Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) outcomes vary greatly among individuals, but most of the variation remains unexplained. Using a Drosophila melanogaster TBI model and 178 genetically diverse lines from the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel (DGRP), we investigated the role that genetic variation plays in determining TBI outcomes. Following injury at 20–27 days old, DGRP lines varied considerably in mortality within 24 h (“early mortality”). Additionally, the disparity in early mortality resulting from injury at 20–27 vs 0–7 days old differed among DGRP lines. These data support a polygenic basis for differences in TBI outcomes, where some gene variants elicit their effects by acting on aging-related processes. Our genome-wide association study of DGRP lines identified associations between single nucleotide polymorphisms in Lissencephaly-1 (Lis-1) and Patronin and early mortality following injury at 20–27 days old. Lis-1 regulates dynein, a microtubule motor required for retrograde transport of many cargoes, and Patronin protects microtubule minus ends against depolymerization. While Patronin mutants did not affect early mortality, Lis-1 compound heterozygotes (Lis-1x/Lis-1y) had increased early mortality following injury at 20–27 or 0–7 days old compared with Lis-1 heterozygotes (Lis-1x/+), and flies that survived 24 h after injury had increased neurodegeneration but an unaltered lifespan, indicating that Lis-1 affects TBI outcomes independently of effects on aging. These data suggest that Lis-1 activity is required in the brain to ameliorate TBI outcomes through effects on axonal transport, microtubule stability, and other microtubule proteins, such as tau, implicated in chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a TBI-associated neurodegenerative disease in humans.

Keywords: Drosophila melanogaster, genome-wide association study, Lissencephaly-1, microtubule, neurodegeneration, nudE, Patronin, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a complex disorder affecting millions of people each year (Johnson and Griswold 2017; Dewan et al. 2018). Physical, behavioral, cognitive, and emotional consequences of TBI stem from primary mechanical injuries to the brain as well as subsequent molecular and cellular cascades that lead to secondary injuries to the brain and other organs over time (Thapa et al. 2021). Both primary and secondary injuries vary considerably among individuals, making TBI outcomes difficult to predict and treat (Wagner 2014; Pavlovic et al. 2019; Cortes and Pera 2021). Despite decades of research, no treatments have been developed that improve neurological outcomes of TBI (Chakraborty et al. 2016; Hawryluk and Bullock 2016).

Genetic variation among individuals is likely a main cause of heterogeneity in TBI outcomes as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in numerous genes, including apolipoprotein E4 (apoE4), neurotransmitter-related genes, cytokine genes, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and mitochondrial genes are associated with differential TBI outcomes (Cortes and Pera 2021; Gomez et al. 2021; Zeiler et al. 2021). Furthermore, studies in rodent TBI models show that identical primary injuries in different genetic backgrounds produce different outcomes (Fox et al. 1999; Tan et al. 2009; Reid et al. 2010; Al Nimer et al. 2013). However, broad validation of candidate modifier genes is yet to be realized.

Age at the time of primary injury also contributes to heterogeneity in TBI outcomes. The risk of mortality shortly after TBI increases with age at the time of primary injury (Hukkelhoven et al. 2003; Dhandapani et al. 2012; Skaansar et al. 2020), as does the risk of dementia (Gardner et al. 2014; Johnson and Stewart 2015). In addition, changes in gene expression following TBI are age-dependent in humans (Cho et al. 2016) and mice (Hazy et al. 2019). Furthermore, TBI may itself accelerate the aging process (Smith et al. 2013). For example, TBI increases the rate of brain atrophy that normally occurs during aging (Cole et al. 2015). Acceleration of aging processes by TBI may explain the increased susceptibility of TBI patients to dementia and other age-associated pathologies.

TBI shares pathological features such as intracellular aggregates of tau protein in the brain with Alzheimer's disease. The microtubule-associated protein tau is abundant in axons where it promotes microtubule self-assembly and protects microtubules against depolymerization (Alonso et al. 2018; Barbier et al. 2019). In Alzheimer's disease, tau is abnormally hyperphosphorylated, leading to its self-aggregation into neurofibrillary tangles in neurons and glia (Naseri et al. 2019). Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a neurogenerative disease associated with repetitive mild TBI, is characterized by four stages of accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau, ranging from discrete foci at the depths of sulci in the cerebral cortex (Stage I) to widespread foci in most regions of the cerebral cortex and the medial temporal lobe (Stage IV) (McKee et al. 2015; McKee 2020). Tau hyperphosphorylation inhibits axonal transport of cargo, such as vesicles and organelles along microtubules to and from synapses (Alonso et al. 2018; Barbier et al. 2019). Axonal transport is also disrupted by breaks in microtubules caused by brain deformation and axonal stretching. A common feature of TBI is diffuse axonal injury, which is characterized by periodic swellings along axons that, in an in vitro cortical neuron stretching model, result from breaks in microtubules (Tang-Schomer et al. 2010; Smith et al. 2013). In this model, depolymerization of microtubules at break points interrupts axonal transport and causes neurodegeneration, which is reduced by the microtubule-stabilizing drug taxol (Tang-Schomer et al. 2010; Johnson et al. 2013). Paclitaxel, another microtubule-stabilizing drug, improves motor function and reduces lesion size and cognitive impairment in a mouse TBI model (Cross et al. 2015, 2019). These findings indicate that the transport of cargo along microtubules and microtubule stability influences the consequences of TBI.

We developed a Drosophila melanogaster TBI model to investigate the role of genetic variation in determining individual differences in TBI outcomes. The fly TBI model uses a spring-based high-impact trauma (HIT) device to inflict closed-head injuries rapidly and reproducibly in adult flies (Katzenberger et al. 2013; Katzenberger et al. 2015b). TBI in flies, as in humans, causes neuropathologies, including prolonged neuroinflammation mediated by nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) transcription factors (Simon et al. 2017; Swanson et al. 2020; Buhlman et al. 2021). Heterozygosity for a null mutation of Relish, one of three NF-κB genes in Drosophila, reduces the risk of mortality within 24 h of the primary injury (“early mortality”) (Swanson et al. 2020). Additionally, our genome-wide association study (GWAS) of inbred, fully sequenced lines from the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel (DGRP) revealed that early mortality following injury of 0–7 day old flies is associated with SNPs in genes involved in tissue barrier function and glucose homeostasis (Mackay et al. 2012; Katzenberger et al. 2015a). Other studies showed that diet and age alter early mortality through genetically separable mechanisms (Katzenberger et al. 2016; Blommer et al. 2021). Thus, the HIT device model and other fly TBI models make it possible to perform unbiased screens for DNA polymorphisms that affect the risk of TBI outcomes (Katzenberger et al. 2013; Barekat et al. 2016; Sun and Chen 2017; Putnam et al. 2019; Sanuki et al. 2019; Saikumar et al. 2020; Behnke et al. 2021; Crocker et al. 2021; van Alphen et al. 2022).

With the goal of understanding how genetic variation and age modify TBI outcomes, we repeated our prior GWAS of DGRP lines with flies injured at 20–27 days old, instead of 0–7 days old. SNPs that were significantly associated with early mortality following TBI mapped to Patronin, whose encoded protein stabilizes the minus ends of non-mitotic microtubules (Goodwin and Vale 2010; Akhmanova and Steinmetz 2019), and Lissencephaly-1 (Lis-1), which encodes a regulator of the microtubule motor dynein (Olenick and Holzbaur 2019; Markus et al. 2020). Patronin mutations did not affect early mortality, but Lis-1 mutations enhanced early mortality and neurodegeneration, indicating that in addition to tau, at least one other microtubule-associated protein influences the nature and severity of TBI outcomes.

Materials and methods

Fly lines and culturing

Flies were maintained in humidified incubators at 25°C on cornmeal-molasses-yeast food, as described by Katzenberger et al. (2015a) and Blommer et al. (2021). DGRP, Lis-1, nudE, Patronin, tubulin-Gal4, and UAS-Lis-1 fly lines were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Supplementary Table 2). Lis-1E415 and UAS-GFP-Patronin flies were provided by Dirk Beuchle (Institut für Zellbiologie, Bern, Switzerland) and Carole Seum (University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland), respectively. w1118 flies were obtained from Gerald Rubin's lab (University of California-Berkeley) in 1996 and maintained in the Wassarman.

TBI and the MI24

Flies were injured using a HIT device as described by Katzenberger et al. (2013; Katzenberger et al. 2015b). In brief, vials containing 60 flies (approximately 30 males and 30 females) at 20–27 or 0–7 days old were injured by 4 strikes at 5 min intervals with the spring deflected to 90°. Injured flies were transferred to vials containing cornmeal-molasses-yeast food and cultured at 25°C. The Mortality Index at 24 h (MI24) was calculated by subtracting the percent of uninjured flies that died from the percent of injured flies that died during the 24 h following TBI. A minimum of six biological replicates were analyzed for each condition, except for, in Fig. 1, where three biological replicates were analyzed.

