Key Points

Question

Can DNA sequencing of blood from adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in first remission prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant identify patients at increased risk of subsequent relapse and death?

Findings

In patients with AML in first complete remission who received a transplant from March 1, 2013, through December 31, 2017 (discovery, n = 371) or from January 1, 2018, through February 14, 2019 (validation, n = 451), the presence of residual FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) and/or NPM1 DNA variants before transplant were associated with significantly increased rates of relapse (validation cohort difference, 47%; 95% CI, 26% to 69%) and significantly worse survival (validation cohort difference, −24%; 95% CI, −39 to −9%) at 3 years, compared with those without these markers.

Meaning

Among patients with AML in first remission prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant, the persistence of FLT3-ITD or NPM1 variants in the blood at an allele fraction of 0.01% or higher was associated with increased relapse and worse survival compared with those without variants detected.

Abstract

Importance

Preventing relapse for adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in first remission is the most common indication for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant. The presence of AML measurable residual disease (MRD) has been associated with higher relapse rates, but testing is not standardized.

Objective

To determine whether DNA sequencing to identify residual variants in the blood of adults with AML in first remission before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant identifies patients at increased risk of relapse and poorer overall survival compared with those without these DNA variants.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this retrospective observational study, DNA sequencing was performed on pretransplant blood from patients aged 18 years or older who had undergone their first allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant during first remission for AML associated with variants in FLT3, NPM1, IDH1, IDH2, or KIT at 1 of 111 treatment sites from 2013 through 2019. Clinical data were collected, through May 2022, by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research.

Exposure

Centralized DNA sequencing of banked pretransplant remission blood samples.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcomes were overall survival and relapse. Day of transplant was considered day 0. Hazard ratios were reported using Cox proportional hazards regression models.

Results

Of 1075 patients tested, 822 had FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) and/or NPM1 mutated AML (median age, 57.1 years, 54% female). Among 371 patients in the discovery cohort, the persistence of NPM1 and/or FLT3-ITD variants in the blood of 64 patients (17.3%) in remission before undergoing transplant was associated with worse outcomes after transplant (2013-2017). Similarly, of the 451 patients in the validation cohort who had undergone transplant in 2018-2019, 78 patients (17.3%) with residual NPM1 and/or FLT3-ITD variants had higher rates of relapse at 3 years (68% vs 21%; difference, 47% [95% CI, 26% to 69%]; HR, 4.32 [95% CI, 2.98 to 6.26]; P < .001) and decreased survival at 3 years (39% vs 63%; difference, −24% [2-sided 95% CI, −39% to −9%]; HR, 2.43 [95% CI, 1.71 to 3.45]; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first remission prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant, the persistence of FLT3 internal tandem duplication or NPM1 variants in the blood at an allele fraction of 0.01% or higher was associated with increased relapse and worse survival compared with those without these variants. Further study is needed to determine whether routine DNA-sequencing testing for residual variants can improve outcomes for patients with acute myeloid leukemia.

In this observational study, targeted deep DNA sequencing was performed to test the hypothesis that detection of specific residual AML-associated variants in the blood of patients in first remission prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant would be associated with higher rates of relapse and mortality after transplant

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a rare group of blood cancers associated with a high mortality rate.1 The genetic etiology of AML has been well characterized,2,3,4,5 and genomic analysis performed at the time of AML diagnosis can help predict response to therapy,6,7,8 determine patients eligible for specific molecularly targeted therapies,9,10,11,12 and identify patients at highest risk of subsequent relapse and death among those who achieve an initial complete remission to therapy.3,13,14

Maintenance of initial remission for patients with AML is the most common indication for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant and is generally recommended as consolidative therapy during first remission for all except those unable, unwilling, or those with the lowest expected rates of relapse after chemotherapy.14,15,16,17 Despite this, disease recurrence after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant occurs in approximately 30% of patients and is the most common cause of posttransplant death.

Growing evidence suggests that results of measurable residual disease (MRD) testing provides important information regarding risk for subsequent relapse and mortality in patients in cytomorphological complete remission, including prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant.18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 However, there is currently no standard method for AML MRD testing.18 Flow cytometry is commonly used for AML MRD testing, particularly when no appropriate molecular method is available,18 but concerns have been raised about lack of interlaboratory standardization, leading to potentially limited prognostic value in decentralized settings.26,27,28 The evidence for novel approaches such as genetic sequencing to identify patients in clinical remission at higher risk of relapse or mortality29,30,31,32,33,34,35 has been insufficient for widespread clinical adoption.

In this Pre-MEASURE observational study, targeted deep DNA sequencing was performed to test the hypothesis that detection of specific residual AML-associated variants in the blood of patients in first remission prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant would be associated with higher rates of relapse and mortality after transplant. Secondary outcomes were relapse-free survival and nonrelapse mortality.

Methods

Clinical Cohort

The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR)—a research collaboration between the National Marrow Donor Program, the Medical College of Wisconsin, and more than 330 transplant centers—collects detailed patient-, disease-, and treatment-related data for every patient undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant in the US. Participating centers were required to report all treatments consecutively. Compliance was monitored by clinical research coordinators, and patients were followed up longitudinally. Computerized checks and physicians’ review of submitted data and on-site audits of participating centers were used to monitor data quality. Protected health information for research was collected and maintained in CIBMTR’s capacity as a public health authority under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy rule. Eligible patients for this study were aged 18 years or older; had undergone their first allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant during first complete remission for AML associated with variants in NPM1 (OMIM 164040), FLT3 (OMIM 136351), IDH1 (OMIM 147700), IDH2 (OMIM 147650), and/or KIT (OMIM 164920); had a remission blood sample collected within 100 days prior to transplant; and had undergone transplant at least 3 years before the study analysis with relapse and survival data available. Race and ethnicity data were collected by CIBMTR as pretransplant essential data and were based on patient self-report extracted from the medical record by transplant center data managers in categories based on the US Office of Management and Budget’s Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. CIBMTR requires reporting sites to report if flow cytometry testing was performed during remission at the time of transplant, and if any evidence of residual AML was detected. All patients provided written informed consent for participation in the National Marrow Donor Program institutional review board–approved CIBMTR database (NCT01166009) and repository (NCT04920474) research protocols. Research was performed in compliance with all applicable federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants and with the approval of the CIBMTR observational research group. In this study, patients were not randomly assigned to conditioning intensities, and treating physicians were aware of pretransplant patient and disease factors.

Next-Generation Sequencing for Residual Variant Detection

Targeted error–corrected DNA sequencing was performed on 500 ng of genomic DNA using a custom panel covering hotspot regions within the 5 genes of interest. Libraries were generated using an automated liquid handling workflow with pre–polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and post-PCR separation and subjected to sequencing using unique dual indexes on a NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina). A variant allele fraction of 0.01% or higher was used to classify positive from negative MRD results. Further details on library preparation and variant detection are available in Supplement 1.

