Abstract

Purpose:

Patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) have poor outcomes and require new therapies. In AML, autocrine production of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) drives MET signaling that promotes myeloblast growth and survival, making MET an attractive therapeutic target. MET inhibition exhibits activity in AML preclinical studies, but HGF upregulation by the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) pathway is a common mechanism of resistance.

Patients and Methods:

We performed preclinical studies followed by a phase 1 trial to investigate the safety and biological activity of the MET inhibitor merestinib in combination with the FGFR inhibitor LY2874455 for patients with R/R AML. Study Cohort 1 underwent a safety lead-in to determine a tolerable dose of single-agent merestinib. In Cohort 2, dose-escalation of merestinib and LY2874455 was performed following a 3+3 design. Correlative studies were conducted.

Results:

The primary DLT observed for merestinib alone or with LY2874455 was reversible grade 3 transaminase elevation, occurring in two of 16 patients. Eight patients had stable disease and one achieved complete remission (CR) without measurable residual disease. While the maximum tolerated dose of combination therapy could not be determined due to drug supply discontinuation, single-agent merestinib administered at 80mg daily was safe and biologically active. Correlative studies showed therapeutic plasma levels of merestinib, on-target attenuation of MET signaling in leukemic blood, and increased HGF expression in bone marrow aspirate samples of refractory disease.

Conclusions:

We provide prospective, preliminary evidence that MET and FGFR are biologically active and safely targetable pathways in AML.

Introduction

Patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) face a dim prognosis. Historically, the 5-year overall survival (OS) for relapsed AML is 10% with a median OS of 0.5 years (1). Recently approved targeted therapies have improved outcomes, but only modestly, and their usage is limited to patient subsets with the corresponding molecular alteration (2–5). There remains a need for effective therapies for R/R AML.

Mesenchymal Epithelial Transition (MET) is an oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) that is an attractive therapeutic target in multiple human cancers. By binding hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), its only known ligand, MET activates signaling cascades such as MAPK, STAT, and AKT/PI3K and thereby promotes cell survival, proliferation, and invasion (6). In approximately 40% of AML cases, aberrant MET signaling is driven by autocrine production of HGF (7), with increased signaling at the time of disease relapse (8). MET inhibitors induce leukemic cell death in vitro, but resistance arises quickly from compensatory upregulation of HGF through other signaling pathways such as the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) pathway (7,9). Concurrent inhibition of MET and FGFR successfully leads to sustained cancer cell killing in murine xenograft models (7), lending preclinical rationale for this combination therapy in AML patients.

Merestinib is a potent oral inhibitor of MET with additional activity against other RTKs including RON, AXL, ROS1, NTRK, and FLT3 (10,11). A first-in-human phase 1 study of patients with advanced solid tumors demonstrated merestinib’s tolerable safety profile and potential anticancer activity, supporting a maximum tolerated dose/recommended phase 2 dose (MTD/RP2D) of 120mg once daily (12). This was followed by additional studies in biliary and colorectal cancer (13,14). LY2874455 is an oral pan inhibitor of all FGFR isoforms with demonstrated safety in a phase 1 study of advanced solid tumors and recommended phase 2 dose of 16 mg twice daily (15). The primary adverse effects of merestinib and LY2874455 were transient and reversible hepatic injury and hyperphosphatemia, respectively. Neither of these investigational agents have been assessed in AML as monotherapy or in combination.

We conducted preclinical studies followed by a phase 1 trial to investigate the safety and activity of merestinib plus LY2874455 in patients with R/R AML. The combination of merestinib and LY2874455 represents a rational therapeutic approach not previously assessed in patients with AML. We hypothesized that the HGF/MET signaling axis is a safely targetable pathway using this novel-novel drug combination.

Materials and Methods

Patient eligibility

Patients enrolled were aged ≥18 years with R/R AML. Relapsed AML was defined according to European LeukemiaNet criteria (≥5% blasts marrow or emergence of peripheral blasts)(16) recurring after prior allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HCT), ≥1 regimen of standard cytotoxic chemotherapy, or ≥2 cycles of any hypomethylating agent (HMA)-based therapy. Two cycles of induction therapy as part of a standard anthracycline-based regimen (e.g., 7+3 followed by 5+2) was considered a single induction regimen. Refractory AML was defined as leukemia persisting following ≥2 prior induction regimens or ≥2 cycles of any HMA-based therapy.

Eligible patients were required to have Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of ≤2 with adequate baseline renal (serum creatinine ≤2.0 × upper limit of normal [ULN]) and hepatic function (direct bilirubin ≤1.5 × ULN; AST/ALT ≤2.5 × ULN or ≤5 × ULN if work-up ruled out a secondary etiology and the elevation was plausibly leukemia-related). Patients must have been ineligible for, or declined, intensive therapies, including HCT. There was otherwise no limit to the number of prior therapies received, including prior HCT, provided any bone marrow transplant occurred >100 days prior to the first dose of treatment on study.

Study design

This single-center, non-randomized, open-label phase I study (NCT03125239) was conducted to determine the safety profile of merestinib plus the pan-FGFR inhibitor LY2874455 in patients with R/R AML. Patients were enrolled in this study from November 2017 to January 2020. The primary objective was to determine the MTD/RP2D of combination therapy. Secondary objectives were to assess the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and preliminary efficacy of combination therapy. This study was conducted at a single site, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Patients provided written informed consent and the trial was conducted in compliance with the local institutional review board and in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Three cohorts were planned for the clinical study (Figure S1): Cohort 1) to undergo safety lead-in of single-agent merestinib for 28 days; Cohort 2) to undergo dose-escalation with combination merestinib and LY2874455; and Cohort 3) to undergo dose-expansion with combination therapy. Cohort 1 enrolled six patients with the objective of determining a tolerable dose of merestinib to combine with LY2874455 for Cohort 2. Safety of single-agent merestinib was demonstrated if ≤1 of six patients developed significant toxicity, defined as any grade ≥3 non-hematologic events not clearly related to active leukemia. For Cohort 2, dose-escalation involved 28-day cycles of combination therapy (with the first cycle preceded by a 7-day lead-in with single-agent merestinib for safety and pharmacodynamic studies) and MTD/RP2D was determined following a standard 3+3 design. Finally, an expansion cohort (n=7), Cohort 3, was planned to further explore adverse events and treatment efficacy.

For patients in Cohort 1 without evidence of toxicity from single-agent merestinib after 28-days and with evidence of persistent disease, adding LY2874455 to merestinib could be considered with additional DLT evaluation during the first month of combination therapy. For Cohort 1 patients who achieve complete remission (with or without hematologic recovery), merestinib monotherapy could be continued with LY2874455 added later at the time of disease progression, also with additional DLT evaluation during the first month of combination therapy. Patients from Cohort 1 who added on LY2874455 were not included in the dose-escalation assessment of the combination therapy for Cohort 2. However, all enrolled patients were evaluable for adverse events and disease response.

