Abstract

While recent efforts to catalogue Earth’s microbial diversity have focused upon surface and marine habitats, 12–20 % of Earth’s biomass is suggested to exist in the terrestrial deep subsurface, compared to ~1.8 % in the deep subseafloor. Metagenomic studies of the terrestrial deep subsurface have yielded a trove of divergent and functionally important microbiomes from a range of localities. However, a wider perspective of microbial diversity and its relationship to environmental conditions within the terrestrial deep subsurface is still required. Our meta-analysis reveals that terrestrial deep subsurface microbiota are dominated by Betaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria and Firmicutes , probably as a function of the diverse metabolic strategies of these taxa. Evidence was also found for a common small consortium of prevalent Betaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria operational taxonomic units across the localities. This implies a core terrestrial deep subsurface community, irrespective of aquifer lithology, depth and other variables, that may play an important role in colonizing and sustaining microbial habitats in the deep terrestrial subsurface. An in silico contamination-aware approach to analysing this dataset underscores the importance of downstream methods for assuring that robust conclusions can be reached from deep subsurface-derived sequencing data. Understanding the global panorama of microbial diversity and ecological dynamics in the deep terrestrial subsurface provides a first step towards understanding the role of microbes in global subsurface element and nutrient cycling.

Keywords: deep subsurface, 16S rRNA gene, meta-analysis, bacterial

Data Summary

The 16S rRNA gene sequencing data utilized in the present study are available on NCBI under the following project accessions: PRJNA262938, PRJNA268940, PRJNA248749, PRJNA251746, PRJNA375701, PRJEB1468 and PRJEB10822. The code used for the processing and data analysis of the datasets is available at: https://github.com/GeoMicroSoares/mads_scripts.

Introduction

Understanding the distribution of microbial diversity is pivotal for advancing our knowledge of deep subsurface global biogeochemical cycles [1, 2]. Subsurface biomass is suggested to have exceeded that of the Earth’s surface by an order of magnitude (~45 % of Earth’s total biomass) before land plants evolved, ca. 0.5 billion years ago [3]. Integrative modelling of cell count and quantitative PCR (qPCR) data and geophysical factors indicated in late 2018 that the bacterial and archaeal biomass found in the global deep subsurface may range from 23 to 31 petagrams of carbon (PgC) [4]. These values halved estimates from efforts earlier that year but maintained the notion that the terrestrial deep subsurface holds ca. 5-fold more bacterial and archaeal biomass than the deep marine subsurface [4, 5]. Further, it is expected that 20–80 % of the possible 2–6×1029 prokaryotic cells present in the terrestrial subterranean biome exist as biofilms and play crucial roles in global biogeochemical cycles [4, 6, 7].

Cataloguing microbial diversity and functionality in the terrestrial deep subsurface has mostly been achieved by means of marker gene and metagenome sequencing from aquifers associated with coals, sandstones, carbonates and clays, as well as deep igneous and metamorphic rocks [8–19]. Only recently has the first comprehensive database of 16S rRNA gene-based studies targeting terrestrial subsurface environments been compiled [4]. This work focused on updating estimates for bacterial and archaeal biomass, and cell numbers across the terrestrial deep subsurface, but also linked the identified bacterial and archaeal phylum-level compositions to host-rock type, and to 16S rRNA gene region primer targets [4]. While highlighting Firmicutes and Proteobacterial dominance in the bacterial component of the terrestrial deep subsurface, no further taxonomic insights emerged. Genus-level identification remains an important niche necessary for understanding community composition, inferred metabolism and hence microbial contributions of distinct community members to biogeochemical cycling in the deep subsurface [15, 20–22]. Indeed, such genus-specific traits have been demonstrated to be critical for understanding crucial biological functions in other microbiomes, and genus-specific functions of relevance for deep subsurface biogeochemistry are clear [23–25].

So far, the potential biogeochemical impacts of microbial activity in the deep subsurface have been inferred through shotgun metagenomics, as well as from incubation experiments of primary geological samples amended with molecules or minerals of interest [16, 17, 19, 26–29]. Recent studies of deep terrestrial subsurface microbial communities further suggest that these are metabolically active, often associated with novel uncultured phyla, and potentially directly involved in carbon and sulphur cycling [30–36]. Concomitant advancements in subsurface drilling, molecular methods and computational techniques have aided exploration of the subsurface biosphere, but serious challenges remain, mostly related to deciphering sample contamination by drilling methods, community interactions with reactive casing materials and sample transportation to laboratories for processing [37, 38]. The logistical challenges inherent in accessing and recovering in situ samples from hundreds to thousands of metres below the surface complicate our view of terrestrial subsurface microbial ecology [39].

In this study, we capitalize on the increased availability of 16S rRNA gene amplicon data from multiple studies of the terrestrial deep subsurface conducted over the last decade. We apply bespoke bioinformatics scripts to generate insights into the microbial community structure and controls upon bacterial microbiomes of the terrestrial deep subsurface across a large distribution of habitat types on multiple continents. The deep biosphere is as-yet undefined as a biome – elevated temperature, anoxic conditions, varying levels of organic carbon, and measures of isolation from the surface photosphere are some of the criteria used, albeit without a consensus. For this work a more general approach has been taken to define the terrestrial deep subsurface for the purposes of this initial examination as the zone at least 100 m from the surface [7, 40, 41].

Methods

Data acquisition

The Sequence Read Archive database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (SRA-NCBI) was queried for 16S rRNA-based deep subsurface datasets (excluding marine and ice samples, as well as any human-impacted samples); available studies were downloaded using the SRA Run Selector. Studies were selected considering their metadata and information on sequencing platform used – i.e. only samples derived from 454 pyrosequencing and Illumina sequencing were considered. Due to a lack of public availability for Illumina datasets targeting environments of interest, only 454 pyrosequencing datasets were retained. Analysis of related literature resulted in the detection of other deposited studies that previous search efforts in NCBI-SRA failed to detect. Further private contacts allowed access to unpublished data included in this study. The final list of NCBI accession numbers, totalling 222 samples, was downloaded using fastq-dump from the SRA toolkit (https://hpc.nih.gov/apps/sratoolkit.html)

As seen in Table 1, required metadata included host-rock lithology, general and specific geographical locations, depth of sampling, DNA extraction method, sequenced 16S rRNA gene region and sequencing method. Any samples for which the above-mentioned metadata could not be found were discarded and not considered for downstream analyses.

