Abstract

Background:

Down syndrome (DS) has a unique medical and psychological profile which could impact how health is defined on three dimensions: physical, social, and mental well-being.

Methods:

In 2021, we presented our proposed conceptual model to three expert panels, four focus groups of parents of individuals with DS age 0–21 years, and four focus groups of individuals with DS age 13–21 years through videoconferencing technology. Participants gave feedback and discussed the concept of health in DS.

Results:

Feedback from participants resulted in iterative refinement of our model, retaining the three dimensions of health, and modifying constructs within those dimensions. Experts and parents agreed that individuals with DS have unique health concerns that necessitate the creation and validation of a syndrome-specific health model. We present key themes which we identified and a final conceptual model of health for individuals with DS.

Conclusion:

Health in Down syndrome is a multidimensional, multiconstruct model focused on relevant constructs of causal and effect indicators. This conceptual model can be used in future research to develop a syndrome-specific measure of health status.

Introduction

National efforts to measure and improve health, such as Healthy People 2020, focus on specific, high-impact components of health deficits in the general population including diabetes, obesity, heart disease, and dementia.1 Measures of patient reported health exist for general and condition specific populations.2 Researchers and physicians may wish to evaluate the health of their patients, to evaluate the natural history and range of a given genetic syndrome, or to establish a metric for following the impact of future clinical interventions; may seek out a health measure to study specific populations and conditions. However, generic measures for the general population may not be easily applied to all conditions. As such, condition-specific instruments related to health exist, including asthma3, spina bifida4, and epilepsy5, among others6. Specific measures have been developed for individuals with intellectual disability. For example, measures of health-related quality of life have recently been adapted for use by individuals with intellectual disability.7 A variety of self-report instruments for use by individuals with ID exist, such as: self-report measures of psychiatric symptoms8–10, psychotherapy outcomes or quality of life7. Walton et al identified health and health-related behaviour as an area of need in existing measures for individuals with intellectual disability.7

Genetic syndromes may have associated intellectual disability, but by definition, have associated medical and developmental comorbidities differing from the general population. Down syndrome (DS) due to trisomy 21, has co-occurring mental health diagnoses which differ in prevalence and have unique management approaches16. Social factors, like community inclusion, school support, and health care costs also impact those with DS to different degrees than the general population.22–24 Although measures of mental health or social health valid for use in individuals with intellectual disability could be acceptable in DS. DS is also associated with medical comorbidities that differ from population rates and impact organ systems throughout the body. Individuals with DS have increased risk for some conditions: sleep apnea (50–79%), obesity11–15, hearing problems (75%), vision problems (60–80%), congenital heart disease (40–50%), autism (7–19%), and Alzheimer’s disease16–18. However, those with DS also have decreased risk for cardiovascular disease19, atherosclerosis20, and some cancers21. The health of individuals with DS may not be accurately characterised using health instruments that are appropriate for either the general population or for individuals with intellectual disability.

Indeed, syndrome-specific measures exist for some genetic syndromes25,26, like tuberous sclerosis complex27 and Morquio syndrome28. And, although some specific aspects of health in DS have been measured, such as: cognition, behaviour, health-related quality of life29–32, life expectancy33,34, and surgical outcomes for congenital heart disease35. Health-related quality of life has been evaluated in children and adults with DS through the PedsQL36–38 and functional health and well-being through the SF-12v231. However, as we have previously described26, health-related quality of life and health status differ in that health status assesses “how healthy do you feel?” while HRQOL asks “how does your health impact your QOL?”.39 Using an instrument that measures HRQOL may not adequately encapsulate health status, but we hope a measure of health status could have clinical uses and applications such as evaluating a patient’s current health status, as an endpoint for clinical trials, as an outcome measure in quality improvement research, and as a research measure in population health.

To assess the health status of an individual with Down syndrome, it is essential to ask about concepts which incorporate both the co-occurring medical and psychological conditions, in addition to the associated intellectual disability. A fully articulated conceptual model is the necessary precursor to the development of a measurement model for an instrument to measure health in a DS population. In this study, we aimed to develop a conceptual model by developing an initial framework of health from the WHO definition with iterative expansion and refinement following 1) a literature review for any published conceptual models related to DS health, 2) qualitative concept elicitation with professionals (clinical and non-clinical) who work with DS populations/communities, and 3) both caregivers of individuals with DS, and individuals with DS. We hypothesised that a unique conceptual model was needed for Down syndrome, and sought feedback from experts and focus group participants. This process may be applicable to clinicians and researchers studying other genetic syndromes; our findings may also be of interest to other physicians who care for patients with DS and researchers studying DS.

Methods

We adhered to the best practices in developing our conceptual model, as outlined in “Good Practices in Eliciting Concepts for a New Pro Instrument” by International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR).40 The MassGeneral Brigham institutional review board approved this study.

Hypothesised Framework and Model:

The WHO defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”41 We hypothesised three dimensions—physical well-being, mental well-being, and social well-being—forming the foundation for our novel conceptual model of health for DS.42–45 We chose a health model focused on indicators of health, rather than a disease deficit focused model. We developed a conceptual model through literature review, knowledge of DS, and studying of other existing models for other diseases and constructs.

We included people with DS in the development process, but opted to begin with caregiver report for the measure for a number of reasons: health in DS is a new concept to measure, people with DS have varied intellectual disability, people with DS have varied communication styles, and in research to-date, people with DS often rely on caregiver proxies to understand and navigate their health and wellness. We defined health as perceived by adults and caregivers, of individuals with DS age 0–21 years (through observer-report). We chose the age to include those up to school age, but not to include those who have advanced to adult services for homogeneity in our cohort. We intend for our definition to be generalisable to the U.S. population with DS, aiming for this instrument to be as appropriate for as many individuals with DS age 0–21 years as possible. As such, in developing the research protocol for qualitative concept elicitation and analysis, we sought input from experts on children, adolescents, and young adults with DS, parents of individuals with DS, age 0–21, and teens and young adults with DS. We recruited nationally, through social media and email, to capture the variance of key indicators in the target population.

In constructing our conceptual model, we began to plan for a future measurement model, and considered whether constructs were causal indicators, such as risk factors and other external factors, or effect indicators46 such as symptoms and impacts. Causal indicators influence the latent variable (health) and a change in the causal indicator would lead to a change in health. Effect indicators are influenced by the latent variable (health), and will be impacted by health, such that a change in health will drive a change in the effect indicator.

Literature Review:

Targeted literature review to identify conceptual models of health in DS, including what is known about signs and symptoms of health, in the published medical literature was performed. We searched for any DS-specific measures of the major dimensions of health from the WHO definition: physical, mental and social well-being, including global to symptom-specific measures. Literature searches were conducted from January to June 2020 using the National Library of Medicine (NLM) biomedical literature database PubMed (MEDLINE) (NCBI 1946–2020). The National Library of Medicine (NLM) biomedical literature database PubMed was used because it is a large database focused on medicine aligning with our focus on health views. We used the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) (the NLM controlled vocabulary thesaurus for indexing) term “Down syndrome” included the search entry terms: Downs syndrome, Down’s syndrome, Trisomy 21; we used the search terms “conceptual model” and / or “health” or “well-being”. We did not apply limiters to the search, and did not filter or limit searches by publication year. We conducted a review of the Web of Science, practice guidelines or professional statements from the American College of Medical Genetics and the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the gray literature47.

Expert Panels (EPs):

From June to September, 2020, three 2-hour EPs were conducted using Zoom videoconferencing technology. The EPs were organised to reflect three role groups: medical, education, and allied health/supports; within these groups each EP had a mix of member types, for dynamic exchange across roles represented. The invited expert panel participants were from a range of professional roles within medicine, education, and psychosocial support roles. Medical professionals providing care to individuals with DS (primary care physicians, subspecialists and DS clinic experts) and other relevant experts (social workers, teachers) in the field of DS were identified by the research team and invited to attend the EP by e-mail from the PI. Each EP had pre-selected member types to facilitate conversation, and avoid any potential sense of hierarchy perhaps imposed by credentials of panel members. Consent information was shared by e-mail prior to the EP, and each participant gave verbal consent to participate and be recorded prior to EP. The EPs were led by the principal investigator and included a presentation of the draft conceptual model for health in DS and the hypothesised constructs of the model and constituent concepts; physical well-being, mental well-being and social well-being, in order to guide/orient the conversation.42–45 Experts were instructed that the conceptual model should apply to most individuals with DS age 0–21 years. An interviewer guide was developed; three questions were asked for each dimension of the model, physical, mental, and social health: “Do the constructs we propose adequately represent the dimension of physical health?”, “Are there any missing constructs which comprise physical health?”, and “Are there any missing details in the constructs of physical health?”. EPs were audio recorded. Meeting notes and an electronic version of the conceptual model were shared with participants after the EP.