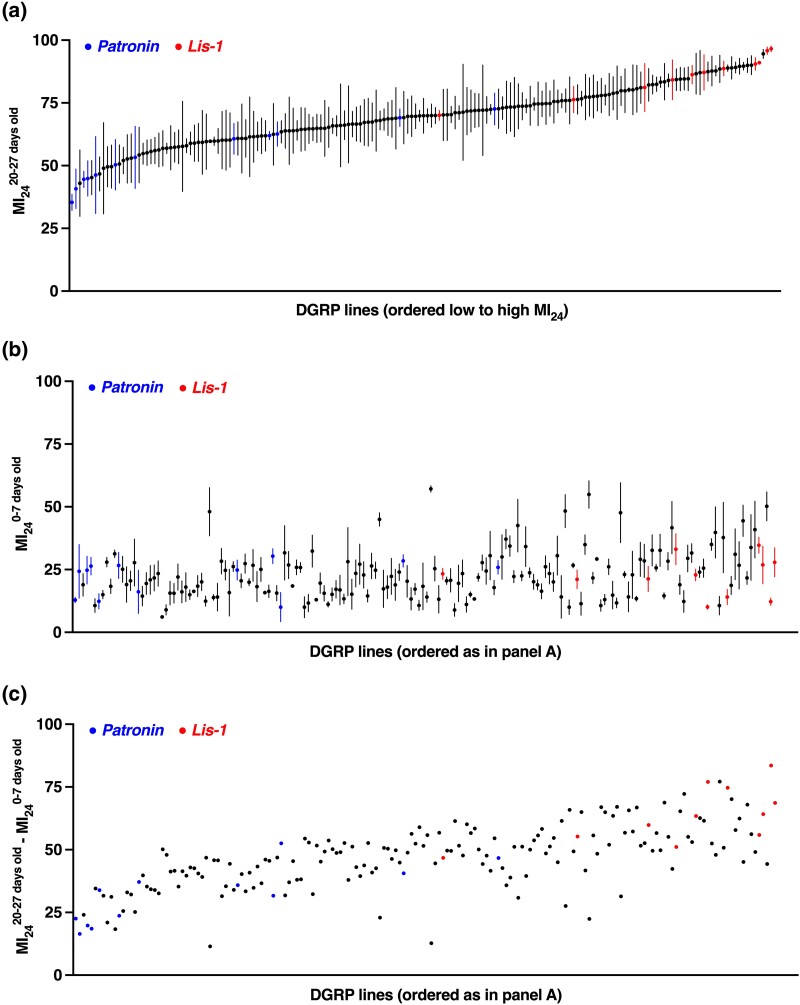

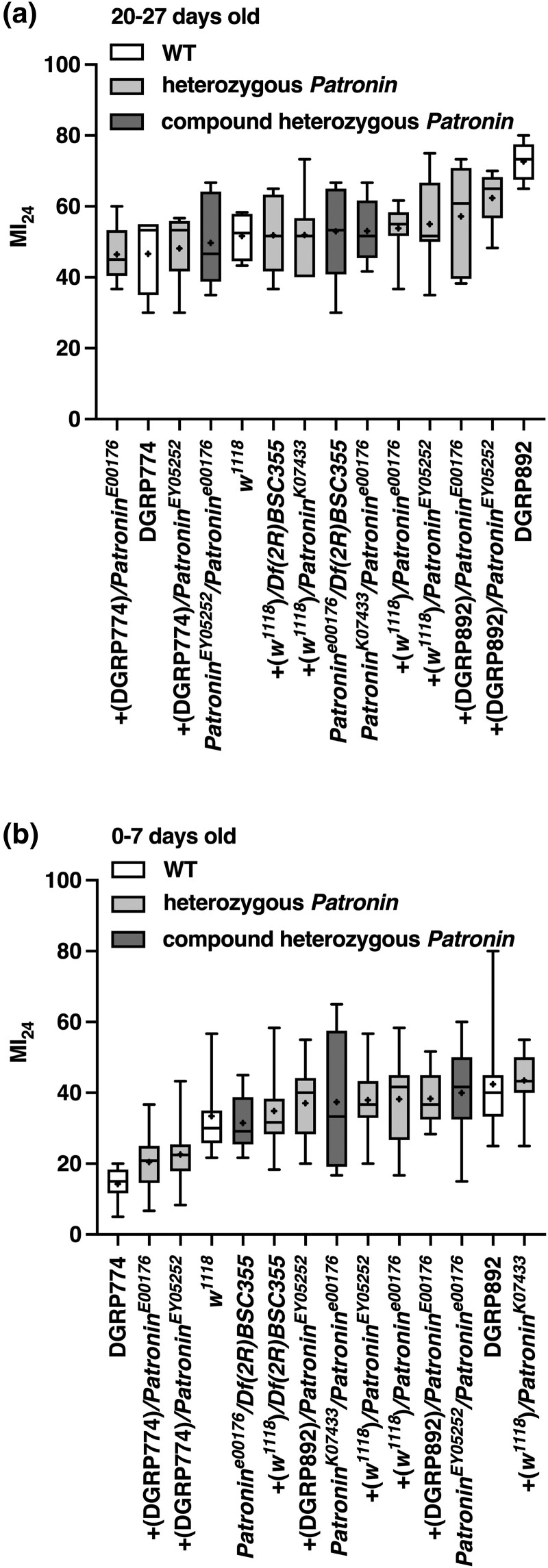

Fig. 1.

Genotype affects the MI24 of flies injured at 20–27 days old and the difference in MI24 between flies injured at 20–27 vs 0–7 days old. a) Mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) of the MI24 for 178 DGRP lines injured using the standard TBI protocol at 20–27 days old (n = 3). Supplementary Table 1 lists MI24 values for each DGRP line. b) Mean and SEM of the MI24 for 178 DGRP lines injured at 0–7 days old (n = 3). Supplementary Table 1 and Katzenberger et al. (2015a) list MI24 values for each DGRP line. c) The difference in MI24 values between flies injured at 20–27 and 0–7 days old. DGRP lines are ordered the same as in panels A and B.

GWAS

The MI24 of 178 DGRP lines was determined using 60 mixed-sex flies injured at 20–27 or 0–7 days old (Katzenberger et al. 2015a). Three replicates were performed sequentially, with each replicate consisting of testing all 178 lines. Average MI24 values for the three replicates were used to identify SNPs associated with the MI24 using the DGRP Freeze 1 web tools (Mackay et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2014).

qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on total RNA extracted from male flies, either 20 whole flies or 60 fly heads. RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) and QIAshredder (Qiagen). cDNA was generated using 1 μg of RNA in a 20 μl reverse transcription (RT) reaction using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad). Each 25 μl qPCR sample contained 0.5 μl cDNA, 12.5 μl iQ SYBP Green Supermix (Bio-Rad), and 250 nM primers. Reactions were carried out using an iCycler Thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). PCR cycling conditions were 95°C for 3 min, followed by cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 61°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Melt curves were used to evaluate the homogeneity of reaction products. PCR primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Table 3. The delta-delta Ct method was used to determine the relative fold difference in gene expression (Livak and Schmittgen 2001).

Western blot

Western blot analyses were performed as described in Loewen and Ganetzky (2018) with the following modifications. Ten heads from male flies were homogenized in 100 μl of 2X Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad), containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol. Samples were boiled for 5 min and centrifuged at 13,200 rpm for 1 min. A sample supernatant of 15 μl was electrophoresed in a Bolt 4–12% Bis-Tris Plus Gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to an iBlot 2 PVDF membrane (Invitrogen). Membranes were blocked with 1X Blocking Buffer (Odyssey Blocking Buffer, Li-Cor) for 1 h. Blots were probed with both a rabbit anti-Lis-1 antibody (ab82607, Abcam) and a rabbit anti-Patronin antibody (provided by Carole Seum, University of Geneva) (Derivery et al. 2015). Primary antibodies were used at a 1:1,000 dilution in a 1:1 Blocking Buffer:1X PBST (phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 2% Tween 20) solution overnight at 4°C. Blots were washed four times for 10 min in 1X PBST. Blots were probed with a secondary antibody, IRDye 800 donkey anti-rabbit (Li-Cor), at a 1:10,000 dilution in Blocking Buffer plus 0.1% SDS for 2 h at room temperature. Blots were washed four times 10 min in 1X PBST and one time in 1X PBS. Blots were imaged on an Li-Cor Odyssey Imaging System, and the intensity of bands was quantified using Image Studio Lite, version 5.2.5. Blots were stripped using NewBlot PVDF Stripping Buffer (Li-Cor) and re-probed using mouse anti-α-tubulin 12G10 antibody (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) at a 1:2,000 dilution and a secondary antibody, IRDye 800 donkey anti-mouse (Li-Cor), at a 1:10,000 dilution, and re-imaged and quantified.

Lifespan

The lifespan of adult mixed-sex flies that survived 24 h following TBI was determined using at least 100 flies per genotype (i.e. 5 vials with 20 flies each) (Table 2). The number of surviving flies was counted each weekday until all flies had died. Flies were transferred to new vials approximately every 3 days. Flies were considered dead if they did not show obvious locomotor activity. Statistical analysis of survival by the Kaplan–Meier Fisher's exact test was performed using OASIS 2 (Online Application for Survival Analysis 2).

Table 2.

Median lifespan data from Supplementary Fig. 6.

| Genotype | Injury | Median lifespan (days) | n | P-value at mediana |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +(w1118)/Lis-1G10.14 | − | 55.4 ± 3.5 | 369 | 2.2 × 10−12 |

| + | 42.3 ± 2.2 | 344 | ||

| +(w1118)/Df(2R)Jp8 | − | 44.3 ± 2.0 | 337 | 4.1 × 10−7 |

| + | 38.7 ± 3.6 | 354 | ||

| +(w1118)/Lis-1K11702 | − | 59.9 ± 3.9 | 197 | 2.4 × 10−3 |

| + | 50.6 ± 2.9 | 227 | ||

| +(w1118)/Lis-1K13209 | − | 64.9 ± 4.5 | 249 | 1.5 × 10−12 |

| + | 50.5 ± 3.7 | 250 | ||

| Lis-1K13209 /Lis-1G10.14 | − | 50.4 ± 3.8 | 220 | 2.5 × 10−2 |

| + | 45.9 ± 6.1 | 173 | ||

| Lis-1K13209 /Df(2R)Jp8 | − | 57.5 ± 7.6 | 192 | 9.7 × 10−6 |

| + | 42.5 ± 6.5 | 145 | ||

| Lis-1K13209 /Lis-1K11702 | − | 50.0 ± 4.5 | 148 | 3.0 × 10−4 |

| + | 34.3 ± 7.4 | 124 | ||

| Lis-1G10.14 /Df(2R)Jp8 | − | 62.5 ± 3.8 | 118 | 7.4 × 10−6 |

| + | 47.5 ± 4.1 | 251 |

Comparison of uninjured vs injured using Kaplan–Meier Fisher's exact test.

Histology and neuropathology

Heads of female flies two weeks after injury at 0–7 days old were hand dissected using a scalpel and incubated in ethanol:chloroform:acetic acid (6:3:1) at room temperature overnight. Heads were then incubated in 70% ethanol, processed into paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin (Harris modified with acetic acid; Fisher) and eosin (Eosin Y powder; Polysciences), as described by Kretzchmar et al. (1997). Single sections at the same depth were imaged using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M inverted microscope and scored for the number of >5 μm holes. Six brains were examined for each genotype.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8, except for lifespan analysis (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig 6), which was performed using OASIS 2 (Online Application for Survival Analysis 2).

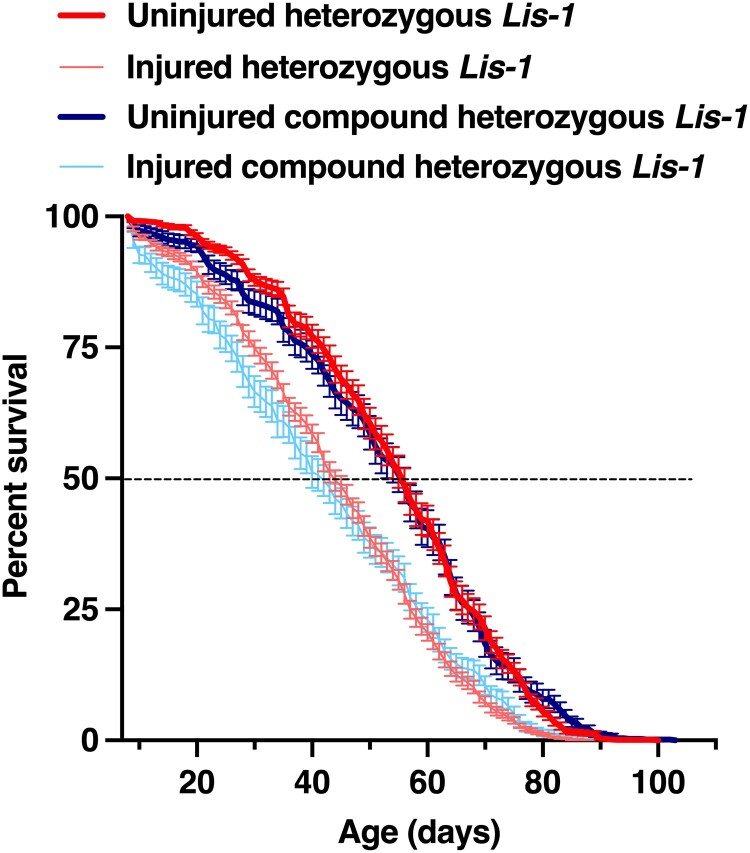

Fig. 6.

Lis-1 mutations do not affect lifespan following TBI. Percent survival of mixed-sex Lis-1 mutants either uninjured or injured using the standard TBI protocol. Data are averages and SEM of four Lis-1x/+ heterozygous and four Lis-1x/Lis-1y compound heterozygous genotypes shown in Table 2. Heterozygous Lis-1 mutants were generated by crossing Lis-1 mutants to the w1118 line. For each genotype, at least 100 flies were examined in groups of 20. Lifespan analysis of individual Lis-1 mutant genotypes is shown in Supplementary Fig. 6.