Table 1.

Metadata table for the studies utilized in this meta-analysis (see Table S3, Fig. S3 for more details)

na, Not available. The dataset unavailable through SRA is available in JGI GOLD Study ID Gs0047444.

|

SRA accession |

DOI |

Year(s) of sampling |

Final no. of samples |

Location |

Depth gradient (m) |

Host rock |

Final no. of sequences |

Final no. of OTUs |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PRJNA262938 |

10.3389/fmicb.2014.00610 |

2013/2014 |

6 |

South Dakota, USA |

243.84–1478.28 |

Sulphide-rich schists |

170 364 |

1367 |

[50] |

|

PRJNA268940 |

na |

2007–2011 |

8 |

California, USA; Ontario, Canada |

94–2383 |

Dolomite, tuff, rhyolite/tuff-breccia |

68 071 |

741 |

na |

|

PRJNA248749 |

na |

2011 |

6 |

Minnesota, USA |

730 |

Haematite iron formation |

69 757 |

511 |

na |

|

PRJNA251746 |

na |

2009 |

6 |

Washington, USA |

393–1135 |

Basalt |

30 121 |

613 |

na |

|

PRJNA375701 |

10.1016 /j.coal.2016.05.001 |

2013 |

4 |

Montana, USA |

109–114.7 |

Sub-bituminous coal, shale, sandstone, siltstone |

35 926 |

154 |

[51] |

|

na |

10.1128/AEM.01737–15 |

2009 |

27 |

Alberta, Canada |

140–1064.4 |

Sub-bituminous coal, volatile bituminous coal |

100 618 |

5110 |

[52] |

|

PRJEB1468 |

10.1111/1574–6941.12171 |

na |

6 |

Mol, Belgium |

217–232 |

Kaolinite/illite and smectite |

47 123 |

497 |

[27] |

|

PRJEB10822 |

10.5194/bg-13-3091-2016 |

2009–2011 |

7 |

Outokumpu, Finland |

180–2300 |

Mica-schist, biotite-gneiss, chlorite–sericite-schist |

12 290 |

177 |

[11] |

Pre-processing of 16S rRNA gene datasets

A customized pipeline was created in bash language making use of python scripts developed for QIIME v1.9.1, to facilitate bioinformatic analyses in this study (see https://github.com/GeoMicroSoares/mads_scripts for scripts) [42]. Briefly, demultiplexed FASTQ files were processed to create an operational taxonomic unit (OTU) table. Quality control steps involved trimming, quality-filtering and chimera checking by means of USEARCH 6.1 [43]. Sequence data that passed quality control were then subjected to closed-reference (CR) OTU-picking on a per-study basis using UCLUST and reverse strand matching against the silva v123 taxonomic references (https://www.arb-silva.de/documentation/release-123/) [43]. CR OTU picking excludes OTUs whose taxonomy has not been found in the 16S rRNA gene database used. Although this limits the recovery of prokaryotic diversity to that recorded in the database, cross-study comparisons of bacterial communities generated by different 16S rRNA gene primers are made possible. This conservative approach classified OTUs in each study individually to the common 16S rRNA gene reference database from the merging of all classification outputs. A single BIOM (Biological Observation Matrix) file was generated using QIIME’s merge_otu_tables.py script. The BIOM file was then filtered to exclude samples represented by fewer than two OTUs using filter_samples_from_otu_table.py, as well as OTUs represented by one sequence (singleton OTUs) by using filter_otus_from_otu_table.py. In an attempt to reduce the impacts of potential contaminant OTUs from the dataset, the post-singleton filtered dataset was further filtered to include only OTUs represented by at least 500 sequences and present in at least 10 samples overall using filter_otus_from_otu_table.py.

Data analysis

All downstream analyses were conducted using the phyloseq (https://github.com/joey711/phyloseq) package within R, which allowed for simple handling of metadata and taxonomy and abundance data [44–46]. Merged and filtered BIOM files were imported into R using internal phyloseq functions, which allowed further filtering, transformation and plotting of the dataset (see https://github.com/GeoMicroSoares/mads_scripts for scripts). Briefly, following a general assessment of the number of reads across samples and OTUs, tax_glom (phyloseq) allowed the agglomeration of the OTU table at the phylum level. For the metadata category-directed analyses, the function merge_samples (phyloseq) created averaged OTU tables, which permitted testing of hypotheses for whether geology or depth had significant impacts on bacterial community structure and composition. Computation of a Jensen–Shannon divergence PCoA (principal coordinate analysis) was achieved with ordinate (phyloseq), which makes use of metaMDS (vegan) [47, 48]. All figures were plotted via the ggplot2 R package (https://github.com/tidyverse/ggplot2), except for the UpsetR plot in Fig. S4, which was plotted with the package UpsetR (https://github.com/hms-dbmi/UpSetR).

Results

A total of 233 publicly available subsurface samples targeting multiple 16S rRNA gene hypervariable regions originating in nine countries were originally downloaded from the NCBI SRA database. These accounted for 24 632 035 chimera-checked sequences [11, 27, 49–53], which underwent silva 123-aided CR OTU-picking. The discovery of 46 OTUs classified as Chloroplast ( Cyanobacteria ) and phototrophic members of the phyla Chloroflexi and Chlorobi as well as orders Rhodospirillales and Chromatiales (Alpha- and Gammaproteobacteria classes, respectively) justified the use of additional stricter contamination-aware filtering (see Methodology, Table S1 for differences in numbers of reads between methods).