Focus Groups (FGs):

From November 2020 to March 2021, 4 FGs of people with DS and 4 separate FGs of caregivers of people with DS occurred using video technology. The FG participants were recruited from the MGH Down Syndrome Program, the Massachusetts Down Syndrome Congress (MDSC), the LuMind IDSC Down Syndrome Foundation, and the NIH’s DS-Connect® through electronic posting of study information.48–50 Electronic postings included a hyperlink to an electronic form in REDCap which asked demographic information used to screen interested participants on age and sex of son / daughter with DS.51 The research team then contacted interested participants by e-mail to scheduling. FG were organised by age to encourage discussion from parents whose son / daughter were in similar developmental stages; research team scheduled participants to the correct FG organised by age of person with Down syndrome.

Consent information was shared by e-mail prior to the EP/FG; each participant gave verbal consent to participate prior to EP/FG. Separate interviewer guides were created for parent FGs and FGs of individuals with DS. During the parent FG, each dimension of the model was shown with the same questions used to guide the EP: “Do the constructs we propose adequately represent the dimension of physical health?”; “Are there any missing constructs which comprise physical health?”; and “Are there any missing details in the constructs of physical health?” The language of FGs for individuals with DS was modified, and readability was assessed. FGs were transcribed, content was coded and evaluated for themes as described. FG participants were reimbursed with $25 electronic gift cards.

In addition to age and sex, demographic details including race, ethnicity, parent’s perception of the level of cognitive function of the person with DS, and parent’s perception of the medical complexity of the person with DS were collected. When scheduling participants, diversity in race and ethnicity were tracked, but participants were not grouped into FG based on race or ethnicity.

Analysis

EP meeting notes and recordings, and FG video recordings and transcripts were reviewed for themes and new constructs not already categorised in the conceptual model, missing constructs, or missing details in each construct; additional discussion topics relevant to instrument development were reviewed. The number of expert panels and focus groups decided a priori, but analysis was being performed concurrently with data collection and continued until thematic saturation reached. Researchers defined saturation as at least one complete FG conducted without any new concepts added to the model. With the results from literature review, EP and FG, we iteratively developed an original 10-item conceptual model of health in DS across 3 dimensions into a final 59-item conceptual model (Supplemental Table 1 and 2). After each EP or FG, the hypothesised conceptual model was refined and further expanded to include feedback from each EP and FG, including (1) modifying names of existing concepts, (2) adding new concepts, (3) moving the position of a concept in the model, or (4) specifying the relationship between concepts within a dimension of the model.

After all EPs and FGs were completed, the final hypothesised conceptual model of health in DS includes 59-items across three dimensions: 23 items in physical health, 18 items in social health, and 18 items in mental health. We used selective coding based on the topics of discussion surrounding health and iteratively-refined versions of the codebook. At least two members of the research team coded and comparatively reviewed coding of the focus group transcripts to ensure consistency in use of the codebook. After establishing consensus in coding and use of transcripts, the principal investigator and a research assistant then coded the EPs: first, each EP was coded separately for themes and key quotes, then principal investigator and research assistant met to review coding, discuss meaning and value of quotes, and come to consensus. For each EP and FG, the 59 constructs were coded as present / absent, with present indicating that the construct was discussed in the EP or FG as an indication of health in DS and negative indicating that the construct was not discussed.

The de-identified, aggregate data from this study are available upon reasonable request, but recordings and transcriptions are not available as participants did not consent to this.

Final Conceptual Model

After the 4 EPs and 8 FGs, the principal investigator, research assistant, and mentoring team agreed that thematic saturation was reached. Full tracking of conceptual model constructs through EPs and FGs shows changes in terminology and when new concepts were introduced (Supplemental Table 2). The research team organised topics discussed as either causal or effect indicators; most concepts were easily categorised as either causal or effect indicators. For example, demographic traits, like race, are generally static and would not change if someone’s health improved (not an effect indicator), but race could influence health as a social determinant of health (a causal indicator). Better control of a co-occurring diagnosis, like anxiety, (a causal indicator) might lead to better health, and fewer symptoms of that diagnosis (an effect indicator). Some concepts were related through a “feedback loop” and were listed in their primary role – for example, weight in the acceptable range could be a sign of good health (an effect indicator), but if weight became too high or too low, it could lead to worsening of health (a causal indicator); being active could be a sign of good health (an effect indicator), and activity could lead to normal weight and improved health (a causal indicator). Authors agreed on a final conceptual model from iterative refinement of literature review, EPs, and FGs incorporated together.

Results

Literature Review

Our targeted literature review yielded few studies, and identified no existing conceptual models of health in DS. One review article conceptualised health in four distinct models.52 The four major models for conceptualizing health were: the medical model, wellness model, environmental model, and the World Health Organization (WHO) (holistic) model52. Relevant definitions of health and related concepts including: social health, mental health, HRQOL, and well-being were identified through searches of published medical literature and gray literature (Table 1). Definitions showed differences between health and its comprising mental and social dimensions, and incorporated concepts of social interactions, relationships, social adaptability, realizing abilities, coping, and productive contributions (Table 1).

Table 1:

Relevant Definitions of Health and related concepts

| Construct | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Health | Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. | World Health Organization (WHO)1 |

|

| ||

| Social Health | Social health can be defined as our ability to interact and form meaningful relationships with others. It also relates to how comfortably we can adapt in social situations. | George2 |

|

| ||

| Mental Health | Mental health...is a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community (WHO) | WHO |

| Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) | A multi-dimensional concept that includes domains related to physical, mental, emotional, and social functioning. It goes beyond direct measures of population health, life expectancy, and causes of death, and focuses on the impact health status has on quality of life. | Healthy People3 |

| HRQOL | An individual’s or group’s perceived physical and mental health over time. | Centers for Disease Control (CDC)4 |

| HRQOL | An all-inclusive concept incorporating all factors that impact upon an individual’s life. Health-related quality of life includes only those factors that are part of an individual’s health. | Torrance et al.5 |

| HRQOL | Those aspects of self-perceived well-being that are related to or affected by the presence of disease or treatment | Ebrahim et al.6 |

|

| ||

| Well-being | Well-Being Measures – assess the positive evaluations of people’s daily lives—when they feel very healthy and satisfied or content with life, the quality of their relationships, their positive emotions, their resilience, and the realization of their potential. | Healthy People3 |

| Well-being | Well-being is a positive outcome that is meaningful for people and for many sectors of society, because it tells us that people perceive that their lives are going well. Good living conditions (e.g., housing, employment) are fundamental to well-being. Tracking these conditions is important for public policy. However, many indicators that measure living conditions fail to measure what people think and feel about their lives, such as the quality of their relationships, their positive emotions and resilience, the realization of their potential, or their overall satisfaction with life—i.e., their “well-being.”1, 2 Well-being generally includes global judgments of life satisfaction and feelings ranging from depression to joy.3, 4 | CDC4 |

Callahan D. The WHO Definition of “Health.” The Hastings Center Studies. 1973;1(3):77. doi:10.2307/3527467

George T. What is Social Health? HIF Healthy Lifestyle BLog. https://blog.hif.com.au/mental-health/what-is-social-health-definitions-examples-and-tips-on-improving-your-social-wellness

Health-Related Quality of Life and Well-Being. HealthyPeople.gov. Accessed November 4, 2021. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/Health-Related-Quality-of-Life-and-Well-Being#:~:text=Health%2Drelated%20quality%20of%20life%20(HRQoL)%20is%20a%20multi,has%20on%20quality%20of%20life.