Treatment

For Cohort 1, merestinib was administered at 80mg/day by mouth for 28-day cycles. Any patient intolerant of merestinib at this dose was dose-reduced to 40mg/day. Assuming 80mg/day would be a tolerable dose of merestinib, Cohort 2 underwent exploration of three dose levels of merestinib and LY2874455—Dose-level 0 (DL 0; starting dose level): 80mg merestinib/day for 28 days + 10mg LY2874455 twice a day for 21 days, Dose-level 1 (DL 1): 120mg merestinib/day for 28 days + 10mg LY2874455 twice a day for 21 days, and Dose-level 2 (DL 2): 120mg merestinib/day for 28 days + 12mg mg LY2874455 twice a day for 28 days. An expansion Cohort 3 was planned to receive the MTD/RP2D of merestinib and LY2874455 determined in Cohort 2. Hydroxyurea was allowed for Cohort 1 and during the first cycle of combination therapy for Cohort 2 at the discretion of the treating provider.

Of note, for patients in Cohort 1 who added on LY2874455 due to persistent or recurrent disease, the dose of LY2874455 was 10mg twice a day to match the DL 0 dose of LY2874455. Additionally, for Cohort 2, the DL 0 dose of 80mg/day merestinib was deliberately chosen to be lower than the merestinib MTD/RP2D of 120mg reported in solid tumors (12), given the potential for overlapping toxicities from our addition of LY2874455 to merestinib.

Safety assessment

Adverse events were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0). For Cohort 1, the dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) window for determining the tolerable dose of merestinib encompassed the entire cycle (28 days); during dose-escalation for Cohort 2, the DLT window encompassed the first cycle of combination therapy (28 days; Figure S1). A DLT was defined as any grade ≥3 non-hematologic event that was not clearly related to active leukemia except for 1) grade 3 electrolyte abnormalities that resolved to grade ≤1 within 14 days, 2) grade 3 fatigue or constipation, or 3) grade 3 nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea that did not require a prolonged hospitalization or feeding tube. Grade ≥4 hematologic toxicity was considered a DLT if the absolute neutrophil count did not recover to ≥500 × 109/L or platelet count to ≥25,000 × 109/L by the end of the DLT window and in the absence of underlying disease.

Clinical response and efficacy assessment

A bone marrow biopsy to assess treatment response was performed after one cycle for Cohort 1, and after cycles 1, 2, and every other cycle thereafter for Cohort 2. Bone marrow biopsies were repeated sooner if there was concern for disease progression. Response categorization was based on the 2017 European LeukemiaNet (ELN) criteria (16). Patients were allowed to remain on study if they had at least stable disease. For patients achieving complete remission, measurable residual disease assessment was performed with multiparametric flow cytometry (MFC) with a lower level of detection of less than 10−3 (Hematologics, Seattle, WA).

Preclinical and correlative studies

In vitro studies were conducted using the leukemic cell lines HEL (RRID CVCL_0001), KG1a (RRID CVCL_1824), MOLM13 (RRID CVCL_2119), MOLM14 (RRID CVCL_7916), and MV411 (RRID CVCL_0064). All cell lines were obtained from Dr. James Griffin, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Dr. Daniel G. Tenen, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and were authenticated by short tandem repeat DNA profiling and routinely tested for the presence of Mycoplasma by PCR. Merestinib and LY2874455 were supplied by Eli Lilly and Company. Cell line viability studies involved 72 hours of in vitro incubation with merestinib and/or LY2874455, followed by viability assessment using CellTiter-Glo (Promega #PAG7572). Potential synergy of merestinib and LY2874455 was analyzed using SynergyFinder (syngergyfinder.fimm.fi). For immunoblot, flow cytometry, and gene expression studies, AML cell lines were incubated with merestinib and/or LY2874455 for 1 hour. Subsequently, protein lysates were generated and immunoblots performed with antibodies to tubulin (Sigma, #T5168), pSTAT3 (Y705, Cell Signaling, #9131), pSTAT3 (S727, Cell Signaling, #9134), total STAT3 (124H6, Cell Signaling, #9139), pSTAT5 (Y694, Cell Signaling, #9351), pSTAT5 (C11C5, Cell Signaling, #9359), and total STAT5 (D206Y, Cell Signaling, #94205). For phospho-flow cytometry, cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated mouse anti-STAT5 (pY694, BD Biosciences, #612599), PE-conjugated mouse anti-STAT3 (pY705, BD Biosciences, #612569), Alexa 647-conjugated mouse anti-pFGF receptor (Y653/654) (55H2, Cell Signaling, #41286BC Lot: 4) and PE-conjugated rabbit anti-pMET (Y1234/1235) (D26, Cell Signaling, #12468S). Isotype control antibodies conjugated to the same fluorophore were used to set the gate for negative cellular staining. For mRNA analyses, cellular RNA was isolated using RNeasy Mini kits (Qiagen) and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) was performed on a Quantstudio 6 Flex RealTime PCR system (Applied Biosystems).

Pharmacokinetic analysis of merestinib, its metabolites (LSN2800870 and LSN2887652), and LY2874455 was performed by Labcorp (Burlington, NC). Pharmacodynamic analyses were performed utilizing patient peripheral leukemic blood samples collected at baseline (pre-treatment) and during study treatment. Pre-treatment leukemic blasts were Ficoll-separated from patient peripheral blood and prepared for phospho-flow cytometry for pMET, pFGFR, pSTAT3, and pSTAT5 using the antibodies listed above. Additionally, patient pre-treatment myeloblasts were incubated ex vivo with merestinib and/or LY2874455 for 1 hour followed by phospho-flow analysis as described above for leukemic cell lines. Lastly, gene expression analysis with patient bone marrow samples was performed using the Tumor Signaling 360 panel from NanoString Technologies (Seattle, WA). The panel is composed of 780 genes involved in tumor growth and immune response.

Statistical analysis

The primary objective was to determine the MTD/RP2D of merestinib in combination with LY287445 using the 3+3 design. The sample size was calculated to ensure a decreasing likelihood of dose escalation if the rate of DLT exceeds 30%. Secondary objectives of this study included determining the preliminary treatment outcomes of this combination for patients with R/R AML. Patient survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) for the overall population and based on treatment received were determined according to the method of Kaplan and Meier. Time-to-event was initiated at the time of study registration. Descriptive statistics are reported for all major endpoints along with their 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Preclinical and correlative studies were primarily descriptive and exploratory, and only p values comparing geometric means of plasma drug concentrations were calculated during pharmacokinetic analysis. Potential in vitro synergy between merestinib and LY2874455 was evaluated using the Zero interaction potency (ZIP) model (17).

