Abstract

Objective:

The double burden of malnutrition (DBM) has become an emerging public health issue in many low- and middle-income countries. This study aims to provide important evidence for the prevalence of different types of DBM at the national and subnational levels in Bangladesh.

Design:

The study utilised data from the latest Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) 2017–2018. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to identify the sociodemographic factors associated with DBM.

Setting:

Nationally representative cross-sectional survey.

Participants:

8697 mothers aged 15 to 49 years with <5 children.

Results:

The overall prevalence of the DBM was approximately 21 %, where the prevalence of overweight mother (OWM) & stunted child/wasted child/underweight child (SC/WC/UWC) and underweight mother (UWM) & overweight child (OWC) was 13·35 % and 7·69 %, respectively, with a higher prevalence among urban households (OWM & SC/WC/UWC = 14·22 %; UWM & OWC = 10·58 %) in Bangladesh. High inequality was observed among UWM & OWC dyads, concentration index (CI) = -0·2998, while low level of inequality of DBM were observed for OWM & SC (CI = 0·0153), OWM & WC (CI = 0·1165) and OWM & UWC (CI = 0·0135) dyads. We observed that the age and educational status of the mother, number of children, fathers’ occupation, size and wealth index of the household, and administrative division were significantly associated with all types of DBM.

Conclusions:

Health policymakers, concerned authorities and various stakeholders should stress the prevalence of DBM issues and take necessary actions aimed at identifying and addressing the DBM in Bangladesh.

Keywords: Double burden, Malnutrition, Mother–child dyads, Urban–rural, Bangladesh

In recent years, the double burden of malnutrition (DBM) has emerged as a global public health issue, particularly for low- and middle-income countries (LMIC)(1,2). According to the WHO, the DBM means the coexistence of undernutrition along with overweight and obesity, within individuals, households and populations, and across the life course(3). Due to rapid urbanisation, economic transition and demographic dividend (i.e. accelerated economic growth offered by the changes in the age structure of a population), many developing countries, including Bangladesh, are experiencing a nutritional transition(4). Children are particularly at risk as poor nutrition in the early years can have lasting consequences throughout life. Yet, various forms of childhood malnutrition, such as stunting, wasting, underweight, overweight and obesity, are very common across various societal groups in many LMIC(5). According to the latest data, globally, approximately 149·2 million, 45·4 million and 38·9 million children aged under 5 years were stunted, wasted and overweight, respectively, while approximately 20 million new-borns were born with low birth weight(3). It was estimated that 45 % of all deaths among children aged unde 5 years were directly related to childhood undernutrition, with most of these deaths occurring in Asia and Africa(3). The number of overweight children (OWC) aged under 5 years increased from 30 million in 2000 to 55·6 million in 2017(6). Further, a number of mothers in the developing world are also suffering from underweight, overweight and obesity-related malnutrition(7). Per the latest estimates, approximately 1·9 billion adults are overweight or obese and 462 million people are suffered underweight globally(8).

Although the prevalence of childhood undernutrition has declined substantially, the prevalence of undernourished children and underweight mothers (UWM) is high in rural areas and among the poorest wealth quintile in Bangladesh(1,9). Further, due to rapid changes in global food systems, increasing urbanisation, decreased physical activity, changes in lifestyle and changes in dietary intake, many developing countries, including Bangladesh, are experiencing overweight-related issues among children and mothers(7,10). As a consequence, the proportion of people with overweight and obesity has increased substantially, particularly among the wealthiest and most educated individuals and people living in urban areas(1,7).

Like other developing countries, Bangladesh is experiencing a coexistence of undernutrition and overweight conditions at the population, individual and household levels, a phenomenon referred to as the DBM, which is an emerging public health problem in Bangladesh(1). According to WHO guidelines, the DBM is characterised by the coexistence of undernutrition (including wasting, stunting and deficiencies in important micronutrients) with overweight, obesity or diet-related non-communicable diseases(3).

The concept of the DBM has emerged in the past three decades and recently received greater attention due to a recent series of papers in The Lancet, as it appears to be more permanent and widespread than previously perceived(11). It is well established that both being underweight and overweight have multifaceted consequences for survival, the incidence of chronic diseases, healthy development, and the economic productivity of individuals, societies, and healthcare systems(12). Both overnutrition and undernutrition are equally harmful. Undernutrition often hinders physical and intellectual development, whereas overnutrition is a significant contributor to various non-communicable diseases, including diabetes and hypertension. Both forms of malnutrition cause huge direct and indirect costs to individuals, families and nations; approximately US $3·5 trillion globally(13).

Bangladesh – a lower-middle-income country – has made remarkable progress in improving its population’s health over the past few decades. This may be due to the pluralistic healthcare system in which public providers, private providers and various non-governmental organisations are engaged in healthcare delivery in Bangladesh. As a consequence, the prevalence of childhood stunting (low height for age) was reduced from 51 % in 2004 to 31 % in 2017–2018, while the prevalence of underweight (low weight for age) was reduced from 43 % in 2004 to 22 % in 2017–2018(14). While childhood undernutrition constitutes an enormous burden, the prevalence of childhood overweight conditions (2 % in 2018) is an emerging public health problem in Bangladesh(14). Moreover, in terms of UWM, the prevalence decreased significantly from 30 % in 2007 to 12 % in 2017–2018, while the prevalence of overweight mothers (OWM) has increased alarmingly from 12 % in 2007 to 32 % in 2017–2018(14). Recently, an increasing trend of overweight or obese has been observed among urban and wealthier individuals in Bangladesh(15). It has been noted that UWM were found to coexist with OWC, and OWM were found to coexist with stunting, wasting, and underweight conditions in children within the same households in Bangladesh. The WHO policy brief on DBM indicated that most current policies tend to address either undernutrition or overweight and obesity, but not both; therefore, actions that address both conditions should be prioritised globally(3). Such double-duty actions include interventions, programmes and policies that have the potential to simultaneously lessen the risk or burden of both undernutrition and overnutrition. This is an urgent issue, as the coexistence of various forms of malnutrition among mothers and children has continued to rise not only in Bangladesh but globally. Notably, malnourished women are susceptible to experiencing complications related to pregnancy and childbirth(16).

A number of studies have identified the DBM in various settings globally(1,5). A recent multi-country study that included Bangladesh estimated the DBM using three separate combinations of overweight or obese mothers with undernourished children (i.e. underweight children (UWC), stunted children (SC) and wasted children (WC))(17). It was also observed that the prevalence of UWM remained high in rural areas, while the prevalence of OWM increased rapidly in both rural and urban areas, creating a DBM among mothers in Bangladesh(1). Another study predicted that by the year 2030, the prevalence of UWM would be highest among the poorest segment of society, and the prevalence of overweight and obesity would be highest among the richest segment in Bangladesh(5). A multi-country study conducted in Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and Myanmar referred to household-level DBM as the coexistence of OWM and SC in the same household only but did not focus on the other types of DBM(18). To the best of our knowledge, analysis of the UWM along with the overweight and obesity status of the children and the OWM along with the stunting, wasting and underweight status of the children in the same household to explore the status of DBM using nationally representative data in Bangladesh has not yet been performed. This study aims to provide important information about the prevalence of various forms of DBM at the national level and by urbanity in Bangladesh. The specific objectives of the study are to measure the prevalence, inequality and factors associated with the overall DBM at the household level in Bangladesh.

Materials and methods

Study population and data source

The study utilised data from the most recent Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) 2017–2018. The survey was carried out from October 2017 to March 2018 under the authority of the National Institute of Population Research and Training, Medical Education and Family Welfare Division, and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare(14). The BDHS is a vital source of records of data used in this study, including women’s BMI and records of stunting, wasting, underweight, and overweight conditions of children under 5 years of age. Women aged 15 to 49 years with at least one of their children living in the same household were the population of this study.

Survey design and sampling procedures

The BDHS 2017–2018 was a cross-sectional survey that used a two-stage stratified random sampling design to cover the entire population by taking a nationally representative sample. This survey used a list of enumeration areas and a standard sampling frame provided by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics(14). A total of 8772 individual mothers aged 15 to 49 years were enrolled in this study. However, seventy-five mothers were excluded, because no children lived in their households. Thus, a total of 8697 samples were analysed, with 2379 and 6319 mothers from urban and rural areas, respectively.

Outcome variables

The outcome variable was the prevalence of the DBM at the household level, disaggregated by urban and rural households. The DBM was defined as the coexistence of mothers’ underweight condition and children’s overweight condition or the coexistence of mothers’ overweight condition and children’s stunting, wasting, or underweight condition in the same household(3). Mothers’ nutritional burden was defined as the existence of underweight or overweight conditions in the mother, while children’s nutritional burden was defined as stunting, wasting, underweight or overweight conditions. The 2017–2018 BDHS used the WHO’s guidelines to determine the cut-off values for mothers’ BMI (i.e. underweight and overweight) and the stunting, wasting, underweight and overweight status of the children(14).