HRQOL. CDC. Accessed November 4, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/concept.htm

Torrance GW. Utility approach to measuring health-related quality of life. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(6):593–603. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90019-1

Ebrahim S. Clinical and public health perspectives and applications of health-related quality of life measurement. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(10):1383–1394. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(95)00116-o

Sources which outlined the clinical signs and symptoms of DS were searched53,54, and summarised to create an original conceptual model which included acute and chronic medical concerns / mental health conditions, activity, behaviour and environment / parent-child factors (Supplemental Table 1). Literature review did not identify any indicator sets specific for DS care55, any DS-specific measures of the major dimensions of health, or DS-specific health instruments.

Expert panels

Twenty-three experts attended (Table 2), discussed the definition of “health”, and gave feedback resulting in iterative adjustments to specific constructs and organization of the syndrome-specific conceptual model of health of individuals with DS. One participant referenced previous study of health-related quality of life in DS31; a second participant referenced other condition-specific HRQOL measures56.

Table 2:

Demographic traits of 23 Experts in Down syndrome included in 3 Expert Panels and Focus Group Participants

| Expert Panels (EP) | ||

|---|---|---|

| EP 1, theme: Medical (N=8) | N | |

|

| ||

| Professional titles | MD | 5 |

| PhD | 2 | |

| Professional Roles | Physician | 6 |

| Psychologist | 1 | |

| Behavior Expert | 1 | |

| Work at a Down syndrome clinic or with patients with Down syndrome | Y, currently Y, in past |

5 3 |

| Director or Founder of a DS or intellectual disability clinic or group | Yes | 6 |

| EP 2, theme: Educational (N=8) | N | |

|

| ||

| Professional roles | Educator | 5 |

| Legal Advocate | 1 | |

| Advocate | 1 | |

| Psychologist | 1 | |

| Work at a Down syndrome clinic or with patients with Down syndrome | Y, currently Y, in past |

5 2 |

| Director or Founder of a DS or intellectual disability clinic or group | Yes | 1 |

| EP 3, theme: Psychosocial (N=7) | N | |

|

| ||

| Professional Roles | Psychologist | 1 |

| Speech and Language Pathologist | 1 | |

| Social Worker | 1 | |

| Genetic Counselor | 1 | |

| Family Support Specialist | 2 | |

| Researcher | 1 | |

| Work at a Down syndrome clinic or with patients with Down syndrome | Yes, currently Yes, in past |

6 1 |

| Director or Founder of a DS or intellectual disability clinic or group | Yes | 3 |

| Focus Groups | N | |

|

| ||

| Persons with Down syndrome in Focus Groups (N=8) | ||

| Age (years) | 13–17 18–21 |

4 4 |

| Sex | Female | 4 |

| Parents in Focus Groups (N=20) | ||

| My child with Down syndrome’s age | 0–5 6–12 13–17 18–21 |

5 4 5 6 |

| My child with Down syndrome’s gender | Female | 10 |

| To what extent does your son or daughter with Down syndrome, in your opinion, have significant health problems? (1=not a problem, 7=very much a problem) | Range: 1–6 Mean: 2.7 Standard Deviation: 1.2 Range: 2–7 Mean: 4.9 Standard Deviation: 1.3 |

|

| To what extent does your son or daughter with Down syndrome, in your opinion, have significant educational / learning difficulties? (1=not a problem, 7=very much a problem) | ||

| Parent Sex | Female | 19 |

| Parent Race | White or Caucasian Black or African American Asian Other |

17 1 1 1 |

| Parent Highest level of education | College or university graduate Master’s degree Doctorate degree |

2 9 6 |

| Parent Employed | Yes No |

12 5 |

| Parent Marital Status | Married Divorced |

16 1 |

| Parent Number of children | Range: 1–6 Mean: 2.8 |

|

| Parent State of Residence | New York Pennsylvania Massachusetts Michigan Maryland Idaho Florida Missouri Kentucky Ohio Utah N/A, International |

3 2 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 |

| Parent combined total household income | Mean: $138,500 Range:$75,000–400,000 |

|

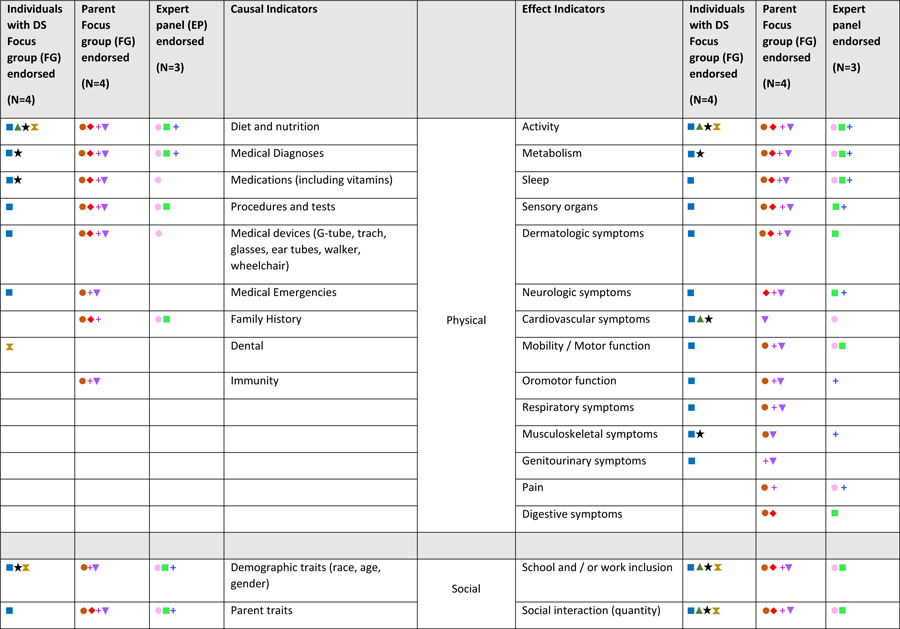

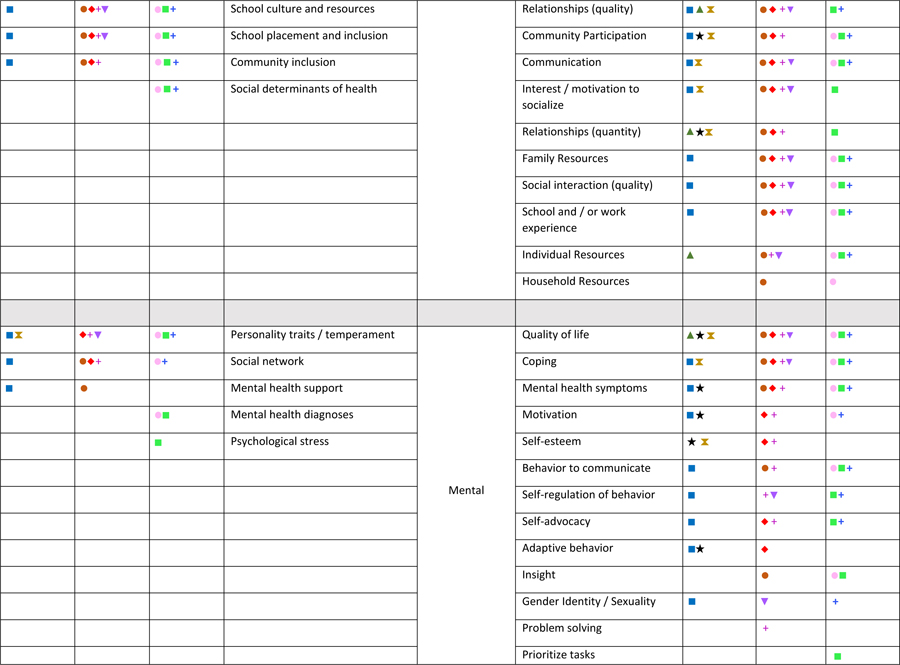

During the expert panels, topics which were discussed were tracked (Table 3). Major themes from review/analysis of EP transcripts emerged (Table 4), and relevant quotes were summarised (Table 5). Some key themes were focused on:

general aspects of the instrument, such as, the need to consider the developmental stages and age of the individual with DS when developing a measure intended to capture health from 0–21 years (Table 4);

general ideas related to the concept of health, such as, the role of meaningful engagement in the community, and what that looks like for a person with DS. Experts gave the example of a person with DS in a theater group and considered how to know someone is involved in the group compared to “going through the motions” and the difference between being an active participant versus a sidelines observer; and the role of family in influencing health: the role that the family plays in creating a healthy lifestyle, the view of the family as a unit, and the role that parental factors (e.g. stress) can have on impacting their children and their children’s health. In EP1 and EP3, experts asked who would be answering the questions in the survey (self-report from person with DS or proxy-report from parent). There was subsequent discussion about which topics might result in different or similar responses between parents and individuals with DS.