Results

Genotype affects the risk of early mortality following injury at 20–27 days old

To investigate the influence of genotype on early mortality following TBI in older flies, we determined the MI24 of DGRP lines injured at 20–27 day old, which is about half of the average lifespan of DGRP lines raised at 25°C (Huang et al. 2020). The MI24—a measure of early mortality due to injury—is the percent mortality of injured flies minus the percent mortality of uninjured flies at 24 h following TBI. Figure 1a and Supplementary Table 1 show MI24 values for 178 DGRP lines injured using the standard TBI protocol, four strikes from the HIT device with 5 min between strikes. Every line was independently tested three times with 60 mixed-sex flies, as the MI24 does not differ between males and females (Katzenberger et al. 2013; Blommer et al. 2021). MI24 values had a continuous distribution among the lines, ranging from 35.39 ± 1.85 to 96.54 ± 0.68, suggesting a polygenic basis for the variation.

Across genotypes, risk of early mortality following TBI is higher for older flies

Contemporaneously with the study of flies injured at 20–27 days old, we performed and published an analogous study of the same DGRP lines injured at 0–7 days old (Katzenberger et al. 2015a). MI24 values of flies injured at 0–7 days old ranged from 6.67 ± 6.7 to 57.53 ± 1.7 (Fig. 1b). To evaluate the effect of aging on the MI24, we calculated the difference in MI24 between flies injured at 20–27 vs 0–7 days old (MI2420–27 days old—MI240–7 days old). For every DGRP line, older flies had a higher MI24 than younger flies (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, the difference in MI24 varied greatly among the lines from 11.48 to 83.58 with a mean of 47.02 ± 13.32, but there was a positive correlation between MI24 values of flies injured at 20–27 vs 0–7 days old (r = 0.28) (Supplementary Fig. 1). These data support the conclusion from our prior studies that aging-related processes either inhibit recovery from or exacerbate the deleterious effects of primary and secondary injures (Katzenberger et al. 2013, 2016).

Wolbachia status does not affect early mortality following TBI

We considered the possibility that some extraneous factor unrelated to genetic background could be affecting TBI outcomes among the various DGRP lines. One plausible candidate was infection by Wolbachia pipientis, a maternally inherited endosymbiotic bacterium that infects at least 20% of insect species (Stouthamer et al. 1999). Wolbachia infection in D. melanogaster increases resistance to infection by RNA viruses (Teixeira et al. 2008) and is associated with acute and chronic resistance to oxidative stress in DGRP lines, ∼53% of which are infected with Wolbachia (Jordan et al. 2012; Weber et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2014). However, the full extent of the effect of Wolbachia on D. melanogaster development and physiology is unknown. To test whether Wolbachia contributes to variation in MI24, we reanalyzed the data in Figs. 1a and 1b based on Wolbachia status. We found that the mean and variance of MI24 values of Wolbachia positive (n = 84) and negative (n = 94) lines were similar for flies injured at 20–27 days old (positive: 67.85 ± 11.99, negative: 71.74 ± 12.37) and at 0–7 days old (positive: 22.64 ± 9.76, negative: 22.74 ± 9.08) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Therefore, Wolbachia infection does not appear to be a determinant of differences in MI24 among DGRP lines. This conclusion is supported by our prior finding that feeding flies antibiotics to eliminate endogenous bacteria did not affect the MI24 of DGRP lines (Katzenberger et al. 2015a).

SNPs in LIS-1 and Patronin are associated with early mortality following TBI

To identify DNA polymorphisms that might affect the MI24 of DGRP lines injured at 20–27 days old, we used the DGRP webserver to carry out GWAS of the MI24 data shown in Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1 (Mackay et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2014). 16 minor SNPs that mapped to 14 genes were associated with the MI24 at a discovery significance threshold of P < 10−5 (Table 1). Although the lack of overlap between the 16 significant SNPs and the 216 significant SNPs identified by GWAS of DGRP lines injured at 0–7 days old (Katzenberger et al. 2015a) suggests that distinct genes influence early mortality at different ages of injury, this conclusion is refuted for at least one gene by data in Fig. 3.

Table 1.

Genes containing SNPs associated with the MI24 of DGRP lines.

| Fly gene | Human ortholog | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Patronin | CAMSAP1-3, Nezha | 3.79 × 10−7 |

| Lissencephaly-1 (Lis-1) | Lis-1, PAFAH1B1 | 1.75 × 10−6 |

| Sidestep VIII (side-VIII) | Unknown | 2.81 × 10−6 |

| CG15765 | Unknown | 4.47 × 10−6 |

| CG3687/CG7786 | Unknown | 4.63 × 10−6 |

| GEFmeso | PLEKHG1-3 | 5.86 × 10−6 |

| CG11883 | Unknown | 6.13 × 10−6 |

| teashirt (tsh) | TSHZ1-3 | 6.29 × 10−6 |

| Nuclear pore localization 4 (Npl4) | NPL4 | 7.38 × 10−6 |

| meru /pH-sensitive chloride channel 1 (pHCL-1) | RASSF9-10 /GLRA2-4 | 7.82 × 10−6 |

| CG42663, NCK-associated protein 5-like | NCKAP5 | 8.27 × 10−6 |

| Apoptosis-stimulating proteins of p53 (ASPP) | ASPP1-2 | 8.78 × 10−6 |

| CG14759/CG30369 | Unknown | 9.63 × 10−6 |

| CG4597 a | Unknown | 9.72 × 10−6 |

/, genes associated with the same SNP.

gene with three associated SNPs.

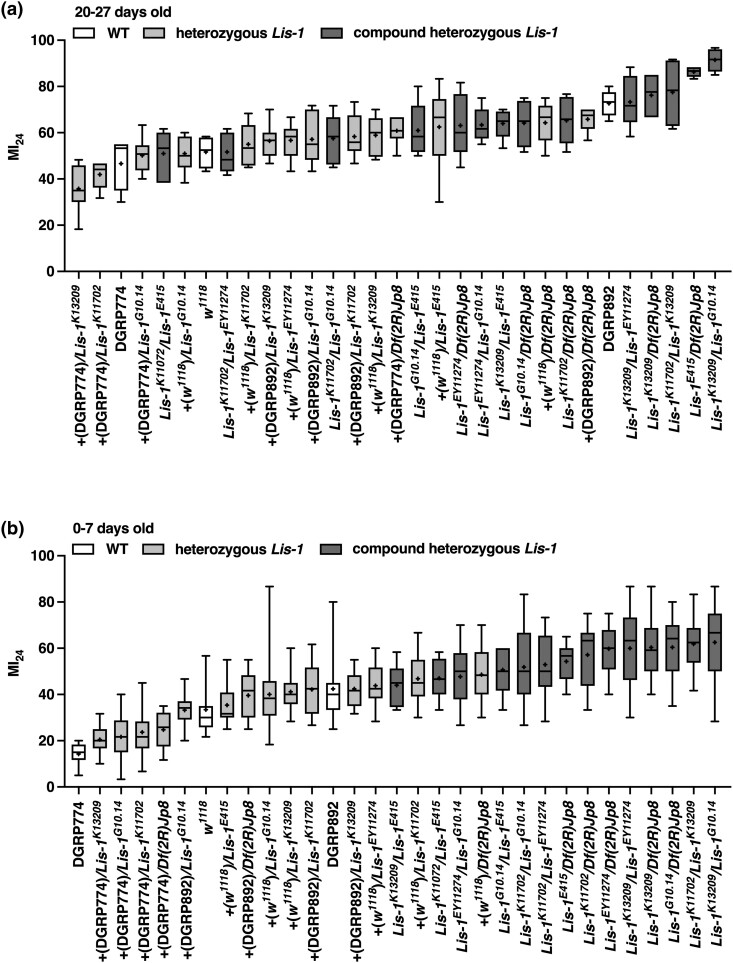

Fig. 3.

Lis-1 mutations increase the MI24 of flies injured at 20–27 or 0–7 days old. The MI24 of mixed-sex Lis-1 mutants of the indicated genotypes injured using the standard TBI protocol at (A) 20–27 days old (n = 6) and (B) 0–7 days old (n = 10). Chromosomes wild type for Lis-1 are designated +(w1118), +(DGRP774), and +(DGRP892), based on their parental origin. Symbols indicate the following: box, second and third quartiles of data; +, mean; horizonal bar, median; and whiskers, minimum and maximum data points. Note that data for DGRP774 and DGRP892 lines are the same in Figs. 4a and b, and data for w1118 flies are the same in Fig. 4a.

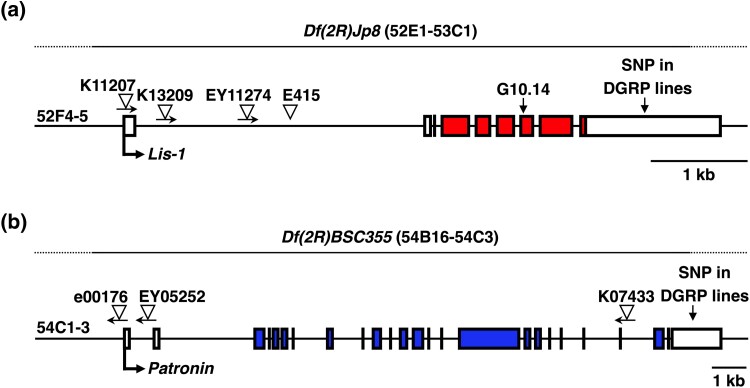

The two most significantly associated SNPs were located in Patronin and Lissencephaly-1 (Lis-1) (Table 1). The C-to-T minor SNP in Patronin was in the 3' untranslated region (UTR) of 12 DGRP lines, and the T-to-C minor SNP in Lis-1 was in the 3' UTR of 11 DGRP lines (Figs. 1 and 2). Lines with the SNP in Patronin had low MI24 values, and lines with the SNP in Lis-1 had high MI24 values, suggesting that Patronin and Lis-1 variants have opposite effects on the MI24.

Fig. 2.

Maps of patronin and lis-1 alleles. Schematic diagrams of (A) Patronin and B) Lis-1 alleles (http://flybase.org). Colored and white boxes indicate coding and non-coding exons, respectively, and intervening lines indicate introns. Locations and orientations of transposons are indicated by triangles and arrows, respectively. The orientation of Lis-1E415 is not known (Swan et al. 1999), Lis-1G10.14 contains a nonsense mutation (R239stop) (see references in Kudumala et al. 2017), and deficiencies Df(2R)BSC355 and Df(2R)Jp8, respectively, delete Patronin and Lis-1 (http://flybase.org). Transcription start sites are indicated by horizontal arrows followed by the gene name. Supplementary Table 2 provides genotypes of Patronin and Lis-1 mutant lines.

