Abstract

Motivation

Our ability to identify causative genetic factors for mouse genetic models of human diseases and biomedical traits has been limited by the difficulties associated with identifying true causative factors, which are often obscured by the many false positive genetic associations produced by a GWAS.

Results

To accelerate the pace of genetic discovery, we developed a graph neural network (GNN)-based automated pipeline (GNNHap) that could rapidly analyze mouse genetic model data and identify high probability causal genetic factors for analyzed traits. After assessing the strength of allelic associations with the strain response pattern; this pipeline analyzes 29M published papers to assess candidate gene–phenotype relationships; and incorporates the information obtained from a protein–protein interaction network and protein sequence features into the analysis. The GNN model produces markedly improved results relative to that of a simple linear neural network. We demonstrate that GNNHap can identify novel causative genetic factors for murine models of diabetes/obesity and for cataract formation, which were validated by the phenotypes appearing in previously analyzed gene knockout mice. The diabetes/obesity results indicate how characterization of the underlying genetic architecture enables new therapies to be discovered and tested by applying ‘precision medicine’ principles to murine models.

Availability and implementation

The GNNHap source code is freely available at https://github.com/zqfang/gnnhap, and the new version of the HBCGM program is available at https://github.com/zqfang/haplomap.

Supplementary information

Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

No model organism has contributed more than the laboratory mouse to improving human health. Many genetic factors and therapies for human diseases were discovered or characterized in mice, before they transitioned to human use. Large-scale efforts are underway to integrate recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) into the human healthcare system; these tools have impacted multiple clinical arenas, which include radiology (Lee and Summers, 2021), cardiology (Kodera et al., 2022), oncology (Bera et al., 2022; Vobugari et al., 2022) and even psychiatry (Zakhem et al., 2021). However, very few of the advances in AI have been used for analysis of model organism data, which have formed the foundation many healthcare innovations. Many genetic discoveries were made using genome-wide association study (GWAS) methods, which compare allelic differences in mouse (or human) populations with variation in phenotypic responses. However, similar to the difficulties encountered with GWAS using human populations (Gallagher and Chen-Plotkin, 2018), a GWAS utilizing inbred mouse strains will identify a true causative genetic variant along with multiple other false positive associations. The allelic patterns in many genomic regions can correlate with any given response pattern, but usually only one region contains the true causative genetic factor. While methods that correct for the false positive associations that result from commonly inherited genomic segments have proven useful for human GWAS studies (International HapMap Consortium, 2007; Purcell et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2007), we found that these correction methods have to be carefully applied to murine GWAS, since they could lead to rejection of true causative murine genetic factors (Wang et al., 2021). We also found that evaluating the gene candidates emerging from murine GWAS using multiple criteria produced superior results relative to applying only a single highly stringent genetic criterion. Causative genetic factors could be selected from among the many candidate genes identified in a murine GWAS using gene expression and metabolomic data (Liu et al., 2010), curated biologic information (Zhang et al., 2011) or the genomic regions delimited by prior QTL analyses (LaCroix-Fralish et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2008). We recently demonstrated that using structured computational methods to select for genetic factors that met certain criteria enhanced our ability to identify causative genetic factors (Arslan et al., 2020).

We previously analyzed one phenotype at a time; but a vast amount of mouse phenotypic data is now available. For example, the Mouse Phenome Database (MPD) (http://phenome.jax.org) has 10 307 datasets (1.52M responses) covering a wide range of biomedical responses measured in panels of inbred strains (Grubb et al., 2014). They can be used for genetic discovery since an MPD dataset was used to identify a genetic factor for a drug-induced CNS toxicity (Zheng et al., 2015), and a potential new preventative treatment emerged from this discovery (Zhang et al., 2016). However, many more genetic discoveries could be made if all 10 307 MPD datasets could be analyzed, but an investigator would have to examine thousands of datasets to identify those whose measured phenotypic differences are likely to be genetic, and then sift through the many genes with correlated alleles to identify the likely causative genetic candidate(s) for each dataset. If 10–100 candidate genes were generated for each of ∼1000 selected datasets (i.e. up to ∼1M possible genetic leads), the output could not be examined by one individual, nor even by the entire Stanford University faculty. However, ML (Greener et al., 2022) and (more recently) graph neural network (GNN)-based methods (Nicholson and Greene, 2020; Zhang et al., 2021) have been used to analyze various types of complex biomedical data, which include: prediction of drug–drug interactions (Zitnik et al., 2018), prioritization of disease-causing gene candidates (Han et al., 2019), interpretation of proteomic data (Santos et al., 2022) and for drug repurposing (Wang et al., 2020). To enable the large-scale analysis of mouse genetic model data, we produced a computational pipeline that (i) could identify candidate genes with alleles that correlate with the response pattern exhibited by the strains; and (ii) a GNN-based method to predict those most likely to be causal based upon assessment of the candidate gene–phenotype relationship and other factors. Here, we describe the components of this analysis pipeline, characterize its performance relative to other types of neural networks, and demonstrate that it can identify high-quality candidate genes for some of the available MPD datasets.