Specific comments about constructs in the model, such as, the ability to complete ADLs, daily skills (both cognitively and physically) as signs of health which we have coded in “Activity”; and items which might be missing from the model such as, sexuality and expression of that and gender identity.

Table 3:

Causal and Effect Indicators in the Conceptual Model of Health in Down Syndrome

|

|

Each “+” indicates one focus group or expert panel during which the topic was discussed

Color coding:

Table 4:

Key Themes, Lessons Learned from Expert Panels

| Key Themes | Lessons Learned | Example Quote | Discussed in: | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Information regarding instrument | EP1 | EP2 | EP3 | ||

| Multi-dimensional health model |

|

“I think the focus on these three parts of health is very important”- EP2, S5 “[He] defines health as feeling whole, and talks about how you can be healthy even if you have a disease present. And… that you can heal even if you’re not getting rid of an underlying condition. …But a person can still feel whole and healthy.”- EP2, S4 “Health is a much broader set of things that may encompass your family and where you live and what you eat and when you exercise and a lot of things” – EP1, S5 |

+ | + | |

| Respondent - Self vs proxy |

|

“The young adult might say, “Oh. I’ve got lots of energy and I feel completely fine with what I’m doing,” and the parents saying, “You’re a couch potato.” So how those things-- same activity level, two different perspectives.”- EP1, S3 “For this section there probably needs to be a bigger distinction of who’s reporting, and maybe very separate questions for, “Is this the individual answering these questions or the parent answering these questions?” So yeah, especially I feel for the mental health, it just could be very-- it could be perceived very differently.- EP1, S6 “But [the teacher] had just assumed, “Well, I would be miserable if I couldn’t do XYZ.” But she’s not. There’s no school avoidance. There’s nothing to indicate that she’s not happy being here. She’s not crying, she’s not running away, she’s not under the table. So I think you do have to be careful with where some of the information is coming from and really carefully balance it.- EP2, S3 “We’ll have a patient say something that’s sort of either incongruent with their affect, and then the parent will be sitting side by side and sort of shaking their head, waiting for them to finish politely. And then all of a sudden the parent will sort of delicately navigate trying to validate what they’re feeling, but also say what they said wasn’t really what’s happening, I guess. That it’s not the full picture.”- EP3, S6 “…that self-report might be dependent just on that day for someone.”- EP2, S7 “Sometimes when parents report, we look at their life through our own eyes like, “What would make me happy?” And sitting in a room doing this repetitive activity would not make me happy, but he is actually happy doing that.”- EP2, S5 “But at the younger ages sometimes it is in terms of being able to identify emotions and label them and then be able to advocate to another person what it is that you’re feeling. And then there’s also as you get older your ability to advocate or communicate with a peer versus with an adult. Those are often different.”- EP2, S3 |

+ | + | + |

| Time / reference period of instrument |

|

“I wouldn’t focus on, necessarily, the diagnoses because I can have anxiety but it’s well managed. It’s more like, “What are my current sort of symptoms that are causing me ill health?”- EP1, S3 “-- I think, change from baseline, is a really important way to kind of think about it, too, because everyone has their own sense of what their health looks like.”- EP3, S4 “We know that a lot of times individuals with this profile tend to be very in the moment and will report on kind of how they’re doing right at that time, which especially if in a doctor’s office, might not be reflective of how they’re doing day to day.”- EP3, S4 |

+ | ||

| Use of the instrument |

|

“One, if you’re looking at it just for research to get a static measure of health outcomes, yes, you want to know if somebody has more of these [inaudible] contributors. But then if you’re looking at change over time for clinical trial, then I don’t know if any of these would actually change over time. So you might want to look. It sort of impacts-- it just impacts how you look at the domains, how you develop the items, and then how you put them into the measure.”- EP1, S3 | + | + | |

| Individual views |

|

“She is who she is and we’ll measure her against her own personal growth.”- EP2, S3 “It depends really whether fundamentally there is one concept of wellness or whether a different person has their own concept of wellness and really whether you’re trying to tap into whether that has changed or not I think?[…] Are you wanting to know that they’re in their own sense of wellness that the sense of wellness is better than it used to be or not or are you really going to be able to compare two very different people’s worlds with the same measure?”- EP1, S9 “I mean, if I were a marathon runner, I’d be in really, really bad shape right now, but if I was comparing myself to somebody who’s morbidly obese, I’d be in great shape, so it’s very much, a kind of a continuum, and it’s based on what your expectations of yourself are, I think.”- EP3, S5 |

+ | + | + |

| Context in Family – intersection of child health and family health |

|

“So family health, how the family are coping, and this is not easy to see how you pick up all these measures easily. But something around how parents report their own health, their own situation, and how they feel and their mood and whether they participate in the community and feel they have support. There’s things around all of that that are definitely going to impact on the health of their children.”- EP2, S1 “What’s happening within the family, family resources, etc. and how that could impact the individual but perhaps causing them loss of sleep, so loss of sleep is going to cause more problems for an individual including fatigue, etc. so it’s hard to know which way that goes …and somebody’s health could actually have quite an impact on the family dynamic and family functionality.”- EP2, S6 “If there’s poor family dynamic, it’s probably impacting the other children in the family as well, with or without a child with Down syndrome.”- EP2, S5 |

+ | ||

| Context in Culture |

|

“Culture plays a bit into this too because in some cultures, you’re not supposed to tell that you’re not feeling well.”- EP2, S9 | + | + | |

| Context within Down syndrome |

|

“For me, the definition of health for a child with Down syndrome would be the same as the definition of health for anybody else.”- EP2, S1 “There is certainly health issues that are different for people with Down syndrome and things that you have to be on the lookout for.”- EP2, S5 |

+ | + | |

| General information regarding conceptual model | |||||

| Looking past diagnosis: From Medical to Symptoms / impact that person would perceive |

|

“As a psychiatrist, I wouldn’t be measuring too much about diagnosis. I don’t think that they’re so reliable. And I think that a lot of the questions can do a better job of sort of tapping into symptoms and factors and things rather than diagnosis.”- EP1, S9 “Between what you’re all saying about something that might be a list on paper and people going from that to making assumptions, where actually, what you need to do is observe, observe how the child engages, observe how they might be able to be engaged in sports and so on. It’s actually observing the child’s behaviors.”- EP2, S1 “Very often, people get a mindset the child’s like this because they have Down Syndrome. Not that this is something eminently changeable.”- EP1, S1 |

+ | + | |

| Motivation / desire |

|

“I think about kind of comfort, both with regard to the absence of physical pain, and obviously, you want to be physically active without [pain]. I think just the comfort, both, I guess, from a physical perspective, but also from a mental health perspective-- the absence of stress, but also the presence of pleasure and interests and desires and motivation.- EP3, S4 | + | ||

| Setting: Social interaction in classroom |

|

“So I think for the older population, the community participation, socialization, relationships all look very different if they don’t have support staff.”- EP3, S7 “Is it the child’s or is the environment? Because I remember being told my son was non-compliant in kindergarten because in centers, he would just sit down and not do anything and she’d say-- And I don’t understand it because he’s got all these choices. And I said, “Yeah. Well, he’s got all these choices. He’s totally overwhelmed. Give him two choices.” So that’s not non-compliance. That’s the environment being—overstimulating. …And so to tease that out from these reports is also important because otherwise, we’re trying to fix this kid when really the kid is not the issue.”- EP2, S5 |