Both Patronin and Lis-1 perform non-centrosomal, microtubule-related functions in neurons. Patronin encodes a microtubule minus-end binding protein that stabilizes minus ends by antagonizing Klp10A (Kinesin-like protein at 10A), a kinesin-13 family member involved in depolymerization of microtubules at minus ends (Goodwin and Vale 2010; Akhmanova and Steinmetz 2019). Reduction of Patronin leads to fewer minus-ends-out microtubules in dendrites and altered microtubule polarity (Feng et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2019). It is not known whether microtubule polarity plays a role in mammalian TBI. Lis-1 encodes a protein that binds dynein, a minus-end-directed microtubule motor, and enhances its force production, velocity, and microtubule affinity (Olenick and Holzbaur 2019; Markus et al. 2020). Lis-1 haploinsufficiency in humans causes lissencephaly, a severe developmental disease of the brain characterized by defects in migration of neuronal nuclei that lead to loss of convolutions in the cerebral cortex (Moon and Wynshaw-Boris 2013). Lis-1 is also required for nuclear migration in Drosophila (Lei and Warrior 2000). A mechanistic relationship between Patronin and Lis-1 is yet to be described, but loss of a human ortholog of Drosophila Patronin, Camsap1 (calmodulin-regulated spectrin-associated protein 1), is associated with a neuronal migration disorder similar to Lis-1-related lissencephaly (Khalaf-Nazzal et al. 2022), and phenotypes of Camsap1-/- knockout mice are indicative of impaired neuronal migration (Zhou et al. 2020).

Other genes identified by GWAS also have functions related to microtubules, including Nuclear pore localization 4 (Npl4), which is implicated in controlling microtubule organization in developing motor neurons (Byrne et al. 2017); CG15765, which was originally identified as a suppressor of an eye phenotype caused by aberrant glial cell positioning similar to that caused by mutations of Dynein light chain 90F (Dlc90F) and KP78b that encodes a putative tau kinase (Neuert et al. 2017); and Apoptosis-stimulating protein of p53 (ASPP), whose mammalian orthologs ASPP1 and ASPP2 are implicated in regulating neuronal loss after axonal injury (Langton et al. 2007; Wilson et al. 2014) (Table 1). Among the 14 genes identified by GWAS, we focused on Patronin and Lis-1 because statistical analysis indicated that association of SNPs in these genes with the MI24 was least likely to have occurred by chance and because of their well-documented connection to microtubules, which play a crucial role in TBI outcomes in mammals.

Lis-1 mutations increase early mortality following TBI

To investigate a cause–effect relationship between Lis-1 and early mortality following TBI, we determined the effect of Lis-1 mutations on the MI24 of flies injured at 20–27 days old and 0–7 days old. We examined four transposon insertion alleles of Lis-1 (Lis-1K11207, Lis-1K13209, Lis-1EY11274, and Lis-1E415), a nonsense allele of Lis-1 (Lis-1G10.14), and a deletion that spanned Lis-1 and 26 other genes (Df(2R)Jp8) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 2). Lis-1 mutants were crossed to a standard laboratory line w1118 and DGRP lines DGRP774 and DGRP892 to generate Lis-1 heterozygotes (Lis-1x/+) and to each other to generate Lis-1 compound heterozygotes (Lis-1x/Lis-1y). Lis-1x/Df(2R)Jp8 flies are hemizygous for Lis-1 but were grouped in the analyses with compound heterozygotes. DGRP774 was used because it had a relatively low MI24 when injured at 20–27 days old (46.66 ± 5.02) and 0–7 days old (14.24 ± 1.42), and DGRP892 was used because it had a relatively high MI24 when injured at 20–27 days old (72.66 ± 2.51) and 0–7 days old (42.42 ± 4.31) (Figs. 1a and b and Supplementary Table 1) (Katzenberger et al. 2015a). The goal of examining multiple Lis-1 alleles in different backgrounds was to distinguish between effects of Lis-1 mutations vs genetic background on the MI24.

For flies injured at 20–27 days old, the mean MI24 of 14 Lis-1x/Lis-1y compound heterozygotes (67.56 ± 3.21) was higher than that of 14 Lis-1x/+ heterozygotes (55.34 ± 2.24) (P = 0.004, unpaired two-tailed t-test) (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 3a). Similarly, for flies injured at 0–7 days old, the mean MI24 of Lis-1x/Lis-1y compound heterozygotes (55.04 ± 1.64) was higher than that of Lis-1x/+ heterozygotes (35.98 ± 2.57) (P < 0.0001, unpaired two-tailed t-test) (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 3a). Thus, loss of Lis-1 due to different mutant alleles, even in different genetic backgrounds, enhances early mortality following injury in 20–27 and 0–7 days old flies, demonstrating that this phenotype is associated with Lis-1 itself rather than some other unidentified genes in the genetic background. Furthermore, the fact that Lis-1 mutants enhanced early mortality following injury at 20–27 and 0–7 days old but the minor SNP in Lis-1 was only associated with early mortality following injury at 20–27 days old suggests that following injury at 0–7 days old, effects on early mortality of minor SNPs in other genes overshadow effects of the minor SNP in Lis-1.

Patronin mutations do not alter early mortality following TBI

We performed analyses of Patronin mutants analogous to those of Lis-1 mutants by testing three transposon insertion alleles of Patronin (Patronine00176, PatroninEY05352, and PatroninK07433) and one deletion that spans Patronin and 14 neighboring genes (Df(2R)BSC355) (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 2). For flies injured at 20–27 days old, the mean MI24 of three Patroninx/Patroniny compound heterozygotes (51.93 ± 1.10) was not different from that of eight Patroninx/+ heterozygotes (53.35 ± 1.79) (P = 0.66, unpaired two-tailed t-test) (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 3b). Similarly, for flies injured at 0–7 days old, the mean MI24 of Patroninx/Patroniny compound heterozygotes (36.29 ± 2.53) was not different from that of Patroninx/+ heterozygotes (34.13 ± 2.88) (P = 0.68, unpaired two-tailed t-test) (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 3b). These data indicate that loss of Patronin does not affect early mortality following TBI.

Fig. 4.

Patronin mutations do not affect the MI24 of flies injured at 20–27 or 0–7 days old. The MI24 of mixed-sex Patronin mutants of the indicated genotypes injured using the standard TBI protocol at (A) 20–27 days old (n = 6) and (B) 0–7 days old (n = 10). Chromosomes wild type for Patronin are designated +(w1118), +(DGRP774), and +(DGRP892), based on their parental origin. Symbols indicate the following: box, second and third quartiles of data; +, mean; horizonal bar, median; and whiskers, minimum and maximum data points. Note that data for DGRP774 and DGRP892 lines are the same in Figs. 3a and b, and data for w1118 flies are the same in Fig. 3a.

Overexpression of Lis-1 protein does not alter early mortality following TBI

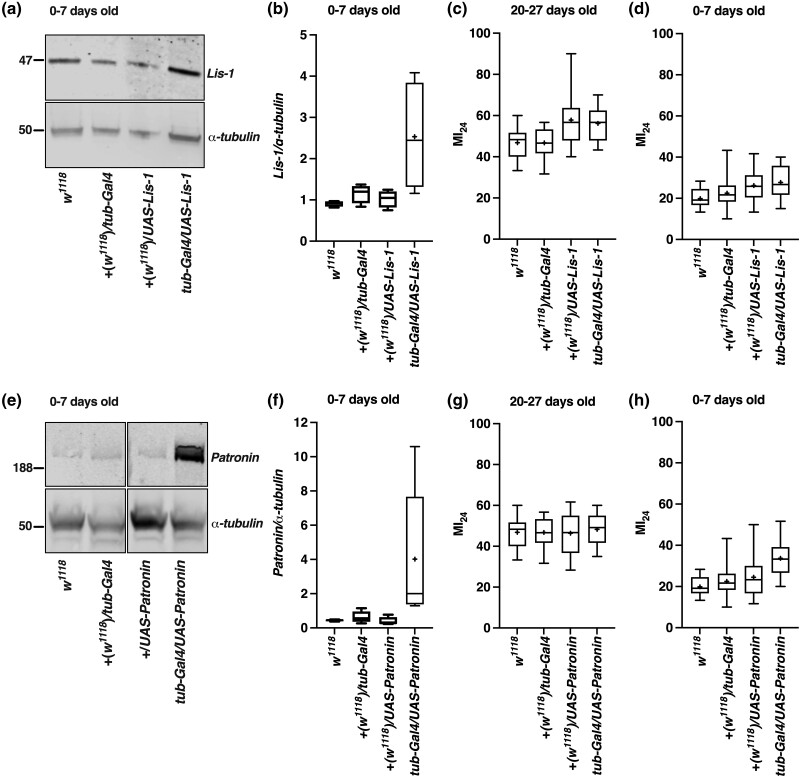

To investigate the effect of increased expression of Lis-1 on early mortality following TBI, we used a tubulin-Gal4 (tub-Gal4) driver transgene to ubiquitously express Lis-1 from a UAS-Lis-1 target transgene (Brand and Perrimon 1993). Western blot analysis of head extracts from 0 to 7 day old male flies showed that flies carrying both driver and target transgenes had higher Lis-1 protein level than flies carrying one transgene (P = 0.017, ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test) (Figs. 5a and b). However, flies carrying both driver and target transgenes did not have an altered MI24 relative to flies carrying only the UAS-Lis-1 transgene at either 20–27 or 0–7 days old (P = 0.69 and P = 0.52, respectively, unpaired two-tailed t-test) (Figs. 5c and d). Thus, ubiquitous overexpression of Lis-1 is not sufficient to alter early mortality following TBI.

Fig. 5.

Overexpression of Patronin increases the MI24 of flies injured at 0–7 day old. a) A representative Western blot and (b) quantitation of Western blots for Lis-1 and α-tubulin protein expression in head extracts of 0–7 day old male flies of the indicated genotypes (n = 4). e) A representative Western blot and (f) quantitation of Western blots for Patronin and α-tubulin protein expression in head extracts of 0–7 day old male flies of the indicated genotypes (n = 4). In panels A and E, protein size markers are indicated on the left in kDa. (c, d, g, and h) The Mi24 of mixed-sex flies of the indicated genotypes injured using the standard TBI protocol at the indicated age (n = 12). Symbols indicate the following: box, second and third quartiles of data; +, mean; horizonal bar, median; and whiskers, minimum and maximum data points.

Overexpression of Patronin protein increases early mortality following TBI in younger but not older flies

We used the same approach as that described for Lis-1 in Figs. 5a-d to determine whether overexpression of Patronin affects early mortality. Quantitation of Western blots showed that flies carrying both the tubulin-Gal4 and UAS-GFP-Patronin transgenes overexpressed Patronin protein relative to flies carrying only one of the transgenes (P = 0.027, ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test) (Figs. 5e and f). Furthermore, flies carrying both transgenes had a higher MI24 than flies carrying only the UAS-GFP-Patronin transgene when injured at 0–7 but not 20–27 days old (P = 0.001 and P = 0.53, respectively, unpaired two-tailed t-test) (Figs. 5g and h). Therefore, overexpression of Patronin is sufficient to increase early mortality following injury of younger flies but not older flies.

nudE mutations do not alter early mortality following TBI

NudE is another microtubule-associated protein that binds directly to Lis-1 and dynein, and like Lis-1, enhances the force production of dynein (McKenney et al. 2010; Reddy et al. 2016). Therefore, it was of interest to determine whether nudE mutations affect the MI24 in a similar manner as Lis-1 mutations or if the beneficial effect in response to TBI is somehow more specific for Lis-1. We tested three transposon insertion alleles of nudE (nudEG14350, nudEd10518, and nudECR00595-TG4.0) (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 2). For flies injured at 20–27 days old, the mean MI24 of three nudEx/nudEy compound heterozygotes (57.83 ± 5.59) was not different from that of nine nudEx/+ heterozygotes (53.87 ± 2.23) (P = 0.45, unpaired two-tailed t-test) (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 3c). Similarly, for flies injured at 0–7 days old, the mean MI24 of nudEx/nudEy compound heterozygotes (29.09 ± 2.33) was not different from that of nudEx/+ heterozygotes (27.95 ± 2.23) (P = 0.79, unpaired two-tailed t-test) (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 3c). Thus, loss of nudE does not affect early mortality following TBI, suggesting that Lis-1 functions independently of NudE in a process that confers some protective effect against early mortality following TBI.

