Abstract

The proto-oncogene c-myb is essential for a controlled balance between cell growth and differentiation. Aberrant c-Myb activity has been reported for numerous human cancers, and enforced c-Myb transcription can transform cells of lymphoid origin by stimulating cellular proliferation and inhibiting apoptotic pathways. Here we demonstrate that activation of the NF-κB pathway by the HTLV-1 Tax protein leads to transcriptional inactivation of c-Myb. This conclusion was supported by the fact that Tax mutants unable to stimulate the NF-κB pathway could not inhibit c-Myb transactivating functions. In addition, inhibition of Tax-mediated NF-κB activation by coexpression of IκBα restored c-Myb transcription, and Tax was unable to block c-Myb transcription in a NEMO knockout cell line. Importantly, physiological stimuli, such as signaling with the cellular cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), and lipopolysaccharide, also inhibited c-Myb transcription. These results uncover a new link between extracellular signaling and c-Myb-dependent transcription. The mechanism underlying NF-κB-mediated repression was identified as sequestration of the coactivators CBP/p300 by RelA. Interestingly, an amino-terminal deletion form of p300 lacking the C/H1 and KIX domains and unable to bind RelA retained the ability to stimulate c-Myb transcription and prevented NF-κB-mediated repression.

The c-myb proto-oncogene is expressed predominantly in hematopoietic tissues and plays a role in tumorigenesis (33, 35). c-Myb is a nuclear phosphoprotein that can transactivate through a consensus sequence (PyAACG/T), referred as the Myb responsive element (MRE). c-Myb protein possesses three distinct functional domains: a DNA binding domain, a transactivating domain, and a negative regulatory domain. Some factors can increase c-Myb-dependent transcription: CBP/p300, C/EBPβ, C/EBPɛ, Ets, Pim kinase, and p100 (10, 30, 34, 42, 44, 47, 61), while other proteins, p67, ATBF1, Cyp-40, and c-Maf, inhibit c-Myb-dependent transcription (11, 20, 27, 31, 58).

Aberrant c-Myb expression has been reported for human leukemia, neuroblastoma, colon carcinoma, small lung carcinoma, and breast carcinoma (16). Compelling evidence indicates that c-Myb expression is essential for a controlled balance between cell growth and cell differentiation. The level of c-Myb protein is high in immature cells of the lymphoid, erythroid, and myeloid lineage and is down-regulated during terminal cellular differentiation (17). Enforced expression of c-Myb can transform cells of a differentiated phenotype (63). Although regulation of c-Myb transcription is largely unknown, a link from the cellular signaling pathway through p100 and Pim kinase and c-Myb transactivation was recently identified (30).

A large variety of proteins have been shown to directly interact with c-Myb to either synergize or antagonize c-Myb transactivating functions. Among those, the coactivators CBP/p300 have been shown to increase c-Myb transactivation. c-Myb interacts with CBP/p300 in a signal-independent manner through the KIX domain (10, 42). Because CBP/p300 are recruited by a wide array of transcription factors and because their level is rate limiting within the nucleus (57, 66), it has been speculated that CBP/p300 may act as multifunctional adapter proteins and regulate transcription in part through competitive usage by distinct transcription factors.

The human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is the etiological agent of adult T-cell leukemia or lymphoma and tropical spastic paraparesis (46, 45, 15). The viral transactivator Tax has been shown to target key regulators of the cell cycle, such as p16ink4A, p21waf1/cip1, p53, Rb, and MAD-1 (1, 7, 24, 37, 56). Tax has been shown to activate transcription through distinct pathways, including the CREB/ATF, NF-κB, and the serum responsive element (SRE) pathways (29, 32). These pleiotropic effects of Tax alter the expression of a wide array of cellular genes involved in cellular proliferation and antiapoptotic signals and are associated with the transforming capacity of Tax. In contrast to its transactivating functions, Tax has also been shown to repress cellular promoters, such as β-polymerase, Lck, B-Myb, and c-Myb (23, 28, 39, 40). Tax has been shown to activate the NF-κB pathway by stimulation of the IκB kinase complex (IKK), resulting in a permanent degradation of both IκBα and IκBβ; the mechanism by which Tax stimulates the IKK complex is still a matter of debate (14, 25, 32, 64, 67).

NF-κB is an inducible transcription factor that is rapidly activated in immune functions in response to external stimuli. The most abundant transcriptionally active NF-κB complex is composed of the RelA/p65 and p50 heterodimers. In resting cells, RelA is retained in the cytoplasm through interactions with inhibitory molecules, mainly IκBα and IκBβ. Upon NF-κB activation, IκB molecules are targeted for proteasome degradation and the nuclear levels of RelA potently increase. The coactivators CBP/p300 are then recruited for transcriptional activity.

Here we demonstrate that c-Myb-dependent transcription is inhibited by HTLV-1 Tax through the activation of the NF-κB pathway, which in turn results in the sequestration of the transcriptional coactivators p300/CBP. Cellular cytokine signaling also resulted in strong inhibition of c-Myb transcription, uncovering a new link between extracellular signaling and c-Myb transcription. Importantly, we found that in addition to the KIX domain, c-Myb also interacts with the carboxy-terminal domain of p300, which was sufficient to stimulate c-Myb transcription and prevent NF-κB-mediated repression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and transfections.

Mouse embryo fibroblast (MEF) cell lines (2, 3, 51) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum in the presence of 100 units of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 2 mM glutamine. Experiments carried out with mouse knockout cell lines were also confirmed with the human Jurkat T-cell line. Only results from MEF and MEF −/− cells for which we can easily control for protein expression are shown in the study. The Rat-1, 5R, and 293T cell lines were maintained under the same conditions with fetal bovine serum. Transfections were carried out using the Effectene reagent (Qiagen). Twenty-four to thirty hours posttransfection, cells were assayed for luciferase activity (Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay; Promega Corporation). The level of transfected DNA was held constant by adding pCDNA, and all transfection efficiencies were evaluated by cotransfection of Renilla thymidine kinase (RL-TK) (0.1 μg). Results represent means ± standard deviations calculated from three independent transfections. Results presented in this study were confirmed with the human T-cell line Jurkat and also by using the c-myb promoter as a reporter construct or the mouse c-Myb pRMb3SV for a different source of c-Myb-expressing vector.

Expression plasmids.

Expression vectors for the human c-Myb protein and c-myb promoter reporter construct were obtained from L. Boxer (18). The mim-1 promoter-derived MRE-luciferase reporter was provided by J. S. Lipsick (13). FL-c-Myb was obtained from J. Bies and L. Wolff (5). C. Kitanaka provided the Pim kinase expression vector. The expression vector pSG5-p100 encoding the coactivator p100 was provided by S. Ness (30, 60). HTLV-1 Tax wild-type, M22 and M47, NF-κB RelA/p65 and p65 mutant 1-312, and IκBα expression vectors were provided by W. C. Greene (52, 55). The HA-NEMO expression vector was provided by A. Israel (65). The expression vectors FLAG-p65 and mutants S274A and S576A were provided by A. Baldwin (62). Bluescript BS-p65 vector was obtained from the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research Reagent Program. Expression vectors for c-Rel and RelB were obtained from N. Rice. Expression vectors for the NF-κB p50, p50m56/57, and p50m59/60 mutants were obtained from U. Siebenlist (6). The expression vector for FLAG-p300 was obtained from D. Livingston (12). Hemagglutinin-tagged CBP was obtained from R. H. Goodman (8). Vectors expressing the different regions of p300 were obtained from H. Nakatoni and V. Ogryzko.

Coimmunoprecipitation, immunoblots, and antibodies.

Cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing sodium fluoride (50 mM), sodium orthovanadate (0.2 mM), sodium pyrophosphate (30 mM), and protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete, Roche Molecular). Protein extracts were incubated with the appropriate antibody overnight at 4°C. Immune complexes were captured by adding 40 μl of prewashed protein A/G agarose (Life Technologies), which was collected by centrifugation, washed twice with five volumes of lysis buffer, and resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were obtained as previously described (41). For immunoblots, 50 μg of protein was resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide Tris-glycine gels (Novex) and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). Nonspecific sites were saturated by incubation for 30 min at room temperature with a TNE (50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA)–5% milk solution, and primary antibody diluted in TNE–1% milk was incubated overnight at 4°C followed by a 2-h room temperature incubation with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Inc.). After several washes in TNE–0.1% Tween 20, immunoblots were developed using the chemiluminescence kit West-Dura (Pierce). Antibodies used in this study are as follows: human-specific reactive c-Myb sc517, HA F7, p65 sc372 or amino-terminal sc109 (to detect p65 1-312), p50 sc1190, and IκBα sc371. All secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz, FLAG M2 was from Sigma, and mouse monoclonal c-Myb clone 1-1, used for supershift and immunoprecipitation from 293T cells, was purchased from Upstate.

In vitro rabbit reticulocyte translation and binding assays.

In vitro translation of the RelA/p65 (BS-p65) and c-Myb (FL-Myb) proteins was performed using the TNT kit (Promega). In vitro binding assays were performed as previously reported (39). Alternatively, MEF p65−/− cells were transfected with p65 or p65 mutants, and cellular extracts were mixed with radiolabeled in vitro-translated c-Myb or p300 proteins. Interaction of c-Myb with the different domains of p300 was achieved by incubating 293T transfected cell extract with radiolabeled in vitro-translated p300 and p300-derived constructs. Cellular extracts from 293T cells transfected with c-Myb were incubated overnight at 4°C with in vitro-synthesized p300 domains in 300 μl of the following buffer: HEPES [25 mM], KCl [0.1 M], sodium fluoride, sodium orthovanadate, and protease inhibitors. c-Myb monoclonal antibody bound to protein A/G agarose was added, and the mixture was further incubated overnight at 4°C. After three washes in binding buffer containing 0.05% Triton X-100, protein interactions were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and autoradiography.

Immunofluorescence.

All incubations were performed at room temperature. Transfected cells were fixed by immersion in a 4% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–paraformaldehyde solution for 10 min, rinsed twice with PBS-glycine (0.1 M) for 10 min, and permeabilized with PBS–0.1% triton for 10 min. After three washes with 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA), nonspecific sites were blocked for 30 min in 2% BSA–1% milk in PBS. Primary antibodies diluted 1/100 in PBS–2% BSA were incubated for 1 h, and slides were washed and incubated with the secondary antibodies anti-rabbit Cyt 3 (1/200 in PBS-BSA) and anti-mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate (1/100 in PBS-BSA) for one additional hour. Slides were washed, mounted, and observed using an argon-krypton laser confocal microscope (Leica).

EMSA.

Transfected 293Tor MEF cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.05], 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 0.2 mM Na3VO4, 30 mM Na2P2O7, 5 μM ZnCl2, 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche Molecular). The lysate was vortexed for 30s, centrifuged at 4°C for 30 min at 14,000 rpm, and stored at −80°C. For electrophoretic mobility shift analysis (EMSA), the oligonucleotide MRE-A (5′-CACATTATAACGGTTTTTTAGC-3′) from the mim-1 promoter (36) was end labeled with [γ-32P]dCTP using T4 polynucleotide kinase. The DNA-binding reaction was performed for 1 h at 25°C as previously described (43) using 0.1 ng of labeled oligonucleotide probe and the binding buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.9], 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5% nonfat dry milk, 5% glycerol) supplemented with 2 μg of salmon sperm and 1 μg of poly(dI-dC) in a final volume of 15 μl. c-Myb protein from transfected cell extracts was adjusted so that similar levels of c-Myb protein were used in each binding reaction. Supershift was performed by adding 1 μg (1 μl) of monoclonal antibody raised against c-Myb (Upstate) in the binding reaction. Competition was accomplished by adding a 20-fold excess of cold MRE probe in the binding reaction. The DNA-protein complexes were separated on prerun 6% Tris-borate-EDTA gels (Novex) in 0.25× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (Novex) at 150 V for 2 h. Gels were dried and exposed to X-ray film at −80°C.

RESULTS

HTLV-1 Tax inhibits c-Myb transactivation through its NF-κB-inducing activity.

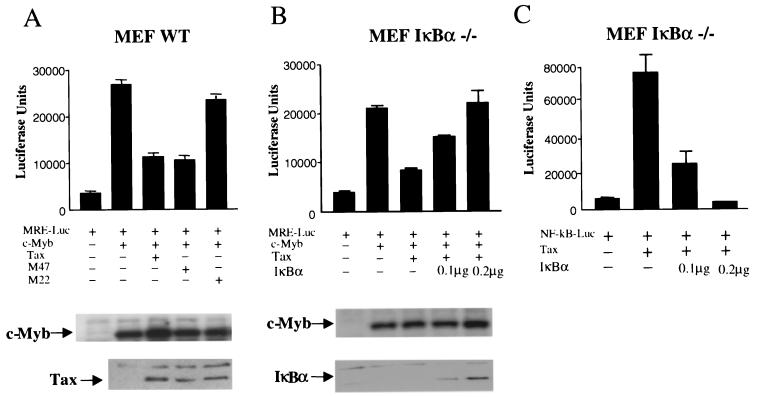

c-Myb and HTLV-1 Tax or Tax mutants were expressed in MEFs along with an MRE construct (MRE-Luc) to monitor c-Myb transcriptional activity. MEF cells were chosen because of the lack of endogenous c-Myb protein expression, their transfection efficiency, which allows controlling for protein expression, and the availability of various genetic knockout lines. However, results presented here have also been confirmed with Jurkat T cells using the endogenous c-Myb protein. Both the wild type and the Tax mutant M47, previously shown to activate the NF-κB pathway, inhibited c-Myb transactivation, while the Tax mutant M22, unable to activate NF-κB, had no significant effect on c-Myb transactivation (Fig. 1A). Western blot analysis showed a comparable expression of Tax, Tax mutants, and c-Myb protein (Fig. 1A). These results suggest that Tax-mediated NF-κB activation may be involved in the transcriptional repression of c-Myb. To confirm this observation, the Tax effect was assessed in MEF IκBα−/− cells along with increasing amounts of an IκBα expression vector. Despite the absence of IκBα, Tax was able to stimulate NF-κB, possibly through degradation of IκBβ. Consistent with a role for NF-κB, increased expression of IκBα restored c-Myb transcriptional activity in the presence of Tax (Fig. 1B) while inhibiting the ability of Tax to stimulate NF-κB activation in similar experimental conditions (Fig. 1C). Levels of c-Myb and Tax were not affected by IκBα (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

HTLV-1 Tax represses c-Myb transcription through activation of NF-κB. (A) MEF cells were transfected with MRE (1 μg) (MRE-Luc), along with c-Myb (0.5 μg), and Tax or Tax mutants (0.25 μg) and RL-TK (0.1 μg), and luciferase activity was measured 36 h later. Protein expression was investigated by Western blotting. (B) MEF IκBα−/− cells were transfected with MRE, c-Myb, Tax, IκBα (0.1 or 0.2 μg), and RL-TK (0.1 μg). Protein expression was investigated by Western blotting. (C) MEF IκBα−/− cells were transfected with an NF-κB-luciferase reporter construct, Tax and IκBα (0.1 μg or 0.2 μg), and RL-TK (0.1 μg).

Tax-mediated repression of c-Myb requires a functional IKK.