+ | ||

| Setting: School, and Mental health in the classroom |

|

“If you’re including up to age 22 then you’re really capturing an age range of people who are just approaching that major change as they age out of school district services…. It seems like there’s huge variability who gets pulled out of that regular classroom and at what age.”- EP1, S8 | + | + | |

| Opportunities |

|

“I work in an urban school district where a lot of families that were in poverty. And I had the programs that had a lot of children with Down syndrome and …the number of families that I found that were not connected to anybody and didn’t access or hadn’t seen a developmental pediatrician were astounding.”- EP2, S3 “So I guess what I’m trying to say is that appropriateness [of placement] depends on how you’re defining it- EP2, S5 “Kids who have general ed have a higher likelihood of being successful and employed as adults, which, overall, is going to give you better health and social opportunities as adults.”- EP2, S3 “I think one thing that just first comes to mind is first just having kind of your basic needs taken care of. That you have enough resources available to you. That you are able to do things like eat healthy and exercise and have leisure time and things like that. Kind of having that basic level of kind of thinking of the socioeconomic factors you were talking about. I think that does have a big impact on health, being able to access or have fewer barriers to those type of healthy behaviors.”- EP3, S3 “And services are widely different across the country and the state. If you have a really good advocate, someone that knows the system and knows how to advocate well, that person’s health may look much better than somebody who doesn’t know how to advocate or know how to fight for the things that they need to fight for. So we see a wildly different range of healthcare being provided based on advocacy.”- EP3, S7 “I guess what I’m saying also is that we shouldn’t fault somebody for not participating in something until we know that it’s available to them. It’s not that they’re not doing it, it’s that they can’t do it.”- EP3, S1 |

+ | + | |

| Communication |

|

“But there’s different ways of communicating and are they able to use the different ways of communicating and are they able to use all the different ways of communication? Well, some students might use a device to communicate. They might use text, they might use verbal, they might use signs, they might use-- So I feel like if you have social health and you’re looking at these relationships and stuff, can they use their communication to have opportunities and to build those relationships?”- EP2, S7 | + | + | |

| Interconnections between dimensions |

|

“Language is very different. So language, we would have neurological as far as the brain functioning, and it would go into cognitive to mental health and also to social health. So it’d be different, but speech would fit in more, I think, with physical health. And I think one of the difficulties that families encounter is that the education system and speech-language pathologists don’t distinguish between those.”- EP3, S1 “Can you get where you need to go, for example? Are there transportation barriers? Maybe it’s not mobility in the sense of the actual person. I don’t know. Are there barriers to obtaining adaptive equipment? I’m just sort of thinking. Are there barriers within the system based on the psychosocial situation?”- EP3, S6 |

+ | + | |

Table 5:

Key Quotes from Expert Panels by Dimension

| Physical Health | Mental Health | Social Health |

|---|---|---|

| “Can the child see properly?” “Can they hear properly?” “Are they in pain?” Because you cannot function unless you’ve got that basic physical health sorted out. So I don’t think we should just drift too far from that. Those things matter as a baseline and a starting point for you to be able to participate.- EP2, S1 “I look at other people -- who are physically healthy but are struggling significantly.”- EP2, S3 “Maybe somebody who has something relatively minor, in terms of what you would think would impact their functionality, but it has a much bigger impact on them, and not making assumptions based on that list of conditions about a person.”- EP2, S5 “But there’s just this tendency to look at the list or look at the IQ score, or whatever it may be, and just make these presumptions about what a student can and cannot do, and whether they can and cannot be educated, and that impacts everything about their life.”- EP2, S5 “My model of being healthy is basic physical health, and that you can participate in the world.”- EP2, S1 “Somebody could report they’re feeling good when they are grossly overweight. Not eating a healthy diet. So where does the very basic stuff like how tall is this person and how much do they weigh come into this?”- EP2, S1 “How is the digestive system functioning, because that can be a big part of wellbeing.”- EP2, S4 “This reminds me of the little list that I go through every time I hit up the neurology office with my daughter, and it lists every system in your body.”- EP2, S3 |

“To the degree that a lot of your mental well-being comes from interactions with other people, the ability to find new and different ways to interact is very important. Right?”- EP1, S5 “For the mental well-being, what are the struggles for this family, for the caregiver, and what are the struggles for the child?”- EP1, S7 “Not everybody has that survivor mentality, has that coping mechanism innately in them, without it being really specifically taught how to cope in certain stressful situations”- EP2, S3 “I think two of the subtopics that come out of the coping, in my experience, with other friends with Down syndrome is they are resilient regardless of what we prompt them to do. And they have empathy regardless of what we prompted them to do. But managing emotions and maybe some adaptive behaviors need some prompting. So the two that stick out is independent to me for coping would be resiliency and empathy.”- EP3, S7 “Where does things like play fit into mental health? So, I mean, we all have to have recreation, and that’s important for our mental health.”- EP3, S4 “The level of self-fulfillment and having a meaningful day in life is really a person-centered theory. And it controls one moods and identifies moods in other people.” - EP3, S7 “Self-determination. It’s your level of choice in life. [if you’re] happy with the choices that you have available.”- EP2, S3 “Another big, another big one is affect, right? So how often are they smiling? Do they look happy? Do they look sad? Do they look anxious? Just a visible affect. And if it’s congruent with how their mood actually is.”- EP4, S4 |

“You might have two people and neither of them have kind of a social group. But one of them might have the opportunity to but can’t because of their health, and the other might not have the opportunity. And so I think that sort of opportunity is going to be a big thing to try and tease out because there’s a world of difference between people in those two situations.”- EP1, S9 “It would be hard to tell what part of the social health-- there’s no way to separate the opportunities from the social health.”- EP2, S4 “One thing that we struggle with is when a lot of our adult patients age out of school, many of them just end up hanging out, and it’s a tough transition. We see a lot of issues during those first few years, weight gain, we see a lot of mental health, and kind of social stuff. I mean, they don’t have anything to do. So I think it is a structural issue that has very real effects on individuals.”- EP1, S6 |

Focus groups

Adolescents with DS age 13–21 years, and their parents participated (Table 2). Most parents were mothers; all were the primary caregiver of sons / daughters age 0–21 years, and most lived with their son / daughter with DS (Table 2). Discussion focused on the meaning of “physical health”, “social health” and “mental health”, with feedback from parents and iterative refinement to the model. Parents identified unique aspects of health for their children with DS to be incorporated into the model. Relevant quotes by construct were summarised (Table 6); adolescents and young adults with DS contributed input into the conceptual model of health.

Table 6:

Additional Example quotes of constructs from Focus Groups (FGs) and Expert Panels (EPs)

| Code | Topic | Example quote |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Health | ||

| Neurologic | Seizures, infantile spasms | “I don’t know if anybody else’s children have had the infantile spasms which-- it’s pretty scary. But we got them under control quickly.” S6, FG8 |

| Dermatologic | Skin “break outs” and pimples, alopecia, very dry skin | “He has the typical some things, very dry skin, some skin problems..” S3, FG7 |

| Musculoskeletal | Strength, fitness, low muscle tone | “She’s good on the monkey bars but she fatigues easier because of low tone.” S2, FG8 |

| Cardiac | Congenital heart disease, heart murmur, arrhythmia, pulmonary hypertension, need for surgery, need for pacemaker | “I think about my son’s heart. I mean he’s never had surgery. Knock on wood. But he does have two ASDs.” S2, FG1 |

| Respiratory | Colds, bronchitis, pneumonia, RSV, asthma, narrow airways | “He was hospitalized four times last year with respiratory illnesses. So if he gets a really bad cold or something, then he doesn’t seem to fight it as well.” S4, FG1 |

| Genitourinary | Chronic renal failure, toilet training | “Four years ago, he was diagnosed with chronic renal failure, which was completely out of the blue, no warning whatsoever.” S7, FG7 |

| Digestive | Constipation, celiac disease, duodenal atresia | “[I know he’s healthy] If he’s having regular bowel movements, if he’s eating good.” S4, FG1 |

| Sensory Organs | Vision concerns, hearing loss, cholesteatomas, need for glasses, need for ear tubes, need for hearing aid, recurrent ear infections | “She’s periodically on an antibiotic for her ears, so drainage is an issue and making sure that her hearing’s good.” S7, FG8 |

| Endocrine | Hypothyroidism | “About two years ago, she was diagnosed with hypothyroidism. And so she’s now taking a hormone supplement to address that.” S6, FG7 |

| Metabolism | Overweight, failure to thrive, glucose issues, type 1 diabetes, fatigue | “I think my son is in good health, but he has put on about 19 pounds since the pandemic started. …. So I’m not feeling he’s so healthy anymore.”S3, FG7 |

| Activity | Ability to and frequency of exercise | “We try to make sure to work in activity, both because of the long term value and because we find that it helps with some of [her] stimming and other behaviors.” S4,FG8 |