Data availability

The data generated in this study are not publicly available due to information that could compromise patient privacy or consent but are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Results

Preclinical studies

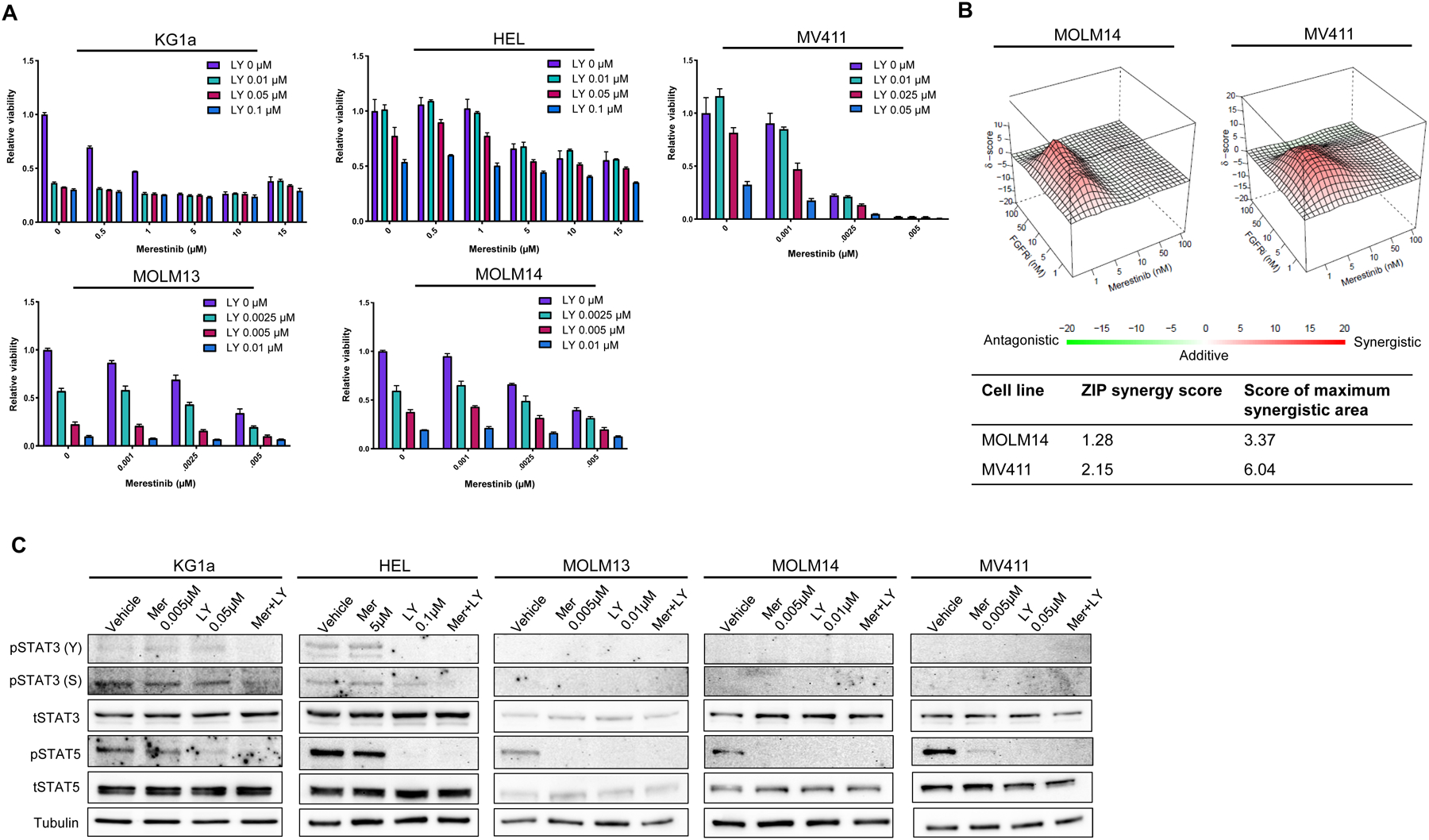

We first performed studies to determine the cytotoxic effects of merestinib and LY2874455 in vitro. We incubated five AML cell lines (KG1a, HEL, MOLM13, MOLM14, MV411) with merestinib with or without LY2874455 across a range of concentrations and observed varying degrees of dose-dependent cell killing for each drug in combination (Figure 1A). Moreover, the cytotoxic effects of merestinib and LY2874455 displayed additive-to-synergistic activity over a range of concentrations in different cell lines (Figure 1B).

Figure 1: Merestinib and LY2874455 inhibit MET signaling and induce cytotoxicity.

A, Combination therapy with merestinib + LY2874455 induce dose-responsive cytotoxicity of AML cell lines in vitro. B, ZIP synergy analysis indicates additive-to-synergistic activity of merestinib + LY2874455. C, Immunoblots of treated AML cell lines demonstrate decreased levels of phosphorylated STAT3 and STAT5 with drug treatment. Abbreviations: Mer = Meristinib; LY = LY2874455

Next, to understand the mechanistic effects of these drugs and to identify potential pharmacodynamic biomarkers of their efficacy in AML patients, we assessed whether treatment with merestinib and LY2874455 inhibited signaling pathways downstream of MET. We focused primarily on STAT3 and STAT5, two transcription factors frequently activated inappropriately in AML cells, which drive the expression of genes regulating survival, proliferation, and pluripotency (18). After one hour of incubation with merestinib and/or LY2874455, prominent decreases were noted in the activating tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5 in all five of the AML cell lines and of STAT3 in the two lines with constitutive phosphorylation of this protein (KG1a and HEL; Figure 1C). Furthermore, the combination of merestinib and LY2874455 led to a decrease in the phosphorylation of STAT3 on ser727, a phosphorylation event known to promote non-canonical effects of STAT3, including pro-survival effects in the mitochondria (19). To determine whether these on-target effects of merestinib and LY2874455 could be detected using a technique that allows gating on myeloblasts, we performed parallel experiments using phospho-flow cytometry. These showed analogous changes in the tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 and STAT5 (Figure S2A). To further evaluate whether these changes in STAT phosphorylation affect their transcriptional role, we examined expression of cytokine-inducible SH2 protein 1 (CISH), a gene highly responsive to STAT5 activity, by RT-PCR. Reflecting an on-target effect, CISH expression closely paralleled effects on STAT5 phosphorylation (Figure S2B). Taken together, these findings indicate that merestinib and LY2874455 decreased viable cell number and inhibited key oncogenic STAT transcription factors in AML cell lines in vitro.

Patient characteristics

Motivated by preclinical studies, we devised a phase 1 trial to investigate the safety and activity of merestinib in combination with LY2874455 for patients with R/R AML. A total of 16 patients were enrolled and received treatment on study (Table 1). The median age was 70 (range 28–82), 44% were male, and 81% were white. The representativeness of study participants is shown in Table S1. Intermediate or adverse risk by ELN criteria comprised 81% of patients. Prior therapies included intensive chemotherapy (50%), venetoclax plus HMA (37.5%), other venetoclax-based combination therapy (12.5%), HMA monotherapy (37.5%), and prior HCT (37.5%). Baseline mutational profiles for each patient are shown in Figure S3. Overall, 56.3% had adverse risk mutations, including mutated ASXL1 (25%), RUNX1 (25%), TP53 (18.8%), and FLT3-ITD (6.3%).

