Significance

Nucleoli have long been known as the sites of rRNA synthesis and processing and more recently for production of several long non-coding (lnc) RNAs that regulate rRNA transcription and other aspects of cellular function. We now show that one such well-characterized “lncRNA,” known as PAPAS, unexpectedly encodes a 25 KDa protein that we have named RIEP (Ribosomal IGS Encoded Protein). RIEP, which is highly conserved in primates but not present in other species, localizes to mitochondria as well as nucleoli and relocalizes to nuclear regions upon stress, where it functions to prevent stress-induced DNA damage. Our study provides important insights into nucleolar function, unexpected properties of lncRNAs, and possible new connections between mitochondria and nucleoli in response to stress.

Keywords: lncRNA, nucleolus, mitochondria, stress

Abstract

Certain long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are known to contain small open reading frames that can be translated. Here we describe a much larger 25 kDa human protein, “Ribosomal IGS Encoded Protein” (RIEP), that remarkably is encoded by the well-characterized RNA polymerase (RNAP) II-transcribed nucleolar “promoter and pre-rRNA antisense” lncRNA (PAPAS). Strikingly, RIEP, which is conserved throughout primates but not found in other species, predominantly localizes to the nucleolus as well as mitochondria, but both exogenously expressed and endogenous RIEP increase in the nuclear and perinuclear regions upon heat shock (HS). RIEP associates specifically with the rDNA locus, increases levels of the RNA:DNA helicase Senataxin, and functions to sharply reduce DNA damage induced by heat shock. Proteomics analysis identified two mitochondrial proteins, C1QBP and CHCHD2, both known to have mitochondrial and nuclear functions, that we show interact directly, and relocalize following heat shock, with RIEP. Finally, it is especially notable that the rDNA sequences encoding RIEP are multifunctional, giving rise to an RNA that functions both as RIEP messenger RNA (mRNA) and as PAPAS lncRNA, as well as containing the promoter sequences responsible for rRNA synthesis by RNAP I. Our work has thus not only shown that a nucleolar “non-coding” RNA in fact encodes a protein, but also established a novel link between mitochondria and nucleoli that contributes to the cellular stress response.

Non-coding RNAs are abundant in the human genome, constituting about 70% of the transcriptome (1). In general, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are by definition non-protein-coding. However, some have been reported to possess small open reading frames (ORFs) that can be translated and encode polypeptides that function in various ways (2–4). Consistent with an mRNA-like function, most lncRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase (RNAP) II and capped, and many are spliced and polyadenylated (5–7). While these RNAs must localize to the cytoplasm to be translated, many lncRNAs remain nuclear and are often unstable (3, 8, 9).

The nucleolus has long been known as the site of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) synthesis (by RNAP I) and processing. But in recent years, a number of lncRNAs transcribed in the nucleolus, by RNAP II as well as RNAP I, have been described (10–13). One such RNA, designated “promoter and pre-rRNA antisense (PAPAS), is estimated to be about 12 to 15 kb long and extends, in the antisense direction, across the rDNA gene body and adjacent intergenic spacer regions (14). PAPAS is transcribed by RNAP II, and its abundance is modulated by several factors, including for example by heat shock (HS) and other stresses (14–16). PAPAS, levels of which are low in normally growing cells (11), accumulates and functions to repress rRNA transcription in response to stress, by recruiting epigenetic regulators, such as the histone methyltransferase Suv4-20h2 and the chromatin remodeler CHD4/NuRD, to rDNA promoters (17, 18). PAPAS is also capable of forming cotranscriptional R loops, which can contribute to rRNA repression (15). Thus, PAPAS plays a significant role in fine-tuning rRNA transcription in response to cellular stress. But a protein-coding function for PAPAS, or indeed any nucleolar-transcribed lncRNA, has not been suggested.

Here we describe experiments designed to investigate the possibility that PAPAS is capable of encoding a protein. Unexpectedly, we identify a long open reading frame (ORF) in PAPAS, which overlaps the rRNA promoter region, and show that it is indeed expressed. Using a variety of methods, we obtain insights into the subcellular locations and function of the protein, which we have named RIEP. Our findings show that rDNA in human nucleoli encodes a protein, which appears to have evolved only recently, that functions in the cellular response to stress, and that provides a link between the cell’s major energy producer, mitochondria, and its major energy consumer, the nucleolus.

Results

Discovery of a Conserved Protein, RIEP, Encoded by the “lncRNA” PAPAS.

Our previous work revealed that certain naturally unstable nuclear lncRNAs could under appropriate conditions be transported to the cytoplasm and even translated (19). Despite the fact that PAPAS is a nucleolar-transcribed and apparently nucleolar-localized lncRNA, we asked whether human PAPAS might contain one or more ORF that could potentially encode a functional protein. Given that PAPAS sequences antisense to the 47S rRNA will by necessity be more constrained, we focused on sequences within the rDNA intergenic spacers, especially around the rDNA promoter and upstream enhancer. We used ExPASy (20) to predict potential protein-coding sequences and identified two ORFs (ORF1 and ORF2) with ATG start codons (Fig. 1A). ORF1 encodes a polypeptide of 26 aa and ORF2 one of 229 aa, which we chose to analyze further. Even though ribosomal gene IGS regions are not conserved across species (21, 22), the ORF2 coding sequence is highly conserved, albeit only in primates (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). The ORF2 amino acid sequence, which we have named RIEP, is shown (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). Strikingly, the RIEP amino acid sequence is also conserved in primates, although with substitutions and several small in-frame deletions and insertions, largely toward the C terminus (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). It is also notable that the putative protein is highly positively charged with a pI of 12.4. If PAPAS is indeed capable of being transported to the cytoplasm and translated, then it should be polyadenylated, which is indeed the case (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A).

Fig. 1.