The final dataset consisted of 70 samples and 2207 OTUs (513 929 sequences). Seventeen aquifers were included that were associated with either sedimentary- or crystalline-host rocks, from depths spanning 94–2300 m below the land surface, targeting mostly groundwater across five countries (Table S2). Nine DNA extraction techniques were used in these studies, ranging from standard and modified kit protocols (e.g. MOBIO PowerSoil) to phenol–chloroform and CTAB/NaCl-based methods [50, 51, 54–57]. Six different primer pair amplified regions of the 16S rRNA gene with 454 pyrosequencing technology were used to generate the datasets (see Fig. S1). Metadata variables that were unavailable for all samples in the dataset were excluded from the statistical analyses. All studies followed aseptic sample handling protocols and included DNA extraction and PCR controls (for further information see Methods sections of the papers enumerated in Table 1) as per recommended guidelines for the subsurface microbiology community [38, 58].

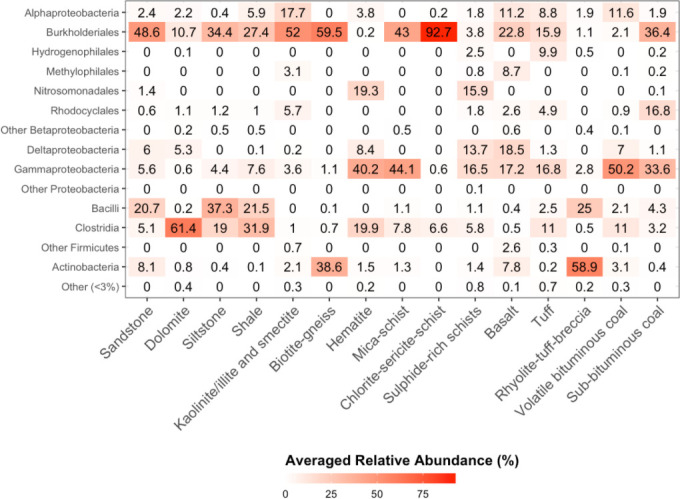

Among a total of 45 detected bacterial phyla, Proteobacteria were seen to dominate most deep subsurface community profiles in this dataset (Fig. 1). The most abundant proteobacterial classes (Alpha-, Beta-, Delta-, Gammaproteobacteria ) represented 57.2 % of the total number of reads. Betaproteobacteria , chiefly represented by the order Burkholderiales , accounted for 26.1 % of all reads in the dataset. The order Burkholderiales was the main component of some host-rocks, accounting for up to 59.5 and 92.7 % of host-rock-level relative abundance profiles for biotite-gneiss and chlorite-sericite-schist (see Fig. S2 for standard deviations of Fig. 1) and co-dominated others. Gammaproteobacteria and Clostridia ( Firmicutes ) were key components of other profiles. Clostridia and other Firmicutes accounted for large fractions of sedimentary host-rocks (dolomite, siltstone and shale) and a haematite iron formation. Finally, Actinobacteria was the most abundant taxonomic group in rhyolite-tuff-breccia.

Fig. 1.

Averaged relative abundances (coloured by increasing percentage abundance) of the most abundant taxonomic groups (y-axis) across the dataset across all analysed aquifer lithologies (x-axis).

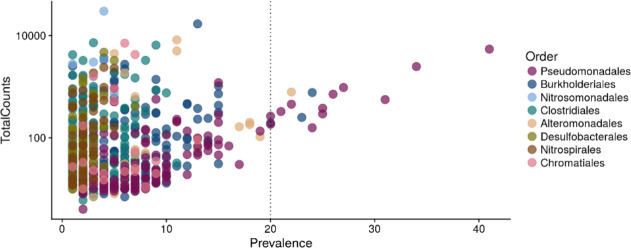

Analysis of prevalence across the dataset revealed that seven OTUs, all affiliated with the genus Pseudomonas , were present in more than 25 and up to 41 samples, accounting for 18 149 reads (3.5 % of the total reads, see Fig. 2, Table S3). Other bacterial orders, namely Burkholderiales , Alteromonadales and Clostridiales ( Betaproteobacteria , Gammaproteobacteria , Clostridia ) were also highly prevalent throughout. Network analysis (Table 2) highlighted a Pseudomonas OTU highly connected to other OTUs in the dataset. Furtherore, blast results indicated that recovered sequences for OTUs affiliated with this genus were generally associated with marine and terrestrial soil and sediments (see Fig. S3, Table S4) [59]. Four OTUs affiliated to Burkholderiales ( Betaproteobacteria ), the second most prevalent order in the dataset, were also found to be connected to up to 34 other OTUs. The genus Thauera (Betaproteobacteria, Rhodocyclales), represented by a single OTU, was the second most central to the dataset.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence (number of samples in which an OTU is present, x-axis) of OTUs across the dataset and associated reads (y-axis). Colours depict classification of OTUs at the order level. The vertical line is at 20 samples on the x-axis to highlight OTUs present in 20 or more samples.

Table 2.

Top 10 most central OTUs (Proteobacterial classes highlighted) in the Jaccard distances network (as defined by eigenvector centrality scores, or the scored value of the centrality of each connected neighbour of an OTU) and corresponding closeness centrality (scores of shortest paths to and from an OTU to all the remaining OTUs in a network) and degree (number of directly connected edges, or OTUs) values

|

OTU ID |

OTU classification |

Centrality |

Closeness |

Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EF554871.1.1486 |

Proteobacteria; Gammaproteobacteria ; Pseudomonadales; Pseudomonadaceae; Pseudomonas |

1.0000000 |

2.13e-05 |

38 |

|

HH792638.1.1492 |

Proteobacteria; Betaproteobacteria ; Rhodocyclales; Rhodocyclaceae; Thauera |

0.9753542 |

2.13e-05 |

36 |

|

HQ681977.1.1496 |

Proteobacteria; Betaproteobacteria ; Burkholderiales; Comamonadaceae; Diaphorobacter |

0.9445053 |

2.13e-05 |

34 |

|

KF465077.1.1336 |

Proteobacteria; Betaproteobacteria ; Burkholderiales; Comamonadaceae; Acidovorax |