2 Results

2.1 Our motivation for using a GNN for automated candidate gene prioritization

Assessing the impact that a large number of candidate genes, which GWAS results indicate have an allelic pattern that correlates with phenotypic differences within a population, could have on an analyzed phenotype is a very challenging task. The filtering processes used to identify causal genetic factors are at minimum very time-consuming for an investigator to perform, and it is very difficult to comprehensively evaluate the available literature along with multiple other data sources for even a moderately sized list of candidate genes. In silico prediction programs have been developed to prioritize candidate genetic variants. Several rely on sequence-based features [e.g. SIFT (Hu and Ng, 2012), FATHMM-XF (Rogers et al., 2018)]; and ML-based methods are used to assess variant pathogenicity [e.g. M-Cap (Jagadeesh et al., 2016)] or to prioritize causal genes based upon human Mendelian disease associations [e.g. AMILIE (Birgmeier et al., 2021)]. However, the ability of programs, which analyze human genetic disease associations, to identify causal genetic factors for mouse populations is limited. Here, we utilize the PubMed database, a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network, and protein sequence information to build a multi-modal knowledge graph. We then developed a GNN-based inference tool, which could analyze heterologous sources of data, to accelerate the discovery of causal genetic factors for mouse genetic models. Of importance, this analysis is not limited to the information contained in the human Mendelian disease database. Our hypothesis is that analysis of the biomedical literature along with various types of other information (PPI and protein sequence) could be used to assess the relationship between a gene candidate and an analyzed phenotype, and the results of this analysis can be used to identify causal genetic factors for phenotypic traits. We consider PPI network information, because a candidate gene may be within a functional pathway (or have an interaction partner) that is known to contribute to a related phenotype. We also leverage protein sequence information because information about structurally related proteins (e.g. orthologs, paralogs or homologs) may also be utilized for assessing gene–phenotype relationships. To do this, the protein sequences were transformed into a statistical representation using the UniRrep (Alley et al., 2019) model, which could then be evaluated by the GNN.

2.2 The architecture of GNNHap

To facilitate genetic discovery, we developed a computational pipeline that automated the analysis of mouse genetic model data (Fig. 1A). Candidate gene identification was performed using haplotype-based computational genetic mapping (HBCGM) (Liao et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2012) and gene candidate prioritization was reduced to a link prediction task using a multi-modal graph. In other words, the relationship between each member of a set of candidate genes and a biomedical phenotype was assessed using a GNN-based link prediction model (GNNHap). GNNHap was trained using a multi-modal graph that evaluated: the strength of the genetic association, the candidate gene–phenotype relationship from analysis of the biomedical literature, PPIs and protein sequence features. Of importance, this algorithm was trained in an end-to-end manner, without manually crafted features or pre-defined data fusion rules. GNNHap used the following components to rapidly analyze MPD datasets and identify the most probable candidate genetic factors (Fig. 1A): (i) HBCGM was used to identify genes with an allelic pattern that correlated with the phenotypic response pattern for each analyzed trait. This mapping program was extensively redesigned and optimized so that it could analyze a 25M SNP database with alleles covering 53 inbred strains (Arslan et al., 2020), and the 6.9M indels and 145K structural variants (>50 bp) that were also in the database (Arslan et al., 2022). A statistical model was added (Wang et al., 2021) that identified haplotypes affected by population structure among the inbred strains; and a new web application was developed for data visualization. (ii) Natural language processing was used to analyze the abstracts for the 29M papers (from 5600 journals) in the PubMed database (Mork et al., 2017; Sayers et al., 2021). Since these papers are indexed using a controlled vocabulary that consists of >30K Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms; the phenotypes were represented by MeSH terms. A large multi-modal graph that consisted of gene–MeSH pairs (based upon their co-occurrence in the literature), PPIs and the MeSH-network (Fig. 1B) was used to assess the strength of the relationship between candidate genes and an analyzed phenotype. (iii) A novel heterogeneous GNN that encoded the relationships for the gene–MeSH pairs was developed (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. S1A and B). UniRep (Alley et al., 2019) protein sequence embeddings provided additional input to the GNN (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Overview of the GNNHap pipeline. (A) This flowchart shows the major steps used to analyze the mouse genetic model data. This pipeline uses the datasets in a MPD and another database with SNP, indel and SV alleles generated from analysis of whole-genome sequence data from 53 inbred strains. The HBCGM modules uses the variant database to assemble haplotype blocks for strains that were analyzed in the phenotypic dataset, and it then statistically assesses the correlation between the alleles within the haplotype blocks and the measured strain responses. The output (candidate genes based upon the calculated genetic association) is passed to the GNN module, which assesses the relationship (literature score) between the MeSH term (which is a surrogate for the phenotype) and gene candidates. The final output is a list of prioritized gene candidates that are visualized by a web application. (B) The heterogeneous graph consists of PPIs, gene–MeSH associations and a MeSH relational network that was constructed using a hierarchical tree structure with 16 edge types (relationships). A potential association between a candidate gene and a MeSH term (indicated by a ‘?’), which is considered as a missing link in the heterogenous graph, is quantitatively evaluated by this computational pipeline. (C) The genes are initially represented by their amino acid sequences, which are then transformed into statistical embeddings using the UniRep (Alley et al., 2019) model. For the literature analysis, the phenotype (represented by the MeSH term) is converted into sentence embeddings using SentenceTransformers (Reimers and Gurevych, 2019). Three stacked modules are then used to refine the gene and MeSH feature vectors: a graph convolutional network (GCN); a relational graph convolutional network (RGCN); and a graph attention network (GAT). The gene embeddings are passed to the GCN module to obtain the PPI information, while MeSH embeddings were passed to the RGCN module to generate the MeSH–MeSH relationship. The GAT module is run on the gene–MeSH association graph to further refine the embeddings of the genes and MeSH terms, which is accomplished by exchanging information between gene and MeSH terms. Finally, two fully connected layers (LinkPredictor) are used to reduce the dimensions of the latent vector and to predict the probability that the gene and MeSH terms are associated. The numbers shown in the panel indicate the dimensions of the input and output vectors

