Abstract

BACKGROUND

The knowledge about eicosanoid metabolism and lipid droplet (LD) formation in the Leishmania is very limited and new approaches are needed to identify which bioactive molecules are produced of them.

OBJECTIVES

Herein, we compared LDs and eicosanoids biogenesis in distinct Leishmania species which are etiologic agents of different clinical forms of leishmaniasis.

METHODS

For this, promastigotes of Leishmania amazonensis, L. braziliensis and L. infantum were stimulated with polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) and LD and eicosanoid production was evaluated. We also compared mutations in structural models of human-like cyclooxygenase-2 (GP63) and prostaglandin F synthase (PGFS) proteins, as well as the levels of these enzymes in parasite cell extracts.

FINDINGS

PUFAs modulate the LD formation in L. braziliensis and L. infantum. Leishmania spp with equivalent tissue tropism had same protein mutations in GP63 and PGFS. No differences in GP63 production were observed among Leishmania spp, however PGFS production increased during the parasite differentiation. Stimulation with arachidonic acid resulted in elevated production of hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids compared to prostaglandins.

MAIN CONCLUSIONS

Our data suggest LD formation and eicosanoid production are distinctly modulated by PUFAS dependent of Leishmania species. In addition, eicosanoid-enzyme mutations are more similar between Leishmania species with same host tropism.

Key words: lipid droplet, eicosanoid, polyunsaturated fatty acids, GP63, PGF synthase, Leishmania

Lipid mediators are bioactive molecules derived from the metabolism of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). 1 The most common lipid mediator precursors are derived from arachidonic (AA), eicosapentanoic (EPA), and docosahexaenoic (DHA) acids. 1 Trypanosomatids, including Leishmania, can metabolise AA to eicosanoids by way of specific enzymes, such as cyclooxygenase (COX) and prostaglandin synthases (PG synthases). 2 , 3 , 4 In addition, specialised lipid mediators are also identified in Trypanosoma cruzi. 4 , 5 , 6

Lipid mediators are produced in the cytosol and in organelles termed lipid droplets (LD, lipid bodies), 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 which are present in almost all organisms, including in trypanosomatid protozoa. 4 , 7 , 10 , 11 , 12 LDs are active sites for eicosanoid metabolism. 7 , 8 Although protozoan parasites are known to produce a variety of specialised lipid mediators, studies investigating the role of these mediators in parasite biology and host-parasite interaction remain scarce.

Parasites possess the necessary machinery to synthesise eicosanoids. 3 Leishmania can metabolise AA to prostaglandins using PG synthases present in LDs. 7 Recently, the glycoprotein of 63 kDa (GP63) was described as a Cox-like enzyme responsible to convert AA to prostaglandin in L. mexicana. 2 In addition to COX, trypanosomatids contain enzymes capable of synthesising other eicosanoids, such as PGE2 and PGF2α. Both T. cruzi trypomastigotes and L. infantum respond to exogenous AA stimulation by producing prostaglandins. 7 , 10 However, the presence of AA was not shown to alter PGF synthase (PGFS) production in L. infantum. 7 L. infantum LDs are capable of synthesising PGF2α, a mediator responsible for increasing parasite viability in the initial moments of infection via an as yet unknown mechanism. 7 L. braziliensis promastigotes and amastigotes also express PGFS, which may improve parasites fitness. 13 Another pathway of lipid mediator production was recently described through the identification of proteins (CYP1, CYP2 and CYP3) similar to cytochrome P450 (CYP450) in the genome of L. infantum, which appear to be responsible for specialised lipid precursors in this parasite species. 14

Advances have been made in our understanding of the metabolism of bioactive lipids found in parasites, as well as mechanisms involving LDs. Leishmaniasis presents a diversity of clinical forms and symptoms related to specific Leishmania species. Herein we compared the formation of LDs and the production of eicosanoids in different New World Leishmania species using PUFA precursors as stimulant. Differences were identified in lipid metabolism among the Leishmania species investigated, and the enzymes related to eicosanoid production were described.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites - L. infantum (MCAN/BR/89/BA262) promastigotes were maintained for seven-nine days in hemoflagellate culture medium (HO-MEM) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) until reaching stationary phase. 7 For the cultivation of L. amazonensis (MHOM/BR/1987/BA125) and L. braziliensis (MHOM/BR/01/BA788), parasites were maintained in Schneider’s insect medium supplemented with 20% FBS, L-glutamine, 20 mM penicillin (100 U/mL) and streptomycin (0.1 mg/mL) at 26ºC for six days until reaching stationary phase.

