Abstract

Background

This Bayesian network meta-regression analysis provides a head-to-head comparison of first-line therapeutic immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) combinations for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) using median follow-up time as covariate.

Methods

We searched Six databases for a comprehensive analysis of randomised clinical trials (RCTs). Comparing progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of different interventions at the same time node by Bayesian network meta-analysis. Bayesian network meta-regression analysis was performed on objective response rate (ORR), adverse events (AEs) (grade ≥ 3) and the hazard ratios (HR) associated with PFS and OS, with the median follow-up time as the covariate.

Results

Eventually a total of 22 RCTs reporting 11,090 patients with 19 interventions. Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab (LenPem) shows dominance of PFS, and Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib (PemAxi) shows superiority in OS at each time point. After meta-regression analysis, for HRs of PFS, LenPem shows advantages; for HRs of OS, PemAxi shows superiority; For ORR, LenPem provides better results. For AEs (grade ≥ 3), Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab (AtezoBev) is better.

Conclusion

Considering the lower toxicity and the higher quality of life, PemAxi should be recommended as the optimal therapy in treating mRCC.

Systematic review registration

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD4202236775.

Keywords: metastatic renal cell carcinoma, network meta-regression analysis, immune checkpoint inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, efficacy

1. Introduction

According to the latest statistics, renal cancer is the sixth most common malignant tumor in men and the ninth in women. It is estimated that 79,000 new diagnoses will be determined in the United States in 2022, resulting in 13,920 deaths (1). Among them, 80% are renal cell carcinoma (RCC) (2). In the past 20 years, the incidence rate of RCC has continued to rise (3). In addition, in approximately 35% of cases, metastatic RCC (mRCC) was first diagnosed (4).

Since 2006, treatment of mRCC in the first instance has gradually changed from interleukin-2 (IL-2) and interferon-α (IFN-α) with serious toxic and side effects to the treatment of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) Sunitinib (Suni) and Pazopanib (Pazo) (5). Over the ensuing years, with the advent of TKI and mamman target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, survival rates for those with mRCC have improved dramatically (6). Simultaneously in 2016, the immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) has achieved significant effect in the treatment of mRCC, which could be regarded as a milestone (7). Recently, ICI-TKI and ICI-ICI have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in patients with mRCC. Phase 3 CLEAR Trial demonstrated that the objective response rate (ORR), OS and progression-free survival (PFS) of first-line treatment Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab (LenPem) were significantly higher than that of Suni (8). First-line treatment Nivolumab plus Cabozantinib (NivoCabo), when compared with Suni, showed significantly improved OS, PFS, and ORR in phase 3 CheckMate 9ER (9). A four-year-long study indicated that in intermediate/poor-risk patients with IMDC, Nivolumab plus lpilimumab (Nivolpi) had better OS, PFS, and ORR than Suni, according to the phase 3 CheckMate 214 trial (10). According to the phase 3 KEYNOTE-426 trial, significant improvement in PFS, OS and ORR for all IMDC risk group patient treated with Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib (PemAxi) versus Suni (11). The phase 3 JAVELIN Renal 101 trial shows that PFS was significantly higher in Avelumab plus Axitinib (AveAxi) than in Suni among all patients in the IMDC risk group (12).

Notwithstanding, there is still no direct comparison between ICI-ICI and ICI-TKI for certain reasons, a head-to-head comparison of different ICI and TKI combinations remains paucity. Naturally, network meta-analysis (NMA) acts as an indispensable bridge to materialize the indirect comparisons. However, previous NMAs did not compare PFS and OS of different interventions at the same time node, resulting potential bias as treatment period might be the confounding factor. Moreover, no studies have focused on the effect of different median follow-up times on ORR and AEs (grade ≥ 3) of different interventions.

Hence, based on this study, we performed a Bayesian NMA to investigate the effectiveness of different combinations of ICI and TKI at each time node and Bayesian network meta-regression analysis adjusting follow-up time using hazard ratios from kaplan meier curve as primitive data to provide more precise evidence for practice in clinical settings.

2. Methods

This NMA was guided by the PRISMA guideline (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis) (13).

2.1. Search strategy

We searched Google Scholars, Cochrane Library (CENTRAL), PubMed, Scopus and Embase from inception to August 28, 2022, with the following Mesh terms: (“kidney carcinoma” OR “Carcinoma, Renal Cell” OR “renal cell cancer” OR “renal cell carcinoma” OR “kidney cancer” OR “renal carcinoma” OR “renal cancer”) AND (“randomized” OR “Allocation, Random” OR “Randomization”).

2.2. Selection criteria

The following criteria were used to determine inclusion: (1) The mRCC patient population; (2) no history of systemic therapy; (3) first-line pairwise comparisons treatments; (4) reporting PFS, OS, ORR, or AEs (grade ≥ 3). (5) randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Below are the exclusion criteria: (1) observational studies, letters, review, or conference abstract; (2) single-arm design studies; (3) animal studies or research in vitro; (4) interferon as control arm (in light of the widespread acceptance of TKI as a standard of care); (5) non-Chinese and non-English literature.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

In the included studies, data were independently extracted by two investigators (SQ and ZX) and used the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool, assessed the risk of bias for each included RCT by Review Manager 5.3, any discrepancy was arbitrated by the senior reviewer (XC). Variables recorded include: name of the first author, country, publication year, number of patients, condition, therapeutic drugs, treatment dosage, median follow-up time, treatment level, ORR, AEs (grade ≥ 3), and the hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) associated with PFS and OS. Subsequently, the data regarding to PFS and OS at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36 month were harvested from kaplan meier curve by Getdata 2.26.

2.4. Data analysis

For PFS and OS at each time point, the Bayesian NMA was conducted with STATA 17.0 MP to directly and indirectly compare multiple treatments. After evaluating OS and PFS at each time point with odds ratio (OR) and 95% Cl, treatment ranking was performed conducting the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) values, however, whether the effect size between any pair reached the significance was determined by net-league table, which was also called matrix in algebra. Inconsistency and consistency tests were performed to examine the existence of inconsistency. Publication bias was assessed by funnel plots as well.

HRs for OS and PFS, Napierian Logarithm HR (lnHR) and standard error of lnHR (selnHR) for each study were calculated by STATA 17.0 MP. For the ORR and AEs (grade ≥ 3), conventional meta-analyses were conducted by STATA 17.0 MP to generate Napierian Logarithm odds ratios (lnOR) and standard error of lnOR (selnOR) for each study. Subsequently these data (lnHR and selnHR for OS and PFS, lnOR and selnOR for ORR and AEs, respectively) were input into Rstudio 4.1.2 by “gemtc” package to conduct Bayesian NMA. if I2 <50% and p>0.01, fixed effect model would be implemented; if 50%<I2 <75%, random effect model was carried out; if I2 >75%, Galbraith plot would be drawn to preclude the studies outside the outlines. Markov-chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) was used to obtain posterior distributions, with 20,000 burn-ins and 150,000 iterations of 4 each chain and a thinning interval of 10 for each outcome. Brooks-Gelman-Rubin diagnostics and Trace plots were used to evaluate and visualize the convergence of the model over iterations. Matrices were also generated by Rstudio 4.1.2.