2.3 Evaluation of GNNHap performance

After determining the appropriate preprocessing steps and hyperparameters (see Supplemental Methods), the GNN model fitted the test dataset well; the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve and area under the precision-recall curve with the testing dataset were ∼0.95 (Supplementary Fig. S1C). An ablation analysis was performed to investigate the effectiveness and the necessity for the components of the GNN. To do this, the GNN Encoder (Fig. 1C) was removed, and we evaluated the performance of the LinkPredictor module, which is a 2-layer fully connected neural network, using the same hyperparameter settings and training dataset that were used to evaluate the GNN model (Supplementary Fig. S1D). Across a range of thresholds (0.5–0.95) that were used for defining a positive connection, the GNN model predictions had markedly improved accuracy (by up to 46%) and recall (by up to 311%) rates relative to that of the LinkPredictor (Supplementary Fig. S1E and Supplementary Table S1). Although the GNN model had a slightly (5–9%) lower precision rate than the LinkPredictor model; this was expected because the GNN analyzes relations and interactions among connected neighbors, which generates a larger number of positive link predictions than the LinkPredictor model (Supplementary Fig. S1E). These results indicate that the GNN is superior at finding the ‘missing links’ in the gene–MeSH literature graph than a standard 2-layer neural network, which enables the GNNHap output to better assess the probability that a candidate gene is associated with an analyzed phenotype.

2.4 GNNHap can identify known causative genetic factors

To test whether GNNHap could identify causative genetic factors, we analyzed MPD datasets that we previously used to identify causal genetic factors, which were experimentally validated. As one example, BTBR T+Itpr3tf/J (BTBR) mice uniquely display neuroanatomic abnormalities and behaviors that are characteristic of human Autism Spectral Disorder, which include agenesis of the corpus collosum (CC) (Bolivar et al., 2007; Ellegood and Crawley, 2015; McFarlane et al., 2008; Moy et al., 2008). GNNHap analysis (MeSH term: Corpus Callosum) of three MPD datasets (10812, 10809 and 10806) with CC measurements (Fig. 2A) identified an 8-bp frameshift deletion in Exon 2 of the dorsal repulsive axon guidance protein (Draxin) that was uniquely present in BTBR mice as a high probability candidate gene (Rank 2; genetic P-value: 3.4 ×10−7, literature score: 0.71) (Fig. 2B and C). Since it can be difficult to understand the basis for GNN output (Greener et al., 2022), we designed a visualization tool that enabled a some of the key data used by GNNHap to be examined (Fig. 2C). In this case, Draxin was the only gene with a high impact variant that was directly connected with the CC by the literature analysis. This variant generates a truncated BTBR Draxin protein that is missing key domains that are essential for its function, and we demonstrated that BTBR commissural abnormalities are corrected after reversion of this 8-bp deletion (Arslan et al., 2022). We previously used another MPD dataset (MPD: 39410) to identify a pharmacogenetic susceptibility factor for a drug (haloperidol)-induced toxicity that resembles Parkinson’s disease. Allelic variation within a murine transporter (Abcb5) determined susceptibility by altering brain haloperidol levels (Zheng et al., 2015). GNNHap analysis of this dataset (MeSH term: drug-related side effects) identified Abcb5 as a high probability candidate gene (Rank 1; genetic P-value: 5.4 ×10−10; literature score: 0.84) (Supplementary Fig. S2). GNNHap analysis of MPD datasets for survival after anthrax toxin exposure (MPD: 1501) (Supplementary Fig. S3), and plasma HDL cholesterol levels (MPD: 9904) (Supplementary Fig. S4) also identified the experimentally validated causal genetic factors for these datasets.

Fig. 2.

GNNHap analysis correctly identifies a genetic factor contributing to agenesis of the CC. (A) CC length measurements made at the mid-sagittal plane in 21 inbred strains (MPD: 10806) indicate that the CC is absent in BTBR mice. (B) The graphical output of the GNNHap analysis of this dataset is shown, and it identified Draxin as one of the two most likely candidate genes. (C) The GNNHap data that was evaluated for 10 genes with the strongest genetic association with CC dimensions are shown. The chromosome (Chr) and the starting (chrStart) and ending (chrEnd) position of each haplotype block are also shown. The unique color of the square within the haplotype diagram indicates that only the first five genes have a BTBR-unique haplotype. The popPvalue, which assesses the relationship of the alleles in the candidate gene with population structure, was calculated as described in Wang et al. (2021). The alleles in the Draxin haplotype blocks are not associated with population structure, while the Parp10 alleles are. PubMed identification numbers are only provided if a MeSH term and gene have a direct link in the literature graph. However, the literature analyses (MeSH term: Corpus Callosum, D002386) reveal that only Draxin has a direct association with the CC. In contrast, all the other candidate genes have an indirect relationship with this MeSH term, which could result from MeSH term relationships identified with other proteins that are associated with these candidates