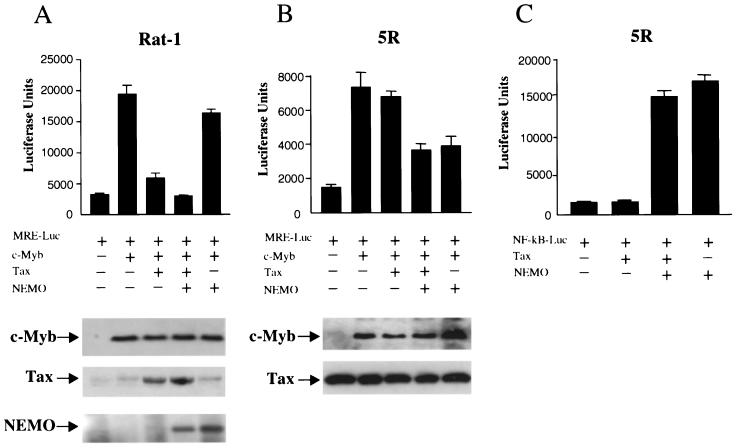

To further confirm these results, we used the Rat-1 fibroblast cell line and its derivative line 5R (65). 5R expresses constitutive high levels of a wild-type Tax protein but lacks constitutive activation of the NF-κB pathway as a result of a mutation in NEMO, the homologue of the human IKKγ gene (65). Although 5R cells express high levels of Tax protein, exogenous Tax was added to control for the possibility that mutations in the constitutively expressed Tax could influence the results; however, similar results were also obtained in absence of exogenous Tax. Consistent with previous reports, Tax did not activate the NF-κB pathway in 5R cells unless an expression vector for NEMO was coexpressed (65) (Fig. 2C). Because of endogenous Tax in 5R cells, the addition of NEMO alone was sufficient to achieve strong NF-κB activation (Fig. 2C). In contrast, NEMO alone was not able to activate NFκB in the Rat-1 control cells (Fig. 2A). Levels of protein expression were assessed by Western blotting. Importantly, in 5R cells Tax had no effect, and only conditions that led to NF-κB activation also resulted in inhibition of c-Myb transactivation (Fig. 2A and B). These results demonstrated that HTLV-1 Tax-mediated suppression of c-Myb transactivating functions is dependent on its ability to activate the NF-κB pathway.

FIG. 2.

Tax-mediated repression of c-Myb requires a functional IKK. (A) Rat-1 fibroblast cells were transfected with MRE (1 μg) and c-Myb (0.5 μg) in the presence or absence of Tax (0.25 μg) and/or NEMO (0.15 μg) and RL-TK (0.1 μg). Protein expression was investigated by Western blotting. (B) Rat-1 derivative Tax-expressing 5R cells were transfected with MRE (1 μg) and c-Myb (0.5 μg) in the presence or absence of Tax (0.25 μg) and/or NEMO (0.15 μg) and RL-TK (0.1 μg). Protein expression was investigated by Western blotting. (C) 5R cells were transfected with a NF-κB-luciferase reporter construct (1 μg), Tax (0.25 μg) and/or NEMO (0.15 μg), and RL-TK (0.1 μg).

Stimulation with proinflammatory cytokines represses c-Myb transactivation.

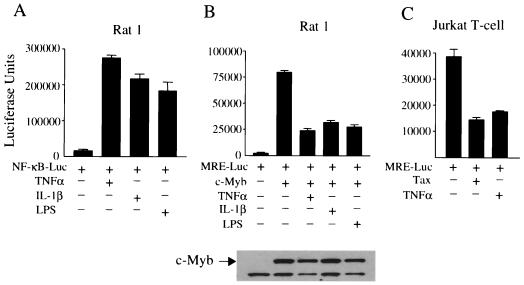

We then tested whether more physiological stimuli resulting in NF-κB activation, as achieved by the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), and LPS, would result in similar inhibition of c-Myb transactivation functions. This approach would also indicate whether NF-κB activation, independent of Tax, would be sufficient to inhibit c-Myb transactivation. Stimulation of Rat-1 cells by the cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and LPS was achieved as previously described by others (65). Under these conditions, a strong NF-κB activation was obtained, as evidenced by activity from the NF-κB-Luc construct (Fig. 3A). Under the same experimental conditions, c-Myb transactivation was severely inhibited (Fig. 3B), although similar levels of Myb protein expression were detected by Western blot. The effect of HTLV-1 Tax and TNF-α on endogenous c-Myb protein was confirmed with Jurkat T-cells (Fig. 3C). Similar results were also obtained with MEF cells. In addition, c-Myb transrepression was also observed by the NF-κB-activating HHV-8 K13 expressing vector (V. Lacoste et al., unpublished data). Altogether, these results identify NF-κB as a negative regulator of c-Myb transactivation.

FIG. 3.

Effects of lymphokines on c-Myb-dependent transcription. (A) Rat-1 fibroblast cells were transfected with NF-κB-luciferase reporter construct MRE (NF-κB-Luc) (1 μg), c-Myb (0.5 μg), and RL-TK (0.1 μg) expression vectors. Eighteen hours later, cells were stimulated with TNF-α, IL-1β, or LPS. Luciferase activity was assayed 36 h later. Results are means ± standard deviations calculated from three independent transfections. Levels of c-Myb expression were analyzed by Western blotting. (B) Rat-1 fibroblast cells were transfected with the MRE luciferase reporter construct (MRE-Luc) and treated as described above. (C) The Jurkat T-cell line was transfected with the MRE-Luc vector (1 μg) and stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 24 h or in the presence of Tax (0.2 μg).

RelA inhibits c-Myb-dependent transactivation independently of its transcriptional activity.

