. The virtuous and empathic moral orientations correspond best to the traditional dual (justice/care) view of moral orientation. However, we identified additional orientations (deferring and resigned) that seem to better capture the complexity of moral decision-making in real clinical environments. The perceived ability (or lack thereof) to act upon moral values, known as moral empowerment, is likely important in determining how moral decisions are made. A lack of moral empowerment was shown to lead to moral distress in certain study participants, depending on the strength of their individual moral beliefs and their acceptance of divergent moral views. Internal discrepancies between strengths of moral values and level of moral empowerment (like in a resigned orientation and possibly in an empathic orientation) resulted in moral distress. Moral empowerment may also relate to moral satisfaction, which was reported by many physicians, even when a certain amount of moral distress was present. These findings strongly align with a recent review on moral distress that reported significant correlations between moral distress on one hand, and poor ethical climate, deficient collaboration, low psychological empowerment, and limited autonomy on the other hand (37).

Another important study finding is the effect of heterogeneous moral orientations within care teams on individual perceptions of moral distress. Certain physicians reported important differences among their colleagues in their approaches to clinical moral dilemmas. This heterogeneity led to interpersonal conflicts, hindered social support in the workplace, and possibly contributed directly to the negative consequences associated with moral distress. This finding can be interpreted in view of the 4D model of moral distress described by Lamiani et al (37). Building on the previous 3D model of Hamric et al (14), Lamiani et al (37) added a fourth dimension, “poor teamwork,” to the existing dimensions of “ethical misconduct,” “deceptive communication,” and “futile care.” It is conceivable that conflicting moral orientations within a clinical team contribute to perceptions of ethical misconduct, deceptive communication, and poor teamwork among colleagues and therefore adds to the moral burden of individual clinicians.

These results have important implications for the design of interventions aimed at reducing moral distress in ethically charged clinical environments. Inter-disciplinary educational strategies that increase awareness of different moral orientations and of the key factors (including those that are modifiable and those not under the control of clinicians) involved in moral decision-making may be essential for clinicians to express more compassion toward their colleagues’ approach to clinical moral dilemmas. Education regarding moral orientation should be integrated early in healthcare training and continue to be the object of specific educational activities during practice (29, 39–41). Interventions focused on boosting healthcare professionals’ sense of moral empowerment may also be highly valuable (42). Even if moral distress cannot be fully alleviated because of constraining contextual factors, actively engaging in clinical moral decision-making may provide intrinsic benefits and counterbalance the burden of moral distress. Complete elimination of moral distress may not be a feasible or even desirable objective, as some level of distress may be intrinsic to the profession and to sound ethical decision-making. Institutional structures that create opportunities to engage with colleagues in conversations about morally challenging cases were identified by participants as constructive ways to address divergences in moral perspectives within a clinical team. Prospective (e.g., bedside huddles pre or after family meetings) and retrospective (e.g., debriefing after challenging ICU admissions) interventions have the potential to reduce tensions within clinical teams by explicitly addressing inter-individual differences in approaches to morally challenging situations.

This study has strengths and limitations. Our findings align with and add to the existing literature on moral distress and moral orientation, were supported by rich and extensive interview content, and have relevant, practical implications for critical care clinicians. However, our results are based only on interviews of a selected group of physicians who had participated in a national, cross-sectional survey on moral distress and expressed interest in being interviewed. Interviewees may not be representative of the general ICU physician population. Given the debate on the role of gender in the moral orientation literature, additional interviewees of female participants would have been useful for gender comparisons. Participants’ verbal reports of their experiences may not fully reflect their motivations to act in certain ways. As such, we cannot exclude the existence of other types of moral orientation and of alternative factors contributing to moral decision-making in various clinical environments. Furthermore, in this study, we did not explore whether our typology of moral orientations applied to nonphysician healthcare providers and to clinicians in other contexts.

CONCLUSIONS

The concept of moral orientation provided an interesting lens to explore the problem of moral distress in the critical care setting. Diversity in moral orientations may partially explain the variability in moral distress levels among healthcare professionals and likely contributes to interpersonal conflicts in the clinical environment. Additional investigations on the longitudinal development, malleability, adaptive advantages, and clinical consequences of different moral orientations in various clinical environments are much needed to inform the design of effective systemic and institutional interventions that adequately address healthcare professionals’ moral distress and/or mitigate its negative consequences.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group.

The authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccejournal).