| Mobility | Slowing down, sitting up / milestones, strength, balance | “He’s not able to sit up yet. He still has low muscle tone.” S5, FG1 |

| Sleep | Sleep apnea, getting “a good night’s” sleep, napping | “I think of a healthy day being I really put an emphasis on a good night’s sleep . . . .” S2, FG8 |

| Oromotor | Picky eating; difficulties with breastfeeding, chewing or swallowing; need for gastrostomy tube | “He really needs crunchy stuff because of texture and low tone...he also needs a lot of flavor. But he’s very picky.” S2, FG1 |

| Pain | Ear pain with ear infections, high pain tolerance | “She has very high pain tolerance. So if she’s not feeling well and she actually tells me she’s not feeling well, it’s pretty bad.” S6, FG 7 |

| Other physical | Dental health | “Dental health issues can come quickly if there is a problem.” FG1 |

| Other physical | Medical issues which are not associated with, or more prevalent, in Down syndrome | “His three fingers were fused together, so that was six surgeries there too.” FG8 |

| Mental Health | ||

| Quality of life | Feeling pleasure/happiness, sense of self-fulfillment, feeling welcomed and socially accepted | “One comment is that people in wheelchairs, they may not be able to move around very well, but they still have a quality of life. So I think it’s an individual thing. It takes in the consideration of mental health, social health, if you will, also how we feel about getting around in the sense of doing things within our environment. So it’s not just what we would consider healthy. It’s how they function and how they feel about that.”- EP1, S2 |

| Mood / affect | Receptiveness to learning new skills and facing challenges; regulating mood; ability to recognize and communicate about one’s emotions | “If something doesn’t go with her, align with her, she would cry instantly. I could see tears in half a second.” S5, FG7 “I guess I can tell when she’s happy by the absence of behaviors and stuff that she does when she’s unhappy or feeling isolated.” S7, FG1 |

| Identity | Pride from ability to set and reach goals; personality/sense of humor; emerging sexuality | “I want to be a gamer. That’s how the world makes money.” S5, FG4 “And I think she was pretending with me and not trying to trick me but using this little sense of humor. It was the first time that I had really seen her do that. S2, FG8 |

| Coping | Maintaining health-related routines; being able to manage change/disruptions to routines; developing healthy coping mechanisms | “She doesn’t take rejection. If she calls a friend or looks to get somebody to do something and they say no, she just moves on to the next one. I mean, it’s like she has better resilience skills than I do when it comes to social rejection / interaction.” S4, FG6 “Even though you think that maybe he is not engaged in what’s going on or he’s doing his own thing, you’ll hear him talk about it later or he’ll be processing it later, after the fact.” “Sometimes [he] will just say, “Oh, well,” about things. I’m not sure it’s resilience or just, “Oh, well.” I don’t know. I don’t know what the difference would be for him.” |

| Behavior | Using behavior to indicate and cope with feelings; engaging in self-soothing or self-protective behaviors | “If he tells me no and he doesn’t want to do that, that’s one of the signs, to me, that there’s something going on, things he would normally do.” |

| Neurodevelopmental | Learning; independence (including planning and problem-solving skills); developmental progress (including need for therapies) | “Children who are more delayed or have less communication are more likely to have difficult behaviors, more likely to have bad sleep happen.”- EP2, S1 “Level of intellectual impairment likely informs a lot of how well especially a lot of the topics in this mental health section which what I was alluding to before as far as self-awareness and expression of awareness and expression of emotions and all those types of concepts.”- EP3, S4 “Probably having our specialty services - so speech, OTPT - being regular parts of their programming. So that might be another kind of big-picture way to quantify, either by frequency, or just that they have access at all.”- EP3, S4 |

| Language | Expressive and receptive language including vocabulary and articulation; use of sign language | “And she’s not able to express, so she’s like a hidden volcano.” S5, FG7 |

| Alertness | - | |

| Other Mental | - | |

| Social Health | ||

| Resources and Opportunities | Access to transportation; access to healthcare and insurance coverage, including knowledgeable pediatricians, specialists, and therapists; safe living situation; access to social support such as relatives nearby and parent support groups; availability of social activities and educational supports | “There’s really no time in history ever to be a person with a disability than now.…I just think there’s so much that these children can do and become. So if we can give them the right tools, if we can mainstream them-- and so I’m really hopeful about what my son will be able to do.” -S2, FG1 |

| School / work | Having friends and building relationships at school; participating in enrichment activities at school; inclusion with neurotypical peers including school ‘mainstreaming’ | “What makes our life important? And having activities that allows us to connect and develop some kind of friendships and things like that, that seems to be the key to social for me. I don’t know, but I think the other dimensions-- they’re really important. School districts, stuff like that, but still, how much accessibility they have to different social environments and stuff. That would help.”- EP1,S4 |

| Community participation | Participating in community activities (through peer groups, hobbies, sports, etc.); Going out to places in community (e.g., park, grocery store); Positive impact of diverse communities | “You’ll get very different answers to some of these. They do great at school with peers but they don’t see them outside of school. They do great with structure at school but maybe not at home.”- EP1, S3 |

| Socialization | Opportunities to engage with friends, family, and other people in the community either in-person or using technology (i.e. phones, iPad, or social media); avoiding isolation | “Community safety. The absence of significant stressors and trauma.”- EP3, S6 |

| Relationships | Having meaningful relationships with family members; being able to develop close friendships with and feel included by people | “He tries to mirror them [his siblings] sometimes. And he sees them doing stuff. And he wants to try to do it. So I do think it’s been super helpful.” -S4, FG1] |

| Other social | Overscheduling / time limitations; prioritizing / age-based differences | “Because doing something for 10 minutes for anybody who’s age three is really sketchy at best, because they’re three and they’re just learning how to attend to anything for any amount of time. So that 10-minute benchmark makes sense for someone maybe at a certain age, but not so much for someone who’s 8.- EP2, S8 |

Common Conceptual Model Themes from EPs and FGs

Multi-dimensional:

Expert panelists supported including the WHO dimensions of physical, social, and mental well-being when reviewing the conceptual model. FG participants identified specific components (constructs) of these dimensions when asked to describe the meaning of health. Experts and parents agreed that individuals with DS have unique health characteristics which may impact most children with DS but not children without DS, such as: behavioural concerns, mental health concerns, unique medical needs, and school supports. Among the topics discussed, a holistic model of health with all health dimensions was supported by participants.

Multi-construct:

Among the constructs in our proposed conceptual model, nearly all were identified by participants as an indicator of health (Table 4), and as our model expanded, there are many concepts that were introduced by persons with DS and caregivers that were not endorsed by the expert panels. Although weight was coded in the category “metabolism”, the topic “healthy eating / food choices” was not in the original conceptual model yet was independently identified by all the FG and EP participants. Both FGs and EPs discussed the value of healthy food to manage medical issues (such as thyroid issues, and type 1 diabetes). Parents discussed both the aspect of eating nutritious foods, and the awareness of what a “healthy” or “good” food choice is. Additionally, EP members discussed access to healthy food options and their higher costs, highlighting the interplay between physical and social dimensions of health. Impaired immunity, referring to decreased immune function, or a common cold lasting longer, was discussed in 3 FGs; dental care was identified as important to health in 2 FGs. These three concepts were categorised as causal indicators of physical health and added to our final model.

Effect indicators:

The physical health effect indicator topics most often identified by both experts and parents or individuals with DS were: activity (in 8 FGs and 3 EPs), metabolism (in 6 FGs and 3 EPs), sleep (in 5 FGs and 3 EPs), and sensory organs (in 5 FGs and 2 EPs). The social health effect indicator topics most often identified were: school and / or work inclusion (in 8 FGs and 2 EPs), quantity of social interaction (in 8 FGs and 2 EPs), and quality of relationships (in 7 FGs and 2 EPs). The mental health effect indicator topics most often identified were: quality of life (in 7 FGs and 3 EPs), coping (in 6 FGs and 3 EPs), and mental health symptoms (in 5 FGs and 3 EPs; Table 4).

Causal indicators:

Topics related to health which were identified and grouped by the authors as causal indicators of health were also multi-dimensional. The causal indicators of physical health most often identified were: medical diagnoses (in 6 FGs and 3 EPs) and medications including vitamins (in 6 FGs and 1 EP). The social health causal indicators most often identified were: demographic traits (in 6 FGs and 3 EPs) and parent traits (in 5 FGs and 3 EPs). The most common identified causal indicators of mental health were: personality traits or temperament (in 5 FGs and 3 EPs) and social network (in 4 FGs and 2 EPs).