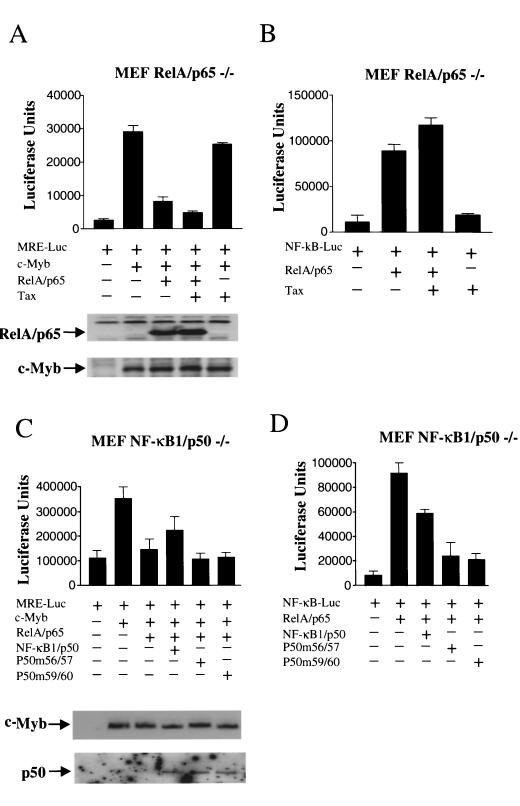

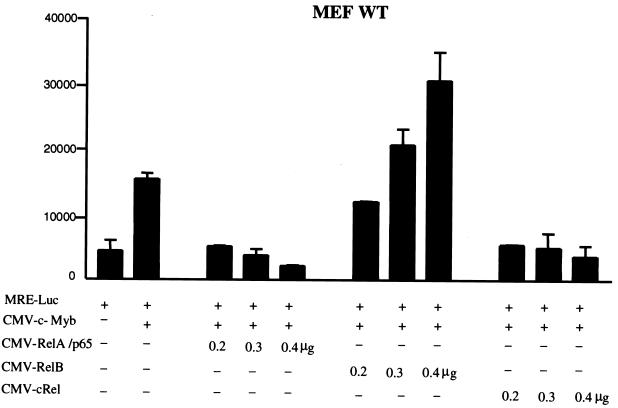

To gain further insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying c-Myb transrepression, we tested the ability of the NF-κB RelA subunit to inhibit c-Myb transactivation in MEF RelA−/− cells. Surprisingly, Tax was not able to significantly activate the NF-κB pathway in these cells (Fig. 4B, lane 4). As expected, RelA strongly stimulated NF-κB (Fig. 4B, lane 2). Only experimental conditions in which NF-κB was activated permitted c-Myb transcriptional inhibition (Fig. 4A, lanes 3 and 4). Expression levels of c-Myb and RelA showed no significant variation (Fig. 4A). These results demonstrated the ability of RelA to control c-Myb transcriptional activity. Together with results obtained with MEF IκB−/− and NEMO−/− cells, the absence of c-Myb repression by Tax in MEF RelA−/− cells confirms our previous observations demonstrating that Tax repression is independent of any potential direct competition with c-Myb for recruitment of CBP/p300 (39). We then investigated whether RelA transcriptional activity was required. To do so, we used NF-κB1/p50 and mutated forms of p50 that retain their ability to interact with RelA but are unable to bind DNA and thereby act as dominant-negative mutants without interfering with the nuclear localization of RelA (6). As previously reported, a low dosage of p50 stimulates NF-κB activation, while higher levels have an inhibitory effect. In experimental conditions in which p50 and p50 mutants were able to inhibit RelA-mediated NF-κB activation in MEF p50−/− cells (Fig. 4D), neither p50 nor p50 mutants were able to prevent RelA from inhibiting c-Myb transactivation (Fig. 4C). These results indicated that de novo NF-κB transcription may not be required for RelA to exert its repressive effect on c-Myb transactivation. Among other members of the NF-κB family tested, c-Rel was also a strong repressor, while RelB acted as a positive regulator of c-Myb-dependent transactivation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

RelA inhibits c-Myb-dependent transactivation independently of its transcriptional activity. (A) MEF RelA−/− cells were transfected with MRE (1 μg) and c-Myb (0.5 μg) in the presence or absence of p65 or Tax (0.25 μg). Protein expression was investigated by Western blotting. (B) MEF RelA−/− cells were transfected with p65 (0.25 μg) or Tax (0.25 μg) and a NF-κB-luciferase reporter construct (NF-κB-Luc) (1 μg). (C) MEF p50−/− cells were transfected with MRE (1 μg), c-Myb (0.5 μg), p65 (0.25 μg), and p50 or the p50 mutant 56/57 or 59/60 (0.5 μg). Protein expression was investigated by Western blotting. (D) MEF p50−/− cells were transfected with p65 (0.25 μg) and p50 or the p50 mutant 56/57 or 59/60 (0.5 μg) along with a NF-κB-luciferase reporter construct (1 μg).

FIG. 5.

Differential effect of the members of the NF-κB family on c-Myb transcription. MEF cells were transfected with MRE (1 μg) along with c-Myb (0.5 μg) and increasing amounts of RelA, c-Rel, or RelB expression vectors as indicated. RL-TK (0.1 μg) was coexpressed to control for transfection efficiency, and luciferase activity was measured 36 h posttransfection.

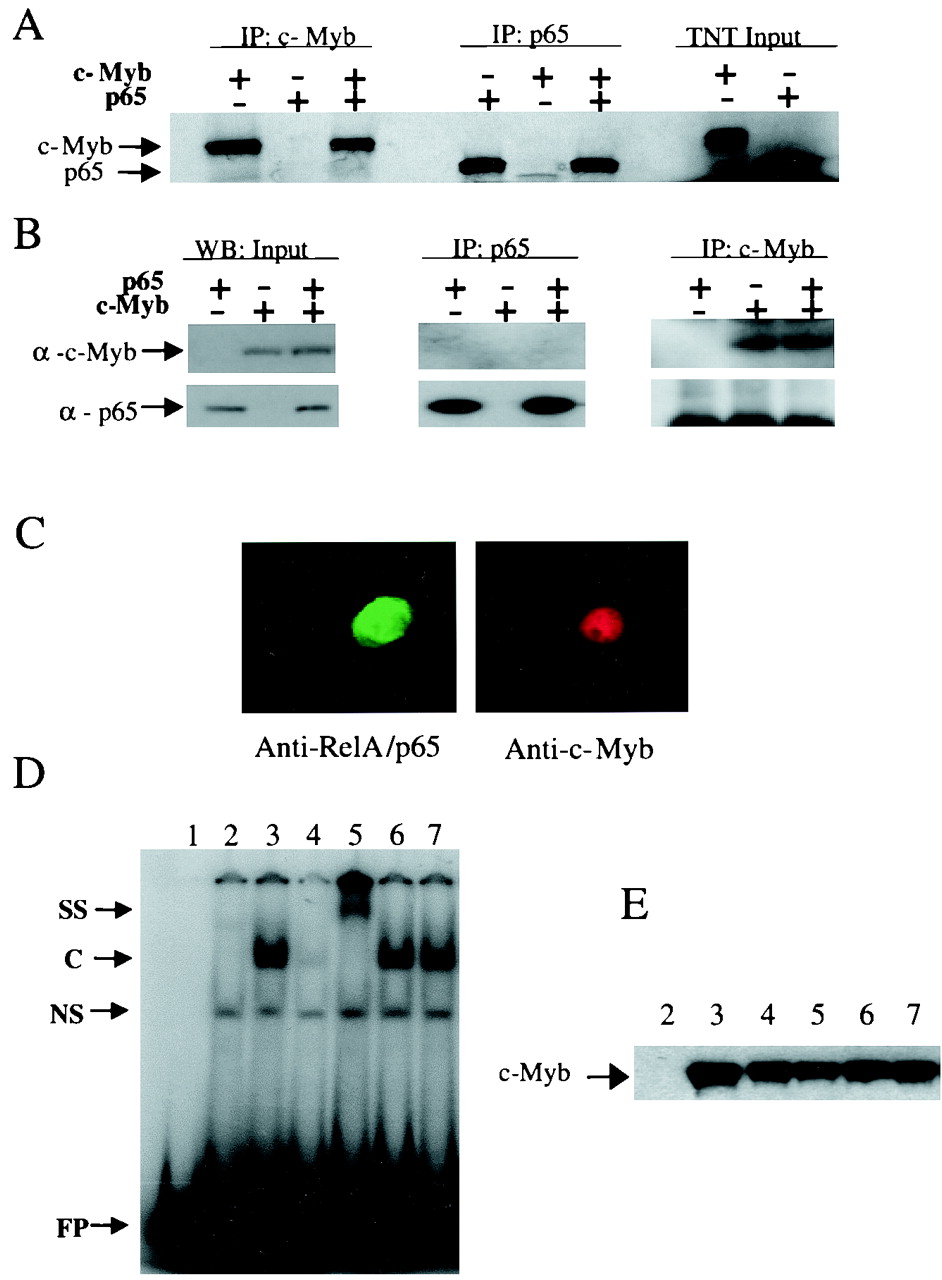

RelA does not bind to c-Myb, nor does it interfere with c-Myb nuclear localization or DNA-binding activity.

We then investigated if the RelA and c-Myb proteins may interact. In vitro-translated radiolabeled RelA and c-Myb proteins were mixed or were incubated separately with specific antibodies. The absence of RelA (Fig. 6A, lane 3) and of c-Myb (Fig. 6A, lane 6) in the immunoprecipitates suggested no direct interaction between these two proteins. However, under similar experimental conditions, interaction of c-Myb or RelA with p300 was detected (Fig. 7C and 8B). Since posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation may be essential for interaction to occur, we performed immunoprecipitation from transfected cells with either RelA or c-Myb or both. No interaction between c-Myb and RelA was detected in vivo (Fig. 6B), while under similar experimental conditions, interaction of c-Myb or RelA with p300 was detected (see Fig. 7C and E). RelA did not alter the nuclear localization of c-Myb, since immunofluorescence detection demonstrated that when c-Myb and RelA were coexpressed, both proteins remained properly localized to the nucleus (Fig. 6C). We next investigated whether RelA might impair the DNA-binding activity of c-Myb. DNA binding activity of c-Myb was analyzed using cell extracts derived from 293T transfected cells (43). Similar levels of c-Myb protein were used in each binding reaction (Fig. 6E). One specific complex in extracts from c-Myb-expressing cells was supershifted or competed for with a c-Myb antibody or excess of unlabeled probe (Fig. 6D, lanes 3, 4, and 5). No significant difference in c-Myb DNA-binding activity could be detected in the absence or the presence of RelA or a mutant of RelA 1-312 (Fig. 6D, lanes 6 and 7). Therefore, RelA-mediated inhibition of c-Myb transactivation was also independent of the DNA-binding activity of c-Myb.