Stimulation of Leishmania - Leishmania spp in the third day of axenic cultures (logarithmic-phase promastigote) were used to perform the experiments. In 96 wells plates, 1x106 parasites/well were either treated with progressively higher doses of EPA, DHA (3.75, 7.5, 15, 30 µM) or AA (15 µM), or with ethanol 0,3% v/v (vehicle), or medium alone (control), for 1 h. The 15 uM dose for AA was used, as we previously verified that higher doses could interfere with the viability of the parasite. 7 Next, parasites were fixed in formaldehyde 3.7% v/v and analysed by light microscopy as described below.

Lipid droplet staining - Fixed parasites were centrifuged on glass slides at 30g for 5 min. Slides were then washed with distilled water and subsequently kept in a 60% isopropanol solution for 5 min. Next, the slides were immersed in Oil Red O solution for 5 min. The slides were washed with distilled water and subsequently were mounted in aqueous medium, and the LDs marked by Oil Red O were quantified in 50 cells per slide using optical microscopy. 7

Parasitic viability - Following treatment with PUFAs, Leishmania promastigotes were placed on 96-well flat-bottom plates in the presence of tetrazole salt (XTT) (ROCHE Applied Science) and incubated at 26ºC for 4 h in the dark. Next, XTT reduction by mitochondrial metabolism was evaluated by quantifying optical density on a plate reader (spectrophotometer) (Varioskan, ThermoScientific) [Supplementary data (2.5MB, pdf) (Fig. 1)].

Lipid extraction to identify PUFAs and eicosanoids in parasite cell extract - After stimulation with AA, EPA or DHA, parasites isolated by centrifugation were subjected to hypotonic lysis in a 1:1 solution of deionised water and methanol at 4ºC. Culture supernatants were diluted at the same volume ratio in methanol at 4ºC. Samples were then stored at -80ºC until lipid extraction using liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS). Next, oxylipid extraction was performed using the solid phase extraction (SPE) method according to a previously described protocol. 15 After lipid extraction, specimens were transferred to autosampler vials, and 10 μL of each sample were injected into the Nexera-TripleTOF® 5600+ target liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system (SCIEX, Foster City, California) as previously described by Sorgi et al. 15 Final concentrations of oxylipids in culture extract and supernatants were quantified in accordance with standardised parameters. 15

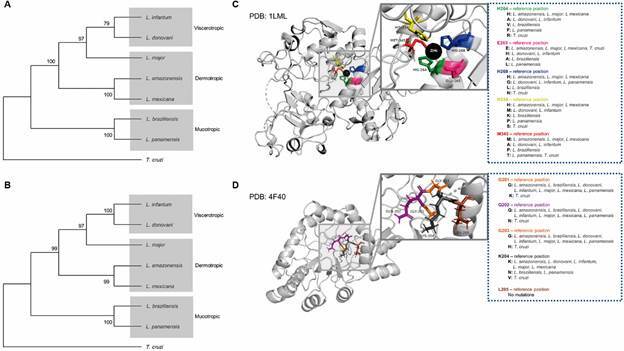

In silico identification of enzymes involved in Leishmania eicosanoid metabolism - At least two enzymes related to the production of lipid mediators have been identified in Leishmania: GP63 (human-like COX) 2 and prostaglandin F synthase (PGFS). 4 , 7 , 16 Initially, we performed a search for annotated nucleotide sequences characteristic of GP63 and PGFS using L. major as a reference species in GenBank. Using the BLASTn tool, complete genome sequences were identified and selected in the following species: L. donovani, L. infantum, L. amazonensis, L. braziliensis, L. panamensis, L. mexicana, L. major and T. cruzi. Only coding sequences (CDS) were considered for analysis [Supplementary data (2.5MB, pdf) (Tables I-II)]. Multiple alignment of the obtained protein sequences was performed using the Clustal W (Codons) method. The molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA X) program was employed to construct a phylogenetic tree via the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) using 1000 bootstraps. 17