Lis-1 mutations do not affect lifespan following TBI

The pathophysiology of TBI is complex with both short-term and long-term effects on viability, behavior, neuronal integrity, and lifespan. Some genes may affect underlying mechanisms that mediate multiple sequalae, while other genes only affect specific TBI outcomes. We have found that variants of Lis-1 affect both survival within 24 h after injury and neuronal viability several weeks later (Fig. 9), suggesting that Lis-1 is involved in several different consequences of TBI. Ultimately, TBI is generally associated with a reduced lifespan. To determine whether Lis-1 function normally helps to extend lifespan following TBI, we examined the lifespan of Lis-1 variants that survived 24 h following TBI. We found that for all Lis-1x/Lis-1y compound heterozygotes and Lis-1x/+ heterozygotes, injured flies had a shorter lifespan than uninjured flies, consistent with our prior finding that TBI reduces lifespan (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 6 and Table 2) (Katzenberger et al. 2013, 2016; Swanson et al. 2020; Swanson et al. 2020). However, average median lifespans were the same for uninjured Lis-1x/Lis-1y compound heterozygotes (55.34 ± 2.94 days) and Lis-1x/+ heterozygotes (56.13 ± 4.39 days) (P = 0.87, unpaired two-tailed t-test) and for injured Lis-1x/Lis-1y compound heterozygotes (42.55 ± 2.94 days) and Lis-1x/+ heterozygotes (45.53 ± 3.0 days) (P = 0.5, unpaired two-tailed t-test). Similar lifespans of Lis-1 compound heterozygotes and heterozygotes when uninjured or injured indicate that, whereas Lis-1 function is beneficial for immediate survival following TBI, it does not confer similar benefit to improve lifespan, suggesting the operation of distinct mechanisms.

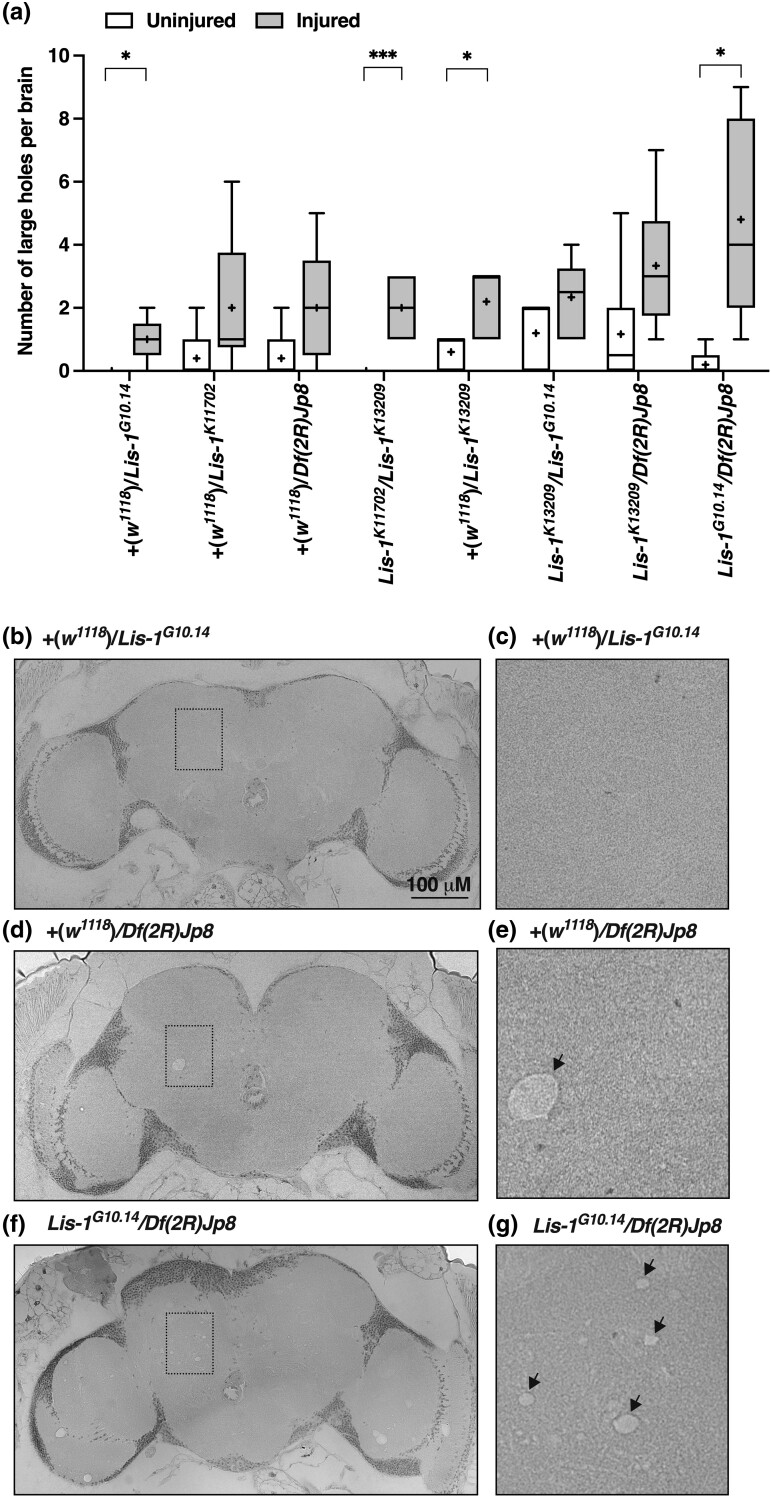

Fig. 9.

Lis-1 mutations enhance neurodegeneration in the brain following TBI. a) The number of large (>5 μM) holes in the brain of female Lis-1 mutants of the indicated genotypes at two weeks after injury at 0–7 days old (injured) or at the same age in the absence of injury (uninjured) (n = 4). Lis-1 heterozygotes were generated by crossing Lis-1 mutants to the w1118 line. Brain sections chosen for analysis were at equivalent depths in the brain. Genotypes are ordered from low to high, based on the mean number of holes per brain in injured flies. Symbols indicate the following: box, second and third quartiles of data; +, mean; horizonal bar, median; and whiskers, minimum and maximum data points. (b–d) Representative images of sections of fly brains from flies of the indicated genotypes and injury status. (e–g) High-magnification images of boxed regions in b–d, respectively. Arrows indicate large holes.

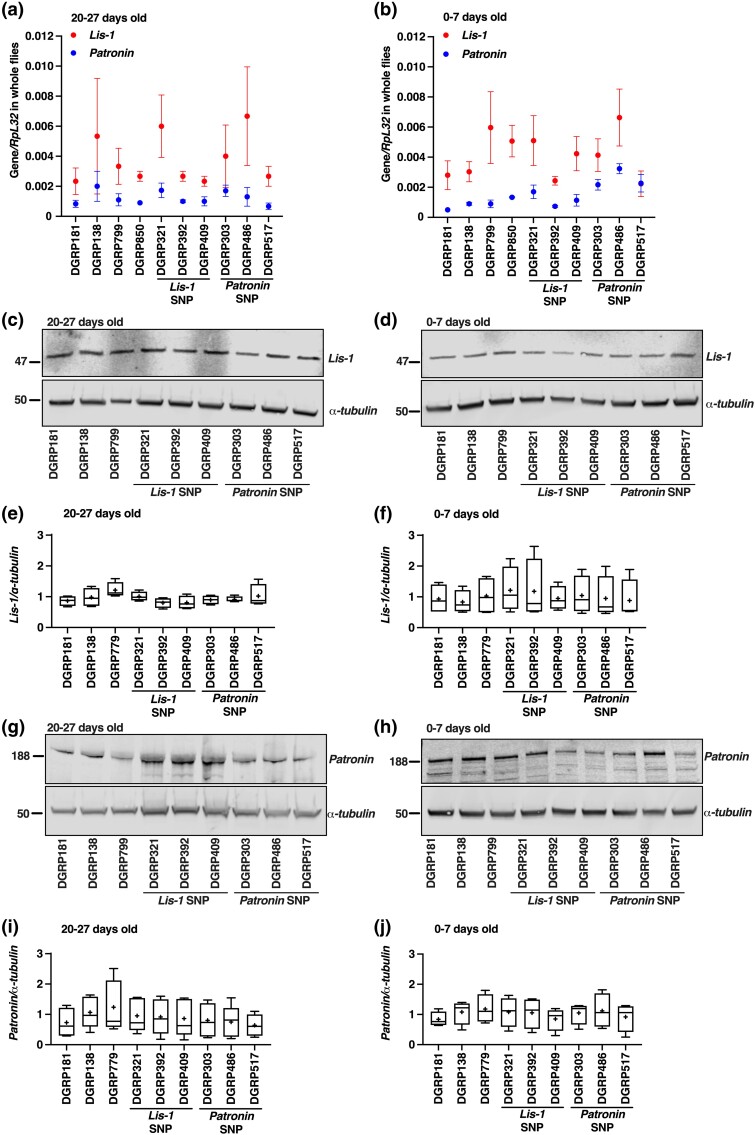

Expression of Lis-1 is not altered by the minor TBI-associated SNP

The minor SNP in Lis-1 associated with a reduced MI24 following injury of 20–27 days old flies is located in the 3' UTR (Fig. 1a). 3' UTRs are known to contain binding sites for proteins and RNAs that alter gene expression by regulating mRNA decay and translation (Yamashita and Takeuchi 2017; Mayya and Duchaine 2019). Thus, we examined whether reduced expression of Lis-1 prior to injury might underlie the association of the minor SNP with the effect on MI24 (Fig. 1a) by quantifying steady-state levels of Lis-1 mRNA and protein in DGRP lines at 20–27 days old. We also examined the lines at 0–7 days old because Lis-1 mutants affected the MI24 following injury at this age (Fig. 3b). We assayed mRNA expression in whole male flies by qRT-PCR. Three analyzed DGRP lines had the minor SNP in Lis-1 and seven had the major SNP in Lis-1. At 20–27 and 0–7 days old, the amount of Lis-1 mRNA did not differ between lines with the minor vs major SNP in Lis-1 (P = 0.94 and P = 0.71, respectively, unpaired two-tailed t-test) (Figs. 7a and b). Similarly, investigation of protein expression by Western blot analysis of extracts from male heads at both ages showed no difference in the amount of Lis-1 between lines with the minor vs major SNP in Lis-1 (20–27 days old: P = 0.26 and 0–7 days old: P = 0.06, unpaired two-tailed t-test) (Figs. 7c-f). These data indicate that the minor SNP either does not affect Lis-1 expression in the absence of injury or it affects expression in a subset of cells that cannot be detected in analyses of whole flies or fly heads.

Fig. 7.

Effects of minor SNPs identified by GWAS on expression of Lis-1 and Patronin mRNAs and proteins in uninjured flies. qRT-PCR analysis of Lis-1 and Patronin mRNAs relative to Rpl32 mRNA in uninjured, whole, male DGRP lines at (a) 20–27 days old and (d) 0–7 days old (n = 3). Dots and whiskers indicate the average and SEM, respectively (n = 3). (c and d) Representative Western blots and (e and f) quantitation of Western blots (n = 3) for Lis-1 and α-tubulin protein expression in head extracts from (c and e) 20–27 day old and (d and f) 0–7 day old male flies of the indicated DGRP line. (g and h) Representative Western blots and (i and j) quantitation of Western blots (n = 3) for Patronin and α-tubulin protein expression in head extracts from (g and i) 20–27 day old and (H and J) 0–7 day old male flies of the indicated genotypes. (c, d, g, and h) Protein size markers are indicated on the left in kDa. (e, f, i, and j) Symbols indicate the following: box, second and third quartiles of data; +, mean; horizonal bar, median; and whiskers, minimum and maximum data points.