Explanatory variables

A number of explanatory variables were included in this study based on relevance and logical correlation with the DBM among women and children globally(1,2,5). The series of explanatory variables were as follows: age and educational and working status of the mother, mother’s age at first birth, number of children, father’s education and occupation, sex of children, child’s birth order, household size, toilet facilities, respondent’s exposure to mass media, wealth index, and administrative division of the households. The households of the study participants were categorised based on whether they were residing in urban or rural areas. Respondents’ age was categorised into three groups: 15–19 years, 20–29 years and 30–49 years. Maternal and paternal educational status were reported by the study participants and categorised as ‘no formal education’, ‘primary’, ‘secondary’ and ‘higher’. Mother’s age at first birth was categorised into three groups (less than 18, 18–24 and 25 or above), and working status of the mothers was categorised as ‘yes’ and ‘no’. Likewise, the respondent’s number of children was categorised into three groups (one child, two children, and three or more children). A composite score named the ‘wealth index’ was calculated using principal component analysis based on the household’s ownership of selected assets, availability of electricity supply, television, bicycle, materials used for housing construction, types of water access and sanitation facilities, use of health and other services, and health outcomes. Ultimately, the wealth index was used to categorise households into the ‘poorest’, ‘poorer’, ‘middle’, ‘richer’ and ‘richest’ quintiles(14).

Measurement of inequality

Measurement of inequality was performed using the concentration curves and concentration indices. The concentration curve provides the distribution of DBM among the socio-economic groups. The cumulative proportion of DBM in the vertical axis is depicted against the cumulative proportion of the samples regarding socio-economic status. If the DBM is more concentrated among poor people, the concentration curve will lie above the equity line and vice versa. If the concentration curve equals the 45-degree straight line exactly, this means that there is perfect equity in DBM with respect to the wealth index. The wealth index was calculated through principal component analysis using BDHS survey data. The concentration index (CI) shows the information contained in each concentration curve and is twice the area between the concentration curves and the equity line(19). The value of the CI lies between –1 and +1 (i.e. –1 ≤ CI ≤ + 1), where –1 refers to the case where DBM is entirely concentrated among the poorest quintile, and +1 refers to the case where malnutrition is entirely concentrated among the wealthiest quintile. Further, a value of 0 (zero) signifies perfect equality, i.e. there is no socio-economic inequity for the DBM.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis, such as frequency distribution and cross-tabulation, was applied for measuring the prevalence of DBM according to background variables. The inequality of DBM was measured by generating the Lorenz curve using Microsoft Office Excel version 16.0. Both adjusted and unadjusted logistic regression models were used to examine the significant risk factors. The dependent variable was expressed as binary, and it was represented as ‘1’ for the coexistence of mothers’ underweight condition and children’s overweight condition or the coexistence of mothers’ overweight condition and children’s stunting, wasting or underweight condition in the same household, while ‘0’ was represented for the non-coexistence of mothers’ underweight condition and children’s overweight condition or the coexistence of mothers’ overweight condition and children’s stunting, wasting or underweight condition in the same household. In the multivariable logistic regression models, results were presented as adjusted OR (AOR) with 95 % CIs. Results were considered to be statistically significant at the 5 % α level (P < 0·05). Since the BDHS survey used a two-stage stratified cluster sampling technique, the recommended sample weights provided by the BDHS were used for the analysis. All statistical analyses were carried out using the statistical package Stata/SE 14 software (Stata Corp.).

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants

The background characteristics of the study participants are described in Table 1. A total of 8697 women with at least one child aged up to 60 months were included in this analysis, with most of the participants living in rural areas (72·65 %). More than half of the respondents were young adults aged 20 to 29 years (62·41 %) and had completed secondary and higher education (63·8 %). Approximately 46 % and 37 % of rural and urban mothers, respectively, had their first pregnancy before 18 years of age, while 65 % of mothers had at least two children. Approximately 59 % of mothers had a BMI within the normal range, while 27 % were overweight or obese and 14 % were underweight. Approximately 52 % of the children were male. Approximately 31 % of the children were stunted, followed by underweight (22 %), wasted (8 %), obese (8 %) and overweight (2 %). Approximately one-third (31 %) of the study households were large in size (six or more family members), while only 13 % of the study households were small in size (<4 family members). Most of the participants (60 %) were using hygienic toilet facilities, and 42 % of the participants had access to mass media. According to the wealth index, 26 % of the rural population enrolled in the study were from the poorest quintile, and 45 % of the urban population enrolled in the study were from the richest quintile. The highest number of participants (26 %) belonged to the Dhaka division (largest administrative unit), followed by the Chittagong division (21 %), while the lowest number of participants (6 %) belonged to the Barisal division.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participant (n 8697)

| Variables | Urban (n 2379) | Rural (n 6319) | Overall (n 8697) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | |

| Double burden (all types) | ||||||

| Yes | 590 | 24·79 | 1240 | 19·62 | 1829 | 21·03 |

| Mothers age | ||||||

| 15–19 years | 275 | 11·58 | 833 | 13·19 | 1109 | 12·75 |

| 20–29 years | 1463 | 61·51 | 3965 | 62·75 | 5428 | 62·41 |

| 30–49 years | 640 | 26·92 | 1520 | 24·06 | 2161 | 24·84 |

| Mothers’ educational status | ||||||

| No formal education | 178 | 07·48 | 466 | 07·37 | 644 | 07·40 |

| Primary | 610 | 25·66 | 1894 | 29·98 | 2505 | 28·80 |

| Secondary | 1056 | 44·38 | 3156 | 49·94 | 4212 | 48·42 |

| Higher | 535 | 22·48 | 803 | 12·70 | 1337 | 15·38 |

| Mothers age at first birth | ||||||

| Less than 18 years | 871 | 36·61 | 2915 | 46·13 | 3785 | 43·52 |

| 18–24 years | 1306 | 54·91 | 3180 | 50·33 | 4486 | 51·58 |

| 25 years or more | 202 | 08·48 | 224 | 03·55 | 426 | 04·90 |

| Number of children | ||||||

| One child | 927 | 38·96 | 2101 | 33·25 | 3028 | 34·82 |

| Two children | 888 | 37·33 | 2300 | 36·40 | 3188 | 36·66 |

| Three or more child | 564 | 23·71 | 1917 | 30·34 | 2481 | 28·53 |

| Mothers BMI | ||||||

| Underweight | 258 | 10·84 | 926 | 14·65 | 1183 | 13·61 |

| Normal weight | 1189 | 49·96 | 3972 | 62·87 | 5161 | 59·34 |

| Overweight | 656 | 27·57 | 1101 | 17·43 | 1757 | 20·20 |

| Obese | 277 | 11·63 | 319 | 05·06 | 596 | 06·85 |

| Mothers working status | ||||||

| Yes | 772 | 32·44 | 2774 | 43·91 | 3546 | 40·77 |

| Fathers’ education | ||||||

| No formal education | 306 | 12·84 | 1155 | 18·28 | 1461 | 16·80 |

| Primary | 699 | 29·40 | 2238 | 35·43 | 2938 | 33·78 |

| Secondary | 763 | 32·08 | 2034 | 32·18 | 2797 | 32·16 |

| Higher | 611 | 25·67 | 891 | 14·11 | 1502 | 17·27 |

| Fathers’ occupation | ||||||

| Day labour | 1439 | 60·48 | 4650 | 73·59 | 6089 | 70·01 |

| Business | 643 | 27·02 | 1166 | 18·46 | 1809 | 20·80 |

| Service | 229 | 09·61 | 254 | 04·01 | 482 | 05·55 |

| Unemployed | 16 | 00·68 | 50 | 00·79 | 66 | 00·76 |

| Others | 52 | 02·20 | 199 | 03·15 | 251 | 02·89 |

| Sex of children | ||||||

| Male | 1207 | 50·74 | 3333 | 52·75 | 4540 | 52·20 |

| Female | 1172 | 49·26 | 2985 | 47·25 | 4157 | 47·80 |

| Child stunting (n 7818) | ||||||

| Yes | 524 | 25·32 | 1877 | 32·66 | 2402 | 30·72 |

| Child wasting (n 7804) | ||||||

| Yes | 186 | 09·02 | 473 | 08·24 | 659 | 08·44 |

| Child underweight (n 8041) | ||||||

| Yes | 407 | 19·10 | 1345 | 22·77 | 1753 | 21·80 |

| Child overweight (n 7781) | ||||||

| Yes | 45 | 02·20 | 72 | 01·25 | 117 | 01·50 |

| Child obesity | ||||||

| Yes | 253 | 10·65 | 419 | 06·63 | 672 | 07·73 |

| Birth order | ||||||

| First | 996 | 41·86 | 2340 | 37·04 | 3336 | 38·36 |

| Second | 799 | 33·58 | 1989 | 31·48 | 2788 | 32·05 |

| Third or more | 584 | 24·56 | 1989 | 31·48 | 2573 | 29·59 |

| Household size | ||||||

| Small (<4) | 421 | 17·72 | 722 | 11·42 | 1143 | 13·14 |

| Medium (4–6) | 1347 | 56·62 | 3508 | 55·51 | 4855 | 55·82 |

| Large (6 and more) | 610 | 25·66 | 2089 | 33·06 | 2700 | 31·04 |

| Division | ||||||

| Dhaka | 1109 | 46·63 | 1128 | 17·85 | 2237 | 25·73 |

| Chittagong | 466 | 19·60 | 1343 | 21·25 | 1809 | 20·80 |

| Rajshahi | 182 | 07·65 | 828 | 13·10 | 1010 | 11·61 |

| Rangpur | 133 | 05·61 | 786 | 12·44 | 920 | 10·57 |

| Khulna | 184 | 07·74 | 612 | 09·69 | 796 | 09·16 |

| Mymensingh | 122 | 05·12 | 604 | 09·56 | 726 | 08·34 |

| Sylhet | 104 | 04·37 | 612 | 09·69 | 716 | 08·23 |

| Barisal | 78 | 03·28 | 406 | 06·42 | 484 | 05·56 |

| Toilet facility | ||||||

| Hygienic | 1871 | 78·64 | 3389 | 53·64 | 5260 | 60·48 |

| Unhygienic | 508 | 21·36 | 2929 | 46·36 | 3437 | 39·52 |

| Mass media exposure | ||||||

| Yes | 1501 | 63·08 | 2184 | 34·56 | 3684 | 42·36 |

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Poorest | 206 | 08·64 | 1669 | 26·41 | 1874 | 21·55 |