FIG. 6.

RelA does not bind to c-Myb, nor does it interfere with c-Myb nuclear localization or DNA-binding activity. (A) Radiolabeled c-Myb and p65 proteins were synthesized in vitro using rabbit reticulocyte lysate and incubated separately or together in the presence of an antibody specific for either c-Myb or p65. Immunocomplexes were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Input represents 1/10 of the quantity used in the binding reactions. (B) 293T cells were transfected with c-Myb and/or p65. Nuclear protein extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation using specific antibodies and complexes analyzed through SDS-PAGE autoradiography. Input represent a direct Western blot using 1/10 of the protein extracts used in the binding assays. (C) Confocal microscopy immunofluorescence of 293T cells transfected with c-Myb and p65. (D) EMSA using cellular extracts from transfected 293T cells. Lane 1, probe alone; lane 2, pCDNA-transfected 293T protein extract; lane 3, c-Myb-transfected 293T protein extract; lane 4, competition with a 20-fold excess of cold DNA probe; lane 5, supershift using 1 μl of c-Myb mouse monoclonal antibody; lane 6, c-Myb and p65-transfected 293T protein extract; lane 7, c-Myb and p65 mutant truncated for the transactivation domain, 1-312. SS, supershift; C, specific complex of c-Myb with the DNA probe; NS, no specific DNA binding; FP, free probe. (E) Western blot control for the amount of c-Myb protein used in each EMSA binding reaction. Lanes are as defined above.

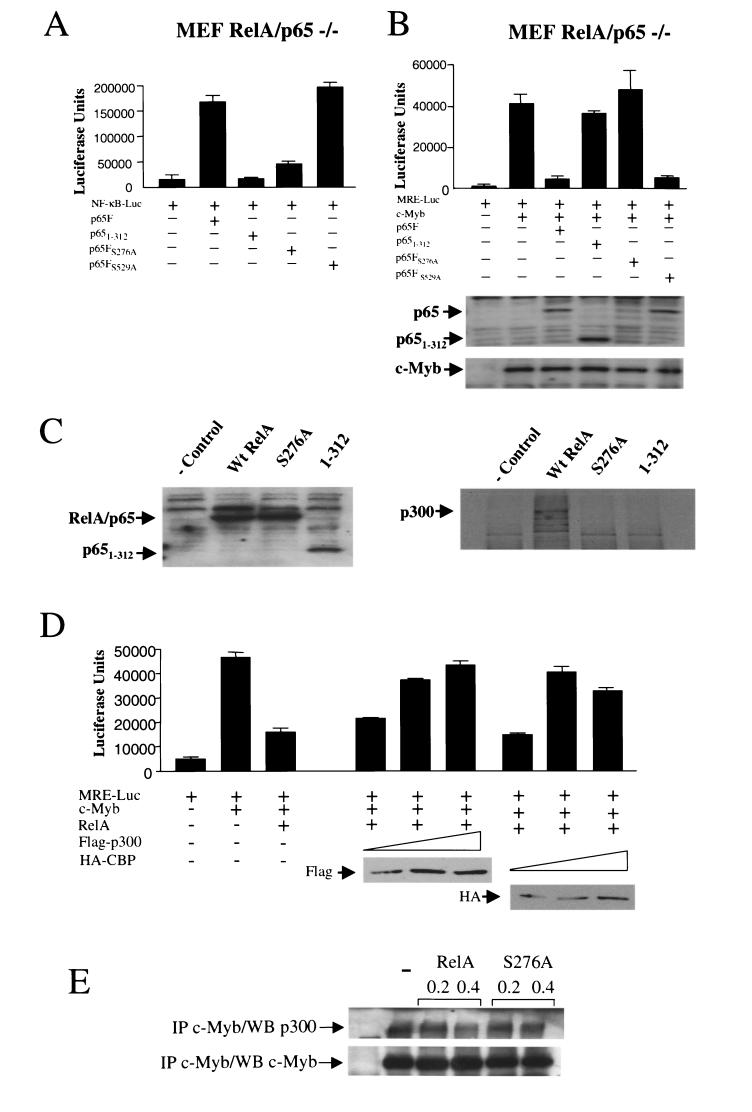

FIG. 7.

Competitive binding of RelA and c-Myb to p300. (A) MEF RelA−/− cells were transfected with p65 or p65 mutants (0.5 μg), an NF-κB-luciferase reporter construct (NF-κB-Luc) (1 μg), and RL-TK (0.1 μg). (B) MEF RelA−/− cells were transfected with MRE (1 μg) and c-Myb (0.5 μg) in the presence or absence of p65 or p65 mutants (0.25 μg) and RL-TK (0.1 μg). Protein expression was investigated by Western blotting. (C) MEF RelA−/− cells were transfected with p65 or p65 mutants, and nuclear extracts were incubated with in vitro-synthesized radiolabeled p300. Immunocomplexes were captured using p65 amino-terminus-specific antibody and resolved through SDS-PAGE, and the gel was dried and exposed for autoradiography. (D) MEF RelA−/− cells were transfected with MRE (1 μg), c-Myb (0.5 μg), p65 (0.25 μg), and increasing amounts of p300 or CBP (0.2, 0.4, and 0.6 μg) and RL-TK (0.1 μg). (E) 293T cells were transfected with c-Myb (1 μg), p65 (0.5 μg), or p65 S276A (2 μg) and p300 (2 μg), and the cell lysate was subjected to immunoprecipitation using c-Myb mouse monoclonal antibody and analyzed by Western blotting.

RelA suppresses c-Myb transactivation through competitive binding of the coactivators CBP/p300.

Recent studies have reported phosphorylation of RelA on serines 276 and 529 (62, 68) and that phosphorylation of serine 276 is essential for efficient binding of RelA to CBP/p300 (68). Along with mutants in which these serines were replaced by alanines, we also tested a RelA mutant lacking the transactivation domain referred to as 1-312. When expressed in MEF RelA−/− cells, wild-type RelA and the S529A mutant were able to activate transcription from the NF-κB-Luc construct, the S276A mutant was greatly attenuated, and the 1-312 mutant was completely inactive (Fig. 7A). Levels of c-Myb protein were not affected by expression of RelA and mutants. The RelA S276A mutant was consistently expressed at a lower level than other RelA constructs (Fig. 7B). However, an increased amount of transfected DNA that allowed comparable protein expression (about fourfold) did not result in any further increase in NF-κB activation and did not repress c-Myb transactivation. Compelling evidence indicates that CBP/p300 are rate limiting in the nucleus, and competition for a limiting pool of CBP/p300 upon NF-κB activation has been previously proposed as a plausible mechanism for transcriptional regulation or induction of apoptosis (21, 22, 26, 38). Since both S276A and 1-312 mutants were unable to inhibit c-Myb transactivation (Fig. 6B), we tested their ability to interact with p300. MEF RelA−/− cells were transfected with wild-type or mutant S276A or 1-312, and cellular extracts normalized for RelA expression (Fig. 7C) were mixed overnight with in vitro-radiolabeled synthesized p300. Because both S276A and 1-312 mutants were defective in binding to p300 (Fig. 7C), we thought that direct interaction between RelA and p300 may be key in inhibiting c-Myb transactivation, possibly through competitive binding. To test that model, we increased the expression of CBP/p300 and found that CBP and p300 were able to rescue RelA-mediated inhibition of c-Myb transactivation in a dosage-dependent manner (Fig. 7D). To further confirm competition, we immunoprecipitated c-Myb in the absence or presence of the RelA or S276A mutant and determined the amounts of p300 present in the complexes. We found that the relative amount of p300 associated with c-Myb decreased when c-Myb was expressed along with RelA but not with the RelA mutant S276A, which is defective for p300 binding (Fig. 7E). Together these results demonstrate the ability of RelA to inhibit c-Myb-dependent transcription through competitive recruitment of coactivator p300.