Table 1:

Baseline clinical characteristics

| PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS | PATIENTS (N=16) |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 70 (28–82) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 7 (44%) |

| Female | 9 (56%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White | 13 (81%) |

| Black | 1 (6.3%) |

| Hispanic | 1 (6.3%) |

| Asian | 1 (6.3%) |

| ECOG performance status, median (range) | 1 (0–2) |

| DISEASE CHARACTERISTICS AT TREATMENT START | |

| AML ontogeny, n (%) | |

| Relapsed | 11 (69%) |

| Refractory | 5 (31%) |

| ELN risk, n (%) | |

| Favorable | 3 (18.8%) |

| Intermediate | 1 (6.3%) |

| Adverse | 12 (75%) |

| Monosomal karyotype | 5 (31%) |

| Complex karyotype | 7 (47%) |

| # Prior therapies, median (range) | 2.5 (1–6) |

| # Days since last prior therapy, median (range) | 37 (7–78) |

| Prior therapies, n (%) | |

| Intensive chemotherapy | 8 (50%) |

| Ven+HMA | 6 (37.5%) |

| Ven+other (not HMA) | 2 (12.5%) |

| HMA+other (not Ven) | 5 (31.3%) |

| HMA monotherapy | 6 (37.5%) |

| FLT3 TKI monotherapy | 2 (12.5%) |

| GO monotherapy | 1 (6.25%) |

| HCT | 6 (37.5%) |

| Other/investigational agent | 5 (31.25%) |

| Adverse risk mutations, n (%) | |

| ASXL1 | 4 (25%) |

| RUNX1 | 4 (25%) |

| TP53 | 3 (18.8%) |

| FLT3-ITD | 1 (6.3%) |

| Laboratory values | |

| WBC (109/L), median (range) | 2.59 (0.82–63.23) |

| ANC (109/L), median (range) | 0.33 (0–14.9) |

| Hgb (g/dL), median (range) | 8.9 (7.1–12.7) |

| Platelet (109/L), median (range) | 18 (7–208) |

| Peripheral blast %, median (range) | 26.5% (0–0.96) |

| Absolute peripheral blast count (109/L), median (range) | 0.47 (0–60.7) |

| Bone marrow blast %, median (range) | 90% (10–99) |

| # Receiving hydroxyurea, n (%) | 7 (43.8%) |

Abbreviations: AML = acute myeloid leukemia; ECOG = European Cooperative Oncology Group; ELN = European LeukemiaNet; Ven = venetoclax; HMA = hypomethylating agent; GO = gemtuzumab ozogamicin; HCT = hematopoietic cell transplantation; WBC = white blood cell; ANC = absolute neutrophil count; Hgb = hemoglobin

Safety and tolerability

A total of seven patients (subjects P1–P7) were enrolled in Cohort 1 and received single-agent merestinib at 80mg/day. One DLT occurred in the first three subjects involving reversible grade 3 transaminase elevations attributed to merestinib that resolved within four days with dose hold and modification per protocol. Three additional patients were enrolled, one of whom experienced rapid disease progression, discontinued the study prior to completing a cycle of therapy, and was thus replaced by a seventh subject. No additional patients experienced a DLT. Therefore, 80mg/day was established as the starting merestinib dose for dose-escalation for Cohort 2.

A total of nine patients (subjects P8–16) were enrolled in Cohort 2 at Dose Level 0 (DL 0), consisting of merestinib dosed 80mg/day for days 1–28 and LY2874455 dosed 10mg twice a day for days 1–21. Four patients experienced rapid disease progression prior to completing the first cycle of combination therapy, and thus only five of nine patients were evaluable for DLTs. Among all nine patients, only one DLT occurred involving transient grade 3 transaminase elevation that resolved within seven days with dose hold per protocol. Five of the seven patients in Cohort 1 eventually added on LY2874455 for persistent or recurrent disease, without additional DLTs seen. The study was abruptly terminated in July 2020 based on Eli Lilly’s decision after a negative phase 2 study of merestinib for advanced biliary tract cancer (14). Thus, our study was unable to determine the MTD/RP2D of combination merestinib and LY2874455 in AML and there was no enrollment to Cohort 3 (expansion cohort).

Table S2 lists any grade treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs) observed in ≥2 patients in our entire cohort (n=16). The most common grade ≥3 TEAEs (Table 2) were febrile neutropenia (37.5%%), ALT increase (25%), AST increase (18.8%), and hypophosphatemia (18.8%). The primary reasons for treatment discontinuation (Table S3) were complications from disease progression (87.5%) or patient preference (12.5%). No patient discontinued treatment due to dose-limiting toxicity.

Table 2:

Grade ≥3 adverse events experienced in ≥2 patients.

| TOXICITY | GRADE 3 | GRADE 4 | GRADE 5 | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Febrile neutropenia | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| ALT increased | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| AST increased | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Hypophosphatemia | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Fatigue | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Infections | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| QT corrected interval prolonged | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| White blood cell decreased | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

Clinical response and survival

All 16 patients enrolled were eligible for response evaluation (Table 3). Eleven patients had bone marrow evaluations performed after completing at least one cycle of therapy and were evaluable for response. Of these 11 patients, a best response of stable disease (SD) was noted in most patients (n=8, 72.7%), for whom the median duration of SD was 40 days (range 10–468). One patient (subject P9) with 468 days of stable disease received supportive care alone following completion of this study. Morphologic leukemia free state (MLFS) and complete remission (CR) with negative MRD were additionally noted in two patients (respectively subjects P6 and P5). MRD testing by MFC was not performed for the patient with MLFS, but cytogenetics detected one of two metaphases that contained aberrations previously demonstrated in the patient.

Table 3:

Best overall response

| BEST OBJECTIVE RESPONSE | PATIENTS (N=16) |

|---|---|

| Complete remission | 1 (6.3%) |

| Morphologic leukemia free state | 1 (6.3%) |

| Stable disease | 8 (50%) |

| Progressive disease | 1 (6.3%) |

| Not evaluable | 5 (31.3%) |

For the sole subject (P5) who attained a CR, remission was documented during merestinib monotherapy in Cohort 1. In detail, CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi) was seen after cycle one of merestinib, MRD-negative CR after cycle two, then relapsed disease after four total cycles of single-agent merestinib, at which point LY2874455 was added as permitted per protocol. The subject unfortunately developed disease progression despite two additional cycles of combination therapy. Prior to treatment, subject P5 exhibited mutations in DNMT3A (variant allele fraction [VAF] 26.0%), TET2 (30.9%), NPM1 (27.72%), and FLT3-TKD (34.6%). At the time of relapse, subject P5 was found to have the same mutations in DNMT3A (17.3%), TET2 (16.7%), and NPM1 (15.6%), and a new mutation in CEBPA (6.5%). However, the previously seen FLT3-TKD mutation was absent.