0.8887751 |

2.13e-05 |

30 |

|

JQ072853.1.1348 |

Proteobacteria; Betaproteobacteria ; Rhodocyclales; Rhodocyclaceae; Thauera |

0.8808435 |

2.13e-05 |

30 |

|

KM200734.1.1449 |

Proteobacteria; Alphaproteobacteria ; Rhizobiales; Rhizobiaceae; Rhizobium |

0.8716886 |

2.13e-05 |

31 |

|

KC758926.1.1392 |

Proteobacteria; Betaproteobacteria ; Burkholderiales; Comamonadaceae; Acidovorax |

0.8662805 |

2.13e-05 |

29 |

|

FJ032194.1.1456 |

Proteobacteria; Betaproteobacteria ; Burkholderiales; Comamonadaceae; Rhodoferax |

0.8662805 |

2.13e-05 |

29 |

|

EU771645.1.1366 |

Firmicutes; Bacilli; Bacillales; Planococcaceae; Planomicrobium |

0.8476970 |

2.13e-05 |

30 |

|

JN245782.1.1433 |

Proteobacteria; Alphaproteobacteria .; Rhodobacterales; Rhodobacteraceae; Defluviimonas |

0.8356655 |

2.13e-05 |

29 |

While relative abundance patterns across the dataset (Fig. 1) indicate that lithology could influence microbial community composition and structure, sample sizes for each host-rock in the final dataset were insufficient to provide robust statistical support of that hypothesis. Despite this, host-rocks (10 out of 15) presented, on average, more unique OTUs than they shared with other host-rocks (Fig. S4). In particular, in sulphide-rich schists, 73 % of the OTUs were, on average, unique to the host-rock. Sub-bituminous and volatile bituminous coals shared a total of 143 OTUs; this was the strongest interaction between host-rocks in the dataset. No significant correlations were found for the presence of the most abundant clades in the dataset and depth, Actinobacteria being the only major taxonomic group to have a positive, albeit weak, correlation with depth (Pearson’s r=0.42, P<0.01, Fig. S5). Proportions of Beta- and Gammaproteobacteria generally decreased with depth (Pearson’s r=−0.29 and −0.093, respectively), but no other major clades were shown to correlate.

Ordination of the final dataset further suggests 50.6 % of Jensen–Shannon distances were significantly explained by aquifer lithology (ADONIS/PERMANOVA, F-statistic=4.65, P<0.001, adjusted Bonferroni correction P<0.001). Other environmental features such as absolute depth and medium-scale location (i.e. state, region of the sampling site) explained only 3.08 and 2.78 % of the significant metadata-driven variance in bacterial community structure, respectively (ADONIS/PERMANOVA, F-statistic=3.95, 3.57, P<0.001, adjusted Bonferroni correction P<0.001). Finally, no evidence was found for DNA extraction or 16S rRNA gene region significantly affecting bacterial community structure in this meta-analysis (ADONIS/PERMANOVA, F-statistic=3.85, 3.23, P<0.01, adjusted Bonferroni correction P<0.001).

Discussion

The deep biosphere is an active, diverse biome still largely under-investigated in terms of the Earth’s biogeochemistry [12, 60–62]. In this study, publicly available 16S rRNA gene data revealed a prevalence of Betaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria in the deep biosphere that may be explained by the diverse metabolic capabilities of taxa within these clades. The families Gallionellaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, Rhodocyclaceae and Hydrogeniphillaceae within Betaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria are suggested to play critical roles in deep subsurface iron, nitrogen, sulphur and carbon cycling across the world [50, 61, 63]. The relative abundance of the order Burkholderiales ( Betaproteobacteria ) in surficial soils has previously been correlated (R 2=0.92, ANOVA P<0.005) with mineral dissolution rates, while the genus Pseudomonas ( Gammaproteobacteria ) is widely known to play a key role in hydrocarbon degradation, denitrification and coal solubilization in different locations [64–66]. The dominance of Betaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria in coals builds on culture-based evidence of widespread degradation of coal-associated complex organic compounds by these classes [67–70].

The metabolic plasticity of the orders Pseudomonadales and Burkholderiales has been demonstrated and may be a catalyst for their apparent centrality across the terrestrial deep subsurface microbiomes analysed in this study [71–74]. These bacterial orders may represent important keystone taxa in microbial consortia responsible for providing critical substrates to other colonizers in deep subsurface environments [75, 76]. In particular, given the number of highly central Pseudomonas -affiliated OTUs and the prevalence of this genus in the dataset, we suggest that this genus may play a central role in establishing conditions for microbial colonization in many terrestrial subsurface environments. The genus Pseudomonas and possibly several members of Burkholderiales may therefore comprise an important component of the global core terrestrial deep subsurface bacterial community [11]. Geographically comprehensive RNA-based approaches should in the future investigate the potential roles of the genus Pseudomonas and order Burkholderiales in this biome.

The class Clostridia was found to be prevalent across the dataset and to dominate in sedimentary host-rocks (dolomite, siltstone and shale) in this study. This class includes anaerobic hydrogen-driven sulphate reducers also known to sporulate and metabolize a wide range of organic carbon compounds [77]. Previously, members of Clostridia have also been identified as dominant components in extremely deep subsurface ecosystems beneath South Africa, Siberia and California (USA) from metabasaltic and metasedimentary lithologies [78]. Adaptation to extreme environments in this class has been associated with diverse metabolic capabilities that include sporulation ability and capacity for CO2- or sulphur-based autotrophic H2-dependent growth [21, 79]. In this study, network analysis and prevalence values suggested roles of putative importance for the classes Betaproteobacteria , Gammaproteobacteria and Clostridia in the deep terrestrial subsurface (Fig. 2, Table S3). Their maintained presence in this biome across strikingly dissimilar host-rocks and depth, among others, could be indicative of higher metabolic plasticity, providing physiological advantages over other members of microbial communities.