Statistical Analysis

Clinical data of the patients included age, sex, race and ethnicity, hematopoietic cell transplant–specific comorbidity index, Karnofsky performance status, de novo or secondary (history of antecedent hematological disorder or prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy) AML type, European LeukemiaNet 2017 risk group,36,37 baseline genetics before transplant (IDH1, IDH2, KIT, NPM1, FLT3-tyrosine kinase domain [FLT3-TKD], and FLT3 internal tandem duplication [FLT3-ITD]), conditioning regimen, graft type, donor group, antithymocyte globulin usage, and site reported MRD status. The day of the transplant was considered day 0. The primary outcomes were overall survival and cumulative incidence of relapse with nonrelapse mortality as a competing risk. Relapse-free survival and nonrelapse mortality were secondary outcomes. Kaplan-Meier estimation and log-rank tests were used to calculate overall survival and relapse-free survival end points. Fine-Gray models were used to examine cumulative incidence of relapse with nonrelapse mortality as a competing risk. Gene combinations for next-generation sequencing (NGS) MRD were determined by the discovery cohort and validated in the validation cohort. Cox proportional hazards regression models with forward selection or Lasso penalty were used to estimate the relative risks of clinical events, and the proportional hazards assumptions were evaluated using Schoenfeld residuals. Flow cytometry, AML variant subtype, and transplant intensity subgroup analyses were performed in the combined discovery and validation cohorts of patients with NPM1 mutated and/or FLT3-ITD AML. Interaction testing was performed using a likelihood ratio test. All tests were 2-sided, and the statistical significance threshold was set as P < .05. The prespecified statistical analysis plan was registered with Open Science Framework. R version 4.2.0 was used for analysis and figure generation. Further details are provided in Supplement 1.

Results

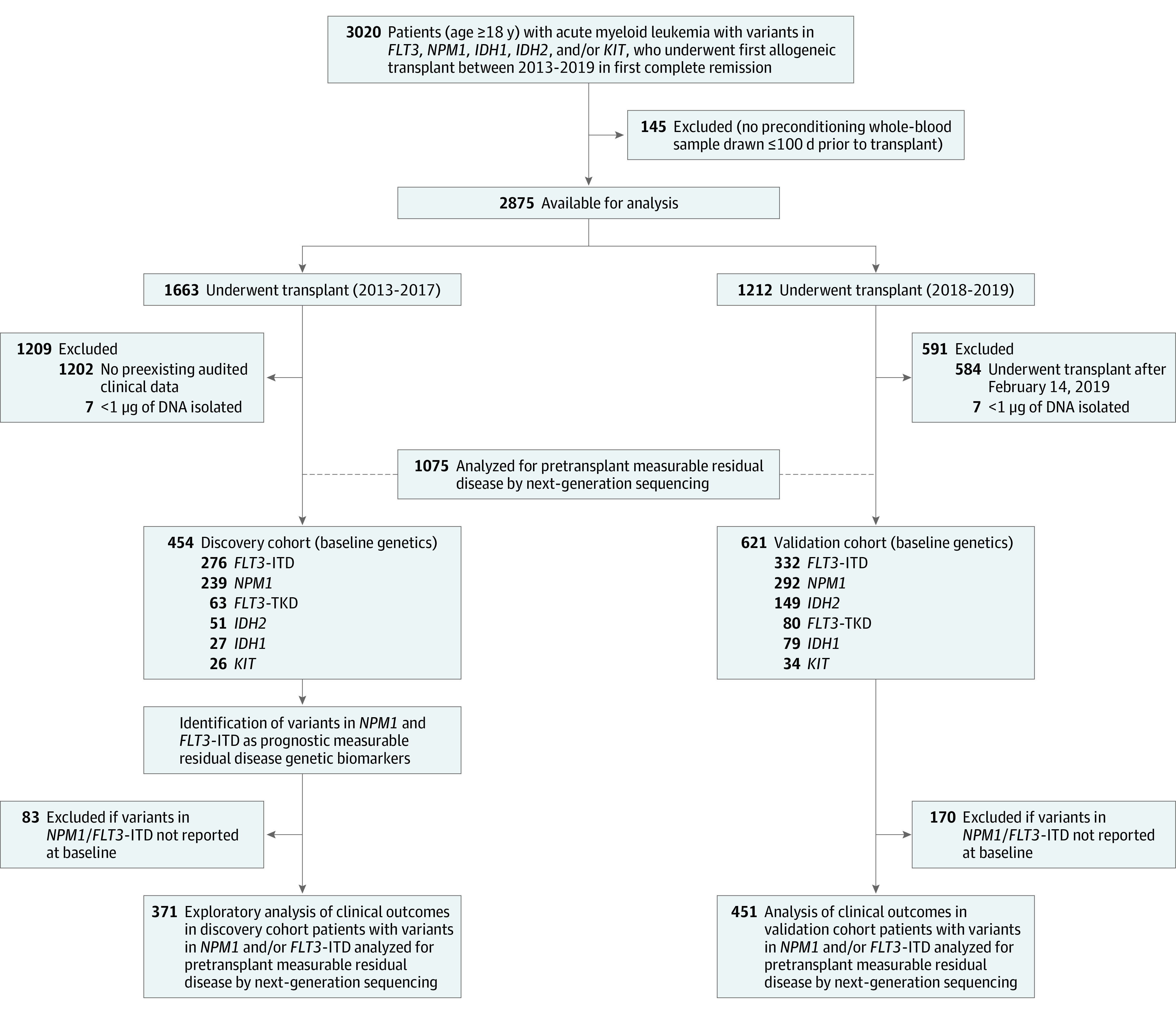

Between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2019, a total of 3020 patients aged 18 years or older in first complete remission from AML associated with FLT3, NPM1, IDH1, IDH2, and/or KIT variants received a first allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant at a CIBMTR reporting site and had consented for research. After exclusions (based on sample and data availability, length of follow-up time since transplant, and unsuccessful DNA extraction from blood), 1075 patients were available for analysis (from 110 sites in the US and 1 in Europe), including 454 who had undergone transplant between March 1, 2013, and December 31, 2017 (discovery cohort), and 621 in the validation cohort who had undergone transplant between January 1, 2018, and February 14, 2019 (Figure 1, Table, and eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). The 2 cohorts were similar for most patient, leukemic, and transplant factors. However, among patients in the validation cohort, variants in the IDH genes at AML diagnosis were more commonly reported and cord blood transplants were less commonly received. Eighty-four percent of patients in these cohorts were White.38

Figure 1. Patient Selection for the Pre-MEASURE Study.

ITD indicates internal tandem duplication; TKD, tyrosine kinase domain.