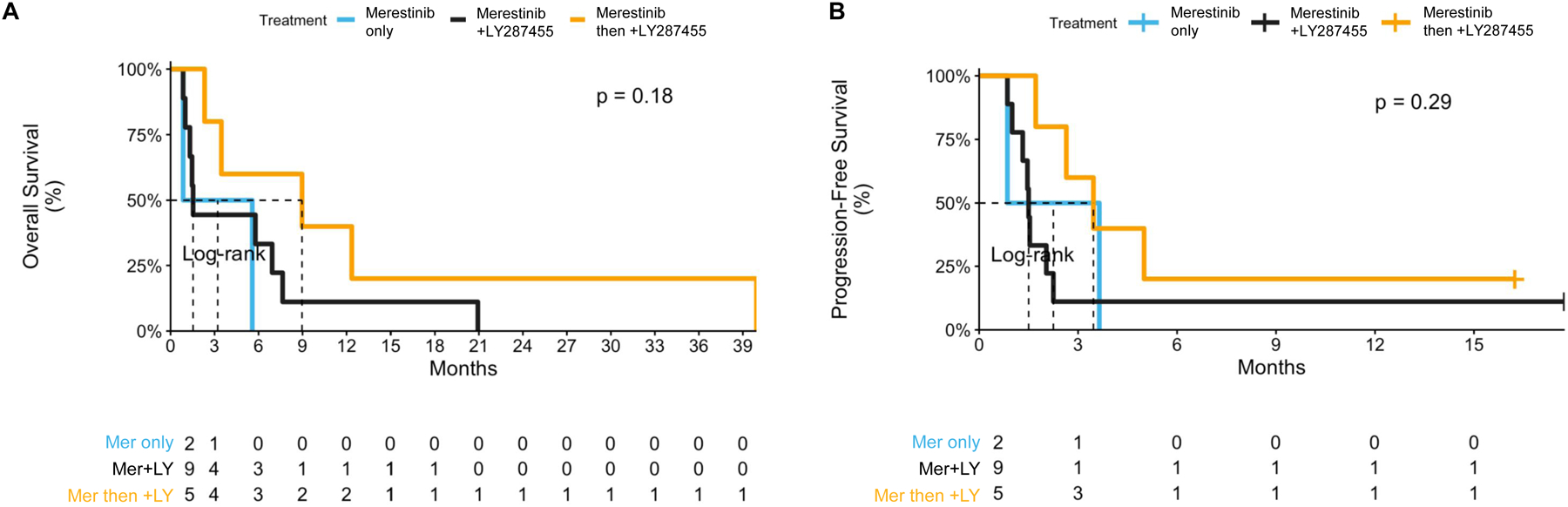

With a median follow-up of 4.5 months (range 0.9–39.9), the median PFS and OS for the entire cohort were 1.9 months (95% CI: 1.5–5.0) and 4.5 months (95% CI: 1.5–12.4), respectively. The probability of survival at 1-year for the entire cohort was 12.5% (95% CI: 3.4–45.7). Adjusting outcomes based on treatment received, the PFS and OS were 2.3 months (95% CI: 0.9-N/A) and 3.2 months (95% CI: 0.9-N/A) for patients who received merestinib monotherapy, 1.5 months (95% CI: 1.3-N/A) and 1.5 months (95% CI: 1.3-N/A) for patients who received upfront combination therapy of merestinib plus LY2874455, and 3.5 months (95% CI: 2.6-N/A) and 9.0 months (3.5-N/A) for patients receiving merestinib monotherapy and later added on LY2874455. No patient underwent subsequent hematopoietic cell transplantation. Survival curves adjusted for the treatment received (Figure 2) and for the overall cohort (Figure S4) are shown. The 30- and 60-day mortality rate for the overall cohort was 19% and 38%, respectively. For all six patients who died within 60 days of treatment, the cause of death was AML or complications arising from AML (Table S3). No patients remain alive at the time of this report.

Figure 2: Survival outcomes based on treatment received.

A, Progression-free survival. B, Overall survival. Abbreviations: Mer = merestinib; LY = LY2874455.

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis

We confirmed detectable levels of merestinib, its metabolites (LSN2800870 and LSN2887652), and LY2874455 in peripheral blood samples from treated study subjects (Figure S5). Plasma concentrations were measured prior to study start and on days 1, 8, and/or 21 of cycle 1 of therapy. For subjects in Cohort 2, sample collection started at the time combination therapy began (i.e., after the 7-day lead-in of merestinib monotherapy, see Figure S1). Patients receiving combination therapy exhibited a higher mean plasma level of merestinib prior to their dose on day 8 compared to patients receiving single-agent merestinib (p<0.05, Figure S5A). Two hours after dosing on day 1, the mean merestinib concentration was 279 ng/mL (95% CI: 189.3–412.2) for patients receiving combination therapy and 67 ng/mL (95% CI: 7.8–577.2) for patients receiving single-agent merestinib.