Lithotrophic microbial metabolisms and mineralogy-driven microbial colonization of relatively inert lithologies have previously been demonstrated with low abundance but more reactive minerals within rock matrices often cited as key controls on community structure [80–83]. Limiting factors for life in the terrestrial deep subsurface such as pressure and temperature are more closely correlated with depth. Growth of bacterial isolates from the deep subsurface has been documented at up to 48 MPa and 50 °C and has been associated with production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) [84, 85]. However, robust conclusions on the effects of lithology or depth on the structure and composition of microbial communities across Earth’s crust have presented a widespread challenge for science, as in this study due to the small and varied sample sizes resulting from the contamination-aware filtering process and the limited number of comparable lithology types. Large-scale evidence for the roles of eukaryotes, bacteria, archaea and viruses in the deep terrestrial subsurface and the environmental controls over their occurrence in this biome is still lacking. We recommend a field-level research strategy to gain insights into these aspects of life within Earth’s crust. Larger scale collation of data from samples collected and processed using unified, reproducible workflows will be cognizant of significant potential for contamination and ultimately allow robust insights on wide-ranging microbial metabolic processes in the terrestrial subsurface.

Collecting contamination-free samples from the deep subsurface is difficult but important for cataloguing the authentic microbial diversity of the terrestrial subsurface. This study follows recent recommendations for downstream processing of contaminant-prone samples originated in the deep subsurface (Census of Deep Life project – https://deepcarbon.net/tag/census-deep-life), where physical, chemical and biological, but also in silico bioinformatics strategies to prevent erroneous conclusions have been highlighted [38, 86, 87]. This study also follows frequency-based OTU filtration techniques similar to those recommended previously [38] and designed to remove possible contaminants introduced during sampling or during the various steps related to sample processing [38]. The pre-emptive quality control steps hereby undertaken support a non-contaminant origin for the taxa analysed in this dataset. As such, the predominance of typically contaminant taxa affiliated, for example, to the genus Pseudomonas is accepted as a representative trend in reflecting the microbial ecology of the terrestrial deep subsurface.

Standardizing sampling, DNA extraction, sequencing and bioinformatics methods and strategies across the subsurface research community would help further reduce methodology-based variations. This would more efficiently permit re-analyses after collection, where methodological variations would be controlled, and robust wide-ranging overarching conclusions would more easily be achieved. Despite this, host-rock matrices and local geochemical conditions often pose unique challenges that require particular protocol adjustments [88]. In the near future, the advent of recently developed techniques for primer bias-free long read 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA-ITS gene amplicon long-read-based sequencing may initiate a convergence of molecular methods from which the deep subsurface microbiology community would benefit greatly [89, 90]. The future of large-scale, collaborative deep subsurface microbial diversity studies should encompass not only an effort towards standardization of several molecular biology techniques but also the long-term archival of samples [91]. Finally, the ecology of domains Eukarya and Archaea across the terrestrial deep subsurface remains generally under-characterized and requires future attention. This study presents an important first step towards characterizing bacterial community structure and composition in the terrestrial deep biosphere.

A global-scale meta-analysis addressing the available 16S rRNA gene-based studies of the deep terrestrial subsurface revealed a dominance of Betaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria and Firmicutes across this biome. Evidence for a core terrestrial deep subsurface microbiome population was recognized through the prevalence and centrality of the genus Pseudomonas ( Gammaproteobacteria ) and several other genera affiliated with the class Betaproteobacteria . The adaptable metabolic capabilities associated with the above-mentioned taxa may be critical for colonizing the deep subsurface and sustaining communities therein. The terrestrial deep subsurface is a hard-to-reach, complex ecosystem crucial to global biogeochemical cycles. Efforts by multiple teams of investigators to sequence subsurface ecosystems over the last decade were hereby consolidated to characterize the 12–20 % of global biomass this biome represents [5]. The strict contamination-aware filtering process applied whittled down the publicly available datasets representing terrestrial subsurface bacterial diversity to just 70 samples from two continents, indicating the need for systematic exploration of biodiversity within this major component of the biosphere. As a first step, this study consolidates a global-scale understanding of taxonomic trends underpinning a major component of terrestrial deep subsurface microbial ecology and biogeochemistry.

Supplementary Data

Funding information

The work was funded by a National Research Network for Low Carbon Energy and Environment (NRN-LCEE) grant to A.C.M. and A.E. from the Welsh Government and the Higher Education Funding Council for Wales (Geo-Carb-Cymru). Borehole samples from Nevada and California, USA (e.g. Nevares Deep Well 2 and BLM-1), were obtained with help in the field from Alexandra Wheatley, Jim Bruckner, Jenny Fisher and Scott Hamilton-Brehm, and technical assistance and funding from the US Department of Energy’s Subsurface Biogeochemical Research Program (SBR), the Hydrodynamic Group, LLC, the Nye County Nuclear Waste Repository Program Office (NWRPO), the US National Park Service, and Inyo Country, CA. Samples from a mine in Northern Ontario, Canada, were obtained with funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the assistance of Thomas Eckert, and Greg Slater of McMaster University. The Census of Deep Life (CoDL) and Deep Carbon Observatory (DCO) projects are acknowledged for a range of studies used in this analysis, as well as the sequencing team at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL). Disclaimer: Any use of trade, firm or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Author contributions