| Poorer | 149 | 06·24 | 1617 | 25·59 | 1766 | 20·30 |

| Middle | 279 | 11·72 | 1353 | 21·42 | 1632 | 18·77 |

| Richer | 672 | 28·24 | 1073 | 16·97 | 1744 | 20·05 |

| Richest | 1074 | 45·16 | 607 | 09·60 | 1681 | 19·33 |

| Total | 2379 | 27·35 | 6319 | 72·65 | 8697 | 100 |

Prevalence of double burden of malnutrition across background characteristics

The prevalence of DBM across background characteristics is described in Table 2. The overall prevalence of DBM characterised by OWM & SC/WC/UWC and UWM & OWC was 13·35 % and 7·69 %, respectively. Although a similar pattern was found for both OWM’s dyad with undernourished child (urban: 14·22 % and rural: 13·02 %) and UWM’s dyad with OWC (urban: 10·58 % and rural: 6·60 %), the differences between urban and rural were much higher among the UWM & OWC dyad. The prevalence of DBM increased gradually as mothers’ age increased, and the highest DBM was found among the mothers aged 30–49 years (OWM & SC/WC/UWC: 15·89 % and UWM & OWC: 9·14 %). The highest prevalence of DBM (OWM & SC/WC/UWC: 15·58 % and UWM & OWC: 11·49 %) was noticed among the mothers who had no formal education, while the urban–rural difference was found higher among OWM & SC/WC/UWC dyads (urban: 19·86 % and rural: 13·94 %) and the lowest prevalence was found for the highest educated mothers. We found that mothers in urban areas who had their first child after age 24 were more prone to both OWM & SC/WC/UWC (15·66 %) and UWM & OWC (13·47 %) dyads. Such pattern was not observed among rural mothers.

Table 2.

Prevalence of double burden of malnutrition (OWM & SC/WC/UWC, UWM & OWC) by sociodemographic characteristics

| Variables | OWM & SC/WC/UWC | UWM & OWC | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Overall | Urban | Rural | Overall | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Mothers age | ||||||||||||

| 15–19 years | 31 | 11·15 | 81 | 09·67 | 111 | 10·04 | 22 | 08·01 | 48 | 05·72 | 70 | 06·29 |

| 20–29 years | 199 | 13·62 | 507 | 12·78 | 706 | 13·01 | 156 | 10·67 | 245 | 06·19 | 401 | 07·40 |

| 30–49 years | 108 | 16·91 | 235 | 15·46 | 343 | 15·89 | 73 | 11·47 | 124 | 08·15 | 197 | 09·14 |

| P-value | 0·025 | 0·001 | 0·000 | 0·394 | 0·023 | 0·016 | ||||||

| Mothers’ educational status | ||||||||||||

| No formal education | 35 | 19·86 | 65 | 13·94 | 100 | 15·58 | 22 | 12·38 | 52 | 11·15 | 74 | 11·49 |

| Primary | 98 | 16·09 | 239 | 12·61 | 337 | 13·46 | 67 | 11·00 | 142 | 07·49 | 209 | 08·34 |

| Secondary | 146 | 13·84 | 429 | 13·59 | 575 | 13·65 | 109 | 10·30 | 175 | 05·55 | 284 | 06·75 |

| Higher | 59 | 10·94 | 90 | 11·20 | 148 | 11·09 | 54 | 10·03 | 48 | 05·97 | 102 | 07·60 |

| P-value | 0·033 | 0·269 | 0·029 | 0·401 | 0·001 | 0·001 | ||||||

| Mothers age at first birth | ||||||||||||

| Less than 18 years | 131 | 15·05 | 360 | 12·35 | 491 | 12·98 | 94 | 10·8 | 226 | 07·74 | 320 | 08·44 |

| 18–24 years | 175 | 13·43 | 437 | 13·75 | 613 | 13·66 | 130 | 09·98 | 176 | 05·52 | 306 | 06·82 |

| 25 years or more | 32 | 15·66 | 25 | 11·24 | 57 | 13·34 | 27 | 13·47 | 16 | 07·10 | 43 | 10·12 |

| P-value | 0·172 | 0·053 | 0·681 | 0·329 | 0·007 | 0·005 | ||||||

| Number of children | ||||||||||||

| One child | 110 | 11·88 | 248 | 11·78 | 358 | 11·82 | 122 | 13·13 | 165 | 07·84 | 287 | 09·46 |

| Two children | 131 | 14·77 | 288 | 12·54 | 420 | 13·16 | 74 | 08·31 | 123 | 05·35 | 197 | 06·17 |

| Three or more child | 97 | 17·17 | 287 | 14·95 | 383 | 15·45 | 56 | 09·94 | 129 | 06·74 | 185 | 07·47 |

| P-value | 0·008 | 0·015 | 0·000 | 0·002 | 0·005 | 0·000 | ||||||

| Mothers working status | ||||||||||||

| No | 229 | 14·27 | 489 | 13·80 | 718 | 13·94 | 140 | 08·71 | 226 | 06·37 | 366 | 07·10 |

| Yes | 109 | 14·11 | 333 | 12·02 | 442 | 12·47 | 112 | 14·45 | 191 | 06·90 | 303 | 08·54 |

| P-value | 0·842 | 0·011 | 0·047 | 0·000 | 0·660 | 0·035 | ||||||

| Fathers’ education | ||||||||||||

| No formal education | 46 | 15·12 | 150 | 13·00 | 196 | 13·44 | 33 | 10·64 | 108 | 09·38 | 141 | 09·65 |

| Primary | 105 | 14·97 | 274 | 12·26 | 379 | 12·90 | 71 | 10·12 | 135 | 06·04 | 206 | 07·01 |

| Secondary | 115 | 15·01 | 288 | 14·14 | 402 | 14·38 | 70 | 09·12 | 120 | 05·89 | 189 | 06·77 |

| Higher | 73 | 11·90 | 110 | 12·39 | 183 | 12·19 | 79 | 12·88 | 54 | 06·02 | 132 | 08·81 |

| P-value | 0·073 | 0·635 | 0·338 | 0·051 | 0·000 | 0·000 | ||||||

| Fathers’ occupation | ||||||||||||

| Day labour | 210 | 14·56 | 630 | 13·55 | 840 | 13·79 | 147 | 10·21 | 293 | 06·29 | 439 | 07·22 |

| Business | 91 | 14·16 | 134 | 11·47 | 225 | 12·42 | 67 | 10·37 | 74 | 06·35 | 141 | 07·78 |

| Service | 31 | 13·46 | 25 | 09·75 | 56 | 11·51 | 26 | 11·44 | 22 | 08·57 | 48 | 09·93 |

| Others | 02 | 09·88 | 06 | 12·72 | 08 | 12·03 | 02 | 09·66 | 05 | 10·30 | 07 | 10·14 |

| Unemployed | 05 | 09·97 | 28 | 13·82 | 33 | 13·02 | 10 | 19·78 | 24 | 11·83 | 34 | 13·49 |

| P-value | 0·776 | 0·301 | 0·613 | 0·030 | 0·004 | 0·000 | ||||||

| Sex of children | ||||||||||||

| Male | 183 | 15·15 | 427 | 12·81 | 610 | 13·43 | 126 | 10·48 | 224 | 06·73 | 351 | 07·73 |

| Female | 155 | 13·25 | 396 | 13·25 | 551 | 13·25 | 125 | 10·67 | 193 | 06·45 | 318 | 07·64 |

| P-value | 0·313 | 0·561 | 0·902 | 0·700 | 0·979 | 0·738 | ||||||

| Birth order | ||||||||||||

| First | 118 | 11·81 | 283 | 12·10 | 401 | 12·01 | 118 | 11·81 | 154 | 06·57 | 271 | 08·13 |

| Second | 121 | 15·19 | 258 | 12·96 | 379 | 13·60 | 70 | 08·73 | 116 | 05·81 | 185 | 06·65 |