Finally, we conducted sensitivity analyses, using median follow-up time as a covariate to perform meta-regression analyses to eliminate potential confounding factors.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the included studies

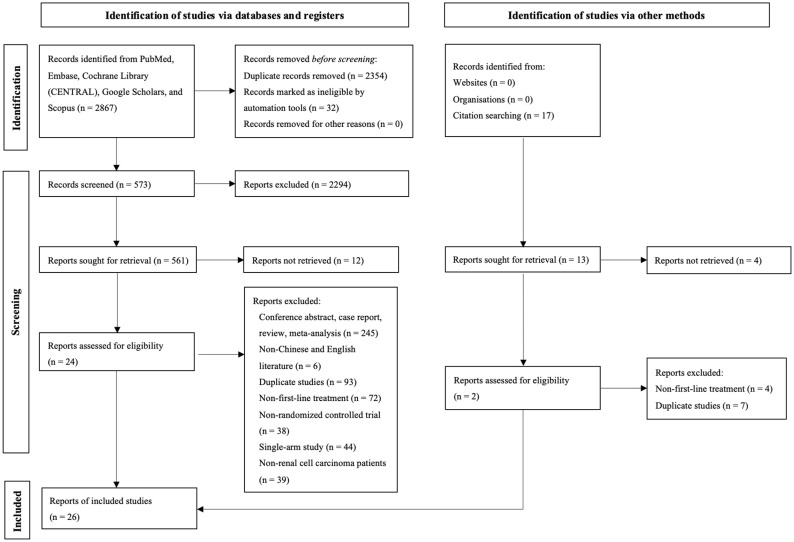

During the initial search, we obtained 5253 publications. As a result of eliminating duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 537 studies were eligible to be reviewed in full, and 26 studies finally met our criteria ( Figure 1 ) (8–12, 14–34) Eventually a total of 22 RCTs reporting 11,090 patients with 19 interventions, namely Suni, Bevacizumab (Bev), Cabozantinib (Cabo), Pazo, Savolitinib (Savo), Sorafenib (Sora), Axitinib (Axi), Anlotinib (Anlo), Nivolumab (Nivo), Atezolizumab (Atezo), PemAxi, Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab (AtezoBev), AveAxi, LenPem, NivoCabo, NivoIpi, Lenvatinib plus Everolimus (LenEvero), Pazopanib plus Everolimus (PazoEvero), and IMA901 plus Sunitinib (IMA901Suni). A detailed description of the included studies can be found in Table 1 . All patients included in the study were untreated patients with mRCC, and a median follow-up period of 6.4 months to 55 months was reported in the study. The assessment of risk of bias is presented in Supplementary Figures 1A and B .

Figure 1.

This diagram shows the PSRISMA flow diagram for study search and selection (updated in 2020). PSRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; CENTRAL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; Embase, Excerpta Medica database.

Table 1.

Characteristics of first-line systemic therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma studies included in the network meta-analysis.

| Study | Year | Condition | Treatment | Sample size | Follow-up (month) |

Dosage | Outcomes | Treatment level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rini (14) | 2016 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Sunitinib | 204 | 33.3 | 50 mg Qd | PFS, OS, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| IMA901+Sunitinib | 135 | Sunitinib 50 mg Qd and IMA901 4.13 mg intr | ||||||

| Yang (15) | 2003 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Bevacizumab | 39 | 27 | 3 mg/kg Q2W | PFS, OS, ORR | first-line therapy |

| Placebo | 40 | matching Placebo | ||||||

| Choueiri (16) | 2018 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Cabozantinib | 79 | 21.4 | 60 mg Qd | PFS, OS, ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Sunitinib | 79 | 50 mg Qd | ||||||

| Tamada (17) | 2022 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Pembrolizumab+Axitinib | 44 | 29.5 | Pembrolizumab 200 mg Q3W + Axitinib 5 mg Bid | PFS, ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Sunitinib | 50 | 50 mg Qd | ||||||

| Sternberg (18) | 2010 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Pazopanib | 290 | 6.4 | 800 mg Qd | PFS, ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Placebo | 145 | matching Placebo | ||||||

| Sheng (19) | 2020 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Sunitinib | 100 | 29.5 | 50 mg Qd | PFS, OS, ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Pazopanib | 109 | 800 mg Qd | ||||||

| Motzer (20) | 2013 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Pazopanib | 557 | 29.5 | 801 mg Qd | PFS, ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Sunitinib | 553 | 50 mg Qd | ||||||

| Motzer (21) | 2014 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Pazopanib | 557 | 29.5 | 800 mg QD | OS | first-line therapy |

| Sunitinib | 553 | 50 mg Qd | ||||||

| Cirkel (22) | 2016 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Pazopanib+Everolimus | 52 | 20.2 | Pazopanib 800mg Qd + Everolimus 10 mg Qd | PFS, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Pazopanib | 49 | 800mg Qd | ||||||

| Powles (11) | 2020 | advanced renal cell carcinoma | Pembrolizumab+Axitinib | 432 | 30.6 | 200 mg intr Q3W | PFS, OS, ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Sunitinib | 429 | 5 mg Axitinib Qd or 50 mg Sunitinib Qd | ||||||

| Choueiri (23) | 2020 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Savolitinib | 33 | 20.6 | 600mg Qd | PFS, OS, ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Sunitinib | 27 | 50 mg Qd | ||||||

| Escudier (24) | 2007 | advanced renal cell carcinoma | Sorafenib | 451 | 6.6 | 400 mg Bid | PFS, OS, ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Placebo | 452 | matching Placebo | ||||||

| Cai (25) | 2018 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Sorafenib | 110 | 23 | 400 mg Bid | OS | first-line therapy |

| Sunitinib | 74 | 50 mg Qd | ||||||

| Rini (26) | 2019 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Atezolizumab+Bevacizumab | 454 | 24 | Atezolizumab 1200 mg + Bevacizumab 15 mg/kg intr Q3W | PFS, OS, ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Sunitinib | 461 | 50 mg Qd | ||||||

| McDermott (27) | 2018 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Atezolizumab+Bevacizumab | 101 | 20.7 | Atezolizumab 1,200 mg intr + Bevacizumab 15 mg/kg Q3W | PFS, ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Sunitinib | 101 | 50 mg Qd | ||||||

| Atezolizumab | 103 | 1,200 mg intr Q3W | ||||||

| Choueiri (12) | 2020 | advanced renal cell carcinoma | Avelumab+Axitinib | 442 | 18.5 | Avelumab 10 mg/kg intr Q2W + Axitinib 5 mg Bid | PFS, OS, ORR | first-line therapy |

| Sunitinib | 444 | 50 mg Qd | ||||||

| Numakura (28) | 2021 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Axitinib | 134 | 20 | 5 mg Bid | PFS, OS, ORR | first-line therapy |

| Sunitinib | 274 | 50 mg Qd | ||||||

| Hutson (29) | 2013 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Axitinib | 192 | 37 | 5 mg Bid | PFS, ORR | first-line therapy |

| Sorafenib | 96 | 400 mg Bid | ||||||

| Hutson (30) | 2016 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Axitinib | 192 | 37 | 5 mg Bid | OS, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Sorafenib | 96 | 400 mg Bid | ||||||

| Rini (31) | 2011 | advanced renal cell carcinoma | Axitinib | 361 | 30 | 5 mg Bid | PFS, ORR | first-line therapy |