A.R.S. developed the methodology, collated and analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. A.E. and A.M. conceived the study, supervised A.S. and helped write the manuscript. Other authors provided data from field sites used in the global meta-analysis. All authors contributed, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; BIOM, biological observation matrix; CR, closed-reference; CTAB, hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide; EPS, extracellular polymeric substances; ITS, internal transcribed spacer; MPa, megapascal; OTU, operational taxonomic unit; OTU, operational taxonomic unit; PERMANOVA, permutational multivariate analysis of variance; PgC, petagrams of carbon; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; SRA-NCBI, sequence read archive database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Five supplementary figures and four supplementary tables are available with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Jelen BI, Giovannelli D, Falkowski PG. The role of microbial electron transfer in the coevolution of the biosphere and geosphere. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2016;70:45–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-102215-095521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falkowski PG, Fenchel T, Delong EF. The microbial engines that drive earths biogeochemical cycles. Science. 2008;320:1034–1039. doi: 10.1126/science.1153213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMahon S, Parnell J. The deep history of earth’s biomass. J Geol Soc London. 2018;175:716–720. doi: 10.1144/jgs2018-061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magnabosco C, Lin L-H, Dong H, Bomberg M, Ghiorse W, et al. The biomass and biodiversity of the continental subsurface. Nature Geosci. 2018;11:707–717. doi: 10.1038/s41561-018-0221-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bar-On YM, Phillips R, Milo R, Falkowski PG. The biomass distribution on Earth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:6506–6511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1711842115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flemming H-C, Wuertz S. Bacteria and archaea on Earth and their abundance in biofilms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:247–260. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith HJ, Zelaya AJ, De León KB, Chakraborty R, Elias DA, et al. Impact of hydrologic boundaries on microbial planktonic and biofilm communities in shallow terrestrial subsurface environments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2018;94 doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiy191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miettinen H, Kietäväinen R, Sohlberg E, Numminen M, Ahonen L, et al. Microbiome composition and geochemical characteristics of deep subsurface high-pressure environment, Pyhäsalmi mine Finland. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1–16. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagnoud A, Chourey K, Hettich RL, de Bruijn I, Andersson AF, et al. Reconstructing a hydrogen-driven microbial metabolic network in Opalinus Clay rock. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12770. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong Y, Kumar CG, Chia N, Kim P-J, Miller PA, et al. Halomonas sulfidaeris-dominated microbial community inhabits a 1.8 km-deep subsurface Cambrian Sandstone reservoir. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16:1695–1708. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purkamo L, Bomberg M, Kietäväinen R, Salavirta H, Nyyssönen M, et al. Microbial co-occurrence patterns in deep Precambrian bedrock fracture fluids. Biogeosciences. 2016;13:3091–3108. doi: 10.5194/bg-13-3091-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long PE, Williams KH, Hubbard SS, Banfield JF. Microbial metagenomics reveals climate-relevant subsurface biogeochemical processes. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:600–610. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anantharaman K, Brown CT, Hug LA, Sharon I, Castelle CJ, et al. Thousands of microbial genomes shed light on interconnected biogeochemical processes in an aquifer system. Nat Commun. 2016;7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hug LA, Thomas BC, Sharon I, Brown CT, Sharma R, et al. Critical biogeochemical functions in the subsurface are associated with bacteria from new phyla and little studied lineages. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:159–173. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Purkamo L, Kietäväinen R, Miettinen H, Sohlberg E, Kukkonen I, et al. Diversity and functionality of archaeal, bacterial and fungal communities in deep Archaean bedrock groundwater. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2018;94 doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiy116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker BJ, Moser DP, MacGregor BJ, Fishbain S, Wagner M, et al. Related assemblages of sulphate-reducing bacteria associated with ultradeep gold mines of South Africa and deep basalt aquifers of Washington State. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5:267–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chivian D, Brodie EL, Alm EJ, Culley DE, Dehal PS, et al. Environmental genomics reveals a single-species ecosystem deep within Earth. Science. 2008;322:275–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1155495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gihring TM, Moser DP, Lin L-H, Davidson M, Onstott TC, et al. The distribution of microbial taxa in the subsurface water of the Kalahari Shield, South Africa. Geomicrobiol J. 2007;23:415–430. doi: 10.1080/01490450600875696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moser DP, Gihring T, Fredrickson JK, Brockman FJ, Balkwill D. Desulfotomaculum spp. and Methanobacterium spp. dominate 4-5 km deep fault. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8773–8783. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8773-8783.