| Third or more | 99 | 16·98 | 282 | 14·16 | 381 | 14·80 | 64 | 11·00 | 148 | 07·43 | 212 | 08·24 |

| P-value | 0·005 | 0·134 | 0·004 | 0·117 | 0·223 | 0·068 | ||||||

| Household size | ||||||||||||

| Small (<4) | 61 | 14·47 | 101 | 14·01 | 162 | 14·18 | 85 | 20·06 | 75 | 10·39 | 159 | 13·95 |

| Medium (4–6) | 189 | 14·06 | 455 | 12·97 | 644 | 13·28 | 116 | 08·64 | 208 | 05·93 | 324 | 06·68 |

| Large (6 and more) | 88 | 14·39 | 266 | 12·75 | 354 | 13·12 | 51 | 08·30 | 134 | 06·41 | 185 | 06·84 |

| P-value | 0·866 | 0·841 | 0·898 | 0·000 | 0·000 | 0·000 | ||||||

| Division | ||||||||||||

| Dhaka | 179 | 16·10 | 131 | 11·63 | 310 | 13·85 | 156 | 14·10 | 77 | 06·81 | 233 | 10·42 |

| Chittagong | 61 | 13·14 | 194 | 14·46 | 255 | 14·12 | 43 | 09·21 | 99 | 07·35 | 142 | 07·83 |

| Rajshahi | 20 | 10·90 | 132 | 15·91 | 152 | 15·01 | 14 | 07·77 | 46 | 05·60 | 60 | 05·99 |

| Rangpur | 21 | 15·56 | 81 | 10·28 | 102 | 11·05 | 08 | 05·97 | 45 | 05·78 | 53 | 05·81 |

| Khulna | 18 | 09·54 | 70 | 11·37 | 87 | 10·95 | 13 | 06·88 | 34 | 05·60 | 47 | 05·90 |

| Mymensingh | 19 | 15·90 | 61 | 10·16 | 81 | 11·12 | 05 | 04·45 | 39 | 06·51 | 45 | 06·17 |

| Sylhet | 10 | 09·62 | 96 | 15·77 | 106 | 14·87 | 08 | 07·55 | 46 | 07·50 | 54 | 07·51 |

| Barisal | 11 | 13·74 | 57 | 14·10 | 68 | 14·04 | 04 | 05·40 | 30 | 07·44 | 34 | 07·11 |

| P-value | 0·018 | 0·001 | 0·101 | 0·000 | 0·507 | 0·000 | ||||||

| Toilet facility | ||||||||||||

| Hygienic toilet facility | 274 | 14·63 | 465 | 13·71 | 738 | 14·04 | 209 | 11·17 | 200 | 05·90 | 409 | 07·77 |

| Unhygienic toilet facility | 65 | 12·69 | 358 | 12·22 | 422 | 12·29 | 43 | 08·39 | 217 | 07·41 | 260 | 07·55 |

| P-value | 0·262 | 0·041 | 0·019 | 0·107 | 0·041 | 0·807 | ||||||

| Mass media exposure | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 219 | 14·58 | 306 | 13·99 | 524 | 14·23 | 159 | 10·60 | 129 | 05·92 | 288 | 07·83 |

| No | 119 | 13·59 | 517 | 12·50 | 636 | 12·69 | 92 | 10·53 | 288 | 06·96 | 380 | 07·59 |

| P-value | 0·318 | 0·038 | 0·024 | 0·942 | 0·062 | 0·874 | ||||||

| Wealth index | ||||||||||||

| Poorest | 26 | 12·58 | 207 | 12·38 | 232 | 12·40 | 16 | 07·87 | 126 | 07·53 | 142 | 07·57 |

| Poorer | 25 | 17·12 | 176 | 10·91 | 202 | 11·43 | 9 | 05·96 | 115 | 07·10 | 124 | 07·00 |

| Middle | 33 | 11·66 | 177 | 13·07 | 209 | 12·83 | 20 | 07·11 | 72 | 05·28 | 91 | 05·59 |

| Richer | 109 | 16·28 | 172 | 16·06 | 282 | 16·14 | 75 | 11·10 | 62 | 05·77 | 136 | 07·82 |

| Richest | 145 | 13·50 | 90 | 14·90 | 235 | 14·00 | 132 | 12·31 | 43 | 07·10 | 175 | 10·43 |

| P-value | 0·319 | 0·002 | 0·009 | 0·012 | 0·213 | 0·001 | ||||||

| Overall | 338 | 14·22 | 823 | 13·02 | 1161 | 13·35 | 252 | 10·58 | 417 | 06·60 | 669 | 07·69 |

| P-value | 0·730 | 0·000 | ||||||||||

OWM, overweight mother; SC, stunted child; WC, wasted child; UWC, underweight child; UWM, underweight mother; OWC, overweight child.

DBM in terms of OWM & SC/WC/UWC dyads (15·45 %) was most prevalent among the mothers who had three or more children at the time of the survey. However, a different scenario was found for the UWM & OWC dyads and mothers with a single child (10 %) were more prone to DBM, while the scenario was more common in urban areas (13·13 %) than rural areas (7·84 %). The results indicated that the DBM was more prevalent among the children whose fathers had no formal education than among those whose fathers had a higher educational level. Male children had a slightly higher prevalence of the DBM than female children, while urban male children had suffered more (OWM & SC/WC/UWC dyads, 15·15 %, and UWM & OWC dyads, 10·48 %) than rural male children. Children whose birth order was third or more were more prone to DBM in both urban and rural areas for all dyads. The prevalence of DBM was found to be highest among the small (<4 family members) households (OWM & SC/WC/UWC: 14·18 % and UWM & OWC: 13·95 %) compared to both the medium (4–6 family members) and large (six or more family members) households. However, the differences between urban and rural were much higher among UWM & OWC dyads, particularly for small households. In terms of division, Dhaka was found to be the most prevalent for UWM & OWC dyads (10·42 %), while the OWM & SC/WC/UWC dyads were more common in Sylhet division (15 %). The prevalence of DBM characteristics by UWM & OWC dyads was highest (10·43 %) among the richest households, while the prevalence of OWM & SC/WC/UWC dyads was high among richer households (16·14 %) followed by the richest households (14 %).

Prevalence of various forms of double burden of malnutrition among residents of rural and urban areas