Relevance to Down syndrome:

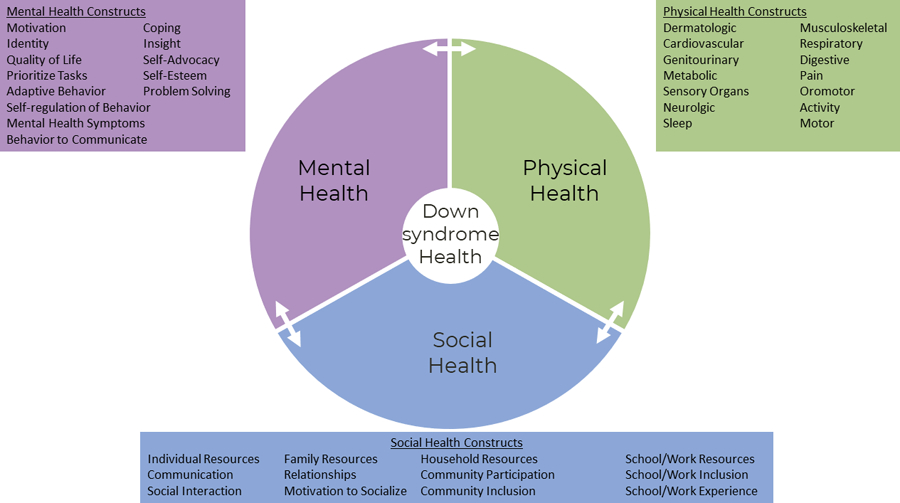

Parents and experts often focused on aspects of health which are more prevalent in individuals with DS. For example, hearing and vision issues are two prevalent co-occurring medical conditions and impact 60–75% of children and adolescents with DS53,57. Appropriately, 63% of FGs and 67% EPs identified the corresponding code “sensory organs” as an indicator of health. Participants also identified “sleep” as an important indicator of health; prevalence of sleep apnea is increased for children with DS. A final conceptual model was visualised (Figure 1), with 3 dimensions, their relevant constructs and relationships (Table 3).

Figure 1:

Conceptual model of health in Down syndrome with interconnection among physical, mental, and social dimensions

Discussion

Health is a complex concept52; individuals with DS have a unique medical and psychological profile. Existing health-related definitions, conceptual models of health, and indicators of health informed components of our model. We found a number of definitions of health from unique perspectives and chose the WHO health definition based on its holistic view of health as a concept, rather than a disease-based model, though more comprehensive review using other search terms could be conducted in the future. Choosing the WHO definition of health, we began with the three dimensions of physical, social, and mental well-being; these were supported by EP and FG participants. Additional concepts were incorporated into our final conceptual model (Figure 1). In our search for signs and symptoms of health, we identified some manuscripts which describe existing instruments measuring components of our draft conceptual model based on WHO constructs, which we summarised (Supplemental Table 3).

Although general health measures exist, we have previously described some limitations in using global health measures from parents of individuals with DS.26 In further support of our hypothesis, in this study, experts and parents both endorsed a syndrome-specific model to capture health in DS. Experts and parents identified the unique traits of DS necessitating a syndrome-specific health model. For example, given the prevalence of autoimmune conditions59, and increased risk for respiratory infections60 seen in individuals with DS, parents emphasised immunity in a conceptual model of health, which would not be as relevant to individuals without DS. Although general population measures have been validated in individuals with DS61, and general populations health-related measures have been administered to parents of individuals with DS36; no syndrome-specific health-related instrument has been validated for DS to-date. Our results support the need for a syndrome-specific measure of health in DS to be developed in order to accurately capture health.

Our participants identified important topics within the conceptual model. Experts discussed the nuances of developing an instrument, and the need to consider developmental stages, the meaning of social / community engagement, the role of family and parents in influencing health, and that responses would differ depending on who completed the survey. In categorizing concepts, the research team discussed the complex interaction of causal and effect indicators, and the focus group participants discussed the interconnections of one topic, “healthy foods”, in more than one dimension of health.

In the future, we aim to develop our conceptual model into a measurement model, an item pool, and, ultimately, a syndrome-specific measure of health in DS. The development of syndrome-specific conceptual models and ongoing work to evaluate the definition of health in unique patient populations is the first step to allowing for creation of syndrome-specific instruments and syndrome-specific patient-reported outcome measures. Our model is a conceptualization of health based on our current studies, has changed over the course of our research, and may continue to be refined with future research over time.

Our study may have selection bias, preventing our results from generalising to the experience of all experts, parents, and individuals with DS. Although we recruited from a national contact source, future study with increased diversity, broader age ranges, and broader recruitment strategies could all increase generalisability. We conducted our study during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have impacted the discussion given the overarching impacts of this pandemic; parents might be viewing health in the present, or might be reflecting on health prior to the pandemic. In fact, parents’ discussion of the COVID-19 pandemic on health, such as: attention to respiratory infections and fevers, changes in social interactions, and worry about impact on development and learning, will be an important topic for future research.

Genetic syndromes which have a different medical and psychological profile may need new concepts or different ranking of codes, but could use our EP and FG methodology as a framework. For example, for patients with Prader-Willi syndrome, hyperphagia and food-related behaviour, or anxiety symptoms62 might be important constructs in “mental health symptoms”, or in Neurofibromatosis type 1, neurofibromas and seizures63 might drive “neurologic” to be an important indicator of health. Once we are able to measure health, we will be better able to evaluate the current state of health, and work to improve the health of patients with DS, and eventually, other genetic syndromes.

Conclusion

Experts, teens with DS, and parents of children with DS endorsed a conceptual model of health with three dimensions of physical, social, and mental well-being, described unique concerns for people with DS, and detailed dimension-specific constructs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Thanks are given to the patients and families in the MGH Down Syndrome Program for their participation in this, and other, research projects as well as the experts who attended our panels. Appreciation is given to the groups that assisted with recruitment posting: Massachusetts Down Syndrome Congress and LuMind IDSC Down Syndrome Foundation. The authors also acknowledge the contribution of DS-Connect® (The Down Syndrome Registry) which is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), NIH, for the study recruitment used in this manuscript.

Funding statement

Funding for all or a component of this work is provided by the National Institutes of Health – grant K23 HD100568 (PI=Santoro).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: SLS has received research funding from LuMind IDSC Down Syndrome Foundation to conduct clinical trials for people with DS within the past two years. She serves in a non-paid capacity on the Medical and Scientific Advisory Council of the Massachusetts Down Syndrome Congress, the Board of Directors of the Down Syndrome Medical Interest Group (DSMIG-USA), and the Executive Committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Genetics.

BGS occasionally consults on the topic of DS through Gerson Lehrman Group. He receives remuneration from DS non-profit organizations for speaking engagements and associated travel expenses. Dr. Skotko receives annual royalties from Woodbine House, Inc., for the publication of his book, Fasten Your Seatbelt: A Crash Course on Down Syndrome for Brothers and Sisters. Within the past two years, he has received research funding from F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Inc., AC Immune, and LuMind IDSC Down Syndrome Foundation to conduct clinical trials for people with DS. Dr. Skotko is occasionally asked to serve as an expert witness for legal cases where DS is discussed. Dr. Skotko serves in a non-paid capacity on the Honorary Board of Directors for the Massachusetts Down Syndrome Congress and the Professional Advisory Committee for the National Center for Prenatal and Postnatal Down Syndrome Resources. Dr. Skotko has a sister with DS.

The other authors do not have any conflicts to disclose.

Ethics approval statement: The MassGeneral Brigham institutional review board approved this study.

Patient consent statement if any: All participants expressed verbal consent to participate in this research study at the beginning of the expert panels or focus groups.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources if any – N/A

Data availability statement:

The de-identified, aggregate data from this study are available upon reasonable request, but recordings and transcriptions are not available as participants did not consent to this.