3D modeling of GP63 and PGFS proteins in Old and New World Leishmania species - The protein data bank (PDB) was used to search for L. major crystallographic structures in order to identify the structures of the GP63 and PGFS proteins; 18 PDB IDs: 1LML for GP63 19 e PDB IDs: 4F40 for PFGS. 20 The prediction of protein structures was then performed in other Leishmania spp using the Interactive Threading assembly refinement (I-TASSER) bioinformatics method. 21 Using these structures, the PyMOL program was employed to create overlapping models and analyse the active site residues of these enzymes. 22

Western blot - To perform protein extraction, parasite cell cultures in either stationary or logarithmic growth stages were centrifuged at 1620 g for 10 min, 4ºC. Next, the pellet at a concentration of 2x108/mL was lysed using in 100 µL of radio immunoprecipitation buffer (RIPA). Next, the total amount of protein was quantified using the Pierce BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific). Total proteins (30 µg) were separated by electrophoresis on a 10% polyacrylamide sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked in Tris saline buffer (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TT) plus 5% milk for 1 h, followed by incubation with L. infantum anti-PGFS (1:1000) overnight. 7 The primary antibody was then removed, and the membranes were washed five times in TT followed by incubation with the secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse) (SeraCare’s KPL Catalog 074-1806) conjugated to peroxidase (1:5000) for 1h. Finally, the membranes were washed 5x again and then incubated with Western Blotting substrate (Thermo Scientific Pierce ECL, Amersham, UK).

GP63 immunoassays - Protein extracts of Leishmania in logarithmic and stationary phase were submitted to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to measure GP63 production. Briefly, 96-well immunoassay plates were sensitised with 30µg of Leishmania protein overnight at 4ºC. Then, nonspecific binding was blocked with 0.1% PBS Tween 20 (PBS-T) plus 5% milk for 2 h. After blocking, the plates were incubated with anti-GP63 (1:50) (Catalog #MA1-81830 Thermofisher) and incubated overnight at 4ºC. Next, the plates were washed with PBS-T and incubated with the secondary antibody (SeraCare’s KPL Catalog 074-1806) conjugated with peroxidase (1:2000) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the plates were incubated with 3,3’5,5’-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) for 30 min, after which the reaction was stopped using 3M HCl. Plates were read on a microplate reader (Molecular Devices Spectra Max 340PC) a wavelength of 450 nm.

Statistical analysis - Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad-Prism v8.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA-USA). All obtained data are represented as means ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis was performed using One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-test of linear trend when comparing dose-response data, while the Mann-Whitney test was employed to multiple comparison by pairs of groups, at a significance level of p < 0.05. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

RESULTS

Lipid droplets differ in quantity among Leishmania species - Our previous work demonstrated increasing numbers of LDs as L. infantum parasites differentiated into metacyclic forms in vitro. 7 Here, we also found higher numbers of LDs during the differentiation process in axenic cultures of L. braziliensis and L. infantum, but not in L. amazonensis (Fig. 1). In addition, LD formation was affected by stimulation with PUFAs; AA induced the formation of LDs in L. braziliensis and L. infantum, but not in L. amazonensis (Fig. 2). LD formation per parasite was found to be dose-dependent with regard to stimulation with EPA and DHA, as a statistically significant linear trend was observed for both L. braziliensis and L. infantum; however, no effect on LD formation was observed in L. amazonensis [Supplementary data (2.5MB, pdf) (Fig. 2)]. Furthermore, the doses of PUFAs used in the tests did not affect the viability of the parasites [Supplementary data (2.5MB, pdf) (Fig. 1)].

Fig. 1: lipid droplets in procyclic forms of Leishmania spp. Parasites in logarithmic and stationary growth phases were labeled with Oil Red O to count lipid droplet (LD). Data shown represent the mean ± standard error of LDs in (A) L. infantum, (B) L. amazonensis, and (C) L. braziliensis.***, p < 0.0001 using Mann-Whitney test for multiple comparison by pairs.