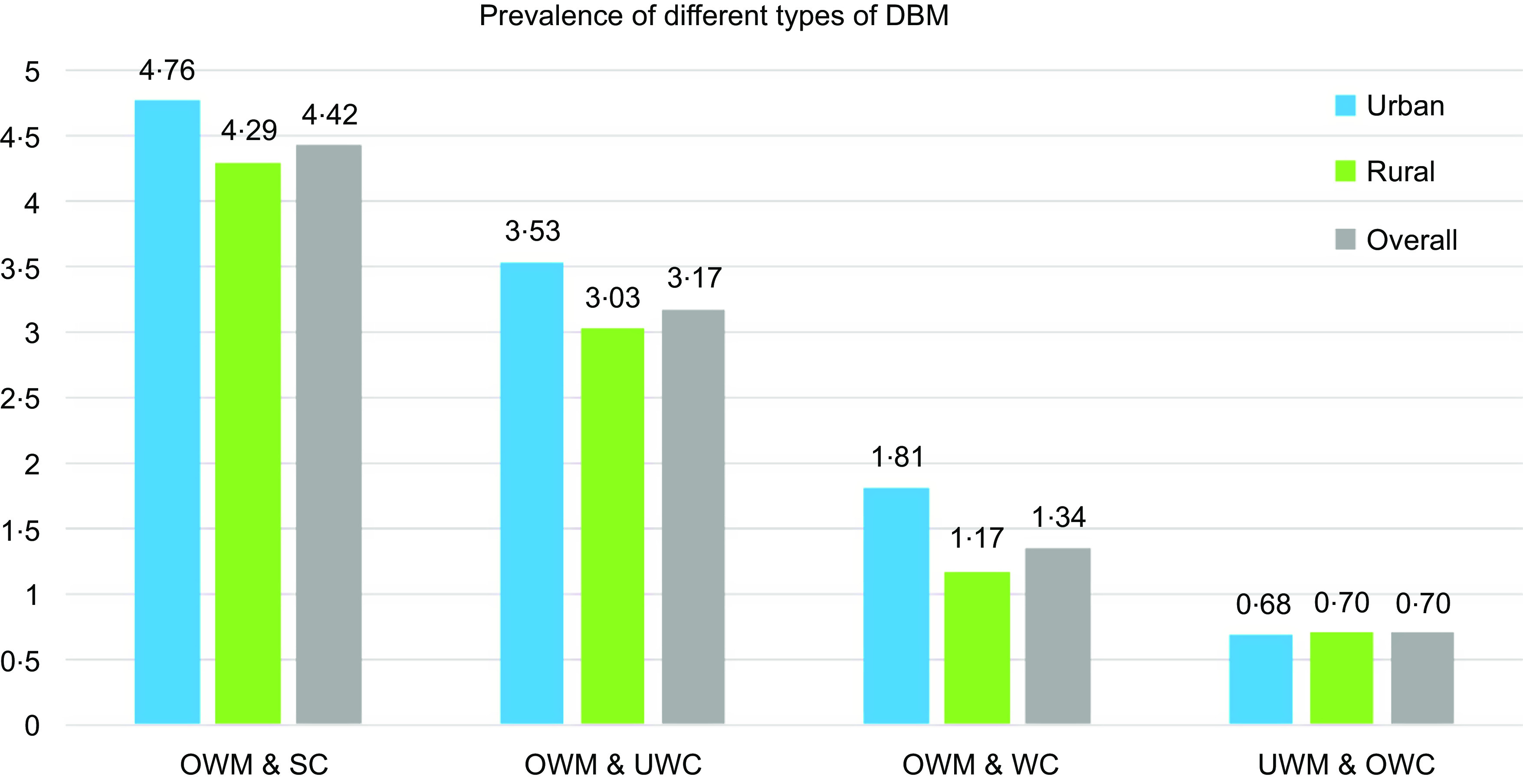

The prevalence of various forms of DBM is shown in Fig. 1. The DBM paired households were categorised as: OWM & SC; OWM & UWC; OWM & WC; and UWM & OWC. The overall prevalence of DBM was highest for OWM & SC (4·42 %), followed by OWM & UWC (3·17 %). In urban areas, the prevalence of OWM & SC was higher (4·76 %) than the overall prevalence of this pair and was the most common pair, followed by OWM & UWC (3·53 %). In the rural areas, OWM & SC (4·29 %) and OWM & UWC (3·03 %) were more prevalent DBM pairs.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of various forms of DBM among residents of rural and urban areas. DBM, double burden of malnutrition; OWM, overweight mother; SC, stunted child; WC, wasted child; UWC, underweight child; UWM, underweight mother; OWC, overweight child

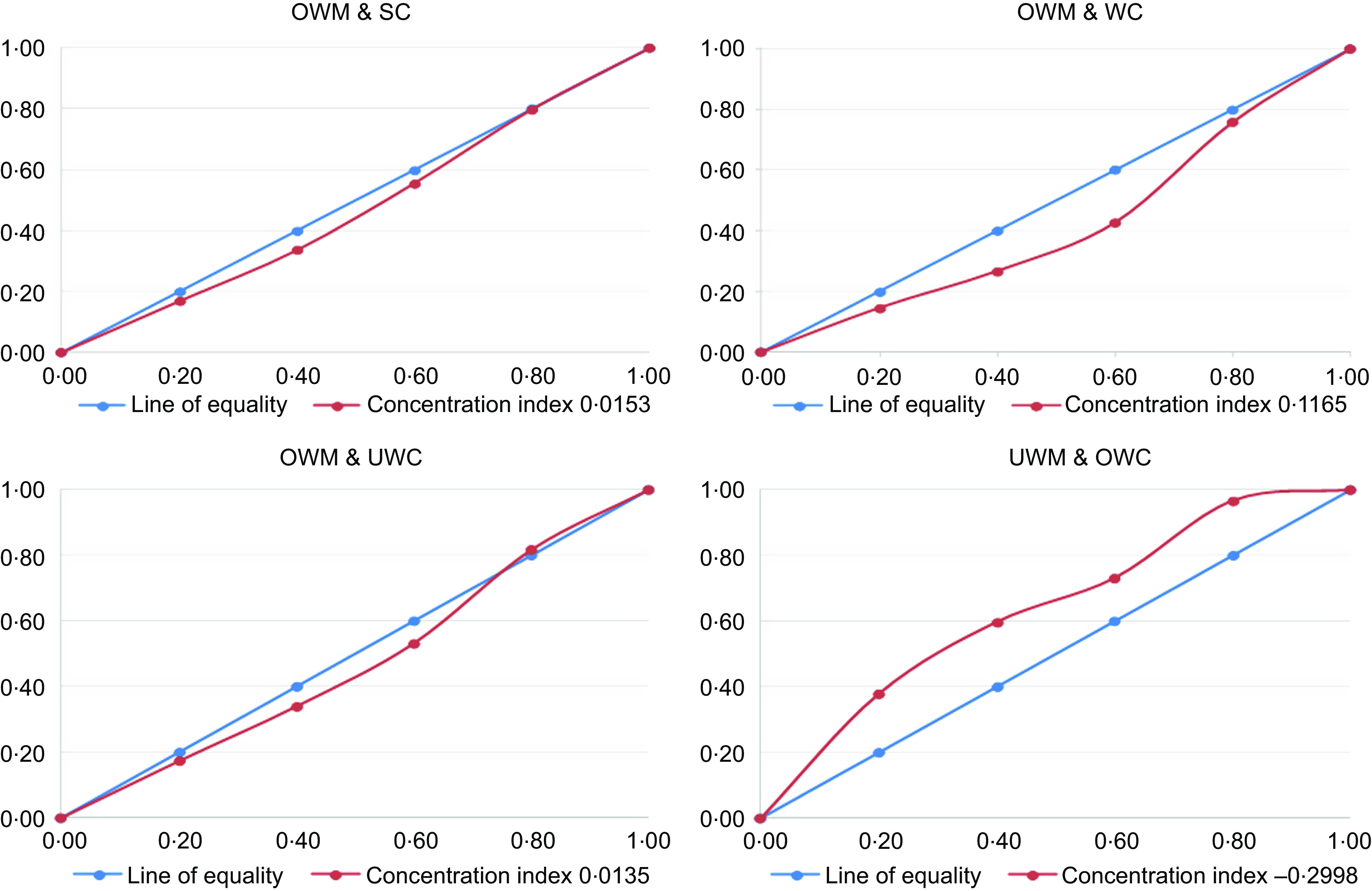

Inequality in the prevalence of different types of double burden of malnutrition

Figure 2 shows the inequality of the prevalence of various forms of DBM using concentration curves. High inequality was observed among the UWM & OWC (CI -0·3) dyad, which indicated that poor households were more vulnerable to this type of DBM. A low level of inequality of DBM were observed for OWM & SC (CI 0·015), OWM & WC (CI 0·116) and OWM & UWC (CI 0·013) dyads.

Fig. 2.

Inequality in the prevalence of different types of double burden of malnutrition. OWM, overweight mother; SC, stunted child; WC, wasted child; UWC, underweight child; UWM, underweight mother; OWC, overweight child

Factors associated with the double burden of malnutrition

Table 3 shows the various risk factors associated with the DBM (OWM & SC/WC/UWC and UWM & OWC) across background characteristics. We observed that the age and educational status of the mother, number of children, fathers’ occupation, size of the household, administrative division and wealth index of the household were significantly associated with the OWM & SC/WC/UWC dyads, but no significant associations were found for fathers’ education, place of residence and birth order of the child with the same dyads in the adjusted model. We observed a positive relationship between the age of the mother and DBM for such dyads. The risk of DBM was 1·36 (95 % CI (1·08, 1·71); P = 0·01) and 1·73 (95 % CI (1·30, 2·30); P = 0·001) times higher among individual mothers aged 20–29 years and 30–49 years, respectively, than the reference age group (mothers aged 15–19 years). Uneducated mothers (AOR 1·71; 95 % CI (1·21, 2·40); P = 0·001), educated mothers who completed primary education (AOR 1·45; 95 % CI (1·11, 1·90); P = 0·01) and secondary education (AOR 1·39; 95 % CI (1·10, 1·74); P = 0·01) were more likely to exhibit the DBM compared to higher-educated mothers, and this difference was statistically significant for OWM & SC/WC/UWC dyads. However, mothers having two children (AOR 0·76; 95 % CI (0·57, 1·00); P = 0·03) and fathers doing business (AOR 0·83; 95 % CI (0·71, 0·98); P = 0·03) were less likely to DBM for such dyads. A higher risk of DBM was observed among the small households (AOR 1·30; 95 % CI (1·05, 1·62); P = 0·01) compared to the larger households. According to the administrative divisions, the DBM was less prevalent in the Rangpur division (AOR 0·75; 95 % CI (0·57, 0·98); P = 0·03), Khulna division (AOR 0·68; 95 % CI (0·51, 0·91); P = 0·01) and Mymensingh (AOR 0·72; 95 % CI (0·54, 0·96); P = 0·03) than the reference division (Rajshahi) for OWM & SC/WC/UWC dyads. In addition, such DBM was more common among richer (AOR 1·46; 95 % CI (1·18, 1·81); P = 0·001) and richest (AOR 1·38; 95 % CI (1·06, 1·78); P = 0·01) households compared to the poorest households.

Table 3.