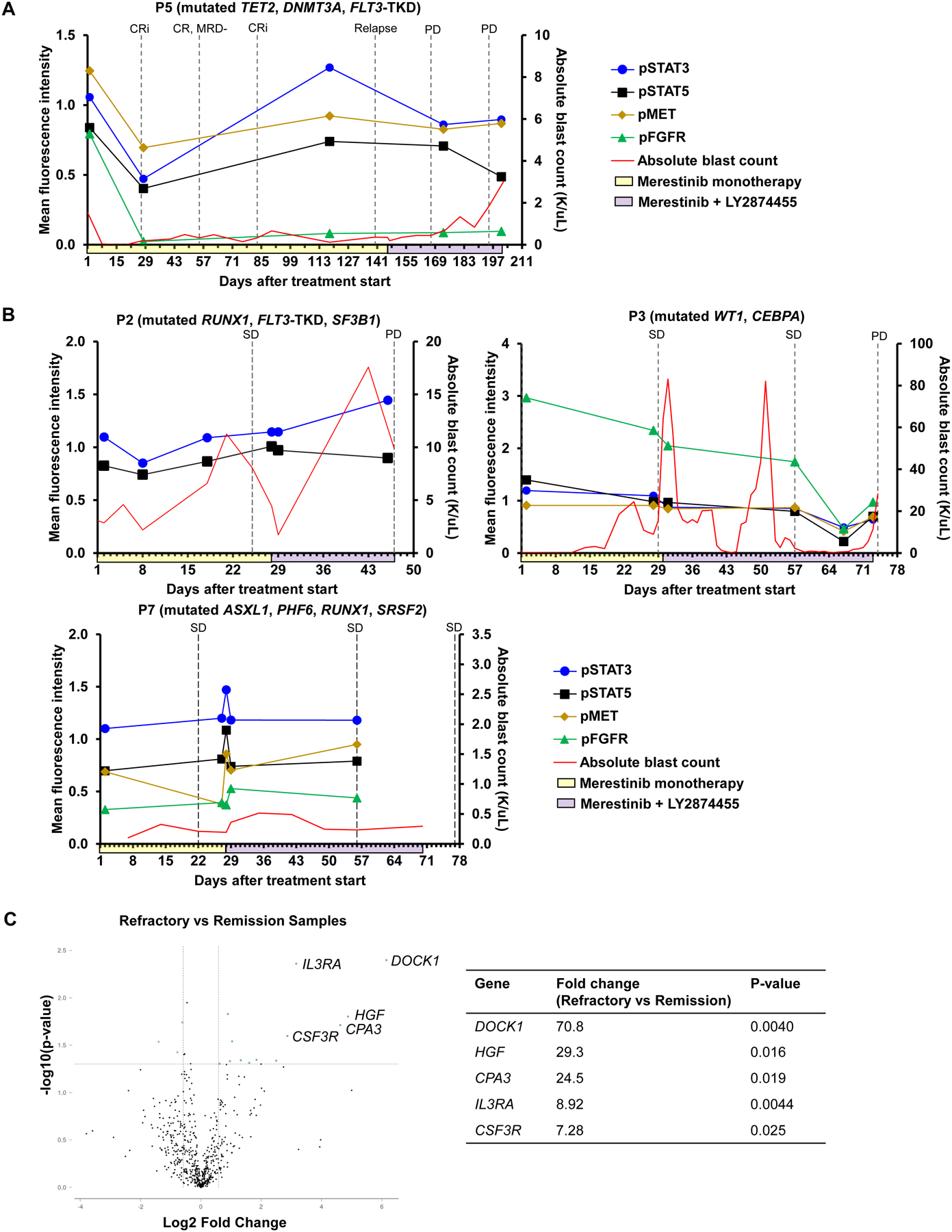

Next, we assessed for attenuation of MET signaling in subjects with paired leukemic blood samples before and during treatment and asked whether temporal dynamics in MET signaling were associated with clinical response; four representative subjects are shown (Figure 3). At the time subject P5 achieved CR on merestinib monotherapy, decreased levels of pMET, pFGFR, pSTAT3, and pSTAT5 were noted relative to pre-treatment samples, and levels subsequently rose at the time of disease relapse (Figure 3A). Subject P3 was the only subject tested found to have increased pFGFR levels during the lead-in phase with merestinib monotherapy, mirroring the compensatory upregulation of FGFR activity following MET inhibition described previously in vitro (7). Phospho-protein levels declined for subject P3 but later rose when the subject developed progressive disease. Phospho-protein levels were overall stable or increasing in subjects with stable (P7) or progressive (P2) disease, respectively (Figure 3B).

Figure 3: Pharmacodynamic analysis of merestinib and LY2874455.

On-treatment myeloblasts were isolated and the relative phosphorylation of MET and downstream targets was analyzed for subjects P2, P3, P5, and P7, normalized to baseline phosphorylation levels in pre-treatment samples. A, Subject P5, who achieved a best response of MRD-negative CR. B, Subjects P2, P3, and P7, who did not achieve CR. Yellow shading along the x-axis denotes period of merestinib monotherapy. Purple shading along the x-axis denotes period of merestinib + LY2874455 combination therapy. Dashed vertical lines denote timepoints of response assessment: CR = complete remission, CRi = CR with incomplete hematologic recovery, SD = stable disease, PD = progressive disease. C, Volcano plot depicting genes more enriched in samples of refractory disease (n = 6) vs samples during disease remission (n = 2). Samples of refractory disease were collected from subject P5 during merestinib mono- and combination therapy, P7 during merestinib mono- and combination therapy, P9 during merestinib monotherapy, and P10 during combination therapy. Samples of disease remission were collected from subject P5 following cycle 1 and cycle 2 of merestinib monotherapy.

The on-target effect of merestinib and LY2874455 prompted us to assess whether pre-treatment leukemic blasts could be studied ex vivo to predict clinical responses and serve as a biomarker to guide patient selection for this therapy. Pre-treatment leukemic blasts were incubated for one hour with merestinib and/or LY2874455 ex vivo and then prepared for phospho-flow cytometry (Figure S6). Analysis showed consistent, albeit modest reduction in levels of phosphorylated STAT3 and STAT5. Of interest, pre-treatment myeloblasts from subject P5 who achieved remission with single-agent merestinib did not exhibit greater pSTAT3 and pSTAT5 inhibition compared to other subjects.

Finally, we utilized the NanoString Tumor Signaling 360 panel to assess the differential expression of genes involved in MET signaling. Unbiased exploratory analysis identified a 29-fold higher expression of HGF in samples of refractory disease (n=6 total, collected from subject P5 during merestinib mono- and combination therapy, P7 during merestinib mono- and combination therapy, P9 during merestinib monotherapy, and P10 during combination therapy) compared to samples obtained during remission (n=2, available only from subject P5 and collected following cycle 1 and cycle 2 of merestinib monotherapy; Figure 3C). DOCK1, which encodes a protein that complexes with MET to promote cell metastasis, was the most differentially expressed at a level 70-fold higher in refractory samples than samples obtained during remission. CSF3R and IL3RA, which are involved upstream of STAT signaling, were also enriched in samples of refractory disease. Separately, we queried changes in the expression of genes involved in FLT3 signaling in subject P5, who exhibited loss of FLT3-TKD at the time of disease relapse. Compared to subject P5’s pre-treatment samples, samples of relapsed disease for P5 showed a 1.57-fold-decrease in expression of PIK3R4 (p=0.01684).

Discussion

New therapies are still needed for patients with relapsed/refractory AML. The receptor tyrosine kinase MET is a promising therapeutic target given its role in triggering multiple downstream pathways involved in cancer cell growth, survival and metastases. Preclinical studies suggest aberrant autocrine MET signaling occurs in approximately 40% of AML cases, with compensatory FGFR-driven overproduction of the MET ligand HGF being a major mechanism of treatment resistance (7,8). We present results from our Phase 1 study demonstrating the preliminary safety and feasibility of targeting the HGF/MET axis using the rational combination of merestinib and the FGFR inhibitor LY2874455.

The primary DLT observed for merestinib alone or in combination with LY2874455 was grade 3 transaminase elevation, which was expected and reversible with dose hold and modification. The same DLT was reported in an earlier Phase 1 trial of merestinib for advanced solid tumors (12). For single-agent merestinib, we found a dose of 80mg/day for 28 days to be safe, and therefore dose-escalation of combination therapy commenced with merestinib dosed 80mg/day for 28 days combined with LY2874455 dosed 10mg twice a day for 21 days. Because our study was terminated early, the MTD/RP2D of combination therapy could not be determined. Grade 3 or higher adverse events were similar for merestinib alone or in combination with LY2874455. These included febrile neutropenia and infections, which have been previously reported (14). Overall, merestinib and LY2874455 appeared to be tolerable and incurred no unexpected toxicities in our AML patient cohort.

Therapeutic plasma levels of merestinib and LY2874455 were achieved in our study subjects. Patients who received combination therapy (merestinib 80mg/day, LY2874455 10mg twice a day) achieved a mean merestinib concentration of 279 ng/mL 2 hours after dosing on day 1, comparable to the mean Cmax of 264 ng/mL reported with the same merestinib dose in a prior pharmacokinetic study (12). In contrast, subjects who received single-agent merestinib achieved a lower mean concentration of 67 ng/mL, although the associated standard error reflects marked variability at this timepoint. Notably, on day 8, merestinib drug levels were higher prior to dosing with combination therapy than single-agent merestinib, suggesting more sustained drug levels with combination therapy (Figure S5A). We hypothesize that this difference is due to the 7-day lead-in of merestinib that preceded the start of combination therapy (i.e. Days −6 to 0 for Cohort 2, see Figure S1), although whether the addition of LY2874455 also affected merestinib pharmacokinetics requires further investigation.

Of interest, merestinib appeared to successfully modulate MET signaling in our study. Subject P5 achieved complete remission while receiving merestinib monotherapy, during which serial bone marrow samples showed decreased levels of pMET and its downstream targets pSTAT3 and pSTAT5, reflecting merestinib’s on-target activity in vivo. In contrast, no collective decrease in pMET, pSTAT3, and pSTAT5 was observed in subjects who failed to achieve remission. Of note, merestinib also inhibits other RTKs such as FLT3 and Mnk (10,20), which may have contributed to subject P5’s favorable response. Subject P5 had a FLT3-TKD mutation at diagnosis that was no longer present after merestinib monotherapy and did not recur at disease relapse, suggesting successful eradication of this clone.