2.5 A genetic factor for a murine ‘diabesity’ model

We investigated whether GNNHap could facilitate novel genetic discovery by analyzing MPD datasets where the causative genetic factors were not known. For these analyses, GNNHap selected genes with high impact alleles, which included those causing premature termination codons (PTC), deletions or frameshifts. As one example, three MDP datasets contained hematological measurements of peripheral blood cells obtained from the same panel of inbred strains: the monocyte count (MPD: 24317), the percentage of neutrophils (MPD: 24309) and the total number of large unstained leukocytes (MPD: 24331) (Peters et al., 2002). These datasets were of interest because NZW/LacJ mice had the highest values for each of these measurements (Fig. 3A–C). GNNHap analysis identified the same high impact allele for all three datasets as the most likely causative genetic factor: a 1-bp frameshift deletion that generated a PTC at amino acid codon 5 of Toll-like receptor 5 (Tlr5) (Fig. 3D and E). This variant rendered NZW/LacJ mice as the equivalent of mice with a Tlr5 KO. Since Tlr5 agonists promote neutrophil and macrophage influx into tissues under basal and disease-associated conditions (Ellenbroek et al., 2017; Imhof et al., 2017; Lei et al., 2021) and Tlr5 plays a key role in myeloid differentiation (Imhof et al., 2017), this explains why a strain (NZW/LacJ) with this Tlr5 variant would have the highest levels of monocytes, neutrophils and undifferentiated cells in its peripheral blood.

Fig. 3.

NZW/LacJ, TallyHo, MOLF and SPRET mice produce a non-functional Tlr5 protein. (A) The monocyte counts measured in 30 inbred strains are shown (MPD: 24317), and NZW/LacJ mice have the highest value among the analyzed strains. (B) The graph output by the GNNHap analysis of this dataset is shown. It identified Tlr5 and Krtap5-1 as the two candidate genes with high impact alleles that had the strongest genetic association with the phenotypic pattern. Multiple haplotype blocks within Tlr5 and Krtap5-1 had NZW/LacJ-specific haplotypes. (C) The GNNHap data evaluated for the top-ranked candidate genes are shown. The literature analyses (MeSH term: Monocytes, D009000) of these candidate genes revealed that only Tlr5 had a direct association with monocytes. (D) NZW/LacJ, TallyHo, MOLF and SPRET mice have a 1-bp frameshift deletion (rs223247201) in Exon 4 of Tlr5 that is not present in the 49 other strains with available genomic sequence. (E) This deletion generates a termination codon after amino acid 7 of the Tlr5 protein. The protein domains present in the full length (C57BL/6) and truncated (NZW/LacJ, TallyHo, MOLF and SPRET) Tlr5 proteins are shown

It was noteworthy that among the 53 strains in our SNP database, the Tlr5 frameshift variant was present in only four strains (NZW/LacJ, MOLF/EiJ, SPRET/EiJ and TALLYHO/JngJ), and two of them (MOLF/EiJ and SPRET/EiJ) are wild-derived strains. Although TallyHo mice were rarely among the strains examined in MPD datasets, the presence of the Tlr5 variant in TallyHo mice was of interest. TallyHo mice provide a murine model for human type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and obesity (aka ‘diabesity’); they spontaneously develop hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance and glucose intolerance (Kim and Saxton, 2012). Analyses of TallyHo intercross progeny identified 7 genomic regions and 14 pairs of interacting loci that could contribute to its metabolic syndrome (Stewart et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2005; Parkman et al., 2017). Moreover, a prior analysis of TallyHo genomic sequence identified 961 SNPs (in 372 genes) and 576 indels (in 215 genes) as potentially pathogenic (Denvir et al., 2016). Despite the availability of genomic sequence data, the multiple genetic (Joost and Schürmann, 2014; Kim et al., 2001, 2005; Parkman et al., 2017) and genomic studies performed on TallyHo mice, and the many implicated pathways; the genetic basis for its metabolic syndrome was not known. However, Tlr5 (Chr1 182.7 MB) is located within the chromosome 1 interval (beyond 144 MB) that was shown to contribute to the obesity and hypercholesterolemia of TallyHo mice. The Tlr5 variant also makes TallyHo mice the equivalent of mice with an engineered Tlr5 KO, which were shown to develop hyperlipidemia and insulin resistance (Vijay-Kumar et al., 2010). TLR5 has a well characterized role in regulating inflammatory responses (Agrawal et al., 2003). However, it is highly expressed in intestinal mucosa and is a bacterial flagellin receptor, which enables it to play a major role in regulating microbial responses (Vijayan et al., 2018). The metabolic syndrome observed in Tlr5 KO mice was shown to develop because of alterations in their intestinal microbiota, and it could be corrected by antibiotic treatment (Vijay-Kumar et al., 2010). Thus, GNNHap analysis identified a Tlr5 mutation, which based upon a phenotype appearing in previously analyzed Tlr5 KO mice that is likely to contribute to the metabolic syndrome of TallyHo mice.

2.6 Candidate genetic factors for other disease models

Another MPD dataset (MPD: 26710) of cataract incidence among inbred strains revealed that male and female PL/J mice had a very high incidence of corneal opacities (Fig. 4A–C). GNNHap analysis identified a PL/J-unique frameshift variant (13_13465492_TAA/TA) in Nidogen 1 (Nid1) (Fig. 4D) as a likely contributor because: PL/J mice express a severely truncated NID1 protein (Fig. 4E); Nid1 is involved in matrix assembly in the lens and in other tissues (Dong et al., 2002; Salmivirta et al., 2002); a Nid1 frameshift mutation in cattle caused cataracts (Murgiano et al., 2014); and Nid1 KO mice have lens alterations (May, 2012). Based upon the relationship between a Nid1 frameshift variant and cataracts in cattle and the ocular abnormalities appearing in Nid1 knockout mice, the GNNHap analysis identified the likely genetic factor underlying the high incidence of cataracts in PL/J mice.

Fig. 4.