References

- 1.Koh HK, Blakey CR, Roper AY. Healthy People 2020: a report card on the health of the nation. JAMA 2014;311(24):2475–2476. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forrest CB, Tucker CA, Ravens-Sieberer U, et al. Concurrent validity of the PROMIS® pediatric global health measure. Qual Life Res 2016;25(3):739–751. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1111-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Cox FM, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of the Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. Eur Respir J 1999;14(1):32–38. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a08.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nanigian DK, Nguyen T, Tanaka ST, Cambio A, DiGrande A, Kurzrock EA. Development and validation of the fecal incontinence and constipation quality of life measure in children with spina bifida. J Urol 2008;180(4 Suppl):1770–1773; discussion 1773. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Modi AC, Junger KF, Mara CA, et al. Validation of the PedsQL Epilepsy Module: A pediatric epilepsy-specific health-related quality of life measure. Epilepsia 2017;58(11):1920–1930. doi: 10.1111/epi.13875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solans M, Pane S, Estrada MD, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life Measurement in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Generic and Disease-Specific Instruments. Value in Health 2008;11(4):742–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00293.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walton K, Krahn GL, Buck A, et al. Putting “ME” into measurement: Adapting self-report health measures for use with individuals with intellectual disability. Res Dev Disabil 2022;128:104298. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2022.104298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mindham J, Espie CA. Glasgow Anxiety Scale for people with an Intellectual Disability (GAS-ID): development and psychometric properties of a new measure for use with people with mild intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res 2003;47(Pt 1):22–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00457.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuthill FM, Espie CA, Cooper SA. Development and psychometric properties of the Glasgow Depression Scale for people with a Learning Disability. Individual and carer supplement versions. Br J Psychiatry 2003;182:347–353. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.4.347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wigham S, Hatton C, Taylor JL. The Lancaster and Northgate Trauma Scales (LANTS): the development and psychometric properties of a measure of trauma for people with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities. Res Dev Disabil 2011;32(6):2651–2659. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korenberg JR, Chen XN, Schipper R, et al. Down syndrome phenotypes: the consequences of chromosomal imbalance. PNAS 1994;91(11):4997–5001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basil JS, Santoro SL, Martin LJ, Healy KW, Chini BA, Saal HM. Retrospective Study of Obesity in Children with Down Syndrome. The Journal of Pediatrics 2016;173:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.02.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bertapelli F, Pitetti K, Agiovlasitis S, Guerra-Junior G. Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents with Down syndrome—prevalence, determinants, consequences, and interventions: A literature review. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2016;57:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith BA, Ulrich BD. Early onset of stabilizing strategies for gait and obstacles: older adults with Down syndrome. Gait Posture 2008;28(3):448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2008.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CCJJ Ringenbach SDR. Walking performance in adolescents and young adults with Down syndrome: the role of obesity and sleep problems. J Intellect Disabil Res 2018;62(4):339–348. doi: 10.1111/jir.12474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palumbo ML, McDougle CJ. Pharmacotherapy of Down syndrome. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 2018;19(17):1875–1889. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2018.1529167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hithersay R, Startin CM, Hamburg S, et al. Association of Dementia With Mortality Among Adults With Down Syndrome Older Than 35 Years. JAMA Neurology Published online November 19, 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.3616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rafii MS, Santoro SL. Prevalence and Severity of Alzheimer Disease in Individuals With Down Syndrome. JAMA Neurol Published online November 19, 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.3443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esbensen AJ. Health conditions associated with aging and end of life of adults with Down syndrome. Int Rev Res Ment Retard 2010;39(C):107–126. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7750(10)39004-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ylä-Herttuala S, Luoma J, Nikkari T, Kivimäki T. Down’s syndrome and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 1989;76(2–3):269–272. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(89)90110-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasle H, Friedman JM, Olsen JH, Rasmussen SA. Low risk of solid tumors in persons with Down syndrome. Genet Med 2016;18(11):1151–1157. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthews TJ, Allain DC, Matthews AL, Mitchell A, Santoro SL, Cohen L. An assessment of health, social, communication, and daily living skills of adults with Down syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 2018;176(6):1389–1397. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Graaf G, Levine SP, Goldstein R, Skotko BG. Parents’ perceptions of functional abilities in people with Down syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A Published online December 24, 2018. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.61004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kageleiry A, Samuelson D, Duh MS, Lefebvre P, Campbell J, Skotko BG. Out-of-pocket medical costs and third-party healthcare costs for children with Down syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 2017;173(3):627–637. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, et al. How should we define health? BMJ 2011;343(jul26 2):d4163–d4163. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santoro SL, Campbell A, Cottrell C, et al. Piloting the use of global health measures in a Down syndrome clinic. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2021;34(4):1108–1117. doi: 10.1111/jar.12866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Vries PJ, Franz DN, Curatolo P, et al. Measuring Health-Related Quality of Life in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex - Psychometric Evaluation of Three Instruments in Individuals With Refractory Epilepsy. Front Pharmacol 2018;9:964. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes D, Giugliani R, Guffon N, et al. Clinical outcomes in a subpopulation of adults with Morquio A syndrome: results from a long-term extension study of elosulfase alfa. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017;12(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0634-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rafii MS. Improving Memory and Cognition in Individuals with Down Syndrome. CNS Drugs 2016;30(7):567–573. doi: 10.1007/s40263-016-0353-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacola LM, Hickey F, Howe SR, Esbensen A, Shear PK. Behavior and adaptive functioning in adolescents with Down syndrome: specifying targets for intervention. J Ment Health Res Intellect Disabil 2014;7(4):287–305. doi: 10.1080/19315864.2014.920941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graves RJ, Graff JC, Esbensen AJ, Hathaway DK, Wan JY, Wicks MN. Measuring Health-Related Quality of Life of Adults With Down Syndrome. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil 2016;121(4):312–326. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-121.4.312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santoro SL, Bartman T, Cua CL, Lemle S, Skotko BG. Use of Electronic Health Record Integration for Down Syndrome Guidelines. Pediatrics 2018;142(3):e20174119. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Graaf G, Buckley F, Skotko BG. Estimation of the number of people with Down syndrome in the United States. Genet Med 2017;19(4):439–447. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Q, Rasmussen SA, Friedman JM. Mortality associated with Down’s syndrome in the USA from 1983 to 1997: a population-based study. Lancet 2002;359(9311):1019–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santoro SL, Steffensen EH. Congenital heart disease in Down syndrome – A review of temporal changes. J Congenit Heart Dis 2021;5(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s40949-020-00055-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katsiana A, Strimpakos N, Ioannis V, et al. Health-related Quality of Life in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Children with Down Syndrome. Mater Sociomed 2020;32(2):93–98. doi: 10.5455/msm.2020.32.93-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goeldner C, Kishnani PS, Skotko BG, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial to explore the effects of a GABAA-α5 NAM (basmisanil) on intellectual disability associated with Down syndrome. J Neurodev Disord 2022;14(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s11689-022-09418-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chung J, Donelan K, Macklin EA, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an online health tool about Down syndrome. Genet Med Published online September 3, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-00952-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Health-Related Quality of Life and Well-Being HealthyPeople.gov. Accessed November 4, 2021. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/Health-Related-Quality-of-Life-and-Well-Being#:~:text=Health%2Drelated%20quality%20of%20life%20(HRQoL)%20is%20a%20multi,has%20on%20quality%20of%20life.

- 40.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity--establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1--eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health 2011;14(8):967–977. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.WHO | Constitution of WHO: principles WHO. Accessed December 11, 2018. http://www.who.int/about/mission/en/

- 42.Martikainen P, Bartley M, Lahelma E. Psychosocial determinants of health in social epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31(6):1091–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulz A, Northridge ME. Social determinants of health: implications for environmental health promotion. Health Educ Behav 2004;31(4):455–471. doi: 10.1177/1090198104265598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hosseini Shokouh SM, Arab M, Emamgholipour S, Rashidian A, Montazeri A, Zaboli R. Conceptual Models of Social Determinants of Health: A Narrative Review. Iran J Public Health 2017;46(4):435–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Exworthy M Policy to tackle the social determinants of health: using conceptual models to understand the policy process. Health Policy and Planning 2008;23(5):318–327. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fayers PM, Hand DJ. Causal variables, indicator variables and measurement scales: an example from quality of life. J Royal Statistical Soc A 2002;165(2):233–253. doi: 10.1111/1467-985X.02020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grey literature and their sources https://s4be.cochrane.org/blog/2021/05/07/grey-literature-and-their-sources/