The non-coding RNA PAPAS encodes a novel nucleolar protein, RIEP. (A) Two putative ORFs in PAPAS, located upstream of 47S pre-rRNA transcription start site, were predicted by ExPASy. Their positions relative to the 47S pre-rRNA transcription start site are indicated. (B) Expression of Flag-RIEP was detected by WB with anti-Flag antibodies in Flag-RIEP but not vector-alone HeLa cells. U2AF65 serves as a loading control. (C) Representative IF images of Flag-RIEP and NPM1 in Flag-RIEP HeLa cells. Flag-RIEP was detected by Flag antibodies (red), nucleophosmin (NPM1) by NPM1 antibodies (green) and DNA by DAPI (blue). (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (D) Selected cells from Fig. 1C, (scale bar, 5 μm.) (E) Chromatin immunoprecipitation of Flag-RIEP at rDNA loci. Schematic at top indicates the rDNA locus and positions of primer pairs used to detect rDNA promoter, upstream core element (UCE), 5′ and 3′ External Transcribed Spacer (ETS), gene body (H8), IGSs (H18, IGS22, H27, IGS28), ORF2 and ORF1 regions, and two RNAP II-transcribed nuclear genes (GAPDH and LIG3). Values from vector-transformed cells (vector) were set at 1.0, and relative values from Flag-RIEP cells (Flag-RIEP) are shown. Data are presented as SE (n = 3).

To investigate if RIEP is actually made, and if so how it might function, we first established a HeLa stable cell line expressing Flag-RIEP. A Flag signal of the appropriate MW (~25 KDa) was detected by western blot (WB) in cell lysates prepared from the Flag-RIEP cells, but not in lysates from the vector-alone transformed cells (Fig. 1B). To confirm expression of Flag-RIEP and determine its subcellular localization, we next carried out immunofluorescent (IF) staining of Flag-RIEP and control cells with anti-Flag antibodies. Strikingly, we found that Flag-RIEP was indeed expressed and localized predominantly in the nucleolus, as we observed strong Flag-RIEP puncta in nucleoli that co-localized with nucleophosmin (NPM1), a nucleolar marker (Fig. 1 C and D). Flag IF also revealed weaker Flag-RIEP staining at the nuclear periphery and in the cytoplasm (Figs. 1 C and D and 2A). Consistent with these results, WB of fractionated Flag-RIEP and vector cell extracts showed Flag-RIEP predominantly in the nucleolar fraction together with two nucleolar markers, nucleolin and fibrillarin, with weaker signals in the cytoplasmic and nucleoplasmic fractions (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). Furthermore, and consistent with the observed nucleolar localization, RIEP is predicted by the nucleolar localization sequence detector NoD (23, 24) to have three potential nucleolar localization signals (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C).

Fig. 2.

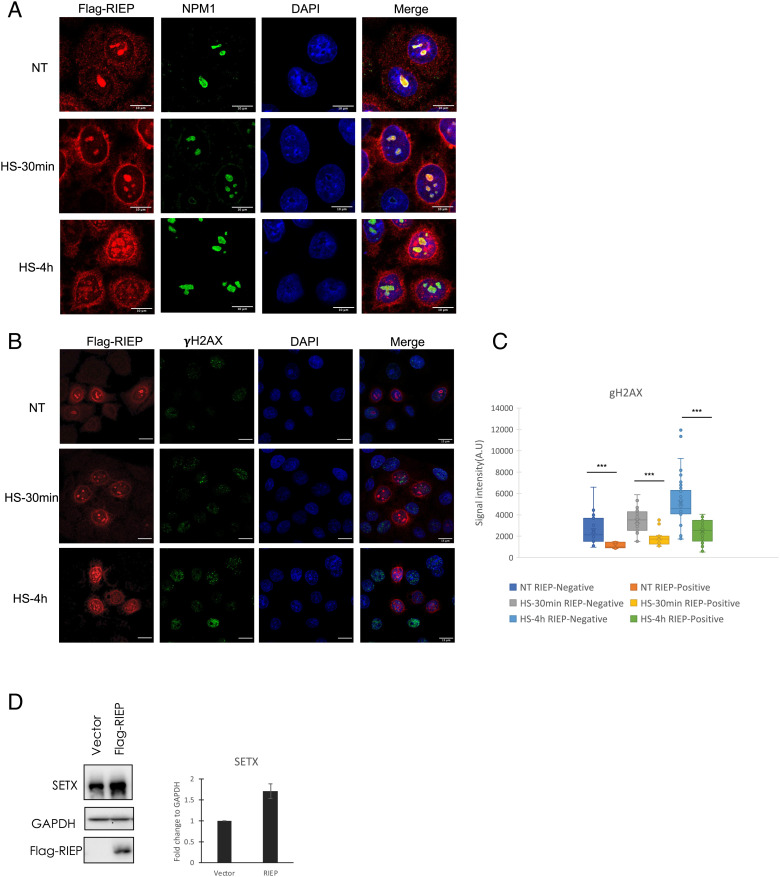

RIEP relocalizes and functions to prevent DNA damage following heat shock. (A) IF representative images showing exogenous Flag-RIEP localization in Flag-RIEP HeLa cells at 37 °C and upon 30 min or 4 h heat shock at 42 °C. Cells were stained for Flag-RIEP (red), NPM1 (green) and DNA with DAPI (blue). (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (B) IF representative images showing less γH2AX in Flag-RIEP expressing cells. Flag-RIEP HeLa were cultured at 37 °C and after 30 min or 4 h heat shock at 42 °C, cells were fixed and analyzed by IF. Flag antibodies (red) and γH2AX antibodies (green) were used and DNA detected with DAPI (blue). (C) Box plot quantification of γH2AX focus intensity per cell as shown in B. Significance was analyzed by Student’s t test. (***) P < 0.001. At least 50 cells were counted under each condition. (D) SETX levels were analyzed by WB in Flag-Vector and Flag-RIEP HeLa cells. GAPDH levels are also shown. Relative SETX levels were quantitated and presented as fold change, shown as mean, SE (n = 3).

To extend the above results, we next asked whether RIEP can associate with rDNA, using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to detect possible interaction of Flag-RIEP with rDNA. We performed Flag ChIP in both vector-alone and Flag-RIEP cells and observed significant Flag-RIEP signals across the rDNA locus (Fig. 1E). However, we did not detect Flag-RIEP signals above background at two nuclear RNAP II-transcribed genes, GAPDH and LIG3 (Fig. 1E).