REFERENCES

- 1.Jameton A: Nursing Practice: The Ethical Issues. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice Hall, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 2.McAndrew NS, Leske J, Schroeter K: Moral distress in critical care nursing: The state of the science. Nurs Ethics 2016; 25:552–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein EG, Hamric AB: Moral distress, moral residue, and the crescendo effect. J Clin Ethics 2009; 20:330–342 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheather J, Fidler H: Covid-19 has amplified moral distress in medicine. BMJ 2021; 372:n28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cacchione PZ: Moral distress in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Nurs Res 2020; 29:215–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kok N, Hoedemaekers A, van der Hoeven H, et al. : Recognizing and supporting morally injured ICU professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46:1653–1654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarthy J, Deady R: Moral distress reconsidered. Nurs Ethics 2008; 15:254–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamiani G, Borghi L, Argentero P: When healthcare professionals cannot do the right thing: A systematic review of moral distress and its correlates. J Health Psychol 2016; 22:51–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dodek PM, Cheung EO, Burns KEA, et al. : Moral distress and other wellness measures in Canadian critical care physicians. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2021; 18:1343–1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitehead PB, Herbertson RK, Hamric AB, et al. : Moral distress among healthcare professionals: Report of an institution-wide survey. J Nurs Scholarsh 2015; 47:117–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corley MC: Nurse moral distress: A proposed theory and research agenda. Nurs Ethics 2002; 9:636–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huffman DM, Rittenmeyer L: How professional nurses working in hospital environments experience moral distress: A systematic review. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 2012; 24:91–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarthy J, Gastmans C: Moral distress: A review of the argument-based nursing ethics literature. Nurs Ethics 2015; 22:131–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamric AB, Borchers CT, Epstein EG: Development and testing of an instrument to measure moral distress in healthcare professionals. AJOB Prim Res 2012; 3:1–926137345 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helmers A, Palmer KD, Greenberg RA: Moral distress: Developing strategies from experience. Nurs Ethics 2020; 27:1147–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohlberg L: Moral stages and moralization: The cognitive-developmental approach. In: Moral Development and Behavior. Lickona T. (Ed). New York, NY, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976, pp 31–53 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohlberg L: From is to ought: How to commit the naturalistic fallacy and get away with it. In: Cognitive Development and Epistemology. Mischel T. (Ed). New York, NY, Academic Press, 1971, pp 79–97 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bian J, Li L, Sun J, et al. : The influence of self-relevance and cultural values on moral orientation. Front Psychol 2019; 10:292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilligan C: In a different voice: Women’s conception of the self and morality. Harvard Educ Rev 1977; 47:481–517 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuhse H, Singer P, Rickard M, et al. : Partial and impartial ethical reasoning in health care professionals. J Med Ethics 1997; J23:226–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards SD: Is there a distinctive care ethics? Nurs Ethics 2011; 18:184–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaffee S, Hyde JS: Gender differences in moral orientation: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2000; 126:703–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grundstein-Amado R: Differences in ethical decision-making processes among nurses and doctors. J Adv Nurs 1992; 17:129–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuyel N, Glover RJ: Moral reasoning and moral orientation of U.S. and Turkish University Students. Psychol Rep 2010; 107:463–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forde R, Aasland OG: Moral distress among Norwegian doctors. J Med Ethics 2008; 34:521–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dryden-Palmer K, Moore G, McNeil C, et al. : Moral distress of clinicians in Canadian Pediatric and Neonatal ICUs*. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2020; 21:314–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burston AS, Tuckett AG: Moral distress in nursing: Contributing factors, outcomes and interventions. Nurs Ethics 2013; 20:312–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenthal MS, Clay M: Initiatives for responding to medical trainees’ moral distress about end-of-life cases. AMA J Ethics 2017; 19:585–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carnevale FA: Moral distress in the ICU: It’s time to do something about it!. Minerva Anestesiol 2020; 86:455–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leggett JM, Wasson K, Sinacore JM, et al. : A pilot study examining moral distress in nurses working in one United States burn center. J Burn Care Res 2013; 34:521–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weaver K: Pragmatic paradigm. In: The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation. Frey BB. (Ed). Thousand Oaks, CA, SAGE Publications, 2018:1287–1288 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piquette D, Carnevale FA, Burns KEA, et al. : Moral distress in critical care physicians: Contextual and relational causes, individual and collective consequences. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 199:A4303 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiger ME, Varpio L: Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med Teach 2020; 42:846–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berger R: Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qual Res 2013; 15:219–234 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamric AB, Blackhall LJ: Nurse-physician perspectives on the care of dying patients in intensive care units: Collaboration, moral distress, and ethical climate. Crit Care Med 2007; 35:422–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Browning SG: Burnout in critical care nurses. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 2019; 31:527–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamiani G, Setti I, Barlascini L, et al. : Measuring moral distress among critical care clinicians. Crit Care Med 2017; 45:430–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lutzen K, Cronqvist A, Magnusson A, et al. : Moral stress: Synthesis of a concept. Nurs Ethics 2003; 10:312–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berger JT: Moral distress in medical education and training. J Gen Intern Med 2013; 29:395–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumagai AK: From competencies to human interests. Acad Med 2014; 89:978–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin C-S, Tsou K-I, Cho S-L, et al. : Is medical students’ moral orientation changeable after preclinical medical education? J Med Ethics 2012; 38:168–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fleischmann A, Lammers J: Power and moral thinking. Curr Opin Psychol 2020; 33:23–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.