Table. Patient Clinical Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery (2013-2017) | Validation (2018-2019) | |

| No. of patients | 454 | 621 |

| Sites | 81 | 101 |

| Age, y | ||

| Median (range) | 56.8 (18.4-75.6) | 58.2 (18-80.5) |

| <60 | 275 (61) | 346 (56) |

| ≥60 | 179 (39) | 275 (44) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 237 (52) | 331 (53) |

| Male | 217 (48) | 290 (47) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| No. | 443 | 603 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (<1) | 3 (<1) |

| Asian | 32 (7) | 31 (5) |

| Black or African American | 32 (7) | 30 (5) |

| Multiracial | 2 (<1) | 2 (<1) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 (<1) | 3 (<1) |

| White (Hispanic or Latino) | 18 (4) | 34 (6) |

| White (non-Hispanic, non-Latino) | 356 (80) | 500 (83) |

| HCT-comorbidity indexa | ||

| No. | 444 | 617 |

| 0 (lowest comorbidity) | 75 (17) | 132 (21) |

| 1-2 (intermediate comorbidity) | 160 (36) | 175 (28) |

| >2 (highest comorbidity) | 209 (47) | 310 (50) |

| Karnofsky performance scoreb | ||

| No. | 449 | |

| <90 (less able to carry out daily activities) | 186 (41) | 249 (40) |

| ≥90 (normal activity without extra effort) | 263 (59) | 372 (60) |

| AML type | ||

| De novo | 390 (86) | 556 (90) |

| Secondary | ||

| Therapy-related | 17 (4) | 31 (5) |

| Transformed MDS/MPN | 47 (10) | 34 (6) |

| ELN risk groupc | ||

| Favorable | 86 (19) | 155 (25) |

| Intermediate | 220 (49) | 255 (41) |

| Adverse | 146 (32) | 211 (34) |

| Reported variants from AML diagnosis | ||

| FLT3-TKD | 63 | 80 |

| FLT3-ITD | 276 | 332 |

| IDH1 | 27 | 79 |

| IDH2 | 51 | 149 |

| KIT | 26 | 34 |

| NPM1 | 239 | 292 |

| Baseline FLT3-ITD and NPM1 co-occurrence | ||

| FLT3-ITD plus NPM1 mutated | 144 | 173 |

| FLT3-ITD plus NPM1 wild type | 98 | 128 |

| FLT3-ITD plus unknown | 34 | 31 |

| Conditioning regimen | ||

| Myeloablative | 254 (56) | 351 (57) |

| Reduced intensity/nonmyeloablative | 200 (44) | 270 (43) |

| Graft typed | ||

| Peripheral blood | 287 (63) | 490 (79) |

| Bone marrow | 64 (14) | 96 (15) |

| Cord blood | 103 (23) | 35 (6) |

| Donor type | ||

| Matched unrelated | 231 (51) | 404 (65) |

| Cord blood | 103 (23) | 32 (5) |

| HLA-identical sibling | 68 (15) | 69 (11) |

| Haploidentical related | 44 (10) | 55 (9) |

| Mismatched | 8 (2) | 61 (10) |

| Antithymocyte globulin used | 123/451 (27) | 142/621 (23) |

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ELN, European LeukemiaNet; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; ITD, internal tandem duplication; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm; TKD, tyrosine kinase domain.

The HCT comorbidity index stratifies patients based on the number and severity of pretransplant comorbidities to predict nonrelapse mortality and survival.50

The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research uses Karnofsky performance status to determine the functional status of transplant recipients aged 16 or older.

Standardized prognostic system distinguishes distinct risk groups of patients with newly diagnosed AML.36,37

Three recipients in the validation cohort listed as graft type cord blood received haploidentical and cord blood transplants.

No differences in 3-year relapse rates (29% vs 28%) or overall survival rates (61% vs 61%) were observed between the discovery and validation cohorts. Patients with secondary AML, European LeukemiaNet adverse or intermediate risk, or who had received reduced-intensity conditioning had higher relapse rates. Age, sex, race and ethnicity, patient comorbidity (hematopoietic cell transplant–specific comorbidity) or performance (Karnofsky performance status) scores, graft source, donor type, and antithymocyte globulin usage were not associated with relapse rates (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1).

Blood was collected a median of 9 days prior to transplant. In the discovery cohort, 131 of 454 patients (28.9%) had a variant in the FLT3, NPM1, IDH1, IDH2, or KIT genes detected in pretransplant remission blood by NGS-MRD. The total number of variants in the discovery cohort was 177. The most common variants detected were in FLT3-ITD, IDH2, and NPM1. In the validation cohort, 188 of 621 patients (30.3%) had a variant in FLT3, NPM1, IDH1, IDH2, or KIT detected by NGS-MRD. The total number of variants detected in this validation cohort was 254. The most common variants detected were in IDH2, FLT3-ITD, and NPM1. Detected variants were validated using digital droplet PCR (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1).

In the discovery cohort, detection of variants in pre–allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant remission blood was associated with increased relapse, lower relapse-free survival, and decreased overall survival and was not associated with nonrelapse mortality (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1). Univariate Cox regression analysis identified detection of FLT3-ITD or NPM1 variants as associated with increased relapse in this cohort and was selected as the NGS-MRD definition (eFigure 5 in Supplement 1). The 822 patients in the discovery and validation cohorts reported to have NPM1 and/or FLT3-ITD variants present at their initial AML diagnosis served as the focus for analysis on the association of detecting persistence of these variants in remission (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