We next asked whether depleting RIEP-encoding sequences affected nucleolar structure, as a first measure of possible RIEP function. We transfected two different siRNAs targeting PAPAS into HeLa cells, then evaluated nucleolar morphology by IF. PAPAS KD efficiency was measured by RT-qPCR (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). Nucleolar morphology was evaluated using an antibody targeting RPA 194 (the largest subunit of RNAP I). We observed that loss of RIEP-encoding sequences significantly reduced RPA194 foci number, an indication of disrupted nucleolar structure (15) (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B and C). While these effects on RPA194 foci cannot be attributed conclusively to loss of RIEP, as opposed to PAPAS RNA, the localization of Flag-RIEP to nucleoli (Fig. 1 C and D), and specifically to rDNA (Fig. 1E), supports a role for RIEP in maintenance of nuclear structure and function.

RIEP Levels respond to Heat Shock.

Many proteins are known to reside in the nucleolus and function in nucleolar reorganization in response to cellular stress (25). Additionally, PAPAS transcript levels have been found to increase substantially in mouse cells upon heat shock (HS) (14). We therefore next asked if PAPAS levels also increase in human cells upon HS. To this end, we measured PAPAS RNA levels in HeLa cells following heat shock by RT-qPCR and observed a significant increase (over 50-fold; SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), consistent with the findings in mice (14).

Given the response of PAPAS levels to HS, we next investigated how RIEP levels might respond. We initially used the Flag-RIEP cells described above and measured Flag-RIEP levels following HS by Flag WB. Strikingly, we found that protein levels were increased, by 3.5-fold, after 4 h HS (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B, quantitation in SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). This was especially notable because Flag-RIEP was expressed from a complementary DNA (cDNA) transgene with a heterologous promoter, suggesting that the increase arose posttranscriptionally. We next conducted IF to observe how the localization of Flag-RIEP might change upon HS. As above, we found that Flag-RIEP was predominantly localized to the nucleolus, with some weaker signals detected in the nucleus and cytoplasm of non-heat-shocked cells (Fig. 2A, NT). Interestingly, increased localization in the nucleus and especially nuclear periphery was observed after HS treatment for 30 min and 4 h (Fig. 2A). Thus, both the abundance and localization of Flag-RIEP change following HS, suggesting a possible function in the HS response.

RIEP Prevents Heat Shock-Induced DNA Damage.

Heat shock induces multiple cellular responses. Among these are elevated DNA damage (26, 27), which includes increased histone H2AX phosphorylation at serine 139 (γH2AX; 27). Therefore, to examine possible RIEP function in HS, we evaluated γH2AX levels following HS treatment of HeLa cells. We found by WB as expected a significant increase of γH2AX in response to HS after 4 h (SI Appendix, Fig. S4D). More importantly, while γH2AX protein levels were increased in both vector and Flag-RIEP HeLa cells, the increase was lower in the Flag-RIEP cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B, quantitation in SI Appendix, Fig. S4E). To extend these results, we also examined γH2AX levels in Flag-RIEP cells after HS by IF. This analysis took advantage of the fact that, for unknown reasons, more than 65% of the stably transfected Flag-RIEP cells do not express detectable levels of Flag-RIEP. Strikingly, we observed that cells expressing Flag-RIEP exhibited far less γH2AX foci than did cells not expressing Flag-RIEP (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S4F, quantitation in Fig. 2C). Note that because Flag-RIEP is only expressed in a fraction of the cells, these results also indicate that the observed reduction in γH2AX detected by WB underestimates the effects of Flag-RIEP expression. Together, our results provide strong evidence that RIEP functions to prevent DNA damage.

How might RIEP help combat DNA damage? Previous studies showing that the RNA:DNA helicase Senataxin (SETX) is involved in R loop-dependent DNA damage repair (15, 28, 29) suggested a possibility, given that such DNA damage occurs in nucleoli and can be exacerbated by loss of SETX (15). Therefore, we first examined whether SETX was also regulated by HS. We observed a sharp decrease in SETX levels upon HS treatment (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). Reduced SETX levels were also observed previously in response to camptothecin-induced DNA damage (15). Interestingly, Flag-RIEP cells displayed elevated levels of SETX (Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). And importantly, SETX was maintained at high levels in Flag-RIEP cells in response to HS treatment for 30 min, compared to vector-alone cells, although with HS treatment for 4 h, SETX levels were decreased in both vector and Flag-RIEP cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). It is noteworthy that, as we observed with γH2AX, these results underestimate the effects of RIEP on SETX levels, as Flag-RIEP is not expressed in all cells (see above). Therefore, it is possible that elevated SETX levels brought about by RIEP account at least in part for the reduced DNA damage, i.e., γH2AX, in the Flag-RIEP cells.

RIEP Interacts and Colocalizes with Mitochondrial Proteins.

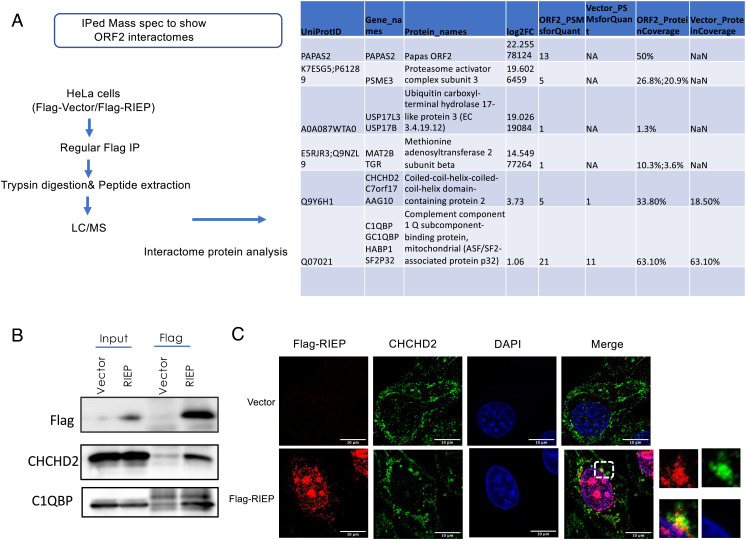

To explore RIEP function further, we determined the Flag-RIEP interactome by performing Flag-RIEP immunoprecipitation (IP)/mass spectrometry (Fig. 3A). We obtained over 900 possible interacting proteins (SI Appendix, Table S1), and the top five highest confidence candidates are listed in Fig. 3A. Interestingly, two of these were mitochondrial proteins, CHCHD2 and C1QBP (P32). Interactions between RIEP and both CHCHD2 and C1QBP were validated by IP-WB (Fig. 3B). Notably, CHCHD2 and C1QBP localize to both the mitochondria and nucleus and play functional roles in the nucleus and in mitochondrial stress responses (30–32). Therefore, we further evaluated possible RIEP localization in mitochondria, as well as interaction with CHCHD2. For this, we transiently expressed Flag-RIEP in HeLa cells and then determined localization of Flag-RIEP and CHCHD2 by IF. The results (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Fig. S5B) indeed revealed that Flag-RIEP and CHCHD2 colocalize. These findings thus provide evidence that RIEP interacts with mitochondrial proteins and may play a role in the mitochondrial stress response.