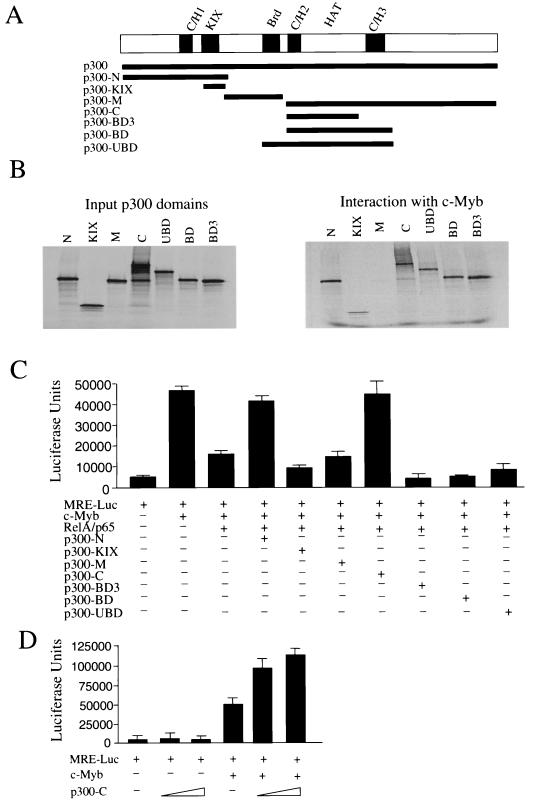

Interaction of c-Myb with the p300 C/H2 domain bypasses RelA repression.

To extend these results, a series of constructs encoding different domains of p300 was used (Fig. 8). In vitro-synthesized p300 fragments were mixed with extracts of untransfected or transfected cells with c-Myb or RelA and immunoprecipitated using antibodies specific for c-Myb or RelA. Consistent with previous reports, both c-Myb and RelA interacted with the full-length p300 protein. Among the different p300 constructs, RelA interacted only with the N fragment containing the C/H1 domain of p300, and, as expected, this construct acted as a dominant negative and inhibited RelA's ability to activate a NF-κB-luciferase reporter (data not shown). In the case of c-Myb, previous studies have identified the KIX domain as the binding site (10, 42). In our experiments, interaction of c-Myb with the minimal KIX domain was weaker than that with the amino-terminal N fragment, suggesting that additional contacts may occur beyond the KIX domain to strengthen the interaction with the amino-terminal region of p300 (Fig. 8B). In these experiments, c-Myb also interacted with the carboxy-terminal region of p300 and with BD3, the minimal C/H2-HAT domain of p300 (Fig. 8B). However, none of these interactions could be detected when untransfected cell protein extracts were used in parallel immunoprecipitation experiments. When the abilities of these p300 domains to overcome RelA repression were assessed, both N and C constructs were able to counter the RelA repressive effect on c-Myb transcription (Fig. 8C). Consistent with the sequestration model, the rescuing function of the p300 N construct presumably results in titration of RelA from endogenous CBP/p300, making it available for c-Myb. However, higher levels of N could also partially suppress c-Myb transcription (data not shown). The effect of the C fragment was more intriguing, since it did not interact with RelA. Thus, we tested whether the C fragment of p300 could act as a functional c-Myb coactivator. Interestingly, c-Myb transcription was stimulated in a dose-dependent manner when expressed along with increasing doses of the p300 carboxy-terminal fragment lacking the KIX domain (C) (Fig. 8D), suggesting an alternative path for the p300 carboxy terminus to act as a c-Myb coactivator.

FIG. 8.

c-Myb interacts with the C/H2-HAT domain of p300. (A) Schematic representation of the different p300 domains encoded by the vectors used. (B) Radiolabeled p300 domains were synthesized in vitro using reticulocyte lysates and mixed with cellular extracts of c-Myb-transfected cells. The left panel shows 1/10 of the input used in the binding assays. The right panel shows the binding observed after immunoprecipitation using mouse monoclonal antibody specific to c-Myb. Immunoprecipitation in the absence of c-Myb was also performed as a control (data not shown). (C) MEF RelA−/− cells were transfected with MRE (1 μg), c-Myb (0.5 μg), p65 (0.25 μg), and vectors expressing different domains of p300 (0.25 μg) and RL-TK (0.1 μg). (D) MEF cells were transfected with MRE (1 μg), with or without c-Myb (0.5 μg) and increased amounts of p300-C construct (0.2 and 0.4 μg) and RL-TK (0.1 μg).

DISCUSSION

This study identifies NF-κB as a novel regulatory pathway for c-Myb transcription and provides a link between extracellular signaling and c-Myb-dependent transcription. A direct or indirect interaction between RelA and c-Myb was excluded by performing immunoprecipitations in vitro and in vivo, and RelA did not affect DNA binding or nuclear localization of c-Myb. RelA's effect seemed to be independent of its transcriptional activity, as dominant-negative mutants of p50 that inhibited RelA-mediated NF-κB activation could not restore c-Myb transcription. The use of RelA mutants unable to bind DNA but retaining their ability to interact with CBP/p300 would definitely ruled out the possibility that any of RelA's transcriptional activities may be required to suppress c-Myb transactivation. The inhibition of c-Myb transactivation by RelA occurred through competition for binding to the coactivators p300/CBP. This model was supported by transfection of a vector expressing the full-length p300 or a deletion mutant expressing the C/H1 domain that restored c-Myb transcription in the presence of RelA. Furthermore, mutants of RelA S276A and 1-312 that were defective in binding p300 were not able to suppress c-Myb activity. Finally, coexpression of c-Myb and RelA but not S276A resulted in lower amounts of p300 complexed with c-Myb, as observed by immunoprecipitation. Importantly, inhibition of endogenous c-Myb transcription was also seen with endogenous RelA induced by different cytokines in Jurkat T cells. Our results suggest that steric interference or conformational changes following binding of RelA to p300 may be responsible for the diminishment of c-Myb binding by blocking access of c-Myb to its binding sites. However, c-Myb was not able to inhibit RelA-mediated NF-κB activation, suggesting that RelA may have a higher affinity than c-Myb for p300 and/or that upon binding of c-Myb to p300, the CH1 domain remains accessible for RelA interaction and c-Myb displacement.

Enforced expression of c-Myb transforms cells that are of a differentiated phenotype, possibly by overriding growth arrest and simultaneously countering apoptotic pathways (50, 63). A definitive correlation between c-Myb transcriptional activity and oncogenic transformation remains uncertain. However, several groups have demonstrated that transcriptional activities of c-Myb are required for transactivation and increased expression of the c-myc, bcl-2, and p15INK4b genes in myeloid cells (9, 59, 63). In such a scenario, c-Myb may indirectly be implicated in a multistep oncogenic process. In fact, although separately Bcl-2 and c-Myc are not very tumorigenic, numerous studies have reported cooperation of these oncogenes in leukemia and lymphoma (19, 49).

Interestingly, different members of the NF-κB family have opposite functions in the regulation of c-Myb expression and activity. While RelA and c-Rel represent strong inhibitors of c-Myb-dependent transcription, RelB acts as a positive regulator and stimulates c-Myb transactivation in a dose-dependent manner. Indeed, IκB molecules also represent positive regulators of c-Myb transcription. The reasons underlying these differences are currently under investigation. Our observation that RelA is a repressor and RelB an activator of c-Myb transcription parallels earlier studies on the regulation of c-myb gene expression. A blockade of transcription elongation in the first intron of the mouse c-myb locus was described previously (4). A correlation between NF-κB factors binding to that pausing site and c-myb mRNA expression was described previously (48). Recently these complexes have been identified as RelB and p50 (4, 53, 54).