Primary Outcomes

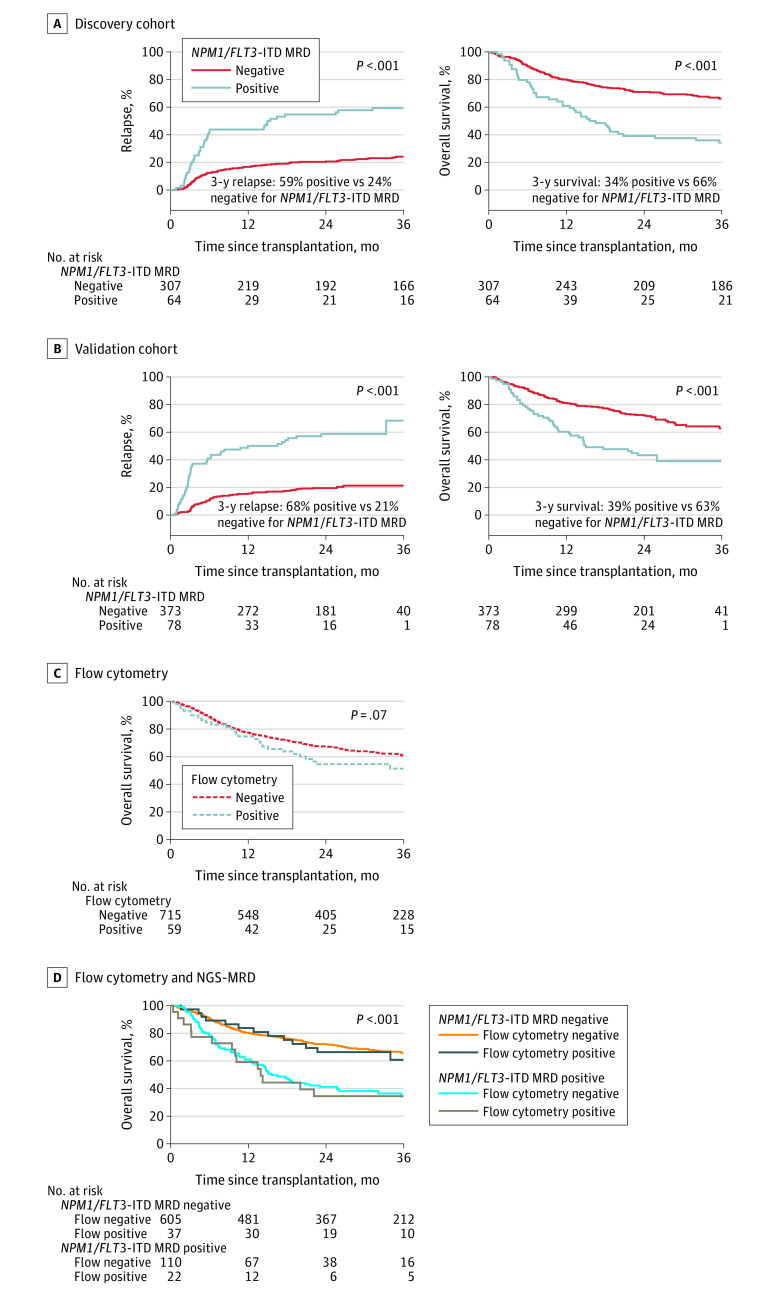

In the discovery cohort of 371 patients with NPM1 mutated and/or FLT3-ITD AML, 64 patients (17.3%) with persistent NPM1 and/or FLT3-ITD variants detected in pretransplant remission blood had significantly higher posttransplant relapse (at 3 years, 59% vs 24%; difference, 35% [2-sided 95% CI, 22% to 48%]; HR, 3.71 [95% CI, 2.55 to 5.41]; P < .001) and lower overall survival (at 3 years, 34% vs 66% difference, −32% [2-sided 95% CI, −45% to −19%]; HR, 2.60 [95% CI, 1.85 to 3.65]; P < .001) than those without persistent variants (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Impact of NPM1 and FLT3 Internal Tandem Duplication Next-Generation Sequencing–Measurable Residual Disease Status on Clinical Outcomes.

Patients with NPM1 mutated and/or FLT3 internal tandem duplication (NPM1/FLT3-ITD) acute myeloid leukemia (n = 822) with measurable residual disease (MRD) defined by persistent variants detectable by next-generation sequencing (NGS) in remission blood prior to transplant (NPM1/FLT3-ITD MRD positive) had significantly higher rates of relapse and decreased overall survival after transplant than patients with no variants detected (NPM1/FLT3-ITD MRD negative).

A, The median time of observation was 61 months (IQR, 48-64 months) for patients who tested positive for MRD and 60 months (IQR, 48-72 months) for patients who tested negative for MRD in the discovery cohort.

B, The median time of observation was 24 months (IQR, 24-26 months) for patients who tested positive for MRD and 25 months (IQR, 24-28 months) for patients who tested negative for MRD in the validation cohort.

C and D, Results of flow cytometry performed in remission prior to transplant do not stratify for overall survival in this cohort (panel C) and do not add additional prognostic value to the results of DNA sequencing (panel D). The median time of observation was 26 months (IQR, 24-47 months) for patients who tested positive for MRD by flow cytometry and 35 months (IQR, 24-57 months) for patients who tested negative. The median time of observation was 36 months (IQR, 24-59 months) for patients who tested negative by NGS-MRD and flow cytometry, 26 months (IQR, 24-46 months) for patients who tested positive by NGS-MRD and flow cytometry, 37 months (IQR, 24-61 months) for those who tested positive by NGS-MRD and flow cytometry, and 25 months (IQR, 24-45 months) for patients who tested negative.

In the validation cohort of 451 patients with NPM1 mutated and/or FLT3-ITD AML, detection of persistent NPM1 and/or FLT3-ITD variants among 78 (17.3%) was associated with a significantly higher posttransplant relapse rate (at 3 years, 68% vs 21%; difference, 47% [2-sided 95% CI, 26% to 69%]; HR, 4.32 [95% CI, 2.98 to 6.26]; P < .001) and lower overall survival (at 3 years, 39% vs 63%; difference, −24% [2-sided 95% CI, −39% to −9%]; HR, 2.43 [95% CI, 1.71 to 3.45]; P < .001) than those without persistent variants (Figure 2B). The proportional hazards assumption was not violated.

Secondary Outcomes

Detection of persistent FLT3-ITD and/or NPM1 variants was associated with lower rates of relapse-free survival at 3 years compared with testing negative in both the discovery (27% vs 59%) and validation (19% vs 59%) cohorts (eFigure 6 in Supplement 1). Patients who tested positive for residual FLT3-ITD and/or NPM1 variants in the discovery and validation cohorts had nonrelapse mortality rates similar to those testing negative (eFigure 6 in Supplement 1).

Flow cytometry is currently commonly performed as a test for measurable residual disease in patients with AML in remission prior to transplant. Ninety-four percent (774 of 822) of patients in the combined discovery and validation cohorts were reported to have undergone such testing. The 59 patients (7.6%) testing positive for residual disease by flow cytometry prior to transplant had overall survival rates that did not statistically differ from those testing negative (P = .07), represented only 16.7% (22 of 132) of those testing positive by DNA-sequencing for persistent variants, and added no additional prognostic information regarding overall survival to that provided by DNA-sequencing (Figure 2C and D).