Fig. 3.

RIEP interacts with mitochondrial proteins CHCHD2 and C1QBP (P32). (A) Immunoprecipitation mass spectrometry analysis of Flag-RIEP from HeLa cells. Top five targets are listed. (B) Immunoprecipitation of Flag-RIEP from vector or Flag-RIEP HeLa cells. Flag-RIEP, CHCHD2, and C1QBP (P32) were detected by WB using appropriate antibodies. (C) IF analysis of HeLa cells transiently expressing vector or Flag-RIEP. Cells were stained for Flag (red), CHCHD2 (green), or with DAPI (blue). Areas highlighted in the “Merge” fields are shown enlarged at the right. (Scale bars, 10 μm.)

RIEP is Expressed Endogenously and Behaves Similarly to Exogenous Flag-RIEP.

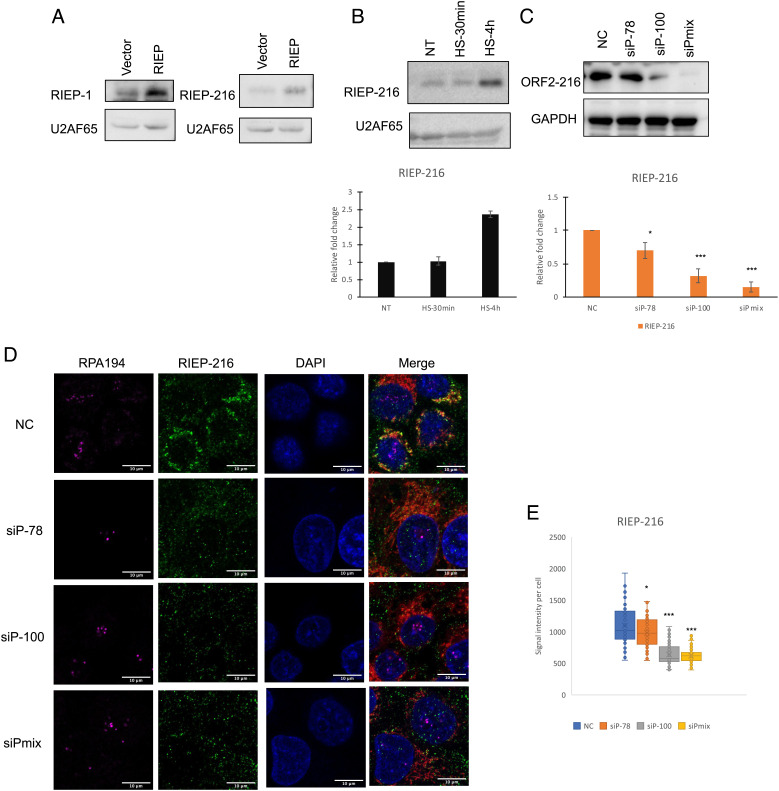

The above experiments were all performed with cells expressing exogenous Flag-tagged RIEP. An important question is whether RIEP is in fact made endogenously. To address this, we generated two polyclonal rabbit anti-RIEP antibodies recognizing the N terminus (RIEP-1) or C terminus (RIEP-216). We performed WB with extracts from the vector-alone or Flag-RIEP HeLa cells described above. A band corresponding in size to RIEP was detected by both antibodies in the vector-alone cell extracts, and significantly increased signals were detected by each of the antibodies in the Flag-RIEP cells (Fig. 4A). While signals for RIEP were low in normally growing HeLa cells, we observed increased RIEP levels by WB following HS for 30 min or 4 h with RIEP-216 (Fig. 4B, quantitation at bottom). These results are consistent with the anti-Flag WB results shown above (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 B and C). RIEP antibody specificity was evaluated by WB following siRNA-mediated KD. HeLa cells were transected with two different siRNAs targeting PAPAS (siP-78 and siP-100) or a mixture of these two siRNAs. Decreased RIEP signals were detected using RIEP-216 antibody (Fig. 4C; quantitation at bottom).

Fig. 4.

Expression and localization of endogenous RIEP. (A) Detection of endogenous RIEP in vector and Flag-RIEP HeLa cells by WB, using RIEP-1 or RIEP-216 antibodies directed against N- or C-terminal RIEP epitopes, respectively. (B) Detection of endogenous RIEP by WB with RIEP-216 in HeLa cells at 37 °C and following 30 min or 4 h heat shock at 42 °C. Quantification of relative RIEP-216 levels in HeLa cells, normalized to U2AF65 and compared with NT, is shown below. SE is shown. n = 3. (C) Endogenous RIEP levels were determined by WB with RIEP-216 in extracts from vector and Flag-RIEP HeLa cells, treated with an siRNA negative control (NC), two different siRNAs targeting RIEP/PAPAS (siP-78 or siP-100) or a mix of the two siRNAs (siPAPASs) for 72 h. Quantification of relative RIEP levels after RIEP KD as shown in C, normalized to GAPDH and compared with NC, is shown below. SE is shown. n = 3. Significance was analyzed by a Student’s t test. (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001). (D) HeLa cells were transfected with an siRNA negative control (NC), two different siRNAs targeting RIEP/PAPAS (siP-78 or siP-100), or a mix of the two siRNAs targeting PAPAS (siPAPASs) for 72 h. Cells were stained for RIEP using RIEP-216. Pol I (RPA 194, purple), RIEP (green), MitoTracker (red), or DAPI (blue) staining are shown. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (E) Box plot quantification of RIEP foci intensity detected by C terminus RIEP-216 antibody per cell as shown in E.