| Sorafenib | 362 | 400 mg Bid | ||||||

| Rini (32) | 2013 | advanced renal cell carcinoma | Axitinib | 361 | 30 | 5 mg Bid | OS, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Sorafenib | 362 | 400 mg Bid | ||||||

| Zhou (33) | 2019 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Anlotinib | 90 | 30.5 | 12 mg Qd | PFS, OS, ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Sunitinib | 43 | 50 mg Qd | ||||||

| Motzer (8) | 2021 | advanced renal cell carcinoma | Lenvatinib+Pembrolizumab | 355 | 26.6 | Lenvatinib 20 mg Qd + Pembrolizumab 200 mg intr Q3W | PFS, OS, ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Sunitinib | 357 | 50 mg Qd | ||||||

| Lenvatinib+Everolimus | 357 | Lenvatinib 18 mg Qd + Everolimus 5 mg Qd | ||||||

| Motzer (9) | 2022 | advanced renal cell carcinoma | Nivolumab+Cabozantinib | 323 | 32.9 | Nivolumab 240 mg intr Q2W + Cabozantinib 40 mg Qd | PFS, OS, ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Sunitinib | 328 | 50 mg Qd | ||||||

| Albiges (10) | 2020 | advanced renal cell carcinoma | Nivolumab+lpilimumab | 550 | 55 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg Q3W + Ipilimumab 1 mg/kg Q3W | PFS, OS, ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Sunitinib | 546 | 50 mg Qd | ||||||

| Vano (34) | 2022 | metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Nivolumab+lpilimumab | 41 | 18 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg Q3W + Ipilimumab 1 mg/kg Q3W | PFS, ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs | first-line therapy |

| Nivolumab | 42 | Nivolumab 240 mg Q2W |

Qd, quaque die; Bid, bis in die; Q3W, every three weeks; Q2W, every two weeks; PFS, progression free survival; OS, overall survival; ORR, objective response rate; AE, adverse event.

3.2. PFS at each time point

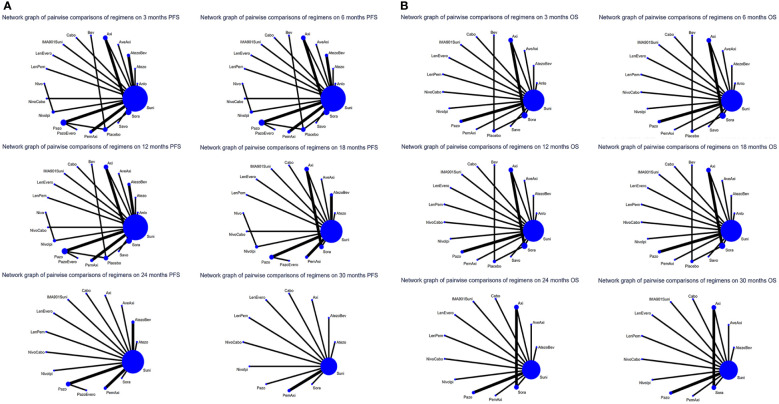

For PFS, 22 out of 26 articles reported related outcomes. At the 6-time points of 3, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 30 month, there were sufficient data for the NMA of PFS. Figure 2A shows the network graphs of pairwise comparison of regimens on each time point of the PFS. The most used agent was Suni, the most comparisons were between Pazo and Suni and between Axi and Sora. Detailed results of direct and indirect comparisons of 19 interventions at each time point are shown in the Supplementary Table 2A-F and Supplementary Figure 3 . Due to the wide use of Suni in the clinic and as the first-line standard treatment, we regard Suni as the primary reference and the top SUCRA-ranked intervention as the secondary reference.

Figure 2.

(A) Network graphs of pairwise comparison of regimens on each time point of the progression free survival and (B) Network graphs of pairwise comparison of regimens on each time point of the overall survival. PFS, progression free survival; OS, overall survival; Suni, Sunitinib; Bev, Bevacizumab; Cabo, Cabozantinib; Pazo, Pazopanib; Savo, Savolitinib; Sora, Sorafenib; Axi, Axitinib; Anlo, Anlotinib; Nivo, Nivolumab; Atezo, Atezolizumab; PemAxi, Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib; AtezoBev, Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab; AveAxi, Avelumab plus Axitinib; LenPem, Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab; NivoCabo, Nivolumab plus Cabozantinib; NivoIpi, Nivolumab plus lpilimumab; LenEvero, Lenvatinib plus Everolimus; PazoEvero, Pazopanib plus Everolimus; IMA901Suni, IMA901 plus Sunitinib.

At 3rd month, compared with Suni, LenPem (OR=2.80,95% Cl: 1.69 to 4.65), Axi (OR=2.55, 95%CI: 1.30 to 5.00), NivoCabo (OR=2.46, 95% Cl: 1.54 to 3.93), LenEvero (OR=1.97, 95%CI: 1.24 to 3.12), PemAxi (OR=1.72, 95%CI: 1.20 to 2.45) and AveAxi (OR=1.64, 95%CI: 1.20 to 2.24) significantly increased PFS rates. Compared with the top SUCRA-ranked intervention LenPem, Axi ranked second.

In comparison with Suni at 6th month, LenPem (OR=4.47,95% Cl: 3.10 to 6.44), Axi (OR=2.32, 95%CI: 1.37 to 3.93), NivoCabo (OR=2.52, 95% Cl: 1.78 to 3.58), LenEvero (OR=1.71, 95%CI: 1.26 to 2.33), PemAxi (OR=1.52, 95%CI: 1.14 to 2.02) and AveAxi (OR=1.62, 95%CI: 1.23 to 2.13) significantly improved PFS. As compared with the top SUCRA-ranked intervention LenPem, NivoCabo ranked second.

At 12th month, the PFS for LenPem (OR=3.88,95% Cl: 2.84 to 5.30), Axi (OR=3.18, 95%CI: 1.86 to 5.42), NivoCabo (OR=2.44, 95% Cl: 1.78 to 3.35), LenEvero (OR=1.95, 95%CI: 1.45 to 2.63), PemAxi (OR=1.72, 95%CI: 1.33 to 2.23) and AveAxi (OR=1.71, 95%CI: 1.31 to 2.24) and AtezoBev (OR=1.38, 95%CI: 1.09 to 1.74) were significantly higher compared to that of Suni. Among them, the highest SUCRA ranking is LenPem followed by Axi.

At 18th month, the PFS was significantly higher for LenPem (OR=2.95, 95%Cl: 1.94 to 4.49), Axi (OR=3.00, 95%CI: 1.62 to 5.56), NivoCabo (OR=2.49, 95% Cl: 1.61 to 3.85), LenEvero (OR=1.62, 95%CI: 1.07 to 2.46), PemAxi (OR=1.76, 95%CI: 1.22 to 2.55), AveAxi (OR=1.91, 95%CI: 1.28 to 2.84), AtezoBev (OR=1.52, 95%CI: 1.05 to 2.22) and Sora (OR=2.38, 95%CI: 1.13 to 5.02) compared to Suni. Axi is the highest SUCRA ranking, LenPem was remarkably inferior to Axi.