A frameshift indel generates a non-functional Nid1 protein in PL/J mice. (A) Eye examinations performed on 41 inbred strains (MPD: 26710) show that PL/J mice have a high incidence (∼50%) of corneal opacities. (B) The graphical output of the GNNHap analysis of this dataset is shown. For this analysis, GNNHap was set to analyze candidate genes with high impact indels, and Nid1 was identified as one of the three highest ranked candidate genes. (C) The data evaluated by GNNHap for 10 genes with the strongest genetic association are shown. The chromosome (Chr) and the starting (chrStart) and ending (chrEnd) positions of each haplotype block are also shown. The popPvalue assesses the relationship of the alleles in the candidate gene with population structure, which is calculated as described in Wang et al. (2021), and PubMed identification numbers are only provided if the MeSH term and gene have a direct link in the literature graph. The unique color of the square on the right in the haplotype diagram indicates that all these candidate genes have a PL/J-unique haplotype with a high impact allele (codon flag: 2). However, only two have an allelic pattern that is not associated with population structure (Nid1, Trappc1), and the literature analysis reveals that only Nid1 has a direct association with cataract (MeSH term: D002386). In contrast, the relationship of all other candidate genes with cataract was indirect, which could result from other proteins that are associated with these candidate genes. (D) PL/J has a 1-bp frameshift deletion in Exon 3 of Nid1, which is not present in the 52 other strains with available genomic sequence. (E) This frameshift deletion generates a termination codon after amino acid 279 of the PL/J Nid1 protein. The protein domains present in full length (C57BL/6) and PL/J Nid1 proteins are indicated

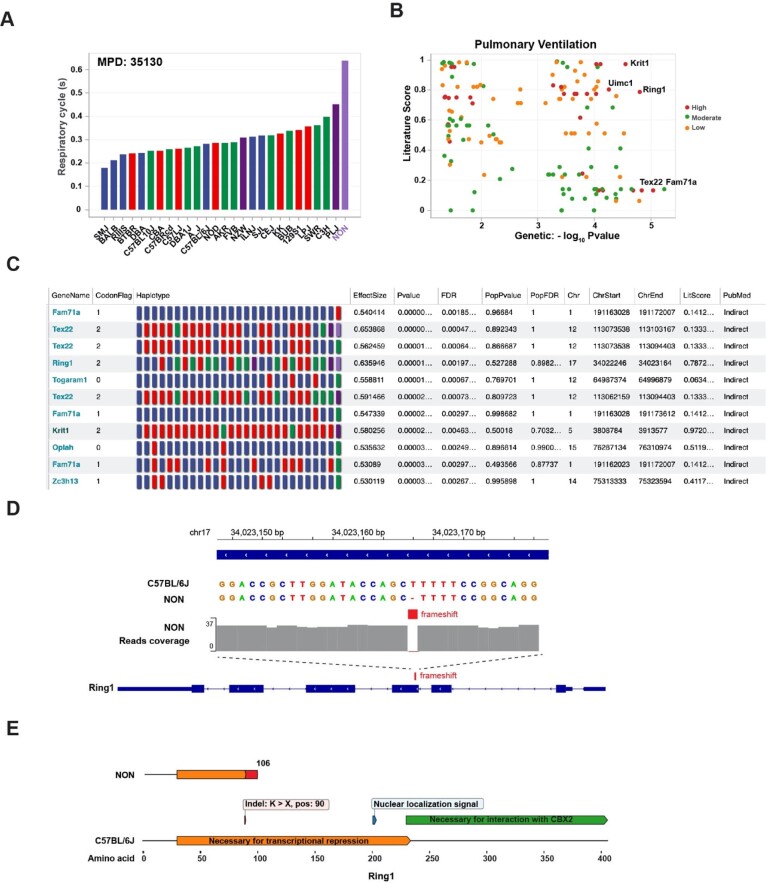

Since an excessive airway response after methacholine challenge is a diagnostic criterion for asthma (Crapo et al., 2000), an MPD dataset (MPD: 35130) (Shalaby et al., 2010) characterizing airway responses in 29 strains after inhalational methacholine challenge was of interest (Fig. 5A). Female NON/ShiLtJ mice exhibited the highest residual volume after methacholine challenge (0.64 ± 0.13 s), which was twice as high as the mean of all analyzed strains (0.30 ± 0.09 s). GNNHap analysis identified three genes with NON/ShiLtJ-unique high impact alleles that correlated with this response pattern (Tex22, Krit1 and Ring1). However, the literature analysis revealed that only Ring1 was strongly associated with an asthmatic phenotype (Fig. 5B and C). NON/ShiLtJ mice have a unique 1-bp frameshift deletion in Exon 4 of Ring1 (Fig. 5D) and its truncated Ring1 protein lacks domains that are essential for its function (Fig. 5E). This was of interest since Ring1 is a core component of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1) (Schuettengruber et al., 2017), whose function is to silence the expression of many genes during development. Another PRC (PRC2) has a similar function (Blackledge and Klose, 2021; Piunti and Shilatifard, 2021). Ring1 depletion caused a genome-wide reduction in PRC2 binding (Blackledge et al., 2014). PCR2 activity is essential for the generation of allergic responses (Keenan et al., 2019), it regulates the differentiation of airway (Galvis et al., 2015; Snitow et al., 2015) and smooth muscle (Snitow et al., 2016) cells, and it plays a key role in preventing asthma-like airway pathology by regulating the development of inflammatory cells (Tumes et al., 2019). Given the strong relationship between PRC proteins and asthma-like disease in mice, it is likely that the NON/ShiLtJ-unique Ring1 frameshift deletion contributes to their methacholine-induced airway hyperresponsiveness. However, the contribution of this frameshift deletion to the airway phenotype needs to be experimentally validated.