We also examined endogenous RIEP levels and localization by IF. We first used the RIEP-216 antibody in HeLa cells transfected with a negative control siRNA (NC) or the two PAPAS siRNAs, alone or together. We observed strong RIEP staining that was significantly reduced by the PAPAS siRNAs, providing additional evidence for the specificity of the anti-RIEP antibodies (Fig. 4D; quantitation is in Fig. 4E). It is notable that under these conditions, the strong nucleolar staining observed with Flag-RIEP was not detected. Although the reason for this is not clear, it may reflect in part RIEP accumulation levels or some other difference between the cells. This is consistent with the fact that endogenous RIEP staining more resembled that of Flag-RIEP staining after HS, i.e., much greater staining around the nuclear periphery (Fig. 2A; see also below). To address this issue further, RIEP localization was evaluated by IF with both RIEP antibodies in the Flag-RIEP HeLa cells, comparing Flag and RIEP antibody staining. We indeed observed significant colocalization between Flag-RIEP and endogenous RIEP with or without HS (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and B). Note that as expected, colocalization was greater after HS, and significant nucleolar signals were detected with Flag and both RIEP antibodies. These results together establish that RIEP is indeed expressed endogenously in HeLa cells and provide evidence that its levels are elevated upon HS.

Endogenous RIEP Localizes with Mitochondria and Responds to Heat Shock.

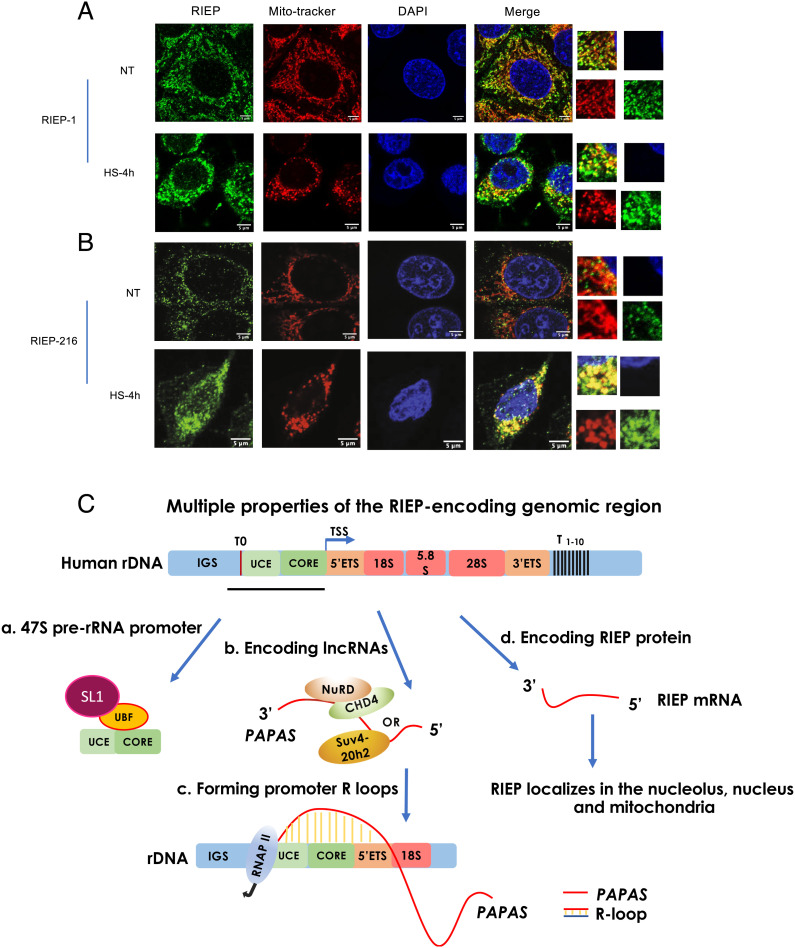

We next wished to investigate further RIEP cytoplasmic localization, as well as the possible role of RIEP in mitochondria. To this end, we first used MitoTracker red to label mitochondria in live HeLa cells and then examined colocalization with RIEP by IF. We indeed observed RIEP punctate staining that co-localized with MitoTracker, using both RIEP-1 (Fig. 5A) and RIEP-216 (Fig. 5B) antibodies. Mitochondria are known to redistribute to the perinuclear region upon HS (33), and RIEP also showed a perinuclear clustering phenotype upon heat stress (Fig. 5 A and B). This is also consistent with Flag-RIEP localization following heat shock (Fig. 2A above and SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and B). We also examined RIEP mitochondrial localization in response to heat stress by co-staining with CHCHD2, and this also revealed perinuclear staining following HS (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). Mitochondrial perinuclear accumulation induced by heat shock is known to be reversible following return to physiological temperature (33), and RIEP re-distribution was also observed following recovery from HS for 30 min or 1 h (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). We also observed significantly increased RIEP in nuclei following HS (Fig. 5 A and B, quantitation in SI Appendix, Fig. S7 B and C). This may reflect the nucleolar localization observed with Flag-RIEP (e.g., Fig. 1C) and is also similar to the behavior of Flag-RIEP observed following HS (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 5.

RIEP plays a role in the mitochondrial heat shock stress response. HeLa cells were untreated or heat-shocked for 4 h. Cells were stained using RIEP antibodies recognizing the N terminus (RIEP-1) (A) or C terminus (RIEP-216) (B). RIEP (green), MitoTracker (red), or DAPI (blue) staining are shown. (Scale bar, 5 μm.) (C) Illustration of multiple properties of the RIEP-encoding genomic region. One repeat of the human rDNA arrays is diagrammed. The locus contains 47S pre-rRNA coding sequences (TSS indicated by arrow, positions of 5′ and 3′ ETSs, 18S, 5.8S, and 28S rRNAs are shown), the IGS region, and the pre-RNA promoter (UCE and ribosomal gene core element (CORE)). Position of RIEP coding sequence is indicated by the black line under the diagram, and terminators (T) are shown above. (a) 47S pre-rRNA promoter, including transcription factors UBF and SL1. (b) LncRNA PAPAS and interacting chromatin remodeling factors. (c) R loop-forming sequences. (d) RIEP mRNA and protein.