NGS-MRD in Molecular Subgroups

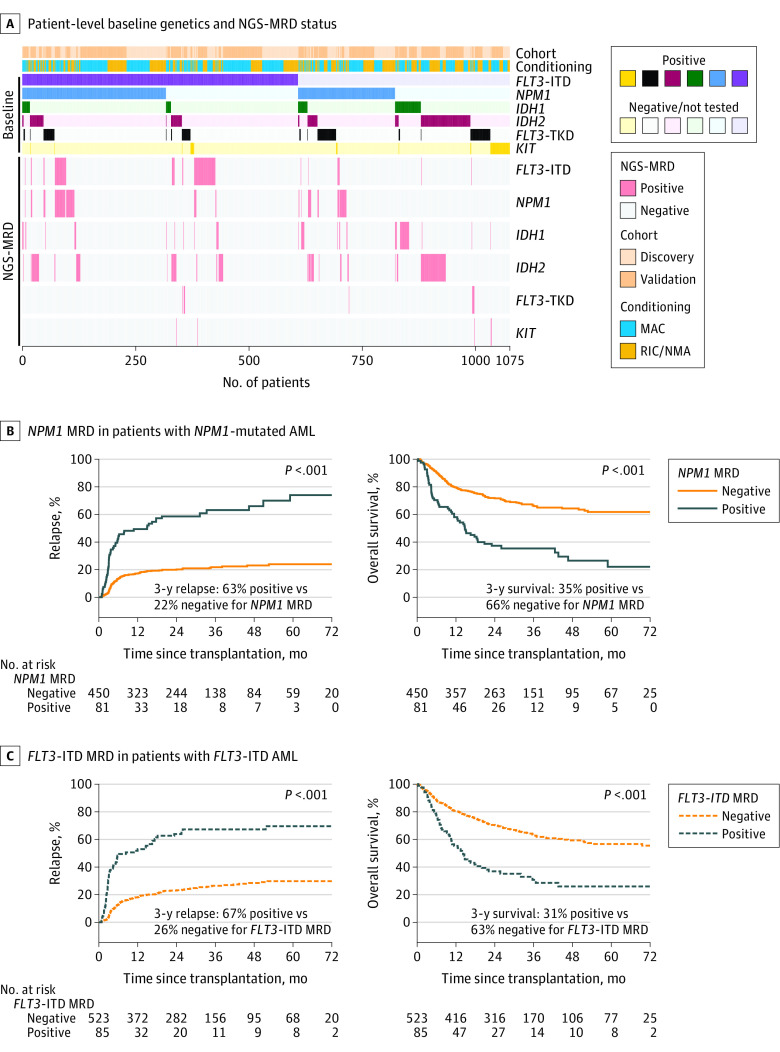

Four hundred eighty (45%) of screened patients in this study were reported as having variants in multiple genes of interest at the time of initial AML diagnosis (median, 1; range, 1-4; Figure 3).

Figure 3. Detection and Impact of Residual Variants on Clinical Outcomes by Gene.

A, Heatmap illustrating for each patient (n = 1075) their cohort assignment, conditioning intensity, reported baseline variant status, and residual variant detection status by next-generation sequencing measurable residual disease (NGS-MRD) for each gene. Patients are sorted by the variants reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research as being present at initial (baseline) diagnosis (positive or negative/not tested).

B, Patients with NPM1 mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (n = 531) with residual NPM1 variants detectable by NGS prior to transplant (NPM1 MRD positive) had significantly higher rates of relapse and decreased overall survival than patients with no NPM1 variants detected (NPM1 MRD negative). The median time of observation was 29 months (IQR, 24-48 months) for patients who tested positive and 34 months (IQR, 24-50 months) for those who tested negative.

C, Patients with FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) AML (n = 608) with residual FLT3-ITD variants detectable by NGS prior to transplant (FLT3-ITD MRD positive) had significantly higher rates of relapse and decreased overall survival than patients with no FLT3-ITD detected (FLT3-ITD MRD negative). The median time of observation was 28 months (IQR, 24-61 months) in patients who tested positive and 35 months (IQR, 24-52 months) for those who tested negative.

MAC indicates myeloablative conditioning, NMA, nonmyeloablative conditioning; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning; TKD, tyrosine kinase domain.

The 3-year relapse rate for all 531 patients with NPM1-mutated AML was 28%. Residual NPM1 variants in pretransplant remission blood samples were detectable in 81 (15.3%) of these patients and associated with statistically significantly higher rates of relapse compared with those without residual NPM1 variants detected (at 3 years, 63% vs 22%; HR, 4.45 [95% CI, 3.17-6.25]; P < .001), as well as with significantly lower rates of relapse-free survival (at 3 years, 23% vs 61%; HR, 3.16 [95% CI, 2.36- 4.23]; P < .001) and overall survival (at 3 years, 35% vs 66%; HR, 2.87 [95% CI, 2.10-3.92]; P < .001).

The 3-year relapse rate for all 608 patients with FLT3-ITD AML was 32%. Residual FLT3-ITD was detectable in pretransplant remission blood samples from 85 (14%) of these patients and associated with significantly higher rates of relapse vs those without residual FLT3-ITD detected (at 3 years, 67% vs 26%; HR, 4.09 [95% CI, 3.00-5.58]; P < .001), as well as with significantly lower rates of relapse-free survival (at 3 years, 20% vs 56%; HR, 2.91 [95% CI, 2.21-3.83]; P < .001) and overall survival (at 3 years, 31% vs 63%; HR, 2.59 [95% CI, 1.93-3.48]; P < .001).

Results of DNA sequencing for residual FLT3-ITD and NPM1 variants in remission blood, but not site-reported flow cytometry testing, was associated with statistically significant stratification for posttransplant overall survival in all molecular subgroups (eFigure 7 in Supplement 1). DNA sequencing for residual FLT3-ITD and NPM1 variants in remission blood was also associated with statistically significant stratification in both younger and older adults (eFigure 8 in Supplement 1). No racial differences were detected in clinical outcomes (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1), NGS-MRD rates, or prognosis (eFigure 8 in Supplement 1).

For those patients with AML containing variants in both NPM1 and FLT3-ITD, detection in pretransplant remission blood of NPM1 variants alone, FLT3-ITD alone, or both was associated with increased posttransplant relapse (eFigure 9 in Supplement 1).