Fig. 5.

NON/ShiLtJ mice produce a non-functional Ring1 protein. (A) The expiratory flow measurements for 27 inbred strains obtained after inhalational methacholine challenge (10 mg/ml) (MPD: 35130) are shown. NON/ShiLtJ mice had the highest expiratory measurement, which was twice the average of the other strains. (B) The graph output by the GNNHap analysis of this dataset identified Ring1 as one of the top candidate genes. The dot color indicates whether the gene has a SNP allele that causes a low, medium or high impact change. (C) The GNNHap data for 11 genes with the strongest genetic association are shown. The unique color of the square in the haplotype diagram indicates that they all have a NON/ShiLtJ-unique haplotype. However, only five have a high impact allele (codon flag: 2), and only two have an allelic pattern that is not associated with population structure (Nid1, Trappc1). The literature analysis (MeSH term: Cataract, D002386) reveals that only Nid1 has a direct association with cataract. In contrast, the relationship of all other candidate genes with cataract was indirect, which could result from other proteins that are associated with those candidate genes. (D) NON/ShiLtJ mice have a 1-bp deletion in exon 4 of Ring1 (within amino acid 90) that is not present in 52 other strains with available genomic sequence. (E) This deletion generates a termination codon after amino acid 106. The protein domains present in the full length (C57BL/6) and NON/ShiLtJ (NON) Ring1 proteins are shown

3 Discussion

We developed an autonomously functioning computational pipeline that can identify genetic candidates for mouse genetic models of biomedical traits and human diseases. As proof of concept, GNNHap identified novel genetic factors for murine genetic models of diabetes and obesity (‘diabesity’) and of cataract formation, which were experimentally validated by prior analyses of gene knockout mice. These analyses were performed with a speed and capacity that is far greater than could be achieved by individual (or even a team of) investigators that were dedicated to analyzing these datasets. The painstaking process of sifting through datasets and then sorting among the candidate genes, which are the initial steps required for identifying causal genetic factors, is greatly reduced. A limitation of the current GNNHap platform is that we focused on a subset of genes with high impact alleles affecting coding regions. However, subsequent versions could evaluate a broader range of alleles by incorporation of modules that can assess allelic effects on mRNA transcription/splicing (Paggi and Bejerano, 2018), PPIs (Gromiha et al., 2017) or on the functions of 5′ (Sample et al., 2019) and 3′ (Bogard et al., 2019) untranslated regions. Another limitation is that candidate selection is dependent upon the presence of a gene–phenotype relationship in the published literature. However, the ability of GNNHap to analyze gene–phenotype relationships for other genes that are within the protein network of the genetic candidates expands its ability to use literature associations for identifying novel genetic factors. Moreover, since gene–phenotype relationships are derived from analysis of 29M publications, this provides a very large amount of information that is continuously increasing. Over 1.1M new PUBMED papers appear each year; and a new publication describing a novel gene that causes a human monogenic disease appears each weekday (Wenger et al., 2017). The increased number of publications and modular enhancements will further increase the ability of GNNHap to identify testable gene candidates for many murine genetic models. Moreover, the GNNHap architecture can be used to evaluate candidates obtained from GWAS involving humans and other organisms, those using SNP-based association methods, or for gene prioritization using other types of biological data (i.e. differentially expressed genes lists).

The GNNHap-enabled finding that the TallyHo metabolic syndrome is likely to be induced by TLR5-dependent alterations in gut microflora is noteworthy. First, a recent review covering all murine genetic models of T2DM (including TallyHo mice) identified 54 chromosomal intervals associated with susceptibility and 72 with comorbidities (including obesity) (Lone and Iraqi, 2022), but despite the many possible gene candidates that were cited, there was no mention of Tlr5. Secondly, this finding enables new therapies for a specific type of metabolic syndrome to be tested using TallyHo mice. It provides an illustrative example of how characterizing the genetic architecture of a murine disease model can bring ‘precision medicine’ [i.e. the method by which clinicians utilize genomic information to prevent or optimize disease treatment (Zeggini et al., 2019)] to murine models. Of relevance, new T2DM therapies must now achieve benefits beyond that of reducing plasma glucose levels (Perreault et al., 2021). While the use of probiotics for prevention or treatment of T2DM is undergoing extensive clinical testing, the mechanism(s) for their beneficial effect in this disease are poorly understood (Tao et al., 2020; Tiderencel et al., 2020). Hence, this GNNHap-enabled finding will allow therapeutic agents, which act a via effects on intestinal flora, to be discovered or characterized using TallyHo mice. Since GNNHap analysis could uncover the genetic basis for other murine disease models, the principles of ‘precision medicine’ can be applied to additional murine disease models, which should increase the number of new therapies that can be developed.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Institute of Health (National Institute for Drug Addiction) award [5U01DA04439902 to G.P.].

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability

The GNNHap source code is freely available at https://github.com/zqfang/gnnhap, and the new version of the HBCGM program is available at https://github.com/zqfang/haplomap. The training, validation and test datasets used in this study are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6463988.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Zhuoqing Fang, Department of Anesthesia, Pain and Perioperative Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

Gary Peltz, Department of Anesthesia, Pain and Perioperative Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

References

- Agrawal S. et al. (2003) Cutting edge: different Toll-like receptor agonists instruct dendritic cells to induce distinct Th responses via differential modulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Fos. J. Immunol., 171, 4984–4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alley E.C. et al. (2019) Unified rational protein engineering with sequence-based deep representation learning. Nat. Methods, 16, 1315–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan A. et al. (2020) High throughput computational mouse genetic analysis. BioRxiv. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.09.01.278465v2.