Factors associated with household-level double burden of malnutrition (OWM & SC/WC/UWC, UWM & OWC) among mother–child dyads in Bangladesh

| Variables | OWM & SC/WC/UWC (n 8038) | UWM & OWC (n 7537) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95 % CI | AOR | 95 % CI | |

| Mothers age | ||||

| 15–19 years (ref.) | ||||

| 20–29 years | 1·36** | 1·08, 1·71 | 1·50** | 1·13, 2·01 |

| 30–49 years | 1·73*** | 1·30, 2·30 | 1·97*** | 1·38, 2·83 |

| Mothers’ educational status | ||||

| No formal education | 1·71*** | 1·21, 2·40 | 2·29*** | 1·51, 3·48 |

| Primary | 1·45** | 1·11, 1·90 | 1·76*** | 1·25, 2·48 |

| Secondary | 1·39** | 1·10, 1·74 | 1·35* | 1·01, 1·81 |

| Higher (ref.) | ||||

| Number of children | ||||

| One child | 0·71 | 0·49, 1·04 | 3·27*** | 2·08, 5·14 |

| Two children | 0·76* | 0·57, 1·00 | 1·42* | 1·00, 2·01 |

| Three or more child (ref.) | ||||

| Fathers’ education | ||||

| No formal education | 0·95 | 0·71, 1·27 | 0·91 | 0·64, 1·31 |

| Primary | 0·94 | 0·74, 1·21 | 0·78 | 0·57, 1·07 |

| Secondary | 1·07 | 0·85, 1·35 | 0·79 | 0·59, 1·06 |

| Higher (ref.) | ||||

| Fathers’ occupation | ||||

| Day labour (ref.) | ||||

| Business | 0·83* | 0·71, 0·98 | 1·06 | 0·86, 1·31 |

| Service | 0·87 | 0·62, 1·23 | 1·22 | 0·83, 1·80 |

| Unemployed | 0·79 | 0·37, 1·69 | 1·27 | 0·55, 2·90 |

| Others | 1·01 | 0·69, 1·50 | 1·79** | 1·19, 2·70 |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Urban | 1·03 | 0·87, 1·21 | 1·32** | 1·07, 1·62 |

| Rural (ref.) | ||||

| Birth order | ||||

| First (ref.) | ||||

| Second | 0·97 | 0·75, 1·26 | 1·55** | 1·13, 2·14 |

| Third or more | 0·77 | 0·53, 1·12 | 2·36*** | 1·51, 3·69 |

| Household size | ||||

| Small (<4) | 1·30** | 1·05, 1·62 | 1·91*** | 1·48, 2·45 |

| Medium (4–6) | 1·01 | 0·88, 1·17 | 0·96 | 0·79, 1·17 |

| Large (6 and more) (ref.) | ||||

| Division | ||||

| Dhaka | 0·86 | 0·69, 1·07 | 1·48** | 1·09, 2·02 |

| Chittagong | 0·90 | 0·72, 1·13 | 1·39* | 1·01, 1·93 |

| Rajshahi (ref.) | ||||

| Rangpur | 0·75* | 0·57, 0·98 | 0·94 | 0·64, 1·39 |

| Khulna | 0·68** | 0·51, 0·91 | 0·95 | 0·64, 1·42 |

| Mymensingh | 0·72* | 0·54, 0·96 | 0·98 | 0·65, 1·47 |

| Sylhet | 0·95 | 0·72, 1·26 | 1·21 | 0·81, 1·80 |

| Barisal | 1·00 | 0·73, 1·37 | 1·25 | 0·80, 1·96 |

| Wealth index | ||||

| Poorest (ref.) | ||||

| Poorer | 0·94 | 0·76, 1·15 | 1·00 | 0·77, 1·30 |

| Middle | 1·07 | 0·87, 1·33 | 0·75 | 0·56, 1·01 |

| Richer | 1·46*** | 1·18, 1·81 | 0·99 | 0·74, 1·31 |

| Richest | 1·38** | 1·06, 1·78 | 1·24 | 0·89, 1·72 |

| Constant | 0·12*** | 0·07, 0·21 | 0·01*** | 0·01, 0·03 |

| n | 8038 | 7537 | ||

| LR χ2(30) | 99·48 | 217·97 | ||

| Prob > χ2 | 0·000 | 0·000 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0·015 | 0·0483 | ||

| Log likelihood | −3267·52 | −2148·57 | ||

| Mean VIF | 3·10 | 3·04 | ||

OWM, overweight mother; SC, stunted child; WC, wasted child; UWC, underweight child; UWM, underweight mother; OWC, overweight child; AOR, adjusted odds ratio (control factors: mother age at first birth, working status of mothers, sex of children, type of toilet facility and exposure of mass media).

P < 0·05.

P < 0·01.

P < 0·001.

The age and educational status of the mother, the number of children, the fathers’ occupation, place of residence, birth order of the children, the size of the household and administrative division were significantly associated with the UWM & OWC dyads in the adjusted model. The prevalence of DBM characteristics by UWM & OWC dyads was highest among the mothers aged 30–49 years old (AOR 1·97; 95 % CI (1·38, 2·83); P = 0·001) and the mothers aged 20–29 years old (AOR 1·50; 95 % CI (1·13, 2·01); P = 0·01), respectively. Uneducated mothers (AOR 2·29; 95 % CI (1·51, 3·48); P = 0·001), primarily educated mothers (AOR 1·76; 95 % CI (1·25, 2·48); P = 0·001) and secondary educated mothers (AOR 1·35; 95 % CI (1·01, 1·81); P = 0·03) were significantly more likely to manifest the UWM & OWC dyads compared to higher-educated mothers. Mothers having one child were 3·27 times (95 % CI (2·08, 5·14); P = 0·001) and two children were 1·42 times (95 % CI (1·00, 2·01); P = 0·03) more likely to encounter DBM for such dyads compared to the reference group (three or more child) where the urban households were more prone to DBM characterised by maternal undernutrition and child overnutrition (AOR 1·32; 95 % CI (1·07, 1·62); P = 0·01) than the rural areas for such dyads. According to birth order, second and third or more child were 1·55 and 2·36 times significantly more likely to exhibit DBM, respectively, for UWM & OWC dyads. We noticed a positive relationship between the small households (AOR 1·91; 95 % CI (1·48, 2·45); P = 0·001) and DBM compared to the larger households for similar dyads. Dhaka (AOR 1·48; 95 % CI (1·09, 2·02); P = 0·01) and Chittagong (AOR 1·39; 95 % CI (1·01, 1·93); P = 0·03) divisions were more likely to exhibit DBM characterised by UWM & OWC dyads.

Discussion

Although Bangladesh has made substantial progress in reducing childhood undernutrition in the past decade, the rapid rise in overweight condition is a major challenge. Further, the prevalence of malnutrition among women of reproductive age is a major concern in Bangladesh(17). To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the prevalence of DBM that considers all forms of pairwise coexistence of malnutrition among mothers and children at the household level using nationwide representative data. Our findings provide a new perspective to researchers, policymakers and public health agencies, who can take initiatives to reduce this emerging public health burden in Bangladesh.

This study observed that the overall prevalence of the DBM at the household level was approximately 21 %, where the prevalence of OWM & SC/WC/UWC and UWM & OWC was 13·35 % and 7·69 %, respectively, with a significantly higher prevalence among urban households in Bangladesh. Bangladesh is experiencing rapid urban population growth; nonetheless, urban health is often neglected(20). Further, the large-scale unplanned rural–urban migration resulted in overloaded public services, scarcity of housing, inappropriate diets, unreachable healthcare facilities, and an adverse impact on health and the environment in many urban settings in Bangladesh(21). In addition, various restaurants, supermarkets and food parks are gaining popularity in urban Bangladesh, serving as places for recreational family activities(22). This changes the everyday food intake of urban residents, and junk food or ultra-processed food consumption was notably high among these residents due to various enabling factors, such as addictive taste, changing lifestyles, propagandist advertising and instant availability, while it resulted in obesity in children but also undernutrition in mothers because of the lack of essential nutrients for normal growth(23). According to the latest urban health survey, only a negligible improvement in childhood nutritional status was observed over the last 7 years, with maternal health indicators being particularly unsatisfactory among slum dwellers, who comprise one-third of the urban population in Bangladesh(24). There are approximately fourteen thousand urban slums in Bangladesh, and these areas exhibit many factors that negatively affect the health and nutrition of both mothers and their children(25). Other studies found a positive association between urbanisation and BMI in various settings(26,27).