We showed above by ChIP that Flag-RIEP associates with the rDNA locus but not with nuclear RNAP II-transcribed genes. To investigate whether nuclear-localized endogenous RIEP behaves similarly, we performed ChIP assays with RIEP-216 antibodies, using HeLa cells with or without 4 h HS. The results (SI Appendix, Fig. S7D) revealed minimal RIEP association with chromatin in the absence of HS, but strong signals (~threefold to sevenfold increased) across the rDNA locus, but not with GAPDH, following HS. These results are consistent not only with the Flag-RIEP ChIP results (Fig. 1E), but also with the relative abundance and localization of RIEP in normal and heat-shocked HeLa cells, and strengthen the view that RIEP function involves association with rDNA loci. Interestingly, the RIEP-interacting proteins CHCHD2 and C1QBP both translocate from mitochondria to the nucleus following stress, where they function as transcription factors (30–32). Whether or not this is relevant to RIEP function remains to be determined. Together our results suggest that RIEP provides a mitochondria-nucleoli link that functions in response to heat shock stress.

Discussion

It has long been thought that nucleoli are dedicated sites of rRNA transcription and processing, as well as assembly of pre-ribosomal particles, but not sites of mRNA production. Our results challenge this paradigm by establishing that a nucleolar synthesized RNA, transcribed by RNAP II but thought to be non-coding, can in fact function as an mRNA, encoding a protein, RIEP, that not only functions in nuclear/mitochondrial stress responses, but also can localize to nucleoli and associate with rDNA (Fig. 5C). We note that there is one previous example of a nucleolar-encoded protein, dubbed TAR1 (34, 35). TAR1 is a small ~120 residue polypeptide found only in S. cerevisiae and closely related species and is produced by transcription antisense to rRNA (34, 36). Notably, like RIEP, TAR1 has been implicated in mitochondrial function, although the proteins are unrelated in sequence (34, 36). Our work thus strengthens links between mitochondria and nucleoli and at the same time suggest the possible existence of additional nucleolar-encoded proteins that remain to be discovered.

The RIEP coding region resides in the rDNA intergenic spacer just 5’ to the rRNA transcription start site. This region is thus remarkable in that it appears to possess multiple distinct functions (Fig. 5C). In addition to encoding RIEP, the DNA contains promoter/regulatory sequences for rRNA transcription (37, 38), encodes PAPAS RNA sequences responsible for lncRNA function, e.g., by recruiting the repressive chromatin remodeling CHD4/NuRD complex (13, 14), and the RNA is also prone to regulatory R loop formation (6, 15). This constitutes a striking overlap of genetic information, and fascinating questions include how this may have evolved, with RIEP emerging only in primates, and whether such multifunctional sequences exist elsewhere in the human genome. In any event, our results emphasize the fact that putative lncRNAs, even when transcribed in the nucleolus, can encode proteins, thereby expanding the coding potential of the human genome and blurring the difference between coding and non-coding RNAs.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and Reagents.

Antibodies recognizing the Flag tag (Sigma,F1804), SETX (Novus, NBP1-94712), RNA polymerase I (RPA194 (C-1) (Santa Cruz, sc-48385), fibrillarin (G-8) (Santa Cruz, sc-374022), nucleophosmin (NPM1, Forties Life Sciences A302-403A-T), C1QBP/P32 (Proteintech, 24474-1-AP), CHCHD2 (Proteintech, 66302-1-lg), GAPDH (Sigma-Aldrich, G9545), U2AF65 (Sigma-Aldrich, U4758), H3 (Abcam, ab8898), phospho-histone H2A.X(Ser139) (Cell signaling, 2577), and MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Invitrogen, M7512) were obtained from the indicated vendors. Human RIEP rabbit polyclonal antibodies were generated at Bethyl Laboratories/Fortis Life Sciences. RIEP-1 and RIEP-216 antibodies recognize peptides derived from the RIEP N terminus or C terminus, respectively. IGPAL-CA-630 (Sigma, I8896), cOmplete™, Mini, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche, 04693159001), and Pierce™ Protein A/G Magnetic Beads (Thermo Fisher scientific, 88802) were purchased from indicated vendors.

Cell Culture and Generating Flag-RIEP Expressing Stable Cells.

HeLa cells were from a common laboratory stock and grown in 10% fetal bovine serum Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium. The RIEP coding sequence was cloned into pcDNA3-3×Flag vector by PCR. Sequences were determined by Genewiz. For plasmid transfection, 3 × 105 HeLa cells were transfected with 2 μg of empty vector or Flag-RIEP plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Transfected cells were stained for transient expression after 24 h or subjected to G418 (500 μg/mL) selection to create stable cell lines. Stable cells were cultured with G418 at 250 μg/mL to select for cells maintaining the Flag-RIEP plasmid.

siRNAs Transfection and Western Blots.

Vector or Flag-RIEP HeLa cells were transfected with the siRNA control NC (TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT), siPAPAS-78 (GTCGCCTGGGCCGGCGGCGT), and siPAPAS-100 (GGGGACAGGTGTCCGTGTCGC), for 72 h at 20 nM with RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, 13778). Cells were harvested and dissolved in SDS loading buffer, and proteins separated by sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Then, proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, IPVH00010) according to standard semi-dry transfer protocols (39). Membranes were blocked in 7.5% milk-Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 detergent (TBST) blocking buffer for 30 min at room temperature (RT) followed by overnight incubation with the primary antibody diluted in Protein-Free Tris-buffered saline (TBS) blocking buffer (Thermo Scientific, 37570) (1:1,000), except for GAPDH, U2AF65, and H3 (1:10,000). Secondary antibody was added at 1:25,000 for 30 min at room temperature in TBST + 7.5% milk. Blots were incubated with chemiluminescence RT for 2 to 3 min, and signals were captured with a ChemiDoc MP Imaging system (Bio-Rad). All protein signals were normalized to GAPDH, U2AF65, or H3.

Immunofluorescence.