Expression of Patronin mRNA is increased by the minor TBI-associated SNP in younger but not older flies

The minor TBI-associated SNP in Patronin also resides in the 3' UTR, again suggesting that altered expression of Patronin prior to injury might underlie this association (Fig. 1a). Thus, we quantified steady-state levels of Patronin mRNA and protein in DGRP lines at 20–27 and 0–7 days old. We measured mRNA expression in whole male flies by qRT-PCR. Three DGRP lines analyzed had minor SNP in Patronin and seven had major SNP in Patronin. In 20–27 day-old flies, the amount of Patronin mRNA did not differ between lines with the minor vs major SNP in Patronin (P = 0.94, unpaired two-tailed t-test) (Fig. 7a). However, lines with the minor SNP had higher expression in 0–7 day-old flies (P < 0.0001, unpaired two-tailed t-test) (Fig. 7b). Nevertheless, analysis of protein expression by Western blots of extracts from male heads showed no difference in the amount of Patronin between lines with minor vs major SNPs in Patronin at 20–27 or 0–7 days old (20–27 days old: P = 0.07 and 0–7 days old: P = 0.89, unpaired two-tailed t-test) (Figs. 7g-i). Thus, although these data indicate that the minor SNP in Patronin can increase mRNA expression, the age selectivity of this expression difference and the lack of an apparent increase in protein expression at this point preclude the increase in mRNA expression as an explanation for association of the minor SNP in Patronin with a low MI24 following injury at 20–27 days old.

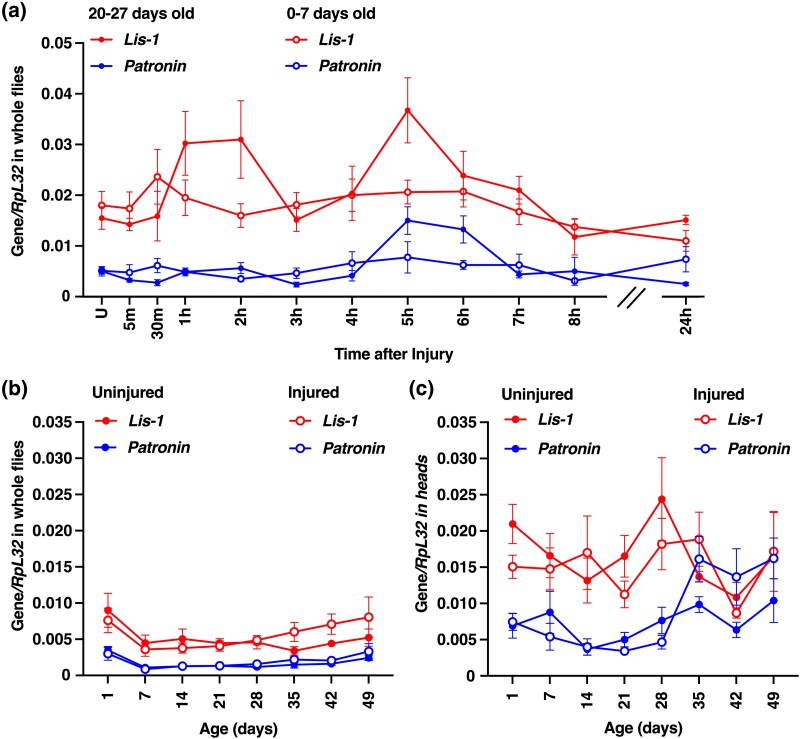

Expression of Lis-1 and Patronin mRNAs is largely unaffected by TBI

Expression of numerous genes is positively or negatively regulated in response to TBI (Cho et al. 2016; Katzenberger et al. 2016; Hazy et al. 2019). Consequently, altered expression of Lis-1 and Patronin could be a usual consequence of TBI and modification of these expression patterns owing to 3' UTR SNPs could be a factor in their association with differential TBI outcomes. Consistent with this possibility, our previous RNA-seq analyses of whole w1118 male flies injured at 20–27 days old revealed increased Lis-1 mRNA levels at 4 h after TBI, although the increase was small, <1.5-fold (Katzenberger et al. 2016). Moreover, in humans, expression of Lis-1 is lower in CTE Stage IV compared with Stage III (Mufson et al. 2018), and it is developmentally downregulated in mature dorsal root ganglion neurons, resulting in decreased axonal extension capacity (Kumamoto et al. 2017).

We used qRT-PCR to examine mRNA levels over 24 h after TBI and at one-week intervals thereafter to determine the effect of TBI on expression levels of Lis-1 and Patronin. Analysis of whole, w1118, male flies at 0–8 and 24 h following an injury at 20–27 days old revealed an increase in Lis-1 expression that was limited to the 5 h time point (P = 0.02, ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test) but no change in Lis-1 expression following injury at 0–7 days old (P = 0.26, ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test) (Fig. 8a). Similarly, expression of Patronin in flies injured at 20–27 days old increased at 5 and 6 h time points (P = 0.001, ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test) but did not change following an injury at 0–7 days old (P = 0.67, ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test). As a positive control to show that changes in mRNA level induced by TBI can be detected throughout the time course, we previously found using the same samples that expression of antimicrobial peptide genes such as Attacin C was higher at 30 to 8 h and at 24 h following TBI (Katzenberger et al. 2016). We also found that injury did not affect Lis-1 and Patronin mRNA levels in whole flies (Fig. 8b) or fly heads (Fig. 8c) over seven weeks following an injury at 0–7 days old (0.96 > P > 0.1 for all pairwise comparisons of injured vs uninjured flies, unpaired two-tailed t-test). Thus, mechanisms underlying the roles of Lis-1 and Patronin in response to TBI do not appear to involve widespread alteration of their expression.

Fig. 8.

TBI does not markedly alter expression of Lis-1 and Patronin mRNAs in w1118 flies. qRT-PCR analysis of the amount of Lis-1 and Patronin mRNAs relative to Rpl32 mRNA in uninjured (U) flies at time zero and at indicated time points after injury using the standard TBI protocol. a) Male w1118 flies were injured at 20–27 or 0–7 days old and mRNA level was determined in whole flies at the indicated time points over 24 h following injury (n = 8). mRNA level in (b) whole, male w1118 flies and (c) heads of male w1118 flies was determined for flies every 7 days over 49 days following injury or no injury (uninjured) at 0–7 days old (n = 6). Each data point represents the mean and SEM.

Lis-1 mutations enhance neurodegeneration following TBI

Neurodegeneration in flies is commonly characterized by holes in the optic lobes and the central brain neuropil, a region enriched for axons, synaptic terminals, and glial cells (McGurk et al. 2015). In the fly TBI model, the incidence of large holes (>5 μm in diameter) in the central brain of w1118 flies at two weeks post-injury increases with the number of strikes from the HIT device (Katzenberger et al. 2013). Here, we found that at two weeks after injury of 0–7 day old female flies, the average number of large holes per brain was greater for Lis-1x/Lis-1y compound heterozygotes (3.02 ± 0.44 holes) than for Lis-1x/+ heterozygotes (1.81 ± 0.34 holes) (n = 6, P = 0.04, unpaired two-tailed t-test) (Fig. 9a). In contrast, for uninjured flies of the same age, the average number of large holes per brain did not differ between Lis-1x/Lis-1y compound heterozygotes (0.35 ± 0.15 holes) and Lis-1x/+ heterozygotes (0.67 ± 0.27 holes) (n = 6, P = 0.32, unpaired two-tailed t-test). Figures 9b-g show representative images of brain sections from injured Lis-1 mutant flies. Thus, neurodegeneration following TBI is more severe in flies with mutant Lis-1.

Discussion

Variants of many genes are likely to affect TBI outcomes

Identifying factors that contribute to individual variation in TBI outcomes will help with clinical diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment decisions (Cruz Navarro et al. 2022; Reddi et al. 2022). Many factors, including genotype, age, and diet, can alter acute and chronic outcomes resulting from a given primary injury (Weber et al. 2019; Kochanek et al. 2020; Cortes and Pera 2021; Smith et al. 2021). This may explain why potential therapies developed using mammalian TBI models under defined conditions of genotype, age, and diet have not proven beneficial under heterogeneous conditions associated with TBI in humans (Maas et al. 2010; Kabadi and Faden 2014; Stein 2015; Ganetzky and Wassarman 2016).

Here, we provide evidence that genetic variation causes substantial variability in TBI outcomes in flies. Early mortality of fly lines that received equivalent primary injuries ranged from 7 to 97% because of differences in genotype and age at the time of injury (Figs. 1a and b). Thus, one way that genetic variation influences TBI outcomes appears to be through effects on aging-related processes. In support of this hypothesis, early mortality following injury at a given chronological age is negatively correlated with median lifespan among genetically diverse fly lines—lines that live longer have a lower MI24. (Katzenberger et al. 2013). Because of the evolutionary conservation of genes and mechanistic pathways, genetic variation and its effects on aging are likely to be main factors underlying the heterogeneity of TBI outcomes in humans.

Our studies identified polymorphisms in 14 genes that may contribute to variability in the early mortality of fly lines injured at 20–27 days old, several of which encode proteins with microtubule-related functions (Table 1). These genes add to the 98 genes previously identified by GWAS of fly lines injured at 0–7 days old (Katzenberger et al. 2015a). A considerable amount of work remains to test whether polymorphisms in these genes are causative for early mortality and other TBI outcomes. To begin this work, we characterized effects of Lis-1 and Patronin mutation and overexpression on early mortality. Based on the assumption that SNPs associated with early mortality reduce gene activity, we hypothesized that Lis-1 and Patronin loss-of-function mutants would have exceptionally high and low early mortality, respectively, and that flies overexpressing these genes would show the opposite effects on early mortality. In support of this hypothesis, early mortality was significantly elevated following injury of Lis-1 mutants at 20–27 or 0–7 days old (Fig. 3), and overexpression of Patronin increased early mortality following injury at 0–7 days old (Fig. 5). These data suggest that Lis-1 promotes and Patronin inhibits survival within 24 h following TBI.

However, the hypothesis was not fully supported since overexpression of Lis-1 and mutation of Patronin had no effect on early mortality (Figs. 4 and 5). Furthermore, our studies did not resolve why minor SNPs in the 3' UTR of Lis-1 and Patronin were associated with a high and low risk of early mortality, respectively, following injury at 20–27 days old (Fig. 1a). We were unable to detect a minor SNP-dependent change in Lis-1 expression (Figs. 7a-f) or a prolonged change in expression following TBI in w1118 flies (Fig. 8). Similarly, the minor SNP in Patronin did not affect Patronin mRNA or protein expression in 20–27 day old flies (Figs. 7a, g, and i), and TBI did not cause a sustained change in Patronin mRNA level (Fig. 8). Yet, the minor SNP was associated with increased Patronin mRNA but not protein expression in 0–7 day-old flies (Figs. 7b, h, and j). Nonetheless, these data do not rule out the possibility that the SNPs affect Lis-1 and Patronin expression. The SNPs may alter mRNA expression in particular cells of the brain or tissues other than the brain or protein expression following TBI. Thus, additional studies are needed to fully understand the regulation of Lis-1 and Patronin expression in the context of TBI.