- Arslan A. et al. (2022) Analysis of structural variation among inbred mouse strains identifies genetic factors for autism-related traits. BioRxiv. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.18.431863v1. [Google Scholar]

- Bera K. et al. (2022) Predicting cancer outcomes with radiomics and artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol., 19, 132–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birgmeier J. et al. (2021) AMELIE3: fully automated Mendelian patient reanalysis at under 1 alert per patient per year. Medrxiv;2020.12.29.20248974.

- Blackledge N.P., Klose R.J. (2021) The molecular principles of gene regulation by polycomb repressive complexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 22, 815–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackledge N.P. et al. (2014) Variant PRC1 complex-dependent H2A ubiquitylation drives PRC2 recruitment and polycomb domain formation. Cell, 157, 1445–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogard N. et al. (2019) A deep neural network for predicting and engineering alternative polyadenylation. Cell, 178, 91–106.e123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolivar V.J. et al. (2007) Assessing autism-like behavior in mice: variations in social interactions among inbred strains. Behav. Brain Res., 176, 21–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crapo R.O. et al. (2000) Guidelines for methacholine and exercise challenge testing-1999. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med., 161, 309–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denvir J. et al. (2016) Whole genome sequence analysis of the TALLYHO/Jng mouse. BMC Genomics, 17, 907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong L. et al. (2002) Neurologic defects and selective disruption of basement membranes in mice lacking entactin-1/nidogen-1. Lab. Invest., 82, 1617–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellegood J., Crawley J.N. (2015) Behavioral and neuroanatomical phenotypes in mouse models of autism. Neurotherapeutics, 12, 521–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenbroek G.H. et al. (2017) Leukocyte TLR5 deficiency inhibits atherosclerosis by reduced macrophage recruitment and defective T-cell responsiveness. Sci. Rep., 7, 42688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer K.A. et al. ; International HapMap Consortium. (2007) A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature, 449, 851–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher M.D., Chen-Plotkin A.S. (2018) The Post-GWAS era: from association to function. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 102, 717–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvis L.A. et al. (2015) Repression of Igf1 expression by Ezh2 prevents basal cell differentiation in the developing lung. Development, 142, 1458–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greener J.G. et al. (2022) A guide to machine learning for biologists. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 23, 40–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromiha M.M. et al. (2017) Protein-protein interactions: scoring schemes and binding affinity. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 44, 31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubb S.C. et al. (2014) Mouse phenome database. Nucleic Acids Res., 42, D825–D834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han P. et al. (2019) Disease-gene association identification by graph convolutional networks and matrix factorization. In: Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, Alaska. pp. 705–713.

- Hu J., Ng P.C. (2012) Predicting the effects of frameshifting indels. Genome Biol., 13, R9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imhof B.A. et al. (2017) Toll-like receptors elicit different recruitment kinetics of monocytes and neutrophils in mouse acute inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol., 47, 1002–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagadeesh K.A. et al. (2016) M-CAP eliminates a majority of variants of uncertain significance in clinical exomes at high sensitivity. Nat. Genet., 48, 1581–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joost H.-G., Schürmann A. (2014) The genetic basis of obesity-associated type 2 diabetes (diabesity) in polygenic mouse models. Mamm. Genome, 25, 401–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan C.R. et al. (2019) Polycomb repressive complex 2 is a critical mediator of allergic inflammation. JCI Insight, 4, e127745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.H., Saxton A.M. (2012) The TALLYHO mouse as a model of human type 2 diabetes. Methods Mol. Biol., 933, 75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.H. et al. (2001) Genetic analysis of a new mouse model for non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Genomics, 74, 273–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.H. et al. (2005) Type 2 diabetes mouse model TallyHo carries an obesity gene on chromosome 6 that exaggerates dietary obesity. Physiol. Genomics, 22, 171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodera S. et al. (2022) Prospects for cardiovascular medicine using artificial intelligence. J. Cardiol., 79, 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaCroix-Fralish M.L. et al. (2009) The β3 subunit of the Na+,K+-ATPase affects pain sensitivity. Pain, 144, 294–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Summers R.M. (2021) Clinical artificial intelligence applications in radiology: chest and abdomen. Radiol. Clin. North Am., 59, 987–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei X. et al. (2021) Flagellin/TLR5 stimulate myeloid progenitors to enter lung tissue and to locally differentiate into macrophages. Front. Immunol., 12, 621665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao G. et al. (2004) In silico genetics: identification of a functional element regulating H2-Ea gene expression. Science, 306, 690–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.-H. et al. (2010) An integrative genomic analysis identifies Bhmt2 as a diet-dependent genetic factor protecting against acetaminophen-induced liver toxicity. Genome Res., 20, 28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lone I.M., Iraqi F.A. (2022) Genetics of murine type 2 diabetes and comorbidities. Mamm. Genome. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00335-022-09948-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May C.A. (2012) Distribution of nidogen in the murine eye and ocular phenotype of the nidogen-1 knockout mouse. ISRN Ophthalmol., 2012, 378641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane H.G. et al. (2008) Autism-like behavioral phenotypes in BTBR T+tf/J mice. Genes Brain Behav., 7, 152–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mork J. et al. (2017) 12 years on - is the NLM medical text indexer still useful and relevant? J. Biomed. Semantics, 8, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy S.S. et al. (2008) Social approach and repetitive behavior in eleven inbred mouse strains. Behav. Brain Res., 191, 118–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgiano L. et al. (2014) Looking the cow in the eye: deletion in the NID1 gene is associated with recessive inherited cataract in Romagnola cattle. PLoS One, 9, e110628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson D.N., Greene C.S. (2020) Constructing knowledge graphs and their biomedical applications. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J., 18, 1414–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paggi J.M., Bejerano G. (2018) A sequence-based, deep learning model accurately predicts RNA splicing branchpoints. RNA, 24, 1647–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkman J.K. et al. (2017) Congenic mice demonstrate the presence of QTLs conferring obesity and hypercholesterolemia on chromosome 1 in the TALLYHO mouse. Mamm. Genome, 28, 487–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreault L. et al. (2021) Novel therapies with precision mechanisms for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol., 17, 364–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters L.L. et al. (2002) Large-scale, high-throughput screening for coagulation and hematologic phenotypes in mice. Physiol. Genomics, 11, 185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piunti A., Shilatifard A. (2021) The roles of polycomb repressive complexes in mammalian development and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 22, 326–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S. et al. (2007) PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 81, 559–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimers N., Gurevych I. (2019) Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, pages 3982–3992, Hong Kong, China, November 3–7, 2019. arXiv e-prints. p. arXiv:1908.10084.