HeLa cells expressing vector alone or Flag-RIEP were prepared for IF following a previously described protocol and cultured on glass coverslips coated with 1% gelatin (15). To label mitochondria, prior to IF, cells were labeled with 200 μM MitoTracker Red CMXRos for 30 min. Generally, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for 20 min, then permeabilized with 0.1% TritonX-100 in the cold for 20 min. Cells were washed 3 times using TBST, then incubated with Protein-Free (TBS) blocking buffer (Thermo Scientific, 37570) at RT for 1 h. Then cells were incubated with primary antibody: anti-Flag, NPM1, endogenous RIEP-1, RIEP-216, or RPA194 (1:500 dilution) overnight in the cold room. After washing three times with TBST, cells were incubated with the appropriate secondary fluorescence-conjugated antibody (Alexa Fluor 488 Goat anti-Rabbit IgG or Alexa Fluor 568 Goat anti-Mouse IgG, 1:500 dilution, Thermo Fisher) diluted with blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were mounted on slides with mounting buffer containing DAPI (Thermo Fisher) for imaging using a Zeiss Zen confocal microscope 700 with 63× oil objective. Images were recorded with the same settings. Image quantification was performed using Image J.

Flag-RIEP ChIP-qPCR.

Flag-RIEP ChIP-qPCR experiments were performed with cells expressing vector or Flag-RIEP using a standard ChIP protocol (15) to capture Flag-RIEP along the genome. Flag was immunoprecipitated overnight at 4 °C with 2 μg antibodies. DNA was purified using a PCR purification kit (QIAGEN, 28104) and collected with 300 μL elution buffer. qPCR reactions were set up by mixing 3 μL of precipitated DNA, further diluted with H2O and with Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 2008602). PCR was performed using the StepsOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Thermo Fisher). Signals were analyzed from each immunoprecipitation relative to the percent of the total input chromatin.

RT-qPCR.

RNA extraction was carried out with TRIZOL (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15596026) followed by removing DNA with a DNA-free DNA removal Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, AM1906). Real-time PCR was performed in 96-well plates with power SYBR Green using StepOnePlus (Applied Biosystems, 4367659). cDNA was reverse transcribed with Maxima reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, EP0741) and random hexamer primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific, SO142), oligo(dT)20 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 18418020), or strand-specific PCR using corresponding primers to reverse synthesis cDNA. PCR reactions were conducted by standard procedures, reactions were denatured at 95 °C for 10 min, and 40 cycles of PCR were performed at 95 °C for 15 s, following with 60 °C for 60 s for each cycle. All probes used for qPCR in this study are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1.

Immunoprecipitation.

Vector or Flag-RIEP HeLa cells were lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-cl (PH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% IGPAL-CA-630, 5% Glycerol, protease) for 30 min. The soluble fractions were collected by centrifugation for 15 min at 15,000 rpm and incubated with 5 µg Flag antibody overnight in the cold room. Cell lysates were then incubated with antibody and magnetic beads for 1 h in the cold room, supernatants were removed, and the precipitates were washed and saved as IP samples. IP samples were subjected to immunoblotting or mass spec.

Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) Analysis.

IP samples after the last wash were resuspended in 80 μL trypsin buffer (2 M Urea, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 5 μg/mL trypsin) to digest the bound proteins at 37 °C for 1 h with agitation. The beads were centrifuged at 100 × g for 30 s, and the partially digested proteins (the supernatant) were collected. The beads were then washed twice with 60 μL Urea buffer (2 M Urea, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5]). The supernatant of both washes was collected and combined with the partially digested proteins (final volume of 200 μL). After brief centrifugation, the combined partially digested proteins were cleared from residual beads and frozen in liquid nitrogen. 100 μL of the partially digested proteins were thawed, and disulfide bonds were reduced with 5 mM dithiothreitol and cysteines were subsequently alkylated with 10 mM iodoacetamide. Samples were further digested by adding 0.5 μg sequencing grade modified trypsin (Promega) at 25 °C. After 16 h digestion, samples were acidified with 1% formic acid (final concentration). Tryptic peptides were desalted on C18 StageTips as described (40) and evaporated to dryness in a vacuum concentrator.

Half of the prepped peptides were analyzed on a Thermo Scientific Orbitrap Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer coupled via a 25 cm sub-2-μm Aurora C18 column (IonOpticks) to an Acuity M Class UPLC system (Waters). Peptides were separated at a flow rate of 400 nL/min with a linear 95 min gradient from 5 to 22% solvent B (100% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid), followed by a linear 30 min gradient from 22 to 90% solvent B. Each sample was run for 160 min, including sample loading and column equilibration times. Data were acquired in data-dependent mode using Xcalibur 4.1 software. MS1 Spectra were measured with a resolution of 120,000, an AGC target of 3e6, and a mass range from 300 to 1,800 m/z. Up to 12 MS2, spectra per duty cycle were triggered at a resolution of 15,000, an AGC target of 1e5, an isolation window of 1.6 m/z, and a normalized collision energy of 28. Raw data were searched with SpectroMine (version 3.2.220222.52329) using default BSG Factory Settings and a modified Human proteome. fasta file containing all putative PAPAS ORF sequences. Log2 fold changes were calculated between vector and ORF2-containing samples to identify RIEP interactors.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis.

If data are shown as boxplots, the whisker based on three independent experiments, more than 50 cells in total. The asterisks (*** for P < 0.001) represent the significance of difference between different groups of data and is based on an unpaired Student’s t test.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Manley lab members, especially Lizhi Liu, for valuable discussions, and Alia Campbell for excellent technical assistance. Many of the results presented in this manuscript are derived from Shuang Feng’s thesis dissertation. This work was supported by NIH grant R35 GM118136. M.J. is funded by the NIH (R35GM128802; R01AG071869 and R01HG012216) and NSF (Award 2224211).