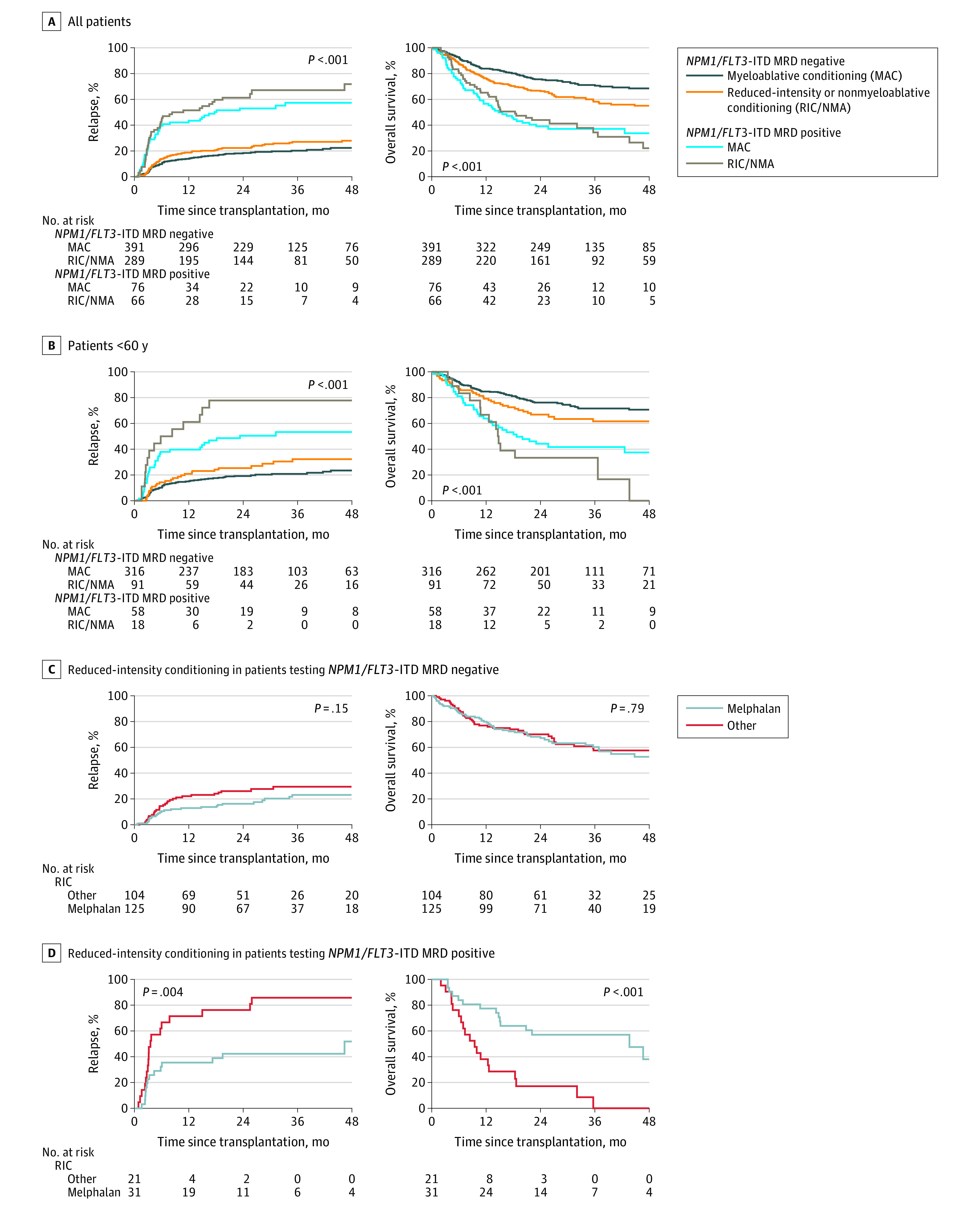

Results According to Transplant Intensity

An important component of the allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant procedure is the preparative chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy conditioning regimen given, immediately before infusion of donor hematopoietic cells, with the dual intent of facilitating donor cell engraftment and reducing residual tumor burden.39 There is strong evidence that patients who test positive for MRD prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant with reduced-intensity conditioning have high relapse and poor survival40 and that in younger adult patients, conditioning intensification may improve these outcomes.24,41 NGS-MRD positivity was associated with higher rates of relapse and worse survival (Figure 4A) partially mitigated (likelihood ratio test P = .02) in younger patients (<60 years) who received high-intensity myeloablative conditioning (3-year relapse rate, 53% vs 78%; HR, 1.97 [95% CI, 1.03-3.75]; P = .04; Figure 4B and eFigure 10 in Supplement 1).

Figure 4. Impact of Conditioning Intensity and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Measurable Residual Disease Status on Clinical Outcomes.

A, Among patients with NPM1 mutated and/or FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) acute myeloid leukemia (AML; n = 822), differences in relapse rates and overall survival were identified between subgroups defined by conditioning intensity and NGS-based measurable residual disease (MRD) status.

B, In patients with NPM1 mutated and/or FLT3-ITD AML younger than 60 years (n = 483), MAC regimens resulted in significantly decreased rates of relapse (P = .04) in the MRD-positive group.

C and D, In patients with NPM1 mutated and/or FLT3-ITD AML receiving RIC (n = 281), melphalan conditioning was associated with significantly decreased relapse rates and increased overall survival in the MRD-positive group but not in the MRD-negative group. Median times of observation are listed in eTable 3.

Based on the premise that patients who underwent reduced-intensity transplants would be more similar to each other than to those receiving myeloablative conditioning in this nonrandomized study, exploratory analyses were performed comparing outcomes in patients receiving melphalan-containing reduced-intensity regimens with other forms of reduced-intensity conditioning (excluding nonmyeloablative regimens, eTable 2 in Supplement 1). There was no statistically significant difference in relapse or survival in those who were NGS-MRD negative, but significantly lower relapse and improved survival in patients positive for NGS-MRD receiving melphalan-based reduced-intensity conditioning (Figure 4C and D).

In multivariable analyses, NGS-MRD status was associated with both relapse and overall survival although receipt of reduced-intensity conditioning that did not contain melphalan was also associated with a higher rate of relapse (eFigure 11 in Supplement 1). In subgroups defined by baseline FLT3-ITD and NPM1 variant status, NGS-MRD remained significant regardless of variant allele fraction threshold selected. FLT3-ITD or NPM1 variants detected in remission using the current European LeukemiaNet recommended threshold of 0.1% variant allele fraction was associated with increased rates of relapse and decreased survival, lowering this threshold 10-fold to 0.01% variant allele fraction did not substantially change these findings but doubled the number of patients identified as NGS-MRD positive (eFigure 11 in Supplement 1). No difference in rates of NGS-MRD positivity were observed between the initial discovery cohort and the later validation cohort that followed the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the FLT3 inhibitor midostaurin for AML in 2017.42 No difference in clinical outcomes was observed for those receiving posttransplant maintenance therapy, regardless of NGS-MRD status (eFigure 12 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

Results reported herein demonstrated that the detection by DNA-sequencing of persistent FLT3-ITD or NPM1 variants in the blood of adult patients with AML in remission before transplant was associated with statistically significant increased rates of relapse and decreased survival than those testing negative. FLT3-ITD and NPM1 are the most common variants in AML.3,4 Although prognostic models based on baseline characteristics can be developed to stratify entire cohorts of patients based on relapse or survival probabilities, these results show that NGS-MRD testing of the blood of patients with FLT3-ITD and/or NPM1 mutated AML in first remission prior to transplant could identify differential risk between individuals otherwise placed in the same baseline risk classification.

A personalized medicine approach to the care of patients with AML would require not only comprehensive clinical and genetic profiling at initial diagnosis for an optimal initial therapeutic approach but also iterative reassessment and therapy adjustment during and after planned treatment. The ability to detect residual leukemia in patients in an apparent complete remission after treatment using AML MRD would be an important clinical tool, if the measured result were interpretable in the context of large clinical data sets supporting both the prognostic implications and the potential clinical utility of any proposed therapeutic intervention.

Consistent with prior reports,24,41 myeloablative conditioning was associated with less relapse and improved survival, compared with reduced-intensity conditioning in younger patients with NGS-MRD prior to transplant (Figure 4B). However, many patients with AML are not able to tolerate myeloablative conditioning, limiting applicability. Attempts to augment reduced-intensity conditioning to reduce the risk of relapse, particularly among those testing MRD positive, have been unsuccessful.40 Large registry-level retrospective analyses reported that melphalan-containing reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant regimens for AML were associated with lower relapse rates than busulfan-based regimens.43,44 Results reported herein did not find evidence of a difference in relapse for patients testing NGS-MRD negative prior to reduced-intensity transplants when comparing those who received a transplant with or without melphalan. In contrast, there was a statistically significant difference in relapse and survival for those with persistently detectable FLT3-ITD or NPM1 variants based on the type of reduced-intensity conditioning regimen received. This preliminary observation should be confirmed in a prospective randomized trial but may have implications for allogeneic transplant conditioning selection.