Additionally, our correlative studies corroborate preclinical reports that compensatory HGF upregulation is a major mechanism of resistance to MET inhibition in AML. Our gene expression analysis revealed a 29-fold higher expression of HGF in bone marrow samples obtained at the time of refractory disease compared to samples obtained during disease remission. However, this finding will require validation at the protein level in future studies. Moreover, our analyzed sample size was small, and the degree to which HGF upregulation was mediated by FGFR activation remains unclear given changes in pFGFR levels varied among patients in our cohort. pFGFR levels increased in subject P3 following merestinib monotherapy (as in vitro studies would predict) and declined following addition of LY2874455, whereas pFGFR levels declined in subject P5 with merestinib therapy alone. One potential explanation is that resistance to MET inhibition in AML does not necessarily involve FGFR activation across disease subsets. Indeed, upregulated autocrine MET signaling has also been associated with certain AML cytogenetic subtypes such as t(8;21) and t(15;17) that are thought to implicate other fusion transcription factor proteins in the transactivation of HGF (8). However, we did not observe these cytogenetic abnormalities in the patients included in our pharmacodynamic analyses.

One consistent finding from both the in vitro and clinical aspects of this study is the concordance of changes in the phosphorylation and functional activation of STAT3 and STAT5 with clinical response in AML. Under normal physiologic conditions, these transcription factors transduce signals generated by cytokines that regulate hematopoietic cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation (21). These proteins are normally activated rapidly and transiently to tightly control expression of critical genes. When activated constitutively, as in response to hyperactivity of upstream kinases like MET, they drive the malignant behavior and resistance to standard chemotherapy of AML myeloblasts. Since STATs are convergence points for multiple upstream kinase pathways, alternate means to activate STAT3 or STAT5 is a common mode of resistance in AML and other cancers. This is corroborated clearly in the genes that we found to be prominently upregulated in refractory disease or at the time of disease progression (Figure 3C). All of the genes with the greatest fold change either enhance activation of STAT3 and/or STAT5, or, as in the case of CPA3, are transcriptionally regulated by STATs. These findings reinforce the utility of measuring STAT phosphorylation in patient samples as a predictive biomarker for identifying patients who may respond to signaling inhibitors, and as a pharmacodynamic biomarker to monitor response to these agents (22). In addition, given that there are multiple bypass mechanisms by which activation of other kinases can maintain phosphorylation of STATs (23), our findings reinforce the potential utility of the direct inhibition of STATs as a promising therapeutic approach in AML and the many other cancers driven by inappropriate activation of these transcription factors (24).

Our study has limitations. Firstly, our sample size prevents definitive statements from being made about treatment efficacy, and our exploratory correlative studies require corroboration with additional samples. Secondly, we could not determine the MTD/RP2D of merestinib and LY2874455 due to the study’s early termination and an expansion cohort could not be enrolled. However, we observed clinical response and on-target activity with merestinib 80mg/day, suggesting this to be a minimal effective dose. Thirdly, we lacked a priori knowledge of the degree of MET oncogene addiction in our patient cohort, which was likely heterogeneous and influenced treatment responses. To help future MET inhibitor studies enrich for AML patients with greater MET-dependency—a central tenet of precision oncology—we explored whether the ex vivo response of patient pre-treatment myeloblasts to merestinib and LY2874455 could serve as a biomarker for in vivo treatment sensitivity. No strong correlations were observed. This could reflect experimental conditions, such as the length of time of exposure to the drug ex vivo, or it could reflect biologic factors, such as the loss of survival signals present in vivo during these in vitro assays. Improving patient selection may also require further preclinical investigation to elucidate AML MET signaling. Kentsis et al. primarily demonstrated the activity of concomitant MET and FGFR inhibition using the KG1 cell line, which bears a translocation involving FGFR1 (7). However, the mechanism by which FGFR trans-activates MET, and whether it requires an FGFR1 translocation, is not fully known. Translocations can be missed during the diagnostic work-up of AML if they elude detection by metaphase cytogenetics and FISH panels or if RNA fusion panels are not available. Furthermore, it is possible that the HGF-MET axis conspires with as yet undetermined ligand-dependent activation of receptor tyrosine kinases other than FGFR (8). Future study of additional AML mutational subgroups using AML cell lines, mouse xenografts, and ideally primary patient samples would be informative. Alternative mechanisms of oncogenic MET signaling—e.g. via copy number amplifications as has been seen in solid tumor malignancies—should also be explored. Finally, merestinib exhibits multikinase inhibitory activity and it is possible that some of the biologic effects of this drug are mediated by effects on other pathways.

Methodologic limitations of our study include the use of CellTiter-Glo for viability assessment, which is an assay for metabolic death, though apoptosis following concurrent MET and FGFR inhibition was previously reported by Kentsis et al. in cell lines via assessment of cleaved caspase 3 (7). Additionally, we focused on the impact of MET inhibition on downstream STAT signaling in AML but modulation of other downstream pathways (e.g. PI3K/AKT, RAS/ERK) may well contribute to the therapeutic effects of these drugs and should be considered in future studies.

In conclusion, our Phase 1 clinical trial provided preliminary evidence that the combination of merestinib and the FGFR inhibitor LY2874455 is safe and tolerable for patients with R/R AML. The primary DLT observed was grade 3 reversible transaminase elevations. Though a small cohort, our correlative studies provide compelling in-human evidence that the HGF/MET axis is a targetable and biologically active pathway in AML worthy of further investigation. Recently, a phase 1B trial demonstrated safety and a 53% overall response rate with cytarabine and ficlatuzumab, a first-in-class anti-HGF antibody, in refractory AML (25) with plans of a Phase 2 study to follow (NCT04100330), providing independent evidence of the potential utility of targeting this pathway.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

Acute myeloid leukemia is frequently characterized by aberrant MET signaling driven by FGFR-mediated autocrine HGF production. In preclinical studies, the combination of a MET and FGFR inhibitor exhibits enhanced cytotoxicity compared to MET inhibition alone in AML cell lines and xenograft models. This phase 1 study evaluated the safety and biologic activity of merestinib, a MET inhibitor, plus LY2874455, an FGFR inhibitor, in patients with relapsed/refractory AML. Although the maximum tolerated dose could not be determined due to drug supply discontinuation, our results demonstrate tolerability of merestinib plus LY2874455 at the doses examined with the primary DLT observed being reversible grade 3 transaminase elevations. While limited clinical benefit was observed, one patient achieved complete remission, suggesting anti-leukemic activity that requires further investigation. Correlative studies demonstrate on-target attenuation of MET signaling, providing insight regarding signal transduction perturbations downstream of MET inhibition particularly involving STAT3 and STAT5.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded and drug was supplied by Eli Lilly and Company. We thank the patients and their medical providers who participated in this study. We also thank Adrienne de Jong for her project management. J. Garcia is supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number K08CA245209. The laboratory studies were also supported by a generous gift from Stephen P. Koster, Esq. (DAF) and by the Ted and Eileen Pasquarello Tissue Bank in Hematologic Malignancies.