In light of these observations, NF-κB appears to play important functions in the regulation of c-myb gene expression as well as c-Myb transcriptional activity.

Interestingly, we found that the carboxy-terminal form of p300 lacking the C/H1 and KIX domains retains its ability to stimulate c-Myb transcription and bypass RelA repression. The possibility that selective mutations in c-Myb that favor interaction with the C/H2 domain, or the presence of truncated forms of p300/CBP lacking the C/H1 domain, may exist in some cancer cells, allowing for c-Myb to bypass NF-κB control, is currently under investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and in part from a fellowship to C. Nicot from La Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (Paris, France). RM was supported by a Bourse Roux from the Pasteur Institute.

We thank L. Wolff and T. Misteli for critical reading of the manuscript. We are indebted to L. Boxer, T. P. Bender, J. S. Lipsick, L. Wolff, C. Kitanaka, S. Ness, W. C. Greene, A. Israel, A. Baldwin, N. Rice, U. Siebenlist, D. Livingston, R. H. Goodman, V. Ogryzko, H. Nakatoni, A. Hoffmann, and D. Baltimore for generous gifts of reagents used in this study. S. Snodgrass provided editorial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akagi T, Ono H, Tsuchida N, Shimotohno K. Aberrant expression and function of p53 in T-cells immortalized by HTLV-1 Tax-1. FEBS Lett. 1997;406:263–266. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00280-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beg A A, Sha W C, Bronson R T, Baltimore D. Constitutive NF-kappa B activation, enhanced granulopoiesis, and neonatal lethality in I kappa B alpha-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1995;22:2736–2746. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beg A A, Sha W C, Bronson R T, Gosh S, Baltimore D. Embryonic lethality and liver degeneration in mice lacking the RelA component of NF-kappa B. Nature. 1995;376:167–170. doi: 10.1038/376167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bender T P, Thompson C B, Kuehl W M. Differential expression of c-myb mRNA in murine B lymphomas by a block to transcription elongation. Science. 1987;237:1473–1476. doi: 10.1126/science.3498214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bies J, Nazarov V, Wolff L. Identification of protein instability determinants in the carboxy-terminal region of c-Myb removed as a result of retroviral integration in murine monocytic leukemias. J Virol. 1999;73:2038–2044. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2038-2044.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bressler P, Brown K, Timmer W, Bours V, Siebenlist U, Fauci A S. Mutational analysis of the p50 subunit of NF-kappa B and inhibition of NF-kappa B activity by trans-dominant p50 mutants. J Virol. 1993;67:288–293. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.288-293.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cereseto A, Washington P R, Rivadeneira E, Franchini G. Limiting amounts of p27Kip1 correlates with constitutive activation of cyclin E-CDK2 complex in HTLV-I-transformed T-cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:2441–2450. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chrivia J C, Kwok R P, Lamb N, Hagiwara M, Montminy M R, Goodman R H. Phosphorylated CREB binds specifically to the nuclear protein CBP. Nature. 1993;365:855–859. doi: 10.1038/365855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cogswell J P, Cogswell P C, Kuehl W M, Cuddihy A M, Bender T M, Engelke U, Marcu K B, Ting J P. Mechanism of c-myc regulation by c-Myb in different cell lineages. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2858–2869. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai P, Akimaru H, Tanaka Y, Hou D X, Yasukawa T, Kanei-Ishii C, Takahashi T, Ishii S. CBP as a transcriptional coactivator of c-Myb. Genes Dev. 1996;10:528–540. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.5.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dash A B, Orrico F C, Ness S A. The EVES motif mediates both intermolecular and intramolecular regulation of c-Myb. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1858–1869. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.15.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckner R, Ewen M E, Newsome D, Gerdes M, DeCaprio J A, Lawrence J B, Livingston D M. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of the adenovirus E1A-associated 300-kD protein (p300) reveals a protein with properties of a transcriptional adaptor. Genes Dev. 1994;8:869–884. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.8.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu S L, Lipsick J S. FAETL motif required for leukemic transformation by v-Myb. J Virol. 1996;70:5600–5610. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5600-5610.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geleziunas R, Ferrell S, Lin X, Mu Y, Cunningham E T, Jr, Grant M, Connelly M A, Hambor J E, Marcu K B, Greene W C. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax induction of NF-κB involves activation of the IκB kinase α (IKKα) and IKKβ cellular kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5157–5165. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gessain A, Barin F, Vernant J C, Gout O, Maurs L, Calender A, De The G. Antibodies to human T-lymphotropic virus type I in patients with tropical spastic paraparesis. Lancet. 1985;ii:407–410. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92734-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gewirtz A M. Myb targeted therapeutics for the treatment of human malignancies. Oncogene. 1999;18:3056–3062. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonda T J, Metcalf D. Expression of myb, myc and fos proto-oncogenes during the differentiation of a murine myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 1984;310:249–251. doi: 10.1038/310249a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guerra J, Withers D A, Boxer L M. Myb binding sites mediate negative regulation of c-myb expression in T-cell lines. Blood. 1995;86:1873–1880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris A W, Strasser A, Bath M L, Elefanty A G, Cory S. Lymphomas and plasmacytomas in transgenic mice involving bcl2, myc and v-abl. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1997;224:221–230. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-60801-8_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedge S P, Kumar A, Kurschner C, Shapiro L H. c-Maf interacts with c-Myb to regulate transcription of an early myeloid gene during differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2729–2737. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horvai A E, Xu L, Korzus E, Brard G, Kalafus D, Mullen T M, Rose D W, Rosenfeld M G, Glass C K. Nuclear integration of JAK/STAT and Ras/AP-1 signaling by CBP and p300. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1074–1079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hottiger M O, Nabel G J. Interaction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat with the transcriptional coactivators p300 and CREB binding protein. J Virol. 1998;72:8252–8256. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8252-8256.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeang K T, Widen S G, Semmes O J, Wilson S H. HTLV-I trans-activator protein, Tax, is a trans-repressor of the human beta-polymerase gene. Science. 1990;247:1082–1084. doi: 10.1126/science.2309119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin D Y, Spencer F, Jeang K T. Human T cell leukemia virus type 1 oncoprotein Tax targets the human mitotic checkpoint protein MAD1. Cell. 1998;93:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin D Y, Giordano V, Kibler K V, Nakano H, Jeang K T. Role of adapter function in oncoprotein-mediated activation of NF-kappaB. Human T-cell leukemia virus type I Tax interacts directly with IkappaB kinase gamma. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17402–17405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamei Y, Xu L, Heinzel T, Torchia J, Kurokawa R, Gloss B, Lin S C, Heyman R A, Rose D W, Glass C K, Rosenfeld M G. A CBP integrator complex mediates transcriptional activation and AP-1 inhibition by nuclear receptors. Cell. 1996;85:403–414. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaspar P, Dvorakova M, Kralova J, Pajer P, Kozmik Z, Dvorak M. Myb-interacting protein, ATBF1, represses transcriptional activity of Myb oncoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14422–14428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemasson I, Robert-Hebmann V, Hamaia S, Duc D M, Gazzolo L, Devaux C. Trans-repression of lck gene expression by human T-cell leukemia virus type 1-encoded p40tax. J Virol. 1997;71:1975–1983. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1975-1983.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lenzmeier B A, Baird E E, Dervan P B, Nyborg J K. The Tax protein-DNA interaction is essential for HTLV-I transactivation in vitro. J Mol Biol. 1999;291:731–744. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leverson J D, Koskinen P J, Orrico F C, Rainio E M, Jalkanen K J, Dash A B, Eisenman R N, Ness S A. Pim-1 kinase and p100 cooperate to enhance c-Myb activity. Mol Cell. 1998;2:417–425. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leverson J D, Ness S A. Point mutations in v-Myb disrupt a cyclophilin-catalyzed negative regulatory mechanism. Mol Cell. 1998;1:203–211. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X H, Gaynor R B. Regulation of NF-kB by the HTLV-1 Tax protein. Gene Exp. 1999;7:233–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lipsick J S, Wang D M. Transformation by v-Myb. Oncogene. 