The European Leukemia Network guidelines have recognized, since 2017, that the absence of MRD represents a superior treatment response for AML than complete remission defined by cytomorphology alone.36 DNA sequencing can detect multiple potential variants within multiple AML MRD targets; a prior study using quantitative PCR required 27 different assays for NPM1 variants alone.45 The FDA defines achievement of MRD levels of less than 0.01% as important evidence of drug efficacy in patients with acute leukemia.46 Findings from this study are consistent with this standard for adult patients with FLT3-ITD and/or NPM1 mutated AML in first complete remission prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant. Results showed that approximately 1 in 6 of such patients were in a high-risk subgroup with MRD detectable higher than this threshold, with serious posttransplant outcomes not adequately addressed by the current clinical standard of care. Adults with persistence of FLT3-ITD and/or NPM1 variants in cytomorphological remission after initial treatment for AML therefore represent patients with unmet medical need, who should be offered enrollment in a therapeutic clinical trial wherever possible.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it is unknown how results of NGS-MRD testing on bone marrow would differ from blood. Second, this study did not have access to technical details of the pretransplant flow cytometry MRD testing reported to the CIBMTR and could not determine whether centralized flow cytometry MRD testing would be concordant with or complementary to NGS-MRD. Third, 4 potential NGS-MRD targets (FLT3-TKD, IDH1, IDH2, KIT) were not selected for validation based on results of the discovery cohort. Fourth, in this registry study of patients with AML undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant, it is unknown how these results apply to others who did not undergo transplant due to results of MRD testing performed by the local site, donor unavailability, structural racism,47 or other factors. Fifth, only approximately 10% of patients were reported as having received posttransplant maintenance therapy. Although there is evidence that this approach may reduce relapse including in those MRD positive after transplant,48,49 no benefit of posttransplant maintenance therapy was observed for any subset in our study. Sixth, it is unknown whether the type of therapy that induced remission may have interacted with findings reported herein. Seventh, 84% of the participants were White. The generalizability of these results to a more diverse cohort is unknown. Eighth, it is unknown whether serial testing after transplant would further improve the performance characteristics of NGS-MRD testing.

Conclusions

Among patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first remission prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant, the persistence of FLT3 internal tandem duplication or NPM1 variants in the blood at an allele fraction of 0.01% or above was associated with increased relapse and worse survival compared with those without these variants. Further study is needed to determine whether routine DNA-sequencing testing for residual variants can improve outcomes for patients with acute myeloid leukemia.

eMethods

eReferences

eFigure 1. STARD diagram

eFigure 2. Association of baseline patient characteristics and pre-transplant flow cytometry on clinical outcomes

eFigure 3. Detection of residual variants in the blood of AML patients during complete remission

eFigure 4. Association of pre-transplant residual variants on clinical outcomes

eFigure 5. Univariate cox regression for relapse

eFigure 6. Association of NGS-MRD status for NPM1 and/or FLT3-ITD on clinical outcomes

eFigure 7. Association of site flow cytometry and NGS-MRD status on clinical outcomes for patients with baseline FLT3-ITD and/or NPM1 variants

eFigure 8. Association of age, race, and NGS-MRD status for NPM1 and/or FLT3-ITD on clinical outcomes

eFigure 9. Association of persistent variants by gene on clinical outcomes

eFigure 10. Association of conditioning intensity, age, and NGS-MRD status for NPM1 and/or FLT3-ITD on clinical outcomes

eFigure 11. Association of NPM1 and/or FLT3-ITD status and NGS-MRD VAF on clinical outcomes

eFigure 12. Association of post-transplant maintenance therapy and NGS-MRD status on clinical outcomes

eTable 1. Patient clinical characteristics (NPM1 and/or FLT3-ITD baseline)

eTable 2. Comparison of reduced intensity regimens

eTable 3. Interquartile range of observation times for patients analyzed in Figure 4

eTable 4. Regions of interest in targeted DNA-sequencing panel

eTable 5. Sample sequencing summary (n = 1,075)

eTable 6. Variants detected by next-generation sequencing in the blood of AML patients prior to conditioning