We also found that neurodegeneration was significantly elevated at two weeks after injury of 0–7 day old Lis-1 mutants (Fig. 9), revealing that Lis-1 activity also serves to limit neurodegeneration that occurs over time following TBI. However, Lis-1 activity did not affect lifespan of injured or uninjured flies (Fig. 6 and Supplementary 6 and Table 2), suggesting that mechanisms by which Lis-1 affects early mortality and neurodegeneration are independent of mechanisms that promote age-dependent survival. This is in contrast with effects of the innate immune response on early mortality, which appear to act through mechanisms that promote aging (Swanson et al. 2020; Swanson et al. 2020). These studies demonstrate that GWAS in flies offers a pragmatic approach to identify specific genes whose naturally occurring variation could contribute to the diversity of short-term and long-term outcomes following TBI in humans.

How might Lis-1 affect TBI outcomes?

We hypothesize that Lis-1 affects TBI outcomes through its documented effects on microtubule stability and/or dynein-mediated retrograde transport of cargo from microtubule minus ends. Lis-1 can increase or decrease microtubule stability depending on the context and cell type, so either outcome is possible following TBI (Sapir et al. 1997; Han et al. 2001; Coquelle et al. 2002; Kawano et al. 2022). Alternatively, Lis-1 may facilitate the transport of specific factors that are beneficial to neurons following TBI, such as L1-type cell adhesion molecules (L1CAMs) that play a role in central nervous system regeneration after injury (Becker et al. 2004, 2005; Chen et al. 2007; Maness and Schachner 2007). In Drosophila, Lis-1 functions in retrograde trafficking of L1CAM, since Lis-1 mutations lead to the accumulation of the sole L1CAM homolog Neuroglian (Nrg) in vesicular clusters in synaptic terminals of giant fiber neurons (Kudumala et al. 2017). A complex of Lis-1 with NudE1/NudE-like 1 (NudEL1) enhances the force produced by dynein, allowing dynein to adjust to the cargo load (McKenney et al. 2010; Reddy et al. 2016). However, Lis-1 appears to function independently of NudE in our TBI model (Supplementary Fig. 5), as it does in other contexts (Simões et al. 2018). Lis-1 may also function along with dynein in retrograde transport as part of the evolutionarily conserved response to axonal injury that triggers Wallerian degeneration of axons distal to injuries (Coleman and Freeman 2010; Conforti et al. 2014). Consistent with this possibility, Hill et al. (2020) found that TBI outcomes in flies, including loss of dopaminergic neurons, are improved by inhibition of a Wallerian degeneration signaling pathway. Finally, Lis-1 may indirectly mitigate TBI outcomes by counteracting the toxic effects of tau. In support of this proposal, tau hyperphosphorylation inhibits axonal transport of cargos to and from synapses (Alonso et al. 2018; Barbier et al. 2019; Combs et al. 2019), and tau toxicity is enhanced when retrograde transport is impaired by knockdown of dynactin subunits that function to increase the processivity of dynein (Butzlaff et al. 2015).

In addition to its role in regulating dynein, Lis-1 also has a separate function in regulating signaling by phospholipids. Lis-1 was originally identified as a non-catalytic regulatory subunit of the intracellular 1B isoform of platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase (PAFAH1B1), a heterotrimeric enzyme that catalyzes the removal of short acetyl chains from the sn-2 position of platelet-activating factor (PAF, 1-O-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) (Kono and Arai 2019) (Table 1). The dual role of Lis-1 raises the possibility that it could affect TBI outcomes in a manner unrelated to microtubules. This possibility is supported by the fact that PAF is a signaling phospholipid in the central nervous system involved in diverse events, including inflammation, and knockout of the PAF receptor (PAFR) in mice reduces neuroinflammation and behavioral abnormalities following TBI (Yin et al. 2016). Thus, loss of Lis-1/PAFAH1B1 in flies may increase early mortality and neurodegeneration following TBI by altering the amount of PAF isoforms and resultant PAFR activity. Further studies in flies and mice will be required to resolve which of Lis-1's distinct activities are most relevant in the context of TBI.

Broader implications

It is noteworthy that Lis-1 was identified as a modifier of TBI outcomes in flies, which have a lissencephalic brain. These data indicate that Lis-1 plays a role in TBI that is independent of its role in developmental nuclear and neuronal migration events required for the formation of gyri and sulci in the cerebral cortex (Wynshaw-Boris 2007). This finding adds to the ongoing discussion in the TBI field about the clinical value of pre-clinical TBI studies in animals such as flies, mice, and rats that have a lissencephalic brain, when the human brain is gyrencephalic (Vinc 2017; DeWitt et al. 2018; Sorby-Adams et al. 2018). Structural differences between lissencephalic and gyrencephalic brains can affect the degree of brain deformation that results from a mechanical impact. Modeling indicates that maximum mechanical stress is experienced near the surface of lissencephalic brains, while it is experienced at the base of sulci in gyrencephalic brains (Cloots et al. 2008; Ho and Kleiven 2009). Additionally, tau pathology in CTE begins at the base of sulci and its progression is associated with reduced expression of Lis-1 (McKee et al. 2015; Mufson et al. 2018). Nevertheless, our data indicate that with regard to TBI, at least some genes involved in forming a gyrencephalic brain can be studied in animals with a lissencephalic brain.

Parallels between TBI and Alzheimer's disease, including association with the apoE4 variant, formation of aggregates of hyperphosphorylated tau, and increased risk of dementia, raise the possibility that Lis-1 is also involved in Alzheimer's disease (Emrani et al. 2020; Cortes and Pera 2021; Li et al. 2021; Mielke et al. 2022). Further support for this possibility comes from deep learning-based analysis of Alzheimer's disease patients that identified a Bicaudal D1 (BICD1) variant as a strong genetic risk factor for Alzheimer's disease (Jo et al. 2022). BICD is an adaptor protein that regulates dynein-based movement. In vitro, Lis-1 binds the dynein-dynactin-BICD2N complex and enhances its velocity, and in Drosophila, BICD acts with Lis-1 to localize nuclei in the developing nervous system (Swan et al. 1999; Schlager et al. 2014; Gutierrez et al. 2017; Olenick and Holzbaur 2019). Additionally, while Lis-1 has not been directly implicated in Alzheimer's disease pathologies, impaired retrograde transport has been implicated. Dissociation of hyperphosphorylated tau from microtubules inhibits retrograde transport (Butzlaff et al. 2015; Tiernan et al. 2016; Butler et al. 2019; Jiang and Bhaskar 2020). Furthermore, in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease that expresses a mutant form of human amyloid precursor protein and in brains of human Alzheimer's disease patients, impaired retrograde transport leads to the accumulation of amphisomes, organelles formed by fusion of endosomes with autophagosomes, at axonal terminals (Tammineni et al. 2017; Tammineni et al. 2017). Inefficient removal of autophagic cargos from axons and synapses leads to autophagic stress, which is implicated in Alzheimer's disease pathology (Nixon and Yang 2011). Finally, impaired retrograde transport reduces protease delivery to lysosomes and lysosomal proteolytic activity, which is linked to Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis (Lee et al. 2011; Tammineni et al. 2017; Tammineni et al. 2017). Thus, a better understanding of the role Lis-1 plays in TBI pathology may also ultimately yield new mechanistic insights into the pathophysiology of Alzheimer's disease.

In summary, this study provides further evidence that genetic variation and its effects on aging are important determinants of heterogeneity in TBI outcomes, and it adds Lis-1 and possibly Patronin/Camsap1 variants as drivers of different TBI outcomes. In addition, this study highlights that the rational design of therapeutics for TBI in humans can be augmented by experimental systems such as the fly TBI model that can take multiple variables into account.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Grace Boekhoff-Falk and the Wassarman lab for their constructive input throughout the course of this work, Stanislava Chtarbanova for suggesting the Wolbachia experiment, Wen Huang for assistance with the DGRP webserver, Dirk Beuchle for providing Lis-1E415 mutant flies, Carole Seum for providing UAS-GFP-Patronin flies and a Patronin antibody, and Satoshi Kinoshita for sectioning fly heads. We also thank the editor and reviewers for their thoughtful critiques of the manuscript and suggestions for how to improve it.

Contributor Information

Rebeccah J Katzenberger, Department of Medical Genetics, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA.

Barry Ganetzky, Department of Genetics, College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA.

David A Wassarman, Department of Medical Genetics, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA.

Data availability

All data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in this article are available in the article and the Supplemental materials. Fly stocks and reagents are available upon request. Supplemental material available at GENETICS online.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R21NS091893 and RF1NS114359. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions

R.J.K, B.G., and D.A.W. designed the project. R.J.K. and D.A.W. performed and analyzed the experiments. R.J.K., B.G., and D.A.W. wrote the manuscript.