At 24th month, the PFS increased significantly when LenPem (OR=3.46, 95%Cl: 2.50 to 4.79), Axi (OR=2.81, 95%CI: 1.57 to 5.04), NivoCabo (OR=2.48, 95% Cl: 1.75 to 3.51), LenEvero (OR=1.61, 95%CI: 1.15 to 2.25), PemAxi (OR=1.70, 95%CI: 1.29 to 2.24) and AveAxi (OR=1.91, 95%CI: 1.44 to 2.52) were compared with Suni. LenPem has the highest SUCRA ranking, while Axi is remarkably inferior to LenPem.

At 30th month, the PFS was significantly higher for LenPem (OR=3.26, 95%Cl: 2.26 to 4.71), Axi (OR=2.28, 95%CI: 1.22 to 4.26), NivoCabo (OR=3.10, 95%Cl: 2.08 to 4.62), LenEvero (OR=2.14, 95%CI: 1.47 to 3.13), PemAxi (OR=1.80, 95%CI: 1.34 to 2.42) and Nivolpi (OR=1.51, 95%CI: 1.17 to 1.96) compared to Suni. LenPem is ranked highest SUCRA among them, followed by NivoCabo.

At 36th month, the PFS was significantly higher for LenPem (OR=3.26, 95%Cl: 2.26 to 4.71), Axi (OR=2.20, 95%CI: 1.09 to 4.44), NivoCabo (OR=3.55, 95%Cl: 2.22 to 5.67), LenEvero (OR=2.14, 95%CI: 1.47 to 3.13) and Nivolpi (OR=1.58, 95%CI: 1.21 to 2.06) compared to Suni. According to their SUCRA rankings, NivoCabo is the highest followed by LenPem.

In PFS, compared with Suni, the intervention measures with significant effect from 3 to 36 months were LenPem, Axi, NivoCabo and LenEvero in order from high to low. We summarize the details of the interventions with significant results compared with Suni in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Progression free survival for each time point for interventions that were significant compared to Sunitinib (shown as odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals).

| Time point | Control group | LenPem | Axi | NivoCabo | LenEvero | PemAxi | AveAxi | AtezoBev | Nivolpi | Sora |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 month | Suni | 2.80 (1.69,4.65) | 2.55 (1.30,5.00) | 2.46 (1.54,3.93) | 1.97 (1.24,3.12) | 1.72 (1.20,2.45) | 1.64 (1.20,2.24) | × | × | × |

| Placebo | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | |

| 6 month | Suni | 4.47 (3.10,6.44) | 2.32 (1.37,3.93) | 2.52 (1.78,3.58) | 1.71 (1.26,2.33) | 1.52 (1.14,2.02) | 1.62 (1.23,2.13) | × | × | × |

| Placebo | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | |

| 12 month | Suni | 3.88 (2.84,5.30) | 3.18 (1.86,5.42) | 2.44 (1.78,3.35) | 1.95 (1.45,2.63) | 1.72 (1.33,2.23) | 1.71 (1.31,2.24) | 1.38 (1.09,1.74) | × | × |

| Placebo | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | |

| 18 month | Suni | 2.95 (1.94,4.49) | 3.00 (1.62,5.56) | 2.49 (1.61,3.85) | 1.62 (1.07,2.46) | 1.76 (1.22,2.55) | 1.91 (1.28,2.84) | 1.52 (1.05,2.22) | × | 2.38 (1.13,5.02) |

| Placebo | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 24 month | Suni | 3.46 (2.50,4.79) | 2.81 (1.57,5.04) | 2.48 (1.75,3.51) | 1.61 (1.15,2.25) | 1.70 (1.29,2.24) | 1.91 (1.44,2.52) | × | × | × |

| Placebo | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 30 month | Suni | 3.26 (2.26,4.71) | 2.28 (1.22,4.26) | 3.10 (2.08,4.62) | 2.14 (1.47,3.13) | 1.80 (1.34,2.42) | - | × | 1.51 (1.17,1.96) | × |

| Placebo | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 36 month | Suni | 3.26 (2.26,4.71) | 2.20 (1.09,4.44) | 3.55 (2.22,5.67) | 2.14 (1.47,3.13) | - | - | - | 1.58 (1.21,2.06) | × |

| Placebo | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Suni, Sunitinib; Sora, Sorafenib; Axi, Axitinib; PemAxi, Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib; AtezoBev, Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab, AveAxi, Avelumab plus Axitinib; LenPem, Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab; NivoCabo, Nivolumab plus Cabozantinib; NivoIpi, Nivolumab plus lpilimumab; LenEvero, Lenvatinib plus Everolimus.

√: the treatment on the top is significant compared to the control group on the left; ×: the treatment on the top is not significant compared to the Control group on the left.

3.3. OS at each time point

18 out of 26 articles reported outcomes related to OS. In this study, adequate data were available at 3, 6, 12, 24 and 30 month to conduct NMA. An analysis of pairwise comparison of regimens on every OS time point is shown in Figure 2B . As for agents, Suni was most commonly used, with Axi and Sora being most commonly compared. A detailed comparison of 17 interventions at each time point is presented in Supplementary Tables 3A-F and Supplementary Figure 4 .

At 3rd month, two interventions were significantly compared with Suni, but were not significantly compared with placebo. Therefore, at 3rd month, there were no interventions with significant results.

At 6th month, in comparison with Suni, PemAxi (OR=2.47, 95%CI: 1.45 to 4.19), NivoCabo (OR=2.07, 95%Cl: 1.22 to 3.52), Axi (OR=2.13, 95%CI: 1.07 to 4.23) and LenPem (OR=3.05, 95%Cl: 1.46 to 6.36) were more effective, in which LenPem scored highest and PemAxi was second.

At 12th month, PemAxi (OR=2.37, 95%CI: 1.61 to 3.50), NivoCabo (OR=1.85, 95%Cl: 1.24 to 2.75), Nivolpi (OR=1.48, 95%CI: 1.10 to 2.00) and LenPem (OR=2.64, 95%Cl: 1.68 to 4.14) significantly increased OS rate compared to Suni. According to their SUCRA rankings, LenPem ranked first, and PemAxi ranked second.

At 18th month, there was a significant increase in OS rate with PemAxi (OR=1.67, 95%CI: 1.22 to 2.30), NivoCabo (OR=1.69, 95%Cl: 1.18 to 2.40), Nivolpi (OR=1.57, 95%CI: 1.20 to 2.05), LenPem (OR=2.33, 95%Cl: 1.58 to 3.44) and AveAxi (OR=1.41, 95%CI: 1.03 to 1.92) compared with Suni. Rankings based on SUCRA, LenPem was ranked first, followed by NivoCabo.

At 24th month, OS rate was significantly increased by PemAxi (OR=1.52, 95%CI: 1.14 to 2.04), NivoCabo (OR=1.57, 95%Cl: 1.13 to 2.17), Nivolpi (OR=1.58, 95%CI: 1.23 to 2.03) and LenPem (OR=1.66, 95%Cl: 1.18 to 2.34) in comparison with Suni. In accordance with their SUCRA rankings, LenPem showed the best results, while Nivolpi was ranked second.

At 30th month, OS rates were significantly higher with PemAxi (OR=1.41, 95%CI: 1.07 to 1.86), NivoCabo (OR=1.64, 95%Cl: 1.19 to 2.25), Nivolpi (OR=1.43, 95%CI: 1.12 to 1.82) and AveAxi (OR=1.71, 95%Cl: 1.31 to 2.24) than with Suni. As ranked by SUCRA, AveAxi performed best, followed by NivoCabo.