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Döhner H, Weisdorf DJ, Bloomfield CD. Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(12):1136-1152. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1406184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ley TJ, Miller C, Ding L, et al. ; Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network . Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):2059-2074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, et al. Genomic classification and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(23):2209-2221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tyner JW, Tognon CE, Bottomly D, et al. Functional genomic landscape of acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2018;562(7728):526-531. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0623-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bottomly D, Long N, Schultz AR, et al. Integrative analysis of drug response and clinical outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(8):850-864.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel JP, Gönen M, Figueroa ME, et al. Prognostic relevance of integrated genetic profiling in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1079-1089. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duncavage EJ, Schroeder MC, O’Laughlin M, et al. Genome sequencing as an alternative to cytogenetic analysis in myeloid cancers. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(10):924-935. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grimwade D, Walker H, Oliver F, et al. The Medical Research Council Adult and Children’s Leukaemia Working Parties . The importance of diagnostic cytogenetics on outcome in AML: analysis of 1612 patients entered into the MRC AML 10 trial. Blood. 1998;92(7):2322-2333. doi: 10.1182/blood.V92.7.2322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone RM, Mandrekar SJ, Sanford BL, et al. Midostaurin plus chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia with a FLT3 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):454-464. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiNardo CD, Stein EM, de Botton S, et al. Durable remissions with ivosidenib in IDH1-mutated relapsed or refractory AML. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):2386-2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perl AE, Martinelli G, Cortes JE, et al. Gilteritinib or chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory FLT3-mutated AML. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1728-1740. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1902688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montesinos P, Recher C, Vives S, et al. Ivosidenib and azacitidine in IDH1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(16):1519-1531. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2117344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tazi Y, Arango-Ossa JE, Zhou Y, et al. Unified classification and risk-stratification in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):4622. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32103-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Döhner H, Wei AH, Appelbaum FR, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood. 2022;140(12):1345-1377. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022016867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koreth J, Schlenk R, Kopecky KJ, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective clinical trials. JAMA. 2009;301(22):2349-2361. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornelissen JJ, Versluis J, Passweg JR, et al. ; HOVON; SAKK Leukemia Groups . Comparative therapeutic value of post-remission approaches in patients with acute myeloid leukemia aged 40-60 years. Leukemia. 2015;29(5):1041-1050. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollyea DA, Bixby D, Perl A, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: acute myeloid leukemia, version 2.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(1):16-27. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heuser M, Freeman SD, Ossenkoppele GJ, et al. 2021 update on MRD in acute myeloid leukemia: a consensus document from the European LeukemiaNet MRD Working Party. Blood. 2021;138(26):2753-2767. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021013626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckley SA, Wood BL, Othus M, et al. Minimal residual disease prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia: a meta-analysis. Haematologica. 2017;102(5):865-873. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.159343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Araki D, Wood BL, Othus M, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: time to move toward a minimal residual disease-based definition of complete remission? J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(4):329-336. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hourigan CS, Gale RP, Gormley NJ, Ossenkoppele GJ, Walter RB. Measurable residual disease testing in acute myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia. 2017;31(7):1482-1490. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jongen-Lavrencic M, Grob T, Hanekamp D, et al. Molecular minimal residual disease in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(13):1189-1199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Short NJ, Zhou S, Fu C, et al. Association of measurable residual disease with survival outcomes in patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(12):1890-1899. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.4600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hourigan CS, Dillon LW, Gui G, et al. Impact of conditioning intensity of allogeneic transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia with genomic evidence of residual disease. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(12):1273-1283. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Short NJ, Fu C, Berry DA, et al. Association of hematologic response and assay sensitivity on the prognostic impact of measurable residual disease in acute myeloid leukemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Leukemia. 2022;36(12):2817-2826. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01692-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paiva B, Vidriales MB, Sempere A, et al. ; PETHEMA (Programa para el Estudio de la Terapéutica en Hemopatías Malignas) cooperative study group . Impact of measurable residual disease by decentralized flow cytometry: a PETHEMA real-world study in 1076 patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2021;35(8):2358-2370. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01126-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tettero JM, Freeman S, Buecklein V, et al. Technical aspects of flow cytometry-based measurable residual disease quantification in acute myeloid leukemia: experience of the European LeukemiaNet MRD Working Party. Hemasphere. 2021;6(1):e676. doi: 10.1097/HS9.0000000000000676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuurhuis GJ, Heuser M, Freeman S, et al. Minimal/measurable residual disease in AML: a consensus document from the European LeukemiaNet MRD Working Party. Blood. 2018;131(12):1275-1291. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-09-801498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klco JM, Miller CA, Griffith M, et al. Association between mutation clearance after induction therapy and outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA. 2015;314(8):811-822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.9643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levis MJ, Perl AE, Altman JK, et al. A next-generation sequencing-based assay for minimal residual disease assessment in AML patients with FLT3-ITD mutations. Blood Adv. 2018;2(8):825-831. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018015925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thol F, Gabdoulline R, Liebich A, et al. Measurable residual disease monitoring by NGS before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in AML. Blood. 2018;132(16):1703-1713. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-02-829911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dillon R, Hills R, Freeman S, et al. Molecular MRD status and outcome after transplantation in NPM1-mutated AML. Blood. 2020;135(9):680-688. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019002959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang EC, Chen C, Lu R, Mannis GN, Muffly L. Measurable residual disease status and FLT3 inhibitor therapy in patients with FLT3-ITD mutated AML following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021;56(12):3091-3093. doi: 10.1038/s41409-021-01475-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loo S, Dillon R, Ivey A, et al. Pretransplant FLT3-ITD MRD assessed by high-sensitivity PCR-NGS determines posttransplant clinical outcome. Blood. 2022;140(22):2407-2411. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022016567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murdock HM, Kim HT, Denlinger N, et al. Impact of diagnostic genetics on remission MRD and transplantation outcomes in older patients with AML. Blood. 2022;139(24):3546-3557. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021014520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129(4):424-447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-733196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jimenez Jimenez AM, De Lima M, Komanduri KV, et al. An adapted European LeukemiaNet genetic risk stratification for acute myeloid leukemia patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant; a CIBMTR analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021;56(12):3068-3077. doi: 10.1038/s41409-021-01450-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hong S, Majhail NS. Increasing access to allotransplants in the United States: the impact of race, geography, and socioeconomics. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2021;2021(1):275-280. doi: 10.1182/hematology.2021000259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gyurkocza B, Sandmaier BM. Conditioning regimens for hematopoietic cell transplantation: one size does not fit all. Blood. 2014;124(3):344-353. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-514778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Craddock C, Jackson A, Loke J, et al. Augmented reduced-intensity regimen does not improve postallogeneic transplant outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2020;39(7):768-778. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gilleece MH, Labopin M, Yakoub-Agha I, et al. Measurable residual disease, conditioning regimen intensity, and age predict outcome of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia in first remission: a registry analysis of 2292 patients by the Acute Leukemia Working Party European Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(9):1142-1152. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levis M. Midostaurin approved for FLT3-mutated AML. Blood. 2017;129(26):3403-3406. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-05-782292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou Z, Nath R, Cerny J, et al. Reduced intensity conditioning for acute myeloid leukemia using melphalan- vs busulfan-based regimens: a CIBMTR report. Blood Adv. 2020;4(13):3180-3190. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baron F, Labopin M, Peniket A, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning with fludarabine and busulfan versus fludarabine and melphalan for patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Cancer. 2015;121(7):1048-1055. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ivey A, Hills RK, Simpson MA, et al. ; UK National Cancer Research Institute AML Working Group . Assessment of minimal residual disease in standard-risk AML. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(5):422-433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Acute myeloid leukemia: developing drugs and biological products for treatment. Food and Drug Administration . August 2020. Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/acute-myeloid-leukemia-developing-drugs-and-biological-products-treatment

- 47.Abraham IE, Rauscher GH, Patel AA, et al. Structural racism is a mediator of disparities in acute myeloid leukemia outcomes. Blood. 2022;139(14):2212-2226. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021012830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burchert A, Bug G, Fritz LV, et al. Sorafenib maintenance after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia with FLT3-internal tandem duplication mutation (SORMAIN). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(26):2993-3002. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Platzbecker U, Middeke JM, Sockel K, et al. Measurable residual disease-guided treatment with azacitidine to prevent haematological relapse in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukaemia (RELAZA2): an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(12):1668-1679. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30580-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)–specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106(8):2912-2919. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eReferences

eFigure 1. STARD diagram

eFigure 2. Association of baseline patient characteristics and pre-transplant flow cytometry on clinical outcomes

eFigure 3. Detection of residual variants in the blood of AML patients during complete remission

eFigure 4. Association of pre-transplant residual variants on clinical outcomes

eFigure 5. Univariate cox regression for relapse

eFigure 6. Association of NGS-MRD status for NPM1 and/or FLT3-ITD on clinical outcomes

eFigure 7. Association of site flow cytometry and NGS-MRD status on clinical outcomes for patients with baseline FLT3-ITD and/or NPM1 variants

eFigure 8. Association of age, race, and NGS-MRD status for NPM1 and/or FLT3-ITD on clinical outcomes

eFigure 9. Association of persistent variants by gene on clinical outcomes

eFigure 10. Association of conditioning intensity, age, and NGS-MRD status for NPM1 and/or FLT3-ITD on clinical outcomes

eFigure 11. Association of NPM1 and/or FLT3-ITD status and NGS-MRD VAF on clinical outcomes

eFigure 12. Association of post-transplant maintenance therapy and NGS-MRD status on clinical outcomes

eTable 1. Patient clinical characteristics (NPM1 and/or FLT3-ITD baseline)

eTable 2. Comparison of reduced intensity regimens

eTable 3. Interquartile range of observation times for patients analyzed in Figure 4

eTable 4. Regions of interest in targeted DNA-sequencing panel

eTable 5. Sample sequencing summary (n = 1,075)

eTable 6. Variants detected by next-generation sequencing in the blood of AML patients prior to conditioning

Data Sharing Statement