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ueno A, Shimizu S, Tamamura S, Okuyama H, Naganuma T, et al. Anaerobic decomposition of humic substances by Clostridium from the deep subsurface. Sci Rep. 2016;6:2016. doi: 10.1038/srep18990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sousa DZ, Visser M, van Gelder AH, Boeren S, Pieterse MM, et al. The deep-subsurface sulfate reducer Desulfotomaculum kuznetsovii employs two methanol-degrading pathways. Nat Commun. 2018;9:239. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02518-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brazelton WJ, Morrill PL, Szponar N, Schrenk MO. Bacterial communities associated with subsurface geochemical processes in continental serpentinite springs. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:3906–3916. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00330-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nuppunen-Puputti M, Purkamo L, Kietäväinen R, Nyyssönen M, Itävaara M, et al. Rare biosphere archaea assimilate acetate in precambrian terrestrial subsurface at 2.2 km depth. Geosciences (Basel) 2018;8:418. doi: 10.3390/geosciences8110418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hubalek V, Wu X, Eiler A, Buck M, Heim C, et al. Connectivity to the surface determines diversity patterns in subsurface aquifers of the Fennoscandian shield. ISME J. 2016;10:2447–2458. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vieira-Silva S, Falony G, Darzi Y, Lima-Mendez G, Garcia Yunta R, et al. Species–function relationships shape ecological properties of the human gut microbiome. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16088. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emerson JB, Thomas BC, Alvarez W, Banfield JF. Metagenomic analysis of a high carbon dioxide subsurface microbial community populated by chemolithoautotrophs and bacteria and archaea from candidate phyla. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:1686–1703. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wouters K, Moors H, Boven P, Leys N. Evidence and characteristics of a diverse and metabolically active microbial community in deep subsurface clay borehole water. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2013;86:458–473. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unal B, Perry VR, Sheth M, Gomez-Alvarez V, Chin K-J, et al. Trace elements affect methanogenic activity and diversity in enrichments from subsurface coal bed produced water. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernsdorf AW, Amano Y, Miyakawa K, Ise K, Suzuki Y, et al. Potential for microbial H₂ and metal transformations associated with novel bacteria and archaea in deep terrestrial subsurface sediments. ISME J. 2017;11:1915–1929. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopez-Fernandez M, Broman E, Turner S, Wu X, Bertilsson S, et al. Investigation of viable taxa in the deep terrestrial biosphere suggests high rates of nutrient recycling. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2018;94 doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiy121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lloyd KG, Steen AD, Ladau J, Yin J, Crosby L. Phylogenetically novel uncultured microbial cells dominate Earth microbiomes. mSystems. 2018;3:e00055-18. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00055-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherwood Lollar B, Lacrampe-Couloume G, Slater GF, Ward J, Moser DP, et al. Unravelling abiogenic and biogenic sources of methane in the Earth’s deep subsurface. Chemical Geology. 2006;226:328–339. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2005.09.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin L-H, Wang P-L, Rumble D, Lippmann-Pipke J, Boice E, et al. Long-term sustainability of a high-energy, low-diversity crustal biome. Science. 2006;314:479–482. doi: 10.1126/science.1127376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li L, Wing BA, Bui TH, McDermott JM, Slater GF, et al. Sulfur mass-independent fractionation in subsurface fracture waters indicates a long-standing sulfur cycle in Precambrian rocks. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13252. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lollar GS, Warr O, Telling J, Osburn MR, Sherwood Lollar B. Follow the Water”: Hydrogeochemical Constraints on Microbial Investigations 2.4 km below surface at the Kidd Creek Deep Fluid and Deep Life Observatory. Geomicrobiology Journal;In review n.d. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilbert A, Sherwood Lollar B, Musat F, Giunta T, Chen S, et al. Intramolecular isotopic evidence for bacterial oxidation of propane in subsurface natural gas reservoirs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:6653–6658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1817784116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griffin WT, Phelps TJ, Colwell FS, Fredrickson JK. Microbiology of the Terrestrial Deep Subsurface. CRC Press; 2018. Methods for obtaining deep subsurface microbiological samples by drilling; pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheik CS, Reese BK, Twing KI, Sylvan JB, Grim SL, et al. Identification and removal of contaminant sequences from ribosomal gene databases: Lessons from the Census of Deep Life. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:840. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilkins MJ, Daly RA, Mouser PJ, Trexler R, Sharma S, et al. Trends and future challenges in sampling the deep terrestrial biosphere. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Penny SA, Dana LH. The Microbiology of the Terrestrial Deep Subsurface. CRC Press; 2018. pp. 75–102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russell BF, Phelps TJ, Griffin WT, Sargent KA. Procedures for sampling deep subsurface microbial communities in unconsolidated sediments. Groundwater Monitoring & Remediation. 1992;12:96–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6592.1992.tb00414.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. Phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wickham H, Chang W. ggplot2: An Implementation of the Grammar of Graphics