Among the treatments tested at 36th month, the OS rate of PemAxi (OR=1.84, 95%CI: 1.40 to 2.42), NivoCabo (OR=1.41, 95%Cl: 1.03 to 1.92) and Nivolpi (OR=1.38, 95%CI: 1.09 to 1.76) was significantly higher than that of Suni. Rankings according to SUCRA, PemAxi had the best outcome, followed by NivoCabo.

In OS, compared with Suni, PemAxi and NivoCabo were significant from 6 to 36 months; Nivolpi significant from 12 to 36 months; LenPem significant from 6 to 24 months. We summarize the details of the interventions with significant results compared with Suni in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Overall survival for each time point for interventions that were significant compared to Sunitinib (shown as odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals).

| Time point | Control group | IMA901Suni | PemAxi | NivoCabo | Nivolpi | Axi | LenPem | AveAxi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 month | Suni | 3.57 (1.08,11.84) | 2.73 (1.19,6.23) | × | × | × | × | × |

| Placebo | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

| 6 month | Suni | × | 2.47 (1.45,4.19) | 2.07 (1.22,3.52) | × | 2.13 (1.07,4.23) | 3.05 (1.46,6.36) | × |

| Placebo | × | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 12 month | Suni | × | 2.37 (1.61,3.50) | 1.85 (1.24,2.75) | 1.48 (1.10,2.00) | × | 2.64 (1.68,4.14) | × |

| Placebo | × | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 18 month | Suni | × | 1.67 (1.22,2.30) | 1.69 (1.18,2.40) | 1.57 (1.20,2.05) | × | 2.33 (1.58,3.44) | 1.41 (1.03,1.92) |

| Placebo | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 24 month | Suni | × | 1.52 (1.14,2.04) | 1.57 (1.13,2.17) | 1.58 (1.23,2.03) | × | 1.66 (1.18,2.34) | × |

| Placebo | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 30 month | Suni | × | 1.41 (1.07,1.86) | 1.64 (1.19,2.25) | 1.43 (1.12,1.82) | × | × | 1.71 (1.31,2.24) |

| Placebo | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 36 month | Suni | × | 1.84 (1.40,2.42) | 1.41(1.03,1.92) | 1.38(1.09,1.76) | × | × | × |

| Placebo | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Suni, Sunitinib; IMA901Suni, IMA901 plus Sunitinib; Axi, Axitinib; PemAxi, Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib; AveAxi, Avelumab plus Axitinib; LenPem, Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab; NivoCabo, Nivolumab plus Cabozantinib; NivoIpi, Nivolumab plus lpilimumab.

√, the treatment on the top is significant compared to the control group on the left; ×, the treatment on the top is not significant compared to the Control group on the left.

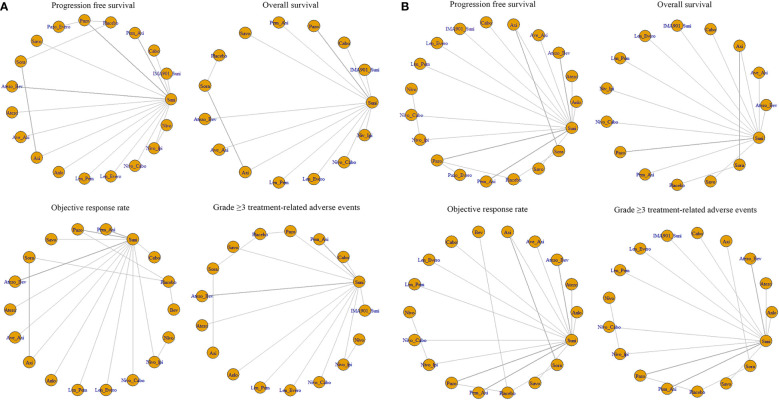

3.4. Survival Analysis of PFS, OS, ORR and AEs (grade ≥ 3)

Twenty-two of the 26 articles reported outcomes related to the HRs of PFS. We compared the 19 interventions included directly and indirectly. The network graph is shown in Figure 3A . The intervention measures with significant difference compared with Suni are LenPem (HR=2.56, 95%Crl: 1.55 to 4.24), Cabo (HR=2.08, 95%Crl: 1.12 to 3.87), AveAxi (HR=1.82, 95%Crl: 1.10 to 3.02), NivoCabo (HR=1.79, 95%Crl: 1.09 to 2.94) and PemAxi (HR=1.46, 95%Crl: 1.01 to 2.19). Compared with the top SUCRA-ranked intervention LenPem, Cabo ranked second. Detailed results are shown in Supplementary Table 4A .

Figure 3.

(A) Network meta-analysis plots for outcomes of interest in intent-to-treat population and (B) Network meta-regression analysis plots for outcomes of interest in intent-to-treat population. Suni, Sunitinib; Bev, Bevacizumab; Cabo, Cabozantinib; Pazo, Pazopanib; Savo, Savolitinib; Sora, Sorafenib; Axi, Axitinib; Anlo, Anlotinib; Nivo, Nivolumab; Atezo, Atezolizumab; Pem_Axi, Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib; Atezo_Bev, Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab; Ave_Axi, Avelumab plus Axitinib; Len_Pem, Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab; Nivo_Cabo, Nivolumab plus Cabozantinib; Nivo_Ipi, Nivolumab plus lpilimumab; Len_Evero, Lenvatinib plus Everolimus; Pazo_Evero, Pazopanib plus Everolimus; IMA901_Suni, IMA901 plus Sunitinib.

The results related to OS were reported in 18 of 26 articles. A direct and indirect comparison was made between the included 15 interventions. The network graph is shown in Figure 3A . The interventions with significant differences from Suni are LenPem (HR=2.27, 95%Crl 1.28 to 4.03), PemAxi (HR=2.08, 95%Crl 1.07 to 4.03), and AveAxi (HR=1.93, 95%Crl 1.04 to 3.56). Among them, the highest SUCRA ranking is LenPem, followed by PemAxi. Detailed results are shown in Supplementary Table 4B .

Results related to ORR were reported in 20 out of 26 articles. The 18 interventions were compared directly and indirectly. The network graph is shown in Figure 3A . The interventions that showed significant difference compared with Suni are LenPem (HR=4.36, 95%Crl 2.28 to 8.18), Cabo (HR=4.01, 95%Crl 1.44 to 11.40), NivoCabo (HR=3.19, 95%Crl 1.68 to 6.16), AveAxi (HR=2.98, 95%Crl 1.57 to 5.54), PemAxi (HR=2.28, 95%Crl 1.35 to 3.80) and LenEvero (HR=2.04, 95%Crl 1.07 to 3.82). In order of SUCRA ranking, LenPem has the highest ranking, followed by Cabo. Detailed results are shown in Supplementary Table 4C .

Regarding AEs (grade ≥ 3), indirect and direct comparisons were conducted between 16 interventions. The network graph is shown in Figure 3A . Nivolumab, Sora, Atezolizumab, Anlotinib, Savo, Nivolpi and Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab are less toxic than Suni. Cabo, PemAxi, NivoCabo, Axi, Pazo had no significant difference compared with Suni. IMA901 plus Suni, LenPem and LenEevero are more toxic than Suni. Detailed results are shown in Supplementary Table 4D .