Fig. 2: polyunsaturated fatty acids increase the formation of lipid droplets in procyclic forms of Leishmania. Logarithmic growth phase promastigotes of (A) L. infantum (B) L. amazonensis and (C) L. braziliensis were stimulated with ethanol (vehicle) or AA (15 µM), EPA (30 µM) or DHA (30 µM) for 1 h, and then stained with Oil Red O to quantify LDs. Bars represent means ± SEM of lipid droplets (LDs) per parasite. *** and * represent p < 0.0001 and p < 0.05, respectively, for multiple pairwise comparisons between stimuli and the vehicle using the Mann-Whitney test. AA: arachidonic acid; EPA: eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA: docosahexaenoic acid.

Comparison of eicosanoid metabolism enzymes in Old and New World Leishmania spp - Proteins associated with eicosanoid metabolism are present in Leishmania spp., such as a COX-like enzyme, previously known as GP63, and PGFS. 4 We performed a comparison of the primary protein structure sequences in silico [Supplementary data (2.5MB, pdf) (Fig. 3)]. In addition, the tertiary structures of these reference proteins exhibited high structural similarities across Leishmania spp, as well as T. cruzi [Supplementary data (2.5MB, pdf) (Figs 4-5)]. Alignment and phylogenetic analysis of GP63 and PGFS indicated notable similarity and homology between the Old and New World Leishmania spp analysed with respect to clinical manifestations of disease [viscerotropic, dermotropic or mucotropic; Supplementary data (2.5MB, pdf) (Fig. 3), Figs 3A-B]. In addition, nonsynonymous mutations were identified in the amino acid residues at the active sites of GP63 (PDB ID: 1LML) and PGFS (PDB ID: 4F40). L. infantum and L. donovani shared mutations in GP63 protein residues. The dermotropic species presented same residues in the active site of the GP63 enzyme, while the species with mucosal tropism presented exclusive mutations in the active site of GP63 (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, most of the PGFS residues among viscerotropic, dermotropic and mucotropic species were conserved, except for the K204 residue that was altered in L. braziliensis and L. panamensis, both mucotropic species (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3: homology of GP63 and prostaglandin F synthase (PGFS) proteins across different Leishmania spp. GP63 and PGFS genes were identified in the reference genomes of etiologic pathogens related to human leishmaniasis. Phylogenetic trees of (A) GP63 and (B) PGFS were constructed using the UPGMA method (MEGA X software), considering 1000 bootstraps. Residues at the active sites of (C) GP63 and (D) PGFS proteins are highlighted by colours depicted in three-dimensional structures. Non-synonymous mutations among Leishmania spp. are listed.

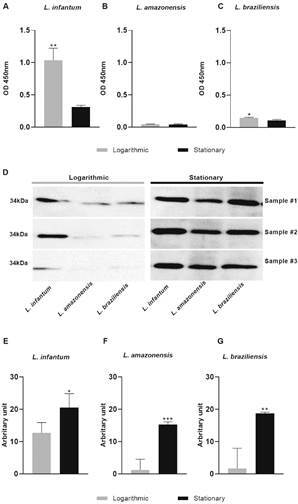

We then compared the gene expression of these two enzymes involved in the production of eicosanoids in different Leishmania species. GP63 was more produced in log-stage L. infantum and L. braziliensis parasites, but not in L. amazonensis (Fig. 4A-C). In addition, PGFS was more produced in stationary parasites compared to log-stage procyclic forms in all three species of Leishmania (Fig. 4D-G).

Fig. 4: GP63 and prostaglandin F synthase (PGFS) protein production in logarithmic and stationary axenic stages of Leishmania spp. Parasites in logarithmic and stationary growth phases were lysed to measure GP63 protein production in (A) L. infantum, (B) L. amazonensis, (C) L. braziliensis by immunoassay. Total protein (30 µg) was incubated with anti-PGFS (1:500) for Western blot analysis. (D) Immunoblot comparing the abundance of PGFS in logarithmic and stationary stages incubated with anti-PGFS (1:1000) in (E) L. infantum, (F) L. amazonensis, (G) L. braziliensis. * p < 0.05 for multiple pairwise comparisons between stimuli and the vehicle the Mann-Whitney test.