1999;18:3047–3055. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mink S, Kerber U, Klempnauer K H. Interaction of C/EBPβ and v-Myb is required for synergistic activation of the mim-1 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1316–1325. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ness S A. Myb binding proteins: regulators and cohorts in transformation. Oncogene. 1999;18:3039–3046. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ness S A, Marknell A, Graf T. The v-myb oncogene product binds to and activates the promyelocyte-specific mim-1 gene. Cell. 1989;59:1115–1125. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90767-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neuveut C, Low K G, Maldarelli F, Schmitt I, Majone F, Grassmann R, Jeang K T. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax and cell cycle progression: role of cyclin D-cdk and p110Rb. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3620–3632. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nicot C, Harrod R. Distinct p300-responsive mechanisms promote caspase-dependent apoptosis by human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 Tax protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8580–8589. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.22.8580-8589.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicot C, Mahieux R, Opavsky R, Cereseto A, Wolff L, Brady J N, Franchini G. HTLV-I Tax transrepresses the human c-Myb promoter independently of its interaction with CBP or p300. Oncogene. 2000;19:2155–2164. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nicot C, Opavsky R, Mahieux R, Johnson J M, Brady J N, Wolff L, Franchini G. Tax oncoprotein trans-represses endogenous B-myb promoter activity in human T cells. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2000;16:1629–1632. doi: 10.1089/08892220050193065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nicot C, Mahieux R, Takemoto S, Franchini G. Bcl-X(L) is up-regulated by HTLV-I and HTLV-II in vitro and in ex vivo ATLL samples. Blood. 2000;96:275–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oelgeschlager M, Janknecht R, Krieg J, Schreek S, Luscher B. Interaction of the co-activator CBP with Myb proteins: effects on Myb-specific transactivation and on the cooperativity with NF-M. EMBO J. 1996;15:2771–2780. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oelgeschlager M, Krieg J, Luscher-Firzlaff J M, Luscher B. Casein kinase II phosphorylation site mutations in c-Myb affect DNA binding and transcriptional cooperativity with NF-M. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5966–5974. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.5966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oelgeschlager M, Nuchprayoon I, Luscher B, Friedman A D. C/EBP, c-Myb, and PU.1 cooperate to regulate the neutrophil elastase promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4717–4725. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osame M, Usuku K, Izumo S, Ljichi N, Amitani H, Igata A, Matsumoto M, Tara M. HTLV-I associated myelopathy, a new clinical entity. Lancet. 1986;i:1031–1032. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poiesz B J, Ruscetti F W, Gazdar A F, Bunn P A, Minna J D, Gallo R C. Detection and isolation of type C retrovirus particles from fresh and cultured lymphocytes of a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:7415–7419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Postigo A A, Sheppard A M, Mucenski M L, Dean D C. c-Myb and Ets proteins synergize to overcome transcriptional repression by ZEB. EMBO J. 1997;16:3924–3934. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reddy C D, Reddy E P. Differential binding of nuclear factors to the intron 1 sequences containing the transcriptional pause site correlates with c-myb expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7326–7330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reed J C, Cuddy M, Haldar S, Croce C, Nowell P, Makover D, Bradley K. BCL2-mediated tumorigenicity of a human T-lymphoid cell line: synergy with MYC and inhibition by BCL2 antisense. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3660–3664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidt M, Nazarov V, Stevens L, Watson R, Wolff L. Regulation of the resident chromosomal copy of c-myc by c-Myb is involved in myeloid leukemogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1970–1981. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.6.1970-1981.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sha W C, Liou H C, Tuomanen E I, Baltimore D. Targeted disruption of the p50 subunit of NF-kappa B leads to multifocal defects in immune responses. Cell. 1995;80:321–330. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith M R, Greene W C. Identification of HTLV-I tax trans-activator mutants exhibiting novel transcriptional phenotypes. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1875–1885. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.11.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suhasini M, Pilz R B. Transcriptional elongation of c-myb is regulated by NF-kappaB (p50/RelB) Oncogene. 1999;18:7360–7369. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suhasini M, Reddy C D, Reddy E P, DiDonato J A, Pilz R B. cAMP-induced NF-kappaB (p50/relB) binding to a c-myb intronic enhancer correlates with c-myb up-regulation and inhibition of erythroleukemia cell differentiation. Oncogene. 1997;15:1859–1870. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun S C, Ganchi P A, Ballard D W, Greene W C. NF-kappa B controls expression of inhibitor I kappa B alpha: evidence for an inducible autoregulatory pathway. Science. 1993;259:1912–1915. doi: 10.1126/science.8096091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suzuki T, Kitao S, Matsushime H, Yoshida M. HTLV-1 Tax protein interacts with cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4A and counteracts its inhibitory activity towards CDK4. EMBO J. 1996;15:1607–1614. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanaka Y, Naruse I, Maekawa T, Masuya H, Shiroishi T, Ishii S. Abnormal skeletal patterning in embryos lacking a single Cbp allele: a partial similarity with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10215–10220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tavner F J, Simpson R, Tashiro S, Favier D, Jenkins N A, Gilbert D J, Copeland N G, Macmillan E M, Lutwyche J, Keough R A, Ishii S, Gonda T J. Molecular cloning reveals that the p160 Myb-binding protein is a novel, predominantly nucleolar protein which may play a role in transactivation by Myb. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:989–1002. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taylor D, Badiani P, Weston K. A dominant interfering Myb mutant causes apoptosis in T cells. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2732–2744. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tong X, Drapkin R, Yalamanchili R, Mosialos G, Kieff E. The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 acidic domain forms a complex with a novel cellular coactivator that can interact with TFIIE. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4735–4744. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Verbeek W, Gombart A F, Chumakov A M, Muller C, Friedman A D, Koeffler H P. C/EBPε directly interacts with the DNA binding domain of c-myb and cooperatively activates transcription of myeloid promoters. Blood. 1999;93:3327–3337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang D, Baldwin A S., Jr Activation of nuclear factor-kappaB-dependent transcription by tumor necrosis factor-alpha is mediated through phosphorylation of RelA/p65 on serine 529. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29411–29416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wolff L, Schmidt M, Koller R, Haviernick P, Watson R, Bies J, Maciag K. Three genes with different functions in transformation are regulated by c-Myb in myeloid cells. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2001;27:422–428. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2001.0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiao G, Harhaj E W, Sun S C. Domain-specific interaction with IkappaB kinase (IKK) regulatory subunit IKK gamma is an essential step in Tax-mediated activation of IKK. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34060–34067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002970200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yamaoka S, Courtois G, Bessia C, Whiteside S T, Weil R, Agou F, Kirk H E, Kay R J, Israel A. Complementation cloning of NEMO, a component of the IkappaB kinase complex essential for NF-kappaB activation. Cell. 1998;93:1231–1240. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81466-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yao T P, Oh S P, Fuchs M, Zhou N D, Ch'ng L E, Newsome D, Bronson R T, Li E, Livingston D M, Eckner R. Gene dosage-dependent embryonic development and proliferation defects in mice lacking the transcriptional integrator p300. Cell. 1998;93:361–372. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yin M J, Christerson L B, Yamamoto Y, Kwak Y T, Xu S, Mercurio F, Barbosa M, Cobb M H, Gaynor R B. HTLV-I Tax protein binds to MEKK1 to stimulate IkappaB kinase activity and NF-kappaB activation. Cell. 1998;93:875–884. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81447-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhong H, Voll R E, Ghosh S. Phosphorylation of NF-kappa B p65 by PKA stimulates transcriptional activity by promoting a novel bivalent interaction with the coactivator CBP/p300. Mol Cell. 1998;1:661–671. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]