For all outcomes, it was revealed in Brooks-GelmanRubin diagnostic that the inferential iterations for each MCMC were stable and reproducible. We used history feature to confirm the convergence of the model in all outcomes as well. Detailed results are presented in Supplementary Figures 5A-D and Supplementary Figures 6A-D .

3.5. Heterogeneity and network meta-regression analysis

In order to better explain the heterogeneity, we performed sensitivity analysis on the four outcomes. Meta-regression analysis was performed on PFS, OS, ORR and AEs (grade ≥ 3) with the median follow-up time as the covariate. The network graphs are shown in Figure 3B . Detailed results are shown in Supplementary Table 5A-D .

For PFS, after meta-regression analysis, PemAxi, NivoCabo are not significantly compared with Suni, LenPem, Cabo and AveAxi are consistently better than Suni. For OS, PemAxi and LenPem are still better than standard Suni. For ORR, in comparison to Suni, Cabo, LenPem, PemAxi, NivoCabo and LenEvero consistently provide better results. For AEs (grade ≥ 3), after meta-regression analysis, the serious adverse events of LenPem and LenEvero were not different from that of Suni. The detailed results before and after meta-regression are shown in the Table 4 .

Table 4.

Outcomes of interest in intent-to-treat population compared to Sunitinib before and after meta-regression (shown as hazard ratio and 95% credible intervals).

| Outcomes | Methods | Cabo | PemAxi | AveAxi | LenPem | NivoCabo | LenEvero |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFS | meta-analysis | 2.08(1.12,3.87) | 1.46(1.01,2.19) | 1.82(1.10,3.02) | 2.56(1.55,4.24) | 1.79(1.09,2.94) | × |

| meta-regression analysis | 2.30(1.10,4.60) | × | 2.10(1.02,4.40) | 2.50(1.50,4.30) | × | × | |

| OS | meta-analysis | × | 2.08(1.07,4.03) | 1.93(1.04,3.56) | 2.27(1.28,4.03) | × | × |

| meta-regression analysis | × | 2.00(1.81,4.30) | × | 1.90(1.30,4.50) | × | × | |

| ORR | meta-analysis | 4.01(1.44,11.40) | 2.28(1.35,3.80) | 2.98(1.57,5.54) | 4.36(2.28,8.18) | 3.19(1.68,6.16) | 2.04(1.07,3.82) |

| meta-regression analysis | 3.80(1.10,12.00) | 2.20(1.04,4.90) | × | 4.30(2.10,8.90) | 3.10(1.02,9.90) | 2.00(1.08,4.10) | |

| AE | meta-analysis | × | × | - | 2.07 (1.46,2.93) | × | 2.20 (1.55,3.14) |

| meta-regression analysis | × | × | - | × | × | × |

PemAxi, Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib; AveAxi, Avelumab plus Axitinib; LenPem, Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab; NivoCabo, Nivolumab plus Cabozantinib; LenEvero, Lenvatinib plus Everolimus; Cabo, Cabozantinib.

×: the treatment on the top is not significant compared to Sunitinib.

For meta-regression, as shown by Brooks-GelmanRubin diagnostic, inferential iterations were reproducible and stable for each MCMC. Additionally, we used the history feature to confirm the model’s convergence in all outcomes. Detailed results are presented in Supplementary Figures 7A-D and Figures 8A-D .

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal findings

This is the first Bayesian NMA investigating the pairwise effect of regimens on OS and PFS at each time node; meanwhile, the prominent innovativeness is the implementation of network meta-regression analysis adjusting confounding factor, which is the Qomolangma in NMA. There are the following findings.

Regarding PFS, compared to Suni, the interventions with significant effects were LenPem, Axi, NivoCabo and LenEvero from high to low from 3 to 36 months. PemAxi and AveAxi also showed good results compared to Suni, but due to the lack of data, it was not possible to tell whether the significance persisted until month 36. Based on Bayesian NMA of HRs of PFS and Bayesian network meta-regression analysis with median follow-up time as a covariate, the comparisons with Suni were significant in descending order of LenPem, Cabo and AveAxi. In summary, LenPem is the first choice for improving PFS.

Regarding OS, from 6 to 36 months, PemAxi and NivoCabo were significantly superior to Suni. Bayesian NMA of HRs of OS and Bayesian network regression analysis with median follow-up time as covariate showed that LenPem and PemAxi were significantly different from Suni. Considering LenPem significant only from 6 to 24 months, PemAxi is the first choice for improving OS.

Regarding ORR, in comparison to standard chemotherapy, Cabo, LenPem, PemAxi, NivoCabo and LenEvero consistently provide better results. Notably, LenEvero needs to be excluded because according to the Meta-regression analysis, LenEvero is inferior to D in both primary endpoints PFS and OS although the ORR results are significant.

Regarding AEs (grade ≥ 3), after Bayesian network meta-regression analysis with median follow-up time as a covariate, Atezo and Savo were significantly less toxic than Suni, and the rest were not significant with Suni. However, both Atezo and Savo were inferior to Suni in primary endpoints PFS and OS, so they were not considered as first-line therapeutic agents for mRCC.

These results demonstrate that the combination of ICI-TKI has significant OS, PFS and ORR benefits in patients with mRCC. Interestingly, clinical studies show the separating survival benefit of ICI-TKI much earlier than ICI-ICI in first-line treatment of mRCC (9, 35). As well, some investigations showed that the OS of ICI-TKI combination treatment effect is more favorable than dual combination immunotherapy (10, 11). Moreover, the comparison of efficacy results and tumors with sarcomatoid differentiation in clinical trials concluded that the ORR and PFS of PemAxi were superior to those of Nivolpi (36, 37). Therefore, ICI-TKI combination therapy is also the preferred therapy for aggressive, rapidly progressive renal cancer.

RCC is a highly vascularized tumor, and the expression level of VEGF-A is significantly higher in RCC patients than in patients with other types of cancer (38). In addition, TKI can increase immune infiltration directly or indirectly while improving vascularity (39, 40). Studies have shown that both Cabo and Len have modulating and immune-promoting properties (41, 42). Thus, the combination of TKI and ICI has a synergistic anti-tumor effect. Treatment-related toxicity should also be considered when TKI and ICI are used in combination. ICI produces immune-related adverse events, while TKI is chronically toxic. The toxicity of the combination, although greater than that of monotherapy such as Atezo, was not significantly compared to standard treatment. Its toxicity is within the acceptable range, only the superposition of dual adverse effects will increase the difficulty of clinical management.

In our research, although both LenPem and PemAxi showed significant advantages in terms of PFS and ORR, the toxicity of LenPem cannot be ignored, and in this clinical trial, the dose of Lenvatinib was consistently reduced by constant reductions to reduce adverse events that could discontinue treatment. In terms of OS, the remarkable performance of PemAxi lasts up to 36 months, while LenPem lasts only up to 24 months. In addition, the toxicity of PemAxi is lower and the quality of life of patients is higher. In summary, our study shows that for mRCC patients PemAxi can have better survival outcomes, lower toxicity, and higher quality of life. Therefore PemAxi appears to be the superior first-line TKI-ICI combination.