A recent systematic review indicated an increasing trend in overweight and obesity among children, adolescents, and adults over time, with a higher prevalence in urban areas of Bangladesh(15). A recent study observed that the prevalence of overweight was significantly higher in women (79 % v. 53 %) than in men in urban Bangladesh(28). In contrast, rural mothers are more prone to underweight than urban mothers in Bangladesh, as has been observed in other resource-poor countries(29,30). A recent multi-country study reported that women living in rural communities had a greater risk of having UWC than urban mothers(31). Further, the prevalence of childhood undernutrition is more common in rural than in urban communities in many settings(9,29). Previous studies observed that the prevalence of childhood malnutrition was higher among Bangladeshi rural children, a phenomenon that has been frequently observed in other developing countries(9,17)

This study assessed four different forms of DBM at the household level: UWM & OWC, OWM & SC, OWM & WC, and OWM & UWC. Between 2004 and 2014, there was a 15 % increase in the prevalence of overweight status and a similar decrease in the underweight status of women of reproductive age. The reduction in underweight status was of similar magnitude in both urban and rural areas, whereas there was a greater relative change in overweight status in the rural areas, which is congruent with recent review findings(32). The underweight prevalence in rural areas remained relatively high, as did the overweight prevalence among urban residents. These findings, indicating a shift of nutritional burdens, are an extension of previous findings, demonstrating consistency with the literature from Bangladesh(1,33). Similar to what had previously been observed in many LMIC, this study found that the OWM & SC pair was the most prevalent DBM at the household level(17,34). Compared with the neighbouring countries, the prevalence of OWM & SC we observed is lower than that previously reported in India (8 %) and Pakistan (24 %)(17). Likewise, a higher prevalence of OWM & SC was also observed in many African and Latin American countries, including Egypt (12·5 %), Ghana (12·5 %), Nicaragua (12·5 %), Bolivia (15 %), Peru (16 %) and Guatemala (23 %)(34). Although our study did not attempt to identify the underlying reason for this difference, increases in the prevalence of overweight women in South and Southeast Asia in recent decades appear to be an important factor(35). Regarding the OWM & UWC pair, our results were in accordance with reports from 18 LMIC in South Asia, Africa and Latin America, where the prevalence ranged from 0·3 % to 5·3 %(35). This study found that the prevalence of OWM & WC at the household level in Bangladesh was lower than that observed in other settings like Nepal (5 %), Myanmar (6 %), India (7 %), Maldives (12 %) and Pakistan (14 %)(34). This is likely because the prevalence of wasting (8 %) is much lower than that of stunting (31 %) and underweight (22 %) among Bangladeshi children(14).

This study highlights the socio-economic inequality of the DBM, particularly for the UWM and OWC dyads, with poor households at a greater disadvantage than the rich. Of note, the current situation of maternal undernutrition in Bangladesh is similar to that observed in other LMIC(36,37). Various studies found that the wealth index plays a vital role in shaping women’s nutritional status and that mothers from poor households in Bangladesh were more prone to being underweight(33).Social expectations regarding body size, beliefs and cultural practices about food, nutrition, and physical activity may explain the association between overweight status and higher wealth quintiles(2,17). For instance, a recommendation to follow a reduced-fat diet at the household level can reduce the BMI for those with overweight and obesity, but this intervention could increase the risk for underweight members in the same household. In such a situation, prevention programmes should provide health information that promotes the optimal weight for all individuals in the household. For example, an intervention of reduced energy consumption should be implemented for overweight individuals, particularly for urban residents and those belonging to the wealthiest strata(38). In such interventions, the target population needs to be motivated to consume food with fewer calories and to increase physical activity such as walking. Awareness programmes about the consequences of being overweight or obese, including prevention activities, should be available in schools, the workplace and the community. In contrast, a poor socio-economic condition is associated with underweight women in Bangladesh, because individuals in such conditions cannot afford expensive items such as milk, meat, poultry, fruits and other nutritious foods. For these individuals, the focus should be on healthy diets (e.g. consumption of fruits and vegetables) that lead to optimal BMI and other health outcomes for vulnerable households.

We observed that the age and educational status of the mother, the size of the household and administrative division were significantly associated with the prevalence of DBM among mother–child pairs at the household level in Bangladesh. We found that older mothers had an increased risk of DBM compared to younger mothers. This result is consistent with several studies that suggested that the prevalence of overweight/obesity was higher in older age groups than in younger age groups(1,5). Explanation for this includes reduced activity of the mothers as they age, taking in more calories than they require, and slowing of metabolic processes as they age. It was observed that women aged 30 years or older were more likely to be overweight or obese than younger women in Bangladesh(7). Due to sedentary lifestyles and a reduction in metabolic rates, obesity tends to increase with age among women(7,10). A previous study observed that the prevalence of underweight and overweight women aged 15–49 years in Bangladesh was 22·4 % and 14·1 %, respectively. These conditions are crucial for determining the overall health condition of a child, as maternal health status plays a significant role in child health(39). Our study also demonstrated that maternal education was a significant factor for controlling the DBM. Various other studies also observed a negative association between higher education and malnourished children, as improved knowledge of healthy behaviours can help parents nurture their children(40,41). This is likely because more highly educated mothers tend to have better knowledge of child health and nutrition and can thus choose healthy foods for their household(42). A study conducted in Bangladesh suggested that secondary or higher education of mothers may have contributed to reducing the risk of DBM in the households studied(43). Another study indicated that discordant mother–child pairs were significantly less likely to occur in households in which the mother had a secondary or higher education than in those in which the mother had no formal education (34). Furthermore, knowledge of infant and young child feeding practices was also poor among uneducated mothers in Bangladesh, which emphasises the importance of maternal education for better child health, which could contribute to reducing the household-level DBM in Bangladesh(44). Various study showed that underweight is more common among less educated mothers, while the overweight is more concentrated among educated woman. This may be because higher-educated individuals often prefer desk jobs where the occupational sitting time is relatively high, which might contribute to overweight status(45,46). Therefore, target-based educational awareness programmes such as the importance of a balanced diet and sufficient nutrition should be introduced at various levels of society.

This study indicated that the size of the household and the administrative division have important implications for the DBM in Bangladesh. We found that small households were often prone to DBM, probably as due to the lack of extra members in their households, they were often unable to prepare home-cooked meals and tended to use more convenient options (processed foods) that could lead to increased weight(47) Moreover, every member of a small household always tries to feed an excessive amount of food (both home-cooked and processed foods) to the youngest member (children) to show their love and affection in the Bangladeshi context, which puts them at an even higher risk of being malnourished(48). Although this study did not attempt to explain these findings, increasing maternal and child overweight/obesity may be an important factor. Therefore, further investigation should be conducted. Regarding administrative divisions, we found that households located in the Khulna and Rangpur divisions were less likely to develop the DBM. Khulna and Rangpur are considered high-performing in various health indicators, such as literacy rates, high maternal nutrition, low mortality rate, low fertility rate, low childhood malnutrition and high socio-economic status(40). In terms of wealth index, we observed that richer and richest households were more likely to generate DBM characterised by OWM & SC/WC/UWC. Our results are similar to many previous studies which have documented a significant positive relationship between the wealth index and household-level DBM(17,18). It was observed that UWC are more prevalent among poorer households, while being overweight is more common among wealthy mothers in Bangladesh, which is also in line with other settings (45,46). It may be due to having access to Western or fast food, higher occupational sitting time, and excess energy intake, which often lead to overweight and obesity among mothers (49,50).Various studies also indicated that children from disadvantaged households in Bangladesh are often prone to being stunted, wasted and underweight, while OWC are more concentrated among the wealthiest households(1,9,40).Therefore, policy should focus the mitigation of the unequal wealth distribution for tackling the DBM issues from all strata of society. Our findings and those of other studies suggest that it is high time for policymakers and public health professionals to take the necessary steps to prevent and control the DBM among Bangladeshi women. However, it is quite challenging to implement an intervention in a country in which both undernutrition and overnutrition coexist, as an intervention to address one problem might exacerbate the other. Therefore, target-specific interventions must be formulated and implemented, and health literacy should be encouraged so that people can make the best decisions for themselves given their individual circumstances. The government should sponsor initiatives to educate and encourage affluent women: to embrace a healthy lifestyle and generate awareness of the health impact of being underweight or overweight using mass media; to refashion transport facilities, particularly in urban areas, by making footpaths; and to provide a safe environment for women and adolescent girls to perform physical activities. Physicians and community health workers also can advise their patients, especially pregnant women, so that women receive counselling about weight management before or during early pregnancy. The government should also take the initiative to restrict the production, purchase, and advertisement of junk food, as well as make fruits and vegetables accessible and affordable to people from all socio-economic groups. Furthermore, the development of comprehensive surveillance systems at the household, regional and national levels should be prioritised to tackle the DBM in Bangladesh.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the study was based on cross-sectional data, and so we were unable to establish a causal relationship. Second, in the absence of income or expenditure data, we used a household asset-based wealth index as a proxy to assess households’ economic status, and another limitation regarding this was to use the same criteria to assess wealth status in both urban and rural households. Third, due to unavailability of data, various potential confounders (such as physical activity, caregiving practices, cultural influences, postpartum-weight resolution, food taboos, and more detailed components of nutritional status, such as body composition or biochemical or metabolic status) that might affect the DBM cannot be included in the analysis. Therefore, further exploration is warranted to ascertain the contribution of these potential determinants to the development of various forms of DBM in Bangladesh. Despite such limitations, a strength of the present study was that the data were extracted from a nationally representative demographic and health survey with a large randomised sample and low percentages of missing information; thus, our findings can be considered representative of the entire country. The findings of this study will offer strong insights to policymakers and will help them set target-specific, focused public health interventions to tackle the DBM, which is in line with the goal of the latest National Food and Nutrition Security Policy in Bangladesh.