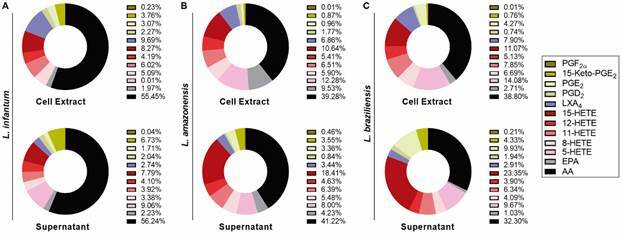

Qualitative effects of PUFAs on eicosanoid production in Leishmania spp - Trypanosomatids possess enzymatic machinery for the metabolisation of PUFAs to specialised and conventional lipid mediators. 4 , 5 , 14 Herein we used LC/MS to evaluate the presence of lipid mediator precursors, as well as eicosanoids, in L. infantum, L. amazonensis and L. braziliensis treated or not with AA, EPA or DHA. In all, 41 lipid mediators were analysed in cell extracts and axenic culture supernatants. The presence of twelve bioactive lipids was identified: 15-keto-PGE2, LXA4, PGD2, PGE2, 5-HETE, AA, 12-HETE, 8-HETE, 11-HETE, EPA, 15-HETE, PGF2α (Table and Fig. 5). However, mediators LTC4, PGB2, 6-keto-PGF1a, 17-RvD1, 12-oxo-LTB4, 20-OH-PGE2, TXB2, RvD1, RvD2, RvD3, LTB4, LTD4, LTE4, 6-trans-LTB4, 11-trans-LTD4, PDx, Maresin, PGJ2/PGA2, RvE1, 15-deoxy-PGJ2, 5-oxo-ETE, 20- HETE, 5,6-DiHETE, 12-oxo-ETE, 15-oxo-ETE, 11,12-DiHETrE, 14,15-DiHETrE, 5,6- DiHETrE, 20-OH-LTB4 were not identified. As expected, AA-derived eicosanoids were the most prevalent in Leishmania extracts (Fig. 5). In addition, eicosanoid production was poorly detected when parasites were stimulated with EPA and DHA (data not shown).

TABLE. Quantitation of eicosanoids and their precursors in cell extract and supernatant of Leishmania spp. by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS).

| Lipids | Standards * | Mass (m/z) | Lipid concentrations in cell extract and supernatant by Leishmania spp (ηg/mL)* | ||||||

| Precursor ion (m/z) | Fragment ion (m/z) | L. infantum | L. amazonensis | L. braziliensis | |||||

| C | S | C | S | C | S | ||||

| PGF2α | PGF2α-d4 | 353 | 309.2179 | 0.17 | 0.27 | < 0.01 | 4.68 | < 0.01 | 1.62 |

| 15-Keto-PGE2 | PGE2-d4 | 349 | 287.2017 | 2.82 | 43.80 | 1.32 | 36.12 | 1.12 | 33.89 |

| PGE2 | PGE2-d4 | 351 | 189.1285 | 2.30 | 11.14 | 1.46 | 34.19 | 6.31 | 77.74 |

| PGD2 | PGD2-d4 | 351 | 189.1285 | 1.70 | 13.29 | 2.69 | 8.56 | 1.09 | 15.21 |

| LXA4 | LXA4-d5 | 351 | 217.1598 | 7.27 | 17.59 | 10.46 | 35.05 | 11.66 | 22.76 |

| 15-HETE | 15-HETE-d8 | 319 | 175.1492 | 6.20 | 50.66 | 16.23 | 187.49 | 16.34 | 182.75 |

| 12-HETE | 12-HETE-d8 | 319 | 179.1078 | 3.14 | 26.65 | 8.26 | 47.16 | 7.57 | 30.52 |

| 11-HETE | 12-HETE-d8 | 319 | 167.1084 | 4.52 | 25.52 | 9.93 | 65.03 | 11.59 | 49.60 |

| 8-HETE | 12-HETE-d8 | 319 | 155.0714 | 3.82 | 22.01 | 9.00 | 55.83 | 9.88 | 32.00 |

| 5-HETE | 5-HETE-d8 | 319 | 115.0401 | < 0.01 | 58.94 | 18.74 | 81.46 | 20.79 | 75.68 |

| EPA | AA-d11 | 301 | 257.2275 | 1.48 | 14.54 | 14.54 | 43.07 | 3.99 | 8.10 |

| AA | AA-d11 | 303 | 259.2447 | 41.59 | 365.81 | 59.94 | 419.78 | 57.27 | 252.77 |

AA: arachidonic Acid; EPA: eicosapentaenoic acid; LX: lipoxin; PG: prostaglandin; HETE: hydroxyeicosatetraenoate; C: cell extract; S: supernatant. *Standard molecules containing Deuterium (d) atoms was used as an internal standard for the quantification of lipids by LC-mass spectrometry (MS).