Conflict of Interest:

A.T. Look is a founder and shareholder of Light Horse therapeutics, and an adviser to Light Horse therapeutics and Omega Therapeutics, which are pursuing activities unrelated to the current manuscript. R.M. Stone serves on the advisory board of Abbvie, Actinium, Arog, BMS, Boston Pharmaceuticals, CTI pharma, GSK, Janssen, Jazz, Novartis, Syros, AvenCell, and Kura Onc, and on the data and safety monitoring board of Takeda, Aptevo, Epizyme, and Syntrix. D.J. DeAngelo has consulted for Abbvie, Amgen, Autolus, Agios, Blueprint, Forty-Seven, Gilead, Jazz, Kite, Novartis, Pfizer, Servier, and Takeda, and has received research funding from Abbvie, Novartis, Blueprint, and Glycomimetrics. J.S. Garcia serves on steering committee for AbbVie, scientific ad boards for AbbVie, Astellas, and Genentech, and received institutional trial support from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Pfizer, and Prelude. The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ganzel C, Sun Z, Cripe LD, Fernandez HF, Douer D, Rowe JM, et al. Very poor long-term survival in past and more recent studies for relapsed AML patients: The ECOG-ACRIN experience. Am J Hematol 2018;93(8):1074–81 doi 10.1002/ajh.25162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perl AE, Martinelli G, Cortes JE, Neubauer A, Berman E, Paolini S, et al. Gilteritinib or Chemotherapy for Relapsed or Refractory FLT3-Mutated AML. N Engl J Med 2019;381(18):1728–40 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1902688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein EM, DiNardo CD, Pollyea DA, Fathi AT, Roboz GJ, Altman JK, et al. Enasidenib in mutant IDH2 relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2017;130(6):722–31 doi 10.1182/blood-2017-04-779405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiNardo CD, Stein EM, de Botton S, Roboz GJ, Altman JK, Mims AS, et al. Durable Remissions with Ivosidenib in IDH1-Mutated Relapsed or Refractory AML. New England Journal of Medicine 2018;378(25):2386–98 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1716984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taksin AL, Legrand O, Raffoux E, de Revel T, Thomas X, Contentin N, et al. High efficacy and safety profile of fractionated doses of Mylotarg as induction therapy in patients with relapsed acute myeloblastic leukemia: a prospective study of the alfa group. Leukemia 2007;21(1):66–71 doi 10.1038/sj.leu.2404434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Xia M, Jin K, Wang S, Wei H, Fan C, et al. Function of the c-Met receptor tyrosine kinase in carcinogenesis and associated therapeutic opportunities. Mol Cancer 2018;17(1):45 doi 10.1186/s12943-018-0796-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kentsis A, Reed C, Rice KL, Sanda T, Rodig SJ, Tholouli E, et al. Autocrine activation of the MET receptor tyrosine kinase in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Med 2012;18(7):1118–22 doi 10.1038/nm.2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGee SF, Kornblau SM, Qiu Y, Look AT, Zhang N, Yoo SY, et al. Biological properties of ligand-dependent activation of the MET receptor kinase in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2015;29(5):1218–21 doi 10.1038/leu.2014.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim B, Wang S, Lee JM, Jeong Y, Ahn T, Son DS, et al. Synthetic lethal screening reveals FGFR as one of the combinatorial targets to overcome resistance to Met-targeted therapy. Oncogene 2015;34(9):1083–93 doi 10.1038/onc.2014.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu W, Bi C, Credille KM, Manro JR, Peek VL, Donoho GP, et al. Inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer by LY2801653, an inhibitor of several oncokinases, including MET. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19(20):5699–710 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-13-1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan SB, Peek VL, Ajamie R, Buchanan SG, Graff JR, Heidler SA, et al. LY2801653 is an orally bioavailable multi-kinase inhibitor with potent activity against MET, MST1R, and other oncoproteins, and displays anti-tumor activities in mouse xenograft models. Invest New Drugs 2013;31(4):833–44 doi 10.1007/s10637-012-9912-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He AR, Cohen RB, Denlinger CS, Sama A, Birnbaum A, Hwang J, et al. First-in-Human Phase I Study of Merestinib, an Oral Multikinase Inhibitor, in Patients with Advanced Cancer. Oncologist 2019;24(9):e930–e42 doi 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saleh M, Cassier PA, Eberst L, Naik G, Morris VK, Pant S, et al. Phase I Study of Ramucirumab Plus Merestinib in Previously Treated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Safety, Preliminary Efficacy, and Pharmacokinetic Findings. Oncologist 2020;25(11):e1628–e39 doi 10.1634/theoncologist.2020-0520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valle JW, Vogel A, Denlinger CS, He AR, Bai LY, Orlova R, et al. Addition of ramucirumab or merestinib to standard first-line chemotherapy for locally advanced or metastatic biliary tract cancer: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2021;22(10):1468–82 doi 10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00409-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michael M, Bang YJ, Park YS, Kang YK, Kim TM, Hamid O, et al. A Phase 1 Study of LY2874455, an Oral Selective pan-FGFR Inhibitor, in Patients with Advanced Cancer. Target Oncol 2017;12(4):463–74 doi 10.1007/s11523-017-0502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Büchner T, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood 2017;129(4):424–47 doi 10.1182/blood-2016-08-733196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yadav B, Wennerberg K, Aittokallio T, Tang J. Searching for Drug Synergy in Complex Dose-Response Landscapes Using an Interaction Potency Model. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2015;13:504–13 doi 10.1016/j.csbj.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bar-Natan M, Nelson EA, Xiang M, Frank DA. STAT signaling in the pathogenesis and treatment of myeloid malignancies. Jakstat 2012;1(2):55–64 doi 10.4161/jkst.20006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gough DJ, Marié IJ, Lobry C, Aifantis I, Levy DE. STAT3 supports experimental K-RasG12D-induced murine myeloproliferative neoplasms dependent on serine phosphorylation. Blood 2014;124(14):2252–61 doi 10.1182/blood-2013-02-484196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kosciuczuk EM, Saleiro D, Kroczynska B, Beauchamp EM, Eckerdt F, Blyth GT, et al. Merestinib blocks Mnk kinase activity in acute myeloid leukemia progenitors and exhibits antileukemic effects in vitro and in vivo. Blood 2016;128(3):410–4 doi 10.1182/blood-2016-02-698704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tošić I, Frank DA. STAT3 as a mediator of oncogenic cellular metabolism: Pathogenic and therapeutic implications. Neoplasia 2021;23(12):1167–78 doi 10.1016/j.neo.2021.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frank DA. Transcription factor STAT3 as a prognostic marker and therapeutic target in cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31(36):4560–1 doi 10.1200/jco.2013.52.8414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao C, Li H, Lin HJ, Yang S, Lin J, Liang G. Feedback Activation of STAT3 as a Cancer Drug-Resistance Mechanism. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2016;37(1):47–61 doi 10.1016/j.tips.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heppler LN, Frank DA. Targeting Oncogenic Transcription Factors: Therapeutic Implications of Endogenous STAT Inhibitors. Trends Cancer 2017;3(12):816–27 doi 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang VE, Blaser BW, Patel RK, Behbehani GK, Rao AA, Durbin-Johnson B, et al. Inhibition of MET Signaling with Ficlatuzumab in Combination with Chemotherapy in Refractory AML: Clinical Outcomes and High-Dimensional Analysis. Blood Cancer Discov 2021;2(5):434–49 doi 10.1158/2643-3230.Bcd-21-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are not publicly available due to information that could compromise patient privacy or consent but are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.