Literature cited

- Akhmanova A, Steinmetz MO. Microtubule minus-end regulation at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2019;132(11):jcs227850. doi: 10.1242/jcs.227850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Nimer F, et al. Strain influences on inflammatory pathway activation, cell infiltration and complement cascade after traumatic brain injury in the rat. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;27(1):109–122. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso AD, Cohen LS, Carbo C, Morozova V, Elldrissi A, Phillips G, Kleiman FE. Hyperphosphorylation of tau associates with changes in its function beyond microtubule stability. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:338. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier P, et al. Role of tau as a microtubule-associated protein: structural and functional aspects. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:204. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barekat A, Gonzalez A, Mauntz RE, Kotzebue RW, Molina B, El-Mecharrafie N, Conner CJ, Garza S, Melkani GC, Joiner WJ, et al. Using Drosophila as an integrated model to study mild repetitive traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):25252. doi: 10.1038/srep25252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker T, Lieberoth BC, Becker CG, Schachner M. Differences in the regeneration response of neuronal cell populations and indications for plasticity in intraspinal neurons after spinal cord transection in adult zebrafish. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;30(2):265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker CG, Lieberoth BC, Morellini F, Feldner J, Becker T, Schachner M. L1.1 is involved in spinal cord regeneration in adult zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2004;24(36):7837–7842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2420-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke JA, Ye C, Setty A, Moberg KH, Zheng JQ. Repetitive mild head trauma induces activity mediated lifelong brain deficits in a novel Drosophila model. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):9738. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89121-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blommer J, Fischer MC, Olszewski AR, Katzenberger RJ, Ganetzky B, Wassarman DA. Ketogenic diet reduces early mortality following traumatic brain injury in Drosophila via the PPARγ ortholog Eip75B. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of alternating cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118(2):401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhlman LM, Krishna G, Jones TB, Thomas TC. Drosophila as a model to explore secondary injury cascades after traumatic brain injury. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;142:112079. doi:. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler VL, Salazar DA, Soriano-Castell D, Alves-Ferreira M, Dennissen FJA, Vohra M, Oses-Prieto JA, Li KH, Wang AL, Jing B, et al. Tau/MAPT disease associated variant A152T alters tau function and toxicity via impaired retrograde axonal transport. Hum Mol Genet. 2019;28(9):1498–1514. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butzlaff M, Hannan SB, Karsten P, Lenz S, Ng J, Voßfeldt H, Prüßing K, Pflanz R, Schulz JB, Rasse T, et al. Impaired retrograde transport by the dynein/dynactin complex contributes to tau-induced toxicity. Hum Med Genet. 2015;24(13):3623–3637. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne DJ, Harmon MJ, Simpson JC, Blackstone C, O'Sullivan NC. Roles for the VCP co-factors Nlp4 and Ufd1 in neuronal function in Drosophila melanogaster. J Genet Genomics. 2017;44(10):493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S, Skolnick B, Narayan RK. Neuroprotection trials in traumatic brain injury. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16(4):29. doi: 10.1007/s11910-016-0625-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Wu J, Apostolova I, Skup M, Irintchev A, Kügler S, Schachner M. Adenoassociated virus-mediated L1 expression promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Brain. 2007;130(4):954–969. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YE, Latour LL, Kim H, Turtzo LC, Olivera A, Livingston WS, Wang D, Martin C, Lai C, Cashion A, et al. Older age results in differential gene expression after mild traumatic brain injury and is linked to imaging differences at acute follow-up. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:168. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloots RJH, Gervaise HMT, van Dommelel JAW, Geers MGD. Biomechanics of traumatic brain injury: influences of the morphological heterogeneities of the cerebral cortex. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36(7):1203–1215. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9510-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JH, Leech R, Sharp DJ, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Prediction of brain age suggests accelerated atrophy after traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2015;77(4):571–581. doi: 10.1002/ana.24367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman MP, Freeman MR. Wallerian degeneration, wld(s), and nmat. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2010;33(1):245–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs B, Mueller RL, Morfini G, Brady ST, Kanaan NM. Tau and axonal misregulation in tauopathies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1184:81–95. doi: 10.1007/978-981-32-9358-8_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conforti L, Gilley J, Coleman MP. Wallerian degeneration: an emerging axon death pathway linking injury and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(6):394–409. doi: 10.1038/nrn3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coquelle FM, Caspi M, Cordelières FP, Dompierre JP, Dujardin DL, Koifman C, Martin P, Hoogenraad CC, Akhmanova A, Galjart N, et al. LIS1, CLIP-170's key to the dynein/dynactin pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(9):3089–3102. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.9.3089-3102.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes D, Pera MF. The genetic basis of inter-individual variation in recovery from traumatic brain injury. npj Regen Med. 2021;6(1):5. doi: 10.1038/s41536-020-00114-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker KL, Marischuk K, Rimkus SA, Zhou H, Yin JCP, Boekhoff-Falk G. Neurogenesis in the adult Drosophila brain. Genetics. 2021;219(2):ijab092. doi: 10.1093/genetics/iyab092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross DJ, Garwin GG, Cline MM, Richards TL, Yarnykh V, Mourad PD, Ho RJY, Minoshima S.. Paclitaxel improves outcome from traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2015;1618:299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross DJ, Meabon JS, Cline MM, Richards TL, Stump AJ, Cross CG, Minoshima S, Banks WA, Cook DG. Paclitaxel reduces brain injury from repeated head trauma in mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;67(3):859–874. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz Navarro J, Ponce Mejia LL, Robertson C. A precision medicine agenda in traumatic brain injury. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:713100. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.713100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derivery E, Seum C, Daeden A, Loubéry S, Holtzer L, Jülicher F, Gonzalez-Gaitan M. Polarized endosome dynamics by spindle asymmetry during asymmetric cell division. Nature. 2015;528(7581):280–285. doi: 10.1038/nature16443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewan MC, Rattani A, Gupta S, Baticulon RE, Hung Y-C, Punchak M, Agrawal A, Adeleye AO, Shrime MG, Rubiano AM, et al. Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2018:1–18. doi: 10.3171/2017.10.JNS17352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt DS, Hawkins BE, Dixon CE, Kochanek PM, Armstead W, et al. Pre-clinical testing of therapies for traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(23):2737–2754. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.5778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhandapani SS, Manju D, Sharma BS, Mahapatra AK. Prognostic significance of age in traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012;3(02|2):131–135. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.98208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emrani S, Arain HA, DeMarshall C, Nuriel T. APOE4 is associated with cognitive and pathological heterogeneity in patients with Alzheimer's Disease: a systematic review. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1):141. doi: 10.1186/s13195-020-00712-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C, Thyagarajan P, Shorey M, Seebold DY, Weiner AT, Albertson RM, Rao KS, Sagasti A, Goetschius DJ, Rolls MM. Patronin-mediated minus end growth is required for dendritic microtubule polarity. J Cell Biol. 2019;218(7):2309–2328. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201810155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GB, LeVasseur RA, Faden AI. Behavioral responses of C57BL/6, FVB/N, and 129/SvEMS mouse strains to traumatic brain injury: implications for gene targeting approaches to neurotrauma. J Neurotrauma. 1999;16(5):377–389. doi: 10.1089/neu.1999.16.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganetzky B, Wassarman DA. Non-mammalian animal models offer new perspectives on TBI. Curr Phys Med Rehab Rep. 2016;4(1):1–4. doi: 10.1007/s40141-016-0107-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RC, Burke JF, Nettiksimmons J, Kaup A, Barnes DE, Yaffe K. Dementia risk after traumatic brain injury vs nonbrain trauma: the role of age and severity. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(12):1490–1497. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez A, Batson C, Froese L, Zeiller FA. Genetic variation and impact on outcome in traumatic brain injury: an overview of recent discoveries. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2021;21(5):19. doi: 10.1007/s11910-021-01106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin SS, Vale RD. Patronin regulates the microtubule network by protecting microtubule minus ends. Cell. 2010;143(2):263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez PA, Ackermann BE, Vershinin M, McKenney RJ. Differential effects of the dynein-regulatory factor lissencephaly-1 on processive dynein-dynactin motility. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(29):12245–12255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.790048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han G, Liu B, Zhang J, Zuo W, Morris NR, Xiang X. The Aspergillus cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain and NUDF localize to microtubule ends and affect microtubule dynamics. Curr Biol. 2001;11(9):719–724. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawryluk GW, Bullock MR. Past, present, and future of traumatic brain injury research. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2016;27(4):375–396. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazy A, Bochicchio L, Oliver A, Xie E, Geng S, Brickler T, Xie H, Li L, Allen IC, Theus MH. Divergent age-dependent peripheral immune transcriptomic profile following traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):8564. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45089-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CS, Sreedharan J, Loreto A, Menon DK, Colemen MP. Loss of highwire protects against the deleterious effects of traumatic brain injury in Drosophila melanogaster. Front Neurol. 2020;11:401. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho J, Kleiven S. Can sulci protect the brain from traumatic injury? J Biomech. 2009;42(13):2074–2080. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Campbell T, Carbone MA, Jones WE, Unselt D, Anholt RRH, Mackay TFC. Context-dependent genetic architecture of Drosophila life span. PLoS Biol. 2020;18(3):e3000645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Massouras A, Inoue Y, Feiffer J, Ràmia M, Tarone AM, Turlapati L, Zichner T, Zhu D, Lyman RF, et al. Natural variation in genome architecture among 205 Drosophila melanogaster genetic reference panel lines. Genome Res. 2014;24(7):1193–1208. doi: 10.1101/gr.171546.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hukkelhoven CWPM, Steyerber EW, Rampen AJJ, Farace E, Habbema JDF, Marshall LF, Murray GD, Maas AIR. Patient age and outcome following severe traumatic brain injury: an analysis of 5600 patients. J Neurosurg. 2003;99(4):666–673. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.4.0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Bhaskar K. Degradation and transmission of tau by autophagic-endolysosomal networks and potential therapeutic targets for tauopathy. Front Mol Neurosci. 2020;13:586731. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2020.586731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo T, Nho K, Bice P, Saykin AJ. Deep learning-based identification of genetic variants: application to Alzheimer's Disease classification. Brief Bioinform. 2022;23(2):bbac022. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbac022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WD, Griswold DP. Traumatic brain injury: a global challenge. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(12):949–950. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30362-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Stewart W. Age at injury influences dementia risk after TBI. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(3):128–130. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH. Axonal pathology in traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2013;246:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan KW, Carver KL, Maguire MM, Cubilla CE, Mackay TFC, Anholt RRH. Genome-wide association for sensitivity to chronic oxidative stress in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabadi SV, Faden AI. Neuroprotective strategies for traumatic brain injury: improving clinical translation. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(1):1216–1236. doi: 10.3390/ijms15011216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzenberger RJ, Chtarbanova S, Rimkus SA, Fischer JA, Kaur G, Seppala JM, Swanson LC, Zajac JE, Ganetzky B, Wassarman DA.. Death following traumatic brain injury in Drosophila is associated with intestinal barrier dysfunction. Elife. 2015a;2015:1–24. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzenberger RJ, Ganetzky B, Wassarman DA. Age and diet affect genetically separable secondary injuries that cause acute mortality following traumatic brain injury in Drosophila. G3. 2016;6(12):4151–4166. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.036194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzenberger RJ, Loewen CA, Bockstruck RT, Woods MA, Ganetzky B, Wassarman DA. A method to inflict closed head traumatic brain injury in Drosophila. J Vis Exp. 2015b(100):e52905. doi: 10.3791/52905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzenberger RJ, Loewen CA, Wassarman DR, Petersen AJ, Ganetzky B, Wassarman DA. A Drosophila model of closed head traumatic brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(44):E4152–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316895110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano D, Pinter K, Chlebowski M, Petralia RS, Wang Y-X, Nechiporuk AV, Drerup CM. Nudc regulated Lis1 stability is essential for the maintenance of dynamic microtubule ends in axon terminals. iScience. 2022;25(10):105072. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.105072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf-Nazzal R, Fasham J, Inskeep KA, Blizzard LE, Leslie JS, Wakeling MN, Ubeyratna N, Mitani T, Griffith JL, Baker W, et al. Bi-allelic CAMSAP1 variants cause a clinically recognizable neuronal migration disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2022;109(11):2068–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2022.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek PM, Jackson TC, Jha RM, Clark RSB, Okonkwo DO, Bayır H, Poloyac SM, Wagner AK, Empey PE, Conley YP, et al. Paths to successful translation of new therapies for severe traumatic brain injury in the golden age of traumatic brain injury research: a Pittsburgh vision. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37(22):2353–2371. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.6203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono N, Arai H. Platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolases: an overview and update. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2019;1864(6):922–931. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretzchmar D, Hasan G, Sharma S, Heisenberg M, Benzer S. The Swiss cheese mutant causes glial hyperwrapping and brain degeneration in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 1997;17(19):7425–7432. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07425.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudumala SR, Penserga T, Börner J, Slipchuk O, Kakad P, Lee LTH, Qureshi A, Pielage J, Godenschwege TA. Lissencephaly-1 dependent axonal retrograde transport of L1-type CAM neuroglian in the adult Drosophila central nervous system. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto K, Iguchi T, Ishida R, Uemura T, Sato M, Hirotsune S. Developmental downregulation of LIS1 expression limits axonal extension and allows axon pruning. Biol Open. 2017;6(7):1041–1055. doi:10.1242/bio.025999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton PF, Colombani J, Aerne BL, Tapon N. Drosophila ASPP regulates C-terminal src kinase activity. Dev Cell. 2007;13(6):773–782. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Sato Y, Nixon RA. Lysosomal proteolysis inhibition selectively disrupts axonal transport of degradative organelles and causes an Alzheimer's-like axonal distrophy. J Neurosci. 2011;31(21):7817–7830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6412-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y, Warrior R. The Drosophila Lissencephaly1 (DLis1) gene is required for nuclear migration. Dev Biol. 2000;226(1):57–72. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Liang J, Fu H. An update on the association between traumatic brain injury and Alzheimer's Disease: focus on tau pathology and synaptic dysfunction. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;120:372–386. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]