- Rogers M.F. et al. (2018) FATHMM-XF: accurate prediction of pathogenic point mutations via extended features. Bioinformatics, 34, 511–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmivirta K. et al. (2002) Binding of mouse nidogen-2 to basement membrane components and cells and its expression in embryonic and adult tissues suggest complementary functions of the two nidogens. Exp. Cell Res., 279, 188–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sample P.J. et al. (2019) Human 5′ UTR design and variant effect prediction from a massively parallel translation assay. Nat. Biotechnol., 37, 803–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos A. et al. (2022) A knowledge graph to interpret clinical proteomics data. Nat. Biotechnol., 40, 692–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers E.W. et al. (2021) Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res., 49, D10–D17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuettengruber B. et al. (2017) Genome regulation by polycomb and trithorax: 70 years and counting. Cell, 171, 34–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby K.H. et al. (2010) Combined forced oscillation and forced expiration measurements in mice for the assessment of airway hyperresponsiveness. Respir. Res., 11, 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S.B. et al. (2008) Quantitative trait locus and computational mapping identifies Kcnj9 (GIRK3) as a candidate gene affecting analgesia from multiple drug classes. Pharmacogenet. Genomics, 18, 231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snitow M. et al. (2016) Ezh2 restricts the smooth muscle lineage during mouse lung mesothelial development. Development, 143, 3733–3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snitow M.E. et al. (2015) Ezh2 represses the basal cell lineage during lung endoderm development. Development, 142, 108–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart T.P. et al. (2010) Genetic and genomic analysis of hyperlipidemia, obesity and diabetes using (C57BL/6J x TALLYHO/JngJ) F2 mice. BMC Genomics, 11, 713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y.W. et al. (2020) Effects of probiotics on type II diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. J. Transl. Med., 18, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiderencel K.A. et al. (2020) Probiotics for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev., 36, e3213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumes D. et al. (2019) Ezh2 controls development of natural killer T cells, which cause spontaneous asthma-like pathology. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol., 144, 549–560.e510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan A. et al. (2018) Compartmentalized antimicrobial defenses in response to flagellin. Trends Microbiol., 26, 423–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay-Kumar M. et al. (2010) Metabolic syndrome and altered gut microbiota in mice lacking toll-like receptor 5. Science, 328, 228–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vobugari N. et al. (2022) Advancements in oncology with artificial Intelligence-a review article. Cancers, 14, 1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M. et al. (2021) The effect of population structure on murine genome-wide association studies. Front. Genet., 12, 745361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. et al. (2020) Toward heterogeneous information fusion: bipartite graph convolutional networks for in silico drug repurposing. Bioinformatics, 36, i525–i533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger A.M. et al. (2017) Systematic reanalysis of clinical exome data yields additional diagnoses: implications for providers. Genet. Med., 19, 209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. et al. (2011) GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 88, 76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakhem G.A. et al. (2021) Characterizing the role of dermatologists in developing artificial intelligence for assessment of skin cancer. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol., 85, 1544–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeggini E. et al. (2019) Translational genomics and precision medicine: moving from the lab to the clinic. Science, 365, 1409–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. et al. (2016) A pharmacogenetic discovery: cystamine protects against haloperidol-induced toxicity and ischemic brain injury. Genetics, 203, 599–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. et al. (2011) In silico and in vitro pharmacogenetics: aldehyde oxidase rapidly metabolizes a p38 kinase inhibitor. Pharmacogenomics J., 11, 15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.M. et al. (2021) Graph neural networks and their current applications in bioinformatics. Front. Genet., 12, 690049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K. et al. (2007) An arabidopsis example of association mapping in structured samples. PLoS Genet., 3, e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M. et al. (2012) A better prognosis for genetic association studies in mice. Trends Genet., 28, 62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M. et al. (2015) The role of Abcb5 alleles in susceptibility to haloperidol-induced toxicity in mice and humans. PLoS Med., 12, e1001782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitnik M. et al. (2018) Modeling polypharmacy side effects with graph convolutional networks. Bioinformatics, 34, i457–i466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The GNNHap source code is freely available at https://github.com/zqfang/gnnhap, and the new version of the HBCGM program is available at https://github.com/zqfang/haplomap. The training, validation and test datasets used in this study are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6463988.