Author contributions

S.F. and J.L.M. designed research; S.F., A.D., and A.R. performed research; S.F., A.D., A.R., M.J., and J.L.M. analyzed data; and S.F. and J.L.M. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Reviewers: T.P., University of Massachusetts Medical School; and N.J.P., Sir William Dunn School of Pathology.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Iyer M. K., et al. , The landscape of long noncoding RNAs in the human transcriptome. Nat. Genet 47, 199–208 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingolia N. T., Lareau L. F., Weissman J. S., Ribosome profiling of mouse embryonic stem cells reveals the complexity and dynamics of mammalian proteomes. Cell 147, 789–802 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsumoto A., et al. , mTORC1 and muscle regeneration are regulated by the LINC00961-encoded SPAR polypeptide. Nature 541, 228–232 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson D. M., et al. , A micropeptide encoded by a putative long noncoding RNA regulates muscle performance. Cell 160, 595–606 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Statello L., Guo C. J., Chen L. L., Huarte M., Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 96–118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uszczynska-Ratajczak B., Lagarde J., Frankish A., Guigo R., Johnson R., Towards a complete map of the human long non-coding RNA transcriptome. Nat. Rev. Genet 19, 535–548 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lagarde J., et al. , High-throughput annotation of full-length long noncoding RNAs with capture long-read sequencing. Nat. Genet 49, 1731–1740 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrews S. J., Rothnagel J. A., Emerging evidence for functional peptides encoded by short open reading frames. Nat. Rev. Genet 15, 193–204 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bazzini A. A., et al. , Identification of small ORFs in vertebrates using ribosome footprinting and evolutionary conservation. EMBO J. 33, 981–993 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abraham K. J., et al. , Nucleolar RNA polymerase II drives ribosome biogenesis. Nature 585, 298–302 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bierhoff H., et al. , Quiescence-induced LncRNAs trigger H4K20 trimethylation and transcriptional silencing. Mol. Cell 54, 675–682 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bierhoff H., Schmitz K., Maass F., Ye J., Grummt I., Noncoding transcripts in sense and antisense orientation regulate the epigenetic state of ribosomal RNA genes. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 75, 357–364 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng S., Manley J. L., Beyond rRNA: Nucleolar transcription generates a complex network of RNAs with multiple roles in maintaining cellular homeostasis. Genes Dev. 36, 876–886 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Z., Senturk N., Song C., Grummt I., lncRNA PAPAS tethered to the rDNA enhancer recruits hypophosphorylated CHD4/NuRD to repress rRNA synthesis at elevated temperatures. Genes Dev. 32, 836–848 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng S., Manley J. L., Replication protein A associates with nucleolar R loops and regulates rRNA transcription and nucleolar morphology. Genes Dev. 35, 1579–1594 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Z., Dammert M. A., Grummt I., Bierhoff H., lncRNA-induced nucleosome repositioning reinforces transcriptional repression of rRNA genes upon hypotonic stress. Cell Rep. 14, 1876–1882 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pirogov S. A., Gvozdev V. A., Klenov M. S., Long noncoding RNAs and stress response in the nucleolus. Cells 8, 668 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lafontaine D. L., Noncoding RNAs in eukaryotic ribosome biogenesis and function. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 11–19 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogami K., et al. , An Mtr4/ZFC3H1 complex facilitates turnover of unstable nuclear RNAs to prevent their cytoplasmic transport and global translational repression. Genes Dev. 31, 1257–1271 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gasteiger E., et al. , ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3784–3788 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wehner S., Dorrich A. K., Ciba P., Wilde A., Marz M., pRNA: NoRC-associated RNA of rRNA operons. RNA Biol. 11, 3–9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agrawal S., Ganley A. R. D., The conservation landscape of the human ribosomal RNA gene repeats. PLoS One 13, e0207531 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott M. S., Troshin P. V., Barton G. J., NoD: A nucleolar localization sequence detector for eukaryotic and viral proteins. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 317 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott M. S., Boisvert F. M., McDowall M. D., Lamond A. I., Barton G. J., Characterization and prediction of protein nucleolar localization sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 7388–7399 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boulon S., Westman B. J., Hutten S., Boisvert F. M., Lamond A. I., The nucleolus under stress. Mol. Cell 40, 216–227 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Velichko A. K., Markova E. N., Petrova N. V., Razin S. V., Kantidze O. L., Mechanisms of heat shock response in mammals. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 70, 4229–4241 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaneko H., Igarashi K., Kataoka K., Miura M., Heat shock induces phosphorylation of histone H2AX in mammalian cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 328, 1101–1106 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richard P., Feng S., Manley J. L., A SUMO-dependent interaction between Senataxin and the exosome, disrupted in the neurodegenerative disease AOA2, targets the exosome to sites of transcription-induced DNA damage. Genes Dev. 27, 2227–2232 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skourti-Stathaki K., Proudfoot N. J., A double-edged sword: R loops as threats to genome integrity and powerful regulators of gene expression. Genes Dev. 28, 1384–1396 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huttlin E. L., et al. , Dual proteome-scale networks reveal cell-specific remodeling of the human interactome. Cell 184, 3022–3040.e3028 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Floyd B. J., et al. , Mitochondrial protein interaction mapping identifies regulators of respiratory chain function. Mol. Cell 63, 621–632 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Antonicka H., et al. , A high-density human mitochondrial proximity interaction network. Cell Metab. 32, 479–497.e479 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agarwal S., Ganesh S., Perinuclear mitochondrial clustering, increased ROS levels, and HIF1 are required for the activation of HSF1 by heat stress. J. Cell Sci. 133, jcs245589 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonawitz N. D., Chatenay-Lapointe M., Wearn C. M., Shadel G. S., Expression of the rDNA-encoded mitochondrial protein Tar1p is stringently controlled and responds differentially to mitochondrial respiratory demand and dysfunction. Curr. Genet. 54, 83–94 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poole A. M., Kobayashi T., Ganley A. R., A positive role for yeast extrachromosomal rDNA circles? Extrachromosomal ribosomal DNA circle accumulation during the retrograde response may suppress mitochondrial cheats in yeast through the action of TAR1. Bioessays 34, 725–729 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coelho P. S., Bryan A. C., Kumar A., Shadel G. S., Snyder M., A novel mitochondrial protein, Tar1p, is encoded on the antisense strand of the nuclear 25S rDNA. Genes Dev. 16, 2755–2760 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindstrom M. S., et al. , Nucleolus as an emerging hub in maintenance of genome stability and cancer pathogenesis. Oncogene 37, 2351–2366 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bersaglieri C., Santoro R., Genome organization in and around the nucleolus. Cells 8, 579 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richard P., et al. , SETX (senataxin), the helicase mutated in AOA2 and ALS4, functions in autophagy regulation. Autophagy 17, 1889–1906 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rappsilber J., Mann M., Ishihama Y., Protocol for micro-purification, enrichment, pre-fractionation and storage of peptides for proteomics using StageTips. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1896–1906 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.