- 46.R Development Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing n.d.

- 47.Dixon P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J Veg Sci. 2003;14:927–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2003.tb02228.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fuglede B, Topsoe F. International Symposium OnInformation Theory, 2004. ISIT 2004. Proceedings. IEEE. Chicago, Illinois, USA: 2004. Jensen-Shannon divergence and Hilbert space embedding; p. 30. p. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frank YA, Kadnikov VV, Gavrilov SN, Banks D, Gerasimchuk AL, et al. Stable and variable parts of microbial community in Siberian deep subsurface thermal aquifer system revealed in a long-term monitoring study. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osburn MR, LaRowe DE, Momper LM, Amend JP. Chemolithotrophy in the continental deep subsurface: Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF) Front Microbiol. 2014;5:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barnhart EP, Weeks EP, Jones EJP, Ritter DJ, McIntosh JC, et al. Hydrogeochemistry and coal-associated bacterial populations from a methanogenic coal bed. International Journal of Coal Geology. 2016;162:14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.coal.2016.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lawson CE, Strachan CR, Williams DD, Koziel S, Hallam SJ, et al. Patterns of endemism and habitat selection in coalbed microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:7924–7937. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01737-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bomberg M, Lamminmäki T, Itävaara M. Microbial communities and their predicted metabolic characteristics in deep fracture groundwaters of the crystalline bedrock at Olkiluoto, Finland. Biogeosciences. 2016;13:6031–6047. doi: 10.5194/bg-13-6031-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andreou LV. Methods in Enzymology. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2013. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria; pp. 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foght J, Aislabie J, Turner S, Brown CE, Ryburn J, et al. Culturable bacteria in subglacial sediments and ice from two southern hemisphere glaciers. Microb Ecol. 2004;47:329–340. doi: 10.1007/s00248-003-1036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tillett D, Neilan BA. Xanthogenate nucleic acid isolation from cultured and environmental cyanobacteria. Journal of Phycology. 2001;36:251–258. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2000.99079.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leuko S, Goh F, Ibáñez-Peral R, Burns BP, Walter MR, et al. Lysis efficiency of standard DNA extraction methods for Halococcus spp. in an organic rich environment. Extremophiles. 2008;12:301–308. doi: 10.1007/s00792-007-0124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eisenhofer R, Minich JJ, Marotz C, Cooper A, Knight R, et al. Contamination in low microbial biomass microbiome studies: issues and recommendations. Trends Microbiol. 2019;27:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bomberg M, Nyyssönen M, Pitkänen P, Lehtinen A, Itävaara M. Active microbial communities inhabit sulphate-methane interphase in deep bedrock fracture fluids in Olkiluoto, Finland. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:979530. doi: 10.1155/2015/979530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rajala P, Bomberg M. Reactivation of deep subsurface microbial community in response to methane or methanol amendment. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:431. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lollar GS, Warr O, Telling J, Osburn MR, Lollar BS. Follow the water’: hydrogeochemical constraints on microbial investigations 2.4 km below surface at the kidd creek deep fluid and deep life observatory. Geomicrobiology Journal. 2019;36:859–872. doi: 10.1080/01490451.2019.1641770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blanco Y, Rivas LA, García-Moyano A, Aguirre J, Cruz-Gil P, et al. Deciphering the prokaryotic community and metabolisms in South African deep-mine biofilms through antibody microarrays and graph theory. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e114180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singh PK, Singh AL, Kumar A, Singh MP. Control of different pyrite forms on desulfurization of coal with bacteria. Fuel. 2013;106:876–879. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2012.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Machnikowska H, Pawelec K, Podgórska A. Microbial degradation of low rank coals. Fuel Processing Technology. 2002;77–78:17–23. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3820(02)00064-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lepleux C, Turpault MP, Oger P, Frey-Klett P, Uroz S. Correlation of the abundance of betaproteobacteria on mineral surfaces with mineral weathering in forest soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:7114–7119. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00996-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gründger F, Jiménez N, Thielemann T, Straaten N, Lüders T, et al. Microbial methane formation in deep aquifers of a coal-bearing sedimentary basin, Germany. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:200. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yagi JM, Sims D, Brettin T, Bruce D, Madsen EL. The genome of Polaromonas naphthalenivorans strain CJ2, isolated from coal tar-contaminated sediment, reveals physiological and metabolic versatility and evolution through extensive horizontal gene transfer. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:2253–2270. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kostka JE, Prakash O, Overholt WA, Green SJ, Freyer G, et al. Hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria and the bacterial community response in gulf of Mexico beach sands impacted by the deepwater horizon oil spill. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:7962–7974. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05402-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Posman KM, DeRito CM, Madsen EL. Benzene degradation by a variovorax species within a coal tar-contaminated groundwater microbial community. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83:e02658-16. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02658-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alhasawi A, Costanzi J, Auger C, Appanna ND, Appanna VD. Metabolic reconfigurations aimed at the detoxification of a multi-metal stress in Pseudomonas fluorescens: Implications for the bioremediation of metal pollutants. J Biotechnol. 2015;200:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Raiger Iustman LJ, Tribelli PM, Ibarra JG, Catone MV, Solar Venero EC, et al. Genome sequence analysis of Pseudomonas extremaustralis provides new insights into environmental adaptability and extreme conditions resistance. Extremophiles. 2015;19:207–220. doi: 10.1007/s00792-014-0700-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Uroz S, Calvaruso C, Turpault M-P, Frey-Klett P. Mineral weathering by bacteria: ecology, actors and mechanisms. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rosenberg E. The Prokaryotes: Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria. 2013. The family Comamonadaceae ; pp. 1–1012. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Onstott TC, Moser DP, Pfiffner SM, Fredrickson JK, Brockman FJ, et al. Indigenous and contaminant microbes in ultradeep mines. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5:1168–1191. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Davidson MM, Silver BJ, Onstott TC, Moser DP, Gihring TM, et al. Capture of planktonic microbial diversity in fractures by long-term monitoring of flowing boreholes, evander basin, South Africa. Geomicrobiology Journal. 2011;28:275–300. doi: 10.1080/01490451.2010.499928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dürre P. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015. Clostridia; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Moser DP, Gihring TM, Brockman FJ, Fredrickson JK, Balkwill DL, et al. Desulfotomaculum and Methanobacterium spp. dominate a 4- to 5-kilometer-deep fault. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8773–8783. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8773-8783.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Aüllo T, Ranchou-Peyruse A, Ollivier B, Magot M. Desulfotomaculum spp. and related gram-positive sulfate-reducing bacteria in deep subsurface environments. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mitchell AC, Lafrenière MJ, Skidmore ML, Boyd ES. Influence of bedrock mineral composition on microbial diversity in a subglacial environment. Geology. 2013;41:855–858. doi: 10.1130/G34194.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lapanje A, Wimmersberger C, Furrer G, Brunner I, Frey B. Pattern of elemental release during the granite dissolution can be changed by aerobic heterotrophic bacterial strains isolated from Damma Glacier (central Alps) deglaciated granite sand. Microb Ecol. 2012;63:865–882. doi: 10.1007/s00248-011-9976-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cockell CS, Voytek MA, Gronstal AL, Finster K, Kirshtein JD, et al. Impact disruption and recovery of the deep subsurface biosphere. Astrobiology. 2012;12:231–246. doi: 10.1089/ast.2011.0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Boyd ES, Cummings DE, Geesey GG. Mineralogy influences structure and diversity of bacterial communities associated with geological substrata in a pristine aquifer. Microb Ecol. 2007;54:170–182. doi: 10.1007/s00248-006-9187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fichtel K, Logemann J, Fichtel J, Rullkötter J, Cypionka H, et al. Temperature and pressure adaptation of a sulfate reducer from the deep subsurface. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1078. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Booker AE, Hoyt DW, Meulia T, Eder E, Nicora CD, et al. Deep-subsurface pressure stimulates metabolic plasticity in shale-colonizing Halanaerobium spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2019;85:e00018-19. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00018-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sogin M, Edwards K. DCO Deep Life Workshop. Catalina Island, California: 2010. Deep subsurface microbiology and the deep carbon observatory. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Davis NM, Proctor DM, Holmes SP, Relman DA, Callahan BJ. Simple statistical identification and removal of contaminant sequences in marker-gene and metagenomics data. Microbiome. 2018;6:226. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0605-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Direito SOL, Marees A, Röling WFM. Sensitive life detection strategies for low-biomass environments: Optimizing extraction of nucleic acids adsorbing to terrestrial and Mars analogue minerals. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012;81:111–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Karst SM, Dueholm MS, McIlroy SJ, Kirkegaard RH, Nielsen PH, et al. Retrieval of a million high-quality, full-length microbial 16S and 18S rRNA gene sequences without primer bias. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:190–195. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Martijn J, Lind AE, Spiers I, Juzokaite L, Bunikis I, et al. Amplicon sequencing of the 16S-ITS-23S rRNA operon with long-read technology for improved phylogenetic classification of uncultured prokaryotes. Microbiology. 2017 doi: 10.1101/234690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fierer N, Cary C. Don’t let microbial samples perish. Nature. 2014;512:253. doi: 10.1038/512253b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.