4.2. Previous network meta-analyses

Treatments for mRCC in the first instance has been changing rapidly in recent years, and the earlier NMAs did not incorporate the multiple ICI-TKI interventions recommended by the mRCC first-line treatment guidelines in recent years (43, 44). In 2019, Wang et al (45) published a NMA that focused only on the analysis of ICI and included many interventions that were completely withdrawn from the clinic due to high toxicity, such as IFN-α and IL-2. Manz et al (46) published a NMA in 2020, Focusing solely on TKI. Other studies have focused only on immune-based interventions (47, 48). In two recent studies, they included only a few treatment nodes and used a frequentist NMA rather than a Bayesian framework (49, 50).

4.3. Strengths and limitations

We evaluated 19 first-line interventions using 26 high-quality studies that were screened. First, we used a Bayesian framework that is more flexible relative to the frequentist, describing pairwise comparisons in terms of probabilistically distributed random variables (51). Second, for the analysis of PFS and OS, it lasted until 36 months. In addition, based on PFS, OS, ORR and AEs (grade ≥ 3), we performed a sensitivity analysis. We performed a network meta-regression analysis with median follow-up time as a covariate. Third, due to the inclusion of a sufficient number of studies, we performed a paired meta-analysis. Closed loops existed in the network, so heterogeneity was also evaluated and the results showed good agreement between the trials included in the study. Fourth, the stability and replicability of each MCMC chain iteration was demonstrated using Brooks-GelmanRubin diagnostics, as well as the convergence of the model was estimated.

A number of limitations are associated with this NMA. First, we have compared ICI and TKI combinations directly or indirectly; however, this approach cannot fully replace a head-to-head comparison. Therefore direct comparative clinical trials are still indispensable. Second, the quality of the trials included in this analysis may have been affected by several types of bias, which could have some impact on the validity of the overall outcomes. Third, the study population included patients with clear cell histology, so the final results are not applicable to patients with non-clear cell histology. Fourth, only trials with standard dosing regimens were included in this study, and the doses and schedules administered in actual clinical settings may differ from those of the included studies; consequently, efficacy and tolerability may be affected to some extent. Some investigations have demonstrated that modifications to the dose and schedule pattern of Suni administration may improve its efficacy and enhance tolerability (52, 53). Fifth, there was a large variation in median follow-up time across studies, and although this influence was corrected using meta-regression, the results need to be further investigated in the clinic. In addition, another part of confounding factors (e.g., PD-L1 status, number of focal metastases, patient risk class, etc.) had missing data in some trials, and we could not correct for these factors using meta-regression; therefore, the results of this Bayesian NMA need to be treated with caution.

4.4. Future research

We hope that future clinical studies will be more precise and focus more on the outcomes of ORR and AEs at each time point. According to the studies, the median follow-up period ranged from 6.4 to 55 months, and the wide variation in follow-up time can have an impact on outcome indicators. Although we corrected for this with meta-regression using time as a covariate, the results this result cannot be used as a proxy for accurate clinical studies. The findings would be more convincing if the ORR or AEs of different interventions were compared at the same time points.