Conclusion

The current study indicates the overall prevalence of DBM was about 21 %, with a significantly higher prevalence in urban areas of Bangladesh. Higher inequalities in the DBM were observed among the pair of UWM with OWC, which indicated that poor households were more vulnerable to the DBM. In contrast, a low level of inequality of DBM was observed for OWM with SC, WC and UWC. Therefore, health policymakers, concerned authorities and various stakeholders should stress the prevalence of DBM issues and provide the necessary action to tackle this public health problem in Bangladesh.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Sharif Irfat Zabeen for her earlier comments in this research. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Authorship: Conceptualisation: A.R.S.; Methodology: A.R.S., Z.H. and A.M.; Formal Analysis: A.R.S., Z.H.; Writing – Original Draft: A.R.S.; Writing – Review & Editing: A.R.S., Z.H. and A.M.; Visualisation: A.R.S. and A.M.; Supervision: Z.H. and A.M.; Project Administration: A.R.S. and Z.H. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The study analysed a publicly available DHS data set with permission from the MEASURE DHS program office. According to the DHS, written informed consent was obtained from women enrolled in the survey according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflict of interest:

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Biswas RK, Rahman N, Khanam R et al. (2019) Double burden of underweight and overweight among women of reproductive age in Bangladesh. Public Health Nutr 22, 3163–3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nakphong MK & Beltrán-Sánchez H (2021) Socioeconomic status and the double burden of malnutrition in Cambodia between 2000 to 2014: overweight mothers and stunted children. Public Health Nutr 24, 1806–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO (2017) Double-duty actions for nutrition: policy brief. Nutrition 17(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kapoor SK & Anand K (2003) Nutritional transition: a public health challenge in developing countries. Curr Opin Neurol 74, 804–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Biswas T, Townsend N, Magalhaes RJS et al. (2019) Current progress and future directions in the double burden of malnutrition among women in South and Southeast Asian countries. Nutr Epidemiol Public Health 3, nzz026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kinyoki DK, Ross JM, Lazzar-Atwood A et al. (2020) Mapping local patterns of childhood overweight and wasting in low- and middle-income countries between 2000 and 2017. Nat Med 26, 750–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Biswas T, Uddin MJ, Al MA et al. (2017) Increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity in Bangladeshi women of reproductive age: findings from 2004 to 2014. PLoS ONE 12, e0181080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. WHO (2020) Fact Sheet: Malnutrition. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sarker AR, Sultana M, Sheikh N et al. (2019) Inequality of childhood undernutrition in Bangladesh: a decomposition approach. Int J Health Plann Manage 35, 441–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Popkin BM, Adair LS & Ng SW (2012) Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev 70, 3–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hawkes C, Ruel MT, Salm L et al. (2020) Double-duty actions: seizing programme and policy opportunities to address malnutrition in all its forms. Lancet 395, 142–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP et al. (2013) Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 382, 427–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. ENN (2018) Technical Brief on the Cost of Malnutrition. Field Exchange, p21. https://www.ennonline.net/fex/58/technicalbriefcostofmalnutrition (accessed June 2021).

- 14. NIPORT (2020) Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2017–2018. Dhaka, Bangladesh and Rockville, MD: NIPORT and ICF. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Banik S & Rahman M (2018) Prevalence of overweight and obesity in Bangladesh: a systematic review of the literature. Curr Obes Rep 7, 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marchi J, Berg M, Dencker A et al. (2015) Risks associated with obesity in pregnancy, for the mother and baby: a systematic review of reviews. Obes Rev 16, 621–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Biswas T, Townsend N, Magalhaes RJS et al. (2021) Patterns and determinants of the double burden of malnutrition at the household level in South and Southeast Asia. Eur J Clin Nutr 75, 385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Anik AI, Mosfequr Rahman M, Mostafizur Rahman M et al. (2019) Double burden of malnutrition at household level: a comparative study among Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and Myanmar. PLoS ONE 14, e0221274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O’Donnell O, van Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A et al. (2008) Analyzing Health Equity Using Household Survey Data. A Guide to Techniques and Their Implementation. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim OM (2020) The Health Challenges for the Urban Poor in Bangladesh. Dhaka: The Daily Star. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Talukder A, Mazumder S, Al-Muyeed A et al. (2016) Solid Waste Management Practice in Dhaka City Solid Waste Management Practice in Dhaka City. Proceedings of the WasteSafe 2011 – 2nd International Conference on Solid Waste Management in the Developing Countries, At Khulna, Bangladesh. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303724253_Solid_Waste_Management_Practice_in_Dhaka_City (accessed August 2021).

- 22. Harun A & Ahmed F (2013) Customer hospitality: the case of fast food industry in Bangladesh. World J Soc Sci 3, 88–104. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Banik R, Naher S, Pervez S et al. (2020) Fast food consumption and obesity among urban college going adolescents in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. Obes Med 17, 100161. [Google Scholar]

- 24. NIPORT (2015) Bangladesh Urban Health Survet-2013 Final Report. Dhaka: NIPORT. [Google Scholar]

- 25. BBS (2014) Census of Slum Areas and Floating Population (2014). Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goryakin Y, Rocco L & Suhrcke M (2017) The contribution of urbanization to non-communicable diseases: evidence from 173 countries from 1980 to 2008. Econ Hum Biol 26, 151–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mehata S, Shrestha N, Ghimire S et al. (2020) Association of altitude and urbanization with hypertension and obesity: analysis of the Nepal demographic and health survey 2016. Int Health 24, 151–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Saquib J, Saquib N, Stefanick ML et al. (2016) Sex differences in obesity, dietary habits, and physical activity among urban middle-class Bangladeshis. Int J Health Sci 10, 363–372. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Senbanjo IO, Olayiwola IO, Afolabi WA et al. (2013) Maternal and child under-nutrition in rural and urban communities of Lagos state, Nigeria: the relationship and risk factors. BMC Res Notes 6, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rahman A & Sathi NJ (2021) Sociodemographic risk factors of being underweight among ever-married Bangladeshi women of reproductive age: a multilevel analysis. Asia Pac J Public Health 33, 220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mahumud RA, Sultana M & Sarker AR (2017) Distribution and determinants of low birth weight in developing countries. J Prev Med Public Health 50, 18–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bixby H, Bentham J, Zhou B et al. (2019) Rising rural body-mass index is the main driver of the global obesity epidemic in adults. Nature 569, 260–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Balarajan Y & Villamor E (2009) Nationally representative surveys show recent increases in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in Bangladesh, Nepal, and India. J Nutr 139, 2139–2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jehn M & Brewis A (2009) Paradoxical malnutrition in mother–child pairs: untangling the phenomenon of over- and under-nutrition in underdeveloped economies. Econ Hum Biol 7, 28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. WHO (2021) Obesity and Overweight in South-East Asia. Key Facts. https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/obesity (accessed August 2021).

- 36. Haque MA, Choudhury N, Farzana FD et al. (2021) Determinants of maternal low mid-upper arm circumference and its association with child nutritional status among poor and very poor households in rural Bangladesh. Matern Child Nutr 17, e13217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Khanam M, Osuagwu UL, Sanin KI et al. (2021) Underweight, overweight and obesity among reproductive Bangladeshi women: a nationwide survey. Nutrients 13, 4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Doak CM, Adair LS, Bentley M et al. (2005) The dual burden household and the nutrition transition paradox. Int J Obes 29, 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sigdel A, Sapkota H, Thapa S et al. (2020) Maternal risk factors for underweight among children under-five in a resource limited setting: a community based case control study. PLoS ONE 15, e0233060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Khanam M, Shimul SN & Sarker AR (2019) Individual-, household-, and community- level determinants of childhood undernutrition in Bangladesh. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol 16, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Akram R, Sultana M, Ali N et al. (2018) Prevalence and determinants of stunting among preschool children and its urban–rural disparities in Bangladesh. Food Nutr Bull 39, 521–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Semba RD, De PS, Sun K et al. (2008) Effect of parental formal education on risk of child stunting in Indonesia and Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 371, 322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hasan MT, Soares Magalhaes RJ, Williams GM et al. (2015) The role of maternal education in the 15-year trajectory of malnutrition in children under 5 years of age in Bangladesh. Matern Child Nutr 12, 929–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sheikh N, Akram R, Ali N et al. (2019) Infant and young child feeding practice, dietary diversity, associated predictors, and child health outcomes in Bangladesh. J Child Health Care 110, 851–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hossain S, Khudri MM & Banik R (2021) Regional education and wealth-related inequalities in malnutrition among women in Bangladesh. Public Health Nutr 25, 1639–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gewa CA, Leslie TF & Pawloski LR (2013) Geographic distribution and socio-economic determinants of women’s nutritional status in Mali households. Public Health Nutr 16, 1575–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Baker P & Friel S (2014) Processed foods and the nutrition transition: evidence from Asia. Obes Rev 15, 564–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ravaoarisoa L, Randriamanantsaina L, Rakotonirina J et al. (2018) Socioeconomic determinants of malnutrition among mothers in the Amoron’i Mania region of Madagascar: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr 4, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Das S, Fahim SM, Islam MS et al. (2019) Prevalence and sociodemographic determinants of household-level double burden of malnutrition in Bangladesh. Public Health Nutr 22, 1425–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Leroy JL, Habicht JP, de Cossío TG et al. (2014) Maternal education mitigates the negative effects of higher income on the double burden of child stunting and maternal overweight in rural Mexico. J Nutr 144, 765–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]