Fig. 5: identification of lipid mediators in different Leishmania spp. Average distribution of the 10 abundant eicosanoids in the cell extract and supernatant of procyclic promastigotes of (A) L. infantum, (B) L. amazonensis and (C) L. braziliensis in logarithmic growth phase (with cell types labeled above each pie chart) stimulated with AA for 1 h, displayed as parts of the whole. Data are in percentage of ηg/mL of total lipid detected by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS). EPA: eicosapentanoic acid; 15-HETE: 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; 8-HETE: 8-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; 11-HETE: 11-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; 12-HETE: 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; AA: arachidonic acid; PGF2α: prostaglandin F2α; 15-keto-PGE2: 15-keto-prostaglandin E2; LXA4: Lipoxin A4; PGD2: prostaglandin D2; 5-HETE: 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid.

DISCUSSION

Leishmania lipid droplets are sites of production of eicosanoids, which are important for modulating the response to the parasite in vitro. However, the literature contains scarce data on eicosanoid metabolism in these parasites. 4 Here we compared eicosanoid metabolism and LD formation in response to PUFAs in different species of Leishmania associated with distinct clinical forms. Our data show that, in contrast to L. amazonensis, LD formation can be modulated by PUFA stimulation in L. infantum and L. braziliensis. However, with regard to eicosanoid production, the same eicosanoids were detected across all three New World species when stimulated with AA. The mechanisms of regulation of the production of LDs in Leishmania are still poorly understood. Trypanosomatids have only two proteins related to the LD formation, the lipid droplet kinase (LDK) and Trypanosoma brucei Lipin (TbLpn). 4 , 23 , 24 More studies will be necessary to investigate the presence and function of both LDK and TbLpn in Leishmania species. We can hypothesise that decrease in the activity in L. amanozensis could explain the inability of this parasite species to respond to PUFAs stimuli with the formation of LDs.

LDs are organelles that synthesise lipid mediators in a variety of cell types. 8 However, the role of LDs in eicosanoid production in parasites remains poorly understood. 4 In L. infantum, LDs are sites of production for PGF2α, 7 but the literature contains scare reports on the presence of enzymes related to the lipid metabolism of eicosanoids or bioactive lipids in other protozoa. Herein, we found that AA modulated the formation of LDs, which suggests the accumulation of AA in LDs that may serve as a platform for the synthesis of eicosanoids in some protozoa of the genus Leishmania.

Regarding the formation of lipid mediators, it is known that enzymatic machinery in protozoa is responsible for the synthesis of these bioactive compounds, such as GP63 2 and PGFS. 4 , 7 , 10 , 13 , 16 However, the enzymes that convert AA into lipid mediators have not been adequately studied. In L. mexicana, a GP63 protein was shown to be analogous to COX-2. 2 These protein metalloproteases are described as the main surface antigen expressed in promastigotes of different Leishmania species. 25 Although the genes encoding the GP63 metalloproteases are organised in tandem, 26 , 27 it has not been demonstrated whether COX-2 activity would arise from all of these encoded proteins. The production of PGF2α, which enzyme PGFS is responsible for synthesising, 3 activates the PGF2α receptor, triggering the COX pathway. 28 While little is known about the role of parasite-derived PGFS, some studies suggest the potential role of this eicosanoid in host-parasite interaction. 7 , 13 The analysis of the viscerotropic and dermotropic Leishmania species point out some genetic differences related to parasite tropism. 29 However, a relationship between the genetics of the parasites and the pathophysiology is still necessary. In this sense, identifying the differences in the production of eicosanoids can help to explain the distinct clinical manifestations caused between different species of Leishmania, since the mechanisms of eicosanoid action during inflammation are well knowns. 8 , 30 Our comparison of protein sequences and GP63 and PGFS active site residues in both Old and New World Leishmania species revealed surprising similarity between these enzymes in accordance with the clinical form of disease caused by the parasite. Nonetheless, additional studies are needed to verify if, in fact, this similarity could be related to GP63 and PGFS production, and to the development of a polarised response according to the clinical manifestation. Indeed, some studies in humans have shown altered production of lipid mediators depending on the cutaneous or visceral form of disease. 7 , 31