5. Conclusion

Considering the lower toxicity and the higher quality of life, PemAxi should be recommended as the optimal therapy in treating mRCC. Certainly, it is necessary to conduct more head-to-head comparisons in order to confirm these findings.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SQ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft. ZX: Investigation, Data Curation. XC: Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing. SW: Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing. HL: Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing. JL: Visualization, Writing - Original Draft. XG: Visualization, Writing - Original Draft. JY: Visualization, Writing - Original Draft. CL: Supervision, Conceptualization. YW: Supervision, Conceptualization. HW: Formal analysis, Supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff of the Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine library for assistance in obtaining the full text of manuscripts not otherwise accessible.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2023.1072634/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin (2022) 72(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Escudier B, Porta C, Schmidinger M, Rioux-Leclercq N, Bex A, Khoo V, et al. Renal cell carcinoma: Esmo clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann Oncol (2019) 30(5):706–20. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saad AM, Gad MM, Al-Husseini MJ, Ruhban IA, Sonbol MB, Ho TH. Trends in renal-cell carcinoma incidence and mortality in the united states in the last 2 decades: A seer-based study. Clin Genitourin Cancer (2019) 17(1):46–57.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rini BI, Campbell SC, Escudier B. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet (2009) 373(9669):1119–32. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60229-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hsieh JJ, Purdue MP, Signoretti S, Swanton C, Albiges L, Schmidinger M, et al. Renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers (2017) 3:17009. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barata PC, Rini BI. Treatment of renal cell carcinoma: Current status and future directions. CA Cancer J Clin (2017) 67(6):507–24. doi: 10.3322/caac.21411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Santoni M, Massari F, Di Nunno V, Conti A, Cimadamore A, Scarpelli M, et al. Immunotherapy in renal cell carcinoma: Latest evidence and clinical implications. Drugs Context (2018) 7:212528. doi: 10.7573/dic.212528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Motzer R, Alekseev B, Rha SY, Porta C, Eto M, Powles T, et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or everolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med (2021) 384(14):1289–300. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Motzer RJ, Powles T, Burotto M, Escudier B, Bourlon MT, Shah AY, et al. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib in first-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma (Checkmate 9er): Long-term follow-up results from an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol (2022) 23(7):888–98. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(22)00290-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Albiges L, Tannir NM, Burotto M, McDermott D, Plimack ER, Barthelemy P, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib for first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma: Extended 4-year follow-up of the phase iii checkmate 214 trial. ESMO Open (2020) 5(6):e001079. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-001079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Powles T, Plimack ER, Soulières D, Waddell T, Stus V, Gafanov R, et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib monotherapy as first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma (Keynote-426): Extended follow-up from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol (2020) 21(12):1563–73. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30436-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Choueiri TK, Motzer RJ, Rini BI, Haanen J, Campbell MT, Venugopal B, et al. Updated efficacy results from the javelin renal 101 trial: First-line avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol (2020) 31(8):1030–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The prisma 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rini BI, Stenzl A, Zdrojowy R, Kogan M, Shkolnik M, Oudard S, et al. Ima901, a multipeptide cancer vaccine, plus sunitinib versus sunitinib alone, as first-line therapy for advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (Imprint): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol (2016) 17(11):1599–611. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30408-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med (2003) 349(5):427–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Choueiri TK, Hessel C, Halabi S, Sanford B, Michaelson MD, Hahn O, et al. Cabozantinib versus sunitinib as initial therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma of intermediate or poor risk (Alliance A031203 cabosun randomised trial): Progression-free survival by independent review and overall survival update. Eur J Cancer (2018) 94:115–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tamada S, Kondoh C, Matsubara N, Mizuno R, Kimura G, Anai S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Outcomes of Japanese patients enrolled in the randomized, phase iii, open-label keynote-426 study. Int J Clin Oncol (2022) 27(1):154–64. doi: 10.1007/s10147-021-02014-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, Szczylik C, Lee E, Wagstaff J, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Results of a randomized phase iii trial. J Clin Oncol (2010) 28(6):1061–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sheng X, Jin J, He Z, Huang Y, Zhou A, Wang J, et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in Chinese patients with locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Pooled subgroup analysis from the randomized, comparz studies. BMC Cancer (2020) 20(1):219. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-6708-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, Reeves J, Hawkins R, Guo J, et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med (2013) 369(8):722–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, McCann L, Deen K, Choueiri TK. Overall survival in renal-cell carcinoma with pazopanib versus sunitinib. N Engl J Med (2014) 370(18):1769–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1400731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cirkel GA, Hamberg P, Sleijfer S, Loosveld OJL, Dercksen MW, Los M, et al. Alternating treatment with pazopanib and everolimus vs continuous pazopanib to delay disease progression in patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell cancer: The ropetar randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol (2017) 3(4):501–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Choueiri TK, Heng DYC, Lee JL, Cancel M, Verheijen RB, Mellemgaard A, et al. Efficacy of savolitinib vs sunitinib in patients with met-driven papillary renal cell carcinoma: The savoir phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol (2020) 6(8):1247–55. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Szczylik C, Oudard S, Siebels M, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med (2007) 356(2):125–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cai W, Kong W, Dong B, Zhang J, Chen Y, Xue W, et al. Comparison of efficacy, safety, and quality of life between sorafenib and sunitinib as first-line therapy for Chinese patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Chin J Cancer (2017) 36(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s40880-017-0230-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rini BI, Powles T, Atkins MB, Escudier B, McDermott DF, Suarez C, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sunitinib in patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma (Immotion151): A multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet (2019) 393(10189):2404–15. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30723-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McDermott DF, Huseni MA, Atkins MB, Motzer RJ, Rini BI, Escudier B, et al. Clinical activity and molecular correlates of response to atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab versus sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Nat Med (2018) 24(6):749–57. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0053-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Numakura K, Muto Y, Naito S, Hatakeyama S, Kato R, Koguchi T, et al. Outcomes of axitinib versus sunitinib as first-line therapy to patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the immune-oncology era. Cancer Med (2021) 10(17):5839–46. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hutson TE, Al-Shukri S, Stus VP, Lipatov ON, Shparyk Y, Bair AH, et al. Axitinib versus sorafenib in first-line metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Overall survival from a randomized phase iii trial. Clin Genitourin Cancer (2017) 15(1):72–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hutson TE, Lesovoy V, Al-Shukri S, Stus VP, Lipatov ON, Bair AH, et al. Axitinib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: A randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol (2013) 14(13):1287–94. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70465-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rini BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P, Kaprin A, Szczylik C, Hutson TE, et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (Axis): A randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet (2011) 378(9807):1931–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61613-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Tomczak P, Hutson TE, Michaelson MD, Negrier S, et al. Axitinib versus sorafenib as second-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma: Overall survival analysis and updated results from a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol (2013) 14(6):552–62. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70093-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhou AP, Bai Y, Song Y, Luo H, Ren XB, Wang X, et al. Anlotinib versus sunitinib as first-line treatment for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A randomized phase ii clinical trial. Oncologist (2019) 24(8):e702–e8. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vano Y-A, Elaidi R, Bennamoun M, Chevreau C, Borchiellini D, Pannier D, et al. Nivolumab, nivolumab–ipilimumab, and vegfr-tyrosine kinase inhibitors as first-line treatment for metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (Bionikk): A biomarker-driven, open-label, non-comparative, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol (2022) 23(5):612–24. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(22)00128-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, Arén Frontera O, Melichar B, Choueiri TK, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med (2018) 378(14):1277–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1712126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Engel Ayer Botrel T, Datz Abadi M, Chabrol Haas L, da Veiga CRP, de Vasconcelos Ferreira D, Jardim DL. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib and nivolumab plus ipilimumab as first-line treatments of advanced intermediate- or poor-risk renal-cell carcinoma: A number needed to treat analysis from the Brazilian private perspective. J Med Econ (2021) 24(1):291–8. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2021.1883034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Escudier B, Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, Porta C, Tomita Y, Maurer MA, et al. Efficacy of nivolumab plus ipilimumab according to number of imdc risk factors in checkmate 214. Eur Urol (2020) 77(4):449–53. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jubb AM, Pham TQ, Hanby AM, Frantz GD, Peale FV, Wu TD, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, hypoxia inducible factor 1alpha, and carbonic anhydrase ix in human tumours. J Clin Pathol (2004) 57(5):504–12. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.012963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Khan KA, Kerbel RS. Improving immunotherapy outcomes with anti-angiogenic treatments and vice versa. Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2018) 15(5):310–24. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fukumura D, Kloepper J, Amoozgar Z, Duda DG, Jain RK. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using antiangiogenics: Opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2018) 15(5):325–40. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kwilas AR, Ardiani A, Donahue RN, Aftab DT, Hodge JW. Dual effects of a targeted small-molecule inhibitor (Cabozantinib) on immune-mediated killing of tumor cells and immune tumor microenvironment permissiveness when combined with a cancer vaccine. J Transl Med (2014) 12:294. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0294-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kato Y, Tabata K, Kimura T, Yachie-Kinoshita A, Ozawa Y, Yamada K, et al. Lenvatinib plus anti-Pd-1 antibody combination treatment activates Cd8+ T cells through reduction of tumor-associated macrophage and activation of the interferon pathway. PloS One (2019) 14(2):e0212513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wallis CJD, Klaassen Z, Bhindi B, Ye XY, Chandrasekar T, Farrell AM, et al. First-line systemic therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur Urol (2018) 74(3):309–21. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chang X, Zhang F, Liu T, Yang R, Ji C, Zhao X, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of first-line treatments in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer: A network meta-analysis based on phase 3 rcts. Oncotarget (2016) 7(13):15801–10. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang J, Li X, Wu X, Wang Z, Zhang C, Cao G, et al. Role of immune checkpoint inhibitor-based therapies for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the first-line setting: A Bayesian network analysis. EBioMedicine (2019) 47:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Manz KM, Fenchel K, Eilers A, Morgan J, Wittling K, Dempke WCM. Efficacy and safety of approved first-line tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatments in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A network meta-analysis. Adv Ther (2020) 37(2):730–44. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01167-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Elaidi R, Phan L, Borchiellini D, Barthelemy P, Ravaud A, Oudard S, et al. Comparative efficacy of first-line immune-based combination therapies in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) (2020) 12(6):1673. doi: 10.3390/cancers12061673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Quhal F, Mori K, Bruchbacher A, Resch I, Mostafaei H, Pradere B, et al. First-line immunotherapy-based combinations for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur Urol Oncol (2021) 4(5):755–65. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2021.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Riaz IB, He H, Ryu AJ, Siddiqi R, Naqvi SAA, Yao Y, et al. A living, interactive systematic review and network meta-analysis of first-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol (2021) 80(6):712–23. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2021.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hahn AW, Klaassen Z, Agarwal N, Haaland B, Esther J, Ye XY, et al. First-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur Urol Oncol (2019) 2(6):708–15. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2019.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rücker G, Schwarzer G. Ranking treatments in frequentist network meta-analysis works without resampling methods. BMC Med Res Methodol (2015) 15:58. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0060-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kalra S, Rini BI, Jonasch E. Alternate sunitinib schedules in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol (2015) 26(7):1300–4. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ezz El Din M. Sunitinib 4/2 versus 2/1 schedule for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Tertiary care hospital experience. Clin Genitourin Cancer (2017) 15(3):e455–e62. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2016.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.