An important aspect of our evaluation focused on the production of enzymes involved in the metabolism of eicosanoids during the metacyclogenesis of different New World Leishmania species. The COX-like enzyme GP63 production reduces during L. braziliensis and L. infantum promastigotes differentiation, but no differences are observed in L. amazonensis. In the next AA metabolism step, PGFS production increases during parasite differentiation in different Leishmania species. This finding may indicate that PGFS could influence the virulence of infective forms of Leishmania spp. Considering the differences in the structure of and family of genes encoding these enzymes, further studies are needed to correlate these differences with the enzymatic activity exhibited by PGFS in Leishmania.

While some studies have advanced the understanding of lipid metabolism, the enzymes involved in parasites remain poorly described; however, knowledge on which metabolites are produced by zoonotic parasites is expanding. 2 , 9 , 10 , 14 Here, we investigated the metabolites produced by different Leishmania species, observing increased production of lipid mediators of the HETE class. Importantly, little is known about the role played by these metabolites during the host-parasite interaction process. Additional studies may shed light on whether these should be considered virulence factors and thus may serve as intervention targets, in addition to whether their currently unidentified receptors could elucidate mechanisms of pathogenicity. The present findings serve to open perspectives by providing evidence on how PUFAs lead to the modulation of LD formation in different Old and New World Leishmania species. We believe that our qualitative overview of lipid mediators potentially produced by these parasites contributes to the base of knowledge surrounding antiparasitic drug development.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To CEQIL, the Centre of Excellence in Lipid Quantification and Identification (FCFRP-USP). We thank Larisse Ricardo Gadelha and Flávio Henrique de Jesus Santos for technician support. We also thank Patricia T Bozza, Artur Trancoso Lopo de Queiroz, and Leonardo Paiva Farias for insightful discussions. The authors would like to thank Andris K Walter for critical analysis, English language revision and manuscript copyediting assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jordan PM, Werz O. Specialized pro-resolving mediators: biosynthesis and biological role in bacterial infections. FEBS J. 2021 doi: 10.1111/febs.16266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estrada-Figueroa LA, Díaz-Gandarilla JA, Hernández-Ramírez VI, Arrieta-González MM, Osorio-Trujillo C, Rosales-Encina JL. Leishmania mexicana gp63 is the enzyme responsible for cyclooxygenase (COX) activity in this parasitic protozoa. Biochimie. 2018;151:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2018.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubata BK, Duszenko M, Martin KS, Urade Y. Molecular basis for prostaglandin production in hosts and parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2007;23(7):325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tavares VS, De Castro MV, Souza RSO, Gonçalves IKA, Lima JB, Borges VM. Lipid droplets from protozoan parasites survival and pathogenicity. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2021;116:e210270. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760210270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colas RA, Ashton AW, Mukherjee S, Dalli J, Akide-Ndunge OB, Huang H. Trypanosoma cruzi produces the specialized proresolving mediators resolvin D1, Resolvin D5, and Resolvin E2. Infect Immun. 2018;86(4):e00688–e00617. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00688-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paloque L, Perez-Berezo T, Abot A, Dalloux-Chioccioli J, Bourgeade-Delmas S, Le Faouder P. Polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolites biosynthesis in Leishmania and role in parasite/host interaction. J Lipid Res. 2019;60(3):636–647. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M091736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Araújo-Santos T, Rodríguez NE, Moura-Pontes S, Dixt UG, Abánades DR, Bozza PT. Role of prostaglandin F2a production in lipid bodies from Leishmania infantum chagasi insights on virulence. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(12):1951–1961. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bozza PT, Bakker-Abreu I, Navarro-Xavier RA, Bandeira-Melo C. Lipid body function in eicosanoid synthesis an update. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2011;85(5):205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Almeida PE, Toledo DAM, Rodrigues GSC. D'Avila H Lipid bodies as sites of prostaglandin E2 synthesis during Chagas disease impact in the parasite escape mechanism. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toledo DAM, Roque NR, Teixeira L, Milán-Garcés EA, Carneiro AB, Almeida MR. Lipid body organelles within the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi a role for intracellular arachidonic acid metabolism. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):1–22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olzmann JA, Carvalho P. Dynamics and functions of lipid droplets. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(3):137–155. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0085-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onal G, Kutlu O, Gozuacik D, Dokmeci Emre S. Lipid droplets in health and disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12944-017-0521-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alves-Ferreira EVC, Ferreira TR, Walrad P, Kaye PM, Cruz AK. Leishmania braziliensis prostaglandin F2a synthase impacts host infection. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-3883-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paloque L, Perez-Berezo T, Abot A, Dalloux-Chioccioli J, Bourgeade-Delmas S, Le Faouder P. Polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolites biosynthesis in Leishmania and role in parasite/host interaction. J Lipid Res. 2019;60(3):636–647. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M091736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorgi CA, Peti APF, Petta T, Meirelles AFG, Fontanari C, de Moraes LAB. Data descriptor comprehensive high-resolution multiple-reaction monitoring mass spectrometry for targeted eicosanoid assays. Sci Data. 2018;5:1–12. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kabututu Z, Martin SK, Nozaki T, Kawazu SI, Okada T, Munday CJ. Prostaglandin production from arachidonic acid and evidence for a 9,11-endoperoxide prostaglandin H 2 reductase in Leishmania. Int J Parasitol. 2003;33(2):221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00254-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(6):1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schlagenhauf E, Etges R, Metcalf P. The crystal structure of the Leishmania major surface proteinase leishmanolysin (gp63) Structure. 1998;6(8):1035–1046. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moen SO, Fairman JW, Barnes SR, Sullivan A, Nakazawa-Hewitt S, Van Voorhis WC. Structures of prostaglandin F synthase from the protozoa Leishmania major and Trypanosoma cruzi with NADP. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun. 2015;71(5):609–614. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X15006883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang J, Zang Y. Protein structure and function prediction using I-TASSER. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2015;52:581–515. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0508s52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan S, Chan HCS, Hu Z. Using PyMOL as a platform for computational drug design. WIREs Comput Mol Sci. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nejad LD, Serricchio M, Jelk J, Hemphill A, Bütikofer P. TbLpn, a key enzyme in lipid droplet formation and phospholipid metabolism, is essential for mitochondrial integrity and growth of Trypanosoma brucei role of lipin in T. brucei growth. Mol Microbiol. 2018;109(1):105–120. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flaspohler JA, Jensen BC, Saveria T, Kifer CT, Parsons M. A novel protein kinase localized to lipid droplets is required for droplet biogenesis in trypanosomes. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9(11):1702–1710. doi: 10.1128/EC.00106-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isnard A, Shio MT, Olivier M, Bengoechea JA. Impact of Leishmania metalloprotease GP63 on macrophage signaling. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ivens AC, Peacock CS, Worthey EA, Murphy L, Aggarwal G, Berriman M. The genome of the kinetoplastid parasite, Leishmania major. Science. 2005;309(5733):436–442. doi: 10.1126/science.1112680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peacock CS, Seeger K, Harris D, Murphy L, Ruiz JC, Quail MA. Comparative genomic analysis of three Leishmania species that cause diverse human disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39(7):839–847. doi: 10.1038/ng2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ueno T, Fujimori K. Novel suppression mechanism operating in early phase of adipogenesis by positive feedback loop for enhancement of cyclooxygenase-2 expression through prostaglandin F2a receptor mediated activation of MEK/ERK-CREB cascade. FEBS J. 2011;278(16):2901–2912. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ait Maatallah I, Akarid K, Lemrani M. Tissue tropism Is it an intrinsic characteristic of Leishmania species? Acta Trop. 2022;232:106512–106512. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2022.106512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bozza PT, Magalhães KG, Weller PF. Leukocyte lipid bodies - Biogenesis and functions in inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791(6):540–551. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malta-Santos H, Fukutani KF, Sorgi CA, Queiroz ATL, Nardini V, Silva J, et al. Multi-omic analyses of plasma cytokines, lipidomics, and transcriptomics distinguish treatment outcomes in cutaneous leishmaniasis. iScience. 2020;23 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]